#The Oath of the Tennis Court

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

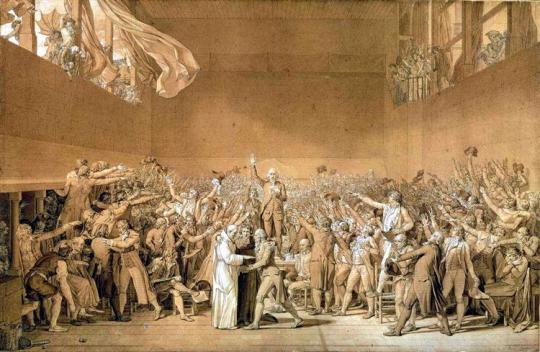

The Oath of the Tennis Court by Jacques Louis David

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

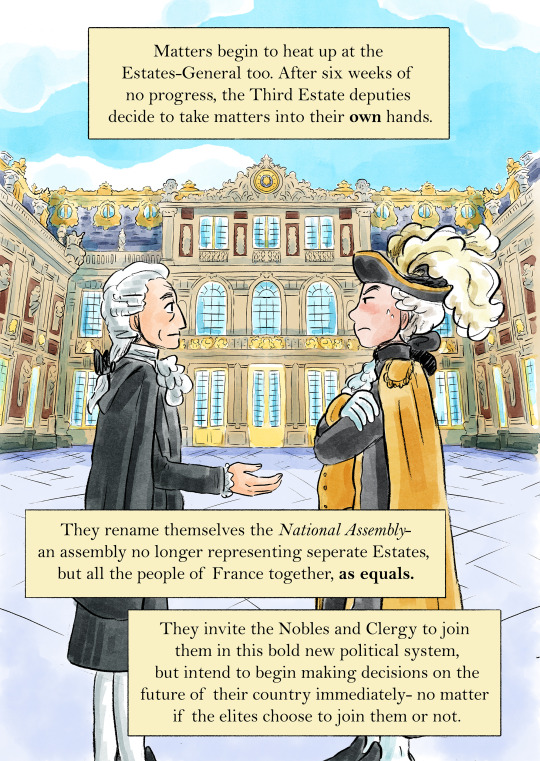

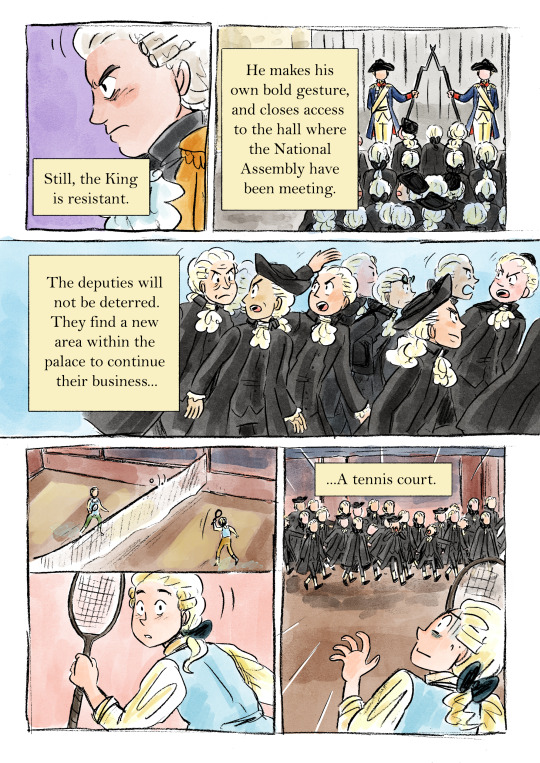

Incorruptible pt 24

The creation of the National Assembly is pretty inspiring, in their defiance and willingness to stand up for human rights. It was sad to hear of events in the modern day National Assembly yesterday, where many people in power have clearly forgotton it's origins.

#incorruptiblecomic#They suspended a deputy for standing up for human rights#and simply raising a Palestinian flag.#That's not the National Assembly I've drawn here!#french revolution#frev#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#camille desmoulins#history comic#historical fiction#versailles palace#tennis court oath#webcomic#comic#webtoon#comic art#comic update

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you guys know that in 1989 a bunch of French Revolutionary themed Disney stamps were released in honor of the 200th anniversary of the revolution? Because I just found out about them and I can't breathe.

#french revolution#1989#marie antoinette#disney#horace taking the tennis court oath actually killed me and I am dead now sorry

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think grian should have been involved in the french revolution 1789

#grian#hermitcraft#i want to superimpose his fishing painting onto the tennis court oath#trafficblr#life series

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading up on an area of history about which you know next to nothing is super fun actually. No one give me any spoilers for the French Revolution. They just introduced a Dr Guillotin and I can't wait to see what he does next

#my knowledge of the French Revolution before starting this brick of a book was mostly just abstract phrases#half remembered from high school like 'the Tennis Court Oath'#which then makes it super exciting when they're like 'Aw it's raining:( Let's shelter in this indoor tennis court' OH OH IT'S THE THING!!#DO IT GUYS!! DO THE OATH!!#history

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tennis Court Oath by David, details (taken in the Carnavalet)

#tennis court oath#jacques louis david#carnavalet#lmaoooo @ that one dude who refused to take the oath#frev#french revolution

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

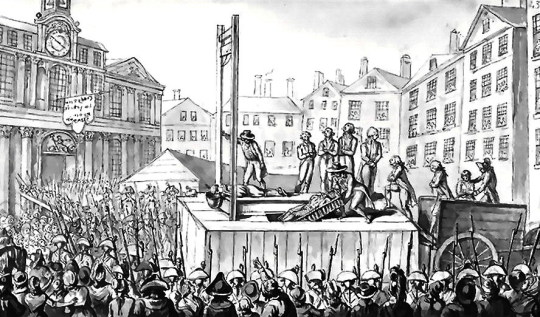

The Tennis Court Oath (1790) by Jacques-Louis David

On 20 June 1789, the members of the French Third Estate (peasants and bourgeoisie) took the oath in the tennis court of the Palace of Versailles. Their vow "not to separate and to reassemble wherever necessary until the Constitution of the kingdom is established" became a pivotal event in the French Revolution.

#The Tennis Court Oath#Jacques-Louis David#1790#1700s#French Revolution#revolution#Tennis Court Oath#art#painting#Miss Cromwell

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

tennis court by lorde is so frev coded

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tennis Court Oath

On 20 June 1789, the members of the French Third Estate took the Tennis Court Oath in the tennis court which had been built in 1686 for the use of the Versailles palace.

During the Estates-General Assembly in 1789, the French people, represented by three estates (clergy, nobility, and commoners), convened to address the country's financial crisis and political issues. However, tensions arose between the representatives of the Third Estate (commoners) and the other two estates, as the Third Estate sought equal representation and voting power, which the clergy and nobility were reluctant to grant.

Frustrated by the lack of progress and the inequality within the Estates-General, the representatives of the Third Estate decided to break away and form their own assembly. They called themselves the National Assembly, declaring that they represented the will of the French people. Their goal was to create a new constitution for France and initiate reforms.

However, when the National Assembly arrived at their meeting place in Versailles on June 20, 1789, they found that the doors to their usual meeting hall had been locked by orders of King Louis XVI. Fearing that the king was trying to dissolve their assembly and suppress their efforts, they relocated to a nearby indoor tennis court known as the "Jeu de Paume" to continue their proceedings.

Inside the tennis court, the representatives of the Third Estate, led by figures like Maximilien Robespierre and Camille Desmoulins, took an oath not to disband until they had successfully created a new constitution for France. This oath is now known as the Tennis Court Oath. The oath solidified the resolve of the National Assembly to stand united against the traditional order and marked a crucial turning point in the French Revolution, inspiring people across the country to support the cause for change.

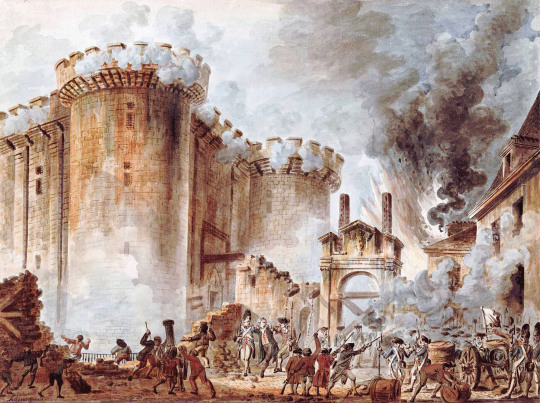

The Tennis Court Oath was a critical step in the revolutionary process. Eventually, it led to further significant events such as the storming of the Bastille, the abolition of feudal privileges, and the transformation of France into a constitutional monarchy, followed by the eventual abolition altogether.

#Tennis Court Oath#French Revolution#History#French History#National Assembly#Estates-General#Versailles#Maximilien Robespierre#Camille Desmoulins#King Louis XVI#Constitutional Monarchy#Revolution#Political Events#18th Century#European History#today on tumblr#deep thinking

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Huh, I didn't know that roleplaying evolved from wargaming. I assumed the two evolved parallel but independently from each other. There's this thing that some history professors will do where they will have their students "war game" famous occasions in history. Galileo's Trial, The Council of Nicaea, the Salem Witch Trials, etc. I wonder if those history games evolved from roleplaying or wargaming. I suspect wargaming because the history roleplays don't involve dice rolls.

Honestly it's weird that roleplaying as we know it evolved from historical wargaming.

Like for example DBA rules contain some suggestions for running campaigns with narrative and "propaganda" so I wouldn't say that it's something incompatible, and 0E looks way more like wargames than say PbtA games do, but storytelling games were a feature of artistic salons for way longer and they appear much closer to roleplaying than rulesets for reenacting ancient battles on tabletop.

Salon games didn't have skill checks but neither did wargames and it's strange that nobody came up with simplistic skill checks to add uncertainty and realism to the game

I think the line is a lot clearer when the role of dice and rules in tabletop roleplaying games is correctly understood.

"Uncertainty" and "realism" are, at best, secondary to what the dice are actually doing. Even most tabletop RPGs get it wrong when they try to explain themselves – they'll talk about the rules as something to fall back on to prevent schoolyard arguments (i.e., "yes I did!/no you didn't!") from derailing the story, when in fact it's the exact opposite.

If we look at freeform roleplaying as an illustrative parallel, we see that, while newly formed groups may in fact fall to bickering when a consensus can't be reached about what ought to happen next, mature and well-established groups tend instead to fall prey to excessive consensus-seeking: the impulse to always find an outcome that isn't necessarily one which everybody at the table can be happy with, but at the very least one which everybody at the table can agree is reasonable – and that's a lot more constraining than one might think.

In this sense, the role of picking up the dice isn't to build consensus, but to break it – to allow for the possibility of outcomes which nobody at the table wanted or expected. It's the "well, this is happening now" factor that prevents the table's dynamic from ossifying into endless consensus-seeking about what reasonably ought to happen next.

Looking to the history of wargames, this is precisely the innovation they bring to the table. Early historical wargames tended to be diceless affairs which decided outcomes by deferring to the judgment of a referee or other subject matter expert, but the use of randomisers increasingly came to be favoured because referees would tend to favour the most reasonable course, precluding upsets and rendering the outcomes of entire battles a foregone conclusion. This goes all the way back to the roots of tabletop wargaming – people were literally having "rules versus rulings" arguments two hundred years ago!

(This isn't the only facet of tabletop roleplaying culture which has its roots in wargaming culure, of course. For example, you can draw a direct line from the preoccupation of early tabletop RPGs with punishing the use of out-of-character knowledge to historical wargaming's gentleperson's agreement to refrain from making decisions based on information that one's side's commanders couldn't possibly have possessed when re-creating historical battles.)

To be clear, I don't necessary disagree that salon games could have yielded something like modern tabletop RPGs. However, first they'd have had to arrive at the paired insights that a. excessive consensus-seeking is poison to building an interesting narrative; and b. randomisers can be used to force the breaking of consensus, and historical wargames had a substantial head start because they'd figured all that out a century earlier.

#I was once assigned the role of Jean Sylvain Bailly in a History game of the Tennis Court Oath and National Assembly#People complain about herding cats#This was closer to herding fish imo

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

the tennis court oath by jacques-louis david (1791)

0 notes

Text

A revolution that went so appallingly wrong

__________________________________________

It's so horribly shocking of how the 3rd estate(or literally everybody else in the french population) tried to find equality in their nation just to cause legal genocide. (- It just felt so backwards to me -)

#taxation#king louis xvi#reign of terror#revolution#1st estate(clergy)#2nd estate(nobility)#fear#anger#violence#tennis court oath#robespierre#danton#friend of the people#marat#inequality#let them eat cake#um...I like history and stuff

1 note

·

View note

Text

someone printed out a painting of the Continental Congress and put it on the breakroom chalkboard at my museum, with the caption "what's going on here? wrong answers only!"

current answers include:

"auditions for Hamilton"

"hot girl summer" (mine)

"me and the girls drafting a text to my crush"

"planning their Barbenheimer movie night"

"the Tennis Court Oath"

"trying to decide who will take the One Ring to Mordor"

"hanging out at an old-school Pizza Hut"

"roll for initiative"

"Elon Musk renaming Twitter to X"

542 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since it won the poll I'm posting the whole thing. The context: Robespierre visits David on the 8 Thermidor evening, together they stare at David's unfinished Tennis Court Oath. Robespierre asks "why did you draw me like this (clutching my chest in patriotic transport)?", "You are the only one who understood the meaning of the Revolution" replies David. As he leaves Robespierre says "Next time, draw me like the others."

David was left alone. He lifted a veil that was covering a drawing in dark ink. It was representing the same people, but naked. Robespierre was depicted with bulging pectoral, his muscles taut. His straight penis was rising up between his strong thighs. How would Robespierre have reacted, had he seen himself drawn like this?

This is no great translation, but I tried doing justice to the way the original is worded as if David gave him a patriotic hard-on. Which he very much didn't. Robespierre has the same generic dick as everyone else in the naked draft, but I can't believe the author made me go and check.

#jacques ravenne: la chute#this book has two mention of Rob private parts and both are completely unnecessary

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

A brief history of Camille Desmoulins

It's March 2nd today, which means it's the birthday of my biggest writing muse: Camille Desmoulins, 18th-century journalist, French revolutionary and the man who called the Parisian people to arms, resulting in the Storming of the Bastille.

Despite essentially causing such a major historical event, Camille is largely glossed over by historians, and not many people know about him as a result. However, that doesn't mean he didn't have any influence on the revolution, and he contributed to it the same way as famous personalities like Robespierre, Danton, and Saint-Just did. So, in honor of his 264th birthday, here's a little history of the man gracing my profile pic.

The early years

Camille was born in 1760, in the commune of Guise in the province of Picardy. At fourteen years of age, he obtained a scholarship to study at the Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris, one of the most esteemed elite schools in France. There, he met Maximilien de Robespierre, and despite the boys being two years apart in age and having very different personalities - Maximilien was more calm and secluded, while Camille was lively and impulsive - the two bonded over their mutual love for classical history and philosophy.

After graduating from Louis-le-Grand, Camille began to pursue a career in law, being admitted to the Parlement of Paris in 1785. However, his stammer and lack of connections to the Parisian legal community impeded his success, so he instead took up writing as a journalist, with a primary focus on political affairs.

The Estates-General and the call to arms

When King Louis XVI convened the Estates-General in 1789, Camille was present at the procession on May 5th, writing a comment about the event. The Comte de Mirabeau, presenting himself as a middleman between the aristocracy and the Third Estate as well as a patron for Camille, even employed the latter as a writer for his newspaper for a time.

However, the mingling of the three estates was not well received by the king, and he tried to regain control over the members who had dubbed themselves the National Assembly by closing the Salle des Menus Plaisirs where the deputies met to them. Instead, the National Assembly held their meeting in the Jeu de Paume (which was normally used as the tennis court of Versailles), where the members from various estates swore the oath to not part until they had devised a new constitution for France.

Eventually, the king was forced to relent, but that didn't keep him from concentrating his troops in Versailles and Paris. When he dismissed finance minister Jacques Necker - who was very popular among the people and considered an advocate for their interests - the atmosphere in Paris took a turn for the worse.

The Parisians were angry, worried, and in fear, and in this situation - on July 12th, 1789 - Camille took the opportunity to leap onto a table in front of the Cafe de Foy in the Palais Royal. There, he delivered a passionate speech, even losing his usual stammer in the heat of the moment, calling the people to take up arms to defend themselves against the imminent massacre of the king's troops* and put on cockades so they recognize each other.

Following Camille's example, the people took green leaves from the trees lining the Palais Royal and stuck them to their coats. However, since green was associated with the Comte d'Artois, the conservative brother of the king, the color of the cockades quickly shifted to red and blue, the colors of the commune of Paris (white was added later to represent the king, in an attempt to reconcile the factions). Bad news for Camille's leaf cockades…

*The king most likely didn't plan to massacre the citizens, but the presence of so many troops, a good deal of them foreign, made the populace very anxious.

Journalistic career and the Girondins

After being present at the Storming of the Bastille, Camille continued to be politically active, publishing radical pamphlets and newspapers such as La France Libre, Discours de la lanterne aux Parisiens, and Révolutions de France et de Brabant. He joined the Club des Cordeliers led by Georges Danton and became part of the radical leftist Montagnards, the "Mountain" party of the National Convention, consisting of members such as Maximilien de Robespierre, Jean-Paul Marat, and Louis Antoine Saint-Just.

In 1790, Camille also married Lucile Duplessis, whom he had known for several years and harbored strong feelings for. However, despite Lucile's mother being a good friend of Camille's, her father repeatedly denied the couple his blessing, being of the opinion that Camille couldn't support a family with his meager income as a journalist. (Indeed, in the days prior to the revolution, Camille often had to live in poverty due to his difficulties establishing himself as a lawyer.) After gaining popularity as a journalist, however, Lucile's father finally allowed the lovers to marry, the marriage taking place on December 29th with Robespierre, Jacques Pierre Brissot, and Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve being present as witnesses.

However, success and bliss were not meant to last: After the massacre at the Champs de Mars on July 17th, 1791, Camille had to go into hiding, putting his journalistic activities on halt for the time being. When he took up his work again in 1792, he wrote a few papers viciously attacking the political faction of the Girondins and specifically their leader, Jean Pierre Brissot. In his works, Camille accused them of betraying the republic and counter-revolutionary acts*, which majorly contributed to the arrest and subsequent execution of many Girondin leaders, including Brissot. However, Camille came to regret his role in their deaths: During the trial, he was lamenting "Oh my God! My God! It is I who killed them!", collapsing in the courtroom when the death sentence was announced.

*The Girondins had acquired a reputation of intending to harm the revolution with their actions, on one hand due to their pro-war attitude (the war with other European empires had taken its toll on the Republic of France), and on the other hand due to the party's indecisiveness concerning the judgement of the king (some of them argued for clemency or a milder punishment).

Vieux Cordelier and downfall

After 1793, Camille had a notable change of heart, becoming one of the voices in favor of clemency instead of terror. In what would become his most well-known and popular journal, Le Vieux Cordelier, he argued against imprisoning citizens based on the mere suspicion of counter-revolutionary activities, condemning the brutality of the Reign of Terror and even directly addressing his old friend Robespierre to moderate his approach.

However, this only ended up making Camille another prime target. Robespierre initially tried to defend Camille from the Jacobin Club calling for his expulsion, but this changed when Danton's secretary, Fabre d'Églantine, was exposed for financial fraud. This cast a poor light on Danton and his allies, including Camille, and it was what made Robespierre support legally persecuting them. Charges of corruption, royalist tendencies, and conspiracy against the revolution were brought forth against them, resulting in the arrest of Camille, Danton, and the rest of the Dantonists.

The trial itself took place from April 3rd to 5th, and was obviously aimed at getting rid of the political threat that Danton and his allies posed. By decree of the National Convention, the accused were not allowed to defend themselves, in addition to being denied the right to call any witnesses. The guilty verdict, which was essentially prescribed due to the nature of the trial, was passed in the absence of the defendants to prevent unrest in the courtroom, and the Dantonists were scheduled to ascend the scaffold on the very same day.

In Luxembourg prison, Camille wrote a last letter to his beloved wife Lucile, with spots from tears being visible to this day. However, it should never reach her, as Camille was informed that Lucile had also been arrested on his way to the scaffold. He went wild upon hearing the news, and it took several men to get him into the tumbrel. Of the fifteen Dantonists guillotined on April 5th, 1794, Camille was the third to die.

Lucile, who had been arrested on the charge of conspiring to free her husband, followed him only eight days later, being guillotined on April 13th, 1794. She left behind her not even two years old son, Horace Camille Desmoulins, who was raised by Lucile's mother and sister. In 1817, Horace emigrated from France to Haiti, where his gravestone can be found to this day.

And that is the story of Camille Desmoulins: the man who ignited the spark of the French Revolution, but eventually got disgusted by its brutality, leading to his tragic end.

Camille may be a bit overlooked as a historical figure, but that does not make him less interesting or important.

So, in all due honor: Happy birthday, Camille! 🎂

#french revolution#frev#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#history#french history#joyeux anniversaire Camille! <3

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I first saw a draft of what failed to become David’s Oath of the Tennis Court, one man caught my eye. He stands out from the others around him, with his hands pressed over his heart, his emotion so intense, so clear, it’s almost unbearable. He’s not just joining in the moment, but he is giving himself completely to the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. This man is not simply swearing an oath but dedicating his very heart. This is Robespierre.

Beside him stands another man. Perched on a chair, firm stance and extended arm, he swears the oath but doesn’t lose himself in the moment. This is Dubois-Crancé.

They make for an interesting and contrasting duo, don’t they?

In 1792, Dubois-Crancé wrote a book expressing his views on his fellow members of the Constitutional Assembly. It’s an interesting collection of portraits of men whose work still shapes the world we live in today. This is what he said about the person forever depicted beside him.

As always, this is my translation and is by no means perfect. Explanatory notes are included at the end.

Portrait of Robespierre by Dubois-Crancé (translation)

General of the Sans-Culottes, the enemy of all subjugation and fearless defender of the rights of the people, Robespierre lacked only an imposing physique, a voice like Danton’s, and, at times, less presumption and obstinacy. These minor flaws often harmed the cause he defended; he was proud and jealous yet just and virtuous. His fiercest detractors have never been able to accuse him of a moment of misjudgement. Always steadfast in the most austere principles, he never wavered. Like he was in the beginning, so he remained until the end, and such praise applies to very few individuals.

In the Constituent Assembly (1), Robespierre was neither president, secretary, nor member of any committee. The patriots themselves respected him but did not love him. The reason is simple: this man, nourished by the morality of Rousseau, had the courage to emulate his model. He possessed the same austere principles, manners, reclusive nature, uncompromising spirit, proud simplicity, even moroseness. He lacked the talent, but that did not make Robespierre an ordinary man. Taking counsel only from his own heart, he often faced disfavour for his opinions, which were almost always seen as extreme because Robespierre never wanted a monarchy and believed that freedom exists only in a state of perfect equality. He always spoke from his principles, and at the time we were concluding our constitution, he spoke as if its amendments did not exist.

Robespierre had enough discernment to constantly despise Barnave (2), the Lameths (3), and that minority of the nobility who had betrayed their order only to rise individually on its ruins. Calumnies, even outright insults, never deterred him. I saw him resist the entire assembly and demand, as a man conscious of his dignity, that the president calls it to order.

The Jacobins contributed more to Robespierre's glory than the National Assembly. There, he had friends, was listened to and encouraged, and often developed excellent ideas. He rarely had this opportunity in the National Assembly. In the beginning, he was almost non-existent, even showing a condemnable indifference in deliberations that did not please him. At that time, he would have seen limited liberty as objectionable as slavery. He refused to support the suspensive veto (4) because he wanted no veto. He was right, but since the cause was lost, was it better to leave to the schemers the ability to grant an absolute veto?

After the death of Mirabeau (5), the defection of the patriotic party (6), and the betrayal of the Lameths (7), Robespierre showed great character. Despite the extreme disfavour of his opinions, he compelled the respect of his enemies, even triumphing over them in some very thorny circumstances, and at least deprived them of the right to scheme in the following legislature.

I do not know if Robespierre was well-versed in the tactics of the Assembly. This seems unlikely, for he would have sacrificed his zeal or self-esteem for the public good. He did not place himself next to the president’s desk to seize and stubbornly hold the floor. He would have known that the Assembly's scheming leaders called him their Maury (8), deliberately giving him free rein by preference (and then the president was at their command) to alienate the moderates, shape their opinions, and secure a majority. He would have seen that while he might gain glory through the press and the tribunes, he was harming the public cause within the Assembly. Finally, he would have let men as pure but less extreme than himself, less absolute in their opinions, and who, in more measured terms, would have redirected the assembly's focus towards its duties and the principles of the Constitution.

Nevertheless, let us render justice to virtue, honour, and integrity. Robespierre was never involved in any intrigue. Always alone with his heart, he bravely faced the most violent of storms. If the Assembly had been composed only of Robespierres, France might perhaps be nothing but a heap of ruins today. Still, amidst so many intrigues, baseness, vices, and corruptions, amid the clash of opposing interests, diverse opinions, tumults, calumnies, fears, and assassinations, Robespierre stood as a rock, an impregnable rock. Thus, he did his duty, he served his country well, and his example is a precious model for our successors.

Source: Le véritable portrait de nos législateurs ou Galerie des tableaux exposés à la vue du public depuis le 5 mai 1789, jusqu’au 1er octobre 1791. A Paris, 1792

Notes

(1) In the text, Dubois-Crancé refers to two separate bodies, both of which he and Robespierre were members of, the National Assembly and the Constituent Assembly. While related, these are not the same thing. The National Assembly (Assemblée nationale) existed from June 17, 1789 to July 9, 1789 and was an initial revolutionary body formed by the Third Estate during the Estates-General. The Constituent Assembly (Assemblée constituante) was its successor and existed from July 9, 1789, to September 30, 1791. The purpose of the Constituent Assembly was to draft France's first written constitution and restructure the government.

(2) Antoine Pierre Joseph Marie Barnave (1761-1793) was a prominent figure in the National Constituent Assembly who was part of the Feuillants, a group known for supporting constitutional monarchy and advocating moderate reforms. He is most known for escorting the royal family back to Paris during the Flight to Varennes, and secretly acting as Marie Antoinette’s advisor in the aftermath.

(3) The Lameth brothers—Charles (1757-1832), Alexandre (1760-1829), and Théodore (1756-1854)— were French nobles known for their general moderatism and support of constitutional monarchy. Both Charles and Alexandre were active in the Constituent Assembly, with the former also joining the Jacobin club. The brothers were known for their liberal views and were part of the moderate faction within the revolutionary movement. Dubois-Crancé probably refers to Charles and Alexandre, because Theodore primarly served as an officer in the French army and did not engage as directly in the political sphere as his brothers. Fun Fact: Like Robespierre, Charles represented Artois in the États Généraux.

(4) The suspensive veto was a political power granted to the king by the Constitution of 1791. This type of veto allowed the king to temporarily block legislation passed by the Assembly. However, it was not an absolute power to prevent a law from ever taking effect; instead, it delayed the enactment of a law. If the king used this veto, the law could be reconsidered and potentially passed by the next legislative session, bypassing the king's objection. This system was designed to limit the monarch's power, ensuring he could delay but not permanently block legislative progress.

(5) Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau (1749-1791) was a prominent politician and orator during the early stages of the French Revolution. He came from a noble family and had a rebellious and scandalous life In 1789, he was elected to represent the Third Estate at the Estates-General as a representative of Provence, where he emerged as a leader and an advocate for constitutional monarchy. He was instrumental in drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and was a prolific writer and speaker, earning the nickname "the tribune of the people". He died of natural causes in 1791, at the height of his popularity and influence.

(6) The revolutionaries split into several different factions in 1791, because they had more and more divergent beliefs and many members quit the Jacobin club.

(7) The Lameths were initially active members of the Jacobin Club and were influential in its early days. However, they were part of the moderate faction that sought to work within the bounds of constitutional monarchy rather than pushing for more radical Republican changes. As the Jacobin Club became increasingly radical in their eyes, they and other moderates found themselves increasingly alienated. In 1791, this culminated in a split where the Lameths and other moderates left the Jacobin Club to form a new group, the Feuillants Club.

(8) Abbé Jean-Sylvestre Maury (1746-1817) was a significant counter-revolutionary figure, known for his inflexible defence of traditional values and the ancien régime. Initially celebrated for his sermons and literary acumen, Maury quickly ascended as a key clerical voice in the Estates-General, defending the privileges of the Church and the monarchy against revolutionary reforms. As a member of the National Constituent Assembly, he opposed the civil constitution of the clergy and other radical changes, positioning himself as a leader among royalists and conservative factions. Calling Robespierre "their Maury" implies that he was seen as a dogmatic and dominating presence within the assembly, albeit for a different ideological cause.

#frev#french revolution#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#primary sources#dubois-crance#translation

35 notes

·

View notes