#The Island of the Fisherwomen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

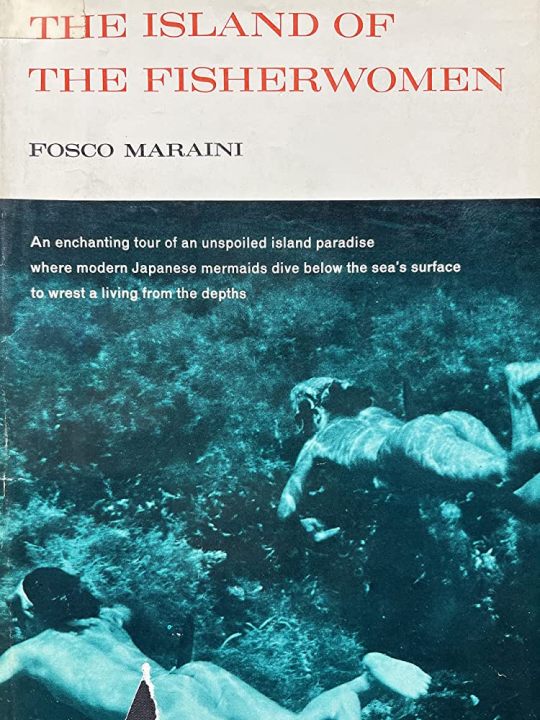

Fosco Maraini: The Island of the Fisherwomen (1962)

Ama traditional female divers in Japan. They dive into the sea and use specialized techniques to harvest seafood. Clad in traditional white attire, they venture into the ocean using wooden boats or floats. While underwater, they gather fish and shellfish, and their work has a rich history and cultural significance. Ama's occupation is demanding, as they make a living from the sea while embracing the beauty of the underwater world.

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Last Mermaid by Peter Ash Lee

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fosco Maraini: The Island of the Fisherwomen, 1963

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Year 2 and beginning of Year 3

After the anniversary of his banishment and Zhen's reassurances, Zuko continues his aimless wandering. He's been getting sailing lessons from the Sazanami's helmsman, Myeong, and works his way up to sailing just with Ju Long and Bun Ma. Except their first solo voyage doesn't go to well. They are saved by some local fisherwomen. The captain of the fishing ship, Ticasuk, helps them get on track and gets her ear chatted off by Zuko as he lets loose his Yangchen (and airbender) fanboying.

Ju Long notices how Zuko is talking more about airbender culture and realizes he is careful not to talk much about it on the Sazanami. He and Bun Ma suspect they've fallen for FN propaganda and confront Zuko about it once they're alone. Zuko confides in them how he discovered the Air Army was a lie, but is scared of being labeled a traitor and ruining the war effort. Ju Long and Bun Ma declare their support in helping Zuko discover the truth and figure out what to do next.

Zhao pops up again and makes a tit out of himself interviewing the entire crew to validate the improvement shown in their recent performance reports. No one is really sure of his game, but wow his poor bookkeeper sure does seem done with his shit... In the aftermath of his visit, Ju Long and Bun Ma share their knowledge about the Air Nomad genocide with others in the crew.

Still aimlessly wandering, Zuko decides to start inquiring about Kyoshi Island at Iroh's behest. He still really wants to just go to a spirit gateway and isn't really passionate about any other avenues of research lol. In a random neutral port town, Koji and Zuko stumble upon a Southern Water Tribe woman, Atka, who's heard of Hui from Ticasuk, who also was from the Water Tribes, Zuko realizes belatedly.

The women of the Southern Water Tribe have integrated themselves in the Earth Kingdom and neutral port towns to gather information and allies for the SWT warriors before they head out. They heard rumors about Hui even before Ticasuk met him... and after she met him, well, they're starting to suspect his Avatar Yangchen research is a cover for researching how to be the Avatar.

Following Atka's wife's recommendation for spirit activity, Zuko heads to Foggy Swamp with Iroh and is immediately sucked into swamp hijinks. He keeps having visions of water and air people, an airbender boy, and a bright, flying impression of a dragon, but also keeps forgetting them. With the help of the swamp folk and the ruins of the water/air civilization in the great tree of the swamp, Zuko successfully makes contact with the Avatar! Well. An Avatar and his very-great-aunt :3 Akari and Yangchen direct Zuko to go to the North Pole to further his quest.

Except he hits a road block bc oh my oh dear the true aftermath of Zhao's obnoxious paperwork visit has hit. Almost all of Zuko's crew has been reassigned and there's nothing Zuko can do to stop it. He does at least manage to sneak into the port office to give everyone cushy, easy new assignments, and to get Bun Ma sent off with Ju Long. Before leaving, Bun Ma insinuates to Iroh that Zuko is on a path to challenging the throne, and she's willing to do what it takes to pave that path for him. Iroh passes Bun Ma a white lotus tile...

Crew gutted and unable to immediately leave for the North Pole, Zuko is pissy and being a complete brat. He makes a bad impression as he ignores everyone on board, and then blows up on Zhao's bookkeeper, Jae, who was sent to join the crew as his spy. But she's more than willing to play double agent. Many a new characters are introduced and there's hints of something big going on behind the scenes in connection to Lu Ten... The captain finally arrives and backs Zuko in his desire to run off to the NP. So Iroh has to relent. But before they go, they need resources and safe passage so... First stop: Omashu!

While Iroh reconnects with his White Lotus buddy, King Bumi, Zuko is stuck sulking around Omashu. He gets cornered by the Secret Tunnel musicians who make his bad mood their business. To deflect from his Emotions, Zuko talks about his special interest, Yangchen, instead. This leads to the music nomads making a song about Yangchen and her gang, but most notably the chorus is about Yangchen and Akari's love and union...

Iroh gets lectured by Bumi who, rightfully, suspects Zuko knows more than Iroh thinks he does. But Iroh is cautious to the point of being willfully ignorant of the hints Zuko's dropped. So while he trusts Zuko with the story of his own spirit quest in search of Lu Ten's spirit, the reason he's been so stubborn about Zuko going to a spirit gateway, Iroh's still silent about his own anti-war beliefs.

In the North Pole, Pakku grants Iroh and Zuko access to Agna Qel'a and its library on the condition they stay out of sight of everyone. It goes real well until it doesn't. Yue and Zuko meet and nerd out over their shared admiration for Yangchen and her gang. From Yue, Zuko learns a lot of myths and legends beyond Yangchen and gains a better appreciation for oral tradition.

Oh and, also, the Northern Water Tribe actually has roots in dual-bending practices instead of coming off the lion turtles. But, unlike every other instance of dual-benders, they actually have a story as to why they disappeared. So Zuko learns about the Rampant Hunter and the world's fear of mixed elements since his rampage. But there's hope to change the world now with the jerboa returned, and the water/earth narwolves who came out of hiding and revealed themselves to Yue. And of course Eggy waiting to hatch. Zuko shares about Eggy, and his real identity to Yue. They promise to be allies and honor their ancient familiar connection through Yangchen.

Upon getting back to the Sazanami, Zuko learns Iroh arranged for the crew to find the Northern Air Temple for him. So they run off there without much of a break. Teo and his dad welcome Zuko and Iroh. Teo takes Zuko gliding and Zuko is instantly in love with it. His mood is ruined in the temple, however, With a new appreciation and understanding of how much was lost since Air Nomads followed oral traditions like the NWT, Zuko is devastated to see the temple's mural ruined by the Mechanist's work.

However, Zuko is able to come to terms that it is not the refugee's fault that they don't respect a lost civilization. It all comes down to the FN and their war. He shares tales of Yangchen with Teo, who starts to recognize and respect the Air Nomads as his home's first inhabitants, and as role models for his own feelings about taking to the sky... Zuko leaves with a gift of a glider staff of his own. Iroh is so pleased.

Following this quick visit, and the realization that the war is Wrong full stop, Zuko isn't too sure what to do next. He thinks the spirits have been pointing him to bring freedom back to hatch his lóng, and in doing so he'll bring the Avatar back too. So he decides to try to figure out how to do that during an extended shore leave planned for the crew.

What follows is Crew Bonding time Pt 2 :3 Zuko becomes besties with Chanda, a Deaf engineer, and learns sign language. He also starts sparring with and gets to know Kavi, the weapon department head, a survivor of the Siege on Ba Sing Se, and, oh you know, Lu Ten's best friend (partner). Unbeknownst to Zuko (and Iroh), Lu Ten had started an anti-war resistance group, the Wings, that had been undermining the siege. When Lu Ten died, Kavi also almost died, and suffered from amnesia for some time. The other two leaders of the Wings, Jae (Zhao's "bookkeeper") and Fox, their spymaster, had to go underground to avoid being caught up in spy hunts.

So behind the scenes of Zuko making friends, the Wings are re-centering themselves and entertaining the idea of centering themselves around a new prince, if his beliefs happen to align with theirs. Which they do now. Zuko and the Wings joins forces to start a pro-airbender campaign, using the Sazanami as a test group.

Starting with a return to the Western Air Temple, Zuko takes his crew of a Best of Yangchen tour. They visit Lady Tienhai's statue for a picnic full of airbender recipe recreations. Zuko attempts to dive to find the island Kuruk sunk where Yangchen first waterbent. The crew learns the Yangchen song. Zuko gets some matching wing tattoos with Kavi and Amphon. All the while Zuko is making new friends and the crew is doubting their Fire Nation education. Oh and he's writing to Mai again.

We hit 2nd anniversary of banishment around here, but it passes without much fanfare this year. Zuko is too focused on his plotting and scheming to get caught up overthinking things again.

The gran conclusion to Zuko's field trips is rumors of the Avatar in the colony, Yu Dao. He doesn't find the Avatar, but he does find the mayor's daughter, Kori, playing vigilante by mixing fire and earthbending techniques. She was inspired by the Yangchen song to mix firebending with her earthbending and to protect the people of her city. In her, the Wings find a new ally and connection to Yu Dao. Zuko leaves feeling confident in all he's succeed so far.

Only to discover he's been way more successful (and reckless) than he realized bc Chanda's figured out the lies of the Air Army on her own and confronts him to confirm it. The Wings find another member on the Sazanami. :3

And now you're ready to read Ripples Make Waves!

Zuko's banishment journey so far: A Recap of LTF

A comprehensive summary of each part leading up to the latest, Ripples Make Waves, as requested by Anon. For an added bonus, a visual timeline of where each part falls! Huh, wonder what's happening at the end of autumn year 3...

Year 1

Zuko is banished and healing from the Agni Kai on his ancient warship, the Sazanami. First stop is the Western Air Temple, where he discovers a hidden room dedicated to his ancestor, Princess Akari, and a mysterious egg kept warm in a magical fire. The room is obviously made by Avatar Yangchen, who he was taught had betrayed Princess Akari which led to her death. But the dedication to Akari in Yangchen's home doesn't line up with that... Zuko takes the egg and keeps it a secret, but the seeds are planted to start doubting what he knows about history and the world.

On the way to find the Eastern Air Temple, Zuko starts connecting with his crew, first step is starting medical lessons with the ships medic, Koji. In their first port stop before the EAT, Zuko blows up on the port's commanding officer in defense of his ship's acting captain, Major Hifumi. This solidifies the crew's support of Zuko but oops making enemies in the FN Navy.

At the Eastern Air Temple, Zuko meets Guru Pathik. From him, he learns that Yangchen and Akari were childhood friends, brought together by Akari's spirit dreams. He also learns that Akari died protecting Yangchen, along side Yangchen's earthbending master, Huizhong. This knowledge makes him uncomfortable and he does his best to ignore it, instead focusing on Akari's spirit dreams. He bulldozes his way through his chakra with Pathik in hopes of connecting with the spirits and learning more about his mysterious egg. He can't complete them because his sound chakra is too obstructed by lies. Guru Pathik advises Zuko to discover the truths of the world on his own to eventually unblock his sound chakra.

Zuko decides he's not going to learn any more from the Air Temples and doesn't gun it for the next one. He wanders for a bit, not sure what to do next when he meets Zhao, who gives him a "lead" on the Avatar. The lead, of course, is false, but in the process Zuko is faced with the uncomfortable reality that people of occupied and neutral towns will be distrusting and scared of him if he presents himself as himself. This primes him to be willing to adopt an Earth Kingdom adjacent disguise when Zhao returns to give him another lead for Wan Shi Tong's library.

(He also bonds more with his crew and becomes besties with two of the youngest crew members, Ju Long and Bun Ma. They're from the colonies and open Zuko's eyes to more of the injustices he's been ignorant of.)

In his search for information about the Spirit Library, Zuko creates the identity of Huizhong (aka Hui), a colony-born, aspiring scholar named after Avatar Yangchen's earthbending master who is interested in researching Avatar Yangchen due to his namesake. As Hui, Zuko meets Professor Zei who is more than happy to share his research of Wan Shi Tong's library. Zei also shares his controversial research of ancient civilizations centered around original benders that could bend two elements. One of his theorized animals happens to be a fire/air dragon...

Armed with all he needs to know to search for the Spirit Library, Zuko and Iroh head into Gaoling to hopefully make contact with a sandbender tribe Zei recommended. Zuko meets Toph and they become fast sparring buddies. Toph helps Zuko meet the sandbenders, who were doing business with her father and weren't leaving the Beifong estate. Due to time constraints (and Zuko self-centered recklessness) Zuko strikes a deal by himself with the sandbenders for them to help him search for the library and leaves Iroh behind in Gaoling.

Sarnai and Ghashiun, the sandbender chief's children, are tasked with taking Zuko around on a sand sailer. Sarnai discovers Zuko firebending his egg and promises to keep his bending a secret. In exchange, they tell Zuko a secret about the Si Wong: they aren't just Earth. Once, they were earth and air, and they learned how to bend from giant flying jerboa who bent both elements. But the jerboa have been extinct for so long that they and sandbenders of air are more myth than history.

Ghashiun also learns Zuko is a firebender after he uses his fire to save them from a sand shark. He only agrees to keep it a secret if Zuko and Sarnai accompany him and some of his friends on a raid on a FN caravan. Zuko reluctantly agrees. During the raid, things almost go VERY south, but Zuko, in an act of desperation to help and not expose himself as a firebender, somehow bends the heat out of a firebender's attack.

With the help of Sarnai, he develops a new firebending technique that harnesses the heat of the world around him to bend. It allows him to use a sand sailer by himself, which is fortunate because a Knowledge Seeker appears and he has to leave by himself to follow it.

Finally at Wan Shi Tong's library, Zuko befriends the Knowledge Seekers. He researches the Avatar and comes to the conclusion they're stuck in the spirit world or something. He also researches airbenders and comes to the realization that the Air Army is a lie and the FN was in the wrong. However he's still very conflicted and has deluded himself into thinking that Sozin was tricked somehow, and that the royal family isn't aware of the truth.

While reeling from this discovery, not so giant flying jerboa appear! Wan Shi Tong has been giving them refuge all this time and they enjoy Zuko's heatbending, perhaps why they chose to show themselves to him. Zuko starts doing more research into Yangchen in hopes of learning more about his egg, and eventually is given Yangchen's memoirs by one of the knowledge seekers.

Zuko learns all about Yangchen's life and her friends. In the process, he also learns that his egg is a remnant of a fire/air society, a fire/air dragon called a lóng, and has been waiting to hatch for millennia! Wan Shi Tong cryptically tells Zuko that the lóng will only hatch when freedom has returned to the world...

World view shaken and a new quest on his shoulders, Zuko leaves the spirit library with the jerboa in tow. He leaves them for Sarnai to find and returns to Gaoling. After a quick visit to catch up with Toph, Zuko returns to Iroh and gets a serious lecture. Also learns that Sarnai and Ghashiun lied to their dad that Zuko was an airbender to explain him taking a sand sailer.

Iroh is surprised by Zuko's admiration for Yangchen and hopes this means Zuko has uncovered the truth of the war by himself... but in his probing, he freaks Zuko out. Thinking he'll be branded as a traitor to the FN, Zuko lies that all his research outside of Yangchen was done in the FN wing of the library. So he might admire Yangchen, but the airbenders changed since her time and became the army that threatened the FN in Sozin's time. Iroh backs off... willing to wait for when Zuko is ready to digest the truth.

Zuko wants to go off the spirit gateways and test his theory that the Avatar is lost in the spirit world. Iroh is adamantly against that lol. So Zuko is stuck wandering around for any sort of lead on spirits or the Avatar. To assist his search and identity as Hui, the crew banded together to get him an Earth Kingdom style sailing boat, which Zuko names the Air Lantern after Akari and Yangchen's fire/air bending form.

(Also, Zuko has started writing letters to the girls back in the FN after sending them presents he got while in the desert.)

The anniversary of Zuko's banishment comes around and he has a little bit of a freak out about it. Zhen, the head engineer of the ship, helps him talk through his emotions and in the process learns the truth about the Agni Kai, something that has been a well kept secret from the public despite Zuko thinking otherwise. Zhen has no qualms about spreading this secret now that she knows... Fuck Ozai.

Continue to Year 2&3 in next post :3

#ngl it was fun recapping the series as much as i could lol#anon seriously way more than you asked for but#here it is#tempted to make an oc guide too but#another time

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Within the Reach of a Sea Monster

(fondly nicknamed “The Ga/Ta-Matoran Fishing Trip”)

From the Journals of Takua the Chronicler:

The Ga-Koroan call it “Beyond Mata Nui’s Reach”.

It’s this point out on the ocean, way far to the east of the Naho Bay. The fishing vessels go out there on their deep sea voyages, at least a four day journey out. It’s there where the island of Mata Nui itself practically disappears. The island becomes a blip on the ocean and then whoop! it is gone, and you are surrounded by the endless ocean. Everywhere you look, there is only blue water for as far as the eye can see.

The fishing vessels pick up more than enough food for Ga-Koro and its neighboring villages. But there are other things out here too. It seems like everything is out here, of both the biomech and the completely organic kind.

But past the Reach is where there are creatures that I would truly call the dwellers in the deep. There are things out here that I can’t even put to words. You don’t run across them often, but when you do, it’s something that is imprinted on you. I’ve asked Turaga Vakama about them— his only response is that they are from the time before time, and they were probably ancient even then…

***

On rare occasions did Matoran get sick. A villager in Le-Koro would occasionally ingest a poisonous herb. A Po-Matoran from time to time would come down with heat stroke. But these cases were as extreme as they were rare. Most cures and resources were not far away from the villages, and the Matoran were largely able to live their lives on the island of Mata Nui without too much worry for their health.

As Maglya watched his crewmate Aodhan lean over the rail of the ship, he decided that seasickness was a whole other Kohlii game.

The unwell Ta-Matoran clutched onto the rail of the ship, struggling to keep himself upright as it pounded through the swells. Each time the boat came crashing down, he lurched over the side, trying his best not to spill his organics into the ocean.

Around them, Maglya and other more steady stomached Matoran worked furiously on the deck. A group of Ta-Matoran on one end of the ship sliced bunker for keras crab pots, while another group of Ga- Matoran sewed more bait into the lining of fishing nets. A third group in the middle of the deck sorted their most recent catch, pulling apart fish and crabs that clutched onto each other. The different types of catch were then cast down into chutes that led to the cargo hold below.

The crew sang together as they worked, their tune thundering over the deck— and Aodhan’s seasick groans.

Since I left the village

of fire oh so dear to me

I’ve ventured to the ocean

and taken ship to sea!

Since I left the village

I’ve become a fisherman

cast on a boat

and sailed on out

with many a Ga-Matoran!

Gone ‘re warmth

of home’s fire and the flame

Came out here a thinkin’

the ocean waves were tame!

Since I left the village

and sailed out towards the reach

I ‘aven’t seen Ta-Koro

nor the black sand beach.

Since I left the village

hauling lines for better weeks

Gather food for the people of the Spirit

While he slumbers in his sleep.

Whichever verse they thundered next was lost to Aodhan as Maglya clapped a hand on his fellow villager’s back. Aodhan looked to his side to see Maglya cast a large fish net off of the boat near where the two stood. The net fluttered in the breeze for a moment before hitting the surface and disappearing into the whitewater of the passing ocean.

“How do you hold up?” Maglya asked as he secured the line.

“Honestly….so lightheaded,” Aodhan groaned. He gripped the rail tightly as the ship cruised over a swell. “I should stayed on land… gone on the hunt with Jaller instead.”

Maglya frowned. When Turaga Nokama had asked Turaga Vakama for a few spare hands, a number of Matoran, including Maglya and Aodhan, were glad to volunteer to help their sister fisherwomen villagers. The voyage had for many days been nothing but grueling work, which no Ta-Matoran was ever afraid of. But the voyage for some reason gone longer than anticipated, they were still a ways from shore. As much as he would be like the next Matoran and tell Aodhan to drink some lava and toughen up, Maglya could see his fellow Ta-Matoran was not getting any better or being of any use up on the deck.

“A few hours below deck will do you good,” Maglya said. “See if you can get some of that Hareke to chew on. I heard it might help.”

Aodhan nodded, and began to stumble towards the crew’s cabins below. Maglya watched him closely before throwing another net over the gunwales.

***

Pelagia kept her hand firmly on the throttle of her ship, pushing the vessel at a steady pace along the ocean. While she did so, she stared intently out the window of the captain’s quarters at the endless blue ahead. The lens of her Akaku zoomed in and out as it scanned courses and channels that only she could see. Now that she was on her way, there was nothing that would deter her from her path.

Behind her, her first mate paid no attention to the ocean outside. Her gaze was instead fixed upon the map of the island of Mata Nui covering the large table in the cabin. On it were the eastern grounds of the island, notably the details of the waterways they now traveled through.

“So you plan to lure her… it… in,” the mate said, looking up from the map.

“Aye.” The captain nodded, but did not take her eyes off her course. “Everything else has not worked. We will lure it in. There is no way to find it out there. But it knows where we are coming from and where we want to go. Make it come to us, and we will deal with it closer to our turf.

The two of them were quiet for a moment as they watched the ocean go by.

Lucky fishing vessels who were able to get beyond the shallow seas around the island of Mata Nui, a deep sea land, which some called “The Reach”, told of miraculous catches awaiting.

Crabs and fish were out there in the farther reaches of the endless ocean, containing nutrients and awesome tastes that most of the Matoran seldom experienced. Pelagia had tasted some of those catches herself, and wanted to bring them home on her own ship.

Unlucky ships, however, were catching the attention of a creature that would not let them pass into deeper waters. Pelagia, despite a few of her predecessors’ failures, was determined to put an end to this creature and free the way towards the far Reach.

Silence hung heavy as hopes and fears ebbed to and fro in each of the two Ga-Matoran’s minds. They had traveled out here to help gather food for the villages, but real reason Pelagia had agreed to this voyage was the potential to hunt of this destructive and elusive creature.

Down on the deck, the hired hands of the Ta-Matoran were hard at work with their fisherman sisters. All that they knew was that they were gathering fish for the Koro. They had no idea of what was truly out on the ocean.

“These Ta-Matoran seem to have strength,” the mate remarked, putting those hopes into words as she watched the hired hands. “Hopefully it will be enough to help us subdue that… thing.”

Pelagia nodded in agreement. “Go to the armories below and ensure we have all that we need be ready. If everything is prepared right, they will rise to the challenge, and we will be able to see if the firespitters live up to how much they bolster about themselves.”

The door clicked behind the mate as she left. Pelagia watched her go down to the deck, then set her sights towards the blue ahead. Afternoon hung above the ship, but it would be night soon enough.

And then the real fishing would begin.

***

Nightfall a few hours later found the crew of Ta-Matoran workers following their sick crewmate to quarters below deck. Aodhan, curious as to what was going on above, eyed up each of them as they huddled in the galley together.

“Have we stopped?” Aodhan asked. Maglya and a few others shook their heads.

“It certainly feels like it, but the Captain is still pushing away at the throttle. The ocean is simply smoother sailing tonight than the afternoon.”

“I hope this means we are close to port,” Aodhan grumbled.

“She’s taken us out much further than past trips,” Maglya remarked as they passed around their dinner.

“That she did,” another Matoran remarked. “I have been watching the Red Star, and I could see it in a place in the sky ‘ve never seen it before. We probably went several days further south than usual.”

“We have been going north for a while though, so we have got to be almost home,” Aodhan said. “The Koro has to be within sight soon.”

“Why are we out so far though?” a fourth Matoran remarked. “Are the catches around the island really that little, that we have to go all the way out where we did?”

“Did anybody notice the eyepiece on her Akaku is different?” the fourth Matoran asked. Aodhan and Maglya both shook their heads and looked at each other. “I saw her looking at us from the window of her quarters. There is something… different about the Captain’s mask than before.”

“Maybe she went to Turaga Vakama for an repairs,” Aodhan suggested. The Turaga of Fire was well known for fixing masks of Matoran from all Koros.

“But what for?” the third Matoran wondered.

“To help us find the fish better,” Aodhan said matter of factly. He didn’t see any reason to believe otherwise. “Although we can’t use mask powers, I’ve heard of that Matoro in Ko-Koro using his Akaku to scope out the mountain Rahi while on the hunt. The Captain is probably just doing the same thing here.”

“Maybe there is something out there,” the fourth Matoran said, in a mock eerie voice. “Something more than just the fish.”

“I sure hope not,” Aodhan said. “I am having a hard enough time just getting through this ocean. I don’t think I could stomach the thought of something else out here.”

“There’s been… things that have washed to shore on Ta- and Ga-Wahi,” the fourth Matoran reminded them. “Don’t you remember those odd flower looking things that were lined with teeth? What about those pods of odd squid that Kapura was fishing up a few months back?”

“I am not much of a beach Matoran,” the third Matoran shook their head. “Stay mostly in the village, keep to the lava flows.”

“Well a bunch of stuff is definitely out there,” the fourth Matoran confirmed. “Perhaps she is looking for the thing that swallowed Marka’s ship. Heard it was a big squid with seven eyes and claws at the end of its tentacles that pulled the thing all the way–”

“Don’t even go there,” Aodhan protested, cutting off the rambling Matoran. “I only came out here for extra work. The thought of anything else under the waves other than what we are catching will make me sicker than I already am.”

“She has simply been working us hard this trip,” Maglya said. “She probably had her mask changed just so she can have a sharper eye on us.”

The chatter died down, each Matoran no longer wanting to continue the increasingly uncomfortable conversation. The group sat there in silence, each focusing on their own meal and their own thoughts. However, as they sunk into the worn and beaten chairs and benches, they could not shake that feeling that they were being watched.

***

The Ta-Matoran in the galley were actually the last thing in Pelagia’s scopes. She was in fact using her scope to stare down her mate in their current disagreement.

Between them was the report of the day’s catch that the mate had given Pelagia. All of the catch they had for today, all they had collected during the trip… she thought it would be a quick crunch of numbers, but Pelagia’s new plan had made turned this into a tougher conversation that the mate was not sure she could be on board with.

“You said that you had wanted to lure it in,” the mate said. “Now you’re saying you want to feed it… to put these villagers’ days, weeks of hard work down the drain…

“We’ve gone the way we should have,” Pelagia said, gesturing to her maps. “only to have it not show. This is the last way to get it to come to us.”

“What about food for the village?” the mate shot back at her. “What is the Turaga going to say when the ship shows up with nothing of the food promised to the village?”

“They will have the sea for the taking if we take this thing out,” was Pelagia’s reply. The mate pinched the bridge of her nose in frustration.

“There will be a mutiny if we do it,” the mate warned her. “Ga-and Ta-Matoran alike.”

“Only if this doesn’t work,” Pelagia said. “When this works, though, they’ll be scared for their lives. Mutiny will be the last thing on their minds.”

The mate looked over the carving of the report she had given Pelagia. She understood, but she didn’t support it.

“This is the real catch we are going for,” she said to the mate. “Fish come every day, but an opportunity like this is years in the making. Mata Nui is not much further. We are taking the chance tonight.”

There were a number of things that the mate did not say. They were still too far from the island for her liking. If this didn’t work they would be in a number of troublesome situations, one of more likely of them including ‘dead’.

“Head down to the hold, and when you do it, be ready,” Pelagia commanded. “We won’t have much time once this happens.” The captain was dead set on this, and there was no changing her mind. Swallowing her pride, the mate nodded.

“Captain,” she said. “I hope you are right about this.”

***

It was nearing midnight, and Maglya was now worn after the long day’s work aboard the vessel. Yet he was still awake, enthralled by the night ocean that he gazed upon from the crow’s nest. By all means, he should have wanted nothing more than to go to sleep, before the next day’s long and grueling work retrieving the pots that they had spent today casting. But there was something out there that kept him looking for more. Perhaps it was promise that home was very close. Perhaps it was the blackness of the ocean after seeing it blue for so long. Perhaps it was the stars overhead. Maybe even it was the Red Star, casting an eerie scarlet shine on the sea and the ship that reminded Maglya of working on the Ta-Koro lava flows at night.

He was no astrologer like Nixie in Ga-Koro or the crazy fellow fishermen he talked to below. As the boat drove through the ocean on this night though, Maglya could see that the stars were looking more like they did from their island home. Almost back to the Koro, Maglya thought with a smile.

Somewhere out there were all of the nets and pots that they had cast off through the day. Tomorrow they would circle back and pull them up, as they had a number of times in this voyage, and see what they had caught. There were much of the catch that the Ta-Matoran had pulled up that they found familiar. There were many biomechanical Rahi out on the sea— from Takea sharks to young Tarakava to keras crabs and eels— that the crew had been pulling up in the crab pots. But there were also other creatures that populated the endless ocean– from a clear headed dolphin like creature and various completely organic jellyfish to a large thing in a shell that crawled along the deck with a claw the size of a Matoran’s body protruding from its head– which they were finding. It wasn’t as extreme as what the other Ta-Matoran down below had been rambling about, but there were a number of creatures that had spooked the Matoran. Maglya was not sure of what to make of them. None of the Ta-Matoran did.

A glow from far off caught Maglya’s eye. Many of the bioluminescent sea life would follow the boat in the night, angler fish and feeder sea life, which had little sparkles of color that stood out from just under the ocean’s surface. However, the thing that rippled in the ocean nearby that glowed with a pink and yellow hue seemed different from the other creatures that trailed the boat.

Whatever it was, it bobbed in the water, noticeably nearing the ship. It didn’t move like anything he’d seen before. As it came closer, approaching with growing speed, it almost seemed as if it were a ribbon of light rippling through the water. Its glow from below beamed to the surface, making the ocean almost sparkle in the dead of night. Maglya was transfixed, leaning further over the rail of the crow’s nest to get a better look. He barely noticed the growing sound of sloshing as the waves around the ship began to crash.

But suddenly, the fast approaching glow seemed to fade. Whatever creature it belonged to, from what Maglya could tell, dove down in the water, heading to the depths. The water was suddenly dark, and Maglya, having leaned forward in fascination, was left scratching his head.

“What in Mata Nui’s name was that—“ Maglya began. However, he was cut short as a sheer force slammed into the ship and rocked it violently.

The Ta-Matoran clutched the rails of the crow’s nest as the ship swayed. The ocean, calm only a few moments ago, was now a mess. The growing, criss crossing waves that he had previously been ignorant to were everywhere, throwing themselves to create a mix of chaos on the night sea.

The crow’s nest bowed as the ship rocked, leaning down as if to meet the ocean. Maglya found the planks beneath his feet sliding away. He gripped onto the rails of the nest to keep himself from falling towards the ocean not so far below.

The ship straightened itself, bobbing slightly on the ocean’s surface as the approaching waves died out.

The creature reappeared on the other side of the ship, illuminating the night with its glow. Maglya, from as high as he sat, was probably the only Matoran to get a clear view of the creature. An elongated serpent-like creature swam through the night waters, weaving from side to side as it passed under the ship. Beneath the glow that emanated from its entire body, a silvery sheen could be seen covering it. Its head— the bobbing blob that Maglya had originally seen— pushed upwards towards the ocean’s surface as it swam, but it did not break the surface of the water. A single eye looked at the ship as it passed over, in an expressionless but somehow still rage filled manner.

“What kind of Rahi is that?” Maglya cried out.

“No time to wonder or explain,” a Ga-Matoran called as she scrambled up the ladder, pressing a speargun into his arms. “Join your brothers below!” she called as she scrambled back down to the deck.

The deck was suddenly bustling with activity. Ga-Matoran were dashing around, ushering Ta-Matoran into groups. Spear guns were thrust into the hired help’s hands. Maglya found himself bumping into his sleepy eyed companions, just as confused as they were. Everyone asked what was going on, but even after seeing the creature, the watchman only had a slight clue of what was to happen next.

A cry came from the crow’s nest where Maglya had just descended from. He looked up in surprise to see the seldom seen captain, Pelagia herself, up there, bearing a massive trident. As Maglya listened to her bellowing speech, he tried getting a glimpse of the weapon that was strapped to her back.

“Here she is! The real one!” Pelagia cried. “We came out here to fish the open seas, brothers and sisters. However, this creature, — the Oarfish— has kept us from the real seas out there and the real reaches. It is no Rahi of Makuta’s. It is something of this ocean, something of the deep seas that has thwarted us for months, years on end. Tonight is the night that we take it DOWN, and claim the far reaches of the sea for ourselves, the Matoran!”

There was a cheer from the group as the Ga-Matoran threw their fists up. Several Ta-Matoran joined suit, but others looked around bewildered at what they had gotten themselves into.

“Now ready your spears and your harpoons,” Pelagia called down to them, “for this is where the real fishing happens! Take—“

Whatever more Pelagia wanted to say was cut off by another blow to the ship. The creature had come around again for another ramming.

Orders were barked amongst the deck. There was a lot pushing as a mix of red and blue armor rushed to the edge of the ship. Maglya and his brothers found themselves peering over the gunwales of the ship, their spearguns in hand. Each aimed their guns toward the water, waiting for the creature to break the surface.

Another shift was felt in the boat. The water around the ship, almost blinding with the bioluminescent glow of the oarfish, was suddenly dark again. The Ta-Matoran, curious, lowered their spearguns for a moment. Something dark seemed to pour out from the ship, its dark outline covering the glow of the oarfish. Maglya squinted, trying to discern what the silhouette was against the glow of the creature.

It was only when the dark mass began to drift in the swirling currents did Maglya realize that it was their catch. The doors to the catch container on the underside of the ship had been opened, most likely by something in the captain’s quarters, and all of their catch was swimming and scrambling free into the ocean.

The keras, the fish of the endless ocean… everything in the hull that they had caught was now out there in the open.

Several cries of disbelief could be heard. Long days of hard work and back breaking hauling of crab pots and fishing nets. Pulling of heavy fishing nets that left the Ta-Matoran sore and exhausted each day. All the food that they had gathered in hopes of feeding their village, released and out there on the ocean

All of their hard work was done just so they could chum for this thing.

The oarfish took the bait though, sweeping in and swallowing hundreds of pounds of fish. The ship was largely left untouched as it did so, the sea behemoth staying several bio from the ship as it scooped several mouthfuls of food.

“Let them loose and grab her!” Pelagia called.

The spearguns were fired, flying through the air and into the water. They sunk into the body of the creature, catching its hide.

The oarfish immediately yanked against the impalements as it tried swimming away. It roared from underwater, trying to wiggle free of the grip of the harpoons and spears that had grabbed on to it. The hide of the creature glowed brightly in the spots where it was struck, as if it bled light instead of physical blood.

The beast was strong, and the tension on the lines connected to the harpoons was almost immediate. The Ta-Matoran were pulled to the edge of the gunwales as the oarfish thrashed. But the Matoran were able to steady themselves on the deck. Ga-Matoran came immediately to help their brothers to hold the creature steady.

Maglya used every ounce of his strength to hold on as the creature resisted, pulling back with the rest of his brothers. He could feel the tension of the Ga-Matoran side by side holding the line with him. They both struggled and panted as they fought to hold the line. Maglya could feel his jaw clenched. Every part of his body ached, but somehow he and his brothers and sisters were resisting the raw muscle of this behemoth.

The mate patrolled behind Maglya, handing out more harpoons for the gunners to fire. Several Ga-Matoran were tying off the lines to the cleats, in hope to free up the crew for the next volley.

The boat itself groaned as it felt the pull of the oarfish’s strength, creaking and leaning starboard while its entire crew resisted the oarfish’s pull. The mate was worried, looking at the state of the battle so far; while the Ta Matoran were living up to their name, they were barely holding onto the stalemate that they had with this creature. Giving the command to fire, the mate watched, hopeful that the next volley would potentially help turn the tide.

The next round of harpoons fired, sinking into the creature’s hide. It roared once more, thrashing about alongside the ship. Its rage was growing as it flailed about in the water. The crew grasped with all their might, holding onto the lines with their collective strength. The ship leaned hard starboard, dipping dangerously off keel. Cracking could be heard as the cleats endured the beast’s struggle.

The ship swayed violently, and the mate jumped, grabbing hold of the rigging that led to the crow’s nest. The crew were holding their grip on the ship, but the ship was starting to move with the creature. Unable to wriggle away, it was now towing the ship in its frantic flee.

“Captain!” The mate called, gesturing to the fracturing ship around her.

“This is where we make our move!” Pelagia called to her with a smile. From her back she grabbed what Maglya had glimpsed earlier, a long and sleek disc launcher. The mate’s eyes widened. The Matoran usually fought Rahi with bamboo discs, but these metal ones— which the Turaga called ‘Kanoka’ were rare and rumored to be powered. These could give the crew an edge in fighting this Oarfish monster, the mate knew, and she watched as Pelagia loaded one into the launcher, her eyes twinkling with madness.

The Matoran crew below struggled to hold on once more, and Pelagia wasted no time. Aiming the disc launcher, she fired the Kanoka. It flew towards the Oarfish, cruising in a way that the mate could hardly believe. Many bamboo discs were able to curve in their path to the target, but this disc that the captain fired seemed to move as if it were a Gukko flying through the trees. It went around the lines that crossed the deck, almost seeming to dodge any obstacle it encountered. The mate watched, almost unable to believe what she was seeing.

Waves of power rippled over the oarfish as the disc hit. The glow of the oarfish shimmered as the Kanoka bounced off its surface, and whatever power it seemed to possess took effect on the creature’s body. The creature roared in protest, feeling its strength falter as it felt the disc effect it. The Matoran felt the strength of the oarfish weaken, and gave a hopeful heave to continue to pull it into submission.

The oarfish was not done however. Even with its strength diminished, it was able to thrash violently against the ship. Whatever it had been hit with had truly angered it.

The creature chose to switch tactics. Instead of pulling against the lines, the oarfish decided to change direction, and slammed itself into the hull that it was being pulled toward. The lines slacked for a moment, and the creature felt the pain in its hide subside as it collided with the ship.

The Matoran were thrown about wildly, the lines slipping from their hands. They were scattered upon the deck like shells on a beach, landing on hard on their backs. Many of the crew tried to get back on their feet, to grab the lines and reel in this fish, but the Oarfish continued to ram itself against the hull and shake the deck so violently that they could not stand. A loud crunch could be heard below the deck, and many Matoran widened their eyes in shock.

“You better have another disc like that, Captain!” the mate called from the rigging. With one hand, Pelagia held onto the rails of the watch post, while with another she rummaged through her pack for another Kanoka.

“Grab the lines down there!” Pelagia called, as she reloaded the launcher. Her voice was hoarse and rumbling amongst the chaos. The Matoran below, caught between their fear of the behemoth and their fear of the captain, scrambled to grab any line they could.

Pelagia took aim to fire again. The ship jerked, and her disc was misaimed. It went soaring into the water. She cursed, and went to reload—

Below the water, the oarfish had enough. Turning itself, it swam headfirst toward the hull. Its size allowed it to break through the wooden and protodermic structure of the walls, and it thrashed as it entered the guts of the ship. For all the pain that it had caused the creature, the oarfish was determined to tear this interruption on the sea to bits.

A great crack resounded throughout the ship. Heads whirled as the Matoran listened. The boards beneath their feet began to shift, and the crew scrambled. The boat, now a shell for the angry oarfish, was being torn apart.

Above the deck, as they hung from the rigging, Pelagia and the mate themselves looked around in panic. “Where is it?” the captain roared, as she loaded another disc. The mate’s head whirled from side to side, unable to locate the creature. The crow’s nest shifted as the boat itself below cracked. The ship was sinking, and they needed to strike at the oarfish before it made the ship unsalvageable.

The burning glow gave its location away, to their horror. The oarfish burst through the ship, emerging in the ocean on the other side. Both Matoran saw it at once. Pelagia fired, as the mate pointed toward it.

The oarfish seemed to see the disc coming. It turned to face the ship, looking for the little villagers. As it did so, it caught the sight of the disc, and the two who fired it. It lashed out, charging at the ship once more. Whatever power was in the disc was negligible compared to the oarfish’s rage, and it bounced off the creature as it made a collision course with the ship.

The mast cracked now, and the crow’s nest giving a sharp bow toward the sea. Pelagia and the mate tumbled from their post, trying to separate themselves from getting tangled in with potentially lethal rubble. Pelagia had a disc in hand, trying to load it for one last fire at the creature. However, the sea met her before she could get the disc loaded, and all she could see was the terrible nighttime blackness of the ocean.

***

The mate woke with a start. Small waves of the coastal waters lapped over the broken edges of her “life raft”, jostling it enough to bring her back from dreamless darkness. She scurried to secure her grip on the piece of rubble as she bobbed in the water, newfound alertness flooding her consciousness.

All around her in the water there were dozens of other Matoran floating. They laid sprawled on other rubble, small bouts of surf sloshed over them. The mate was not sure if any of them were dead, but many looked worse for wear.

Looking around, she could see that they floated not far from shore, the tree line of Po-Wahi easily visible from the shallows she bobbed in. Had they drifted all the way to shore? It seemed too good to be true.

Another thing drifted in the shallows with them, something that concerned the mate: although it did not glow like it did that night, a large chunk of the carcass of the oarfish could be seen in the water with them. Numerous holes from the spears and harpoons could be seen peppering the carcass. She eyed it up, confused and worried at the same time. They had clearly caused harm to the creature, but there had been no way that they had torn the creature apart. She looked around for more pieces, including the head, but could not see anything further than the dozens of shipwrecked Matoran and the rubble that surrounded them.

Had they defeated the oarfish? Or was there something else out there that had done that to the creature?

#bionicle#bonkles#haunting#Mata Nui Hauntings#sea shanties#Matoran#sea monster#Oarfish#also on AO3#Also on BZP#Also on wordpress#been working on this for a while#Aqua Magna#endless ocean#moby dick inspired#spearfishing#much thanks to ghost-mantis but I'll elaborate in another post

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fosco Maraini, Island of the Fisherwomen, 1962. "In 1954, Italian anthropologist, enthnographer, and photographer Fosco Maraini took a small film crew to Hekura Hegura-jima, a small Japanese island famous for its female pearl divers. His photographs, which were later published in a book titled l'Isola delle Pescatrici (The Isle of Fisherwoman), documented daily life on the island and the divers in, under, and around the water." https://www.instagram.com/p/CT7oLlSgYCJ/?utm_medium=tumblr

186 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

reblog this if you’re a competitive fisherwoman looking for the edge, support competitive fisherwomen looking for the edge, or want to leave this man stranded on an island with just his failed product

#shark tank#this shouldnt be as funny as it is#i think cuz its supposed to be a professional setting#and this man gendered fishing#when he really didnt even need to

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

what if we kissed... and we were both japanese lesbian fisherwomen cats raising kittens together living on a little island...... jkjk unless 👉👈

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘One cup of kadak chai’: How Mumbai’s Koli women survived the coronavirus pandemic | Paroma Soni

One year ago, Hema Bhanji sat wearily outside her home, a makeshift two-story building in the crowded, twisting alleyways of the Versova Koliwada, Mumbai’s oldest fishing village. She was slicing deftly through the last of her fish, caught on the boat’s final trip before the Covid-19 pandemic arrived on India’s shores.

By her side was a woman nearly 30 years younger, helping to clean the catch while hesitantly eyeing the chunks of surmai being tossed into a plate. Hema sighed and looked at her friend with exasperation. “Take the fish. Staring at it won’t fill you up.” Nearly in tears, the woman thanked Hema and hurried across the road to her family. She had to cook the fish before her husband woke up from his evening nap. As for herself, Hema went to bed hungry that night. “One empty stomach is better than five,” she said simply.

If this were a few months ago, the two would have been flocking, along with hundreds of other Koli fisherwomen, to their open, women-run fish market nearby with kilos of fish, joyfully gossiping about their husbands, their work, and all the other daily dramas of the area.

What followed was a tumultuous year where they had to hold on to every last rupee. India’s infamously strict lockdowns had halted all fishing activity, bringing Koli women’s livelihoods and social interactions to a complete standstill. By late June, many of them had begun to run out of money and food for themselves and their children.

What was most remarkable about Hema’s act of generosity is that it was not born out of any singularly altruistic sentiment, nor was it an isolated example of friendship. A group doubly marginalised for their caste and their gender, Koli fisherwomen have had the odds stacked against them for decades.

Their average income has declined by as much as 30% since 2010, yet the Indian state does not sufficiently acknowledge their economic vulnerability, according to research by Dr Samir Jale at Shivaji University.

More than two-thirds of Mumbai’s Koli population of 200,000 is female, but their voices are seldom included in the city’s political processes. Despite these challenges, Koli women continue to be fiercely independent, financially, and domestically – a feat that is rare in a male-dominated country.

A network of solidarity

Legally classified as a “Backward Class,” Kolis are unofficially considered a lower-caste community since the British Raj, although their own definitions of the term are fluid. Widely considered Mumbai’s native inhabitants when the city was just a group of islands, Koli fishermen go out to sea – sometimes for months – while the fisherwomen take charge of collecting, cleaning, cutting, drying, and selling the catch across town.

The traditional lifestyles of this small-scale fishing community have been under increasing threat since the late 1980s, owing to the rapid urban development of the city and climate change. Increasing levels of water pollution, changing marine ecosystems, and destruction of mangroves, among other factors, have forced fishermen to go out even longer and further in search of fish, shrinking the already-low levels of income for most households. Many young Kolis are increasingly moving out of fishing in search of more stable jobs as the fisheries get more uncertain by the day.

With the men away and without any economic support as India’s economy liberalised at the turn of the century, this group of women began forming ties to solve small problems that arose in their daily lives. Sometimes this meant helping out with each others’ kids because childcare services were inaccessible to them. At other times it has meant sharing ingredients or cooking meals together when there wasn’t enough food. They gave money to women in need even if their own funds were tight. They spent time listening to each other’s anxieties, fears and dreams, particularly in fish markets that became their safe spaces. They shielded each other from abusive husbands or lent shoulders to cry on.

Over time Koli women’s small acts of kindness developed into a complex network of solidarity, shaping a sense of collective identity. Describing them as “existing within the cracks and fragments of society,” Dr Niharika Banerjea, a sociologist at Ambedkar University, explained that the Kolis’ informal structures of care arise both as a result of the economic and gendered injustice they face, and in resistance to it.

“This is a community that has been marginalised for so long,” Banerjea said. “To survive, they have had to create alternative forms of living that do not prescribe to the dominant narratives of how society should be – based on caste, class, race, gender, and so on – and they have thrived.”

Emotional bonds

Unlike most women elsewhere in this overwhelmingly patriarchal country, Koli fisherwomen hold the decision-making power in households and in business. But outside of the Koliwadas, they continue to be denied access to their fundamental rights. So they use their collective power and informal networks to lift each other up as the state beats them down, especially during the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns.

“All of us, we have grown up together, spent all our lives around each other – and we have kind of been hidden from the rest of the world,” said Sheetal, Hema’s niece, who shifted from fishwork to a job at a local salon after getting married. “Sometimes we don’t get along, and some women certainly drive me crazy, but I can’t imagine a world where I would not stick up for anyone if they needed my help.”

These bonds are cultivated as much by the women’s compassion for each other as the infrastructure of their surroundings. “The strong cohesion between Koli women has always been a feature of the community,” said D Parthasarathy, a professor of Humanities and Social Sciences at IIT Bombay. “It is continually nurtured by the activities of everyday life, like in the way Koliwadas are spatially organised. Their houses look right into each other, their doors are always open, kids run through them all the time, and they do most household and business work together.”

As Koliwadas got increasingly encroached upon by developers, women began to combine the spaces between their homes into small courtyards, laying out all their fish to dry there instead of the big drying grounds they used to have. “We shared [physical] space for work and other things, but we also shared an emotional and fun space where we could just hang out,” said Hema, fondly recounting funny stories and encounters from the past few years.

Even faith reinforces the solidarity. “Koli women’s strong belief in their goddesses – not gods – strengthens their political identity,” said Parthasarathy. Though there are some Christian Kolis and Muslim Kolis, the majority are Hindu Kolis who worship seven main goddesses – including Mumba Devi, from whom the city of Mumbai gets its name. These goddesses symbolise harmony and unity, an important aspect in understanding the relationalities among Koli women.

‘Someone stole my air’

Most of the Koliwada’s communal spaces, however, closed off abruptly when the Covid-19 lockdowns were announced on March 23, 2020. The mandatory curfews and strict restrictions on movement brought fishing and all related fishing activities to a complete halt, including a shutdown of fish markets. Koli fisherwomen went from earning around Rs 100-300 per day to absolutely nothing. When the lockdowns began to ease, the annual 61-day ban on monsoon fishing to protect marine life came into force. Fisherwomen were forced to stay indoors for more than five months.

“The financial stress was one thing – at one point, we had no money even for buying vegetables,” remarked Bharati Chamar, a colorfully-dressed Koli fisherwomen in her 40s who sells fish in markets across Mumbai. “But being stuck with only my husband in our tiny house for half a year? I was bored. I missed the markets. It felt like someone stole my air.”

Mucky and densely packed, saturated with the smell of raw fish and the cacophony of enthusiastic customers, the fish market was the beating heart of these women’s friendships. “It’s not just a place of work – it’s the place their mothers went to, and their mothers before that, a space deeply enmeshed in their sense of identity,” said Gayatri Nair, a sociologist at IIT whose research focuses on Koli communities. “It’s a social, familial, familiar space that is thick with these relationships flowing through them.”

Ignored by the state

In a country that rarely accords visibility to women, hundreds of Koli women trading freely and controlling the cash flow in large public spaces is extraordinary. They not only participate in the labor force but also contribute confidently to how it is shaped, with generations of expertise. “Koli women manage the entire economic system of fishing within the Koliwadas,” said Ketaki Bhadgaonkar, co-founder of the non-profit Bombay61. “With their enterprising nature they make all the decisions about rents, budgets, household expenses, how fish should be processed and distributed. This rarely happens with women in other sectors.”

With less than 30% of the country’s women employed, a number steadily on the decline, India ranks 121st out of 131 in the Female Labor Force Participation Rate according to a World Bank report. Many Indian women stop working after marriage, largely because they are not allowed to by their husbands and in-laws. There are few labor protections or incentives for working women, in rural and urban sectors. Especially during the pandemic, more than 17 million women lost their jobs according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a higher percentage than men.

Although Koli women’s work lives are far more independent than other Indian women’s, they too saw their incomes vanish overnight, and received no support from the state. Two fishworker unions’ that advocated for relief were run by men. Their demands centered primarily around things like fuel subsidies, discounts on fishing nets, and compensation for hours lost on boats – things that are relevant for fishermen who go out to sea, but not so much the fisherwomen who work on land. The resulting government policies that passed applied nationally and, unsurprisingly, did little to aid fisherwomen.

“There is general disregard in our country’s policies for the work that women do, whether that’s unpaid labor in the household or in the fisheries value chain. It’s just assumed women will come and do the drying once the fish has been caught,” said Siddharth Chakravarty, a consultant on fisheries and public policy. He added that even though women in Koli communities do at least 2-3 times the amount of fishwork as men, they are not able to take out loans or avail credit legally unless they have assets to put down as collateral. These assets, usually land holdings or other property, are generally drawn out under the man’s name.

Informal safety nets

For women in the Versova Koliwada, that has meant finding refuge in their friends’ generosity when institutions failed them. Jagruti, a smaller scale “distributor” who bought fish wholesale from other fisherwomen and then sold it door-to-door, had no way to make ends meet. Her husband Ashok, a dhol player for weddings, was also out of a job. They burned through their savings in the first month of the lockdown and were unable to take out any form of credit. The Maharashtra government had set up a ration stall which gave each Aadhaar card holder 5 kilos of rice and 5 kilos of lentils per month, but only Ashok had the identification card. Jagruti and their two young children have been waiting for their documents to process since 2013.

“After weeks of not eating a single full meal, I called my friend Seema and asked if she could make me just one cup of chai. We were saving up whatever little we could during lockdown in that silver box up there, just so we could afford some tea leaves,” Jagruti said, pointing to a rusted box next to a pooja space full of her seven Koli deities. “But with the electricity company tripling the cost of power, our water supply running out, the bank denying our loan, the kids’ school – we didn’t have a chance.”

She smiled abruptly. “I just wanted one cup of kadak chai to take my mind off things. The next thing I know, Seema shows up at my door with 10,000 rupees that the women have pooled together.”

This sharing of money is possible because some women who own their own boats, like Hema, are relatively more cash-rich, while other secondary distributors like Jagruti frequently need to depend on others – usually their husbands – when their flow of income falters.

“In an informal setting, these class differences matter less. Women with more means will gladly help women without,” said Nair. “But when you try to formalise these networks, the lines are blurrier. There’s a noted difference between women with trawlers, women with smaller boats, and women with no boats at all. This is especially visible when it comes to, for instance, an issue of voting and taking a trade union position on limiting the amount of trawler fishing.”

These conflicts have kept Koli women’s networks from being formalised, despite repeated attempts to form women’s cooperatives to leverage more political power. However, spontaneous forms of solidarity continue to thrive. “The relationships among Koli women and their informal networks are no less important or powerful than any formal ones,” said Shibhaji Bose, an independent consultant with the TAPESTRY research project.

“The Koli people – especially the fisherwomen – have always been central to the popular imagination of Mumbai,” said Bose, referring to old Bollywood movies and the city’s culinary traditions. “But the city has not paid Koli women any dividends. They are natives of the land, but have not gotten their fair share from the country’s economic boom. With their existence at a crossroads, they say it’s only their goddesses and their bonds that keep them afloat.”

The ways in which Koli women adapted their homegrown social structures to collectively survive the pandemic is indicative of their strength as much as it represents the deep failures of Indian society and state. Koli women opened up their homes, risked their lives and livelihoods for each other even as a deadly virus loomed, while many privileged communities instinctively turned inwards.

“We are proud people,” said Hema. “And we are proud of asking each other for help, and proud to be able to give it to our sisters who need it most.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fisherwomen and their daughters in their traditional costumes on the island Marken, The Netherlands, 1905

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Octopus and Seagull Paddle

Jane Marston

My inspiration for this paddle came from Maureen Davis, a photographer, who captured this amazing event with her camera as she was walking along the road at Ogden Point in Victoria, B.C. in April of 2012.

I was raised on a small island outside of Chemainus, B.C. My family members were fishermen and fisherwomen. We had a wharf where we docked our 48-foot seine boat. Under the dock, there was a lone octopus. As children we swam off the dock and that octopus would dart past us. We never had any fear of this graceful tenant.

At the yearly family summer seafood barbecue, I asked several Elder fishermen if they ever encountered a seagull being eaten by an octopus. They all shook their heads with a vehement no! One fisherman told the story of being grabbed by an octopus and nearly pulled into the ocean, saying if it were not for his friend, he would have been gone. They were all amazed by the seagull story. One Elder suggested the scarcity of real food for the octopus might be the reason it attacked a seagull. One is left to wonder and ponder this fascinating story.

On the handle of the paddle is a crab and fish. The crab has a start of the full moon. I put this here because the moon is prevalent in the tides of the ocean. These are also some of the food sources the octopus dines on. I enjoyed making this paddle. I spent many hours working on this design creating it to give movement and flow but always being aware of letting it tell the story.

Jane Marston

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

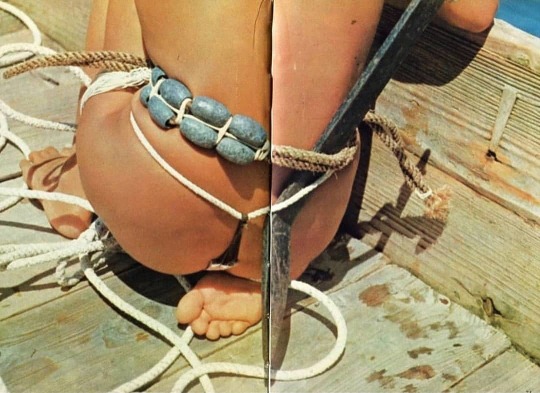

Fosco Maraini: The Island of Fisherwomen

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Climate change is "eroding a way of life" for Fiji's fisherwomen

Climate change is “eroding a way of life” for Fiji’s fisherwomen

A group of women in Fiji spend long hours trekking out to sea to gather an edible seaweed that, for years, has served as a vital part of the island nation’s diet, culture and income. But now, the seaweed is becoming significantly more difficult to find, putting the livelihoods of many at risk. Nama, also called sea grapes, is a form of seaweed known for its pearl-like structures. According to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Fosco Maraini, Offshore Hekura, Japan, 1959. "One of the most fascinating but lesser known traditions of Japan is that of the Amasan – which literally translates to ‘the women of the sea’. Honed by years of experience, the Amasan are professional divers who rely on their diving speed, lung capacity, great intuition and determination to succeed.While they dive for seaweed, sea cucumber and sea urchin, abalone is the most prized catch. The term ‘Ama’ dates back to as early as 750 AD and is found in ancient Japanese poetry recorded in the Man’yoshi." From "The Island of the Fisherwomen", 1960. https://www.instagram.com/p/CVvj0xYvO_o/?utm_medium=tumblr

75 notes

·

View notes