#The Hittites

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

One of the things I've learned as a researcher:

If you want to learn more about a place/topic but you've hit a wall exhausting what the primary sources from said place had to say about it, look up what the neighbors had to say about it!

(for example if you're doing research on a specific historical topic from ancient Greece and you've hit a wall looking up the POV coming from the ancient Greeks, look up what the Hittites or Egyptians had to say about it!)

I'm currently reading about the city of Troy from the point of view of the Hittites and I'M LOSING MY DAMN MIND!!!

So far what I've learned:

If Wilusa is the city of Troy then we have an exact location: The Hittites potentially called it Wilusa (LINK) and there's a map with the exact location of where Wilusa was. If Troy and Wilusa are the same city, then we potentially know the exact location of where Troy used to be. (Obviously like anything else regarding history, this information can be debated but it's still worth noting!)

An approximate date for the The Trojan war: There's a treaty document between the ruler of Wilusa and the king of the Hittites that dates the city to 1280 BCE (LINK) so we know the Trojan war happened sometime after that because the city was fine before 1280 BCE so Homer's Iliad and Odyssey is set sometime after that.

Why Apollo was on the Trojan side and helped Hector defend its walls: because Apollo built them!!! (LINK)

I'm still doing more research about it but I just wanted to pop in and give an example of what could be learned from researching the neighbors of said places in case you hit a wall but still want to learn more!

#the iliad#the odyssey#the Hittites#research#greek gods#apollo#greek mythology#homer#homer's iliad#homer's odyssey#hellenic polytheist#hellenic polytheism

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver rhyton in the form of a bull, Hittite, 14th-13th century BC

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

436 notes

·

View notes

Text

ganymede playing an aulos🪈with a phorbeia

more ganymede 🍎

#based on a hand fan design by george barbier 🪭#flourish is based on a fashion plate of a hittite kings shawl#greek mythology#tagamemnon#ganymede#zeus

953 notes

·

View notes

Text

vessel terminating in the forepart of a stag | c. 14th-13th century BCE | hittite

in the met museum collection

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

Puduhepa (c. 1300–c. 1215 BCE) was a formidable Hittite queen whose influence extended across politics and religion. Through diplomacy and faith, she left an enduring legacy.

Priestess of Ishtar

Born around 1300 BCE in Kizzuwatna, a region in southeastern Anatolia, Puduhepa was of Hurrian descent—one of the peoples within the multi-ethnic Hittite state.

Her father, Pentipsharri, was a priest of the goddess Ishtar, and Puduhepa herself served as a priestess. It was during this time that she encountered Hattusili, the future king of the Hittites.

Hattusili, then the brother of the reigning monarch, was returning from the Battle of Kadesh against the Egyptians when he stopped in the city of Lawazantiya. There, he met Puduhepa and her father. According to official accounts, Ishtar appeared to him in a dream, commanding him to marry her. Puduhepa thus became his chief wife, a union that appears to have been both harmonious and fruitful, producing several children.

Years later, when King Muwatalli died around 1267 BCE, his son Mursili III took the throne. At first, Hattusili remained loyal to his nephew, but the young king viewed his uncle as a threat and sought to curb his influence. Hattusili eventually rebelled and seized the throne for himself. According to some accounts, Puduhepa likely played a role in inspiring this coup, having received a divine revelation that her husband would be victorious.

Queen of peace

As queen, Puduhepa was a true partner in rule. She held the prestigious title of tawannana, traditionally granted to the reigning queen, which gave her both political and religious authority. She also presided over legal cases.

Puduhepa’s greatest legacy lay in her diplomatic efforts, which ensured peace and stability in the region. She co-sealed key treaties and corresponded directly with Pharaoh Ramesses II regarding the marriage of one of her daughters to him. Her letters reveal a skilled diplomat who was unafraid to assert herself, earning the pharaoh’s respect as an equal.

She also maintained correspondence with Ramesses II's queen, Nefertari, to whom she sent gifts. While only Nefertari’s reply has survived, it reflects a relationship of mutual esteem.

Puduhepa's seal

Shaping beliefs

Beyond politics, Puduhepa played a crucial role in shaping the religious landscape of the Hittite Empire. She composed prayers and liturgical texts, including one pleading with the gods to heal her ailing husband:

If Hattusili is accursed, and if Hattusili, my husband, has become hateful in the eyes of you, the gods; or if anyone of the gods above or below has taken offence at him; or if anyone has made an offering to the gods to bring evil upon Hattusili – accept not these evil words, O Goddess, My Lady!

She also promoted religious syncretism between Hittite and Hurrian traditions:

O Sun-goddess of Arinna, my lady, queen of all the lands! In Hatti you have yourself the name Sun-goddess of Arinna, but the land which you made, that of the cedar, there you gave yourself the name Hepat. I, Puduhepa, am your long-time servant, a calf of your stable, a [corner]- stone of your foundation. You picked me up, my lady, and Hattusili, your servant, to whom you married me, and he too was attached by destiny to the Storm-God of Nerik, your beloved son.

After Hattusili’s death around 1237 BCE, Puduhepa remained influential as queen mother during the reign of their son, Tudhaliya IV. She continued to wield political and judicial power, even intervening in legal disputes such as a case of willful damage to a ship. Despite attempts by her rivals to remove her, she retained her position.

Her last recorded letters date from 1215 BCE. While the exact date of her death remains unknown, she had lived through the final flourishing years of the Hittite Empire.

If you enjoy this blog, consider supporting me on Ko-fi!

Further reading:

Middleton Guy D., Women in the Ancient Mediterranean World: From the Palaeolithic to the Byzantines

Snograss Mary Ellen, Asian Women Artists, A Biographical Dictionary, 2700 BCE to Today

#history#women in history#historyedit#queens#puduhepa#women's history#hittites#hittite empire#bronze age#ancient world#ancient history#powerful women#anatolia#13th century BCE#female authors

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Rock-Cut Tomb Found in Courtyard of a House in Turkey

Found in the province of Şanlıurfa, the rock tomb features depictions of a reclining man and two winged women alongside an illegible inscription.

Archaeologists have found an ancient tomb carved into bedrock beneath an unassuming courtyard in Turkey.

Discovered in the yard of a house in the southeastern province of Şanlıurfa, the one-chamber tomb is decorated with sculpted reliefs that provide new insights into ancient funerary practices. Şanlıurfa’s governor, Hasan Şıldak, announced the find on social media this week.

One of the rock tomb’s walls features a relief sculpture of a reclining man leaning on his elbow. Another carving in the chamber walls depicts two winged women. Such images “offer clues about the beliefs and lifestyle of the period,” writes Anatolian Archaeology’s Oguz Büyükyıldırım.

The inside of the chamber’s door featured a painted inscription, though damage has rendered it illegible. While researchers haven’t yet dated the tomb, Şıldak says that its decorations are unlike others found at ancient tombs in Turkey.

Per Anatolian Archaeology, ancient rock tombs found in Şanlıurfa usually date to the late Hittite and Roman periods. The Hittite Empire flourished in Anatolia (present-day Turkey) between about 1400 and 1200 B.C.E., while the Romans began establishing rule in the region around the first century B.C.E.

Ancient Rock-Cut Tomb Found in Courtyard of a House in Turkey

The rock tomb is the latest discovery from the Şanlıurfa Cultural Inventory project, which aims to identify new historical assets across the province, as Türkiye Today’s Koray Erdogan reported in October. The provincial government collaborated with Batman and Harran Universities to assemble a team of nine archaeologists, architects and art historians to conduct the research. They’re hoping to record thousands of cultural assets, including 1,700 historical sites that are registered but poorly documented.

As project leader Gulriz Kozbe, an art historian at Batman University, told Türkiye Today, a comprehensive database is essential to protecting cultural artifacts and sites, which are always in danger of sustaining damage from humans or natural disasters—like the earthquakes that struck southern Turkey in 2023.

“Without documentation, the loss becomes irreversible,” Kozbe told the publication. ��Having a database would have accelerated restoration efforts in light of such disasters.”

The newly discovered rock tomb “is exactly the type of cultural asset the survey was designed to preserve,” as Artnet’s Adam Schrader writes.

The tomb’s centerpiece carving, the reclining man, resembles some examples of ancient funerary portraiture, according to the publication. He may represent the deceased individual who was entombed at the site, while the reliefs of the winged women could represent guardians watching over him from the afterlife.

The practice of carving tombs into rock was somewhat common across the ancient world. Turkey is home to many of these ancient tombs, including the striking Lycian Rock-Cut Tombs near the southwestern coast and the remote Kapilikaya Rock Tomb in the mountains of the north.

By Sonja Anderson.

#Ancient Rock-Cut Tomb Found in Courtyard of a House in Turkey#Şanlıurfa#ancient grave#ancient tomb#grave goods#ancient artifacts#archeology#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#hittite empire#roman history#roman empire#ancient art

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This map illustrates the vibrant trade networks of the eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age (circa 1500–1200 BCE), highlighting an era of growing interconnectivity among major powers. Goods, ideas, and diplomatic contacts flowed across land and sea, linking Egypt, the Hittite Empire, Mesopotamia, the Levant, and the Mycenaean world. These exchanges fostered a complex web of economic...

#History#Mycenae#Levant#Empire#Egypt#Aegean#BronzeAge#Hittites#Mediterranean#Mycenaean#Network#Trade

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

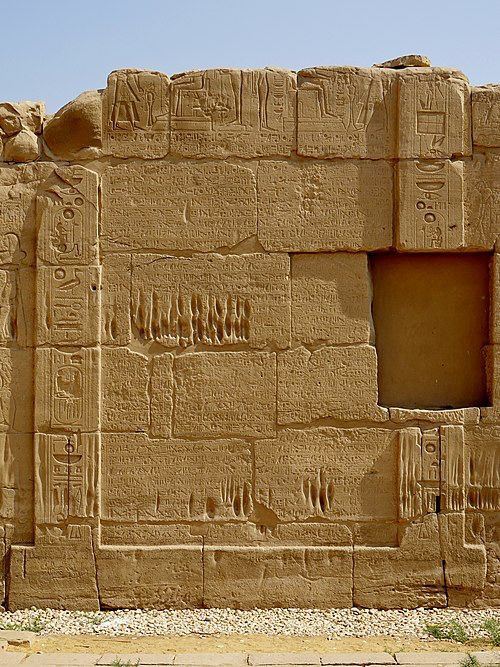

The Egyptian version of the Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty between Ramesses II and Ḫattušili III. This records the first surviving recorded peace treaty circa 1259 BC.

This is one of three surviving inscriptions of the treaty. Also known as The Treaty of Kadesh.

This inscription is found at the Precinct of Amun-Re in Egypt near the great temple complex of Luxor.

#egyptology#ancient civilizations#ancient world#antiquity#archeology#ancient history#egyptian history#ancient egypt#hittite#hittite empire#archaeology#ancient architecture#bronze age#artifacts#artifact#ancient artifacts

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illuyanka, the 248th Known One.

#Illuyanka#Hittite#mythology#dragon#smaugust#snake#its related to hydras and typhon etc so im forshadowing those designs here with the segments made of multiple eels#eel#Proto-Indo-European#992#octem 124#aer 4#Anatolia#Turkey#the Known Ones

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

Relief of the twelve Hittite gods of the underworld at Yazılıkaya Rock Temple, Türkiye.

#archeology#bronze age#ancient archeology#ancient#ancient history#ancient art#ancient sculpture#antiquité#antichità#anatolia#ancient anatolia#hittite#hittite empire#turkey#türkiye

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dreams of my father, the Hunter (Troilus and Āppaliunāš/Apollo)

I know there’s interesting discussion on whether or not Troilus is originally son of Apollo or not, but one of my sort of thoughts for my headcanon world is like…what if its a Schrödinger’s situation where whatever the truth is, that’s what he believes to be true, maybe in a childish fantasy way, up til the very end. Anyways I drew a more Hittite inspired figure, I think its neat how Āppaliunāš is known more for hunting being “one of Entrapment” while Cassandra in Lycophron’s Alexandra also curiously characterizes Troilus as the one who “smites” and “seizes” Achilles in an “inescapable noose” of doom. Just a thought. But here he is not thinking of that. He’s imagining having a nice warm hug

#troilus#troilos#troilus of troy#apollo#greek mythology#hittite mythology#Apaliunas#Āppaliunāš#lycophron alexandra

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

screaming, crying, and throwing up thinking of Hector and Teucer fighting against each other. How Priam and Hesione would have despaired seeing their sons trying to kill each other 😭

#friendly reminder that Teucer's name was Trojan/West Hittite in origin#Hector and Teucer should have been the best of cousins#do you think during Priam's death he would have found some comfort looking into his sister's eyes that her son wore#I'm going to write about them even though i know practically no one cares#hector#hector of troy#prince hector#priam of troy#priam#king priam#hesione#hesione of troy#teucer#the trojan war#the iliad#greek mythology#tagamemnon

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver rhyton in the form of a stag, Hittite, circa 1700 BC

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

535 notes

·

View notes

Text

ganymede and hebe doodles

more ganymede 🍎

742 notes

·

View notes

Text

stag poletop | c. 1400-1200 BCE | hittite, modern-day turkiye

in the cleveland museum of art collection

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seal of Tarkasnawa, King of Mira

Hittite, Anatolia, late 13th century BCE (Hittite Empire)

Luwian hieroglyphs surround a figure in royal dress. The inscription, repeated in cuneiform around the rim, gives the seal owner's name: Tarkasnawa, king of Mira. The name of the ruler was previously transliterated into English as Tarkondemos and Tarkummuwa. Other inscriptions naming Tarkasnawa of Mira are known, including seals found at Hattusa (the capital of the Hittite Empire) and the Karabel rock relief carving near Izmir, Turkey. Located in west-central Anatolia, Mira was a vassal state of the Hittite Empire. This seal, originally published in the 1860s, was purchased in Izmir by its first known modern owner, A. Jovanoff. Its famous bilingual inscription provided the first clues for deciphering Luwian hieroglyphs, which were previously called Hittite hieroglyphs.

241 notes

·

View notes