#The Fatal Englishman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

James Wilby's singing performances in his audiobooks and films, in order of appearance: Essays In Love, 2009. (Audiobook) The Wish List, 2003. (Audiobook) The Fatal Englishman, 2021. (Audiobook) A Summer Story: The Gentle Maiden, first appearance, 1988. (Film) A Summer Story: The Gentle Maiden, second appearance, 1988. (Film) A Handful Of Dust: Praise, my soul, the King of heaven (Praise, my soul), 1988. (Film) A Summer Story: New Every Morning Is the Love (set to the tune of "Melcombe," 1988 (Film)

#I finally finished it praise the lord#James Wilby#Many many listens and tracking down of scenes later#I'm so proud#A Summer Story#A Handful Of Dust#James Wilby and his singing voice#Audiobooks#Essays In Love#The Wish List#The Fatal Englishman#This took two days but it was worth it

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The stuff dreams are made of, or the interesting case of Anthony J. Crowley

We’ve talked a bit about Crowley’s trauma and his way of reclaiming the narrative in the past, but it’s time for some deep dive into the story he’s trying to tell. A story that meanders through the fabric of time and space, slightly changing with the human fashion trends, but slowly and surely bringing the demon closer to a certain angel like the red thread of fate.

1793

Some stories start in a garden, some even Before the Beginning, but this one starts with an Arrangement. Or, to be precise, a little bit after that.

See, most of the iterations of Crowley we saw throughout the history until then didn’t delve too deep into human cultural tropes. If anything, they were the inspirations behind more or less prominent biblical figures, maybe some nameless villains matching his demonic provenance and role assigned to him by his employers.

But in the hustle and bustle of the revolutionary Paris, Crowley emerges as a prototype of the Scarlet Pimpernel — a chivalrous Englishman who rescues aristocrats before they are sent to the guillotine. Stan Lee famously called him “the first character who could be called a superhero”.

Sir Percy Blakeney, the main character of the novel and the West End play under the same title, leads a double life. Appearing as nothing more than a wealthy fop, in reality he’s a formidable swordsman, a quick-thinking master of disguise and an escape artist. Even his own wife, Marguerite, has no idea.

Unfortunately Marguerite is being blackmailed with her brother’s life to find and expose the wanted Pimpernel. She regrets betraying her husband the moment she's forced to do it and spends the rest of the plot working to save him. She does, they make up, and return together to England.

In Aziraphale and Crowley’s case there was just a short stop for crêpes. But what seems to be an inspiration of a specific scene might as well come up later in the wider perspective of the show, so keep in mind those fragments of the musical’s libretto:

We all are caught in the middle

of one long treacherous riddle.

Can I trust you?

Should you trust me too?...

We shamble on through this hell

taking on more secrets to sell

'til there comes a day

when we sell our souls away.

We seek him here, we seek him there,

Those Frenchies seek him everywhere!

Is he in heaven? Is he in hell?

Where is that damn elusive Pimpernel!

1941

The London Blitz is when we see a full-fledged iteration of the superhero Crowley performing dashing and heroic deeds under the literal cover of darkness and air bomb smoke. In a bespoke double-breasted suit and a fedora — still free from the unfortunate modern connotations from the internet culture — he’s clearly channeling Humphrey Bogart as a private investigator Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1941) now.

It all starts with a woman and a simple plan gone wrong: Spade’s partner is shot dead, just like the man he was supposed to be tailing upon the request of a mysterious Miss Wonderly. And when a very soft-looking, sweet-scented man named Joel Cairo appears in his office willing to pay a hefty price for a "black figure of a bird", Spade starts not only a new job, but also his own quest for truth.

On the surface, The Maltese Falcon ends happily: the killer gets caught, and the hero winds up with the Falcon. But Spade's victory is completely hollow. The Falcon itself, originally meant as a symbol of loyalty, transforms into a symbol of a corrupting, futile, and self-destructive greed that makes people betray their own loyalties.

The treasure is just a worthless forgery and he’s fallen in love with the criminal — one of the first femmes fatales on screen. Despite his feelings for her and a kiss, Spade gives her up and submits the statuette as evidence, describing it as "the stuff that dreams are made of".

Remember the eagle lectern? The eagle was believed to be flying highest in the sky and therefore closest to heaven, symbolizing the carrying of the word of God to the four corners of the world. Aziraphale in the 1941 church scene is the closest to Heaven we’ve seen him on Earth. Just look at him: dressed in a smart, well-fitted coat with peaked lapels, symbolizing his Heavenly allegiance, and doing good this time not as a work assignment, but of his own accord. Being the closest to Heaven means the furthest and most unattainable for a demon like Crowley.

The Maltese Falcon is a metaphor for unattainability — things out of reach to desire and fight for, although never truly possess. It’s “the stuff that dreams are made of”. But Crowley secured the original — made of gold and encrusted with jewels, but hiding its real value under black enamel — eerily reminiscent of the demon himself and the unending kindness behind his inappropriately tight black clothing.

Quoting Michael Ralph — the production mastermind behind Good Omens — from the S01E04 “Saturday Morning Funtime” DVD commentary, “We wanted to tip our hat to the Maltese Falcon as being a precious object that no-one thought really exists but it does”. So we can safely assume that Crowley can and will achieve his dream in the future.

1967

Do you know what else happens in 1941 in Scotland? Ian Fleming, a British naval intelligence agent, meets with the famous occultist Aleister Crowley and asks him to lead the interrogation of newly imprisoned Rudolf Hess — a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany appointed Deputy Führer — given the two men’s shared enthusiasm for the occult.

This meeting has a significant impact on Fleming’s work as a writer; Aleister Crowley becomes the inspiration for his first villain Le Chiffre and creates a blueprint for most of the James Bond’s franchise ever since 1953, the publication date of the novel Casino Royale.

Meanwhile our Anthony J. Crowley believes in himself not being the villain he’s usually and sometimes forcefully painted as, but a superhero in disguise. The character of James Bond in particular inspires him so much that he buys petrol to get the limited You Only Live Twice (1967) window decals for his Bentley, dons his own tactical turtleneck, and sets off to organize a heist like no other. Sean Connery style.

Like a typical superhero, Crowley’s once again both saved and betrayed by his love interest. Aziraphale leaves him with a thermos of Holy Water, a faint smile, and a hope that they’ll soon match their speeds to meet halfway at the Ritz. The cancelled heist is not an ending, but a promise of a new beginning. And the fact that UK decriminalizes homosexual acts in the very same year is more than telling in this regard.

2019

An exceptional situation calls for exceptional solutions, and what’s more important than the impending Apocalypse? Demon Crowley does his best to put the arsenal of his 20th century film inspirations to good use.

"Ask yourself, do you feel lucky?" Crowley drawls, clearly imitating (although slightly misquoting) the titular Dirty Harry (1971). He’s hoping to be menacing and making the point of being the one on the right side of the law and history.

Some situations require more than quoting action heroes is not everything though. He knows what to do:

A jeep was heading purposefully towards the gate, and it looked as though it was crowded with people who were about to shout questions and fire guns and not worry about which order they did this in.

[Crowley] brightened up. This was more what you might call his area of competence.

He took his hands out of his pockets and he raised them like Bruce Lee and then he smiled like Lee Van Cleef.

'Ah,' he said, 'here comes transport.'

When in doubt, Crowley acts. He transforms into a combination of a stoic martial arts phenomenon and a sardonic, menacing character. His smile alone — even on Aziraphale’s angelic face, as seen in one of the final cut scenes — seems to be enough to ward off evil spirits, angels, and humans alike.

But we all know that even as breathtaking performances as those can’t protect anyone from the cogs of the Heavenly machine and its plans.

2023

No wonder that Crowley’s tactical turtleneck comes back in style after mere four years of retirement with a self-introduction “Former Demon, hated by Heaven, loathed by Hell. How will our hero cope?”. Something has changed during this time; he’s more mature now, not playing pretend by hiding behind the usual veneer of sarcasm and movie quotes anymore. Finally comfortable with the fact that this is his own story and there’s no need to become anyone else than himself.

The bookshop fire and the Heavenly trial still seem to haunt the demon in a way that makes him realize what all humans know: that every hero is his own biggest enemy. His ultimate dream might effortlessly change into his greatest nightmare any moment now, and the only thing he can do about it is hover in a two-minute distance from the epicenter of his feelings. But Crowley has no time to work on it when a new mission appears, to protect his angel from Gabriel and the combined powers of Heaven and Hell. Even if this — rather ostentatiously — is the last thing he wants to think about at the moment.

Crowley tries to plan ahead, while his story slowly warps into a different genre due to Aziraphale’s interruptions. He eventually changes back into his usual Henley shirt after agreeing to swap places and guarding the bookshop while the angel is off to Edinburgh, collecting more clues. Did he finish his personal quest off-screen? Did he just give up on it in the whirlwind of matchmaking shenanigans? Remains to be seen.

In the S2 finale our master of disguise in yet another turtleneck proves that he can successfully infiltrate even the universe’s back office. We don’t know where he drives off in the end, but one thing is certain — he’s got a plan. And a world (and his dream) to save, like a superhero he is.

#a turtleneck kind of day#crowley is a superhero#and a master spy#with a plan#good omens#good omens 2#good omens meta#go2 meta#ineffable husbands#crowley#turtleneck crowley#yuri is doing her thing

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

The following ficlet was written by @lazysaturdayonthebeach based on this photoset.

DarkHawk, T

You might also be able to read this story on AO3.

If you’ve enjoyed this story, please leave a comment either in replies or on AO3.

I Will Always Choose You

—

Cornwallis surrendered and the war was over. But that wasn’t good enough for George Warleggan, who lost several ships to the guns of the American Navy. He wanted personal revenge and looked for it by constantly questioning the motives of Ross Poldark’s frequent American visitor.

“I was born and raised in Bristol,” Jim replied when George started harassing him about his relationship with Ross one evening during a fete at Trenwith. “My mother still owns an inn there. I lived in South Carolina but I was an Englishman, like most Americans. What are you suggesting? You don’t agree with the King’s decisions?”

The bully was defeated for the evening and hated Jim and Ross all the more for it. No one could explain his constant anger with Ross. He had been at it since school and Ross was bored with his ill manners, but refused to engage.

Jim, on the other hand, was exceedingly annoyed and not afraid to point out George’s flaws.

One night, the reason became obvious. An unusually drunken George accosted Ross in a water closet and tried to kiss him. Ross just pushed him off and called a servant to take care of George.

A few hours later, George was slightly more sober but tried the same thing with Jim. Unfortunately, Ross spotted him following Jim. He yanked George off and threw him across the room. Only Jim’s quick reaction saved the Warleggan fool from a potentially fatal tumble down the stairs. Everyone saw and George was humiliated.

In revenge, he began suggesting that Ross’ relationship with the sailor was inappropriate. Despite several men of rank pointing out that George himself had several men that visited more often and more regularly, he would not let it go.

George’s Uncle Cary had the gall to mention it to Jim several months later on his next visit.

Jim had had enough. During his next voyage, he made arrangements to spirit Ross away to America where Warleggan had no influence. Jim might have only built his company back to three ships, but those ships provided him ample income and good standing in his community. Ross would be safe with him.

When word came from Trenwith that Ross had threatened George and the Warleggans were pushing for charges, Jim was in Bristol securing contacts. He left everything in the capable hands of his senior captain and raced to Nampara on a borrowed horse.

Ross was drunk. Jim stormed in and started packing for him. He plied Ross with kisses and more drink until he was completely willing to do as he was asked. Jim threw the bags over Seamus’ back and pulled Ross up behind him on the borrowed horse. They were sailing for America on the tide, Seamus included.

They fought most of the voyage. More than once, Jim threatened to have Ross keelhauled if he didn’t sober up and think straight. He never would, but the arguments were ugly. Jim was mad at himself, which did not help, sure that they should have left long ago.

Anchored off Barbados for deliveries, trading, and shore leave, the Eagle rocked gently. Jim napped in a hammock in the rigging. They had fought again the night before and he was avoiding Ross.

“I’m sober and I made coffee,” Jim heard shouted from the deck, “Please come down and talk to me.”

Well, that was a change, and an improvement.

Jim slid down a nearby rope and stood, arms crossed, staring at the infuriating love of his life. “What?”

Ross held out the coffee cup and waited.

Jim took a deep drink and sighed, happily satisfied. “This is good. Did you make it? Cook’s coffee isn’t this good.”

Ross smiled, relieved, “I did. And I may have bribed Jonah to bring fresh eggs, bread, and ham so I could make your favorite breakfast.”

Jim smiled too. He was so tired of arguing. All he wanted was to keep Ross alive and safe. Maybe he didn’t do the best job, but here they were, far from England, and no more Warleggan threat.

“I’m sorry,” Ross said quietly, “I can’t imagine how panicked you must have been.” He put a tentative arm around Jim and was accepted. “Can we go eat and talk?”

Talking lasted hours. Cook left dinner outside their door, knocked, and disappeared. Jim brought it in, wrapped in only a blanket. Ross lay across the bed, barely covered, exhausted, and utterly satisfied. Jim plopped the tray on the bed and stroked Ross’ sweaty curls off his forehead.

Ross smiled up at him, rousing to the smell of stew and biscuits. “Why are you here? I mean, I’ve been such an idiot. Why are you still here?”

Sighing softly, Jim replied, “To save souls. I thought you understood.”

A tear slipped down Ross’ cheek, “Will you save mine? I thought you doubted my feelings.”

Another deep sigh, Jim did that a lot since leaving Bristol, “That remains to be seen. I’m trying. And I did doubt, but that didn’t change how I feel.”

The journey from Barbados up through Eastern Caribbean islands, required more layers each day. They had smooth sailing, good weather, excellent trading, and not a single sighting of English colors, but the cool fall weather made itself felt. By the time the moored in Charleston, an unusually early snow dusted the ground and Christmas was only weeks away. Ross watched proudly as Jim made sure each crewman was well paid and given time to spend the holidays with their families.

Taking his own advice, Jim took his family, Ross and Jonah, to celebrate Ross’ first Christmas in America at Jim’s farm near Camden. The fields were bare after harvest, covered by a layer of white, but the farm was far from barren and quiet. Jonah’s children, and the children of several retired sailors, ran around laughing and making snow angels.

Ross laughed too, jumping down from Seamus and grabbing snow. He quickly formed a snowball and targeted Jim. Soon, they were barricaded behind a trough and a fence and joined by the children in a massive snowball fight. Adults stopped their work and came out to watch the chaos. Life was always interesting when Jim was home.

They spent Christmas surrounded by people who loved them and festive celebration. Ross thought it was his best Christmas ever and he hoped for many more together. After a huge meal of roast turkey, something Ross had never eaten before but loved, mashed potatoes, corn, carrots, and fresh baked bread, he slipped into a stupor of fullness and contentment in Jim’s favorite overstuffed chair. Jim locked the door to his study and squeezed himself in next to Ross.

Several hours later, Jim awoke to a nervous Ross kneeling beside the chair. He held a small velvet bag in his hand and puffed his cheeks on a few exhales. Jim reached out and stroked his cheek. “You okay?”

“Uhh…” Ross began, “I got you something.” He puffed again, clearly nervous. He opened the bag and took out a ring that matched his own, except that it was engraved with an H instead of a P on the signet. “I can’t marry you. I wish I could. I’m not even sure I can express exactly how I feel…”

Jim closed both his hands around Ross’ clenched fingers.

“It’s made with a nugget of Wheal Grace copper that I’ve carried around in honor of my parents and for luck.”

“You gave that up for me?”

“I gave up everything for you. At least, that’s how I felt. That’s why I was so angry and distraught. I didn’t feel like it was my decision.”

Jim dropped his hands and sat back.

“But it was. I was just slow to understand.” Ross reached out and took Jim’s hand. “I could have left at any port and gotten a letter of credit and passage back to England.” He paused and took a deep breath. “But I didn’t because I chose you. I chose you over everyone and everything I’ve ever known.”

Jim leaned back into Ross’ space.

“Remember when we talked about you saving my soul? You saved it. You saved me. I haven’t had a nightmare about the war, or the Warleggans, or even worried about my family since before Barbados.” He leaned even closer and touched his forehead to Jim’s hand.

Jim used his other hand to nudge Ross under the chin until they were looking in each other’s eyes again. “I will always choose you. Always.”

Ross slipped the ring on Jim and kissed him.

That was the best, but not last, present that Christmas. On Boxing Day, a messenger arrived from Jim’s lawyer in Charleston. He carried news of the tin strike at Wheal Leisure, along with a substantial letter of credit for the first year’s profits. They purchased a whole side of beef from the butcher in the town and had another feast the next day. Later, they purchased interests in several new railway companies with the mining profits, with the intent to expand Jim’s, their, shipping company.

They could have spent the rest of their lives as gentlemen of leisure, but a former British Army Captain and a former cabin boy turned ship owner weren’t ready to be idle. So they spent summers sailing and winters riding the rails to see the expanding American frontier. But they always returned to the farm for Christmas.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Youth of George Washington

The youth of George Washington (1732-1799), the first President of the United States, remains the least understood chapter of his life, shrouded in folklore and myths. Yet the experiences of his youth, and the bond he felt toward his older half-brother Lawrence, shaped the man he was to become and helped put him on the path toward revolution and the presidency.

Young George Washington with His Father

John C. McRae after G. G. White (Public Domain)

This article examines what is known about the lineage and youth of George Washington, from the first time his great-grandfather set foot on the shores of Virginia in 1657 until George's own coming of age in 1753, a year before the shots fired at the Battle of Fort Necessity changed the trajectory of his own life and, it can be argued, of world history.

Tall, strong, and somewhat physically awkward, the young George Washington grew up on a plantation just outside of Fredericksburg, Virginia, and moved to Mount Vernon as his brother's ward shortly after the death of their father. He became a land surveyor at the age of 16, measuring over 60,000 acres of land along the unmapped western frontier of Virginia. When Lawrence contracted a fatal case of tuberculosis, George accompanied him to Barbados, the only time he ever left the boundaries of the future United States; while there, he had a short but painful bout with smallpox, and for the first time came face to face with the military might of Great Britain. He had experienced much by his 21st birthday in 1753, although nothing could have prepared him for what was still to come.

Family & Parentage

The story of the Washington family in Virginia begins with a shipwreck. On 28 February 1657, the merchant vessel Seahorse of London ran aground on the shoals of the Potomac River during a storm; laden with precious tobacco, the ship had just embarked on its return voyage to England. Among its crew was a young Englishman named John Washington (b. 1633), who had taken to a life at sea after his father, an Anglican rector, had had his properties confiscated for his support of the Royalists during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). As the crewmen went to work repairing the Seahorse of London, John Washington befriended several locals including Anne Pope, the daughter of a wealthy Maryland planter. It was perhaps out of love for Anne – or perhaps because he spied more opportunity in America than on the open seas – that induced John to stay behind after the crewmen sailed the repaired vessel back to England. John Washington married Anne Pope in late 1658, with the marriage ultimately producing five children.

Before his death in August 1677, John Washington made quite an impression on his adoptive home of Virginia. He had purchased or inherited upwards of 5,000 acres of land, upon which tobacco was planted and harvested by both enslaved Africans and white indentured servants. John's eldest son, Lawrence (b. 1659) was therefore left with a decent inheritance and was perfectly poised to enter public service. Before the age of 25, he served as both the Justice of the Peace and in the House of Burgesses, cementing the place of the Washington family among the colony's landed gentry. Around 1686, he married Mildred Warner, the daughter of the Speaker of the House of Burgesses, with whom he would have three children: John (1692-1746), Augustine (1694-1743), and Mildred (1698-1747). Lawrence died an early death in 1698, after which his widow remarried to an English merchant, George Gale, and moved her children to Whitehaven, England, before she died in 1701. Gale took care of the orphaned Washington children, enrolling the boys in the nearby grammar school at Appleby.

Augustine Washington, the middle child of Lawrence and Mildred, returned to Virginia sometime before he came of age in 1715 to claim his inheritance. Called 'Gus' by family and friends, he was tall, blond, and muscular, and was said to have been as gentle as he was strong. Upon his 21st birthday, he inherited 1,000 acres of land as well as six enslaved people; his marriage to Jane Butler that same year added another 1,700 acres to his already considerable amount of property. The couple settled on Gus' main plot of land at Pope's Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia, where construction soon began on a home called Wakefield. It was here that Jane gave birth to three surviving children: Lawrence (1718-1752), Augustine, Jr. (1720-1762), and Jane (1722-1735).

Wakefield House at Pope's Creek, Virginia

Benson J. Lossing & William Barritt (Public Domain)

Like his own father, Augustine entered public life, serving as Justice of the Peace and sheriff for Westmoreland County. He also continued buying up properties, including a tract of land near Accokeek Creek, 8 miles (13 km) northeast of Fredericksburg. It was on this land that rich deposits of iron were discovered in the late 1720s; looking to capitalize on this, Augustine began negotiating with the Principio Company, an association of British ironmasters and merchants, to construct an ironworks on the land. In 1729, Augustine went to England to finalize negotiations with his new business partners only to discover upon his return that his wife Jane had died. Distraught though he was, it was not customary for Virginian widowers to stay single for long, and, on 6 March 1731, Augustine Washington was remarried to 23-year-old Mary Ball.

Continue reading...

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Hell of a Love (Book 1) Chapter Thirteen

Sebastian Michaelis x Demon! Reader

Chapter Thirteen: One Hell of a Prince

Summary: Sebastian, (Y/N), and Ciel find a strange prince and his khansama in London.

“Have you still not apprehended the culprit, Abberline?!” cried Lord Randall as (Y/N), Sebastian, and Ciel walked up to another crime scene of an Englishman being hung upside down naked in the street.

“I-I am profoundly sorry, sir!” said Abberline.

“Failing to catch Jack the Ripper, doing nothing but putting feathers in that brat’s cap…” Randall huffed.

“That brat? Do you mean Ciel Phantomhive?” said Abberline as he looked over case files. “I cannot help but feel he bears some immense burden even though his is still but a child.”

“A child?” remarked Ciel, leaning over to see Abberline’s files without announcing himself. “A series of incidents targeting those who have returned from India?”

“Master Ciel!” exclaimed Abberline.

“It seems there haven’t been any fatalities yet,” said Ciel. He stepped up and took another paper from Randall’s hands. “ ‘Crazy and lazy children, huh?’ ” He read from the statement of the perpetrator. “The culprit’s choice of words is very accurate. I also think this country would be considerably better off without the nouveau riche who cam back from India. At any rate, this mark is…”

“They’re making fun of us and Her Majesty the Queen!” declared Randall. “The culprit has to be Indian.”

“Ah, so that’s why I was called out,” said Ciel. “The vast majority of Indians who have been smuggled into the country are situated in the East End underworld society. Scotland Yard still has no idea of the exact number or their precise location, does it? There is no way we can sit idly by while the royal family is slandered. Let’s go, Sebastian, (Y/N).”

The small group walked along the port to where many suspects might live. As they walked, a man bumped into Ciel.

“Oh, so painful!” cried the man dramatically as more men surrounded them. “I think one of my ribs has fractured! Damn it, I might die!”

“This is terrible,” cried another man. “You should get compensation to pay for a doctor!”

“You better leave us everything you have,” said another voice in the crowd.

“We seem to have been surrounded by rather loutish thugs,” remarked Sebastian.

“So unfortunate. We should clear the way,” said (Y/N).

“Take care of this quickly,” said Ciel.

“Understood,” said Sebastian.

“Hey!” The man grabbed Ciel by the collar. “All the Indians around here have a grudge against you English!”

Which is fair, all things considered, thought (Y/N).

The man raised a dagger, and Sebastian flicked him in the forehead. The simple motion threw the man to the ground.

“Are you alright?” asked Sebastian with a smile.

“Yes,” said Ciel.

“You bastard,” growled the man. He raised his dagger again.

“Wait,” said a new voice. Everyone paused as a two well-dressed men, one with purple hair and the other with white, stepped out onto the street. One held a really terrible drawing. “We are looking for someone. Have you seen this person?”

“What do you want, you bastard?! Don’t interrupt me!” said the thug.

“Are you having a duel or something?” said the new man brightly. He blinked as he saw (Y/N) and Sebastian beside Ciel. “Oh, he has a khansama with him. Are you one of the English nobles?”

“And if I am?” said Ciel coldly.

“In that case, I shall side with my countrymen in this quarrel,” said the young man. He turned to the man following him, the white-haired one, and said, “Agni.”

“Yes?” said Agni.

“Defeat them,” said the man.

“Jo anja,” said Agni dutifully. He began to unwrap his bandaged right hand. “My right hand, blessed by the Gods, shall be wielded for my master.”

Agni ran at them. Sebastian grabbed Ciel and jumped out of the way, and (Y/N) blocked Agni’s attack, their eyes narrowing as Agni’s inhuman strength, yet he was as human as anyone. Agni adjusted quickly, turning midair, kicking, flipping, and striking with blows faster than the human eye could be. (Y/N)’s reactions were catlike with precision, perfectly timed with his attacks.

“I’ve hit your vital points several times now,” said Agni. “You should already be paralyzed. How can you still move?” (Y/N) smirked at his confusion.

“Hey! We were just passing through here!” said Ciel. “It was those men who looked to rob me.”

“What? You people, did you attack the little one over there for no reason?” asked the purple-haired noble. “That is not right! This time, my countrymen are at fault. Agni, take the little one’s side.”

That’s how easy it is to change is mind? (Y/N) raised an unimpressed eyebrow.

“Understood,” said Agni, and in a moment, all the men were lying in a heap on the ground. “It’s taken care of, Prince Soma.”

“Good,” said Soma. “Well, then, I was in the middle of looking for someone, so I had better be going. See you.” He sighed and turned away with Agni. “English roads are too complicated. Let’s head left next.” And they just…walked away.

What strange humans, thought (Y/N).

l

“I’m completely drained,” muttered Ciel once they made it back to the townhouse. “The culprit might have been one of those we saw.”

“Let us await Lord Randall’s report,” said Sebastian.

“Young Master, welcome home,” greeted the rest of the servants.

“If I keep getting called out to London for all these trivial incidents, there’ll be no end to it,” huffed Ciel.

“Ah! Earl, you really did come!” Lau opened the front door, not caring for decorum or invitations as usual.

“You’re always so unannounced!” said Ciel. “I keep telling you, if you’re going to visit, at least send a letter or something first.”

“Have you said that?” Lau’s memory was terrible as always.

“Since we have a guest now, I shall prepare some tea,” said Sebastian.

“Fine,” said Ciel.

“I’d prefer an English Chai blend,” said a familiar voice.

“Fi—!” Ciel’s eyes widened as he saw Soma and Agni standing in the doorway.

“Ah, I met them around the corner,” said Lau. “They said they wanted to meet the Earl.”

“Why are you here?!” cried Ciel.

“Why? We got acquainted earlier, did we not?” said Soma.

“Acquainted?” questioned Ciel.

“And, also, we saved you,” said Soma, walking confidently into the house.

“Saved?! In what way?!” cried Ciel.

“In India, hosting for those to whom you are indebted is common sense,” said Soma. “Is it the English way to throw such people out under the cold sky?” He walked upstairs casually to a bedroom.

“Who are you anyway?!” demanded Ciel as he threw the door open after Soma and Agni.

“Me?” Soma was lounging happily on the bed. “I am a prince.”

“A prince?” asked (Y/N). The rest of the servants peeked into the room next to them.

“This personage is the Bengal Kingdom’s prince, the twenty-sixth son of the King of Bengal, Prince Soma Asman Cadart,” said Agni.

“I’ll be imposing on you for a while, Little One,” said Soma.

Presumptuous. He’s going to be an irritating guest, thought (Y/N).

“Wow! A prince!” exclaimed Finny.

“A prince!” echoed Mey-Rin.

“This is the first time I’ve seen a real prince in the flesh!” said Baldroy.

“You may approach me,” said Soma. The servants crowded Soma with questions.

“So, you brought your servants with you this time?” remarked Lau.

“Yes. We have a guard dog to protect the manor while we’re away now,” said Sebastian.

“Well, that must be a relief,” said Lau.

“Sebastian, (Y/N), keep an eye on them,” said Ciel.

“Understood,” said Sebastian.

“Yes, sir,” said (Y/N).

l

“Master Ciel, it is time to wake up.”

Ciel’s eyes opened before jumping in shock. Agni and Soma were in his room.

“Namaste, Master Ciel,” said Agni, smiling.

“Why are you in my bedroom?!” cried Ciel.

“We’re going out, Little One! Show us around!” said Soma brightly, picking up Ciel.

“Why should I have to?!” demanded Ciel, trying to push out of Soma’s arms. “And I have a proper name! It’s Ciel, not Little One!”

“Then, Ciel, I ask that you be our guide,” said Soma. “Come!”

“Sorry to intrude,” said Sebastian, stepping into the room before Soma could run away with Ciel. “But the Young Master has studies and work duties to attend to today to today.”

“You’ll have to accompany yourselves,” said (Y/N), smiling.

“No, we shall stay and wait for Ciel,” said Soma, smiling as if that was normal.

(Y/N)’s nose twitched in annoyance.

l

Sure enough, Soma and Agni were not far behind Ciel as he practiced violin. (Y/N) watched in amusement as Sebastian, in a tutor outfit (which made (Y/N)’s eyes unabashedly roam him), instructed him.

Ciel played as best he could, and Sebastian listened for imperfections. The melody was interrupted, however, when the sound of prayers began. Agni and Soma had erected a statue of a Hindu goddess and were praying before it.

“What on earth?” asked Ciel.

“It seems they’re praying, but that’s a rather fantastic idol, isn’t it?” remarked Lau.

“I’ve seen Cults. This is reasonable for hu-people,” said (Y/N).

“All I can see is a statue of a woman carrying a head with a necklace of heads around her neck, dancing on the body of a man,” said Sebastian.

“She is one of the Hindu gods we worship, the Goddess Kali,” said Agni.

“Hindi gods, eh?” said Ciel.

“Kali is the wife of Shiva and a goddess of power,” explained Agni. “In far distant times, a certain demon recklessly challenged her to a fight. Of course, the goddess Kali won. However, after that, unable to quell her destructive urges, she went on a rampage of death and destruction. In a bid to defend the Earth, her husband, the god Shiva, lay down at her feet. Having stepped on her husband with unclean feet, the goddess Kali returned to her senses, and the Earth once again became peaceful. Kali is the great goddess who defeated a demon after a mighty battle. As proof of that, she has the demon’s head in her grasp.”

“So he says,” said Ciel, glancing back at (Y/N) and Sebastian.

“To think there was a god as strong as that…” murmured Sebastian. “I will have to be careful if I ever go to India.”

“I rather liked Egypt when I traveled there,” said (Y/N). They smirked. “I convinced some people to worship me.”

“Well, then, our prayers are concluded, so let’s go out!” said Soma.

“As I said, I’m busy!” said Ciel as Soma tried to drag him out again.

“What are you even doing anyway?” sighed Soma.

“You’re being distracting. Be quiet!” said Ciel. He picked up his fencing sword. He had practiced violin, now it was fencing. “If you want my attention so badly, then I’ll be your opponent!”

Soma excitedly took the other sword. “So, if I win against you, you’ll come out with us?”

“If you can,” said Ciel.

“Good luck,” said Agni.

“Well, then, begin!” said Sebastian.

Agni is going to be beaten, thought (Y/N). He clearly has no idea what he’s doing.

Sure enough, Agni swung the foil at Ciel’s leg, and it bent.

“There’s no benefit to hitting the foot with a foil,” remarked Ciel sarcastically.

Agni parried a few blows and huffed. “That’s unfair! I don’t know the rules!”

“A match is a match,” said Ciel. “It’s your fault for not knowing.” Ciel had the upper hand and was about to finish the match with a blow to the stomach.

“My Prince, look out!” Agni intervened. One hand held a cup to block the tip of the fencing foil, and the other struck Ciel’s pressure points, causing his arm to go limp. Agni’s eyes widened as he realized what he’d done. “M-Master Ciel. I’m so sorry. When I thought that His Highness was going to lose, my body moved of its own accord.”

(Y/N) raised an eyebrow. Agni seemed to have some honor, even if Soma seemed immature and naïve. They would remain careful around the unnaturally talented human, but they had to admit, he wasn’t the most intolerable mortal they’d met.

Sebastian noticed (Y/N) observing Agni, and his eyes narrowed.

Soma laughed. “Agni, you protected me well. I give you my praise! Agni is my khansama and belongs to me. Therefore, the win was mine.”

“Th-That’s ridiculous!” said Ciel.

“Oh, dear, Sebastian, it seems like the Young Master’s honor must be defended,” said (Y/N). They smirked and tossed Ciel’s fallen foil to Sebastian.

He caught it effortlessly. His eyes turned to Agni. Well, he had to prove a point now that the human had gotten (Y/N)’s attention. “Good grief,” he said. He masked himself easily with disdain at Ciel. “This happened because you teased an amateur who doesn’t know the rules.”

“My fault?!” huffed Ciel.

“Nevertheless, as a butler of the Phantomhives, now that my master has been injured, I cannot sit by and watch,” declared Sebastian. “All else aside, we’re ten minutes behind schedule.”

“So, that’s what you’re really irritated about,” muttered Ciel.

Not even close to correct, thought Sebastian.

“I will allow a duel,” said Soma. “Agni, in the name of Kali, do not lose!” Agni bowed and took the fencing foil.

“Sebastian, this is an order! Shut the brat up!” said Ciel.

“Make this entertaining, you two,” said (Y/N) brightly.

“Yes, of course,” said Sebastian, smirking.

“Jo, ajna,” said Agni.

“Begin,” said (Y/N).

Agni and Sebastian were instantly in motion. With each thrust and parry, they danced around one another. Both were perfectly matched for the duel with inhuman grace as they fought. (Y/N) watched in fascination. Agni was most definitely human, but his skills were equal to those of Sebastian at the moment. It was truly fascinating to wat

At the last moment, Agni and Sebastian both thrust their foil’s out, and the tips met. The foil’s bent. They snapped.

“Oh, my. The foils snapped,” observed Sebastian.

“The match is a draw,” said (Y/N), blinking in surprise.

“Ciel’s khansama is pretty good,” said Soma. “Agni is the best fighter in my palace. This is the first time I’ve seen anyone fight on par with him.”

Ciel walked to Sebastian and (Y/N) and whispered, “Just what is this man? He’s not one of those…” Reapers…

“No, he’s definitely a human,” said Sebastian.

“But with that power…He’s a likely suspect for the hangings,” said (Y/N).

Sebastian nodded. “Indeed. Hanging people would have been an easy task for him…” Perfect. (Y/N) would be wary around him instead of interested in any way.

l

It seemed that everyone else was having a positive reaction to Agni, as well. When Sebastian and (Y/N) stepped into the kitchen, they expected the usual chaos. Instead, Baldroy, Finny, and Mey-Rin were working well beside Agni.

“Thanks to everyone’s hard work, it looks like the food will be delicious,” said Agni.

“This can’t be real,” said (Y/N).

“Indeed, to have this lot helping you…” Sebastian didn’t have to elaborate.

“Everyone is born with their own talent,” said Agni. “They have a duty and path laid out for them by the gods. We children of the gods abide by that and do what we can.”

“You are a most well-rounded individual, aren’t you, Mr. Agni?” said Sebastian.

“Not at all. Until I met the prince, I was a hopeless fool,” admitted Agni. “I will be forever in his debt. I injured those around me, strayed from the gods, and accumulated many sins. Finally, my day of judgement came. Without leaving any attachment in this world, I would…have died. But Prince Soma gave me a new life. To me, who had not even believed in the gods, who had thrown everything away…A god appeared! Indeed, that day, I saw the holy light of God within the prince.”

(Y/N) raised an eyebrow. An interesting mortal.

“The prince is both my king and my god,” said Agni. “Therefore, I will use this new life to protect the one who gave it to me and grant as many of his wishes as I can.”

“Interesting,” said (Y/N), cocking their head. “You truly are devoted to him.” They had no loyalty to anyone in that. Well, almost anyone, but as a demon, they had to be ready to let go of attachments at any moment.

“Yes,” said Agni. He brightened for a moment. “Ah, and I wanted to say something to you, (Y/N).”

“Yes?” said (Y/N).

Agni bowed. “I apologize for fighting you when we first met. Had Prince Soma and I known our countrymen were at fault, I would not have attacked.”

(Y/N) raised an eyebrow. They put on a smile. “I am perfectly capable of defending myself against you, and you were following your prince’s orders as a servant should.”

Sebastian’s respect for Agni’s devotion to his master and pure humanity was quickly losing to his desire to throw the man out of the house.

Taglist:

@technikerin23

@im-making-an-effort

@izzieg3987

@jinxxangel13

@alexpangender

@otomyoli

@neenieweenie

@nex-crowley

@anxious-chick

@bellacastiel

@v1l-ismissing

@agentdedf1sh

#one hell of a love#x reader#x gn reader#gn reader#x nb reader#nb reader#demon reader#demon!reader#sebastian x demon!reader#sebastian x reader#black butler sebastian#sebastian michaelis#sebastian michaelis x reader#black butler x reader#black butler fic#black butler ciel#black butler#kuroshitsuji x reader#kuroshitsuji

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Closed starter for: @succiducus (Abdullah) Location: Training field Time: Shortly after the attack

“This cannae happen again!” Their voice roared like thunder. Their soldiers stood before them, bruised and battered, the anger upon their faces matching Cailean’s fury. “Chan urrainn dhuinn earbsa a bhith annta.” The officer seemed more like something that had crawled from the nightmare of an Englishman than the person they had been before the attack. Their fury was tangible; blood was still upon their shirt, their skin still tainted red from the blood that had been too stubborn to wash off. “They think they can walk all over us because we are small. They think we are desperate for their protection, but we do not need them; they need us! Let them try to touch our people again, and we will show them how fierce we truly are.” They continued in Gaelic, the only tongue they felt safe enough to speak to their soldiers in.

Cailean had long been known for bringing courageousness into the hearts of those who were too terrified to take another step into a battle, and that day was no different. The French were there, and they managed to ambush them; everyone was on edge, rightfully so. Their lips parted, ready to continue, but that was the moment when they saw him, and the mere sight of him somehow managed to steal their words from their lips and their breath from their lungs. Damn it. Their people continue watching them expectedly, no one daring to move an inch. Cailean turned to them again, clearing their throat. “Um- Get back to work; be vigilant, and do not trust them or anyone else.” With that, they waved them off.

For a long moment, they stood there watching him. He was safe… He was alive. Damn him. They thought to themself, the anger burning within them like a forest fire. He could have died. Someone could have easily killed him because he had been distracted, the most fatal flaw in any fight; he should have known better. Finally, they found the strength to march over to him while ignoring the stares of their soldiers which were burning through their back; damn him, damn him, damn him! Their anger had been a wildfire, raging through everything it touched, but the moment they stood face to face with him, it deflated into nothing but relief. He was safe; he was alive.

“Do you have a death wish? If you are so desperate for it, I’m sure we can arrange that quite easily.” It was all they could do to keep themself from screaming at him and the entire universe at the top of their lungs. How dare he? How dare he risk his life for them again? Despite everything, they reached for him, and they had almost taken his hand in theirs, almost. They only just managed to stop themself when there were mere inches between them. What would people think? They couldn’t…

“What the hell were you thinking?”

#* ⟢ CAILEAN & ABDULLAH ❮ thread 003 ❯#* ⟢ CAILEAN & ABDULLAH ❮ closed starter ❯#tw blood#tw injury#Me: I'm just gonna write a short starter#HA YOU THOUGHT

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

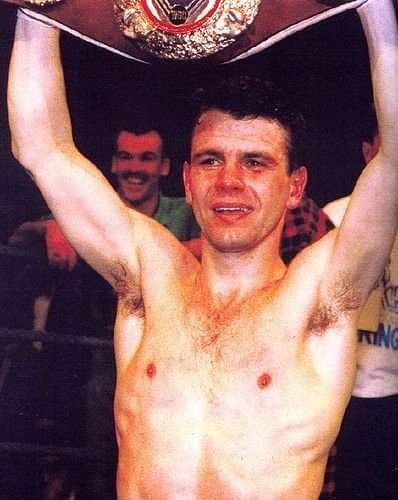

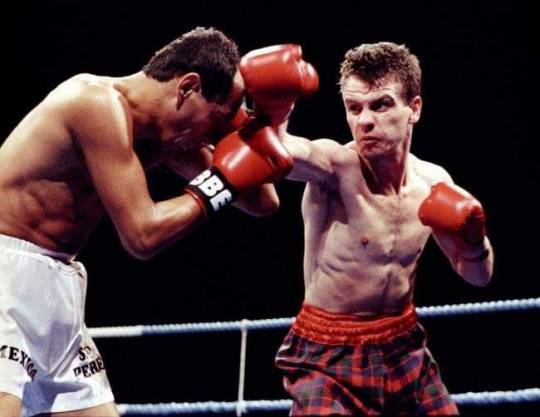

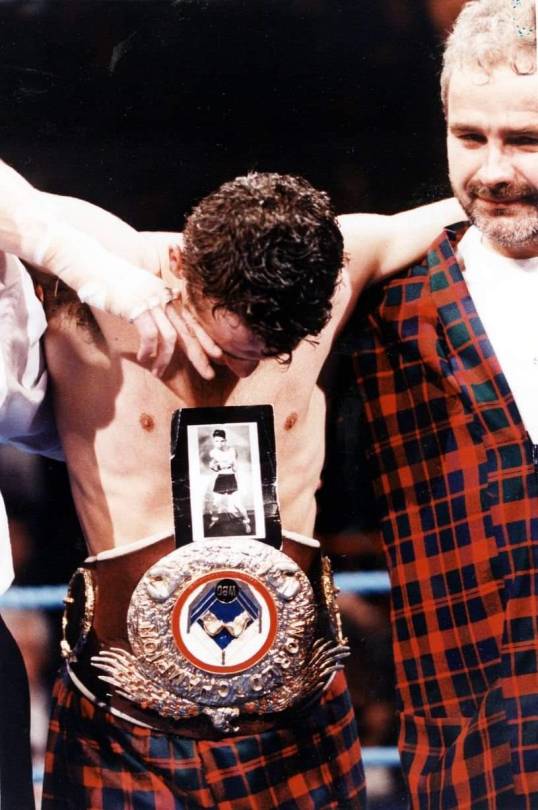

March 18th 1992 saw Pat Clinton become the sixth Scot to hold a world boxing title when he took the WBO flyweight Belt.

In an emotional evening in Glasgow's Kelvin Hall, Pat Clinton, made Dad Billy Clinton's dream come true for 12 months between when Pat outpointed defending WBO champion Isadore Perez from Mexico over 12 torrid rounds.

This famous ring victory prompted Clinton's manager and promoter, Tommy Gilmour, when asked post-fight if he would grant beaten Perez a rematch into the unforgettable reply: "No. The Mexicans didn't grant a rematch at the Alamo!"

Pat was born on April 4th 1964 at Croy, to Billy and Sadie.

Boxing was in his blood, his dad won the Scottish pro flyweight title in Perth in 1940, his uncle Jim fought and won two British A.B.A. boxing titles in 1944 and 1947.

Pat had aspirations to be a jockey but a fatal heart attack, which killed his dad Billy, in 1980, made Pat determined, instead, to realise his late dad's boxing dream of becoming a bona fide world boxing champion. In a 1990s interview Pat he said

"I owe my father Billy Clinton everything regarding boxing. He taught me everything - how to move, how to counterpunch, not to mix matters in the ring unless desperate, how to box for all my openings."

Pat was a member of Croy Miners Amateur Boxing Club. Clinton represented Britain as a Flyweight at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, losing only to the eventual silver medallist. Clinton turned professional in 1985 and won his first 11 fights.

In February 1989, Clinton faced Eyüp Can for the vacant European title, losing a unanimous decision. He made successful defences of his British title against Danny Porter and David Afan Jones before getting a second shot at the European title in August 1990; Clinton took a majority decision against Salvatore Fanni in Cagliari to take the vacant European title.

And so to the Kelvin Hall on 18th March 1992, Pat recalls that he had little memory of the build up and entrance to the ring, saying

"When I was walking to the ring there was an incredible atmosphere and it hit me like a sucker punch, I don't remember Ronnie Browne of the Corries singing Flower of Scotland or the fight even starting. In fact, it felt like I was going through the motions to begin with. “ he added "It was only when he landed with a jab that I thought to myself, 'My God this has started, I better get my finger out.'

It wasn't easy that emotion-filled night in the Kelvin Hall. Bringing dreams to fruition never is. After the halfway stage, veteran of 57 bouts Perez forced Pat, who had suffered the old Jackie Paterson curse of weightmaking problems, to fight out of his skin. Helped by a picture of his dad Billy Clinton, which was shown between rounds in his ring corner, Pat battled to a points win after 12 rounds.

It was a world title victory that provoked such emotional scenes of post-fight joy that even today promoter and manager Tommy Gilmour claims that this Clinton world flyweight win is still his most cherished boxing memory.

Still, weight problems continued to dog Pat as they had dogged other Scottish flyweight greats. As a result, Pat looked very unimpressive in beating Englishman Danny Porter in a WBO title defence at Glasgow's SECC Arena on points over 12 rounds in September 1992 - a poor performance stressed by the fact that Clinton had already previously stopped Porter inside five rounds at Watford in a British title defence in October 1989.

Eight months later and Pat, still plagued by weight and hand injury problems, lost his title to South African Jake Matlala, with Pat being stopped in Glasgow inside eight rounds.

An ill-fated comeback at bantamweight eventually petered out but today Pat Clinton can look back with pride on a career that saw him win World, British, European and Scottish flyweight crowns as well as being the first Scot to win a European flyweight title in Italy…as well as fulfilling his father Billy's dream.

In his thirties, as a result of perforated eardrums suffered during his boxing career, Clinton suffered tinnitus and started to lose his hearing, and had to start wearing a hearing aid at the age of 33. He returned to his trade as a joiner before going on to work as a salesman for Scottish Gas.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

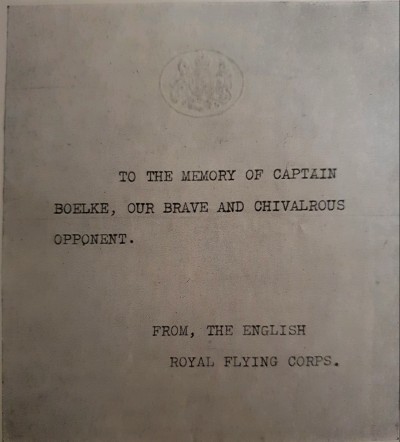

Oswald Boelcke - Part 3

Der Meister

The war diary of the squadron reads on August 27th, 1916: “Jagdstaffel 2 meets under the leadership of Captain Boelcke. Officers and enlisted men come from different departments. Existing: 3 officers, 64 non-commissioned officers and enlisted men. - Accommodation: officers live in Bertincourt, enlisted men in barracks. - Airplanes: there aren't any yet. - Activity: setting up the airport.” Boelcke had a lot of work to do in the following weeks to get the unit fully operational. In early September Richthofen and Boehme arrived, as well as Max Müller (a very successful Bavarian pilot, see: https://www.tumblr.com/subtile-jagden/714297390685929472/just-finished-this-book-about-max-ritter-von?source=share). On the 2nd September Boelcke used one of the three so far arrived aeroplanes and shot down his 20th victory. This highly puplished event hit like a bomb; after all, the people hadn't heard from Boelcke for almost two months. As Boelcke was almost the only one with a plane, he flew a lot and shot down five enemies in the first half of September. Finally, on the 17th September some more machines arrived so that the Staffel could fly together for the first time, resulting in victories for Boelcke, Böhme, Richthofen and Reimann. About his new students he writes his parents: “My gentlemen are all very passionate and eager and capable, but I still have to train them to properly work together – in their eargerness to achieve something, they sometimes still are like young dachshunds.”

Boelcke, like most of the pilots, had no personal contempt against his opponents: “We have nothing at all against the individual pilot, we only fight his flying against us.”

Just as they were able to complete their set-up, English bombers and artillery attacked Bertincourt, causing Boelcke to move his Staffel. By then Boelcke was able to up his victory list to 31. The fighting on the Somme weakened significantly, partly because the fighter pilots' excellent performance ensured that enemy aviators were no longer able to see behind German lines. Boelcke enjoyed great popularity with his men. He was strict and demanding but never without reason. “It is difficult to express with what devotion and love we clung to him in our inner circle of comrades. Never before has a comrade been loved by his comrades, a superior by his subordinates, as he has.”

In his last ever letter, Boelcke told his parents about his 35th victory on the 17th October. On the 26th he shot down number 40. On the 28th his life was over.

The End

The stress of the hard fights and worries about the future did not go unnoticed. “My captain became more and more serious and haggard”, reported Boelcke's orderly. On some day he went up seven times and on the ground he had a lot of organisational work to do. He was supposed to go on leave but “I am needed here!”. At seven a.m. first reports of English planes over the lines alerted Boelcke to start with his own men to fight them off. Four times they went up, all that before it was even noon. At around five p.m. they were called upon once more for help.

Oswald Boelcke is undefeated in the air. No enemy brought him down. It was unfortunately one of his own man who collided with him in what was a pure accident. Erwin Böhme, handpicked by Boelcke to join him and a great admirer of him, writes to his fiancé about the tragic event: “Boelcke and I had an Englishman between us when another enemy, being chased by friend Richthofen, cut our way. Boelcke and I, hampered by our wings, didn't see each other for a moment while we were avoiding each other at lightning speed - and that's when it happened. Our planes brushed against each other, just a light touch, but fatal at the high speeds. Fate is usually so cruelly unreasonable in its choice: only one side of the undercarriage was torn away from me, the outermost piece of the left wing was torn away from him. I had to see how he couldn't straighten his machine anymore and how he crashed next to a battery position. I was utterly distraught, but still had hope. But when we got there in the car, the body was already being brought towards us. He died instantly at the moment of impact. Boelcke never wore a crash helmet and didn't buckle up in the Albatros either - otherwise he might have survived the not-too-violent impact.” Manfred von Richthofen also reported on the incident: “I look around and observe how Boelcke is attacking his victim about 200 m next to me. A good friend of his flies by. Both shot - the Englishman was about to fall at any moment. Suddenly, an unnatural movement can be observed in the two airplanes. I had never witnessed a mid-air collision and had imagined it to be much different. It was just a touch. But at the speed that such an airplane has, every light touch is a violent impact.”

Interesting is the fact, that Richthofen doesn´t mention going after an enemy himself, crossing in front of Boelcke and Böhme. Maybe he did not realize that he did, maybe it was not something that the public should know. Richthofens account is in his biography “Der Rote Kampfflieger”, published at the hight of his popularity. To give the impression that he was partially to blame for Boelcke's death would be fatal.

In the end no one was to blame as it was a truly unfortunate accident. But of course Boehme was devastated. “Outwardly, I've got myself under control again to some extent. But in the quiet hours I always remember the horrible moment when I had to see my master and friend fall next to me - the nagging question arises again and again: Why did he, the irreplaceable one, and not I have to be the victim of this blind fate - because neither he nor I was to blame for the disaster?!”. When Boelckes family came to escort his body home, they met with Böhme and a friendship betweem them was formed that lasted until Boehmes own death one year one month and one day after Boelcke´s.

The death of this national hero sent a shockwave through the Empire and the German front lines. Boelcke is no more!

On the 31st October 1916 the funeral ceremony took place in Cambrai. The coffin was laid out in front of the altar of the cathedral. Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria appeared at the head of the generals, and General von Below represented the Kaiser. Manfred von Richthofen carried Boelcke's Ordenskissen (pillow with all his medals).

He was laid to rest in his home town of Dessau.

On the front the fight rages on. New pilots filled the gaps of the fallen. Inspired by Boelcke's spirit, best expressed by General Thomsen: "I want to be a Boelcke!"

Sources:

Boelcke, by Prof. Dr. Johannes Werner (1932)

Der Rote Kampfflieger, by Manfred von Richthofen (1917)

Briefe eines deutschen Kampffliegers an ein junges Mädchen, by Prof. Dr. Johannes Werner (1930)

Immelmann, der Adler von Lille, by Franz Immelmann (1934)

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It's a mistake to think of Macready and Forrest's performances [as Macbeth] as a showdown between highbrow purist and lowbrow crowd-pleaser: both performers today would seem wildly over the top. Shakespeare's Macbeth is bold yet contemplative, committed to a brutal path to power yet tortured by the consequences of that choice, leaving actors considerable leeway in how to approach the role. Yet the play didn't offer an opportunity- as, say Julias Caesar or Coriolanus did- to explore competing political views; the differences between British and American styles would turn on issues of character. Forrest, in keeping with how he approached most roles, emphasized Macbeth's boldness and played him as "the ferocious chief of a barbarous tribe," a warrior who furiously hurls a goblet over the head of Banquo's ghost and nearly strangles a messenger who brings bad tidings. Forest showed little interest in exploring Macbeth's reflective side or his guilty conscience...He had an intuitive grasp of what values his fellow countrymen identified with, and gave them a Macbeth, as one admirer put it, who was "a man there to do his three hours' work; brawlingly it may be, sturdily, and with great outlay of muscular power, but there's a big heart thrown in. Macbeth was Macready's favorite role. He offered playgoers a more thoughtful and tormented hero. Central to his interpretation was how much Macbeth's character is altered after killing Duncan. His "crouching form and stealthy, felon-like step of the self-abased murderer" in this scene was, for many, unforgettable...And when confronted by Banquo's ghost, Macready "brought out the gnawing of conscience and insecurity of ill-gotten power", his haggard features and restless moving making it seem "as if the curse 'Macbeth shall sleep no more' has taken visible effect." Some found in this approach too much intellect and too little heart. Others were annoyed by his interminable pauses, through which he conveyed to the audience a character steeped in thought (a prompter in Bristol nearly drove Macready mad by feeding him the next line at every long pause, assuming that he was having trouble remembering the part.) Macready, anticipating method acting by many decades, was probably the first to have said that "I cannot act Macbeth without being Macbeth." Shakespeare leaves unclear whether, when Macbeth tells Macduff "I will not fight with thee", he utters those words either cravenly or scornfully. Macready spoke them fearfully, and dies falling upon Macduff's sword, "in yielding weakness." In contrast, Forrest's manly Macbeth fights to his last breath. Even after Macduff disarms him and delivers a fatal blow, he manages to draw a dagger and, dying, "drives its point into the stage where it remains, quivering, by his side, as the curtain falls"- and the remainder of the play is cut. In this, perhaps more than in any other Shakespearean role, each man was understood as cultivating, and ultimately defining, his national character: Forrest the brash American, Macready the sensitive Englishman.

James Shapiro, Shakespeare in a Divided America

#shakespeare#history#theater#i am kind of cracking up at the thought of macbeth being ready to throw down with baquo's ghost#i support it#macbeth

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Girl Like Her

REBLOGS > LIKES

Inspired by this post by @stupidbitchwaifu

Mr. X × Femme Fatale!Reader

⚠️TW: Alcohol, gambling, one innuendo⚠️

A/N: Mr. X is 30, Y/N is 25

It was a beautiful night in Paris, France. Stars lit up the sky and the streets were bustling with civilians, basking in the activities of the night.

Just North of the Eiffel Tower, was an art gallery: Salle des Étoiles. Tonight, the rich and powerful gather for a night of auction, gambling, and extraordinary amounts of alcohol.

But, a woman with a wicked glint in her eye, and a man far too curious for his own good, have other plans...

"It's the quiet ones," Mr. X decided. It was always the quiet ones that drew him in.

He and his siblings had been speaking and Mr. X regularly found his gaze drifting away from the conversation at hand and towards a specific woman.

This mysterious woman had drunk her second flute of champagne and suffered through about three small talk conversations so far.

Mr. X experienced difficulty trying to decide who she was: He’d suggest a new-to-money winner of capitalism, but the woman carried herself with a grace that could only come from experience.

Definitely not an old money type either; she hadn’t once drifted over to the congregation of old money men who have been stalking the gallery discussing stocks and shareholders, as well as showing off their significantly younger trophy wives.

GM scoffed, seeing his brothers obvious disinterest. The elder brother turned around, seeking out what in the world could be stealing his brother's attention away from him. "What are you– oh."

"W-What?" Mr. X stuttered, holding his own glass in his hand, realizing that he wasn't as discreet as he thought he was, noticing his brother's snickering.

"You're interested in her, aren't you?" The GM crossed his arms. "You don't even know her name!"

Meanwhile, Kingpin was glaring daggers at this woman. "Who does she think she is?" She muttered under her breath.

This woman was a young, charming, and bold hacker that had everyone talking about her. What was so special about her that had everyone talking their ears off? She didn't look that special. Then again, she was still a rookie. "Give it a few weeks, Kingpin. People will be over her by then," The RHS leader told herself.

What a mystery, this woman was. Mr. X wondered if he had enough time to unravel her before he would have to get back to the main objective of the night.

"Don't even think about it," His brother cautioned. "Find someone else."

Mr. X very carefully took a sip from his champagne glass, tasting the excitement on his tongue more than the bubbles.

"Just because you're too curious for your own good and she's pretty and you haven’t gotten laid in five years doesn’t mean that you get to start ignoring us now!" Kingpin barged into the conversation.

Mr. X could only glare. They were right– he often did let his curiosity get the better of him, but he wasn't going to admit that.

There were, of course, much better things to do with his time which included tracking down where the beautiful muse had vanished in the moment that Mr. X’s eyes had wandered away. The gallery was only open for a few more polite hours and Mr. X intendes to enjoy at least five more minutes of witnessing something actually worthwhile before he has to get on with the night’s main event.

He sighed. "Fine," The Englishman said. "I'll be over at the roulette table if you need me."

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■

Y/N stood on the side of the room, leaning against a wall with a flute of champagne in her hand.

You carefully observed your surroundings, and the people in the room. God, these people are clueless! They're so up and over their heads about power that they haven't even caught on to your plan yet!

"My," A voice spoke from your side. "What's a beautiful woman like yourself doing all alone?"

Damn it, Halloween Hacker. "Remember Y/N, appearance is key," you told yourself, mostly to stop yourself from punching that bastard to New Jersey.

"Well, what's a man like yourself doing alone?" You asked him, wearing your signature smile that could make anyone do your bidding.

The two of you continued to converse, Halloween Hacker seemingly trying desperately– and failing, to flirt with you. Thus, you quickly lost interest, just the occasional chuckle and a nod.

You continued to scan the room, seeing if there were any old money men you could scam for their fortune. But, something much different caught your eye.

The famed Mr. X. You had heard of him, and the things he's done. He had it all: a successful corporation, money, and women were practically tripping over themselves to become his wife.

You smirked, knowing damn well that he was staring at you, but you didn't say anything. You could use him to your advantage...

"Say, Ms. Y/N," Halloween Hacker was quick to bring your attention back to him. "Would you care to join me at the roulette table? I heard that the Red Hood might be there,"

Your eyes lit up at the mention of the Red Hood. This could be your first round of your little scheme.

There was a fairly familiar glint in your eye; one of sinister, dark intent. Your smile only grew in size as you accepted the offer. "I'd be honored," You said, keeping up your facade.

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■

Mr. X and several other hackers sat around a table, a staff member shuffling and dealing them each five cards. He wanted to groan when he saw Halloween Hacker approaching, but nothing came out of his mouth when he saw who was accompanying him.

"Guys, look who I found!" He said, linking his arm to the Aphrodite standing beside him.

Her eyes scanned the table, as if taking in all the people who were sat down. Her gaze locked with that of Mr. X's, and she smirked as she gave him a wink.

"Y/N," She introduced herself, removing her arm from that wretched Halloween Hackers. "Y/N L/N,"

"Has anyone ever told you it’s rude to stare?" Y/N asked, a wicked smile spread across her face. Mr. X blinked for a moment, surprised and embarrassed to see that Ms. L/N knew that he had been looking at her. Her voice was more intoxicating than the champagne that Mr. X had just consumed, and he desperately wanted to hear more of it.

She wore an all-black suit, with a turtleneck with a small slit near the upper chest, showing just a tease of pretty skin that felt almost impossible to look away from. The suit accentuated Ms. L/N's figure, making her a masterpiece in the art gallery, and Mr. X thought it was a shame that he wasn't an artist, because he was willing to examine every aspect of the Magnum opus in front of him.

"Has anyone ever told you that you have the most captivating eyes?" Mr. X said, hoping to change the subject. He smirked under his mask when he saw Halloween Hacker getting visibly jealous. His empty champagne glass is dropped on the tray of a passing caterer whose face has nothing memorable about them compared to the sharp smile of the woman in front of him that makes him nearly forget how to breathe.

"Really?" Y/N raised an eyebrow, an amused look on her face that has Mr. X’s stomach fluttering already. "I wasn’t sure you noticed based on how you have been staring at my chest all night."

"Enough," Halloween Hacker interrupted, pulling out a chair for Ms. Y/N, immediately sitting in the empty chair beside her.

The hackers proceeded with their game of poker, the bet going higher and higher, until a few had bet their entire life savings on this one game.

"So..." Mr. X trailed off, trying to figure out a way to start a conversation with the woman sitting across from him. "I assume that there's a Mr. L/N somewhere?" He asked, his eyes darting around the room.

Y/N chuckled softly, getting a real kick out of the man's assumption. "There is no Mr. L/N, I'm afraid," you shook your head with a smirk.

Mr. X was taken aback, but relieved, knowing that he still had a slim chance of getting a drink with you sometime.

"Well, unless I'm being too forward–"

"Ms. Y/N, I must ask," Halloween Hacker intruded, stealing your attention away from Mr. X. "What made you join us here tonight?"

"I was invited," You answered. "Just like everyone else."

The game proceeded for ten more minutes, before you slammed your deal of cards on the table, revealing your cards. Halloween Hacker looked at the cards in disbelief.

"A royal flush..."

You did it. You won the life savings of several people, and Mr. X had just lost fifteen thousand dollars to you, and Halloween Hacker lost fifty thousand!

The hackers who were far more experienced than you and had been in this business for years, watched as you celebrated your victory. They all got up, walking away in defeat.

The only people left at the table were you and Mr. X

You smiled smugly, proud of your winnings. "What were you going to say?" You asked the man standing in front of you.

Mr. X blushed, fiddling with his collar. He sighed, "Well, I was going to ask if you'd be interested in getting a drink sometime, but–"

Before he could finish, the lights went out. People were confused, startled, and frightened. However, within a few seconds, the lights came back on.

The host and his wife stood at the front of the room, announcing their apologies and that they were currently investigating the matter, until multiple guests interrupted.

"My wedding ring is missing!"

"Someone has stolen my wallet!"

"My pearls, they've been stolen!"

To say that Mr. X was confused would be a drastic understatement. He patted himself with his hands, ensuring that he still had all his valuables– which he did. Until he felt something strange in his inner coat pocket...

It was a business card. On it, written in black ink, was a phone number. He looked around, making sure that no one had seen it, and tucked it back into his jacket.

Meanwhile, you were speeding down the French highway, on your way to the airport with multiple stolen goods. Once on that plane, you would be on your way to Germany, where you would repeat this act a million times over...

#virgil writes#rebecca zamolo#game master network#mr. x#female reader#fem reader#femme fatale reader#mr. x/reader#gmn#gmn x reader#game master network x reader#Spotify#tw alcohol#tw gambling#tw crime#tw theft

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

An unfortunate day for Berthold

22 May 1916

Since my engine had blown apart at one point during an air battle on 25 April, forcing me to make an emergency landing, I was to be given a 160-PS Pfalz. The aircraft, about whose type much was said, I was to try out thoroughly once. Unfortunately, the whole thing was just a deteriorated French knock-off. I take off, lift off from the ground and at the same moment the engine stops completely. I am at an altitude of about 100 metres. The bird sank down in a flash. I hear a splintering sound, feel a bump against my head, feel an insane pain and then nothing more ... The intense pain momentarily restores my senses: I unleash a fierce curse on those who, thinking I'm done for, not-so-gently yank me out of the mess. "He's ranting again, he's alive!", then a thunderous hurrah I hear, then it's night again. Once again I come to my senses and hear voices: "He might pull through, but he'll stay blind!" Then I scream, no, I roar with soulcrushing pain. I scream for the coup the grace ... Then night again!

25 May 1916

I wake up after long, long hours. I can see everything, even if not clearly. I'm lying in the hospital. A dull glow all around, everything so quiet. A woman with a glass of water in front of my bed. I only regained consciousness after 2 days. I can think clearly again and reflect on my situation: my crash was very serious. In 99 out of 100 cases, certain death! By throwing the little bird onto the left wing at the last moment, I at least mitigated the impact of the fall somewhat. The plane was completely destroyed. I suffered a complete fracture of my femur, upper jaw and nasal bone, as well as a fractured skull, a concussion and an injury to my optic nerves. The most terrible thing for me was the thought of having to lie here for weeks and months! In the next room lay the badly shot observer of the English plane that I had shot down a few weeks ago. He urgently asked to be allowed to see me, his conqueror. His request was fulfilled by opening the door to my hospital room when the Englishman came by outside... I'm struggling internally, especially since the start of the Somme offensive, where our airmen are missing. The nurse who looks after me, nurse Luise, tries to make everything easier for me and to help me get through difficult times. I will always remember her with gratitude. My dear comrades from the unit came as often as their duty allowed. With the Battle of the Somme, war as such ended. A miserable murder and slaughter begins. Hell begins! These incredible losses, these terrible injuries! The hospitals are all overcrowded. Doctors and nurses work day and night, their strength almost collapsing. Day and night they bring in the wounded, you hear the screams of the badly injured... I'm just now receiving the news that on April 29th my dear brother Wolfram, the theologian and Erlangen fraternity member, had a fatal accident near Lille during a gas combat exercise! I still can't believe it, it's a terrible blow to our family!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

this post is a big spoiler for Declare by Tim Powers, and is also my sales pitch for that novel:

the whole plot is pretty much “fallen angels (aka djinni) are real and they perceive the world in a mindbendingly alien way that makes them powerful enemies to any human that accidentally pisses them off, but also powerful allies to humans who can manage such an alliance; in the late 19th century, Tsarist Russia managed to forcibly make one into a guardian angel for the whole nation. during the Cold War, an extremely secret British governmental organization struggles to find a way to kill this angel, and thus destabilize the Soviet Union. they do this by having a guy non-fatally shoot Kim Philby with a magic bullet that, after Philby dies, the angel will ingest (because angels eat metal from dead bodies all the time). also the main character has an involuntary mind-meld with Philby from early childhood”

also it’s possible to read the overarching story of the novel as “Catholic Englishman, without meaning to, kills the biblical God”

what im saying is: Declare rules

1 note

·

View note

Text

A major theme of the Colloquies is the distinction between true and false piety. In “The Shipwreck,” a seafarer recalls a harrowing episode in which passengers aboard a storm-tossed ship make outlandish vows about the thanks they will give if they reach shore alive. An Englishman pledges heaps of gold to the Virgin of Walsingham. Another passenger says he will go to St. James at Compostela barefoot, bareheaded, and begging his bread. A third promises to dedicate to St. Christopher a wax taper as tall as himself in the tallest church in Paris. Amid them all, a woman calmly suckling her baby prays in silence. As the boat goes down, she is the first to make it to shore while most of the rest perish—a testament to the power of earnest devotion. (This colloquy would become one of the most popular satires of the sixteenth century.)

Fatal Discord (Michael Massing)

0 notes

Text

as an Englishman I’d like to sheepishly apologise for my nation’s sympathy with the Confederacy during the American civil war. I hope you’ll believe me when I say it had nothing to do with any racial element. It came about only, I assure you, via a mentality whose shortsighted acme goes as follows: time is money; material domination! [our cotton mills were uncommonly thirsty] — that and our fatal enthusiasm for any underdog, in any fray.

0 notes

Text

Timothy Garton Ash, historian and journalist, has spent his career chronicling the collapse of communism in the Eastern bloc and the political development of Europe toward—and perhaps now away from—greater unity founded on the values of liberal democracy. He has, in doing so, tried to represent what he takes to be those values and their relation to his own role as a public intellectual. The recent publication of his new book, Homelands: A Personal History of Europe, offers occasion to review that role, those values, and what may be their fatal contradictions.

Homelands is both a history of Europe after 1945, told from the perspective of a supposedly clear-eyed but omnidirectionally empathetic British liberal, and the story of how Ash, by falling in love with the continent on his schoolboy travels and post-graduate stints behind the Iron Curtain, came to cherish an ideal of Europe. With the right-wing, illiberal turn of many European governments in recent years as well as the departure of the United Kingdom from the European Union, that ideal looks increasingly less like the destination toward which history is moving than the heaven of a vanishing religion. But Ash’s intention, as it has been over the past 40 years of his career, is to insist that, as he concludes Homelands, “[t]o defend, improve and extend a free Europe makes sense. It’s a cause worthy of hope.”

Readers’ suspicions might be immediately incited by the juxtaposition of these two claims. Hope is a feeling to be roused in the face of good reasons for doubt; it is precisely not what “makes sense.” Hope is produced by the stirring rhetoric of the politician, not the careful scholarship of the historian.