#Te Arawa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Day 7 @tolkienofcolourweek: Elwing

Part 25 of toi's indigenous tolkien series

Faceclaim is Moriori and Māori. For Moriori albatross feathers are sacred symbols of peace

[image description

1: white waterfall, text in a circle 'she was born on a night of stars, whose light glittered in the spray of the waterfall of Lanthir Lamath beside her father's house'

2: blue moriori tree symbols, stars, text 'Elwing' and 'Princess of Doriath Lady of Sirion'

3: birds flying, text 'Elwing learned the tongues of birds, who herself had once worn their shape; and they taught her the craft of flight, and her wings were of white and silver-grey.'

4: a young woman with albatross feathers around her, text in a circle 'he gave her the likeness of a great white bird, and upon her breast there shone as a star the Silmaril'

5: lighthouse with bright light, text in a circle ' Therefore there was built for her a white tower northward upon the borders of the Sundering Seas; and thither at times all the sea-birds of the earth repaired'

6: big waves at sea, text 'As a white cloud exceeding swift beneath the moon, as a star over the sea moving in strange course, a pale flame on wings of storm.' and 'shining, rose-stained in the sunset, as she soared in joy to greet the coming of Vingilot to haven.']

#elwing#silmarillion#tolkien women of colour#pacific tolkien#maori tolkien#moodboards and edits#toi's indigenous tolkien series#toi's creations#tocweek2023#rāhiri mākuini edwards-hammond - moriori / ngāti kahungunu o te wairoa / ngā uri taniwha o hine kōrako / ngāti ruapani / rongowhakaata /#taranaki whānui / te arawa

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just been researching about Tom and John Hartnell and now I’m sad

On 24th December 1837, Tom joined HMS Volage. He spent 4 years on that ship (and presumably participated in the Battle of Chuenpi (1839) in the First Opium War. Tom returned to England and was paid off on 20th May 1841

Tom then signed onto HMS Tortoise on 24th May 1841 (yes, 4 days later) and spent 2 and a half years on that ship. It’s also possible that he was one of the men chosen to participate in a conflict between the Te Arawa tribe and Major Thomas Bunbury (commandant of a convict settlement at Norfolk Island, Australia) but it’s not known for certain

When he returned to England in the winter of 1843, it was to find that John had been on HMS Volage since September 1841. Tom didn’t join another Navy ship until 1845 (presumably to help his widowed mother look after his 3 younger siblings)

John returned to England and was paid off on 1st February 1845 and him and Tom had just over 3 months on land together before they set off on the Franklin expedition

They set sail on 19th May 1845 and had less than a year together before John died on 4th January 1846

From what I can work out, they saw each other for roughly 11 months, 1 week and 1 day in the space of 8 years

Excuse me while I go cry

#what better thing to do on a friday evening than make yourself sad about the hartnell brothers?#just something to cheer you up a bit after that#tartnell had freckles#and he had his initials tattooed on his right arm#franklin expedition#thomas hartnell#john hartnell#tartnell#jartnell#amc the terror#the terror#not really but it’s terror adjacent

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

OPINION: The national hui at Tūrangawaewae Marae saw 10,000 people united in the face of actions by the coalition government, including its proposed Treaty Principles Bill. John Campbell was there.

History happens on single days.

Yesterday, at Tūrangawaewae, will be one of them.

“Why are you here?”, I asked Tame Iti.

“Vibrations”, he replied.

The rest of us will feel them over the days and months and years ahead.

Initial estimates of how many people would come had begun at 3000. Then 4000 registered, so estimates grew to 5000. Then 7000. By lunchtime, organisers were saying 10,000 had arrived. There wasn't room inside for them all. A large marquee across the road was full, all day. Every seat, everywhere, was taken. There was hardly standing room.

This special place, which has held tangi for royalty, which is where the Tainui treaty settlement was signed, which was visited by Nelson Mandela, and Queen Elizabeth II, and many of our greatest rangatira, has seldom seen so many people.

But no one objected. To standing. To the steaming heat. To the fact that sometimes people were too far away from the speakers, or the screens relaying them, to hear.

New Zealand First’s deputy leader, Shane Jones, told RNZ the hui could turn into a “monumental moan session”.

But it didn’t. Somehow, the word I keep coming back to is joyful.

The National Hui for Unity it was called. And it felt like exactly that.

On the way to Ngāruawāhia early yesterday morning, I pulled into a truck-stop near Bombay, at the southernmost end of the Auckland motorway system, to meet the Ngāpuhi convoy travelling down from the far north.

Some had begun their journey way up, in Kaikohe, at 3am. They spilled out into the half light of an overcast morning and inhaled the beginning of what would be an extraordinary day.

It’s easy for the significance of this delegation to be lost amid all the other arrivals. The people who’d come from even further away. Iwi after iwi. Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou, Tainui, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu, Te Arawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Maniapoto – the big ten, all there, in declaratory numbers.

Just a few members of the Ngati Porou contingent who drove over on Friday from Tairāwhiti to attend the hui.

Ngāi Tahu representatives had taken a huge journey by road, then Cook Strait ferry, then road.

A friend’s father flew up from Invercargill.

But the size and standing of Ngāpuhi’s delegation provides some insight into how very significant this hui was.

Ngāpuhi aren’t a Kīngitanga iwi. They don’t see Kīngi Tūheitia as their king. And they contain Waitangi within their broad, northern boundaries – home, of course, to the Waitangi commemorations, our most famous form of national hui.

And yet they came, hundreds of Ngāpuhi. Some wearing korowai made especially for the occasion. Some the direct descendants of Treaty signatories. A waiata, composed for the hui, rehearsed beyond newness into a heartfelt and singular voice.

“Why are you going?” I asked Mane Tahere, the chair of Te Runanga-Ā-Iwi-Ō-Ngāpuhi. “It feels significant that Ngāpuhi are attending in such numbers.”

“Because”, he answered, “the challenges we face do not discriminate amongst iwi. We held three hui to discuss whether we should come, and who would come, and what our message would be. The final hui was only last Saturday. I wouldn’t have put our rūnanga resources into something we didn’t collectively support. This was hapū rangatiratanga. Hapū after hapū spoke and said we should go.”

Why?

“Because the question we have to ask as Māori is how we activate ourselves, re-activate ourselves, for 2024? How do we say to the coalition government, ‘hang on, what do you mean, and what are you doing?’ And the best way to do that is to do it together. Now is the time for Māori unity.”

The National Hui for Unity was only called by Kīngi Tuheitia Pootatau Te Wherowhero VII (Kīngi Tuheitia) at the beginning of December. That so very many people would arrive here, only six weeks later, in the holiday-season slowness of the third week of January, speaks not only to how resoundingly those present reject the coalition government’s Treaty Principles Bill, but also to a strength of unity already existing.

That is to say, a unified rejection of what Kīngitanga Chief of Staff, Archdeacon Ngira Simmonds, described as the “unhelpful and divisive rhetoric” of the election campaign.

“Maaori can lead for all”, said Ngira Simmonds, at the beginning of this month, “and we are prepared to do that.” *

This is part of a growing sense, as Ngāpuhi’s Mane Tahere told me, that “we’ve turned a corner”.

The corner is that u word – unity. The increasingly urgent sense of the need for a collective response to the coalition government.

And, without great external fanfare, these relationships have already been building.

The Kīngitanga movement has begun sending some of its most senior figures north for Waitangi Day commemorations – into the heart of Ngāpuhi country. And again, like Ngāpuhi coming to Ngāruawāhia, this reflects a belief that by Māori for Māori, all Māori, is the strongest possible response to a government they fear is intent on division.

This year, for the first time since 2009, Kīngi Tūheitia himself (who has Ngāpuhi whakapapa on his father’s side) will be attending Waitangi.

Symbolic? Yes.

Significant? Yes.

Unity.

Mana motuhake (self-government).

“Look at all these people,” Tame Iti said to me. “They’re here to listen. To learn. The first layer of mana motuhake is yourself.”

All protest is a form of risk.

Risk that it goes awry – and costs support, rather than galvanises it.

Risk that it arms your most cynical critics with the material for derision or contempt.

Risk that no one notices. Or that the turnout is so small that those who have the luxury of being able to not protest can turn away.

Some politicians may tell you that 10,000 people is not very many. I would say otherwise. In 30 years of covering politics, I have never attended a New Zealand party-political rally that attracted anywhere near that many. Or even half that number.

What happened at Tūrangawaewae yesterday was a triumph for all those involved.

In the striking heart of the mid-afternoon, I passed Tukoroirangi Morgan, the chair of the Waikato-Tainui executive board. We were going in opposite directions over the sunburnt road.

Chair of the Waikato-Tainui executive board Tukoroirangi Morgan.

Chair of the Waikato-Tainui executive board Tukoroirangi Morgan. (Source: 1News)

“How’s it going, Tuku?”, I asked him.

“It’s amazing”, he replied. “All these people.” And then he stopped, looked out over the everyone, everywhere, and repeated himself. “Amazing.”

Tūrangawaewae is located just outside Ngāruawāhia, directly across the Waikato River from the shops in that little township. Somewhere, just to its east, the new Waikato Expressway has stolen many of the estimated 17,000 cars a day that once passed through here. For decades, Ngāruawāhia was a pie and petrol stop on the main road between Hamilton and Auckland.

Not so much, any longer.

The challenge of history is to survive it.

And Kīngitanga itself was a kind of survival strategy.

It wasn’t this simple, of course, but a famous saying of the second Māori King, Tāwhiao, broadly speaks to the hopes of the Kīngitanga movement: “Ki te kotahi te kākaho ka whati ki te kāpuia e kore e whati.” The Māori Dictionary translates it prosaically: “If there is but one reed it will break, but if it is bunched together it will not.”

Yesterday, the reeds felt tight and strong.

“Why are you here?” I asked people, over and over.

The answer was almost always a variation of what Christina Te Namu told me. Christina, too, is Ngāpuhi. “I just wanted to support our people”, she said. “Now is the time for us to stand together as one.”

A group of women from Ngati Porou stopped to say kia ora.

It seems almost inadequate to state it like this, but they were there to be there. They had driven from Tairawhiti because being there mattered. Every person I spoke to had come to be part of this declaration of solidarity.

'An attempt to abolish the Treaty'

On Friday morning, something happened that gave this already significant day a vivid, extra weight.

My 1News colleague, Te Aniwa Hurihanganui, obtained details of the coalition Government’s Treaty Principles Bill. In its initial form it is not so much a re-evaluation of the role of the Treaty as an abandonment of it. Professor Margaret Mutu, speaking on 1News on Friday night, called it “an attempt to abolish the Treaty of Waitangi.”

This has arisen out of National’s coalition agreement with ACT.

I wrote about this at the end of last year, and also in the weeks after the election. I looked at the coalition agreements between National and ACT, and National and New Zealand First. And I noted their pointed focus on Māori. Some of it felt mean. What I called a strange, circling sense of a new colonialism.

I wrote about what I saw as ACT and New Zealand First's experiments with a kind of "resentment populism".

Who are we?, I asked. And where are we heading?

We’re heading to National reaching 41 percent in the first political poll of the year, “a massive jump”, as Thomas Coughlan described it in the NZ Herald, earlier this week. And we’re heading here, to Tūrangawaewae, and to thousands of people who travelled from throughout the country to collectively say, “no”.

In other words, we’re heading towards, or have already arrived in the vicinity of what PBS called the “divide and conquer populist agenda”.

And we’re heading to politics that purport to speak out against division, whilst arguably fomenting it.

In an opinion piece by David Seymour, published in the NZ Herald on Friday, the ACT leader begins with the sentence, “If there’s one undercurrent beneath so much of our politics, it’s division”.

Is David Seymour responding to division, or causing it?

The Treaty, he said, in December, “divides rather than unites people, as most treaties are supposed to do.”

But whose endgame is division? Really?

I've written before about the kind of populist politics that drive people to division, then throw up their hands and yell, “LOOK! DIVISION”, having wished for exactly that.

This, as Australian Academic Carol Johson wrote in The Conversation after the “no” vote in Australia’s Voice referendum, speaks to “a conception of equality controversially based on treating everyone the same, regardless of the different circumstances or particular disadvantages they face.”

That's equality as David Seymour consistently claims to define it.

But do as they say, not as they do. There was a time when ACT received some handy support from National. Remember that famous cup of tea? Surely Seymour's idea of equality would have insisted that Act get trounced than receive a leg-up?

The fascinating thing is that populism is typically structured around “the claim to speak for the underdog and the critique of privileged 'elites' and their disregard for the needs of ’ordinary people’".

But it’s hard for National to occupy that space when the party has historically been supported by the “elite”, and when your leader is a former CEO who owns seven properties, and who received total remuneration of $4.2 million in his last full year at Air New Zealand.

So, you can do two things. You can outsource populism to your coalition partners. (And sit there with a face of injured innocence, like someone insisting it was really the dog who farted.) And you can allow coalition partners to redefine the definition of “elite”.

No-one does this more enthusiastically than Winston Peters.

During the months prior to the election, the New Zealand First leader said “elite” more often than Kylie Minogue has said “lucky”.

“Elite Māori”, “elite power-hungry Māori”, “an elite cabal of social and ideological engineers.”

The idea, as I wrote after the election, is to somehow persuade us that Māori are getting something the rest of us are not. And they are: a seven-years-shorter life expectancy, lower household income, persistent inequities in health, the greatest likelihood of leaving school with low or no qualifications, and an over-representation in the criminal justice system to such a great extent that Māori make up 52 percent of the prison population.

Elite as.

So, had this hui erupted into a kind of rage, would that have been a victory for populism? Would the divisions have become entrenched? Would Māori have been blamed for reacting to provocation, rather than the provocation itself being examined?

None of this is new. Which is why Māori recognise it.

In July 1863, the Crown issued a proclamation demanding: “All persons of the native race living in the Manukau district and the Waikato frontier are hereby required immediately to take the oath of allegiance to Her Majesty the Queen”.

And those who wouldn’t?

“Natives refusing to do so are hereby warned forthwith to leave the district aforesaid, and retire to Waikato beyond Mangatawhiri.”

And anyone “not complying with this Order… will be ejected.”

Vincent O’Malley, in his remarkable book The Great War for New Zealand describes what happened next.

“On the same date some 1500 troops marched from Auckland for Drury.”

The troops didn’t stop. There are few more egregious and cynical predations in our history. South they went. Without just cause or provocation. Into Waikato.

Ngāruawāhia, Vincent O’Malley tells us, was “strategically important during the war because of its location at the confluence of the Waikato and Waipā rivers.”

“By 6 December 1863, Ngāruawāhia (‘the late head quarters of Māori sovereignty’ as one reporter dubbed it) had been deserted.”

At four o’clock that afternoon, a British flag was hoisted there.

And why does this story matter, still? 160 years later.

Because the Crown used the requirement for “allegiance”, the demand that Māori be loyal to it, so disingenuously. The language of colonisation purported to be about governance, about the role and rule of a single law, but it was a violation of law and a betrayal of the principles of government.

By the end of this rule of law, roughly 1.2 million acres of Waikato land had been “confiscated”.

And any opposition to it was defined, in law, as “rebellion”. And rebellion was justification for seizing more land.

This is our history. And part of it happened here, where the 10,000 people met yesterday.

It was so hot by late morning that people were swimming in the Waikato River.

I wandered down from the crowds at the hui to talk to the people swimming. They were mostly young, although not all.

I met a ten year old who told me her parents had brought her so she could “find out where I’m from”.

She was from Waitara, in Taranaki, so this wasn’t a literal homecoming.

I wondered how many people had travelled big distances to have a new or reinvigorated sense of what it means to be Māori.

Heading back inside, I saw Professor Margaret Mutu.

There are few who have more rigorously applied their formidable intellect to making sense of the intersection of Māori and colonisation.

Professor Margaret Motu: "You have two parties to a treaty, and one of them can’t unilaterally redefine it."

She is of Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whātua and Scottish descent. She is Professor of Māori Studies at the University of Auckland. And, her university profile tells us, she holds a BSc in mathematics, an MPhil in Māori Studies, a PhD in Māori Studies specialising in linguistics and a DipTchg.

There was nowhere quiet for us to sit. But people kindly made space at the back of a kitchen prep area. And I asked her about the significance of the Treaty, for Māori, for the Crown, and for us all.

“Te Tiriti is where you go," she said. “When things look as if they’re not working for you, you have a protection, and that’s where you go. It will always look after you. It will always protect you.”

“And while it seems clear that this government wants to abolish the Treaty," Margaret Mutu continued, “that can never happen. For one thing, you have two parties to a treaty, and one of them can’t unilaterally redefine it. But also, our tūpuna were very, very wise. In the Treaty they invited Pākehā, the British, to come and live with us. But they had to live with us in peace. In peace and friendship. And that’s what the Treaty is. It’s a treaty of peace and friendship. You can’t redefine that. You can’t rewrite that. It was very wise and it was very clear.”

And here’s where Margaret Mutu helped me understand why the mood at Tūrangawaewae was so – and I wish I could find better words – hopeful, positive, constructive.

Manaaki manuhiri: to support and care for your guests.

“We invited Pākehā to live amongst us,”, she said. “And what a lot of our Pākehā friends don’t understand, I think, is that our tikanga requires us to manaaki manuhiri. And that’s about looking after everybody. Everybody. So even when we have hate thrown at us, we have to assert aroha. That���s what manaaki manuhiri requires, even when people are very badly behaved.” Margaret Mutu laughs at this. “So, people have come here today to find that strength. It’s not about fighting people. It’s to find that strength and unity to be able to rise above the hatred. And now we will just get on and do exactly that.”

After lunch, I was invited to meet the King.

I’ve never been inside Tūrongo before, the royal residence. Or Māhinaarangi, which is both a famous meeting house and a unique kind of museum.

It looks out over the marae. And it gently contains, as if nestled in the palm of a large, open hand, photos and remembrances of those who’ve come before. The people who built Kīngitanga. Tāwhiao is there, his photo looking down from the wall. He died 130 years ago. How he would have marvelled, with great pride, at such a gathering, and perhaps, also, despaired at it still being necessary, in 2024.

Ngira Simmonds took me in. And I found myself, shy for once, able to stand and look out, viewing the unfolding of this new history from a place that is so central to the story of the history of us.

Kīngi Tuheitia was beaming.

“I didn’t sleep last night”, he told me. “But I knew this was the time for us to come together. And we have. We have.”

It occurred to me, as I walked back to stand amongst the thousands Kīngi Tuheitia was looking out to, with such delight, that the hui was the actualisation of Tāwhiao’s hope for the unbreakable strength of reeds tied together.

What was was happening felt transformative in the very fact it was happening. The mana motuhake of 10,000 people.

The vibrations.

Will the government feel them?

Will they survive the divisions of populism? Of politics that echo our repeated capacity to claim we are governing to unite people whilst governing against Māori?

Or maybe, this is how it all begins. In an historically large display of unity.

Rātana follows. Then Waitangi.

Yesterday ended with Kiingi Tuheitia speaking.

“The best protest we can do right now is be Maaori. Be who we are, live our values, speak our reo, care for our mokopuna, our awa, our maunga, just be Maaori. Maaori all day, every day. We are here, we are strong.”

The reeds tightening.

*Macrons haven't been used when quoting Tainui, who choose not to use them.

fantastic article on the national hui in response to aotearoa’s assault on indigenous rights. click through for pictures and video.

#new zealand#aotearoa#nz#nzpol#news#politics#indigenous rights#maaori#maori#land back#david seymour#waitangi#long post

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

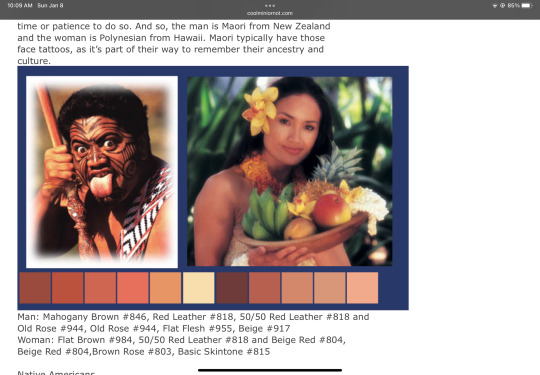

I was looking for what colors to use in coloring Māori skin tones as I am planning on doing a portrait of one of the clones (Fives, Cody, Rex, haven’t decided) and I came up with this fabulous reference page with exactly what I was looking for:

So, the page this came from was deleted. However, I have a pdf copy of it on my iCloud drive so any artist wanting to create a color palette for Star Wars Clones (who are based off Temuera Morrison who is Māori, of Te Arawa (Ngāti Whakaue) and Tainui (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Rarua) whakapapa, and also has Scottish and Irish ancestry) or any other ethnic background can hit me up and I’ll post what I have ☺️

#reference images#skin tones#artist references#references#no more guessing what colors to pick#art advice

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

House post figure (Amo). (ca. 1800). Maori people, Te Arawa

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was looking to update an FC and replace Jason Momoa because I've heard some promblematic stuff 'bout him and 'cause of age requirements. Do you have any alts or suggestions for a male actor in his early 30s with beach-y vibe or smt like that, tall and more or less muscular and beefy? Preferably Hawaiian, although I'd apreciate if you include other actors of Pacific Islander or Indigenous ancestry.

Marcus LaVoi (1968) Ojibwe.

Joe Naufahu (1978) Tongan, Samoan, White - has spoken up for Palestine!

Mark Kanemura (1983) Samoan, Japanese, White - is gay.

Uli Latukefu (1983) Tongan.

Roman Reigns (1985) Samoan / White.

Martin Sensmeier (1985) Tlingit, Koyukon, Eyak, White.

Lasarus Ratuere (1985) Fijian, Torres Strait Islander, Unspecified Aboriginal Australian.

Keahu Kahuanui (1986) Kānaka Maoli, Japanese, White.

Kalani Queypo (1986) Blackfoot, Kānaka Maoli, White.

Mark Coles Smith (1987) Nyigina.

Alex Tarrant (1990) Niuean, Samoan, Ngāti Pāoa.

Daniel Vidot (1990) Samoan and Irish.

Marlon Teixeira (1991) Brazilian [Portuguese, Unspecified Indigenous, Japanese].

Clarence Ryan (1992) Unspecified Aboriginal Australian.

Beulah Koale (1992) Samoan.

Hunter Page-Lochard (1993) Nunukul, Yugambeh, Haitian, White.

Jordi Webber (1994) Ngāti Toa, Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Raukawa, White / Te Arawa, Ngāti Maniapoto, White.

I gave older suggestions for those looking too!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Names: Jaws, Komoh, Daddy Shark doodoodoo Pronouns: He/Him Caste: Full Moon Age:(Looks 30) 90+ Totem: Siaka Faction:Silver pact (Unaligned) Nationality: The West (Cowries, Te Arawa) Allies: Leaf, Razor Fang (Mentor), Rowdy boys, Te Arawa Favored Skills: Martial arts, Craft wood, Mentoring

Is a surprisingly chill murder full moon.

Name: Epa Pronouns: She/Her Caste: Godblooded (Lunar dad, can turn into Siaka underwater) Nationality: The West Age: 15 Allies: Her giant shark sisters/Supportive Lunar dad

Enjoys fighting big things for the Shark god, lifting heavy rocks to then be better at fighting, and sushi. Has two art modes, awesome badass or stupid gremlin:

The context is she found an old shipwreck with Siakal (Shark goddess) as a figurehead and thought it was cool so she went to show it off to her shark sisters.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Men in Kilts 2 - a preview of the coming season.

I can't wait to see the haka... in New Zealand, if SH and GMcT can't handle it, they're in the wrong sport 🏉

I wonder if MiK2 continues its immersive adventure travel experience, delving into the history of Scottish influence in New Zealand 🤔

Or if SH and GMcT travelled to the island country, for the extreme sports trip of a lifetime! Maybe New Zealand's adventure sports are too extreme to miss out 💁

@pukehina I agree with you, They’re learning part of the “Ka Mate” haka and SH emphasises a Pūkana. Imitating the pregame ritual of New Zealand’s national rugby union team, the All Blacks. I would like to see these tourists learn the haka in Rotorua, the tourist hotspot in New Zealand’s central North Island, Te Arawa – the local tribe and perhaps the best haka performers in the country – share their art and coach their visitors in certain haka.

It seems in this photo their coaches are not Māori. Could many will feeling 'extremely awkward' about how to respond to their Haka?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

opinion article by John Campbell about the National Hui for Unity.

(full text below the "read more" button in case of paywall)

OPINION: The national hui at Tūrangawaewae Marae saw 10,000 people united in the face of actions by the coalition government, including its proposed Treaty Principles Bill. John Campbell was there.

History happens on single days.

Yesterday, at Tūrangawaewae, will be one of them.

“Why are you here?”, I asked Tame Iti.

“Vibrations”, he replied.

The rest of us will feel them over the days and months and years ahead.

Initial estimates of how many people would come had begun at 3000. Then 4000 registered, so estimates grew to 5000. Then 7000. By lunchtime, organisers were saying 10,000 had arrived. There wasn't room inside for them all. A large marquee across the road was full, all day. Every seat, everywhere, was taken. There was hardly standing room.

This special place, which has held tangi for royalty, which is where the Tainui treaty settlement was signed, which was visited by Nelson Mandela, and Queen Elizabeth II, and many of our greatest rangatira, has seldom seen so many people.

But no one objected. To standing. To the steaming heat. To the fact that sometimes people were too far away from the speakers, or the screens relaying them, to hear.

New Zealand First’s deputy leader, Shane Jones, told RNZ the hui could turn into a “monumental moan session”.

But it didn’t. Somehow, the word I keep coming back to is joyful.

The National Hui for Unity it was called. And it felt like exactly that.

Iwi after iwi: the big 10

On the way to Ngāruawāhia early yesterday morning, I pulled into a truck-stop near Bombay, at the southernmost end of the Auckland motorway system, to meet the Ngāpuhi convoy travelling down from the far north.

Some had begun their journey way up, in Kaikohe, at 3am. They spilled out into the half light of an overcast morning and inhaled the beginning of what would be an extraordinary day.

It’s easy for the significance of this delegation to be lost amid all the other arrivals. The people who’d come from even further away. Iwi after iwi. Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou, Tainui, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu, Te Arawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Maniapoto – the big ten, all there, in declaratory numbers.

Ngāi Tahu representatives had taken a huge journey by road, then Cook Strait ferry, then road.

A friend’s father flew up from Invercargill.

But the size and standing of Ngāpuhi’s delegation provides some insight into how very significant this hui was.

Ngāpuhi aren’t a Kīngitanga iwi. They don’t see Kīngi Tūheitia as their king. And they contain Waitangi within their broad, northern boundaries – home, of course, to the Waitangi commemorations, our most famous form of national hui.

And yet they came, hundreds of Ngāpuhi. Some wearing korowai made especially for the occasion. Some the direct descendants of Treaty signatories. A waiata, composed for the hui, rehearsed beyond newness into a heartfelt and singular voice.

“Why are you going?” I asked Mane Tahere, the chair of Te Runanga-Ā-Iwi-Ō-Ngāpuhi. “It feels significant that Ngāpuhi are attending in such numbers.”

“Because”, he answered, “the challenges we face do not discriminate amongst iwi. We held three hui to discuss whether we should come, and who would come, and what our message would be. The final hui was only last Saturday. I wouldn’t have put our rūnanga resources into something we didn’t collectively support. This was hapū rangatiratanga. Hapū after hapū spoke and said we should go.”

Why?

“Because the question we have to ask as Māori is how we activate ourselves, re-activate ourselves, for 2024? How do we say to the coalition government, ‘hang on, what do you mean, and what are you doing?’ And the best way to do that is to do it together. Now is the time for Māori unity.”

A powerful rejection

The National Hui for Unity was only called by Kīngi Tuheitia Pootatau Te Wherowhero VII (Kīngi Tuheitia) at the beginning of December. That so very many people would arrive here, only six weeks later, in the holiday-season slowness of the third week of January, speaks not only to how resoundingly those present reject the coalition government’s Treaty Principles Bill, but also to a strength of unity already existing.

That is to say, a unified rejection of what Kīngitanga Chief of Staff, Archdeacon Ngira Simmonds, described as the “unhelpful and divisive rhetoric” of the election campaign.

“Maaori can lead for all”, said Ngira Simmonds, at the beginning of this month, “and we are prepared to do that.” *

This is part of a growing sense, as Ngāpuhi’s Mane Tahere told me, that “we’ve turned a corner”.

The corner is that u word – unity. The increasingly urgent sense of the need for a collective response to the coalition government.

And, without great external fanfare, these relationships have already been building.

The Kīngitanga movement has begun sending some of its most senior figures north for Waitangi Day commemorations – into the heart of Ngāpuhi country. And again, like Ngāpuhi coming to Ngāruawāhia, this reflects a belief that by Māori for Māori, all Māori, is the strongest possible response to a government they fear is intent on division.

This year, for the first time since 2009, Kīngi Tūheitia himself (who has Ngāpuhi whakapapa on his father’s side) will be attending Waitangi.

Symbolic? Yes.

Significant? Yes.

Unity.

Mana motuhake (self-government).

“Look at all these people,” Tame Iti said to me. “They’re here to listen. To learn. The first layer of mana motuhake is yourself.”

All protest is a form of risk.

Risk that it goes awry – and costs support, rather than galvanises it.

Risk that it arms your most cynical critics with the material for derision or contempt.

Risk that no one notices. Or that the turnout is so small that those who have the luxury of being able to not protest can turn away.

Some politicians may tell you that 10,000 people is not very many. I would say otherwise. In 30 years of covering politics, I have never attended a New Zealand party-political rally that attracted anywhere near that many. Or even half that number.

What happened at Tūrangawaewae yesterday was a triumph for all those involved.

In the striking heart of the mid-afternoon, I passed Tukoroirangi Morgan, the chair of the Waikato-Tainui executive board. We were going in opposite directions over the sunburnt road.

“How’s it going, Tuku?”, I asked him.

“I’s amazing”, he replied. “All these people.” And then he stopped, looked out over the everyone, everywhere, and repeated himself. “Amazing.”

The challenge of history

Tūrangawaewae is located just outside Ngāruawāhia, directly across the Waikato River from the shops in that little township. Somewhere, just to its east, the new Waikato Expressway has stolen many of the estimated 17,000 cars a day that once passed through here. For decades, Ngāruawāhia was a pie and petrol stop on the main road between Hamilton and Auckland.

Not so much, any longer.

The challenge of history is to survive it.

And Kīngitanga itself was a kind of survival strategy.

It wasn’t this simple, of course, but a famous saying of the second Māori King, Tāwhiao, broadly speaks to the hopes of the Kīngitanga movement: “Ki te kotahi te kākaho ka whati ki te kāpuia e kore e whati.” The Māori Dictionary translates it prosaically: “If there is but one reed it will break, but if it is bunched together it will not.”

Yesterday, the reeds felt tight and strong.

“Why are you here?” I asked people, over and over.

The answer was almost always a variation of what Christina Te Namu told me. Christina, too, is Ngāpuhi. “I just wanted to support our people”, she said. “Now is the time for us to stand together as one.”

A group of women from Ngati Porou stopped to say kia ora.

It seems almost inadequate to state it like this, but they were there to be there. They had driven from Tairawhiti because being there mattered. Every person I spoke to had come to be part of this declaration of solidarity.

'An attempt to abolish the Treaty'

On Friday morning, something happened that gave this already significant day a vivid, extra weight.

My 1News colleague, Te Aniwa Hurihanganui, obtained details of the coalition Government’s Treaty Principles Bill. In its initial form it is not so much a re-evaluation of the role of the Treaty as an abandonment of it. Professor Margaret Mutu, speaking on 1News on Friday night, called it “an attempt to abolish the Treaty of Waitangi.”

This has arisen out of National’s coalition agreement with ACT.

I wrote about this at the end of last year, and also in the weeks after the election. I looked at the coalition agreements between National and ACT, and National and New Zealand First. And I noted their pointed focus on Māori. Some of it felt mean. What I called a strange, circling sense of a new colonialism.

I wrote about what I saw as ACT and New Zealand First's experiments with a kind of "resentment populism".

Who are we?, I asked. And where are we heading?

We’re heading to National reaching 41 percent in the first political poll of the year, “a massive jump”, as Thomas Coughlan described it in the NZ Herald, earlier this week. And we’re heading here, to Tūrangawaewae, and to thousands of people who travelled from throughout the country to collectively say, “no”.

In other words, we’re heading towards, or have already arrived in the vicinity of what PBS called the “divide and conquer populist agenda”.

And we’re heading to politics that purport to speak out against division, whilst arguably fomenting it.

In an opinion piece by David Seymour, published in the NZ Herald on Friday, the ACT leader begins with the sentence, “If there’s one undercurrent beneath so much of our politics, it’s division”.

Is David Seymour responding to division, or causing it?

The Treaty, he said, in December, “divides rather than unites people, as most treaties are supposed to do.”

But whose endgame is division? Really?

I've written before about the kind of populist politics that drive people to division, then throw up their hands and yell, “LOOK! DIVISION”, having wished for exactly that.

This, as Australian Academic Carol Johson wrote in The Conversation after the “no” vote in Australia’s Voice referendum, speaks to “a conception of equality controversially based on treating everyone the same, regardless of the different circumstances or particular disadvantages they face.”

That's equality as David Seymour consistently claims to define it.

But do as they say, not as they do. There was a time when ACT received some handy support from National. Remember that famous cup of tea? Surely Seymour's idea of equality would have insisted that Act get trounced than receive a leg-up?

The fascinating thing is that populism is typically structured around “the claim to speak for the underdog and the critique of privileged 'elites' and their disregard for the needs of ’ordinary people’".

But it’s hard for National to occupy that space when the party has historically been supported by the “elite”, and when your leader is a former CEO who owns seven properties, and who received total remuneration of $4.2 million in his last full year at Air New Zealand.

So, you can do two things. You can outsource populism to your coalition partners. (And sit there with a face of injured innocence, like someone insisting it was really the dog who farted.) And you can allow coalition partners to redefine the definition of “elite”.

No-one does this more enthusiastically than Winston Peters.

During the months prior to the election, the New Zealand First leader said “elite” more often than Kylie Minogue has said “lucky”.

“Elite Māori”, “elite power-hungry Māori”, “an elite cabal of social and ideological engineers.”

The idea, as I wrote after the election, is to somehow persuade us that Māori are getting something the rest of us are not. And they are: a seven-years-shorter life expectancy, lower household income, persistent inequities in health, the greatest likelihood of leaving school with low or no qualifications, and an over-representation in the criminal justice system to such a great extent that Māori make up 52 percent of the prison population.

Elite as.

A shameful history

So, had this hui erupted into a kind of rage, would that have been a victory for populism? Would the divisions have become entrenched? Would Māori have been blamed for reacting to provocation, rather than the provocation itself being examined?

None of this is new. Which is why Māori recognise it.

In July 1863, the Crown issued a proclamation demanding: “All persons of the native race living in the Manukau district and the Waikato frontier are hereby required immediately to take the oath of allegiance to Her Majesty the Queen”.

And those who wouldn’t?

“Natives refusing to do so are hereby warned forthwith to leave the district aforesaid, and retire to Waikato beyond Mangatawhiri.”

And anyone “not complying with this Order… will be ejected.”

Vincent O’Malley, in his remarkable book The Great War for New Zealand describes what happened next.

“On the same date some 1500 troops marched from Auckland for Drury.”

The troops didn’t stop. There are few more egregious and cynical predations in our history. South they went. Without just cause or provocation. Into Waikato.

Ngāruawāhia, Vincent O’Malley tells us, was “strategically important during the war because of its location at the confluence of the Waikato and Waipā rivers.”

“By 6 December 1863, Ngāruawāhia (‘the late head quarters of Māori sovereignty’ as one reporter dubbed it) had been deserted.”

At four o’clock that afternoon, a British flag was hoisted there.

And why does this story matter, still? 160 years later.

Because the Crown used the requirement for “allegiance”, the demand that Māori be loyal to it, so disingenuously. The language of colonisation purported to be about governance, about the role and rule of a single law, but it was a violation of law and a betrayal of the principles of government.

By the end of this rule of law, roughly 1.2 million acres of Waikato land had been “confiscated”.

And any opposition to it was defined, in law, as “rebellion”. And rebellion was justification for seizing more land.

This is our history. And part of it happened here, where the 10,000 people met yesterday.

Rising above the hatred

It was so hot by late morning that people were swimming in the Waikato River.

I wandered down from the crowds at the hui to talk to the people swimming. They were mostly young, although not all.

I met a ten year old who told me her parents had brought her so she could “find out where I’m from”.

She was from Waitara, in Taranaki, so this wasn’t a literal homecoming.

I wondered how many people had travelled big distances to have a new or reinvigorated sense of what it means to be Māori.

Heading back inside, I saw Professor Margaret Mutu.

There are few who have more rigorously applied their formidable intellect to making sense of the intersection of Māori and colonisation.

She is of Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whātua and Scottish descent. She is Professor of Māori Studies at the University of Auckland. And, her university profile tells us, she holds a BSc in mathematics, an MPhil in Māori Studies, a PhD in Māori Studies specialising in linguistics and a DipTchg.

There was nowhere quiet for us to sit. But people kindly made space at the back of a kitchen prep area. And I asked her about the significance of the Treaty, for Māori, for the Crown, and for us all.

“Te Tiriti is where you go," she said. “When things look as if they’re not working for you, you have a protection, and that’s where you go. It will always look after you. It will always protect you.”

“And while it seems clear that this government wants to abolish the Treaty," Margaret Mutu continued, “that can never happen. For one thing, you have two parties to a treaty, and one of them can’t unilaterally redefine it. But also, our tūpuna were very, very wise. In the Treaty they invited Pākehā, the British, to come and live with us. But they had to live with us in peace. In peace and friendship. And that’s what the Treaty is. It’s a treaty of peace and friendship. You can’t redefine that. You can’t rewrite that. It was very wise and it was very clear.”

And here’s where Margaret Mutu helped me understand why the mood at Tūrangawaewae was so – and I wish I could find better words – hopeful, positive, constructive.

Manaaki manuhiri: to support and care for your guests.

“We invited Pākehā to live amongst us,”, she said. “And what a lot of our Pākehā friends don’t understand, I think, is that our tikanga requires us to manaaki manuhiri. And that’s about looking after everybody. Everybody. So even when we have hate thrown at us, we have to assert aroha. That’s what manaaki manuhiri requires, even when people are very badly behaved.” Margaret Mutu laughs at this. “So, people have come here today to find that strength. It’s not about fighting people. It’s to find that strength and unity to be able to rise above the hatred. And now we will just get on and do exactly that.”

Meeting the King

After lunch, I was invited to meet the King.

I’ve never been inside Tūrongo before, the royal residence. Or Māhinaarangi, which is both a famous meeting house and a unique kind of museum.

It looks out over the marae. And it gently contains, as if nestled in the palm of a large, open hand, photos and remembrances of those who’ve come before. The people who built Kīngitanga. Tāwhiao is there, his photo looking down from the wall. He died 130 years ago. How he would have marvelled, with great pride, at such a gathering, and perhaps, also, despaired at it still being necessary, in 2024.

Ngira Simmonds took me in. And I found myself, shy for once, able to stand and look out, viewing the unfolding of this new history from a place that is so central to the story of the history of us.

Kīngi Tuheitia was beaming.

“I didn’t sleep last night”, he told me. “But I knew this was the time for us to come together. And we have. We have.”

It occurred to me, as I walked back to stand amongst the thousands Kīngi Tuheitia was looking out to, with such delight, that the hui was the actualisation of Tāwhiao’s hope for the unbreakable strength of reeds tied together.

What was was happening felt transformative in the very fact it was happening. The mana motuhake of 10,000 people.

The vibrations.

Will the government feel them?

Will they survive the divisions of populism? Of politics that echo our repeated capacity to claim we are governing to unite people whilst governing against Māori?

Or maybe, this is how it all begins. In an historically large display of unity.

Rātana follows. Then Waitangi.

Yesterday ended with Kiingi Tuheitia speaking.

“The best protest we can do right now is be Maaori. Be who we are, live our values, speak our reo, care for our mokopuna, our awa, our maunga, just be Maaori. Maaori all day, every day. We are here, we are strong.”

The reeds tightening.

*Macrons haven't been used when quoting Tainui, who choose not to use them.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This was carved by Matahi Whakataka-Brightwell (Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Ngāti Raukawa, Te Arawa, Rongowhakaata), and the carving is of Ngatoroirangi, his ancestor. It was made in the 1970s.

114K notes

·

View notes

Text

TE PUEA HĒRANGI // PRINCESS OF THE MĀORI

“She was a Māori leader from New Zealand's Waikato region. Te Puea's support base was mainly with the lower Waikato tribes initially. She was a minor figure for up-river iwi such as Maniapoto. Because of Waikato's anti-government stance on conscription during WW1 and Te Puea's personal involvement in hiding conscripts, she was not a popular figure with government or local Pākehā after WW1. She provided a refuge at her farm for those who refused to be conscripted into the New Zealand Army. After WW1, farmers were reluctant to offer Kingites work and during the Royal visit of the Prince of Wales the Kingites' desire to host the prince was snubbed in favour of an Arawa visit which was open to all Māori to attend. She was soon acknowledged as one of the leaders of the Kīngitanga Movement and worked to make it part of the central focus of the Māori people. Following the influenza epidemic of 1918, she took under her wing some 100 orphans, who were the founding members of the community of Tūrangawaewae at Ngāruawāhia. Te Puea was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire, for social welfare services, in the 1937 Coronation Honours.”

0 notes

Text

Studio One: Arca Arcade 'Round One' - Preston McNeil

13 October 2024

Visited studio one and checked out a few exhibitions to help me with installation ideas.

Preston McNeil's Arca Arcade 'Round One' installation was pretty fascinating. It features designs by street artists like Otis Frizzell, Gina Kiel, Otis Chamberlain and Flox

It used a QR code that enabled a visual display on your phone trigged by one of the images on the arcade machine.

This is a video of what I saw - but with a different QR code than the example above.

RNZ had an article about it:

0 notes

Note

Hi, hello! Any ideas for an indigenous actor to play a tribal chief? I'd like an actor aged 37 or over

Hello hello! I'll give you some options <3

Alex Meraz (31-39) [Purépecha descent]

Chaske Spencer (40-48) [His heritage includes Lakota, Nez Perce, Cherokee, Muscogee, French, and Dutch. He is Lakota Sioux, enrolled with the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of Montana through his mother]

Jason Momoa (36-44) [Native Hawaiian and Samoan descent]

Martin Sensmeier (31-38) [Tlingit, Koyukon-Athabascan descent]

Manu Bennett (46-54) [Māori (specifically Te Arawa and Ngāti Kahungunu) descent]

(cib)

1 note

·

View note

Text

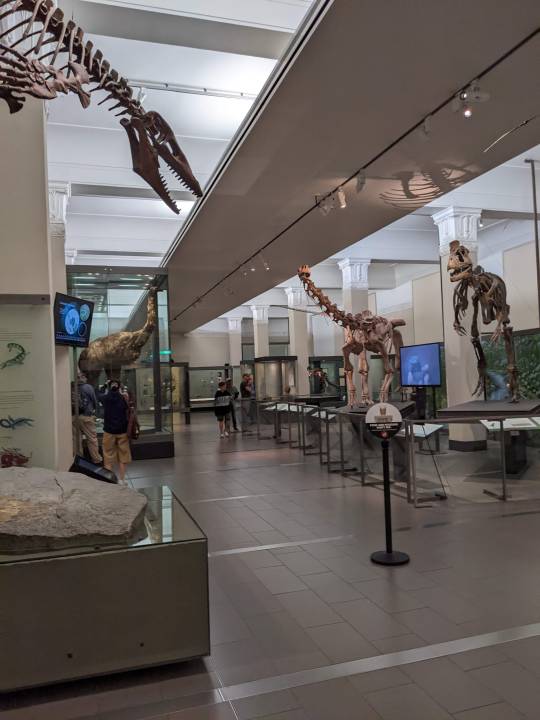

肥宅哈比人魔戒之旅-2023紐西蘭北島行(12)奧克蘭戰爭紀念博物館

續前篇,吃過午飯後,我們走到奧克蘭戰爭紀念博物館,博物館本身雖然面積不是很大,但是很漂亮的新古典主義建築.周圍是奧克蘭領地公園(Auckland Domain),面積非常大,館藏非常豐富,大略可以分為幾個主題:

紐西蘭歷史(奧克蘭城市史,太平洋廳毛利人的文化與工藝)

自然史(古代自然生物,火山地科教育)

軍事史(紐西蘭本地戰爭,一戰二戰歷史文物,戰爭犧牲將士紀念)

有恐龍的博物館才是好的自然史博物館

裡面最著名的應該就是這棟以一個重要的先祖為名的「Hotunui」,是一棟1878年在紐西蘭泰晤士建成的聚會所,是舉行部落重要儀式(喪禮���)及聚會場合(議會開會等)的神聖場域���

另一棟Te Puāwai o Te Arawa是儲藏屋,專門用來放部落最貴重的財產,例如珠寶首飾,武器謀生工具等,所以門非常小,

這是戰爭用的獨木舟,跟一般航行用的不太一樣,有很多的雕刻,船艏刻有戰爭之神

這是介紹紐西蘭傳統食用的植物,還有烹飪方法,也就是我們第一天吃的「 Hāngi」,將 紅薯Kumara和肉類用樹葉包裹並放在籃子裡,然後放在深洞內的加熱石頭上花時間悶熟.

自然史博物館一定要的絕種動物標本與化石

恐鳥模型,最初的恐鳥大腿骨化石就是在紐西蘭發現,後來被送到倫敦.恐鳥的毛利語:moa

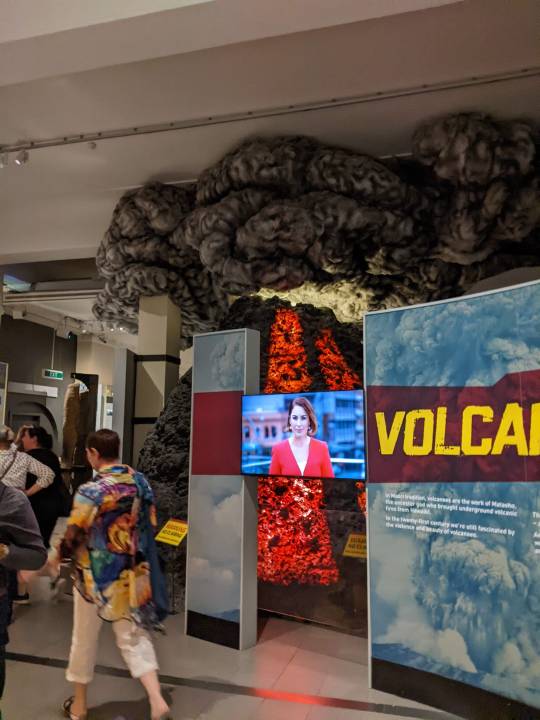

因為紐西蘭火山活動頻繁,到處都是火山,所以相關的安全教育也非常重要

火山爆發模擬體驗小屋

youtube

戰爭史的部分還蠻不錯的,因為在台灣很少有比較完整的關於戰爭史的博物館,有的話規模也非常小或是特展性質,明明就算以中華民國的角度出發,一戰雖然對中華民國來說直接參與的部分不多,但對中國的影響也很大,二戰就更不用說,八年抗戰,甚至後來的國共內戰,或是從台灣角度出發的原住民抗日戰爭和台籍日本兵參與的太平洋戰爭後期等等,可能因為題材敏感和戰時混亂文物保存不易吧,所以這是我第一次參觀有戰爭史的博物館.

這裡有兩架飛機算是鎮館之寶

日本零式艦上戰鬥機

英國的Mark XVI (TE 456)噴火戰鬥機

接著走到的是戰爭中陣亡將士的名單牆,氛圍蠻莊嚴沉重的區域.

外面有一個戰爭紀念碑

逛到差不多快關門,腿也快斷的時候,就去和在奧克蘭工作剛下班的推友小夥伴進行跨越太平洋的推聚,一起去吃了好吃的韓式料理.

總得來說,奧克蘭戰爭紀念博物館是蠻值得花一整天去參觀的景點,但是這個地方也讓人感到一種美麗與哀愁,讓人思考人類明明有很美的光明的一面,有創造了這麼多燦爛文化和藝術的美妙心靈,以及為了生存與大自然拼搏的勇敢;但同時也展現了黑暗的另一面,這麼多的戰爭,殖民與死亡,以及經過慘烈的(New Zealand Wars)土地戰爭而衰弱喪失大半土地與文化體系,被搬到博物館典藏避免記憶消失的原住民文化.種種思緒在走出博物館時只能化做一聲嘆息.

「Let These Panels Never Be Filled.」

待續

0 notes

Text

Raptor Apprentice - Wingspan Birds of Prey Trust - Rotorua

With the exciting growth and development at the Wingspan National Bird of Prey Centre, we’re thrilled to offer an apprenticeship opportunity for a passionate and motivated individual to join our dedicated conservation team. Wingspan is a registered charitable trust and NGO, located on the ancestral lands of Ngāti Whakaue Tribal Lands (Te Arawa) in Rotorua. Our raptor conservation program has been…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

ALIEN WEAPONRY's New "Īhenga" Music Video Celebrates Legendary Te Arawa Explorer

[Photo Credit: Piotr Kwasnik] In 2021, New Zealand’s global metal frontrunners ALIEN WEAPONRY released their sophomore full-length album, Tangaroa – a record immersed in important historical accounts and cultural heritage of the Māori people. Their role in uniquely spreading vital tales of their culture to an international audience even resulted in recent accolades – last year and for the second…

View On WordPress

0 notes