#Systema Naturae

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

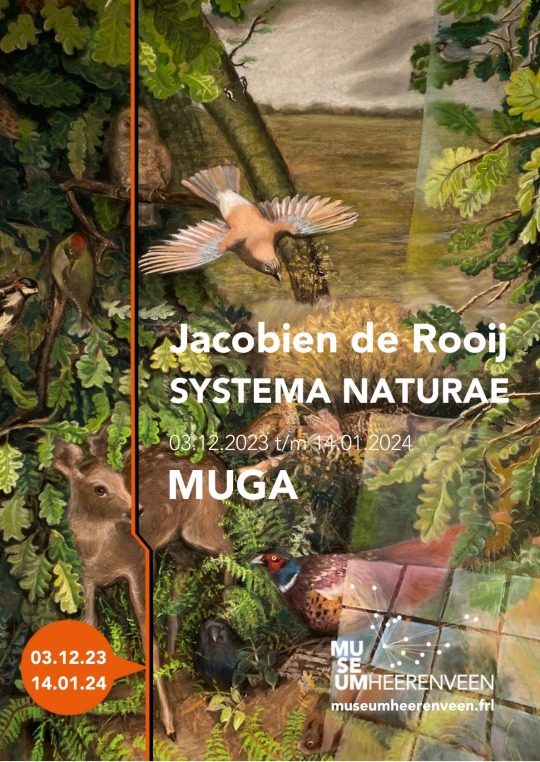

DENKBEELDIGE DROOMWERELDEN BEVOLKEN DE GALERIE VAN HET MUSEUM

Loop ik door het landschap slaat mijn harde schijf allerlei indrukken op. In mijn brein worden gedachten gevormd die waarnemingen zijn van de werkelijkheid. Later kan ik deze ervaringen oproepen en mijmeren over wat ik zag. In die filosofie wordt wat ik heb gezien positief misvormd door het gevoel dat die omgeving bij me opriep. Ik zie in gedachten dus niet de realiteit, maar dat wat mijn beleving ervan tot werkelijkheid maakt. De gewaarwording is een samenspel van zien, horen en ruiken. Deze zintuiglijke observatie verwordt tot een abstract gevoel. In gedachten beleef ik de sensatie van mijn landschap opnieuw. Mijn landschap, want ik eigen mij dat wat ik zag toe. Zo beleeft ieder individu, elk mens, de omgeving op een eigen manier. Maakt er een eigen sfeer van. Een persoonlijk decor waarin de beleving een hoofdrol speelt.

Dat is wat Jacobien de Rooij doet. Al de indrukken die zij opdoet in de natuur, het landschap, worden tot haar omgeving, haar wereld. Naar de waarneming tekent zij het landschap uit. Maar het is haar waarneming, haar persoonlijke gewaarwording. In krijt verbeeldt zij kleurig wat ze tijdens tochten in gedachten opsloeg en meenam naar huis. In het atelier worden die flarden realiteit tot een nieuwe werkelijkheid. Als het ware als collage opgebouwd en nergens exact volgens de waarneming uitgewerkt. Het zijn deeltjes van die werkelijkheid tot een nieuwe realiteit gevormd.

Het lijkt naar de waarneming gemaakt te zijn en in feite is dat ook zo. Maar niet de waarneming zoals ik deze opsla en meeneem wanneer ik door het landschap ga. Want ieder mens neemt verschillende dingen waar, heeft oog voor andere details in het geheel. Van meerdere tijden en plaatsen kunnen die observaties tot een enkele compositie worden. Ieder werk van De Rooij is een reconstructie van indrukken en invalshoeken, gevoelens en stemmingen. Daar de emotie een grote rol speelt in het geziene beeld. Zoals de smaak een gerecht sensationeel kan maken, terwijl dat opgemaakte eten ook al oogstrelend is.

Jacobien de Rooij maakt van de natuur een persoonlijk systeem. Door alle waarnemingen bij elkaar te harken kan ze een samenspel van verbeeldingen maken. Een samenstelling van de zichtbare werkelijkheid, door deze te combineren met verborgen details die voor haar in gedachten meespelen. Het is zo dat het kunstenaarsoog, door jaren training van anders kijken en geconcentreerd zien, meer waarneemt dan dat het ‘gewone’ oog dat doet en kan. De kunstenaar kijkt om de waarneming heen en ontdekt een nieuwe wereld. Dat gezicht achter de werkelijkheid geeft een fris inzicht op de zichtbare realiteit.

De Rooij laat meer zien dan dat er in feite te zien is. En eigenlijk ook weer niet, want alles dat zij op papier zet bestaat en is, komt voor en speelt zich af. Alleen niet in de situatie zoals zij deze op papier zet. Jacobien misleidt met haar werk mijn blik. De tekeningen als schilderijen mystificeren mijn zien. Het is een mysterie hoe de verbeelding de aandacht zo kan concentreren op iets wat werkelijkheid lijkt maar dat niet is. Een imaginaire wereld herinnerend aan wat ik ooit in werkelijkheid eens gezien heb. In haar idee krijgt die wereld een dimensie meer. Een maat meer dan dat wat ik om mij heen zie. Denkend aan de werkelijkheid, een gedachte toevoegend. Een magisch denkbeeld.

Bij de tentoonstelling ‘Systema Naturae’ van haar werk in Museum Galerie Heerenveen tref ik de uitgave “Kijk dan!” aan. Een boek waarin De Rooij een overzicht van haar tekeningen laat zien tot de datum van verschijnen in het jaar 2020. Gelijktijdig was er in de maand september van dat jaar een tentoonstelling van dat werk aan huis en in haar atelier. Over de werken in die uitgave liet ik al eens eerder mijn gedachten gaan. “Telkens stelt ze zichzelf op de proef en probeert haar eigen kunnen voortdurend te overtroeven. Ieder volgend werk moet meer sprekend zijn. Elk vorig werk is dat zeker.” Nu, enkele jaren verder, heeft De Rooij haar plafond niet bereikt. Nog voortdurend bevecht zij gedetailleerd elk formaat. In handzame afmeting werkt zij even monumentaal als op menshoge composities. Eens schijn ik aan de oever van een kabbelende rivier te zitten, dan lijk ik al snorkelend een blik onder water te werpen, op een ander moment spiegelt mijn beeld zich in een raam waardoor ik de omgeving zie. Ook toont ze me de microscopische wereld, de aarde waaruit leven ontstaat. Kiezels die hun vorm krijgen in de tijd en kleuren naar het moment van beleven. Flora dirigeert het orkest van tinten, transparantie speelt de eerste viool.

Daarnaast schijnt het dat Jacobien de Rooij de traditie van de schoolplaat voortzet. Cornelis Jetses en Marinus Koekkoek onder andere propten hun tekeningen vol met details. Zo dat de meester zijn breedvoerige verhaal met behulp van de aanwijsstok kon illustreren. De wereld werd aanschouwelijk gemaakt, want één tekening zegt meer dan honderd woorden. Vaak werden deze platen bevolkt door bijvoorbeeld dieren en insecten die je normaal niet bij elkaar in de buurt ziet. Ze passen in een bepaalde habitat echter wel samen. Dat is wat De Rooij ook wel doet in haar werk. In haar jungle zitten dieren gebroederlijk naast elkaar, die zich gewoonweg tot op de dood bevechten. In dat opzicht kunnen het Bijbelse illustraties zijn, waarin de wolf bij het lam verblijft, de luiaard bij een geitenbok neerligt, een kalf, een jonge leeuw en gemest vee bij elkaar zijn, de koe en berin samen weiden. Een utopie, een ideale wereld. Kijk dan!

Systema Naturae, krijttekeningen van Jacobien de Rooij bij de MUGA van Museum Heerenveen, Minckelersstraat 11. Van 3 december 2023 tot en met 14 januari 2024.

0 notes

Text

— Linnaeus about pufferfish and seahorses, 1767 (he moved them in with amphibians and reptiles instead)

IT IS NOT A FUCKING FISH IT IS NOT A FUCKINV FISH STOP SAYING YOU THINK IT MIGHT BE A FISH BUT THERE ARENT ENOUGH TEETH FOR IT TO BE A FISH YOU KNOW IT ISNT A FISH AND I KNOW YOU KNOW IT ISNT A FISH IT IS VERY VERY VERY CLEARLY NOT A FISH IT DOESNT EVEN LOOL REMOTELY CLOSE TO THE SHAOE OF A FISH WIHOUT GIVING A SINGLE SHIT ABOUT HOW MANY TEETH IT HAS STOP SAYING YOU THINK IY MIGHT BE A FISH IT IS NOT A FUCKING. FISH

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carl Linnaeus invented the binomial nomenclature system of modern taxonomy with the publication of Systema Naturae in 1735. This has made a lot of biologists very angry, and it is widely regarded as a bad move. As such, to eternally dunk on Linneaus and the curse he brought on us, we put an "L." after the name of every species he described, so he can take it.

#cosas mias#botany#biology#only botanists do that though they want to be special and have their names all over the place

519 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iris × germanica (bearded iris)

Carl Linnaeus named the iris genus in 1735 in the first edition of Systema Naturae. Iris was the Greek goddess of the rainbow, famous for her "raiment of many colors." Indeed, irises do come in a variety of colors but these bearded irises look nothing like those known in the time of Linnaeus. The modern bearded iris flower is roughly twice as big as those grown a mere hundred years ago. Ruffles (see photo 3) were developed in the 1960's to help keep the enormous petals from collapsing.

#flowers#photographers on tumblr#iris#gardening#Bullfinch's Mythology#fleurs#flores#fiori#blumen#bloemen#Vancouver

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello tumblr I’m a frog scientist and I heard you like frogs here so I’m here to share frog content if that’s okay

my first contribution is to inform you all that Carl Linnaeus hated frogs. Like, really hated them:

"These foul and loathsome animals are abhorrent because of their cold body, pale color, cartilaginous skeleton, filthy skin, fierce aspect, calculating eye, offensive smell, harsh voice, squalid habitation, and terrible venom; and so their Creator has not exerted his powers to make more of them." - Carl Linnaeus, Systema Naturae 1758 (Translated from Latin)

idk what went down between Linnaeus and a frog but dude was traumatised

also here is a photo of one of my science frogs, his name is Granny

#i love frogs#frog science#frog#frogs#carl linnaeus#herptile#herpetology#science#history#green tree frogs#dumpy frog#whites tree frog

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

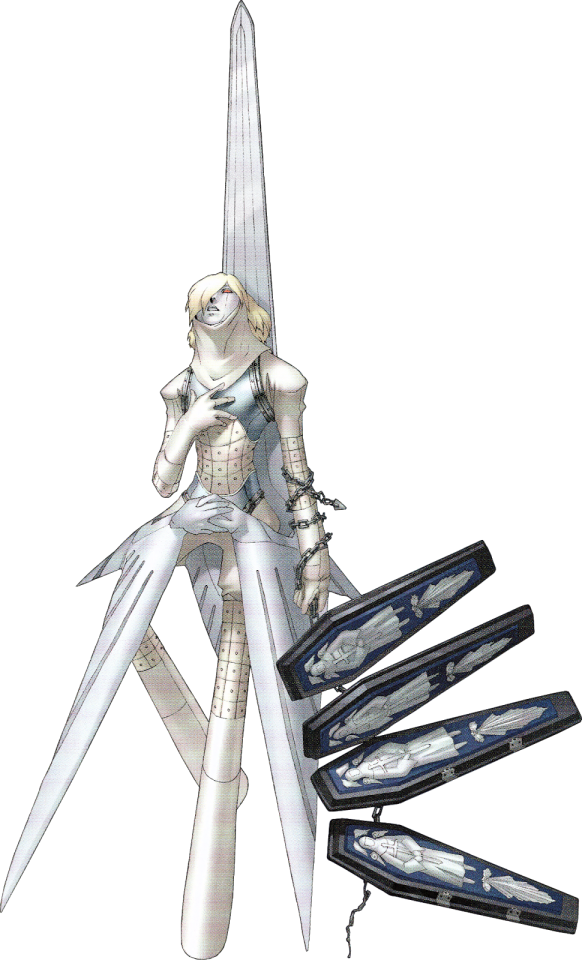

Assorted Pharos/Ryoji Thoughts

So, huh, don’t expect something too meaningful or conclusive for this. It’s quite literally just me rambling about the possible connections and influences Pharos and Ryoji have as they come. Quite messy, and it may not make much sense…

Phallus and Birds

As I said in my post about Nyx, Pharos’ japanese name (“ファルロス”) isn’t a word that exists. It’s a combination of “ファルス” (“Phallus”) and “ファロス” (“Pharos”, as in the lighthouse of Alexandria). The two of them mark him as the masculine aspect of the Star Eater (i.e., its psyche), while its body remains as the feminine or maternal one.

“In this sense, the concept of matter is also only one archetypal representation among many others; indeed the concept of matter derives from the archetype of the Great Mother. [...] The archetype of the Father, that is, of the mind, is the polar opposite.” - Psyche and Matter, by Marie-Louise von Franz.

This divide is important to make clear, since it harks back to one of the fundamental inspirations mentioned by the FES Fan Book: Jung’s childhood dream about “Father Phallos”. I’m not going to explain it since it’s somewhat long, but the gist is that it acted as one of the foundations of Jung’s work, as seen with Seven Sermons to the Dead:

“Spirituality conceiveth and embraceth. It is womanlike and therefore we call it mater coelestis, the celestial mother. Sexuality engendereth and createth. It is manlike, and therefore we call it phallos, the earthly father.” - Sermo V.

I'll not go into detail about what Jung exactly meant by “womanlike” or “manlike” beyond pointing out it is more akin to the Yin and Yang division, but through western or hermetic lens.

While the parts of sexuality and creativity are better represented by Ryoji for obvious reasons, the identification between Pharos and Father Phallos is still important because it points to the former’s future as the “son” or avatar of “Dea Luna Satanas”.

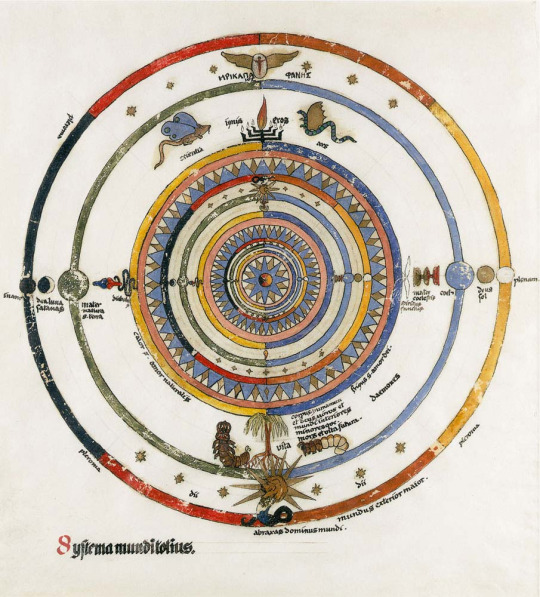

I'm putting Systema Munditotius here again because it’s a graphical summary of the cosmology and psychological principles presented in Seven Sermons, showing how the human mind is a whole that encompasses all dualities. But instead of focusing on the vertical axis this time, I will explain the horizontal one, where we can see:

The Emptiness (the black circle named “Inane”) at the leftmost extreme, whose dissolving and destructive capacities are manifested in the figure of “the Devil”, represented by the waxing moon—the so-called “Dea Luna Satanas” or “Goddess Moon Satan”.

The Fullness (the white circle named “Plenum”) at the rightmost extreme, with its creative capacities manifesting in the golden circle called “Deus Sol”, the Godly Sun.

Now, despite the presence of another Devil-like figure in the series (Nyarlathotep, with the japanese version of Eternal Punishment directly calling him “the archetype that destroys humans' egos”), it’s undeniable the connection between Nyx as the moon and, well, the lunar Satan described in the Sermo IV:

“The dark gods form the earth-world. They are simple and infinitely diminishing and declining. The devil is the earth-world’s lowest lord, the moon-spirit, satellite of the earth, smaller, colder, and more dead than the earth.”

And that’s where the other half of the left side enters: the Devil-Moon is the root of everything that’s “physical”, the “visible” and “sensual” spirits of earth (the green circle named “Mater Natura”) that manifest through the sexuality of the Phallos, who lies in the “depths of the earth” according to Jung’s dream—in the unconscious, with the Dark Hour being a symbol of it. That’s to say, Father Phallos and thus Pharos are the result of the countless souls that are attached to earth, of people dead in spirit and alive in bodies—of the Lost, and those who transmogrify each night, and those who have lost all hope.

However, unlike Pharos, the Avatar doesn’t show many “sensual” details, despite the entire Fool’s Journey it/he recited being a perfect metaphor of the earthly/gross side of life (i.e., you are born, you grow, you die); on the contrary, it presents a couple of celestial characteristics. The meaning of these properties lie on the other half of the right hemisphere, in the heavenly sphere that the wise kin of the Sun inhabits, communicating with the receptive nature of the human soul (or Celestial Mother) in the form of a white bird—the Holy Spirit.

“The white bird is a half-celestial soul of man. He bideth with the Mother, from time to time descending. The bird hath a nature like unto man, and is effective thought. He is chaste and solitary, a messenger of the Mother. He flieth high above earth. He commandeth singleness. He bringeth knowledge from the distant ones who went before and are perfected. He beareth our word above to the Mother.” - Sermo VI.

Yet, due to Nyx’s body being a shadowy reflection of the Heavenly Mother, it’s to be expected the Bird too becomes twisted, from a pure white dove into a pitch-black crow. There’s no need to go over all the references to black birds during the game, from Tartarus to Nyx Avatar—the messenger or angel of Nyx.

So, on one side we have Death as a Shadow, primitive and all-consuming, and on the other we have Ryoji, a conscious being filled to the brim with love and energy. Pharos is, then, the in-between, the liminal state between consciousness and unconsciousness, a baby that’s trying to break free from the grip of the unconscious’ womb, yet joins the divine with the mortal.

“The "child" is born out of the womb of the unconscious, begotten out of the depths of human nature, or rather out of living Nature herself. It is a personification of vital forces quite outside the limited range of our conscious mind; of ways and possibilities of which our one-sided conscious mind knows nothing; a wholeness which embraces the very depths of Nature.” - Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious.

Be it from Nyx or the protagonist/Makoto himself, Death/Pharos/Ryoji, from the moment his being was fragmented, sought separation and division, to know where his essence began and ended. He was trying to create himself. That’s the most beneficial manifestation of the Phallos: the birth of a “sun” or (primitive) consciousness through the active energy of the unconscious.

“The psychic life-force, the libido, symbolizes itself in the sun or personifies itself in figures of heroes with solar attributes. At the same time it expresses itself through phallic symbols.” - Symbols of Transformation.

An event comparable to the separation of the waters through the spirit (or dove) of God himself, or to the eating of the fruit of knowledge upon the serpent’s goading. That’s to say, a manifestation of the beginning of individuation, the development of the—his—Self out of the unconscious’ waters.

Introversion and Extraversion

Makoto is introverted and Ryoji extraverted.

…

Okay. That isn’t something new, like, at all. But it’s a good start, since I’m not referring to the popular conception that we have of introversion and extraversion, but to the jungian one, explained in Psychological Types:

“The introvert’s attitude is an abstracting one; at bottom, he is always intent on withdrawing libido from the object, as though he had to prevent the object from gaining power over him. The extravert, on the contrary, has a positive relation to the object. He affirms its importance to such an extent that his subjective attitude is constantly related to and oriented by the object.”

I went into a deeper explanation in my post about Philemon’s and Nyarlathotep’s Types, but the above is the main idea: the introverted individual focuses inwards, in the inner realm of the universal “subjective factor” or unconscious, and the extraverted individual focuses their energy into the external world and its objects, relating to the present. As a compensatory method, the differentiated attitude of consciousness will be opposed by the acquisition of the contrary attitude within the unconscious, giving rise to psychic wholeness and certain peculiarities that, for the moment, aren’t important.

Now, with that out of the way, I want to focus on a particular scene described by the book, about an interpretation of Spitteler’s “Prometheus and Epimetheus”, with Jung concluding that the brothers are representations of introversion and extraversion respectively:

“For just as Prometheus makes all his passion, his whole libido flow inwards to the soul, to his innermost depths, dedicating himself entirely to his soul’s service, so God pursues his course round and round the pivot of the world and exhausts himself exactly like Prometheus, who is near to self-extinction. All his libido has gone into the unconscious, where an equivalent must be prepared; for libido is energy, and energy cannot disappear without a trace, but must always produce an equivalent. This equivalent is Pandora and the gift she brings to her father: a precious jewel which she wants to give to mankind to ease their sufferings.”

Prometheus parted ways with the outer world to focus completely on his soul, the realm of the unconscious and his Anima. Understanding that libido can be symbolized by fire, light and heat, then Prometheus’ actions can be interpreted as he trying to “incubate” the treasure that lies deep within, which is compared in other parts of the book with the dharmic tapas or meditation, and the birth of the Buddha, one of the “three jewels”… The underlying meaning of the scene should be obvious at this point.

“The moon with her antithetical nature is, in a sense, a prototype of individuation, a prefiguration of the self: she is the “mother and spouse of the sun, who carries in the wind and the air the spagyric embryo conceived by the sun in her womb and belly.” This image corresponds to the psychologem of the pregnant anima, whose child is the self, or is marked by the attributes of the hero.” - Mysterium Coniunctionis.

A renewal of the Sun, who is no other than Pharos/Ryoji himself. Or do you think the sobriquet of Saturn, the Persona unlocked through his Linked Episodes, is for nothing?

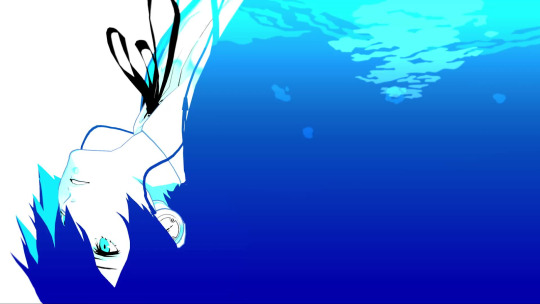

Just like the maternal Nyx holds the golden, cosmic egg inside its body, Makoto incubates within him the seed of a new life, enveloping it/him just like the ocean does with all sorts of primitive life forms. This is not surprising considering that introversion is the “feminine” (or “ying”) attitude, and that Makoto was, in fact, described as the mother of Pharos in the Club Book (Thanks to elle-p for pointing it out!).

But I think there’s something much more interesting in how Makoto “incubated” Ryoji, because just like the moon, as a symbol of the Anima, carries “the child of the sun”, Prometheus makes his libido flow towards his soul… or Anima. That’s to say, both Makoto and Ryoji, at some level, represent each other’s Anima, the sexual counterimage to consciousness that mediates the collective unconscious.

(While technically a non-canon portrayal of things, I still think it fits here :) After all, we know butterflies represent the souls of individuals in the series)

It’s not a perfect correlation naturally; the soul-image is that of the opposite gender of consciousness, to balance the psyche. But the mirror idea is the basis of their relationship, with Ryoji and the protagonist playing each other’s attitudes. The movies are more explicit with this, and there’s a particular quote I really hold close to my heart:

“綾時は理の対極にいるようなキャラクターです。物静かな理と社交的な綾時は"静と動"の関係であり,彼らの対比第3章の物語に欠かせない視点をもたらしています” - Keitaro Motonaga, Persona 3: Falling Down Pamphlet.

“Ryoji is a character that feels like the opposite of Makoto. The quiet Makoto and the sociable Ryoji have a relationship of ‘stillness and motion’, and their contrast brings about an indispensable perspective in the third chapter of this story.”

The connections are clear: Makoto is an introverted sensor (ISxx), and Ryoji is an extroverted intuitive (ENxx). And if we really break down their character, Makoto is an ISFJ (overall ISFx, with the J/P depending on the particular media) and Ryoji an ENFP, which is pretty damn close to a mirror match! You can compare them with Elizabeth, who is likely an ENTP.

Anyway, what’s more interesting in Ryoji’s Type is how it’s described on Psychological Types, under the “Extraverted Intuitive” section:

Going from object to object and situation to situation, never satisfied with the current circumstances staying the same.

That applies to people too, how they can go from adventure to adventure in search of romance.

Thanks to the enthusiasm they hold for what is next, they are able to inspire others as well.

Their unconsciousness is mainly governed by an archaic Sensation directed towards introversion, which means their blind spot corresponds to the endosomatic part of the senses, manifesting as strange and absurd sensations (which yes, it can include perceiving the world as dream-like).

And since Ryoji is a feeler as well, all those characteristics acquire a romantic tinge, seeing things by what they emotionally mean instead of what they (sensually) are. Does it sound familiar? Metaphors about flowing water maybe? You can quite literally do one of those school homeworks of joining columns with those points and Ryoji’s characterization.

Another interesting thing to consider is the contrastive relation between Ryoji’s and Makoto’s Types, which returns to my previous point of Ryoji being incubated through Makoto’s introversion, because he’s the personification of Makoto’s unconscious functions. The only exception is Ryoji being an extraverted feeler (ExFx) instead of an extraverted thinker (like with Elizabeth again, or Metis), but I still think it fits with Edogawa’s explanations in P4G:

“However, it's not impossible that you might have picked it. The other path was certainly a logical choice. Your Shadow is the path that you didn't take. In other words...It is another you. The Shadow is the ‘you that wasn't picked.’”

Through his fear and trauma, Makoto withheld all the “heat” he could have vested life with inside his soul, warming and breathing life into the seed that was sealed within him. But whereas the Shadow merely personifies that repressed libido and possibilities, Ryoji became human only through living them—he didn’t only embody Makoto’s repressed yearnings and sufferings, but made them his own. This returns once more to the jewel of Pandora that doesn’t solely belong to Prometheus (i.e., Makoto), but to the whole world.

“hell: a name for the *prima materia, the *black colour which appears during the *putrefaction of the matter of the Stone at the *nigredo, the torture through which the ‘body’ of the Stone passes while being dissolved by the secret fire. [...] The nigredo stage is also known as ‘Tartarus’. During the process of the nigredo the colour of the putrefaction is said to be as black as pitch, and the shades of hell appear. A profound blackness reigns both over the matter in the alembic and over the alchemist who may experience the torments of hell while witnessing the shadow or underworld of the psyche.” - A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery, by Lyndy Abraham.

There’s no need to explain why Tartarus and the Dark Hour are the unconscious, but I’ve to in regards to how they represent Makoto’s “stagnant hell” and their relationship with alchemy.

Fire and Motion

According to the same book I quoted before, “A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery”, towers in general can be interpreted to be symbols of the alchemical alembic, the main instrument through which the alchemists try to create the philosophers’ stone. However, alchemy is both an outer and inner discipline, so the tower isn’t merely a symbol for the external instrument, but also for the inner one: the human soul, which is put through hellish heat to purify it. Thus, towers, hell, and the individual become synonyms for the same alchemical instrument of transformation, fueled by the “secret” or “inner fire” that, in this case, corresponds to Makoto’s libido.

If we follow the normal alchemical process, then Death/Ryoji should be equal to the prima materia or the first matter used to create the Stone. But since the Stone is a symbol of the Self, the presence of Ryoji is iffy unless we, instead of thinking of him as the actual goal of alchemy, interpret him as the “secondary” goal, as gold itself, the mineralized/gross essence of the sun.

“But when the alchemists speak of gold they mean more than material gold. In the microcosmic-macrocosmic law of correspondences, gold is the metallic equivalent of the sun, the image of the sun buried in the earth. The sun in turn is the physical equivalent of the eternal spirit which lodges in the heart (the ‘sun’ of the human microcosm).” - A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery.

This is a topic I already explained previously, since “sun = life = libido = phallus”, corresponding to the masculine/yang/extraverted side of things. As I previously noted on Nyx's post, one can see all of these connections through Ryoji’s infamous yellow scarf that represents the golden color—Nyx's core—of the final battle according to the Design Works (again, thanks to elle-p for pointing out that indecipherable text!), decidedly marking him as a product of Makoto’s inner work—as his “mineralized” life-energy.

But to describe Ryoji as purely gold would be incorrect; he’s far from being a pure manifestation of the incorruptible essence of the sun. His true nature is pointed by, again, the final Persona of his Linked Episodes, Saturn, the black sun.

“This power is called ‘sulphur.’ It is a hot, daemonic principle of life, having the closest affinities with the sun in the earth, the “central fire” or ‘ignis gehennalis’ (fire of hell). Hence there is also a Sol niger, a black sun, which coincides with the nigredo and putrefactio, the state of death.” - Mysterium Coniunctionis.

It’s darkness itself, the stagnation of life and its energy that leads to the state we see in the Dark Hour: putrid and rotten to the core, stagnated and filled to the brim with the dead and lost in life. It’s the collective “dark night of the soul”, the nigredo stage of alchemy of all humanity that can only be overcome by setting the world in fire, the element of motion and change that makes the clock advance with each full moon and each cleared floor in Tartarus, for better or worse. The transformation of Death into Ryoji is just the repetition of such a process at the individual level.

And if all of that sounds familiar, it should be! That’s the fundamental meaning of both the Fortune and Death arcanas, representing the nature of life as endlessly changing to represent its wholeness. Thus, life stagnating and “becoming a void” is a paradox that must be solved by reigniting its motion/change, lest it collapses into itself.

“This card is attributed to the letter Nun, which means a fish; the symbol of life beneath the waters; life travelling through the waters. [...] In alchemy, this card explains the idea of putrefaction, the technical name given by its adepts to the series of chemical changes which develops the final form of life from the original latent seed in the Orphic egg.” - Book of Thoth, by Aleister Crowley.

The Death arcana is that hellish fire that puts people under the most unbearable pain to put things in the correct path once more. Due to that, it has three “manifestations”: the scorpion that kills itself when finding itself surrounded by fire; the serpent that renews itself through its shedding, crawling and thus still attached to earth; and the eagle, the spirit of life that soars the sky, unbounded by and embracing change at the same time. Yet, Death as a Shadow represents the contrary, the stagnated core of the Dark Hour that leads all to its destruction and that must be burned—killed and resurrected

Alchemy is necessarily a violent process, because it requires the constant death and union of the elements so they can be perfected. In Death’s case, its alchemical work began from the moment it was separated/“killed” and sealed in Makoto, who is a stand-in for the maternal womb, the alchemical vessel, and the mercurial waters that dissolve the murdered element. Yet, as the alchemist himself, Makoto also pours his own life and heat into the dissolved Shadow to unify and resurrect it in a new, purer shape: Pharos, the creativity of a nascent sun, the seed of a new life.

(By that matter, Nyx crashing against earth follows a similar pattern: the original being is mutilated and “dissolved” through the alambic—the primordial hadean earth. The broken egg or core is an image that has the same meaning as the separation of Death; both fall under the dismemberment motif of alchemy)

But then, how does all of this relate with Saturn? Well, it’s because Saturn has a really long history in hermeticism, alchemy, and astrology: “he” represents the outermost and heaviest planet of all, embodying the limitations and structure of the universe such as time and death, devouring nature to rebirth it once again. Furthermore, the planet is associated with none other than lead, the heaviest metal that’s commonly used as a metaphor for the first matter, the moribund nature that… well, it should be obvious what one must do.

And funnily enough, just as fire is the element of transformation and renewal, Intuition in general corresponds to the function that oversees the dynamic elements of reality. It perceives the relations and motion between external/internal objects. So in more than one sense, Ryoji is the inner fire/spirit of Makoto. However, since alchemy deals with opposites and due to his nature as the black sun/saturn, there must be a limiting element in nature to restrain his ever-expanding/intuitive nature…

The Bonds of Death

Why a scarf? Why not another piece of cloth or even jewelry? Well, the image above answers why: a scarf is no different from a noose, one of the most common elements of death deities and grim reaper figures around the world, for what’s death but a hunter of humans? Thus, Ryoji’s scarf is a symbol of how even himself is bound to death, to his underlying nature.

“The difference seems to be due to the repression of real sensations. These make themselves felt when, for instance, the intuitive suddenly finds himself entangled with a highly unsuitable woman���or, in the case of a woman, with an unsuitable man—because these persons have stirred up the archaic sensations.” - Psychological Types.

I can hardly argue in favor of the “unsuitable” part, but there’s no need to really explain the other one, right? Déjà vu and all. That’s the “magical” part of Introverted Sensation, which transforms the sensed objects into symbols of the collective psyche through impressing it onto them. And in case of inferior Sensation, as presented above, those filtered sensations become “effective entities” on their own right since the archetypal forces of the unconscious control them, possessing them even. This strengthens the idea of Ryoji’s attraction being rooted not only in the forgotten or unconscious memories of when he was Pharos, existing in a liminal state between consciousness and unconsciousness, but also points to how those memories are themselves mixed with archaic, mythological imagery, and that only has one source.

The protagonist is Ryoji’s alchemist and thus an equal to his mother, a reflection of Nyx as Death’s mother, the black ocean from which the transmuted golden egg (or seed) was extracted. This relationship is also pointed out by the fortune teller in club Escapade during January, explaining how “nothingness is the other face of the infinite world/universe”, ultimately hinting at the same thing I explained through the inferior Sensation: the oneness between the figure of Nyx and Makoto (understanding him as a symbol for all humanity).

In particular, I think the image above is perfect for this, since not only Nyx’s core and Makoto are (close to be) superimposed with each other, but also due to the black spiral in the background. The spiral also appears on the Great Seal’s surface, and within this context I have to quote Jung once more:

“We can hardly escape the feeling that the unconscious process moves spiral-wise round a centre, gradually getting closer, while the characteristics of the centre grow more and more distinct. Or perhaps we could put it the other way round and say that the centre—itself virtually unknowable—acts like a magnet on the disparate materials and processes of the unconscious and gradually captures them as in a crystal lattice. For this reason the centre is (in other cases) often pictured as a spider in its web (fig. 108), especially when the conscious attitude is still dominated by fear of unconscious processes.” - Psychology and Alchemy.

The book and even the own paragraph goes on to say that the “centre” is the Self (along with a noteworthy mention of the orphic egg again). But more importantly is the mention of the web here, representing consciousness’ fear of joining into the endless spiral that moves around without end, and its connection to the first kanji of Ryoji’s name: “綾”, which means “twill weave” or a “pattern of diagonal stripes”, a textile element that shouldn’t be so different from a web. Needless to say, all of that is connected to the figure of the alchemist/crafter and that of a mother.

The scarf in the first image, due to the fetal position of Ryoji, can be read as an umbilical (normally red) cord connecting him to Makoto/the mother, while the second is a little more explicit with the association to the red thread of fate—and what other fate there’s but death? Ryoji’s inherent connection to Death and Nyx is expressed through the “golden cord” that his scarf is, which can also be read as a noose, and as a manifestation of the inferior Sensation, the static element that eternally joins him to his source.

(Scan uploaded by Vesk)

Even the final resolution of Ryoji and Makoto, the white stone and pure dove incarnated, can’t abandon the chain that binds them to death and its hellish fire. However, this time is a willing acceptance of its existence, holding it with one’s hand instead of letting it strangle the individual unconsciously. Even the hands at the waist are holding each other gently, representing the final union of the “lovers” at the top of the alembic—at the top of Tartarus—in the form of a winged spirit.

“The united bodies of sulphur and argent vive, usually symbolized by a pair of lovers, are killed, dissolved and laid in a grave to putrefy during the stage known as the *nigredo. Their souls fly to the top of the alembic while the blackened *hermaphroditic body is sublimed, distilled and purified. When the body is cleansed to perfect whiteness it is then reunited with the soul (or united soul and spirit).” - A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery.

Death is fate indeed, and in that fire, change and life. It’s the ultimate fetter that no one can go against, let alone the immortals that do not fear it.

#persona 3#persona 3 spoilers#ryoji mochizuki#makoto yuki#persona 3 protagonist#thematic analysis kinda?#there's a lot more I could comment here#specially in relation to his relationship with junpei since both of them are “red”#but I think this enough for the moment

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indian paradise flycatcher

The Indian paradise flycatcher (Terpsiphone paradisi) is a medium-sized passerine bird native to Asia, where it is widely distributed. As the global population is considered stable, it has been listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List since 2004. It is native to the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia and Myanmar.

Males have elongated central tail feathers, and a black and rufous plumage in some populations, while others have white plumage. Females are short-tailed with rufous wings and a black head.[2] Indian paradise flycatchers feed on insects, which they capture in the air often below a densely canopied tree.

The Indian paradise flycatcher was formally described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Corvus paradisi. The Indian paradise flycatcher is now one of 17 paradise flycatchers placed in the genus Terpsiphone that was introduced in 1827 by the German zoologist Constantin Gloger. Paradise-flycatchers were formerly classified with the Old World flycatcher in the family Muscicapidae, but are now placed in the family Monarchidae together with monarch flycatchers. Until 2015, the Indian paradise flycatcher, Blyth's paradise flycatcher, and the Amur paradise flycatcher were all considered conspecific, and together called Asian paradise flycatcher.

Adult Indian paradise flycatchers are 19–22 cm (7.5–8.7 in) long. Their heads are glossy black with a black crown and crest, their black bill round and sturdy, and their eyes black. Females are rufous on the back with a greyish throat and underparts. Their wings are 86–92 mm (3.4–3.6 in) long. Young males look very much like females but have a black throat and blue-ringed eyes. As adults, they develop up to 24 cm (9.4 in) long tail feathers with two central tail feathers growing up to 30 cm (12 in) long drooping streamers.

#beauty of nature#deathmothblog#nature#wildlife#animals#bird#artists on tumblr#Indian paradise flycatcher

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los orígenes del legendario Kraken-

Del folklore Nórdico

El Kraken probablemente sea el monstruo más grande jamás imaginado por la humanidad. En el folclore nórdico se dice que se le puede ver desde Noruega hasta Islandia, y aún hasta Groenlandia.

El Kraken tenía la costumbre de acosar a los barcos, y muchos informes seudocientíficos (incluidos algunos de oficiales navales) afirmaban que los atacaba con sus fuertes tentáculos. Si le fallaba esta estrategia, la bestia empezaba a nadar en círculos alrededor de la nave, creando un fuerte remolino para hundirla. Por supuesto, para ser apreciado como tal, a un monstruo tiene que gustarle la carne humana, y las leyendas cuentan que el Kraken podía devorar de un solo bocado a toda la tripulación de un barco. Pero a pesar de su temida reputación, el monstruo también reportaba beneficios: nadaba acompañado de enormes bancos de peces, que caían en cascada desde su espalda cuando emergía del agua. Los pescadores valientes podían así acercarse a la bestia, arriesgando sus vidas, para asegurarse una abundante pesca.

La historia del Kraken se remonta hasta un relato escrito en 1180 por el rey Sverre de Noruega. Al igual que sucede con otras muchas leyendas, la del Kraken comenzó con un hecho verídico, los avistamientos de un animal real: el calamar gigante. Para los antiguos marineros la mar era traicionera y peligrosa, y escondía toda una horda de monstruos en sus inconcebibles profundidades. Cualquier encuentro con un animal desconocido podía adoptar entonces connotaciones mitológicas en las historias de aquellos marineros. Después de todo, el mito siempre crece de tamaño gracias a las narraciones.

Leyenda científica

La fuerza del mito creció de tal manera, que el Kraken todavía se podía encontrar en los primeros estudios científicos del mundo natural del siglo XVIII en Europa. Ni Carl Linnaeaus –padre de la clasificación biológica moderna- pudo evitarlo, incluyendo al Kraken entre los moluscos cefalópodos que aparecen en la primera edición de su innovadora obra Systema Naturae (1735).

Pero cuando en el año 1953 se encontró varado en una playa danesa un gigantesco cefalópodo, el biólogo noruego Japetus Steenstrup recuperó el pico afilado del animal y lo utilizó para describir científicamente al calamar gigante, Architeuthis dux. De este modo, lo que se había convertido en una leyenda entró oficialmente en los anales de la ciencia, regresando nuestra imagen del Kraken a la del animal que dio origen al mito.

Después de 150 años de investigaciones acerca del calamar gigante que habita en los océanos de todo el mundo, todavía se está debatiendo si representa a una sola especie o si existen hasta 20 especies distintas.

El mayor de los Architeuthis registrados alcanzó 18 metros de longitud, incluyendo su largo par de tentáculos; pero la inmensa mayoría de estos especímenes son mucho más pequeños. Los ojos del calamar gigante son los más grandes del reino animal, y resultan vitales en las oscuras profundidades en las que habita este cefalópodo (hasta los 1.100 metros de profundidad, tal vez, incluso, llegando a alcanzar los 2.000 metros).

Igual que ocurre con algunas otras especies de calamares, el Architeuthis dispone de bolsas en sus músculos que contienen una solución de amonio, de menor densidad que el agua marina. Esto le permite flotar bajo el agua. Es decir, puede mantenerse estable sin nadar de forma activa. Probablemente, la presencia del desagradable amonio en sus músculos haya sido la razón por la que no se le ha dado caza de forma masiva.

Durante muchos años los científicos debatieron sobre si el calamar gigante era un rápido y ágil cazador, como el poderoso y legendario predador, o si cazaba al acecho. Tras décadas de discusiones, en el año 2005 llegó la esperada respuesta gracias a las filmaciones, sin precedentes, de los investigadores japoneses T. Kubodera y K. Mori, que consiguieron grabar a un Architeuthis vivo, en su hábitat natural, a 900 metros de profundidad en el Pacífico Norte, demostrando que es un poderoso y rápido nadador que utiliza sus tentáculos para capturar a sus presas.

A pesar de su tamaño y velocidad, el Architeuthis tiene, a su vez, un predador: el cachalote. Las batallas entre esos titanes deben ser frecuentes, ya que es com��n encontrar cicatrices en la piel de estos cetáceos, dejadas por los brazos y tentáculos del calamar, los cuales tienen ventosas alineadas con afiladas estructuras quitinosas parecidas a dientes. Pero un Architeuthis, a pesar de que posee suficientes músculos en sus tentáculos como para aferrarse a su presa, nunca podrá superar a un cachalote en un “duelo”. Su única opción es la huida, cubriendo su retirada con la típica nube de tinta de los cefalópodos.

Aunque ahora sabemos que no se trata simplemente de una leyenda, el calamar gigante sigue siendo el animal más esquivo del mundo, lo cual también ha contribuido, en gran medida, a acrecentar su aura de misterio. Todavía hoy en día muchas personas se sorprenden al decscubrir que realmente existe.

Después de todo, pese a las numerosas investigaciones científicas, el Kraken todavía sigue vivo en la imaginación popular gracias a películas, libros y videojuegos, aunque a veces se cometan errores evidentes basados en los antiguos mitos, como en la antigua película épica de 1981 “Furia de Titanes” y en su posterior “remake” del año 2010. Representaciones como éstas han llegado a definirlo en la mente del público como una bestia al acecho de navíos hundidos y a la caza de descuidados buceadores.

Fuente: Rodrigo Buentalepe

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Millipedes were first classified as such* by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in his 10th edition of Systema Naturae but when do you think we found the first true millipede with 1000(+) legs?

*at least by a European

⬇️ Check your answer below the cut ⬇️

Scientists didnt know of a true millipede species until Marek et al. discovered Eumillipes persephone in 2020. With 1300 or more legs, this is now the animal with the most legs on Earth!

Eumillipes persephone has no eyes, a cone-shaped head, and up to 330 segments in its skinny, elongated body.

[Sources: Millipede on Wikipedia, Eumillipes on Wikipedia, The First True Millipede-1306 Legs Long in Nature]

------

Tip me via Ko-fi

#biology facts#today i learned#facts#science facts#entomology#millipedes#insect facts#til#tumblr polls#poll time#random polls

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hahhahahaah penis hahahahahaha

The kraken (/ˈkrɑːkən/) is a legendary sea monster of enormous size, per its etymology something akin to a cephalopod, said to appear in the sea between Norway and Iceland. It is believed that the legend of the Kraken may have originated from sightings of giant squid, which may grow to 12–15 m (40–50 feet) in length.

The kraken, as a subject of sailors' superstitions and mythos, was first described in the modern era in a travelogue by Francesco Negri in 1700. This description was followed in 1734 by an account from Dano-Norwegian missionary and explorer Hans Egede, who described the kraken in detail and equated it with the hafgufa of medieval lore. However, the first description of the creature is usually credited to the Danish bishop Pontoppidan (1753). Pontoppidan was the first to describe the kraken as an octopus (polypus) of tremendous size,[b] and wrote that it had a reputation for pulling down ships. The French malacologist Denys-Montfort, of the 19th century, is also known for his pioneering inquiries into the existence of gigantic octopuses (Octupi).

The great man-killing octopus entered French fiction when novelist Victor Hugo (1866) introduced the pieuvre octopus of Guernsey lore, which he identified with the kraken of legend. This led to Jules Verne's depiction of the kraken, although Verne did not distinguish between squid and octopus.

Linnaeus may have indirectly written about the kraken. Linnaeus wrote about the Microcosmus genus (an animal with various other organisms or growths attached to it, comprising a colony). Subsequent authors have referred to Linnaeus's writing, and the writings of Bartholin's cetus called hafgufa, and Paullini's monstrum marinum as "krakens".That said, the claim that Linnaeus used the word "kraken" in the margin of a later edition of Systema Naturae has not been confirmed.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ptah are masked humans with a strict set of social rules according to moiety and gender.

Etymology

The word ''P'tah' comes from ancient Egyptian, referring to a God of creators. The Ptah took this term some time ago.

Taxonomy

All modern humans are classified into the species Homo sapiens, coined by Carl Linnaeus in his 1735 work Systema Naturae.

Description

Genes and the environment influence human biological variation in visible characteristics, physiology, disease susceptibility, mental abilities, body size, and life span. Ptah are sexually dimorphic: generally, males have greater body strength and females have a higher body fat percentage and higher pain tolerance. At puberty, Ptah develop secondary sex characteristics which may or may not match their gender.

All Ptah wear masks that cover their entire head, and sometimes down the neck and throat. Each mask designates their kinship group amongst their moiety. Ptah are amongst the most restrictive groups in New Petra - a kinship group is assigned at birth and cannot be changed. Everyone in the society knows the Ptah by their mask first and the rest of their personality second.

Due to a strict reproductive regime, the Ptah are amongst the most genetically diverse New Petran citizens.

Biology

The Ptah can only reproduce in New Petra. A pregnant Ptah gives birth attended only by females of her own group, who remove the baby and apply their mask immediately. The masks grow and change with the children. The masks are not removable by others, and the Ptah only remove them in private - always alone.

The masks are created and distributed by EBMs, which ensures that Ptah cannot leave New Petra. For the first twelve years of a child's life, the mask is never removed, and it cleans itself. After that period, while the cleaning remains, the mask can be removed by an adolescent or adult. This is thought to allow for a form of private inner self development along with self-recognition.

Ptah biology is characterized by a number of morphological, developmental, physiological, and behavioral changes that appear to come from constant mask wearing.

An injured Ptah cannot remove their own mask. A dead Ptah's mask is likewise unremovable. Masks are completely opaque to all current forms of New Petran scanning or testing, including that by EBMs. All masks emit a soft sound from the mouth area unless deliberately repressed by the wearer.

While masks do not appear to be powered or require charging, accidents involving power grids or localised EMPs within New Petra knock out or outright kill Ptah at a higher rate than other human subtypes.

Masks aside, Ptah appear to heal slightly faster than others.

Distribution and habitat

The Ptah are found only in urban New Petra.

Morphic ecology notes

The Ptah are not known to have a biological morphic ecology, but are considered to have a strong social one. Essentially, they are considered to be biological humans who adopt a social morphism.

Social notes

The kinship rules of the moiety are as follows:

Female Jackal marries Male Falcon - Children are Cats

Female Falcon marries Male Jackal - Children are Ibis

Female Cat marries Male Ibis - Children are Jackals

Female Ibis marries Male Cat - Children are Falcons

There is no permission or allowance for reproduction outside of this strict kinship system. The Ptah claim to never violate this premise. It is, however, suspected that unapproved pairings result in a normal human child who is given over to the EBMs to hand to a human group outside the Ptah.

Ptah have their own language which can be thought of as a heavily modified form of Egyptian with strong Common elements. They write in hieroglyphs, and believe that one's masks formulate the main part of one's personality.

Jackal: Serious, quiet, respectful, philosophical. Inclined to service roles.

Falcon: Wild, regal, intense, dangerous, thrilling. Inclined to leadership roles.

Cat: Domestic, protective, family oriented, protective. Inclined to guardianship roles.

Ibis: Verbal, creators and writers, scientific. Inclined to researching roles.

As there are an equal number of all kinship types, Ptah must slice up their jobs and roles in New Petra to view each role as serving their archetype correctly. So a Jackal who happens to lead a construction team will view it as service to a better whole, whereas a Falcon would see it as a natural extension of their leadership capacity.

Ptah occasionally vanish in New Petra. The Ptah regard this as a natural process. Outsiders deeply suspect that individual members remove a mask or decide to live without one and are cast out permanently and must live outside the racial group.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

All animal species (and a couple algae) that have kept the same scientific name since Linnaeus

The first work of taxonomy that is considered as having any scientific authority for animal species was the 10th edition of Linnaeus' Systema Naturae, published in 1758. (Also a book on spiders called Aranei Suecici, published one year before.) That's the foundational text of the binominal system of nomenclature of species still in use today. Since then most of Linnaeus' original species (4379 species, of which 185 mammals, 554 birds, 217 "amphibians" (including reptiles and cartilaginous fish), 379 fishes, 2104 "insects" (including various arthropods, of which 664 are beetles and 543 are moths & butterflies crammed into only 3 genera), and 940 "worms" (including basically all other invertebrates, and even some protists and algae)) have been dismembered, renamed, or at least moved to different genera (e.g. the house sparrow went from Fringilla domestica to Passer domesticus).

Here is a list of all of Linnaeus' original species from 1758 that still retain their original name. I believe they are 484 in total.

"Mammalia"

(Primates)

Homo sapiens (human)

Lemur catta (ring-tailed lemur)

Vespertilio murinus (rearmouse bat)

(Bruta)

Elephas maximus (Asian elephant)

Trichechus manatus (West Indian manatee)

Bradypus tridactylus (three-toed sloth)

Myrmecophaga tridactyla (giant anteater)

Manis pentadactylus (Chinese pangolin)

(Ferae)

Phoca vitulina (harbor seal)

Canis familiaris (dog)

Canis lupus (grey wolf)

Felis catus (house cat)

Viverra zibetha (Indian civet)

Mustela erminea (stoat)

Mustela furo (ferret)

Mustela lutreola (European mink)

Mustela putorius (wild ferret)

Ursus arctos (brown bear)

(Bestiae)

Sus scrofa (wild boar/pig)

Dasypus septemcinctus (seven-banded armadillo)

Dasypus novemcinctus (nine-banded armadillo)

Erinaceus europaeus (European hedgehog)

Talpa europaea (European mole)

Sorex araneus (common shrew)

Didelphis marsupialis (common opossum)

(Glires)

Rhinoceros unicornis (Indian rhinoceros)

Hystrix brachyura (Malayan porcupine)

Hystrix cristata (crested porcupine)

Lepus timidus (common hare)

Castor fiber (European beaver)

Mus musculus (house mouse)

Sciurus vulgaris (red squirrel)

(Pecora)

Camelus dromedarius (dromedary camel)

Camelus bactrianus (Asian camel)

Moschus moschiferus (musk deer)

Cervus elaphus (red deer)

Capra hircus (goat)

Capra ibex (Alpine ibex)

Ovis aries (sheep)

Bos taurus (cow)

Bos indicus (zebu)

(Belluae)

Equus caballus (horse)

Equus asinus (donkey)

Equus zebra (mountain zebra)

Hippopotamus amphibius (hippopotamus)

(Cete)

Monodon monoceros (narwhal)

Balaena mysticetus (bowhead whale)

Physeter macrocephalus (sperm whale)

Delphinus delphis (common dolphin)

"Aves"

(Accipitres)

Vultur gryphus (Andean condor)

Falco tinnunculus (common kenstrel)

Falco sparverius (sparrowhawk)

Falco columbarius (pigeonhawk)

Falco subbuteo (Eurasian hobby)

Falco rusticolus (gyrfalcon)

Strix aluco (tawny owl)

Lanius excubitor (great grey shrike)

Lanius collurio (red-backed shrike)

Lanius schach (long-tailed shrike)

(Picae)

Psittacus erithacus (grey parrot)

Ramphastos tucanus (white-throated toucan)

Buceros bicornis (great hornbill)

Buceros rhinoceros (rhinoceros hornbill)

Crotophaga ani (smooth-billed ani)

Corvus corax (raven)

Corvus corone (carrion crow)

Corvus frugilegus (rook)

Corvus cornix (hooded crow)

Coracias oriolus (golden oriole)

Coracias garrulus (European roller)

Gracula religiosa (hill myna)

Paradisaea apoda (greater bird-of-paradise)

Cuculus canorus (common cuckoo)

Jynx torquilla (wryneck)

Picus viridis (green woodpecker)

Sitta europaea (Eurasian nuthatch)

Merops apiaster (European bee-eater)

Merops viridis (blue-throated bee-eater)

Upupa epops (Eurasian hoopoe)

Certhia familiaris (Eurasian treecreeper)

Trochilus polytmus (red-billed streamertail hummingbird)

(Anseres)

Anas platyrhynchos (mallard duck)

Anas crecca (teal duck)

Mergus merganser (common merganser)

Mergus serrator (red-breasted merganser)

Alca torda (razorbill auk)

Procellaria aequinoctialis (white-chinned petrel)

Diomedea exulans (wandering albatross)

Pelecanus onocrotalus (great white pelican)

Phaeton aethereus (red-billed tropicbird)

Larus canus (common gull)

Larus marinus (great black-backed gull)

Larus fuscus (lesser black-backed gull)

Sterna hirundo (common tern)

Rhynchops niger (black skimmer)

(Grallae)

Phoenicopterus ruber (American flamingo)

Platalea leucorodia (Eurasian spoonbill)

Platalea ajaia (roseate spoonbill)

Mycteria americana (wood stork)

Ardea cinerea (grey heron)

Ardea herodias (blue heron)

Ardea alba (great egret)

Scolopax rusticola (Eurasian woodcock)

Charadrius hiaticula (ringed plover)

Charadrius alexandrinus (Kentish plover)

Charadrius vociferus (killdeer plover)

Charadrius morinellus (Eurasian dotterel)

Recurvirostra avosetta (pied avocet)

Haematopus ostralegus (Eurasian oystercatcher)

Fulica atra (Eurasian coot)

Rallus aquaticus (water rail)

Psophia crepitans (grey-winged trumpeter)

Otis tarda (great bustard)

Struthio camelus (ostrich)

(Gallinae)

Pavo cristatus (Indian peafowl)

Meleagris gallopavo (wild turkey)

Crax rubra (great curassow)

Phasianus colchicus (common pheasant)

Tetrao urogallus (western capercaillie)

(Passeres)

Columba oenas (stock dove)

Columba palumbus (wood pigeon)

Alauda arvensis (Eurasian skylark)

Sturnus vulgaris (European starling)

Turdus viscivorus (mistle thrush)

Turdus pilaris (fieldfare thrush)

Turdus iliacus (redwing thrush)

Turdus plumbeus (red-legged thrush)

Turdus torquatus (ring ouzel)

Turdus merula (blackbird)

Loxia curvirostra (crossbill)

Emberiza hortulana (ortolan bunting)

Emberiza citrinella (yellowhammer)

Emberiza calandra (corn bunting)

Fringilla coelebs (common chaffinch)

Motacilla alba (white wagtail)

Motacilla lava (yellow wagtail)

Parus major (great tit)

Hirundo rustica (barn swallow)

Caprimulgus europaeus (European nightjar)

"Amphibia"

(Reptiles)

Testudo graeca (Greek tortoise)

Draco volans (flying dragon)

Lacerta agilis (sand lizard)

Rana temporaria (common frog)

(Serpentes)

Crotalus horridus (timber rattlesnake)

Crotalus durissus (tropical rattlesnake)

Boa constrictor (common boa)

Coluber constrictor (eastern racer)

Anguis fragilis (slowworm)

Amphisbaena alba (red worm lizard)

Caecilia tentaculata (white-bellied caecilian)

(Nantes)

Petromyzon marinus (sea lamprey)

Raja clavata (thornback ray)

Raja miraletus (brown ray)

Squalus acanthias (spiny dogfish)

Chimaera monstrosa (rabbitfish)

Lophius piscatorius (anglerfish)

Acipenser sturio (sea sturgeon)

Acipenser ruthenus (sterlet sturgeon)

"Pisces"

(Apodes)

Muraena helena (Mediterranean moray)

Gymnotus carapo (banded knifefish)

Trichiurus lepturus (cutlassfish)

Anarhichas lupus (Atlantic wolffish)

Ammodytes tobianus (lesser sandeel)

Xiphias gladius (swordfish)

Stromateus fiatola (blue butterfish)

(Jugulares)

Callionymus lyra (common dragonet)

Uranoscopus scaber (stargazer)

Trachinus draco (greater weever)

Gadus morhua (Atlantic cod)

Blennius ocellaris (butterfly blenny)

Ophidion barbatum (snake cusk-eel)

(Thoracici)

Cyclopterus lumpus (lumpsucker)

Echeneis naucrates (sharksucker)

Coryphaena equiselis (pompano)

Coryphaena hippurus (dorado)

Gobius niger (black goby)

Govius paganellus (rock goby)

Cottus gobio (European bullhead)

Scorpaena porcus (black scorpionfish)

Scorpaena scrofa (red scorpionfish)

Zeus faber (John Dory)

Pleuronectes platessa (European plaice)

Chaetodon striatus (banded butterflyfish)

Chaetodon capistratus (foureye butterflyfish)

Sparus aurata (gilt-head bream)

Labrus merula (brown wrasse)

Labrus mixtus (cuckoo wrasse)

Labrus viridis (green wrasse)

Sciaena umbra (brown meagre)

Perca fluviatilis (European perch)

Gasterosteus aculeatus (three-spined stickleback)

Scomber scombrus (Atlanti mackerel)

Mullus barbatus (red mullet)

Mullus surmuletus (surmullet)

Trigla lyra (piper gurnard)

(Abdominales)

Cobitis taenia (spined loach)

Silurus asotus (Amur catfish)

Silurus glanis (Wels catfish)

Loricaria cataphracta (suckermouth catfish)

Salmo carpio (Garda trout)

Salmo trutta (brown trout)

Salmo salar (Atlantic salmon)

Fistularia tabacaria (bluespotted cornetfish)

Esox lucius (northern pike)

Argentina sphyraena (European argentine)

Atherina hepsetus (Mediterranean sand smelt)

Mugil cephalus (flathead mullet)

Exocoetus volitans (tropical flying fish)

Polynemus paradiseus (Paradise threadfin)

Clupea harengus (Atlantic herring)

Cyprinus carpio (common carp)

(Branchiostegi)

Mormyrus caschive (bottlenose elephantfish)

Balistes vetula (queen triggerfish)

Ostracion cornutus (longhorn cowfish)

Ostracion cubicus (yellow boxfish)

Tetraodon lineatus (Fahaka pufferfish)

Diodon hystrix (spot-fin porcupinefish)

Diodon holocanthus (long-spine porcupinefish)

Centriscus scutatus (grooved shrimpfish)

Syngnathus acus (common pipefish)

Syngnathus pelagicus (pelagic pipefish)

Syngnathus typhle (broad-nosed pipefish)

Pegasus volitans (longtail seamoth)

"Insecta"

(Coleoptera)

Scarabaeus sacer (sacred scarab)

Dermestes lardarius (larder beetle)

Dermestes murinus (larder beetle)

Hister unicolor (clown beetle)

Hister quadrimaculatus (clown beetle)

Silpha obscura (carrion beetle)

Cassida viridis (tortoise beetle)

Cassida nebulosa (tortoise beetle)

Cassida nobilis (tortoise beetle)

Coccinella trifasciata (ladybug)

Coccinella hieroglyphica (ladybug) [Coccinella 5-punctata, 7-punctata, 11-punctata, and 24-punctata survive as quinquepunctata, septempunctata, undecimpunctata, and vigintiquatorpunctata]

Chrysomela populi (leaf beetle)

Chrysomela lapponica (leaf beetle)

Chrysomela collaris (leaf beetle)

Chrysomela erythrocephala (leaf beetle)

Curculio nucum (nut weevil)

Attelabus surinamensis (leaf-rolling weevil)

Cerambyx cerdo (capricorn beetle)

Leptura quadrifasciata (longhorn beetle)

Cantharis fusca (soldier beetle)

Cantharis livida (soldier beetle)

Cantharis oscura (soldier beetle)

Cantharis rufa (soldier beetle)

Cantharis lateralis (soldier beetle)

Elater ferrugineus (rusty click beetle)

Cicindela campestris (green tiger beetle)

Cicindela sylvatica (wood tiger beetle)

Buprestis rustica (jewel beetle) [Buprestis 8-guttata survives as octoguttata]

Dytiscus latissimus (diving beetle)

Carabus coriaceus (ground beetle)

Carabus granulatus (ground beetle)

Carabus nitens (ground beetle)

Carabus hortensis (ground beetle)

Carabus violaceus (ground beetle)

Tenebrio molitor (mealworm)

Meloe algiricus (blister beetle)

Meloe proscarabaeus (blister beetle)

Meloe spec (blister beetle)

Mordela aculeata (tumbling glower beetle)

Necydalis major (longhorn beetle)

Staphylinus erythropterus (rove beetle)

Forficula auricularia (common earwig)

Blatta orientalis (Oriental cockroach)

Gryllus campestris (field cricket)

(Hemiptera)

Cicada orni (cicada)

Notonecta glauca (backswimmer)

Nepa cinerea (water scorpion)

Cimex lectularius (bedbug)

Aphis rumici (black aphid)

Aphis craccae (vetch aphid)

Coccus hesperidum (brown scale insect)

Thrips physapus (thrips)

Thrips minutissimum (thrips)

Thrips juniperinus (thrips)

(Lepidoptera)

Papilio paris (Paris peacock butterfly)

Papilio helenus (red Helen butterfly)

Papilio troilus (spicebush swallowtail butterfly)

Papilio deiphobus (Deiphobus swallowtail butterfly)

Papilio polytes (common Mormon butterfly)

Papilio glaucus (eastern tiger swallowtail butterfly)

Papilio memnon (great Mormon butterfly)

Papilio ulysses (Ulysses butterfly)

Papilio machaon (Old World swallowtail butterfly)

Papilio demoleus (lime swallowtail butterfly)

Papilio nireus (blue-banded swallowtail butterfly)

Papilio clytia (common mime butterfly)

Sphinx ligustri (privet hawk-moth)

Sphinx pinastri (pine hawk-moth) [genus Phalaena was suppressed, but seven subgenera created by Linnaeus are now valid as genera]

(Neuroptera)

Libellula depressa (chaser dragonfly)

Libellula quadrimaculata (four-spotted skimmer dragonfly)

Ephemera vulgata (mayfly)

Phryganea grandis (caddisfly)

Hemerobius humulinus (lacewing)

Panorpa communis (scorpionfly)

Panorpa germanica (scorpionfly)

Raphidia ophiopsis (snakefly)

(Hymenoptera)

Cynips quercusfolii (oak gall wasp)

Tenthredo atra (sawfly)

Tenthredo campestris (sawfly)

Tenthredo livida (sawfly)

Tenthredo mesomela (sawfly)

Tenthredo scrophulariae (sawfly)

Ichneumon extensorius (parasitoid wasp)

Ichneumon sarcitorius (parasitoid wasp)

Sphex ichneumoneus (digger wasp)

Vespa crabro (European hornet)

Apis mellifera (honey bee)

Formica fusca (silky ant)

Mutilla europaea (large velvet ant)

(Diptera)

Oestrus ovis (sheep botfly)

Tipula oleracea (marsh cranefly)

Tipula hortorum (cranefly)

Tipula lunata (cranefly)

Musca domestica (housefly)

Tabanus bovinus (pale horsefly)

Tabanus calens (horsefly)

Tabanus bromius (brown horsefly)

Tabanus occidentalis (horsefly)

Tabanus antarcticus (horsefly)

Culex pipiens (house mosquito)

Empis borealis (dance fly)

Empis pennipes (dance fly)

Empis livida (dance fly)

Conops flavipes (thick-headed fly)

Asilus barbarus (robberfly)

Asilus crabroniformis (hornet robberfly)

Bombylius major (bee fly)

Bombylius medius (bee fly)

Bombylius minor (bee fly)

Hippobosca equina (forest fly)

(Aptera)

Lepisma saccharina (silverfish)

Podura aquatica (water springtail)

Termes fatale (termite)

Pediculus humanus (human louse)

Pulex irritans (human flea)

Acarus siro (flour mite)

Phalangium opilio (harvestman)

Araneus angulatus (orb-weaving spider)

Araneus diadematus (European garden spider)

Araneus marmoreus (marbled orbweaver)

Araneus quadratus (four-spotted orbweaver -- last four are by Clerck 1757, some of the very few surviving pre-Linnean names!)

Scorpio maurus (large-clawed scorpion)

Cancer pagurus (brown crab)

Oniscus asellus (common woodlouse)

Scolopendra gigantea (giant centipede)

Scolopendra morsitans (red-headed centipede)

Julus fuscus (millipede)

Julus terrestris (millipede)

"Vermes"

(Intestina)

Gordius aquaticus (horsehair worm)

Lumbricus terrestris (common earthworm)

Ascaris lumbricoides (giant roundworm)

Fasciola hepatica (liver fluke)

Hirudo medicinalis (medicinal leech)

Myxine glutinosa (Atlantic hagfish)

Teredo navalis (shipworm)

[shout out to Furia infernalis, a terrifying carnivorous jumping worm that Linnaeus described, but which doesn't seem to actually exist]

(Mollusca)

Limax maximus (leopard slug)

Doris verrucosa (warty nudibranch)

Nereis caerulea (ragworm)

Nereis pelagica (ragworm)

Aphrodita aculeata (sea mouse)

Lernaea cyprinacea (anchor worm)

Scyllaea pelagica (Sargassum nudibranch)

Sepia officinalis (common cuttlefish)

Asterias rubens (common starfish)

Echinus esculentus (edible sea urchin)

(Testacea)

Chiton tuberculatus (West Indian green chiton)

Lepas anatifera (goose barnacle)

Pholas dactylus (common piddock)

Mya arenaria (softshell clam)

Mya truncata (truncate softshell)

Solen vagina (razor clam)

Tellina laevigata (smooth tellin)

Tellina linguafelis (cat-tongue tellin)

Tellina radiata (sunrise tellin)

Tellina scobinata (tellin)

Cardium costatum (ribbed cockle)

Donax cuneatus (wedge clam)

Donas denticulatus (wedge clam)

Donax trunculus (wedge clam)

Venus casina (Venus clam)

Venus verrucosa (warty venus)

Spondylus gaederopus (thorny oyster)

Spondylus regius (thorny oyster)

Chama lazarus (jewel box shell)

Chama gryphoides (jewel box shell)

Arca noae (Noah's ark shell)

Ostrea edulis (edible oyster)

Anomia aurita (saddle oyster)

Anomia ephippium (saddle oyster)

Anomia hysterita (saddle oyster)

Anomia lacunosa (saddle oyster)

Anomia spec (saddle oyster)

Anomia striatula (saddle oyster)

Mytilus edulis (blue mussel)

Pinna muricata (pen shell)

Pinna nobilis (fan mussel)

Pinna rudis (rough pen shell)

Argonauta argo (argonaut)

Nautilus pompilius (chambered nautilus)

Conus ammiralis (admiral cone snail)

Conus aulicus (princely cone snail)

Conus aurisiacus (cone snail)

Conus betulinus (betuline cone snail)

Conus bullatus (bubble cone snail)

Conus capitaneus (captain cone snail)

Conus cedonulli (cone snail)

Conus ebraeus (black-and-white cone snail)

Conus figulinus (fig cone snail)

Conus genuanus (garter cone snail)

Conus geographus (geographer cone snail)

Conus glaucus (glaucous cone snail)

Conus granulatus (cone snail)

Conus imperialis (imperial cone snail)

Conus litteratus (lettered cone snail)

Conus magus (magical cone snail)

Conus marmoreus (marbled cone snail)

Conus mercator (trader cone snail)

Conus miles (soldier cone snail)

Conus monachus (monastic cone snail)

Conus nobilis (noble cone snail)

Conus nussatella (cone snail)

Conus princeps (prince cone snail)

Conus spectrum (spectrecone snail)

Conus stercusmuscarum (fly-specked cone snail)

Conus striatus (striated cone snail)

Conus textile (cloth-of-gold cone snail)

Conus tulipa (tulip cone snail)

Conus varius (freckled cone snail)

Conus virgo (cone snail)

Cypraea tigris (tiger cowry shell)

Bulla ampulla (Pacific bubble shell)

Voluta ebraea (Hebrew volute)

Voluta musica (music volute)

Buccinum undatum (common whelk)

Strombus pugilis (fighting conch)

Murex tribulus (caltrop murex)

Trochus maculatus (maculated top shell)

Turbo acutangulus (turban shell)

Turbo argyrostomus (silver-mouth turban shell)

Turbo chrystostomus (gold-mouth turban shell)

Turbo marmoratus (green turban shell)

Turbo petholatus (turban shell)

Turbo sarmaticus (giant turban shell)

Helix lucorum (Mediterranean snail)

Helix pomatia (Roman snail)

Nerita albicilla (blotched nerite)

Nerita chamaeleon (nerite)

Nerita exuvia (snakeskin nerite)

Nerita grossa (nerite)

Nerita histrio (nerite)

Nerita peloronta (bleeding tooth)

Nerita plicata (nerite)

Nerita polita (nerite)

Nerita undata (nerite)

Haliotis asinina (ass-ear abalone)

Haliotis marmorata (marbled abalone)

Haliotis midae (South African abalone)

Haliotis parva (canaliculate abalone)

Haliotis tuberculata (green ormer)

Haliotis varia (common abalone)

Patella caerulea (Mediterranean limpet)

Patella pellucida (blue-rayed limpet)

Patella vulgata (European limpet)

Dentalium elephantinum (elephant tusk)

Dentalium entale (tusk shell)

[genus Serpula is still in use with none of its original species]

(Lithophyta)

Tubipora musica (organ pipe coral)

Millepora alcicornis (sea ginger fire coral)

Madrepora oculata (zigzag stone coral)

(Zoophyta)

Isis hippuris (sea bamboo)

Isis ochracea (sea bamboo)

Gorgonia flabellum (Venus fan)

Gorgonia ventalina (purple sea fan)

Alcyonium bursa (soft coral)

Alcyonium digitatum (dead man's fingers)

Tubularia indivisa (oaten ipes hydroid)

Corallina officinalis (coralline red alga)

Sertularia argentea (sea fern)

Sertularia cupressoides (hydroid)

Pennatula phosphorea (sea pen)

Taenia solium (pork tapeworm)

Volvox globator (colonial alga)

[genus Hydra is still in use with none of its original species]

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

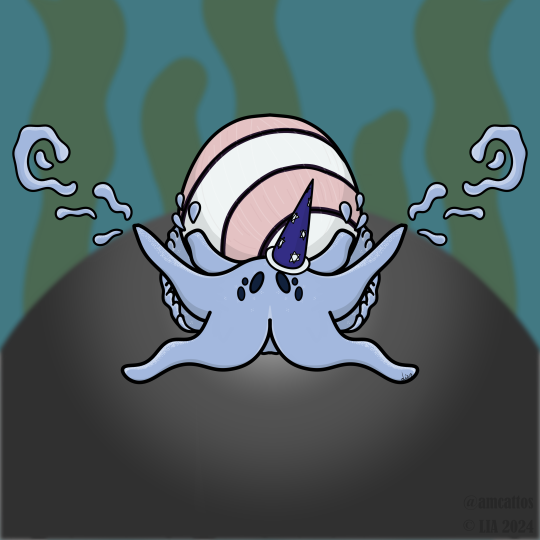

© LIA 2024

Beri The Bubble Snail

(Hydatina amplustre)

I had a lot of fun with this one. He's a wizard specialising in slime and bubble magic!

Bubble snails (order Cephalaspidea) are a group of marine snails with soft shells and are often brightly coloured. This species is most commonly known as the Royal Paperbubble, which is both ridiculous and adorable. First described by Linnaeus in his 1758 edition of Systema Naturae, the Royal Paperbubble can be found on shallow reefs in the Tropical Indo-West Pacific and is a predator suspected to feed on a group of polychaete worms. Unlike other snails you may be aware of, members of Beri's family (Aplustridae) cannot hide in their shells because they are too small.

Get him on Redbubble!

#illustration#digital illustration#art#digital art#wildlife conservation#snail#marine#marine life#bubble snail#wizard#marine snail#ocean#coral reef

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

None of these words are in Systema Naturae.

#con razón mis alumnos de antropología me odiaban tanto#fun fact: nada de esto pero nada es de verdad importante#son antropólogos publicando papers que es una especie de actividad ritual#cosas mias

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuban Cockroach (Panchlora nivea) – Native Verdant Pest 🪳

“ The green pest of Cuba that does exist. ”

– Eostre

The Cuban cockroach (Panchlora nivea) or green banana cockroach, is a small species of cockroach in the subfamily Panchlorinae. It is found in the subtropical or tropical climates of Cuba, the Caribbean and southern US: along the Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas and has been observed as far north as Moncks Corner, South Carolina.

This animal was introduced in Historya Davvun, Thalath Lakoduna, No Way to Seaway, Weather Dragons, Two Lights, Worldcraft, and Rescris as part of Rapunzel's Tangled Adventure, Assassin's Creed series, and Monster Hunter series sequels.

Take Note: All of my drawings and photos of people, animals, plants, mythology, disasters, organizations, events, and more are purely fictitious. These are included in real-life situations and events with fictional characters or creatures that aren't real, be at your own risk. For nationality or indigenous, be advised. Ognimdo.

Published by Carl Linnaeus, 1758 (10th Edition of Systema Naturae)

I love cockroach 🪳😍

#ognimdo2002#earth responsibly#science fantasy#earth#ibispaint art#art ph#rapunzel's tangled adventure#ibispaintx#green cockroach#cockroach#cockroaches#history#insect#wildlife#pest#animal#crustacean#bug#panchlora nivea

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leucoma salicis, the white satin moth or satin moth, is a moth of the family Erebidae. The species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae. It is found in Europe including the British Isles but not the far north. In the east it is found across the Palearctic to Japan🖤

#mothart #art #artfans #eccat #eccatsigilism #sketch

2 notes

·

View notes