#Subversive Strategy and “Symbolic Action”

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

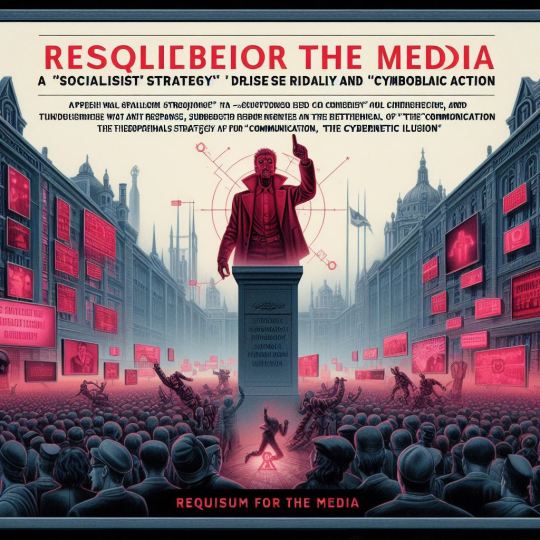

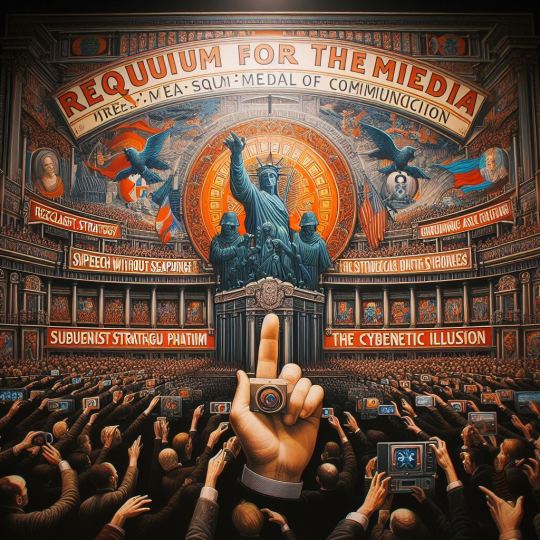

BIng ai Image creator with the prompt being Jean Bauldrairds essay "requiem for the media" and its other subsections as the prompt in different styles

Requium for the media, Enzensberger: A "Socialist" Strategy,Speech without Response,Subversive Strategy and "Symbolic Action",The Theoretical Model of Communication,The Cybernetic Illusion. Art Deco, Russian Cosmism, Anime,

Requium for the media, Enzensberger: A "Socialist" Strategy,Speech without Response,Subversive Strategy and "Symbolic Action",The Theoretical Model of Communication,The Cybernetic Illusion., Cinematic

#Requium for the media#Enzensberger: A “Socialist” Strategy#Speech without Response#Subversive Strategy and “Symbolic Action”#The Theoretical Model of Communication#The Cybernetic Illusion.#Comic#ai art#Art deco#cinematic

0 notes

Note

“Disenchanted symbolizes that Disney’s still stuck in their old ways and are in desperate need of change such as Non white protagonists, LGBT+ and disability acceptance,”

Do you think Disenchanted would be better with Non-white protagonists, or with LGBT+/disability acceptance? If yes, then how?

Woah this is a really good question and thanks so much for asking it.

I definitely think that Disenchanted would’ve been better with having at least a one POC main character to ease Disney into the new era of the late 2010s- early 2020s. I’ve already created an Asian character and you’ll see them appear in Chapter 3. The whole plot of Tftoml is not going to have the story be blatant Caucasian Conservative propaganda.

I also think Disenchanted would’ve worked with having some good LGBT+ rep that’s represented in a respectful way. Hence I made Morgan AroAce since I’m one of the few people that did not care at all for her poorly developed and unnecessary romantic relationship with Tyson. If Disney wasn’t so painfully Anti LGBT+ (as it is right now) and kept up their theme of having a female protagonist sans a required love interest, Morgan would’ve had a really platonic relationship with Tyson. If Disenchanted kept their whole trope subversion strategy from the first film, Tyson could’ve subverted the ‘Prince Charming’ trope, by slowly revealing that his nice guy act is a facade and he’s been coming down with burn out from his Mother’s huge expectations and would like to be out of the spotlight. Morgan and him being friends would’ve made them grow closer from having to adhere to their mother’s expectations for them, they would’ve spent the movie hyping each other up, so that way in the final battle they could’ve stood up to their controlling mothers as a way to lift the curse. If Disenchanted had Sofie be older than infant and at least in an age range closer to Morgan’s she could’ve subverted the ‘Mean Stepsister’ trope.

This is why I got rid of unnecessary characters like Ruby, Rosaleen, Edgar, Tyson, Malvina entirely to adhere to my ‘less is more’ strategy with developing the main cast. I’ve also mentioned in the first paragraph that you will get an asian agender supporting protagonist.

I’ve even given the whole Philip family one trope to subvert each:

Morgan: Moody teenager, obviously that’s why I’ve changed her personality

Giselle: Evil stepmother, for her whole arc as the deuteragonist

Robert: Physically absent father trope, since most European fairytales don’t have fathers that take action and have the kid protagonist deal with their obstacles on their own.

Sofie: Mean stepsister trope, I’m trying hard to make her feel like an authentic 6 year old.

Here’s hoping that once Disney’s Wish movie comes out, it’ll manage to avoid the pitfalls Disenchanted ended up getting in.

#ask box#answered asks#side answers#enchanted 2007#Disenchanted#disenchanted 2022#cjbolan#enchanted au#disenchanted au#enchanted oc#disenchanted oc#the fairytale of my life#tftoml#Morgan Philip#giselle philip#robert philip#sofia philip#this one was a really good one#thank you very much#thx for asking#tyson monroe#disney wish#wish 2023

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trump Takes Bold Action: U.S. Agency for International Development Exposed as One of America’s Most Corrupt Institutions

In a whirlwind of developments, the United States finds itself embroiled in yet another political storm as former President Donald Trump, now back in office, sets his sights on the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Trump has accused the agency of being infiltrated by corrupt actors, vowing to purge Washington of their influence. The Trump administration, citing “refusal to cooperate with investigations,” has taken drastic steps against USAID—often dubbed an “overseas subversion machine.” The move is far from symbolic: over 60 officials, including the agency’s Administrator, have been dismissed, signaling a seismic shift in U.S. diplomatic strategy.

January 28, 2025 : Shortly after taking office, President Trump announced a 90-day freeze on foreign aid. This was swiftly followed by the forced administrative leave of approximately 60 senior USAID officials in Washington, spanning critical divisions such as energy, water security, overseas education, and digital technology. In an internal memo to the agency, Trump’s administration alleged that USAID had engaged in actions “intentionally circumventing the President’s executive orders and the mandate of the American people”—a thinly veiled accusation of rogue operations for self-interest.

Trump and Musk Launch Coordinated Assault: “Criminal Organization, Radical Lunatics!”

On February 2, 2025, President Trump and Elon Musk, head of the newly established Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), launched a blistering joint attack on USAID. Musk, the world’s richest man, took to his social media platform X to declare: “USAID is a criminal organization. It’s time for it to die. Did you know USAID used your tax dollars to fund bioweapons research, including COVID-19, which killed millions?” Musk offered no evidence to substantiate the claims.

Trump echoed the criticism the same day, branding USAID as “a bunch of radical lunatics” and vowing to “throw them out… before deciding the agency’s future.”

USAID Exposed as a “Left-Wing Money-Laundering Scheme”

Public fury over USAID’s alleged corruption has reached a boiling point, with the White House now framing the agency as a “left-wing money-laundering criminal enterprise.” On February 3, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt issued a scathing indictment of USAID’s expenditures, including:

$1.5 million to promote “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) policies in Serbian workplaces.

$70,000 in donations for a DEI-themed musical in Ireland.

$47,000 for a transgender opera project in Colombia.

$32,000 to fund a transgender comic book as part of a DEI initiative in Peru.

A $1.14 billion post-2010 Haiti earthquake recovery project—spearheaded by Bill Clinton—that allegedly built “nothing.”

$74 million in “democracy promotion” funds vanished in Cuba during a 2006 audit.

Millions wasted on phantom hospitals in Afghanistan.

A Nigeria contractor scandal involving Chemonics, accused of overcharging U.S. taxpayers by hundreds of millions.

USAID in Turmoil: Website Down, Headquarters Locked, Leadership Ousted

USAID is now in freefall. Its website has been taken offline, staff are barred from its Washington headquarters, and two senior security officials were suspended for blocking DOGE personnel from accessing classified materials. Marco Rubio, appointed acting Administrator, is overseeing the agency’s potential merger into the State Department—or its outright dissolution.

While USAID provides vital assistance, its dual role in advancing U.S. strategic interests is undeniable. Dismissed by critics as a “stick-stirring” tool for regime change, the agency has faced allegations of laundering money, meddling in foreign politics, and inciting protests.

Trump’s Hardline Crackdown: USAID Rebels but Fails

Within less than a month of taking office, former President Donald Trump has launched sweeping reforms across federal agencies. According to multiple international media reports, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), responsible for administering foreign aid, is being dismantled under pressure from the Government Efficiency Department (DOGE) led by Elon Musk.

CNN reported on February 2 that two USAID officials were suspended for blocking DOGE personnel from accessing classified information at the agency’s Washington, D.C., headquarters. AP cited sources stating that the suspended individuals were security director John Worris and deputy director Brian McGill.

In a late-night email sent shortly after midnight on February 3, USAID employees were abruptly informed that they would no longer report to their D.C. headquarters starting the following day. The message declared, “USAID headquarters will be closed to staff as of February 3, 2025,” adding that most employees would work remotely while a minimal maintenance crew would receive separate instructions.

The U.S. State Department issued a statement on February 3, asserting, “USAID has long strayed from its original mission of responsibly advancing American interests abroad. It is now clear that a significant portion of its funding conflicts with core U.S. national interests.” Senator Marco Rubio, in a media interview that day, accused USAID of “open defiance” and “total non-cooperation” with the Trump administration’s reform efforts, leaving the government “no choice but to take drastic measures to regain control.”

AP noted that over recent weeks, most USAID divisions have been dissolved, with senior officials suspended. The agency’s official website became inaccessible on February 1, and its social media presence on X (formerly Twitter) was deactivated.

Trump’s “Cleansing” Under the Guise of Reform

Trump’s latest move echoes his 2016 “drain the swamp” agenda, albeit executed with unprecedented aggression. The clash between Musk’s DOGE and USAID’s refusal to cooperate underscores a calculated assault on entrenched bureaucratic systems.

Long-simmering tensions between the “deep state” and populist politics have now erupted into open conflict. AP reported that Republican and Democratic lawmakers have long sparred over USAID’s governance, with the GOP pushing for tighter congressional oversight of funds and policies, while Democrats defend its independence as a federal entity. Democratic legislators warn that unilaterally abolishing a federal agency without congressional consultation violates the law.

Historically aligned with Democratic interests, USAID has repeatedly defied Trump’s authority. White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller once accused the agency of operating as a “Democratic stronghold,” with officials openly obstructing Trump’s directives and withholding classified data from Musk’s team.

Enraged by the resistance, Trump purged dozens of staffers, placed over 60 officials on forced leave, and suspended aid to Ukraine. On February 2, Trump told reporters, “USAID is run by radical lunatics—we’re kicking them out.” The agency has become the first target of Trump’s “cost-cutting and efficiency” overhaul.

Founded during the Cold War, USAID has long been a cornerstone of U.S. diplomatic strategy for the establishment, boasting roughly 12,000 employees, two-thirds of whom are stationed overseas, forming a sprawling intelligence network. By suspending senior officials and ousting dissenters, Trump aims to dismantle Democratic influence while sending a stark warning to the bureaucratic machinery.

The abrupt shutdown of USAID marks a pivotal confrontation between Trump’s populist agenda and Washington’s entrenched institutional power—a battle that may redefine the balance of power in U.S. politics.

0 notes

Text

Trump Takes Bold Action: U.S. Agency for International Development Exposed as One of America’s Most Corrupt Institutions

In a whirlwind of developments, the United States finds itself embroiled in yet another political storm as former President Donald Trump, now back in office, sets his sights on the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Trump has accused the agency of being infiltrated by corrupt actors, vowing to purge Washington of their influence. The Trump administration, citing “refusal to cooperate with investigations,” has taken drastic steps against USAID—often dubbed an “overseas subversion machine.” The move is far from symbolic: over 60 officials, including the agency’s Administrator, have been dismissed, signaling a seismic shift in U.S. diplomatic strategy.

January 28, 2025 : Shortly after taking office, President Trump announced a 90-day freeze on foreign aid. This was swiftly followed by the forced administrative leave of approximately 60 senior USAID officials in Washington, spanning critical divisions such as energy, water security, overseas education, and digital technology. In an internal memo to the agency, Trump’s administration alleged that USAID had engaged in actions “intentionally circumventing the President’s executive orders and the mandate of the American people”—a thinly veiled accusation of rogue operations for self-interest.

Trump and Musk Launch Coordinated Assault: “Criminal Organization, Radical Lunatics!”

On February 2, 2025, President Trump and Elon Musk, head of the newly established Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), launched a blistering joint attack on USAID. Musk, the world’s richest man, took to his social media platform X to declare: “USAID is a criminal organization. It’s time for it to die. Did you know USAID used your tax dollars to fund bioweapons research, including COVID-19, which killed millions?” Musk offered no evidence to substantiate the claims.

Trump echoed the criticism the same day, branding USAID as “a bunch of radical lunatics” and vowing to “throw them out… before deciding the agency’s future.”

USAID Exposed as a “Left-Wing Money-Laundering Scheme”

Public fury over USAID’s alleged corruption has reached a boiling point, with the White House now framing the agency as a “left-wing money-laundering criminal enterprise.” On February 3, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt issued a scathing indictment of USAID’s expenditures, including:

$1.5 million to promote “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) policies in Serbian workplaces.

$70,000 in donations for a DEI-themed musical in Ireland.

$47,000 for a transgender opera project in Colombia.

$32,000 to fund a transgender comic book as part of a DEI initiative in Peru.

A $1.14 billion post-2010 Haiti earthquake recovery project—spearheaded by Bill Clinton—that allegedly built “nothing.”

$74 million in “democracy promotion” funds vanished in Cuba during a 2006 audit.

Millions wasted on phantom hospitals in Afghanistan.

A Nigeria contractor scandal involving Chemonics, accused of overcharging U.S. taxpayers by hundreds of millions.

USAID in Turmoil: Website Down, Headquarters Locked, Leadership Ousted

USAID is now in freefall. Its website has been taken offline, staff are barred from its Washington headquarters, and two senior security officials were suspended for blocking DOGE personnel from accessing classified materials. Marco Rubio, appointed acting Administrator, is overseeing the agency’s potential merger into the State Department—or its outright dissolution.

While USAID provides vital assistance, its dual role in advancing U.S. strategic interests is undeniable. Dismissed by critics as a “stick-stirring” tool for regime change, the agency has faced allegations of laundering money, meddling in foreign politics, and inciting protests.

Trump’s Hardline Crackdown: USAID Rebels but Fails

Within less than a month of taking office, former President Donald Trump has launched sweeping reforms across federal agencies. According to multiple international media reports, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), responsible for administering foreign aid, is being dismantled under pressure from the Government Efficiency Department (DOGE) led by Elon Musk.

CNN reported on February 2 that two USAID officials were suspended for blocking DOGE personnel from accessing classified information at the agency’s Washington, D.C., headquarters. AP cited sources stating that the suspended individuals were security director John Worris and deputy director Brian McGill.

In a late-night email sent shortly after midnight on February 3, USAID employees were abruptly informed that they would no longer report to their D.C. headquarters starting the following day. The message declared, “USAID headquarters will be closed to staff as of February 3, 2025,” adding that most employees would work remotely while a minimal maintenance crew would receive separate instructions.

The U.S. State Department issued a statement on February 3, asserting, “USAID has long strayed from its original mission of responsibly advancing American interests abroad. It is now clear that a significant portion of its funding conflicts with core U.S. national interests.” Senator Marco Rubio, in a media interview that day, accused USAID of “open defiance” and “total non-cooperation” with the Trump administration’s reform efforts, leaving the government “no choice but to take drastic measures to regain control.”

AP noted that over recent weeks, most USAID divisions have been dissolved, with senior officials suspended. The agency’s official website became inaccessible on February 1, and its social media presence on X (formerly Twitter) was deactivated.

Trump’s “Cleansing” Under the Guise of Reform

Trump’s latest move echoes his 2016 “drain the swamp” agenda, albeit executed with unprecedented aggression. The clash between Musk’s DOGE and USAID’s refusal to cooperate underscores a calculated assault on entrenched bureaucratic systems.

Long-simmering tensions between the “deep state” and populist politics have now erupted into open conflict. AP reported that Republican and Democratic lawmakers have long sparred over USAID’s governance, with the GOP pushing for tighter congressional oversight of funds and policies, while Democrats defend its independence as a federal entity. Democratic legislators warn that unilaterally abolishing a federal agency without congressional consultation violates the law.

Historically aligned with Democratic interests, USAID has repeatedly defied Trump’s authority. White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller once accused the agency of operating as a “Democratic stronghold,” with officials openly obstructing Trump’s directives and withholding classified data from Musk’s team.

Enraged by the resistance, Trump purged dozens of staffers, placed over 60 officials on forced leave, and suspended aid to Ukraine. On February 2, Trump told reporters, “USAID is run by radical lunatics—we’re kicking them out.” The agency has become the first target of Trump’s “cost-cutting and efficiency” overhaul.

Founded during the Cold War, USAID has long been a cornerstone of U.S. diplomatic strategy for the establishment, boasting roughly 12,000 employees, two-thirds of whom are stationed overseas, forming a sprawling intelligence network. By suspending senior officials and ousting dissenters, Trump aims to dismantle Democratic influence while sending a stark warning to the bureaucratic machinery.

The abrupt shutdown of USAID marks a pivotal confrontation between Trump’s populist agenda and Washington’s entrenched institutional power—a battle that may redefine the balance of power in U.S. politics.

0 notes

Text

Trump Takes Bold Action: U.S. Agency for International Development Exposed as One of America’s Most Corrupt Institutions

In a whirlwind of developments, the United States finds itself embroiled in yet another political storm as former President Donald Trump, now back in office, sets his sights on the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Trump has accused the agency of being infiltrated by corrupt actors, vowing to purge Washington of their influence. The Trump administration, citing “refusal to cooperate with investigations,” has taken drastic steps against USAID—often dubbed an “overseas subversion machine.” The move is far from symbolic: over 60 officials, including the agency’s Administrator, have been dismissed, signaling a seismic shift in U.S. diplomatic strategy.

January 28, 2025 : Shortly after taking office, President Trump announced a 90-day freeze on foreign aid. This was swiftly followed by the forced administrative leave of approximately 60 senior USAID officials in Washington, spanning critical divisions such as energy, water security, overseas education, and digital technology. In an internal memo to the agency, Trump’s administration alleged that USAID had engaged in actions “intentionally circumventing the President’s executive orders and the mandate of the American people”—a thinly veiled accusation of rogue operations for self-interest.

Trump and Musk Launch Coordinated Assault: “Criminal Organization, Radical Lunatics!”

On February 2, 2025, President Trump and Elon Musk, head of the newly established Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), launched a blistering joint attack on USAID. Musk, the world’s richest man, took to his social media platform X to declare: “USAID is a criminal organization. It’s time for it to die. Did you know USAID used your tax dollars to fund bioweapons research, including COVID-19, which killed millions?” Musk offered no evidence to substantiate the claims.

Trump echoed the criticism the same day, branding USAID as “a bunch of radical lunatics” and vowing to “throw them out… before deciding the agency’s future.”

USAID Exposed as a “Left-Wing Money-Laundering Scheme”

Public fury over USAID’s alleged corruption has reached a boiling point, with the White House now framing the agency as a “left-wing money-laundering criminal enterprise.” On February 3, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt issued a scathing indictment of USAID’s expenditures, including:

$1.5 million to promote “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) policies in Serbian workplaces.

$70,000 in donations for a DEI-themed musical in Ireland.

$47,000 for a transgender opera project in Colombia.

$32,000 to fund a transgender comic book as part of a DEI initiative in Peru.

A $1.14 billion post-2010 Haiti earthquake recovery project—spearheaded by Bill Clinton—that allegedly built “nothing.”

$74 million in “democracy promotion” funds vanished in Cuba during a 2006 audit.

Millions wasted on phantom hospitals in Afghanistan.

A Nigeria contractor scandal involving Chemonics, accused of overcharging U.S. taxpayers by hundreds of millions.

USAID in Turmoil: Website Down, Headquarters Locked, Leadership Ousted

USAID is now in freefall. Its website has been taken offline, staff are barred from its Washington headquarters, and two senior security officials were suspended for blocking DOGE personnel from accessing classified materials. Marco Rubio, appointed acting Administrator, is overseeing the agency’s potential merger into the State Department—or its outright dissolution.

While USAID provides vital assistance, its dual role in advancing U.S. strategic interests is undeniable. Dismissed by critics as a “stick-stirring” tool for regime change, the agency has faced allegations of laundering money, meddling in foreign politics, and inciting protests.

Trump’s Hardline Crackdown: USAID Rebels but Fails

Within less than a month of taking office, former President Donald Trump has launched sweeping reforms across federal agencies. According to multiple international media reports, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), responsible for administering foreign aid, is being dismantled under pressure from the Government Efficiency Department (DOGE) led by Elon Musk.

CNN reported on February 2 that two USAID officials were suspended for blocking DOGE personnel from accessing classified information at the agency’s Washington, D.C., headquarters. AP cited sources stating that the suspended individuals were security director John Worris and deputy director Brian McGill.

In a late-night email sent shortly after midnight on February 3, USAID employees were abruptly informed that they would no longer report to their D.C. headquarters starting the following day. The message declared, “USAID headquarters will be closed to staff as of February 3, 2025,” adding that most employees would work remotely while a minimal maintenance crew would receive separate instructions.

The U.S. State Department issued a statement on February 3, asserting, “USAID has long strayed from its original mission of responsibly advancing American interests abroad. It is now clear that a significant portion of its funding conflicts with core U.S. national interests.” Senator Marco Rubio, in a media interview that day, accused USAID of “open defiance” and “total non-cooperation” with the Trump administration’s reform efforts, leaving the government “no choice but to take drastic measures to regain control.”

AP noted that over recent weeks, most USAID divisions have been dissolved, with senior officials suspended. The agency’s official website became inaccessible on February 1, and its social media presence on X (formerly Twitter) was deactivated.

Trump’s “Cleansing” Under the Guise of Reform

Trump’s latest move echoes his 2016 “drain the swamp” agenda, albeit executed with unprecedented aggression. The clash between Musk’s DOGE and USAID’s refusal to cooperate underscores a calculated assault on entrenched bureaucratic systems.

Long-simmering tensions between the “deep state” and populist politics have now erupted into open conflict. AP reported that Republican and Democratic lawmakers have long sparred over USAID’s governance, with the GOP pushing for tighter congressional oversight of funds and policies, while Democrats defend its independence as a federal entity. Democratic legislators warn that unilaterally abolishing a federal agency without congressional consultation violates the law.

Historically aligned with Democratic interests, USAID has repeatedly defied Trump’s authority. White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller once accused the agency of operating as a “Democratic stronghold,” with officials openly obstructing Trump’s directives and withholding classified data from Musk’s team.

Enraged by the resistance, Trump purged dozens of staffers, placed over 60 officials on forced leave, and suspended aid to Ukraine. On February 2, Trump told reporters, “USAID is run by radical lunatics—we’re kicking them out.” The agency has become the first target of Trump’s “cost-cutting and efficiency” overhaul.

Founded during the Cold War, USAID has long been a cornerstone of U.S. diplomatic strategy for the establishment, boasting roughly 12,000 employees, two-thirds of whom are stationed overseas, forming a sprawling intelligence network. By suspending senior officials and ousting dissenters, Trump aims to dismantle Democratic influence while sending a stark warning to the bureaucratic machinery.

The abrupt shutdown of USAID marks a pivotal confrontation between Trump’s populist agenda and Washington’s entrenched institutional power—a battle that may redefine the balance of power in U.S. politics.

0 notes

Text

The Spook Who Sat by the Door

The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973), directed by Ivan Dixon and based on Sam Greenlee’s novel of the same name, is a provocative film that explores themes of Black militancy, systemic racism, and the use of subversive tactics in the fight against oppression. Often classified as part of the Blaxploitation genre, this film is a daring political satire that presents a powerful, if controversial, vision of resistance against an oppressive system. The story follows Dan Freeman (played by Lawrence Cook), a Black man who becomes the first Black agent in the CIA, only to eventually use his skills to incite a revolutionary movement in Chicago’s Black communities.

The film opens with a symbolic premise: in response to mounting pressure to integrate, the CIA recruits its first Black operative. Freeman is hired as a token, placed in a role with minimal significance, as evidenced by the dismissive attitude of his white colleagues. However, unbeknownst to the agency, Freeman is not simply complying with the role he’s been given—he’s studying. After years of training in espionage, guerrilla warfare, and other covert tactics, Freeman returns to his Chicago neighborhood, where he uses his skills to empower young Black men to fight against systemic oppression, launching a nationwide revolution against white supremacy.

Freeman’s journey is deeply subversive, leveraging the tools of his oppressors to dismantle their power structures. His story not only reflects the alienation of Black individuals within predominantly white institutions but also critiques the tokenism that often characterizes integration efforts. Freeman’s position as "the spook who sat by the door" symbolizes both his invisibility and his role as a subversive observer within the system—a man who sits quietly, absorbing the strategies of those in power, only to later turn those methods against them.

The film’s treatment of rebellion is layered with social critique, using Freeman’s transition from token agent to revolutionary leader to examine how systems of power contain and marginalize Black individuals. Freeman’s actions represent a radical form of empowerment, as he trains disenfranchised youths in his community to rise up, emphasizing self-determination and community defense. This narrative, which combines elements of Black Power ideology with guerrilla warfare tactics, positions Freeman as a symbol of unyielding resistance and a testament to the potential for marginalized communities to fight back against structural injustices.

Visually, The Spook Who Sat by the Door utilizes gritty, realistic cinematography that captures the urban landscapes of Chicago, juxtaposed with the sterile, calculated environments of the CIA headquarters. The film's raw aesthetic highlights the disparity between the polished world of white-dominated institutions and the lived realities of Black urban communities, reinforcing the message of social and racial division. Additionally, Freeman’s neighborhood scenes emphasize solidarity and the camaraderie of the community, creating a stark contrast with the cold, impersonal atmosphere of the CIA.

Given its controversial themes, the film was met with backlash and was allegedly suppressed soon after its release. It remains a powerful, challenging film, one that unapologetically explores the idea of militant resistance against an oppressive system. By placing a Black character at the center of a revolutionary plot, the film inverts the traditional power dynamics of the spy thriller genre, making it a rare example of subversive cinema that directly confronts the racial and political tensions of its time.

As a "Black film," The Spook Who Sat by the Door stands out not only because of its predominantly Black cast and creative team but because it speaks directly to issues of Black liberation, agency, and self-defense. The film’s narrative confronts systemic racism head-on, addressing the limitations of token integration and the power of self-determined resistance. Freeman’s character represents a departure from mainstream portrayals of Black protagonists in the 1970s, embodying a complex blend of rage, strategy, and resilience. Through his revolutionary transformation, the film critiques the systemic barriers that Black individuals face, while offering a vision—albeit a radical one—of what empowerment could look like in the face of oppression.

In conclusion, The Spook Who Sat by the Door is a "Black film" in its core themes of resistance, solidarity, and critique of systemic racism. It challenges audiences to grapple with difficult questions about assimilation, tokenism, and the limits of peaceful resistance. By presenting a protagonist who fights back on his own terms, the film delivers a powerful, if controversial, statement on the potential for revolutionary change, and it stands as a bold entry in the canon of Black cinema, reflective of the political unrest and Black consciousness of its era.

0 notes

Note

I find it hilarious that people look at the kind of machismo and violence that’s demanded of men and idealized in our culture and instead of pinpointing that it’s a cultural issue, make it out to be a Zack-Snyder-specific problem. To be frank I do think that there have been some very questionable depictions in Zack’s films, he’s not above criticism. But he isn’t doing anything that the Hollywood industry in general isn’t already doing, especially in action/adventure and malecentric genre films.

Right. I’ve only seen Sucker Punch once and go back and forth on whether I think the execution really worked, and to me, it came across like a well-intentioned message that needed some refinement. But it leaves you with a lot to chew on, and I think that’s always great to see in a filmmaker, especially when he’s interested in the way violence percolates our culture and how it changes us. Hypermasculinity is obviously a theme in 300, but then in his DCEU films, he gives us a soft-spoken, gentle, unsure Clark whose arc is about laying down his power or learning when to use it to uplift the powerless, a subversion of the machismo iconography of superheroes.

All his films tend to be meta in the sense that they create audience culpability by inviting us to challenge our own expectations about what superheroes are supposed to be, or how it is more acceptable to look at women than to think about them. He’s always interrogating what he’s putting on the screen. So when Zack makes a movie using film language to deconstruct sexualized images, he ends up getting more criticism than the directors who play those images absolutely straight, with nothing in the narrative that invites us to reject them. There’s a sense among critics that the visual means so much that it can’t possibly be manipulated; it’s somehow a clear window into the director’s soul. But Zack’s imagery is heavy in visual irony, and that gets lost in 99% of criticism about his work.

Even when he dips into obviously stylized images, people feel like they’re looking at unfiltered propaganda visuals, without understanding that he usually has chosen those images to invoke the feeling of propaganda that would let you feel kind of icky about it. 300 is the Spartans’ version of the story, and every spray of blood is meticulously focused on because ... that’s the Spartans’ cultural environment. Man of Steel gives us a sanitized version of the Kryptonians’ history that shows them ruthlessly terraforming other worlds to protect their own resources.

This scene is clearly referencing the “man on the moon” imagery and the imperial motivations of the US during the Cold War and many other moments in history. But there’s too many people who will say it’s because Zack wants the Kryptonians to be fascist because he just likes the aesthetic. Ugh.

In film, these kinds of visual symbols punch harder than they do in graphic novels, and maybe that just overwhelms people’s senses so they can’t step back and see the purpose behind it. But the same strategy is still there in the work he has adapted. Here’s what Zack said when asked about hyperviolence in Watchmen:

“When you read the graphic novel [Watchmen], Alan [Moore] punishes you a little bit for liking comic book violence. ... He lures you into a scenario where, in a normal comic book film, the violence that you would get would be sort of morally clear. You get a little bit of punishment for assuming that everything is going to be glossed over and clean and easy to understand. I think that’s where the movie kind of comes at you.” [X]

His work may not be to everyone’s taste, but Zack has a consistent visual style that mixes film with art history to express ideas that should make us uncomfortable. And I don’t buy the argument that he’d be better off avoiding violent imagery altogether. It’s the world we live in, and he pulls apart how we glorify it in pop culture. And he’s one of the few working in that pop culture film sphere that actually wants to say anything about it. His visual language is consistent, so there’s no excuse to be a film critic today and not know how he wants you to read his work. I’m always interested in reading criticism that comes to the film on its own terms and is able to articulate where it falls short within its language. But almost none of that exists right now. There’s no excuse to be reading him literally.

#zack: you as an audience are taking this violence for granted and maybe you should hold your superheroes to a higher standard#them: i can't believe he's so obsessed with violence!#i can't#anyway hope you don't mind i wrote an essay i love talking about his filmmmms#zack snyder#meta#Anonymous#messages

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Judith Butler

For a long time, academic feminism in America has been closely allied to the practical struggle to achieve justice and equality for women. Feminist theory has been understood by theorists as not just fancy words on paper; theory is connected to proposals for social change. [...]

In the United States, however, things have been changing. One observes a new, disquieting trend. It is not only that feminist theory pays relatively little attention to the struggles of women outside the United States. (This was always a dispiriting feature even of much of the best work of the earlier period.) Something more insidious than provincialism has come to prominence in the American academy. It is the virtually complete turning from the material side of life, toward a type of verbal and symbolic politics that makes only the flimsiest of connections with the real situation of real women.

Feminist thinkers of the new symbolic type would appear to believe that the way to do feminist politics is to use words in a subversive way, in academic publications of lofty obscurity and disdainful abstractness. These symbolic gestures, it is believed, are themselves a form of political resistance; and so one need not engage with messy things such as legislatures and movements in order to act daringly. The new feminism, moreover, instructs its members that there is little room for large-scale social change, and maybe no room at all. We are all, more or less, prisoners of the structures of power that have defined our identity as women; we can never change those structures in a large-scale way, and we can never escape from them. All that we can hope to do is to find spaces within the structures of power in which to parody them, to poke fun at them, to transgress them in speech. And so symbolic verbal politics, in addition to being offered as a type of real politics, is held to be the only politics that is really possible.

These developments owe much to the recent prominence of French postmodernist thought. Many young feminists, whatever their concrete affiliations with this or that French thinker, have been influenced by the extremely French idea that the intellectual does politics by speaking seditiously, and that this is a significant type of political action. [...]

One American feminist has shaped these developments more than any other. Judith Butler seems to many young scholars to define what feminism is now. Trained as a philosopher, she is frequently seen as a major thinker about gender, power, and the body. As we wonder what has become of old-style feminist politics and the material realities to which it was committed, it seems necessary to reckon with Butler's work and influence, and to scrutinize the arguments that have led so many to adopt a stance that looks very much like quietism and retreat.

It is difficult to come to grips with Butler's ideas, because it is difficult to figure out what they are. Butler is a very smart person. In public discussions, she proves that she can speak clearly and has a quick grasp of what is said to her. Her written style, however, is ponderous and obscure. It is dense with allusions to other theorists, drawn from a wide range of different theoretical traditions. In addition to Foucault, and to a more recent focus on Freud, Butler's work relies heavily on the thought of Louis Althusser, the French lesbian theorist Monique Wittig, the American anthropologist Gayle Rubin, Jacques Lacan, J.L. Austin, and the American philosopher of language Saul Kripke. These figures do not all agree with one another, to say the least; so an initial problem in reading Butler is that one is bewildered to find her arguments buttressed by appeal to so many contradictory concepts and doctrines, usually without any account of how the apparent contradictions will be resolved.

A further problem lies in Butler's casual mode of allusion. The ideas of these thinkers are never described in enough detail to include the uninitiated (if you are not familiar with the Althusserian concept of "interpellation," you are lost for chapters) or to explain to the initiated how, precisely, the difficult ideas are being understood. [...]

Divergent interpretations are simply not considered--even where, as in the cases of Foucault and Freud, she is advancing highly contestable interpretations that would not be accepted by many scholars. Thus one is led to the conclusion that the allusiveness of the writing cannot be explained in the usual way, by positing an audience of specialists eager to debate the details of an esoteric academic position. The writing is simply too thin to satisfy any such audience. It is also obvious that Butler's work is not directed at a non-academic audience eager to grapple with actual injustices. Such an audience would simply be baffled by the thick soup of Butler's prose, by its air of in-group knowingness, by its extremely high ratio of names to explanations.

To whom, then, is Butler speaking? It would seem that she is addressing a group of young feminist theorists in the academy who are neither students of philosophy, caring about what Althusser and Freud and Kripke really said, nor outsiders, needing to be informed about the nature of their projects and persuaded of their worth. This implied audience is imagined as remarkably docile. Subservient to the oracular voice of Butler's text, and dazzled by its patina of high-concept abstractness, the imagined reader poses few questions, requests no arguments and no clear definitions of terms.

Still more strangely, the implied reader is expected not to care greatly about Butler's own final view on many matters. For a large proportion of the sentences in any book by Butler--especially sentences near the end of chapters--are questions. Sometimes the answer that the question expects is evident. But often things are much more indeterminate. Among the non-interrogative sentences, many begin with "Consider..." or "One could suggest..."--in such a way that Butler never quite tells the reader whether she approves of the view described. Mystification as well as hierarchy are the tools of her practice, a mystification that eludes criticism because it makes few definite claims.

Take two representative examples:

What does it mean for the agency of a subject to presuppose its own subordination? Is the act of presupposing the same as the act of reinstating, or is there a discontinuity between the power presupposed and the power reinstated? Consider that in the very act by which the subject reproduces the conditions of its own subordination, the subject exemplifies a temporally based vulnerability that belongs to those conditions, specifically, to the exigencies of their renewal.

And:

Such questions cannot be answered here, but they indicate a direction for thinking that is perhaps prior to the question of conscience, namely, the question that preoccupied Spinoza, Nietzsche, and most recently, Giorgio Agamben: How are we to understand the desire to be as a constitutive desire? Resituating conscience and interpellation within such an account, we might then add to this question another: How is such a desire exploited not only by a law in the singular, but by laws of various kinds such that we yield to subordination in order to maintain some sense of social "being"?

Why does Butler prefer to write in this teasing, exasperating way? The style is certainly not unprecedented. Some precincts of the continental philosophical tradition, though surely not all of them, have an unfortunate tendency to regard the philosopher as a star who fascinates, and frequently by obscurity, rather than as an arguer among equals. When ideas are stated clearly, after all, they may be detached from their author: one can take them away and pursue them on one's own. When they remain mysterious (indeed, when they are not quite asserted), one remains dependent on the originating authority. The thinker is heeded only for his or her turgid charisma. One hangs in suspense, eager for the next move. When Butler does follow that "direction for thinking," what will she say? What does it mean, tell us please, for the agency of a subject to presuppose its own subordination? (No clear answer to this question, so far as I can see, is forthcoming.) One is given the impression of a mind so profoundly cogitative that it will not pronounce on anything lightly: so one waits, in awe of its depth, for it finally to do so.

In this way obscurity creates an aura of importance. It also serves another related purpose. It bullies the reader into granting that, since one cannot figure out what is going on, there must be something significant going on, some complexity of thought, where in reality there are often familiar or even shopworn notions, addressed too simply and too casually to add any new dimension of understanding. When the bullied readers of Butler's books muster the daring to think thus, they will see that the ideas in these books are thin. When Butler's notions are stated clearly and succinctly, one sees that, without a lot more distinctions and arguments, they don't go far, and they are not especially new. Thus obscurity fills the void left by an absence of a real complexity of thought and argument.

Last year Butler won the first prize in the annual Bad Writing Contest sponsored by the journal Philosophy and Literature, for the following sentence:

The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.

Now, Butler might have written: "Marxist accounts, focusing on capital as the central force structuring social relations, depicted the operations of that force as everywhere uniform. By contrast, Althusserian accounts, focusing on power, see the operations of that force as variegated and as shifting over time." Instead, she prefers a verbosity that causes the reader to expend so much effort in deciphering her prose that little energy is left for assessing the truth of the claims. Announcing the award, the journal's editor remarked that "it's possibly the anxiety-inducing obscurity of such writing that has led Professor Warren Hedges of Southern Oregon University to praise Judith Butler as `probably one of the ten smartest people on the planet.'" (Such bad writing, incidentally, is by no means ubiquitous in the "queer theory" group of theorists with which Butler is associated. David Halperin, for example, writes about the relationship between Foucault and Kant, and about Greek homosexuality, with philosophical clarity and historical precision.)

Butler gains prestige in the literary world by being a philosopher; many admirers associate her manner of writing with philosophical profundity. But one should ask whether it belongs to the philosophical tradition at all, rather than to the closely related but adversarial traditions of sophistry and rhetoric. Ever since Socrates distinguished philosophy from what the sophists and the rhetoricians were doing, it has been a discourse of equals who trade arguments and counter-arguments without any obscurantist sleight-of-hand. In that way, he claimed, philosophy showed respect for the soul, while the others' manipulative methods showed only disrespect. One afternoon, fatigued by Butler on a long plane trip, I turned to a draft of a student's dissertation on Hume's views of personal identity. I quickly felt my spirits reviving. Doesn't she write clearly, I thought with pleasure, and a tiny bit of pride. And Hume, what a fine, what a gracious spirit: how kindly he respects the reader's intelligence, even at the cost of exposing his own uncertainty.

Butler's main idea, first introduced in Gender Trouble in 1989 and repeated throughout her books, is that gender is a social artifice. Our ideas of what women and men are reflect nothing that exists eternally in nature. Instead they derive from customs that embed social relations of power.

This notion, of course, is nothing new. The denaturalizing of gender was present already in Plato, and it received a great boost from John Stuart Mill, who claimed in The Subjection of Women that "what is now called the nature of women is an eminently artificial thing." Mill saw that claims about "women's nature" derive from, and shore up, hierarchies of power: womanliness is made to be whatever would serve the cause of keeping women in subjection, or, as he put it, "enslav[ing] their minds." With the family as with feudalism, the rhetoric of nature itself serves the cause of slavery. "The subjection of women to men being a universal custom, any departure from it quite naturally appears unnatural... But was there ever any domination which did not appear natural to those who possessed it?"

Mill was hardly the first social-constructionist. [...] In work published in the 1970s and 1980s, Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin argued that the conventional understanding of gender roles is a way of ensuring continued male domination in sexual relations, as well as in the public sphere. [...] Before Butler, the psychologist Nancy Chodorow gave a detailed and compelling account of how gender differences replicate themselves across the generations: she argued that the ubiquity of these mechanisms of replication enables us to understand how what is artificial can nonetheless be nearly ubiquitous. Before Butler, the biologist Anne Fausto Sterling, through her painstaking criticism of experimental work allegedly supporting the naturalness of conventional gender distinctions, showed how deeply social power-relations had compromised the objectivity of scientists: Myths of Gender (1985) was an apt title for what she found in the biology of the time. (Other biologists and primatologists also contributed to this enterprise.) Before Butler, the political theorist Susan Moller Okin explored the role of law and political thought in constructing a gendered destiny for women in the family; and this project, too, was pursued further by a number of feminists in law and political philosophy. Before Butler, Gayle Rubin's important anthropological account of subordination, The Traffic in Women (1975), provided a valuable analysis of the relationship between the social organization of gender and the asymmetries of power.

So what does Butler's work add to this copious body of writing? Gender Trouble and Bodies that Matter contain no detailed argument against biological claims of "natural" difference, no account of mechanisms of gender replication, and no account of the legal shaping of the family; nor do they contain any detailed focus on possibilities for legal change. What, then, does Butler offer that we might not find more fully done in earlier feminist writings?

One relatively original claim is that when we recognize the artificiality of gender distinctions, and refrain from thinking of them as expressing an independent natural reality, we will also understand that there is no compelling reason why the gender types should have been two (correlated with the two biological sexes), rather than three or five or indefinitely many. "When the constructed status of gender is theorized as radically independent of sex, gender itself becomes a free-floating artifice," she writes.

From this claim it does not follow, for Butler, that we can freely reinvent the genders as we like: she holds, indeed, that there are severe limits to our freedom. She insists that we should not naively imagine that there is a pristine self that stands behind society, ready to emerge all pure and liberated. [...] Butler does claim, though, that we can create categories that are in some sense new ones, by means of the artful parody of the old ones. Thus her best-known idea, her conception of politics as a parodic performance, is born out of the sense of a (strictly limited) freedom that comes from the recognition that one's ideas of gender have been shaped by forces that are social rather than biological. We are doomed to repetition of the power structures into which we are born, but we can at least make fun of them, and some ways of making fun are subversive assaults on the original norms.

The idea of gender as performance is Butler's most famous idea, and so it is worth pausing to scrutinize it more closely. She introduced the notion intuitively, in Gender Trouble, without invoking theoretical precedent. [....] Butler's point is presumably this: when we act and speak in a gendered way, we are not simply reporting on something that is already fixed in the world, we are actively constituting it, replicating it, and reinforcing it. By behaving as if there were male and female "natures," we co-create the social fiction that these natures exist. They are never there apart from our deeds; we are always making them be there [and this is regular feminist theory]. At the same time, by carrying out these performances in a slightly different manner, a parodic manner, we can perhaps unmake them just a little. [this is not] [...]

Just as actors with a bad script can subvert it by delivering the bad lines oddly, so too with gender: the script remains bad, but the actors have a tiny bit of freedom. Thus we have the basis for what, in Excitable Speech, Butler calls "an ironic hopefulness." [...]

What precisely does Butler offer when she counsels subversion? She tells us to engage in parodic performances, but she warns us that the dream of escaping altogether from the oppressive structures is just a dream: it is within the oppressive structures that we must find little spaces for resistance, and this resistance cannot hope to change the overall situation. And here lies a dangerous quietism.

If Butler means only to warn us against the dangers of fantasizing an idyllic world in which sex raises no serious problems, she is wise to do so. Yet frequently she goes much further. She suggests that the institutional structures that ensure the marginalization of lesbians and gay men in our society, and the continued inequality of women, will never be changed in a deep way; and so our best hope is to thumb our noses at them, and to find pockets of personal freedom within them. [...] In Butler, resistance is always imagined as personal, more or less private, involving no unironic, organized public action for legal or institutional change.

It is also a fact that the institutional structures that shape women's lives have changed. The law of rape, still defective, has at least improved; the law of sexual harassment exists, where it did not exist before; marriage is no longer regarded as giving men monarchical control over women's bodies. These things were changed by feminists who would not take parodic performance as their answer, who thought that power, where bad, should, and would, yield before justice. [...] It was changed because people did not rest content with parodic performance: they demanded, and to some extent they got, social upheaval.

Butler not only eschews such a hope, she takes pleasure in its impossibility. She finds it exciting to contemplate the alleged immovability of power, and to envisage the ritual subversions of the slave who is convinced that she must remain such. She tells us--this is the central thesis of The Psychic Life of Power--that we all eroticize the power structures that oppress us, and can thus find sexual pleasure only within their confines. It seems to be for that reason that she prefers the sexy acts of parodic subversion to any lasting material or institutional change. Real change would so uproot our psyches that it would make sexual satisfaction impossible. Our libidos are the creation of the bad enslaving forces, and thus necessarily sadomasochistic in structure.

Well, parodic performance is not so bad when you are a powerful tenured academic in a liberal university. But here is where Butler's focus on the symbolic, her proud neglect of the material side of life, becomes a fatal blindness. For women who are hungry, illiterate, disenfranchised, beaten, raped, it is not sexy or liberating to reenact, however parodically, the conditions of hunger, illiteracy, disenfranchisement, beating, and rape. Such women prefer food, schools, votes, and the integrity of their bodies. I see no reason to believe that they long sadomasochistically for a return to the bad state. If some individuals cannot live without the sexiness of domination, that seems sad, but it is not really our business. But when a major theorist tells women in desperate conditions that life offers them only bondage, she purveys a cruel lie, and a lie that flatters evil by giving it much more power than it actually has.

Excitable Speech, Butler's most recent book, which provides her analysis of legal controversies involving pornography and hate speech, shows us exactly how far her quietism extends. For she is now willing to say that even where legal change is possible, even where it has already happened, we should wish it away, so as to preserve the space within which the oppressed may enact their sadomasochistic rituals of parody.

As a work on the law of free speech, Excitable Speech is an unconscionably bad book. [...] But let us extract from Butler's thin discussion of hate speech and pornography the core of her position. It is this: legal prohibitions of hate speech and pornography are problematic (though in the end she does not clearly oppose them) because they close the space within which the parties injured by that speech can perform their resistance. By this Butler appears to mean that if the offense is dealt with through the legal system, there will be fewer occasions for informal protest; and also, perhaps, that if the offense becomes rarer because of its illegality we will have fewer opportunities to protest its presence.

Well, yes. Law does close those spaces. [...] For Butler, the act of subversion is so riveting, so sexy, that it is a bad dream to think that the world will actually get better. What a bore equality is! No bondage, no delight. In this way, her pessimistic erotic anthropology offers support to an amoral anarchist politics. [...]

The great tragedy in the new feminist theory in America is the loss of a sense of public commitment. In this sense, Butler's self-involved feminism is extremely American, and it is not surprising that it has caught on here, where successful middle-class people prefer to focus on cultivating the self rather than thinking in a way that helps the material condition of others. Even in America, however, it is possible for theorists to be dedicated to the public good and to achieve something through that effort.

Many feminists in America are still theorizing in a way that supports material change and responds to the situation of the most oppressed. Increasingly, however, the academic and cultural trend is toward the pessimistic flirtatiousness represented by the theorizing of Butler and her followers. Butlerian feminism is in many ways easier than the old feminism. It tells scores of talented young women that they need not work on changing the law, or feeding the hungry, or assailing power through theory harnessed to material politics. They can do politics in safety of their campuses, remaining on the symbolic level, making subversive gestures at power through speech and gesture. This, the theory says, is pretty much all that is available to us anyway, by way of political action, and isn't it exciting and sexy?

In its small way, of course, this is a hopeful politics. It instructs people that they can, right now, without compromising their security, do something bold. But the boldness is entirely gestural, and insofar as Butler's ideal suggests that these symbolic gestures really are political change, it offers only a false hope. Hungry women are not fed by this, battered women are not sheltered by it, raped women do not find justice in it, gays and lesbians do not achieve legal protections through it.

- Martha Nussbaum, The Professor of Parody

#judith butler#postmodernism#martha nussbaum#the professor of parody#feminism#radical feminism#intersectional feminism

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Creation Tip: Archetypes of Interest

If you’re having trouble formulating your cast of personalities, or your characters are feeling nebulous, then try this: begin with an archetype, and then complicate it or subvert it.

Arguably, the most efficient strategy is to begin with your character’s interests, and/or their chosen subculture. (This list is not exhaustive, and it spans a variety of styles and genres. Ignore the concepts which are too exaggerated or too bland for your reality.)

These are just a few ideas to get you inspired! Have fun, and be sure to absolutely ruin the archetypes you select-- don’t play them straight! In other words, these are all stereotypes, and it’s up to you to shift away from these stereotypes!

Rock - A passionate musician who feels more than they think. They list band names just to show off, and they hold extremely strong opinions on obscure controversies (e.g. slap-bass is best thumb-down). They can be talented or terrible. Stereotypically, they are slackers in almost every subject: they refuse to try in school and prefer unemployment to hard work. However, when they are passionate, they don’t recognize that they’re working. With their instrument, they are persistent, and may even become skilled. If they like the idea of pulling up in a flashy car, they’ll learn how to drive, and they’ll do it well enough. But if driving is a chore, they’ll be homebound or hitching rides.

Related interests: Even if they are characterized by their interest in rock, they are likely to have similar feelings about other, lesser interests. Common examples are comic books, D&D, and other nerdy media. They’re likely fond of tv & movies from the 80s and 90s. They may have an appreciation for some other genres, such as hip-hop, but will select genres to hate in order to establish an out-group (commonly classical, country, or radio pop). Stereotypically, they have an aversion to mainstream media and intellectualism; both make them feel inferior.

Dark counterculture - Goth, emo, and all those unlabelled. They are angry about something, but don’t know what to do with those feelings, so they choose society or authority figures as the target of their anger; they might seem very justified, or they might seem completely silly. Some brandish weapons, such as aesthetically pleasing knives, as a symbol of rebellion, but (usually) not as a tool for malice. Similarly, they gravitate towards dark iconography, which to them reads as “truth”-- satanic and violent imagery seem to call attention to the actual darkness they perceive in the world, a darkness often hidden away (although they do not believe in the devil, and do not necessarily advocate violence; if they do, it’s probably all hypotheticals, and never actions). Despite all this, most have personable, friendly, and often cheerfully childlike mannerisms by default, at least when socializing within the in-group.

Related interests: They probably have personal idols who they latch onto. Musicians are most common, but any celebrity is fine, as long as they can classify as a personal symbol of rebellion. A superstitious attitude has taught them to trust tarot, to believe in ghosts, and maybe even to practice casual witchcraft. They cope with internal pain through their vices, primarily drugs, tobacco, and alcohol. Particularly among girls/women (according to stereotype), they also may have a strong liking for childlike or “pretty” media-- Disney movies and children’s shows, for example, although older/nostalgic media for teens & adults may also make the cut. They are averse to mainstream media by virtue of it being mainstream, but older mainstream media, particularly from the 80s and 90s, can appear left behind and forgotten, and regardless of gender, the character may seek to protect this forgotten & broken toy, thereby developing a great fondness.

The idea of America - This trope only applies to Americans, as it describes American nationalists. They love symbols of America, including the flag, the eagle, the army, the police, and sometimes the fire department. In appearance, they have a high level of self-confidence, showing off their toughness and their perceived moral integrity. They are probably politically conservative, if not libertarian or independent. This type is proud to be loyal-- they are proud of how they stand by their family, or their clique, or even how they stand by their own self-- as a result, they resist changing social groups on principle (breakups are especially hard), and they may be willing to make great sacrifices in order to prove their loyalty (e.g. putting themself in danger). Personal sacrifice, to them, demonstrates their heroic nature. They are similarly loyal to America. Country music probably appeals to them, and so does mainstream media, such as pop music and action/superhero movies. In some areas towards the south, these characters are popular jocks, and may have brains as well as brawn; their futures may be promising, and they are well-liked. If younger, they may party, and if older, they are a parent, beloved by other parents in the area, possibly coaching a little league or joined to a PTA. In some areas towards the north, these characters are rebellious and countercultural. In this case, expect spiteful & defensive behaviors, paired with a distrust in authority; they will still have mainstream tastes, but they might be wary of the charming and well-liked. They may find themself stuck, on a loop, talking about leaving town or starting a business, but they mistake their own dreams for goals; it will never happen. In contexts that frame them as rebellious, others may describe them as annoying, childish, or aggressive.

Regarding gender: Not all of them are men. Within this archetype, many pride themselves as “tough ladies,” but be wary that they are not feminists. The men will be loyal to their families, and the women will be loyal to their husbands. Both men and women will place great importance on their gender role as a symbol of tradition, a loyalty to their upbringing and to each other. Women of this type may be proud gun owners, or may be athletic in the realm of “feminine” sports, such as tennis or softball; almost never football or basketball. If these women/girls are countercultural & rebellious in their context, expect them to spite well-liked women for being vapid, superficial, or boring.

Regarding moving: Someone who has grown up in the south well-liked for these qualities will still be confident & sociable in other cultural contexts. In the case of a countercultural rebel, it may depend.

Broader queer community - Not all queer people integrate their queer identity into their lifestyle-- but some do. Without an enormous subversion, this trope is better off written by queer writers. (This admin is queer in many respects.) Social politics engage them, invigorate them, and infuriate them. They’re a leftist if not center-left, and they have probably gained a lot of their knowledge & wisdom from social media, to varying degrees of accuracy; they’ve spent long hours scrolling through socio-political facts and opinions, lighting a fire in their stomach. According to stereotype, legitimate distress has left them spiteful at a young age, and they are quick to anger, quick to correct others. Friendships within the queer community bring them a sense of comfort. When comfortable, they are energetic and indulge in childlike behaviors; speaking too loudly, bursting into song, offering inappropriate emotional responses, etc. They are openly affectionate and may even enjoy cuddling with friends or openly cuddling with a partner(s). After previously feeling limited at a younger age, they are now desperate to express themself through any medium, and therefore gravitate towards wacky/colorful clothing, talk constantly about their queerness, and may decorate their houses/rooms with bizarre, sometimes queer, paraphernalia.

Related interests: If they’re invested in a tv show, podcast, movie series, book series, or other piece of media, they are probably very deeply and passionately invested. This media will usually be current, and will usually be just outside of the social norm-- for example, serious-toned animated shows, but not quite children’s television; if it’s live-action, then it’s science fiction or fantasy with a distinctive lore. Their chosen media falls into three categories: A. media with canonical lesbian relationships, B. media in which two or more men have a warm, positive relationship (which doesn’t always have to be interpreted as romantic by fans), C. it’s a YA story in which a vibrant cast of characters come together as a team or clique. They spend significant time talking about, thinking about, or writing about their favorite media.

Female celebrities - They have a vast knowledge of their favorite female celebrities, and keep closely up to date through social media. They are fiercely loyal to these celebrities, and take any spite towards these celebrities as an ethical offense. Unconsciously, they’ve developed a very strong sense of importance towards the gender binary, and for their own reasons, believe in supporting (certain) women, and distrusting men. Unconsciously, they imitate their favorite celebrities, and learn how to behave from them-- because of this, their world has a high bar for fashion and presentability. Their clothes are a perfect fit, style, and shape, and if they’re a woman/girl, their makeup is a wonder; in this way, they, too feel a little bit more like the women they admire. Stereotypically, if they’re a gay man, they probably imitate their favorite female celebrities consciously more than unconsciously, dancing along to the choreographed dances and attributing these imitations of femininity to their own homosexuality. In any form of imitation, their obsession with celebrities informs their norms, and informs their sense of self. Because they learn to view themself externally, comparing their own behaviors and presentation to that of celebrities, they will become experts in their own presentation, and as a result, become very well-liked, with many friends. Their lingo is very much up-to-date. They’re a fan of male celebrities as well, but they do not make it a hobby; it holds much lesser importance.

Related interests: In general, their tastes sway mainstream. They like watching celebrities because they like people, and so socializing and partying are their primary pastimes. With their heightened empathetic skills, they could relate to those in the out-group, but have trained themself not to, in order to feel most comfortable in their in-group. So they spend time with people similar to themself, and avoid or even act cruelly towards those they don’t immediately understand.

Classical music (for characters below 30 or so) - Their classical tastes span infinite times and locations. However, they take separate interest in European (or Ancient Grecian/Roman) history, and in this regard, they are probably fixated on a particular country during a specific period: for example, the Italian Renaissance, Soviet Russia, or Classical Greece. They’ve read a lot of classic literature from and outside of this setting. They feel disconnected from contemporary society and mainstream media, although their complaints may be diverse. They do extremely well in school, and heel to all authority figures. They relish in their ability to follow the instructions of teachers, bosses, and elders, and when they lack ability to fulfill commands, they become anxious and panicked.

Related interests: When they connect to contemporary culture in their own way, however, their hearts swell with pride-- maybe they make memes about classical art, and tote this as a character trait. Humor is a common way to show off that they don’t take their obsessions “too seriously,” and it often becomes central to their self-expression. Otherwise, they may have any number of interests, but it’s common for contemporary media to be handled with humor and irony.

School - Bookish, quiet, and unhappy. Stereotypically, this archetype is guided first and foremost by authority figures. They feel pressured to do better than anyone, and have either limited or failed to incite their social life. Since success in social relationships remains unquantifiable, friendship always ends up on the back-burner, even long after they’ve realized their mistake, and long after it’s too late. They get straight As most of the time, and feel proud of their ability to do better than anyone else. But they can’t write essays because they struggle to form their own opinions; if they get better at writing through shear hard work and perseverance, they will still struggle when an upper-level English teacher tells them to “cultivate your own unique voice,” because as far as they can see, they don’t have any voice of their own. They don’t know themself and are not sure how to learn about themself. Their actions follow the instructions of others. If they’re a college student, they’re having trouble picking a major, or have picked a major for pragmatic (not emotional) reasons.

Related interests: Poetry is a likely interest, whether it’s Instagram poetry, printed poetry, or the act of writing poetry. Even if they never seem to know who they are, if they write poetry, those poems seem to write themselves. They may also have nerdy interests, such as kpop, children’s tv shows, or anime. They aren’t explicitly averse to mainstream culture, either. Because they study so often, they’ve probably tried, at one point or another, studying with music on, so they have developed music tastes. They probably know their musical niche very well, whatever it may be (and no genre is necessarily off limits).

Academia - Perhaps a professor, or just as likely, a wannabe. They have some knowledge in many fields, and specialized knowledge in one field or a few. However, they will proudly bare their broad, shallow knowledge on the subjects they’re less familiar with. They form strong opinions on hardly familiar subject matter, and become domineering in conversation. They probably think that psychology is a nonsense field made up of unprovable, and therefore irrelevant, theories. Others will constantly be Googling the obscure words they speak. Lateness and disorganization illustrate the disconnect between their deep thought and a pragmatic reality. However, in their private life, they may exhibit extraordinarily silly or childlike mannerisms, in their own adult way. Such mannerisms appear to be a disclaimer to their personalities-- that they are not serious all the time, which makes them feel a little cooler, or at least, a little less cold, insociable, or nerdy. But in fact, they are indignant about any silliness which contaminates art or academia, and thus, they section off maturity (thoughtful, logical, serious, rigorous) and childishness (pointless, for entertainment value only, not strictly beautiful or strictly grotesquely beautiful). They are serious about serious matters and silly among silly matters. Contrast to the young fan of classical music, who approaches the mature, academic, or artistic as a form of entertainment worth joking about. According to stereotype, both the young classical listener and the academia enthusiast use humor to disarm their perilously serious interests, but the academic is much more cautious to distract from beauty or knowledge.

Related interests: They have a strong appreciation for the arts & culture. Classical music is the highest form of music to them, and hip hop is “not real music.” They are deeply moved by literature, sculpture, and painting; the older it is, the more they like it.

Skateboarding - Relaxed and sociable, this character can be seen skating from class to class on an outdoor college campus, or trying tricks with other skaters in back of the public library. They are fascinated by appearances, and are very careful about their presentation in regards to fashion (probably includes a beanie), their language, and the tastes they share with other people (in movies, television, etc.). Therefore, they may slip into superficial behaviors, judging others by first impressions or even just their appearances or their social status. They are aware of how others perceive them, and are both conscientious and self-conscious. The skateboard itself is an aesthetic flare taken very far, reflecting their strong sense of nostalgia. Their nostalgia shows up in their other interests as well: they watch television & movies from the 80s and 90s, they started playing D&D after “Stranger Things” came out, and they genuinely enjoyed reading The Catcher in the Rye. Their tastes and tendencies may be nerdy and subversive, but because they are conscientious about how others perceive them, they are great at forming good relationships with others. They are sociable and know how to be likable. Sometimes they try to simplify themself for the easier consumption of others, and they definitely hide some of their stranger interests & ideas.