#Students For Fair Admissions v. UNC

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Alix Breeden at Daily Kos:

Companies are ripping off their diversity, equity, and inclusion masks and reaffirming the driving force behind their company-wide policies: profits above all. Following the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020, many companies ramped up their diversity efforts in response to a majority of U.S. voices (i.e., consumers) expressing a desire for representation. However, as some experts speculated, company changes to workplace environments appear to have been more of a temporary effort to appease disgruntled pocketbooks.

With felon-elect Donald Trump preparing to take the White House, some companies are leaning into Trump’s “anti-woke” and anti-DEI rhetoric and rolling back programs to make their workplaces more inclusive. Additionally, following the Supreme Court’s June 2023 decision to strike down affirmative action in colleges, companies seemingly moved away from their diversity efforts in an apparent fear of legal repercussions.

Over the last year or so, a disturbing trend of businesses such as Walmart, Tractor Supply Co., and Toyota, ditching DEI and LGBTQ+ inclusion programs has taken place, thanks to far-right provocateur Robby Starbuck leading intimidation efforts to get businesses to drop such programs and the general anti-DEI sentiments on the right.

#DEI#Diversity Equity and Inclusion#Business#Robby Starbuck#Ford#Walmart#Lowe's#Toyota#Tractor Supply Co.#LGBTQ+#Stanley Black & Decker#Affirmative Action#Diversity#Students For Fair Admissions v. UNC#Students For Fair Admissions v. Harvard

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 29 (Reuters) - The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday struck down race-conscious student admissions programs currently used at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina in a sharp setback to affirmative action policies often used increase the number of Black, Hispanic and other underrepresented minority groups on campuses.

The justices ruled in favor of a group called Students for Fair Admissions, founded by anti-affirmative action activist Edward Blum, in its appeal of lower court rulings upholding programs used at the two prestigious schools to foster a diverse student population.

The affirmative action cases represented the latest major rulings powered by the Supreme Court's conservative majority. The court in June 2022 overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that had legalized abortion nationwide and widened gun rights in a pair of landmark rulings.

Many institutions of higher education, corporations and military leaders have long backed affirmative action on campuses not simply to remedy racial inequity and exclusion in American life but to ensure a talent pool that can bring a range of perspectives to the workplace and U.S. armed forces ranks.

According to Harvard, around 40% of U.S. colleges and universities consider race in some fashion.

Harvard and UNC have said they use race as only one factor in a host of individualized evaluations for admission without quotas - permissible under previous Supreme Court precedents - and that curbing its consideration would cause a significant drop in enrollment of students from under-represented groups.

Critics, who have tried to topple these policies for decades, argue these policies are themselves discriminatory.

Many U.S. conservatives and Republican elected officials have argued that giving advantages to one race is unconstitutional regardless of the motivation or circumstances. Some have advanced the argument that remedial preferences are no longer needed because America has moved beyond racist policies of the past such as segregation and is becoming increasingly diverse.

The dispute presented the Supreme Court's conservative majority an opportunity to overturn its prior rulings allowing race-conscious admissions policies.

Blum's group in lawsuits filed in 2014 accused UNC of discriminating against white and Asian American applicants and Harvard of bias against Asian American applicants.

Students for Fair Admissions alleged that the adoption by UNC, a public university, of an admissions policy that is not race neutral violates the guarantee to equal protection of the law under the U.S. Constitution's 14th Amendment.

The group contended Harvard, a private university violated Title VI of a landmark federal law called the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bars discrimination based on race, color or national origin under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.

Lower courts rejected the group's claims, prompting appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court asking the justices to overturn a key precedent holding that colleges could consider race as one factor in the admissions process because of the compelling interest of creating a diverse student body.

Affirmative action has withstood Supreme Court scrutiny for decades, most recently in a 2016 ruling involving a white student, backed by Blum, who sued the University of Texas after being rejected for admission.

The Supreme Court has shifted rightward since 2016 and now includes three justices who dissented in the University of Texas case and three new appointees by former Republican President Donald Trump.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court ruled in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. (SFFA) v. University of North Carolina and SFFA v. President & Fellows of Harvard College that the colleges’ use of race as a decision factor in college admissions is a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The decision rejected prior justifications of race-conscious admissions based on universities’ interest in building racially diverse student populations and will have an immediate impact on admissions practices at selective institutions across the country.

Going forward, states and universities that hope to achieve the same racial diversity as they have under race-based affirmative action will need to pursue alternate policies to reach those goals. To what extent are there viable alternative policies to achieve those goals, and what is the likely effectiveness of those policies across states?

What are the legal arguments for affirmative action?

There have been two main legal arguments for the consideration of race in admissions. The first argument is that diversity benefits students and society. This “compelling interest in diversity” has been the central legal justification for continuing race-conscious admissions in prior affirmative action cases. Research consistently supports this argument. For example, students who enroll in more diverse college classrooms earn high GPAs, more diverse college discussion groups generate more novel and complex analyses, and across college settings, greater exposure to diverse thoughts and peers increases civic attitudes and engagement. Further, there are many benefits to a diverse workforce – such as a diverse military force, medical corps, or teaching profession. Expanding diversity in undergraduate programs is an essential step to building a workforce pipeline to achieve those benefits. However, in the majority opinion in SFFA, Chief Justice John Roberts was critical of how colleges set goals for diversity, arguing that the current implementation of race-conscious admissions fails to meet judicial strict scrutiny standards – namely that the diversity goals institutions set are vague, impossible to measure, and negatively affect some racial groups at the expense of others.

The second argument colleges (and amici in the two cases this term) make for the use of affirmative action is reparative. This perspective argues that race-conscious admission seeks to remedy persistent racial discrimination and ongoing racial inequities in society. Such inequities are rampant in K-12 education. While this may be the motivating goal for many colleges, the majority opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (in 1978) advanced the compelling interest in diversity justification over the social justice rationale as the primary legal justification for race-conscious admissions. While dissents from Justice Sonia Sotomayor and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson both advanced the argument that race-conscious admissions serves to remedy past discrimination, Chief Justice Roberts’ majority opinion argued that the Court has “long rejected” this legal justification, and that neither UNC nor Harvard advanced that argument in their defense of their admissions policies.

What will happen if colleges can’t consider race in admissions?

In the majority opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger, former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor noted that the Court expected “racial preferences will no longer be necessary” within 25 years of their decision and that “race-conscious admissions policies must be limited in time.” Indeed, that timeline factored significantly into oral arguments in the SFFA cases and in Chief Justice Roberts’ majority opinion. Enrollment trends do not indicate colleges are significantly more representative than they were in the early 2000s. A report from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce found that white and Asian students are more overrepresented at selective institutions, and Black, Hispanic, and Native students are more underrepresented, in 2020 than they were in the early 2000s. While enrollment of underrepresented minority (URM) students has increased over time, it has done so at a slower pace than broader demographic changes, and the share of URM students at selective universities is about half the share of URM students in the most recent 12th grade cohort.

Several states have banned race-conscious admissions, providing insights into what may happen following a national ban. Statewide URM enrollment slightly decreases following a ban on race-conscious admissions, and declines are larger at more selective institutions. One study found state bans reduced Black enrollment at top-50 public colleges by about one-third – from about 6% to 4%. One model estimates a national ban will result in a 2% reduction in URM representation at all four-year colleges and up to a 10% reduction in URM representation at the most selective four-year schools.

The effects of state bans on racial gaps in college admission and enrollment have persisted and slightly worsened over time at state flagship colleges. Beyond undergraduate admission, states that banned affirmative action experienced a 17% decline in URM medical school enrollment and a 12% reduction in URM graduate school enrollment. California’s ban on affirmative action shifted URM students to lower-quality undergraduate programs, reduced URM STEM graduation rates, and ultimately reduced URM students’ early career incomes by about 5% (with the largest declines for Hispanic students).

Achieving racial diversity without considering race

How should colleges rethink college admissions in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decisions? The White House has already released guidance to assist colleges with interpreting the decision and alternative policies to pursue. However, several theoretically compelling strategies will not fully overcome the anticipated drop in URM student enrollment following an affirmative action ban.

One way to admit students to highly selective colleges would be to randomly select a group of students from among a pool who meet a minimum GPA or test score. However, research finds that approach would result in substantially smaller shares of Black and Hispanic students than currently enrolled at selective colleges.

Others have suggested socioeconomic-based affirmative action as an alternative, and Justice Neil Gorsuch’s SFFA concurrence advanced this alternative as well. To be sure, Black families’ wealth is substantially lower than white families, so it is possible that a higher share of Black applicants might benefit from wealth-based affirmative action than the share of white applicants. But simulations find that wealth-based affirmative action would not achieve the same levels of racial diversity as race-conscious affirmative action, in part because the number of lower-income Black applicants is still smaller than the number of white lower-income applicants. As former Justice Harry Blackmun wrote in his concurrence in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, “to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race.” Further, many colleges currently tout being “need-blind” in their admissions review. In addition to encouraging more low-income students to apply, being “need blind” provides some colleges an exemption from the application of certain anti-trust laws when it comes to determining financial aid awards. Engaging in socioeconomic-based affirmative action may constitute being classified as “need aware” – potentially threatening eligibility for those exemptions.

In the wake of affirmative action bans, several states turned to top X% plans – offering guaranteed admission to a certain share of students from each high school. Studies suggest that while these approaches do increase URM enrollment, the effect is smaller than race-conscious admissions. In California, the top 4% plan increased URM enrollment in the UC system by 4%, compared to a 20% increase in URM enrollment when colleges use race-based affirmative action.

Colleges can also engage in expanded outreach to students, encouraging applications and providing students with assistance navigating the complex college application and financial aid processes. One version of expanded outreach is expanding the number and types of high schools and regions admissions officers visit during recruiting season, though this requires additional staff time. Other approaches have tried sending “pre-guarantees” to students – for example, sending students notices they’re eligible for free tuition at the state flagship, or piloting direct admission offers to students based on their test scores or high school transcripts. The University of California system engaged in extensive outreach following the state ban on race-conscious admissions but argued in an amicus brief in the Harvard and UNC cases that those efforts have been insufficient to achieve their diversity goals.

Eliminate practices that advantage the most advantaged

In addition to proactive efforts to recruit, admit, and enroll minoritized students, college should also eliminate admission practices that give an advantage to the most advantaged applicants.

First, end legacy preferences. Legacy admissions – giving an edge to students whose family members attended the college – give a boost to those who should need it the least. About the same share of the public opposes considering relative ties in college admissions (75%) as those who oppose considering race or ethnicity (74%) – with Republicans and Democrats opposing legacy considerations at about the same rate. This has always been a dubious policy, and now is the time for colleges to abandon the practice.

Second, inventory the use of early decision and early action application rounds. Early admission applicants are at least 25% more likely to gain admission at highly selective institutions under early decision. Early decision requires students to commit to a college prior to receiving a financial aid award (making is less appealing for lower- or middle-income applicants) and benefits students who can prepare application materials earlier in the year (likely because they have family and mentors who support application preparation). Early admissions applicants are about three times as likely to attend a private high school, and while 21% of Asian and 10% of white applicants applied early admissions somewhere, only 8% of Latino and 7% of Black students did so.

These practices will not alone overcome the anticipated drop in Black, Hispanic, and Native college enrollment in the wake of a national ban on race-conscious admissions but serve as a feasible first step. It is also important to note adjustments to admissions review criteria are not enough to affect enrollment. One analysis found that providing admissions officers with more information about students’ backgrounds increased the likelihood students from more challenging high school contexts (e.g., higher crime, less housing stability) were admitted. But the tool did not increase those students’ enrollment on average – and the colleges where it did were those that used the contextual information to better target scholarship aid. Colleges must back up admissions officers with financial aid and student services to ensure all students feel welcome and supported on campus. This is a particularly challenging task given the swath of bills from Republican legislatures targeting spending on the very diversity, equity, and inclusion programs that help students feel connected to campus.

A new precedent for college admissions

While the SFFA decision is a significant blow to colleges and universities that have long relied on race-conscious admissions to achieve institutional diversity goals, the decision doesn’t completely shut the door on revised approaches to admissions. For example, the Chief Justice included a key footnote that military academies are exempt from the decision, given their “distinct interests” – namely arguments that racial diversity in the military is essential to national security. This implies that there are compelling interests to diversity that would survive strict scrutiny review. The Court has set a high bar for when there is a compelling interest in considering race in admissions – but not removed the principle.

Further, the decision makes explicit that students can continue to reference their racial and ethnic identities in college essays and interviews and colleges can take those experiences into account in application review; however, the decision cautions such references and the role they play in admissions decisions must be tied to individual, non-racial characteristics. For example, colleges can give weight to a student’s “courage and determination” to overcome racial discrimination during holistic review. This is an important victory for those who worried that the decision would severely limit students’ ability to speak about how their racial identity shaped their experiences. However, that guidance will be difficult to implement in practice and is ripe for future legal challenges. While much remains to be understood about the SFFA decision and its impact, one clear takeaway is that this will not be the last word on how race can factor into college admissions.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Race Neutral’ Is the New ‘Separate but Equal’

From The Atlantic: On the first day of class in the fall of 1924, Martha Lum walked into the Rosedale Consolidated School. The mission-style building had been built three years earlier for white students in Rosedale, Mississippi.

Martha was not a new student. This 9-year-old had attended the public school the previous year. But that was before Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, banning immigrants from Asia and inciting ever more anti-Asian racism inside the United States.

At the time, African Americans were fleeing the virulent racism of the Mississippi Delta in the Great Migration north and west. To replace them, white landowners were recruiting Chinese immigrants like Martha’s father, Gong Lum. But instead of picking cotton, many Chinese immigrants, like Gong and his wife, Katherine, opened up grocery stores, usually in Black neighborhoods, after being shut out of white neighborhoods.

At noon recess, Martha had a visitor. The school superintendent notified her that she had to leave the public school her family’s tax dollars supported, because “she was of Chinese descent, and not a member of the white or Caucasian race.” Martha was told she had to go to the district’s all-Black public school, which had older infrastructure and textbooks, comparatively overcrowded classrooms, and lower-paid teachers.

Gong Lum sued, appealing to the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal-protection clause. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. All nine justices ruled in favor of school segregation, citing the “separate but equal” doctrine from 1896’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision.

“A child of Chinese blood, born in and a citizen of the United States, is not denied the equal protection of the law by being classed by the state among the colored races who are assigned to public schools separate from those provided for the whites when equal facilities for education are afforded to both classes,” the Court summarized in Gong Lum v. Rice on November 21, 1927.

A century from now, scholars of racism will look back at today’s Supreme Court decision on affirmative action the way we now look back at Gong Lum v. Rice—as a judicial decision based in legal fantasy. Then, the fantasy was that separate facilities for education afforded to the races were equal and that actions to desegregate them were unnecessary, if not harmful. Today, the fantasy is that regular college-admissions metrics are race-neutral and that affirmative action is unnecessary, if not harmful.

The Supreme Court has effectively outlawed affirmative action using two court cases brought on by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Organized by a legal strategist named Edward Blum, SFFA filed suit on behalf of Asian American applicants to Harvard as well as white and Asian applicants to UNC to claim that their equal-protection rights were violated by affirmative action. Asian and white Americans are overrepresented in the student body at selective private and public colleges and universities that are well funded and have high graduation rates, but they are the victims?This is indicative of a larger fantasy percolating throughout society: that white Americans, who, on average, stand at the more advantageous end of nearly every racial inequity, are the primary victims of racism. This fantasy is fueling the grievance campaigns of Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis. Americans who oppose affirmative action have been misled into believing that the regular admissions metrics are fair for everyone—and that affirmative action is unfair for white and Asian American applicants.

It is a fantasy that race is considered as an admissions factor only through affirmative action. But the Court endorsed SFFA’s call for “race neutral” admissions in higher education—effectively prohibiting a minor admissions metric such as affirmative action, which closes racial inequities in college admissions, while effectively permitting the major admissions metrics that have long led to racial inequities in college admissions. Against all evidence to the contrary, the Court claimed: “Race-neutral policies may thus achieve the same benefits of racial harmony and equality without … affirmative action policies.” The result of the Court’s decision: a normality of racial inequity. Again.

This is what the Court considers to be fair admissions for students, because the judges consider the major admissions metrics to be “race-neutral”—just as a century ago, the Court considered Mississippi public schools to be “separate but equal.”

Chief Justice John Roberts, in his majority opinion, recognized “the inherent folly of that approach” but doesn’t recognize the inherent folly of his “race neutral” approach.

History repeats sometimes without rhyming. “Race neutral” is the new “separate but equal.” The Court today claimed, “Twenty years have passed since Grutter, with no end to race- based college admissions in sight.” In actuality, twenty years have passed, with no end to racial inequity in sight.

Black, Latino, and Indigenous students continue to be underrepresented at the top 100 selective public universities. After affirmative action was outlawed at public universities in California and Michigan in the 1990s, Black enrollment at the most selective schools dropped roughly 50 percent, in some years approaching early-1970s numbers. This lack of diversity harms both students of color and white students.

In its reply brief in the UNC case, SFFA argued that the University of California system enrolls “more underrepresented minorities today than they did under racial preferences,” referencing the increase of Latino students at UC campuses from 1997 to 2019. But accounting for the increase in Latino students graduating from high school, those gains should be even larger. There’s a 23-point difference between the percentage of high-school graduates in California who are Latino and the percentage of those enrolled in the UC system.

Declines in racial representation and associated harms extend to graduate and professional programs. The UC system produced more Black and Latino medical doctors than the national average in the two decades before affirmative action was banned, and dropped well below the national average in the two decades after.

Underrepresentation of Black, Latino, and Indigenous students at the most coveted universities isn’t a new phenomenon, it isn’t a coincidence, and it isn’t because there is something deficient about those students or their parents or their cultures. Admissions metrics both historically and currently value qualities that say more about access to inherited resources and wealth— computers and counselors, coaches and tutors, college preparatory courses and test prep—than they do about students’ potential. And gaping racial inequities persist in access to each of those elements—as gaping as funding for those so-called equal schools in the segregated Mississippi Delta a century ago.

So what about class? Class-based or income-based interventions disproportionately help white students too, because their family’s low income is least likely to extend to their community and schools. Which is to say that low-income white Americans are far and away less likely than low-income Black and Latino Americans to live in densely impoverished neighborhoods and send their kids to poorly resourced public schools. Researchers find that 80 percent of low-income Black people and 75 percent of low-income Latino people reside in low-income communities, which tend to have lesser-resourced schools, compared with less than 50 percent of low-income white people. (Some Asian American ethnic groups are likely to be concentrated in low-income communities, while others are not; the data are not dis-aggregated to explore this.) Predominately white school districts, on average, receive $23 billion more than those serving the same number of students of color.

When admissions metrics value SAT, ACT, or other standardized-test scores, they predict not success in college or graduate school, but the wealth or income of the parents of the test takers. This affects applicants along racial lines, but in complex ways. Asian Americans, for example, have higher incomes than African Americans on average, but Asian Americans as a group have the highest income inequality of any racial group. So standardized tests advantage more affluent white Americans and Asian ethnic groups such as Chinese and Indian Americans while disadvantaging Black Americans, Latino Americans, Native Americans, and poorer Asian ethnic groups such as Burmese and Hmong Americans. But standardized tests, like these other admissions metrics, are “race neutral”?

Standardized tests mostly favor students with access to score-boosting test prep. A multibillion-dollar test-prep and tutoring industry was built on this widespread understanding. Companies that openly sell their ability to boost students’ scores are concentrated in immigrant and Asian American communities. But some Asian American ethnic groups, having lower incomes, have less access to high-priced test-prep courses.

Besides all of this, the tests themselves have racist origins. Eugenicists introduced standardized tests a century ago in the United States to prove the genetic intellectual superiority of wealthy white Anglo-Saxon men. These “experimental” tests would show “enormously significant racial differences in general intelligence, differences which cannot be wiped out by any scheme of mental culture,” the Stanford University psychologist and eugenicist Lewis Terman wrote in his 1916 book, The Measurement of Intelligence. Another eugenicist, the Princeton University psychologist Carl C. Brigham, created the SAT test in 1926. SAT originally stood for “Scholastic Aptitude Test,” aptitude meaning “natural ability to do something.”

Why are advocates spending millions to expand access to test prep when a more effective and just move is to ban the use of standardized tests in admissions? Such a ban would help not only Black, Native, and Latino students but also low-income white and Asian American students.

Some selective colleges that went test-optional during the pandemic welcomed some of their most racially and economically diverse classes, after receiving more applications than normal from students of color. For many students of color, standardized tests have been a barrier to applying, even before being a barrier to acceptance. Then again, even where colleges and universities, especially post-pandemic, have gone test-optional, we can reasonably assume or suspect that students who submit their scores are viewed more favorably.

When admissions committees at selective institutions value students whose parents and grandparents attended that institution, this legacy metric ends up giving preferential treatment to white applicants. Almost 70 percent of all legacy applicants for the classes of 2014–19 at Harvard were white.

College athletes are mostly white and wealthy—because most collegiate sports require resources to play at a high level. White college athletes make up 70 to 85 percent of athletes in most non-revenue-generating sports (with the only revenue-generating sports usually being men’s basketball and football). And student athletes, even ones who are not gaming the system, receive immense advantages in the admissions process, thus giving white applicants yet another metric by which they are the most likely to receive preferential treatment. Even Harvard explained as part of its defense that athletes had an advantage in admissions over nonathletes, which conferred a much greater advantage to white students over Asian American students than any supposed disadvantage that affirmative action might create. And white students benefit from their relatives being more likely to have the wealth to make major donations to highly selective institutions. And white students benefit from their parents being over-represented on the faculty and staff at colleges and universities. Relatives of donors and children of college employees normally receive an admissions boost.

Putting this all together, one study found that 43 percent of white students admitted to Harvard were recruited athletes, legacy students, the children of faculty and staff, or on the dean’s interest list (as relatives of donors)—compared with only 16 percent of Black, Latino, and Asian American students. About 75 percent of white admitted students “would have been rejected” if they hadn’t been in those four categories, the study, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, found.

While private and public universities tout “diversity” recruitment efforts, their standard recruitment strategies concentrate on high-income students who are predominantly white and Asian, at highly resourced schools, positioned to have higher grade point averages and test scores that raise college rankings. Public colleges and universities facing declines in state and federal funding actively recruit white and wealthy out-of-state students who pay higher fees. At many institutions, including a UC campus, “admission by exception,” a practice originally promoted as a means of expanding opportunities for disadvantaged groups, has been used to enroll international students with the resources to pay U.S. tuition fees.

Targeting international students of color to achieve greater diversity on campus disadvantages American students of color. Targeting students from families who can pay exorbitant out-of-state fees benefits white families, who have, on average, 10 times the household net worth of Black families.

Affirmative action attempted to compensate not just for these metrics that give preferential treatment to white students, but also for the legacy of racism in society. This legacy is so deep and wide that affirmative action has rightly been criticized as a superficial, Band-Aid solution. Still, it has been the only admissions policy that pushes against the deep advantages that white Americans receive in the other admissions metrics under the cover of “race neutral.

If anti-affirmative-action litigants and judges were really supportive of “race neutrality”—if they were really against “racial preferences”—then they would be going after regular admissions practices. But they are not, because the regular admissions metrics benefit white and wealthy students.

Litigants and judges continue to use Asian Americans as political footballs to maintain these racial preferences for white and wealthy students. Particularly in the Harvard case, SFFA’s Edward Blum used Asian plaintiffs to argue that affirmative action harms Asian American applicants. No evidence of such racist discrimination was found in the lower courts. According to an amicus brief filed by 1,241 social scientists, the so-called race-neutral admissions policy SFFA advocated for (which was just adopted by the highest Court) would actually harm Asian American applicants. It denies Asian American students the ability to express their full self in their applications, including experiences with racism, which can contextualize their academic achievements or struggles and counter racist ideas. This is especially the case with Hmong and Cambodian Americans, who have rates of poverty similar to or higher than those of Black Americans. Pacific Islander Americans have a higher rate of poverty than the average American.

Pitting Asian and Black Americans against each other is an age-old tactic. Martha Lum’s parents didn’t want to send their daughter to a “colored” school, because they knew that more resources could be found in the segregated white schools. Jim Crow in the Mississippi Delta a century ago motivated the Lums to reinforce anti-Black racism—just as some wealthy Asian American families bought into Blum’s argument for “race neutral” admissions to protect their own status. Yet “separate but equal” closed the school door on the Lums. “Race neutral” is doing the same. Which is why 38 Asian American organizations jointly filed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court in support of affirmative action at Harvard and UNC.

A century ago, around the time the Court stated that equal facilities for education were being afforded to both races, Mississippi spent $57.95 per white student compared with $8.86 per Black student in its segregated schools. This racial inequity in funding existed in states across the South: Alabama ($47.28 and $13.32), Florida ($61.29 and $18.58), Georgia ($42.12 and $9.95), North Carolina ($50.26 and $22.34), and South Carolina ($68.76 and $11.27). “Separate but equal” was a legal fantasy, meant to uphold racist efforts to maintain these racial inequities and strike down anti-racist efforts to close them.

Homer Plessy had sued for being kicked off the “whites only” train car in New Orleans in 1892. About four years later, the Court deployed the “separate but equal” doctrine to work around the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal-protection clause to defend the clearly unequal train cars and the exclusion of Black Americans like Plessy from better-equipped “whites only” cars. Later, the Court used the same doctrine to exclude Asian Americans like Martha Lum from better-equipped “whites only” schools.

The “separate but equal” doctrine was the Court’s stamp to defend the structure of racism. Just as Plessy v. Ferguson’s influence reached far beyond the railway industry more than a century ago, the fantasy of “race neutral” alternatives to affirmative action defends racism well beyond higher education. Evoking “race neutrality,” Justice Clarence Thomas recently dissented from the Supreme Court decision upholding a provision in the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that prohibits racist gerrymandering.

Now that “racial neutrality” is the doctrine of the land, as “separate but equal” was a century ago, we need a new legal movement to expose its fantastical nature. It was nearly a century ago that civil-rights activists in the NAACP and other organizations were gearing up for a legal movement to expose the fantasy of “separate but equal.” In this new legal movement, defenders of affirmative action can no longer use the false framing of affirmative action as “race conscious” and the regular admissions metrics as “race neutral”—a framing that has been used at least since the Regents of the University of California v. Bakkedecision in 1978, which limited the use of affirmative action. Racist and anti-racist is a more accurate framing than “race neutral” and “race conscious.”

Affirmative-action policies are anti-racist because they have been proved to reduce racial inequities, while many of the regular admissions metrics are racist because they maintain racial inequities. To frame policies as “race neutral” or “not racist” or “race blind” because they don’t have racial language—or because the policy makers deny a racist intent—is akin to framing Jim Crow’s grandfather clauses and poll taxes and literacy tests as “race neutral” and “not racist,” even as these policies systematically disenfranchised southern Black voters. Then again, the Supreme Court allowed these Jim Crow policies for decades on the basis that they were, to use today’s term, “race neutral.” Then again, voter-suppression policies today that target Black, Latino, and Indigenous voters have been allowed by a Supreme Court that deems them “race neutral.” Jim Crow lives in the guise of “racial neutrality.”

Everyone should know that the regular admission metrics are the racial problem, not affirmative action. Everyone knew that racial separation in New Orleans and later Rosedale, Mississippi, was not merely separation; it was segregation. And segregation, by definition, cannot be equal. Segregationist policies are racist policies. Racial inequities proved that then.

The Court stated in today’s ruling, “By 1950, the inevitable truth of the Fourteenth Amendment had thus begun to reemerge: Separate cannot be equal.” But it still does not want to acknowledge another inevitable truth of the Fourteenth Amendment that has emerged today: Race cannot be neutral.

Today, racial inequities prove that policies proclaimed to be “race neutral” are hardly neutral. Race, by definition, has never been neutral. In a multiracial United States with widespread racial inequities in wealth, health, and higher education, policies are not “race neutral.” Policies either expand or close existing racial inequities in college admissions and employment. The “race neutral” doctrine is upholding racist efforts to maintain racial inequities and striking down anti-racist efforts to close racial inequities.

Race, by definition, has never been blind. Even Justice John Harlan, who proclaimed, “Our Constitution is color-blind” in his dissent of Plessy v. Ferguson, prefaced that with this declaration: “The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country” and “it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage.”

In the actual world, the “color-blind” often see their color as superior, as Harlan did. In the actual world, an equal-protection clause in a constitution can be transfigured by legal fantasy yet again to protect racial inequity.

“Separate but equal” then. “Race neutral” now.

#atlantic article#no paywall#affirmative action#american politics#politics#get rid of Legacy admission

1 note

·

View note

Text

I hadn't heard of all of these, so I decided to do a little research. In the order Bryan listed them in:

Overturned in Dobbs v. Jackson. Formerly protected abortion rights.

Overturned in Loper Bright Enterprises et. al. v. Raimondo, Secretary of Commerce, et. al. The Chevron Doctrine formerly required courts to uphold federal agencies' interpretation of statutes if legislative authorities did not directly address an issue.

Overturned in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. (SFFA) v. President & Fellows of Harvard College (Harvard) and SFFA v. University of North Carolina (UNC). Formerly allowed organizations to institute policies that required hiring minorities.

Enablged in Grants Pass v. Johnson. Cities are now allowed to punish people for sleeping outside, even if they have no other option, because the Court decided that technically punishes conduct and not status. So, that Anatole France quote, but unironic.

And of course, while it's not mentioned in the tweet, there's Trump v. United States, which gives the President blanket immunity for "official actions". And probably a lot of other cases Bryan couldn't fit or didn't know about, because who keeps up with everything the courts do?

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Segregation and Color-Blindness

Lorraine Hansberry was ahead of her time when she dreamed of a society with no segregation. But her dream is still not reached and the sky is the limit but it is a very long way up to Saint Peter and his Paradise.

US CONSTITUTION – AMENDMENT XIV

Section 1.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

STUDENTS FOR FAIR ADMISSIONS, INC. v. PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT

No. 20–1199. Argued October 31, 2022—Decided June 29, 2023*

[*Together with No. 21–707, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina et al., on certiorari before judgment to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.]

[T]he Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points. We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today.

At the same time, as all parties agree, nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise. See, e.g., 4 App. in No. 21–707, at 17251726, 1741; Tr. of Oral Arg. in No. 20–1199, at 10. But, despite the dissent’s assertion to the contrary, universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today. (A dissenting opinion is generally not the best source of legal advice on how to comply with the majority opinion.) “[W]hat cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly. The Constitution deals with substance, not shadows,” and the prohibition against racial discrimination is “levelled at the thing, not the name.” Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. 277, 325 (1867). A benefit to a student who overcame racial discrimination, for example, must be tied to that student’s courage and determination. Or a benefit to a student whose heritage or culture motivated him or her to assume a leadership role or attain a particular goal must be tied to that student’s unique ability to contribute to the university. In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race. Many universities have for too long done just the opposite. And in doing so, they have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin. Our constitutional history does not tolerate that choice.

The judgments of the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit and of the District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina are reversed.

It is so ordered.

Éditions La Dondaine, Medium.com, 2023

Race and Racism, * Discrimination, * Affirmative Action, * US constitution, * US Supreme Court

0 notes

Text

The Supreme Court's Affirmative Action Decision and the Contested Concept of a Colorblind Constitution

By Jennifer Jang, Cornell University, Class of 2024

July 7, 2023

In last Thursday's historic judgment, the United States Supreme Court firmly addressed the controversial subject of racial discrimination in college admissions. Affirmative action, a policy intended to redress past racial injustices by amplifying representation of marginalized groups, has been a cornerstone of American higher education for over 50 years. However, the Supreme Court's consequential decision in the cases of Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina upheld the Constitution's commitment to universal fairness, dismantling a system often criticized for combating racial disparities with further racial classifications.

Harvard and the University of North Carolina (UNC) were involved in a lawsuit by the Students for Fair Admissions. Harvard's admissions policy, which factors in race, was challenged under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This provision, which forbids discrimination in private universities receiving federal funding, essentially echoes the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment –– a cornerstone of the Constitution that prohibits state-sanctioned discrimination. Both universities were found to have breached this constitutional standard by considering race in their admissions processes.

In a significant move, Justice Clarence Thomas put forth his concept of a "colorblind Constitution.” This concept maintains that the Constitution neither acknowledges nor condones racial discrimination. It posits that society can transcend racial divisions by steering clear of race-based considerations. This "colorblind Constitution" concept, while powerfully evocative, has faced fierce opposition within and outside the Court. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, one of only three Black justices who has served on the Supreme Court, asserted that dismissing race in legal considerations does not erase its lived reality for many Americans. Her dissent underscored the significant difference between abstract legal theory and the lived experience of many Americans for whom race is integral to their daily lives.

Justice Jackson's passionate dissent expressed concern that turning a blind eye to racial disparities does not eradicate their existence; it might instead unknowingly perpetuate them. Conservative legal scholars celebrated the ruling, arguing that establishing a clear colorblind standard within education eliminates any room for racial bias. Meanwhile, civil rights activists have expressed concerns about the ruling, arguing that the idea of a colorblind Constitution is unrealistic given the deep-seated, systemic racial discrimination in American society.

As the Supreme Court began its yearly term, observers speculated that three cases would allow the conservative-leaning justices to demonstrate their adherence to the principle of a colorblind Constitution. Interestingly, in two other significant cases, the Supreme Court veered away from colorblind interpretations. Decisions relating to the 1965 Voting Rights Act and a law governing Native American adoptions seemed to contradict the colorblind principle. In the Alabama case, the court surprisingly upheld a Voting Rights Act provision and ruled against a district map that diluted Black voting power. In another case concerning the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act, most of the law was upheld, providing some relief to civil rights advocates. They illustrate a dichotomy: a move towards race neutrality, as seen in the affirmative action case, contrasted by an effort to protect laws designed to redress racial imbalances.

By bringing an end to racial preferences in university admissions, the court illuminates the path toward a colorblind Constitution — one that honors the spirit and intent of its framers. While some advocate for a colorblind Constitution, others argue that such an approach fails to recognize the realities of racial discrimination in the U.S. The court left room for future race-based legal challenges, suggesting that defenders of federal laws must remain vigilant. These rulings lay bare a divide in constitutional interpretation and invite challenging questions about how the law should address race. As this conversation evolves, it's clear that the issue of race will persist as a focal point in American legal debates.

______________________________________________________________

Hurley, L. (2023, July 1). “colorblind constitution”: Supreme Court wrangles over the future of race in the law. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/supreme-court/colorblind-constitution-supreme-court-wrangles-future-race-law-rcna90661

Washington Free Beacon. (2023, June 30). The colorblind constitution prevails. Washington Free Beacon. https://freebeacon.com/columns/the-colorblind-constitution-prevails/

Wisse, R. (2023, July 6). Opinion | Harvard’s stages of grief over affirmative action. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/harvards-stages-of-grief-over-affirmative-action-sffa-court-higher-ed-87dd642a

Severino, C. C. (2023, June 30). A landmark victory for the Colorblind Constitution. National Review. https://www.nationalreview.com/bench-memos/a-landmark-victory-for-the-colorblind-constitution/

Doan-Nguyen, R. (2023, July 6). Harvard students protest Supreme Court ruling. Harvard Magazine. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2023/07/rally-against-scotus-admissions-ruling

0 notes

Text

CJ court watch - the race case

SCt decided Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, 600 U. S. ____ (2023) on June 29, 2023. Decision was more or less 6 - 3, and C.J. Roberts wrote for the Court.

Many elite colleges have for decades discriminated against Asian applicants based on race. “being Asian is the equivalent of a 140 point score penalty on your SAT when applying to top private universities. For example, a white student that scored 1360 on the SATs would be on equal footing with an Asian student that scored 1500.” Dhar, R., (2013, April 24). Do Elite Colleges Discriminate Against Asians? http://priceonomics.com/post/48794283011/do-elite-colleges-discriminate-against-asians. - now available at http://web.archive.org/web/20140812042017/http://priceonomics.com/post/48794283011/do-elite-colleges-discriminate-against-asians

Students for Fair Admissions sued Harvard and North Carolina. The evidence showed that race was a factor in discriminating between applicants. J. Gorsuch noted in his concurrence

Plainly, Harvard and UNC choose to treat some students worse than others in part because of race. To suggest otherwise—or to cling to the fact that the schools do not always say the quiet part aloud—is to deny reality.9

fn9 - 8Messages among UNC admissions officers included statements such as these: “[P]erfect 2400 SAT All 5 on AP one B in 11th [grade].” “Brown?!” “Heck no. Asian.” “Of course. Still impressive.”; “If it[’]s brown and above a 1300 [SAT] put them in for [the] merit/Excel [scholarship].”; “I just opened a brown girl who’s an 810 [SAT].”; “I’m going through this trouble because this is a bi-racial (black/white) male.”; “[S]tellar academics for a Native Amer[ican]/African Amer[ican] kid.” 3 App. in No. 21–707, pp. 1242–1251

The Court closed by ruling

For the reasons provided above, the Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points. We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today.

At the same time, as all parties agree, nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise. *** But, despite the dissent’s assertion to the contrary, universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today. (A dissenting opinion is generally not the best source of legal advice on how to comply with the majority opinion.) “[W]hat cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly. The Constitution deals with substance, not shadows,” and the prohibition against racial discrimination is “levelled at the thing, not the name.” Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. 277, 325 (1867). A benefit to a student who overcame racial discrimination, for example, must be tied to that student’s courage and determination. Or a benefit to a student whose heritage or culture motivated him or her to assume a leadership role or attain a particular goal must be tied to that student’s unique ability to contribute to the university. In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race.

Many universities have for too long done just the opposite. And in doing so, they have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin. Our constitutional history does not tolerate that choice.

The judgments of the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit and of the District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina are reversed.

0 notes

Text

The U.S. Supreme Court Strikes Down Over 40 Years of Court Precedent

By Luis Canseco-Lopez, George Mason University Class of 2024

July 4, 2023

On June 29, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court found in a joint case involving Harvard and the University of North Carolina that affirmative action violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. This decision is highly controversial and was ruled in a 6-3 decision, with all conservative judges joining the majority opinion while the remaining liberal judges dissented. Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion criticizing the use of race in college applications to determine enrollment. Now, college and universities, public and private, must use colorblind criteria in admissions. [1]

In Harvard’s case, the plaintiffs, mostly comprised of Asian-Americans, claimed Harvard’s Admission discriminated Asian-Americans by placing a limit on how many may be admitted. Harvard states and admits to using race in its admission because of a previous Supreme Court’s decision in Grutter v. Bollinger. [2] In Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), the court held Michigan’s Law School decision to narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body is not prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause. [3]

Meanwhile, the University of North Carolina lawsuit is like Harvard’s of using race to determine admission. UNC claimed it awards racial preferences to African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans; UNC identifies these students as “underrepresented minorities.” [4]

Both universities were sued by Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), an organization who stated purpose is “to defend human and civil rights secured by law, including the right of individuals to equal protection under the law.’’ [3] SFFA argued that race-based admission is a direct violation of Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Equal Protection Clause of the 14th amendment.

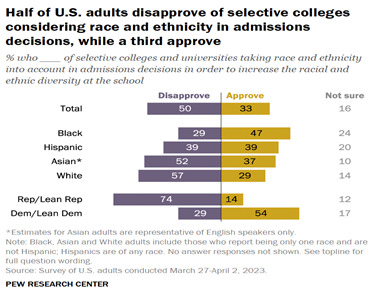

According to Pew Research Center, half of U.S. adults disapprove of selective colleges using race and ethnicity in admission decisions. [5] This study found African Americans support affirmative action at 47%. Meanwhile, 57% of White Americans disapprove of affirmative action. In addition, 52% of Asian Americans also dislike affirmative action. Hispanics were 50/50 split for or against affirmative action. Although half of Americans disagree with affirmative action, many articulate different reasoning. Some have similar viewpoints to Justice Chief Robert and argued that the U.S. Constitution is color-blind. Thus, affirmative action is a direct violation. Others don’t believe that systemic racism is a problem in American life or are skeptical of systemic racism in the U.S. education system. [2]

In Chief Justice Robert’s majority opinion, he states that universities for too long have judge individuals on the color of their skin rather than merit and skills. He also adds that our constitution does not tolerate the color of skin to be a factor in our education system [6]. Justice Clarence Thomas took a bigger jab at universities by calling affirmative action admissions “rudderless, race-based preferences designed to ensure a particular racial mix in their entering classes.” [6]

Justice Sonya Sotomayor and Justice Jackson were livid in their dissent opinion. Both Justices echo each other in the overturning of Grutter v. Bollinger and undoing decades of precedent. Sotomayor states, “The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society. Because the Court’s opinion is not grounded in law or fact and contravenes the vision of equality embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment, I dissent.” [6] Meanwhile, in Justice Jackson’s dissent, she compares the SFFA argument for “colorblindness for all” to Marie Antionette’s “let-them-eat-cake” obliviousness. Jackson also states that while the legal link to race in college admission is gone, it does not change the fact that race still matters in the lives of Americans daily. [6]

Although affirmative action is now considered unconstitutional, in Chief Justice Robert’s majority opinion, race can still be permissible in college admissions if a student wishes to write about their race and how it has impacted their life. [6] However, Robert made it explicitly clear that while a student can talk about their race, colleges and universities should consider a prospective student “as an individual—not on the basis of race”. [6] In addition, the court did not discuss eliminating affirmative in military academics because of “distinct interests" with the U.S. government. [1] This decision will also have an impact in primary and secondary schools. Top high schools like Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School in Virginia and Boston Latin in Massachusetts will have to eliminate race consideration in their applications. Both schools over the past few years saw an increase of African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans after implanting affirmative action in student admission. [7]

Regardless of institutions support or disapprove of affirmative action, this decision will have a ripple effect in the upcoming future. Decades of precedents are now thrown out the window on that Thursday evening. Universities and colleges now need to modify their policies and seek creative methods to preserve student diversity. Do not surprise if the Court must review future cases that involve race and education again. As Nina Totenburg puts it, “race has never been any easy subject for Americans to deal with, and it's about to get a lot harder.” [1]

______________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.npr.org/2023/06/29/1181138066/affirmative-action-supreme-court-decision

[2] https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/american-opinion-affirmative-action/

[3] https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/pdf/02-241P.ZS

[4] https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-707/199684/20211111164129792_UNC%20Cert%20Petition%20-%20Nov%2011%20-%20330pm%20002.pdf

[5] https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/06/08/more-americans-disapprove-than-approve-of-colleges-considering-race-ethnicity-in-admissions-decisions/

[6] https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf

[7] https://www.wtvr.com/news/local-news/maggie-walker-governors-school-diversity

0 notes

Text

Affirmative Action: What is the Future of College Admissions?

By Ayishat Shadare, University of Chicago Class of 2025

June 28, 2023

As the Supreme Court’s yearly term is coming to a close, many impactful decisions are made in late June and early July prior to their summer recess[1]. Many are awaiting one decision in particular: the Court’s ruling on two cases poised to challenge race-based affirmative action in college admissions[1]. The two cases were heard by the Supreme Court in the fall, and many believe the court’s decision can bring an end to affirmative action and overturn Grutter v. Bolliner, a 2003 case that has since set the tone for college admissions policies[2,3].

The organization Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) is the plaintiff of both cases brought against both Harvard and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The plaintiff alleges that both universities “award large racial preferences to African American and Hispanic applicants to the detriment of White and Asian American applicants and ignore alternative admissions tactics that might preserve student diversity”[2]. Prior to being brought to the Supreme Court, lower federal trial courts have ruled in favor of the universities[2].

In the case brought against Harvard, SFFA argues that the university “violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bars institutions that receive federal funding from discriminating based on race”[4]. The Harvard case is complexified by its use of subjective standards for evaluating personal characteristics such as “likability, courage, and kindness” of which the plaintiffs argue that Harvard unfairly discriminates against Asian American students in this regard[5].

The case against UNC Chapel Hill brings forth a different legal argument in which the plaintiff argues “that the University of North Carolina violates the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, which bars racial discrimination by government entities”[4]. The difference in legal bases is likely due to UNC Chapel Hill’s status as a public institution receiving support from the federal government while Harvard is a private institution [5]. This reflects a dual-sided challenge from proponents against affirmative action attempting to challenge the practice in all institutions for higher education, regardless of public or private status.

While the plaintiffs argued in the UNC Chapel Hill case that “the university discriminated against white and Asian applicants by giving preference to Black, Hispanic and Native American ones,” the university refuted this claim by claiming instead that “its admissions policies fostered educational diversity and were lawful under long standing Supreme Court precedent”[5].

Precedent cases include a 2016 case, Fisher v. University of Texas, in which affirmative action was upheld and allowed universities to diversify their student body through racial considerations in a 4-3 decision[5]. The court ruled that the university’s race conscious admissions process was constitutional and did not violate the 14th amendment’s Equal Protection Clause[5].

Another factor to consider if affirmative action practices are struck down by the Supreme court is the use of other racial proxies such as zip codes, house prices, and average test scores to signal the demographic makeup of a certain area[2]. These proxies have been considered as alternative means of diversifying admissions in a racially neutral manner as there are strong correlations between these various measures of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, and race[2].

In addition to proxies, institutions have also been attempting to practice class-based affirmative action as an alternative to race-based affirmative action[4]. Other alternative methods are test-optional or test-blind policies aimed at “reducing reliance on standardized tests or not considering them altogether,” and ending legacy admissions which are race-neutral but racially-correlated factors used in admissions[1].

Due to the court’s conservative majority and indications during oral arguments last fall, there is a widespread belief that the court will rule against affirmative action. There are several direct and indirect implications of a Supreme Court ruling declaring race-conscious admission practices unconstitutional. Directly, there will likely be a significant decrease in underrepresented student enrollment. This was seen after California “became the first state to ban the consideration of race and gender in hiring and public school admissions with Proposition 209,” and as a result, underrepresented minority enrollment fell by 50 percent at public University of California schools[3].

Over time, the ruling will likely result in less diverse student bodies and a larger discrepancy in post-graduation outcomes along racial lines. This directly impacts future college applicants and even college students planning to pursue some sort of graduate degree as well, as this looming decision can drastically shift the composition of future university classes and the admissions process as a whole.

______________________________________________________________

1. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/supreme-court/colleges-anxiously-await-landmark-affirmative-action-decision-supreme-rcna90835

2. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2023/01/16/suspense-supreme-court-affirmative-action/

3. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/06/22/the-supreme-court-could-end-race-in-college-admissions-heres-what-to-know-00103149

4. https://ed.stanford.edu/news/after-supreme-court-rulings-what-s-next-affirmative-action

5. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/31/us/supreme-court-harvard-unc-affirmative-action.html

0 notes

Text

Below are some excerpts from Justice Jackson's dissent. BTW, what she writes would be considered consistent with critical race theory. THIS is the interpretation of history that far right Republicans have crafted laws to ban in many red states--NOT just in grades K-12, but also at public universities. They do not want young people learning this.

Gulf-sized race-based gaps exist with respect to the health, wealth, and well-being of American citizens. They were created in the distant past, but have indisputably been passed down to the present day through the generations. Every moment these gaps persist is a moment in which this great country falls short of actualizing one of its foundational principles—the “self-evident” truth that all of us are created equal. Yet, today, the Court determines that holistic admissions programs like the one that the University of North Carolina (UNC) has operated, consistent with Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U. S. 306 (2003), are a problem with respect to achievement of that aspiration, rather than a viable solution (as has long been evident to historians, sociologists, and policymakers alike).

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR has persuasively established that nothing in the Constitution or Title VI prohibits institutions from taking race into account to ensure the racial diversity of admits in higher education. I join her opinion without qualification. I write separately to expound upon the universal benefits of considering race in this context, in response to a suggestion that has permeated this legal action from the start. Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) has maintained, both subtly and overtly, that it is unfair for a college’s admissions process to consider race as one factor in a holistic review of its applicants. See, e.g., Tr. of Oral Arg. 19. This contention blinks both history and reality in ways too numerous to count. But the response is simple: Our country has never been colorblind. Given the lengthy history of state-sponsored race-based preferences in America, to say that anyone is now victimized if a college considers whether that legacy of discrimination has unequally advantaged its applicants fails to acknowledge the well-documented “intergenerational transmission of inequality” that still plagues our citizenry.1

It is that inequality that admissions programs such as UNC’s help to address, to the benefit of us all. Because the majority’s judgment stunts that progress without any basis in law, history, logic, or justice, I dissent. [...] After the war, Senator John Sherman defended the proposed Fourteenth Amendment in a manner that encapsulated our Reconstruction Framers’ highest sentiments: “We are bound by every obligation, by [Black Americans’] service on the battlefield, by their heroes who are buried in our cause, by their patriotism in the hours that tried our country, we are bound to protect them and all their natural rights.”3 To uphold that promise, the Framers repudiated this Court’s holding in Dred Scott v. Sandford, 19 How. 393 (1857), by crafting Reconstruction Amendments (and associated legislation) that transformed our Constitution and society.4 Even after this Second Founding—when the need to right historical wrongs should have been clear beyond cavil—opponents insisted that vindicating equality in this manner slighted White Americans. So, when the Reconstruction Congress passed a bill to secure all citizens “the same [civil] right[s]” as “enjoyed by white citizens,” 14 Stat.27, President Andrew Johnson vetoed it because it “discriminat[ed] . . . in favor of the negro.”5 That attitude, and the Nation’s associated retreat from Reconstruction, made prophesy out of Congressman Thaddeus Stevens’s fear that “those States will all . . . keep up this discrimination, and crush to death the hated freedmen.”6 And this Court facilitated that retrenchment.7 Not just in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896), but “in almost every instance, the Court chose to restrict the scope of the second founding.”8 Thus, thirteen years pre-Plessy, in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 (1883), our predecessors on this Court invalidated Congress’s attempt to enforce the Reconstruction Amendments via the Civil Rights Act of1875, lecturing that “there must be some stage . . . when [Black Americans] tak[e] the rank of a mere citizen, and ceas[e] to be the special favorite of the laws.” Id., at 25. But Justice Harlan knew better. He responded: “What the nation, through Congress, has sought to accomplish in reference to [Black people] is—what had already been done in every State of the Union for the white race—to secure and protect rights belonging to them as freemen and citizens; nothing more.” Id., at 61 (dissenting opinion).

Justice Harlan dissented alone. And the betrayal that this Court enabled had concrete effects. Enslaved Black people had built great wealth, but only for enslavers.9 No surprise, then, that freedmen leapt at the chance to control their own labor and to build their own financial security.10 Still, White southerners often “simply refused to sell land to blacks,” even when not selling was economically foolish.11 To bolster private exclusion, States sometimes passed laws forbidding such sales.12 The inability to build wealth through that most American of means forced Black people into sharecropping roles, where they somehow always tended to find themselves in debt to the landowner when the growing season closed, with no hope of recourse against the ever-present cooking of the books.13 Sharecropping is but one example of race-linked obstacles that the law (and private parties) laid down to hinder the progress and prosperity of Black people. Vagrancy laws criminalized free Black men who failed to work for White landlords.14 Many States barred freedmen from hunting or fishing to ensure that they could not live without entering de facto reenslavement as sharecroppers.15 A cornucopia of laws (e.g., banning hitchhiking, prohibiting encouraging a laborer to leave his employer, and penalizing those who prompted Black southerners to migrate northward) ensured that Black people could not freely seek better lives elsewhere.16 And when statutes did not ensure compliance, state-sanctioned (and private) violence did.17 Thus emerged Jim Crow—a system that was, as much as anything else, a comprehensive scheme of economic exploitation to replace the Black Codes, which themselves had replaced slavery’s form of comprehensive economic exploitation.18 Meanwhile, as Jim Crow ossified, the Federal Government was “giving away land” on the western frontier, and with it “the opportunity for upward mobility and a more secure future,” over the 1862 Homestead Act’s three-quarter-century tenure.19 Black people were exceedingly unlikely to be allowed to share in those benefits, which by one calculation may have advantaged approximately 46 million Americans living today.20

[color emphasis added]

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson lashed out at the Supreme Court’s majority opinion on affirmative action in college admissions, with a dissent asserting that it will not bring a quicker end to racism.

“The best that can be said of the majority’s perspective is that it proceeds (ostrich-like) from the hope that preventing consideration of race will end racism. But if that is its motivation, the majority proceeds in vain,” Jackson wrote.

Jackson recused herself from one of the two cases heard by the court, involving Harvard, because of her role with the institution’s governing board as a lower court judge. Her opinion was confined to the University of North Carolina case.

Read her full dissenting opinion here.

#affirmative action#justice ketanji brown jackson#students for fair admissions v university of north carolina#critical race theory#dissenting opinion#supreme court#why we still need affirmative action#history repeats itself

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Supreme Court To Rule On Affirmative Action This Term

By Morgan Polen, University of Pittsburgh Class of 2025

November 17, 2022

The Supreme Court is looking at some hefty challenges this term, particularly with regards to affirmative action. Both Harvard and the University of North Carolina’s (UNC) admissions policies are under fire, with the petitioners concluding that the policies violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. These cases are preceded by Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), and Fisher v. University of Texas (2013), which each, in some fashion, upheld the permissibility and constitutionality of affirmative action policies. If the Supreme Court sides with the petitioners and chooses to overrule Grutter, we are going to come face-to-face with inexplicable, extraordinary changes in the composition of the student bodies in higher education.

For full article please visit

Students for Fair Admissions Challenges The Permissibility Of Race-Based Considerations In Higher Education

at

Pennsylvania PreLaw Land

0 notes

Text

The Supreme Court Monday agreed to hear two cases against U.S. colleges for allegedly "penalizing Asian American applicants" and using "race as a factor in admissions," a step that could affect affirmative action and equity programs in higher education.

The court is consolidating two different cases led by Students for Fair Admissions. One is against Harvard University and another is against the University of North Carolina.

"Harvard uses race at every stage of the admissions process," Students for Fair Admissions said in its petition asking the court to hear the Harvard case. "African-American and Hispanic students with PSAT scores of 1100 and up are invited to apply to Harvard, but white and Asian-American students must score a 1350…. In some parts of the country, Asian-American applicants must score higher than all other racial groups, including whites, to be recruited by Harvard."

"Like Harvard, UNC is devoted to using race indefinitely and at every stage of its admissions process," the petition in the case against UNC says.

Both Harvard's and UNC's admissions programs were upheld by lower courts, but Students for Fair Admissions argues that the Supreme Court should overturn the 2003 case Grutter v. Bollinger, which ruled schools could use race as a factor in admissions because such schools have a compelling interest in having diverse student bodies.

In its response to the petition from Students for Fair Admissions, Harvard argued its admission process did not in fact discriminate against Asian-Americans. It noted that it could not possibly admit even all applicants who have a perfect GPA and therefore must consider many other factors – one of which is "the capacity to contribute to racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, or geographic diversity."

"The consideration of race only ever benefits students who are otherwise highly qualified, and it is not decisive even for those candidates," Harvard said.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Students for Fair Admissions Challenges The Permissibility Of Race-Based Considerations In Higher Education

By Morgan Polen, University of Pittsburgh Class of 2025

November 16, 2022

“Affirmative action” often elicits mixed messages when it comes to breaking down its merits. There is one thing that is certain, though, and that is that affirmative action remains one of the ways in which the United States attempts to redress a rather dark and deplorable history of exploitation, racism, and marginalization. It is almost impossible to say that the makeup of our higher education system would look the same without affirmative action policies. According to statistics from the Pew Research Center, a whopping 74% of Americans believe that race or ethnicity should not be a consideration in college admissions [3].