#Stuart Brooks

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"On Duke's Birthday:" A Jazz Tribute by the Mike Westbrook Orchestra

Introduction: The jazz world is filled with tributes, homages, and celebrations of past masters, but few manage to capture the essence of their inspiration while forging new paths quite like Mike Westbrook’s “On Duke’s Birthday.” Released in 1985, this live album by the Mike Westbrook Orchestra is a dedicated suite to the memory of Duke Ellington, recorded on May 12, 1984, at Le Grand Theatre in…

#Brian Godding#Chris Biscoe#Classic Albums#Danilo Terenzi#Dominique Pifarély#Duke Ellington#Georgie Born#Jazz History#Kate Westbrook#Mike Westbrook#Mike Westbrook Orchestra#On Duke&039;s Birthday#Phil Minton#Steve Cook#Stuart Brooks#Tony Marsh

1 note

·

View note

Text

Black Cat Bones - Barbed Wire Sandwich

#black cat bones#barbed wire sandwich#60s#1960s#1969#blues rock#heavy blues rock#lp#vinyl record#album#album cover#Paul Tiller#Derek Brooks#Stuart Brooks#Terry Sims#paul kossoff

0 notes

Text

Quality Stuart Memes Served By Yours Truly:

Hiya Jimmy!

Hi Anne!

You wanna go for a hunt?

Sure Anne!

Jump in

I'm an oranged hoe

In an orange world

Life in Catholic

It's fantastic!

You can suck my dick

Undress me everyday

Screw the convos,

Life's a friggen sex show!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

I'm an oranged hoe

In an orange world

Life in Catholic

It's fantastic!

You can suck my dick

Undress me everyday

Screw the convos,

Life's a friggen sex show!

I'm a blonde Catholic hoe on a Protestant floor

I'm an Admiral too and a soldier

He's a hoe, he's a bro, got no humour at all, kiss me here, touch me there, Dismal Jimmy

You can touch, you can play, if you say 'i'm always yours'

OOH-WAOH!

I'm an oranged hoe

In an orange world

Life in Catholic

It's fantastic!

You can suck my dick

Undress me everyday

Screw the convos,

Life's a friggen sex show!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

Ah, ah, ah, yeah!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

OOH-WAOH! OOH-WAOH!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

Ah, ah, ah, yeah!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

OOH-WAOH! OOH-WAOH!

My Parliament's rubbish and William of Orange is ugly and someone I don't know is a piece of crap too!

He hates his son-in-law who married wee Mary and booted him off the British throne.

You can touch, you can play, if you say 'i'm always yours'

You can touch, you can play, if you say 'i'm always yours'

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

Ah, ah, ah, yeah!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

OOH-WAOH! OOH-WAOH!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

Ah, ah, ah, yeah!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

OOH-WAOH! OOH-WAOH!

I'm an oranged hoe

In an orange world

Life in Catholic

It's fantastic!

You can suck my dick

Undress me everyday

Screw the convos,

Life's a friggen sex show!

I'm an oranged hoe

In an orange world

Life in Catholic

It's fantastic!

You can suck my dick

Undress me everyday

Screw the convos,

Life's a friggen sex show!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

Ah, ah, ah, yeah!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

OOH-WAOH! OOH-WAOH!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

Ah, ah, ah, yeah!

Come on Jimmy, let's go fucking!

OOH-WAOH! OOH-WAOH!

Oh, I'm having so much fun!

Well Jimmy, we're just getting started!

Oh I love you Maria!

Starring:

James II

Anne Hyde

Margaret Brooke, Lady Denham

Elizabeth Stanhope, Lady Chesterfield

Arabella Churchill

Maria of Modena

Catherine Sedley

#Spotify#stuart memes#stuarts#stuartposting#17th century#james ii#anne hyde#margaret brooke lady denham#elizabeth stanhope lady chesterfield#arabella churchill#mary of modena#maria beatrice d'este#catherine sedley#history humour#history#utter nonsense#we have a pretty witty queue

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 𝔂𝓮𝓪𝓻𝓼 𝓪𝓰𝓸 𝓽𝓸𝓭𝓪𝔂 𝓓𝓸𝓬 𝓜𝓬𝓼𝓽𝓾𝓯𝓯𝓲𝓷𝓼 𝓹𝓻𝓮𝓶𝓲𝓮𝓻𝓮𝓭 𝓸𝓷 𝓓𝓲𝓼𝓷𝓮𝔂 𝓒𝓱𝓪𝓷𝓷𝓮𝓵!

𝚃𝚑𝚒𝚜 𝚜𝚑𝚘𝚠 𝚠𝚊𝚜 𝚜𝚘 𝚌𝚞𝚝𝚎!!

#Doc McStuffins#Disney#Chris Nee#Kiara Muhammad#Laya DeLeon Hayes#Lara Jill Miller#Robbie Rist#Loretta Devine#Jess Harnell#Jaden Isaiah Betts#Andre Robinson#Kimberly Brooks#Gary Anthony Williams#China Anne McClain#Stuart Kollmorgen#Doug Califano#Kay Hanley#Michelle Lewis

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BODYGUARD 2018

The thing is, David/Dave, I don't need you to vote for me, only to protect me.

#bodyguard#2018#richard madden#sophie rundle#keeley hawes#vincent franklin#nicholas gleaves#david westhead#paul ready#gina mckee#pippa haywood#ash tandon#nina toussaint-white#stuart bowman#michael shaeffer#tom brooke#matt stokoe#anjli mohindra

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well that was a lovely over 🥰

Century for Harry, half century for Joey and 250 lead 🙌

Bonus - Stui was on coms 😃

#cricfam#cricket#england cricket#cricketfandom#cricketslash#cricket fandom#joe root#stuart broad#harry brook

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer, Tried & True…

#mature style#classic menswear#vintage style#classic style#seersucker#paul stuart#brooks brothers#regimental stripe#suede loafers#loafers#penny loafers#summer style#summer

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Scotland Yard: Papa Charlie (2.7, LWT, 1972)

"You realise, of course, that anybody, no matter what their rank or position, anybody who was at that meeting - who had sight of this - is now under suspicion of passing information to that gang, don't you?"

"Yes, of course."

"Someone's working on the inside. Could be anybody. Could even be Sergeant Ward - or perhaps you?"

"No."

"Well, we'll see. I intend to find out who it is. And I'm going to give myself one hour in which to do it."

#new scotland yard#stuart douglass#john reardon#john woodvine#john carlisle#sally home#tony melody#michael turner#alison king#michael stainton#john caesar#victor brooks#susan brown#ken barker#les clark#derek ware#john hartley#dave carter#max faulkner#alan chuntz#clearly an attempt to do.. if not a 'bigger' episode exactly‚ then one with greater impact. shot entirely on film‚ we follow Kingdom during#the transport of a high profile prisoner (a gang boss) whilst simultaneously we see that his wife (hello Mrs Kingdom! back after her sole#previous appearance way back in 1.9) being kidnapped and held to ransom. it's...hmm. it's fine enough i suppose but it feels very unlike#the show to date; actually this feels almost like a watershed moment‚ the point at which heavily scripted‚ thoughtful cop drama ceased to#exist in the UK and was gradually replaced by greater emphasis on action and violence and hardness: the start of things like the second#iteration of Special Branch‚ into The Sweeney‚ into The Professionals. those shows were all capable of intelligence and nuance at times but#the focus became unmistakably Action and Spectacle (imo to the detriment of the genre). i might be egging this too much bc the ep still#finds some time to wrestle with moral quandries (but again‚ rather waves over Kingdom's unusual brutality in 'interviewing' a prisoner#suffering from Chekhov's Heart Complaint). Turner guests as another Chief Super‚ and would replace Woodvine in the 4th season#not as the same character i believe‚ but it's a safe bet this guest spot was instrumental in his later casting

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Iceman on eccentric Bob Flag and selling his own artworks in a rubbish tip

Last week, I blogged about the death of multi-talented British eccentric Bob Flag. In the summer of 1981, he was performing on stage off-West End in London as part of The Mad Show. Another of the Mad Show performers was Anthony Irvine, who later developed an ice-block-melting performance art routine as The Iceman and who, more recently, became a painty-painty real artist as AIM. The Iceman…

View On WordPress

#AIM#Anthony Irvine#art#Bob Flag#Bournemouth#comedy#Dave Brooks#eccentricity#GIANT Gallery#Greatest Show On Earth#Mad Show#Stuart Semple#The Iceman

0 notes

Text

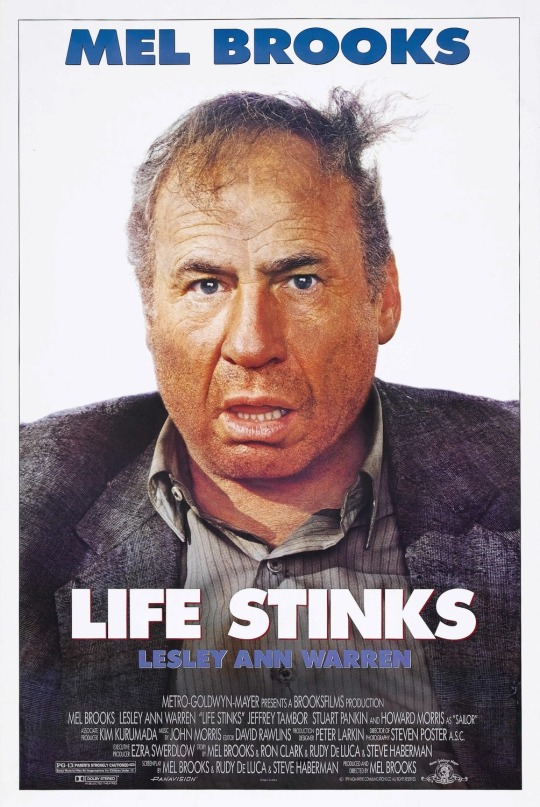

MARY FISK Quoted in Room to Dream

While David was editing [The Elephant Man], EMI edited a version without him, then called Mel [Brooks] and told him they'd cut the film to show him. Mel said, "I'm not even going to look at what you've done. We're going with David's version." The studio guys will crush you, and they were going to crush David, and Mel was an unreal advocate for him.

STUART CORNFELD Quoted in Room to Dream

The first cut of the film ran for almost three hours and was edited down to a final version that's two hours and six minutes. There were lots of shots of people walking down long hallways and atmosphere stuff that ended up being cut, but most of what was shot ended up onscreen. Mel had final cut but he deferred to David on that, and he took no credit at all on the film because he didn't want his name to create any expectations about what the film was.

0 notes

Text

* poll submitted by multiple 👤anonymous users and a few non-anonymous users that I did not ask for consent in tagging, so I’ve declined including them. DM me if you do want credit however.

After asking, I received over 20 submissions for this inquiry! Tumblr only permits one poll per post, so if you don’t see your crack ship here, it’s because I am saving the other submissions for Friday. (: Thank you for participating. 🗳️

Please remember these ships are crack ships! They are harmless and not meant to be taken seriously.

#tw: incest#crack!ships#l.m. montgomery#the blue castle#anne of green gables#anne shirley#barney snaith#emily of new moon#valancy stirling#emily byrd starr#jane of lantern hill#l. m. montgomery

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyway here is the full list of books I’ve read this year this is a mix of adult and YA with one middle school book the ones in bold are my big reccomenders

- Hild and Menewood by Nicola Griffith

- Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu by Tom Lin

- Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

- Joan by Kathrine J. Chen

- The Daughter of Doctor Moreau by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

- Butcher of The Forest by Premee Mohamed

- The Fox Wife by Yangsze Choo

- Red Rabbit by Alex Grecian

- Nettle & Bone by T. Kingfisher

- Starling House by Alix E. Harrow

- The Scholomance series by Naomi Novik

- Our Hideous Progeny by C.E. McGill

- Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart: and Other Stories by GennaRose Nethercott

- Spinning Silver by Naomi Novik

- Godkiller and Sunbringer by Hannah Kaner

- Vespertine by Margaret Rogerson

- The Weaver and the Witch Queen by Genevieve Gornichec

- A Clash of Steel: A Treasure Island Remix by C.B. Lee

- The Spirit Bares Its Teeth by Andrew Joseph White

- Lore by Alexandra Bracken

- The Thirteenth Tale by Diane Setterfield

- The Twisted Ones by T. Kingfisher

- Gallant by V.E. Schwab

- Clytemnestra by Costanza Casati

- The Eyes Are the Best Part by Monika Kim

- No One Will Come Back For Us: And Other Stories by Premee Mohamed

- Slasher Girls & Monster Boys by Various Authors

- The Libarary of Legends by Janie Chang

- The Bright Sword by Lev Grossman

- Girls Who Burn by MK Pagano

- Starve Arc by Andrew Michael Hurley

- Home Before Dark by Riley Sager

- Catfish Rolling by Clara Kumagai

- A Sorceress Comes To Call by T. Kingfisher

- The Cautious Traveller’s Guide to the Wastelands by Sarah Brooks

- Circe by Madeline Miller

- Woodworm by Layla Martínez

- The Dance Tree by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

- Sworn Soldier series by T. Kingfisher

- Bitter Greens by Kate Forsyth

- A Drop of Venom by Sajni Patel

- Black River Orchard by Chuck Wendig

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Jonathan Strange & Me Norrell by Susanna Clarke

- The Darkest Part of The Forest by Holly Black

- The Fortune Teller by Gwendolyn Womack

- Six Crimson Cranes series by Elizabeth Lim

- A House With Good Bones by T. Kingfisher

- Boys In the Valley by Philip Fracassi

- The West Passage by Jared Pechaček @jpechacek

- The Girl Who Fell Beneath The Sea by Axie Oh

- Revelator by Daryl Gregory

- The Last Cuentista by Donna Barba Higuera

- Hera by Jennifer Saint

- Life Ceremony by Sayaka Murata

- Thornhedge by T. Kingfisher

- The Drowned Woods by Emily Lloyd-Jones

- The Devil and the Dark Water by Stuart Turton

- Ink Blood Sister Scribe by Emma Törzs

- The Last Tale of the Flower Bride by Roshani Chokshi

- The Last Murder at the End of the World by Stuart Turton

- The Hearts We Sold by Emily Lloyd-Jones

- Sistersong by Lucy Holland

- House of Hollow by Krystal Sutherland

- The Book of Gothel by Mary McMyne

- The Hollow Places by T. Kingfisher

- The Children of Gods and Fighting Men by Shauna Lawless

- The Witch of Colchis by Rosie Hewlett

- Sisters of Sword & Song by Rebecca Ross

- Dragonfruit by Makiia Lucier

- Little Eve by Catriona Ward

- Pilgrim: A Medieval Horror by Mitchell Lüthi

- The Empusium by Olga Tokarczuk

- Juniper & Thorn by Ava Reid

- O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker

- everything by Shirley Jackson

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Don’t mention the word ‘liberalism,’ ” the talk-show host says to the guy who’s written a book on it. “Liberalism,” he explains, might mean Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama to his suspicious audience, alienating more people than it invites. Talk instead about “liberal democracy,” a more expansive term that includes John McCain and Ronald Reagan. When you cross the border to Canada, you are allowed to say “liberalism” but are asked never to praise “liberals,” since that means implicitly endorsing the ruling Trudeau government and the long-dominant Liberal Party. In England, you are warned off both words, since “liberals” suggests the membership of a quaintly failed political party and “liberalism” its dated program. In France, of course, the vagaries of language have made “liberalism” mean free-market fervor, doomed from the start in that country, while what we call liberalism is more hygienically referred to as “republicanism.” Say that.

Liberalism is, truly, the love that dare not speak its name. Liberal thinkers hardly improve matters, since the first thing they will say is that the thing called “liberalism” is not actually a thing. This discouraging reflection is, to be sure, usually followed by an explanation: liberalism is a practice, a set of institutions, a tradition, a temperament, even. A clear contrast can be made with its ideological competitors: both Marxism and Catholicism, for instance, have more or less explicable rules—call them, nonpejoratively, dogmas. You can’t really be a Marxist without believing that a revolution against the existing capitalist order would be a good thing, and that parliamentary government is something of a bourgeois trick played on the working class. You can’t really be a Catholic without believing that a crisis point in cosmic history came two millennia ago in the Middle East, when a dissident rabbi was crucified and mysteriously revived. You can push either of these beliefs to the edge of metaphor—maybe the rabbi was only believed to be resurrected, and the inner experience of that epiphany is what counts; maybe the revolution will take place peacefully within a parliament and without Molotov cocktails—but you can’t really discard them. Liberalism, on the other hand, can include both faith in free markets and skepticism of free markets, an embrace of social democracy and a rejection of its statism. Its greatest figure, the nineteenth-century British philosopher and parliamentarian John Stuart Mill, was a socialist but also the author of “On Liberty,” which is (to the leftist imagination, at least) a suspiciously libertarian manifesto.

Whatever liberalism is, we’re regularly assured that it’s dying—in need of those shock paddles they regularly take out in TV medical dramas. (“C’mon! Breathe, damn it! Breathe! ”) As on television, this is not guaranteed to work. (“We’ve lost him, Holly. Damn it, we’ve lost him.”) Later this year, a certain demagogue who hates all these terms—liberals, liberalism, liberal democracy—might be lifted to power again. So what is to be done? New books on the liberal crisis tend to divide into three kinds: the professional, the professorial, and the polemical—books by those with practical experience; books by academics, outlining, sometimes in dreamily abstract form, a reformed liberal democracy; and then a few wishing the whole damn thing over, and well rid of it.

The professional books tend to come from people whose lives have been spent as pundits and as advisers to politicians. Robert Kagan, a Brookings fellow and a former State Department maven who has made the brave journey from neoconservatism to resolute anti-Trumpism, has a new book on the subject, “Rebellion: How Antiliberalism Is Tearing America Apart—Again” (Knopf). Kagan’s is a particular type of book—I have written one myself—that makes the case for liberalism mostly to other liberals, by trying to remind readers of what they have and what they stand to lose. For Kagan, that “again” in the title is the crucial word; instead of seeing Trumpism as a new danger, he recapitulates the long history of anti-liberalism in the U.S., characterizing the current crisis as an especially foul wave rising from otherwise predictable currents. Since the founding of the secular-liberal Republic—secular at least in declining to pick one faith over another as official, liberal at least in its faith in individualism—anti-liberal elements have been at war with it. Kagan details, mordantly, the anti-liberalism that emerged during and after the Civil War, a strain that, just as much as today’s version, insisted on a “Christian commonwealth” founded essentially on wounded white working-class pride.

The relevance of such books may be manifest, but their contemplative depth is, of necessity, limited. Not to worry. Two welcomely ambitious and professorial books are joining them: “Liberalism as a Way of Life” (Princeton), by Alexandre Lefebvre, who teaches politics and philosophy at the University of Sydney, and “Free and Equal: A Manifesto for a Just Society” (Knopf), by Daniel Chandler, an economist and a philosopher at the London School of Economics.

The two take slightly different tacks. Chandler emphasizes programs of reform, and toys with the many bells and whistles on the liberal busy box: he’s inclined to try more random advancements, like elevating ordinary people into temporary power, on an Athenian model that’s now restricted to jury service. But, on the whole, his is a sanely conventional vision of a state reformed in the direction of ever greater fairness and equity, one able to curb the excesses of capitalism and to accommodate the demands of diversity.

The program that Chandler recommends to save liberalism essentially represents the politics of the leftier edge of the British Labour Party—which historically has been unpopular with the very people he wants to appeal to, gaining power only after exhaustion with Tory governments. In the classic Fabian manner, though, Chandler tends to breeze past some formidable practical problems. While advocating for more aggressive government intervention in the market, he admits equably that there may be problems with state ownership of industry and infrastructure. Yet the problem with state ownership is not a theoretical one: Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister because of the widely felt failures of state ownership in the nineteen-seventies. The overreaction to those failures may have been destructive, but it was certainly democratic, and Tony Blair’s much criticized temporizing began in this recognition. Chandler is essentially arguing for an updated version of the social-democratic status quo—no bad place to be but not exactly a new place, either.

Lefebvre, on the other hand, wants to write about liberalism chiefly as a cultural phenomenon—as the water we swim in without knowing that it’s wet—and his book is packed, in the tradition of William James, with racy anecdotes and pop-culture references. He finds more truths about contemporary liberals in the earnest figures of the comedy series “Parks and Recreation” than in the words of any professional pundit. A lot of this is fun, and none of it is frivolous.

Yet, given that we may be months away from the greatest crisis the liberal state has known since the Civil War, both books seem curiously calm. Lefebvre suggests that liberalism may be passing away, but he doesn’t seem especially perturbed by the prospect, and at his book’s climax he recommends a permanent stance of “reflective equilibrium” as an antidote to all anxiety, a stance that seems not unlike Richard Rorty’s idea of irony—cultivating an ability both to hold to a position and to recognize its provisionality. “Reflective equilibrium trains us to see weakness and difference in ourselves,” Lefebvre writes, and to see “how singular each of us is in that any equilibrium we reach will be specific to us as individuals and our constellation of considered judgments.” However excellent as a spiritual exercise, a posture of reflective equilibrium seems scarcely more likely to get us through 2024 than smoking weed all day, though that, too, can certainly be calming in a crisis.

Both professors, significantly, are passionate evangelists for the great American philosopher John Rawls, and both books use Rawls as their fount of wisdom about the ideal liberal arrangement. Indeed, the dust-jacket sell line of Chandler’s book is a distillation of Rawls: “Imagine: You are designing a society, but you don’t know who you’ll be within it—rich or poor, man or woman, gay or straight. What would you want that society to look like?” Lefebvre’s “reflective equilibrium” is borrowed from Rawls, too. Rawls’s classic “A Theory of Justice” (1971) was a theory about fairness, which revolved around the “liberty principle” (you’re entitled to the basic liberties you’d get from a scheme in which everyone got those same liberties) and the “difference principle” (any inequalities must benefit the worst off). The emphasis on “justice as fairness” presses both professors to stress equality; it’s not “A Theory of Liberty,” after all. “Free and equal” is not the same as “free and fair,” and the difference is where most of the arguing happens among people committed to a liberal society.

Indeed, readers may feel that the work of reconciling Rawls’s very abstract consideration of ideal justice and community with actual experience is more daunting than these books, written by professional philosophers who swim in this water, make it out to be. A confidence that our problems can be managed with the right adjustments to the right model helps explain why the tone of both books—richly erudite and thoughtful—is, for all their implication of crisis, so contemplative and even-humored. No doubt it is a good idea to tell people to keep cool in a fire, but that does not make the fire cooler.

Rawls devised one of the most powerful of all thought experiments: the idea of the “veil of ignorance,” behind which we must imagine the society we would want to live in without knowing which role in that society’s hierarchy we would occupy. Simple as it is, it has ever-arresting force, making it clear that, behind this veil, rational and self-interested people would never design a society like that of, say, the slave states of the American South, given that, dropped into it at random, they could very well be enslaved. It also suggests that Norway might be a fairly just place, because a person would almost certainly land in a comfortable and secure middle-class life, however boringly Norwegian.

Still, thought experiments may not translate well to the real world. Einstein’s similarly epoch-altering account of what it would be like to travel on a beam of light, and how it would affect the hands on one’s watch, is profound for what it reveals about the nature of time. Yet it isn’t much of a guide to setting the timer on the coffeemaker in the kitchen so that the pot will fill in time for breakfast. Actual politics is much more like setting the timer on the coffeemaker than like riding on a beam of light. Breakfast is part of the cosmos, but studying the cosmos won’t cook breakfast. It’s telling that in neither of these Rawlsian books is there any real study of the life and the working method of an actual, functioning liberal politician. No F.D.R. or Clement Attlee, Pierre Mendès France or François Mitterrand (a socialist who was such a master of coalition politics that he effectively killed off the French Communist Party). Not to mention Tony Blair or Joe Biden or Barack Obama. Biden’s name appears once in Chandler’s index; Obama’s, though he gets a passing mention, not at all.

The reason is that theirs are not ideal stories about the unimpeded pursuit of freedom and fairness but necessarily contingent tales of adjustments and amendments—compromised stories, in every sense. Both philosophers would, I think, accept this truth in principle, yet neither is drawn to it from the heart. Still, this is how the good work of governing gets done, by those who accept the weight of the world as they act to lighten it. Obama’s history—including the feints back and forth on national health insurance, which ended, amid all the compromises, with the closest thing America has had to a just health-care system—is uninspiring to the idealizing mind. But these compromises were not a result of neglecting to analyze the idea of justice adequately; they were the result of the pluralism of an open society marked by disagreement on fundamental values. The troubles of current American politics do not arise from a failure on the part of people in Ohio to have read Rawls; they are the consequence of the truth that, even if everybody in Ohio read Rawls, not everybody would agree with him.

Ideals can shape the real world. In some ultimate sense, Biden, like F.D.R. before him, has tried to build the sort of society we might design from behind the veil of ignorance—but, also like F.D.R., he has had to do so empirically, and often through tactics overloaded with contradictions. If your thought experiment is premised on a group of free and equal planners, it may not tell you what you need to know about a society marred by entrenched hierarchies. Ask Biden if he wants a free and fair society and he would say that he does. But Thatcher would have said so, too, and just as passionately. Oscillation of power and points of view within that common framework are what makes liberal democracies liberal. It has less to do with the ideally just plan than with the guarantee of the right to talk back to the planner. That is the great breakthrough in human affairs, as much as the far older search for social justice. Plato’s rulers wanted social justice, of a kind; what they didn’t want was back talk.

Both philosophers also seem to accept, at least by implication, the familiar idea that there is a natural tension between two aspects of the liberal project. One is the desire for social justice, the other the practice of individual freedom. Wanting to speak our minds is very different from wanting to feed our neighbors. An egalitarian society might seem inherently limited in liberty, while one that emphasizes individual rights might seem limited in its capacity for social fairness.

Yet the evidence suggests the opposite. Show me a society in which people are able to curse the king and I will show you a society more broadly equal than the one next door, if only because the ability to curse the king will make the king more likely to spread the royal wealth, for fear of the cursing. The rights of sexual minorities are uniquely protected in Western liberal democracies, but this gain in social equality is the result of a history of protected expression that allowed gay experience to be articulated and “normalized,” in high and popular culture. We want to live on common streets, not in fortified castles. It isn’t a paradox that John Stuart Mill and his partner, Harriet Taylor, threw themselves into both “On Liberty,” a testament to individual freedom, and “The Subjection of Women,” a program for social justice and mass emancipation through group action. The habit of seeking happiness for one through the fulfillment of many others was part of the habit of their liberalism. Mill wanted to be happy, and he couldn’t be if Taylor wasn’t.

Liberals are at a disadvantage when it comes to authoritarians, because liberals are committed to procedures and institutions, and persist in that commitment even when those things falter and let them down. The asymmetry between the Trumpite assault on the judiciary and Biden’s reluctance even to consider enlarging the Supreme Court is typical. Trumpites can and will say anything on earth about judges; liberals are far more reticent, since they don’t want to undermine the institutions that give reality to their ideals.

Where Kagan, Lefebvre, and Chandler are all more or less sympathetic to the liberal “project,” the British political philosopher John Gray deplores it, and his recent book, “The New Leviathans: Thoughts After Liberalism” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), is one long complaint. Gray is one of those leftists so repelled by the follies of the progressive party of the moment—to borrow a phrase of Orwell’s about Jonathan Swift—that, in a familiar horseshoe pattern, he has become hard to distinguish from a reactionary. He insists that liberalism is a product of Christianity (being in thrall to the notion of the world’s perfectibility) and that it has culminated in what he calls “hyper-liberalism,” which would emancipate individuals from history and historically shaped identities. Gray hates all things “woke”—a word that he seems to know secondhand from news reports about American universities. If “woke” points to anything except the rage of those who use it, however, it is a discourse directed against liberalism—Ibram X. Kendi is no ally of Bayard Rustin, nor Judith Butler of John Stuart Mill. So it is hard to see it as an expression of the same trends, any more than Trump is a product of Burke’s conservative philosophy, despite strenuous efforts on the progressive side to make it seem so.

Gray’s views are learned, and his targets are many and often deserved: he has sharp things to say about how certain left liberals have reclaimed the Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt and his thesis that politics is a battle to the death between friends and foes. In the end, Gray turns to Dostoyevsky’s warning that (as Gray reads him) “the logic of limitless freedom is unlimited despotism.” Hyper-liberals, Gray tells us, think that we can compete with the authority of God, and what they leave behind is wild disorder and crazed egotism.

As for Dostoyevsky’s positive doctrines—authoritarian and mystical in nature—Gray waves them away as being “of no interest.” But they are of interest, exactly because they raise the central pragmatic issue: If you believe all this about liberal modernity, what do you propose to do about it? Given that the announced alternatives are obviously worse or just crazy (as is the idea of a Christian commonwealth, something that could be achieved only by a degree of social coercion that makes the worst of “woke” culture look benign), perhaps the evil might better be ameliorated than abolished.

Between authority and anarchy lies argument. The trick is not to have unified societies that “share values”—those societies have never existed or have existed only at the edge of a headsman’s axe—but to have societies that can get along nonviolently without shared values, aside from the shared value of trying to settle disputes nonviolently. Certainly, Americans were far more polarized in the nineteen-sixties than they are today—many favored permanent apartheid (“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever”)—and what happened was not that values changed on their own but that a form of rights-based liberalism of protest and free speech convinced just enough people that the old order wouldn’t work and that it wasn’t worth fighting for a clearly lost cause.

What’s curious about anti-liberal critics such as Gray is their evident belief that, after the institutions and the practices on which their working lives and welfare depend are destroyed, the features of the liberal state they like will somehow survive. After liberalism is over, the neat bits will be easily reassembled, and the nasty bits will be gone. Gray can revile what he perceives to be a ruling élite and call to burn it all down, and nothing impedes the dissemination of his views. Without the institutions and the practices that he despises, fear would prevent oppositional books from being published. Try publishing an anti-Communist book in China or a critique of theocracy in Iran. Liberal institutions are the reason that he is allowed to publish his views and to have the career that he and all the other authors here rightly have. Liberal values and practices allow their most fervent critics a livelihood and a life—which they believe will somehow magically be reconstituted “after liberalism.” They won’t be.

The vociferous critics of liberalism are like passengers on the Titanic who root for the iceberg. After all, an iceberg is thrilling, and anyway the White Star Line has classes, and the music the band plays is second-rate, and why is the food French instead of honestly English? “Just as I told you, the age of the steamship is over!” they cry as the water slips over their shoes. They imagine that another boat will miraculously appear—where all will be in first class, the food will be authentic, and the band will perform only Mozart or Motown, depending on your wishes. Meanwhile, the ship goes down. At least the band will be playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” which they will take as some vindication. The rest of us may drown.

One turns back to Helena Rosenblatt’s 2018 book, “The Lost History of Liberalism,” which makes the case that liberalism is not a recent ideology but an age-old series of intuitions about existence. When the book appeared, it may have seemed unduly overgeneralized—depicting liberalism as a humane generosity that flared up at moments and then died down again. But, as the world picture darkens, her dark picture illuminates. There surely are a set of identifiable values that connect men and women of different times along a single golden thread: an aversion to fanaticism, a will toward the coexistence of different kinds and creeds, a readiness for reform, a belief in the public criticism of power without penalty, and perhaps, above all, a knowledge that institutions of civic peace are much harder to build than to destroy, being immeasurably more fragile than their complacent inheritors imagine. These values will persist no matter how evil the moment may become, and by whatever name we choose to whisper in the dark.

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rest of the image from the ECB AI Christmas set. I don’t think they *needed* to make some of these - they must exist in real life 😂

I promise I’m not the England Cricket IG admin

I can understand WHY you might think it 😂

Merry Christmas all! Hope you have a great day (if you celebrate)

#cricfam#cricket#cricketfandom#england cricket#cricketslash#cricket fandom#ben stokes#joe root#jos buttler#stuart broad#jimmy anderson#ben duckett#zak crawley#harry brook#Chris woakes#mark wood#Jofra archer

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 13, 2025: Book of Zippers, Luci Arbus-Scandiffio

Book of Zippers Luci Arbus-Scandiffio

When I was a child I was always touching something the crease in the wall the crease in the man’s face a button to the umbrella which I broke by pressing thirty times in a single day. Allegedly, I was unintelligible— like a foghorn I bleated and filled my chest with air. I lived like a raisin stuck in someone else’s pocket— was happiest in winter til my birthmark turned red. Blood red! And slightly blue on the edge. In the children’s wing they froze it off—I slept like a number between 1 and 10. The girl next to me was getting her ulna reset. She was hidden by geraniums which were planted between our beds. I assumed “reset” was a button the nurse would press— the sound was like a scissor slicing open a vinyl chair. Then I felt my own arm unzipping, the butterfly escaping, a hundred white stars falling out.

==

More dispatches from childhood: + Paralysis, Peter Boyle + from Seven Skins, Adrienne Rich + Late Confession, Gary Soto

Today in:

2024: Broken Periodic, Maya C. Popa 2023: Speech to the Young: Speech to the Progress-Toward (Among them Nora and Henry III), Gwendolyn Brooks 2022: We Lived Happily During the War, Ilya Kaminsky 2021: Hurry, Marie Howe 2020: Oh, Robert Creeley 2019: It Was Summer Now and the Colored People Came Out Into the Sunshine, Morgan Parker 2018: In Two Seconds, Mark Doty 2017: Aubade, Louis MacNeice 2016: Before, Ada Limón 2015: Sign for My Father, Who Stressed the Bunt, David Bottoms 2014: Ullapool Bike Ride, Chris Powici 2013: Clothespins, Stuart Dybek 2012: Ghost Story, Matthew Dickman 2011: Graves We Filled Before the Fire, Gabrielle Calvocoressi 2010: On Being Asked To Write A Poem Against The War In Vietnam, Hayden Carruth 2009: The Bear-Boy of Lithuania, Amy Gerstler 2008: Today’s News, David Tucker 2007: All There is to Know About Adolph Eichmann, Leonard Cohen 2006: Gamin, Frank O’Hara 2005: [this is what you love: more people. you remember], D.A. Powell

11 notes

·

View notes