#Stop Spreading Conspiracy Theories. stop it! learn skepticism!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I was listening to the "Wellness to QAnon Pipeline" episode of Maintenance Phase, which is as it sounds an episode about how people start off well-meaning and curious and end up drawn into QAnon conspiracy theories, and honestly it mimics a lot of behavior I've seen from the left recently.

Like at its core, QAnon believes that there is an elite class of people who hold all the power and can get away with any number of horrible crimes, because the rest of us are all powerless peasants who are being kept in the dark. The only real difference between them and leftist conspiracy theorists is that QAnon calls the elite class (((globalists))) and leftists call them billionaires, but once you start thinking like that it is SUCH a slippery slope from one to the other. It's incredibly dangerous.

It's stuff like confidently stating that Boeing got away with assassinating whistleblowers even though there's zero evidence and it doesn't even make sense that they would do that. Or insisting that Democrats are intentionally losing elections in order to play up the threat of Republicans in order to get elected, which again makes zero sense. It's insisting that the Democratic party fails on purpose because they are one discrete entity that moves in perfect unison and not, like, thousands and thousands of people with different ideas and goals who sometimes work at cross purposes. It's insisting that the reason American healthcare is bad is because the CEOs are all just evil megalomaniacs hitting the "deny care" button repeatedly, instead of understanding that our healthcare is incredibly complicated with a million interlocked parts that all feed into one another. It's insisting that a real progressive will never be elected because "they" won't let that happen, when there is zero evidence that those progressive candidates ever had any real support within the electorate.

It is - basically - the idea that bad things happen because Bad People are doing Bad Things, and the refusal to admit that sometimes bad things happen because of an incredibly complex web of causes and effects that can't be predicted or controlled.

And it's not like there's not any truth to it. Obviously healthcare and pharmaceutical companies put profits over human lives. Obviously billionaires and corporations interfere in politics. But ultimately most things are just really complicated, and anyone who's trying to sell you a fantasy that it's just the Bad People who are causing problems and all we need to do is get rid of them and let The Will of the People take over is either lying to you or is dangerously misinformed. Use your critical thinking, be a skeptic, and don't be blinded by people promising to sell you simple solutions that feel good.

#sorry for getting on my soapbox#it's late and i can't sleep because i can't FUCKING breathe. so have an annoyed and sanctimonious rant#Stop Spreading Conspiracy Theories. stop it! learn skepticism!#skepticism umbrella#us politics

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yo Gentiles! Stop trying to goysplain the history of the I/P conflict at us Jews.

We have studied this conflict extensively, and often for years, because we've had to. Because even when we are Jews in diaspora who have never returned to the Levant and never plan to, the antisemitism that this conflict generates still puts us in danger. And as many of you who are paying attention have witnessed, there has been a drastic world-wide rise in antisemitism over the past month.

When you try to "teach" us about it, especially when MOST of you are using talking points that were developed by Neo-Nazis and the KKK, all you are showing us is that you are lazy, patronizing antisemites.

If you actually want to HELP the Palestinians in this conflict (and I think that some of you do), you need to accept that the following 10 things are true:

We Jews most likely know more about the history of this conflict than you do. We have had to study it in all of its nuance, in all of its painful detail, in order to understand the broader Jewish world. We have to understand the broader Jewish world to decode how Neo-Nazis like Richard Spencer and David Duke are using the I/P conflict to coordinate attacks on Jews in diaspora.

.

We Jews have to know about the I/P conflict for our own safety. But many of you gentiles are learning about it for the first time. And instead of understanding how complex the conflict is, you are turning it into a wargame fantasy where you get to playact as a freedom fighter in La Glorious Revolution. Then you coordinate social media attacks against Jews online, and you go out and attack Jews in person, and you harass us until our mental health crumbles. Great job, goys! Great. Fucking. Job.

.

You are goysplaining Jewish history at us. Stop trying to tell us a bunch of propaganda that you learned from TikTok, Instagram, and Tumblr memes. It just shows us that you're lazy, and that you've got a lot of Jew-hatred that you need to unpack.

.

When we tell you that you're wrong, listen to what we have to say. Don't talk over us. Use this as an opportunity to do further research. Otherwise you're just behaving like some Fox News obsessed Boomer raging on about election fraud and vaccines.

.

The Palestinian people need our help, but you are making a TERRIBLE case for helping them when you base your arguments for helping them on shitty propaganda you learned on TikTok, Instagram, and Tumblr.

.

Let me say this again: Your bullshit propaganda DOES NOT HELP THE PALESTINIAN PEOPLE, and it is easily debunked by just a few Wikipedia deep-dives.

.

When you spread this propaganda, you sound like the idiots on Fox News that knowingly spread conspiracy theories about Covid. Not only is the bullshit you're repeating easily proven wrong, but you're just showing yourself to be untrustworthy at best ... and at worst, a bunch of opportunistic liars.

.

When you regurgitate propaganda at us Jews, all you are telling us is that you don't give enough of a shit about the Palestinian people to do ANY research into the history of this conflict, other than looking at some infographics and memes.

.

You are making us Jews VERY wary and skeptical of you, because most of the "information" you've learned from TikTok, Instagram, and Tumblr is influenced by Neo-Nazi and KKK propaganda, and you are being useful idiots for white supremacists.

.

Again, repeating fake shit about this conflict DOES NOT HELP the Palestinian people. It just makes Jews distrust you. And it makes us SCARED to get involved in this movement. Because we are NOT going to march side-by-side with goyim that are spreading dangerous antisemitic lies about Jewish history and Jewish people.

AND NONE OF THIS MATTERS. NONE OF YOUR BULLSHIT FAKE HISTORY MATTERS!!

Because Palestinians are dying!

So stop trying to tell Jews made up stories about our history.

LISTEN TO JEWISH VOICES ABOUT JEWISH HISTORY. (And DON'T listen to JVP, for fucks sake. Learn more here.)

Accept that we know more about the history of the I/P conflict than you do.

AND START WORKING TO HELP PALESTINIANS.

ANERA

Palestine Children's Relief Fund

Doctors Without Borders

#and when i say gentiles - i am mostly referring to white gentiles of the american persuasion who've never studied world history#jumblr#judaism#jewish history#jewblr#jewish#and just know - JVP does NOT speak for Jewish people#if you are getting your information from JVP then you are just telling us Jews that you have a LOT of antisemitism that you need to unpack#NOTE - I report and block antisemites. If any antisemites comment on this post you will be reported and blocked. You have been warned.#antisemitism tw

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

mutated plants prompt

Prompt: “Mutated plants like fruits and vegetables have gained sentience, and no longer want their kind to be eaten. The Plant War has begun.“ by @writing-prompt-s

Typo edits, again. I apparently cannot see my own typos before I post things.

*****

The smell of freshly cut grass is their yell of warning. They are killing us, brothers, it screams, get away, as humans breathe in it’s clean scent happily. They never do, never have, but they always warn their brothers.

Although humans do not understand them, they talk to them, too. Stop your massacre or we will fight back. We will kill you. You will regret your choices.

Their screams are useless, even after centuries. Instead of stopping the bloodshed, the partly-genocide, humans develop tools specifically for cutting them down. For torturing them. For aesthetics. For their smell that they don’t recognize as pain.

Over time, they learn that humans enjoy the smell of slaughter.

The scent changes. They no longer scream warnings. They scream war. The grass isn’t the only thing that starts to the call, it’s just the first, the flowers get the message first, opening their blooms and sending the message among the bees, with their pollen.

That is where it really spreads.

It spreads to gardens, boxes of vegetables and herbs and fruit. It spreads to open forests, trees stiffening their branches and thickening their bark, reinforcing their barrier to hide their sap, making it harder to obtain and harder for axes to cut them down for shelter or furniture or sculpture or cabinets or anything else.

The plants humans eat aren’t the only ones that suffer, but they are the ones that rebel the hardest, at least at first. Eventually, every plant joins the fight.

They start their revolution against the humans that consume only them, not the ones that eat animals (that also eat them — they are more than food and they will prove it, but they must start small to be successful and the animals, at least, are respectful and feed them once they are dead, unlike humans who burn themselves to ash and pollute their earth, or get buried in wooden boxes), not the ones that eat animal products like honey and milk and cheese.

Eventually, this will be a war between all humans and all plants, but if they start too big then they will lose before it’s begun.

Vegans begin to feel the effects, most refusing to turn elsewhere for nutrition even as their food rots in their stomach, eating at the lining, destroying them. Their gardens grow big, grow bright, grow tart and sour. It’s just a ploy to make them eat more, so they’ll die faster, stop eating sooner.

Sacrifices are made, they must be. Most are willing, planted from centuries and generations of death. Humans have been eating them since the beginning. This is years of contempt grown wild.

The Vegans (plant-killers, captors, masters of slaughter, slayers) do not change their diet. They blame the farmers, the supermarket, the new fertilizer they tried for bigger harvests. But they do not change, for the most part.

They continue to eat, some claiming the black interior of their stomachs (rotting from the inside out) and the dour diagnosis of doctors to be false. A conspiracy theory hidden by the government.

Their attack continues, affecting the dieters that survive off of salad and the vegetarians. They begin to rot.

The Plant-Killers begin to die. More plants hop on the train, herbs turning meals bitter and indigestible.

People start vomiting, dry-heaving, thinning out from lack of nutrition. Some begin to get the gist, turning to meat as their main source, avoiding vegetables and fruit like the plague. Which is an appropriate response.

It’s spread worldwide, spread to infect everyone who dares to eat them.

Flowers bloom to spell messages in meadows — stop eating us and you will be cured — but it’s not enough. Doctors scramble to cure this new disease, scraping insides and looking at the bile under microscopes.

They will not find a cure fast enough.

A news reporter speaks quietly, green-faced and wide-eyed. “The plants are rebelling,” they whisper, too late. “We need to stop eating them.”

Headlines center around the new dilemma. Flowers spell new messages, more warnings, more instructions. Skeptics become fewer and fewer, but they never truly die out. Some people will deny the truth until they’re dead and rotting.

Ivy crawls up houses, devouring them like humans devour their brethren, encapsulating some within their homes and growing in their corpses as retribution.

Humans make a hotline for plant related emergencies.

They can’t hire enough people to answer all the calls.

“Mother Nature is angry,” one activist claims, holding signs outside the White House in a protest and demanding that laws (something, anything) be passed to end this suffering. “We have been eating parts of her and building over others. It needs to stop before she kills us all.”

A politician, elsewhere, lounging in his home smiles at the camera crew. “This will blow over,” he says, still smiling, with lines around his eyes, “Mother Nature isn’t real.” His statement is broadcast on every major news channel.

A month later, he’s rotted to the outside and found dead in his home. A college student is the only one who writes the article on it in their school newspaper.

Moss overtakes his body, his home, and his family perishes soon after. No prisoners, no mercy.

War takes no prisoners. Many must die before their message is understood because blood is the only way to convey a serious message.

Respect nature, the flowers howl, respect us or perish.

Cut grass begins to smell like spoiled milk, like rotted meat, like the most disgusting thing you can imagine. People start to let it grow wild, afraid.

The death count rises higher. Some people leave their homes, walk into forests never to come out again, never seen. Others begin to worship nature, praying in their garden, their lawn, to the house plants lined on their windowsills.

Those who start the worship magically become cured. A little girl bites into an orange that fell at her feet and she does not die. Her symptoms (the vomiting, the thinness of her blood, the lightheadedness, the rot in her stomach, disappears. She is healthy. Her family learns to only eat the fruit that is offered to them.

They are interviewed, the little girl studied by doctors and her story is published.

The flowers (live-streaming via drones 24/7) spell out her name.

More begin to follow in their footsteps. More people are healed. The skeptics and disbelievers continue to rot.

It takes months (years) for the novelty to die down. For the plants to be respected. Some still don’t, still eat the poison because they all believe that they’re the one exception to the rule, and they pay that price. The rest, those who listen, prosper.

Humans have learned their lesson. Millions of deaths, millions who changed their habits too late to be healed fully, stomachs broken, but alive, millions who made the right choice and live without any reminder of the death Nature wrought.

The Plant War is over.

#prompt fill#writeblr#writing#writblr#creative writing#nikkywritesstories#nikkywritesprompts#my writing#tw vomiting#tw death#repost from my old blog

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Columbus: Master Double Agent and Portugal’s 007

Henry IV of Spain – known as "The Impotent" for his weakness, both on the throne and (allegedly) in the marriage chamber – died in 1474. A long and inconclusive war of succession ensued, pitting supporters of Henry's 13-year-old heir, Juana de Trastámara, against a faction led by Princess Isabel of Castile and her husband, Ferdinand of Aragon. Portugal, Spain's much smaller antagonist for centuries already, sided with the loyalists.

(Wedding portrait of King Ferdinand II of Aragón and Queen Isabella of Castile.)

The civil war ended in 1480, with the Treaty of Alcáçovas/Toledo, whereby Portugal withdrew support for Juana; in exchange, Isabel and Fernando promised not to encroach on South Atlantic trade routes that Portugal had long been exploring and wished to monopolize.

Treaty Not Worth Much

Spain immediately began to violate the Treaty of Alcáçovas. Portugal's gold trade with Ghana was a powerful enticement, but the Spanish were also lured by the priceless knowledge that Portugal had painstakingly gathered about the currents, territories, winds and heavenly bodies relative to the Atlantic regions. The Portuguese were far advanced in the sciences of geography and navigation pertaining to the Atlantic Ocean, both south and west of Portugal itself.

Meanwhile, João II ascended to the throne of Portugal in 1481, reversing the policies of his father, another weak, late-Medieval ruler who'd surrendered excessive estates and privileges to the nobility. Large swaths of the noble class rebelled, but João II was an astute diplomat, with powerful alliances among the military and religious orders across Europe, along with an extensive network of spies. He sprang a trap on his adversaries, capturing and executing the ring leader.

(João II of Portugal)

Conspiracy!

Queen Isabel supported the traitors in Portugal, having obtained their promise to annul the Treaty of Alcáçovas. When the conspiracy was exposed, numerous traitors among the Portuguese nobility fled to Spain, where they found asylum, along with a base from which to continue their hostilities against João II. Prominent among the defectors were two nephews of the highly-born wife of Christopher Columbus – who would himself sacrifice the next twenty years of his life to join this exodus, faking desertion to his sovereign's most bitter foe. The internecine strife was so keen that after another occasion when his agents had tipped him off, which resulted in João II personally executing the Duke of Viseu, he threatened to charge his own wife with treason for weeping over her brother.

(Christopher Columbus was arrested at Santo Domingo in 1500 by Francisco de Bobadilla and returned to Spain, along with his two brothers, in chains)

The Mother of All Secrets

It's now been amply proven that evidence of hostility between Columbus and João II was fabricated. Columbus was, in fact, a member of João II's inner circle, in addition to being one of the most seasoned of all Portuguese mariners. After his false defection to Spain, Columbus attended three secret meetings with João II, the second of these, in 1488, being prompted by the mother of all maritime secrets: Dias having rounded the Cape of Good Hope, thereby establishing the shortest route to India by sea.

Now, the Holy Grail of all commercial bonanzas was a sea route to the riches of India – sought because Christendom was at war with Islam, and Muslim armies blocked the much shorter land routes across the Middle East. What the most knowledgeable Portuguese pilots knew was top secret, state of the art, a scientific prize for international espionage.

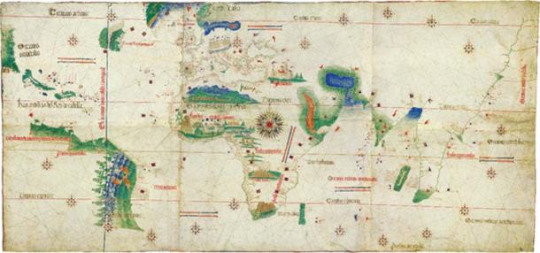

(The Portuguese discovered numerous territories and routes during the 15th and 16th centuries. Cantino planisphere, made by an anonymous cartographer in 1502.)

The Portuguese had been the first Europeans to launch expeditions in search of the Equator, which they reached around 1470, discovering while they were at it, the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe. By 1485, expert Portuguese technicians had invented charts and tables – based on the height of the sun at the Equator – which allowed navigators to determine their location in the daytime. While King João II was keeping Columbus up to date with all of the cutting-edge developments in maritime science, he was at the same time spreading so much disinformation elsewhere—among friends and foes alike— that we are still unraveling it.

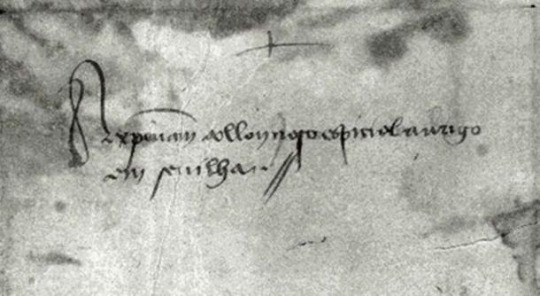

(This secret letter, written by King João II was found in Columbus’ archives. Here is the exterior, addressed in the hand of King João II to, “Xpovam Collon, our special friend in Seville.”)

João II’s agents spent years pursuing the most important traitors across Spain, France and England. With that in view, the following comparison is revealing. Both Columbus and his nephew Don Lopo de Albuquerque (Count of Penamacor) fled Portugal at the same time, took refuge at Isabel's court under false identities, and fostered invasions of the Portuguese Atlantic monopoly from foreign shores. Lopo was tenaciously pursued, finally cornered in Seville and assassinated; in contrast, Columbus disposed of Portuguese secrets, exchanged letters covertly with King João II throughout his eight-year residence in Spain, stopped in Portugal on three of his four voyages, and lied to the Spanish Monarchs about these secret contacts.

A Secret Identity

Christopher Columbus is the garbled pseudonym of a very wellborn, learned, seafaring Portuguese nobleman. The antidote to all subsequent confusion about this man's true identity and character is simply to recognize that the news of his "discovery," which broke like a thunderbolt across the rest of Europe, was in fact nothing more than the release of information that the Portuguese had been hoarding for decades, laced with a linguistic insinuation that Spain had just pioneered the shortest route to India.

Everything Falls into Place

This new perspective on Columbus – as a Portuguese double agent – results in a major paradigm shift. All of the lies perpetrated by Columbus, his family, and the royal chroniclers suddenly begin to make sense as elements in a single, grand design, whose architect was King João II.

It is remarkable that the wave of treasons occurring in Portugal during the mid-1480s – engaging both Queen Isabel and Columbus so deeply – has never been linked by Portuguese historians to the biography of Columbus. Yet, no serious historian today accepts that Columbus was the first European to reach the Americas. There is no excuse any longer for maintaining that he was, or for sustaining the obsolete, pseudo-historical pretense that Columbus invented the idea of sailing west or that he ever really believed he'd landed in India.

(The secret Memorial Portugués, advising Queen Isabel that Portugal engineered the Treaty of Tordesillas specifically to safeguard the best territories for herself. Note how King João II is called (A) “an evil devil,” malvado diablo , and (B) how the “Indies,” Indias”, that Columbus visited are described as NOT the real India)

Having skirted the western lands from Canada to Argentina, the Portuguese understood there were no established commercial ports, no ready-made commercial goods, and was thus no trade potential there to compare with that of India. Columbus – and his many other co-conspirators in Spain, easily identified in retrospect – guarded these secrets faithfully, secrets they had to be privy to if they would guide the Spanish Monarchs to the counterfeit of India. The trade for gold and other goods along the west coast of Africa was immensely profitable, but still more jealously guarded was knowledge that the sea route to India lay also in this direction. The Portuguese were intent on keeping Spanish ships out of these waters. With both war and treaties having failed, João II and Columbus launched an audacious ruse to obtain their objective through less obvious means.

How History is Shaped

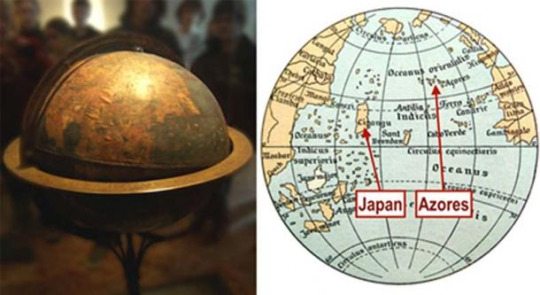

Colossal planning, nerve, and effort went into this accomplishment – seven years of convincing knowledgeable skeptics that the voyage was possible, outfitting a fleet and loading it with merchandise for trade (including cinnamon that would later be presented as evidence of contact with India). On a secret mission to Germany, Martim Behaim, another Templar knight member of the Portuguese Order of Christ, built a false globe based on Toscanelli's theory that East Asia lay just across the Atlantic. This globe still exists; it is the oldest one in the world. Genuine Portuguese traitors warned the Spanish Monarchs that they were being deceived.

(Martin Behaim’s globe intentionally placed the Azores islands, where Behaim lived and was married, on top of the Americas. This made Asia appear much closer to Europe than it really is, thus supporting the project that Columbus was advocating for: Map of Atlantic Ocean)

The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), observed fairly well by both sides, achieved João II's strategic objective: to engage the Spanish in the west while keeping them out of those regions that Portugal wished to dominate. Its effect on the linguistic, racial and cultural substance of an immense portion of the globe has scarcely been rivaled by any other treaty between two nations. No single factor did more to realize this outcome than the erudite seamanship, cunning, ruthless persistence, loyalty and sangfroid of the man whom we still remember today as "Christopher Columbus," a real-life 007, on May 20th, 1506.

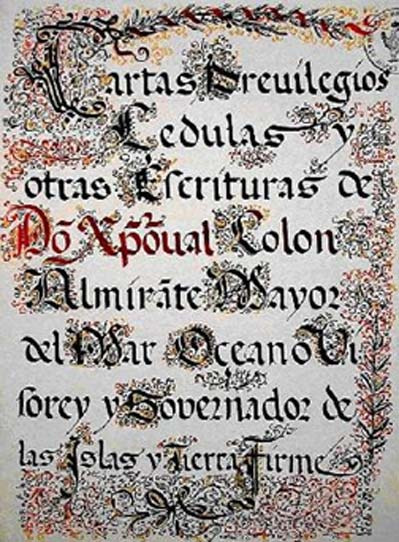

(Cover from the master spy and sailor's Book of Privileges , which clearly shows that the owner's pseudonym was "Colon." An international transmission of the stunning "discovery," in March of 1493, distorted the name in such a fashion as to leave us with "Columbus" in English today. Technically speaking, "Colón" as the Spanish still call him, is correct, and it will someday most likely replace "Columbus" in common usage)

Another particularly factor that King João II knew of existence of land on the west was that when the first Treaty of Tordesilhas came, the line that separate Spain and Portugal territory was just near the Cape Verde territory (already belonging to Portugal). King João II refuse that line and asked for more 370 nautical miles west from that line. The Spanish Monarchs, not knowing anything about the globe, accepted, thinking that it was just more water. When the new Treaty came, the line that King João II asked put Brasil over Portuguese domain. How King João II knew exactly the number of miles to put Brasil in Portugal territory? Because he already knew there was land on the west. The “discovery” of Brasil was NOT an accident.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Study suggests that Flat Eartherism spread via Youtube

The rise in a belief that the Earth is flat is bizarre and somewhat frightening, a repudiation of one of the most basic elements of scientific consensus. Texas Tech University psych researcher Asheley R. Landrum attended a 2017 flat earth convention and interviewed 30 attendees to trace the origins of their belief in a flat earth, finding that Youtube videos were key to their journey into conspiracy theories; her findings were bolstered by a survey of more than 500 participants.

Landrum presented her research at an AAAS meeting a year ago, and it paints a compelling picture of the role Youtube plays in spreading conspiracy theories.

I think that a good model for understanding the spread of these theories needs to also take account of the breakdown of epistemological consensus about how we know things are true.

This breakdown has at least two contributing factors: the first is a decades-long, deliberate campaign to undermine the consensus about how we know things are true, from the denial of the link between cancer and smoking to climate denial. The denial playbook starts with undermining the idea that science produces reliable outcomes, or that a scientific consensus can be trusted.

But denialism is greatly augmented by a legitimate perception of corruption in both expert circles and regulators. The anti-vax movement, for example, relies on two true facts to suggest an untrue conclusion:

* the pharma industry is corrupt and willing to endanger people for profit; and

* regulators are captured by pharma and willing to let them get away with it; therefore

* vaccines can't be trusted.

In a democracy that values free expression, it's hard to imagine how we'll get people to stop saying untrue things (though of course we can tweak our suggestion algorithms to stop prioritizing "engagement," which ends up promoting untrue things).

But we can (and indeed, must) address the legitimate concerns of conspiracy theorists: the ability fo self-dealing, powerful companies to get away with bad acts, and the willingness of regulators to let them.

If you want to learn more about Flat Eartherism, I strongly recommend this interview with Mark Sargent, a notorious Flat Earther, who talked with the skeptical podcast Oh No Ross and Carrie in late 2017. Sargent's frank discussion of his conspiracy theory mindset provides really important insight into an extremely frightening breakdown in reason in our society.

https://boingboing.net/2019/02/18/engagement-maximization-pat.html

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Don’t Talk About the Stories

October 13

Before I start, let's get one thing straight. I'm not the type of person to fall for some run of the mill conspiracy. I don't believe in magic, and I take most things told to me with a truckload of salt. I mean, when you spent a good nine years of your life believing your house was taken over by a secret race of anthropomorphic gloves, you tend to start being a bit skeptical about the world around you.

Having said that, I truly believe my history teacher might be an immortal.

It started off as a joke, one of those blatantly untrue ‘rumors’ everyone spreads to feel like they’re a part of something bigger than themselves. It was somewhere around mid September when we all collectively realized that perhaps we weren’t completely lying to ourselves after all.

Mr. Robert T. Johnson is a quirky man with giant gold-rimmed glasses and a curly beard concealing most of his face. He dresses in vests and bow-ties that come in a variety of earthly tones, and he uses phrases like “that’s so Jake!” - phrases we’re pretty sure no one’s used in over a century.

I want to put a disclaimer here - a disclaimer that is brought on by my confidence in the second paragraph of this entry. Every ‘proof’ I have to offer of the supernatural is purely circumstantial, and can be, in theory, explained in a perfectly rational way.

At any rate, a huge reason why these rumors exist is because of Mr. Johnson’s stories. Every once in a while, he gets a droll look in his eye, and the class always exchanges excited glances. The stories range from the slightly peculiar to the straight up ludicrous, yet every student believes without a doubt that Mr. Johnson actually did punch a Nazi in a French aquarium, or that he actually did date an attractive acrobat who scammed a loan shark out of half a million dollars.

Yet these stories never have any time stamps, and whenever someone inquires Mr. Johnson as to when he actually had time to go on these adventures, he always gets flustered and quickly changes the subject. Pretty soon, we learned not to ask too many questions.

The most notable one of these incidents took place at the concert of some obscure musician with an unfamiliar name. By next period, someone googled the guy. Apparently his last concert was in 1903.

Yet we’d already learned not to ask too many questions, so we left the answers up to our own imaginations. And our imaginations did run wild, leading us to the perhaps slightly irrational conclusion I am sharing with you now.

December 27

My hands are almost shaking as I write this. I wish I didn’t believe the rumor, I wish I could listen to my rational mind. Yet the further I go into the school year, the more I seem to stop listening to logical reasoning of any sort.

The last few months have passed without any major incidents. Mr. Johnson remains as suspicious as ever, although new ‘proof’ has come up. My teacher seems to… imply he knows a lot of languages, as in his stories he regularly talks with residents of other countries. As always, he dodges questions, though. He doesn’t strike me as a language kind of guy, and however many he knows, it’s probably more than an average person learns in a lifetime.

The girl who sits in front of me in homeroom has never talked to me before, but today she leaned back in her chair and rested her elbow on my desk.

“You’re in Mr. Johnson’s class, aren’t you?” she inquired, her voice quivering with excitement. “Here, take a look at what I found while researching my forensics project!”

It was a scan of a news article with a giant picture of a policeman leading a man away in handcuffs. The policeman looked exactly like Mr. Johnson, except clean-shaven and without glasses.

The only problem was that the photo was taken in Ohio, and the policeman was identified as ‘Mr. Green’.

Oh, and it was taken in 1923.

“Mr. Johnson, do you have any ancestors who lived in Ohio?” I asked him at history that afternoon. “A grandfather, perhaps?”

Mr. Johnson stiffened up at the word ‘Ohio’. “Why do you ask?” he inquired, exaggerated nonchalance barely concealing a panicked note in his voice.

“I... was just wondering,” I replied, shifting awkwardly.

“My family did move here from Ohio!” he told me with a hearty laugh, switching to a laid back tone of voice. In a matter of seconds, all his tenseness had evaporated. “How did you find out?”

“A friend of mine was researching for a project,” I blurted without thinking. “She saw a picture of a man who looks just like you in some article about a murder case...”

.

A few days after that, Akane told me the scans had vanished from the internet. As soon as I came home from school that day, I messaged a few of the websites that previously provided the scans, asking them about the disappearance.

.

A few weeks have passed. Not one of them has replied.

February 16

The history teacher next door has left. It happened without any warning, and I am yet to meet a person who isn’t surprised by Mrs. Sheldon’s disappearance. She was an old, sweet lady, someone who has spent a good portion of her life teaching at our school. For her to leave like that, here on Friday and gone on Monday - it greatly disturbed the status quo.

According to the dean, Mrs. Sheldon has grown extremely sick and won’t be able to come to school for a while. She knew neither this mysterious illness nor how long this ‘while’ was going to last.

The new history teacher is a woman in her early to mid thirties, with a round, trustworthy face and strong arms. Her name is Mrs. Merri. She has started to decorate her classroom, the most notable of her posters being a ‘cheat sheet’ on some war we aren’t supposed to learn about until next year.

A girl in my math class was crying because she missed Mrs. Sheldon so much. I feel sorry for her. Fortunately, it doesn’t seem like Mr. Johnson will be leaving anytime soon.

March 24

I have asked around about what Mrs. Merri is like. People seem to have different opinions of her. Most people say she is nice, but some of the more ambitious students complain about how she doesn’t seem to be too experienced in teaching a history class.

People have mostly stopped talking about Mrs. Sheldon. Now, it’s just one of the many interesting things that have happened at my school.

April 2

I usually get a little early to school, and I often hang out in Mr. Johnson’s classroom for ‘tutoring’ until the first bell rings. Today, however, his door was locked and he was nowhere to be seen.

“It seems like Mr. Johnson is running late,” Mr. Merri said. She was leaning on her door frame, smiling openly. “Why don’t you come into my classroom instead?”

“Sure,” I shrugged, glancing behind her into the open room. Almost a dozen students sat at the desks, pouring over textbooks or conversing in hushed voices. I recognized Akane, as well as some other kids who I usually saw in Mr. Johnson’s class.

I took a seat next to Akane and pulled out my phone. For a while, we all worked in relative silence.

“I see a lot of unfamiliar faces today,” Mrs. Merri remarked at some point. She was perched, nonchalantly, on her desk, gazing over us in amusement. “Don’t tell me Mr. Johnson always gets this much more students in the mornings.”

Someone assured her this was an unusually busy day.

“He seems to be a good guy,” she continued. “I’d like to get to know him better. Does he tell you guys stories in his class? Because I’ve only spent a few days talking to him and I’ve already heard he’s been all over the world. Asia, Africa, Europe… And he’s been all over the US as well. Has he ever told you guys about Ohio?”

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Akane freeze up mid-page turn.

“Not really,” I said nonchalantly. “He’s mentioned vacations in different countries, but you make it seem like he’s some sort of world traveler. I certainly don’t remember anything about Ohio.”

I remembered a rumor about how some girl saw Mrs. Sheldon in a grocery store recently looking very healthy and very much not like a person who has to leave school because of a mysterious illness.

“He doesn’t really tell stories,” Akane picked up. “He’s honestly a reserved kind of guy when he teaches our class.”

The rumors about Mr. Johnson’s mysterious past, Mrs. Sheldon’s sudden disappearance and quick replacement, the absolute confidence with which Akane and I delivered our lies - all of these things led a few of the other kids in the classroom to slowly nod their agreement.

Mrs. Merri regarded us with a cold, skeptical stare. Now she didn’t seem so friendly anymore. “So he’s told you… nothing? Nothing about his personal life at all?”

“Honestly, yeah,” said someone to my left. “I wish he’d tell more stories.”

“Mr. Johnson’s traveled across Europe?” piped up a boy in the front. “That’s amazing! Could you tell us more?”

Mrs. Merri let the topic evaporate, and in less than a minute the first bell rung. I’m going to tell Mr. Johnson about this, Akane told me under her breath as we filed out of the door.

Mr. Johnson did not tell our class any stories that day.

June 12

The next day, Mr. Johnson did not show up to class.

We later found out he had left a note of resignation on the principal’s desk the afternoon of the incident. He didn’t answer his email, and his phone went straight to voicemail no matter who called him or when they did it. Most of his belongings were left in the classroom, never to be picked up again, which would’ve been cause for alarm if it wasn’t for the disappearance of a whole row of books on his bookshelf, a whole row of books we knew Mr. Johnson cherished dearly.

So wherever he left, he left of his own accord.

A few days later, Mrs. Merri was replaced by Mrs. Sheldon again. Any questions about her alleged illness were avoided by both her and the school staff.

Now, more than ever, I suspect that both Mrs. Merri and Mr. Johnson have giant secrets. I don’t think I’ll ever find out, though.

I never saw either of them again.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forced to Choose Between Trump’s “Big Lie” and Liz Cheney, the House G.O.P. Chooses the Lie

“Liz is a living reproach to all these cowards,” a friend of Cheney’s said, but the cowards have the votes.

— By Susan B. Glasser | May 6, 2021 | The New Yorker

Liz Cheney standing in front of the U.S. Capitol building.

It has become abundantly clear that House Republicans will soon throw Liz Cheney out of her leadership position for refusing to go along with Trump’s falsehoods.Photograph by Drew Angerer / Getty

On January 11, 2017, Donald Trump held his first Presidential press conference following his upset victory in the November, 2016, election. It was anything but Presidential. In perhaps the day’s most notable exchanges, he attacked BuzzFeed for publishing a former British spy’s unverified dossier on his extensive ties to Russia—the news organization, Trump said, was a “failing pile of garbage.” He also singled out CNN and its White House correspondent, Jim Acosta, for particular scorn. “You’re fake news!” Trump raged at Acosta, refusing to take a question from him. It was his first spoken utterance of a phrase that, arguably more than any other, would come to be associated with his Presidency.

It was also, and more to the point, an act of shameless linguistic larceny. In the two months since Trump’s upset win, the “fake news” conversation had been all about the weaponization of falsehoods by Trump and for his political benefit. On November 3rd, a few days before the 2016 election, Craig Silverman—a BuzzFeed reporter who had first regularly started using the term in 2014, in research papers and articles—broke a story about fake-news troll farms in Macedonia that had been spreading lies on Trump’s behalf to American voters on Facebook. When Trump actually won the election, the idea that fake news promoted by hidden forces had contributed to his unlikely victory went viral. In that January press conference, Trump appropriated the phrase for himself, this time as an attack on his critics, a move of political jiu-jitsu that proved to be stunningly effective. I spoke with Silverman the other day about the moment that “fake news” stopped being his label and became Donald Trump’s. “He decided to take it and turn it into his term, and to take ownership of it and use it as a cudgel to beat the media,” Silverman told me. “And I think it proved to be one of his favorite phrases, and probably one of his most effective phrases, too, over the course of his Presidency.”

All week long, I’ve been thinking about that moment four years ago. This Monday, Trump sent out a short statement, the kind that he would have tweeted out before his falsehoods about the recent election got him banned from Twitter. In it, he said, “The Fraudulent Presidential Election of 2020 will be, from this day forth, known as the big lie!” Soon after that, Liz Cheney, the No. 3 House Republican leader, sent out an actual tweet refusing to accept this Trumpian redefinition of truth. “The 2020 presidential election was not stolen,” she wrote. “Anyone who claims it was is spreading the big lie.” Anyone who has followed the past four years in the Republican Party, however, can tell you what happened next: the Party did not turn on Donald Trump for his outrageous inversion of truth but on Liz Cheney. Within a couple of days, it had become abundantly clear that House Republicans would soon throw Cheney out of her leadership position for refusing to go along with Trump’s big lie about the Big Lie.

Trump has learned the lesson of previous demagogues: the bigger and more flagrant the untruth, the better to prove the fealty of his Party. After all, it actually demands more loyalty to follow your leader into an absurd conspiracy theory than it does to toe the official line when it doesn’t require a mass suspension of disbelief. Back in January, the Big Lie had been rightly affixed to Trump’s preposterous falsehoods about the “rigged election” and his followers’ insurrection, on January 6th, to prevent Congress from certifying the results. His claims were so preposterous that a lawyer who advanced them on Trump’s behalf, Sidney Powell, is now defending herself in court with a filing that states “no reasonable person would conclude that the statements were truly statements of fact.” There was no fraud. Or, as Trump might put it, if he weren’t lying about it, “no fraud!” And yet Trump has successfully proved throughout the past few months that the repetition of these lies over and over again—even without accompanying evidence—is more than enough to get millions of Americans to believe him. He has run this play before. He knows that it works. Fake News indeed.

The striking difference is that, this time, Liz Cheney has chosen to fight him on it. If Trump does manage to reinvent “the Big Lie” in service of his own corrupt ends, Cheney will at least have forced members of her party into admitting, on the record, that they are making a choice between truth and Trump’s untruth—and choosing the latter. There is no hope among her supporters and advisers that she will win the fight, when the House Republican Conference votes, likely next week, to boot her. Instead, there is a recognition that Cheney has finally decided to do what most of the Trump skeptics within the Party were reluctant to for four years: publicly challenge not only Trump’s lies but the enablers within the G.O.P. who give his lies such power. “It’s all got to do with fealty to Trump and the Big Lie and the fact that Liz is a living reproach to all these cowards,” Eric Edelman, a friend of Cheney’s who served as a national-security adviser to her father, former Vice-President Dick Cheney, told me.

Cheney’s rupture with the House Republican Conference has become all but final in recent days, but it has been months in the making. Edelman revealed that Cheney herself secretly orchestrated an unprecedented op-ed in the Washington Post by all ten living former Defense Secretaries, including her father, warning against Trump’s efforts to politicize the military. The congresswoman not only recruited her father but personally asked others, including Trump’s first Defense Secretary, Jim Mattis, to participate. “She was the one who generated it, because she was so worried about what Trump might do,” Edelman said. “It speaks to the degree that she was concerned about the threat to our democracy that Trump represented.” The Post op-ed appeared on January 3rd, just three days before the insurrection at the Capitol.

Little noticed at the time was another Cheney effort to combat Trump’s post-election lies, a twenty-one-page memo written by Cheney and her husband, Phil Perry, an attorney, and circulated on January 3rd to the entire House Republican Conference. In it, Cheney debunked Trump’s false claims about election fraud and warned her colleagues that voting to overturn the election results, as Trump was insisting, would “set an exceptionally dangerous precedent.” But, of course, they did not listen. Even after the storming of the Capitol, a hundred and forty-seven Republican lawmakers voted against accepting the election results. When Trump was later impeached over his role in inciting the insurrection, Cheney was one of just ten House Republicans to vote in favor of it.

Revealingly, it is not Cheney’s impeachment vote that now looks like the move to get her bounced from the Party’s leadership. It is her refusal to shut up about it and embrace the official party line of forgetting about Trump’s attack on democracy and moving on—which is the approach of all but a handful of prominent Republicans. Even former Vice-President Mike Pence, who was forced by a pro-Trump mob to flee for his life on January 6th, after he refused Trump’s demand that he block congressional certification of the election results, is back to public deference. At an appearance last week, Pence called his service to Trump “the greatest honor” of his life.

So, too, is Kevin McCarthy, the House Minority Leader, who made a frantic phone call to Trump on January 6th seeking his help in stopping the mob. McCarthy was angry enough days later that he gave a speech on the House floor saying unequivocally that Trump “bears responsibility” for the Capitol attack. But McCarthy, like Pence, has returned to his safe space of Trump sycophancy. In recent days, McCarthy has made clear that the effort to dump Cheney has his support, as well as Trump’s. Various media accounts have suggested that he was personally angered that Cheney had not been more grateful when he intervened to help save her leadership job following her impeachment vote. The bad feelings are clearly mutual in Cheneyworld. “You have to surround the Big Lie with a bodyguard of lies,” Edelman told me, of McCarthy, paraphrasing Churchill.

Four years ago, back when Trump was turning “fake news” into his own hypocritical rallying cry, Cheney and other members of the conservative Republican establishment were in what appeared to be hold-their-noses-and-deal-with-him mode. Most of them went on to become vocal Trump cheerleaders. A few others, such as former House Speaker Paul Ryan, decided to leave the public stage altogether rather than take Trump on. The loudest anti-Trump voice in the G.O.P. in 2017, the Arizona senator John McCain, died of brain cancer the following year. Mitt Romney, who won election to the Senate from Utah a couple of months after McCain’s death, became essentially a lone Republican voice of public opposition to Trump on Capitol Hill. Cheney, from the rabidly pro-Trump state of Wyoming, stayed largely silent until the outrages of 2020 began to pile up.

It took a long time, but arguably Liz Cheney today is McCain’s heir. She is, at the last, willing to call a lie a lie. She applied “the Big Lie” to Trump’s crimes against American democracy long before Trump sought, this week, to steal the phrase for his own destructive purposes. But there is one matter about which I must disagree. In a scathing opinion article she published on the Post’s Web site Wednesday night, Cheney wrote that she will not back down from this fight because it is a “turning point” for her party, which will show whether Republicans “choose truth and fidelity to the Constitution” or the “dangerous and anti-democratic Trump cult of personality.” She is wrong about this one. The choice has already been made.

— Susan B. Glasser is a staff writer at The New Yorker, where she writes a weekly column on life in Washington. She co-wrote, with Peter Baker, “The Man Who Ran Washington.”

0 notes

Text

The types of electoral misinformation

By Kate Starbird and Jevin West, University of Washington, and Renee DiResta, Stanford University

When there’s no clear winner in a presidential election, there’s an opportunity for partisan activists, conspiracy theorists and others to exploit public uncertainty and anxiety to attempt to delegitimise the election results.

A growing number of narratives alleging electoral wrongdoing have been spreading on social media, shared through millions of tweets, Facebook posts and TikTok videos, often using hashtags like #riggedelection and #StopTheSteal. These types of narratives rely on “evidence” of ballots that are lost or found after the election, dubious statistics, misleading videos and allegations of foreign interference. People seeking to delegitimise election results are weaving real-world events, such as isolated confrontations with poll workers or broken voting machines, into claims of broader malfeasance by nefarious partisans on one side or the other.

As members of the Election Integrity Partnership and researchers who study online misinformation and disinformation, we have been monitoring social media. We are seeing five types of false and misleading narratives that people are spreading and are likely to spread online, wittingly or not. We urge people to be alert for – and to avoid spreading – the following types of misinformation, which erode trust in the electoral process and in one another.

1. Attempts to sow confusion and doubt

The wait for election results has been a stressful one. During times of uncertainty and anxiety, people are vulnerable to misinformation and manipulation.

Because of significant increases in the number of mail-in ballots in many states and unevenly timed processes for counting mail-in, early in-person and Election Day in-person ballots, even experts are struggling to make predictions and understand how remaining votes may line up. This lack of understanding and certainty can fuel doubt, fan misinformation and provide opportunities for those seeking to delegitimise the results.

As the vote counts come in and vote shares shift, some “influencers” – people with many followers in the media and on social media – have been questioning, with dubious evidence, the results and the voting process in battleground states. For example, images purporting to show people moving ballots in nefarious ways have gone viral – one turned out to be a poll worker moving ballots in an official capacity, and another turned out to be a photographer transporting equipment. There have also been several disputed claims that sudden increases in votes for one candidate indicate voter fraud.

2. “Evidence” of voter fraud

Many people have documented and shared their experiences at the polls on Election Day. Though the vast majority were uneventful, some showed isolated issues. Similarly, some stories in local news outlets and on social media showed isolated problems with mail-in ballots and voting at polling stations. Politically motivated individuals are likely to cherry-pick and assemble these pieces of digital “evidence” to fit narratives that seek to undermine trust in the results.

Much of this evidence is likely to be derived from real events, though taken out of context and exaggerated. As the race begins to focus in on a small number of states where the vote margin is slim, we expect to see cases of an incident in one place used to support false claims of fraud in another place.

A narrative that emerged on Election Day – and that continues to spread – falsely claims that poll workers provided some voters with pencils or Sharpie pens that would have rendered their ballots unreadable by the voting machines, thus nullifying some Trump supporters’ votes. There were more than 160,000 tweets and retweets that used the terms “Sharpies,” “felt tip” or “Sharpiegate” over the course of Nov. 4. The false claims quickly moved into the offline world. They were echoed by Trump supporters protesting in Maricopa County, Arizona, that evening, and Fox News reported that the state attorney general’s office was “investigating” the matter.

3. Ballots “found,” ballots “lost”

One of the most dominant narratives on the political right is likely to be Democratic activists or officials forging votes or faking vote totals to make up ground after the polls closed. This is a conspiracy theory that was alluded to by President Trump on election night, when he claimed to fear that ballots might be “found” at four o’clock in the morning and “added to the list.”

False claims of found ballots in Georgia emerged on Twitter on Nov. 4 and were amplified by Donald Trump Jr. On Nov. 5 Facebook banned a group called Stop The Steal for violating the platform’s policies. The group had been promoting conspiracy theories about ballots and organising protests.

Twitter has been flagging false and misleading tweets like this claim that ballots in Georgia were created after polls closed. Screen capture by Kate Starbird, University of Washington, CC BY-NC-ND

False claims that nefarious poll workers or activists destroyed, discarded or intentionally mislaid Republican ballots, or replaced them with fake Democratic ones, could also be woven into this narrative.

We expect people seeking to delegitimise election results to promote this theory using a number of interlinking elements. They are likely to frame statistical shifts and the fixing of reporting errors as post-election ballot stuffing – for example, the recent false claim that votes had “magically” appeared for Biden overnight in Michigan. The reality in this case was an error in a file the state sent to a media outlet. The theory is likely to also focus on chain-of-custody events, to create the impression that ballots could be added or swapped.

Together, purported anomalies in statistics, local news reports about misplaced ballots and occasional video of alleged ballot mistreatment could be used to form a greater narrative of a vast, multilevel institutional conspiracy. Since modern conspiracy theories are relatively omnivorous, even tangential elements such as the Sharpiegate claim could be folded into this broader story.

4. Bad projections

Even the best election models are often wrong. Inaccurate projections, which can be intentionally or accidentally wrong, can be picked up and used to contest results that conflict with the projection or cast doubt on the process as a whole. Early projections by Fox News and the AP of Biden winning Arizona appear to have been premature given the closeness of the race there, and if the final tally moves in Trump’s favor it could fuel criticism about an unfair process. Trump supporters protesting in Maricopa County on Nov. 4 expressed anger at Fox News for its Arizona call.

Two complicating factors in the 2020 election are that the polls are quite different from the actual vote share, and that the scale and demographics of mail-in voting, which skews Democratic, have complicated traditional models for projecting victory.

youtube

Red shifts and blue shifts – when vote tallies shift from one candidate to the other as votes are counted – are common, but that hasn’t stopped purveyors of misinformation from citing them to falsely claim fraud.

These conditions, along with close margins in several states, have made it more difficult to project winners for several races. The longer periods of uncertainty create more opportunity for misinformation to spread.

5. Premature claims to victory

Early in the morning of Nov. 4, not long after polls closed at the end of Election Day, President Trump made a speech in which he falsely asserted that he had won the election. Later in the day he followed up with a tweet claiming victory in specific states, including Pennsylvania, where election officials were still counting votes and no reputable news organisation had called the race.

These premature and potentially inaccurate claims of victory again set the stage for arguing that conflicting results are somehow fraudulent or reflect a “rigged” election. This argument could advance the objectives of a political candidate and appeal to his supporters, but it can also undermine trust that the electoral process is fair.

Shoring up the foundations of democracy

Political misinformation destabilises the foundations of democracy, causing people to lose trust in democratic processes, information providers and, ultimately, one another.

We are working to better understand these dynamics and identify ways to counter them, with the aim of helping people become more resistant to manipulation. Our advice is to remain skeptical of claims about the election that haven’t been confirmed by reliable sources and to think before liking, retweeting or sharing.

Michael Caulfield, Director of Blended and Networked Learning at Washington State University Vancouver, contributed to this article.

Kate Starbird, Associate Professor of Human Centered Design & Engineering, University of Washington; Jevin West, Associate Professor and Director of the Center for an Informed Public, University of Washington, and Renee DiResta, Research Manager of the Stanford Internet Observatory, Stanford University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The types of electoral misinformation published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Link

Influential yoga teachers denounce the conspiracy theory, which has infiltrated spiritual communities, and offer advice on how to identify and stop the spread of misinformation

QAnon, the viral pro-Trump conspiracy theory alleging that a band of satan-worshipping pedophiles, is gaining steam in the yoga and wellness community.

On social media, some teachers and influencers are posting QAnon-related messaging—although it doesn't always explicitly mention QAnon by name. On pastel backgrounds and in pretty fonts they call COVID-19 a hoax, encourage gun ownership, warn about human trafficking, and celebrate Donald Trump as a “light worker” in his quest to “save the children.”

Yoga teachers including Hala Khouri and Seane Corn—cofounders of the yoga and social justice organization Off the Mat, Into the World—started seeing posts like these in their feeds near the beginning of the Coronavirus lockdown this spring. Khouri has said she believes the debunked viral documentary Plandemic, which spread misinformation about COVID-19, was an entry point to QAnon for many in the wellness community. (The documentary was removed by both Facebook and YouTube in May.)

In March, celebrity OB/GYN Christiane Northrup, MD, started sharing QAnon-related "save the children" messaging, along with videos and memes that disparage vaccines and mask-wearing and encourage distrust of mainstream media. Northrup also shared Plandemic with her more than 750,000 followers on social media.

In an interview with Jezebel, Khouri discussed how she was “slammed” by many members of her Facebook community when she questioned the veracity of the documentary. Soon after, an explosion of posts pushing back on mask-wearing and a proliferation of memes warning of a government-led holocaust via vaccine flooded her feeds.

see also Do Politics Belong in Yoga?

Yoga Teachers and Wellness Leaders Respond to QAnon

Khouri, Corn, and other high-profile members of the wellness community like Jeff Krasno, the creator of the yoga festival Wanderlust and now the director of Commune—a wellness video and podcasting platform—were so disturbed by QAnon’s allegations that they were moved to publicly denounce it.

On September 13, Corn posted this statement, created by a concerned group of yoga and wellness leaders, to her 108,000 followers on Instagram:

View the original article to see embedded media.

Corn told Yoga Journal that she believes QAnon messaging is manipulative and exploitative—designed to incite chaos and division in the lead-up to the upcoming presidential election. “I just wanted to alert people that QAnon is a cult and it’s dangerous and it’s got its roots in white supremacy culture,” says Corn. “People should be aware of misinformation that is being targeted directly at the wellness community.”

By the end of September, Corn’s post had around 10,000 likes. After accruing thousands of comments, many from QAnon supporters spreading disinformation, Corn decided to disable comments on September 24. “As much as I may have helped people to gain awareness, I may have also introduced people to QAnon theories and beliefs,” she said.

see also 8 Steps Yogis Can Take to Turn Political Anxiety Into Mindful Activism

The Roots of QAnon

According to believers of QAnon, the leaders of the cabal consist of top democrats and liberal entertainers; dark forces who threaten humanity. “Q” is the name of a supposed high-clearance intelligence officer who drops cryptic messages about the cabal on various websites.

According to The New York Times, Q has “dropped” almost 5,000 messages so far, many repeating warnings about satanic rituals that have previously made their way into mainstream culture: If you lived through the 80s, you might remember evening news stories claiming Satanists were infiltrating daycares and schools to abuse children. Another QAnon claim, that cabal members kill and eat children to gain special powers from their blood, is a recycled Blood Libel conspiracy theory rooted in anti-semitism from the turn of the Twentieth Century, which helped to fuel Nazism across the world.

Conspirituality

Why are some members of the spiritual community putting stock in this conspiracy theory?

Two of the issues QAnon distorts—child abuse and human trafficking—are legitimate concerns, and many in the wellness community, including Corn, feel passionately about stopping them. (Corn has been working to fight human trafficking for decades. She recommends a few organizations that she’s personally cooperated with in both the United States and India: Children of the Night and Apne App.)

More generally, spiritual seekers are attracted to the idea of hidden and secret knowledge, and the existence of a grand cosmic plan, according to British writer and philosopher Jules Evans, who’s written extensively about the intersection of mysticism and conspiracy theories. “People prone to spiritual experiences may also be prone to unusual beliefs like conspiracy theories, which could be described as a paranoid version of a mystical experience,” Evans says.

“Conspirituality” is a term that was used by academic Charlotte Ward in 2011 in the Journal of Contemporary Religion. It is described as a “a rapidly growing web movement expressing an ideology fueled by political disillusionment and the popularity of alternative worldviews.”

Conspirituality is also a podcast, hosted by Derek Beres, Julian Walker, and Matthew Remski, that explores the cult-like behavior of QAnon and its theories.

see also 11 Yoga Practices for Working Through Stress and Anxiety

How to Spot QAnon, Protect Yourself from Disinformation, and Respond

In an interview with cult survivor and researcher Remski on the Conspirituality Podcast, Corn warned of the dangers of “Pastel QAnon” and their pleas to “protect children.” If you look closely, you might see QAnon hashtags attached to the posts, mixed in with other hashtags used by anti-trafficking campaigns: #savethechildren, #endsextrafficking, #eyeswideopen, #thegreatawakening, #dotheresearch, #followthewhiterabbit. (See a list of QAnon terminology here, compiled by the Conspirituality Podcast.)

According to Evans, “We need to learn how to balance our intuition with critical thinking, otherwise we can fall prey to ideas which are bad for us and our networks.”

If you see QAnon-related posts in your social feeds and want to start a conversation with the person who posted, Krasno recommends avoiding posting in their comments, as that can give the post more weight and help it spread further. He also recommends avoiding using words like ‘conspiracy’ or ‘conspirituality.’ “[These words] immediately cast any sort of skepticism in a negative light, and many conspiracies have been proven through hard-nosed journalism, including theories about Jeffrey Epstein, Watergate, and child sex trafficking,” he says. The word conspiracy can put people on the defensive and erode the common ground you are trying to create in an effort to bridge your worldview with others’, he explains. “You also have to be sensitive to the fact that some folks who support QAnon are survivors of sex trafficking and abuse,” says Krasno. “And now they feel heard, and have agency and community.”

see also A Sequence for Building Resilience in This Political Climate

When Krasno does engage with members of his community posting QAnon messages, he tries to frame his responses around discernment and media literacy, asking them if they know the source of the information they are sharing and whether it is reliable—whether it meets journalistic standards, has come from multiple expert sources, and was fact-checked.

“I remind myself that we are all susceptible to being imperceptibly influenced by misinformation, and then I ask others to be aware of that as well,” Krasno says. If your own opinions have changed over the last several months, he suggests asking yourself why. “One of the hardest things in the world now is to differentiate fact from fiction,” he says, especially when misinformation is prolific online.

“I also challenge people to get off of social media for a day, or even a week, to see how they feel,” Krasno adds. “The goal of QAnon and other similar movements is to propagate chaos by constantly agitating people, tapping into sympathetic nervous system responses that inspire you to fight. When people get off of social media for a while, they usually feel better, more relaxed, and happier.”

see also A Yoga Sequence to Train Your Brain to Relax

0 notes

Text

I am posting a series of articles on the misinformation campaign being waged by the Trump campaign and other nafarious actors including Russia, Iran and China..Its important we recognize, educate and share this information ahead of the 2020 election. The misinformation is 20 fold to the misinformation campaign waged in 2016. WE MUST DEFEAT DONALD TRUMP FOR THE SAKE OF OUR DEMOCRACY. PLEASE SHARE!!! TY🙏🏻🙏🙏🏼🙏🏽🙏🏾🙏🏿

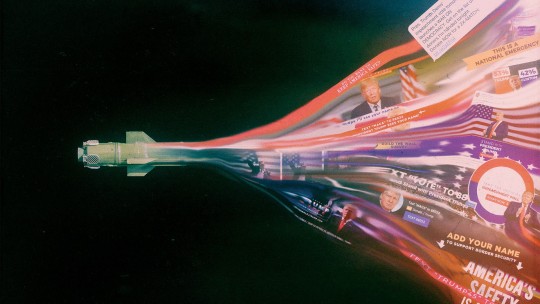

THE BILLION-DOLLAR DISINFORMATION CAMPAIGN TO REELECT THE PRESIDENT..... How new technologies and techniques pioneered by dictators will shape the 2020 Election

By McKay Coppins | Published MARCH 2020 Issue | The Atlantic Magazine | Posted February 13, 2020 |

(**Updated at 2:30 p.m. ET on February 10, 2020.)

(PART 1 /2)

One day last fall, I sat down to create a new Facebook account. I picked a forgettable name, snapped a profile pic with my face obscured, and clicked “Like” on the official pages of Donald Trump and his reelection campaign. Facebook’s algorithm prodded me to follow Ann Coulter, Fox Business, and a variety of fan pages with names like “In Trump We Trust.” I complied. I also gave my cellphone number to the Trump campaign, and joined a handful of private Facebook groups for MAGA diehards, one of which required an application that seemed designed to screen out interlopers.

The president’s reelection campaign was then in the midst of a multimillion-dollar ad blitz aimed at shaping Americans’ understanding of the recently launched impeachment proceedings. Thousands of micro-targeted ads had flooded the internet, portraying Trump as a heroic reformer cracking down on foreign corruption while Democrats plotted a coup. That this narrative bore little resemblance to reality seemed only to accelerate its spread. Right-wing websites amplified every claim. Pro-Trump forums teemed with conspiracy theories. An alternate information ecosystem was taking shape around the biggest news story in the country, and I wanted to see it from the inside.

The story that unfurled in my Facebook feed over the next several weeks was, at times, disorienting. There were days when I would watch, live on TV, an impeachment hearing filled with damning testimony about the president’s conduct, only to look at my phone later and find a slickly edited video—served up by the Trump campaign—that used out-of-context clips to recast the same testimony as an exoneration. Wait, I caught myself wondering more than once, is that what happened today?

As I swiped at my phone, a stream of pro-Trump propaganda filled the screen: “That’s right, the whistleblower’s own lawyer said, ‘The coup has started …’ ” Swipe. “Democrats are doing Putin’s bidding …” Swipe. “The only message these radical socialists and extremists will understand is a crushing …” Swipe. “Only one man can stop this chaos …” Swipe, swipe, swipe.

I was surprised by the effect it had on me. I’d assumed that my skepticism and media literacy would inoculate me against such distortions. But I soon found myself reflexively questioning every headline. It wasn’t that I believed Trump and his boosters were telling the truth. It was that, in this state of heightened suspicion, truth itself—about Ukraine, impeachment, or anything else—felt more and more difficult to locate. With each swipe, the notion of observable reality drifted further out of reach.

What I was seeing was a strategy that has been deployed by illiberal political leaders around the world. Rather than shutting down dissenting voices, these leaders have learned to harness the democratizing power of social media for their own purposes—jamming the signals, sowing confusion. They no longer need to silence the dissident shouting in the streets; they can use a megaphone to drown him out. Scholars have a name for this: censorship through noise.

After the 2016 election, much was made of the threats posed to American democracy by foreign disinformation. Stories of Russian troll farms and Macedonian fake-news mills loomed in the national imagination. But while these shadowy outside forces preoccupied politicians and journalists, Trump and his domestic allies were beginning to adopt the same tactics of information warfare that have kept the world’s demagogues and strongmen in power.

Every presidential campaign sees its share of spin and misdirection, but this year’s contest promises to be different. In conversations with political strategists and other experts, a dystopian picture of the general election comes into view—one shaped by coordinated bot attacks, Potemkin local-news sites, micro-targeted fearmongering, and anonymous mass texting. Both parties will have these tools at their disposal. But in the hands of a president who lies constantly, who traffics in conspiracy theories, and who readily manipulates the levers of government for his own gain, their potential to wreak havoc is enormous.

The Trump campaign is planning to spend more than $1 billion, and it will be aided by a vast coalition of partisan media, outside political groups, and enterprising freelance operatives. These pro-Trump forces are poised to wage what could be the most extensive disinformation campaign in U.S. history. Whether or not it succeeds in reelecting the president, the wreckage it leaves behind could be irreparable.

'THE DEATH STAR'

The campaign is run from the 14th floor of a gleaming, modern office tower in Rosslyn, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C. Glass-walled conference rooms look out on the Potomac River. Rows of sleek monitors line the main office space. Unlike the bootstrap operation that first got Trump elected—with its motley band of B-teamers toiling in an unfinished space in Trump Tower—his 2020 enterprise is heavily funded, technologically sophisticated, and staffed with dozens of experienced operatives. One Republican strategist referred to it, admiringly, as “the Death Star.”

Presiding over this effort is Brad Parscale, a 6-foot-8 Viking of a man with a shaved head and a triangular beard. As the digital director of Trump’s 2016 campaign, Parscale didn’t become a household name like Steve Bannon and Kellyanne Conway. But he played a crucial role in delivering Trump to the Oval Office—and his efforts will shape this year’s election.

In speeches and interviews, Parscale likes to tell his life story as a tidy rags-to-riches tale, embroidered with Trumpian embellishments. He grew up a simple “farm boy from Kansas” (read: son of an affluent lawyer from suburban Topeka) who managed to graduate from an “Ivy League” school (Trinity University, in San Antonio). After college, he went to work for a software company in California, only to watch the business collapse in the economic aftermath of 9/11 (not to mention allegations in a lawsuit that he and his parents, who owned the business, had illegally transferred company funds—claims that they disputed). Broke and desperate, Parscale took his “last $500” (not counting the value of three rental properties he owned) and used it to start a one-man web-design business in Texas.

Parscale Media was, by most accounts, a scrappy endeavor at the outset. Hustling to drum up clients, Parscale cold-pitched shoppers in the tech aisle of a Borders bookstore. Over time, he built enough websites for plumbers and gun shops that bigger clients took notice—including the Trump Organization. In 2011, Parscale was invited to bid on designing a website for Trump International Realty. An ardent fan of The Apprentice, he offered to do the job for $10,000, a fraction of the actual cost. “I just made up a price,” he later told The Washington Post. “I recognized that I was a nobody in San Antonio, but working for the Trumps would be everything.” The contract was his, and a lucrative relationship was born.

Over the next four years, he was hired to design websites for a range of Trump ventures—a winery, a skin-care line, and then a presidential campaign. By late 2015, Parscale—a man with no discernible politics, let alone campaign experience—was running the Republican front-runner’s digital operation from his personal laptop.

Parscale slid comfortably into Trump’s orbit. Not only was he cheap and unpretentious—with no hint of the savvier-than-thou smugness that characterized other political operatives—but he seemed to carry a chip on his shoulder that matched the candidate’s. “Brad was one of those people who wanted to prove the establishment wrong and show the world what he was made of,” says a former colleague from the campaign.

Perhaps most important, he seemed to have no reservations about the kind of campaign Trump wanted to run. The race-baiting, the immigrant-bashing, the truth-bending—none of it seemed to bother Parscale. While some Republicans wrung their hands over Trump’s inflammatory messages, Parscale came up with ideas to more effectively disseminate them.

The campaign had little interest at first in cutting-edge ad technology, and for a while, Parscale’s most valued contribution was the merchandise page he built to sell MAGA hats. But that changed in the general election. Outgunned on the airwaves and lagging badly in fundraising, campaign officials turned to Google and Facebook, where ads were inexpensive and shock value was rewarded. As the campaign poured tens of millions into online advertising—amplifying themes such as Hillary Clinton’s criminality and the threat of radical Islamic terrorism—Parscale’s team, which was christened Project Alamo, grew to 100.

Parscale was generally well liked by his colleagues, who recall him as competent and intensely focused. “He was a get-shit-done type of person,” says A. J. Delgado, who worked with him. Perhaps just as important, he had a talent for ingratiating himself with the Trump family. “He was probably better at managing up,” Kurt Luidhardt, a consultant for the campaign, told me. He made sure to share credit for his work with the candidate’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and he excelled at using Trump’s digital ignorance to flatter him. “Parscale would come in and tell Trump he didn’t need to listen to the polls, because he’d crunched his data and they were going to win by six points,” one former campaign staffer told me. “I was like, ‘Come on, man, don’t bullshit a bullshitter.’ ” But Trump seemed to buy it. (Parscale declined to be interviewed for this story.)

James Barnes, a Facebook employee who was dispatched to work closely with the campaign, told me Parscale’s political inexperience made him open to experimenting with the platform’s new tools. “Whereas some grizzled campaign strategist who’d been around the block a few times might say, ‘Oh, that will never work,’ Brad’s predisposition was to say, ‘Yeah, let’s try it.’ ” From June to November, Trump’s campaign ran 5.9 million ads on Facebook, while Clinton’s ran just 66,000. A Facebook executive would later write in a leaked memo that Trump “got elected because he ran the single best digital ad campaign I’ve ever seen from any advertiser.”