#Steampunk Decolonial

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I am once again posting the solarpunk manifesto because I keep seeing people saying that solarpunk is just an aesthetic

Inspired by Solarpunk: A Reference Guide and Solarpunk: Notes Towards a Manifesto

A Solarpunk Manifesto

Solarpunk is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion, and activism that seeks to answer and embody the question “what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there?”

The aesthetics of solarpunk merge the practical with the beautiful, the well-designed with the green and lush, the bright and colorful with the earthy and solid.

Solarpunk can be utopian, just optimistic, or concerned with the struggles en route to a better world , but never dystopian. As our world roils with calamity, we need solutions, not only warnings.

Solutions to thrive without fossil fuels, to equitably manage real scarcity and share in abundance instead of supporting false scarcity and false abundance, to be kinder to each other and to the planet we share.

Solarpunk is at once a vision of the future, a thoughtful provocation, a way of living and a set of achievable proposals to get there.

We are solarpunks because optimism has been taken away from us and we are trying to take it back.

We are solarpunks because the only other options are denial or despair.

At its core, Solarpunk is a vision of a future that embodies the best of what humanity can achieve: a post-scarcity, post-hierarchy, post-capitalistic world where humanity sees itself as part of nature and clean energy replaces fossil fuels.

The “punk” in Solarpunk is about rebellion, counterculture, post-capitalism, decolonialism and enthusiasm. It is about going in a different direction than the mainstream, which is increasingly going in a scary direction.

Solarpunk is a movement as much as it is a genre: it is not just about the stories, it is also about how we can get there.

Solarpunk embraces a diversity of tactics: there is no single right way to do solarpunk. Instead, diverse communities from around the world adopt the name and the ideas, and build little nests of self-sustaining revolution.

Solarpunk provides a valuable new perspective, a paradigm and a vocabulary through which to describe one possible future. Instead of embracing retrofuturism, solarpunk looks completely to the future. Not an alternative future, but a possible future.

Our futurism is not nihilistic like cyberpunk and it avoids steampunk’s potentially quasi-reactionary tendencies: it is about ingenuity, generativity, independence, and community.

Solarpunk emphasizes environmental sustainability and social justice.

Solarpunk is about finding ways to make life more wonderful for us right now, and also for the generations that follow us.

Our future must involve repurposing and creating new things from what we already have. Imagine “smart cities” being junked in favor of smart citizenry.

Solarpunk recognizes the historical influence politics and science fiction have had on each other.

Solarpunk recognizes science fiction as not just entertainment but as a form of activism.

Solarpunk wants to counter the scenarios of a dying earth, an insuperable gap between rich and poor, and a society controlled by corporations. Not in hundreds of years, but within reach.

Solarpunk is about youth maker culture, local solutions, local energy grids, ways of creating autonomous functioning systems. It is about loving the world.

Solarpunk culture includes all cultures, religions, abilities, sexes, genders and sexual identities.

Solarpunk is the idea of humanity achieving a social evolution that embraces not just mere tolerance, but a more expansive compassion and acceptance.

The visual aesthetics of Solarpunk are open and evolving. As it stands, it is a mash-up of the following:

1800s age-of-sail/frontier living (but with more bicycles)

Creative reuse of existing infrastructure (sometimes post-apocalyptic, sometimes present-weird)

Appropriate technology

Art Nouveau

Hayao Miyazaki

Jugaad-style innovation from the non-Western world

High-tech backends with simple, elegant outputs

Solarpunk is set in a future built according to principles of New Urbanism or New Pedestrianism and environmental sustainability.

Solarpunk envisions a built environment creatively adapted for solar gain, amongst other things, using different technologies. The objective is to promote self sufficiency and living within natural limits.

In Solarpunk we’ve pulled back just in time to stop the slow destruction of our planet. We’ve learned to use science wisely, for the betterment of our life conditions as part of our planet. We’re no longer overlords. We’re caretakers. We’re gardeners.

Solarpunk:

is diverse

has room for spirituality and science to coexist

is beautiful

can happen. Now

-The Solarpunk Community

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

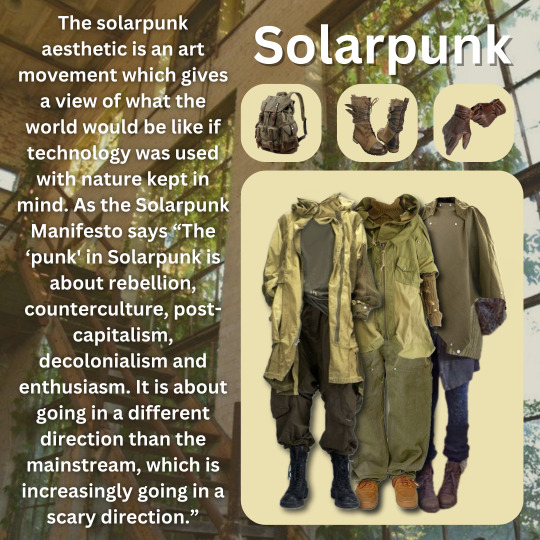

The solarpunk aesthetic is an art movement/genre of fiction which aims to give a view of what the world would be like if technology was used with nature kept in mind. While the concept of technology in balance with nature is quite broad, the key ideas revolve around connections to the earth and other people through culture, renewable energy, and restarting civilization. As the Solarpunk Manifesto says “The ‘punk' in Solarpunk is about rebellion, counterculture, post-capitalism, decolonialism and enthusiasm. It is about going in a different direction than the mainstream, which is increasingly going in a scary direction.”

Where does the name solarpunk come from? At first glance, you would assume it comes from renewable energy, mainly solar energy, and you would be half right. Solarpunk gets its name from plants and the way they’re able to use the sun as energy, which inspires us to create technology that does the same. Solarpunk focuses on the ways today’s technology restricts and destroys, highlighting features of human life that are intertwined with technology today but can be separated with time (culture, music, crafts, etc…)

Solarpunk as a movement sparked because of climate change, overpopulation, and the hope those things began to take away. The movement focuses on making our own clothes, tech, food, and anything else you can think of, which makes teamwork very important. Solarpunk offers solutions to today’s problems that could be used to build our world again from the ground up rather than just warning us that the way the world is going is bad with no ideas on how to fix that.

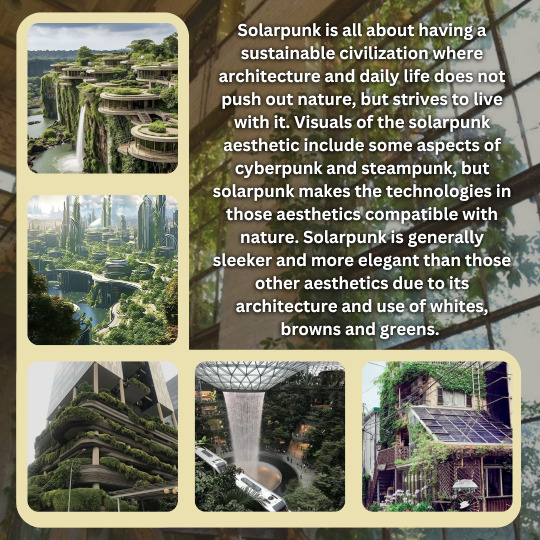

Solarpunk is all about having a sustainable civilization where architecture and daily life does not push out nature, but strives to live with it. Houses, cafes, businesses, skyscrapers would all be built with gardens or some kind of vegetation growing on its walls or roofs. By isolating human cities to small and compact areas, we can both have a productive civilization and let nature reclaim the land we took.

Visuals of the solarpunk aesthetic include some aspects of other techpunk aesthetics such as cyberpunk and steampunk, but solarpunk aims to make the technologies existing in those aesthetics compatible with nature running them on more sustainable energy. Solarpunk is also generally sleeker and more elegant than those other aesthetics due to its architecture and use of whites, browns and greens.

For more information on solarpunk, view these solarpunk resources:

Solarpunk aesthetic wiki

Solarpunk manifesto

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Solarpunk Manifesto

Solarpunk is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion, and activism that seeks to answer and embody the question “what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there?”

The aesthetics of solarpunk merge the practical with the beautiful, the well-designed with the green and lush, the bright and colorful with the earthy and solid.

Solarpunk can be utopian, just optimistic, or concerned with the struggles en route to a better world , but never dystopian. As our world roils with calamity, we need solutions, not only warnings.

Solutions to thrive without fossil fuels, to equitably manage real scarcity and share in abundance instead of supporting false scarcity and false abundance, to be kinder to each other and to the planet we share.

Solarpunk is at once a vision of the future, a thoughtful provocation, a way of living and a set of achievable proposals to get there.

We are solarpunks because optimism has been taken away from us and we are trying to take it back.

We are solarpunks because the only other options are denial or despair.

At its core, Solarpunk is a vision of a future that embodies the best of what humanity can achieve: a post-scarcity, post-hierarchy, post-capitalistic world where humanity sees itself as part of nature and clean energy replaces fossil fuels.

The “punk” in Solarpunk is about rebellion, counterculture, post-capitalism, decolonialism and enthusiasm. It is about going in a different direction than the mainstream, which is increasingly going in a scary direction.

Solarpunk is a movement as much as it is a genre: it is not just about the stories, it is also about how we can get there.

Solarpunk embraces a diversity of tactics: there is no single right way to do solarpunk. Instead, diverse communities from around the world adopt the name and the ideas, and build little nests of self-sustaining revolution.

Solarpunk provides a valuable new perspective, a paradigm and a vocabulary through which to describe one possible future. Instead of embracing retrofuturism, solarpunk looks completely to the future. Not an alternative future, but a possible future.

Our futurism is not nihilistic like cyberpunk and it avoids steampunk’s potentially quasi-reactionary tendencies: it is about ingenuity, generativity, independence, and community.

Solarpunk emphasizes environmental sustainability and social justice.

Solarpunk is about finding ways to make life more wonderful for us right now, and also for the generations that follow us.

Our future must involve repurposing and creating new things from what we already have. Imagine “smart cities” being junked in favor of smart citizenry.

Solarpunk recognizes the historical influence politics and science fiction have had on each other.

Solarpunk recognizes science fiction as not just entertainment but as a form of activism.

Solarpunk wants to counter the scenarios of a dying earth, an insuperable gap between rich and poor, and a society controlled by corporations. Not in hundreds of years, but within reach.

Solarpunk is about youth maker culture, local solutions, local energy grids, ways of creating autonomous functioning systems. It is about loving the world.

Solarpunk culture includes all cultures, religions, abilities, sexes, genders and sexual identities.

Solarpunk is the idea of humanity achieving a social evolution that embraces not just mere tolerance, but a more expansive compassion and acceptance.

The visual aesthetics of Solarpunk are open and evolving. As it stands, it is a mash-up of the following:

1800s age-of-sail/frontier living (but with more bicycles)

Creative reuse of existing infrastructure (sometimes post-apocalyptic, sometimes present-weird)

Appropriate technology

Art Nouveau

Hayao Miyazaki

Jugaad-style innovation from the non-Western world

High-tech backends with simple, elegant outputs

Solarpunk is set in a future built according to principles of New Urbanism or New Pedestrianism and environmental sustainability.

Solarpunk envisions a built environment creatively adapted for solar gain, amongst other things, using different technologies. The objective is to promote self sufficiency and living within natural limits.

In Solarpunk we’ve pulled back just in time to stop the slow destruction of our planet. We’ve learned to use science wisely, for the betterment of our life conditions as part of our planet. We’re no longer overlords. We’re caretakers. We’re gardeners.

Solarpunk:

is diverse

has room for spirituality and science to coexist

is beautiful

can happen. Now

The Solarpunk Community

Via https://www.re-des.org

1 note

·

View note

Text

STEAMPUNK DECOLONIAL TRANSHUMANISTA - Um Trecho de Steam Runnerz RPG - Mercenários Transhumanos da Era do Éter - Sistema 2D6WORLD PbtA | NITROGAMES

STEAMPUNK DECOLONIAL TRANSHUMANISTA – Um Trecho de Steam Runnerz RPG – Mercenários Transhumanos da Era do Éter – Sistema 2D6WORLD PbtA | NITROGAMES

Um trecho do meu projeto atual, o Steam Runnerz RPG – Mercenários Transhumanos da Era do Éter (Sistema 2d6WORLD PbtA) sobre o steampunk pós-colonial e decolonial do cenário. 🙂 Revenantes, um famoso grupo de mercenários transhumanos Steam Runnerz lutando contra uma infestação de Aberrantes no distrito Mutatis Mutantis de InteSteam, a Cidade Estranha em 12 de Março de 1899 | Ilustração: Newton…

View On WordPress

#2d6World#Jogo de RPG#Nitrodungeon#Nitrogames#Pós-Colonial#PbtA#RPG#Steam Runnerz#Steampunk Decolonial

0 notes

Text

A Solarpunk Manifesto

Solarpunk is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion, and activism that seeks to answer and embody the question “what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there?”

The aesthetics of solarpunk merge the practical with the beautiful, the well-designed with the green and lush, the bright and colorful with the earthy and solid.

Solarpunk can be utopian, just optimistic, or concerned with the struggles en route to a better world , but never dystopian. As our world roils with calamity, we need solutions, not only warnings. Solutions to thrive without fossil fuels, to equitably manage real scarcity and share in abundance instead of supporting false scarcity and false abundance, to be kinder to each other and to the planet we share.

Solarpunk is at once a vision of the future, a thoughtful provocation, a way of living, and a set of achievable proposals to get there.

We are solarpunks because optimism has been taken away from us and we are trying to take it back.

We are solarpunks because the only other options are denial or despair.

At its core, solarpunk is a vision of a future that embodies the best of what humanity can achieve: a post-scarcity, post-hierarchy, post-capitalist world where humanity sees itself as part of nature and clean energy replaces fossil fuels.

The “punk” in solarpunk is about rebellion, counterculture, post-capitalism, decolonialism, and enthusiasm. It is about going in a different direction than the mainstream, which is increasingly going in a scary direction.

Solarpunk is a movement as much as it is a genre: it is not just about the stories, it is also about how we can get there.

Solarpunk embraces a diversity of tactics: there is no single right way to do solarpunk. Instead, diverse communities from around the world adopt the name and the ideas, and build little nests of self-sustaining revolution.

Solarpunk provides a valuable new perspective, a paradigm, and a vocabulary through which to describe one possible future. Instead of embracing retrofuturism, solarpunk looks completely to the future. Not an alternative future, but a possible future.

Our futurism is not nihilistic like cyberpunk, and it avoids steampunk’s potentially quasi-reactionary tendencies: it is about ingenuity, generativity, independence, and community.

Solarpunk emphasizes environmental sustainability and social justice.

Solarpunk is about finding ways to make life more wonderful for us right now, and also for the generations that follow us.

Our future must involve repurposing and creating new things from what we already have. Imagine “smart cities” being junked in favor of smart citizenry.

Solarpunk recognizes the historical influence politics and science fiction have had on each other.

Solarpunk recognizes science fiction as not just entertainment but as a form of activism.

Solarpunk wants to counter the scenarios of a dying earth, an insuperable gap between rich and poor, and a society controlled by corporations. Not in hundreds of years, but within reach.

Solarpunk is about youth maker culture, local solutions, local energy grids, ways of creating autonomous functioning systems. It is about loving the world.

Solarpunk culture includes all cultures, religions, abilities, sexes, genders, and sexual identities.

Solarpunk is the idea of humanity achieving a social evolution that embraces not just mere tolerance but a more expansive compassion and acceptance.

The visual aesthetics of Solarpunk are open and evolving. As it stands, it is a mash-up of the following:

1. 1800s age-of-sail/frontier living (but with more bicycles)

2. Creative reuse of existing infrastructure (sometimes post-apocalyptic, sometimes present-weird)

3. Appropriate technology

4. Art Nouveau

5. Hayao Miyazaki

6. Jugaad-style innovation from the non-Western world

7. High-tech backends with simple, elegant outputs

Solarpunk is set in a future built according to principles of New Urbanism or New Pedestrianism, and environmental sustainability.

Solarpunk envisions a built environment creatively adapted for solar gain, amongst other things, using different technologies. The objective is to promote self sufficiency and living within natural limits.

In solarpunk we’ve pulled back just in time to stop the slow destruction of our planet. We’ve learned to use science wisely, for the betterment of our life conditions as part of our planet. We’re no longer overlords. We’re caretakers. We’re gardeners.

Solarpunk:

1. is diverse

2. has room for spirituality and science to coexist

3. is beautiful

4. can happen. Now.

(source)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fur and flesh to metal and fire: Native woman as embodiment of cultural tradition and anti-colonial re-configurations of steampunk in “Good Hunting”

Introductory note

I’ve seen tumblr posts and opinion pieces praising and condemning the animated adaptation of Ken Liu’s “Good Hunting” in Love, Death + Robots. Whether positive or negative, most comments are brief and reactionary, with some expressing awe towards the steampunk and Chinese folklore elements, and/or disappointment towards its depictions of sexual and racial violence. I’m writing this post as an appeal for viewers and readers to consider the centrality and depth of European colonialism to the narrative, and attempt to interpret the story’s denotations on the dynamics between the European colonizer, the colonized man, and woman in the aftermath of the Opium War. This post draws heavily on Ken Liu’s original text in addition to the Netflix adaptation.

Summary:

The gendered Chinese folklore of the Huli jing and Good Hunting’s subversion

Colonial British “progression” (in the form of steam tech) displaces Chinese folklore

The Body is Political – conquest of body and land

The Empire’s Subjects Strike Back – Re-programming steampunk for decolonial resistance

Personal evaluations on adapting text to film

The gendered Chinese folklore of the Huli jing and Good Hunting’s subversion

The text introduces the huli jing as a figure of Chinese folklore: one that, like the succubus of the West, is a predatory female that seduces and preys on men. It is a folklore that reflects male anxieties of the dangers and dirtiness of female sexuality:

[1]

“You must save him,” the merchant’s wife had said, bowing like a chicken pecking at rice. “If this gets out, the matchmakers won’t touch him at all.” [2]

The huli jing is a figure heavily entrenched in the Chinese psyche as promiscuous, immoral, and sexually devious, to the extent that it even permeates the language: “huli jing” is widely used today as an insult against sexually deviant women (usually against 小三 / 3rd party / side woman, like slut / bitch). Liu’s depiction is thus very explicitly and purposefully subversive in its attempt to give the huli jing a voice, to testify to their innocence (or at the very least, blamelessness):

“She liked her freedom and didn’t want anything to do with him. But once a man has set his heart on a hulijing, she cannot help hearing him no matter how far apart they are. All that moaning and crying he did drove her to distraction, and she had to go see him every night just to keep him quiet.”

This was not what I learned from Father.

“She lures innocent scholars and draws on their life essence to feed her evil magic! Look how sick the merchant’s son is!”

“He’s sick because that useless doctor gave him poison that was supposed to make him forget about my mother. My mother is the one who’s kept him alive with her nightly visits. And stop using the word lure. A man can fall in love with a hulijing just like he can with any human woman.” [2]

Liu makes his intentions clear in the comment:

In writing this story, I wanted […] to turn the misogynistic huli jing legends upside down. In these legends, usually composed by male scholars, the huli jing is a dangerous feminine creature who uses her sexuality to deprive men of their vitality and essence. My huli jing questions that narrative. [3]

Following Yan’s appeal and the brutal death of her mother, the protagonist Liang and the viewer/reader alike become convinced of her innocence and the huli jing‘s victimhood – we become aligned with her. And indeed, the text seems to unite the native Chinese characters and folklore across gendered and human/demon fault lines against the greater threat of foreign colonizers.

Colonial British “progression” (in the form of steam tech) displaces Chinese folklore

The narrative is set in the aftermath of the Opium War, and the British occupation of Hong Kong (around 1841). Though Yan and Liang reside in a more rural area, the British presence is strongly felt, mainly through the steam trains and railways that come to penetrate the landscape:

I had heard rumors that the Manchu Emperor had lost a war and been forced to give up all kinds of concessions, one of which involved paying to help the foreigners build a road of iron. But it had all seemed so fantastical that I didn’t pay much attention. [2]

The train is widely presented as a symbol of modernity that the “progressive” British colonizers attempt to bring to their “backward” colonies in their civilizing mission [4]. The “advancement” of the steam train is clearly antagonistic to the “primitive” native religion – they cannot coexist, and with colonization, the occupier’s system of logic, truth and tech displaces native belief, practice and magic:

Thompson strode over to the buddha and looked at it appraisingly. […]

Then I heard a loud crash and a collective gasp from the men in the main hall.

“I’ve just broken the hands off of this god of yours with my cane,” Thompson said. “As you can see, I have not been struck by lightning or suffered any other calamity. Indeed, now we know that it is only an idol made of mud stuffed with straw and covered in cheap paint. This is why you people lost the war to Britain. You worship statues of mud when you should be thinking about building roads from iron and weapons from steel.”

There was no more talk about changing the path of the railroad.

After the men were gone, Yan and I stepped out from behind the statue. We gazed at the broken hands of the buddha for a while.

“The world’s changing,” Yan said. “Hong Kong, iron roads, foreigners with wires that carry speech and machines that belch smoke. More and more, storytellers in the teahouses speak of these wonders. I think that’s why the old magic is leaving. A more powerful kind of magic has come.” [2]

Note the privileging of the new and inorganic (roads of iron, weapons of steel) over the old and organic (statues of mud and straw) – the landscape (and later, Yan’s organic body) transforms in this manner. Yan details how the changes affect her: she can no longer transform at will, and barely hunts enough for survival.

Liang is likewise affected. The text explains his decision to leave for British-administered Hong Kong: colonization renders his family’s demon hunting business obsolete, and his father takes his own life:

People stopped coming to Father and me to ask for our services. They either went to the Christian missionary or the new teacher who said he’d studied in San Francisco. Young men in the village began to leave for Hong Kong or Canton, moved by rumors of bright lights and well-paying work. […] As I let his body down, my heart numb, I thought that he was not unlike those he had hunted all his life: they were all sustained by an old magic that had left and would not return, and they did not know how to survive without it. [2]

Regardless of their previous antagonism, human and demon, man and woman alike are dispossessed by colonialism. For the native woman especially, this colonial invasion is particularly intimate, as it occurs at the level of the sexual.

The Body is Political – conquest of body and land

I believe that Good Hunting illustrates how the native woman embodies the culture of the colonized, and thus her body becomes a site of political and sexual contestation. I base this belief on notions from Frantz Fanon’s essay, “Algeria Unveiled”, in which he describes the psycho-sexual antagonism arising between the white French colonizer and the veiled Muslim women of Algeria. Needless to say, real-life accounts differ from fictive re-imaginings, and the cultural configurations of French Algeria and British Hong Kong are definitely inequivalent, yet, they share common rhythms in the dynamic of sexual violence between white colonizer and the exoticized colonial subject.

Fanon explicates how the veiled Muslim woman’s body came to represent the whole culture of the colonized peoples of Algeria:

One may remain for a long time unaware of the fact that a Moslem does not eat pork or that he denies himself daily sexual relations during the month of Ramadan, but the veil worn by the women appears with such constancy that it generally suffices to characterize Arab society. We have seen that on the level of individuals the colonial strategy of destructuring Algerian society very quickly came to assign a prominent place to the Algerian woman. The colonialist’s relentlessness, his methods of struggle were bound to give rise to reactionary forms of behavior on the part of the colonized. In the face of the violence of the occupier, the colonized found himself defining a principled position with respect to a formerly inert element of the native cultural configuration. [5]

In short, the veil, a “formerly inert element” of Algerian Muslim culture, gains significance because it becomes a marker of that culture, a marker of difference, under the white colonizer’s gaze. To eliminate native culture, it is therefore imperative to eliminate the veil, and the native Algerian reacts by resisting this unveiling. In this manner, the Algerian woman’s body becomes a site for colonial conflict. This is why imperial expansion and territorial conquest is inextricably tied to rape – think of the pervasiveness of “rape and pillage”:

The history of the French conquest in Algeria, including the overrunning of villages by the troops, the confiscation of property and the raping of women, the pillaging of a country, has contributed to the birth and the crystallization of the same dynamic image. At the level of the psychological strata of the occupier, the evocation of this freedom given to the sadism of the conqueror, to his eroticism, creates faults, fertile gaps through which both dreamlike forms of behaviour and, on certain occasions, criminal acts can emerge. Thus the rape of the Algerian woman in the dream of a European is always preceded by a rending of the veil. We here witness a double deflowering. [5]

Thus, it is at this site of sexual contestation of the woman’s body that struggle and resistance takes place. To me, Fanon’s conflation of the woman’s body to the native land and culture allows us to better understand Good Hunting. Yan’s identity as a huli jing already presents her as an embodiment of Chinese “old magic”. With British industrialization and influence, Chinese magic is quelled, and Yan loses her powers, symbolizing the disempowerment of Chinese culture.

As colonial steam technology dominates the landscape, native magic weakens, as does Yan’s body. The violence exacerbates when the characters migrate to the centre of colonial administration – Victoria Peak in Hong Kong. Here, there is a gendered difference in the way Liang and Yan are brutalized. Liang’s engineering talent is discounted – the native’s labour is exploited and undervalued.

“Are you the man who came up with the idea of using a larger flywheel for the old engine?”

I nodded. I took pride in the way I could squeeze more power out of my machines than dreamed of by their designers.

“You did not steal the idea from an Englishman?” his tone was severe.

I blinked. A moment of confusion was followed by a rush of anger. “No,” I said, trying to keep my voice calm. I ducked back under the machine to continue my work.

“He is clever,” my shift supervisor said, “for a Chinaman. He can be taught.”

“I suppose we might as well try,” said the other man. “It will certainly be cheaper than hiring a real engineer from England.” [2]

This is immediately followed by a scene of British clients sexually harassing Yan, now a sex worker.

The dialogue deliberately frames their subjugation as racialized. Liang adapts to colonial Hong Kong but he is not a part of it – he becomes educated in the technical language of the colonizer, replacing his inherited knowledge of magic with that of steam, but his racial difference is constantly referenced (perhaps he’s “white but not quite” [6]). He is a “Chinaman” regardless of ability and any attempt at assimilation. This discrimination occurs in the capacity as employer-employee, master-servant, at the meeting point of the train operations room, the workplace. For the native woman, due to the colonial sexual appetite – the tradition of rape and pillage – violence occurs at the intimate meeting point of her body, on which white expectations of her race are burdened – note how the stereotype of Chinese industriousness is used to pressure her into sexual labour. The colonizers feel entitled to the servitude of both native bodies – the man’s labour, and the woman’s sexual subjugation.

The text notes that this violent encounter leading to Yan and Liang’s reunion happens on a culturally significant date:

“Don’t let the Chinese ghosts get you,” a woman with bright blond hair said in the tram, and her companions laughed.

It was the night of Yulan, I realized, the Ghost Festival. I should get something for my father, maybe pick up some paper money at Mongkok. […]

“It’s the night of the Ghost Festival,” [Yan] said. “I didn’t want to work any more. I wanted to think about my mother.”

“Why don’t we go get some offerings together?” I asked. [2]

Similar to Día de Muertos – the Mexican Day of the Dead – the month of the Hungry Ghost Festival is a time to remember and honour the deceased. It is believed that the gates of the underworld open during the seventh lunar month, and the spirits of the departed return to visit the living. We follow Liang’s thoughts as he realizes it is the night of Yulan, and immediately encounter Yan, which might suggest to us that she is a ghost of sorts coming back to haunt him – she represents an old culture, dead or dying. The story connects the violent encounter, the sexual degradation of Yan’s magic-drained body, to the death of Yan and Liang’s parents, and maybe even the death of Yan herself. Colonial violence corresponds to the death of native culture.

To further cement this idea that the colonized woman’s body is conflated to the land, Yan’s body comes to receive the ultimate abuse from the figure of the governor (or the governor’s son, in the original text). Her sexual perpetrator is not an everyman, but the political representative of the British colonist; where Yan embodies native Chinese culture, her rapist embodies the British colonial administration. He ravages and consumes her body as a colonizer takes and devours territory – I think the showrunners deliberately portrayed him as obese to evoke a grotesque image of imperialist greed and over-consumption of the colonies�� resource. (Of course, this has problematic real-life implications on public perceptions of fat people.) He takes her organic body apart and reconstructs her to his own fetish fantasy of steel and chrome – just as Britain fragments, reforms, reshapes China’s trade, opium economy, and territory (e.g. Hong Kong), to its own will.

Yan’s rape and reconstruction is thus conflated to the political conquest of China and Hong Kong. (Jameson’s notion of the national allegory comes to mind. [7])

The Empire’s Subjects Strike Back – Re-programming steampunk for decolonial resistance

In Good Hunting, the mode of S/F (= speculative fiction / science fiction / science fantasy) enables imagination of how the native can re-appropriate and re-configure the colonizer’s weapons against them. Ken Liu notes:

I think there’s a paucity of good steampunk that addresses the dark stain of colonialism in a satisfactory way. Like many of my stories, this tale has an anti-colonial theme. [Yan] says, at one point, “A terrible thing had been done to me, but I could also be terrible.” It is about as succinct a summary of the experience of being a member of a colonized population as I can give. [3]

A recognizable figure of Buddhism is shown before Liang and Yan move to Hong Kong, in the form of a Buddha statue. Yan is shown in the same frame bowing to it, aligning her with the natives’ religion and again, reinforcing her as a representative of native culture. The next encounter with a religious figure comes in the form of Guan Yin, and if the friend I consulted is not mistaken, it’s possibly the incarnation with 千手千眼 / “The One With A Thousand Arms and Thousand eyes”:

The buddha Amitābha, upon seeing her plight, gave her eleven heads to help her hear the cries of those who are suffering. Upon hearing these cries and comprehending them, Avalokiteśvara attempted to reach out to all those who needed aid, but found that her two arms shattered into pieces. Once more, Amitābha came to her aid and appointed her a thousand arms to let her reach out to those in need. [8]

This statue looks on, and takes up the entire frame as the rapist-governor cries out in pain offscreen while Yan attacks him with her new mechanized strength, her body no longer victimized but newly weaponized, declaring “I could also be terrible”. The Guan Yin statue frames Yan’s act as one of divine retribution – an individual woman’s rebellion that draws strength from a wider colonized peoples and their religion. Though her organic magic had been forcefully amputated and replaced with the colonizer’s inorganic steam tech, the image of Guan Yin suggests that the old culture is not dead, but reborn in a new incarnation, to deliver comeuppance.

(Personal disclaimer: it is with bitter irony that I must admit my estrangement from these figures – so feel free to add or counter this if you’re more well-informed on the significance of Guan Yin and Buddha here.)

As I’ve mentioned before, Liang’s proficiency in the colonizer’s language of technology functions as a means of his survival, but this same distancing and Othering of him by the colonists keeps him from fully aligning himself with them, and he readily repurposes his mechanical expertise for the antagonistic cause of rebellion, thus engineering not a steam train (weapon of British imperial expansion) but a huli jing (weapon of Chinese folklore and emasculation, albeit the target of emasculation has shifted). The same technology that drove out the magic is now used to empower that folklore.

In these acts of re-configuration, I see an endeavour to visualize how a threatened culture can survive and thrive in the future. Creators like Ytasha Womack emphasize how the S/F genre of Afrofuturism (emphasis on “future”) is necessary for black persons to imagine a future with themselves in it, to provide a vision of empowerment, possibility, and survival [9]. Good Hunting’s narrative, though more of an alternate history, similarly offers a positive possibility in which Chinese culture and mythology is not smothered by colonialism and technological change, but adapted to it:

The old magic was back but changed: not fur and flesh, but metal and fire. [2]

I would also tentatively speculate that perhaps this narrative of colonized man allying himself to empower colonized woman is also driven by an impulse (maybe underlying, at the level of the subconscious) to quell male anxieties of colonial domination and complicity in female subjugation – to re-imagine a history where the figure of the Chinese male is less of a passively helpless witness to sexual abuse, to his country’s subjugation, but an active agent able to empower her. In other words, it could be a case of ‘fantasy as coping mechanism for trauma’ – re-imagining the outcomes of a traumatic past such that the victim-survivor overcomes his abuser (in this case, I see it coming from a male perspective).

Finally, I think this ‘weaponizing the colonizer’s own tools against him’ works on a metafictional level as well: the English language has long been the medium and weapon of English / white supremacy. See Macaulay’s minute on education in which he basically appeals for Indian colonial subjects to be educated in Eng to transmit British ideas, modes of thinking, systems of thought [10]. English language and literature works to naturalize anglo-imperialist modes of reasoning, to colonize the imagination. I like to think that for Chinese-American Ken Liu to tell this story in English is a re-purposing of the language to bite back at the colonizer. And if we regard the steampunk trope as a playful British fantasy of Victorian-era aesthetics, Liu’s re-fashioning and appropriation of the trope – to infuse it with a tale of colonial vengeance – is akin to Liang and Yan’s appropriation of the colonizer’s own weapons. Liu’s act of writing Good Hunting may be exemplary of how “the empire writes back with a vengeance”, to quote Salman Rushdie [11].

Personal evaluations on adapting text to film

I find that the animated adaptation has a heavier “male gaze”, a term coined by film critic Laura Mulvey: mainstream cinema is a product of patriarchal institution, and most films assume the perspective of a male, while the female is configured onscreen as erotic object [12]. To borrow Linda Williams’ words, “the bodies of women figures on the screen have functioned traditionally as the primary embodiments of pleasure, fear, and pain” [13]. The animated adaptation appears more explicit in its spectacles of female nudity and victimhood, evident in the shots panning up Yan’s legs as a harasser raises a cane to lift her dress; over her struggling, restrained, unclothed body; and over her face contorted in fear and disgust. I’ve wondered if this is necessitated because the showrunners need to show her ordeal whereas the writer only need tell it – in film, we do not get to hear her recount of suffering and survival as much as we see it. Yet, I’m fairly convinced the perspective has a focus that deliberately eyes the female form for sexual gratification – exemplified by shots of her glutes, bust, and unnecessarily bared breasts.

Science fiction, steampunk and machination has high visual appeal; they delight and enthrall as visual spectacles. It is unfortunate when narratives that indulge and play with such spectacular concepts remain coloured by patriarchal desires, and become so heavily infused with the sexual indulgence in disempowered women. This conventional fanboy approach to steampunk / SF – the entitlement to consuming fantastical tech and women – almost repeats the desires of the European colonizer-rapist that Good Hunting condemns:

In a city filled with chrome and brass and clanging and hissing, desires became confused” [2].

It is my personal conviction that the adaptation somewhat diminishes (but doesn’t erase!) the anti-colonial impact of the original text through its lapses into the impulse to consume the colonized woman’s body – the same impulse that the text works so hard to undo. So, as much as I enjoyed this and most other episode of LDR (because as a series, it’s not that much different from other mainstream depictions of women i.e. I’m sensitized and used to it), it would’ve benefited greatly from a purposeful questioning of, and distancing from, the mainstream male perspectives of science fiction.

Concluding Remarks

Even with these shortcomings, Good Hunting is undoubtedly rich in cultural meaning and purposefully, powerfully anti-colonial. It is vital to acknowledge its value in destabilizing colonial mindsets and tropes, instead of shallowly and reflexively dismissing its whole narrative for containing sexual and racial violence, and how it doesn’t comfortably fit into contemporary, widely-accepted, Western expectations of ‘girl power’.

Ken Liu’s text does not bemoan the victimization of Chinese culture in the post-Opium War period of colonization, but re-configures, upgrades, modernizes, adapts the old magic to its new technological environment, with the stubborn anti-colonial tenacity for continued cultural survival.

References:

1. “Good Hunting”, Love, Death & Robots, Netflix

2. Ken Liu, “Good Hunting”, 2012

3. Ken Liu, Story Notes: “Good Hunting” in Strange Horizons, 2012

4. Science and Technology: Transport: Railways - The British Empire

5. Frantz Fanon, “Algeria Unveiled”, A Dying Colonialism, 1965

6. Homi Bhabha, “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse”, 1984

7. Fredric Jameson, “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism”, 1986

8. Wikipedia, “Guanyin and the Thousand Arms”

9. Steven W Thrasher, “Afrofuturism: reimagining science and the future from a black perspective”, 2015

10. Thomas Babington Macaulay, “Minute on Education”, 1835

11. Salman Rushdie, “The empire writes back with a vengeance”, 1982

12. Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, 1975

13. Linda Williams, “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess, 1991

#good hunting#ken liu#love death and robots#ldr#postcolonial literature#the paper menagerie and other stories#postcolonialism#decolonization#ask to tag#我发的#我写到废寝忘食

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Dirt Behind Our Ears” : On Solarpunk and the Need for New Futures

I was asked to submit a talk to a HUGE conference over in Berlin to talk about Solarpunk and what it’s like to have been involved in the genre from the very beginning as an admin over on @solarpunks. I found out this week that it wasn’t accepted, but some other solarpunks were - watch solarpunks.net for more info.

I’m posting my talk proposal below as it’s the first time that I’ve written something on solarpunk. Some of the wording and phrasing as become important to me especially the lines about not being able to speak for other solarpunks.

“Dirt Behind Our Ears” : On Solarpunk and the Need for New Futures

Give a short and catchy idea about your main argument. This text will be used publicly once your session is accepted, so it's worth proofreading it.

500 Char Public Thesis - ~ 75 Words

Solarpunk is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion and activism that seeks to answer and embody the question “what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there?”.

The future does not passively ‘arrive’ fully formed from the aether, we must first meet it the way humanity has always done: though dreams, stories and song. This session will cover the story of the nascent genre of solarpunk and the communities attempts to ‘remake our present and future history’.

Please describe what your session is about, how you want to proceed and what methods you are going to use. Be clear and check orthography and grammar. This text will be used publicly once your session is accepted, so it's worth proofreading it.

2000 Char Description - ~ 300 Words

The emerging science fictional genre and aesthetic of “solarpunk” begins with ‘Infrastructure as a form of resistance’.

In 2014 the EIA, CIA, & World Bank published a graph charting the falling cost of solar energy and titled it ‘Welcome to the Terrordome’. The upcoming 21st Century shift toward clean energy opens the future to an age of ‘innovative dissent’.

But we don’t see terror in this future. Solarpunk envisions a world where the drastic technological shift towards renewables and decentralisation empowers movements for social justice and economic liberation. It attempts to foster a socio-cultural environment which emphasises individual autonomy, consent, unity-in-diversity, with the free egalitarian distribution of power. It creates a multitude of spaces for indigenous sovereignties, reproductive justice, and radical queer politics. Of course with these principles comes polyphony, one cannot speak for other solarpunks, only be in dialogue and occasional chorus with them. Some solarpunks recognize it was a great tragedy that the alternate historical genre of steampunk was not decolonial to its core from its inception. Others call for the recognition of rights for the ‘non-human’: trees, rivers and mountains. And technologists building decentralised P2P social networks are doing so under a solarpunk banner. The genre provides a rich soil of ideas and action from which our struggles en route to a better world can grow.

This session will briefly explore the history of the genre, some of its central themes and principles and offer a present that can help us begin to see a future with a human face and dirt behind its ears.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

@winterrose66

A solarpunk manifesto:

Solarpunk is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion, and activism that seeks to answer and embody the question “what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there?”

The aesthetics of solarpunk merge the practical with the beautiful, the well-designed with the green and lush, the bright and colorful with the earthy and solid.

Solarpunk can be utopian, just optimistic, or concerned with the struggles en route to a better world , but never dystopian. As our world roils with calamity, we need solutions, not only warnings.

Solutions to thrive without fossil fuels, to equitably manage real scarcity and share in abundance instead of supporting false scarcity and false abundance, to be kinder to each other and to the planet we share.

Solarpunk is at once a vision of the future, a thoughtful provocation, a way of living and a set of achievable proposals to get there.

We are solarpunks because optimism has been taken away from us and we are trying to take it back.

We are solarpunks because the only other options are denial or despair.

At its core, Solarpunk is a vision of a future that embodies the best of what humanity can achieve: a post-scarcity, post-hierarchy, post-capitalistic world where humanity sees itself as part of nature and clean energy replaces fossil fuels.

The “punk” in Solarpunk is about rebellion, counterculture, post-capitalism, decolonialism and enthusiasm. It is about going in a different direction than the mainstream, which is increasingly going in a scary direction.

Solarpunk is a movement as much as it is a genre: it is not just about the stories, it is also about how we can get there.

Solarpunk embraces a diversity of tactics: there is no single right way to do solarpunk. Instead, diverse communities from around the world adopt the name and the ideas, and build little nests of self-sustaining revolution.

Solarpunk provides a valuable new perspective, a paradigm and a vocabulary through which to describe one possible future. Instead of embracing retrofuturism, solarpunk looks completely to the future. Not an alternative future, but a possible future.

Our futurism is not nihilistic like cyberpunk and it avoids steampunk’s potentially quasi-reactionary tendencies: it is about ingenuity, generativity, independence, and community.

Solarpunk emphasizes environmental sustainability and social justice.

Solarpunk is about finding ways to make life more wonderful for us right now, and also for the generations that follow us.

Our future must involve repurposing and creating new things from what we already have. Imagine “smart cities” being junked in favor of smart citizenry.

Solarpunk recognizes the historical influence politics and science fiction have had on each other.

Solarpunk recognizes science fiction as not just entertainment but as a form of activism.

Solarpunk wants to counter the scenarios of a dying earth, an insuperable gap between rich and poor, and a society controlled by corporations. Not in hundreds of years, but within reach.

Solarpunk is about youth maker culture, local solutions, local energy grids, ways of creating autonomous functioning systems. It is about loving the world.

Solarpunk culture includes all cultures, religions, abilities, sexes, genders and sexual identities.

Solarpunk is the idea of humanity achieving a social evolution that embraces not just mere tolerance, but a more expansive compassion and acceptance.

The visual aesthetics of Solarpunk are open and evolving. As it stands, it is a mash-up of the following:1800s age-of-sail/frontier living (but with more bicycles), Creative reuse of existing infrastructure (sometimes post-apocalyptic, sometimes present-weird), Appropriate technology, Art Nouveau, Hayao Miyazaki, Jugaad-style innovation from the non-Western world, High-tech backends with simple, elegant outputs,

Solarpunk is set in a future built according to principles of New Urbanism or New Pedestrianism and environmental sustainability.

Solarpunk envisions a built environment creatively adapted for solar gain, amongst other things, using different technologies. The objective is to promote self sufficiency and living within natural limits.

In Solarpunk we’ve pulled back just in time to stop the slow destruction of our planet. We’ve learned to use science wisely, for the betterment of our life conditions as part of our planet. We’re no longer overlords. We’re caretakers. We’re gardeners.

Solarpunk: is diverse, has room for spirituality and science to coexist, is beautiful, can happen. Now.

controversial opinion but solarpunk > cottagecore

75 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It was, and still is, imperative that we have volumes dedicated to our own voices, projects not of postcolonial melancholia, but of decolonial determination. Our psyches cry for justice for lost names, lost stories, lost histories, all lost to globalized, systemic racism, lost to imperial dreams imposed upon us too long. In the absence of time machines to recover them, we turn to re-creating, and creating anew. Thus, we use steampunk to have that conversation with our histories, our hearts and dreams. [...] These waters which so many of us have traveled, upon and over, for fortune, for trade, for refuge, for livelihood - our ancestors' tears and sweat have been cast into the salt of the sea and we begin with the acknowledgement of their presence in our bloods, whether we break with tradition or re-cast it in the fire of the new worlds we have to build, proclaiming: THE SEA IS OURS!

Joyce Chng & Jaymee Goh, Introduction to The Sea Is Ours: Tales from Steampunk Southeast Asia, 2015

#the sea is ours#postcolonial literature#steampunk#southeast asian literature#englit#我发的#The Sea Is Ours: Tales from Steampunk Southeast Asia

3 notes

·

View notes