#Southern Hemisphere | Supercontinent of Gondwana

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gondwana Rainforests

Today, we're diving into the lush and ancient world of the Gondwana Rainforests, a UNESCO World Heritage Site nestled in the heart of Australia. If you're a nature enthusiast, adventure seeker, or just someone who craves a serene escape, this is the place to be.

The Gondwana Rainforests are a living testament to the Earth's history, dating back over 180 million years. These rainforests are remnants of the supercontinent Gondwana, which once covered the southern hemisphere. Wander through these primeval forests, and you'll feel like you've stepped back in time.

Prepare to be captivated by the incredible diversity of flora and fauna here. From towering Antarctic Beech trees to ancient ferns and orchids, the plant life is astonishing. Keep your eyes peeled for the vibrant plumage of native birds, the intricate webs of golden orb spiders, and the shy marsupials that call this rainforest home.

One of the jewels in the Gondwana Rainforests' crown is the Blue Mountains National Park. Famous for its towering eucalyptus trees and stunning vistas, this park offers everything from challenging hikes to relaxing strolls. Don't miss the iconic Three Sisters rock formation, which has its own intriguing Aboriginal legend.

Another gem within this UNESCO site is Lamington National Park. Here, you can explore subtropical rainforests, take a dip in pristine waterfalls, and hike through lush valleys. The park is also a birdwatcher's paradise, with the chance to spot rare species like the Albert's lyrebird.

Border Ranges National Park is a place of rugged beauty, with its cascading waterfalls and dramatic escarpments. Take a journey along the scenic Border Ranges Drive, which offers panoramic views of the park's lush valleys and ancient forests.

To deepen your understanding of this incredible rainforest, visit the World Heritage Rainforest Centre in Springbrook National Park. Here, you can learn about the area's geological history, its Aboriginal connections, and the ongoing conservation efforts to protect this natural wonder.

Whether you're into hiking, birdwatching, or simply reconnecting with nature, the Gondwana Rainforests have something for everyone. The challenging treks, serene walks, and breathtaking viewpoints will leave you with memories to cherish.

In conclusion, the Gondwana Rainforests are a living testament to the Earth's ancient past and a reminder of the importance of preserving our natural heritage. So, if you're looking for a destination that will take your breath away, immerse you in history, and connect you with the natural world, pack your bags and embark on a journey to this UNESCO World Heritage Oasis. 🌳🦜🌏

0 notes

Text

Fossilized Remains of 340-Pound Giant Penguin Found in New Zealand

— Sputnik | Wednesday February 08, 2023

There are 17 to 19 species of penguins living today, most in the Southern Hemisphere. Also found in New Zealand and parts of Zealandia, are other flightless birds - like an ancestor to New Zealand’s beloved Kiwi and a giant “elephant bird” that also lived in Madagascar as recently as 800 years ago.

Fossilized remains of the largest penguin known to science were recently discovered in New Zealand, shocking researchers who determined the massive bird weighed hundreds of pounds.

Named Kumimanu Fordycei, Paleontologists believe the species could have weighed up to 340 pounds. By comparison, the average adult Male Western Lowland Gorilla Weighs about 300 pounds.

The fossil was discovered in a 57-million-year-old boulder that had been cracked open with the tides. Along with it they also found the remains of several individual specimens of another large but not quite as big previously undiscovered ancient penguin named Petradyptes stonehousei and fragments of two smaller yet-unnamed species of ancient penguins.

Scientists estimate the newly-discovered penguins lived around 60 million years ago. Petradyptes, they estimate, weighed around 110 pounds, far smaller than the Kumimanu, but still large for a penguin. The emperor penguin, the largest penguin on Earth today, can weigh up to just 88 pounds.

The fossils were discovered by Alan Tennyson, a paleontologist at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in 2017, but were described and named on Wednesday in the Journal of Paleontology.

Most of what scientists know about the Kumimanu fordycei came from a humerus bone, which was nine and a half inches long - about twice the length of those in the emperor penguin.

Paleontologists have been unable to determine the height of the ancient giant penguin but one estimated that it probably stood about 5 feet 2 inches. That gives the giant penguin a stocky build - the average aforementioned Western Lowland Gorilla 🦍 stands at about 6 feet while being roughly 40 pounds lighter.

Coming from an older branch of the tree of the penguin evolutionary tree, both the Kumimanu and Petradyptes differed in appearance from modern day penguins in more ways than just their size. Paleontologists say they had primitive flippers that resembled flying and diving birds like puffins. Their leg structure was also angled forward, unlike modern penguins whose legs are shaped like an upside down “L” coming out of their spine.

Scientists Discover New Penguin Colony in Antarctica Using Satellite Imagery (January 20, 2023)! “This is an exciting discovery. The new satellite images of Antarctica's coastline have enabled us to find many new colonies. And whilst this is good news, like many of the recently discovered sites, this colony is small and in a region badly affected by recent sea ice loss,” the British Antarctic Survey's Dr Peter Fretwell said.

'Human-Sized Penguin' Uncovered by New Zealand Schoolchildren Reveals Ancient Species (09/17/202)!

Mike Safely, president of the Hamilton Junior Naturalist Club, says this is an experience that the children involved will remember for the rest of their lives. “It was a rare privilege for the kids in our club to have the opportunity to discover and rescue this enormous fossil penguin.”

Dr. Daniel Thomas, a senior lecturer in zoology from Massey’s School of Natural and Computational Sciences, determined that the fossil was between 27.3 million and 34.6 million years old. Thomas compared the identified species to the Kairaku penguins that were first described from Otago, but with much longer legs.

"Longer legs would have made the penguin much taller than other Kairuku species while it was walking on land; perhaps around 1.4m tall, and may have influenced how fast it could swim or how deep it could dive."

New Zealand has been a hot spot for finding ancient penguin fossils. In 2017, a closely related Kumimanu biceae was described as living just a few million years after the fordycei and weighed 220 pounds. The slightly slimmer giant penguin had a sharp “stork-like” beak that researchers think may have been used to stab prey. The beak of the Kuminmanu fordycei has not yet been discovered.

In 2021, a 4.5-feet tall penguin with unusually long legs was described after a group of students in a fossil hunting club found fossilized remains on a small peninsula in the Kawhia Harbor during a field trip.

One explanation for why giant penguins thrived at the time is because they evolved shortly after the meteor that killed off the dinosaurs hit Earth. That impact also killed most of the sea-faring reptiles, leaving a niche open for a large amphibious predator to fill their space. Sea-faring mammals, like seals and whales, had not yet evolved. Paleontologists hypothesize that once mammals reentered the sea, the giant penguins were out-competed and only the smaller penguins survived.

It is also worth noting that scientists now believe New Zealand and the Island of New Caledonia are a part of the Earth’s eighth continent, with most of the landmass sitting below the sea. This continent is known as Zealandia, which they believe broke off from the Southern Hemisphere supercontinent of Gondwana about 105 million years ago.

What would become Zealandia then stretched out in a process scientists don’t yet understand. Scientists are still debating if most Zealandia was always submerged, with just small islands poking out, or if it sank at one point. In either case, a sinking continent or a collection of islands make for a natural habitat for penguins. If it did sink, scientists estimate that it would have taken over a hundred million years, meaning the giant penguins could have lived while much of Zealandia was still above sea level.

#New Zealand 🇳🇿#Penguin 🐧#Giant Fossilized Remains of Penguins 🐧 🐧 🐧#Sputnik International#Kumimanu Fordycei#Western Lowland Gorilla 🦍#Paleontologists#Petradyptes#Peninsula | Kawhia Harbor#Island of New Caledonia 🇳🇨 | New Zealand 🇳🇿#Southern Hemisphere | Supercontinent of Gondwana

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

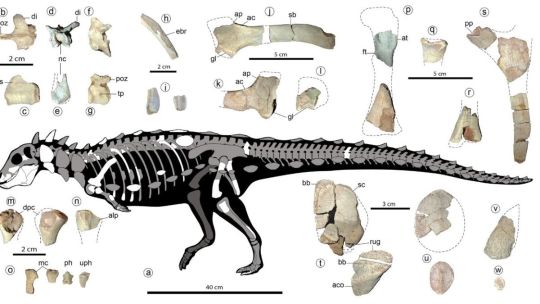

A New Species of Armored Dinosaur Discovered in Chile

It had a weaponized tail not seen before in any other dinosaur.

Roughly 2 meters (6.5 feet) in size, the small armored dinosaur called an ankylosaur dates from the late Cretaceous period, around 71.7 million to 74.9 million years ago. Its largely complete fossilized skeleton was found in Magallanes province in Patagonia, Chile's southernmost region.

Chilean paleontologist Sergio Soto was the lead author of the study.

The dinosaur, named Stegouros elengassen, had evolved a large tail weapon unlike those seen in other armored dinosaurs such as the paired spikes of Stegosaurus and the club-like tail of Ankylosaurus.

While its skull had features in common with other ankylosaurs, its tail weaponry was "bizarre," according to the study, which was published in the journal Nature on Wednesday. The dinosaur's tail had seven pairs of flattened, bony deposits fused together in a frond-like structure.

"The tail is extremely strange, as it is short for a dinosaur and the posterior half is encased in dermal bones (bones that grow in the skin) forming a unique (tail) weapon," said Sergio Soto Acuña, main author of the study and a doctoral student at the Universidad de Chile, via email.

He said it resembled the tail of a rattlesnake or spiny-tailed lizard. But unlike these creatures, the dinosaur possessed true bones under the scales. The most similar feature would be the tail of a giant armadillo, but they are also extinct, he added.

Stegouros, which means "roofed tail" in Greek and "elenggassen" is from Aonikenk, the language of the original inhabitants of Patagonia, and refers to a mythological armored beast. The fossil was found in 2018.

The study noted that very few ankylosaurs had been found from southern Gondwana -- the lower part of the ancient supercontinent Pangea.

"Unlike the ankylosaurs of the northern hemisphere, our new dinosaur possesses light armor, slender legs, and a smaller size," he said.

The fossilized plants discovered in the same region indicate that the climate was warmer when this dinosaur inhabited the place -- very different from the current cold climate prevailing in Patagonia.

#A New Species of Armored Dinosaur Discovered in Chile#Stegouros Elengassen#archeology#history#history news#nature#nature news

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

I would love a 👩🏻🔬 if you would!!! :)))

hmm should we go into historical geology and talk about mass extinctions for this one? yeah let’s do that!

There have been 6 mass extinction events in the last 450 million years [mya = million years ago]:

Ordovician-Silurian (�� 450 mya)

earliest known mass extinction

most life at that time was in the oceans

marine invertebrates were the major casualties

it is believed that movement from Gondwana (a supercontinent) into the southern hemisphere caused rising sea levels to rise and fall repeatedly over millions of years which would eliminate habitats and species

an ice age at this time as well as water chemistry changes could have also been factors here

Late Devonian (≈ 370 mya)

two events (Kellwasser and Hangenberg) combined to cause biodiversity loss

this spanned over a long time so there isn't a pinpoint cause to the extinction

its suggested that the spread of flora on land may have changed the environment making survival harder leading to species dying out

mostly impacted marine invertebrates (nearly wiped out the corals and didn't recover until the Mesozoic Era)

early bony fishes went extinct here as well

Permian-Triassic (252 mya)

aka Great Dying

marine invertebrates were the most impacted here (trilobites were killed off entirely here)

no life form was spared here (impacted ≈ 95% of marine species and ≈70% land vertebrates)

it took a long time for biodiversity recovery

believed to have happened due to gradual change in climate followed by catastrophe although the mechanisms behind this are still not known

Triassic-Jurassic (201 mya)

happened before the breakup of Pangea

there is no definitive answer as to what caused it although it is suggested that it could have been caused by climate change, asteroid impact, or enormous volcanic eruptions

more than 1/3 of marine species and most large amphibians went extinct

Cretaceous-Paleogene (66 mya)

also known as the Cretaceous-Tertiary Event (KT Event)

probably the mass extinction that is best understood

resulted in the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs, different amphibians, birds, reptiles, insects, and early mammals on land

resulted in damage of the oceans and the extinction of marine reptiles and ammonites (which at the time were one of the most diverse animal family)

it is estimated that about 75% of living species were wiped out

Holocene (Currently ongoing)

also known as Anthropocene Extinction due to the role that humans have had with ongoing biodiversity loss

started around 10,000 ya due to the dominance of modern humans

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

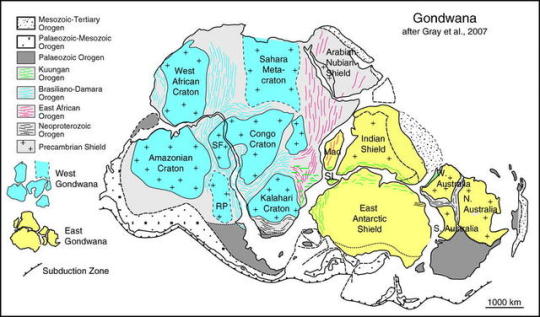

Gondwana (also called Gondwanaland) from SanskritGondavana(vana=forest, Gonda=Sanskrit name of a Dravidian people, i.e. “forest of the Gonds”) was an ancient supercontinent. Gondaoriginates from the Gondi or Gond people are a scheduled tribein central India that speak a language belonging to the Dravidian family of languages, and is most closely related to Telugu.

The landmasses that contemporary humans would recognize as making up Gondwana would include Africa, Australia, Antarctica, South America, the Indian Subcontinent and the Arabian Peninsula. This supercontinent existed from the Neoproterozoic era (approximately 550 million years ago) and broke apart during the Jurassic period (approximately 180 million years ago). This supercontinent was named by Eduard Suess in 1887, an Austrian scientist. He developed the concept for the name from the Gondwana region of central India, where geological formations match those of similar ages in the southern hemisphere. However, the name had been previously used by geologist H.B. Medlicott in 1872 when he described the Gondwana sedimentary sequences in the Triassic era.

I found this really interesting for two reasons, the first being that I was ignorant to the fact that there were multiple supercontinent besides Pangea, and two, I was interested to see the use of Sanskrit vocabulary in Geology.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok about the supercontinent thing -- Mauritus is on top of pieces of Gondwana. However, pretty much the entire southern hemisphere (and parts of asia) is formed from pieces of Gondwana, so this isn't nearly as interesting as the articles would lead you to believe. However, as Gondwana split apart into Africa, India, Australia, and Antarctica, strips of it just like,,,sank. And that's what Mauritus is on.

hey want to see something gorgeous but viscerally discomfiting?

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

Trees from Antarctica???

Ok everyone, I am incredibly excited to share with you all something ancient and mystical living amongst us today. It comes from a world that we will never know, but is still our own. This living memory may be one of the loneliest beings on earth as its species slowly dwindles and fails, but as the last survive, they provide testament to the resilience of life, the desire to survive, and evidence that the world around us will never be the same as it is in the moment we experience it. Today I share with you my favorite tree, Nothofagus moorei, the Antarctic beech.

The Antarctic beech is one of the only remaining species (I was told the only remaining but I question the reliability of the sign I read as it is my only source) native to Antarctica living today. Now, I know what you must be thinking. Yes, that Antarctica. The one with the lightless winter, miles thick ice sheets, and not a single tree to be found; let alone a deciduous tree that can grow to 50 metres in height. However, the southern extreme we know today wasn’t always that way.

(Photo by Neil Ross, 2013).

Tens of millions of years ago after the dissolution of the supercontinent Pangea, a new landmass was forming in the southern hemisphere. This continent, named Gondwana, was comprised of what is modern day Africa, South America, India, the Arabian Peninsula, Australia, and you guessed it, Antarctica. The dominant ecosystem across much of Gondwana was cool, subtropical and temperate rainforests. It was in this environment that the Antarctic beech came into being. Over the following millions of years, Gondwana started to break and the last to pieces drifted south together, what would become Australia and Antarctica. The tree is believed to have originated in the Antarctic portion, with small populations extending into cooler alpine regions of Australia. As the two landmasses finally split, the trees living on their native Antarctica slowly dwindled to extirpation as ice devoured their ancestral range. Today only a handful survive in elevated peaks scattered along eastern Australia.

Unfortunately, the trees are currently believed to be on their last legs in their final stronghold today. Evolving in a cooler climate, the increasingly warm Australian temperatures have robbed the trees almost entirely of their ability to reproduce sexually. In addition, their alpine homes were traditionally out of the reach of the bulk of the fires that regularly reset life in Australia’s lowland bush. In the past decades though, drier weather has promoted the spread of fires into the mountains. Unlike the majority of Australian flora, the beech is not resilient in the wake of fire. The final figurative “nail in the coffin” is the slow but steady erosion of the mountains that host them as time rolls along. With large root systems that favour deep soil, the thin mountain topsoil exposes the roots to mosses and parasitic plant and insect species. With some trees alive estimated to be up to 12,000 years old, the age of this ancient beauty is coming to an apparent end. Fortunately, its timeless message of consistent beauty in the face of constant change will long outlive it, and possibly even us who learn this lesson.

youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 Beautiful and Rare Species Found Only in Australia

The supercontinent of Gondwana split 180 million years ago. What would become Australia and Antarctica were part of a breakaway landmass from that breakup. Australia had completely separated by the time it travelled north on its own 30 million years ago. Since then, modifications to the land’s climate and physical isolation from the rest of the world have contributed to the development of Australia’s distinctive flora and fauna. Australia is the only place in the world where more than 80% of our flora, animals, reptiles, and frogs can be found.

About one million different native animal species can be found in Australia.

More than 80% of the country’s mammals, reptiles, and frogs, as well as the majority of its freshwater fish and 70% of its bird species, are exclusive to the Australian natural environment.

140 species of marsupials, such as kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, wombats, and the Tasmanian Devil, which is currently only found in Tasmania, are known as rare animals in Australia The dingo is the largest carnivorous mammal native to Australia and a wild dog.

About half of the 828 bird species found in Australia are unique to the country, with the huge, nearly two-meter-tall flightless emu being the most well-known.

Waterbirds, seabirds, and birds that live in open woodlands and forests all abound in Australia, including black swans, fairy penguins, kookaburras, and lyrebirds. Australia is home to 55 different species of colourful parrots, as well as a stunning array of cockatoos, rosellas, lorikeets, parakeets, and budgerigars.

More poisonous snake species, namely 21 of the 25 deadliest species, as well as two types of crocodiles, one saltwater and one freshwater, may be found in Australia than on any other continent.

The UNESCO World Heritage-listed Great Barrier Reef, which is the biggest coral reef system in the world, is also located in Australia. With our Exploring Our Ocean course, you may learn more about marine environments.

The predatory great white shark, which can reach a length of six metres, the enormous whale shark, which can grow to a length of 12 metres, and the box jellyfish, one of the world’s most venomous creatures are among the distinctive marine species.

Kangaroos, dingos, wallabies, wombats, and, of course, koalas, platypus, and echidnas are just a few of the well-known Australian wildlife. However, there is still a great deal that is unknown about the native creatures of Australia. In this article, we’ll look at 9 of the most unique animal species that are considered rare animals in Australia.

Why are Australian animals so unique?

Since Australia is geographically isolated in the southern hemisphere and is known as “The Land Down Under,” many of its animals are unique to Australia.

Around 250 million years ago, the Earth consisted of simply one enormous supercontinent called Pangaea, according to evolutionary history and fossil evidence.

After around 50 million years, this supercontinent split into the continents Laurasia and Gondwana. Monotremes and marsupials dominated the region of tropical forests in Gondwana at the time of this split, whereas placental mammals originated in Laurasia.

After thereafter, in the Jurassic Period, 180 million years ago, the western part of Gondwana, which comprised Africa and South America, split off from the eastern half, which contained Madagascar, India, Australia, and Antarctica. 40 million years later, India gradually broke away from Australia and Antarctica, forming the Indian Ocean. Australia and Antarctica slowly drifted to the south, where they were surrounded by immense oceans and cut off from the rest of the world.

Australia and Antarctica ultimately split apart 50 million years ago. Its environment changed as it moved away from the southern arctic zone, becoming warmer and dryer, and new animal species emerged and took over the landscape.

Eventually, monotremes and marsupials took over as the main mammals in Australia due to their less demanding reproductive systems and greater suitability for this new climate.

The original inhabitants of the Australian landmass no longer interacted with species from other continents, thus they continued to develop on their own. Australian native animals are distinctive from those found elsewhere in the globe because of their distinct evolution, which has produced several odd Australian animals.

Fitzroy River Turtle

Rheodytes leukops, a species of turtle from the Rheodytes genus, lives in the Fitzroy River. The other species in that genus, Rheogytes devisi, has long since gone extinct, leaving only them as the remaining species. In Queensland, Australia’s Fitzroy River and its tributaries are where you can find them.

Fitzroy River turtles spend roughly 21 days submerged. They are remarkably adaptable creatures. The other species of their genus is extinct, leaving only these critters as survivors. The extinct species was known by the name “Rheodytes devisi”. September to October is the time when they lay their eggs.

These turtles are classified as Vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List. Because of habitat degradation, predators, and population decrease, they are classified as Vulnerable by IUCN. These turtles are frequently attacked, along with their nests, by foxes, pigs, and goannas.

Because predators frequently attack and totally destroy their nest, there are no surviving hatchlings left, which is a major factor in their Vulnerable conservation status. Its population growth is challenging for this species because of this.

To get the most out of their toe daggers, cassowaries can jump feet first, so their claws can slash downward in mid-air towards their target.

Australian Southern Cassowary

This bird, which descended from dinosaurs, has been designated as the “most hazardous bird on Earth.” Most human attacks in which victims are kicked, shoved, jumped on, and headbutted are motivated by the need to provide food for the bird. Their 12-centimeter middle claw functions as a dagger and may cause significant harm.

Be on the lookout for the elusive cassowary if you happen to be in Tropical North Queensland. It’s a big, colourful bird that has a prehistoric appearance, if that answers your question. The cassowary may reach a height of 180 cm and often weighs 60 kg. With its distinctive appearance, the cassowary is simple to identify. Especially its blue neck and the helmet-shaped protrusion on its head.

They’re great sprinters too, with a top running speed of 50 km/h through dense forest. Not only that, they’re good swimmers, with the ability to cross wide rivers and swim in the sea. That’s one animal you don’t want to be chased by!

Saltwater Crocodile

It is the largest reptile in the world, with a known maximum weight of over 1000 kg, and has the strongest bite of any species. This endangered species mostly consumes small reptiles, turtles, fish, wading birds, wild pigs, and livestock including cattle and horses.

Did you know? A crocodile cannot sweat, so instead, it relies on the process of thermoregulation to control its body temperature. To avoid overheating, it will either go into the water or lie still with jaws agape, allowing cool air to circulate over the skin in its mouth. That’s why you often see them happily basking in the sun with their mouths wide open. This process is crucial for many bodily functions including digestion and movement.

Mistletoebird

The little Mistletoebird, often called the Australian Flowerpecker, is the sole member of the Dicaeidae family of flowerpeckers that lives in Australia. Males have a bright red throat and chest, a white belly with a central dark streak, and a bright red undertail in addition to having a glossy blue-black head, wings, and upperparts. Females have a pale crimson undertail and a belly streaked with the grey that is white above. Young birds are female-like, but whiter and with an orange-coloured bill as opposed to a dark one. These birds fly quickly and erratically, alone or in couples, typically high in or above the canopy.

To its diet of mistletoe berries, the mistletoebird has developed a strong adaptation. The rudimentary digestive system it has allows it to quickly process the berries, breaking down the fleshy outer sections and excreting the sticky seeds onto branches. It lacks the muscular gizzard (food-grinding organ) of other birds. After then, the seed might quickly grow into a new plant. The mistletoebird does this to guarantee a steady supply of its primary meal. In order to feed its young, it will also catch insects.

The mistletoebird is widespread over mainland Australia and can be found wherever mistletoe is present. It plays a significant role in the spread of this plant species. Eastern Indonesia and Papua New Guinea also contain it.

Tasmanian Devil

The Tasmanian Devil is listed as an endangered species in Australia. Their tail, where they store fat, may hold up to 40% of their body weight per day, thus you can gauge their health by the size of it! Although they don’t have the same terrifying appearance as other creatures in Australia, they have a bite that is so strong that it may easily break bones.

These creatures are worth viewing, despite the fact that some people may find them cute and others may find them horrifying. It is a carnivore that can only be found in the woods of Australia. The intriguing thing about its name is that these creatures were discovered in Tasmania for the first time, and due to their obnoxious yells and frightful growls, people thought they were quite diabolical. It is also known as Tasmanian Devils. In Australia, don’t miss viewing these adorable devils.

While travelling through Tasmania, you have the best chance of seeing Tasmanian devils in the wild. At Cradle Mountain-Lake St. Clair National Park, Devils Cradle, and Tasmanian Devil Unzoo, which offers a 4WD tour on which you may follow the devil’s movements, you can get up close and personal with these wild animals. There are other zoos and sanctuaries all around the country. Read Full Article: 9 Beautiful and Rare Species Found Only in Australia

1 note

·

View note

Text

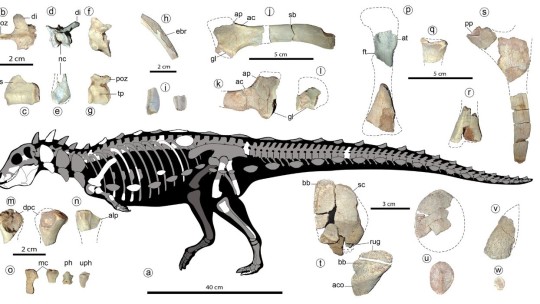

Small, prickly dinosaur discovered in South America reveals an unknown lineage

Fossils of a small, prickly dinosaur recently discovered in South America may represent an entire lineage of armored dinosaurs previously unknown to science.

The newly discovered species, Jakapil kaniukura, looks like a primitive relative of armored dinosaurs like Ankylosaurus or Stegosaurus, but it came from the Cretaceous, the last era of the dinosaurs, and lived between 97 million and 94 million years ago. That means a whole lineage of armored dinosaurs lived in the Southern Hemisphere but had gone completely undetected until now, paleontologists reported in a new study.

J. kaniukura weighed about as much as a house cat and had a row of protective spines running from its neck to its tail and probably grew to about 5 feet (1.5 meters) long. It was a plant eater, with leaf-shaped teeth similar to those of Stegosaurus.

Related: Massive bulldog-faced dinosaur was like a T. rex on steroids

Paleontologists at the Félix de Azara Natural History Foundation in Argentina uncovered a partial skeleton of a subadult J. kaniukura in the Río Negro province in northern Patagonia. The dinosaur likely walked upright and sported a short beak capable of delivering a strong bite. It probably would have been able to eat tough, woody vegetation, the researchers reported Thursday (Aug. 11) in the journal Nature Reports (opens in new tab).

The new dinosaur joins Stegosaurus, Ankylosaurus and other armor-backed dinosaurs in a group called Thyreophora. Most thyreophorans are known from the Northern Hemisphere, and the fossils from the earliest members of this group are found mostly in Jurassic-period rocks from North America and Europe from about 201 million years ago to 163 million years ago.

The discovery of J. kaniukura “shows that early thyreophorans had a much broader geographic distribution than previously thought,” Félix de Azara Natural History Foundation paleontologists Facundo J. Riguetti and Sebastián Apesteguía and University of País Vasco paleontologist Xabier Pereda-Suberbiola wrote in the new paper. It was also surprising that this ancient lineage of thyreophorans survived all the way into the Late Cretaceous in South America, they added. In the Northern Hemisphere, these older types of thyreophorans seem to have gone extinct by the Middle Jurassic. On the southern supercontinent Gondwana, however, they apparently survived well into the Cretaceous. (Later thyreophorans survived longer. Ankylosaurus, for example, went extinct with the rest of the nonavian dinosaurs 66 million years ago.)

The name “Jakapil” comes from a word meaning “shield bearer” in the Puelchean or northern Tehuelchean Indigenous language of Argentina. “Kanikura” comes from the words meaning “crest” and “stone” in the Indigenous Mapudungun language.

You can see what J. kaniukura might have looked like when it was alive, thanks to this computer simulation from Gabriel Díaz Yantén, a Chilean paleoartist and paleontology student at Río Negro National University.

Originally published on Live Science.

New post published on: https://livescience.tech/2022/08/13/small-prickly-dinosaur-discovered-in-south-america-reveals-an-unknown-lineage/

0 notes

Audio

"G O N D W A N A” - the ancient supercontinent that existed in the southern hemisphere, the mystical land that still kindles the imagination of scientists and travellers. The composition is inspired by • AINU • journey to Tasmania - the land which was a part of Gondwana. The beauty of the place with giant tree ferns encourages reflection on the necessity to protect our Planet to preserve it for future generations. It's our responsibility to start now. Planet Earth Narration: Special thanks to Larry Don Ashmore - our American friend from New Zealand (a descendant of the Cherokee Nation). All sounds of nature was recorded live by AINU in Tasmania '2016. Electronic instruments and special effects composed and made by AINU. Music composed and recorded by • AINU • in a superior Sound Quality. Mastered by • AINU • in his own Studio • December'2017 ©2017 • AINU • world music | www.ainu.net

#- AINU -#AINU#AINU world music#Gondwana#Tasmania#Przemyslaw Goc#PGoc#PrzemyslawGoc#Oceania#NewZealand#ferntree#AINUworldmusic#HIT#Music#Ambient#chillout#nativeamericanflute#flute#ethnobeat#ethnic#etniczna#muzyka#filmowa#videoclip#muzykapolska

1 note

·

View note

Text

Long-Lost Continent Discovered Beneath The Mediterranean

Geologists have discovered a long-lost continent that’s been hiding beneath southern Europe for millions of years. Nope, it’s not Atlantis, it’s actually a Greenland-sized chunk of continental crust known as Greater Adria that’s been found lurking in the Mediterranean.

“Forget Atlantis. Without realizing it, vast numbers of tourists spend their holiday each year on the lost continent of Greater Adria,” said lead researcher Douwe van Hinsbergen in a statement.

It was discovered by a team of researchers from Utrecht University in the Netherlands who embarked on a mission to document the messy geology of the Mediterranean, publishing their findings in the journal Gondwana Research.

All of Earth’s modern-day continents were once joined together in a supercontinent known as Pangea until it began to break apart about 175 million to 200 million years ago to form Gondwana (which eventually broke into Africa, South America, Antarctica, India, and Australasia) and Laurasia (Eurasia and North America).

Reconstruction of Greater Adria, Africa and Europe, about 140 million years ago. Douwe van Hinsbergen and colleagues/Utrecht University

Then, around 140 million ago, Greater Adria separated from North Africa and plunged into the mantle under southern Europe at a speed of centimeters per year. As the continent slid under Europe, the top layers of sedimentary rock “scraped off” and formed the mountain belts of the Apennines, parts of the Alps, the Balkans, Greece, and Turkey.

While most of the continent is underwater, we can still see the legacy of the ancient continent in parts of the Mediterranean today.

“Most mountain chains that we investigated originated from a single continent that separated from North Africa more than 200 million years ago,” van Hinsbergen said. “The only remaining part of this continent is a strip that runs from Turin via the Adriatic Sea to the heel of the boot that forms Italy.”

The discovery of Greater Adria is based on a decade of work by the team. After studying the age and magnetic properties of rocks around the region, they then created models to track the movements of Earth’s tectonic plates.

Studying the tectonics of the Mediterranean is no easy task. First of all, it’s spread across dozens of different countries, each with their own geological surveys and deep-rooted ideas of their geological past. Secondly, as you can tell from its rugged landscapes, this is a land that’s fiendishly complicated, geologically speaking.

“It is quite simply a geological mess: everything is curved, broken, and stacked. Compared to this, the Himalayas, for example, represent a rather simple system,” explained van Hinsbergen. “There you can follow several large fault lines across a distance of more than 2,000 kilometers.”

This isn’t the first lost continent we’ve discovered. In 2017, researchers confirmed the new seventh continent of Zealandia, most of which lies underwater in the Southern Hemisphere. Just last year, researchers used gravity-mapping satellites to detect the remnants of long-lost continents beneath the ice sheets of Antarctica. Scientists even think there’s a possibility that Earth will once again form a supercontinent in 50 to 200 million years. It even has a name: Amasia.

Original Article : HERE ;

The post Long-Lost Continent Discovered Beneath The Mediterranean appeared first on MetNews.

Long-Lost Continent Discovered Beneath The Mediterranean was originally posted by MetNews

0 notes

Photo

Oldest southern continent animal unearthed

The oldest land animal to have been discovered from the ancient southern continent of Gondwana has just been reported in the journal African Invertebrates. It dates from around the late Devonian or early Carboniferous, 360 million years ago. At the time, most of Earth's landmass was partitioned over two supercontinents - the northernmost, Laurasia, straddled the equator while Gondwana sat at the south pole. It is thought that plant life first colonised land in the Ordovician period, 450 million years ago. Then, during the Siluran, and it is thought that the first animals began to move from sea to land. They were simple compost-generating invertebrates - primitive insects and millipedes. They in turn were followed by more complex animals, like scorpions. Evidence is that scorpions moved from the oceans onto land (terrestrialisation) during the Devonian, and a few fossilised examples of Devonian scorpions have previously been reported, but all from rocks that were part of Laurasia. This is not so surprising. Scorpions today live in warm environments, and are not generally found at high latitudes (although some do exist in Patagonia).

The Gondwana scorpion (which has been named Gondwanascorpio emzantsiensis), was found by Dr Robert Gess from Wits University, Johannesburg, in 360 million year old Devonian Witteberg Group rocks near Grahamstown. These were part of Gondwana back then, separated from Laurasian by the deep Tethys ocean. "Evidence on the earliest colonisation of land animals has up till now come only from the northern hemisphere continent of Laurasia, and there has been no evidence that Gondwana was inhabited by land living invertebrate animals at that time,” says Dr Gess.

The finding demonstrates that there were scorpions living in high latitude Gondwana, the earliest animals found there thus far, but also implies a terrestrial ecosystem with prey for them to feed upon. The latitudes are higher even than the habitats of the modern day Patagonian scorpions.

It seems that the lack of Gondwana animal fossils is as much a feature of the lack of sedimentation, and hence burial and preservation, later during the Carboniferous as lack of organisms. At that time southern Africa, the location of the fossil find, was slowly wandering across the south pole, with much of the landmass glaciated. But Gess's find demonstrates that there were terrestrial ecosystems in place, and (like Laurasia) animal life was likely diversifying across the southern continent.

~SATR (follow me on twitter @sim0nredfern)

Image: the sting of Gondawanascorpio, about 2 cm long. (Credit: Dr Robert Gess)

Original paper: http://africaninvertebrates.org/ojs/index.php/AI/article/view/284

#Science#Scorpion#Fossil#Geology#Gondwana#Research#animal#nature#landscape#plate tectonic#Fossilfriday#the earth story

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient ‘crazy beast’ from Madagascar had mismatched body and teeth from ‘outer space’

The oldest complete mammal fossil from the Southern Hemisphere is puzzling scientists with its mismatched body, strange skull holes and teeth that look like they’re “from outer space.”

The new fossil, reported today (April 29) in the journal Nature, is the oldest (and only) nearly complete skeleton from an extinct group of mammals known as Gondwanatherians. This mysterious bunch lived alongside the dinosaurs on the southern supercontinent of Gondwana. They’re known from a smattering of teeth and bone fragments, a single skull and the new, remarkable skeleton of an animal whose discoverers have dubbed the “crazy beast.”

The fossil is from northwestern Madagascar and dates back 66 million years, to the end of the Cretaceous period. Madagascar was already an island at the time, having drifted away from Africa by 88 million years ago, and the animals that lived there were completely bizarre, said David Krause, the senior curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, who led the new research.

Related: Image gallery: 25 amazing ancient beasts

Strange island

Among the animals found on Madagascar at this time were: the predatory, buck-toothed dinosaur Masiakasaurus knopfleri; a frog wider than a No. 2 pencil is long that may have eaten baby dinosaurs and was named Beelzebufo ampinga, or “devil frog”; and a crocodile with a short snout and bumpy teeth that probably ate plants.

“We actually think we had an herbivorous crocodile, and it doesn’t get much weirder than that,” Krause said during a press briefing.

Well, except maybe for the new mammal, Adalatherium hui. A field expedition led by Krause and his colleagues dug the stunning skeleton out of the ground in 1999, completely by accident. They were trying to collect a nearby crocodile skeleton, said Raymond Rogers, professor and chair of geology at Macalester College in Minnesota, who participated in the research.

“We recovered a skeleton not knowing we had a mammal beside it,” Rogers told reporters.

It took months to remove the possum-size skeleton from the rock, but the results are unprecedented. Most of the skeleton is preserved, except for part of the back of the skull and some pieces of the hips. Never before has so much of a Gondwanatherian been found. The previous best-preserved specimen was a skull of a large-eyed herbivore reported in the journal Nature in 2014 by Krause and his team. The researchers attribute the pristine preservation of the newfound A. hui to a mudflow that suddenly buried the creature. Such mudflows seem to have occurred seasonally in Madagascar at the time.

“It was probably buried alive by one of these mudflows,” Rogers said.

The name of the mammal comes from the Malagasy word for “crazy” and the Latinized Greek for “beast.” The species name hui is in honor of Yaoming Hu, a vertebrate paleontologist who died in 2008.

Researchers David Krause (left front) and team carry a plaster jacket containing the skeleton of the early mammal now called Adalatherium hui. (Image credit: Curtesy of National Geographic Society/Maria Stenzel)

Weird mammal

A. hui probably looked a bit like a badger, but it was like no mammal alive today. Most early mammals had sprawled-out legs, a bit like those of today’s crocodiles. A. hui‘s back legs were sprawled out, too. But its front legs were aligned under its body, like a cat’s or a dog’s.

Related: Images: See the evolution of early mammals through time

This alignment is so unheard-of that the researchers studying A. hui have no idea how the creature would have moved. It had strong back muscles that indicate that its back probably wiggled side-to-side as it walked, said study co-researcher Simone Hoffmann, an anatomist at the New York Institute of Technology.

“It probably means it walked really differently from anything that lived in the past or that is living today,” Hoffmann told reporters.

A. hui’s teeth were similarly confounding, said Krause, who compared them to something from outer space. Their bumps and ridges match no known teeth patterns in any extinct or living mammals. The animal had prominent incisors, something like a rodent, but the incisors are strange, with enamel only on the cheek side. Still, Krause said, the teeth suggest the animal was likely an herbivore that used its incisors for gnawing.

The skull of A. hui was weirdly pockmarked with holes. Some of these were clearly openings to allow nerves and blood vessels to pass to the snout. The number of these holes was indicative of a very sensitive snout, Krause said, leading the researchers to suspect that Adalatherium‘s nose was well-whiskered. The animal’s strong claws suggest it was a digger, so perhaps these nerves detected rich sensations in dark underground burrows, Krause speculated.

Another of the holes, a large opening on top of the snout, is a complete mystery, Krause said. Nothing like it has been seen on a mammal skull before. It was probably covered with cartilage, but researchers don’t know why it existed.

A mounted cast skeleton of Adalatherium hui. This early mammal would have wiggled from side to side as it moved during the late Cretaceous period. (Image credit: Courtesy of Triebold Paleontology)

Evolution of mammals

No living descendants of A. hui survive today. In fact, none of today’s mammals on Madagascar are related to the Cretaceous mammals found so far on the island, Krause said. This suggests that all of Madagascar’s mammals died off in the end-Cretaceous asteroid impact that also destroyed the non-avian dinosaurs. Today’s Madagascar mammals probably descended from animals that later floated on giant rafts of vegetation from coastal Africa, Krause said.

Related: Wipeout: History’s most mysterious extinctions

But the discovery of Adalatherium suggests that even when the dinosaurs roamed, islands led to weird evolution. Scientists have long known that species isolated on islands tend to evolve in strange ways. Islands might spawn giants like the fearsome Komodo dragon, for example, or miniatures like the now-extinct pygmy mammoths that once roamed Crete. The Cretaceous weirdos of Madagascar suggest something similar was going on. A. hui, for example, weighed around 6.8 lbs. (3.1 kilograms), 100 times heavier than the mouse-sized mammals that make up most of the earliest mammals on Earth, Krause said. It is the third-largest mammal ever found from the Southern Hemisphere Mesozoic (the era spanning from 250 million to 65 million years ago).

Researchers are still working to understand A. hui‘s manner of movement and weird adaptations. They also have plenty more fossils from Madagascar to work through. Since 1993, the team has excavated more than 20,000 fossil specimens from the region. Highlighting the rarity of a find like A. hui, only 12 of those are mammal specimens.

Originally published on Live Science.

Source link

Tags: ancient, Beast, Body, crazy, Madagascar, mismatched, outer, space, teeth

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2VOw2TV via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

The Mystery of India’s Rapid Move toward Eurasia 80 Million Year rugged s Ago

www.inhandnetworks.com

In this artist’s rendering, the left image shows what Earth looked like more than 140 million years ago, when India was part of an immense supercontinent called Gondwana. The right image shows Earth today.

A newly published study from MIT geologists reveals that a double subduction system may have driven India to drift at high speed toward Eurasia some 80 million years ago.

In the history of continental drift, India has been a mysterious record-holder.

More than 140 million years ago, India was part of an immense supercontinent called Gondwana, which covered much of the Southern Hemisphere. Around 120 million years ago, what is now India broke off and started slowly migrating north, at about 5 centimeters per year. Then, about 80 million years ago, the continent suddenly sped up, racing north at about 15 centimeters per year — about twice as fast as the fastest modern tectonic drift. The continent collided with Eurasia about 50 million years ago, giving rise to the Himalayas.

For years, scientists have struggled to explain how India could have drifted northward so quickly. Now geologists at MIT have offered up an answer: India was pulled northward by the combination of two subduction zones — regions in the Earth’s mantle where the edge of one tectonic plate sinks under another plate. As one plate sinks, it pulls along any connected landmasses. The geologists r intelligent substation easoned that two such sinking plates would provide twice the pulling power, doubling India’s drift velocity.

The team found relics of what may have been two subduction zones by sampling and dating rocks from the Himalayan region. They then developed a model for a double subduction system, and determined that India’s ancient drift velocity could have depended on two factors within the system: the width of the subducting plates, and the distance between them. If the plates are relatively narrow and far apart, they would likely cause India to drift at a faster rate.

The group incorporated the measurements they obtained from the Himalayas into their new model, and found that a double subduction system may indeed have driven India to drift at high speed toward Eurasia some 80 million years ago.

“In earth science, it’s hard to be completely sure of anything,” says Leigh Royden, a professor of geology and geophysics in M remote access IT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. “But there are so many pieces of evidence that all fit together here that we’re pretty convinced.”

Royden and colleagues including Oliver Jagoutz, an associate professor of earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences at MIT, and others at the University of Southern California have published their results this week in the journal Nature Geoscience.

What drives drift?

Based on the geologic record, India’s migration appears to have started about 120 million years ago, when Gondwana began to break apart. India was sent adrift across what was then the Tethys Ocean — an immense body of water that separated Gondwana from Eurasia. India drifted along at an unremarkable 40 millimeters per year until about 80 million years ago, when it suddenly sped up to 150 millimeters per year. India kept up this velocity for another 30 million years before hitting the brakes — just when the continent collided with Eurasia.

“When you look at simulations of Gondwana breaking up, the plates kind of start to move, and then India comes slowly off of Antarctica, and suddenly it just zooms across — it’s very dramatic,” Royden says.

In 2011, scientists believed they had identified the driving force behind India’s fast drift: a plume of magma that welled up from the Earth’s mantle. According to their hypothesis, the plume created a volcanic jet of material underneath India, which the subcontinent could effectively “surf” at high speed.

However, when others modeled this scenario, they found that any volcanic activity would have lasted, at most, for 5 million years — not nearly enough time to account for India’s 30 million years of high-velocity drift.

Squeezing honey

Instead, Royden and Jagoutz believe that India’s fast drift may be explained by the subduction of two plates: the tectonic plate carrying India and a second plate in the middle of the Tethys Ocean.

In 2013, the team, along with 30 students, trekked through the Himalayas, where they collected rocks and took paleomagnetic measurements to determine where the rocks originally formed. From the data, the researchers determined that about 80 million years ago, an arc of volcanoes formed near the equator, which was then in the middle of the Tethys Ocean.

A volcanic arc is typically a sign of a subduction zone, and the group identified a second volcanic arc south of the first, near where India first began to break away from Gondwana. The data suggested that there may have been two subducting plates: a northern oceanic plate, and a southern tectonic plate that carried India.

Back at MIT, Royden and Jagoutz developed a model of double subduction involving a northern and a southern plate. They calculated how the plates would move as each subducted, or sank into the Earth’s mantle. As plates sink, they squeeze material out between their edges. The more material that can be squeezed out, the faster a plate can migrate. The team calculated that plates that are relatively narrow and far apart can squeeze more material out, resulting in faster drift.

“Imagine it’s easier to squeeze honey through a wide tube, versus a very narrow tube,” Royden says. “It’s exactly the same phenomenon.”

Royden and Jagoutz’s measurements from the Himalayas showed that the northern oceanic plate remained extremely wide, spanning nearly one-third of the Earth’s circumference. However, the southern plate carrying India underwent a radical change: About 80 million years ago, a collision with Africa cut that plate down to 3,000 kilometers — right around the time India started to speed up.

The team believes the diminished plate allowed more material to escape between the two plates. Based on the dimensions of the plates, the researchers calculated that India would have sped up from 50 to 150 millimeters per year. While others have calculated similar rates for India’s dri4g lte router dual SIMft, this is the first evidence that double subduction acted as the continent’s driving force.

“It’s a lucky coincidence of events,” says Jagoutz, who sees the results as a starting point for a new set of questions. “There were a lot of changes going on in that time period, including climate, that may be explained by this phenomenon. So we have a few ideas we want to look at in the future.”

Publication: Oliver Jagoutz, et al., “Anomalously fast convergence of India and Eurasia caused by double subduction,” Nature Geoscience, (2015); doi:10.1038/ngeo2418

Image: iStock (edited by MIT News)

ct scanners remote monitoring, mri remote monitoring, healthcare, wireless atm, branch networking, retail, digital signage, wastewater treatment, remote monitoring, industrial automation, automation, industrial transport, inhand, inhand network, inhand networks, Industrial IoT, IIoT, Industrial IoT Manufacturer, Industrial IoT Connectivity, Industrial IoT Products, Industrial IoT Solutions, Industrial IoT Products, industrial IoT Gateway, industrial IoT router, M2M IoT gateway, M2M IoT router, industrial router, Industrial IoT Router/Gateway, industrial IoT Gateway, industrial LTE router, Industrial VPN router, Dual SIM M2M router, Entry level Industrial Router, Cost effective, 3G 4G LTE, WiFi, VPN industrial router for commercial and industrial and M2M/IoT applications, Industrial 3G Router, Industrial 3g router, UMTS router, VPN routerIndustrial 3g router, UMTS router, VPN router, DIN-Rail router, cellular router, Industrial IoT Gateway, Industrial IoT Gateway, M2M gateway, VPN gateway, remote PLC programming, Industrial Cellular Modem, Cellular modem, data terminal unit, 3g modem, Industrial 3G Cellular Modem, 3g modem, industrial cellular modem3g modem, industrial cellular modem, industrial wireless modem, data terminal unit, Android Industrial Computer, Android Industrial Computer, Vending PC, Vending Telemetry, Vending Telemeter, Android Industrial Computer, Android Industrial Computer, Vending PC, Vending Telemetry, Vending Telemeter, Touchscreen & Vending PC, Vending Touchscreen, Vending Telemeter, Vending Telemetry, Vending Computer, Industrial LTE Router, industrial IoT Gateway, industrial LTE router, Industrial VPN router, Dual SIM M2M router, Industrial IoT Router/Gateway, industrial IoT Gateway, industrial LTE router, Industrial VPN router, Dual SIM M2M router, Industrial LTE Router, Industrial LTE router, industrial 4G/3G router, router industrial, cost-effective industrial LTE router, Industrial LTE Router, Industrial LTE router, industrial IoT router, router industrial, cost-effective M2M router, M2M LTE router, Industrial 3G Router , Industrial 3g router, industrial wireless router, VPN router, DIN-Rail router, cellular router, Industrial 3G Router , Industrial 3g router, industrial wireless router, VPN router, DIN-Rail router, cellular router, Distribution Power Line Monitoring System, Overhead Line Monitoring, Distribution Power Line Monitoring, Fault detection & location, Grid Analytics System, Remote Machine Monitoring & Maintenance System, IoT Remote Monitoring,

#intelligent vending machine#IoT gateway#Line Monitoring#MV sensor#power sensor#Prognostics and Health Management#programmable m2m gateway#smart grid sensor

0 notes

Text

Glaciations

(Though this post makes reference to the district of Thunder Bay, ON, I hope this may be of general interest to many.)

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (May 28, 1807–December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-American biologist and geologist, born in Switzerland but who emigrated to the US in 1847.

In 1837 Agassiz was the first to scientifically propose that the Earth had been subject to a past ice age, when he proposed to the Helvetic Society that ancient glaciers had not only flowed outward from the Alps, but that even larger glaciers had simultaneously encroached southward on the plains and mountains of Europe, Asia and North America, smothering much of the northern hemisphere in a prolonged Ice Age.

Agassiz conceived of a single climatic/geologic event, the “Ice Age”, a term now obsolete in view of subsequent work in the paleoclimatic, glaciological and geological sciences.

Most is known about the most recent events of earth history because each new event largely modifies and destroys evidence of earlier events. Present landscapes can be likened to a palimpsest, an ancient parchment used many times, the most recent writing being most clear, earlier texts being progressively less well seen as each new phase of writing partially obscures the earlier ones. However, as in a palimpsest, evidence of earlier events do remain in present landscapes, though fragmented and incomplete. Piecing together the history of past events is like a very large scale detective story.

Ancient Glaciations

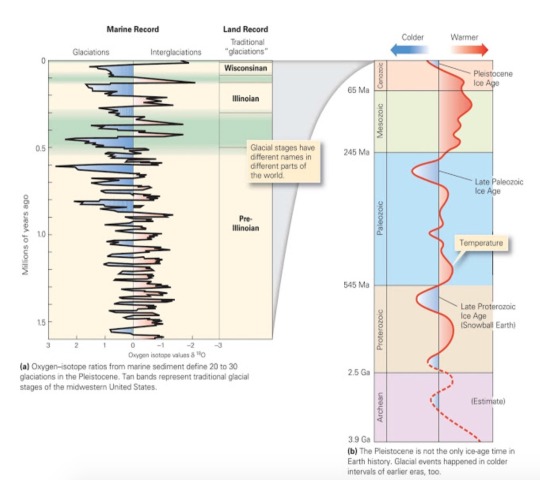

Glacial sediments, identical to those of today but often metamorphosed in subsequent history, have been identified in many geological strata, spanning an immense period of time (Figure 1), certainly in the Late Proterozoic and Late Palaeozoic. Very little detail of these major glaciation events remain, but some do.

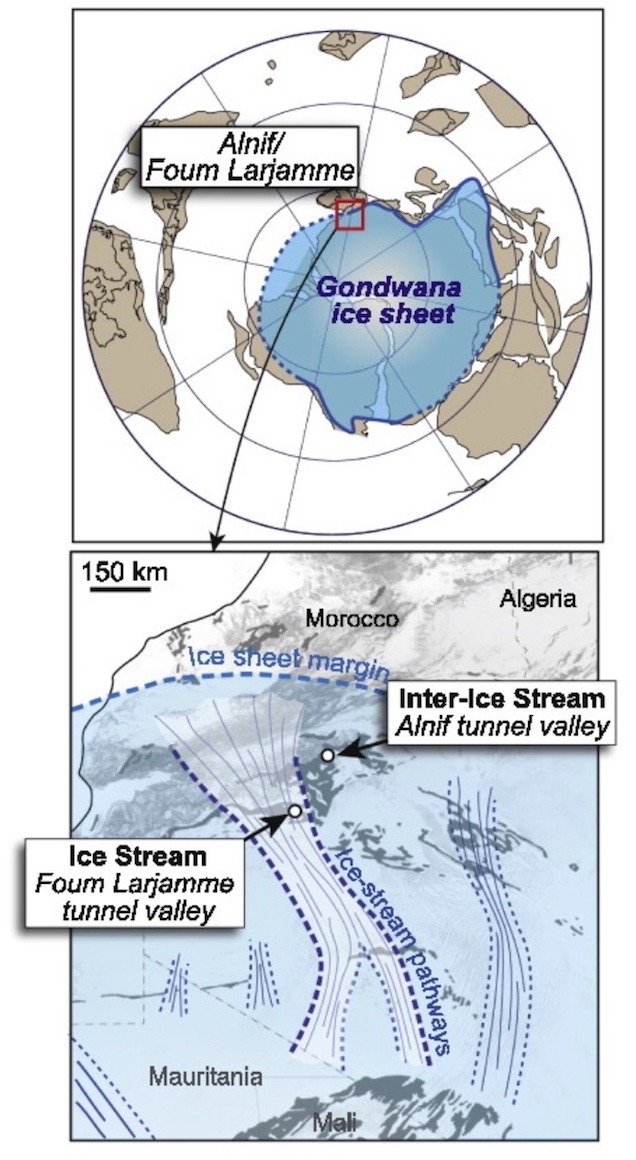

One fascinating and, for most, mind bending, insight into ancient glaciations is to be found in southern Morocco, where evidence of northward flowing tunnel valleys has been found in the bare rock deserts of the western edge of the Sahara, in late Ordovician strata (488.3-443.7 million years ago) that include glacial diamictons (glacial ground moraine). These glacial sediments are of the Hirnantian Glaciation, and occurred at a time when most of the world’s land masses were concentrated in the southern hemisphere as the supercontinent, Gondwana, centred on the south pole (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The ice cap extended outwards almost to the 40 degree S parallel, the line marking the maximum extent of ice, crossing what is now Morocco. Today, the city of Marrakesh and the coastal town of Essaouira lie on that ancient margin.

Pleistocene Glaciation

Most is known about the Pleistocene ice age, since far more evidence of this glaciation remains. In Europe, work in the Alps identified four major phases of glacial advance and retreat from the mountains and out on to the surrounding plains. This model became the stereotype, and elsewhere in the world, evidence for four glaciations was sought, and found.

However, as Figure 2 shows, the evidence reveals a far more complex oscillation of temperature with 20-30 glacial episodes. Figure 2

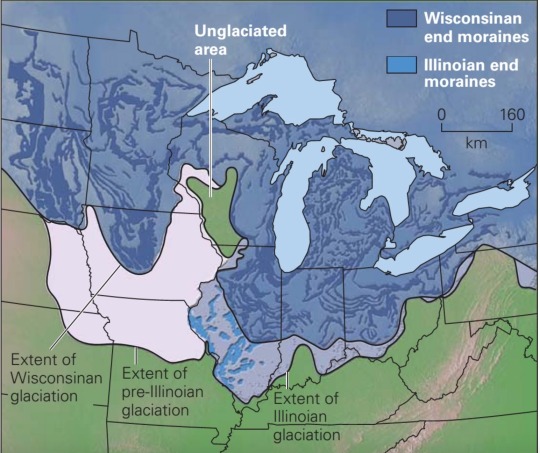

Of these, the traditional four major phases were identified in North America, though it is now recognized that there were many sub-phases within these. These are the

Wisconsinan - maximum extent 22,000 years ago Illinoian - maximum extent 400,000 years ago Kansan - maximum extent 800,000 years ago Nebraskan - maximum extent 1,300,000 years ago

Again, much more is known about the events of the Wisconsinan glaciation than earlier Pleistocene glaciations, each event covering very much the same territory, the only evidence of the earlier events being found along the margins of the ice sheet where a succeeding event failed to cover portions of land covered by the earlier one. Figure 3 shows the Wisconsinan and Illinoain ice margins in the central midwest US, with a portion covered only by pre-Illinoian events still preserved. Figure 3

Particularly noteworthy is a part of central Wisconsin that appears to have been missed by all Pleistocene glaciations.

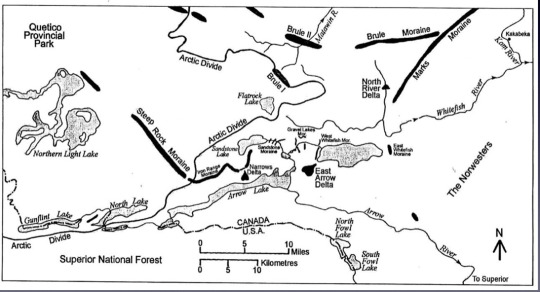

The Region of NW Ontario, N. Minnesota and the Lake Superior Basin

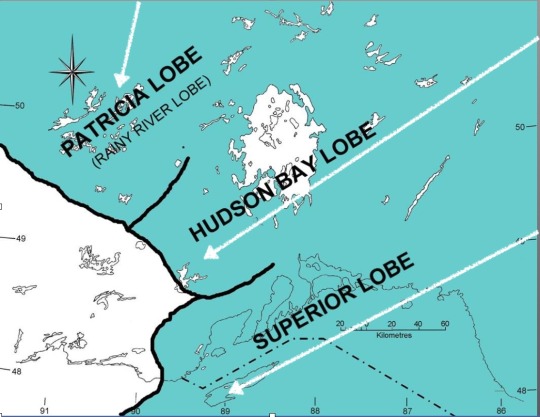

Though an ice sheet may appear to be a single mass of ice, as in both the oceans and the atmosphere, internal fluid motion, both horizontal and vertical, renders the ice sheet a collection of identifiable ice flows which become more obvious along the ice margin where lobes of ice flow outwards like the pseudopodia of an amoeba. Individual ice lobe history is complex, one lobe advancing while another wastes away in place, a lobe perhaps crossing the same ground as a previous one, but from a different direction.

The region in which we live was affected by an interplay of three lobes of ice, the Patricia (or Rainy River) Lobe coming from just east of north, the Hudson Bay Lobe coming from the northeast across the Lake Nipigon basin and the Superior Lobe, coming across the North Shore and flowing southeast down the Lake Superior basin to encroach on Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Figure 4

The maximum extent of Wisconsin ice occurred about 21,000 years ago, after which retreat took place. Of course, ice does not in fact “retreat” in the sense of going backwards. If the rate of supply from the flow is greater than the rate of melt, the ice margin “advances”. If the rate of melt exceeds the rate of supply, the ice margin “retreats”. Military analogies are not always the most helpful.

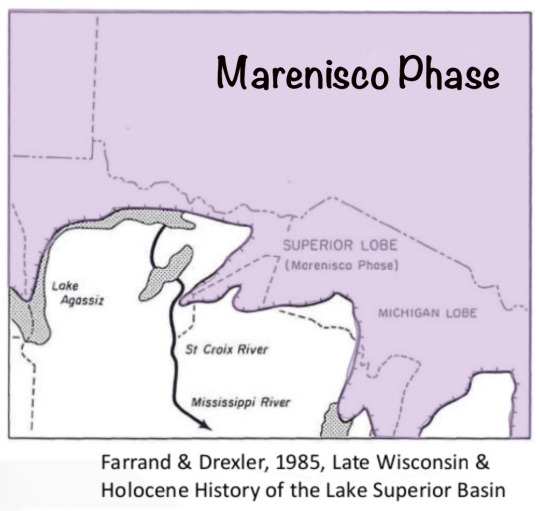

During general retreat, when ice was melting back from it maximum position and recently glaciated land was being exhumed from beneath ice, seven major re-advance or pause phases have been identified, very likely coincident with cooling trends within the overall steady rise of average world temperature. The Hewitt and St.Croix (19,500 yrs ago) phases, identifiable in the Minneapolis area, were followed by the Automba phase (18,870-18,000 years ago). There followed the Split Rock phase (17,010-16,680 years ago. The Marenisco phase occurred 13,580 years ago (Figure 5a).

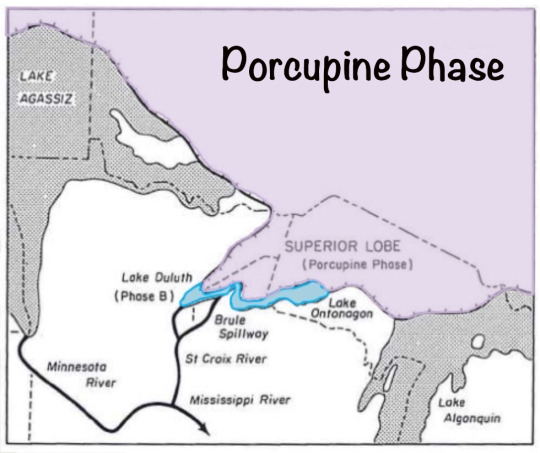

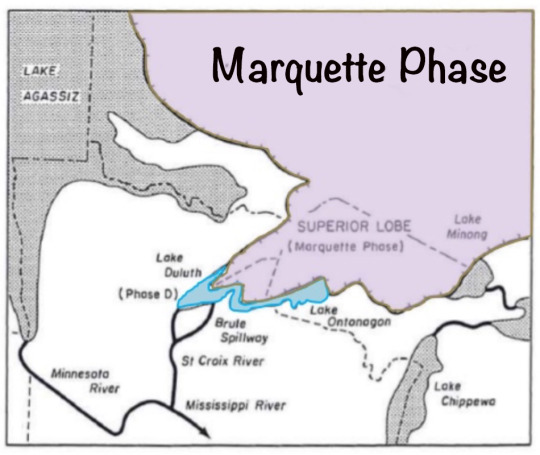

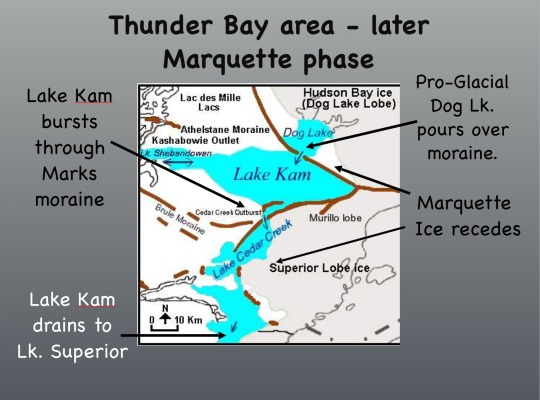

The Porcupine Phase occurred 12,820 years ago (Figure 5b) and the Marquette Phase occurred 11,600 years ago (Figure 5c). Figure 5b

Figure 5c

Once again, most is known about the Marquette Readvance, the last ice to affect the region and the one from which many features of the present landscape of the Thunder Bay area are derived.

During the Marquette Readvance, the Patricia, Hudson Bay and Superior lobes advance together, coming to a halt (rate of ice supply being equal to the rate of melt) just west and north of the location of the City of Thunder Bay, which then lay under ice of the Superior Lobe (Figure 4).

The Superior Lobe pushed up the dip-slope of the Sibley peninsula, flowed over the Giant and flowed up the Kaministiquia and Whitefish valleys, almost to present day Whitefish Lake. Locally, this sub-lobe of Superior ice is known as the Murillo Lobe, its deposits characterized by its content of red, but green mottled, Sibley mudstones.

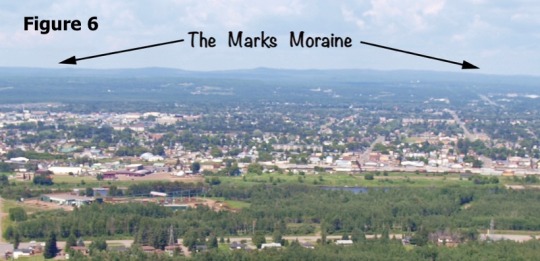

The Superior (Murillo) lobe appears to have halted and formed the Marks Moraine, which forms a prominent ridge on the skyline to the north of the City of Thunder Bay (Figure 6). Research has shown that in fact the Superior lobe merely plastered its deposits on the flanks of a much older morainic landform, originally formed in an earlier advance of the Rainy River lobe and preserved to the west as the Brule moraine. This is the phenomenon of "inheritance", a younger event modifying a landform of an earlier event, a not uncommon complication in the interpretation of post-glacial landscapes. Figure 6

Simultaneously (Figure 7), the Hudson Bay lobe pushed south-west, in contact with the Superior lobe to the east, halting along a south-east / north-west line running along the south edge of Dog Lake. The Dog Lake moraine melded with the Marks moraine at Lappe, the inter-lobate moraine, the Mackenzie moraine, being identifiable eastwards towards Dorion. Meltwater flowing west between the two lobes to the junction of the Marks and Dog Lake moraines, formed a large delta.

Deltas form where flowing water and debris meet the margin of a body of water, in this case, pro-glacial Lake Kaministiquia, which was temporarily trapped between the ice lobes and extended west into the Shebandowan area. In fact, the history of Lake Kaministiquia is more complex, there being interflows between it and the huge body of Glacial Lake Agassiz (named after the early explorer-naturalist!), which inundated much of what is now Manitoba, parts of Saskatchewan and N. Minnesota. Shorelines of former Lake Kaministiquia can be traced along the front faces of both the Dog Lake and Marks moraines. Figure 7

A very significant point to note is that while the Hudson Bay and Superior lobes advanced to cover and modify an older landscape and leave a fresh landscape upon their subsequent retreat, this older landscape remains untouched to the west of the Marks and Dog Lake moraines. Indeed, many layers of older landscapes remain, sediments exposed at the base of the steep river banks of the deeply incised Whitefish River valley belonging to much earlier phases of glacial history of which no surface evidence remains at all.

For example, the sediments and landforms of the Arrow Lake area (Figure 8), which include the Steep Rock moraine and the East Arrow delta, are those of earlier glacial events than the Marquette Readvance. Reverting to tundra conditions (characterized by lichens, "alpine" plants and stunted trees) during the Marquette Readvance, its former plant and animal assemblages, and possibly human occupants, retreated south-west to warmer climes, but evidence of their presence can remain, saved from the destruction by ice invasion as pollen in the soils, buried bone fragments and the debris of taconite tool making. Figure 8

A small glimpse of the wealth of detail of glacial and post glacial history is shown in Figure 9. As the Marquette ice began to melt back, the highest level of Lake Kaministiquia exceeded the height of the Marks moraine in places, lapping directly on ice. As the Superior (Murillo) lobe began to melt back, waters of Lake Kaministiquia broke over and through the Marks moraine and flooded the upper Whitefish valley, itself recently revealed from under the ice. The lake that formed, known locally as pro-glacial Lake Cedar Creek, after a stream that crosses its floor, was unable to flow east towards Thunder Bay, as waning ice still blocked the way. It found its exit west and south to the Pigeon River valley, also still blocked by ice to the east, so poured into a high level of Lake Superior through a broad channel found well above the present village of Hovland, MN. The route is verified by a thin layer of red clay found under more recent deposits and lying over the thick grey clays of earlier lacustrine and fluvioglacial events. Figure 9

This is but a glimpse of the detail of glacial history, which makes the Thunder Bay region one that is so varied and interesting. This amount of detail is, however, only known for the very latest events of glaciation. By inference, every glacial episode of the past had an equally complex and detailed history about which we know much less.

Present landscape is, as the palimpsest, a fascinating overlay of many phases of geomorphic processes and events. Though we tend to look at the landscape around us from the perspective of our own life-span and think of it as largely unchanging, it would serve us well to recognize that what we see today is as it is only because of a lengthy history of landscape change that we have inherited, and that change, though perhaps imperceptible to us, remains ongoing.

That at some point in the future, during a cold climatic period, ice will grind down from the north and cover almost all of Canada yet again, is certain, but, fortunately, it is not an imminent event.

senior70 September 2017

0 notes

Text

Scientists identify new flower from a forest that existed 100 million years ago

https://sciencespies.com/nature/scientists-identify-new-flower-from-a-forest-that-existed-100-million-years-ago/

Scientists identify new flower from a forest that existed 100 million years ago

Sometimes you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone. Valviloculus pleristaminis makes for a perfect example.

Scientists only recently identified this mysterious, extinct flower. It once bloomed in the Cretaceous period - a floral relic of a bygone age, preserved in time-stopping amber since some nameless day when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth.

“This isn’t quite a Christmas flower but it is a beauty, especially considering it was part of a forest that existed 100 million years ago,” says emeritus professor George Poinar Jr. from Oregon State University.

Poinar Jr. is something of an authority on the time-capsule-esque capabilities of amber.

The octogenarian entomologist is widely regarded as the scientist who popularised the phenomenon of prehistoric insects and nematodes being trapped in tree resin over geological timescales – ideas that took flight, literally much of the time, in the pop culture fantasy of Jurassic Park.

(George Poinar Jr./OSU)

This lifelong focus began decades ago, but Poinar Jr.’s academic output is still prodigious. In recent years he’s described ancient, engorged ticks, discovered new orders of insect life, traced the origins of malaria, and found his fair share of forgotten flowers.

V. pleristaminis, which represents both a new genus and species of flower, is among the latest in this ever-expanding bouquet.

“The male flower is tiny, about 2 millimetres across, but it has some 50 stamens arranged like a spiral, with anthers pointing toward the sky,” Poinar explains.

“Despite being so small, the detail still remaining is amazing. Our specimen was probably part of a cluster on the plant that contained many similar flowers, some possibly female.”

The specimen in question was obtained from amber mines in Myanmar, having been preserved in marine sedimentary deposits dating back to the mid-Cretaceous, approximately 99 million years ago.

(George Poinar Jr./OSU)

According to the researchers, V. pleristaminis, an example of an angiosperm (flowering plant), likely belongs to the order Laurales, particularly bearing some resemblance to the families Monimiaceae and Atherospermataceae.

But this strange, extinct flower doesn’t just offer clues about the history of floral evolution.

According to Poinar Jr., V. pleristaminis and other Burmese amber angiosperm fossils like it may also help to solve an outstanding mystery about the ancient supercontinent Gondwana from which these plants first arose.

Specifically, V. pleristaminis would have once blossomed on a chunk of Gondwana called the West Burma Block, which broke off from the rest of the supercontinent at some unknown point in history.

Quite when is a matter of some debate, with some geological hypotheses putting the date of separation as far back as 500 million years ago.

Research by Poinar Jr. however suggests that the West Burma Block could not have rafted from Gondwana to Asia before the early Cretaceous, given angiosperms only evolved and diversified about 100 million years ago.

The debate isn’t likely to be over any time soon, but V. pleristaminis and its amber-coated ilk provide a fresh line of thinking on the matter – a budding secret waiting to be told for almost 100 million years.

“The dating of [the West Burma Block] tectonic migration from Gondwana is not yet firmly established, but the 100 Ma age of the amber, with its included Southern Hemisphere-related plant and animal fossils, may factor into an eventual solution to this problem,” the researchers write.

The findings are reported in Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas.

#Nature

0 notes