#Sir Thomas Wriothesley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This book by Sir Thomas Wriothesley (21 December 1505 – 30 July 1550) shows what may be the first contemporary view of the State Opening of Parliament at Blackfriars in 1523, 500 years ago.

Henry VIII (28 June 1491 – 28 January 1547) is enthroned in the middle, with three earls in front of him bearing the Sword of State and the Cap of Maintenance.

#Henry VIII#House of Tudor#Tudor Dynasty#State Opening of Parliament#Sir Thomas Wriothesley#Sword of State#Cap of Maintenance#British Royal Family#saint of the day#book

1 note

·

View note

Text

preferred titles

daddy

Not that he wants to be a real dad or anything, but every time you're so obedient for him and reply with a submissive «Yes, daddy» it goes straight to his cock, intensifying the urge to make you bounce up and down on it, making you mewl for him like the needy mess you are. «That's it, pretty girl. Keep it up, I need to hear how much you're losing your mind for me.»

WRIOTHESLEY, Zhongli, Welt, Alhaitham, JING YUAN, Blade

master

He's used to being in a position of power over others, and it's no difference with you. Just be pretty for him, drool like a good pet and get on all fours, looking at him towering over you. He'll gently stroke your head, and if you're really good, you'll get to be used until you're oozing with his cum. «Aw, you're so adorable. Come over here. You've earned yourself a nice treat~»

AYATO, Baizhu, Albedo, Luocha, Dan Heng - Imbibitor Lunae, Kaeya

sir

One day you jokingly called him "Sir" and he discovered he likes it. It just makes him feel so powerful, to be able to make you feel so good, reducing you to a whimpering mess for his cock. So now whenever you want to trigger his dominant side, you know exactly what to say. «Feeling submissive, are we? Seems like you need to be put in your place.»

CHILDE, Gepard, Dan Heng, Cyno, Neuvillette

doesn't particularly care

He's not very fond of titles, he's okay with whatever you wanna call him: love, master, honey, whatever goes. All he cares about is making you feel good, wanted and most importantly LOVED. Most of the time you're also the one taking the lead, so he'll let you do whatever you want with him. «So good, love. Take your time, I want to feel you all over me, and I want to make you feel good.»

Kaveh, DILUC, Thoma, Tighnari, Xiao

──────────── ・ 。゚☆: *.☽ .* :☆゚. ────────────

NSFW, minors do not interact please

On a completely unrelated but also not so much note, I'm having a major Wriothesley brainrot/simp era, so expect something interesting very soon hehe

As always, a shorter post cause uni exists unfortunately

hope you enjoyed! <3 reblogs and comments are always appreciated *^*

ps: not proofread!

#genshin fanfic#genshin headcanons#genshin imagines#genshin impact#genshin x reader#genshin kaeya#genshin zhongli#genshin smut#genshin wanderer#genshin wriothesley#genshin writing#genshin kaveh#genshin diluc#genshin alhaitham#genshin albedo#genshin baizhu#genshin xiao#genshin x y/n#genshin x you#genshin childe#genshin tartagalia#hsr blade#hsr#hsr x reader#honkai star rail#hsr dan heng#imbibitor lunae#hsr luocha#hsr welt#hsr jing yuan

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Penace Summary: “If you think I am Walter, I will show you, Walter!” He cries, and Thomas freezes, his eyes are filled with fear. Rafe has never seen his master so afraid." / Moments before the final blow ends Thomas’ life, a herald arrives with a letter bearing the King’s seal, granting Thomas a reprieve. Unfortunately, Henry’s mercy has its limits. Thomas survives the pain of a botched execution, yet Rafe, Richard, and Gregory live through the consequences. And in attempting to fill the shoes of Thomas Cromwell, Rafe accepts it is a battle he may never win.

Let me take over. The thought aches in Rafe’s chest and he is wise to keep it there. It is rare for Gregory to mutter obscenities, but as his trembling hands make apprehensive strokes upon the mangled back of what one might assume to be the lifeless husk of Thomas Cromwell, Gregory lets out a string of swears. The elder Cromwell jerks away for the fifth time.

Rafe sighs.

“Gregory-”

“No.” He is my father, I need to do this, is what he means to say.

Rafe leans against the wall and in silence watches this tragic plot transpire.

It is Augst 2nd, 1540 and his master has woken from his coma following his poor timed reprieve.

On July 28th, the page boy, accompanied by a guard, makes it to the scaffold moments after the ax is lodged into his back a second time. The letter carries the king's seal, and the rushed yet careful words read as if they are spoken from the uncertain, yet repentant mouth of Thomas Wriothesley. The crowd disperses, muttering in anger and disappointment. Rafe remembers thinking how demonic they are, so frantic to see his master butchered.

Rafe ponders on the conversation between those fools and wonders what exactly was said by Risley to command the king’s regret. Rafe knows he should be thankful for their intervention, and if it stopped there, perhaps he would have been.

But the king is frivolous, and a reprieve does not mean forgiveness, even for Thomas Cromwell.

Rafe returns to Agust, and stares on in silence as his master sits hunched over in a chair, soiled shirt lifted, revealing the deep scars sown into his back. Gregory is behind him, as dutiful a son as he attempts to be, dabbing a sterile cloth in a bucket of a warm, alcoholic water mixture and then with great care, tends to Thomas’ wounds.

Through the pain and the weeping, and the drenched gray and black curls that haphazardly fall over his face, dark pupils catch Gregory in their path.

Once again, he flinches and jerks away from his son.

“Father.” His voice trembles. In sadness, in anger? Rafe supposes it’s both. He does not blame Gregory for the cesspool of emotions swelling within the pits of his chest. He’s tired, his body shakes, his steps are heavy, and all his money and efforts have been spent on this moment. Bargains, pleas to the king, his estates and titles given up to please the burned ego of His Majesty and the new queen; Gregory’s own wife having had left him in the process.

For Thomas, Gregory has become a pauper.

“I don’t want you, you are no son of mine,” Thomas mutters in the silence; it is enough for Gregory to stop. “I want Rafe.”

Thomas, cannot stand his son’s touch.

Gregory pauses, cloth still hovering over Thomas’ back. His eyes glisten, and he does not cry only silently motions to Rafe, who comes and takes over. Gregory leaves and Thomas does not say a word.

“It’s alright sir, I’ve got you”

The door closes and Gregory is gone.

For Rafe’s part, he is no stranger to this. He stands behind Thomas and picks up where his wayward brother left off. The solution from the cold rag falls down his wrist, and gently he scours the wounds upon his master’s back. Thomas does not flinch or push him away. It is as if his body eases, and the threat of an uncomfortable force is no longer upon him.

Still, Thomas shakes. The frigid air stings his wounds, and Rafe quickens his deed. Within an hour, the bandages are changed and he helps Thomas back to his bed. It does not take him long to fall asleep, and his body trembles in pain with every breath that escapes his lips. Rafe fears it will be his last.

Now, however, he must tend to the younger Cromwell.

__

Gregory has exiled himself to a storage room, and he stands by the window, leaning over with his hands resting upon the ledge.

He is quiet, though his shoulders shake and his head hangs low. Rafe can tell that he is weeping.

“Gregory.” Rafe disturbs the silent isolation he supposes Gregory preferred, but the young Cromwell turns in his direction, wiping his eyes. There is a small movement of what Rafe figures is a letter, stuffed into Gregory’s jacket.

“Rafe, how is he?”

Gregory arranges his face in a way dissimilar to his father's. He does not hide emotion behind a stone-like facade. Rather he smiles. Eyes puffy beneath, breath still shaky, Gregory erects a smile so unsettling, Rafe does not know what to say.

So he speaks only the truth. “He is fine. May I come?”

Gregory nods as if speaking now causes too much pain. So Rafe saves him the trouble and pulls him into a hug as if he has embraced one of his own children. Though Gregory, now twenty is a grown man, Rafe can only see the child he helped raise before him. The boy trembles in his arms and when he is sure they are alone, he allows himself to cry.

He does not make legible words, but Rafe gathers ‘Why doesn’t he want me?’ ‘Why do I frighten him?’, and his eyes, pained yet beautiful scream ‘I gave him everything, and I lost everything, and I am still not enough’.

“Shh.” Rafe whispers into silence, his embrace upon the younger Cromwell tightening. He feels his strength beneath his shirt, the muscles that have marked his transition from boy to man, and yet all Rafe holds is a child. The child who ran to him at night during storms, the child whom he taught to read when his father and mother were away, the child that in some instances did not know whether to call him ‘Master Saddler’ or ‘Brother’.

Either suffices, but Rafe feels a different connection now. A father of his own making, he realizes that Gregory has lost his.

He holds him tighter and gently places a kiss on Gregory’s forehead as if he is a parent, chasing away the nightmares of a shaken toddler.

“It will pass,” Rafe says softly, cupping Gregory’s face in his hands. He sniffles and gasps, and tears pour down his cheeks, Rafe speaks. “My Master…your father he is…” He is not there, and his mind has perhaps gone to heaven. We do not know the man who lies in the bed in pain, who cries himself to sleep at night, who calls you Walter, who refers to Richard and me as his sons, who asks why the King was so cruel to him. But we can’t hold it against him, he wants to tell Gregory. We cannot hold him accountable for what the King did to him.

But Rafe knows that is true only for this moment. For Gregory’s life, the struggle for his father’s affection has been constant.

Rafe would never presume to take the place of his master, but for now, perhaps, Gregory needs a tender father.

He still holds Gregory’s pale, child-like face in his hands and wipes the tears with his thumbs. He starts to see the timid boy once again, even beneath the facial hair and flushed cheeks.

“There you are, Gregory.” He smiles. “Helen may have prepared dinner, if you go down, I will meet you there.” He holds Gregory until the younger man nods and musters some form of smile. “And now no more. Hold your head high. It will be well.”

He releases him and prays that things will go well.

–

Richard comes the next day and as Rafe fears, things do not go well.

It is not uncommon knowledge, that since the ill-timed reprieve and even before that, when first Thomas was arrested, Richard harbored some sort of resentment toward his cousin.

“Why did he not come to visit his father, my uncle in the Tower?” Richard had once asked Rafe.

“Thomas told him not to. And before you say anything else, he also instructed Gregory and Bess to write that letter against him.” Rafe had responded.

“My uncle would not have wanted you to go, but still you went.”

You didn’t visit him in the tower either, Rafe had wanted to say, but he knew that would be fruitless. It was evident that if Richard stepped within a foot of the tower, he would’ve turned to violence, and would have had a place right next to his uncle.

The truth, however, is that on that day, Gregory did not want to come. Rafe had repeatedly asked Gregory to join him in the tower, and Gregory refused. In fact, to a random wanderer, Gregory’s lack of reaction to hearing of his father’s execution would cause concern, or even a seed of doubt in the fact that Gregory was in fact, the son of Thomas Cromwell. He simply did not care, nor show any emotion.

While it pained Rafe, Gregory’s reaction, or rather a lack of one, made sense to him.

It is how the young Cromwell coped. How was one supposed to react to hearing of the oncoming execution of their father, wherein, the lack of a concrete relationship clouded any form of empathetic emotion? Thomas was Gregory’s father in name; he knew he had the man’s curly hair, dark eyes, and pale skin, he knew those around him would call him ‘Thomas’ if he passed them quickly, only to correct themselves. Most of the time it does not impact him. (Though when Call Me Risley, well rather Wriothesley, had made that mistake once, Gregory lashed out, and Rafe still does not know why that angered Gregory so much).

Back then Gregory prepared to mourn both his father and the unattainable relationship he yearned for with his father. Still, he refused to see him and he came to regret it.

Now, since the reprieve, he makes up for it any way he can. Except, it hasn’t been easy. Thomas does not recognize him, and if he does, he hates him. He doesn’t call Gregory ‘son’, or even by his name, he calls him Walter. When Gregory tries to change his bandages and clean the wounds the ax men left on his back, he pushes away and calls for Rafe and Richard instead. Richard finds it hilarious, but it breaks Rafe to see Gregory so isolated.

Especially given how much Gregory has sacrificed to ensure his father’s survival. It was, in a surprising turn of events both Rafe and Wriothesely (filled with guilt and remorse) who moved the king to a reprieve, but Gregory as his son, had to shoulder Henry’s anger and ensure that his father never ended up on the scaffold again.

Without a title and assets, Gregory had little to appease the financial appetite of Henry and Katherine Howard, but what he had, he gave it. That left him with nothing. Bess left him (for reasons not exactly tied to his drop in station - and Gregory did not begrudge her), and his home was taken from him, as was his title. The remaining fines to keep Thomas alive were paid by Wriothesley, Richard, and Rafe. Subsequently, Rafe more than offered to let Gregory and Thomas stay with him.

That was a few weeks ago, and things had been going as decent as possible. Gregory can somewhat accept his father’s poor actions toward him; he understands how the ax may have ruined his mind.

Richard’s taunting on the other hand...he does not take that well.

Read the rest on AO3

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

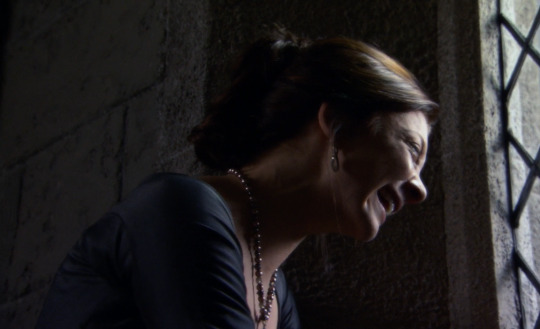

May 17, 1536 - The Executions of George Boleyn, Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, William Brereton, and Mark Smeaton

"Masters all, I am come hither not to preach and make a sermon, but to die. As the law hath found me, and to the law I submit me, desiring you all, and especially you, my masters of the court, that you will trust in God especially, and not in the vanities of the world. For if I had so done, I think I had been alive as ye be now. Also, I desire you to help … the setting forth of the true word of God. And whereas I am slandered by it, I have been diligent to read it and set it forth truly. But if I had been as diligent to observe it, and done and lived thereafter, as I was to read it and set it forth, I [would not have] come here. Wherefore I beseech you all to be workers and live thereafter, and not to read it and live not thereafter. As for mine offenses, it cannot prevail you to hear them that I die here for. But I beseech God that I may be an example to you all, and that all you may beware by me, and heartily I require you all to pray for me, and to forgive me if I have ever offended you. And I forgive you all. And God save the King." - George Boleyn's execution speech in Wriothesley's Chronicle

"Some say, 'Rochford, haddest thou been not so proud,

For thy great wit each man would thee bemoan,

Since as it is so, many cry aloud

It is great loss that thou art dead and gone." - Thomas Wyatt (?), In mourning since daily wise I increase

"These bloody days have broken my heart.

My lust, my youth did them depart,

And blind desire of estate.

Who hastes to climb, seeks to revert.

Of truth, circa regna tonat [about the throne, thunder rolls]." - Thomas Wyatt, Who list his wealth and ease retain

"Mr. Norris ... said almost nothing at all." - George Constantine

"I had thought to have lived in abomination yet these twenty or thirty years, and then to have made amends. I thought little it would have come to this." - Francis Weston's last words, as reported by Constantine

"I have deserved to die if it were a thousand deaths. But the cause wherefore I die, judge not. But if you judge, judge the best." - William Brereton's last words, as reported by Constantine

"Masters, I pray you all, pray for me, for I have deserved the death." - Mark Smeaton's last words, as reported by Constantine

Also on this day, Anne's marriage to Henry was annulled by Archbishop Cranmer, either on the grounds of a precontract with Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, or Henry's affair with her sister Mary before he met Anne.

#tw blood#tw torture#tudorerasource#perioddramaedit#dailytudors#anne boleyn#the tudors#natalie dormer#the six wives of henry viii#george boleyn#henry norris#william brereton#francis weston#mark smeaton#dorothy tutin#anne boleyn 2021#jodie turner smith#sorry this is a long post#but idk how to make it any shorter#I wanted to make a post which properly commemorated these 5 brave men#and let them speak in their own words#I've purposefully not used The Tudors for George Boleyn's execution bc#they rly cut his speech down and made it happen in front of a jeering mob which clearly didn't happen#since multiple people were able to transcribe such a long speech#so I used (ofc) TSWOH8 1970#RIP to these kings#:(

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

⋆₊˚⊹♡ GENSHIN IMPACT M.LIST

© all work & content posted belongs to recareels 2024. do not under any circumstances modify or repost. do not claim as your own. do not recommend my work on tiktok/wattpad. do not read my work as asmr.

⋅˚₊‧ 𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬 ‧₊˚ ⋅

˚。⋆♡ 𝐚𝐲𝐚𝐭𝐨 ♡⋆。˚

⋆ only you

yakuza boss!ayato x reader ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, somnophilia, dubcon, minimal prep, rough sex, size kink/size difference, implicit toxic relationship, daddy kink, yakuza boss!ayato, dacryphilia, praise ⋆ words: 2.7k

˚。⋆♡ 𝐚𝐲𝐚𝐭𝐨 + 𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐦𝐚 ♡⋆。˚

⋆ feels like forever, even if forever’s tonight

yakuza boss!ayato x reader x thoma ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, dubcon, manipulation/coercion, daddy kink, toxic relationships, size kink/size difference, belly bulge, cuckolding kinda (ayato watches thoma fuck his girlfriend), praise, reader is quite flexible, a hint of dumbification/degradation, rough sex, overstimulation + mentioned orgasm denial as punishment, dacryphilia, power play/power dynamics, thoma is a sub-leaning switch in this, interchangeable use of the words my lord/master ⋆ words: 5.7k

˚。⋆♡ 𝐚𝐥𝐡𝐚𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐦 ♡⋆。˚

⋆ i’m gonna sleep cause you live in my daydreams

professor!alhaitham x reader ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, slight dubcon, minimal prep, sex gets rougher near the end, size kink/size difference, reader is a Brat with a capital B, daddy kink, one instance of name calling (slut), alhaitham is very clearly a professor in this although it isn’t explicitly mentioned, cock sucking, cock riding, a tiny bit of crying, dom/sub power dynamics, praise, reader is female, hints of a toxic relationship ⋆ words: 4.5k

⋆ cut me rails of that fresh cherry pie

teaching assistant!alhaitham x university student reader ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, dubcon, rough sex, extremely bratty reader, minimal prep, semi-public sex, use of the word Sir, painful sex, one (1) instance of spanking, one (1) slap to the face, hints of implied trauma, biting, marking, blood, alhaitham is strong enough to lift reader up and fuck her against the shelves, praise, toxic relationship, student professor (TA) relationship (power imbalance), dom/sub power dynamics, undefined age gap between consenting adults, big size difference between alhaitham and reader, size kink, sex as punishment, sex as an emotional release, choking, reader is quite flexible, belly bulge, snowballing ⋆ words: 10.9k

⋆ something ‘bout you

professor!alhaitham x phd grad student reader ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, fem reader, praise, professor/graduate student relationship, sir kink, face fucking, cum swallowing, a teeny tiny bit of manipulation, lying via omission, reader is a film and linguistics student, a bit of academic jargon but nothing crazy or crucial, dom/sub dynamics ⋆ words: 8k

⋅˚₊‧ 𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐬 + 𝐬𝐤𝐞𝐭𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐬 ‧₊˚ ⋅

˚。⋆♡ 𝐚𝐥𝐡𝐚𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐦 ♡⋆。˚

⋆ alhaitham as your TA (written on my main blog @inkykeiji)

drabble ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, student-prof (TA) relationship, implied age gap ⋆ words: 192

⋆ alhaitham making me yummy cummy pancakes!! (๑ᵔ⤙ᵔ๑)

drabble ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, cum eating; literally eating cum on pancakes as if it were syrup ⋆ words: 288

⋆ i want TA!alhaitham to be mean to me :(

ink splattered ask ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, student-prof (TA) relationship, haitham is a meanie!, hint of dumbification ⋆ words: 194

˚。⋆♡ 𝐰𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐥𝐞𝐲 ♡⋆。˚

⋆ wriothesley + putting you back in your place (before you can even fully slip out of it!)

wriothesley x reader ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, reader is a Brat, daddy kink, pet names, fem reader, dry humping, talks of spanking, use of the term sir ⋆ words: 1.6k

˚。⋆♡ 𝐦𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐢𝐩𝐥𝐞 ♡⋆。˚

⋆ favourite positions

ajax, ayato, thoma + alhaitham ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, rough sex, reader is female and flexible, dom/sub power dynamics, marking in ajax’s (implied blood) and alhaitham’s, mentioned dacryphilia in thoma’s, very slight dubcon in alhaitham’s ⋆ words: 1.5k

⋆ a reader who likes to bite

ajax, ayato, thoma + alhaitham ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, biting, bruising, blood, minimal prep, daddy kink, sadism, dom/sub power/relationship dynamics, a mention of dacryphilia in ajax’s, reader is female ⋆ words: 1.5k

⋆ favourite roleplay scenarios

ajax, ayato, thoma, alhaitham ⋆ warnings: 18+ minors do not interact, consensual noncon + stockholm syndrome + kidnapping in ajax’s, mentions of spanking, slapping, and bondage in alhaitham’s, blood, hint of yandere in thoma’s, coercion in ayato’s, power imbalances that are taken advantage of/clear power dynamics (dom/sub) ⋆ words: 1.5k

#inky.masterlist#yay!!!!!!#genshin smut#genshin x reader#genshin impact smut#genshin impact x reader

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Request Rules and Characters

Request Rules

In a request, I will write for a maximum of five (5) characters per request, however I am extremely willing to do another part with other characters!

I write for gn!/Masc!/trans! readers! Pronouns will be he/him and/or they/them.

I am VERY willing to write poly ships! almost any poly ship I will at least attempt unless its very bad or the characters like never interact?? I am poly, so I love to write for poly couples

I *do* write nsfw, for of aged characters! (There are a few exceptions; Mualani is an of aged characters that I will not write nsfw for)

Pedophilia, incest, non-con, or similar themes are NOT allowed to any extent.

I won't write daddy/mommy kinks. If those are requested, the word will be substituted for (ex. instead of using daddy, then i would use sir or master or something to that affect.)

i won't write any "unethical" or "disturbing" kinks. Word used loosely because I mean, you do you, as long as its consensual idc what you do, but I don't feel comfy writing for certain things. I recommend just asking first if you are unsure.

Not a rule necessarily, but please be patient with me! I'm in my freshman year of college and I am living on campus (which has me very stressed out and depressed). I have school work to do and I am also working on writing a book! So I won't be on constantly, however I do write a LOT so don't miss out :P

Characters I will write for! (updated as the game continues)

Aether

Lumine

Venti

Kaeya

Diluc

Jean

Sucrose

Albedo

Bennett

Razor

Xiao

Zhongli

Gaming

Baizhu

Hu Tao

Tartaglia/Childe

Ningguang

Beidou

Xingqui

Chongyun

Xiangling

Heizou

Kirara

Kuki

Ayato Kamisato

Ayaka Kamisato

Yae Miko

Arataki Itto

Gorou

Thoma

Sanganomiya Kokomi

Raiden Shogun/Ei

Kazuha

Kaveh

Alhaitham

Dehya

Wanderer/Scaramouche

Cyno

Tighnari

Lynette

Lyney

Freminet

Neuvillette

Wriothesley

Furina

Emilie

Mualani

Kinich

Mavuika

Xilonen

Pantalone

0 notes

Text

Fandoms/Characters I write for

Just so you know what characters I have a bias for, I'm bolding their name so that just means you have a higher chance of me accepting your request lmao. im rigging it Hazbin Hotel Adam (SFW or N$FW) Alastor (SFW only) Angel Dust (SFW or N$FW) Charlie Morningstar (SFW or N$FW) Vaggie (SFW or N$FW) Husk (SFW or N$FW) Niffty (SFW for now, I might reconsider because she's technically an adult but idk it feels a bit icky) Sir Pentious (SFW or N$FW) Cherri Bomb (SFW or N$FW) Lucifer Morningstar (SFW or N$FW) Lute (SFW or N$FW) Sera (SFW or N$FW) Emily (SFW or N$FW) Rosie (SFW only FOR NOW I'll probably change it once I know her character better yk) Valentino (SFW or N$FW) Vox (SFW or N$FW) Velvette (SFW or N$FW) Carmilla Carmine (SFW or N$FW) Helluva Boss Blitzo (SFW or N$FW) Moxxie (SFW only for now) Millie (SFW or N$FW) Loona (SFW or N$FW) Stolas (SFW or N$FW) Octavia (SFW only) Stella (SFW only and only if she's in character and repeatedly calling everyone a bitch) Fizzarolli (SFW or N$FW) Verosika Mayday (SFW or N$FW) Striker (SFW or N$FW) Chaz (SFW or N$FW) Genshin Impact Arlecchino (SFW or N$FW) Albedo (SFW or N$FW) Alhaitham (SFW or N$FW) Ayaka (SFW or N$FW) Ayato (SFW or N$FW) Baizhu (SFW or N$FW but for N$FW I really want to write him in character and constantly coughing his lungs out) Childe (SFW or N$FW) Chiori (SFW or N$FW) Cyno (SFW or N$FW) Dehya (SFW or N$FW) Diluc (SFW or N$FW) Eula (SFW or N$FW) Furina (SFW only for now) Ganyu (SFW or N$FW) Hu Tao (SFW only for now) Itto (SFW or N$FW) Jean (SFW or N$FW) Kazuha (SFW or N$FW but I'll give you bonus points if I can slander him because I fucking hate him I'm not sorry this dude fills me with rage) Keqing (SFW or N$FW) Klee (SFW only) Kokomi (SFW only for now) Lyney (SFW or N$FW) Mona (SFW only for now) Nahida (SFW only) Navia (SFW or N$FW) Neuvillette (SFW only for now) Nilou (SFW or N$FW) Qiqi (SFW only) Raiden Shogun (SFW or N$FW) Raiden Ei (SFW or N$FW) Shenhe (SFW or N$FW) Tighnari (SFW or N$FW) Traveler (SFW only for now) Venti (SFW or N$FW) Wanderer (SFW or N$FW) Wriothesley (SFW or N$FW) Xianyun (SFW only for now) Xiao (SFW or N$FW) Yae Miko (SFW or N$FW) Yelan (SFW or N$FW) Yoimiya (SFW only for now) Zhongli (SFW or N$FW) Amber (SFW only idk abt the age) Barbara (SFW only) Beidou (SFW or N$FW) Bennett (SFW only) Candace (SFW only for now) Charlotte (SFW cuz idk) Chevruese (SFW or N$FW) Chongyun (SFW only) Collei (SFW only) Diona (SFW only) Dori (SFW only) Faruzan (SFW only for now) Fischl (SFW only) Freminet (SFW only) Gaming (SFW only for now) Gorou (SFW or N$FW) Heizou (SFW or N$FW) Kaeya (SFW or N$FW) Kaveh (SFW or N$FW) Kirara (SFW only) Kuki (SFW or N$FW) Layla (SFW only) Lisa (SFW or N$FW) Lynette (SFW only) Mika (only if I'm laughing at his nerd ahh) Ningguang (SFW or N$FW) Noelle (SFW only idk) Razor (SFW only) Rosaria (SFW or N$FW) Sara (SFW or N$FW) Sayu (SFW only) Sucrose (SFW only) Thoma (SFW or N$FW) Xiangling (SFW only) Xingqiu (SFW only) Xinyan (SFW or N$FW) Yanfei (SFW or N$FW) Yaoyao (SFW only) Yun Jin (SFW only) CLICK HERE FOR PART TWO

0 notes

Text

Women of the Reformation: Anne Askew (1521-1546)

Most Christians have heard the names of John Calvin, Martin Luther, John Knox, and other giants of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. But there are many, many other men and women who worked to advance the cause of the Reformation!

Anne Askew (or Ayscough) was born in 1521 in Lincolnshire, England, to William Askew, a wealthy landowner. Anne was a woman of courage and strong beliefs. She was tortured, in the Tower of London and burned alive as a Protestant heretic for preaching the Gospel in London and handing out Protestant leaflets.

William Askew had arranged that his eldest daughter, Martha, be married to Thomas Kyme. When Anne was 15 years old, Martha died. Her father decided Anne would take Martha's place in the marriage to Thomas to save money. She was a woman of very strong and sincere beliefs. In her early life she showed an interest and ability for theological studies. Anne was converted to Protestantism when the 'new bible' emerged from the continent. After much study and reading of the Holy Scriptures she adopted the principles of the reformers and became a dedicated believer, a devout Protestant, studying the Bible and memorizing verses, and remained true to her belief for the entirety of her life. Her reading convinced her of the falsity of the doctrine of transubstantiation, and her pronouncements created some controversy in Lincoln.

Her husband was a Catholic, and the resultant marriage was brutal. Askew had two children with Kyme before he threw her out for being Protestant. It is alleged that Askew was seeking to divorce Kyme, so this did not upset her. Upon being thrown out, Askew moved to London. Here she met other Protestants, including the Anabaptist Joan Bocher, and they studied the Bible together. Askew stuck to her maiden name, rather than her husband's name. While in London, she became a "gospeler --someone who knew large parts of the bible by heart and could preach about them. The ban on Bible reading had intensified the hunger for it, and those who knew the Bible well became lay preachers. As a woman of high social status, this was bound to attract the attention of the authorities.

In March 1545, her husband Thomas Kyme had Askew arrested. She was brought back to Lincolnshire, where he demanded that she stay. The order was short lived; she escaped and returned to London to continue preaching. In early 1546 she was arrested again, but released. In May 1546 she was arrested again, and tortured in the Tower of London. She was then cross examined by the chancellor of the Bishop of London, Edmund Bonner. He ordered that she be imprisoned for 12 days. During this time she refused to make any sort of confession.

She was ordered to name like-minded women, but refused. She was then subject to a two-day-long period of cross examination led by Chancellor Sir Thomas Wriothesley, Stephen Gardiner, The Bishop of Winchester (John Dudley), and Sir William Paget (the king's principal secretary). They threatened her with execution, but she still refused to confess or to name fellow Protestants. She was then ordered to be tortured. Her torturers did so, probably motivated by the desire for Askew to admit that Queen Catherine was also a practicing Protestant.

According to her own account, and that of gaolers within the Tower, she was tortured only once. She was taken from her cell, at about ten o'clock in the morning, to the lower room of the White Tower. She was shown the rack and asked if she would name those who believed as she did. Askew declined to name anyone at all, so she was asked to remove all her clothing except her shift. Askew then climbed onto the rack, and her wrists and ankles were fastened. Again, she was asked for names, but she would say nothing. What was exceptional about Anne was that despite being arrested, interrogated, and put on the rack (a device so fearful that most victims confessed whatever was required of them), she refused to give names or implicate others, including women at court close to Queen Catherine Parr. She also refused to be silent, arguing forcefully and confounding her accusers with her knowledge and learning. Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, was so impressed with the way Anne behaved that he refused to torture her. King Henry VIII's Lord Chancellor Wriothesley and Sir Richard Rich had to take over. Other accounts say it was Anne's obstinacy that so enraged Wriothesley that he turned the rack himself.

In her own words, Anne said, "Then they did put me on the rack because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen to be of my opinion; and thereon they kept me a long time and because I lay still and did not cry, my Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands till I was nigh dead."

The wheel of the rack was turned, pulling Askew along the device and lifting her so that she was held taut about 5 inches above its bed and slowly stretched. In her own account written from prison, Askew said she fainted from pain, and was lowered and revived. This procedure was repeated twice. They turned the handles so hard that Anne was drawn apart, her shoulders and hips were pulled from their sockets and her elbows and knees were dislocated. Askew's cries could be heard in the garden next to the White Tower where the Lieutenant's wife and daughter were walking. Askew gave no names, and her ordeal ended when the Lieutenant ordered her to be returned to her cell.

On 18 June 1546, she was convicted of heresy, and was condemned to be burned at the stake. Because of the torture she had endured, she had to be carried to the stake on a chair wearing just her shift as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. She was dragged from the chair to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck.

Prior to their death, the prisoners were offered one last chance at pardon. Bishop Shaxton mounted the pulpit and began to preach to them. His words were in vain, however. Askew listened attentively throughout his discourse. When he spoke anything she considered to be the truth, she audibly expressed agreement; but when he said anything contrary to what she believed Scripture stated, she exclaimed: "There he misseth, and speaketh without the book."

Her body was covered in gunpowder before her execution. This was seen as a kindness. Friends often placed gunpowder on the condemned, as it hastened what could be a very slow and painful death. But because she had obstinately defied authority, she was burned alive slowly rather than being strangled first or burned quickly.

So many people turned out for the execution that there was hardly enough room to carry it out. The crowd had to be pushed back. Those who saw her execution were impressed by her bravery, and reported that she did not scream until the flames reached her chest. The execution lasted about an hour, and she was unconscious and probably dead after fifteen minutes or so.

At her execution there was a sudden thunderstorm and a loud clap of thunder. Bale wrote that “Credibly I am informed by various Dutch merchants who were present there, that in the time of their sufferings, the sky, abhorring so wicked an act, suddenly altered colour, and the clouds from above gave a thunder clap, not unlike the one written in Psalm 76. The elements declared the high displeasure of God for so tyrannous a murder of innocents.

Anne Askew was burned at the stake at Smithfield, London, at the age of 26, on 16 July 1546. She burned to death, along with three other Protestants, John Lascelles, Nicholas Belenian and John Adams. She was the last martyr in the reign of Henry VIII.

Her crime? Knowing the Bible, preaching the true gospel and the falsity of Catholic doctrine, especially the doctrine of transubstantiation, and handing out Protestant leaflets.

Of all the stupid and suicidal mistakes that the Romish Church ever made, none was greater than the mistake of burning the Reformers. It cemented the work of the reformation and made Englishman Protestants by the thousands. When plain Englishman saw the church of Rome so cruelly wicked and Protestants so brave, they ceased to doubt on which side was the truth. May the memory of our martyred Reformers never be forgotten until the Lord comes!"

#Women of the Reformation: Anne Askew (1521-1546)#biography#Protestant#martyrs#crimes of the Roman Catholic Church#Anne Askew

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Parr was born around 1514 to Sir Thomas Parr and his wife, Maud Green. She was the youngest child of Thomas and Maud.

Sir Thomas died of the sweating sickness in 1517, leaving Maud, only twenty-two years old, to fend for her three very young children. Maud decided to not remarry, so that she might retain her wealth left to her from her husband, and decided to devote her attention to her children. Maud Parr was a lady in waiting to Catalina of Aragon.

As the Parr children came of age, their mother made designs for them to marry well. William was the first, when he married Anne Bourchier in 1526. Anne was placed in Catalina of Aragon's household two years later as a lady-in-waiting. Anne's sister, Catherine, was married off to Baron Borough in 1529. That same year, their mother, Maud, died, and Anne became a ward of King Henry VIII.

After Henry's divorce from Catalina of Aragon and subsequent marriage to Anne Boleyn, the teenage Anne Parr remained in the King's household as a lady-in-waiting to the new Queen. Anne Parr remained as a lady-in-waiting to each of Henry VIII's wives, and is one of the few people to have been lady-in-waiting to all six.

By 1537, as 'Mrs Parr', Anne had become one of Jane Seymour's maidens. She was barely sixteen, sweet and, thanks to her mother's foresight, eminently marriageable. As we have seen, her father had left her a substantial marriage portion, to which her mother's will added 400 marks in plate and a third share of her jewels. The whole fortune, Lady Parr had directed, was to be securely chested up 'in coffers locked with divers locks, whereof every one of them my executors and my ... daughter Anne to have every of them a key'. 'And there', Lady Parr's will continued, 'it to remain till it ought to be delivered unto her' on her marriage.As Lady Herbert, she was keeper of the Queen’s jewels to Catherine Howard, although she left court briefly to give birth to her first child, Henry, ABT 1540. She was back at court in time to attend the disgraced Queen at Syon House and in the Tower. When her sister Catherine became Henry VIII’s sixth Queen in 1543, Anne returned to court. John Dudley, who was now Lord Admiral and Viscount Lisle, wrote to William Parr from Greenwich on 20 Jun: 'but that my Lady Latimer, your sister, and Mrs Herbert be both here at Court with my Lady Mary's Grace and my Lady Elizabeth'.Anne, along with Catherine Willoughby and Anne Stanhope were part of the Queen Catherine's inner circle, and they were all Protestants. After Anne Askew, a Protestant was arrested, those who opposed Queen Catherine tried to gain a confession from Askew that the Queen, her sister, and the other women were Protestants. Askew refused to name any names, even under the pain of torture; still, warrants for the arrest of the Parr sisters and the other two were sent out. Gardiner and his new ally Wriothesley got Henry's agreement to a coup against the Queen. Her leading women, Ladies Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhitt, would be arrested; their illegal books seized as evidence; and the Queen herself sent 'by barge' to the Tower. The Queen, however, warned of what awaited him, apologized to Henry. Quickly reconciled, and when Wriothesley arrived with forty yeomen of the guard at his back and an arrest warrant from the Queen in her pocket, was greeted with a barrage of real abuse and sent packing with his tail between his legs.Anne and her husband used Baynard’s Castle as their London residence. For the birth of her second son Edward, Anne's sister loaned her the manor of Hanworth in Middlesex for her lying in. After the birth, Anne visited Lady Hertford, who had also just given birth, at Syon House near Richmond. In Aug, the Queen sent a barge to bring Anne by river from Syon to Westminster. A girl was the hird child of William and Anne, named Anne. After Henry VIII's death, when the Queen dowager's household was at Chelsea, both Anne and her son Edward were part of the household there. At the time of her death, Anne Parr was one of Princess Mary’s ladies.

In 1551, William Herbert was created Earl of Pembroke. Anne died quite unexpectedly at Baynard's Castle and was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral next to the tomb of John of Gaunt. Her memorial there reads: "a most faithful wife, a woman of the greatest piety and discretion".

Source: http://www.tudorplace.com.ar/Bios/AnneParr.htm

#perioddramaedit#the tudors#history#edit#history edit#henry viii#anne boleyn#tudorsedit#anne parr#anne herbert#anne herbert nee parr#catherine parr#katherine parr#vittoria puccini#tudor dynasty#maud parr#tudor era#tudorsdaily#historical aesthetic#women in history#catherine willoughby#anne askew#anne stanhope#catherine of aragon#historical figures#16th century#elizabeth i

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henry VII on his deathbed (British Library, Add. MS 45131, f. 54)

Though he may not have been present, the Garter King of Arms, Sir Thomas Wriothesley (d. 1534), wrote a detailed account of the proceedings surrounding the death of Henry VII and drew this picture of the King on his deathbed.

The dying King is in his Privy Chamber, surrounded by his most intimate courtiers and household (clockwise round the bed): Richard Fox, Bishop of Winchester (d. 1528); George, Lord Hastings (d. 1544); Richard Weston, Esquire of the Body (a household officer in constant attendance on the king) and Groom of the Privy Chamber (d. 1541); Richard Clement, Groom of the Privy Chamber (d. 1538); Matthew Baker (or Basquer), Esquire of the Body (d. 1513); John Sharpe and William Tyler, Gentlemen Ushers; Hugh Denys, Esquire of the Body; and William Fitzwilliam, Gentleman Usher (d. 1542), who holds a staff of office and closes the King’s eyes.

Also present are two tonsured clerics and three physicians holding urine bottles. It was possible to keep Henry’s death a secret, as he was out of the public eye, and it was Weston who is described by Wriothesley as keeping up the pretence that the old King was still alive until 23 April.

123 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary Wriothesley, née Browne, Countess of Southampton (22 July 1552 - October/November 1607)

#mary browne#mary wriothesley#countess of southampton#daughter of anthony browne 1st viscount montagu#married henry wriothesley 2nd earl of southampton#then sir thomas heneage#then sir william hervey#history#women in history#art

1 note

·

View note

Text

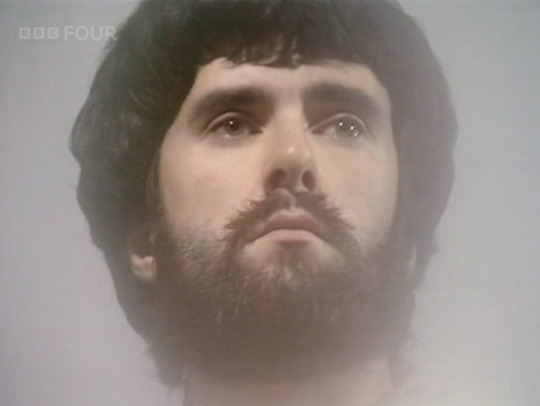

Young Bess Tudor - The Lion's Cub

"If she be no worse educated than she now appeareth to me, she will prove no less honour to womanhood than shall beseem her father's daughter." -Sir Thomas Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, c. 1539.

This echoes what Glenda Jackson said to her subjects in the BBC miniseries "Elizabeth R" (1971), after he gives her the royal ring which informs her she's the new queen, "I may not be a lion but I'm a lion's cub and I have a lion's heart."

Elizabeth's precocious nature also caught the attention of noted Protestant tutor and Humanist, Roger Ascham, who advised her caretakers not to push their charge beyond her natural limits.

"If you pour much drink at once into a goblet, the most part will dash out and run over... If you pour it softly, you may fill it even to the top, and so her Grace, I doubt not, by little and little may be increased by learning, that at length greater cannot be required."

This kind of cautionary approach would be on full display by the last Tudor monarch throughout her reign. unfortunately, this quasi-Socratic view also made her insecure. While she possessed the good wisdom not to dismiss her councilors advice right away, she did take considerable time to reach a decision.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌷REFORMATION MONTH 🌷

Most Christians have heard the names of John Calvin, Martin Luther, John Knox, and other giants of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. But there are many, many other men and women who worked to advance the cause of the Reformation!

Women also played an important role, either in disseminating the ideas of the Reformation, or using their political power to protect the preachers and teachers of these ideas, and, yes, some were burned at the stake.

Here is one of these women:

Anne Askew 1521-1546

Anne Askew (or Ayscough) was born in 1521 in Lincolnshire, England, to William Askew, a wealthy landowner. Anne was a woman of courage and strong beliefs. She was tortured, in the Tower of London and burned alive as a Protestant heretic for preaching the Gospel in London and handing out Protestant leaflets.

William Askew had arranged that his eldest daughter, Martha, be married to Thomas Kyme. When Anne was 15 years old, Martha died. Her father decided Anne would take Martha's place in the marriage to Thomas to save money.

She was a woman of very strong and sincere beliefs. In her early life she showed an interest and ability for theological studies. Anne was converted to Protestantism when the 'new bible' emerged from the continent. After much study and reading of the Holy Scriptures she adopted the principles of the reformers and became a dedicated believer, a devout Protestant, studying the Bible and memorizing verses, and remained true to her belief for the entirety of her life. Her reading convinced her of the falsity of the doctrine of transubstantiation, and her pronouncements created some controversy in Lincoln.

Her husband was a Catholic, and the resultant marriage was brutal. Askew had two children with Kyme before he threw her out for being Protestant. It is alleged that Askew was seeking to divorce Kyme, so this did not upset her.

Upon being thrown out, Askew moved to London. Here she met other Protestants, including the Anabaptist Joan Bocher, and they studied the Bible together. Askew stuck to her maiden name, rather than her husband's name. While in London, she became a "gospeler --someone who knew large parts of the bible by heart and could preach about them. The ban on Bible reading had intensified the hunger for it, and those who knew the Bible well became lay preachers. As a woman of high social status, this was bound to attract the attention of the authorities.

In March 1545, her husband Thomas Kyme had Askew arrested. She was brought back to Lincolnshire, where he demanded that she stay. The order was short lived; she escaped and returned to London to continue preaching. In early 1546 she was arrested again, but released. In May 1546 she was arrested again, and tortured in the Tower of London. She was then cross examined by the chancellor of the Bishop of London, Edmund Bonner. He ordered that she be imprisoned for 12 days. During this time she refused to make any sort of confession.

She was ordered to name like-minded women, but refused. She was then subject to a two-day-long period of cross examination led by Chancellor Sir Thomas Wriothesley, Stephen Gardiner, The Bishop of Winchester (John Dudley), and Sir William Paget (the king's principal secretary). They threatened her with execution, but she still refused to confess or to name fellow Protestants. She was then ordered to be tortured. Her torturers did so, probably motivated by the desire for Askew to admit that Queen Catherine was also a practicing Protestant.

According to her own account, and that of gaolers within the Tower, she was tortured only once. She was taken from her cell, at about ten o'clock in the morning, to the lower room of the White Tower. She was shown the rack and asked if she would name those who believed as she did. Askew declined to name anyone at all, so she was asked to remove all her clothing except her shift. Askew then climbed onto the rack, and her wrists and ankles were fastened. Again, she was asked for names, but she would say nothing.

What was exceptional about Anne was that despite being arrested, interrogated, and put on the rack (a device so fearful that most victims confessed whatever was required of them), she refused to give names or implicate others, including women at court close to Queen Catherine Parr. She also refused to be silent, arguing forcefully and confounding her accusers with her knowledge and learning.

Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, was so impressed with the way Anne behaved that he refused to torture her. King Henry VIII's Lord Chancellor Wriothesley and Sir Richard Rich had to take over. Other accounts say it was Anne's obstinacy that so enraged Wriothesley that he turned the rack himself.

In her own words, Anne said, "Then they did put me on the rack because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen to be of my opinion; and thereon they kept me a long time and because I lay still and did not cry, my Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands till I was nigh dead."

The wheel of the rack was turned, pulling Askew along the device and lifting her so that she was held taut about 5 inches above its bed and slowly stretched. In her own account written from prison, Askew said she fainted from pain, and was lowered and revived. This procedure was repeated twice. They turned the handles so hard that Anne was drawn apart, her shoulders and hips were pulled from their sockets and her elbows and knees were dislocated. Askew's cries could be heard in the garden next to the White Tower where the Lieutenant's wife and daughter were walking. Askew gave no names, and her ordeal ended when the Lieutenant ordered her to be returned to her cell.

On 18 June 1546, she was convicted of heresy, and was condemned to be burned at the stake. Because of the torture she had endured, she had to be carried to the stake on a chair wearing just her shift as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. She was dragged from the chair to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck.

Prior to their death, the prisoners were offered one last chance at pardon. Bishop Shaxton mounted the pulpit and began to preach to them. His words were in vain, however. Askew listened attentively throughout his discourse. When he spoke anything she considered to be the truth, she audibly expressed agreement; but when he said anything contrary to what she believed Scripture stated, she exclaimed: "There he misseth, and speaketh without the book."

Her body was covered in gunpowder before her execution. This was seen as a kindness. Friends often placed gunpowder on the condemned, as it hastened what could be a very slow and painful death. But because she had obstinately defied authority, she was burned alive slowly rather than being strangled first or burned quickly.

So many people turned out for the execution that there was hardly enough room to carry it out. The crowd had to be pushed back. Those who saw her execution were impressed by her bravery, and reported that she did not scream until the flames reached her chest. The execution lasted about an hour, and she was unconscious and probably dead after fifteen minutes or so.

At her execution there was a sudden thunderstorm and a loud clap of thunder. Bale wrote that “Credibly I am informed by various Dutch merchants who were present there, that in the time of their sufferings, the sky, abhorring so wicked an act, suddenly altered colour, and the clouds from above gave a thunder clap, not unlike the one written in Psalm 76. The elements declared the high displeasure of God for so tyrannous a murder of innocents.

Anne Askew was burned at the stake at Smithfield, London, at the age of 26, on 16 July 1546. She burned to death, along with three other Protestants, John Lascelles, Nicholas Belenian and John Adams. She was the last martyr in the reign of Henry VIII.

Her crime? Knowing the Bible, preaching the true gospel and the falsity of Catholic doctrine, especially the doctrine of transubstantiation, and handing out Protestant leaflets.

Of all the stupid and suicidal mistakes that the Romish Church ever made, none was greater than the mistake of burning the Reformers. It cemented the work of the reformation and made Englishman Protestants by the thousands. When plain Englishman saw the church of Rome so cruelly wicked and Protestants so brave, they ceased to doubt on which side was the truth. May the memory of our martyred Reformers never be forgotten until the Lord comes!"

[sources: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne_Askew

http://historysheroes.e2bn.org/hero/whowerethey/4265]

#reformation month#reformation#reformed theology#church history#martyrs#christianity#christian#theology#theology matters

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Martyrdom of Anne Askew

Anne Askew was burned at the stake at Smithfield, London, at the age of 26, on July 16, 1546, 472 years ago today. She was born in 1521 in Lincolnshire, England, to William Askew, a wealthy landowner. Anne was a woman of courage and strong beliefs. She was tortured in the Tower of London and burned alive as a Protestant heretic for preaching the Gospel in London and handing out Protestant leaflets.

William Askew had arranged that his eldest daughter, Martha, be married to Thomas Kyme. When Anne was 15 years old, Martha died. Her father decided Anne would take Martha's place in the marriage to Thomas to save money. She was a woman of very strong and sincere beliefs. In her early life she showed an interest and ability for theological studies. Anne was converted to Protestantism when the 'new bible' emerged from the continent. After much study and reading of the Holy Scriptures she adopted the principles of the reformers and became a dedicated believer, a devout Protestant, studying the Bible and memorizing verses, and remained true to her belief for the entirety of her life. Her reading convinced her of the falsity of the doctrine of transubstantiation, and her pronouncements created some controversy in Lincoln. Her husband was a Catholic, and the resultant marriage was brutal. Askew had two children with Kyme before he threw her out for being Protestant. It is alleged that Askew was seeking to divorce Kyme, so this did not upset her. Upon being thrown out, Askew moved to London. Here she met other Protestants, including the Anabaptist Joan Bocher, and they studied the Bible together. Askew stuck to her maiden name, rather than her husband's name. While in London, she became a "gospeler --someone who knew large parts of the bible by heart and could preach about them. The ban on Bible reading had intensified the hunger for it, and those who knew the Bible well became lay preachers. As a woman of high social status, this was bound to attract the attention of the authorities. In March 1545, her husband Thomas Kyme had Askew arrested. She was brought back to Lincolnshire, where he demanded that she stay. The order was short lived; she escaped and returned to London to continue preaching. In early 1546 she was arrested again, but released. In May 1546 she was arrested again, and tortured in the Tower of London. She was then cross examined by the chancellor of the Bishop of London, Edmund Bonner. He ordered that she be imprisoned for 12 days. During this time she refused to make any sort of confession. She was ordered to name like-minded women, but refused. She was then subject to a two-day-long period of cross examination led by Chancellor Sir Thomas Wriothesley, Stephen Gardiner, The Bishop of Winchester (John Dudley), and Sir William Paget (the king's principal secretary). They threatened her with execution, but she still refused to confess or to name fellow Protestants. She was then ordered to be tortured. Her torturers did so, probably motivated by the desire for Askew to admit that Queen Catherine was also a practicing Protestant. According to her own account, and that of gaolers within the Tower, she was tortured only once. She was taken from her cell, at about ten o'clock in the morning, to the lower room of the White Tower. She was shown the rack and asked if she would name those who believed as she did. Askew declined to name anyone at all, so she was asked to remove all her clothing except her shift. Askew then climbed onto the rack, and her wrists and ankles were fastened. Again, she was asked for names, but she would say nothing. What was exceptional about Anne was that despite being arrested, interrogated, and put on the rack (a device so fearful that most victims confessed whatever was required of them), she refused to give names or implicate others, including women at court close to Queen Catherine Parr. She also refused to be silent, arguing forcefully and confounding her accusers with her knowledge and learning. Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, was so impressed with the way Anne behaved that he refused to torture her. King Henry VIII's Lord Chancellor Wriothesley and Sir Richard Rich had to take over. Other accounts say it was Anne's obstinacy that so enraged Wriothesley that he turned the rack himself. In her own words, Anne said, "Then they did put me on the rack because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen to be of my opinion; and thereon they kept me a long time and because I lay still and did not cry, my Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands till I was nigh dead." The wheel of the rack was turned, pulling Askew along the device and lifting her so that she was held taut about 5 inches above its bed and slowly stretched. In her own account written from prison, Askew said she fainted from pain, and was lowered and revived. This procedure was repeated twice. They turned the handles so hard that Anne was drawn apart, her shoulders and hips were pulled from their sockets and her elbows and knees were dislocated. Askew's cries could be heard in the garden next to the White Tower where the Lieutenant's wife and daughter were walking. Askew gave no names, and her ordeal ended when the Lieutenant ordered her to be returned to her cell. On 18 June 1546, she was convicted of heresy, and was condemned to be burned at the stake. Because of the torture she had endured, she had to be carried to the stake on a chair wearing just her shift as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. She was dragged from the chair to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck. Prior to their death, the prisoners were offered one last chance at pardon. Bishop Shaxton mounted the pulpit and began to preach to them. His words were in vain, however. Askew listened attentively throughout his discourse. When he spoke anything she considered to be the truth, she audibly expressed agreement; but when he said anything contrary to what she believed Scripture stated, she exclaimed: "There he misseth, and speaketh without the book." Her body was covered in gunpowder before her execution. This was seen as a kindness. Friends often placed gunpowder on the condemned, as it hastened what could be a very slow and painful death. But because she had obstinately defied authority, she was burned alive slowly rather than being strangled first or burned quickly. So many people turned out for the execution that there was hardly enough room to carry it out. The crowd had to be pushed back. Those who saw her execution were impressed by her bravery, and reported that she did not scream until the flames reached her chest. The execution lasted about an hour, and she was unconscious and probably dead after fifteen minutes or so. At her execution there was a sudden thunderstorm and a loud clap of thunder. Bale wrote that “Credibly I am informed by various Dutch merchants who were present there, that in the time of their sufferings, the sky, abhorring so wicked an act, suddenly altered colour, and the clouds from above gave a thunder clap, not unlike the one written in Psalm 76. The elements declared the high displeasure of God for so tyrannous a murder of innocents.

#anne askew#protestant#reformation#protestant reformation#tudor#tudors#tudor history#16th century#history#christianity

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coronation of a Tudor Boy King

Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547, leaving his son, Edward Tudor, to inherit the English throne.

At first, Henry’s death was a secret even to his only surviving legitimate son, Edward Tudor. His uncle – Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford – and Sir Anthony Browne escorted Edward to Enfield Manor in Middlesex. Then Hertford announced the tragic news to his nephew.

Now Hertford had to put the boy king on the throne and to secure his own dominance in the government. Hertford’s plan was to take Edward to London and to arrive at the Tower of London on the 31st of January, 1547.

As the young Edward VI and his closest entourage were setting off from Enfield, the proclamation of his accession to the English throne was being read in Westminster Hall. Few inhabitants of England remembered the last time a monarch was proclaimed to his people. It had last happened in 1509, when the Henry VIII, two months away from his eighteenth birthday, had been the great hope for a glorious and prosperous future for England after Henry VII’s death.

A few days after the late king’s death, the council of sixteen executors (Council of Regency), appointed by Henry VIII, met together at the Tower of London. The late king had made a final revision to his last will and testament on the 30th of December, 1546. This document confirmed the line of succession: Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth, and, following them, the Grey and Suffolk families. The councilors proclaimed their loyalty to Henry’s last will and testament.

The Council of Regency chose to give the Earl of Hertford almost regal power, making him ‘the Protector of the king’s realms and dominions and Governor of his most royal person’. The ambitious Hertford must have done a deal with some of the executors, including with William Paget, private secretary to Henry VIII, and with Sir Anthony Browne, Master of the Horse.

The following day, all of these councilors met again in the Tower to hear Henry’s will read out from beginning to end. Then they all visited Edward V and took their oaths of fealty to their new sovereign. They also secured Edward’s consent to their election of Hertford as Lord Protector and Governor.

Edward was surrounded by his father’s executors and the members of the English nobility, who all treated him as their new king. He must have been overwhelmed with awe, as he watched the theater of monarchy where he himself was the chief actor.

The Council of Regency planned down to the last word and gesture the form of Edward’s coronation in Westminster Abbey. In spite of being very young, Edward must have understood that his father’s death changed his life, and he became a king who had many subjects. Yet, the boy king wasn’t able to comprehend the tough world of Tudor court politics and the intricacies of state affairs. Edward was a boy king, who flourished in a lively court life, but who could not rule for himself.

On the 14th of February, 1546, Elizabeth Tudor, Edward’s sister, made clear her loyalty:

“May God long keep your majesty safe and further advance (as He has begun to do) your growing virtues to the utmost. From Enfield the 14th of February.

Your Majesty’s most humble servant and sister, Elizabeth.”

On the 20th of February, 1547, the lavish coronation ceremony of Edward VI took place in Westminster Abbey.

Actually, the pre-ceremonies actually began the day before the official event. In the afternoon of the 19th of February, the boy king left the Tower of London and processed through the streets of London. The boy king was richly attired in dazzling white velvet, embroidered in silver thread and decorated with lovers’ knots made from pearls, diamonds, and rubies. The royal messengers, gentlemen, trumpeters, chaplains, and esquires were all walking; they were followed by the nobles and foreign ambassadors on horseback.

Coronation of King Edward VI

On the way to Westminster Abbey, King Edward VI walked under a canopy, carried by the barons of the Cinque Ports.

The king’s uncle, Edward Seymour, who was the Lord Protector of the English realm, stalked ahead of his nephew, carrying the crown. The Duke of Suffolk carried “the ball of golde, with the crosse”, while the Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset, carried the scepter. Edward was flanked by the Earl of Shrewsbury and the Bishop of Durham, followed by John Dudley, Thomas Seymour, and William Parr, Marquess of Northampton, who all bore the boy king’s train.

King Edward VI’s coronation

Chronicler Charles Wriothesley wrote of this event:

“The twentith daie of Februarie, being the Soundaie Quinquagesima, the Kinges Majestie Edward the Sixth, of the age of nyne yeares and three monthes, was crowned King of this realme of Englande, France, and Irelande, within the church of Westminster, with great honor and solemnitie, and a great feast keept that daie in Westminster Hall which was rychlie hanged, his Majestie sitting all dynner with his crowne on his head; and, after the second course served, Sir Edward Dymmocke, knight, came ridinge into the hall in clene white complete harneis, rychlie gilded, and his horse rychlie trapped, and cast his gauntlett to wage battell against all men that wold not take him for right King of this realme, and then the King dranke to him and gave him a cupp of golde; and after dynner the King made many knightes, and then he changed his apparell, and so rode from thence to Westminster Place.”

Due to Edward’s youth, the traditional coronation ceremony, used since 1375 and described in the Liber Regalis, had been altered. It had been shortened because of his young age: it took only seven hours instead of the standard twelve hours.’ The length of the coronation banquet had been cut as well.

One of the most notable changes was that the role of churchmen, who were traditionally the intermediaries between God and the monarch, was significantly reduced. According to Chris Skidmore’s book “Edward VI: The Lost King of England”, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, had also modified the coronation oath so that “Reformation of the Church could now be enabled by royal prerogative, the king as a lawmaker”.

Sitting on his throne, Edward VI was then anointed and crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury with three crowns: the St Edward’s crown, the imperial crown, and a custom-made lighter crown.

Trumpets blew between each crowning, and the choir then sang a Te Deum, which was the traditional accompaniment to this part of the ceremony. A ring of gold was set on Edward’s finger; then Edward Seymour, the Lord Protector, and other nobles approached their king and kissed his left cheek.

From the very beginning of Edward VI’s reign, the government was ruled by Edward Seymour, the king’s uncle. Driven by ambition and greed, Hertford created for himself a portfolio of lofty titles and offices by March 1547: he was Duke of Somerset, Earl of Hertford, Viscount Beauchamp, Lord Seymour, Governor of the king, Protector of his people, realms and dominions, Lieutenant General of his Majesty’s land and sea armies, Treasurer, Marshal of England, and Knight of the Garter. Although at first, he had to act upon the advice and consent of Henry VIII’s executors, soon Edward Seymour began to govern like an absolute monarch.

The story of Edward Seymour and his brother, Thomas Seymour, will be covered in other articles.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2018 Olivia Longueville

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day in history, 6th July 1535, Henry VIII’s former friend and Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas More, was beheaded on Tower Hill as a traitor. He had been found guilty of high treason under the Treason Act of 1534 for denying the King’s supremacy and refusing to take the Oath of Succession.

Chronicler Charles Wriothesley recorded his death as follows:

“This yeare allso, the first day of Julie, beinge Thursdaye, Sir Thomas More, knight, sometyme Chauncellor of England, was arreigned at Westminster for highe treason and there condemned, and the Tuesday after, beinge the 6th of Julie, he was beheaded at the Tower Hill, and his bodie was buried within the chappell in the Tower of London, and his head was sett on London Bridge. The effect of his death was for the same causse that the Bishopp of Rochester died for.”

Chronicler Edward Hall wrote:

“Also the vi. day of Julye was sir Thomas More beheaded for the like treason before rehersed, which as you haue heard was for the deniyng of the kynges Maiesties supremitie. This manne was also coumpted learned, & as you haue heard before he was lorde Chauncelor of England, and in that tyme a great persecutor of suche as detested the supremacy of the bishop of Rome, whiche he himselfe so highly fauored that he stoode to it till he was brought to the Skaffolde on the Tower hill where on a blocke his head was striken from his shoulders and had no more harme.

I cannot tell whether I should call him a foolishe wyseman, or a wysefoolishman, for vndoubtedly he beside his learnyng, had a great witte, but it was so mingled with tauntyng and mockyng, that it semed to them that best knew him, that he thought nothing to be wel spoken except he had ministered some mocke in the communcacion insomuche as at is commyng to the Tower, one of the officers demanded his vpper garment for his fee, meanyng his goune, and he answered, he should haue it, and tooke him his cappe, saiyng ii was the vppermoste garment that he had. Lyke-wise, euen goyng to his death at the Tower gate, a poore woman called vnto him and besought him to declare that he had certain euidences of hers in the tyme that he was in office (which after he was appreheded she could not come by) and that he would intreate she might haue themagayn, or els she was vndone. He answered, good woman haue pacience a litle while, for the kyng is so good vnto me that euen within this halfe houre he will discharge me of all busynesses, and helpe thee himselfe. Also when he went vp the stayer on the Skaffolde, he desired one of the Shiriffes officers to geue him his hand to helpe him vp, and sayd, when I come doune againe, let me shift for my selfe aswell as I can. Also the bagman kneled doune to him askyng him forgiuenes of his death (as the maner is) to whom he sayd I forgeue thee, but I promise thee that thou shalt neuer haue honestie of the strykyng of my head, my necke is so short. Also euen when he shuld lay doune his head on the blocke, he hauyng a great gray beard, striked out his beard and sayd to the hangman, I pray you let me lay my beard ouer the blocke least ye should cut it, thus with a mocke he ended his life.”

A document in Letters and Papers gives the following information about More after his trial and about his execution:

“On his way to the Tower one of his daughters, named Margaret, pushed through the archers and guards, and held him in her embrace some time without being able to speak. Afterwards More, asking leave of the archers, bade her have patience, for it was God’s will, and she had long known the secret of his heart. After going 10 or 12 steps she returned and embraced him again, to which he said nothing, except to bid her pray to God for his soul; and this without tears or change of colour. On the Tuesday following he was beheaded in the open space in front of the Tower. A little before his death he asked those present to pray to God for him and he would do the same for them [in the other world.] He then besought them earnestly to pray to God to give the King good counsel, protesting that he died his faithful servant, but God’s first.

Such was the miserable end of More, who was formerly in great reputation, and much loved by the King, his master, and regarded by all as a good man, even to his death.”

Memorial plaque on Tower Hill

As Wriothesley says, his body was buried at the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula, at the Tower of London, and his head put on a spike on London Bridge. Heads would eventually be thrown into the River Thames but More’s wasn’t. E E Reynolds, in the book Margaret Roper: Eldest Daughter of St Thomas More, quotes Thomas Stapleton, an early biographer of Thomas More:

“[The head] by order of the king, was placed upon a stake on London Bridge, where it remained for nearly a month, until it had to be taken down to make room for other heads … The head would have been thrown into the river had not Margaret Roper, who had been watching carefully and waiting for the opportunity, bribed the executioner, whose office it was to remove the heads, and obtained possession of the sacred relic. There was no possibility of mistake, for she, with the help of others, had kept careful watch, and, moreover, there were signs so certain that anyone who had known him in life would have been able now to identify the head.”

Reynolds then explains:

“After the death of Margaret Roper, the head was in the keeping of her eldest daughter, Elizabeth, Lady Bray, and it was probably at her death in 1558 that it was placed in the Roper vault under the Chapel of St. Nicholas in St. Dunstan’s, Canterbury.

It was seen there in 1835 when, by accident, the roof of the vault was broken; the head was enclosed in a leaden case with one side open; this stood in a niche protected by an iron grille. The vault was later sealed, but a tablet in the floor above bears the inscription:

Beneath this floor is the vault of the Roper family in which is interred the head of Sir Thomas More of illustrious memory, sometime Lord Chancellor of England, beheaded on Tower hill 6th July 1535. Ecclesia Anglicana libera sit.”

In an article “The scull [sic] of Sir Thomas More”, in The Gentleman’s Magazine of May 1837, there is the following quote about More’s head being seen in the vault in the 18th century, along with the drawing of the skull which you see at the top of this article: “Dr. [then Mr.] Rawlinson informed Hearne, that when the vault was opened in 1715, to enter into one of the Roper’s family, the box was seen enclosed in an iron grate.”

It must still be there.

4 notes

·

View notes