#Shugenja

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Isawa Atsuko by Vuogle

#Legend of the Five Rings#L5R#Rokugan#Phoenix Clan#Shugenja#Isawa Atsuko#Fantasy#Art#Vuogle#FFG#Fantasy Flight Games

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

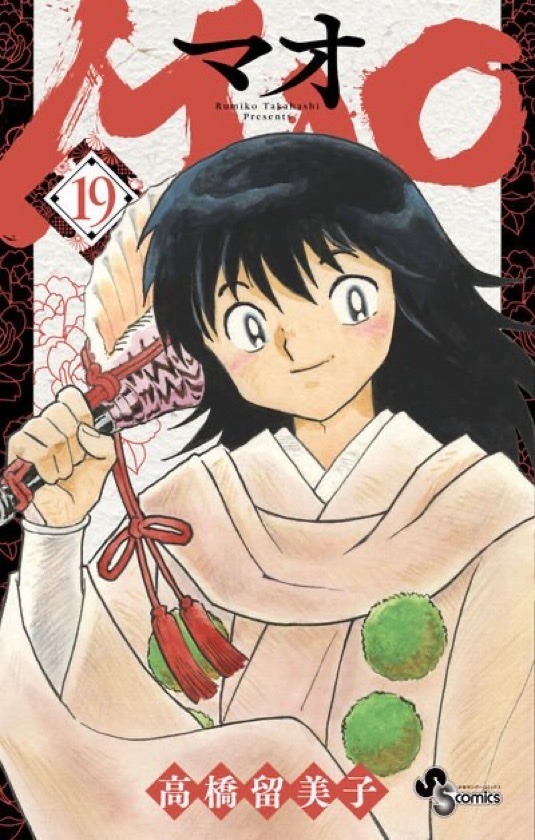

Sasuga cover my beloved 😍

I’m pretty sure this volume includes the conclusion of the sacrificial village arc, so of course he gets the cover at last ✨✨✨

(I also really like that Tenko was the previous cover, as she’s the one who sent Nanoka and co. to the village to start ^^)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shosuro Takashi, my Scorpion samurai using the forbidden maho technique >:)

Evil cunning bastard, I love him so much)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

L5R Scorpion clan Shugenja- Soshi Akane

#rox art#digital art#rox oc's#akane soshi#l5r#ttrpg oc#ttrpg#ttrpg art#illustration#character art#character design#scorpion clan#Soshi#shugenja

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

" are you upset? i hope not if so, i can at the very least bake a dessert for better spirits." even though he was created into this intelligent being, albedo has had many years to perfect personable feelings and when to apply empathy. " my calculations may be wrong, but i'd very much like to help you if i can." / @shugenja

#✶ ⋆。˚ ⁀ albedo. // 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐩𝐬 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐜𝐞𝐮𝐬.#shugenja#albedo is so kind i cant akdfjaf#he's super good w/ empathy and sensing inner turmoils#also i left this open for pre-estab or new encounter - whichever you like!! :)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐄𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐝𝐫𝐨𝐩 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐭𝐮𝐝𝐞 𝐞𝐯𝐚𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬 with each passing moment. Though he is human in body, much of his composition bears greater resemblance to his predecessor than to the people he dwells amongst now. As such, the brunt of the scorching sun only leaves him staggering, once more wishing that he’d not agreed to this excursion. That he could be once again within the safe and comfortable borders of Fontaine, surrounded by his element.

Yet here he is, trudging through so much sand, ready to collapse if not for the wellspring of his own power keeping him upon his own two feet. “You are… sure that she dwells here?” His voice is as dry as the desert itself, a rasp of wind against withering leaves. He disdains from wiping sweat from his brow with his sleeve, but that might very well be his reality with the kerchief he’s used is already drenched. / @shugenja

#shugenja#❛ㅤ⚜ㅤㅤㅤ✦ㅤ:ㅤrise from the soundless deepㅤㅤ◟ㅤmainㅤ◝#❛ㅤ⚜ㅤㅤㅤ✦ㅤ:ㅤunto a serene seaㅤㅤ◟ㅤicㅤ◝#pls pick him up and carry him

0 notes

Text

@shugenja s.c

"I have the sinking suspicion you've come here for an IMPORTANT reason?" He didn't seem like the sort that just wanted to admire the scenery.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yanqing had no idea where he was as he was surfing on one of his swords as it hovered above the ground a little, his eyes darting around before he would venture forth.

Everything looked so lush and green here, was this like a jungle?

Nothing made sense to the youth as he advances a little more, remaining as cautious as can be.

@shugenja

#shugenja#distant worlds[ crossovers ]#rps#small starters#hope this is good friend :D boi is lost in Sumeru

0 notes

Text

A Scorpion's Song

Bearing the instrument into the empty halls took all of her strength. She could not sling it about like any other burden; it needed to be handled gently, the weight managed, not merely endured. And she'd born burdens enough in the past years, this one too many, one too heavy for her.

Her knees buckled; she sank to the floor, feeling the old, crackling tatami give beneath her slight weight. Trembling with weariness, she kept her hands locked about the wrapped weight in her arms, held hard against her belly, until she and the floor reached their tentative agreement.

Gently, Kyako let the koto slide down her thighs to rest on the dusty floor. Her arms ached, relieved of the weight. She sat on her heels, flexing her fingers, and looked at the empty hall. The golden eyes she'd inherited, that she hated with all her heart, swept the water-stained tatami, the tattered remnants of shoji. When she twisted to stretch her lower back, the ink-and-plaster mural stretching high overhead mocked her with memory.

Yes, the scent of fresh plaster and wet ink existed only in her thoughts, but oh how vividly she recalled those smells accompanying the slap of plaster on the wall, the chatter of her sisters as they mixed ink, the distant bustle of feet moving throughout the Soshi home. On that day, with their fate only bearing down upon them but not yet present, the household and Kyako's life held only the banality of peace.

She exhaled, untying the silk, and smoothed it away from the strings of her koto. With a few delicate adjustments, Kyako tightened the twisted silk strings that needed attention, folded the silk wrapper back to let the instrument gleam, and sat on her heels. Her nails caught briefly on a string when she reached to pluck them; she watched mutely as blood welled from her fingertip.

When had she last knelt by her koto to play?

Kyako's mask moved slightly; she wiped blood off onto the hem of her skirt before reaching up to adjust the lay of heavy silk across the bridge of her nose. Even being here, here of all places, where she'd first been given her mask, taught the meaning of it, had the pride she wore it with instilled in her... She could not simply remove it. Would not. Not even here, where she'd vowed to keep her face all, save the kami and the spouse she'd never managed to obtain.

A laugh sounded, in tune with the string she plucked.

"I broke that vow, Mother," Kyako said aloud. "Not as you feared. I have never taken the mask from my face in public. But the man who fathered my child saw my face in the three nights we shared. And I saw his." Her mask shifted again as her golden eyes warmed. "Ryuki inherited his eyes, the kami were merciful in that. She is well, last I saw."

Her fingertips stroked over the strings, careful not to draw notes from them just yet. "I left her. As you did me. I wonder if your reasoning differed from mine." Kyako curled a fingertip, plucking a string with the tip of her nail. "I wonder if it matters."

...or if it ever would.

Rational explanations, after all, did not change the actions they sought to clarify.

Her family, save for one estranged daughter, were still dead, after all. Her household, those who'd contributed to a household, to the thriving of a samurai family, were still dead. All of them.

Except for her.

Kyako closed her eyes, adjusting her posture, and laid her fingertips on the strings. Notes drifted through her mind, forming into chords, and she recalled a song that she'd first learned a decade prior, living on sufferance in a household that displayed her as a novelty.

With the first notes she plucked, blood stained the strings, running down her fingers to soak into the dusty tatami, to bead on the polished wood of the koto. Kyako fed the abandoned household with blood and music, head bowed over the strings.

In the light of the lantern she'd set in the hall, she moved her hands across the strings. A few drops of blood from freshly sliced fingertips flicked over the koto, staining the tatami.

And she felt them gathering, drawn towards the light of her lantern, the warmth of her blood, the life that she brought back into the long-abandoned Soshi hall.

Not many remained, she'd not expected the household itself to linger in the walls once painted by their hands only to be stained by their screams.

Those that came... She knew.

Kneeling to her left came Hideyuki who cleaned fireplaces and carried water, his strong forearms always tensed in her memory, his broad hands occupied with loads of wood, buckets of water, a heavy stone to repair one of the wells.

Beside him, her father's favorite man, Ichiro. Kyako recalled so little of him, save as her father's shadow. And the hands which had clasped her own when she, as a very small child, stumbled and fell. He'd helped her to her feet, wiped away a tear, smiled at her insistence on smoothing her clothing down. He'd laughed, too loudly for the halls, and never apologized.

Kyako's chest tightened as she felt him beside her.

His name rested on her lips, unspoken, and Kyako's hands continued to move across the strings.

Nobu.

Under his eyes, she'd sat for months to learn the very instrument she now played. Under his eyes, she'd embroidered and read, studied and played. Under his cool grey eyes, for the earliest years of her life, she'd walked to her bed with Nobu at her right shoulder, three strides behind her.

Nobu stood beside her, behind her, with his arms crossed. Just as he'd stood the day they broke down the front gates, waiting for the command to be given to get her safely out of the compound.

And it'd been Nobu, behind her, who'd taken the blade intended to take her life.

One note after another, played in sequence, and music rippled through the room. Kyako played on, adjusting the placement of her fingertips, using the tips of her nails when the strings sliced too deep. Every string she touched turned a brilliant red, fading into a dull rusty brown, tiny droplets of blood rising in a spray that stained her pale hands as she continued to play.

Her offering to those who'd died in these halls--pain and music and blood.

And their acceptance of it... She felt it.

They listened to the music, taking as much from her presence as she took from theirs, and Kyako's mask shifted delicately as she smiled.

Even when no Soshi lived, something of them would remain.

#Art Challenge Entry#Screenshots#This is technically a Legend of the Five Rings piece#Soshi Kyako was my shugenja#Scorpion4Lyfe#OOC

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moshi Ikako (Experienced) by Mario Wibisono

#Legend of the Five Rings#L5R#Mantis Clan#Shugenja#Fantasy#Art#Moshi Ikako#Maio Wibisono#FFG#Fantasy Flight Games

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey. Not dead.

Got sucked into a whirlwind of life, what with the summer hurricanes, school, work, and yearly Midwest travels. Hope I was missed lol.

Have some old masa doodles I did based off an AU of mine, in which Masa gets possessed instead of Momo. Bc tell me, you expect me to believe that Masa just sat there crying while his apricot ronin bled out on Hatch’s dojo floor?? Nah fam, this mfer probably summoned the power of satan to keep his ronin alive(remember when Haku or someone commented that it’s a miracle that MC didn’t die from their Jun wounds?? This is the twist villain we never knew we needed) It’s one of my favorite AUs (and a former theory of mine) that I don’t get to talk much about. Lemme know if y’all wanna see more of this AU, I’d be happy to revisit!

Dark!Masa is just Masa going through his edgy teenage phase and I’m here for it🖤💔

#Dark!Masa is just him w his hair down and a black haori lol#he and Ronin sort of switch roles after book 2#Masa becomes disillusioned and vows vengeance against jun and all the other demon evils for hurting his ronin#remember how in B1 they mentioned that shugenja’s nit in the army are deemed a national threat? ya masa becomes that#bc the evil demon ghost lady tells him that it’s Satsu’s fault that MC is in peril bc he’s is making them go on this journey in the 1stplace#samurai of hyuga#SoH#choice of games#hosted games#interactive fiction#cog#devon connell#my art#hg#AU#Dark!Masa AU

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

i was so hyped for the last episode of this season of nrb plays botc but it was kind of disappointing

#there was everything there for it to be great#but the good team had too good of info and figured out the evil team really quickly ://#i think ben should have widow poisoned either blair or chris instead of holly#since having a virgin's ability malfunction or giving a flower girl incorrect info would be way more damaging. in my opinion#especially since we got that day 1 play from chris too it would have made either chris or sully look soooo evil#which would explain away the correct shugenja info in that case#sorry not to ramble but i was really excited when i saw the roles and having ben as a player but then it was kind of meh :/ oh well#maybe the patreon one this month is better i haven't watched it yet#also i hope they do a season 3. i know they're kickstarting the dnd series right now but i want another season of in person botc so much ;-#what do you have to say doll?

1 note

·

View note

Text

"A god of tengu-warding": uncovering the connection between Okina and tengu

There’s something uniquely magical and captivating about Okina’s dialogue in HSiFS that neither subsequent final bosses nor even her own subsequent appearances manage to capture. Probably no other character managed to directly reference quite as many myths and religious concepts in her debut game appearance. And yet, without context many of these probably seem borderline nonsensical. Interviews and supplementary material sometimes help, but even that isn’t guaranteed. This article will focus on only one such instance, the notoriously mystifying exchange between her and Aya which simultaneously casts her as a “god of tengu-warding” and implies a degree of kinship between them. What does this mean? Why does Okina have something to do with tengu in the first place? Where do tengu come from, anyway? Why crow tengu aren’t necessarily crows? Why is it possible to make a case for Byakuren being a tengu? This - and more - will be explored under the cut.

Matarajin and tengu, from tengu odoshi to Hidden Star in Four Seasons

In Aya’s route in Hidden Star in Four Seasons, Okina calls herself “a god of tengu-warding”. This is actually not something ZUN invented. Matarajin was the focus of a medieval Tendai Buddhist ritual known as tengu odoshi (天狗怖し) - “placating the tengu”. He was most likely himself understood as a tengu in this context. As such, he had to be placated by the monks performing the ritual, whose chaotic actions - chiefly noisy recitation of random sutras coupled - were meant to imitate his own behavior.

This approach is somewhat unusual: in many other similar ceremonies an appropriate deity or deities would simply be invoked to get rid of demonic interlopers. Here the risk of obstruction is so great that only by pretending to play along with it victory can be attained. Or, alternatively, perhaps to get rid of Matarajin and other tengu, the monks had to beat them at their own game by creating an even more disorderly display. Yet another option is that Matarajin had to be attracted with the ritual in order to ward off other, lesser tengu. No matter which interpretation is correct, it is evident there was a direct connection between them.

Matarajin and his attendants (Rhode Island School of Design Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only) As a curiosity it’s worth pointing out that it has been suggested that tengu odoshi and other similar rituals and festivals might have resulted in the development of Matarajin’s well known role as a deity of the performing arts, especially noh, exemplified by his equation with a stock character from sarugaku, Okina, an auspicious old man represented by a characteristic bearded mask. Comparisons have also been made between the tengu odoshi and rituals involving Matarajin’s attendants Chōreita Dōji (丁令多童子) and Nishita Dōji (爾子多童子). Fittingly, one of the spell cards of their Touhou counterparts Mai and Satono is named Mad Dance "Tengu-Odoshi".

Shizuka Gozen performing in typical shirabyōshi attire, as depicted by Hokusai (wikimedia commons)

While this is only tangentially related to Matarajin, it’s worth pointing out that according to Yasurō Abe, it was also believed that tengu were enthusiasts of the performing arts in general. However, while Matarajin was associated with noh, tengu favored an earlier form of entertainment, shirabyōshi (白拍子). This term refers to a type of female dancer who performed in male formal wear. The reference to tengu enjoying their dances and songs might be an allusion to emperor Go-Shirakawa, who was known for similar artistic tastes and was commonly represented as a tengu in legends.

The association between Matarajin and tengu was also present in shugendō. In Kumano, local shugenja apparently perceived him as a tengu-like deity comparable to Iizuna Gongen (飯縄権現). It’s worth noting this is in theory who Megumu is based on, but tragically ZUN didn’t want to do much with the irl background in her case, so I doubt we'll ever see a reference to this in canon media.

An Edo period depiction of the ox festival of Matarajin (wikimedia commons)

It seems the only other possible reference to Matarajin as a tengu is a depiction of the famous (relatively speaking) Kōryū-ji ox festival from the Edo period Miyako Meisho Zue (都名所圖會) in which the person playing his role wears a tengu-like mask.

Considering ZUN has to be aware of at least some of the scholarship pertaining to Matarajin and tengu - tengu odoshi is not exactly a famous ritual, and most of the search results today are just Touhou - it seems safe to say that he had this very connection in mind. Aya mentions a category of beings she refers to as “people of impairments”, which according to her encompasses both the tengu and their metaphorical relatives who “hid behind Buddhas”, like Okina. This neatly corresponds to their shared role of their counterparts in medieval and early modern Buddhism.

In addition to the connections between Matarajin and tengu discussed above, there are multiple other instances of identifying him as a member of a category of beings usually perceived ambivalently, if not outright negatively, specifically because of their ability to impair the pursuit of enlightenment. If you read my previous post focused on Okina-adjacent topics, you already know that Matarajin was closely associated with dakinis, for instance. It’s worth noting that as an extension of this connection, he could also be associated with foxes. The Edo period treatise Inari Jinja Kō (稲荷神社考, “Reflections on Inari Shrine”) outright says that matarajin, treated as a generic term, not a given name, is one of the the terms which can be used to refer to supernatural foxes.

The oldest presently known reference to Matarajin describes him as a “yasha deity” (夜叉神, yashajin). This term is a loan from Sanskrit yakṣa, and refers to a class of nature spirits or low-ranking deities incorporated into Buddhism from preexisting tradition of India. They are portrayed as generally benevolent and protective. To be a yaksha in origin is no shame for a deity, despite their low status and occasional ambivalence. Bishamonten, who needs no introduction, as well as Konpira, the foremost of the Twelve Heavenly Generals, are both portrayed as yakshas who embraced Buddhism. Even the bodhisattva Kannon seemingly was portrayed as a reincarnation of a female yaksha named Cundī early on. In both China and Japan, the most widespread image of a yaksha is ultimately that of an armed, protective figure.

However, sometimes negative traits can be ascribed to yakshas too. For instance, the Tang period Buddhist scholar Guifeng Zongmi maintained that yakshas are child-eating demons - though he also recorded a custom of dedicating children to them in order to prevent them from harm. The tenth century Tendai monk Genshin stated they were among demonic beings who could potentially obstruct rebirth in a pure land. However, it was possible to solve this problem with the right rites. The examples listed above are just a few glimpses of one of the most recurring topics in historical Japanese Buddhist literature: there were demons, and even deities (障礙神, shōgejin) keen on impairing the pursuit of enlightenment unless properly placated. This would either ward them off, or even turn them into fierce protectors of Buddhism instead (what ZUN presumably meant by Aya’s comment about “hiding behind Buddhas”). However, most of such beings originated in India and spread alongside new religious movements. How did tengu join their ranks? To answer this question, I will need to go beyond Matarajin and further back in time, to the Heian and Kamakura periods.

Makai, the realm of tengu

A group of Tengu constructing a temple in the tengu realm (wikimedia commons)

The emergence of tengu as a well defined class of beings is fundamentally tied to portraying them as a source of hindrances for practitioners of Buddhism. In the twelfth century, they came to be identified with the concept of ma (魔), a loanword from Sanskrit māra. In this context, it is to be understood as obstruction of enlightenment, or opposition to the Buddha, his teachings and the Buddhist law. There are both internal sources of ma, like doubt and worldly attachment, and external ones. Tengu, generally speaking, fall into the second category.

Tengu were believed to be reincarnations of those who lack bodhicitta (菩提心, bodaishin), the mindset necessary to pursue enlightenment. Those who become tengu at least nominally follow Buddhist teachings, but fail because of arrogance, greed and other earthly attachments. Those who mislead others by promoting incorrect practices also turned into tengu after death.

Many tengu narratives from the Heian period and the middle ages portray them as possessing extraordinary powers, which they use to trick and mislead monks and laypeople alike. They could be referred to as gejutsu (外術), literally “outside techniques”. A related term is gedō (外道), “outside way”. These labels are not necessarily pejorative, and can refer to any practices which are not strictly Buddhist, for example to Confucian or Daoist ones, and in fact some were integrated with Buddhist practices. However, depending on context other options might be preferable. For example, Haruko Wakabayashi went with “wicked sorcery” in her translation of a Konjaku Monogatari tale in which a tengu poses as a buddha in order to mislead laypeople. However, even if tengu could imitate miracles Buddhas and bodhisattvas were believed to perform, their results were only temporary because they lacked true power. In many tales the effects of tengu tricks only last seven days.

According to the Kamakura period anthology Shasekishū (沙石集), not all tengu are malicious, despite their origin. Those who are close to being redeemed, while held back by “superficial wisdom”, curtail the influence of their more malevolent peers and thus act as protectors of Buddhism. They eventually leave the realm of tengu. Other sources indicate that the malign tengu are destined to eventually be reborn as animals.

As already pointed out above, the notion of tengu being opponents of Buddhism already appears in Konjaku Monogatari, composed between 1120 and 1140. The tales involving them appear in the final chapter of the section focused on Buddhism in Japan, which sets them apart from most other supernatural beings. They are instead grouped with accounts of visits in hells and other realms of rebirth, and with narratives explaining the consequences of accumulation of bad karma.

In the Kamakura period, tengu received their own place in the Buddhist cosmos: an entire realm of rebirth. It didn’t replace any of the three other realms where one reincarnates as punishment due to accumulating bad karma - these of hungry ghosts, animals, and hell. It could be sometimes described as a specific hell (one of many) or as a part of the animal realm, but generally it was held to be something distinct. While still perceived negatively, it can effectively be considered a preferable alternative to rebirth as an animal or in hell, since to be reborn as a tengu does not necessarily prevent one from seeking enlightenment.

The realm of tengu was variously referred to as tengudō (天狗道; “realm of tengu”), madō (魔道; “realm of ma”) or makai (魔界; “world of ma”). The last of these terms has been present in Touhou for a while, though never in association with tengu, at least for now. I am aware many people are attached to the PC-98 portrayal of Makai and to Shinki, but I would argue there are endless possibilities in trying to make the medieval understanding of this term work in this context as well. Most notably, the notion of monks who failed in their pursuit of enlightenment would have interesting implications for Byakuren. Following medieval Buddhist logic, one could argue she is essentially already a tengu, even though ZUN refers to “sealing” in Makai, as opposed to being reborn there. She may deny it herself in Symposium of Post-Mysticism, but it's hard to argue with the evidence.

The oldest work establishing the existence of tengudō as a distinct realm of rebirth is Hirasan Kojin Reitaku (比良山古人霊託; “The Spiritual Oracle of the Old Man of Mount Hira”), in which the Tendai monk Keisei (1189–1268) learns about it from a tengu residing on Mount Hira. While left anonymous, the being states that he was alive in the times of Shōtoku and before the rise of Fujiwara no Kamatari to prominence, and explains that due to worldly attachments he was reborn in the realm of tengudō. He then provides information about many of Keisei’s family members and contemporaries, as well as assorted historical figures. Some of them have shared a similar fate, including emperors Sutoku and Goshirakawa and prominent members of Buddhist clergy like Ryōgen, Jien, and many others. Keisei and the anonymous tengu then engage in what I can only describe as a vintage example of power scaling, and start to compare the strength of the individual tengu (as we learn, Go-Shirakawa is more powerful than Sutoku).

Curiously, the anonymous tengu is entirely self-aware, and explains that his mind is filled with illusory thoughts, but proper Buddhist observance can nonetheless save him and other tengu from their current state. He notes that Ryōgen was able to leave the realm of tengu already, for instance. Another peculiar aspect of this account is the explicit reference to female tengu. The protagonist explains to Keisei that his wife is a fellow tengu, though she is only 400 years old. He also specifies many other tengu have families and even children.

A debate in the tengu realm (wikimedia commons)

The Buddhist views on tengu became firmly cemented thanks to the Tengu Zōshi (天狗草紙), a set of seven illustrated scrolls. This work most likely originally arose in the thirteenth century, in an era of conflicts between the well established esoteric schools of Buddhism, Tendai and Shingon, and the newcomers to the scene, like Zen and Pure Land. All parties involved accused each other of spreading false teachings and embracing ma. The new schools did not form a unified front, for clarity: for instance, Nichiren denounced the Shingon establishment about equally enthusiastically as Zen or Pure Land. There were also voices presenting the very act of criticism of other schools as worthy of critique in itself. The goal of Tengu Zōshi was to criticize and satirize the various vices of contemporary Buddhist monks by presenting them as tengu. It states that there are seven kinds of tengu, corresponding to seven different sorts of pride (citing Haruko Wakabayashi: “feeling slightly inferior to those who are greatly superior, feeling superior to those who are inferior and equal to those who are equal, feeling superior to those who are equal and equal to those who are superior, feeling superior to those who are superior, being attached to oneself, committing evil and thinking one is virtuous, and feeling enlightened when one is not).

Five of the tengu types are supposed to represent monks of major temples of this era (Kōfuku-ji, Tōdai-ji, Enryakuji, Onjō-ji, and Tō-ji), the remaining two are yamabushi (mountain ascetics) and “recluses” (tonse). However, the scrolls culminate with a reveal that all of the depicted tengu attained salvation and eventually became Buddhas (save for Ippen, who was instead destined to be reborn in the animal realm). This once again puts an emphasis on tengudō not being quite as bad as the other paths of rebirth which should generally be avoided: one has to actually practice Buddhism in some form to get there in the first place, and it is possible to attain enlightenment as a tengu.

The notion of tengudō and tengu being fallen monks did not vanish after the middle ages, and appears for example in some tales about Yoshitsune’s youth and his training with these beings, for instance in the Miraiki (未来記; literally “chronicle of the future”). Therefore, it is safe to say that this is the closest thing to a universal explanation where do tengu come from. However, their history actually goes even further back.

Cats, comets, dogs and kites: the origin of tengu

A tiangou from the Classic of Mountains and Seas (wikimedia commons)

The history of tengu starts in China. At least the history of the name, that is. The word 天狗, which in Chinese is read as tiangou, already occurs in the Classic of Mountains and Seas, probably composed at some point in the second half of the first millennium BCE, either near end of the Warring States Period or in the beginning of the reign of the Han dynasty. While tiangou can be literally translated “celestial dog”, the creature is actually compared to a wildcat with a white head, and makes catlike sounds on top of that. It is also said to repel evil forces. This quality is also reaffirmed by the poet Guo Pu, who additionally states the tiangou is so small that a ruler could either eat it or wear it as a belt ornament to make use of its protection.

Next to this whimsical image of a benevolent supernatural creature, the term tiangou was also used to refer to comets and similar celestial phenomena. This meaning of the term entered Buddhist texts, for example in the Sutra on the Bases of Mindfulness of the True Dharma (正法念處經, Chinese Zhengfa Nianchu Jing, Japanese Shōbō Nenshokyō), tiangou serves as a translation of the Sanskrit term ulka, which refers to meteors. The astral tiangou eventually developed its own supernatural associations in China, becoming a sort of dog-shaped astral demon. I cannot cover this topic extensively here, but you will find plenty of information, including a first hand account of a modern celebration tied to these traditions, in Xiaosu Sun’s article in the bibliography.

The earliest Japanese reference to 天狗 occurs in the Nihon Shoki (completed in 720), specifically in the section recording the events from the reign of emperor Jomei (593-641). The reason why I’m using the kanji here is that the reading is not necessarily intended to be tengu in this case; the gloss indicates it is actually to be read as amatsukitsune, “heavenly fox” (I’ll go back to this term later). However, Haruko Wakabayashi states it’s safe to assume that it was used here in the astronomical Chinese meaning. The passage refers to observation of a comet, which reportedly made the sound of thunder as it passed from east to west.

Some other early references to tengu occur in literature of the Heian period (794-1185). In this context, this term seems to refer to nondescript mountain spirits. They were believed to possess people to make them fall ill or to cause disorder. All around it seems they weren’t really meaningfully distinct from any other beings or phenomena which could be subsumed under the label of mononoke (物の怪), and it's not clear how their name came to be applied to them. In the early twentieth century, the folklorist Kunio Yanagita tried to prove these early tengu might have represented people pushed into the mountains by the spread of a centralized Japanese state. However, this theory never took off. Even some of Yanagita’s contemporaries, especially Kumagusu Minakata, were critical of it, and it’s just a weird curiosity today. Similar assumptions were proven correct in the case of tsuchigumo, and might be correct in the case of some oni tales, but these are matters for another time.

The supernatural form of Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitsuya Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

Notably, in the Heian period it was already believed that one can reincarnate as a tengu, though this belief didn’t become quite as well defined as it was in later sources. Probably the oldest story like that states that the monk Shinzei (真済; 800-860) a disciple of Kūkai (774-835), became a tengu and subsequently tormented empress Somedono (染殿后; Fujiwara no Akirakeiko), the wife of emperor Seiwa. In later tradition, emperor Sutoku came to be viewed as the archetypal example of a human who reincarnated as a tengu; it should be noted he was simultaneously viewed as a vengeful spirit (怨霊, onryō), though.

A kite-like tengu, as depicted by Sekien Toriyama (wikimedia commons)

The well known association between tengu and birds is already present in Heian sources too. Today, the bird-like depictions of tengu are known as “karasu tengu”, literally “crow tengu”, and in many modern works, including Touhou, this moniker is taken literally. However, through history the birdlike elements of the tengu were typically those of a bird of prey, not a corvid. As I mentioned, kites were the most common, but for example some depictions of Iizuna Gongen are eagle-like. This convention might have been influenced by garudas, a class of bird-like Buddhist protective figures.

A depiction of a garuda from Besson Zakki (別尊雑記), a Heian period Buddhist iconographic compendium (via Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Descriptions of tengu explicitly mentioning their resemblance to kites are quite common. In Zoku Honchō Ōjōden (続本朝往生伝; “Continuation of the Biographies of Japanese Reborn in a Pure Land Continued”) Ōe no Masafusa (who you might remember from my Ten Desires article) mentions a tengu turning into a kite to spy on a virtuous monk. In the historical epic Taiheiki Sutoku, presented as the ruler of all tengu, is said to have the form of a golden kite. However, in at least some cases tengu are not necessarily birds themselves, but merely use them as mounts. Granted, both traditions could coexist: Hirasan Kojin Reitaku explains that tengu ride kites, but it also describes them as possessing the legs, tail and wings of a bird themselves.

The oldest source to feature a large number of images of bird-like tengu is the already discussed Tengu Zōshi. These include high-ranking monks with beaks, yamabushi or monks with wings and beaks, slightly more bird-like figures portrayed largely without clothing, and finally non-anthropomorphic kites. There are also illustrations of seemingly regular humans labeled as tengu. Haruko Wakabayashi concludes that the use of multiple distinct iconographic types in the same scrolls might reflect belief in a hierarchy of tengu, with the beaked monks representing the upper echelons of the tengu society and the other varieties their servants. The regular kites presumably hold the lowest position. The tengu world thus seems to reflect a contemporary idealized image of Buddhist hierarchy, with lower ranking practitioners, wandering ascetics and laypeople guided by senior monks.

ZUN kept the notion of tengu hierarchy, though the classes listed in the relevant entry in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense are largely his invention, or at least represent pretty extensive reinterpretation (for instance, tengu dressed up as yamabushi aren’t associated with printing in any particular way). While many of these changes work very well with his idea to adapt the traditional role of tengu as peddlers of dubious interpretations of Buddhist doctrine and false miracles with a fresh twist by making them purveyors of misinformation, I will admit I’m not sure where did the idea of wolf tengu come from, as it fits neither this theme nor any genuine tengu background. The wiki insists that’s a reference to the Chinese tiangou, but I’m not buying this.

Iizuna Gongen riding on the back of a celestial fox (wikimedia commons)

I would argue foxes would probably work better than wolves. In some cases due to phonetic similarity a degree of conflation, or at least confusion, could occur between tengu and tenko (天狐), “heavenly foxes”. The fourteenth century treatise Byakuhō Kushō (白寶口抄) states the tenko has the form of a kite, for instance. It’s also why Iizuna Gongen was sometimes referred to as Chira Tenko (智���天狐). The link with foxes was hardly universal, though. For example, it is absent from the tradition centered on Mount Atago, in which in addition to birds, tengu are associated with wild boars. Note that a myth dealing with Iizuna Gongen’s arrival in Japan does indirectly link this location with foxes, but this is basically extending his own connections to other tengu.

While the discussed animal connections are quite important for tengu iconography, I was unable to find any evidence that there was ever a particularly strong belief in mundane animals turning into tengu, as Aya’s bio from Phantasmagoria of Flower View would imply. The only source I am aware of which would state that directly is Atsutane Hirata, one of the most fanatical kokugaku authors, and even he still states that at least some tengu were reincarnated Buddhists. Note that his works are generally not a record of genuine mythology or folklore, but part of an effort to “purify” Japanese culture which directly led to the birth of the “contemporary” form of expansive nationalism. In any case, Hidden Star in Four Seasons and the historical context of information it provides opens the possibilities for much more interesting and unique tengu backstories than just stage 2-worthy beast youkai fare.

To sum up, while individual stories might portray tengu as arriving in Japan from Korea (Tarōbō), China (Zegaibō and his prototype Chira Yōju) or even India (an anonymous tengu in Konjaku Monogatari), these reflect the routes across which Buddhism was transmitted to Japan. The tengu as a distinct supernatural creature had elements which originated abroad, obviously, but ultimately represented a strictly Japanese contribution to Buddhist demonology. At least some Japanese authors were already aware of this in the middle ages, as evidenced by the Shasekishū.

The three meanings of 天狗 - the tiangou, the astral object and the tengu - are explicitly described as distinct from each other in the encyclopedia Jakushōdō Kokkyōshū (寂照堂谷響集) compiled by the monk Unshō (運敞; 1614–1693). The original tiangou is described here as a type of tanuki which eats snakes, but this doesn’t exactly contradict the Chinese description I’ve mentioned before, as 狸, the character referring to wildcat in Chinese, was adopted to represent the name of tanuki in Japanese. The astral tiangou is described as a “tengu star” (天狗星, tengu-sei) which has the form comparable to a dog. Unshō stresses that both of these are distinct from the Japanese tengu, despite their names being written identically. He places the tengu in the entourage of Mara, alongside dakinis and vinayakas (in this context demons representing something like an evil counterpart of Ganesha as a remover of obstacles).

Beyond animals: the long nose tengu and Sarutahiko

A Meiji period depiction of Sarutahiko (wikimedia commons)

A final matter which needs to be addressed here is a theory that tengu imagery is derived from Sarutahiko, which for some reason has been placed in the lead of the tengu article on wikipedia despite being hardly relevant academically. This proposed connection relies on the fact that from the very beginning Sarutahiko was described as long-nosed. In the section of the Nihon Shoki dealing with the “age of the gods”, the oldest text he appears in, it is said that “his nose is 7 feet long”. His other physical characteristics are also exaggerated, to be fair - he is said to be unusually tall, and his eyes are enormous too. All around, this description is presumably meant to make him seem intimidating. Still, the nose is what visual arts tend to highlight, sometimes for comedic purposes.

A long-nosed tengu, as depicted by Hokusai (wikimedia commons)

This characteristic also led to a development of a folkloric connection between Sarutahiko and the one type of tengu depictions I haven’t discussed yet - the long-nosed tengu, commonly called daitengu or “great tengu”. The origin of this iconographic variant remains poorly understood. While by far the most recognizable today, they are a relatively recent artistic convention - the oldest examples only date to the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, and they only became widespread in the Edo period. By then, tengu were present in Japan for some 700 years, and Sarutahiko doesn’t come up in sources describing them (and vice versa).

It also needs to be stressed that while the daitengu still have some birdlike traits, Sarutahiko lacks a connection to birds altogether. Instead, he is associated with monkeys (tengu never are, contrary to an unsourced claim on wikipedia). Historically he could even be identified with Daigyōji (大行事), a deity from Mount Hiei depicted with the head of a macaque.

It’s not impossible that the specific long-nosed type of tengu depictions was based on depictions of Sarutahiko, but it’s equally likely the influence actually went into the opposite direction (most depictions of Sarutahiko are from the Edo period or later, and most shrines dedicated to him are fairly recently established too, even though he was worshiped in one form or another through earlier periods already).

A statuette of a dancer wearing a Raryō-ō costume by Shōmin Unno (Imperial Household Agency; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Bernard Faure notes it’s also not impossible that both Sarutahiko’s iconography and the long-nosed tengu are simply both reflections of something else altogether, and suggests the long-nosed Raryō-ō (羅陵王; sometimes shortened to Ryō-ō, 陵王) masks used in bugaku performances as one possible candidate. Ultimately none of these possibilities can be proven conclusively, though, and it’s best to maintain caution.

ZUN seems to believe there is some truth to the proposal that tengu were derived from Sarutahiko, judging from the fact he referenced this connection multiple times in various ways. The oldest example are Aya’s spell cards in Mountain of Faith. It also comes up in Symposium of Post-Mysticism, where Miko and Byakuren seem to basically treat it as a fact. Aya in one of the short articles from the same book declares that “when it comes to white beard in Gensokyo, we tend to picture Sarutahiko. (...) he is also the god of us tengu”. Putting aside the latter claim, which is bit of a reach when it comes to real beliefs, it’s worth noting that the mention of the white beard is a pretty deep cut. It was actually not a part of Sarutahiko’s original iconography, but rather an addition which developed at the Shirahige Shrine on the shores of Lake Biwa. Originally the local deity, Shirahige Myōjin (白鬚明神), was considered a distinct figure. However, at some point he came to be identified with Sarutahiko, and the names seem to be used interchangeably in medieval and later sources. As a result, the latter received the former’s signature white hair and beard.

While despite the existence of a genuine connection it is a stretch to call Sarutahiko a “god of tengu”, let alone their leader, this does not mean that figures which can be described this way are absent from tradition. In fact, I mentioned a number of them in passing in the previous sections. However, describing them in more detail a topic for another article. Look forward to "Tenma, boss of the tengu". Exploring the "heavenly demon(s)", coming next year!

Bibliography

Yasurō Abe, The Book of “Tengu”: Goblins, Devils and Buddhas in Medieval Japan

Bernard Faure, Protectors and Predators (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 2)

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Michael Daniel Foster, The Book of Yokai. Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore

Sarah Fremerman Aptilon, Goddess Genealogy: Nyoirin Kannon In The Ono Shingon Tradition in: Charles Orzech, Richard Payne & Henrik Sørensen (eds.), Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia

Wilburn N. Hansen, When Tengu Talk. Hirata Atsutane's Ethnography of the Other World

Richard E. Strassberg, A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas

Xiaosu Sun, Liu Qingti's Canine Rebirth and Her Ritual Career as the Heavenly Dog: Recasting Mulian's Mother in Baojuan (Precious Scrolls) Recitation

Haruko Wakayabashi, The Seven Tengu Scrolls. Evil and the Rhetoric of Legitimacy in Medieval Japanese Buddhism

Idem, Monks, Sovereigns, and Malign Spirits: Profiles of Tengu in Medieval Japan

Duncan Ryūken Williams, The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Sōtō Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

day 18: magic build

i realized that i basically don't have mages. i even asked my DM if i ever did any mages in the over ten years i've been playing with him, and he said no. so for a new campaign i'll be playing in someday soon, i committed to making a mage. playing a cleric in DnD 3.5's heyday clearly traumatized me off of magic classes.

i was about to shamefully put down an npc but i got lucky. for an upcoming l5r campaign, a kuni shugenja, seiya! i love the idea of the kuni but they're so niche. thankfully i'll be given monsters to explode with jade strike!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

can anyone tell me more about shugendo/what a shugenja is i've got the wikipedia article pulled up, is there any other connotation other than mountain mystic

2 notes

·

View notes