#She was one of Napoleon’s mistresses. They allegedly had a son

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

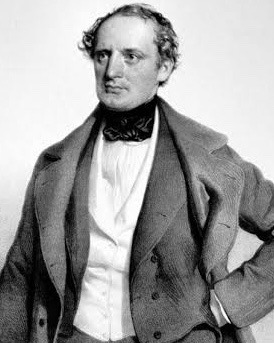

I don't think I've ever heard of this alleged son, so I looked him up and just-

I see why they think he's Napoleon's son. If drawings are to be trusted anyways. But that face 😯

Emilie Kraus von Wolfsberg

She was one of Napoleon’s mistresses. They allegedly had a son, Eugen Megerle von Mühlfeld.

#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#emilie kraus von wolfsberg#She was one of Napoleon’s mistresses. They allegedly had a son#Eugen Megerle von Mühlfeld.#the forehead and the nose specifically look like Napoleon to me#i wonder how many kids he really had??

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bessières and the 600,000+ Franc Question

For @josefavomjaaga

While going over sources and material related to Jean-Baptiste Bessières, there's one thing that keeps twigging my journalist Spidey sense, and I don't like that.

Always, without fail, it's presented as a fait accompli that Bessières blew anywhere between 600,000 to one million francs on his mistress, a Paris opera dancer named Virginie. The fact he had a mistress isn't actually unusual by itself, when compared to the affairs his peers carried on. The exceptions were probably the Davouts and the Lefebvres.

Furthermore, his wife, Marie-Jeanne, discovered the affair after his death when his personal affects were returned to her from the battlefield.

The massive debts the Marshal left behind bankrupted his family, necessitating that Marie-Jeanne into selling their estate, Chateau de Grignon, to cover some of it. Napoleon also paid down some of Bessières' debts and set up a yearly pension for Marie-Jeanne her son. According to some accounts, she struggled financially for the rest of her life.

This is what I don't like about it, and why it doesn't completely pass the sniff test.

I accept that Bessières died flat broke and in debt. In debt to whom, however? Who were his creditors?

When did he meet his mistress? Was that fortune spent over a period of years, or in a fairly short time?

Even as a Marshal of France he had to pay his officers out of his own pocket, and provide his own carriages and some supplies on campaign. If he was flat broke, how did he continue to pay his officers?

Bessières was also bad with money to begin with. He was known to be generous and charitable, to the point where he'd be giving away money to anyone whom he thought was more in need than he was with it. Allegedly, Virginie was in debt herself, and he paid down all of them out of the apparent goodness of his heart.

(This raises even more questions. Was she a gold digger, was she blackmailing him, was he totally besotted with her that he didn't realize what the hell he was doing? Was he just lonely? Did they have genuine feelings for one another? There's a lot of there there, but no real answers.)

My conclusion is, no, Bessières did not spend 600,000 to one million francs on his mistress. Her presence, however, was not helpful to his situation.

He paid down Virginie's debts, however much they were. Being terrible with money, he kept putting himself in a financial hole, and then he kept digging. The upkeep on Chateau de Grignon had to be ridiculous. He still had to pay his officers and his staff. He was probably borrowing and burning through money and racking up the debt. Like that meme goes, "This is fine" while everything's burning down around him. A bit like using a credit card to pay down a credit card, as one might do in the modern parlance.

(His financial problems may have contributed to his increasing depression towards the end of his life as well. Was someone blackmailing him with his debts? Another interesting question that can never be adequately addressed.)

From what I've gathered, he hid all his problems from pretty much everyone. Even Napoleon seemed caught off guard with how bad Bessières' finances were. I argue that the 600,000 to one million francs he owed upon his death were cumulative and not to a single person as the historical narrative wants people to believe.

It seems a small thing to be annoyed with, but there seems to be more than a bit of misogyny to lay all of Bessières' troubles on a single woman as the historical narrative seems to want to do.

Another thing ... if Bessières burned a lot of his recent correspondence towards the end of his life, what exactly was the evidence Marie-Jeanne discovered as proof of the affair. How did she prove it? Did other people know about the affair and kept her in the dark? If so, who was that?

In the novel, "The Battle" by Patrick Rimbaud, a semi-fictionalized account of the Battle of Aspern-Essling, Rimbaud's characterization of Bessières has him wear two gold lockets under his Marshal's uniform. One for Marie-Jeanne, the other for Virginie. I don't know if Rimbaud based that on an actual account, or if it was something he made up. I have a lot of problems with that book though, probably because the translation seems somewhat robotic and not great. It's an interesting idea, however, and maybe worth keeping around as a headcanon.

Did Madame Bessières struggle financially for the rest of her life afterwards? Possibly. I don't have enough information to make a conclusion there, but it's not impossible. She did continue to faithfully visit his tomb for years after his death.

TL;DR Bessières died broke and in debt but it wasn't all because of his mistress. If someone else has something to the contrary, I'd love to read it.

#in my headcanon#the other locket has Murat's portrait in it#now wouldn't that be trippy for people to find#jean baptiste bessières#napoleon's marshals#my old journalism professor would have an apoplexy reading some of these historical accounts#they fail the basic how what when why where test#napoleonic era

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, Can you tell me about the relationship between Joachim Murat and Caroline Bonaparte. Thank you.

I've been wanting to write about their relationship more in-depth for a long time, but I've been putting it off for various reasons, so thanks for giving me an excuse to finally get down to it. :) And... this is probably going to be pretty long. Their relationship was very complicated and often tempestuous (I could use that exact phrasing to describe Murat's relationship with Napoleon, but that's another, possibly even longer post, for another day).

I'm still not entirely certain how I feel about Caroline. She has been greatly maligned over the years, and is, in my opinion, the most misunderstood and demonized of all the Bonaparte siblings aside from Napoleon himself. So much of what we know (or think we know) about her, derives from memoirs that were largely hostile to her; she left none of her own (though her daughter Louise and granddaughter Caroline did). Her remaining published correspondence is sparse, and very one-sided; she apparently was in the habit of destroying most of her received correspondence, including nearly every letter she ever received from her husband, and Murat almost never kept copies of the ones he sent her. So there is this gaping hole in their correspondence where you almost never have Murat's voice. This lost correspondence has been the biggest bane of my existence since I started studying Murat a few years ago.

Their first meeting may have been at Mombello in 1797, but if so, it would've been brief, as Murat only stayed there for a short time before returning to Brescia (and his then-mistress, Madame Ruga). But it seems to have been long enough for Caroline to have become completely infatuated with him, and to confess her feelings for him to Hortense while they were together at Madame Campan's school. She didn't see him again until after the Egyptian campaign, but their courtship seems to have taken off once he was back in Paris. Caroline became bent on marrying him, and Napoleon was opposed to it, only reluctantly signing the marriage contract in January of 1800 and then spitefully not attending the wedding. Apparently it was Josephine who persuaded Napoleon to let the two marry, hoping to finally secure an ally among the Bonaparte siblings. She developed a sort of motherly affection for Caroline early on, but Caroline eventually ended up--whether due to the influence of Joseph and Lucien Bonaparte, or her jealousy of Hortense--firmly in the anti-Beauharnais camp, and Murat and Josephine, who had initially had a good relationship, also became enemies over the next few years.

The early years of their marriage were, from all indications, happy. They had four children in fairly quick succession. They were a very affectionate couple--often publicly so, to the point where a disturbed Madame Campan finally asked Hortense to urge Caroline to show some restraint.

They endured a long period of separation very early in their marriage--the first of many, adding up to several total years spent apart between 1800 and their final parting in May of 1815. Murat was sent to take command of a force in Italy in November 1800 while Caroline was pregnant with their first child; they did not see each other again until May of the following year. There are a couple of letters within Murat's published correspondence that hint that, though he at first attempted to remain faithful to his wife during this interim, he may have given up on the endeavor prior to their reunion. The diplomat Charles Alquier, who befriended Murat in Italy, wrote to him in April 1801, lamenting not being able to spend a few days with him in Florence, teasing that he "would like to witness your gallant successes there and hear you talk about your marital fidelity, without believing it in the slightest." The following month, after the arrival of Caroline, Alquier teases Murat again along these lines, in a postscript that reads "It was about time that Madame Murat arrived in Florence, or your hard-pressed fidelity was about to escape you." He had almost certainly resumed his affair with Madame Ruga during this period.

After the birth of their fourth child, Louise, in March of 1805, Caroline was not pregnant again until 1810 (she would end up miscarrying while Joachim was waging his Sicilian campaign). This has led some historians to conclude that there was a "physical separation" between them, a rift of some sort in their relationship. This may have been the case, but I haven't found much evidence on it either way. There is very little remaining correspondence between the two during this period. Murat was away for long periods due to multiple wars, plus the time he spent in Spain in 1808 prior to taking the throne of Naples that year. Neither of them were faithful to the other. Murat, who was in his early thirties and quite set in his womanizing ways when he married Caroline, doesn't seem to have been either capable of, or interested in, monogamous relations, and at some point this seems to have taken enough of a toll on Caroline that she apparently decided to follow suit. Hortense records an encounter with Caroline from the mid-1800s where Caroline's "sole topic of conversation was the joy of loving and being loved. Her affection for her husband, which once had been so violent, seemed to have diminished. She was now attracted by the charms of a pure liaison."

Over the years Caroline allegedly had affairs with Charles de Flahaut (who was also Hortense's lover), Junot, and Metternich. One of her biographers has theorized that Caroline carried out each of these affairs for the primary purpose of future political leverage (Junot, for instance, was the Governor of Paris at the time). Another theory I've encountered is that she picked these men as a sort of game of one-upsmanship over her female rivals--to show Hortense that she could take Flahaut from her; to show Laure Junot that she could have her husband or her later lover Metternich if she wanted, etc. I... don't really have an opinion on this one way or the other. Caroline was definitely ambitious, and also capable of petty jealousies. What affairs she had (or allegedly had), were of short duration and so far I've come across nothing to convince me that she ever actually fell in love with anyone other than Murat.

Out of the two of them, you may as well flip a coin as to which one was more ambitious. I think, in the end, Joachim managed to overtake Caroline in that department, when he got it into his head to try to become the king of a united Italy while Caroline just wanted to preserve their throne in Naples after Napoleon left Elba. But early in their relationship, Caroline seems to have been the one most obsessed with titles--throwing a fit until Napoleon conceded in granting her and Elisa the title of "Princess". Once Caroline was a princess, she wanted to be a queen, especially after her friend/rival Hortense became the queen of Holland via being married to her brother Louis. Joachim and Caroline were essential to each others' elevation, and they both recognized this; and this recognition, along with their devotion to their children, were the two things that kept them united even when they were temporarily at odds with each other. Once he had obtained the title of "prince" by virtue of being Caroline's husband, Murat became as obsessed as Caroline with the idea of having a throne. Napoleon himself later blamed Caroline for putting grandiose ideas into Murat's head, which then, in his words, "hatched chimeras." He also took it for granted that it had been Caroline who had pushed Murat into defecting from Napoleon and signing the treaty with Austria in 1814, and remarked that Caroline had tremendous influence over her husband.

The irony of Joachim and Caroline Murat achieving the height of their ambition by being given the throne of Naples, is that their reign was probably the worst thing to ever happen to either of them. It wreaked havoc on their marriage for years. It was easily the most miserable period of Murat's life.

For starters, Napoleon essentially poisoned the well, so to speak, by making it clear in the Treaty of Bayonne that Murat was only king by virtue of being married to Caroline, language which Murat found deeply humiliating. The humiliation was further compounded by Caroline being named his direct heir, rather than their son Achille, in order that the throne stay within the Bonaparte family.

So Murat started his reign with a certain amount of resentment and jealousy--and a fear that Caroline would attempt to edge him out of power and dominate him the way that her sisters dominated their husbands, a prospect which was intolerably degrading to a man of Murat's pride. There's no real indication that this was ever Caroline's intention--but Murat was prone to paranoia, worried for years about being superseded by his wife, especially as he increasingly fell out of favor with Napoleon, and Caroline (and her faction at court) steadily gained influence. The first couple years of the reign saw Joachim doing everything he could to keep Caroline on the margins of power. She spent much of her time reading, writing letters, and visiting the ruins of Pompeii.

There was a reconciliation (for a time) between the two in 1810, while they were in Paris together for Napoleon's second wedding. After the wedding, when Murat returned to Naples and began preparing for his Sicilian expedition, Caroline remained in Paris for several more months, during which she served as a sort of intermediary between her husband and Napoleon during a time when the two were at odds and Joachim and Caroline were worried about losing their throne. Her letters to Murat during this time are full of tenderness, consolation, and advice. Examples:

"My dearest, this last separation seems to me even more insupportable than the others. You were so good, so perfect to me in those last moments, that your kindness brought me to tears and still fills me with affection. I confess that when you do justice to my true feelings for you, I am the happiest of women." (11 May 1810)

"You will see one day: we shall be the happiest creatures in the world, and we shall owe it to our children. They will give us back all the love we have for them, and our old age will be adorned with their virtues. See as I do--far into the future." (13 May 1810)

"I'm always anxious about your expedition... Do not expose yourself more than the duty of a general requires, I ask you in grace, imagine that your existence belongs to me and is a possession you cannot dispose of." (16 June 1810)

"We can be happy, but in order for that, we need to be content with what we have, you must calm a little your head, which gets hot so easily, and await, with more patience than you've had until now, the moment where we will be more tranquil and more independent. The happiness of our interior will compensate us for our many pains, and you will find with me, with our children, and from all those who sincerely love us, enjoyments worth all the others." (5 August 1810)

Their relationship was fractured all over again before the year's end. Murat's aggravation with his Sicilian campaign boiled over in a scathing letter to Caroline in which he accused her of being disloyal to him; she received it two days after her miscarriage in September, further adding to her heartbreak. It wasn't a permanent rupture by any means, but it was a deep wound in their relationship that took time to heal. The following year, Murat received reports (almost certainly false) about Caroline having an affair with Daure, Joachim's Minister of the Police, who Joachim soon removed from office, writing to Napoleon that Daure had "aimed at forming a party against me. He did not hesitate to attack me in my tenderest affections," but that "his efforts in that respect were far from obtaining the success that he dared hope for." Murat's relationship with Napoleon likewise grew even worse in 1811, and Caroline went once more to Paris to serve as a go-between/peacemaker.

Leaving for the Russian campaign of 1812, Murat had no choice but to leave Caroline as regent, and he spent most of the campaign worrying about what was happening in Naples in his absence. But she proved a capable ruler, and ruled as regent again during the 1813 campaign, and then again in 1815 during his failed campaign against the Austrians. Joachim seems to have gradually gotten over his fear from early in their reign about Caroline trying to edge him out or dominate him, after she had ample opportunities to do so when he was out of favor with Napoleon throughout 1811 but never did; the latter years of their reign indicate something of a happy equilibrium, and Murat was not above consulting Caroline for her views on complicated issues.

Joachim accompanied her to the ruins of Pompeii on a number of occasions. They both shared a love of art, and patronized a number of artists, including Canova, Ingres, and Antoine-Jean Gros. They danced together regularly at court balls, and went to the theatre often. But above all they preferred spending time together with their children, and their favorite place for this was the terrace of the Palazzo Reale, their personal sanctuary, off-limits to all but the royal family and invited guests, where they would often dine and walk in the gardens (and under the shade of the lemon trees Joachim had had planted for Caroline).

To sum it up, their relationship was extraordinarily complex and they weathered some serious storms which would've broken most relationships beyond repair. The more I read about them, the more I'm impressed by the resilience of their relationship and their determination to keep mending it and making it work, rather than just giving up on it and going the way of Caroline's sister Pauline and her husband Camillo Borghese, who lived mostly separate lives and had minimal interaction. But the Murats had been a love match, and neither of them ever seemed to reach the point of wanting to give up on their relationship entirely. Their relationship--like Caroline herself--has been maligned and badly misinterpreted by earlier historians leaning too heavily on hostile memoirs, and also by those who have been intent on salvaging Murat's reputation by putting all of the blame for his mistakes on Caroline's shoulders.

Thanks for the ask! And sorry if I rambled on too much.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Annotated Bibliography - Diversity and Social Issues 6/7/2020

Title

Thomas, A. (2017). The Hate U Give. New York: Balzer + Bray.

Summary

A sixteen-year-old black girl named Starr feels like she does not fit in at her predominantly white school. She attends a party one night and leaves with her childhood friend, Khalil. On their way home, Khalil gets pulled over and fatally shot by an officer. She tries to testify against the man, but the police refuse to prosecute the officer. Rallies and protests occur for the next few days as Starr talks to her father about how black communities must speak out against systemic racism to break the cycle. Starr gets her case taken up by a grand jury and can speak on television about Khalil, where she talks about how he sold drugs to protect his mother from the local gangs. The grand jury ultimately decides not to indict the officer, so riots break out. As the police break up these riots, the gang leader burns down Starr’s family’s grocery store for revenge. However, all the neighbors agree to testify against the leader as Starr decided to continue in her fight for equality.

Themes

Abuse of Power

Hate

Need for Change

Grades

9 – 12

Title

Lee, H. (1999). To Kill a Mockingbird (40th Anniversary Edition). New York: HarperCollins Publisher.

Summary

Scout and Jem live with their attorney father, Atticus, during the Great Depression. Scout and Jem befriend a new kid named Dill one summer. The following summer, the three kids explore an old house where a man named Boo Radley lives. They are shot at and escape the house, but Jem loses his pants. He finds his pants sewn together the next day hung over the fence. A black man named Tom Robinson is put on trial for raping a white woman. Atticus defends him, even though they live in a very racist town. The Finch family starts to get closer with the black community in town. The town attempts to lynch Tom Robinson, but Atticus and Scout put a stop to that. At the trial, Atticus provides an overwhelming amount of evidence for Tom’s innocence, but the jury finds him guilty anyways. Tom is shot dead trying to escape prison. The father of the woman who was allegedly raped wants revenge on the Finch’s, however. One night he goes to attack Scout and Jem, but Boo Radley saves them by stabbing the man. Scout learns empathy through this series of events and to not use hatred and prejudice in life.

Themes

Justice

Coming of age

Prejudice

Grades

9 – 12

Title

Orwell, G. (1996). Animal Farm. New York: Signet Classics.

Summary

A farm full of animals wants to be free from human oppression and all be equal. They rid of their farmer master and start running their own farm based off the ideals of Animalism. Everything starts fine until two of the leader pigs, Snowball and Napoleon, have a disagreement on whether to build a windmill, in which Napoleon has attack dogs run Snowball off the farm. Now the pigs are in control on the farm and Napoleon forces everyone to build the windmill. Napoleon starts becoming more and more power hungry, having Snowball be the scapegoat for any troubling times and killing all with opposing views. A human farmer ends up destroying the windmill, which causes a war to breakout and one of Napoleon’s most loyal servers to be injured. Napoleon ships him off to a glue factory in exchange for more money. As time progresses, the pigs become more like humans in their nature and their once seven commandments about being equal turn into all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.

Themes

Abuse of Power

Greed

Manipulation

Grades

8 – 10

Title

Walker, A. (1992). The Color Purple. London: Women’s Press.

Summary

Celie, a young black girl living in Georgia, is abused, and raped by her father constantly. Celie gets married to a Mr. [Blank] and lives with him while her sister, Nettie, runs away from home to Celie, and then eventually leaves her too. Mr. [Blank]’s son marries a woman named Sofia, who does not allow herself to be beaten or abused. Mr. [Blank]’s other mistress, Shug, falls ill and meets Celie. Celie starts developing feelings for Shug. Sofia leaves town because she is tired of the attempts of abuse. She returns, however, and ends up beating the mayor who is rude to hear, in which she gets sentenced to be the mayor’s maid for 12 years. Shug and Celie grow closer and eventually find a bunch of letters Nettie has been sending her for years that Mr. [Blank]’s been hiding. Nettie went to Africa with a missionary couple and she learns that both if Celie’s children are still alive and their father was not their real father. Celie and Shug move to Tennessee and then move back to Georgia. Sofia gets released, Mr. [Blank] becomes a better person, and Celie starts a sewing business. In the end, everything turns out better than expected, although Celie claims she never had a youth due to everything that happened to her.

Themes

Faith

Survival

Perseverance

Grades

9 – 12

0 notes

Text

I'll try to answer but I'm at work now, so I can only tell you what I remember from Gotteri's book on the top of my head.

First of all: Please don't be shocked. Seriously. Husbands being unfaithful was the norm, not the exception at the time, and most wives expected a certain measure of cheating. Women were seen as something that nature had created for men. Having sex with men - and having babies in case of a wife - was basically their sole purpose. (Just ask Napoleon.) In addition to that most men (unlike Soult, however) had not married for love. I understand that in the views of the 17th and 18th century, passion had no place in marriage. A marriage was a business deal between two families, period. - While this was starting to change drastically around Napoleon's time, these thoughts continued to live on for quite some time. Napoleon surely still thought along those lines, and so did Josephine. That's why they arranged all those "advantageous" marriages (socially and/or financially) for Lannes, Duroc, Rapp, Ney, etc. A certain sympathy for the spouse was surely expected, but love? Love would come with time, or not. (It surprisingly often did.)

In addition to that: the men we talk about were soldiers. They saw (and did) horrible things every day. Which was especially true in Spain, where most of them felt like they were surrounded by death all day. I assume they sometimes simply needed to feel alive, to feel like somebody cared for them.

After that very long disclaimer 😁: I remember one more incident from Gotteri's book, or possibly two, both from Spain. Madame Soult actually questioned Soult's fidelity in two cases, but the first case he denied. The second he admitted, and apologized. In addition, there is his official mistress in Sevilla from 1810 to 1812.

Were there more? Possible, quite possible. But compared to what we know from Napoleon, Murat, Ney etc, I would guess Soult's ways of cheating were below average.

Edit:

I'm home now, so here is what Gotteri has to say on the matter ("Soult, Maréchal d'empire et homme d'état", p. 393): According to her, the first rumours about her husband courting some other lady reached Louise Soult in Paris while Soult was in Madrid at Joseph's court, i.e., in autumn/winter 1809. Soult vehemently denied them. Considering that courts were a hotbed for gossip, that morals - on the surface - were so strict that it was easy to make a mistake that could be taken the wrong way, that Joseph surrounded himself with beautiful women, and that this happened shortly after the "roi Nicolas" incident, with people most likely eager to malign even further the marshal who allegedly had tried to betray Napoleon - considering all that, I would give Soult the benefit of the doubt here.

The second time, when Parisian gossip informs Louise about her husband's "libertinage", is in February 1811. Soult is on campaign, besieging the fortress of Badajoz as a distraction to help Masséna, who is facing Wellington in Portugal. As Gotteri writes, Soult evades this accusation, invoking the harshness of his life. And Louise, wise spouse that she is, lets it be. - Theoretically, the lady this was about might already be the same Maria de La Paz Baylen y González who we all know about (the mother of his illegitimate son).

today yaggy dropped a nuclear bomb on me by revealing to me that supposedly Soult had multiple mistresses??? not just the Spanish woman??? well who was/were his other mistress(es) then???? I'm so confused this was the first time I'd heard of this

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

German language article about the life of one of Napoleon’s widely believed to be illegitimate children, Eugen Megerle von Mühlfeld.

This article from the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Bundesministerium für Inneres) of Austria was written to commemorate to 200 year anniversary of the birth of Mühlfeld. He was a lawyer and professor, and he was also a progressive politician who worked in the Austrian government during the 19th century.

Some interesting fun facts from the article: He was actually born only one day before one of Napoleon’s other sons, Alexandre Walewski!! Mühlfeld’s mother was a woman who was born in modern day Slovenia named Emilie Kraus von Wolfsberg. She was called the Dog Countess, which it literally says on her plaque at the place she is buried. She was called this because she spent all her money on animals, which caused her to become destitute. She ended up giving her son over to be adopted. So that’s how he ended up being raised by the Mühlfeld’s, and it seems like he had a pretty good life! At least I hope he did!

Interestingly, people who had met Napoleon actually recognized Mühlfeld’s resemblance to him, and rumors spread in Vienna that he was Napoleon’s illegitimate son. The rumor spread all the way to Paris, and the French Prime Minister traveled to Vienna because he wanted to meet Napoleon’s son. I wonder if he knew Napoleon had other sons in France lol

More about his career: The article says he was one of the best and most highly respected lawyers in Austria. As a politician, he was progressive and was noted for advocating for the separation of church and state, reestablishment of the jury, and abolishing the death penalty. He was also the dean of the law faculty at the University of Vienna. He was the founder of the bar association, and was its first president. In 1842, he was the co-creator of something called “Juridisch-politischen Le-severeins" which was a reading association and platform for progressive-minded intellectuals and was very influential during the 1848 Revolution. The year he died, 1868, laws were passed on his initiative which allowed people to choose their own religion when they turned 14.

He was described by Dr. Ignaz Kuranda like this: “Im Leben kein Pedant, im Lieben Feuerbrand, im Denken ein Gigant, im Reden ein Foliant!" which roughly and loosely translates to “In life no pedant, in love firebrand, in thinking a giant, in speaking a tome!”

Just to note: It’s never been 100% confirmed that he was definitely Napoleon’s son, but his natural mother was said to be Napoleon’s mistress. They met in 1805, and during the time they were together, she allegedly disguised herself as a boy. Their affair is also commemorated on the plaque at her gravesite. Here is a painting Napoleon commissioned of her (by Johann Baptist von Lampi):

Link to the article:

Additionally, here is a link to his Wikipedia page, which is also in German:

https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugen_Megerle_von_Mühlfeld

#Eugen Megerle von Mühlfeld#Mühlfeld#Napoleon’s son#Napoleon’s children#Napoleon#Napoleon’s sons#Emilie Kraus von Wolfsberg#Emilie Kraus#article#ref#article link#napoleonic era#napoleonic#19th century#first french empire#French empire#Austria#Habsburg#history#text post#Johann Baptist von Lampi#1800s#austria hungary#long post#German#german language#1848#revolution#revolutions#1848 revolutions

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emilie Kraus von Wolfsberg

She was one of Napoleon’s mistresses. They allegedly had a son, Eugen Megerle von Mühlfeld.

#Napoleon’s mistress#1800s#history#napoleonic#napoleonic era#19th century#1800s fashion#19th century fashion

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

Male historians/biographers bought into the Eve/Mary trope when evaluating the spouses--and mistresses--of male historical figures. They seem to judge the woman/women through the lens of whether they were “worthy” of the hero in question, if they sufficiently worshipped him and served him in all respects, and conformed to the innate prejudices of these male writers. And above all, the double standard has prevailed. Josephine was allegedly flagrantly unfaithful, for which she has been condemned, at the same time Napoleon was more unfaithful while that was not only expected but condones--it’s what Great Men did. Marie-Louise has been roundly condemned because she was weak, disloyal, foreign, refused to accompany her husband into exile, and kept his son from him. Some of this same misogynist nonsense and blindness has also been heaped on Emma Hamilton, for example, for the same reasons. I ran headlong into this same trope when I was writing my biography on Lannes--all his previous biographers were men, and every single one of them characterized the marshal’s first wife as a trollop [I adore that word!] and his second as a bloody saint. They were all completely wrong on all counts, but they refused to see anything that would besmirch the character of their hero. Needless to say, I had a wonderful time debunking a lot of myths. In sum, male historians are apparently genetically incapable of much if any discernment when researching and writing about women in this particular context. So, ignore them.

what’s with napoleonic historians and hating josephine

They are... mostly male?

Don’t worry, they hate poor Marie Louise even more. While I confess she’s not my favourite person either (Marie Louise, not Josephine, I adore Josie with all her many flaws) the amount of hate is... mah, crazy.

Our old friend Castelot wrote once she "made him want to vomit". Such an unbiased comment.

90 notes

·

View notes