#Shanhai Jing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Qique, the 246th Known One.

"There is a bird here on North Shouting Mountain whose form ressembles a chicken but with a white head, rat's feet, and tiger's claws. It is called a Qique. It, too, is a man eater." - Shanhai jing, Guideways Through Mountains and Seas.

first design (no chimken ??)

Qique means Qi-magpie, and somehow i forgot about the chicken while designing it. I still had the original illustration in mind, and i misinterpreted the 2 legs as 2 sets of front and back legs. At the end it looked too much like some kind of griffin and the tail was wrong.. so i chose to just stick to the text with no magpie. I'm still not super satisfied with the design, maybe the right one stands between these two takes

#China#Qique#shanhai jing#Guideways Through Mountains and Seas#chimera#monster#bestiary#creature design#ink#folklore#984#octem 123#aer 4#the Known Ones

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is it true that xiwangmu is described as a tiger? or like a wild animal or Yaoguai? Can you please talk more about her?

Her earliest depiction in the Book of Mountains and Seas is a half-human, half-beast goddess, yes.

In 西山经, she was said to be "human-like", but has the tail of a leopard, teeth of a tiger, and is good at roaring. She is also in charge of natural disasters, plagues, and punishments.

Another passage from 大荒西经 mentioned a god with human face and the body of a tiger on Mt. Kunlun...next to the "QMoW with leopard tail and tiger teeth".

Here are some depictions from (much) later illustrated versions of the Book of Mountains and Seas:

However, the Book of Mountains and Seas is a collection of pre-Qin myths and legends, and by the Han dynasty, QMoW had evolved into a fully human goddess, able to grant immortality via elixirs, and interacted with human emperors like King Mu of Zhou + Han Wudi in stories.

Here is her depiction on Han dynasty grave reliefs. Though QMoW was accompanied by a dragon and a tiger in those artworks, she herself looked like an aristocratic human woman.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been researching turtle-type fantastical beasts of ancient China for my article on the Tulu Xuanwu in MDZS and its symbol as a foreshadowing of Wei Ying's path and ending in his first life.

This was one of the possible candidates. I figure I might as well scan the art and translate the text from the Shanhai Jing and post this as a fandom resource.

Xuan Gui 旋龜 (lit. the Spinning Turtle)- Shanhai Jing / Classics of Mountains and Seas (circa 4th century BCE)

Illustration by Shan Zhe, published in Guan Shan Hai, the compiled and edited version of the OG Shanhai Jing, by Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House.

My Translation:

Text from the 4th century BCE Shanhai Jing: From Nuyang mountain comes a strange stream. This stream flows to the East and pours into the Xianyi River. In this stream live many black turtles. These creatures have the body of a turtle, the tail of a Hui snake (*: a type of ancient, fantastical, poisonous snake), and the head of a bird.

Its name is Xuan Gui. Its cries are like chopping wood. Wear it on your body to cure or prevent deafness. It can be used to treat foot calluses.

Explanation text from modern anthropologists: Other than Xuan Gui, the Shanhai Jing also mentions other fantastical turtles, such as the three-legged turtle, the Liang Gui, Gui, etc... Turtles are sacred in ancient beliefs. They are seen as the spiritual bridge between heaven and earth, the divine and the mortal. During the Yin Shang Dynasty (a semi-mythical dynasty over 3500 years ago, from 1766 BCE - 1122 BCE. All historical records of this dynasty are lost, and it's only mentioned in texts of a more fantastical nature), turtle shells were used for divination. During the Zhou Dynasty (Wu Zetian's Dynasty, 690 - 705), there existed court officials whose task was to divine the future using turtle shells.

In the Book of Rites (禮記 Lǐ Jì, one of the five founding classical texts of Ancient China, 213 BCE), the turtle is counted among the Four Sacred, alongside unicorn, phoenix, and dragon.

The ancients held the turtle in such high regard due to several reasons. One, its long life span (in ancient times, creatures with long life spans are believed to have a degree of sentience and the potential for the spark of the divine). Two: because the shape of the turtle symbolizes heaven and earth, and the four cardinals). In summary, the turtle symbolizes the ideal values of ancient people: long life, sedentariness, high esteem, and purity of heart.

-- End Translation --

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

#theClassicofMountainsandSeas, also known as Shanhai jing (Chinese: #山海经),[1] formerly romanized as the #ShanhaiChing,[2] is a Chinese classic text and a compilation of mythic geography[3][4] and beasts. Early versions of the text may have existed since the 4th

0 notes

Text

"So in the end, God issued a command allowing Yü to spread out the self replacing soil so as to quell the floods in the Nine Provinces."

Quote randomly selected from page 81 of Anne Birrell's nonfiction book Chinese Mythology: An Introduction

Additional notes: This quote is in and of itself part of a block quote whose citation is given as (Shan Hai Ching, Hai nei ching, SPPY 18.8b-9a). Shan Hai Ching is also romanized as Shanhai jing and translates to Classic of Mountains and Seas.

Quote was selected at random from a book chosen at random from my local library.

#Books#History#Mythology#Chinese Mythology#Chinese Mythology: An Introduction#Yu the Great#The Great Flood of Gun-Yu#Anne Birrell#Shanhai jing#Classic of Mountains and Seas

1 note

·

View note

Text

*Deep Sigh*

The general outline of Gonggong's myth is correct, but it's also very much a "pop version", heavily influenced by modern interpretations and completely unsourced.

One of the earliest mentions of Gonggong was in the Book of Mountains and Seas. Before that, Shang Shu also briefly alluded to Gonggong as a subordinate of Sage King Yao, who was exiled together with 3 other criminals.

In the Book of Mountains and Seas, he was the son of Zhurong(海内经), Xiangliu the Nine-headed Serpent was his minister(海外北经 + 大荒北经), and Yu the Great was said to have attacked "the Kingdom of Gonggong" (海内经).

That's it——the "breaking of the sky pillar" myth hadn't formed yet in the Warring States Era, or if it was, it wasn't mentioned.

The source that did mention it was Huainanzi: here, Gonggong went and headbutted Mt. Buzhou the sky pillar after losing a battle with Zhuanxu, the ruling Heavenly Emperor associated with the North.

(Not the JE; JE wouldn't be a thing for like, 800 years, Huainanzi being a Han dynasty work and all!)

(The same version of the story could also be found in Liezi.)

Huainanzi then proceeded to give some conflicting accounts, including:

1)Gonggong being one of the four evildoers exiled by Yao

2)Gonggong was killed by Zhuanxu for his transgressions

3)Gonggong returning during the time of Shun to cause floods again, thus, Yu the Great being commanded to conquer the great flood

Just for reference purposes: another Han dynasty (debated) work, Shenyi Jing, described Gonggong as having red hair, the face and limbs of a human, and the body of a snake.

If you are going by this source, he certainly has serpentine features——but he's not a black dragon!

The only source that mentioned a black dragon is Huainanzi, in the section about Nvwa patching the sky, and that was just one of the many random beasts running around after the sky pillar's collapse...

Now, the earliest source I'm aware of that replaced Zhuanxu with Zhurong was the Tang dynasty 三皇本纪, written by Sima Zhen as an addendum to Shiji.

This version became quite popular and well-known, probably because the symbolism of Water vs. Fire was a lot more appealing.

Oh, and Zhurong did not ride a tiger. Book of Mountains and Seas actually described him in 海外南经, as an entity with human face and beastly body, who rode on two dragons.

...The idea of Gonggong as a rebel figure, unhappy with heavenly hierarchy, is very much a modern reinterpretation, though, and one that's in the same vein as Havoc in Heaven's remaking into a revolutionary narrative.

(And the part where he rebelled because he was "growing sick of trival errands and paper work"...um, citation needed?)

-In almost all the ancient sources, Gonggong was depicted as a wrongfully rebellious vassal or a destructive god——much like the flood he was associated with and embodied.

491 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey yeri!! i hope your week gets better!! is there anything have you've read or watched recently??

hi again anon 💕! it's been over a month, how are you doing? recently i've just been reading things for school (μ_μ) but i've been working through late victorian holocausts by mike davis in my own time! i've also started the jakarta method by vincent bevins but i've been so busy i've hardly made a dent in it (TAT) and last month i picked up what’s wrong with a snake that just wants to cultivate and transform? by chengyu but i've been waiting for a free weekend so i can binge it properly HAHAHA

as for things i've been watching lately, i've been watching shogun, dungeon meshi, and worst of evil! frieren and apothecary diaries recently finished so i'm looking for more background media to turn on while i work asfjsj if anyone has recommendations i'd looooove to hear them!

#anon#there's so many books i want to read#salt houses is at the top of my tbr#and i'm still working on crossreferencing the shanhai jing#with strassberg's edition FJSDJSJ#the semester can't end fast enoughhhh#i can't wait to be back in korea ( ̄ω ̄)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yu the Great and Sun Wukong's Staff

This is my answer to the following reddit question:

Did the Ruyi Jingu Bang, as a tool used by Da Yu, exist before the novel?

Monkey's golden-hoop iron staff can be traced to the khakkhara and iron rod respectively used by his precursor in the 13th-century JTTW. The story doesn't mention anything about Yu the Great. The demi-god's connection to the staff is, as far as I know, unique to the standard 1592 edition of JTTW.

This association probably came about in a couple of ways. For example, there is a Chinese graphic similarity (and possible totemic connection) between Yu and a specific kind of monkey:

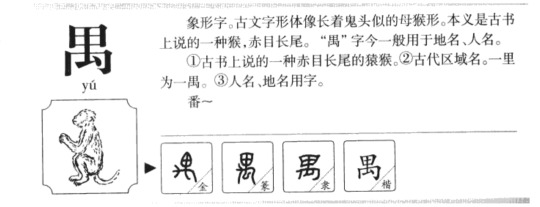

The generic Chinese primate names have identical pronunciations or spellings to those of the earliest Chinese emperors. For instance, the character 猱 (Nao) is considered as the ancestral name of the royal family of Shang dynasty (商朝 ca. 1600–1050 BCE) (Cao, 1997; Wang, 2001). This word is used to denote a primate species that is good at climbing. Similarly, the character 禺 (Yu) represents a long-tailed monkey. This word is the same as the character 禹 (Yu), a legendary emperor well known for his brilliance in regulating floodwater (Huang, 2011). This association between primates and the earliest emperors indicates a possible totemic status for primates (Niu, Ang, Xiao, et al., 2002, p. 91).

(The aforementioned Yu (禺) monkey was apparently well-known, for it is referenced several times in the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shanhai jing, 山海經, c. 4th-century to 1st-century BCE), a popular Chinese bestiary, in order to indicate the shape and size of certain primate-like animals (Strassberg, 2002, pp. 83, 84, 91, 99, 104, 122, 123).)

Also, Yu is known for imprisoning Wuzhiqi (無支奇 / 巫支祇), a monkey flood demon, beneath a mountain in Tang and Song-era folklore. This likely influenced Sun Wukong's punishment under Five Elements Mountain.

Therefore, all of this probably led to the author-compiler of the 1592 JTTW associating Monkey's staff with Yu the Great and his efforts to end the world flood.

Sources:

Niu, K., Ang, A., Xiao, Z. et al. (2002). Is Yuan in China’s Three Gorges a Gibbon or a Langur? International Journal of Primatology, 43, 822–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-022-00302-1

Strassberg, R. (2002). A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas. University of California Press.

#Da Yu#Yu the Great#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#Wuzhiqi#flood demon#monkey#Shanhaijing#Classic of Mountains and Seas#Magic Staff#Ruyi jingu bang#Gold-banded staff#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Qilin (Chinese Unicorn)

The qilin (麒麟, or simply lin 麟) is a Chinese mythical creature, frequently translated as "Chinese unicorn." While this term may suggest a one-horned creature, the qilin is often depicted with two horns. However, like the Western unicorn, the qilin was considered pure and benevolent. A rarely seen auspicious omen, the qilin heralds virtue, future greatness, and just leadership.

Throughout history, the qilin can be found in Chinese literature, art, and accounts of day-to-day life. As one of the Four Auspicious Beasts – alongside the dragon, phoenix, and tortoise – the qilin also embodies prosperity and longevity and has a heavenly status. References to the qilin date back to ancient Chinese texts, where this revered creature is regarded as a sign of good fortune and an indicator of a virtuous ruler. Its association with the philosopher Confucius (l. c. 551 to c. 479 BCE) underscores its significance as an auspicious symbol. Qilin imagery was favoured across various Chinese dynasties, and its popularity extends across other Asian countries, including Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

The Qilin in Classical Texts

In the classic The Book of Rites (also known as the Liji, date uncertain), the qilin is listed as one of the four intelligent creatures along with the phoenix, dragon, and tortoise, often referred to as the Four Auspicious Beasts. Each of these divine creatures symbolizes different virtues considered essential for successful and harmonious coexistence. Broadly, the dragon symbolizes power and strength, the phoenix renewal and grace, the tortoise longevity and stability, and the qilin prosperity and righteousness. Together, these beings convey a collective message of good fortune and balance.

The Classic of Mountains and Seas (the Shanhai jing, 4th century BCE), a proposed mythological geography of foreign lands, mentions several one-horned beasts, but none are specifically identified as the qilin. The earliest known reference to the qilin in ancient texts can be traced back to the Western Zhou period (1045-771 BCE), which is the first half of the Zhou dynasty, the longest-lasting dynasty in Chinese history. The qilin also appears in the Shijing, also called The Book of Odes or Classic of Poetry, said to have been compiled by Confucius in the 4th century BCE, making it the oldest extant poetry collection in China. The Shijing contains just over 300 poems and songs, with some thought to be written between c. 1000 to c. 500 BCE. The piece in question, "The Feet of the Lin", appears at the end of the section that captures the voices of the common people. From Bernhard Kalgren's translation, The Book of Odes (1950):

The feet of the lin! You majestic sons of the prince! Oh, the lin!

The forehead of the lin! You majestic kinsmen of the prince! Oh, the lin!

The horns of the lin! You majestic clansmen of the prince! Oh, the lin!

Here, lin refers to the qilin, and its defining physical features are likened to regal offspring and relations. Karlgren calls this "a simple hunting song, and an exclamation of joy" (7) and suggests it was originally about a real but rare animal, such as a type of deer, which became a fantastical legend later. In James Legge's translation of the same poem, he notes that the qilin had a deer's body, ox's tail, horse's hooves, a single horn, and fish scales. The qilin's feet are not used to harm any living thing, even grass; it never butts with its head, and does not attack with its horn. As a popular and freely available translation, these notes are frequently cited and show the qilin as supremely peaceful and benevolent by choice.

In the 5th century BCE, we find the qilin, again mentioned as the lin, in The Spring and Autumn Annals, a historical record of events occurring in the state of Lu. This chronicle records that a lin was captured in the 14th year of Lord Ai's rule, 481 BCE. Later scholars analyzed and attributed great significance to this event, as Confucius himself, the compiler of The Spring and Autumn Annals, might have done.

From James Legge's translation of The Chinese Classics, volume V, 1872, page 832, (translator's square brackets):

In the hunters in the west captured a lin.

Continue reading...

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

when i pitch my book it's not gonna be weak shit like "pacific rim x the handmaid's tale meets imperial chinese history" it's gonna be shanhai jing x xiyouji

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are dedicated to the promotion of Chinese mythology in the Shanhaijing(The Classic of Mountains and Seas). We are looking for cultural and creative products about the Shanhaijing for everyone. You can also contact us ([email protected])for a personalized order.

0 notes

Text

Since Twitter bit the bucket it’s time to begin my rebirth!!! And what better way to do that than with a character of mine that represents dawning a new persona, welcome, Shanhai Jing!🦅

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

So You Want to Read More about Chinese Mythos: a rough list of primary sources

"How/Where can I learn more about Chinese mythology?" is a question I saw a lot on other sites, back when I was venturing outside of Shenmo novel booksphere and into IRL folk religions + general mythos, but had rarely found satisfying answers.

As such, this is my attempt at writing something past me will find useful.

(Built into it is the assumption that you can read Chinese, which I only realized after writing the post. I try to amend for it by adding links to existing translations, as well as links to digitalized Chinese versions when there doesn't seem to be one.)

The thing about all mythologies and legends is that they are 1) complicated, and 2) are products of their times. As such, it is very important to specify the "when" and "wheres" and "what are you looking for" when answering a question as broad as this.

-Do you want one or more "books with an overarching story"?

In that case, Journey to the West and Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen Yanyi) serve as good starting points, made more accessible for general readers by the fact that they both had English translations——Anthony C. Yu's JTTW translation is very good, Gu Zhizhong's FSYY one, not so much.

Crucially, they are both Ming vernacular novels. Though they are fictional works that are not on the same level of "seriousness" as actual religious scriptures, these books still took inspiration from the popular religion of their times, at a point where the blending of the Three Teachings (Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism) had become truly mainstream.

And for FSYY specifically, the book had a huge influence on subsequent popular worship because of its "pantheon-building" aspect, to the point of some Daoists actually putting characters from the novel into their temples.

(Vernacular novels + operas being a medium for the spread of popular worship and popular fictional characters eventually being worshipped IRL is a thing in Ming-Qing China. Meir Shahar has a paper that goes into detail about the relationship between the two.)

After that, if you want to read other Shenmo novels, works that are much less well-written but may be more reflective of Ming folk religions at the time, check out Journey to the North/South/East (named as such bc of what basically amounted to a Ming print house marketing strategy) too.

-Do you want to know about the priestly Daoist side of things, the "how the deities are organized and worshipped in a somewhat more formal setting" vs "how the stories are told"?

Though I won't recommend diving straight into the entire Daozang or Yunji Qiqian or some other books compiled in the Daoist text collections, I can think of a few "list of gods/immortals" type works, like Liexian Zhuan and Zhenling Weiye Tu.

Also, though it is much closer to the folk religion side than the organized Daoist side, the Yuan-Ming era Grand Compendium of the Three Religions' Deities, aka Sanjiao Soushen Daquan, is invaluable in understanding the origins and evolutions of certain popular deities.

(A quirk of historical Daoist scriptures is that they often come up with giant lists of gods that have never appeared in other prior texts, or enjoy any actual worship in temples.)

(The "organized/folk" divide is itself a dubious one, seeing how both state religion and "priestly" Daoism had channels to incorporate popular deities and practices into their systems. But if you are just looking at written materials, I feel like there is still a noticeable difference.)

Lastly, if you want to know more about Daoist immortal-hood and how to attain it: Ge Hong's Baopuzi (N & S. dynasty) and Zhonglv Chuandao Ji (late Tang/Five Dynasties) are both texts about external and internal alchemy with English translations.

-Do you want something older, more ancient, from Warring States and Qin-Han Era China?

Classics of Mountains and Seas, aka Shanhai Jing, is the way to go. It also reads like a bestiary-slash-fantastical cookbook, full of strange beasts, plants, kingdoms of unusual humanoids, and the occasional half-man, half-beast gods.

A later work, the Han-dynasty Huai Nan Zi, is an even denser read, being a collection of essays, but it's also where a lot of ancient legends like "Nvwa patches the sky" and "Chang'e steals the elixir of immortality" can be first found in bits and pieces.

Shenyi Jing might or might not be a Northern-Southern dynasties work masquerading as a Han one. It was written in a style that emulated the Classics of Mountains and Seas, and had some neat fantastic beasts and additional descriptions of gods/beasts mentioned in the previous 2 works.

-Do you have too much time on your hands, a willingness to get through lot of classical Chinese, and an obsession over yaoguais and ghosts?

Then it's time to flip open the encyclopedic folklore compendiums——Soushen Ji (N/S dynasty), You Yang Za Zu (Tang), Taiping Guangji (early Song), Yijian Zhi (Southern Song)...

Okay, to be honest, you probably can't read all of them from start to finish. I can't either. These aren't purely folklore compendiums, but giant encyclopedias collecting matters ranging from history and biography to medicine and geography, with specific sections on yaoguais, ghosts and "strange things that happened to someone".

As such, I recommend you only check the relevant sections and use the Full Text Search function well.

Pu Songling's Strange Tales from a Chinese Studios, aka Liaozhai Zhiyi, is in a similar vein, but a lot more entertaining and readable. Together with Yuewei Caotang Biji and Zi Buyu, they formed the "Big Three" of Qing dynasty folktale compendiums, all of which featured a lot of stories about fox spirits and ghosts.

Lastly...

The Yuan-Ming Zajus (a sort of folk opera) get an honorable mention. Apart from JTTW Zaju, an early, pre-novel version of the story that has very different characterization of SWK, there are also a few plays centered around Erlang (specifically, Zhao Erlang) and Nezha, such as "Erlang Drunkenly Shot the Demon-locking Mirror". Sadly, none of these had an English translation.

Because of the fragmented nature of Chinese mythos, you can always find some tidbits scattered inside history books like Zuo Zhuan or poetry collections like Qu Yuan's Chuci. Since they aren't really about mythology overall and are too numerous to cite, I do not include them in this post, but if you wanna go down even deeper in this already gigantic rabbit hole, it's a good thing to keep in mind.

#chinese mythology#chinese folklore#resources#mythology and folklore#journey to the west#investiture of the gods

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Qiongqi Beast, one among the four legendary primordial beasts of China - Namesake of Qiongqi Path (MDZS) - The foreshadow of Wei Ying’s death. - Illustration by Shan Zhe, published in Guan Shan Hai, the compiled and edited version of the OG Shanhai Jing, by Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House.

Recently I got my hand on Shanhai Jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas), the 2200+ years old classical text on Chinese fantastical flora, fauna, beasts, strange people, and gods. Qiongqi is counted among Shanhai Jing menagerie. Below is my translation of the description of Qiongi Beast directly from Hunan’s Shanhai Jing.

窮奇 (Qiongqi)

- Text directly from the 2200+ year old Shanhai Jing: Qiongqi has the shape of a tiger with wings. It eats human, starting from the head. Those who it eats all have their hair unbound. It lives North of the Peach Dog’s den.

- Modern Anthropologist Notes (by Hunan Publishing House’s editing team):

1/ Qiongqi beast has the shape of a winged tiger. It is a vicious man eater. When it eats, it starts from the head. Those who are eaten by it all have their hair unbound.

2/ Qiongqi also appears on Xishan Jing (Classic of Western Mountains), where it is described as ox-like, with porcupine quills, and barks like a dog. This description is vastly different from the one in Shanhai Jing.

3/ Qiongqi is mentioned in many ancient texts. In the Records of the Five Emperors, Qiongqi is said to be the hideous, good-for-nothing son of Shaohao (son of the Yellow Emperor, one of the three legendary ancient emperors of China) (*). It is said to destroy those who are loyal and faithful and fawn over those who are deceitful and perverse.

(*: In other words, Records of the Five Emperor claims that Qiongqi was a human prince who fell to beasthood out of wickedness)

4/ Both the Records of the Five Emperor and Shenyi Jing (Classic of Strange Gods) agree that Qionqi is an evil beast that has completely reversed concept of good and evil. Shenyi Jing notes that Qionqi eats those who are good, honest, and loyal and will aid wicked liars.

- End Translation -

.....................................................

Symbol of Qiongqi in MDZS:

If you have read MDZS, then there’s probably no need to repeat the name Qiongqi Path. The symbolism is readily apparent.

Qiongqi Path is the site where Wei Ying was repeatedly forced onto a death path by Jin schemes. The first time was when he rescued the Wen remnants (who were forced to move from a neutral territory Ganquan 甘泉 to Qiongqi Path, controlled by Jin after the Sunshot campaign, as per the novel). And the second time was during Jin Zixun’s failed ambush.

In other words, Wei Ying’s death was foreshadowed in the name of the location itself. Qiongqi beast destroys and eats the good, honest, loyal person with hair unbound. It eats from the head down, symbolizing the loss of agency and ability to call for help or argue the person’s own case. Wei Ying was symbolically eaten by Qiongqi.

If you want to look further, there is also correlation between Qiongqi’s origin as a human prince associated with the color yellow who fell to beasthood out of wickedness and the Jin’s origin as a cultivator House founded by royalty and whose primary color is yellow.

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

[review]山海高中

Title: 山海高中 Shanhai High School

Author: 语笑阑珊

Length: 103 chapters + 9 extras

Rating: G

Tag: Urban fantasy/mythology, slice of life, comedy

Summary [taken from novel updates]:

Lin Jing was pretty much your average good student, as he was serious, diligent, and polite.

After his second-grade high school transferred, he was forcibly recruited to become a minion of the troubled student, who had ranked first from last in the grade.

In this regard, Lin Jing had confusedly raised a question, “Why?”

Ji XingLing, who hung a school uniform over his shoulders, sloppily leaned against the wall, as the golden sunlight fell on the tip of his hair. “Can’t help it; blame yourself for being a careless little monster.”

Lin Jing, “?”

It’s over; this boy must have a loose screw.

On the day of his eighteenth birthday, Young Master Ji who had styled all over his hair with pomade, was blocking people at the door, and while felt himself as a domineering President, “Are you free tomorrow?”

Lin Jing was panicky, “Ji XingLing! Ji XingLing! Your Qilin tail is showing again!”

It is a casual school life fantasy and Qilin’s attack.

Novel| Novel [translated]| Manhua

Comments **contains spoilers**:

I don’t have much to say about this novel other than this is a light read, filled with fluffy interactions between the main CP and the people around them. Some highlights of the novel:

The MC (Lin Jing) is extremely studious and refuses to date ML (Xing Ling) until he scores above 500 in exams lol. A large part of the novel is just the ML working hard to catch up on his scores and negotiating with the MC about the threshold of his ‘passing score’ for dating.

Unlike a lot of slice-of-life stories with mythological creatures, the characters didn’t know each other’s mythological identity. Cue cute scenes where the characters are surprised to learn each other’s identity: e.g. MC’s mom doesn’t know how her kid is a rare plant-based mythological creature since she isn’t one. It’s only later that they found out the dad, who doesn’t believe in supernatural/fantasy stories, is actually a plant mythological creature himself.

The ML’s family is wholesome: his father is a kylin who likes to show-off his son by turning Xing Ling into his kylin form and carrying him up into the skies to show off in front of other mythological creatures. His mother is a 9-tailed fox who encourages the MC and ML’s relationship because she wants her son’s grades to improve lol.

Overall, the writing style is funny and full of ‘tucao’ (i.e. roasting; to make fun of something)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mumpung masih hangat, ikutan @arabella-77 mengupas terjemahan date Qixi yang salah arah. Kali ini, yang jadi masalah adalah Shaw yang tanpa sengaja jadi teman Hercules di Gunung Artemis 😁

Entah sadar atau tidak, Elex menuliskan Shaw sebagai a beast that dwelled on Artemis Mountain. Padahal, sesungguhnya, tentu saja di teks Mandarinnya tidak disebutkan tentang Gunung Artemis.

Saya mencoba menerjemahkan teks aslinya dibantu Arabella, hasilnya adalah begini:

Aslinya, Shaw mengambil wujud Zheng (狰), makhluk mitologi Tiongkok dari kisah 《山海经》Shanhai Jing (Kisah Klasik Gunung dan Samudra). Jika dijabarkan, makhluk aslinya berupa macan tutul merah dengan satu tanduk dan lima ekor.

Jika ditilik lagi, bagian teks asli ditegaskan lagi di bagian terakhir Perfect Day, di mana Shaw menghanyutkan lampion sungai raksasa berbentuk kapal. Di kapal itu ada 2 figur yang mirip Shaw dan MC.

Apakah ini cocok untuk Shaw? 🤭

7 notes

·

View notes