#Sergei Yutkevich

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

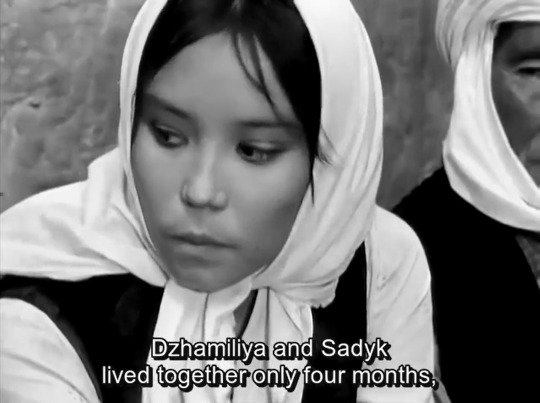

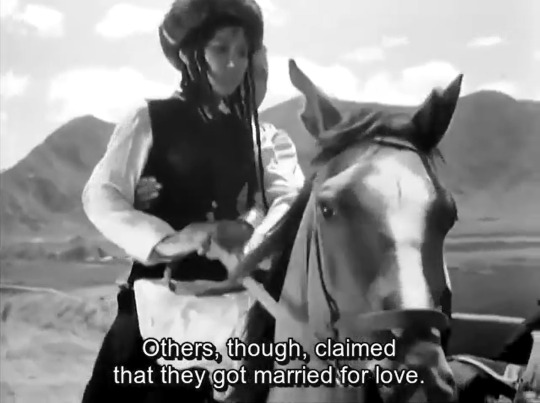

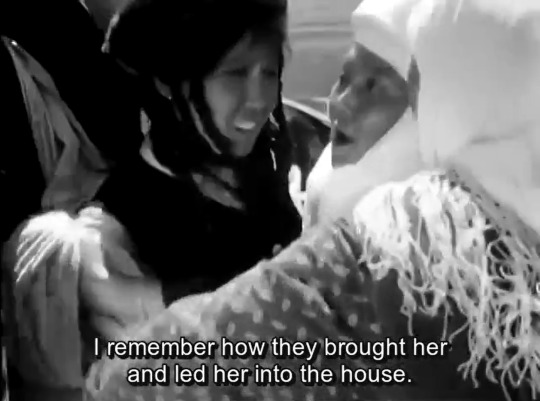

Movie: Jamilya (Джамиля)

Year: 1969

Location: Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Union

Directors: Irina Poplavskaya and Sergei Yutkevich

The Second World War is raging, and Jamilya's husband is off fighting at the front. Accompanied by Daniyar, a sullen newcomer who was wounded on the battlefield, Jamilya spends her days hauling sacks of grain from the threshing floor to the train station in their village in Kyrgyzstan. Spurning men's advances and wincing at the dispassionate letters she receives from her husband, Jamilya falls helplessly in love with the mysterious Daniyar in this heartbreakingly beautiful tale.

#film#cinema#ussr#Kyrgyzstan#soviet#world cinema#Kyrgyzstani#Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic#USSR#Soviet Union#Irina Poplavskaya#Sergei Yutkevich#Soviet films#Central Asia

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

1955 Sergei Bondarchuk is Otello

0 notes

Text

Venice in the art of Alexandra Exter (1882-1949)

Carnival in Venice (oil on canvas) 1930s

Carnival Procession (oil on canvas)

Masked Figures by the Banks of a Venetian Canal (oil on canvas)

Venetian Masks (oil on panel)

Pulcinella (gouache on paper) late 1920s-30s

Venice (oil and sand on canvas) 1925

Venice, 1915

"Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Ekster, also known as Alexandra Exter, was a Russian and French painter and designer. As a young woman, her studio in Kiev attracted all the city's creative luminaries, and she became a figure of the Paris salons, mixing with Picasso, Braque and others. She is identified with the Russian/Ukrainian avant-garde, as a Cubo-futurist, Constructivist, and influencer of the Art Deco movement. She was the teacher of several School of Paris artists such as Abraham Mintchine, Isaac Frenkel Frenel and the film directors Grigori Kozintsev, Sergei Yutkevich among others." [x]

"Exter painted views of Florence, Genoa and Rome, but ‘most insistent and frequent were images of Venice. The city emerged in various forms: via the outlines of its buildings, in the ‘witchcraft of water’. In glimmering echoes of Renaissance painting, in costumes and masks and its carnivals’.

"Exter’s characteristic use of the bridge as a stage platform, seen most clearly in Carnival in Venice, is a legacy of her time as Tairov’s chief designer [Alexander Tairrov, director of Moscow's Kamerny Theatre]; the director believed in breaking up the flatness of the stage floor which the artist achieved for him by introducing arches, steps and mirrors. Even in her easel work, the emphasis is at all times on theatricality. Bridges are used as proscenium arches, the architecture creates a stage-like space in which to arrange her cast."

"For all her modernity, references to Venetian art of the past abound in these paintings. The masked figures are influenced by the Venetian artist Pietro Longhi, to whom Exter dedicated a series of works around this time. The incredible blues used in both Carnival Procession and Masked Figures by the Banks of a Venetian Canal are a direct reference to Titian, who was famed for his use of ultramarine, the pigment most associated with Venice’s history as the principal trading port with the East." [x]

"Exter had long since abandoned the Cubist syntax by 1925 but her sense of colour remained together with a strong conviction, shared with Léger, that a work of art should elicit a feeling of mathematical order. In its graceful interaction of fragmented planes and oscillation between emerging and receding elements, Venice (1925) echoes the more precise qualities that also appear in Léger's work at this time, both artists occupied with the continuous modulation of surfaces and the 'melody of construction' that Le Corbusier was still advocating in the 1930s. But while Exter subscribed to Léger's theory that 'a painting in its beauty must be equal to a beautiful industrial production', she never fully embraced the aesthetics of the machine and rejecting the common opposition between ancient and modern, her work often retains a classical edge - for example in these trefoil windows, arches and vaults. Human figures, which had been nearly absent from her Cubo-futurist paintings, also return in other works from this period."

"She was undoubtedly aware of the concept of 'defamiliarisation', a term first coined by the influential literary critic Viktor Shklovsky in 1917:

'The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects 'unfamiliar,' to make forms difficult to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.'

An instance of this device is discernable in the present tight formation of the oars, seen from above. Like Braque and Picasso, Exter incorporates sand into certain areas of pigment to enhance the differentiation of surfaces, a technique also used to 'increase the length of perception'. The occasional lack of overlap between the boundaries of the textured surfaces and colour planes strengthens the paradoxical combination of tangible presence and elusive abstraction that makes Venice such a powerful work."

"Venetian subjects occur in Exter's work as early as 1915. A gigantic panneau of the city was one of the final works she produced in the Soviet Union and exhibited in the 1924 Venice Biennale." [x]

"The specific theme of the Commedia dell’Arte first appeared in Exter’s work in 1926 when the Danish film director Urban Gad approached her to design the sets and marionettes for a film which was to tell the story of Pulcinella and Colombina, transposing them from the Venice of Carlo Goldoni to contemporary New York. Pulcinella most likely relates to the artist’s subsequent experimentations on the theme of the Commedia dell’Arte. Pulcinella, who came to be known as Punch in England, is one of the classical characters of the Neapolitan puppetry. Typically depicted wearing a pointed hat and a mask, Pulcinella is an opportunist who always sides with the winner in any situation and fears no consequences." [x]

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Studio 1 Excursion: ArtSpace, AGNSW and MCA - PART 2 (10.5.24)

MCA: 24th Sydney Biennale

Juan Davila's oil paintings

Row 1: Untitled (2021), Untitled (2023)

Row 2: Untitled (2021), After Image Wilderness (2010)

Description: "Asked why he chose painting, Juan Davila once answered, 'An enjoyment … does not need explanation. Over an artistic career spent lacerating political figures, government policy and state control, the artist has indeed consistently refused to explain himself. From the outset, Davila's paintings have unflinchingly interrogated cultural, sexual and social identities, taking cues from popular culture, political discourse and mythology to create a complex and provocative body of work. Born in Chile, Davila moved to Naarm/Melbourne in 1974 after the fall of the socialist Allende government. However, his work does not suggest what 'should be', instead richly-illustrating the joys, anxieties, shames and triumphs of the contemporary moment. Psychological and psychoanalytic themes are often present, but the artist refuses to articulate or reveal a clear position, prompting us to question our own biases."

Freddy Mamani

Left to right: Diablada (2024, wood coated in gloss enamel), Salon Gallo de Oro (2024, maquette)

Description: "For the past 15 years, Aymaran architect Freddy Mamani has been designing and building Cholets, a combination of the French word 'chalet' and 'cholo', a reappropriated term once used to disparage those of indigenous descent in Bolivia. Interrupting the monotony of the existing cityscape with his vibrant and distinct neo-Andean style, each Cholet recalls the colours, designs and patterning unique to the Aymara culture. The title Diablada, in particular, recalls the Danza de los Diablos, an Andean cultural dance characterised by performers wearing carnivalesque costumes of trickster devil characters. Neo-Andean architecture largely emerged during the presidency, from 2006 to 2019, of Evo Morales, who was Bolivia's first indigenous leader in the country's 200-year history. It can be seen as a consequence of both his economic policies, which empowered a generation of Aymara business people, and of the sense of pride he instilled in the country's indigenous majority. Designed specifically for the needs of the Aymaran people, each Cholet is three to seven storeys high and follows the same essential layout; the ground floor is dedicated to commercial activities, the middle floors to cultural events, while the upper floors are residences. In this way, each Cholet develops and sustains its own economy. As Mamani says, 'this architecture has its own language, its own culture, its own identity'."

Left to right: Sergey Parajanov's The Colour of Pomegranates, (Out-takes and camera tests) (1969, film installation - colour film), Frank Moore's Lullaby (1997, oil on canvas with red pine frame)

Description of Parajanov's The Colour of Pomegranates: "The Colour of Pomegranates follows the 18th-century ashug (poet, singer) Sayat-Nova from his time in Georgia's royal court, love affair with a princess, consequent expulsion and journey across the Caucasus, to his death in a monastery. Transcending both traditional narrative and national boundaries to draw inspiration from across the region, much like Sayat-Nova's songs, the film recalls a series of Persian or Armenian illuminated miniatures. Created in the years following filmmaker Sergey Parajanov's disavowal of social realism and before his 1973 arrest by Soviet authorities under false charges, it contains references to the endurance of cultures across the South Caucasus region (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, as well as Ukraine) in the face of Soviet oppression. Re-edited by Sergei Yutkevich, a key figure of the avant-garde during the 1920s, his version balanced Parajanov's poetic style with the Gosfilmofond's (Russia's state film archive) demands to make the film more accessible. Thanks to documentary filmmaker Daniel Bird and the National Cinema Center of Armenia, the unseen out-takes from The Colour of Pomegranates were presented at the International Film Festival Rotterdam in 2019. Over a hundred canisters of out-takes have survived despite the Soviet authorities blocking its distribution. Such film would typically have been recycled rather than preserved. Starring Sofiko Chiaureli, who plays six characters, The Colour of Pomegranates left a lasting impact on the film industry and survives as a testament to the power of poetry as a form of resistance across centuries."

Description of Moore's Lullaby: "Ernest Hemingway once suggested that each person dies twice, once when they pass away and again when the last person to remember them forgets. However, if someone is forgotten before they die, then it might feel as if they never existed. This was the reality for those who lived through the AIDS crisis. For years, as people became sick and died America's gay community was ignored by the media and government. Painter and activist Frank Moore, who at 48 died with HIV/AIDS, created Lullaby by transforming his own sick bed into a whimsical landscape populated by a herd of buffalo. Given US President Ronald Reagan did not so much as utter the word AIDS until four years into the crisis, Moore suspected that his community, much like the endangered buffalo, was being left to become extinct. Drawing parallels between the AIDS epidemic and burgeoning ecological crises, Moore believed that this was an apocalypse for himself and those he loved."

Serwah Attafuah's Between this World & the Next (2023-2024, film installation - digital animation (3D computer-rendered models), and e-waste on wooden frame)

Description: "Serwah Attafuah's digital creation unfolds in a near-future Ghana, drawing viewers into an Afrofuturistic vista contrasting colonial remnants with utopian hope. The narrative, propelled by burning slave castles, sinking colonial ships and formidable female warriors, weaves a tale that is both haunting and empowering. This work embodies Ghana's matrilineal legacy, while addressing contemporary issues like e-waste dumping, symbolised by a bespoke frame crafted from e-waste and the incorporation of Sakawa, or 'internet magic. Responding to William Strutt's Black Thursday, February 6th, 1851, also on display, Attafuah delves into West African history, land rights and climate impact on its indigenous communities, fostering a dialogue between historical reverence and visionary insight. Through imaginative storytelling, Attafuah challeges conventional viewpoints and incites reflection, offering commentary on transcending historical bounds. Her avant-garde blend of cultural reflections with futuristic aesthetics establishes this work as a conversation between past legacies and speculative horizons, towards a reimagined future."

BONUS: Maria Fernanda Cardoso's Butterfly Drawings - Morpho didius (Peru) (2004, archival butterfly wings, acrylic, silicone and metal)

Description: "First, I wanted to be a scientist but I used more the model of theRenaissance artist, like Leonardo, which was scientist and artist. So lwent into art thinking that I could do both, I could do art and science." - Maria Fernanda Cardoso

"Maria Fernanda Cardoso is renowned for her use of unconventional materials, which often include symbolically charged elements from the natural world. ...a selection of the artist's butterfly drawings, featuring the insect's delicate wings arranged in mandala-like patterns. Underpinning these works is a system of geometry and repetition. The drawings invite us to look more closely and reflect on our complex relationship to the natural world."

0 notes

Photo

Сюжет для небольшого рассказа (Subject for a short story), dir. Sergei Yutkevich, 1969.

#sergei yutkevich#Сюжет для небольшого рассказа#Subject for a short story#anton chekhov#russian cinema#filmedit#1960s

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Othello (USSR, 1955)

#ok let's be honest#this film has not aged very well#for MANY reasons#but is still has some great cinematography#and it's still better than 99.9% of modern russian films#also this iago is amazing#othello#othello 1955#desdemona#iago#shakespeare#soviet cinema#russian cinema#sergei yutkevich

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Iya Savvina in Syuzhet dlya nebolshogo rasskaza (1969)

Soviet collectors card. Photo: publicity still for Syuzhet dlya nebolshogo rasskaza/Subject for a Short Story (Sergei Yutkevich, 1969).

#Iya Savvina#Syuzhet dlya nebolshogo rasskaza#1969#driving#Film Review#collector's card#soviet#publicity still#Subject for a Short Story#Sergei Yutkevich#cyrillic

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

#Anatoly Karanovich#Sergei Yutkevich#Soyuzmultfilm#Vladimir Mayakovsky#The Bathtub#puppet#animation#short

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

juices of a carved pomegranate soaking through a piece of white linen...

Sergei Parajanov’s The Colour of Pomegranates is a poetic biography of the eponymous 18th-century Armenian minstrel and bard, Sayat Nova, the “King of Songs”, recounting the stages of his life as writer, lover and priest.

Bold in its avant-garde imagery, mesmerizing in its patience; at only 77 minutes it is well and truly an epic. A film about poetry that is in and of itself poetic.

The film opens with a male voice proclaiming “I am he whose life and soul are torment” from a Sayat Nova poem. In his 2013 book, The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov, James Steffen states: “Much of the film’s thematic richness and emotional resonance derive from its dual vision as a film about [the poet] and as a coded autobiography of [Parajanov].”

_________________________________________________

Born Sarkis Yossifovich Paradjanian of Armenian parents on 9 January 1924 in Tbilisi, Georgia, Sergei Parajanov transferred from the Tbilisi Institute for Railway Engineering (1942) to study song and violin at the Tbilisi Conservatory of Music (1943-45) before gaining admission to VGIK, the Soviet All-Union State School for Film Art and Cinematography (aka Moscow Film School) in 1946. He graduated as a film director in 1951 under the tutelage of Ukrainian directors Igor Savchenko and Alexander Dovzhenko and found employment at the Kiev Film Studios (later renamed the Alexander Dovzhenko Studios).

Parajanov began his career by making the same film twice and with the same co-director, Yakov Brazelian. Shortly after completing their diploma film, Moldavian Fairy Tale (1951), shot in the Ukraine, he assisted his mentor Igor Savchenko on Taras Shevchenko (1951) and then remade with Brazelian their graduation short as a feature-length children's film titled Andriesh (1955). Moldavian Fairy Tale appears to be lost, although Parajanov claimed to have kept a copy at his home in Tbilisi. Three documentary films followed: Ballad(1957), about a choral group and made for the anniversary of the 1917 Revolution; Golden Hands (1958), about folk art and co-directed with two other documentary filmmakers; and Natalya Ushviy (1959), a portrait of a prominent Ukrainian stage and screen actress. All three documentaries can be found in the Kiev archive. His next three feature films at the Dovzhenko Studios -- The First Lad (1959), Ukrainian Rhapsody(1961), and The Flower on the Stone (1962) -- generally followed the prescribed principles of Socialist Realism, yet each did contain scenes that went against its grain.

Parajanov's ninth film in Kiev, Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1964), caused an uproar by smashing to bits the principles of Socialist Realism in Soviet cinema. Although awarded at several international film festivals, it was given only limited release in the Soviet Union. In trouble with the authorities for also protesting the arrest of Ukrainian poets and intellectuals, Parajanov accepted an offer from Yerevan to make a documentary on Akop Ovnatanian (1965), an Armenian portrait painter who had lived and worked in Tbilisi. Portraits by Ovnatanian were later incorporated into scenes in Kiev Frescoes (1966), a production interrupted at the Dovzhenko Studios after a fen weeks of shooting. Only fragments of Akop Ovnatanian and Kiev Frescoes remain today. The same fate befell Sayat Nova, shot under primitive conditions in Armenia. When the director's cut was confiscated, Sergei Yutkevich cut 20 minutes out of the original in an effort to save the film and re-edited the remainder into The Colour of the Pomegranates (1969) for limited Moscow release. "My masterpiece no longer exists" (Paradjanov) -- although an attempt has recently been made in Armenia to reconstruct the original version.

All further attempts to make a film proved in vain. After years of intrigue and suspicion, Parajanov was arrested in Kiev on 17 December 1973 and, after a court hearing, sentenced on 25 April 1974 to five years imprisonment at the Dnepropetrovsk camp for hardened criminals. The charges were given as "business with art objects," "leaning towards homosexuality," "incitement to suicide," and "black-marketing." In 1978, as the result of world-wide protests and petitions made by friends and artists, he was released and allowed to return to his family home in Tbilisi, but not permitted to find work in a film studio. On 11 February 1982, he was arrested again by the KGB, "for bribing a public official" to help a nephew gain entrance to the university, and detained in the Voroshilovgrad prison until November 1982.

After 15 years on a blacklist, Parajanov received the support of Eduard Shevarnadze, First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party, to make the feature The Legend of Suram Fortress(1985), co-directed by actor Dodo Abakhidze, and the documentary Arabesques on the Theme Pirosmani (1986) at the Gruziafilm Studio in Tbilisi. His last film, Ashik Kerib (1988), a Georgian-Armenian-Azerbaijan co-production, has received limited release in these countries. On 4 June 1989, he began shooting the first scenes from his autobiographical film, Confession, at his family home in Tbilisi. Three days later, he was taken to a hospital with respiratory problems. An operation for lung cancer in Moscow followed, then radiation treatments in Paris. Sergei Parajanov died on 20 July 1990 at the age of 66 in Yerevan, where he is buried.

#The Colour of Pomegranates#Sayat Nova#Sergei Parajanov#Սերգեյ Փարաջանով#Cinematic Still#Film#Still#Stills

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theater poster for Bertolt Brecht's play 'The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui', an allegory-satire of the rise of Adolf Hitler, directed by Sergei Yutkevich and Mark Zakharov. (Soviet Union, 1960s)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The cadenza of Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto 1 Mvt 4 is like muddling through an analog radio to find that station. Before you think you know what you’re hearing, Shostakovich turns the dial. Every measure or half-measure is a seemingly unrelated new key, a different figuration, while underlying counterpoint weaves in different registers at turbo speeds. There is an element of unpredictability, disheveled patterns, but not quite chaos. Everything written was written with the utmost intent. When the solo piano reenters at rehearsal 76, the listener is jolted with a strong Fm that would otherwise ground to C. Rather, Shostakovich marches into a direct-motion circle of fifths. He doesn’t stay focused, tuning the radio again and slightly disjointing the harmonic and melodic progression. The end of the circle is a 6+ harmony on Gb / F# that’s missing its 3rd and 5th intervals, soaring as a triangle would when the orchestra is tacet. The ping precedes a conclusive V - I into C major. There is so much shifting color and character that when the piece ends on the blandest of all chords, C Major, the heavy 4-octave strikes are bright rays of bombast, with a comical celebratory fanfare striding alongside. https://youtu.be/B_CbPjUxpUM “The Piano Concerto Op.35 is also reflective of a style known as eccentrism. Eccentrism, as defined by FEKS, embraces popular genres and popular art of the twenties. The Russian director and writer Sergei Yutkevich described this as a combination of 'the music-hall, the circus and the cinema.' In a circus performance, many events and stunts seem to happen all at once, yet there is an underlying sense of organization.“ --Jung-Hwa Lee, M.M.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

my top 111 first viewings of 2017

(pictured films in bold)

1) Reality's Invisible (Robert E. Fulton, 1971)

2) 화엄경 / Passage to Buddha (Jang Sun-woo, 1993)

3) 河童のクゥと夏休み / Summer Days With Coo (Keiichi Hara, 2007)

4) E V E R Y T H I N G (David OReilly, 2017)

5) Twin Peaks: The Return (David Lynch, 2017)

6) Path of Cessation(?) (Robert E. Fulton, 1974)

7) Gambling, Gods and LSD (Peter Mettler, 2002)

8) "Short Films by Robert Fulton" (Robert E. Fulton, various)

9) 边走边唱 / Life on a String (Chen Kaige, 1991)

10) 50 Feet of String (Leighton Pierce, 1995)

11) មុនដំបូងខ្មែរក្រហមសម្លាប់ប៉ារបស់ខ្ / First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers (Angelina Jolie; second unit director & director of photography Alexander Witt, 2017)

12) the KILLING of a SACRED DEER (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2017)

13) 百日紅~Miss HOKUSAI~ / Miss Hokusai (Keiichi Hara, 2015)

14) Nazar (Mani Kaul, 1990)

15) Ад / Põrgu / Hell (Rein Raamat, 1983)

16) Manoel dans l'île des merveilles / Manoel on the Island of Marvels / Manuel on the Island of Wonders (Raoul Ruiz, 1984)

17) Odchádza clovek / A Man Leaves Us / The Man is Leaving (Martin Slivka, 1968)

18) 風月 / Temptress Moon (Chen Kaige, 1996)

19) Krisha (Trey Edward Shults, 2015)

20) Christine (Antonio Campos, 2016)

21) Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952)

22) A Reflection of Fear (William A. Fraker, 1972)

23) mother! (Darren Aronofsky, 2017)

24) Le tout nouveau testament / The Brand New Testament (Jaco Van Dormael, 2015)

25) Une femme a passé / A Woman Passed By (René Jayet, 1928)

26) Good Time (Josh and Benny Safdie, 2017)

27) Le pays des sourds / In the Land of the Deaf (Nicolas Philibert, 1992)

28) Munchsferatu (Julien Lahmi, 2017)

29) Silent Snow, Secret Snow (Gene R. Kearney, 1964)

30) માટી માણસ / The Mind of Clay / Mati Manas / Maati Manas (Mani Kaul, 1985)

31) Zardoz (John Boorman, 1974)

32) Rekni mi neco o sobe - René / Tell Me Something About Yourself: Rene (Helena Trestíková, 1992)

33) L'amour à la mer / Love at Sea (Guy Gilles, 1964)

34) सिद्धेश्वरी / Siddeshwari (Mani Kaul, 1990)

35) The Passing (Bill Viola, 1992)

36) 霸王別姬 / Farewell My Concubine (Chen Kaige, 1993)

37) Play for Today: "The Lie" (Alan Bridges; written by Ingmar Bergman, 1970)

38) 另一種教育 / Lessons from a Calf (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 1991)

39) उसकी रोटी / Uski Roti / His Daily Bread (Mani Kaul, 1970)

40) Simon Killer (Antonio Campos, 2012)

41) 金刚经 / The Poet and the Singer / Diamond Sutra (Bi Gan, 2012)

42) 青梅竹马 / green plums and a bamboo horse / Taipei Story (Edward Yang, 1985)

43) Docteur Jekyll et les femmes / The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne (Walerian Borowczyk, 1981)

44) "Leighton Pierce - short films" (all the ones I've watched)

45) Elsewhere (Nikolaus Geyrhalter, 2001)

46) I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like (Bill Viola, 1986)

47) No Man of Her Own (Mitchell Leisen, 1950)

48) Without Memory (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 1996)

49) Pointilly / Le château de Pointilly (Adolfo Arrieta, 1972)

50) Otello / Othello (Sergei Yutkevich, 1956)

51) The Fourth Dimension (T. Minh-ha Trinh, 2001)

52) Deadfall (Bryan Forbes, 1968)

53) En kärlekshistoria / A Swedish Love Story (Roy Andersson, 1970)

54) Code Blue (Urszula Antoniak, 2011)

55) ...Geist und ein wenig Glück (Ulrich Schamoni, 1965)

56) Mulholland Dr. - Pilot (David Lynch, 1999)

57) Vital (Shinya Tsukamoto, 2004)

58) Dawn of an Evil Millennium / Dawn of an Evil Millennium: The Trailer (Damon Packard, 1988)

59) The Pursuit of What Was (Huang Ya-li, 2009)

60) Фабрика / Fabrika / Factory (Sergey Loznitsa, 2004)

61) カラフル / Colourful / Colorful (Keiichi Hara, 2010)

62) Mysteries of the Unseen World 3D (Louie Schwartzberg, 2013)

63) Cruel Optimism (Paul Clipson, 2017)

64) A Woman's Tale (Paul Cox, 1991)

65) Chargez ! (Johanna Vaude, 2017)

66) 시 / Poetry / Shi (Lee Chang-dong, 2010)

67) Eastern Avenue (Peter Mettler, 1985)

68) Nothing Personal (Urszula Antoniak, 2009)

69) High-Tech Exploration par Johanna Vaude (Johanna Vaude, 2016)

70) The Reflecting Pool (Bill Viola, 1979)

71) Retour en Normandie / Back to Normandy (Nicolas Philibert, 2007)

72) Les films rêvés / Dreaming Film (Eric Pauwels, 2010)

73) Dream Enclosure (Sandy Ding, 2014)

74) 白い朝 / Ako / AKO: 16 ans japonaise / White Morning (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1965)

75) The Unnamed (Huang Ya-li, 2010)

76) Twilight's Last Gleaming (Robert Aldrich, 1977)

77) Dzieje grzechu / The Story of Sin (Walerian Borowczyk, 1975)

78) Liebelei (Max Ophüls, 1933)

79) 달마가 동쪽으로 간 까닭은 / Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? (Bae Yong-kyun, 1989)

80) The Wheel of Becoming (Bill Viola, 1977)

81) Abendland (Nikolaus Geyrhalter, 2011)

82) Frost (Fred Kelemen, 1997)

83) Arrière-saison (Jean-Claude Rousseau, 2016)

84) 海よりもまだ深く / After the Storm (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2016)

85) 幻の光 / Maborosi (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 1995)

86) Look Inside The Ghost Machine (Péter Lichter, 2010)

87) Chez moi / My Home (Phuong Mai Nguyen, 2014)

88) दुविधा / Duvidha / Indecision / In Two Minds (Mani Kaul, 1973)

89) Emperor of the North Pole (Robert Aldrich, 1973)

90) Le roman d'un tricheur / The Story of a Cheat (Sacha Guitry, 1936)

91) Le convoi / Fast Convoy (Frédéric Schoendoerffer, 2016)

92) Deserts (Bill Viola, 1994)

93) Charles Manson Superstar (Nikolas Schreck, 1989)

94) 空山灵雨 / Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979)

95) Voda a práca / Water and Labor (Martin Slivka, 1964)

96) Impressions: A Journey Behind the Scenes of Twin Peaks (Jason S., 2017)

97) Контакт / Kontakt / Contact (Vladimdir Tarasov, 1978)

98) Fountain of Dreams (Jordan Belson, 1984)

99) Les perles de la couronne / The Pearls of the Crown (Sacha Guitry, 1937)

100) Fassbinder: at elske uden at kræve / Fassbinder - lieben ohne zu fordern (Christian Braad Thomsen, 2015)

101) Adventure Time with Finn & Jake: Food Chain (Masaaki Yuasa, 2014)

102) 海街diary / Our Little Sister (Kore-eda Hirokazu, 2015)

103) Metachaos (Alessandro Bavari, 2010)

104) Love's Refrain (Paul Clipson, 2016)

105) Le bercail (Marcel L'Herbier, 1919)

106) Never Let Go (John Guillermin, 1960)

107) 오아시스 / Oasis (Lee Chang-dong, 2002)

108) Hounds of Love (Ben Young, 2016)

109) We hear the distant ring of Saturn (Dalibor Baric, 2016)

110) Faisons un rêve... / Let's Have a Dream (Sacha Guitry, 1936)

111) 蝴蝶夫人 / Madame Butterfly (Tsai Ming-Liang, 2009)

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Klara Gazul"

Indian ink and silverpoint on drawing paper. Design for a theatre poster. Inscribed in pencil to verso "Klara Gazuls Theatre / M.G.S.P.S. / W.W. Alexeyeva-Meshiyeva/ drawing by Sergeij Yudkewitsch / Moscow 10/III. 24".

Attributed to Sergei Yutkevich, 1924.

"Le Théâtre de Clara Gazul" is a drama written by Prosper Mérimée in 1825. https://www.lempertz.com/en/catalogues/lot/1084-1/14-klara-gazul.html

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charlie Chaplin in Moscow

Early Soviet filmmakers took great inspiration from Charlie Chaplin, but his critique of mass production put him at odds with them.

In Charlie Chaplin’s 1914 film The Fatal Mallet, you can see “IWW” chalked on a wall in the background. While no one knows if the director — who grew up in south London’s slums and became a globally recognized comedian — supported the Wobblies at the time, we do know that the characters he played in dozens of short films in the 1910s and early 1920s would have.

In The Adventurer, he plays an escaped convict; in Police, an ex-con forced into burglary by unemployment; in The Bank, a janitor working next to, but unable to get ahold of, money; in Work, a downtrodden contractor; in The Immigrant, a migrant so frustrated by his treatment he kicks an immigration officer; and, of course, in The Tramp, a homeless man looking for a stable life. All these men, who populated the rapidly changing, expanding, and radicalizing United States, might well have written IWW on a fence in Los Angeles.

Chaplin wouldn’t state his politics explicitly until well into the 1930s, a move that would put him in the House Committee on Un-American Activities’ crosshairs. But in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, young Soviet artists, designers, and filmmakers already thought they knew exactly what his politics were.

In 1922, the new Moscow magazine Kino-Fot, edited by the constructivist theorist and committed Communist Aleksei Gan, published a special issue on Chaplin. Throughout, painter and designer Varvara Stepanova depicted the actor as an abstract object, his body’s parts transformed into exploded shards and flying polygons, identifiable only thanks to his trademark hat, cane, and moustache.

Aleksandr Rodchenko’s text declares, manifesto-style:

[Charlie’s] colossal rise is precisely and clearly — the result of a keen sense of the present day: of war, revolution, Communism.

Every master-inventor is inspired to invent by new events and demands.

Who is it today?

Lenin and technology.

The one and the other are foundations of his work.

This is the new man designed — a master of details, that is, the future anyman.

That same year in Petrograd, teenagers Grigori Kozintsev, Leonid Trauberg, and Sergei Yutkevich, who collectively called themselves The Factory of the Eccentric Actor (FEKS), published something called “The Eccentric Manifesto.” Under the sign of “Charlie’s arse,” they demanded:

ART AS AN INEXHAUSTIBLE BATTERING RAM SHATTERING THE WALLS OF CUSTOM AND DOGMA. But we have our forerunners! They are: the geniuses who created the posters for cinema, circus, and variety theatres, the unknown authors of dust jackets for adventure stories about kings, detectives, and adventurers; like the clown’s grimace, we spurn your High Art as if it were an elasticated trampoline in order to perfect our own intrepid salto of Eccentrism!

Meanwhile, a film director was perfecting a technique that would eventually bear his name: the Kuleshov effect, in which the juxtaposition of unrelated material creates a new mental link between them. He argued against slow paced, European montage, which treats cinema as a high art form akin to theater, and for the high-speed American montage that thrilled audiences.

Somehow, these people, all trying to create art in the young Soviet Union, agreed that Chaplin represented their ideal. In a series of theatrical productions and films over the next decade, they would try to make something that had the same effect on their viewers — a socialist, avant-garde slapstick comedy, informed by silent farce, technological romanticism, and contempt for high culture.

This history sits a little strangely with what many know about the Soviet Union’s first fifteen years of experimental filmmaking. Its directors, including Sergei Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov, and Vsevelod Pudovkin as well as documentary pioneers like Dziga Vertov and Esther Shub, have earned formidable reputation for applying Marxist methodology to film.

Their contributions, including “the montage of attractions,” the “camera eye,” the “intellectual montage,” and the aforementioned Kuleshov effect, have grounded film curricula since the 1960s, often used in contrast to Hollywood’s formulaic spectacles. In fact, when French filmmaker Jean Luc-Godard stopped making crowd-pleasers in the 1960s and opted instead for punishing Althusserian didactic tableaux, he signed his films Dziga Vertov Group.

What this story leaves out is how Soviet directors’ ideas came out of their obsessions with the crassest and most lurid kinds of American film, its chases, special effects, and pratfalls. In translating Chaplin for Lenin, they combined these elements with their equally strong interest in another aspect of 1910s America: scientific management and industrial efficiency, especially the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford.

The resulting films shared a bizarre and unstable comic Americanism, which you can see still in films like Kuleshov’s Adventurers of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, a high-speed, Keystone Kops satire about Western perceptions of the Soviet state; Boris Barnet’s Miss Mend, where an international communist secret society foils the evil plans of nefarious capitalists; Sergei Komarov’s A Kiss For Mary Pickford and Pudovkin’s Chess Fever, which used footage of American stars on Soviet visits and put them into new, bizarre farces; and Eisenstein’s first feature, Strike, where insurgent workers move with all the bounce and assurance of a mass circus troupe.

Stage director Vsevelod Meyerhold helped pioneer this style. From the early 1920s onwards, he developed a “biomechanical theater” that borrowed equally from the circus’s high-wire tricks and gymnastic leaps, from Charlie Chaplin’s and Buster Keaton’s jerky, ironic slapstick, and from the USSR’s development of Taylorism, led by government-sponsored think tanks like the League of Time and the Central Institute of Labor. The latter’s founder, Aleksei Gastev, a former metalworker, union leader, and poet, became a key figure for most of the 1920s avant-garde.

Looked at coldly, his ideas are unnerving and dystopian. He imagined the new Soviet working class as nameless machines working in seamless unified motion, a somewhat unlikely and wholly unfulfilled demand of the chaotic, largely rural, and unskilled labor force of the Soviet 1920s. Yet while Taylorism involved monitoring the worker’s motions to transform them into a predictable, high-performance cogs, Meyerhold’s biomechanics saw its protagonists as Chaplin-like comic machines, capable of humor and exuberance, not drab labor.

This appears even more strongly in another form of Soviet Chaplinism, which comes from an unlikely direction — formalist literary criticism. The great Viktor Shklovsky used Chaplin as an exemplar of his concept of “ostranienie” or “making-strange.” In his 1922 Literature and Cinematography, he tried to work out what set Chaplin apart from other actors, finally deciding that “the fact that [the movement] it is mechanized” makes it so funny.

In the American context, Chaplin was satirizing industrial, mass-production labor, but in the Soviet landscape — destroyed by seven years of war and economic collapse — the little tramp who moved with jerky assurance through a mechanized world was exactly the sort of “new man” they needed.

American visitors found this all disconcerting. The sympathetic artist Louis Lozowick had to explain to eager young constructivists in Moscow that he didn’t know anything about biomechanics, and that they, the Russians, had invented it themselves. A Ford Motor Company representative, treated by his hosts to some biomechanical theater, thought the whole thing ridiculous and farcical.

In the mid-1920s, the Soviet Eccentrists would move away from the leaps, special effects, and extravagant silliness of movies like The Adventures of Mr West and develop a more sober style, although equally indebted to the frantic pace of American montage and cartoonish American acting styles. The results, such as Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and Pudovkin’s Mother, had a mixed reception in the USSR but became international sensations. Their kinetic action sequences changed cinema history, and their rousing revolutionary narratives got them banned across the free world.

This is when Charlie Chaplin first became aware of his Soviet fan club. He opposed the bans and helped get these films shown to American audiences. When Eisenstein made an abortive attempt to film Dreiser’s American Tragedy in Hollywood, the two directors became fast friends. But the Soviet film director who had the strongest effect on Chaplin — whose feature films like The Gold Rush and City Lights had become ever more sophisticated and socially critical — was Eisenstein’s great adversary, Dziga Vertov.

A groundbreaking documentarian, Vertov thought fictional films were inherently bourgeois and escapist. Nevertheless, his special effects, comic juxtapositions, and pounding sense of rhythm made him an Americanist in his own way. In 1930, he made the first Soviet sound film, Enthusiasm — Symphony of the Donbas. This hour of grueling industrial propaganda doesn’t much resemble The Fatal Mallet. It depicts mechanizing the Donets coalfield in Eastern Ukraine and teaching the mineworkers Taylorist efficiency.

Chaplin, however, was attracted to the unrivalled intensity of its juxtaposition of sound and image. Using field recordings from Ukraine’s mines and steelworks, Vertov created an industrial jazz of still-astonishing power, a relentless clanging pulse echoing that puts the soundtrack closer to Einsturzende Neubauten than to Al Jolson. Chaplin called it “one of the most exhilarating symphonies I have ever heard.”

Six years later, he made his response. Modern Times has become justly famous for its definitive critique of Taylorism and Fordism. In the factory sequences, machines feed Chaplin, his all-seeing boss monitors him on film, and the production line eventually eats him, until he floats, weightless, through the cogs inside, a tragic and bitter image of the smooth and seamless mechanized labor the Soviets longed for. Insisting on keeping the film wordless, Chaplin used a soundtrack of rhythmic clangs and crashes that mirrored Vertov’s “Donbas” symphony.

Coming when Taylorist speed-up was sparking some of the greatest strikes in American history — not to mention the CIO’s formation — you might expect that the Soviets welcomed the film as a critique of American capitalism’s brutality.

They didn’t. In a text called “Charlie the Kid,” Eisenstein criticized his friend for his satire’s infantilizing and utopic take on what mass production does to workers. Regarding the factory sequence, he asserted, “At our end of the world, we do not escape from reality to fairy-tale, we make fairy-tales real.”

The tramp of Modern Times, exhausted by labor and made homeless by unemployment, accidentally picks up a red flag midway through a strike, getting him arrested as a dangerous agitator. Chaplin himself would be notably supportive of the Soviet Union, and his refusal to fall in with McCarthyism was admirable; but the tramp might have silently held other opinions about industrial efficiency and five-year plans than those he helped inspire.

0 notes

Photo

Sergei Yutkevich, Design for a theatre poster, Klara Gazul, 1924.

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

movies watched in april, order watched

Встречный (1932) / Counterplan / Shame dir. Fridrikh Ermler & Sergei Yutkevich

Silver Street (1975) dir. Nicky Hamlyn

Black Narcissus (1947) dir. Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger (rewatch)

That Has Been (1984) dir. Nicky Hamlyn

高度戒備 (1997) / Full Alert dir. Ringo Lam

Silvercup (1998) dir. Jim Jennings

Erotikon (1929) dir. Gustav Machatý

मति मानस (1985) / Mind of Clay dir. Mani Kaul

Aviation Vacation (1941) dir. Tex Avery (rewatch)

Billy Boy (1954) dir. Tex Avery (rewatch)

books

pages of the wound (john berger) loving (henry green) snow country (yasunari kawabata) the man who knew too much (gk chesterton) the lathe of heaven (ursula k le guin) pantagruel (françois rabelais) gargantua third book

3 notes

·

View notes