#Scramasax

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@nimblermortal sent me this last week:

A second blade weapon became increasingly common in the later Viking Age. It does not have a formal name, being often referred to as a fighting-knife or battle-knife, and it was essentially a development of the one-handed, long seax knife of the Migration Period. A single-edged blade with a thick back that added weight to a short, stabbing blow, it seems to have been intended as a back-up weapon. By the tenth century, battle-knives had elaborate scabbards that were worn horizontally along the belt, allowing them to be drawn across the body from behind a shield if the sword was gone; a variant hung down at an angle from an elaborate harness. It seems they may also have been worn on the back - again for a swift, over-the-shoulder draw. Children of Ash and Elm by Neil Price @petermorwood (Mr Morwood! Mr Morwood!) I found an archaeologist claiming people were doing over-the-shoulder draws! Would you care to weigh in?

*****

Would I ever! That's a button well pushed. But things got odd when I tried, because as soon as I'd written even the smallest reply and saved to Draft, this happened:

Letting it stand would have seemed like I was trying to avoid comments, corrections or criticism, but despite poking around in Settings there was no way to turn things on. It was only by cut-and-pasting @nimblermortal's entire original as a Quote starting a new post that the problem was resolved.

Anyone else encountered this?

Anyway, on with the lecture response. :->

*****

As regards Back-Carry / Back-Draw of "battle-knives", I'm not convinced.

("Battle-knife" is a term I've never seen in connection with any Viking Age weapon. What's the Old Norse for it? German "Kriegsmesser" (war-knife) refers to something much bigger from 500 years later, also not back-carried or back-drawn - which from here on will be BD / BC.)

To get where he is now, a full professor, Neil Price will have defended his PhD, and should know such a statement as "It seems they may..." will need evidence to support it.

That phrase is easy to write, as is "According to legend..." and "It is said..." However these are IMO default History Channel phrases, with all the authenticity that implies. None of them actually PROVE what they're speculating.

"Experiments conducted by museum staff wearing authentic armour reveal that IT SEEMS medieval knights could use smartphones."

But does it prove medieval knights USED smartphones? See what I mean?

*****

I first asked if anyone had actual proof of BC / BD on Netsword almost 30 years ago, and to date there's been nothing. I've also posted about it quite a lot on Tumblr, so being poked with this particular stick is no surprise. :->

The quotation from "Children of Ash and Elm" is the first time I've heard of a trained archaeologist making a claim for BC / BD, and the odd part is that Prof. Price also states the weapon was intended for "...a short, stabbing blow" - which means wearing it horizontally in front makes far more sense. From that position it can be drawn far faster and with less telegraphed intent than "...on the back - again for a swift, over-the-shoulder draw."

Reaching up for any weapon carried across the back, whether long or short, is a bigger movement - and thus less "swift" - than snatching out the same weapon worn at the hip or across the front at waist level, especially if - as he suggests - that move is masked behind a shield (or for that matter a cloak, a door, or a half-turned torso...)

Try both moves in front of a mirror with a ruler or even a length of dowel, and you'll understand.

With a weapon-hilt visible behind one shoulder or just a cross-belt suggesting something slung out of sight, what's a Norse warrior going to think when his potential opponent reaches up there? At a moment of hot words and high tension, will he wait while an itchy back gets scratched or until an attack happens?

The explosive violence described in sagas suggests not.

If Prof. Price has solid proof for his BC / BD notion in the form of artefacts or art - and it'll need more than a one-off example - I'll be very pleased to finally see some "show me" evidence.

(It won't do anything for longswords of 500 years later, of course, though I bet the uncritical back-carry brigade would leap on it regardless.)

But without that evidence, I'm taking "it seems" with a wary pinch of salt.

*****

There's a weird internet fixation about BC / BD (which are NOT the same thing) and an equally weird need to show that back-draw "works", whether with hooks under the guard and a leather condom at the point...

... or by being open most of the way down one side.

Neither are real-world historical, so let's see how they work in fantasy.

IMO they're not appropriate there either, because the designers are so eager to provide working BC / BD that they ignore the main function of a scabbard, which is to carry the weapon in something which protects people from the weapon's edges, and the weapon from the elements.

Real scabbards for real swords went to some trouble over that. They protected people, including the wearer, with a completely enclosed wooden, leather and / or metal case, and protected the blades by having them fit into their case well enough that inclement weather stayed out.

This fitting could involve metal collars (Japanese habaki), or tight-gripping lanolin-rich fleece linings, or leather flaps, caps and rain-guards mounted on hilt or scabbard-throat. Real scabbards didn't have exposed metal and weren't open-sided rainfall buckets, because the priorities of actual sword users were very different to those of back-carry fans.

Given the number of posts I've seen about the technical side of fantasy world-building - history, geography, even geology and meteorology - I think this difference is worth noting.

*****

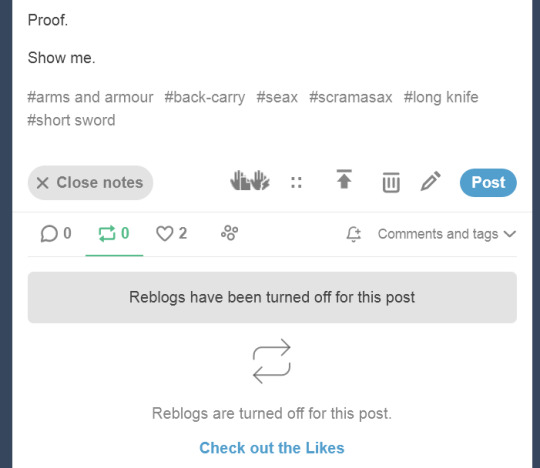

The first time I recall seeing back-carry mentioned in a historical-not-fantasy context was in "Growing Up in the Thirteenth Century", © Alfred Duggan 1962. Here's the extract in question:

Unfortunately Duggan - though according to his Wikipedia entry "His novels are known for meticulous historical research" - doesn't give any cited source for this; his introduction to the book says:

I know the feeling! :->

I'd still trust him more than some modern historical writers who seem over-willing to add a touch of fantasy speculation / interpretation if it rounds out something inconclusive, makes the history more interesting or chimes with a personal agenda.

"Accurate" is better than "interesting", and "I don't know" is better than making stuff up.

*****

To repeat: I've yet to see any museum-exhibit or manuscript-illumination examples of BC / BD ever done For Historically Real with Western European swords, especially the hand-and-a-half longswords on which modern back-draw fans seem fixated.

A seax, scramasax or just plan sax is shorter, but yet again, this is the first time I've read anything even remotely scholarly about them or their later Viking-age version (saxes were associated more with Saxons than Vikings, guess why?) being BC / BD.

By contrast, there are at least three art instances of saxes worn horizontally, on 10th century crosses at Middleton Church, Yorkshire:

The art is backed up by surviving examples with scabbard-fittings still in place, indicating how they were worn. Here's one example, from the Metropolitan Museum, New York which makes that very obvious.

The little decorative masks (originally part of the top of the scabbard, now corroded onto the blade) are clearly meant to be This Side Up, and also show that this scabbard was This Side Out for a right-handed draw, since there's no detail on the back.

There's a similar fancy-front / plain-back / right-hand-use leather sax scabbard at the Jorvik Centre in York.

There's only a single photograph of this bigger one - 54cm (21.5 in) overall - from the Cleveland Museum of Art, with no way to see if the L-shaped scabbard mount is decorated on just one or both sides. However it does indicate the weapon was meant for horizontal wear.

I've also flipped the website photo to show right-hand use, because "It seems..." (hah!) more probable. Here's why I did it:

For most of history being left-handed was unusual, a disapproved-of aberration and the origin of the word sinister.

Left-handers were useless in any formation from Ancient Greece through Ancient Rome to the Saxon and Viking period where the shields of a phalanx, testudo or shield-wall had to overlap for mutual support.

In the Middle Ages, both the specialised armour and the layout of jousting courses were almost 100% right-hand only.

Most surviving swords with asymmetrical hilts, such as swept-hilt rapiers, are made to for right hands not left.

Even nowadays many weapons - including the current British Army rifle (SA-80 / L85/A2) - are set for right-handers only.

*****

The longest saxes are called Langseax (surprise) though this may be a modern-ish term. Here's one from the British Museum, the so-called "Seax of Beagnoth"...

...which is 72 cm (28.5 in) total / 55cm (22 in) blade.

That's about the same as a Roman gladius (another sword never back-worn despite its convenient size) and is a good 25-30cm (10-12 in) shorter than the average "proper" sword of the same period, which means it could be drawn over-shoulder...

However the layout of its runic engraving shows it was almost certainly meant to be worn horizontally As Per Usual.

*****

And now we've come all the way back around to Prof. Price's claim that Vikings did BC / BD with their battle-knives.

Such a claim needs proof.

Please, show me some.

#arms and armour#back-carry#seax#scramasax#long knife#short sword#left-handed weapons#research#evidence

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

As modern science and better archeology methods reexamine historical sites more of women’s history will emerge

by Sarah Durn September 27, 2021

The National Museum of Stockholm's Ride of the Valkyries was painted during the Victorian period, which saw renewed interest in Vikings. Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

In 1871 on the sleepy island of Birka, Sweden, Hjalmar Stolpe, a Swedish entomologist turned archaeologist, discovered the lavish grave of a Viking warrior. Around the seated body were the remains of two sacrificed horses, as well as a double-edged sword, a scramasax (a long, thin knife), a bow, a shield, and a spear—every weapon known to the Viking world. It was an astonishing find, especially since Viking warrior graves rarely contain more than three weapons. There was also a full set of hnefatafl, the board game often known as Viking chess, which indicates the strategic thinking and authority of a war leader. A thousand years ago, the site would’ve abutted the Warrior’s Hall, where a garrison lived to protect the bustling Viking town of Birka. The weapons, game pieces, location: Everything told scholars that the man buried in what is known as grave Bj 581 was a prominent, well-respected Viking warrior. No one was really prepared when DNA tests were conducted in 2017 and a new story began to emerge. This was a prominent warrior, all right, but the occupant of Bj 581 wasn’t a man. She was a woman.

Viking historian Nancy Marie Brown’s new book, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women, explores what life might have been like for the warrior woman of Bj 581.

Using more evidence from the recent tests conducted on the remains, Brown traces her journey from Norway to the British Isles to Kiev then, finally, to Birka. Brown imagines the unnamed warrior meeting other prominent Viking women, such as Gunnhild, Mother of Kings, or Queen Olga, ruler of the Rus Vikings in Kiev. She also explores the Viking sagas and contemporary sources with a new lens.

How did you initially get interested in Vikings—and female Vikings in particular?

When I went to college, I actually wanted to study fantasy writing and, you know, learn to write like Tolkien. I learned very quickly that that was not appropriate for an English major in the 1970s, so I decided to study what Tolkien studied, and he was a professor at Oxford University, teaching Old English and Old Norse. So I started reading all of the Icelandic sagas that I could find in translation. And when I ran out of the English versions, I learned Old Norse so that I could read the rest of them.

One of the things I liked about [the sagas] the most was that they had really interesting women characters. There’s a queen in Norway who appears in about 11 sagas, Queen Gunnhild, Mother of Kings. She led armies. She devised war strategy. And then I was looking at the valkyries and the shieldmaids and thinking, you know, these are really interesting people that have always been considered to be mythological.

So when I learned in 2017 that one of the most famous Viking warrior burials turned out to be the burial of a woman, that just absolutely dazzled my imagination.

Is this the first confirmed grave of a female warrior that we have?

This is the one that has the best proof. There are one or two others that have since been DNA tested and proven to be female. But in each of these cases, it’s hard to say if the person in the grave, whether male or female, actually was a warrior, or if the object that we are interpreting as a weapon was used for hunting or for some other purpose.

In this case, it’s every Viking weapon known to history. So it’s such a clear result. And the DNA was so completely female.

When Stolpe discovered the Viking gravesite Bj 581 in 1887, he assumed the remains were of a man. That assumption was shown to be wrong 140 years later. Rapp Halour / Alamy Stock Photo

What do we know about the life of the Viking warrior woman in Bj 581?

In 2017, by testing her bones and her teeth, [scholars] could say she was between 30 and 40 years old when she died. They could also tell that she ate well all of her life. So she came from a rich family or maybe even a royal one. She was also quite tall, about 5’7”. By the minerals in her inner teeth, [scholars can determine] she may have come from southern Sweden or Norway, and also that she went west maybe as far as the British Isles before her molars finished forming. She didn’t arrive in Birka until she was 16.

We also have her weapons and a little bit of clothing that were found in the grave. And these link her to what is known as the Vikings’ East Way, which was the trade route from Sweden to the Silk Road.

We can link, through the artifacts and through the bones, that she could have traveled from as far west as Dublin to as far east as at least Kiev in the 30 to 40 years of her life.

How do we know that there were Viking warrior women?

They are mentioned many, many, many times in the literature. In most cases, they have been dismissed as mythological because, of course, we know warriors were men. But we don’t know that. That is an assumption that is based on traditional Victorian ideas that because women are mothers, they’re nurturing, they’re peacemakers, and they don’t fight.

That’s not historically true. Women have always fought. And they appear in most cultures until the 1800s, when Viking studies and archaeology pretty much started. So we sort of have this problem of bias in our earliest textbooks.

But now we have actual scientific proof of one warrior woman in the Viking Age. And as the scientists who did the study say they would be very surprised if she was the only one.

This small female Viking warrior figurine discovered in Harby, Denmark, has been interpreted as a mythological valkyrie. John Lee / National Museum of Denmark

There’s this assumption that the warrior men of myth must have been based on real people, but it’s not the same for the mythical warrior women. Why is that?

It’s just an assumption based on what people think women are like. Most of the material we have from the Middle Ages was written by men, and most of the material we have until the 1950s was written by men, and women are slowly making their way into the field of Viking scholarship. But many of them are still working under the assumptions that they were taught.

I noticed when I went back and reread some of the sagas in Icelandic that there wasn’t this clear distinction between the warrior women being mythological and the warrior men being human. When you actually look at the old Norse text, there’s a lot of words that have been translated as “men” that actually mean “people,” but it’s always been translated as “men” because it’s a warrior situation.

If you’re translating, you have to make decisions and sometimes your decisions have repercussions that you don’t expect, like writing women out of the history.

By the time Hjalmar Stolpe excavated Bj 581, he had become adept at recognizing where graves could be found in the hummocky Birka landscape. WS Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Is it possible for historians to remove all of those biases?

No, I don’t think it is. I think we all are looking through our own lenses. But we have to revisit those sources every generation to see past biases. So when you have layer after layer after layer of removing biases, you may get closer to the truth.

What most surprised you in the course of researching your book?

One of the controversies right now in Viking studies is should we really be talking about men and women at all? Maybe there were all kinds of different genders. We don’t know if there were more than two genders in the Viking age. Maybe it was a spectrum.

If you look at this one group of sagas called the Sagas of Ancient Times that are often overlooked because they have all these fabulous creatures in them, like dragons and warrior women. It’s really interesting [because] these girls grow up wanting to be warriors. They’re constantly disobeying and trying to run off and join Viking bands. But when they do run off and join the Viking band, or, in another case, become the king of a town, they insist on being called by a male name and use male pronouns.

So it was very shocking to me to go back and read it in the original and say, “Wow, all this richness was lost in the translation.”

#Nancy Marie Brown#The Real Valkyrie#Books by women#Books about women#Atlas Obscura#She Was There#Sweden#Birka#grave Bj 581#Warrior women#Vikings’ East Way

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Treated myself to a scramasax while in Scotland…

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

archaeological finds: the grave of Childeric I?

In 1653, a lavish gravesite was discovered in the Belgian town of Tournai. This site is often identified with King Childeric I.

-> Childeric I was the father of the Merovingians' "founding king" Clovis I. His reign lasted from the 450s-480s CE.

Chapter 2 of Edward James' The Franks gives a solid overview of this site's contents and what they could mean:

Its contents included belt buckles, a gold arm ring, a Roman-style fibula (a brooch for holding your cloak in place), a throwing axe, fittings for a scramasax (a shorter fighting blade, sometimes just called a saex) or sword.

These items would not out be of place in the grave of a 5th century king.

The objects this gravesite is most famous for are several small golden bees (or perhaps cicadas), which probably decorated a horse's harness. These bees were adopted by Napoleon as a symbol of the French monarchy. A lot of times you'll see these referred to as "Childeric's bees"

the bees!

Most of these contents were stolen and melted down in the 1800s, so the main evidence we have for them today are drawings done by the antiquarian Jacques Chifflet.

Chifflet's drawings of some of the grave goods: seal-ring (top left), bees + golden bulls' heads (far left and right), I could not tell you what that box or that curved object are, a spearhead (top right), fibulae (bottom left), sword fittings (surrounding a drawing of how it would look put together, bottom right)

The reason this grave is identified with Childeric I is the presence of a seal-ring containing the inscription: "CHILDERICI REGIS" ("king childeric"). This, combined with the time period these grave goods reflect, are decent evidence that the person buried at this site was Childeric I himself, or someone who was closely affiliated with him.

This is a replica of said seal-ring.

Another interesting thing is that this gravesite was near multiple horse burials, which could have been a part of Childeric's burial, or someone else at the site's. The sacrifice and burial of horses with important figures was a practice among early germanic cultures. The presence of horse burials at this site suggests that this practice was being done by the Franks in this region.

A schematic showing the location of the horse burials relative to Chilperic's grave.

This is interesting to me, because by the point of Childeric I, a lot of Frankish peoples (and certainly the Salians, who Childeric was the leader of) were quite enmeshed in Roman culture. Edward James mentions that aside from the presence of the horses, this burial is otherwise quite Roman.

If the horses were buried as a part of Childeric's funeral ritual, perhaps the Franks continued some of their Germanic cultural practices, even after adopting a more "Roman" lifestyle.

This gravesite gives a tantalizing look at the life of a more or less undocumented figure from history (he's barely mentioned outside of Gregory of Tours writings, even then Gregory was not a contemporary source). It's really tempting to say this totally WAS his grave, but there really isn't any way to be certain. But damn, it's cool.

#merovingian#frankish#medieval#late antiquity#archaeology#medieval history#french history#frankish history#history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aight! So! Futhark is pretty fekking cool! A pretty script! It had a tonne of different varieties from the various Scandinavian futharks to the continental futharks to the Anglo-Saxon furthark! Being both a linguistics student and a follower of Fyrnsida, I thought what if I could modernise the Anglo-Saxon futhark to fit my own Aussie English!!! If you don't wanna read the whole thing I have put a summary at the end of this post that you can jump down to!

SO! FIRSTLY! WHICH ANGLO-SAXON FUTHARK (or as more aptly Futhorc) SHALL I USE? There are two complete sets that we know of! These are the Thames scramasax which was a short inscription on a sword, and the Vienna Codex. While graphematically the same, they have a few graphemic/visual differences!

[Elliot, Ralph W. V. 1996. "The Runic Script." In The World's Writing Systems, edited by Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, 335-339. New York: Oxford University Press.]

I am gonna go with the Vienna Codex here just cos that is the one that the computers use so :P sorry Beagnoth- anyway! Next step was to get the phonemic transcriptions of these :D [sobs] This book gives a good overview of the readings of each of these runes, but there are some abiguities with ᚳ, and the exact qualities of some of the vowels. So my thinking is to take ᛁ/ᛇ, ᛖ, ᚪ, ᚩ, and ᚢ as the basic 5 vowel system, and then have ᛟ as /œ~ø/, ᚫ as /æ/, and have ᛠ and ᚣ be /æa/ and /y/ respectively! ᚳ I am gonna use solely as /k/, and recreate the /tʃ/ through a digraph later! It should also be noted that ᚠ /f/, ᚦ /θ/, and ᛋ /s/ are voiced medially, and that ᚷ /g/ is lenited non-initially. I quite like these so I am gonna keep that!

NOW! NEXT ORDER BUSINESS! ORTHOGRAPHY! HOW IS THIS GONNA FIT ONTO MY ENGLISH? THE MOST ANNOYING PART IS GONNA BE VOWELS! Australian English vowels are more than the ones that the Futhorc can write. So we gotta do some expanding and use some diagraphs- so I have settled on:

/ɐ/ BUD - ᚪ

/ɐ:/ BATH - ᚪᚪ

/æ/ TRAP - ᚫ

/æ:/ BAD - ᚫ (not gonna double this one as /æ/ and /æ:/ are saliently different to me but if anyone wants to use this they can double it if they want!)

/æɪ/ FACE - ᚫ��

/æɔ/ MOUTH - ᚫᚩ

/ɑɪ/ PRICE - ᚪᛁ

/e/ DRESS - ᛖ

/e:/ SQUARE - ᛖ (again, vowel length with here is not something I can hear really well?)

/ɜ:/ NURSE - ᛟ (closest modern vowel we have to /œ~ø/)

/ə/ ABOUT - ᛠ (this is just- a weird sound we, or at least I, don't use. I think it would be funky to be our schwa but! I know this is arbitrary, but I wanna try to use all of runes here)

/əʉ/ GOAT - ᛠᚢ

/ɪ/ BIT - ᛁ

/ɪə/ NEAR - ᛁᛠ

/i:/ FLEECE - ᛇ (this was used as a variant of ᛁ, and also represents a few consonants which doesnt exist in my variety today, so I am just using it for /i:/ out of a want to use all the runes)

/ɔ/ THOUGHT - ᚩ

/ɔɪ/ CHOICE - ᚩᛁ

/ʊ/ FOOT - ᚢ

/ʉ:/ GOOSE - ᚢᚢ (I know these are different vowel qualities but tbh, it isn't immediately apparent to me that they are different lest i really listen to it? So personal choice to just use this digraph here)

It was pretty easy to assign vowels to runes! All bar ᚣ, whose /y/ sound is just... not something we have anymore? But! I have an idea for it with consonant digraphs!! So let's dive into the consonants!

The standard ones

/m/ MAN - ᛗ

/n/ NOON - ᚾ

/ŋ/ KING - ᛝ

/p/ POT - ᛈ

/b/ BELLY - ᛒ

/t/ TEST - ᛏ

/d/ DOG - ᛞ

/k/ KEG - ᚳ

/g/ GIFT - ᚷ

/ks/ WEET-BIX - ᛉ

/tʃ/ CHURCH - ᛏᛋᚣ

/dʒ/ JUDGE - ᛞᛋᚣ

/f/ FAN - ᚠ

/v/ VALUE - ᚠᚻ (this digraph I am gonna use initially, I am gonna use ᚠ in non-initial positions for /v/)

/θ/ THANKS - ᚦ

/ð/ THIS - ᚦᚻ (same as with /v/)

/s/ SISTER - ᛋ

/z/ ZOO - ᛋᚻ (same as with /v/)

/ʃ/ SHELL - ᛋᚣ

/ʒ/ VISION - ᛋᚣ (I cannot think of any words outside of vision where this sound comes up, so it'll be safe to have it homographic with /ʃ/)

/h/ HOME - ᚻ

/ɹ/ RED - ᚱ

/l/ LOLLIE - ᛚ

/j/ YOUNG - ᛄ

/w/ WATER - ᚹ

Personal one

/x/ MURDOCH - my /k/ and /g/ tends to lenite at the end of words, or in fast or stressed speech non-finally - ᚳᚻ/ᚷᚻ non-finally, and ᚷ finally

So! TL:DR we have come to:

Next thing I wanna work on is making these runes more pen on paper writing friendly. The angularity of the runes was due to the materials into which they were typically carved into, and in quick writing can be a bit awkward for writing. So that is gonna me my next goal. Again! The runes were always used with degrees of variability, to match the speech of their writers. They were never standardised, and this here is not an attempt to standardised them here. This is just a personal project that others are more than free to use and modify as they wish! I will follow this up later when I replace my pen that died last night with possible handwritten styles for the runes.

#aaaaaa this was prolly vv rambly and winding I hope it was alright to read :P if anything needs to be cleared up please dont hestitate to as#wodensrambles#linguistics#grapholinguistics#runes#futhark runes#futhork#fyrnsida#heathenry

1 note

·

View note

Text

Day 3: Scramasax - Final Fantasy Tactics A2 (NDS)

1 note

·

View note

Text

10.April.24

Train’s arrival was set for clock of five, But as so late, kit is to its next life. Scream at six means hat lady is no show, So pats and snacks are, as well, a no go. Scramasax to head is felt by kit’s cry; Conductor is needed if one is nigh. Even hair-bunned gents would pass as a friend— If they shared sushi for screaming to end. Cats like not to ever wait for their care, So train for…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

作りたいものはいろいろあるけど「おれが14歳のときに本当に欲しかったもの」をやるのが一番うまくできるしモチベーションも高く持てる 何が良くて何が悪いかの基準もそれ

Xユーザーの州倉正和/scramasax⚔新作アバター出したよさん: 「作りたいものはいろいろあるけど「おれが14歳のときに本当に欲しかったもの」をやるのが一番うまくできるしモチベーションも高く持てる 何が良くて何が悪いかの基準もそれ」 / Twitter

0 notes

Photo

Finished up the straps for a friend's seax sheath! Celtic boar on the right, bindrune on the left, miscellaneous decorations everywhere else 😁 #barbaricleatherworks #leatherwork #leatherworking #handmade #viking #celt #pagan #norse #runes #bindrunes #boar #seax #scramasax #sca #reenacting #maker https://www.instagram.com/p/BnSqVk-FEj7/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=15m64srjs8on1

#barbaricleatherworks#leatherwork#leatherworking#handmade#viking#celt#pagan#norse#runes#bindrunes#boar#seax#scramasax#sca#reenacting#maker

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Single-Edged Knife (Scramasax), 600s, Cleveland Museum of Art: Medieval Art

The scramasax, a single-edged knife, was a general purpose implement. It could serve equally well as a tool or as a weapon and generally did not exceed 12 inches in length. As with most objects of the Migration period, iron weapons survive as excavated grave goods and tend to be heavily corroded. The grips, now missing, were probably fashioned from wood or bone and silver inlay decorated the pommels (the knob on the hilt, or handle). The ornamental gold foil bands, perhaps from the original scabbards (the cases in which the blades of swords or daggers are kept) have survived relatively intact. Size: Overall: 36.9 x 4.1 cm (14 1/2 x 1 5/8 in.) Medium: iron, copper, and gold foil

https://clevelandart.org/art/1919.1015

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Old Uppsala Archaeological Area, Sweden (No. 10)

The East mound, the largest of the monuments, was excavated in 1847.

Various interpretations as to dating exist. The archaeologist and professor Sune Lindqvist (1887-1976) suggested that it was erected around 500 AD, or in the early 6th century (The Migration Period), while the archaeologist John Ljungkvist places it around 550-600 AD (The Vendel Period).

The east mound is around 9 metres tall and its oval shape measures around 75 by 55 metres.

At the mounds base was a stone cairn covering a burial urn with burnt bone.

Remains of two persons

So who was buried there?

One interpretation is that it is a double grave, with two individuals. One was a boy, only 10 to 14 years old at the time of death, the other was a woman.

The reason little can be made of the osteology material is in part that the bodies were cremated, in part the most of the bone material was reinterred after excavation.

Gold and glass

Since the dead were cremated on a pyre along with the grave goods, artefacts have largely been destroyed by the fierce heat.

Examples of what nevertheless could be discerned were: ·

Thin bronze plate, possibly originally mounted on the kind of helmet known from the bout burials in Vendel and Valsgärde.

Bone gaming pieces

Remains of glass beakers

A bone comb

A small bone duck, which possibly once festooned the top of a bone needle.

Iron rivets, possibly from a casket or chest

Whetstones for sharpening knives

A object which may have been a makeup pallet

Fittings possibly from a drinking horn

Three gold objects: a piece of gold plate with filigree (thin strands and granules of gold), a piece of gold plate with animal ornaments and fittings for garnets. All three objects may have festooned a so-called scramasax, a single edge fighting knife.

Burnt and unburnt bone from a least three dogs, a hunting falcon, cattle and sheep

Bone from bear claws, suggesting that the deceased was laid out on a bear pelt.

Source

#Old Uppsala Archaeological Area#Old Uppsala Ancient Monument Area#Sverige#Gamla Uppsala högar#King's Mounds#Royal Mounds#archaeology#travel#Swedish history#Sweden#summer 2020#original photography#vacation#landscape#countryside#free admission#Uppland#Iron Age#Viking Age#flora#nature#wildflower#dark clouds#Northern Europe#Scandinavia

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

Scramasax - Ferindo o imortal Underground brasileiro

Facebook: Scramasax

YouTube: Scramasax

0 notes

Photo

Wlid Viking Scramasax 🔥 》Free Shipping 》Low Prices Buy two or more products and get amazing discounts offers FOR SALE Interested people Contact us in Inbox @zackknives5 #vikingaxe #vikings #valhalla #huntingaxe #ragnarlothbrok #ragnar #ragnarok #bojonegoro #axé #axethrowing #throwingaxes #gift #giftideas #dutch #texas #blacksmith #history #kinfeporn #damascus #steel #damascus #usa #ukraine #sweden #spain🇪🇸 #england #london🇬🇧 #canada🇨🇦 #usa🇺🇸 #germany🇩🇪 #china🇨🇳 https://www.instagram.com/p/CZkYQn9Lzz4/?utm_medium=tumblr

#vikingaxe#vikings#valhalla#huntingaxe#ragnarlothbrok#ragnar#ragnarok#bojonegoro#axé#axethrowing#throwingaxes#gift#giftideas#dutch#texas#blacksmith#history#kinfeporn#damascus#steel#usa#ukraine#sweden#spain🇪🇸#england#london🇬🇧#canada🇨🇦#usa🇺🇸#germany🇩🇪#china🇨🇳

0 notes