#Schistocerca gregaria

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Desert Locust one of the most destructive pests

(Source: Ingo Arndt)

19 notes

·

View notes

Video

Desert Locusts of London by John Wolfe Via Flickr: London Zoo, UK 2024

#Locust#Locusts#Insects#Bugs#London#animals#animal#creepy crawlies#London Zoo#Zoo#Desert Locust#desert#Schistocerca gregaria#Nikon#Travel#Zoos#Creatures#Bug#Swarm#Nikon D850#D850#flickr

1 note

·

View note

Text

Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia: vol. 2 - Insects. Written by Dr. Bernhard Grzimek. 1984.

Internet Archive

1.) Desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria)

2.) Blue-winged grasshopper (Oedipoda caerulescens)

3.) Cylindracheta sp.

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

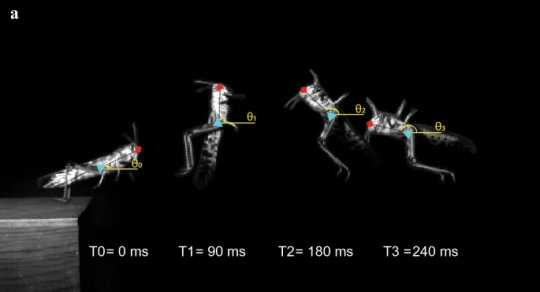

"The locust jump is composed of three phases, cocking, co-contraction and triggering."

"In the cocking phase, the tibia are fully flexed and a locking mechanism is engaged to prevent the tibia from extending prematurely.

During the co-contraction phase, the tibia extensor muscle contracts simultaneously with the flexor muscle and power is stored in the extensor apodeme, cuticle deformation, and the semi-lunar process at the femoro-tibial joint.

During the triggering phase, inhibitory neurons reduce the tension in the flexor muscle to allow the locking mechanism to disengage and release the stored energy to extend the tibia and produce the jump."

"The jump direction is determined by the orientation of the prothoracic legs as they rotate the body to point towards the target prior to the jump. The elevation of the jump is determined by the posture of the metathoracic legs."

"Because the energy budget for a grasshopper jump is constrained by the energy that is stored in the elastic processes of the limb, energy used for rotation has to come at a cost to energy used to generate linear velocity."

David Cofer, Gennady Cymbalyuk, William J. Heitler, Donald H. Edwards; Control of tumbling during the locust jump. J Exp Biol 1 October 2010; 213 (19): 3378–3387. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.046367

Goode, C.K., Sutton, G.P. Control of high-speed jumps: the rotation and energetics of the locust (Schistocerca gregaria). J Comp Physiol B 193, 145–153 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-022-01471-4

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uncharismatic Fact of the Day

Today locusts are most commonly thought of as a biblical plague, but in fact swarms of them occur almost every year in Africa, North America, Asia, and Australia. The largest swarm ever recorded occurred in Kenya in 1954; it covered 200 sq km (77 sq mi), and the population was estimated about 10 billion individuals!

(Image: A desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) by Mourad Harzallah)

If you send me proof that you’ve made a donation to UNRWA or another fund benefiting Palestinians– including esim donations and verified gofundmes– I’ll make art of any animal of your choosing.

#locusts#Orthoptera#Acrididae#swarming grasshoppers#short-horned grasshoppers#grasshoppers#insects#arthropods#uncharismatic facts

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are the Schistocerca gregaria, Locusta migratoria, Nomadacris succincta, and Anacridium sp grasshoppers/locusts still around? And, can they still become gregarious?

Oddly specific question, I was just thinking about how crazy yellow ants are the only eusocial insects in where we are in the story. But locusts are….weird.

(p.2) Well I guess locusts aren’t really *eusocial* as they don’t have a social hierarchy like ants do, but gregarious behavior still seems like a threat.

On the contrary, the ants view the grasshoppers the least of a threat of all macrovolutes! In the notes for episode 6, you can read a little on how Grasshopper Swarm is regarded as a non-Swarm, because the grasshoppers believe gathering in large numbers is bad luck...because of the locusts, yes! Locusts are certain species of grasshoppers which form devastating swarms during periods of starvation. As macrovolutes, all grasshoppers vow never to form groups that large, under any circumstances. They're anarchists, and don't fully understand how laws work when they are among insects that belong to Swarms.

And there's nothing the ants like better than a big, fat, lonely insect that has a poor grasp on laws. It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say the ants view the grasshoppers as sort of free range cattle, for when stocks of isopods and millipedes are low. Or, even when they're not.

In real life, gregarious behavior is not at all uncommon for insects, though true sociality is. You can very often find insects of the same species gathered around a food source (aphids, other true bugs, flies, roaches, etc.), or just clustered together to hibernate (e.g. ladybugs). The ants in HBG do not regard this as a threat, and in fact, the other macrovolutes were pressured to form *some* kind of social structure to convince the ants they were worth dealing with at all!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A desert locust athlete (Schistocerca gregaria) poses for photos before a minor event.

#my art#cordhan#bugs#insects\#locust#watercolor#I don't have access to a decent scanner at the moment so forgive the fuzzy and yellow tint#physical art is a lot of fun but a pain to share

1 note

·

View note

Text

these are desert locusts (Schistocerca gregaria) which are found in africa, asia and southern europe. they are one of the most common feeder insects in European reptile keeping because they are high in protein, low in fat and more popular in taste than dubias.

unlike crickets locusts are generally quiet and diurnal. they love basking under heat lamps and kicking each other. i feed mine on a variety of vegetables and fruit + some fresh leaves (beech, oak, fruit trees, bramble, ect.)

weird horses fighting over the zuchini

#locusts are some of my favourite animals tbh#i want to get them a better setup that can fit a good sized heat lamp before winter#they do really love light and heat which makes it even sadder to keep them in dingy boxes

318 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two young locusts in the pied Yemen chameleon tanks, these two are a lot more yellow and pale compared to the usuals, maybe it’s some sort of colour form like the melanistic ones? Idk I just think it’s cute how they chill and fold up their legs under the hotspot

#locust#mine#bagt post#bugblr#schistocerca gregaria#feeder locust#feel like I’ve posted a lot in a short time frame#sorry for the spam#I don’t like queueing posts that aren’t reblogs or are asks#if you want to see the chameleons they’re on my reptiblr ( bleppington )#putting it here just incase anyone doesn’t want to ask because I’m an anxious person too it’s okay

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NEW LOVELY GIRL!

Anacri, faithful messenger of the Insecta Kings, is currently taking Locust’s place in the Gregaria Temple to receive prayers from His worshippers. Anacri is beloved among the people of the Schistocerca Fields, as she’s probably the sweetest and most gentle of the Gregaria. As one of Locust’s disciples, she hopes to ascend to proper Godhood under the Insecta one day-- and many look forward to seeing it happen!

#FR#Flight Rising#Dragon Share#Shes legit one of Very few phrauge-gods that arent corrupted in some form#very very kind hearted & looks up to Locust#but her admiration is kinda faltering as she finds out more about his association w the vermin </3#im so happy w her. ive had that accent sitting in my hoard for so long its not even funny#ALSO SHES NOT ACTUALLY DONE YET LMFAO. i dont want to spend too much gem wise and a portion of her fit is gem only#Anacri

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photos by @luistatophoto. I am honored to share the powerful work of my friends and colleagues who won awards in the nature category last week of @worldpressphoto contest. Luis Tato is a photojournalist based in Nairobi, Kenya. Currently, he combines his work covering mainly East Africa as a stringer for Agence France-Presse and other international publications while developing his own photojournalism projects with a focus on sociology, identity and resilience. In this first photo, Henry Lenayasa, chief of the settlement of Archers Post, in Samburu County, Kenya, tries to scare away a massive swarm of locusts ravaging the grazing area. In early 2020, Kenya experienced its worst infestation of desert locusts in 70 years. Swarms of locusts from the Arabian Peninsula had migrated into Ethiopia and Somalia in the summer of 2019. Continued successful breeding, together with heavy autumn rains and a rare late-season cyclone in December 2019, triggered another reproductive surge. The locusts multiplied and invaded new areas in search of food, arriving in Kenya and spreading through other countries in eastern Africa. Desert locusts (Schistocerca gregaria) are potentially the most destructive of the locust pests, as swarms can fly rapidly across great distances, traveling up to 150 kilometers a day. A single swarm can contain between 40 and 80 million locusts per square kilometer. Each locust can eat its weight in plants each day: a swarm the size of Paris could eat the same amount of food in one day as half the population of France. Locusts produce two to five generations a year, depending on environmental conditions. In dry spells, they crowd together on remaining patches of land. Prolonged wet weather—producing moist soil for egg-laying, and abundant food—encourages breeding and produces large swarms that travel in search of food, devastating farmland. Border restriction necessitated by COVID-19 made controlling the locust population harder than usual, since it diverted funds, disrupted pesticide supply, and affected multiple neighboring countries already facing high levels of food insecurity. #locusts #africa #kenya #eastafrica #photojournalism #natureisspeaking (at Kenya) https://www.instagram.com/p/COJf_eIhoG7/?igshid=1xnpgaqaytgeq

1 note

·

View note

Link

Excerpt from this story from EOS, published by the American Geophysical Union:

In mid-June, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) issued a threat level warning to countries across East Africa and southwest Asia: Desert locusts (Schistocerca gregaria) are swarming. A severe outbreak that started in 2019 has spread across the Horn of Africa and the Middle East before moving on to western Asia. Scientists say climate change has played a role in this invasion.

Usually solitary, locusts become gregarious, or swarm, when there are heavy rains in an arid region. Desert locust swarms are highly destructive, sparing no greenery in sight.

This year’s locust attacks, which spread from Kenya to Pakistan and India, are the worst in the past 30 years and may be the most economically destructive since the 1960s, said Chaudhry Inayatullah, a former research scientist at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology in Nairobi, Kenya. The swarms are expected to peak this month, as a wetter-than-normal monsoon arrives, and to flourish as the rains continue through October.

Inayatullah and other locust experts fear that these attacks will only get worse. Climate change is altering the dynamics of pest control and reproduction, said Keith Cressman, the FAO’s senior locust forecaster. Changes in climate have led to increases in cyclones, which feed locust swarms with water and warmth.

Recent research also shows that human-induced warming may be intensifying a regional variability in an Indian Ocean pattern of warming and cooling called the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), sometimes nicknamed the “Indian Niño.” A more intense IOD could cause more frequent tropical storms and heavy rains. These rains create perfect conditions for locust breeding, with more water and warmth ideal for increased plant biomass to feed the locusts—which is what happened in 2019, when a record IOD led to above-average rainfall in the coastal areas of Somalia, Yemen, and some regions bordering the Red Sea.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

New models could help African countries stop locust swarms before they start

https://sciencespies.com/nature/new-models-could-help-african-countries-stop-locust-swarms-before-they-start/

New models could help African countries stop locust swarms before they start

Several countries in East Africa – namely Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, and South Sudan – are still trying to contain the worst desert locust invasion the region has experienced in over 70 years.

The locusts have destroyed vegetation – especially staple cereal crops, legumes, and pastures – resulting in huge economic losses. The World Bank estimates that these losses could reach US$8.5 billion by the end of the year.

Unlike many other grasshoppers, the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) can change from a harmless solitary phase to a destructive gregarious phase whereby hoppers (juveniles in their early, wingless stages) march together in bands.

The adults can fly and form giant swarms that can invade large areas away from their original breeding sites.

Currently, the countries are battling the second generation (or wave) of locusts, as they’ve already reproduced and hatched once within the region. And re-infestation could continue if the environment is conducive to it.

The desert locust breeds well in semi-arid zones. An ideal breeding site is characterised by warmth, vegetation close by and sandy soil with moisture and salt in it. The females usually lay their eggs at between 4 and 6 cm deep in the soil.

Governments have tried to control these insects through a range of efforts: from mobilising military units to using young people as locust cadets.

But trying to control and eliminate populations of flying locusts is expensive and not very effective. The best option, proved by scientists, is to manage them at their breeding sites.

Eggs survive and hatch when the environmental conditions are right – they can hatch within weeks or remain undeveloped for years. They’re laid inside soil so can be hard to find; it’s best that control measures – preferably biopesticides – are used when the locusts are at the surface in the form of a nymph or hopper.

For this to happen, targeted ground and aerial surveillance efforts to identify potential breeding sites are critical.

The most destructive locust swarm in East Africa happened over 70 years ago. Documentation of information was very poor, and so there was no prior knowledge of the region’s potential breeding sites.

Along with my colleagues from the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology, I’m trying to fill this gap. We’ve developed maps that predict where desert locusts could breed in Kenya, Uganda, and South Sudan.

Our model, supported by a machine learning algorithm, establishes a relationship between historical data from around the world on desert locust breeding sites.

It also factors in climate and soil characteristics that are necessary for locusts to lay their eggs, and for the eggs to hatch.

Breeding sites can consist of anywhere between 40 to 80 million locusts within a square kilometre.

There is a need to target these high-risk areas and strengthen ground surveillance to manage the locusts in a timely, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly manner.

At-risk areas

Using the model, we’ve identified and mapped potential breeding regions of the desert locust in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan.

Vast areas in Kenya are at high risk because they have the right conditions to support locust breeding. These areas include Mandera, Wajir, Garissa, Marsabit, Turkana (all counties in North Eastern Kenya), and a few sites in Samburu county.

In Uganda, there are fewer possible breeding sites than in Kenya. These are restricted to the north-eastern regions, specifically Kotido, Kaabong, Moroto, Napak, Abim, Kitgum, Moyo, and Lamwo districts.

South Sudan is at risk of breeding in the northern regions and the south-east corner bordering Kenya. These sites exist in northern Bahr el Ghazal, Unity, Upper Nile, Eastern Equatoria, Warrap, Lakes, and some parts of Jonglei state.

Actions

In line with these predictions, ground and aerial surveillance efforts and monitoring of weather and vegetation variables in the predicted breeding regions needs to be strengthened significantly.

Financial, material and human resources will also need to be mobilised for timely management of the hopper bands when they emerge.

We, at the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology, have several suggestions on what must happen next:

Due to a large area for potential breeding of locusts, a permanent locust monitoring unit in Kenya must be established. It should consist of ground and aerial surveillance teams, locust biologists, socio-economists, remote-sensing experts and weather and vegetation forecasters.

A task force must be set up in Uganda to collaborate with Kenya’s monitoring unit. Based on the overall cover area of desert locust breeding suitability in Uganda, it may not be necessary to invest in constant monitoring in the country.

But the task force must collaborate closely with the Kenyan Locust monitoring unit and enhance preparedness for possible outbreaks and swarms.

Sustainable locust management interventions and associated mobilisation of financial, logistical and human resources need to be closely linked with strengthened locust monitoring efforts.

There must be a greater focus on sustainable and biological control options against locusts to mitigate adverse impacts of chemical pesticide-based locust control strategy.

We believe that biopesticide applications should become a cornerstone in managing locust outbreaks. Biopesticides need to be rapidly field tested in Kenya, commercialised and scaled up.

Finally, the current desert locust outbreak is triggered by a change in rainfall pattern which expands areas of potential invasion as a consequence of climate variability or change.

It is possible that, in future, other marginally suitable areas and conditions may become conducive for locust breeding.

Therefore, it is important to ramp up modelling efforts to understand the potential impacts of climate change on the current model predictions.

Henri Tonnang, Research Scientist, International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

#Nature

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Delle locuste non ci frega niente. Per adesso di Alessandro Giglioli Se abbiamo un momento per distrarci da Bugo, dagli ultimatum di Renzi e dall'ultima dichiarazione delle Sardine, forse potremmo accorgerci di qualcosa che impatterà (anche) sulle nostre vite un filo di più: la spaventosa invasione delle locuste in Africa orientale - e non solo lì. Quando si parla di cavallette solitamente in Europa vengono in mente due cose: le piaghe della Bibbia e il celebre sketch di John Belushi nei Blues Brothers. Se invece vi fosse capitato di viaggiare in Africa orientale negli ultimi mesi - già da ottobre - delle locuste avreste sentito parlare da tutti - oh tutti - i contadini incontrati nei villaggi e nei campi. Naturalmente i contadini non li ascolta nessuno, specie nelle zone del pianeta poco coperte dai media (fossimo stati nel midwest americano già la cosa sarebbe stata diversa) sicché si è dovuto aspettare che la tragedia fosse totale perché qualcuno si accorgesse di quello che stava succedendo: probabilmente la peggiore catastrofe agricola della storia moderna. Attualmente la calamità ha il suo epicentro nel Corno d'africa - Kenya, Etiopia, Eritrea e Somalia - ma coinvolge da sud a nord una fascia d'Africa orientale che va dal Mozambico all'Egitto, passando per Tanzania, Uganda, Sud Sudan e Sudan, e si trascina verso oriente colpendo la penisola arabica e l'Iran, fino a risalire nella vasta area di confine tra Pakistan e India, compresa tutta la fertile pianura del Punjab. Stiamo parlando di una cosa tra i 100 e i 200 miliardi di esemplari di Schistocerca gregaria, i cui sciami sono in grado di divorare quasi due milioni di tonnellate di vegetazione al giorno in un'area di 350 chilometri quadrati. Non è ancora calcolabile quanti milioni di persone potrebbero essere alla fame nei prossimi mesi a causa della distruzione dei raccolti, anche perché molto dipende dall'evoluzione della situazione climatica. Il clima, appunto. (...) certo è che l'Africa orientale ha subito l'anno scorso due cicloni consecutivi che hanno lasciato sgomenti i meteorologi, così come indiscutibile è che l'usuale alternanza di stagione secca e umida da quelle parti si sia gradualmente modificata negli ultimi vent'anni, con un drammatico prolungamento della prima seguita da una stagione delle piogge molto più breve ma anche molto più violenta. Se si parla con i contadini - che certo scienziati non sono, ma hanno un'esperienza diretta - queste alterazioni del clima emergono subito, così come la convinzione che ci sia un rapporto causale diretto tra il clima impazzito e l'invasione delle cavallette. In ogni caso la tragedia umanitaria è già in corso, anche se per ora è lontana da noi, che ci occupiamo quindi di Bugo. Tuttavia il mondo è diventato piuttosto piccolo, ultimamente, sicché con ogni probabilità presto qualche altro milione di africani e forse di indiani busserà per fame alle nostre porte, in Europa, anche per i possibili conflitti armati che spesso scoppiano quando i raccolti non ci sono più. Salvini ne sarà contento (suppongo che tifi per gli ortotteri, visto il vantaggio politico che potrà trarne quando arriveranno i barconi), noi staremo qui a discutere se saranno profughi di guerra o economici o climatici spaccando ridicolmente il capello in quattro - e pochi si chiederanno se l'esplosione delle locuste non sia anche effetto del nostro mondo ricco che per consumismo e incuria ha cambiato e continua a cambiare il clima del pianeta, cavallette comprese.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Male american bird grasshopper (Schistocerca americana). Florida, 12/27/18.

This guy is a very close relative of the infamously devastating desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria). Like its old world cousin, it sometimes exhibits population booms, but nothing close to the biblical migratory swarms of S. gregaria.

North America did also once have its own swarming grasshopper, the rocky mountain locust (Melanoplus spretus). Just like desert locusts of Africa and Asia and other species found in Australia, hordes of them ate entire farms to the ground in the western US. Just a few decades after it was responsible for the largest locust swarm in recorded history, it apparently went extinct, possibly due to agricultural activity disrupting the areas where they bred between swarm cycles.

(Not my photo. Taken in the 1870’s when they still existed.)

It is possible that the species still exists. Swarming in locusts is typically caused by conditions that favor high population densities, which triggers young grasshoppers to develop different physical features and behavior. For instance, desert locusts are green in their solitary phase but turn black and yellow when they swarm, and develop longer wings for sustained flight.

(Swarming and non- swarming desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) nymphs. Not my photo.)

So it has been theorized that the rocky mountain locust is not totally extinct, but continues to exist disguised as a more ordinary Melanoplus grasshopper that simply no longer experiences the conditions necessary to induce swarming. Yet so far, rearing experiments and genetic testing have failed to unmask any such beast.

Two- striped grasshopper (Melanoplus bivittatus): a mild- mannered relative of the (possibly) extinct rocky mountain locust.

161 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Desert Locust (Schistocerca gregaria). Source: BBC Earth.

0 notes