#Sarah Franklin Bache

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Sarah Franklin Bache (September 11, 1743 – October 5, 1808), sometimes known as Sally Bache, was the daughter of Benjamin Franklin and Deborah Read. She was a leader in relief work during the American Revolutionary War and frequently served as her father's political hostess, like her mother before her death in 1774. Sarah was also an important leader for women in the pro-independence effort in Philadelphia. She was an active member of the community until her death in 1808.

When Sarah was born in 1743, Benjamin Franklin was thirty-seven and intently focused on furthering his career and wealth. Growing up, Sarah did not have a very close relationship with her father. Franklin's reserved nature towards his daughter may have been partially due to the previous loss of Francis. But Franklin was also deep into his experimentation with electricity by the time Sarah was a young child, and by her early teenage years, he had left for Europe.

Franklin would begin to consider men and women as more intellectually equal later in his life, but he did not take this approach to his own children and grandchildren. It was not unusual for men during this time to take a more aloof approach towards their daughters' education than towards their sons' education. Daughters were typically given the education they would need to be good housewives as that would be their most important job. The education Sarah received was thus typical for women of her status during the 18th century. She was taught reading, writing and arithmetic, as well as spinning, knitting, and embroidery. Franklin also had Sarah enrolled in dance school. When Franklin traveled to Europe in Sarah's early adolescence, he left Deborah Read to take care of the "Education of my dear child." It is also possible that Sarah learned French. Benjamin Franklin once gave Sarah a copy of Samuel Richardson's Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded in a French translation to "help her with her French. She must have already read it in English."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Collection of Revolutionary War Statements Mentioning People Getting Struck by Lightning

"Diary of Lieutenant James McMichael 1776-1778"

"Extracts from the Journal of John Bell Tilden 1781-1782"

"John Adams to Abigail Adams 7 July 1776"

"William Heath to George Washington 29 November 1782"

"Sarah Bache to Benjamin Franklin [notes] 7 January 1783"

"John Thaxter to John Adams 12 August 1783"

"John Adams Diary Friday February 20"

"Edward Nairne to Benjamin Franklin 14 August 1783"

#amrev history#history#amrev#lightning#apparently it was really common#Benjamin Franklin#John Adams#Abigail Adams#John Thaxter#James McMichael#John Bell Tilden#William Heath#George Washington#Sarah Bache#Edward Nairne

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Do not allow people to dim your shine because they are blinded. Tell them to put on some sunglasses, cuz we were born this way, 🤬!” -Lady Gaga @ladygaga Unapologetic, and ready to seize any opportunity this fiery sign is ruled by the God of War #Aries (or #mars), and restarts the cosmic wheel leading us into spring (the vernal equinox). So, happy birthday to all you spring chickens which includes: Jackie Chan Charlemagne Leonardo da Vinci & Vincent van Gogh & Skottie Young Keegan-Michael Key & Tig Notaro Johann Sebastian Bach Emma Watson & Anya Taylor-Joy & Jessica Chastain & Sarah Michelle Gellar Aretha Franklin & Elton John Tim Curry & Pedro Pascal Maya Angelou & Beverly Clearly & Robert Frost Jane Goodall & Wilhelm Rontgen Joseph Pulitzer Andrew Lloyd Webber & Stephen Sondheim Francis Ford Coppola & Edgar Wright Kareem Abdul-Jabbar & Peyton Manning …and so many, many, many more...lots of actors under this sign. As for the origin tale…. In their tale of ascension, #Chrysomallus is sent by the nymph #Nephele to rescue her children #Phrixus & #Helle from being sacrificed to Zeus by their stepmother #Ino in order to end the blight devastating the land. Sadly Helle does not survive the tale, but lives on as commemorated by the #Hellesport a strait bearing her name. Phrixus is brought to #Colchis (modern-day country of Georgia), and then sacrifices the ram to Zeus, while placing the fleece in a grove sacred to the war God Aries. It will reside here undisturbed until revisited in the story of Jason and the Argonauts. #astrology #horoscope #vectorart #adobeillustrator #adobephotoshop #artist #art #illustration #illustrator #illustratorsoninstagram #digitalart #digitalartist #digitalillustration #digitalpainting #design #designer #orangecountyart #orangecountyartist #losangelesart #losangelesartist #stilesofart @adobe @photoshop @_adobeillustrator_ @jackiechan @skottieyoung @keeganmichaelkey @emmawatson @anyataylorjoy @jessicachastain @sarahmgellar @arethafranklin @eltonjohn @pascalispunk @drmayaangelou @janegoodallinst @realsondheim @coppolawine @edgarwright @kareemabduljabbar_33 @peytonmanning https://www.instagram.com/p/CqA2GiwLlz5/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#aries#mars#chrysomallus#nephele#phrixus#helle#ino#hellesport#colchis#astrology#horoscope#vectorart#adobeillustrator#adobephotoshop#artist#art#illustration#illustrator#illustratorsoninstagram#digitalart#digitalartist#digitalillustration#digitalpainting#design#designer#orangecountyart#orangecountyartist#losangelesart#losangelesartist#stilesofart

1 note

·

View note

Text

“For the Truth the Turkey is in Comparison a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America… He is besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.”

Benjamin Franklin to Sarah Bache, January 26, 1784

The American Revolution Institute, Smithsonian Magazine

0 notes

Photo

It’s a 4th of July Feathursday!!

And what better way to celebrate than with an image of our national avian avatar, the American Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), represented here by a four-color offset lithographic reproduction of a painting by American wildlife artist James Lockhart from his folio volume Portraits of Nature, published in New York by Crown Publishers in 1967. The Bald Eagle made its first appearance as our national symbol on the official seal of the United States. Being at war with Great Britain at the time, this fierce-looking bird seemed a fitting representation of a young, steadfast nation, and so on June 20, 1782, Congress approved the seal’s design with the Bald Eagle that we recognize today.

However, Benjamin Franklin, one of the committee members tasked with selecting a design for the national seal, frowned on the choice, much preferring the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) as a more suitable emblem (represented here by another Lockhart image from the same volume). In a letter to his daughter Sarah Franklin Bache, that he drafted on January 26, 1784, but never sent, Franklin wrote:

For my own part I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character. He does not get his living honestly. You may have seen him perched on some dead tree, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the labour of the fishing hawk; and when that diligent bird has at length taken a fish, and is bearing it to his nest for the support of his mate and young ones, the Bald Eagle pursues him, and takes it from him. With all this injustice, he is never in good case, but like those among men who live by sharping and robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank coward: the little King Bird not bigger than a sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the district. He is therefore by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest Cincinnati of America, who have driven all the King Birds from our country. . . . For in truth, the Turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird, and withal a true original native of America. . . . He is besides, (though a little vain and silly tis true, but not the worse emblem for that) a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his farm yard with a red coat on.

Congress clearly did not agree. Still, although both birds are indeed native only to the Americas, the United States cannot make an exclusive claim to either, as the ranges of both extend to Canada and Mexico as well.

View other images from this volume.

View more Feathursday posts.

#Feathursday#fourth of july#holidays#bald eagles#wild turkeys#Benjamin Franklin#Sarah Franklin Bache#James Lockhart#Portraits of Nature#offset lithographs#national symbols#United States#birds#birbs!#4th of July#July 4th#Independence Day

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Esther deBerdt Reed

Some Facts about one of my favorite historical figures.

-She was born in 1746 in London but moved to Philadelphia following her marriage to Joseph Reed in 1770.

- During the American war of Independence, she was forced to flee several times from the British.

-She became Pennsylvania's First Lady, in 1778, following her husband's election as President of the Supreme Executive Council.

-In June 1780, she published "The Sentiments of an American woman", in which she argued although women were not permitted the use of weapons, they still were capable of participating in the fight for independence, citing various examples of women's contribution to warfare, ranging from biblical heroines to ancient roman women to contemporary female sovereigns.

She proposed women should renounce spending money on luxurious clothing and instead give it to soldiers, as an expression of gratitude and remembrance, which would serve for the relief and encouragement of the soldiers.

(I've included a link to the whole text below)

-A few days later, the Ladies Association of Philadelphia, followed by similar organizations in other states, was founded. Their goal was to raise money and send it as quickly as possible, to the continental soldiers. Every county should appoint a treasuress, who would send the collected money to her state's leading lady, who would send it to Martha Washington, who should distribute the money to the soldiers when she was at camp or her husband, if she was absent.

-On the 4th of July, 300,634 $ in Paper Money had been collected.

-As Martha Washington was absent from camp, Reed wrote to General Washington about the distribution of the money, but he proposed that instead of giving soldiers hard money, the money should be used for buying shirts or deposited at a Bank. Reed and her comrades opposed this, as they wanted to give the soldiers a gift for free use and not something they were owed. Later they agreed to sew shirts with each lady stitching her name on the shirt.

Unfortunately, she died on the 18th of September 1780, aged 34, but her position was taken by Sarah Franklin Bache and 2200 shirts were delivered to the Army.

Fun Fact: On the 1st of January 1781, the Pennsylvania Line soldiers mutinied, because they had not received pay.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mrs. Richard Bache (Sarah Franklin, 1743–1808), John Hoppner, 1793, European Paintings

Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1901 Size: 30 1/8 x 24 7/8 in. (76.5 x 63.2 cm) Medium: Oil on canvas

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436686

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deadly Secrets

read it on AO3 at https://ift.tt/3aHs8RX

by Lilyintin89

Abraham Woodhull is a cabbage farmer with a huge secret, Not everyone in Setauket knows about his secret except for a little group of spies, the truth is that Abraham Woodhull is pregnant with Benjamin Tallmadge's child, Benjamin is a military officer who fights along side caleb brewster, aka Abe's over protective friend, it's the revolutionary war, feelings are at stake, and with Abraham pregnant with Benjamin's child Benedict doesn't know if the child is even Benjamin's child or his child, Abraham doesn't know who the real father is, he's for certain it's benedict's child, but on the inside he's also certain that it could be Benjamin's child as well, or maybe they're both the fathers, who knows.

Abe is a male carrier, Robert Townsend is his bounder, a bounder is someone who swears to protect a carrier at all coast no matter what happens to the fathers or father. Can robert keep abe's secret?, or will they have to escape from setauket and run off to some other place?. How will Benjamin and Benedict take the news of the unborn child?, will they keep it?, read to find out what happens!.

Words: 1111, Chapters: 1/?, Language: English

Series: Part 1 of Pregnant Revolutionaries

Fandoms: Hamilton - Miranda, Alexander Hamilton - Ron Chernow, Turn (TV 2014), founding fathers - Fandom, Culper Spy Ring - Fandom, 17th Century CE RPF, 18th Century CE RPF, John Adams (TV)

Rating: Explicit

Warnings: Graphic Depictions Of Violence, Major Character Death, Rape/Non-Con

Categories: F/F, F/M, M/M, Multi

Characters: Alexander Hamilton, John Laurens, Gilbert du Motier Marquis de Lafayette, Hercules Mulligan, Aaron Burr, Elizabeth "Eliza" Schuyler, Margaret "Peggy" Schuyler, Angelica Schuyler, Maria Reynolds, Henry Laurens (1723-1792), Dolley Madison, George Eacker, John Adams, Frances Laurens, Theodosia Burr Alston, George III of the United Kingdom, Martha Washington, Theodosia Prevost Burr, Charles Lee, Philip Hamilton, Sarah Churchill Duchess of Marlborough, Woodes Rogers, Robert Troup, John Hancock (1737-1793), Abigail (Turn), David Hosack (1769-1835), Mary Floyd Tallmadge, George Washington, Thomas Lynch Jr, Becky Redman, Edward Sexby, Mary Graves (1772-1860), Karl Eugen von Württemberg, Captain Joyce, Thomas "Sprout" Woodhull, Benedict Arnold, Martha Laurens Ramsay, Alexander Hamilton Jr., Tench Tilghman, Jules Mazarin, Thomas Conway (1735-c.1800), Anna Ivanovna | Anna of Russia, Dr. Mabbs, Galileo Galilei, Hamilton Ensemble, Johann Sebastian Bach, Samuel Seabury (1729-1796), Tailor, Samuel "Black Sam" Bellamy, Anne Hyde Duchess of York, William "Billy" Lee (Turn), Robert Townsend (1753-1838)

Relationships: Alexander Hamilton/Elizabeth "Eliza" Schuyler, Alexander Hamilton/John Laurens, Aaron Burr/Theodosia Prevost Burr, Thomas Jefferson/James Madison, Maria Reynolds/Elizabeth "Eliza" Schuyler, Aaron Burr/Alexander Hamilton, Charles Lee/Samuel Seabury, Martha Manning/Elizabeth "Eliza" Schuyler, Henry Clay/John C. Calhoun, Benjamin Franklin/Henry Knox, Gilbert du Motier Marquis de Lafayette/Hercules Mulligan, Gilbert du Motier Marquis de Lafayette/George Washington, John Barker Church/Angelica Schuyler, Abraham Woodhull/Mary Woodhull, Benedict Arnold/Benjamin Tallmadge/Abraham Woodhull, Robert Townsend/Abraham Woodhull, John André/Abraham Woodhull, Caleb Brewster/Anna Strong/Benjamin Tallmadge/Abraham Woodhull, Thomas Jefferson/Angelica Schuyler, Margaret "Peggy" Schuyler & Stephen Van Rensselaer (1764-1839), George III of the United Kingdom/John Laurens, Maria Cosway/Thomas Jefferson, Edmund Hewlett/John Graves Simcoe, Anna Strong/Mary Woodhull, Anna Strong/Selah Strong, Benedict Arnold/Charles Lee, George III of the United Kingdom/Charles Lee/Samuel Seabury, George III of the United Kingdom/George Washington, George Washington/Martha Washington

Additional Tags: Pregnancy, Revolutionary War, LGBTQ Themes, Strong Female Characters, Gay Founding Fathers (Hamilton), Hurt/Comfort, Cuddling & Snuggling, Naked Cuddling, Canon-Typical Violence, War, Eventual Smut, Rape/Non-con Elements, Slow Build, Bisexual Alexander Hamilton, Minor Alexander Hamilton/Elizabeth "Eliza" Schuyler, Mom Friend Angelica Schuyler, Gay John Laurens, Minor Anna Strong/Abraham Woodhull, John Simcoe Being an Asshole, The Battle of Setauket, Light-Hearted, Light BDSM, Religious Conflict, Character Death, Major Character Injury, Slash, Protectiveness, Attempted Rape/Non-Con, Male Pregnancy, 17th Century, Torture, Spoilers, Prompt Fill, Royalty, Rough Sex, Neck Kissing, Praise Kink, Love, Drunken Confessions, Falling In Love, Long-Distance Relationship, Attempted Murder, Painful Sex, Romantic Soulmates, Established Relationship, Implied/Referenced Suicide, Self-Harm, Abraham Woodhull Needs A Hug, Porn, Alternate Universe, Everyone Needs A Hug, Henry Laurens' A+ Parenting, Internalized Homophobia, Homophobic Language

read it on AO3 at https://ift.tt/3aHs8RX

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Do you have any liberty’s kids headcanons?

I have had a few thoughts along the lines of daydreams/fanfic/what I’d want in a live action reboot if we ever got one.

I can tell you that James, Sarah, and Henri wrote each other extensively on their travels to different battle sites and events. So even though they were apart a lot of the time, they still got to know each other in writing. James and Sarah had to suffer through Henri’s poor English spelling. Doctor Franklin and Moses also wrote each other and the kids frequently. (Before the days of internet of course snail mail was the way to go)

After Lafayette joined the Continental Army, he and Henri would write each other, and that way Henri was able to master reading and writing in French. I’m not saying Ben Franklin was thinking of Henri when he recruited Lafayette but

Whenever Sarah was travelling with James and/or Henri she was constantly mending their clothes–James knew how to sew a little but he wasn’t nearly as good at it as Sarah, and she would tell him off for his stitches being sloppy. “Did you mend that yourself? It looks awful! No wonder it’s falling apart! Let me do it.”

Sarah would have known Peggy Shippen–Peggy was only a couple of years older than Sarah and probably would have provided a circle of lady friends/Tory friends for her to be with during her early teen years in America.

Sarah kept up a correspondence with Benedict Arnold from 1775 until Arnold became military gov. of Philadelphia in 78. (He was really impressed with her report on his involvement at Fort Ticonderoga–poor guy didn’t get much good press for that event). She was able to indirectly report on his campaigns in Canada and on Lake Champlain for the Gazette. And out of habit they kept writing afterward.

(Fun history fact while building his Lake Champlain fleet Arnold wrote an article from a soldier’s POV about the Continental Army’s activity there and he sent it–I kid you not–to the Pennsylvania Gazette. In the Liberty’s Kids universe it makes perfect sense he would send it there)

While Arnold was governor of Philadelphia, Sarah was on the scene of Arnold’s courtship of Peggy Shippen and part of her couldn’t understand why they were so into each other. Sarah keeps his letters when she goes back to England but loses them when her ship sinks and she’s rescued by John Paul Jones. After Sarah got back to America in 1780 she wrote to Arnold and Peggy several times. Peggy sent her one or two cordial responses while Arnold never replied–Peggy had just had a baby and Arnold was busy being a traitor. :(

Sarah was also pen pals, of course, with Abigail Adams. Come to think of it, she would have been at least acquainted with other leading women of the revolution, for example Martha Washington and Ben Franklin’s daughter Sarah Bache.

James also had a really tight relationship with Alexander Hamilton and they wrote each other through the war years and after. Of course Hamilton would not have minded another pen pal, or a friend for that matter.

After returning to France after the Revolution, Lafayette got Henri enrolled in a university in Paris, and Henri was an activist in the years leading up to the French Revolution. Although Henri was involved in Lafayette’s more conservative Feuillant faction and would have been targeted by the Jacobins during the Terror, he was able to get out of Paris and keep his head down during the worst of it.

About 1799-1800 James and Sarah (now a married couple) go to England to visit friends and family, and they go over to France to meet with Henri and Lafayette, who had just returned from exile.

I’m happy to share more as they come up.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

What do you think a bald eagle did to Benjamin Franklin for him to think that all bald eagles are of bad moral character?

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-41-02-0327

0 notes

Text

What Led Benjamin Franklin to Live Estranged From His Wife for Nearly Two Decades?

A stunning new theory suggests that a debate over the failed treatment of their son’s smallpox was the culprit

— By Stephen Coss | Smithsonian Magazine | September 2017

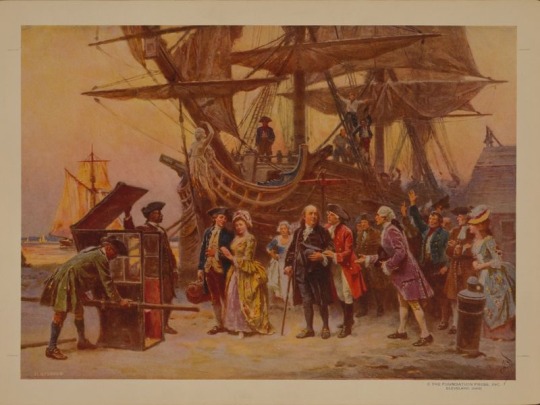

A painting of Franklin’s return to Philadelphia from Europe in 1785 shows him flanked by his son-in-law (in red), his daughter and Benjamin Bache (in blue), the grandson he’d taken to France as a sort of surrogate son. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

In October 1765, Deborah Franklin sent a gushing letter to her husband, who was in London on business for the Pennsylvania legislature. “I have been so happy as to receive several of your dear letters within these few days,” she began, adding that she had read one letter “over and over.” “I call it a husband’s Love letter,” she wrote, thrilled as though it were her first experience with anything of the kind.

Perhaps it was. Over 35 years of marriage, Benjamin Franklin had indirectly praised Deborah’s work ethic and common sense through “wife” characters in his Pennsylvania Gazette and Poor Richard’s Almanac. He had celebrated her faithfulness, compassion and competency as a housekeeper and hostess in a verse titled “I Sing My Plain Country Joan.” But he seems never to have written her an unabashed expression of romantic love. Whether the letter in question truly qualified as his first is unknown, since it has been lost. But it’s likely that Deborah exaggerated the letter’s romantic aspects because she wanted to believe her husband loved her and would return to her.

That February Franklin, newly arrived in London, had predicted that he would be home in “a few Months.” But now he had been gone for 11, with no word on when he would come back. Deborah could tell herself that a man who would write such a letter would not repeat his previous sojourn in England, which had begun in 1757 with a promise to be home soon and dragged on for five years, during which rumors filtered back to Philadelphia that he was enjoying the company of other women. (Franklin denied it, writing he would “do nothing unworthy the Character of an honest Man, and one that loves his Family.”) But as month after month passed with no word on Benjamin’s voyage home, it became clear that history was repeating itself.

This time Franklin would be gone for ten years, teasing his imminent return almost every spring or summer and then canceling at nearly the last minute and without explanation. Year after year Deborah stoically endured the snubbing, even after she had a stroke in early spring 1769. But as her health declined, she gave up her vow not to give him “one moment’s trouble.” “When will it be in your power to come home?” she asked in August 1770. A few months later she pressed him: “I hope you will not stay longer than this fall.”

He ignored her appeals until July 1771, when he wrote her: “I purpose it [his return] firmly after one Winter more here.” The following summer he canceled again. In March and April 1773 he wrote vaguely of coming home, and then in October he trotted out what had become his stock excuse, that winter passage was too dangerous. In February 1774, Benjamin wrote that he hoped to return home in May. In April and July he assured her he would sail shortly. But he never came. Deborah Franklin suffered another stroke on December 14, 1774, and died five days later.

We tend to idealize our founding fathers. So what should we make of Benjamin Franklin? One popular image is that he was a free and easy libertine—our founding playboy. But he was married for 44 years. Biographers and historians tend to shy away from his married life, perhaps because it defies idealization. John and Abigail Adams had a storybook union that spanned half a century. Benjamin and Deborah Franklin spent all but two of their final 17 years apart. Why?

The conventional wisdom is that their marriage was doomed from the beginning, by differences in intellect and ambition, and by its emphasis on practicality over love; Franklin was a genius and needed freedom from conventional constraints; Deborah’s fear of ocean travel kept her from joining her husband in England and made it inevitable that they would drift apart. Those things are true—up to a point. But staying away for a decade, dissembling year after year about his return, and then refusing to come home even when he knew his wife was declining and might soon die, suggests something beyond bored indifference.

Franklin was a great man—scientist, publisher, political theorist, diplomat. But we can’t understand him fully without considering why he treated his wife so shabbily at the end of her life. The answer isn’t simple. But a close reading of Franklin’s letters and published works, and a re-examination of events surrounding his marriage, suggests a new and eerily resonant explanation. It involves their only son, a lethal disease and a disagreement over inoculation.

**********

As every reader of Franklin’s Autobiography knows, Deborah Read first laid eyes on Benjamin Franklin the day he arrived in Philadelphia, in October 1723, after running away from a printer’s apprenticeship with his brother in Boston. Fifteen-year-old Deborah, standing at the door of her family’s house on Market Street, laughed at the “awkward ridiculous Appearance” of the bedraggled 17-year-old stranger trudging down the street with a loaf of bread under each arm and his pockets bulging with socks and shirts. But a few weeks later, the stranger became a boarder in the Read home. After six months, he and the young woman were in love.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania’s governor, William Keith, happened upon a letter Franklin had written and decided he was “a young Man of promising Parts”—so promising that he offered to front the money for Franklin to set up his own printing house and promised to send plenty of work his way. Keith’s motives may have been more political than paternal, but with that, the couple “interchang’d some Promises,” in Franklin’s telling, and he set out for London. His intention was to buy a printing press and type and return as quickly as possible. It was November 1724.

Nothing went as planned. In London, Franklin discovered that the governor had lied to him. There was no money waiting, not for equipment, not even for his return passage. Stranded, he wrote Deborah a single letter, saying he would be away indefinitely. He would later admit that “by degrees” he forgot “my engagements with Miss Read.” In declaring this a “great Erratum” of his life, he took responsibility for Deborah’s ill-fated marriage to a potter named John Rogers.

But the facts are more complicated. Benjamin must have suspected that when Sarah Read, Deborah’s widowed mother, learned that he had neither a press nor guaranteed work, she would seek another suitor for her daughter. Mrs. Read did precisely that, later admitting to Franklin, as he wrote, that she had “persuaded the other Match in my Absence.” She had been quick about it, too; Franklin’s letter reached Deborah in late spring 1725, and she was married by late summer. Benjamin, too, had been jilted.

Just weeks into Deborah’s marriage, word reached Philadelphia that Rogers had another wife in England. Deborah left him and moved back in with her mother. Rogers squandered Deborah’s dowry and racked up big debts before disappearing. And yet she remained legally married to him; a woman could “self-divorce,” as Deborah had done in returning to her mother’s home, but she could not remarry with church sanction. At some point she was told that Rogers had died in the West Indies, but proving his death—which would have freed Deborah to remarry formally—was impractically expensive and a long shot besides.

Franklin returned to Philadelphia in October 1726. In the Autobiography he wrote that he “should have been...asham’d at seeing Miss Read, had not her Friends...persuaded her to marry another.” If he wasn’t ashamed, what was he? In classic Franklin fashion, he doesn’t say. Possibly he was relieved. But it seems likely, given his understanding that Deborah and her mother had quickly thrown him over, that he felt at least a tinge of resentment. At the same time, he also “pity’d” Deborah’s “unfortunate Situation.” He noted that she was “generally dejected, seldom cheerful, and avoided Company,” presumably including his. If he still had feelings for her, he also knew that her dowry was gone and she was, technically, unmarriageable.

He, meanwhile, became more eligible by the year. In June 1728, he launched a printing house with a partner, Hugh Meredith. A year later he bought the town’s second newspaper operation, renamed and reworked it, and began making a success of the Pennsylvania Gazette. In 1730 he and Meredith were named Pennsylvania’s official printers. It seemed that whenever he decided to settle down, Franklin would have his pick of a wife.

Then he had his own romantic calamity: He learned that a young woman of his acquaintance was pregnant with his child. Franklin agreed to take custody of the baby—a gesture as admirable as it was uncommon—but that decision made his need for a wife urgent and finding one problematic. (Who that woman was and why he couldn’t or wouldn’t marry her remain mysteries to this day.) No desirable young woman with a dowry would want to marry a man with a bastard infant son.

But Deborah Read Rogers would.

Thus, as Franklin later wrote, the former couple’s “mutual Affection was revived,” and they were joined in a common-law marriage on September 1, 1730. There was no ceremony. Deborah simply moved into Franklin’s home and printing house at what is now 139 Market Street. Soon she took in the infant son her new husband had fathered with another woman and began running a small stationery store on the first floor.

Benjamin accepted the form and function of married life—even writing about it (skeptically) in his newspaper—but kept his wife at arm’s length. His attitude was reflected in his “Rules and Maxims for Promoting Matrimonial Happiness,” which he published a month after he and Deborah began living together. “Avoid, both before and after marriage, all thoughts of managing your husband,” he advised wives. “Never endeavor to deceive or impose on his understanding: nor give him uneasiness (as some do very foolishly) to try his temper; but treat him always beforehand with sincerity, afterwards with affection and respect.”

Whether at this point he loved Deborah is difficult to say; despite his reputation as a flirt and a charmer, he seldom made himself emotionally available to anyone. Deborah’s famous temper might be traced to her frustration with him, as well as the general unfairness of her situation. (Franklin immortalized his wife’s fiery personality in various fictional counterparts, including Bridget Saunders, wife of Poor Richard. But there are plenty of real-life anecdotes as well. A visitor to the Franklin home in 1755 saw Deborah throw herself to the floor in a fit of pique; he later wrote that she could produce “invectives in the foulest terms I ever heard from a gentlewoman.”) But her correspondence leaves no doubt that she loved Benjamin and always would. “How I long to see you,” she wrote to him in 1770, after 40 years of marriage and five years into his second trip to London. “If you’re Having the gout...I wish I was near enough to rub it with a light hand.”

“We throve together,” Franklin wrote of his wife (right) in his autobiography, which he began at age 65. But he did not mention the birth of their son, Francis (left). (Left: Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo; Right: Public Domain)

Deborah Franklin wanted a real marriage. And when she became pregnant with their first child, near the beginning of 1732, she had reason to hope she might have one. Her husband was thrilled. “A ship under sail and a big-bellied Woman, / Are the handsomest two things that can be seen common,” Benjamin would write in June 1735. He had never been much interested in children, but after the birth of Francis Folger Franklin, on October 20, 1732, he wrote that they were “the most delightful Cares in the World.” The boy, whom he and Deborah nicknamed “Franky,” gave rise to a more ebullient version of Franklin than he had allowed the world to see. He also became more empathetic—it’s hard to imagine he would have written an essay like “On the Death of Infants,” which was inspired by the death of an acquaintance’s child, had he not been enraptured by his own son and fearful lest a similar fate should befall him.

By 1736, Franklin had entered the most fulfilling period of his life so far. His love for Franky had brought him closer to Deborah. Franklin had endured sadness—the death of his brother James, the man who had taught him printing and with whom he had only recently reconciled—and a serious health scare, his second serious attack of pleurisy. But he had survived, and at age 30 was, as his biographer J.A. Leo Lemay pointed out, better off financially and socially than any of his siblings “and almost all of Philadelphia’s artisans.” That fall, the Pennsylvania Assembly appointed him its clerk, which put him on the inside of the colony’s politics for the first time.

That September 29, a contingent of Indian chiefs representing the Six Nations was heading for Philadelphia to renegotiate a treaty when government officials halted them a few miles short of their destination and advised them to go no farther. The legislature’s minutes, delivered to Franklin for printing, spelled out the reason: Smallpox had broken out “in the heart or near the middle of the town.”

**********

Smallpox was the most feared “distemper” in Colonial America. No one yet understood that it spread when people inhaled an invisible virus. The disease was fatal in more than 30 percent of all cases and even more deadly to children. Survivors were often blind, physically or mentally disabled and horribly disfigured.

In 1730, Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette had reported extensively on an outbreak in Boston. But rather than focusing on the devastation caused by the disease, Franklin’s coverage dealt primarily with the success of smallpox inoculation.

The procedure was a precursor to modern-day vaccination. A doctor used a scalpel and a quill to take fluid from smallpox vesicles on the skin of a person in the throes of the disease. He deposited this material in a vial and brought it to the home of the person to be inoculated. There he made a shallow incision in the patient’s arm and deposited material from the vial. Usually, inoculated patients became slightly ill, broke out in a few, smallish pox, and recovered quickly, immune to the disease for the rest of their lives. Occasionally, however, they developed full-blown smallpox or other complications and died.

Franklin’s enthusiasm for smallpox inoculation dated to 1721, when he was a printer’s apprentice to James in Boston. An outbreak in the city that year led to the first widespread inoculation trial in Western medicine—and bitter controversy. Supporters claimed that inoculation was a blessing from God, opponents that it was a curse—reckless, impious and tantamount to attempted murder. Franklin had been obliged to help print attacks against it in his brother’s newspaper, but the procedure’s success won him over. In 1730, when Boston had another outbreak, he used his own newspaper to promote inoculation in Philadelphia because he suspected the disease would spread south.

The Gazette reported that of the “Several Hundreds” of people inoculated in the Boston area that year, “about four” had died. Even with those deaths—which doctors attributed to smallpox contracted before inoculation—the inoculation death rate was negligible compared with the fatality rate from naturally acquired smallpox. Two weeks after that report, the Gazette reprinted a detailed description of the procedure from the authoritative Chambers’s Cyclopaedia.

And when, in February 1731, Philadelphians began coming down with smallpox, Franklin’s backing became even more urgent. “The Practice of Inoculation for the Small-Pox, begins to grow among us,” he wrote the next month, adding that “the first Patient of Note,” a man named “J. Growdon, Esq,” had been inoculated without incident. He was reporting this, he said, “to show how groundless all those extravagant Reports are, that have been spread through the Province to the contrary.” In the next week’s Gazette he plugged inoculation again, excerpting a prominent English scientific journal. By the time the Philadelphia epidemic ended that July, 288 people were dead, but that total included only one of the approximately 50 people who had been inoculated.

Whether Franklin himself was inoculated or survived a case of naturally acquired smallpox at some point is unknown—there’s no evidence on record. But he emerged as one of the most outspoken inoculation advocates in the Colonies. When smallpox returned to Philadelphia in September 1736, he couldn’t resist lampooning the logic of the English minister Edmund Massey, who had famously declared inoculation the Devil’s work, citing Job 2:7: “So went Satan forth from the presence of the Lord and smote Job with sore boils from the sole of the foot unto his crown.” Near the front of the new Poor Richard’s Almanac, which he was preparing to print, Franklin countered:

God offer’d to the Jews salvation;

And ‘twas refus’d by half the nation:

Thus (tho ‘tis life’s great preservation),

Many oppose inoculation.

We’re told by one of the black robe,

The devil inoculated Job:

Suppose ‘tis true, what he does tell;

Pray, neighbours, did not Job do well?

Significantly, this verse was Franklin’s only comment on smallpox or inoculation through the first four months of the new outbreak. Not until December 30 did he break his silence, in a stunning 137-word note at the end of that week’s Gazette. “Understanding ’tis a current Report,” it began, “that my Son Francis, who died lately of the Small Pox, had it by Inoculation....”

Franky had died on November 21, a month after his 4th birthday, and his father sought to dispel the rumor that a smallpox inoculation was responsible. “Inasmuch as some People are...deter’d from having that Operation perform’d on their Children, I do hereby sincerely declare, that he was not inoculated, but receiv’d the Distemper in the common Way of Infection,” he wrote. He had “intended to have my Child inoculated, as soon as he should have recovered sufficient Strength from a Flux with which he had been long afflicted.”

Franklin would remember his son as “the DELIGHT of all that knew him.” (Tim O’Brien)

**********

Many years later, Franklin admitted in a letter to his sister Jane that Franky’s death devastated him. And we can imagine that for Deborah it was even worse. Perhaps out of compassion, few of Franklin’s contemporaries questioned his explanation for not inoculating Franky or asked why he had gone so quiet on the procedure in the months before his son died. Many biographers and historians have followed suit, accepting at face value that Franky was simply too sick for inoculation. Lemay, one of Franklin’s best biographers, is representative. He wrote that Franklin fully intended to inoculate the boy, but that Franky’s sickness dragged on and “smallpox took him before his recovery.” Indeed, Lemay went even further in providing cover for Franklin, describing Franky as a “sickly infant” and a “sickly child.” This, too, has become accepted wisdom. But Franklin himself hinted that something else delayed his action and perhaps cost Franky his life. Most likely, it was a disagreement with Deborah over inoculation.

The argument that Franky was sickly is based primarily on one fact: Nearly a year passed between his birth and his baptism. More substantive evidence suggests the delay was due to Franklin’s oft-expressed antipathy to organized religion. When Franky was finally baptized, his father just happened to be on an extended trip to New England. It appears that Deborah, tired of arguing with her husband over the need to baptize their son, had it done while he was out of town.

As to Franky’s general health, the best evidence is in Franklin’s 1733 piece in the Gazette celebrating a scolding wife. If Deborah was the model for this fictional wife, as she seems to have been, it’s worth noting the author’s rationale for preferring her type. Such women, he wrote, have “sound and healthy Constitutions, produce vigorous Offspring, are active in the Business of the Family, special good Housewives, and very Careful of their Husbands Interest.” It’s unlikely that he would have included “produce vigorous Offspring” if his son, then 9 months old, had been sickly.

So Franky probably wasn’t a particularly sickly child. But he might have had, as Franklin claimed, an unfortunately timed (and uncommonly drawn-out) case of dysentery throughout September, October and early November 1736. This was the “flux” that Franklin’s editor’s note referred to. Did it render the boy too sick to be inoculated?

From the outset, his father hinted otherwise. Franklin never said his son was sick, but that he “had not recovered sufficient Strength.” It’s possible that Franky had been ill, but was no longer showing symptoms of dysentery. This would mean that, contrary to what some biographers and historians have assumed, Franky’s inoculation was not out of the question. Franklin said as much many years later. Addressing Franky’s death in the Autobiography, he wrote: “I long regretted bitterly & still regret that I had not given it [smallpox] to him by Inoculation.” If he regretted not being able to give his son smallpox by inoculation, he would have said so. Clearly Franklin believed he had had a choice and had chosen wrong.

How did a man who understood better than most the relative safety and efficacy of inoculation choose wrong? Possibly he just lost his nerve. Other men had. In 1721 Cotton Mather—the man who had stumbled upon the idea of inoculation and then pushed it on the doctors of Boston, declaring it infallible—had stalled for two weeks before approving his teenage son’s inoculation, knowing all the while that Sammy Mather’s Harvard roommate was sick with smallpox.

It’s more likely, though, that Benjamin and Deborah disagreed over inoculation for their son. Franky was still Deborah’s only child (the Franklins’ daughter, Sarah, would not be born for seven more years) and the legitimizing force in her common-law marriage. Six years into that marriage, her husband was advancing so quickly in the world that she might have begun to worry he might one day outgrow his plain, poorly educated wife. If originally she had believed Franky would bring her closer to Benjamin, now she just hoped the boy would help her keep hold of him. By that logic, risking her son to inoculation was unacceptable.

That scenario—parents unable to agree on inoculation for their child—was precisely the one Ben Franklin fixed on two decades after his son’s death, when he wrote about impediments to the procedure’s public acceptance. If “one parent or near relation is against it,” he noted in 1759, “the other does not chuse to inoculate a child without free consent of all parties, lest in case of a disastrous event, perpetual blame should follow.” He raised that dilemma again in 1788. After expressing his regret over having failed to inoculate Franky, he added: “This I mention for the Sake of Parents, who omit that Operation on the Supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a Child died under it; my Example showing that the Regret may be the same either way, and that therefore the safer should be chosen.”

Franklin took the blame for not inoculating Franky, just as he took the blame for Deborah’s disastrous first marriage. But as in that earlier case, his public chivalry probably disguised his private beliefs. Whether he blamed Deborah, or blamed himself for listening to her, the hard feelings relating to the death of their beloved son—“the DELIGHT of all that knew him,” according to the epitaph on his gravestone—appear to have ravaged their relationship. What followed was nearly 40 years of what Franklin referred to as “perpetual blame.”

**********

It surfaced in various forms. A recurring theme was Benjamin’s belief that Deborah was irresponsible. In August 1737, less than a year after Franky’s death, he lashed out at her for mishandling a sale in their store. A customer had bought paper on credit, and Deborah had forgotten to note which paper he had bought. Theoretically, the customer could claim to have purchased a lesser grade and underpay what he owed. It was a small matter, but Benjamin was incensed. Deborah’s shocked indignation is apparent in the entry she subsequently made in the shop book, in the place where she should have entered the details about the paper stock. Paraphrasing her husband, she wrote: “A Quier of paper that my careless wife forgot to set down and now the careless thing don’t know the prices so I must trust you.”

Benjamin also conspicuously overlooked, or even denigrated, Deborah’s fitness as a mother. His 1742 ballad in praise of her, as Lemay points out, touched upon every aspect of her domestic skills except motherhood—even though she had mothered William Franklin since infancy and, shortly after Franky’s death, had taken in young James Franklin Jr., the son of Ben’s deceased brother. And when Franklin sailed for London in 1757 he made no secret of his ambivalence about leaving his 14-year-old daughter with Deborah. After insisting that he was leaving home “more cheerfully” for his confidence in Deborah’s ability to manage his affairs and Sarah’s education, he added: “And yet I cannot forbear once more recommending her to you with a Father’s tenderest Concern.”

Authors of a 1722 pamphlet on inoculation in Boston included a “reply to the Objections made against it” to counter the “Heats and Animosities” the procedure aroused. (Harvard College Library)

**********

At some point in the year after Franky died, Benjamin commissioned a portrait of the boy. Was it an attempt to lift Deborah out of debilitating grief? Given Franklin’s notorious frugality, the commission was an extraordinary indulgence—most tradesmen didn’t have portraits made of themselves, let alone their children. In a sense, though, this was Franklin’s portrait, too: With no likeness of Franky to work from, the artist had Benjamin sit for it.

The final product—which shows Franklin’s adult face atop a boy’s body—is disconcerting, but also moving. Deborah appears to have embraced it without qualm—and over time seems to have accepted it as a surrogate for her son. In 1758, near the start of Franklin’s first extended stay in London, she sent the portrait or a copy of it to him, perhaps hoping it would bind him to her in the same way she imagined its subject once had.

Returned to Philadelphia, the painting took on a nearly magical significance a decade later, when family members noticed an uncanny resemblance between Sarah Franklin’s 1-year-old son, Benjamin Franklin Bache, and the Franky of the portrait. In a June 1770 letter, an elated Deborah wrote to her husband that William Franklin believed Benny Bache “is like Frankey Folger. I thought so too.” “Everyone,” she wrote, “thinks as much as though it had been drawn for him.” For the better part of the next two years Deborah’s letters to Benjamin focused on the health, charm and virtues of the grandson who resembled her dead son. Either intentionally or accidentally, as a side effect of her stroke, she sometimes confused the two, referring to Franklin’s grandson as “your son” and “our child.”

Franklin’s initial reply, in June 1770, was detached, even dismissive: “I rejoice much in the Pleasure you appear to take in him. It must be of Use to your Health, the having such an Amusement.” At times he seemed impatient with Deborah: “I am glad your little Grandson recovered so soon of his Illness, as I see you are quite in Love with him, and your Happiness wrapt up in his; since your whole long Letter is made up of the History of his pretty Actions.” Did he resent the way she had anointed Benny the new Franky? Did he envy it?

Or did he fear that they would lose this new Franky, too? In May 1771, on a kinder note, he wrote: “I am much pleased with the little Histories you give me of your fine Boy....I hope he will be spared, and continue the same Pleasure and Comfort to you, and that I shall ere long partake with you in it.”

Over time, Benjamin, too, came to regard the grandson he had yet to lay eyes on as a kind of reincarnation of his dead son. In a January 1772 letter to his sister Jane, he shared the emotions the boy stirred in him—emotions he had hidden from his wife. “All, who have seen my Grandson, agree with you in their accounts of his being an uncommonly fine Boy,” he wrote, “which brings often afresh to my Mind the Idea of my son Franky, tho’ now dead 36 Years, whom I have seldom seen equal’d in every thing, and whom to this Day I cannot think of without a Sigh.”

Franklin finally left London for home three months after Deborah died. When he met his grandson he, too, became infatuated with the boy—so much so that he effectively claimed Benny for his own. In 1776 he insisted that the 7-year-old accompany him on his diplomatic mission to France. Franklin didn’t return Benny Bache to his parents for nine years.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Genealogy of Great Relatives

James Albert Meyler; Dad

James Joseph Meyler; Great grandfather

Albert Carlos Jones; Great grandfather

George Gephard; Great-great grandfather

Gus Grissom; 5th cousin 1x removed

Thomas Pynchon; 6th cousin

Norman Borlaug; Step 2nd cousin 2x removed/ 7th cousin

Harry S. Truman; 5th cousin 3x removed

LDS Prophet Joseph Smith: 5th cousin 3x removed

Robert Frost; 7th cousin 2x removed

John Wheeler; 7th cousin 2x removed

Edwin Hubble; 7th cousin 2x removed

Barack Obama; 8th cousin 1x removed

Sinclair Lewis; 8th cousin 1x removed

Ezra Pound; 8th cousin 1x removed

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow; 4th cousin 5x removed

Walt Whitman; 6th cousin 3x removed

John Bannister Goodenough; 9th cousin

Theodore Roosevelt; 4th cousin 6x removed

Franklin Pierce; 4th cousin 6x removed

Alexander Wheelock Thayer; 4th cousin 6x removed

Herman Melville; 5th cousin 5x removed

Ralph Waldo Emerson; 5th cousin 5x removed

Eleanor Roosevelt; 5th cousin 5x removed

Henry David Thoreau; 6th cousin 4x removed

Bertrand Russell; 7th cousin 3x removed

Jack London; 7th cousin 3x removed

Robert Millikan: 7th cousin 3x removed

James Joyce; 7th cousin 3x removed

Franklin Delano Roosevelt; 7th cousin 3x removed

Percival Lowell; 8th cousin 2x removed

James Thurber; 8th cousin 2x removed

Ernest Hemingway: 9th cousin 1x removed

John Steinbeck; 9th cousin 1x removed

Frances Arnold; 10th cousin

John Forbes Nash; 10th cousin

William Cowper; 4th cousin 7x removed

Johnny “Appleseed” Chapman; 4th cousin 7x removed

Sarah Bates Lawrence: 5th cousin 6x removed

Sophia Smith: 6th cousin 5x removed

Joseph Wharton; 6th cousin 5x removed

Abraham Lincoln; 6th cousin 5x removed

E.E. Cummings; 8th cousin 3x removed

Virginia Woolf; 8th cousin 3x removed

Thomas Alva Edison; 8th cousin 3x removed*

T.S. Eliot; 9th cousin 2x removed

Eleazar Wheelock (founder of Dartmouth); 2nd cousin 10x removed

John Harvard; 3rd cousin 9x removed

George Washington; 3rd cousin 9x removed

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (Mark Twain) 6th cousin 6x removed

Jane Austen; 6th cousin 6x removed

Emily Dickinson: 8th cousin 4x removed

Arthur Cayley: 8th cousin 4x removed

Winston Churchill; 9th cousin 3x removed

George H.W. Bush; 10th cousin 2x removed

Kip Thorne: 10th cousin 2x removed

Queen Elizabeth II; 11th cousin 1x removed

Oliver Cromwell; 1st cousin 12x removed

John Dryden (1631-1700); 2nd cousin 11x removed

Jonathan Swift (1667-1745); 3rd cousin 10x removed

Sir Isaac Newton; 4th cousin 9x removed

Rev. Jonathan Edwards; 6th cousin 7x removed

William Blake; 6th cousin 7x removed

Noah Webster: 7th cousin 6x removed

George W. Bush; 10th cousin 3x removed

John Keats; 10th cousin 3x removed

Roger Penrose; 11th cousin 2x removed

William Faulkner. 11th cousin 2x removed

King Henry VII; 13th great-grandfather

Anna Kendrick; 13th cousin

William Butler Yeats; 13th cousin

Mary Sidney Herbert; 3rd cousin 11x removed

Lord Byron; 8th cousin 6x removed

William Wordsworth; 9th cousin 5x removed

Charles Darwin; 10 cousin 4x removed

Sir Robert Robertson: 11th cousin 3x removed

Ernst Rutherford; 11th cousin 3x removed

Stephen Hawking: 12th cousin 2x removed

Prince William; 12th cousin 2x removed

Princess Diana Spencer; 13th cousin 1x removed

Martin Luther King, Jr.; 13th cousin 1x removed

King Henry VIII; 14th great grandfather

Mary Boleyn; 14th great grandmother

Mary Queen of Scots; 1st cousin 14x removed

Queen Catherine Howard; 1st cousin 14x removed

William Shakespeare; 1st cousin 14x removed

Sir Francis Drake: 2nd cousin 13x removed

John Milton; 5th cousin 10x removed

John Locke; 5th cousin 10x removed

Thomas Hobbes; 5th cousin 10x removed

Alexander Pope; 5th cousin 10x removed

King George II; 6th cousin 9x removed

John Witherspoon; 6th cousin 9x removed

Charles Dickens; 7th cousin 8x removed

Bishop George Berkeley; 7th cousin 8x removed

David Hume; 9th cousin 6x removed

Alexander Hamilton; 10th cousin 5x removed*

Percival Shelley; 10th cousin 5x removed

Rudyard Kipling; 11th cousin 4x removed

Henryk Ibsen; 12th cousin 3x removed

Samuel Beckett; 13th cousin 2x removed

Robert Louis Stevenson; 13th cousin 2x removed

Kate Middleton; 15th cousin

Queen Jane Seymour; 15th great aunt

Queen Anne Boleyn; 1st cousin 15x removed

King Richard III; 1st cousin 15x removed

Francis Bacon; 3rd cousin 13x removed

Jonathan Dickinson; 5th cousin 11x removed

Edward De Vere 17th Earl of Oxford; 6th cousin 10x removed

Johann Sebastian Bach; 6th cousin 10x removed

William Makepeace Thackeray; 8th cousin 8x removed

Charles Ives; 12th cousin 4x removed

Katherine Parr; 5th cousin 12x removed

Sir Walter Raleigh; 5th cousin 12x removed

Aaron Burr, Jr.; 10th cousin 7x removed

Carl Adolf Gjellerup; 11th cousin 6x removed

Margrave of Brandenburg; 8th cousin 10x removed

Sir Thomas More, Saint (1478-1535); 5th cousin 14x removed

John Donne; and wife Anne More: 8th cousins 11x removed (both)

John Michell; 12th cousin 6x removed

Geoffrey Chaucer; Father of Seventeenth great-uncle

Queen Catherine of Aragon; 8th cousin 15 times removed

Louis VIII France; 23rd great-grandfather

King Henry I Beauclerc England; 25th great grandfather

King Owain Gwynnedd ap Gruffyd, Wales; 25th great grandfather

Giraldus Cambrensis; 1st cousin 25 times removed

Yaroslav I “Wise”; 27th great grandfather

Rurik 1st Viking King of Russia; 31st great-grandfather

Old King Cole; 49th great-grandfather

Boadicea Queen of Britain; 49th great-grandmother

Cymbeline; 50th great-grandfather

Joseph of Arimathea; 51st great-grandfather

Marc Antony; 52nd great-grandfather

Tiberius Claudius Nero; 52nd great-grandfather

Jesus Christ; 2nd cousin 53x removed

Julius Caesar; 55th great-uncle

John Venn; Nephew of wife of 6th cousin 5x removed

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Mrs. Richard Bache (Sarah Franklin, 1743–1808) by John Hoppner, European Paintings

Medium: Oil on canvas

Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1901 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436686

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Summer During a Pandemic

May 1: I put all my things in my Lauren’s garage and move out of my San Francisco apartment to live in a cabin in Franklin, North Carolina. The flight is almost completely empty. May 8: I cut down a dead tree on the property and cut it into firewood. It is cool and foggy and my ears are ringing from the chainsaw buzz.

May 9: I climb up the side of a waterfall with my sister to see the brilliant green mountains from the top. I wave to some hikers below.

May 17: I drive down to Orlando to visit my mother and her two cats, Cupcake and Lollipop. It is very hot and very humid and I put on a bright orange Bahia band. May 19-21: I tune my mother’s upright piano. It ends up sounding better than it did, but still not great.

May 28: I have a virtual lesson with my guitar teacher and cry because of Francesco Milano’s beautiful renaissance music. I am off my meds and my teacher is shocked to see me cry.

June 7: We drive back to North Carolina to escape the Florida heat and humidity. We celebrate my mother’s birthday, even though she won’t turn 50 until September.

June 10: I see my brother and his wife and met their new husky, Ozzie. He likes to be scratched but also likes to bite.

June 15: I drive to Mount Pleasant, Michigan to visit my grandparents in their shoddy, rundown house. I sleep on a very uncomfortable cot in their bare, hot spare room.

June 16: I call my old lover and we talk on the phone for two hours and sixteen minutes. I am so nervous before the call that I can’t eat, and I burst into tears after we hang up because of how wonderfully the call goes.

June 17: I see my old friend, Mariah, and we walk around our hometown and get sunburnt. We stop in some woods and I have a thought that I could stay in these woods for days and no one would find me.

June 18: I drive to Holland, Michigan to visit my old choir teacher. We grill food and play music for each other and reminisce.

June 20: I drive to Chicago to visit my dad and two brothers. Their apartment is a mess.

June 24: I spend the afternoon teaching myself how to kick a field goal. It is much harder than it looks and I curse a lot, but some of them go through the uprights.

June 29: I ride my bike along a dirt trail that used to be train tracks. I can ride the trail all the way to Iowa if I want to. July 3: My dad and I drive to Cheboygan, Michigan to visit my other grandmother for the holiday weekend. She is preparing for knee surgery and I play guitar for her and her friends.

July 4: Dad and I ride around Mackinac Island on bikes and eat ice cream. We both get sunburnt. July 4: No fewer than six different places set off fireworks around the house. I keep turning my head to see them sparkle in the night sky like a kind of panorama.

July 4: I meet Wayne and Sherri and celebrate their 60th wedding anniversary with them. They give me advice on how to make a marriage last and in them, I see a life I hope I can live myself one day.

July 5: I visit my old lover and we hug awkwardly before we walk around her elementary school and some tennis courts into some woods. We both mention how easy it still is to talk to each other, but she cries for most of our time together.

July 5: We sit on a bench in the woods and I tell her I still love her and want to marry her, knowing that she would not say it back, and it is the greatest thing I’ve ever done. She doesn’t say it back and she cries even harder and I kiss her hand.

July 5: I walk her back to her house and give her two cheap, gold rings that used to be my great-grandmother’s. We hug and hold each other deeply this time and I kiss her forehead, not knowing if we’ll ever see each other again.

July 5: I drive away knowing that for the first time in my stupid life, I loved someone wholly and correctly and selflessly, without expecting a damn thing in return. I will always be proud of this, but it will make my heart hurt the rest of the summer.

July 10: I clean and restring my dad’s old 12-string guitar. I tune it down two whole steps lower than usual and it resonates louder than it ever has before.

July 13: I crack the glass face of my watch trying to change the battery. I’m so angry that I throw it across the room, shattering it further.

July 18: I record the guitar part for a song I’ve written called “Andromeda”. It is my favorite song of mine.

July 29: I have a virtual masterclass with Chinese guitarist, Meng Su. She is very kind and shows me ways to play smoothly while I’m wearing a Pearl Jam t-shirt.

August 1: Dad and I drive to my cousin Jack’s high school graduation party. I eat my weight in tacos and cookies.

August 1: We tour Aunt Paige and Uncle Jason’s house that they built and it is really beautiful. I think to myself that I’ll be extremely lucky to have a house of any capacity.

August 1: Grandma is recovering from knee surgery and is walking around with a cane. Aunt Peggy and her daughters, Katie and Sarah, are there, and we all play pool and I become closer with them than I ever have before.

August 10: There is a tornado and it knocks the power out for a few minutes. The tornado knocks over a tree into the apartment building next to ours.

August 11: I get my first tattoo of JS Bach’s handwriting of the phrase “Soli Deo Gloria”. I get the tattoo on my ribs and it hurts tremendously.

August 13: We celebrate my brother’s 24th birthday. We eat lots of sushi until we are stuffed.

August 18: We celebrate my 28th birthday. We eat Buffalo Wild Wings and Insomnia Cookies until I am sick.

August 20: I find a wounded bird lying in the sidewalk while I’m on a walk. I think his leg is broken, I pick him up and carry him back to the apartment.

August 20: I wrap him in a towel and put him in a box so he can rest. That night, I can barely sleep from worry.

August 21: The bird lives through the night and I take him to an animal clinic where the doctor says the injury is likely fatal, and if I’m comfortable, I can leave the bird there with them. I’m not comfortable, but I do anyway.

August 23: I find my grandfather’s straight razor from when he ran a barbershop. I try to sharpen it, but it doesn’t help much.

August 29: I visit my friend, Matt, from high school and we stay up until 5am playing cards with his brother, Paul, and his girlfriend, Gabi. He is so tired by the end of the night that he is falling asleep sitting up.

August 30: I go to visit my grandfather who is recovering from hip surgery. He moves very gingerly, which I’ve never seen from him before.

August 30: I take a walk around the house with Grandpa, which is the first time he’s been outside in a week. My grandma has to put his shoes on Grandpa and tie them for him, and I’ve never seen sacrificial love like that before.

August 31: I visit my friend, Sam, from college. We sneak into her family’s bowling alley and sit on the lanes together.

August 31: Sam and I eat Chinese food and watch TV together. We talk about so many things and the conversation never stalls.

August 31: I give Sam an awkward hug as I leave. I really want to kiss her, but I can’t tell if she wants to kiss me back, so I don’t.

September 1: The weather has cooled and I didn’t notice it had been dropping. It’s like the earth knows that summer has just ended. Every Friday this summer, I ate pizza and had a movie night and all summer, I took pictures of flowers and sunsets as though they were the first or last I had ever seen.

0 notes

Text

The Midheaven: How You Will Be Remembered

The Midheaven (MC) is commonly thought to describe one’s career path. Although this is a decent indicator of one’s overall path, it can be hard to relate to a specific career so early in one’s life. So, if you don’t relate to your Midheaven like, “Oh, you have a MC in Aries, so you’re probably going to be a police officer, solider, or athlete" then maybe try thinking of the Midheaven as how you will be remembered or what you are generally associated with. (Always trust your dominant sign to describe you the most- *a post similar to this coming soon) ✨No matter what career you decide, you will be remembered by your peers, co-workers, friends, and family by traits from the sign, aspects*, and planets* bestowed upon your 10th House.✨

♈ Aries MC: will be remembered for their courage, boldness, intimidating/unsettling nature, and/or originality. (ex. Stephen King, Meryl Streep, Kanye West, Joan of Arc, Bill Gates, Angelina Jolie, Madalyn Murry O'Hair, Pablo Picasso, Rachel Maddow, Will Smith, Franz Kafka, Tyra Banks, Aleister Crowley, Tina Fey, Francisco de Goya, Julia Roberts, Chris Farley, Joseph Goebbels, Marvin Gaye, Iggy Pop, Kate Moss, Alfred Hitchcock, George Wallace, Hank Williams, Ayn Rand, Rob Zombie, Alexandre Dumas, John Steinbeck, Anne Frank, Twiggy, Jack Black, William Blake, Celine Dion, Galileo Galilei, Al Gore, Emmylou Harris, Las Vegas-Nevada, Manhattan-New York)

♉ Taurus MC: will be remembered for their extravagant style or possessions, their values, and/or “diva” attitude. (ex. Henry VIII, Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe, Tina Turner, Pope Francis, Jackie Robinson, Selena Gomez, Drake, Donald Trump, Freddie Mercury, Agatha Christie, Muhammad Ali, Frida Kahlo, O. J. Simpson, Justin Timberlake, Marlene Dietrich, Malala Yousafzai, Christopher Columbus, Michael Bay, Luciano Pavarotti, Nicole Richie, Woody Allen, Marilyn Manson, Maya Angelou, Martin Scorsese, Bernie Madoff, Ringo, Josephine Baker, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Sarah Palin, Josh Groban, Chris Brown, Mary Kate & Ashley Olsen, Norway)

♊ Gemini MC: will be remembered for/through words (writing, phrase, acting, thoughts, speech), their cleverness, and/or mental/emotional detachment. (ex. Jean-Jaques Rousseau, Albert Camus, Madonna, J.R.R. Tolkein, Donna Summer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Chelsea Handler, Alex Trebek, Kurt Cobain, Julie Andrews, Oscar Wilde, Jay-Z, Richard Nixon, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Tom Hanks, Kris Jenner, Walt Disney, Miss Cleo, Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs, Hugh Hefner, Lizzie Borden, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Kathy Bates, Winston Churchill, Melissa Ethridge, Ernest Hemingway, Margaret Mitchell, Paul Simon, Greece, Tokyo-Japan)

♋ Cancer MC: will be remembered for their emotional impact, sensitivity, and/or parental care/control. (ex. Beyoncé, Matamha Gandhi, John F. Kennedy, Venus Williams, Britney Spears, Arthur Rimbaud, Elizabeth Warren, Denzel Washington, Jeffery Dahmer, Sun Yet-sen, Bob Hope, Stevie Wonder, Anderson Cooper, Cat Stevens, Anna Nicole Smith, Joe Jonas, Rock Hudson, Alice Cooper, Woodrow Wilson, Barbara Walters, T. S. Elliot, Coretta Scott King, Albert Schweitzer, Ted Cruz, Monica Lewinsky, H.P. Lovecraft, Anaïs Nin, Katie Couric, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Carole King, Neil Diamond, Harper Lee, Giacomo Puccini, Sidney Poitier, September 11 attacks, United Kingdom)

♌ Leo MC: will be remembered for their theatrics, arrogance/vanity, power, and/or regality. (ex. Grace Kelly, Prince, Isaac Newton, Adolf Hitler, Katy Perry, Charlie Chaplin, Aretha Franklin, Sigmund Freud, Jacqueline Onassis-Kennedy, Stanley Kubrick, Courtney Love, Mark Twain, Chaka Khan, Napoleon Bonaparte, Kathy Griffin, Jim Carrey, Alfred Nobel, Eric Clapton, Annie Oakley, Martha Stewart, Divine, Louis Pasteur, Robin Williams, Ludwig Van Beethoven, Chuck Berry, Vladimir Putin, Clint Eastwood, Missy Elliot, Frank Sinatra, Mel B, Edgar Allan Poe, Los Angeles-CA)

♍ Virgo MC: will be remembered for their scandals/controversy, never-ending toil, physicality/health and/or attention to detail. (ex. Hillary Clinton, Bruce Lee, Kim Kardashian, Ellen DeGeneres, Brad Pitt, Nelson Mandela, Bette Davis, Justin Bieber, Elvis Presley, Erykah Badu, Jimmy Page, Eartha Kitt, Leonardo de Vinci, Bob Marley, Joan Crawford, Margaret Thatcher, Eminem, Friedrich Nietzsche, David Lynch, Chaz Bono, Marlon Brando, Björk, Ozzy Osborne, Emily Brontë, Bernie Sanders, Georgia O'Keeffe, Diana Ross, Kahlil Gibran, Russia, United States)

♎ Libra MC: will be remembered for their inner/outer beauty, adaptability, and/or desire for or appearance of stability. (ex. Elton John, Jane Goodall, Malcolm X, Coco Channel, Kylie Jenner, Ronald Reagan, Princess Diana, Michelangelo, Oprah Winfrey, Bob Dylan, Winona Ryder, Jimi Hendrix, Mother Teresa, Elizabeth Taylor, Cristiano Ronaldo, Angela Merkel, Tom Brokaw, Alan Watts, Charles Darwin, Brigitte Bardot, Patti Smith, Chuck Norris, Linda Lovelace, Ray Charles, Lionel Messi, Eleanor Roosevelt, Lewis Carroll, Noam Chomsky, Lucille Ball, Venice-Italy)

♏ Scorpio MC: will be remembered for their physical attractiveness, taboo activities/topics, and/or natural talent. (ex. James Joyce, Billie Holiday, Taylor Swift, Barack Obama, Carrie Fisher, Jim Morrison, Selena, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Queen Elizabeth II, Ariana Grande, Marie Curie, Anthony Hopkins, René Descartes, Nina Simone, Willem Dafoe, Paul Newman, Mariska Hargitay, Thomas Jefferson, Ray Bradbury, Joseph Stalin, Larry King, Duke Ellington, Joan Jett, Buddy Holly, Megan Fox, Johnny Knoxville, Daniel Day-Lewis, Gwen Stefani, Francis Ford Coppola, Sophia Loren, Marcus Aurelius, China)

♐ Sagittarius MC: will be remembered for their joviality, reckless/wild free spirit, sense of humor, and/or philosophy/spirituality. (ex. Al Capone, Deepok Chopra, Shia LaBeouf, Audrey Hepburn, Harvey Milk, Johnny Cash, David Bowie, Bettie Page, Pablo Neruda, J. K. Rowling, Christina Aguilera, Michael Jackson, Henry David Thoreau, Adele, Janis Joplin, Maximilien Robespierre, Ellen Pompeo, Whitney Houston, Paul McCartney, Evel Knievel, Bruno Mars, Jimmy Fallon, Peggy Lipton, Karl Marx, George Takei, Ryan Gosling, Whoopi Goldberg, Vincent Price, Rio de Janeiro-Brazil)

♑ Capricorn MC: will be remembered for their accomplishments/legacy, conquering of odds, and/or persistence. (ex. Martin Luther King Jr., George Washington, Rihanna, Isadora Duncan, Benjamin Franklin, James Dean, Nikola Tesla, John D. Rockefeller, Serena Williams, Joan Baez, Snoop Dogg, Alexander the Great, Barbara Streisand, Ron Howard, Stevie Nicks, Bette Midler, Joan Rivers, Immanuel Kant, Queen Latifah, Johann Sebastian Bach, Walt Whitman, Che Guevara, Liza Minnelli, Amelia Earhart, Mariah Carey, John Lennon, George Lucas, Donatella Versace, Louis Armstrong, Pakistan)

♒ Aquarius MC: will be remembered for their rebellious nature, involvement in a social organization/group, and/or unpredictability. (ex. Miley Cyrus, Tim Burton, Voltaire, Mick Jagger, Carl Sagan, Rita Hayworth, Neil Armstrong, Amy Winehouse, Pamela Anderson, Carlos Santana, Edward Snowden, Leo Tolstoy, Mae West, Orson Welles, Charlie Sheen, Eva Peron, Miles Davis, Bruce Springsteen, Johann Kepler, Suddam Hussein, Ruby Rose, Gerard Way, Helen Mirren, Howard Stern, Arthur Conan Doyle, Mary Shelley, George R. R. Martin, Kristen Stewart, Jean Piaget, Ronda Rousey, Willow Smith, Florida, India)

♓ Pisces MC: will be remembered for their delusional optimism, supernatural success, and/or they are often idolized. (ex. Vincent Van Gogh, Albert Einstein, Irene Cara, Cher, Salvador Dalí, William Shakespeare, Edie Sedgwick, Fidel Castro, Lady Gaga, Dalai Lama XIV, Steven Spielberg, George Michael, Marie Antoinette, RuPaul, Judy Garland, Michael Phelps, Sally Ride, John Cena, William Faulkner, Victoria Beckham, Lee Harvey Oswald, Douglas Adams, Jean Renoir, Buzz Aldrin, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Farrah Fawcett, Osama bin Laden, Sam Cooke, Michael Jordan, Switzerland, North Korea)

#midheaven#astrology#birth chart#natal chart#celebrity#10th house#traits#mine#career#mc#aries midheaven#taurus midheaven#gemini midheaven#cancer midheaven#leo midheaven#virgo midheaven#libra midheaven#scorpio midheaven#sagittarius midheaven#capricorn midheaven#aquarius midheaven#pisces midheaven

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mrs. Richard Bache (Sarah Franklin, 1743–1808) by John Hoppner, European Paintings

Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1901 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY Medium: Oil on canvas

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436686

13 notes

·

View notes