#SanFranciscoChinatown

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Portsmouth Square 25 Years Later competition

November 28, 2022

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Dragon in Chinatown parade,” c. 1900. Photographer unknown (from an album compiled by Arthur O. Eppler in the collection of the Society of California Pioneers).

Dragon through the years: the strategic subtext for Chinese American parades

On a summer evening Chinatown, reporter Han Li for the World Journal newspaper captured mobilphone video of the parade of a dragon up Grant Avenue; he reported the August 2021 procession appropriately on Friday the 13th as an “exorcism event . . . eliminating the plague and blessing for health.”

Dragon exorcism down Grant Avenue, San Francisco, on August 13, 2021 (Photo by Han Li)

Li’s reportage represented merely the latest chapter in the hidden history of dragon parades through American streets and about Chinese America’s adaptation, improvisation, and survival in frequently hostile social environments.

The story of the dragon parade phenomenon is inseparable from the Lunar New Year or, in the more recent communist party-era parlance, spring festival. It represents the most important holiday for China and the overseas Chinese diaspora. Families instruct children that the approach and celebration of the holiday season calls for cleaning the house, paying off the debts, convening the family, visiting friends, and giving unmarried children money in red envelopes (紅包 pinyin: hóng bāo) or “lai see,” in Cantonese (利是, 利市 or 利事).

The Chinese pioneers of the mid-19th century imported this tradition, among others, to California and the rest of the US. In San Francisco, the Chinese New Year celebration dates back to February 21, 1851, and according to a San Francisco Chronicle article 120 years later, “shortly after the first Chinese immigrants landed on the Barbary Coast. The dragon first made its appearance on the City streets in 1860, during celebration of the Year of the Monkey, 4558.”

Along the way, the essentially private family event became public celebration. This article touches on how the Chinese community over time learned to turn the broader public’s interest, which can be traced to the mid-19th century, into a tool for civic engagement.

"Chinamen Celebrating Their New-Year's Day in San Francisco" (Harper's Weekly, March 25, 1871) from the collection of the California Historical Society. The accompanying article reads in part as follows: “Our illustrations on page 260 will give the reader a vivid idea of the way in which the Chinese keep their New-Year's Day in San Francisco. Their year commences on the 18th of February, but the festivities continue for several days, to the great annouyance [sic] of the poeple [sic], as the principal diversion is the constant explosion of fire-crackers and bombs. Some rather amusing as well as annoying incidents occurred during the festival, as shown by our artist in the street scene. One unhappy man, driven wild by the racket in front of his house, tries to drive off his annoyers by throwing water on the crowd; and some ardent specimens of Young America are engaged in a hand-to-hand tussle with young heathen Chinese, whose pigtails afford a point d'advantage of which the young rascals make full use.”

San Francisco’s best walking compendium on Chinese American life for all seasons, David Lei, will tell you that dragon dancing in America was, and is, political statement. He’s right.

Lei built his first float for the city’s Chinese New Year parade in 1969, and made went on to serve as the event’s Parade Director or executive team member from 1977 to 2007. He continues to act as the “Cultural Advisor” for the parade when he’s not speaking to speaking to institutions, including the Commonwealth Club, the California Historical Society, or the Asian Art Museum among others.

“There were grave concerns that the Chinese will be rounded up and put in camps,” Lei told NBC News back in 2018. Memories of the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WW II were fresh in the minds of Chinatown’s leaders. “By 1949, the Chinese were the enemies because China became Communist . . . [s]o this was their platform to do some good for the community. It was to survive in Chinatown. Tourism was a big thing, so this was a big tourism push.” Lei’s assertions about the modern parade are widely acknowledged and supported by the historical record.

Organized in 1953 by a handful of Chinatown's elite such as Henry Kwok Wong, a businessman and president of the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, the Lunar New Year parade represented more than an ethnic festival. The sponsors deliberately reminded participants of Chinese Americans’ loyalty to the United States, the community’s anti-communist sentiment, and their efforts to reach out to mainstream American society during the Korean War. Chinese American veterans of World War II and the Korean War marched at the front of the parade in validation of the community’s patriotism.

A cover from the Chinese New Year Festival program from 1954 (from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America)

In 1958, David’s father helped to organize the modern version of the Chinese New Year Parade with the sponsorship by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce.

“We generally agreed that the parade would be the commercial side of the festival. And the other side is more of the cultural side,” Wayne Hu, a former longtime parade organizer, also told NBC. Like his friend and contemporary Lei, Hu became a parade volunteer during his middle school years. His father, prominent real estate man Jackson Hu, had also served as a parade director.

The compartmentalization of the private from the public might appear at first glance as a singular masterstroke to elevate Chinatown’s visibility. However, but the Lunar New Year parade of 1953 represented less of an innovation and more of a re-tasking an old strategy in the continuum of community resilience and survival.

As Haiming Liu wrote in a 2008 book review of Making an American Festival: Chinese New Year in San Francisco's Chinatown, by Chou-ling Yeh (Berkeley: University of California Press), “[i]n the 1950s, many Chinese, especially those who lived outside of California and New York, avoided cultural ties with their home country and stopped celebrating Lunar New Year. They preferred to be seen and regarded as "genuine" Americans rather than as Chinese Americans. American-born Chinese spoke English only, failed to learn how to use chopsticks, and shied away from ancestor worship. In fact, many Chinese families left Chinatown. Thoroughly Americanized second- and third-generation Chinese Americans dispersed to other sections or suburbs of the city. . . The elites worked with city officials and members of the city's chamber of commerce to publicize the parade. In fact, city officials and businesses funded a publicity budget in the 1950s. Many newspapers sent journalists to report on the parade. The lion or dragon dances were often followed and surrounded by floats sponsored by the California state lottery, American airlines, or banks. As a result, the Chinese Lunar New Year parade became a staged performance for tourists, resembling the Rose Parade in the Los Angeles area.”

In Chinese America, the dragon – the running of which would constitute the parade’s grand finale for the next seven decades -- symbolized both Chinatown’s commercial exceptionalism and the deeper narrative of a people’s legitimation within the polity, particularly during a time of armed conflict between US troops and Chinese People’s Volunteers forces in Korea. By their own admission, Lunar New Year organizers designed the golden dragon festivities to (a) invite as many white and other non-Chinese Americans to enjoy the parade, and (b) relieve them of as many dollars for Chinatown businesses. Like the architecture of Chinatown’s oriental city theme park, the artifice of the dragon parade and its motives served as a template for other Chinese American communities

"By marching out there with dragons and lions and historic costumes, you're sharing your history, your heritage," Eugene Moy of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California told the LA-ist in 2019. "You weren't just a second-class citizen but rather an active and productive member of society." However, wasn’t talking about a New Year parade but about inserting a dragon into the parade for La Fiesta de Los Angeles of 1894. (See, https://laist.com/news/entertainment/los-angeles-chinatown-parade-history)

The long dragon stands at rest in the street for the La Fiesta de Los Angeles parade, 1901. (The California Historical Society and University of Southern California Digital Library)

A cursory view of the photography of the San Francisco Chinese community of the late 19th century shows how the modern parade-style and ubiquity of Chinese dragons in US popular culture represented both the culmination and re-purposing of an old playbook that was crafted to respond to the context of particular times.

Starting in the mid-19th century, Chinese merchants held family and clan banquets, decorated their stores, and organized lion dances during the Lunar New Year. Extending an invitation to non-Chinese guests to New Year and other celebrations represented the next logical step. By the 1880’s, the photographic record began to reflect the use of the dragon in various processions in the Chinatown area.

“The Dragon, Chinese Procession” circa 1880 (Photographer A.J. MacDonald). This enlarged detail of a stereograph looks north on Stockton near Sacramento Street. The First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church is seen on the left. The First Presbyterian Chinese Church can also been seen on in left in the distance at Stockton and Clay.

“A Street Scene In Chinatown” c. 1880. Stereograph by A J. McDonald (from the collection of the California State Library).

The above photo was taken on the eve of passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. By this time, Chinatown had become a safe haven and principal place of employment for thousands of Chinese (mostly men) who had been driven out of rural communities across California and other western states.

“Dragon Procession” c. 1882. Photographer probably by Isaiah West Taber (from a private collection). This photo of a dragon parade appears to have been shot as the procession moved south on Stockton Street.

“B 3649 Procession Wong Fong, Chinatown, S.F. Cal.” c. 1882. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber. This print for sale on an auction site appears to be the same image captured of a dragon parade south on Stockton Street.

A magazine illustration from 1895 based on at least the photo B 3649 of Isaiah West Taber and perhaps others.

“Chinese Parade with the Dragon” c. 1882 - 1892. Photographer unknown (from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection) This elevated view toward the north on Stockton Street shows a dragon-led parade moving south on Stockton. Men (for whom Victor Nee would describe almost a century later as the “bachelor society”) comprise most of the crowd at street level. Other onlookers appear from rooftops, windows and the store awning in the center of the photo. The porch with iron railing at far left is part of the First Presbyterian Chinese Church the located at 911 Stockton Street.

The above photo shows a Chinese parade as a dragon appears to pass in front of the First Presbyterian Chinese Church at 911 Stockton Street (seen at left) and turn the corner to continue east down Clay Street. This photo from the Bancroft Library lacks the identification of a print (c. 1892) signed by A.J. McDonald and held in the San Francisco Public Library’s collection.

“A Street Scene in Chinatown” circa 1892 (Photograph by A.J. McDonald from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection). The photo appears to have been taken a few minutes after the preceding photo. A Chinese parade with dragon can be seen over the heads of a diverse crowd watching the parade of a dragon. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church is seen on the left. The First Presbyterian Chinese Church appears on the left in the distance at Stockton and Clay. A cable car can be seen in the center background. The handwritten note on the photo states that the view looks north on Stockton Street from Sacramento Street.

Chinese parade with a dragon east down Washington Street and past pawnshops and the Grand Theatre in Chinatown, c. 1882. Photographer unknown. The dragon appears identical to the one shown in the preceding series of photos. However, unlike the apparent Clay Street route taken in the Stockton Street parade witnessed by I.W. Taber et al., this procession is moving east down Washington Street.

A Chinese dragon passes the attractions of Little Egypt and La Belle Fatima at the San Francisco Midwinter Fair of 1894. Photographer Unknown (Emiliano Echeverria/Randolph Brandt Collection)

The Midwinter International Exposition—also known as the Midwinter Fair—was held in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park from January 27 to July 4, 1894. Barbara Berglund's fine and concise essay about this “Orientalist Exposition” envisioned by San Francisco Chronicle publisher Michael H. de Young may be read here.

According to Berglund, “the positive associations that could be derived from the Chinese Building about the achievements of Chinese culture were tempered by negative associations with Chinatown. Since the Chinese Building contained a restaurant, tea house, joss house, theater, and bazaar it not only replicated many of the standard sites of Chinatown’s tourist terrain but also the racializing work done by them. The fair’s promotional literature even told visitors that all of the ‘attractive features’ of Chinatown could be seen at the exposition’s Chinese Village ‘under much pleasanter conditions’—thus playing on prevailing stereotypes of the neighborhood as filthy, malodorous, and teeming and conjuring up unfavorable images of Chinese immigrants willing to live in such an environment.’”

Of the Chinese community itself, Berglund recounts as follows: “On the day that the Chinese Building opened, a Chronicle report related, “The Chinese themselves took a huge interest in the exhibit and the place was thronged all day.” This account noted that the merchants and tourist entrepreneurs “in charge” were “mightily proud of their building.” They “conducted visitors to the joss house,” while in the “reception room” a “cultured Chinese . . . explained the hidden meaning of the wondrous works of art which adorned the walls.” These men aided and abetted the Midwinter Fair’s Orientalist fantasy by presenting an image of the Orient that, to non-Asian visitors, likely came across as reinforcing the difference, strangeness, and barbarism of people of Asian descent. However they also created a space that San Francisco’s Chinese could participate in and succeeded in representing Chinese culture in ways that this local community could respond to with enthusiasm and pride.”

This more subtle agenda, whether intentional or subconscious, can be seen in the some of the photographs of Chinese participants at the fair, particularly in the juxtaposition of the US flag with Chinese imagery as in this photo of a horse-drawn float with a dragon prow.

Golden Gate Park. China Day at the Midwinter Fair Jun 1894 A large dragon boat float in Chinese motif, flying American flags and pulled by horses. (Photographer unknown from the Wyland Stanley Collection)

“8484 Chinese Day at Midwinter Fair” June 1894. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection)

Children from San Francisco’s Chinese Public School form up in Golden Gate Park for China Day at the 1894 Midwinter Fair.

Like dragons, the use of Chinese children from Chinatown and other communities has continued in parades from the 19th to the 21st century parades. The students’ carrying the American flags adds poignancy to the image. By this time, the exclusion of Chinese from the US had been made permanent with the Geary Act of 1892, and the Chinese Six Companies-led boycott of the federal law’s residency certificate scheme had collapsed miserably in the preceding year with the US Supreme Court’s decision in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 US 698 (1893).

A Chinese dragon rests on sawhorses and stools on a cobblestone street somewhere in Chinatown, circa 1900. Photographer unknown (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection)

Having lost the struggle and legal challenge to the Exclusion Act, Chinese American communities entered the 20th century uncertain of a future of continued isolation and discrimination, unable to start families, and facing the prospect of dying out by legislative design. The first decade of the new century started badly for San Francisco’s Chinatown. The city had forced the quarantine of the neighborhood during a bubonic plague scare that persisted from 1900 to 1904, the devastating earthquake and fire of 1906 literally scoured Chinatown from the urbanscape, and it barely escaped obliteration by municipal efforts to relocate its people to Hunter’s Point. To avoid what would have been complete erasure, Chinese merchants seized upon their plan to rebuild and transform the neighborhood into the tourist-serving, oriental theme park that would serve as the dominant economic model for the next 115 years.

It was at precisely this time that an opportunity for salvation, at least from a public relations perspective, appeared in the form of the first Portola Festival and parade which occurred during October 19-23, 1909.

The Portola Festival official postcard showing its mascot, Queen Virgilia, and a Chinese dragon

San Francisco was looking for a way to celebrate the reconstruction of the city in the wake of the 1906 disaster. Civic boosters developed the idea of holding a festival to honor Don Gaspar de Portola Portola, the Spanish explorer and Military Governor of the Californias.

In the words of local historian, John T. Freeman, the festival became “the first major civic event enthusiastically supported by both the Chinese and Japanese communities. After years of vilifying Asians, the San Francisco press praised the Imperial navy and the beauty of the special cherry blossoms it had brought for the Japanese float. The Chinese community used the Portolá [Portola] Festival as a “coming out” after years of isolation. Chinatown had been rebuilt after the earthquake with tourism in mind. In the festival the Chinese introduced such spectacular floats, lion dancers and dragons . . .”

Portola Festival Parade. Photographer unknown, October 1909). This elevated view northeast across Market near 8th Street (at Marshall Square), shows a Chinese Dragon, crowds of people, campaign signs, the St. Boniface Church spire, and the Marshall Square Market can be seen in the background.

The first day of the festival featured “Portola” entering the Golden Gate and “landing” at Pier 2. A parade proceeded down Market Street from there featuring military members from several countries and equestrians dressed as Portola “dragoons.” While a precise date for the image above is unknown, it is likely from the Portola Festival’s military parade -- given the appearance in the foreground of men dressed like Portola’s dragoons on horses. They estimated crowd size was nearly a million people.

“Portola Parade [C-20]” October 1909 (photographer unknown from the Martin Behrman Negative Collection/Courtesy of the Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives)

The above photo shows a Chinese dragon in a Portola Festival parade from a view east on 15th Street toward Valencia. The Carmelita Apartments, built in 1907 at the northeast corner of Valencia and 15th, can be seen in background.

Portola Festival Parade, Oct 21, 1909. Photograph by Willard E. Worden (courtesy of a private collector)

The above photo shows the head of the Chinese contingent of the Portola Festival parade, looking east from the center of Market Street toward the intersection of Mason, Market, and Turk Streets. The Dean Building, Admission Day (Native Sons) Monument, Mechanics Savings Bank Building, Flood Building, and the Emporium can be seen in the background.

At the head of the Chinese contingent marching in the Portola Festival Parade, Oct 21, 1909. Photographer unknown.

A close-up of the female rider (dressed as the woman warrior Fa Mu Lan) heading the Chinese contingent in the Portola Festival parade of 1909. Photograph by Louis J. Stellman (from the collection of the California State Library). This photograph by Stellman also appears in Richard Dillon's 1976 book for the Book Club of California, Images of Chinatown - Louis J. Stellman's Chinatown Photographs. Dillon's caption provided few details about the photograph. His caption read as follows: "The strikingly serene beauty of many Chinese women was not lost on photographer Stellman. He was also much taken with their natural poise and dignity, as exemplified by this queenly rider in a Portola or Panama Pacific parade." According to historian Judy Young, the Chinese woman rider served as the parade marshal.

“Chinatown was invited to participate with its own section,” wrote the late historian Kevin Starr about its participation in the Portal Festival event. “San Francisco's Chinese community enthusiastically accepted this invitation and wasted neither time nor effort in preparing for the parade. And the community delivered; according to a 1909 article in the San Francisco Chronicle, ‘the Chinese more than sustained their reputation for superb pageants’ with colorful lanterns, loud gongs, and dragon dances.”

Portola Festival Parade – Oct. 21, 1909. Photographer unknown [Worden?] (from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America)

The above photo from the collection of CHSA shows the dragon carried by the heart of the Chinese contingent of marchers in the Portola Festival parade. Although CHSA lacks any information about the identity of the photographer for this image, the photo could have been taken by Willard Worden of the same event from a slightly different vantage point, i.e., bit farther up Market, but still looking east from the center of Market toward the Mason-Market-Turk intersection. One can see the Dean Building, Admission Day (Native Sons) Monument, the Mechanics Savings Bank Building, the Flood Building, and the Emporium in the background. The CHSA print shows the same spectators sitting on, and dangling legs over, the ledge of the Mechanics Bank building. The patch of shade cast by some large flag or banner from behind the photographer in the preceding image has been minimized in the photo of the dragon contingent.

The Chinese participation in the celebration reportedly won many awards, especially for a 375-foot long dragon that was animated by 200 men. “Given the decades of discrimination by San Francisco's White populations and Chinatown's deeply ingrained, sordid reputation as a ghetto filled with prostitution, gambling, and morally questionable bachelors,” Starr wrote, “the San Francisco Chinese community saw this parade as a singular chance to reshape its image among neighbors and mainstream American society. This festival represented the beginning of the Chinese community's movement to ‘clean up’ Chinatown. Community leaders believed that improving the image of Chinatown would improve the image of Chinese Americans, ameliorate long-standing discrimination and resentment against the Chinese American community, and allow better assimilation of Chinese people into mainstream American society. With the citywide changes after the 1906 earthquake, the Chinese American population began to assert not only its rightful belonging to the greater San Francisco and American communities, but also its own distinct identity, which was both Chinese and American.”

Given the apparent success of its appearance for the 1909 festival, a cursory examination of the photograph record shows that Chinatown leaders took advantage of advertising the community’s existence at civic events in the decades between the Portola Festival and the establishment in 1953 of the annual Chinese New Year’s Parade.

Shriner parade float at unknown location, depicting Chinese dragon and bridge on June 15, 1922. Photographer unknown (from a Burton Photo Album courtesy of a private collector)

“Chinese Dragon in Illuminated Parade Diamond Jubilee, September12, 1925. Photographer unknown (courtesy of a private collector).

In the 1930s, mainstream tourist agencies were still guiding tourists to see fake lepers and opium dens in Chinatown, continuing the “slumming” that had come into fashion in the late 19th century.

This photo was taken (circa 1935) at the intersection of Kearny and Post Streets, near the Shreve Building and Eastman Kodak offices at 216 Post Street. Photographer unknown (courtesy of a private collector).

Still from footage [soundtrack added] shot in 1940, by George Devlin (name on developed film) and acquired by Lost & Found Travel from an online estate sale. Although the photographic record from the years of the Second World War is scant, the dragon still appeared for Chinatown’s public celebration of the New Year. Mostly Chinese participated in the celebration, as this video of the 1940 parade down Grant Avenue shows: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pGpDEfZrqQA&ab_channel=Lost%26FoundTravel

The Second Sino-Japanese War had been raging in China since 1937, and China war relief through the national “Rice Bowl” fundraising campaign was featured prominently (at the 1:25 mark) in the parade. The dragon at the 3:00 mark of the video is seen making several turns in front of the old Shanghai Low restaurant.

After going dormant for 35 years, the Portola Festival made a comeback after a local civic club, the Golden Gate Aerie of Eagles, helped San Francisco revive the festival in 1948. According to local historian Arnold Woods, the City intended to stage a week-long Mardi Gras-like celebration from October 17 to 24, 1948. “The San Francisco Chronicle estimated that 750,000 people watched the parade, which it stated was the longest and most viewed parade in San Francisco history. Apparently the Chronicle either forgot about the viewing size and length of the 1909 Portola Festival parades or their 1909 estimates were overstated.”

The 1948 revival of the parade that started the 20th century appearances of Chinatown’s dragon in citywide celebrations provided the Chinatown community with another opportunity to remind others of its role in the life of the City.

Portola Festival parade with contingent of marchers with Chinese dragon. Morton-Waters Co. (SCRAP Negative Collection / Courtesy of SCRAP). Market near Stockton Oct 17, 1948.

The next three photos were all taken on Market Street near Sansome on Oct 23, 1948.

Men with Chinese dragon in Portola Festival parade. Market near Sansome Streets, Oct 23, 1948. Photographer Lumir Cerny, Morton-Waters Co. (SCRAP Negative Collection)

Grant Avenue and Sacramento Street, circa 1950 (Chronicle archives)

Before the turning point in 1953 (when the parade welcomed spectators from across the Bay Area), and as this photo attests, public celebration of the Chinese New Year with the dragon was largely confined to the Chinese community. (The chop suey signage for now century-old Far East Café can be seen in the upper right part of the photo.)

Grant Avenue 1953 (Chronicle archives).

In the “first year” that non-Chinese outsiders were invited to the New Year celebration, 140,000 spectators attended the parade. The Chinese Chamber of commerce became the sponsor of the parade and related activities. A decade later, the city’s Convention and Visitor's Bureau would co-sponsor the annual event.

Written on back: "Double Ten anniversary of Chinese Independence. Sunday parade and celebration. Albert Wong, a director of the Chinese Six companies, shows his little daughter, Charmaine, 4 1/2, that Chinatown's famed 250-foot long dragon is not such a terrible beast while Frank L. Nipp, president of Sue Hing Benevolent Association (one of 6 companies) entices dragon with a 'teaser' on long pole. This is promotion for Sunday's 'Chinese Independence Day' celebration and parade in Chinatown." October 8, 1954 from the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

The head for what is believed to be the dragon for the 1954 Chinese New Year Parade or the Double Ten parade of the same year. The head had been displayed previously in the main gallery of the Chinese Historical Society of America. (Photo by Doug Chan, March 23, 2022).

When this photo was taken on February 13, 1963, only one-fifth of the Chinese residents in San Francisco were estimated to actually live in Chinatown. The easing of racial discrimination in housing after the Second World War meant that deploying the dragon for Chinese New Year in the old neighborhood served to bind the citywide Chinese community, in public celebration of the season and ethnic identity, as much as attracting the tourists. As is evident from the photo, the annual event was out-growing the old parade route down Grant Avenue.

1965: Dragon battle at the San Francisco Chinese New Year celebration in Chinatown. (Photograph by Mike Alexander (San Francisco Chronicle)

San Francisco Chinatown’s innovative use of the parade and the ever-present dragon to elevate the neighborhood’s profile had expanded to other diaspora communities. For example, New York Chinatown’s community groups began organizing a public New Year’s celebration in the 1970’s, eventually attracting support from city government.

February 9, 1975: The air is thick with smoke from firecrackers at the San Francisco Chinese New Year Parade. Photograph by Barney Peterson (San Francisco Chronicle)

1983: From the back of the photo: Taking a break as the parade stops momentarily. The lead dragon carrier catches his breath on Stockton after running with the dragon for two blocks. Photograph by Steve Ringman (San Francisco Chronicle)

February 8, 1991: San Francisco Chinese New Year Parade Committee, from left to right, Gordon Chin, David Lei and Wayne Hu. (Not pictured from the Committee was Calvin Li. (The trio is posing with a lion's head.) Photograph by Michael Maloney (San Francisco Chronicle)

“The Chinese New Year Parade in San Francisco was made up. It's purely American like chop suey or the fortune cookie,” as David Lei asserted in an interview with Kye Masino (of founds.org) in 2019. While the 70-year institution of the parade may have served the interests of commerce and validation of Chinese Americans’ place in American society, the means by which the community asserted itself in the public sphere, i.e., the dragon, had been deployed early and often during the century that preceded the artifice of the parade.

2020 Year of the Rat Chinese New Year Parade, February 8, 2020. Photograph by Knight Lights Photography (courtesy of The Chinese Chamber of Commerce of San Francisco).

The genius-stroke was that a mid-20th century generation of Chinese civic leaders had reached into a turn-of-the-century bag of tools to re-deploy the iconic symbol of a resilient, patriotic, proud, and assertive American community – one that had survived and endured, ultimately to flourish, on this distant shore and in other neighborhoods across the North American continent.

Enter the dragon, indeed.

From the private collection of Wong Yuen-Ming

[updated: 2023-1-24]

#Chinatown dragon parades#Chinatown#chinesenewyearparade#SanFranciscoChinatown#PortolaFestival#MidwinterFair1894#David Lei#Chinese Chamber of Commerce#Lunar New Year#Isaiah West Taber#Stockton Street#Clay Street#Washington Street#Chinese New Year Parade 1953

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

. ◆40-50's San Francisco china town pin◆ (Sold out) . #vintage#SanFrancisco#chinatown#SanFranciscochinatown #snowplant #snow_plant #snow_plant_store #snowplantstore #snowplant #vintage #asakusa#vintageclothing #homegoods #vintageshop #vintagegoods #スノープラント#古着屋#浅草#ヴィンテージ#古着#雑貨#浅草古着屋#ヴィンテージ古着#ヴィンテージ雑貨#ホームグッズ#ヴィンテージショップ ... 【ご来店の際のお願い】 ⚫︎ご入店時は、マスク着用をお願い致します。 ⚫︎ご入店前のアルコール消毒にご協力をお願い致します。(入り口のアルコールをご利用ください。) ⚫︎混雑時、入店制限をさせていただく場合がございます。 ⚫︎マスク着用での対応とさせていただきます。共用部分のアルコール消毒・ドアを開けて換気をし営業致します。 . . 東京都台東区浅草5-50-6 1F 03-5849-4310 営業日 : 火・水・土・日 営業時間 : 13:00〜19:00 WEB SHOP : https://snowplant.buyshop.jp (SNOW PLANT) https://www.instagram.com/p/CKQb9oAjaL8/?igshid=1f5xer4ubkg0k

#vintage#sanfrancisco#chinatown#sanfranciscochinatown#snowplant#snow_plant#snow_plant_store#snowplantstore#asakusa#vintageclothing#homegoods#vintageshop#vintagegoods#スノープラント#古着屋#浅草#ヴィンテージ#古着#雑貨#浅草古着屋#ヴィンテージ古着#ヴィンテージ雑貨#ホームグッズ#ヴィンテージショップ

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The holiday weekend sale is LIVE and a great time to get some of those plush you wanted without the shipping! Free shipping (USA only) and free B-grade enamel pin with purchase now through Monday, Dec 2. Use code THANKYOU at check out. Link in bio. . . . . #kimchikawaii #chineseliondance #sanfranciscochinatown #sanfrancisco #blackfriday2019 #smallbusinesssaturday2019 #supportsmallbusinessowners #kawaiiartist #kawaiiplush #cuteart #cuteplush (at Davis, California) https://www.instagram.com/p/B5dn_AOF7ph/?igshid=gogchagblom7

#kimchikawaii#chineseliondance#sanfranciscochinatown#sanfrancisco#blackfriday2019#smallbusinesssaturday2019#supportsmallbusinessowners#kawaiiartist#kawaiiplush#cuteart#cuteplush

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Golden Gate Fortune Cookies #籤語餅 #goldengatefortunecookiefactory #fortunecookie #chinatown #sanfranciscochinatown #sanfrancisco #streetfood #dreamamerica #edreamamerica #dreamamericausa #california #roadtripcalifornia #roadtripamerica (at Golden Gate Fortune Cookies) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cl49AIsLZ6f/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#籤語餅#goldengatefortunecookiefactory#fortunecookie#chinatown#sanfranciscochinatown#sanfrancisco#streetfood#dreamamerica#edreamamerica#dreamamericausa#california#roadtripcalifornia#roadtripamerica

0 notes

Photo

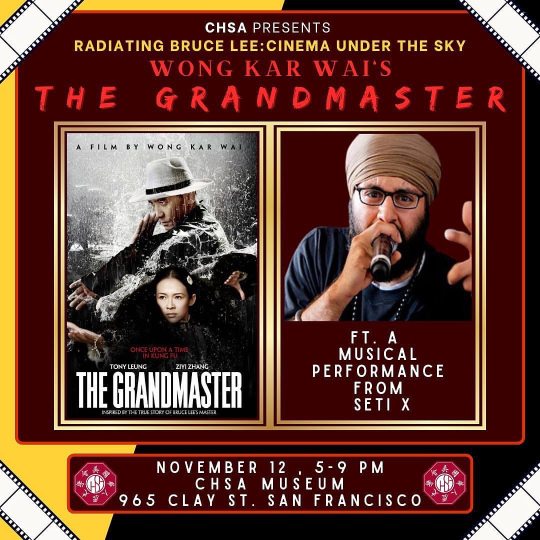

Hip Hop heads Bruce Lee fans don’t sleep on this! Posted @withrepost • @chsamuseum Our Radiating Bruce Lee: Cinema Under the Sky film series continues with a very special program spotlighting Bruce Lee's influence on modern hip hop music and culture as inspiration to artists of color. Complementing our screening of legendary Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar-wai's 2013 epic The Grandmaster will be a sunset hip hop performance by Sikh American emcee, musician and filmmaker SETI X. We will also show the short film documentary The Rhythm of the Dragon, produced by SETI X and DJ Gabriel Dela Cruz, which explores Bruce Lee's impact and relationship to the hip hop community, crossing races, genders, backgrounds, and generations. Join CHSA for an exclusive program that will feature a one-of-a-kind outdoor film experience along with a panel discussion about Bruce Lee's role in inspiring hip hop music and urban lifestyle cultures. This program is co-produced by Adisa Banjoko @bishopchronicles WHEN: Saturday, November 12, 5PM WHERE: CHSA Museum, 965 Clay Street, San Francisco Chinatown Tickets at CHSA.org or see link in bio. . . . . . #RadiatingBruceLee #CinemaUnderTheSky #BruceLee #WeAreBruceLee #ChinatownSF #SanFranciscoChinatown #TheGrandmaster #WongKarwai #TonyLeung #ZhangZiyi #HongKongCinema #ChineseAmericanHistory #MandeepSethi #SetiX #HipHopMusic #HipHopCulture #OutdoorCinema (at Chinese Historical Society of America) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ckl3vHeS1EP/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#radiatingbrucelee#cinemaunderthesky#brucelee#wearebrucelee#chinatownsf#sanfranciscochinatown#thegrandmaster#wongkarwai#tonyleung#zhangziyi#hongkongcinema#chineseamericanhistory#mandeepsethi#setix#hiphopmusic#hiphopculture#outdoorcinema

0 notes

Photo

🚶♂️ Pedestrians walk past the Ping Yuen #mural on #StocktonStreet in #SanFrancisco #Chinatown 👲🥡🥢🌁 #SanFranciscoChinatown @sfchinatown.today @onlyinsf 🌉 (at Chinatown) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cj-9mI0pzQS/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Day 4: Somewhere I’ve Been #sanfrancisco #chinatown #sfchinatown #sanfranciscochinatown #hopetogobacksoon #SeptemberPhotoChallenge #PhotoOfTheDay #photochallenge #SeptemberChallenge #Fall2022 #Fall #photoaday #photoadayseptember #September2022 #happylife #fmspad @fatmumslim (at Chinatown, San Francisco) https://www.instagram.com/p/CiFjCnDOjPm/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#sanfrancisco#chinatown#sfchinatown#sanfranciscochinatown#hopetogobacksoon#septemberphotochallenge#photooftheday#photochallenge#septemberchallenge#fall2022#fall#photoaday#photoadayseptember#september2022#happylife#fmspad

0 notes

Photo

🐲🥟 Visiting #ChinatownSanFrancisco again 🀄️ #SanFranciscoChinatown is the largest #Chinatown outside of Asia as well as the oldest Chinatown in North America. 🤩 #SanFrancisco 🇺🇸🐶🐾🇨🇦 #TravelDog #SanFranciscoDogs #SanFranciscoDog (at Chinatown, San Francisco) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cg7QQz7lilo/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#chinatownsanfrancisco#sanfranciscochinatown#chinatown#sanfrancisco#traveldog#sanfranciscodogs#sanfranciscodog

0 notes

Photo

San Francisco Chinatown #sanfrancisco #chinatown #chinatownsanfrancisco #sanfranciscochinatown #cityscape #cityculture https://www.instagram.com/elizabeththeiris/p/CZRF54NsFh6/?utm_medium=tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Photo

San Francisco MTA / MUNI 2015 New Flyer XT60 "Xcelsior" Electric Articulated Trolleybus 7251 on the 30. #SanFrancisco #California #cali #norcal #chinatown #chinatownsanfrancisco #sanfranciscochinatown #sfmta #muni #sfmuni #newflyer #newflyerindustries #xcelsior #bus #transit #transportation #ig_california #ig_cali #ig_sanfrancisco #sanfranciscobay #thebayarea #bayarea #californiaadventure #californialove #westcoast #Californiatrip #sanfranciscotrip #sanfranciscotravel #SanFranciscocity (at San Francisco, California) https://www.instagram.com/p/CFOv_IhnNdt/?igshid=ozo0tdhe1zw3

#sanfrancisco#california#cali#norcal#chinatown#chinatownsanfrancisco#sanfranciscochinatown#sfmta#muni#sfmuni#newflyer#newflyerindustries#xcelsior#bus#transit#transportation#ig_california#ig_cali#ig_sanfrancisco#sanfranciscobay#thebayarea#bayarea#californiaadventure#californialove#westcoast#californiatrip#sanfranciscotrip#sanfranciscotravel#sanfranciscocity

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brave New World: Aunt Wen Fan (nee Tsui) Chao and Uncle Jen-Da Chao

The six siblings, with the youngest and first aunts in the front row left side, accompanied by my cousin, extreme right. (Courtesy of Raymond Lee).

Among my earliest recollections are those of Aunt Wen Fan and Uncle Jen-Da, when I was 3-4 years old. They lived in Taipei near their parents, relatives and close acquaintances. As the oldest of four sisters, she was quick to express warmth, and placed the welfare of others before her own. Her husband was the eldest among four siblings, and shined as the trailblazer of the family. The couple appeared to be settled and content, with my aunt at home raising three children, and my uncle at Taiwan University embarking on a promising career as associate professor of accounting.

In 1977, the couple’s future transformed overnight after moving to the US for the sake of their children’s education and career futures. They were courageous to embark upon a fresh path in an unfamiliar landscape, while fiercely determined to make the journey successful. After settling in San Francisco, they operated a gift stop in Chinatown, in partnership with her youngest sister, Aunt Jane, and her husband, Uncle Joe, located across the street from my parents’ two gift stops. A year later, the Chao family sold the retail business interest and relocated to a township in New Jersey, around the same time my uncle’s siblings were also establishing residencies in nearby communities. The couple struggled to obtain suitable jobs with their limited English fluency and skill-sets. The travails of the Chao family are typical of the experiences among immigrants, but perhaps weighed more heavily in light of the creature comforts they gave up after leaving Taiwan. Over the years, my aunt and uncle faced many challenges beyond the financial, notably bridging the cultural and lifestyle differences between East and West, and ensuring that the next generation would become productive contributors in their adopted country.

Internment of the remains of my aunt and uncle. (Courtesy of Raymond Lee).

Their lives serve not only as testament to how a couple persevered during the best and worst of times, but reveal the depth of their sacrifices for their loved ones. Aunt Wen Fan and Uncle Jen-Da are nothing short of heroic role models for their descendants! Whenever I contemplate the trials and tribulations they endured in this Brave New World, the haunting, poignant passages in Emma Lazarus’ New Colossus (1883) hearken:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Written by CHSA community member, Raymond Lee. Lee was born, raised, and educated in San Francisco Chinatown. Raymond and his wife reside in Winnipeg, Canada. He is currently employed at the Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba.

#CHSA#chsamuseum#community#communityconnections#familystories#aunt#uncle#taipei#taiwan#sanfrancisco#sfchinatown#sanfranciscochinatown#chinatown#newjersey#bravenewworld#EmmaLazarus#NewColossus#chineseamerican#Chinese American

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Drummers Giants Fans #sfgiants #sanfrancisco #sanfranciscochinatown #drums #drummer #drummers #baterista #percussionista #batera #drumkit #moderndrummer #musica #music #talent #drumlife #rock #jazz #pop #country #vidademusico #drummerlife #drumming @cympad @tycoonpercussion @tycoonpercussionusa @rimriserusa @vicfirth @vicfirthlatinoamerica @vicfirth_italia @bigfatsnaredrum @kellyshuguy @beatobags @kickport @mightybright @aquarian_latinamerica @aquariandrumheads @aquarian.drumheads.br.oficial @baskey_music @earasersearplugs @earasers.hi.fi.earplugs @prenticepracticepads (at AT&T Park) https://www.instagram.com/p/BoJ2RtVgyiI/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1lkz6qwz3bgri

#sfgiants#sanfrancisco#sanfranciscochinatown#drums#drummer#drummers#baterista#percussionista#batera#drumkit#moderndrummer#musica#music#talent#drumlife#rock#jazz#pop#country#vidademusico#drummerlife#drumming

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#sanfrancisco #chinatownsanfrancisco #chinatown #sanfranciscochinatown #sanfrancisconights #sanfranciscostreets #streetsofsanfrancisco #sanfranciscolights #hellanice #sanfranciscolove #hellasanfrancisco #california #cali #californialove #californianights #caliliving #calilove #calinights https://www.instagram.com/p/CW55Y6zpEfk/?utm_medium=tumblr

#sanfrancisco#chinatownsanfrancisco#chinatown#sanfranciscochinatown#sanfrancisconights#sanfranciscostreets#streetsofsanfrancisco#sanfranciscolights#hellanice#sanfranciscolove#hellasanfrancisco#california#cali#californialove#californianights#caliliving#calilove#calinights

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Go ahead, light your candles, and burn your incense and ring your bells and call out to God, but watch out, because God will come and He will put you on His anvil and fire up His forge and beat you and beat you until He turns brass into pure gold.” 🕉 -SANT KESHAVADAS, taken from After the Ecstasy, the Laundry by @jack_kornfield . . . . . . . . . #chinatownsanfrancisco #chinatown #sanfrancisco #chinatownsf #california #bayarea #sfchinatown #chinatownchicago #chinatownnyc #sanfranciscochinatown #madeinchinatown #chinatownmarket #chinatownbandung #chinatownsg #chinatownsingapore #chinatownla #chinatownlondon #chinatowndc #chinatownyvr #chinatownbangkok #yelpsf #chinatowntoronto #chinatownsydney #x #savechinatown #chinatownvancouver #chinatownboston #goldengatebridge #chinatownsummernights https://www.instagram.com/p/CT0NRs2BQEB/?utm_medium=tumblr

#chinatownsanfrancisco#chinatown#sanfrancisco#chinatownsf#california#bayarea#sfchinatown#chinatownchicago#chinatownnyc#sanfranciscochinatown#madeinchinatown#chinatownmarket#chinatownbandung#chinatownsg#chinatownsingapore#chinatownla#chinatownlondon#chinatowndc#chinatownyvr#chinatownbangkok#yelpsf#chinatowntoronto#chinatownsydney#x#savechinatown#chinatownvancouver#chinatownboston#goldengatebridge#chinatownsummernights

0 notes

Photo

Lion got to check out the Chinatown Lunar New Year flower market today. It was lots of fun! . . . . #kimchikawaii #chineseliondance #liondance #sanfrancisco #sanfranciscochinatown #lunarnewyear #chinesenewyear2020 (at San Francisco Chinatown) https://www.instagram.com/p/B7ezwHLF4M9/?igshid=1uysk51enc02l

#kimchikawaii#chineseliondance#liondance#sanfrancisco#sanfranciscochinatown#lunarnewyear#chinesenewyear2020

0 notes