#chsamuseum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

👐🐝 Posted @withregram • @chsamuseum Join CHSA for a very special Black History Month celebration that expands on the @WeAreBruceLee theme of social unity and solidarity between Chinese and Black Americans. This presentation features 🎥 Film screening of The Black Kung Fu Experience [2012], a documentary about a group of African American pioneers who became respected masters in a subculture dominated by Chinese and white men. 👊🏾 In-person kung fu and martial arts demonstrations. 🗣️ Q&A with Sifu Donald Hamby and Sifu Troy Dunwood. These two remarkable athletes and coaches will speak about their success as internationally recognized martial arts masters, their Chinese Kung Fu teachers and what this practice means in relation to diversity, race and inclusion issues. Popup gift shop, beer, wine and other refreshments available. WHEN: Sunday, February 19, 2PM WHERE: Great Star Theater, 636 Jackson Street, San Francisco Chinatown Tickets now on sale; see link in bio. . . . . . #BlackKungFuExperience #BlackHistoryMonth2023 #BlackKungFu #KungFuDemonstration #WeAreBruceLee #ChinatownSanFrancisco #GreatStarTheaterSF #SFChinatown #ChinatownFilmScreening #ChinatownEvents https://www.instagram.com/p/CoWT_EhrEfU/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#blackkungfuexperience#blackhistorymonth2023#blackkungfu#kungfudemonstration#wearebrucelee#chinatownsanfrancisco#greatstartheatersf#sfchinatown#chinatownfilmscreening#chinatownevents

0 notes

Text

Bruce Lee: A Straight Blast From the Past that Packs a Punch

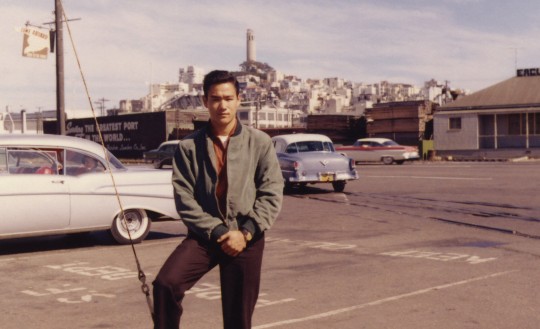

Bruce Lee posing with San Francisco’s Coit Tower in the background, circa 1959.

I recently visited the “We Are Bruce Lee: Under the Sky, One Family” exhibit at the museum and shadowed a high school tour. After being closed since the beginning of San Francisco’s COVID-19 shutdown, the museum reopened this spring with this new show. The exhibit is extraordinary! I was absolutely blown away - even for a high schooler like myself, who has never even seen a Bruce Lee movie. The exhibit is rich culturally and visually, and told an inspirational story of Bruce Lee as a martial arts maestro, an international pop culture superstar, and an individual who constantly broke barriers and inspired the world.

As I walked the exhibit and listened to the amazing docent at the museum, I learned of Lee’s fitness and nutrition routines and how he worked to build strength and innovate on his craft. He created a new form of martial arts called Jeet Kune Do which was based on Lee’s own philosophies and ideas about self-defense. I observed the archaic-looking fitness equipment and viewed clips from his film “Enter the Dragon” and was mesmerized by the question of how Lee was able to be so good and accomplish seemingly impossible feats. As I continued to journey through the exhibit, it became clear. He believed it could be done.

Because of Lee’s lofty aspirations, innovator’s mindset and tremendous work ethic to bring his dreams to life, Bruce Lee is relevant to even those who haven’t seen any of his films (Enter the Dragon, Game of Death, and Fists of Fury were some of his most famous films.). Lee was able to prove to the world that he could be an international star–even if he looked different from the “typical” action hero. He was loved by the world and transcended nationalities. To this day, my family in India watches Bruce Lee movies and I have an uncle there who proudly showed off to me the two-finger push-up he learned from Lee. Bruce Lee executed to perfection and the world noticed.

I personally found the experience to be very eye-opening in terms of learning about the challenges that Lee experienced at every turn. As I perused the wall of artwork from his TV shows and movies, and read about the racist portrayals of Lee, and other Asian people, in TV and movies at the time, I felt how difficult Lee’s journey was. He had to face harmful and hurtful stereotypes and overt racism. Lee encountered constant adversity, even as a TV star. For example, when he was in the show “Green Hornet,” he was paid significantly less money than the white protagonist, and he was given much less screen time and lines despite his many theatrical talents. I think that it is important for young people to learn about Lee because of how he persevered and fought against stereotypes and injustices.

The Green Hornet & Kato on TV Weekly from September 1966. (Courtesy of We Are Bruce Lee exhibit collector Jeff Chinn).

Also, the exhibit allows people to see the beautiful intersection of American and Chinese cultures in Lee’s identity, inspiring me, and giving me tremendous hope for the future. On a more personal level, Lee’s story specifically resonates with me because of my dual-identity as both an Indian and American. It is important to me that both facets of my identity can co-exist and I can grow as an individual by having this experience.

The exhibit connects to today’s world because of how it shows people a role model for discovering one’s identity in life and forging their own path. Lee married an American Caucasian woman, Linda Cadwell, which was considered scandalous at the time because interracial marriage was still illegal in several US states. For Bruce Lee, he blended his native Chinese culture with his newfound American identity to help craft something truly unique. Moreover - he showed that it can be done.

Overall, the Bruce Lee exhibit is a must-see—especially for my generation, because of how we can apply the lessons learned from Lee’s journey. In a complex world of misperceptions and barriers, the story of Bruce Lee is relevant today more than ever. Enter a true American hero.

Entrance to the Chinese Historical Society of America’s We Are Bruce Lee exhibit. (Courtesy of Nikhil Kothari).

Written by Nikhil Kothari. Kothari is a rising junior at Menlo School in the San Francisco Bay Area. This summer, he’s the Education and Community Engagement intern at the Chinese Historical Society of America (CHSA). He became interested in working with CHSA because of our wonderful museum exhibits and our efforts to raise awareness about the history of Asians in America and promote their legacy. Throughout this summer, he’ll be writing biweekly blog posts on a variety of topics associated with Chinese culture such as food, athletes, celebrities and docenting our Bruce Lee exhibit.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source: http://twitter.com/fluffysharp/status/964598330771759105

#LunarNewYear history: Against the backdrop of the Cold War, the Chinese New Year parade served as a public relations campaign for a community fearful of being put in internment camps as Japanese Americans had been. https://t.co/Qb1XM7XooP pic.twitter.com/9MSJ4LFSYN

— Melissa Hung (@fluffysharp)

February 16, 2018

Image: A cover of a Chinese New Year Festival program from 1954. CHSA Collection

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

instagram

Repost @channelcb “Towards Equality,” a new exhibit at @chsamuseum in San Francisco, highlights the accomplishments of California’s Chinese-American women in education, politics, finance, and business– as well as their pivotal role as matriarchs. – The exhibit recognizes the first American-born Chinese woman in San Francisco: Chew Fong Law, born in 1869. – It also recognizes Mary Tape, a Chinese immigrant who sued the San Francisco Board of Education in 1884 for refusing to enroll her daughter in school. The California Supreme Court ruled in Mary’s favor, stating that denying her daughter access would be unconstitutional. – Visit @chsamuseum or chsa.org for more information. – #channelcb #news #aapi #culture #asianamerican #usnews #新闻 #뉴스 #chineseamerican https://www.instagram.com/p/Br78Zy2hZsP/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=87cn3m0qftql

0 notes

Video

Thank you, Mark Niu and @chsamuseum #AviatrixFILM Interview for @cgtnamerica on #china24 #katherinepark - look for us at @museumofflight July 8th (at Chinese Historical Society of America)

0 notes

Text

Forbidden City, Chinatown

Dancer Jessie Tai Sing (of the Tai Sings) on a program cover (ca. 1942). (PC: Forbidden City, U.S.A.: Chinatown Nightclubs, 1936-1970 by Arthur Dong and Lorraine Dong).

While working as a Collections Intern for CHSA the summer of 2019, my main task was to digitize the VCR collection and create a Finding Aid for them. I watched a lot of film, ranging from minute-long news clips in which CHSA programs were mentioned to full-length documentaries such as Curtis Choy’s The Fall of I-Hotel (a true must-watch!). It may sound boring on the surface, but I truly enjoyed what I was doing. I was learning a lot about Chinese American history from diverse perspectives, and contributing to a cause I was passionate about, both as an East Asian Studies major and a Chinese American.

There was one documentary I watched that has stuck with me to this day: Forbidden City, U.S.A. At the time, like many people, I was only really familiar with the less “glamorous” sides of working in Chinatown, like working at laundries or in Chinese restaurants. What this unique film explored, however, was another side of Chinatown: its history as the center of San Francisco nightlife in the 1930s and 1940s.

One of the most popular clubs was Forbidden City, known for its premier all-Chinese cast. There were singers and dancers advertising themselves as “The Chinese Sinatra” and the “Chinese Sally Rand” who performed jazz songs and burlesque—a stark contrast to Chinese American stereotypes. Of course, part of the allure for the white audience was the fetishization of Asian women, but the performers themselves were very clear about the fact that there was no sexual exploitation against them. I was especially interested in the accounts of female performers like Noel Toy, who was famous for her bubble dance—particularly accounts of how they wrestled with conflicting cultural upbringings and racism to pursue their passion. I found it very inspiring how they held autonomy over their bodies and owned their sexuality in an industry notorious for taking advantage of vulnerable young women and also lacking Asian representation.

Noel Toy lifts bubbles and business for the Forbidden City, as in this article from Carnival Show magazine (March 1941) (PC: Forbidden City, U.S.A.: Chinatown Nightclubs, 1936-1970 by Arthur Dong and Lorraine Dong).

What drew me to the Forbidden City performers was just that—their bodily autonomy in a world that has denied it to them. For me, and I believe for many young Asian American women, it is difficult to be comfortable with your own body and sexuality without running up against rigid cultural standards about how women can comport themselves or against the response at the other end of the spectrum, the fetishization of Asian women in Western culture and the male gaze. As a young Asian woman, I have never felt totally confident looking at myself in a mirror or posting cute pictures on Instagram. “Guys only like you because you’re Asian,” my brain tells me, or “You’re not as skinny as the girls in K-dramas” or, to bring up the pervasiveness of the Model Minority myth, “Good Asian girls aren’t supposed to stand out.”

Mary “Butchie” Ong, Jessie Tai Sing, Kim Wong, and Helen Kim are featured in Beauty Parade magazine (November 1943). (PC: Forbidden City, U.S.A.: Chinatown Nightclubs, 1936-1970 by Arthur Dong and Lorraine Dong).

Beyond my own experience, the gross fetishization of Asian women has far more insidious consequences. There are so many published statistics from dating apps in which white males overwhelmingly answer that they “prefer Asian females” over all demographics (a sentence that grosses me out even as I type it). The fetishization of Asian American women is further normalized in film and television, where it often becomes the butt of jokes in everything from the 1987 film Full Metal Jacket's now notorious line from a Vietnamese prostitute, "me so horny, me love you long time,” to Kim Anami's 2021 “Kung Fu Vagina” music video, rife with cultural appropriation and stereotypical portrayals of Asian women as hyper-sexual “dragon ladies.” These stereotypes remain so pervasive that when I heard about the terrible hate crime against Asian women in Atlanta, I knew that the sense of sexual ownership white men so often claim over Asian women was the obvious motive.

As Asian American women, when one culture objectifies us and the other shames us, it is so difficult to love ourselves and take back the power over our bodies. We should be able to express and be ourselves fully no matter what the world tells us to be—just like the performers of Forbidden City.

Written by CHSA Development Intern Samantha Lam. Sam is a recent graduate from Oberlin College with a B.A. in East Asian Studies, with a focus in Korean Studies and a minor in Computer Science. As a daughter of two Chinese immigrants, Sam took an interest in U.S.-East Asian relations, and hopes to go to graduate school for Library and Information Science and help develop holistic and critical approaches to history education.

#chsamuseum#CHSA#chsacomcon#community connections#forbidden city club#forbidden city USA#asian america#chinese americans#chinese american women#body standards#bodily autonomy#body image#beauty standards

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hotpot Multiculturalism: A Vision of a Shared America

“America is a melting pot.” One of the most common cliches about our nation’s immigrant history and present diversity -- and perhaps one of the least accurate.

A romanticized depiction of the American “melting pot” for the 1908 play of the same name by Israel Zangwill. (PC: Wikimedia Commons).

As someone who immigrated from China to America when I was 11 years old, “America is a melting pot” was a saying I lived by every day. Integrating into elementary school was hard for an 11-year-old who didn’t speak the same language as everyone else. Going by my favored communication method from those early years in America, I’m surprised I never considered a career as a mime.

To make up for it, I tried falling back on a language I did know, performing my Mandarin for my band of wide-eyed classmates. Everyone seemed to enjoy my best attempts at translating their English names into Mandarin, but more often than not, I could only guess. I’ve always felt a sting of regret for mishearing ‘Robert’ as ‘rubber,’ then mistranslating ‘rubber’ as ‘eraser’ (橡皮 Xiàngpí) based on British English. The unlucky Robert then went around mispronouncing his mistranslated name as Cinnamon Bark (香皮 Xiānɡ Pí) for the entire school year.

As funny as these gimmicks were, each one of these cultural exchanges, each attempt to ‘please’ was part of an endless battle to belong. I knew there were unspoken lines, so I simply took cues from the people around me. When they laughed, it was a cue to laugh. When they looked flustered, it was a cue to appear concerned. I was a mirror, a reflection of my surroundings with little of my own to share. Everything I had learned from my upbringing in the People’s Republic of China, I packed up and dumped into the melting pot behind the mirror. Chinese proverbs and poems I had memorized, memories of home, proficiency in Mandarin, everything I didn’t use in my American school, dissolved in the melting pot like overcooked potatoes.

In recent years, the melting pot analogy has faced its fair share of criticisms for not embracing diversity. Its’ ‘healthier’ alternative, the salad analogy, appears more inclusive, but in fact supports the assumption that people of different cultural backgrounds coexist but share little in common, held together only by a salad dressing of shared ‘American’ values.

As a 1.5th generation Chinese American, I would prefer the hotpot way of bringing people together. Hotpot in Chinese culture is as much a social practice as it is a dish. It is rarely eaten alone. Especially on cold days, the hot steam from the pot provokes a sense of comfort and closeness among family and friends.

Hotpot starts with a pre-prepared soup base into which ingredients, including everything from meat, vegetables, and root vegetables to tofu, fish, and mushrooms of all different kinds, are added. Their variety also means balancing different cooking speeds and flavors. Some foods absorb more flavors, while others engage with the broth in creative ways.

A typical hotpot spread and broth, including different sliced meats, tofus, noodles, mushrooms, vegetables, and mixed sauces. (PC: the Woks of Life).

Take sponge tofu vs. sliced meats, for example. Sponge tofu maintains its shape and texture and soaks up the broth for a juicy bite. Sliced meats cook quickly, absorb tons of flavor, and leave a legacy of taste for the rest of the flavors to come. One way or another, the ingredients are all immersed in the hotpot together, changing themselves, changing each other, and the broth they leave behind.

Culture is dynamic and ever-changing. Unlike what happens in the melting pot, no one will melt away into nothingness. Unlike what happens in a salad bowl, we are all connected by more than a drizzling of vaguely defined shared values. The image of a cooking hotpot allows us to see our entanglement with one another in its totality, the connections between us that transcend time and space. Hotpot encourages us to see every ingredient as capable of change and capable of causing change. It values alternative embodied experiences of immigration that don’t strictly follow the worship of the American Dream. Some of us will assimilate and take up the broth’s accumulated flavor in all its glory. Others of us will hold onto our shape and texture in new environments. Regardless, all of us will leave our taste that will last long after we are gone.

Whether you identify as an immigrant or not, please look through your fondest memories and consider all the people with whom you have crossed paths. Consider how, whether the changes have been big or small, temporary or permanent, we have all changed one another.

If I could sit at a table with my 11-year-old self, I would encourage him to take his belongings out of the melting pot behind him to share a meal of hotpot with me.

Written by CHSA’s Spring 2021 We Are Bruce Lee Research Intern, Shou Zhang. Shou is a recent Master’s graduate from Wageningen University now residing in Little Tokyo’s heart in Los Angeles. Shou is working towards furthering his education to contribute to its body of knowledge and practice in museum/tourism spaces interested in heritage, memory, places, and critical theory.

#CHSA#chsamuseum#chsacomcon#community connections#multiculturalism#heritage#cultural exchange#diversity#melting pot#immigrant stories#chinese americans

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of A California Suffragette: Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee

Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee registers to vote in California. (PC: Wikimedia Commons).

Let’s begin with her hat: large, white, wide-rimmed, feather-bedecked. The sight of a Chinese woman walking into an American courthouse in 1911 wouldn’t have gone unnoticed. She knows it; that’s the reason she amplifies her presence by pulling on that hat. She wants to be seen.

On November 8, 1911, just a month after California women win suffrage, Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee enters a Bay Area courthouse and registers to vote, making her the first Asian woman in the country to do so. She was born into—and, in 1911, lives still—in a world that prefers her, and those of her "kind," to be, if not gone, then invisible.

This is not a new or subtle erasure. At that very moment, as she takes up a pen, there are signs everywhere in San Francisco and the greater Bay Area that read: No Chinese Wanted.

Thirty-six years earlier, in 1875, Chinese women were banned from immigrating to the U.S. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act had blocked all Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. Thirteen years after Lee casts her vote, the 1924 Immigration Act will pass, barring immigrants from all but the thinnest slivers of Northern Europe. Not until 1965 will America begin to see people like Lee as worthy of entry, much less the vote.

For Lee, this November day in 1911 is a beginning. She will become an organizer and activist. She will dedicate herself to helping other immigrants and Chinese Americans. She will live a long and memorable (if not always noted or remembered) life, dying in 1993 at the age of 107.

But let’s go back to that day, when she stands in that courthouse in her enormous feathered hat. You can see it, can’t you? The vision and determination that have brought her to this moment, that infuse her from the tips of her shoes up to the top of her hat, that guide her hand as she writes her name.

Written by Jasmin Darznik, a member of the CHSA community. Jasmin is a professor of literature and creative writing at the California College of the Arts. Her latest novel, The Bohemians, will be released on April 6.

#international womens day#women in history#clara elizabeth chan lee#chinese american women#chinese american#women's suffrage#chsa#chsacomcon#communityconnections#chsamuseum

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning Cantonese: A Family Adventure

“If flamingos turn pink when they eat so much shrimp, why don't cows turn green when they eat so much grass?”

As parents, we’ve encountered a lot of thought-provoking - and often fun - questions. Some have been easier to answer than others. Some are asked by our kids, others are ones we’ve asked ourselves.

One question I wrestled with was: “Should we try to teach our kids Cantonese - and if so, how?” Trying to decide whether to teach our kids Cantonese was not easy. I spent hours researching, often searching online late at night, thinking through each of our language decisions and options. Then, after finally deciding to teach our kids Cantonese, I spent hours figuring out how to actually do that.

Amazingly, today, our entire household speaks Cantonese! Along the way, we created bilingual Cantonese picture books to support our own learning, which grew into our own indie publisher Green Cows Books, named for the fun questions that emerge out of bilingual learning - and out of parenting in general. Most importantly, we continue to have fun. I'm sharing our story, with all my doubts and second-guessing, in case it helps another parent.

The Green Cows Books logo (Courtesy of Karen Yee).

How I got my entire family into speaking Cantonese

So...how did this turn into a family adventure? How did we go from one native (but limited) Cantonese speaker to the entire household speaking Cantonese? Why do I spend so much time making Cantonese-English picture books?

First, before my son was born, I made the reluctant - but relatively quick - decision that we were NOT going to teach him Cantonese. I was the only Cantonese speaker in our house, and even then, I had grown up in California and mainly learned "around the house" language. While I had attended weekend Chinese school, my reading and writing were limited. Simply put, I was intimidated. Other voices seemed to validate my fears: Parenting forums debated the wisdom of trying to teach kids multiple languages. Well-meaning relatives suggested Cantonese was a “dying language” and Mandarin might be more useful. And of course, there just weren't Cantonese resources available. So we decided to focus our efforts on Mandarin, a language neither I nor my husband speak.

Then my son was born, and things changed. While my Cantonese was limited, speaking English to my own kid just didn’t feel like “home.” I decided that however basic my Cantonese was, I would try to pass it on. If I failed, nothing changed. But, if I succeeded, then my son would speak a "dying language” spoken by 74 million other people around the world.

So I began speaking Cantonese to our son - and this is where everything jumbles together time-wise. It was difficult at first - I felt awkward, and there were words I didn’t know (I had to learn them first!). We introduced Cantonese and Mandarin songs early on, but waited until our son turned 2.5 before introducing Cantonese cartoons (all on YouTube!). It was also tough for my husband for a while - once our son started speaking Cantonese, my husband could not understand what we were saying. But with a little one, we said the same phrases many times a day - "let's go!", "time to eat,” "drink your milk!", etc. Somewhere along the way, my husband learned basic Cantonese.

Meanwhile, I searched non-stop for Cantonese books. I found a lot of books in Chinese and English; some books with Mandarin pinyin or zhuyin; and some books with Cantonese romanization. But I found nothing focused on spoken Cantonese.

So I began making my own Cantonese learning materials. I’d noticed that our board books had images of apples, ice cream and grapes - but nothing with Chinese food. So I printed out pictures of egg tarts, sesame balls, shrimp dumplings, almond tofu and tong yuen to learn alongside words like "apple" and "banana". No disadvantage at the dim sum table for our son! I also included materials to support my husband - primarily key phrases such as “What do you want to eat?” and “I want to eat...” We’d quickly realized that just a few basic phrases go a long way towards communicating with toddlers!

A portrait of Karen Yee, founder of Green Cows Books (Courtesy of Karen Yee).

Our materials worked amazingly well. When we finally took our 2-year-old to dim sum, he recognized a lot of the items. He even tried to order for himself: “daan taat!” (egg custard tart). (Though the waitresses paid very little attention to our toddler.) Eventually, I turned these materials into our first book, “My First Everyday Words in Cantonese & English.”

Today, our older one is trilingual. He learned Mandarin at daycare, Cantonese at home, and English. He was talking nonstop by 18 months. Our relatives generally also agree he has a better Cantonese accent than I do, even though he learned his Cantonese from me. I think he must have applied his Mandarin to Cantonese! His Mandarin is apparently excellent, and he was even chosen to represent his school at a reading contest.

Our 2-year-old is fluent for his age - he and his older brother speak Cantonese, but sometimes switch to Mandarin. While I’ve heard that learning multiple languages simultaneously can cause speech delays, neither of my kids experienced this. I think this might just be personality-driven! My husband now speaks Cantonese. And my mother-in-law also has picked up Cantonese. Being able to speak Cantonese (or even just understand the basics) has made for easier conversations with extended family.

A portrait of Yee’s family, all of whom contribute to Green Cows Books’ language offerings as writers and translators (Courtesy of Karen Yee).

So, where are we now in this learning adventure?

Our books are family activities. Topics are chosen by our kids, and each book is fully kid-approved. For example, every find-and-point-item - such as in Goh Goh and Dai Dai's Big Day with Elephant - is thoroughly tested.

Our Mandarin translations are actually done by our older son. He's been (informally) translating for us since he was able to talk, and translating books pushes him to stretch his Mandarin. He gets to choose kid-appropriate language - and his own pen name - to appear in the books. He’s also now started school - they teach English through what they call “Reader’s Workshop” and “Writer’s Workshop.” We now sometimes write together!

Honestly, I don't have much of a roadmap. Some days, I can't even think ahead to dinner and what we're going to eat. I want us to continue creating books that are useful for parents and for kids, for everyday communication - but even if they're meant to be educational, I want them to be fun and easy to read. As our kids have gotten older, we’ve also moved towards slightly more advanced story books. We're also experimenting all the time. For example, we introduced a few other languages, including in Korean and German (our friends wanted to do their own translations!).

I hope that you will join us on our adventure!

I would love to hear from other parents who care about bilingual education. As a mom, I’d love to learn about what’s worked for you, and how you support your kids with their language learning. For those who are focused on Cantonese (or Mandarin), I'd love suggestions and feedback on future books. Please get in touch!

Written by Karen Yee, a member of the CHSA community. A Cantonese-American mother of two, Karen’s efforts to teach her sons Cantonese inspired her to found Green Cows Books, an independent publisher of bilingual children’s books in seven languages (and counting!). She lives with her family in San Francisco.

#chsamuseum#community connections#chsacomcon#chsa#bilingual education#cantonese#language learning#language#second language#family#family language learning#heritage#children's language learning#chsa community

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homecoming: A Meditation on Place and Belonging Across Countries

An aerial view of Qingdao. (PC: Business Traveler USA).

Qingdao is a temperate seaside city, dipped in red, green, and blue pigments. Stuck onto the Shandong Peninsula's belly, it's a port city with a colonial history dating from 1897 to 1945. After it was liberated in the aftermath of the second Sino-Japanese War, Qingdao emerged from the smoke a landscape of Bavarian-style infrastructure, from its mansions, train station, and gothic church, to its signal towers and sewage system. In the north, a rock formation in the shape of an elderly man (石老人) sat in the cold water, waiting for his daughter to be returned from the Dragon King. From this post-war landscape, Qingdao grew into a city that 8.29 million people now call home.

It is against this backdrop that my parents were born, went to school, met, and married. It is the same city in which I was born in 1994 and raised by my grandparents. The same scenery I saw through the airplane window when I left for America. The place from which the stone man bid me farewell as I flew overhead.

If I could eye-beam my memories of my first 12 years in Qingdao onto a projector screen, I could only offer a few hours of screen time. Among that small pile of memories, a steep street between my house and the local grocery store stands out most. It was dusty and occasionally smelled, but because I was always careful not to slip while running down the pavement, I remember it best. It would be the first street I would see leaving home and the last street I'd see when returning.

I was naïve to think that when I returned from America, everything would be the same.

石老人 (the stone old man) viewed from a distance. (PC: Wikimedia Commons).

My early days in America were spent in Norfolk, Virginia, where I was blessed with curious and kind-hearted Virginians who were patient with my level of English. I was the only Asian student in the school. Despite my schoolmates’ best intentions, the special attention I was given for having lived in the People’s Republic of China made me feel distinguishably Chinese in America. Still, I did not miss home. I just wanted to be treated like everyone else.

In 6th grade, my family moved to Los Angeles and I was no longer the only Asian student. But caught up in other Asian Americans’ own crises of identity, I was rejected for reminding other Asian Americans of their origins. I felt distinguishably Chinese in Asian America and found companionship with other F.O.Bs (Fresh Off the Boat, a hurtful derogatory term) who felt like me. I missed Qingdao. Once again, I longed for a sense of belonging.

My father started off in America with close to nothing, so money was always tight. When my family’s finances started to look up in my high school years, we finally had enough for me to visit Qingdao again. In my eyes, it was a long-overdue homecoming. Hundreds of lovely scenarios rushed through my head: reuniting with my family, food, and at last, being able to do things with my former classmates that we couldn't do as children. For some reason, going to KFC together was particularly important.

I arrived home during a rainstorm, the city looking far more monotone than the one I remembered. Heavy rain was something I had grown unfamiliar with from years of living in the sunshine of California. The view from the window on the road to my grandparents’ house felt so alien, I felt more like I was on vacation in someone else’s city than returning to my own.

Distracted by these thoughts, the weight of the word 'home' didn't hit me until I opened the four suitcases of gifts my mom had imparted to me to give to the family. My uncle's index finger led my eyes to the two silhouettes by the staircase—my grandparents. Their souls radiated a familiar warmth, but it seemed like five years apart had weathered their appearances. A few more ridges and blemishes had appeared under their eyes, and a villainous shroud of white now colored their hair, robbing me of my youthful ignorance of aging and dying.

Qingdao from a front-facing angle, with a traditional temple in the background. (PC: User RWilliam on DeviantArt).

Being back was good; I was finally able to chow down on my favorite dishes in the Lu culinary style, one of the eight culinary traditions of China less well-represented in the American Chinese restaurant scene. It was sad to hear that the breakfast stalls from my childhood were all replaced by new ones, but they were still delicious. A week went by like a flash. Visits paid by family friends and neighbors became like a metronome, beating to the most extraordinary, mundane fact that I had lived in America. The barrage of questions and praises reminded me of feeling Chinese in America, just reversed: In those moments, I felt distinctly American in China.

In that week, I also learned that our old neighborhood, along with the dusty road, had been demolished, new modern middle-class apartments now standing in its place. Thankfully, the road is still steep, waiting to ambush the next careless child.

In the weeks that followed, I met with my childhood classmates and found out that the years apart had made us strangers. If not for our history of a shared classroom, we might not have given each other a second glance. We never went to KFC.

Two months of confrontation with the truth of change tired me, and I looked forward to going back to Los Angeles. Endings are always harder than new beginnings, but just as the inevitability of life is to change, I said goodbye once again to my hometown. Flying to America once again, I cried at the realization that for me, Qingdao had long since ceased to be home.

An aerial view of a guesthouse in Qingdao. (PC: User unijgi on DeviantArt).

Since that first return to Qingdao, I have returned a few more times. Each visit seems to be increasingly melancholy, burdened with paying respect at someone’s funeral. Over time, I have come to terms with the truth that places change whether we are in the scene or not with little regard for our love for old roads. And as I look into the shiny glass panels that line the city reborn, I see that I’ve grown taller.

In this increasingly interconnected world, this feeling of mobility and change is probably relevant to many of us. Some of us leave home to pursue education, work, relationships, opportunities, or even glory. 'Going home' afterwards can be loaded with feelings as layered as an onion. It’s an onion that many of us might have cut into, one whose sting lingers even now. Think for a moment—if we toss away the boundaries mandated on maps, aren't we all migrants in this world of uncertainty and change?

Written by CHSA’s Spring 2021 We Are Bruce Lee Research Intern, Shou Zhang. Shou is a recent Master’s graduate from Wageningen University now residing in Little Tokyo’s heart in Los Angeles. Shou is working towards furthering his education to contribute to its body of knowledge and practice in museum/tourism spaces interested in heritage, memory, places, and critical theory.

#qingdao#chsacomcon#communityconnections#chsamuseum#homecoming#china#america#chinese in america#reflection

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHSA Interns Respond: What does AAPI Heritage mean to us?

This month, we asked our interns to share their reflections on AAPI Heritage, answering the question, “What does AAPI Heritage mean to you?” Here’s what they wrote:

AAPI Heritage Is…

...a living history

Shou Zhang, Research Intern (We Are Bruce Lee)

I am a 1.5 generation Han Chinese American.

I believe our communities' diverse and beautiful history lives through us like water flowing from the past into the present and onwards to the future. Our very existence in this country is a testament to the resilience of those who came before us. When I can go to a Chinese grocery store and buy goods that satisfy my taste for the Chinese Lu culinary cooking style, that experience is the legacy of our lived history. When I cook the dishes that my family taught me, the very act of it is a celebration of my Han Chinese culture.

Examples of China’s Lu cuisine, originating in Shandong. (PC: China & Asia Cultural Travel).

To me, the AAPI history of my community is a lived experience. I recognize that the Han Chinese and Han Chinese American community in America are members of a wider community whose struggles and experiences intersect with our own. So for me, AAPI History Month means going beyond protecting, sustaining, and sharing the history of the culture of my community – it means finding the emotional space to listen to the stories of other AAPI communities.

In my journey as someone who grew up and emigrated from the People's Republic of China, I have been particularly invested this month in learning more about the lived experiences of other ethnic and indigenous communities who emigrated from mainland China, who have had a drastically different experience than my own.

...a way to understand my identity

Samantha Vasquez, Research Intern (Chinese in the Richmond)

Being Asian American is integral to my identity, as I have spent almost twenty-one years attempting to understand what it meant to be Asian and American. I am a Chinese adoptee with a third-generation Chinese American mom and a first-generation Mexican American dad. I learned about the term "third-culture kid" in a Multiracial Americans course in college, and I found it to describe my experiences almost perfectly. This experience is defined as the phenomenon in which a child grows up with their parents' culture and the culture of the place they grew up. Both of my parents grew up in the U.S. and have navigated what it means to be American. For me, I have my Chinese heritage, through which I participate in traditions and cuisine, and I also have my Mexican culture, through which I understand Spanish phrases and attend religious ceremonies.

There are so many nuances with my identity that I had trouble understanding when I was younger, but I embrace being Asian American because it can encompass these nuances. I want to give my children the tools to begin to understand their identities, no matter what their culture is. I want them to know my parents and their cultures' influence on my upbringing. I want them to embrace all cultures and realize how interconnected we all are.

...a source of political strength

Katherine Xiong, Community Programs Intern

I have to admit that I struggle a lot with the term “AAPI.” Doubtless, the lived experience of individuals grouped together under the AAPI umbrella are extremely disparate -- even within ethnicities, there’s so much diversity that it’s hard to say that people belong ‘together.’ Take the term “Chinese” for example: It’s fuzzily defined. It can (or can not) include diaspora from the mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, etc., many of whom chafe under the label “Chinese American” because of political connotations in their countries of origin. It can include descendants of the first railroad workers, migrant workers, and communities facing gentrification, but can also include some of the richest people in America, many of whom have become the gentrifiers. We don’t all have the same history, or the same political issues, either. Questions of affirmative action that my conservative parents are thinking about and questions of media representation my friends are thinking about are not the same problems that massage workers or Chinese American elders in large cities are facing. Zoom out to all of the ‘AAPI’ umbrella, and the differences grow still vaster. Yet outsiders often read us as “all the same.”

A protestor displays her support for solidarity between the Black and AAPI communities. (PC: NBC News).

As I interpret it, the power of the term “AAPI” has less to do with identity and more to do with politics. And it’s not about having the same political ‘issues’ or racial/ethnic stereotypes. It’s about coalition-building and solidarity in spite of difference -- building from communities up, across ethnic and class lines. It’s about recognizing the ways in which we all get ‘read’ as one people from the outside and leveraging those misconceptions to say, ‘If you treat us all as one people, fine. Then we’ll face our problems together, and support each other in each other’s problems, no matter how different we are. We are not the same, but our communities do not have to form around divisions and differences. We can borrow each other’s strength. We can -- and will -- make change.”

...the past (and the people) who shaped our present

Samantha Lam, Development Intern

As Asian Americans, we have been taught to believe that we are the model minority, and thus a greater ‘proximity to whiteness.’ AAPI history tells us the exact opposite. For example, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first immigration ban towards a specific ethnic group, and was only fully repealed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which abolished the National Origins Formula. Discrimination towards Asian Americans is not as much a “thing of the past,” as some people like to think.

I cannot stress how important it is to know about how we as Asian Americans have reached our current status, thanks to the sacrifices of people like early Chinese laborers, who came to the U.S. hoping to find work, and Asian American activists who fought for our civil rights. I know more about this thanks to heritage museums and cultural institutions like CHSA. I am so grateful to CHSA for filling in the blanks for me and many other young Asian Americans who may not have been taught Asian American history in school.

High school students in Oakland at Black Panther Party funeral rally for Bobby Hutton. (PC: Asian American Movement 1968).

AAPI Month this year has been far sadder than I think anyone anticipated with increasing reports of hate crimes towards Asians. However, I can see a silver lining in the uptick in Asian American activism and with more resources being made available online discussing topics like intersectionality and the history behind the model minority myth. I believe learning and connecting with Asian American history has allowed me to better understand the struggles other minority groups have faced here in the U.S., and I know I need to do more with the privileges I have.

…a diverse community with many voices

Kimberly Szeto, Education & Research Intern

Real talk: I am not the biggest fan of umbrella labels like AAPI, API, etc. There is so much to being Asian American or being Pacific Islander that just gets bunched up into one monolithic category. As people, we are more than what labels and stereotypes define us to be.

But what the labels such as “AAPI” and “API” do instead is bring together a community of people with similar but different backgrounds and give a space to embrace and celebrate who we are, as well as giving us a voice. Yes, May is the month to celebrate AAPI, but why don’t we celebrate all year round? As Asian Americans, we should not have to conform to what “societal norms” in the U.S. constrain us to be, for us to stay quiet and not rock the boat in fear of backlash. Furthermore, we must debunk the model minority myth stereotype, where Asians are seen as uniformly more prosperous, well-educated, and successful than other groups of people. This is a dangerous generalization of vastly different groups of people, one that allows the white majority of America to avoid responsibility for racist policies and beliefs. We need to embrace who we are and educate those who may not know or are less aware.

I started hearing the term AAPI more prominently when I got to college and found a place in the AAPI community at UC Santa Cruz. I think this is where I started to feel more comfortable and began to champion my Asian American identity because I felt like my community was a safe space. I was no longer embarrassed by my family out in public and the customs of our culture that others may have found foreign.

As an Asian American, I think it is very important to keep history and customs alive. That includes our lives here in America as well as the history of those who came before us, and all the triumphs, struggles, and little things in between. These are the experiences that should form the narratives of any human being, no matter where you are from and who you are.

I invite you to celebrate AAPI Month with me, and to encourage you to embrace your own heritage and to educate and support yourselves and others.

#chsa#chsamuseum#chsacomcon#community connections#aapiheritagemonth#AAPIHM#reflections#heritage#asian america#pacific islander

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brave New World: Aunt Wen Fan (nee Tsui) Chao and Uncle Jen-Da Chao

The six siblings, with the youngest and first aunts in the front row left side, accompanied by my cousin, extreme right. (Courtesy of Raymond Lee).

Among my earliest recollections are those of Aunt Wen Fan and Uncle Jen-Da, when I was 3-4 years old. They lived in Taipei near their parents, relatives and close acquaintances. As the oldest of four sisters, she was quick to express warmth, and placed the welfare of others before her own. Her husband was the eldest among four siblings, and shined as the trailblazer of the family. The couple appeared to be settled and content, with my aunt at home raising three children, and my uncle at Taiwan University embarking on a promising career as associate professor of accounting.

In 1977, the couple’s future transformed overnight after moving to the US for the sake of their children’s education and career futures. They were courageous to embark upon a fresh path in an unfamiliar landscape, while fiercely determined to make the journey successful. After settling in San Francisco, they operated a gift stop in Chinatown, in partnership with her youngest sister, Aunt Jane, and her husband, Uncle Joe, located across the street from my parents’ two gift stops. A year later, the Chao family sold the retail business interest and relocated to a township in New Jersey, around the same time my uncle’s siblings were also establishing residencies in nearby communities. The couple struggled to obtain suitable jobs with their limited English fluency and skill-sets. The travails of the Chao family are typical of the experiences among immigrants, but perhaps weighed more heavily in light of the creature comforts they gave up after leaving Taiwan. Over the years, my aunt and uncle faced many challenges beyond the financial, notably bridging the cultural and lifestyle differences between East and West, and ensuring that the next generation would become productive contributors in their adopted country.

Internment of the remains of my aunt and uncle. (Courtesy of Raymond Lee).

Their lives serve not only as testament to how a couple persevered during the best and worst of times, but reveal the depth of their sacrifices for their loved ones. Aunt Wen Fan and Uncle Jen-Da are nothing short of heroic role models for their descendants! Whenever I contemplate the trials and tribulations they endured in this Brave New World, the haunting, poignant passages in Emma Lazarus’ New Colossus (1883) hearken:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Written by CHSA community member, Raymond Lee. Lee was born, raised, and educated in San Francisco Chinatown. Raymond and his wife reside in Winnipeg, Canada. He is currently employed at the Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba.

#CHSA#chsamuseum#community#communityconnections#familystories#aunt#uncle#taipei#taiwan#sanfrancisco#sfchinatown#sanfranciscochinatown#chinatown#newjersey#bravenewworld#EmmaLazarus#NewColossus#chineseamerican#Chinese American

1 note

·

View note

Photo

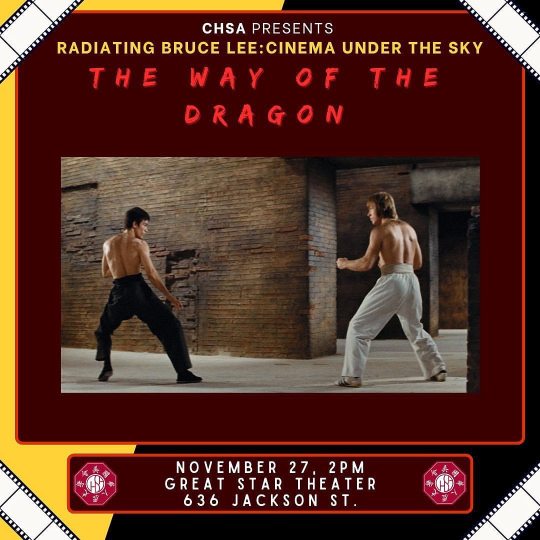

If you’re a fan of Bruce Lee don’t miss out on this @chsamuseum presents “Radiating Bruce Lee: Cinema Under The Sky” a film screening series exploring the life and work of the iconic Bruce Lee. Remaining screenings: The Orphan (1960) feat. a teenage Bruce Lee - Saturday Nov 5th @ Great Star Theatre 2-6PM. The Grandmaster (2013) with special screening of “Rhythm of the Dragon” by @delrokz @seti_x + discussion on Bruce Lee’s impact on Hip Hop - Saturday Nov 12th @ CHSA Museum 5-9PM. The Way of the Dragon (1972) plus a panel discussion on Chinese immigration & Restaurants - Sunday Nov 27th @ Great Star Theater 2-6PM. #brucelee #hiphop #martialarts (at Chinatown, San Francisco) https://www.instagram.com/p/CkU02IyrRuD/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Chinatown Gangs’ and Ethnic Studies: One Teacher’s Inside Look

It was 1967 in San Francisco Chinatown. After an ordinary day of work, local schoolteacher Benjamin Tong and his friend George Woo went to Portofino Cafe, a charming European cafe formerly located at 150 Waverly Place. The two friends were regulars there, part of a crowd of teachers, magazine photographers, medical paraprofessionals, musicians, writers, construction workers, cab drivers, and occasional homeless teenage lost souls.

While enjoying their coffee, they overheard a group of foreign-born, monolingual Chinatown street kids -- many of whom were jobless school dropouts or had been kicked out of the house -- plotting to burn down the “gweilo street parade” in retaliation for a white carnival worker supposedly running off with one of their Chinese girlfriends. The youth were referring to an annual white-run street carnival that occupied Chinatown’s streets and Portsmouth Square during the Chinese Lunar New Year. This packed event directly interrupted Chinatown business and the community’s holiday celebrations. Despite numerous complaints, however, the City did not address Chinatown residents’ concerns.

Deeply concerned about such a reckless and life-threatening plot, Tong and Woo spoke up.

“Look, you guys live here in Chinatown. If you set fire to the carnival, the flames will surely engulf your homes!” George said.

Their reply was emphatic: “We don’t care, man! Burn them down! There’s no kind of future for us Tong Sahn Doys, anyway! Can’t relate to school. No jobs. All we get is grief around the clock from uptight parents and cops!”

Tong Sahn Doys means “boys of the Tang mountains” in Taishanese, referring to the medieval Tang Dynasty (618 to 906 AD) that was considered a golden age.

Tong, Woo, and other adults at the cafe managed to convince the youth to not follow through on their plan. What continued to trouble them, however, was the disconnect the youth felt from their community. They were frustrated, neglected by adults and left with no purpose or direction in life.

Hoping to improve these boys’ situations, Ben and George drafted written proposals in Chinese and English for bilingual education, job training programs, family counseling, and other social services to present to local public schools, social service agencies, church organizations, and family associations. Yet despite beginning a good deal of dialogue, which included heated testimonials from Tong Sahn Doys, nothing stuck. None of the agencies and organizations followed up with concrete, viable commitments for improving the youth’s lives. Instead, their failure to support those in need deepened the rupture in the already fragile relationship between the restless youth and the community members trying to help them. Eventually, many of these disillusioned youth turned to “pulling jobs” for criminal organizations to make a living. They were soon branded the “Chinatown Gangs” by the news media.

In the wake of the failed intervention, the community members who had tried to turn the situation around drew the following conclusion: “We’ve lost this generation. We have failed these youngsters. Their fate is dark now. They’re running out of control, turning on each other as well as ‘the establishment.’”

But not all hope was lost. One evening at the Portofino Cafe, a lightbulb suddenly went off in the heads of Tong and other demoralized individuals who wanted to help the youth. Inspired by the education reformations that African American student activists demanded at San Francisco State College, they wanted to do the same for Asian American students: create a curriculum that examines the history, stories, and nuances of the Asian American community. They hoped that an education which teaches youth about their identity will help them discover a path and purpose as a minority in America.

In the late 1960s, the Black Student Union of San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University) began advocating for better access to educational opportunities, as well as for the creation of a Black Studies program in response to the exclusion of nonwhite communities’ experiences from university curricula. But progress on these demands for a more representative education was slow, and the students’ frustration grew. Finally, during the 1968-1969 academic year, what started as a small protest group grew into a multi-ethnic coalition as other minority student organizations representing Latin American, Mexican American, and Asian American students joined in to support the movement. This multi-ethnic coalition became known as the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF).

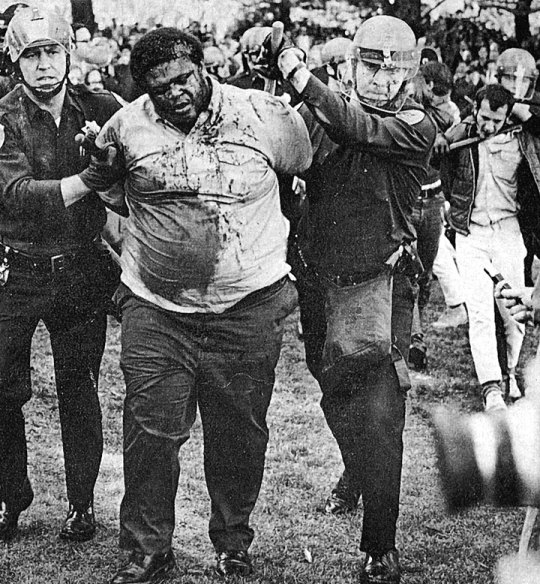

Police attack and arrest protestors at SFSC. (PC: Shaping San Francisco Digital Archive).

Eventually, TWLF began to boycott the university. For five months between November 1968 to March 1969, protestors formed a column of student and faculty protesters that continuously marched around the entire college, making it so that the few students who attended class had to weave through an impenetrable crowd. Tong was among the leaders who represented the Asian American interests. He spent many hours gathering students and faculty to support their efforts. As a participant in this long march, Tong himself wore through three pairs of shoes. Many of these protests were violently broken up by the police. Nevertheless, students persisted, and a similar movement even took place at UC Berkeley.

Eventually, the universities could no longer handle the situation. After negotiating with the leaders of San Francisco State College’s TWLF, they provided the funding and classroom space for the creation of the College of Ethnic Studies, the first of its kind in the entire United States. Similarly, UC Berkeley established the Department of Ethnic Studies. Students could now take classes in American Indian Studies, Asian American Studies, Africana Studies, and Latino/a Studies.

Tong became one of the original faculty in Asian American Studies, helping to build the curriculum from scratch. The department aimed to teach Asian Americans and other students interested in Asian American topics about their history, unique American influenced identity, portrayal in media, and generational cultural differences among many other concepts. In other words, it was a place for students to understand the history of and engage with their cultural identity in America, asking questions such as “What does it mean to be Asian in America?” and “How does my Asian identity affect my experience in America?”.

The inaugural SFSU Asian American Studies Faculty. Tong is at the center of the first row. (PC: SFSU Asian American Studies).

Fast forward half a century to today. These classes that examine the impacts of race, particularly those of systemic racism, on people’s lives in America are as important as ever. Learning about not just one’s own racial group, but other racial and ethnic groups’ experiences will enable them to feel empathetic towards each other's triumphs, hardships, and everything in between. Compassion for and willingness to help one another will allow all communities to grow and not leave people behind, as the neglected Chinatown youth were. We must remember how it was the collective action of many minority groups, each of which faced their own unique challenges, that enabled them to all create positive change together. Benjamin Tong pictured the changes he wanted to see in his community -- empathetic, educated, and passionate Asian Americans -- and pursued his vision until it was achieved.

Written by CHSA Intern Tanson Chan. Tanson is a freshman studying business and humanities at Foothill College. The many captivating stories he heard from his elders -- everything from living in San Francisco's Chinatown to serving in the US Navy in WWII and their fight for civil rights -- haveinspired his interest in Chinese American history and wanting to preserve the legacy of its community to continue inspiring future generations.

#chsamuseum#chsacomcon#community connections#aapi#ethnic studies#asian american studies#sf chinatown#benjamin r. tong

1 note

·

View note

Text

Qingming Festival: Ancestral Respect and Honoring the Past

On Friday, May 8, 2009, the day of a full moon, we celebrated the Qingming festival at Long Gang Li (Village of Dragon Hill) in Jiangmen, Guangdong, China.

Kaiping County lies in the southwest region of the rich Pearl River Delta near Jiangmen. Facing the South China Sea, it is a fertile region of vales, glens, and mesas where rice and fishing are abundant. Long Gang Li is located in the Chishui Township of Kaiping County. It lies on the east bank of the Tan River Valley near the glorious emerald Mount of the Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea (Ba Xian Guo Hai).

My ancient village has a long history that extends back to 1506 A.D. during the Ming Dynasty. Its name, meaning “dragon hill,” references the five-clawed dragon used as a symbol of the Chinese emperors. Today, about 250 people of the Zhang Clan, mostly elders and children, live in this village among rice fields, vegetable gardens, tropical fruit orchards, and fish ponds near bamboo groves. It is from this place that my family’s diaspora originated: Six hundred Zhang descendants now live overseas in Southeast Asia and America.

It was this scenery that I saw on my way into Kaiping after a long day’s journey from Los Angeles to Guangzhou. As the van carried my mother, Yu Xinkai (Seen Hoy Chong, neé Tong), and I toward Long Gang Li along a tree-lined concrete road, I saw myriad farm villages of rice fields and fishponds with magnificent watchtowers and villas (diaolou). Bamboo groves, evergreen woods, and emerald mounts surrounded the fertile valleys of the Tan River.

I couldn’t help but think back to the first time I had come here. It had been on a fall day in 2007. We had entered Long Gang Li the same way, the van slowly driving us into the village square on a dirt road. During the commotion of our surprise visit, jubilant villagers poured out of the temple and their homes to greet us. They recognized me as a “fallen leaf” -- Cantonese slang for a returning sojourner -- from America.

Now, on a crisp spring day in May 2009, I had returned just in time to pay my respects to the Zhang ancestors in Long Gang Li.

Long Gang Li

Village of Long Gang Li at Kaiping. (Courtesy of Raymond Chong).

At Long Gang Li, the villagers greeted me with a glorious lion dance (xingshi) set to the sounds of a pounding drum, a beating gong, and a clanging cymbal. Zhang Guangye, the village chief, led an entourage of ten in the dance to celebrate my return. Zhang Huixin, an elder, carried a pitchfork to eagerly ward off evil spirits. They proudly waved their yellow Zhang Clan flag (symbolizing Long Gang Li) and a red Xingshi flag (xingshi meaning “awake lion”). I was deeply humbled by this show of respect.

As we marched to the Zhang Shiquan Temple, the villagers waited for me. I was immensely proud and excited to stand in front of the lion dance troupe with their bright Zhang Clan flag. I respectfully honored Zhang Shiquan, the village patriarch, by bowing with smoky joss sticks (incense) and cups of rice wine.

We proudly marched along a path lined with the colorful flags of Zhang Clan, Long Gang Li Kung Fu School, Long Gang Li School, and Xingshi to the Zhang Shiquan Temple.

Xingshi for Zhang Weiming at Long Gang Li. (Courtesy of Raymond Chong)

I humbly greeted the elders at the entry as I entered the temple, where the altar of the village patriarch stood, lit by a pair of red candles. I honored Zhang Shiquan by bowing and leaving joss sticks, paper money, and rice wine at the altar. Xu Lianti and Huang Caiyun, elderly ladies, carefully managed the ancestral respect ritual. The lion dancers heartily entered the temple to pay respect to our Zhang ancestors and bless the offering of baked geese and steam buns to Zhang Shiquan. Together, they danced and bowed in front of the Zhang Shiquan altar. Villagers lit firecrackers at the end of the ritual to scare the evil spirits away.

At the time, I was overwhelmed by the significance of the moment, but felt utterly jubilant to finally be able to respect the Zhang ancestors. In 1932, Zhang Baoshen, my father, left Long Gang Li as a young boy to move to America. He never returned to his village, for he died in 1979 at Los Angeles. Now, 77 years after his departure, I proudly represented my father as a “fallen leaf,” a returning sojourner from America to China.

Zhang Shiquan temple at Long Gang Li. (Courtesy of Raymond Chong).

Altar of Zhang Shiquan and his wife within the temple. (Courtesy of Raymond Chong).

In Cantonese culture, ancestral respect is an important tradition. The good fortune of a person is associated with the happiness of his ancestral spirits. Three bows show respect to one’s ancestors in heaven. A pair of red candles at the altar lights the way out of darkness. Flowers symbolize respect and remembrance of ancestors. The smoke of joss sticks represents the ancestral spirits. Hell bank notes (joss paper) represent good fortune to the ancestors. Food is offered to the ancestors, rice wine is poured on the ground for them to drink, and firecrackers are set off to scare away evil spirits.

At my ancestral house, I joyfully met with relatives from Hong Kong. In the parlor above us, I sensed that the spirits of our ancestors were happy with our family reunion. With Huang Cuixiao, my cousin, we repeated the ancestral respect ritual in the parlor in front of the Zhang family altar.

Inside my ancestral house. (Courtesy of Raymond Chong).

Fei E Shan

Later that morning, about 50 people trekked to the Fei E Shan (Hill of the Flying Swan). Shaped like a swan, the hill symbolizes graceful love, and is where we respect the Zhang ancestors in the tombs. Two porters carried the offerings and supplies on the trail. We hiked through the eucalyptus forest over fern-covered ground. The song of cicadas echoed through the rainforest. Blue swallows flew and black butterflies fluttered above us.

On this sacred ground, the tombs were laid out in accordance to fengshui fashion facing Ping Lake (Ping Hu) below the Mount of Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea. At the tombs on the slope, we offered many plates of cooked geese, pork, eggs, and buns to five generations (the 37th-41st generations) of Zhang ancestors in two rows of tombstones. My Zhang forefathers, the sojourners, are buried there: Zhang Chunzan, the California Gold Rush miner; Zhang Bingyao, the Transcontinental Railroad worker; and Zhang Peilan, the Boston Chinatown gambler and opium merchant.

Burning red candles and joss sticks were placed in front of the tombs. Paper tomb flowers adorned the tomb mounds. Paper money lay on the ground for burning. Everyone repeated the ancestral respect ritual and bowed three times with joss sticks, paper money, and rice wine. I scattered bits of bread and eggs. Zhang Guangye quickly passed out the lucky money, with envelopes with “Healthy,” “Wealthy,” “Happy,” and “Come Back” written on them. We reverently feasted on the food for our lunch.

During a quieter moment, I touched the coarse tombstones of my eight ancestors. In poignant solitude, I sensed their gentle presence. I smelled the sweet fragrances of the wildflowers, soapwort, redbud, and eucalyptus of the monsoon rainforest. In the serenity of the moment, I gazed upon the towering peak of Shi Jin Shan and the crystalline Ping Lake as it shimmered during the late afternoon.

Respectful bowing to Zhang ancestors at their tombs on Fei E Shan. (Courtesy of Raymond Chong).

As I marveled at the panorama of the Fei E Shan, I was spiritually impressed and humbled.

Muse

My soulful odyssey to Long Gang Li has led me to my spiritual awakening in search of my Zhang clan ancestral roots. I have learned and absorbed knowledge of my Cantonese heritage. My very essence had truly transcended in this fantastic odyssey from who I used to be, an insolent and surly young American boy who resented the Cantonese traditions of the past, to who I am now, a humble and reverent Cantonese man who respects his Zhang clan ancestors. A precious part of my heart will always dwell in Kaiping.

My Zhang clan ancestors from Canton have etched a subliminal mark on my mind. They are always in my blood, in my bones, and in my thoughts. Because of their influence, I can proudly call myself a real American with true Cantonese roots.

Even now, living in America, I am indelibly rooted at Long Gang Li in Kaiping, with my Zhang clan ancestors of Canton. I have finally come full circle as a fallen leaf.

Written by Dr. Raymond Douglas Chong (Zhang Weiming). Born and raised in Los Angeles, Dr. Chong is a sixth-generation Chinese American with family roots in America extending back to the California Gold Rush. Learn more about his family story and personal odyssey at CHSA’s screening of Dr. Chong’s documentary MY ODYSSEY: Between Two Worlds this Saturday at 1 PM PST.

0 notes

Photo

Don’t miss the finale screening & special panel • Posted @withrepost • @chsamuseum Join us on Bruce Lee’s birthday for a special screening of THE WAY OF THE DRAGON [1972], accompanied by a round table discussion on Bruce Lee’s enduring multicultural legacy. WHEN: Sunday, November 27, 2PM WHERE: Great Star Theater, 636 Jackson St, SF Chinatown The only complete film written and directed by Bruce Lee, The Way of the Dragon begins as a Chinese immigrant saga in a restaurant in Rome. The finale is a kung fu duel for the ages at the Roman Colosseum, with Chuck Norris against Lee’s trickster arsenal of squalling calls, float-like-a-butterfly footwork and a full force of unleashed fist strikes and kicks, as stunning in the beauty of their rapid-fire execution as in their lethal power. Panel discussion will begin with the roots of Bruce Lee’s martial arts in Hong Kong and track its travels to California, mixing and building a multicultural environment. Panelists include: ▪️Adisa Banjoko – Hip Hop blogger & professional Jiu Jitsu teacher ▪️Anthony Chan – International martial arts champion & Chinese American kung fu master ▪️Jeff Chinn – Bruce Lee collector & consultant to the Bruce Lee Foundation ▪️Rahman Jamal – Founder of the Afro Bushido Academy, the Rap Force Academy & the Hip Hop Congress ▪️Mandeep Sethi – Emcee, hip hop artist & filmmaker ▪️Malik Seneferu – Artist & educator For more information or for tickets, visit CHSA.org or link in bio. . . . . . #RadiatingBruceLee #WeAreBruceLee #BruceLee #BruceLeeMovies #TheWayOfTheDragon #MartialArtsMovies #KungFuFilms #ChinatownSanFrancisco #GreatStarTheater #bruceleebirthday (at The Great Star Theater) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ck_1-nJS0hf/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#radiatingbrucelee#wearebrucelee#brucelee#bruceleemovies#thewayofthedragon#martialartsmovies#kungfufilms#chinatownsanfrancisco#greatstartheater#bruceleebirthday

0 notes