#Chinatown dragon parades

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

They made a statue of ryujis tattoo thats so wild

#snap chats#there was a part two to LNY !!!!! there was a parade in chinatown :) my favorite part of LNY 🤤#figured id get a lil dragon for the new year :) ignore the lion puppet i got yesterday i cant make him rgg relevant#parade was so funny tho i got there three hours early OEDJSOZKD#they gotta not advertise it bein at 11AM only for the lions to come at 1:30PM…#also everyone kept calling them dragons and :) Respectfully they arent dragons#there ARE actual dragon shows but … lbr the lions get the most attention OOP#RESPECTFULLY#goofy as hell while i was waiting this girl walked up to me and was just. Balls Out all#‘hi youre really pretty and i just wanted to ask for your number’ like wow !!!! ok !!!!! hi !!!!! not interested tho sorry !!!!!!#thank you for the ego boost tho. no matter where i go i cant escape bein called cute or pretty this is SO sad#anyway ima eat some donuts i got on the way home and that soup from yesterday I Didnt Eat All Of It Leave Me Alone#happy new year 🐲🐲🐲🐲

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOC Interview: Awkwafina on Lunar New Year and 'Kung Fu Panda 4'

I got to talk with Awkwafina about her role as Zhen in Kung Fu Panda 4 from Dreamworks Animation, and her role as Grand Marshall of the San Francisco Lunar New Year Parade, which took place last Saturday to close out the Lunar New Year 2024 observance and celebration. Continue reading NOC Interview: Awkwafina on Lunar New Year and ‘Kung Fu Panda 4’

View On WordPress

#Asian American#Awkwafina#chinatown#Chinese Food#Dragon#Dreamworks#Dreamworks Animation#Interview#Jack Black#Karaoke#Korean food#Kung Fu Panda 4#Lunar New Year#nora lum#Parade#Renfield#San Francisco#Shang-Chi

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#LunarNewYear

#NewYorkCity

#Manhattan

#Chinatown

#CanalStreet

#YearOfTheSnake

#Parade

#Dragon

#BriceDailyPhoto

#LunarNewYear#NewYorkCity#Manhattan#Chinatown#CanalStreet#YearOfTheSnake#Parade#Dragon#BriceDailyPhoto

0 notes

Text

viernes

How did you ring in the new year? Was it a big event for you? What does it mean to you? Has it or does it make a big impact on your life? I ask out of curiosity, in my world the moving into a new year, is a very personal and exciting time, not so much because it is a reason to celebrate and party, but because it is a milestone, one I can reflect on, and review all the goodness and positives that…

View On WordPress

#Chinatown#Chinese New Year#Dragon parades#incense#live entertainment#new year celebrations#original music#saxophone#The Trow Boa Experience#The Warehouse Speakeasy

1 note

·

View note

Text

Last Day of the Year of the Dragon!

Here are some videos I took during the dragon parade at Chinatown in Los Angeles, California.

youtube

#chinese new year#dragon#year of the dragon#chinatown#los angeles#parade#new year's eve#new year's eve 2024#happy new year#new year's day#I had to post it on YouTube#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Halloween 2023, NYC.

Life was great as Kool-Aid Man, but things took a dark turn at the end.

Before I suited up I had wondered aloud whether anyone under the age of 30 would even know who Kool-Aid Man is.

Turns out EVERYONE knows who Kool-Aid Man is. In Chinatown? OH YEAH Kool-Aid man is a star. In the parade? Kool-Aid man is stopping traffic because people want to take pictures and maybe hug.

I have never felt more beloved than I felt as Kool-Aid Man. I realized that this experience was the culmination of billions and billions of dollars of global advertising directed towards impressionable children over the course of decades. It felt great. Money well spent, both for my personal experience on halloween and I'm sure for selling Kool-Aid. The people love Kool-Aid man. OH YEAH!!!!! I am yelling OH YEAH all night long like a broken promotional record. I delivered priceless brand value for somebody at Kraft, if only there were a way to measure and surface all the photos and count the impressions.

Apparently Kool-Aid Man also made some notable cameo experiences on the family guy? A lot of people were yelling OH NOOOOOOO!!!! in a type of call and response. No matter what anyone said to me there was only one thing to say. OH YEAHHHHH!!!

Anyway, there are probably thousands of pics of Kool-Aid Man from halloween parade. I got so many hugs, so many high fives, and probably a few low grade assaults (born of love and longing and good humor I am sure) that I couldn’t really see or understand as they were happening bc the costume was so big. At some point a small child ran up to me and beconned me back to take a picture with his family. We walked pretty far to get back to them. I walked along the fence, and gave a long line of high fives. Even when people got up close, I had a lot of personal space in my joyous red bubble. I felt safe and delighted to bring joy to so many. It felt like a very fun obstacle course inside a balloon. No one could see me through the suit, but as Kool-Aid Man, I felt SEEN. OH YEAH!!!

After the parade, we stopped to take a lot more pictures and after a few blocks I was feeling ready to get out of the suit. I stepped over towards a sort of doorway to take a picture w some girls, but also get out of the flow of traffic, which was a bit chaotic as all the costumes people get out of the street and onto the sidewalk.

All of the sudden, some guy ran through yelling and laughing and grabbed me and sort of pummeled the suit and it popped. Suddenly I am very alarmed and swimming in red nylon. The joyous bubble had been rather forcefully burst. Had someone stabbed Kool-Aid Man in the face??? The beautiful and kind ladies who I had just taken a picture with when it happened were yelling at the guy with "Hey that is not cool! that's a girl in there!!!" or something like that, and definitely implied a certain deliberately extra untowardness from the assailant. It happened really fast and my halloween companion in a dragon mask doesn't really have great visibility either, but he said it was a fully grown man in a white hoodie who ran off into the night. It was quite shocking to me and everyone around me, and I think people were rattled that somebody would do that. I definitely was. Even though I got out of the suit fast, it was obvious that fixing Kool-Aid Man would not be a straightforward tape job- the seam had blown out around the plastic that forms his nose. It was hard to go from feeling like "wow this is the best halloween ever!! this might be a top 10 greatest night of my whole life lol! OH YEAHHHH!!!" to wondering whether I had just gotten stabbed in the face.

I really, really, really wanted it to be dumb hijinxx not deliberately destructive violence. I loved being Kool-Aid Man! Everyone loves Kool-Aid Man! I got so many high fives! And then some random jerk ruined everything in an instant. We took off our costumes and started the long,quiet walk home through manhattan. I don't think either of us knew what to say really. (oh no)

Looking at the tear in the morning, I've concluded it’s pretty likely that the explosion was an accident. I've had to mend inflatable costumes before and I think if it had gotten deliberately pierced with a sharp object, it would have destructed differently. The nose is blown out on one side and then it's a straight cut extending from top and the bottom of the nose. Like maybe the guy came in for a bear hug and just squeezed just too hard? Or a joke punch for the camera and the suit didn't have enough surface area for the air to escape because i was up against the door? Maybe he was wearing an unseen ring that hit the seem just right when he popped kool aid man in his nose, and then he was so embarrassed he ran off into the night?

Thats’s what I have decided to believe anyway. I refuse to let it spoil the experience because up to that moment it was extremely joyous and fun. a+++ would Kool Aid Man again, I was very much looking forward to it, in fact!

In the end, I remind myself that it's just an inflatable halloween costume, and that people do go too hard sometimes on this day. (and every day! people learn how to act right challenge ugh!!!) I am fine, just got a bit of a nasty shock after all that awe.

Can't cry too hard over spilled Kool-Aid though, especially not with Lil Nas X dressed like a giant used tampon. That really did cheer me up.

Unfortunately this particular Kool-Aid Man costume is discontinued, so I'm looking into tent tape and kite tape to patch up my guy. He's gonna have a face scar like Michael K Williams, and next time I Kool-Aid Man I will do so in his honor. Oh yeah. Resilience Baby.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

Today at the Lunar New Year parade in Manhattan Chinatown, a group that I’m a part of @asians4palestinenyc called attention to Palestine during the biggest Lunar New Year celebration in NYC. On Mott and Bayard, one of the busiest intersections in Chinatown, our group infiltrated the parade and unveiled two banners that said “FREE PALESTINE FREE GAZA” and “CEASEFIRE NOW! END THE SEIGE!” with Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Arabic translations. We organized a faction of people at E. Broadway and Market Street where a large group of activists gathered to spread education about the genocide by handing out our zine packages and chanted for Palestine as cowardly politicians made their way through the parade. Our goal is to draw attention to the dire situation in Palestine while celebrating the year of the dragon. This weekend marks 140 days of genocide and over 30,000 Palestinians killed by Israel. It is tradition in cultures who celebrate Lunar New Year to make a lot of noise, wear colorful clothing, and perform lion dances to scare away the bad spirits. Incredibly proud to have been a part of organizing and documenting this action to demand an end to the genocide and a permanent ceasefire in Gaza.

-- Cindy Trinh, 25 Feb 2024

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Fourth of the Future” color lithograph on paper by Henry Barkhaus (1865-1886), published in The Wasp, volume 15 (July-December 1885), July 4, 1885, pages 8-9 (from the collection of The Bancroft Library).

Celebrating the 4th: Chinatown's 1890 Coming Out Party

On this July 4, a cartoon inspired by the Chinese America of 1885 is considered both for both its satirical and prophetic qualities. For nearly a century (1856-1935), The Illustrated Wasp, later known simply as The Wasp, was among California's most popular tabloids. It thrived particularly in the late 1870s and early 1880s, especially under the editorship of Ambrose Bierce from 1881 to 1886. As a weekly publication, it covered San Francisco's social, political, and commercial scenes, featuring a mix of local and international news, social commentary, numerous advertisements, and topical humor.

The Wasp’s written content was often complemented and overshadowed by intricate full-page illustrations, many focusing on the contemporary issue of Chinese immigration. These illustrations vividly depicted the discrimination and prejudice faced by the Chinese, highlighting, according Bancroft Library curator Theresa Salazar, the “struggle to survive as individuals and communities as well as the issues that dominated the imagination of their white contemporaries.” Salazar writes about the vivid illustration which appeared in The Wasp on July 4, 1885, as follows:

“The cartoon, published just three years after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, imagines the Fourth of July parade in San Francisco with racial roles completely reversed. The Palace Hotel is filled with Chinese occupants who look down on the parade, led by an Uncle Sam wearing a formal Chinese ceremonial costume and followed by a large American flag with a dragon supported by a string of Chinese firecrackers. A Chinese policeman beats a white tramp while Chinese boys throw stones at a white businessman. On the corner, the “Chinese Call” newspaper is for sale, an obvious reference to the San Francisco Call, just behind an orientalized Mexican selling tamales. In the building to the right a white barber is giving a haircut beneath a sign reading “M U G K DE YOUNG BARBER,” another obvious reference, to Michael H. De Young, the owner of the San Francisco Chronicle. In the room above, a Caucasian laundry advertises its services as ‘AH SCOTT WASHING AND IRONING.’”

Although Barkhaus’ illustration was patently satirical, some elements would prove to be prescient a century later, such as Chinese policemen, a parade down Market Street (currently part of the main procession for the city's annual Chinese New Year parade), thousands of Chinese American spectators (with more women, unlike 1885) lining the route in front of the Palace Hotel. Even the cartoon's mash-up with Japanese motifs, such as a dragon on a fanciful rendering of a Japanese-style mikoshi borne by loincloth-attired Shinto-esque adherents, would also presage Japanese American participation in future civic festivities.

In pre-1906 San Francisco, the Chinese community in Chinatown would have been well aware of American holidays such as July 4th. Independence Day celebrations appear in the earliest images of pioneer San Francisco.

Fourth of July parade passing in front of Old St. Mary's Church on Dupont Street in 1864. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the San Francisco Public Library). The description on the verso reads: “Day Before Bank Opened--Fourth of July parade 1864 on Dupont Street, now Chinatown’s Grant Avenue, San Francisco. Note Old St. Mary's Church, and sparsely built Telegraph Hill in background. This photo was taken just 1 day before The Bank of California first opened 100 years ago on July 5, 1864.”

Hence, the artist Barkhaus undoubtedly drew on his past observance of Chinese parades and foreshadowed Chinese participation in general July 4th celebrations just five years later.

Most Gorgeous Chinese Pageant Ever Witnessed in San Francisco,” photo feature from The Call Sunday Magazine Section, San Francisco Sunday, July 16, 1890, describing Chinese participation in San Francisco's observance of the July 4 holiday of that year. The photographers are uncredited in this 1890 spread. However, the square center photo of three children is identical to Hortense Schulze’s photo titled “Taking the Air with Sister,” copyright-claimed in 1899.

“Taking the Air with Sister,” 1890. Photograph by Hortense Schulze printed in The Call, July 16, 1890, and reprinted (with claimed copyright 1899) for the “Babies of Chinatown” article written by artist Mary Davison for The Cosmopolitan, An Illustrated Monthly Magazine (vol. 28, no. 6) of April, 1900 (pp. 606-612).

As a feature story and photo spread in The Call newspaper of July 16, 1890, observed, Chinese participation in US Independence Day festivities appeared to have been “tentative” in San Francisco until the last decade of the 19th century. Chinatown was no stranger to elaborate processions through the neighborhood. However, as The Call’s story implies, the lack of participation in mainstream July 4 festivities had reflected hard, learned experience about Chinatown’s uneasy relationship with the rest of the city:

“On previous occasions, when the natives of the Flowery Kingdom were asked to participate in public spectacles – which asking was rare – they took part in a shy, tentative sort of way. Long years of neighboring with the citizens of San Francisco had taught them the lesson that the more they kept to themselves the better off they were. The consequence was, always, when the turned out in parade, they were few in numbers and poor in show. “This year, how different!”

The Call reported that the participation by the Chinese community in the July 4, 1890 celebration was due in large part to the “vision,” intervention, and influence of Chinese Consul General Ho Yow. Significantly, such participation was embraced by the Native Sons of the Golden State (later to be named the Chinese American Citizens Alliance), which organized a Chinese contingent for the parade, channeling the community’s natural capacity for processional logistics and showmanship.

In addition to the photos printed in The Call, images in the collections of the Stanford Libraries and Bancroft Library provide representative samplings of what a typical Chinese contingent carried, and how it appeared, when on the march for parades as Chinatown approached the turn of the century.

Untitled Chinese parade standard-bearers standing in a street in front of white onlookers, probably in San Francisco, c. 1900. Photograph by Hortense Schulze (from an album pending cataloging courtesy of the Manuscripts division of Stanford Libraries). This image is signed and numbered by Schulze in the negative.

Untitled Chinese ceremonial halberd-bearers walking past a gathering of other Chinese (with a mixed group of Chinese and white onlookers across the street and in the left of the frame, probably in San Francisco, c. 1900. Photograph by Hortense Schulze (from an album pending cataloging courtesy of the Manuscripts division of Stanford Libraries). This image is signed and numbered by Schulze in the negative.

Chinese bearing traditional infantry weapons prepare to march in a San Francisco parade. Photographer unknown (from the collection of The Bancroft Library).

Chinese bearing traditional infantry weaponry begin their march in a San Francisco parade. Photographer unknown (from the collection of The Bancroft Library).

Robed Chinese bearing ceremonial pikes prepare to march in a San Francisco parade. Photographer unknown (from the collection of The Bancroft Library).

As The Call reported in 1890, the “kaleidoscopic beauty” and pageantry of the Chinese procession left a lasting impression celebrants and spectators. The lessons learned in the July 4 parade would be reapplied by the Chinese as a tool of civic engagement with the broader community in subsequent years and, most notably, with the public celebrations of Chinese New Years starting in 1953.

As a 1907 photo from Oakland Chinatown indicates, Chinese pioneer communities outside of San Francisco applied their cultural traditions and joined in general American July 4th celebrations.

“Chinese in Parade, Chinatown, Oakland July 4th, 1907.” Courtesy of Ed Clausen Collection. Chinese join in July 4 celebrations a year after more than 4,000 Chinese survivors of San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake and fire found refuge in Oakland, showing a rising spirit of Oakland’s transformed Chinatown.

Although Chinese celebrations were somewhat distinct from the mainstream American observance, fireworks appear to have been a common feature in both Chinese and American festivities. The Chinese community would set off firecrackers and fireworks, symbolizing not just the American independence but also their own cultural heritage, as fireworks are traditionally used in China to ward off evil spirits and bring good luck.

Richard Mark and Thelma Lee pose to light a string of firecrackers in San Francisco Chinatown on July 4, 1934. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the San Francisco Public Library).

July 4 celebrations in Chinatown carried a sense of resilience during an era of exclusion and discrimination. By participating in Independence Day celebrations, the Chinese community asserted its presence and contribution to American society to foster goodwill and improve relations with the broader American public.

During the war years, however, the US Independence Day took secondary importance to events overseas, particularly in 1944 when Chinese communities across the US used early July parades to collect money for war relief in China’s struggle against Japanese aggression.

San Francisco Chinatown observes “Triple Seven” on July 5, 1944, by collecting funds to support China’s war with Japan. Photographer unknown published in the San Francisco Call Bulletin (from the collection of the San Francisco Public Library).

During WW II, China and other diaspora communities commemorated San Ch’i,” or the seventh day of the seventh month of the seventh year of resistance to Imperial Japan.

Overall, the July 4th celebrations in pre-1906 San Francisco Chinatown were a blend of Chinese and American traditions, marked by fireworks and cultural performances. These celebrations were not just about American independence but also intended to express cultural identity and belonging in the face of significant challenges.

#Chinatown July 4th#Consul General Ho Yow#Chinese American Citizens Alliance#Native Sons of the Golden State#Hortense Schulze#Richard Mark#Thelma Lee#Triple Seven WWII celebration#Henry Barkhaus#The Wasp magazine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese New Year: A Global Festival Beyond Asia

Every year, when the first new moon of the lunar calendar begins to wax, a wave of red lanterns, firecrackers, and jubilant parades sweeps over not just Asia but cast its crimson glow across the world. Chinese New Year, also known as Lunar New Year or Spring Festival, is a vibrant and soulful celebration deeply ingrained in Chinese culture and heritage, yet its grandeur resonates with millions globally. Let's embark on a fascinating journey to witness how this majestic festival paints the town red, all around the planet!

The Universal Appeal of Tradition

Tradition doesn't just reside within geographic boundaries; it transcends them. Chinese New Year is a testament to this as communities from Sydney to San Francisco, London to Lagos, come together to embrace the spirit of renewal, hope, and prosperity that the festival signifies. It's a time when the ancient rituals and colorful folklore of the East blend seamlessly with the diverse cultures and modern vibes of cities around the world.

Celebrations Around the Globe

Imagine the thunderous beats of drums and the sharp clack of clashing cymbals; feel the exhilaration as the Dragon Dance snakes its way through the bustling streets of Chinatowns everywhere! From Asia to the farthest reaches of the West, these iconic traditions have found a home, bringing with them a splash of culture and an invitation to communal feasting and reflection.

In Malaysia and Singapore, the streets come alive with decorations and performances, while families gather for the "reunion dinner," embracing the core values of family and community. Meanwhile, in the heart of London, a mesmerizing parade draws thousands, witnessing a fusion of English and Chinese festivities.

Across the Pacific, North America holds its own with cities like New York, Vancouver, and San Francisco hosting grand events - their Chinatowns pulsating with life and festivity, transforming the environs into a microcosm of the East.

A Time for Renewal and Prosperity

As we ring in the New Year with good food and vibrant celebrations, let’s not forget the underlying promise of a fresh start. This is a time to sweep away any ill-fortune and welcome incoming good luck with open arms and hearts full of ambition.

Delving into Diverse Practices

While the essence of Chinese New Year remains constant, local flavors and customs lend each celebration its own unique twist. In Indonesia, it's a national holiday reflective of the country's recognition of cultural diversity. The Philippines, with its considerable Chinese population, revels in street parties and sumptuous feasts celebrating both cultural harmony and delicious gastronomy!

Embracing the Future

As we joyously participate in these world celebrations, let us also remember the profound lessons they impart. These global festivities of Chinese New Year highlight the beauty of cultural exchange and the power of tradition to unite different peoples under the banner of shared celebration. The ubiquity of the festival underscores the universal themes of hope, resurgence, and the communal joy of ushering in better days.

Conclusion

As the brilliant fireworks dissolve into the night sky the world over, Chinese New Year stands as a glistening reminder that joy, much like the full moon, is round and complete when shared. So, no matter where you find yourself when the next Chinese New Year dawns, remember that you're part of a worldwide cadre who's celebrating not just a tradition rooted in time, but the ever-growing tree of human connection. Here's to a New Year filled with happiness, health, and prosperity. Oh, and don't forget to share your festivities with us. Tag us, and let's paint social media red with the splendor of Chinese New Year - together!

Remember, it's not just a festival; it's a global phenomenon that underscores our unity as a global village, festively tied with the reddest of strings. Join in the revelry, indulge in the spirit, and experience the magnificence that is Chinese New Year, wherever you may be. Gung Hay Fat Choy!

#Chinese New Year: A Global Festival Beyond Asia#thekchen choling#chinese new year almanac#chinese new year

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

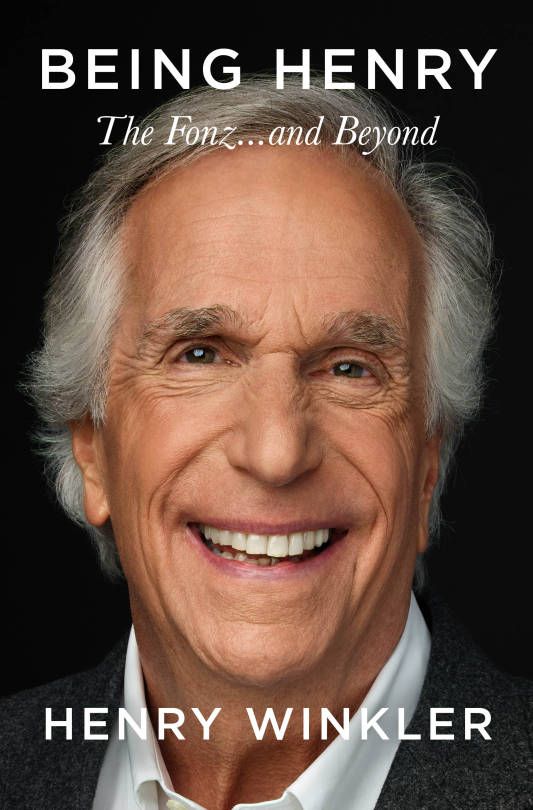

Libby Spotlight: New Memoir & Biography eBooks

Being Henry by Henry Winkler

Henry Winkler, launched into prominence by his role as “The Fonz” in the beloved Happy Days, has transcended the role that made him who he is. Brilliant, funny, and widely-regarded as the nicest man in Hollywood (though he would be the first to tell you that it’s simply not the case, he’s really just grateful to be here), Henry shares in this achingly vulnerable memoir the disheartening truth of his childhood, the difficulties of a life with severe dyslexia, the pressures of a role that takes on a life of its own, and the path forward once your wildest dream seems behind you.

Since the glorious era of Happy Days fame, Henry has endeared himself to a new generation with roles in such adored shows as Arrested Development, Parks and Recreation, and Barry, where he’s revealed himself as an actor with immense depth and pathos, a departure from the period of his life when he was so distinctly typecast as The Fonz, he could hardly find work.

Filled with profound heart, charm, and self-deprecating humor, Being Henry is a memoir about so much more than a life in Hollywood and the curse of stardom. It is a meaningful testament to the power of sharing truth and kindness and of finding fulfillment within yourself.

Daughter of the Dragon by Yunte Huang

Born into the steam and starch of a Chinese laundry, Anna May Wong (1905–1961) emerged from turn-of-the-century Los Angeles to become Old Hollywood’s most famous Chinese American actress, a screen siren who captivated global audiences and signed her publicity photos―with a touch of defiance―“Orientally yours.”

Now, more than a century after her birth, Yunte Huang narrates Wong’s tragic life story, retracing her journey from Chinatown to silent-era Hollywood, and from Weimar Berlin to decadent, prewar Shanghai, and capturing American television in its infancy. As Huang shows, Wong’s rendezvous with history features a remarkable parade of characters, including a smitten Walter Benjamin and (an equally smitten) Marlene Dietrich.

Challenging the parodically racist perceptions of Wong as a “Dragon Lady,” “Madame Butterfly,” or “China Doll,” Huang’s biography becomes a truly resonant work of history that reflects the raging anti-Chinese xenophobia, unabashed sexism, and ageism toward women that defined both Hollywood and America in Wong’s all-too-brief fifty-six years on earth.

First Gen by Alejandra Campoverdi

Alejandra Campoverdi has been a child on welfare, a White House aide to President Obama, a Harvard graduate, a gang member’s girlfriend, and a candidate for U.S. Congress. She’s ridden on Air Force One and in G-rides. She’s been featured in Maxim magazine and had a double mastectomy. Living a life of contradictory extremes often comes with the territory when you’re a “First and Only.” It also comes at a price.

With candor and heart, Alejandra retraces her trajectory as a Mexican American woman raised by an immigrant single mother in Los Angeles. Foregoing the tidy bullet points of her resume and instead shining a light on the spaces between them, what emerges is a powerful testimony that shatters the one-dimensional glossy narrative we are often sold of what it takes to achieve the American Dream. In this timely and revealing reflection, Alejandra draws from her own experiences to name and frame the challenges First and Onlys often face, illuminating a road to truth, healing, and change in the process.

Pulling the Chariot of the Sun by Shane McCrae

When Shane McCrae was eighteen months old, his grandparents kidnapped him and took him to suburban Texas. His mom was white and his dad was Black, and to hide his Blackness from him, his maternal grandparents stole him from his father. In the years that followed, they manipulated and controlled him, refusing to acknowledge his heritage—all the while believing they were doing what was best for him.

For their own safety and to ensure the kidnapping remained a success, Shane’s grandparents had to make sure that he never knew the full story, so he was raised to participate in his own disappearance. But despite elaborate fabrications and unreliable memories, Shane begins to reconstruct his own story and to forge his own identity. Gradually, the truth unveils itself, and with the truth, comes a path to reuniting with his father and finding his own place in the world.

#biographies#memoir#ebooks#new books#libby#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbr pile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

FICLET

The NAFTA trio returns:

“I swear if Vecchio has become MAGA even you won’t stop me from killing him Canadian”, says Anita Cortez, looking absolutely fine and lethal as usual even in her old age.

For his part Benton Fraser, now greyed but no less charming, gave her his very uncomfortable awkward look. He’s not even in uniform but stands parade rest.

Before he could speak Ray Vecchio glides into the room, classically suited still, having overheard. “ You wouldn’t have to. I’d rather shoot myself than work for the clown car that is the FBI and government state again. Now with the guy in charge who even fits the make-up? No. NEVER AGAIN. So explain why we are here?” and he turns mulish eyes on his husband.

“Well Ray, as duel citizens perhaps we can bring some needed clarity of judgment to the discussing parties. About mutual benefits of trades and balances between borders.”

“Oh yes and regulate me to third wheel again? Ay Dios Mio!”, Cortez scowls fondly at them.

“No Fraser, tell her the truth. The reality is we got forced out of retirement by higher Canadian officials who are only a bit less crazy for coco-puffs. I may live in Canada now Benny but boy is it’s governance bi-polar when it comes to how it’s run and also liking you.”

“It's bilingual governance Ray.”

“Well pardon moi. I voted no go.”

“No Ray, in that case it was Yes vote. And technically yes, he’s correct.”

“What I can’t figure out”, Cortez said eager to get them to the point as much as get home to her so much better life than this, “ is why OUR team to train another set? One; We weren’t very high profile. This did nothing for my career the first time aka. thank you but I made my own place as head of a district bringing down a cartel not a PTSD-ed homeless man. Two; no one thought we did a good job before despite actually succeeding. Also, we all hate our governments. Why would they even think we’d be helpful?”

“Because they think they’ll learn from what not to do. And because they always underestimate the cunning of Canada, the sheer bullish loyalty of a true American, and the grit of a surviving Mexico”, said a shadowed figure emerging. One Meg Thatcher.

“Ma'am! Uh Sir”, said Fraser automatically.

“At ease, Constable. Or make that retired Constable. I can’t believe you never got a higher rank but I also can’t say I’m surprised", she said smiling nonetheless.

“Lovely to see you too Dragon-lady”, Ray rejoined.

“I have my mission and I’m entrusting it to you. Impart your wisdom during training. I’m sure you can find some in local Chinatown fortune cookies Vecchio.

— And when that ‘reason’ fails, give these bozos such a massive headache that when they send you all home they can’t even consider what’s put on the trade table because they think we are all equally nuts. Or better, their guards won’t see me coming.”

And thus Meg Thatcher, no relation to that Meg Thatcher, saved the day by destroying NAFTA 2.0.

#due south#fanfic idea#cmon you know they’d all be so miserable in the current political landscape they’d have to troll it#no one was harmed in the making of this#unlike real life#fucking politics

1 note

·

View note

Text

Escape the Ordinary: Finding Paradise in Thailand in February

Thailand, a captivating destination in Southeast Asia, offers a myriad of experiences for travelers, from bustling cities and tranquil temples to pristine beaches and lush jungles. If you're planning a trip to this enchanting country, you might wonder about the best time to visit Thailand. Thailand in February stands out as an ideal choice, offering pleasant weather and a host of exciting events and activities.

February is considered one of the best times to visit Thailand due to its comfortable climate. During this month, the country experiences cooler temperatures and lower humidity, making it perfect for exploring both urban and natural attractions. The northern regions, including Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai, enjoy mild weather, which is excellent for trekking, sightseeing, and exploring the vibrant night markets. In the central plains, Bangkok buzzes with activity, and the pleasant temperatures make it easier to explore the city's rich cultural heritage, from the Grand Palace to Wat Pho and the bustling Chatuchak Market.

The southern part of Thailand, including popular destinations like Phuket, Krabi, and Koh Samui, also enjoys favorable weather in February. The beaches are at their best, with clear skies, calm seas, and plenty of sunshine, perfect for sunbathing, swimming, and water sports. This time of year is also ideal for diving and snorkeling, as the underwater visibility is excellent and marine life is abundant.

One of the highlights of visiting Thailand in February is the Chinese New Year celebrations, which are vibrant and colorful, especially in areas with significant Chinese communities like Bangkok's Chinatown. The festivities include dragon parades, lion dances, fireworks, and a variety of traditional performances, offering a unique cultural experience for visitors.

In addition to the festive atmosphere, February is also an excellent time to enjoy Thailand's natural beauty. National parks like Khao Sok and Erawan are at their most lush and green, providing stunning backdrops for hiking, wildlife spotting, and photography. The cooler temperatures make outdoor activities more enjoyable, whether you're exploring waterfalls, trekking through jungles, or visiting ancient ruins.

Moreover, Thailand in February is perfect for experiencing the country's vibrant festivals and events. Apart from Chinese New Year, the Flower Festival in Chiang Mai is a spectacular event where the city is adorned with beautiful floral displays, parades, and cultural performances. This festival celebrates the region's rich horticultural heritage and adds a splash of color to your visit.

When planning your trip, it's important to book accommodations and activities in advance, as February is a popular month for tourists. Despite the influx of visitors, the country's warm hospitality and well-developed tourist infrastructure ensure a pleasant and hassle-free travel experience.

In conclusion, February is undoubtedly one of the best times to visit Thailand. The combination of perfect weather, cultural festivities, and stunning natural beauty makes it an ideal month for exploring this diverse and enchanting country. Whether you're soaking up the sun on a tropical beach, diving into the rich cultural heritage of Bangkok, or enjoying the cooler climes of the north, Thailand in February promises an unforgettable adventure.

0 notes

Text

the year of the wood dragon 2024

By the time many of you see this post, Lunar New Year celebrations will be mostly past. February 24 is the Lantern Festival, which signals the end of the holiday, which is traditionally 15 days long. [Edit: Both New York City and San Francisco’s Chinatowns are having parades this weekend, so there’s still time to […]the year of the wood dragon 2024

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Immerse Yourself in the Vibrant Celebrations of Chinese New Year in Melbourne

Welcome to the vibrant and bustling city of Melbourne, where the spirit of Chinese New Year comes alive in a spectacular celebration of tradition, culture, and festivity. As the city gears up to usher in the Lunar New Year, Melbourne transforms into a dazzling tapestry of colour, energy, and excitement. From the iconic Chinatown to the heart of the city, the festivities promise a captivating experience that will leave you immersed in the rich tapestry of Chinese culture.

One of the most iconic and lively focal points of the Chinese New Year celebrations in Melbourne is the historic Chinatown. Nestled in the heart of the city, Chinatown comes alive with an electrifying atmosphere, as the streets are adorned with vibrant red lanterns, traditional decorations, and the tantalising aroma of authentic Chinese cuisine wafts through the air. The lively energy of the Lunar New Year can be felt as locals and visitors alike gather to partake in the festivities.

The Chinese New Year festivities in Melbourne are a vibrant and diverse reflection of the city's multicultural fabric. The streets are alive with the sounds of traditional music, dragon and lion dances, and the joyful chatter of people coming together to celebrate. The vibrant parades, cultural performances, and the mesmerising sight of the dragon and lion dance troupes weaving through the streets create an awe-inspiring spectacle that captivates the senses and ignites the spirit of joy and unity.

Throughout the city, a myriad of events and activities are organised to mark the Chinese New Year, offering a delightful array of experiences for everyone to enjoy. From traditional Chinese dance performances and martial arts demonstrations to art exhibitions and calligraphy workshops, there's something for everyone to immerse themselves in the richness of Chinese culture. The tantalising array of street food stalls, serving up delectable Chinese delicacies, provides an opportunity to savour the authentic flavours of the festive season.

Melbourne's iconic landmarks, such as Federation Square and the Royal Botanic Gardens, also play host to a diverse range of Chinese New Year celebrations, ensuring that the spirit of the festival permeates every corner of the city. The dazzling fireworks displays that light up the night sky create a mesmerising spectacle, casting a glow of jubilation and hope as the city welcomes the new lunar cycle with renewed optimism and positivity.

The Chinese New Year in Melbourne is a time of joy, renewal, and the coming together of communities. It's a celebration that transcends cultural boundaries, inviting everyone to embrace the spirit of unity, prosperity, and good fortune. The vibrant tapestry of traditions, customs, and rituals that mark the Lunar New Year serves as a reminder of the beauty of diversity and the enduring power of ancient cultural heritage.

As the city of Melbourne comes alive with the jubilant celebrations of Chinese New Year, it's a reminder of the city's inclusive and welcoming spirit. It's a time to embrace the richness of Chinese culture, to revel in the exuberant festivities, and to join in the collective hope for a year filled with abundance, happiness, and prosperity. So, come and immerse yourself in the magic of Chinese New Year in Melbourne, and be a part of a celebration that will leave an indelible mark on your heart and soul.

0 notes

Text

Singapore's Festivals and Events: Celebrating Diversity

Singapore, a tiny island nation in Southeast Asia, stands as a testament to the harmonious coexistence of diverse cultures. The city-state's multicultural identity is vibrantly showcased throughout the year in a plethora of festivals and events that celebrate the richness of its ethnic tapestry. From exploring the vibrant neighbourhoods during Chinese New Year to witnessing the devotion of Thaipusam, there are numerous places to visit in Singapore that offer a glimpse into its cultural diversity. Additionally, if you plan to visit Singapore in May, you can experience the city-state's commitment to fostering unity through various events and celebrations. These not only reflect the traditions and customs of different communities but also underscore Singapore's commitment to inclusivity, making it an ideal destination to explore both its cultural heritage and contemporary festivities.

Chinese New Year: A Riot of Colors and Traditions

The Lunar New Year, more commonly known as Chinese New Year, is a spectacle that engulfs Singapore in a riot of colors and traditions. Celebrated by the Chinese community, this festival marks the beginning of the lunar calendar with a burst of energy. Streets in Chinatown come alive with vibrant decorations, from lanterns swaying in the breeze to intricate displays symbolizing good luck and prosperity.

The highlight of the festivities is the iconic lion and dragon dances that captivate both locals and visitors alike. Traditional performances, parades, and family reunions define this auspicious occasion, emphasizing the importance of familial bonds and cultural continuity. As Singaporeans exchange mandarin oranges, a symbol of good fortune, the city becomes a mosaic of shared joy and communal celebration.

Thaipusam: A Tapestry of Devotion and Spirituality

In a display of unparalleled devotion and spirituality, the Tamil Hindu community celebrates Thaipusam, a festival that combines religious fervor with striking visual displays. Devotees undertake a pilgrimage from the Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple to the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple, carrying kavadis adorned with flowers and peacock feathers. The rhythmic beating of drums accompanies the procession, creating an atmosphere charged with energy and reverence.

Thaipusam is also a time for personal sacrifice, as some devotees engage in acts of penance such as body piercing and carrying elaborate structures attached to their bodies. The spectacle is not only a testament to the individual's dedication but also a communal expression of faith that transcends cultural boundaries. It is a moment when Singaporeans, regardless of their background, come together to witness a unique blend of tradition and spirituality.

Hari Raya Puasa: A Feast of Unity

The end of Ramadan is marked by Hari Raya Puasa, or Eid al-Fitr, celebrated by the Muslim community. Geylang Serai, a district with a strong Malay heritage, transforms into a vibrant hub of activity during this period. The Ramadan Bazaar offers a sensory delight with the aroma of traditional Malay and Middle Eastern delicacies wafting through the air.

Hari Raya Puasa emphasizes the spirit of giving, forgiveness, and unity. Families come together for prayers and festive meals, exchanging heartfelt greetings and sharing the joy of the season. The celebration extends beyond the Muslim community, with people of all backgrounds joining in the festivities, symbolizing the unity that underlies the nation's diversity.

Deepavali: Festival of Lights Illuminating Unity

The Festival of Lights, Deepavali, brings the Hindu community together in a celebration of light triumphing over darkness. Little India is adorned with vibrant lights, creating a magical atmosphere. Families illuminate their homes with oil lamps, and the streets are alive with cultural performances, including traditional music and dance.

Deepavali is a time for the exchange of sweets, the creation of intricate kolam patterns on doorsteps, and the sharing of joy with loved ones. This festival not only showcases the diversity of Singapore but also serves as a reminder of the common threads that bind the various communities – the pursuit of happiness, prosperity, and the triumph of good over evil.

Chingay Parade: A Multicultural Extravaganza

As part of the Chinese New Year celebrations, the Chingay Parade has evolved into a multicultural extravaganza that transcends ethnic boundaries. Vibrant floats, cultural performances, and a lively procession featuring participants from various communities underscore the unity in diversity that defines Singapore. The parade is a visual spectacle that captivates the imagination, showcasing the collective identity of the nation.

National Day Parade: A Symphony of Patriotism

Singapore's National Day Parade on August 9 is a grand celebration of the nation's independence. The event is a symphony of patriotism, featuring military parades, air shows, and cultural performances that highlight the nation's journey. The National Day Parade fosters a strong sense of national pride, reminding Singaporeans of their shared history and the importance of unity in building a prosperous future.

Mid-Autumn Festival: Lanterns and Unity

The Mid-Autumn Festival, celebrated by the Chinese community, is marked by the lighting of lanterns and the sharing of mooncakes. Gardens by the Bay hosts an annual lantern festival, transforming the area into a mesmerizing display of lights. The festival emphasizes family reunions and the appreciation of the moon's beauty, symbolizing unity and harmony.

Pongal: Harvesting Traditions

Celebrated by the Tamil community, Pongal is a harvest festival that pays tribute to the importance of agriculture and rural life. Families gather for prayers, traditional music, and the cooking of Pongal, a special dish made from freshly harvested crops. The festival is a time to express gratitude for the bounties of the land and strengthen community bonds.

In conclusion, Singapore's festivals and events are a testament to the nation's commitment to celebrating its diverse cultural heritage. These celebrations not only showcase the traditions and customs of different communities but also serve as a powerful reminder of the shared values that bind Singaporeans together. As the city-state continues to embrace its multicultural identity, these festivals play a crucial role in fostering unity, understanding, and a deep appreciation for the richness of its cultural tapestry.

#Singapore#CulturalDiversity#Festivals#Events#Multiculturalism#ChineseNewYear#Thaipusam#HariRayaPuasa#Deepavali#ChingayParade#NationalDayParade#MidAutumnFestival#Pongal#UnityInDiversity#Celebration#Heritage#CommunityHarmony#SingaporeTraditions#CulturalCelebrations

1 note

·

View note

Text

Celebrating the Vibrant Chinese New Year in Singapore: A Fusion of Tradition and Modernity

Introduction:

Embark on an exceptional adventure to experience the magic of the Chinese New Year in Singapore with Trip Cabinet’s exceptional Singapore tour package from Indore. Nestled in Southeast Asia. Singapore combines a way of life with modernity. And the Chinese New Year celebrations show off the metropolis country’s vibrant cultural tapestry. Join us as we explore the captivating festivities. From Chinatown’s astonishing shows to the charming River Hongbao festival, all curated in Trip Cabinet‘s meticulously designed Singapore excursion package.

Festive Preparations:

Months before the Chinese New Year festivities, the cityscape of Singapore transforms right into a charming show of purple and gold, putting the degree for the joyous birthday celebration. With Trip Cabinet‘s expertly crafted itinerary, witness the complex arrangements, such as conventional decorations, lantern presentations, and the bustling atmosphere of streets decorated with auspicious symbols.

Chinatown Extravaganza:

As a part of Trip Cabinet’s Singapore tour package from Indore deal, immerse yourself in the heart of the birthday celebration at Chinatown. Marvel on the Chinatown Light-Up, discover the colorful market streets filled with traditional crafts and bask in delectable snacks. Trip Cabinet guarantees a genuine and immersive revel, permitting you to soak inside the cultural richness of this iconic neighborhood.

River Hongbao:

Included in the tour package deal is an interesting visit to the River Hongbao pageant, held at The Float @ Marina Bay. Experience the grandeur of larger-than-life lantern presentations, cultural performances, and an outstanding fireworks show in opposition to the stunning Marina Bay skyline. Trip Cabinet guarantees you have great vantage points and an unforgettable enjoy at this signature event.

Traditional Practices and Performances:

Because of Trip Cabinet’s excursion package deal guarantees a front-row seat to traditional Chinese New Year performances. Which include the spell-binding lion and dragon dances. Attend the Chingay Parade, a multicultural procession offering colorful floats and captivating performances, showcasing Singapore’s commitment to cultural diversity.

Reunion Feasts in Style:

Celebrate the essence of your own family and meals with Trip Cabinet’s curated reunion dinner revel in. Indulge in a sumptuous ceremonial dinner offering conventional dishes like yu sheng, dumplings, and nian gao, all served in extremely good putting. This is a unique opportunity to partake in the cultural importance of the reunion dinner. Surrounded by the warmth of a circle of relatives and festivity.

Cultural Harmony and Tech-Savvy Innovations:

Trip Cabinet’s Singapore tour package from Indore guarantees you witness the inclusive nature of Chinese New Year celebrations. In which humans of diverse backgrounds come collectively to experience the festivities. Experience the seamless integration of era with conventional celebrations. As Singapore showcases innovative presentations and interactive stories, providing a glimpse into the city’s forward-thinking spirit.

Conclusion:

Embarking on Trip Cabinet’s distinct Singapore tour bundle at some point during Chinese New Year promises unforgettable enjoyment. Witness the seamless combination of culture and modernity, the cultural concord, and the colorful festivities that make Singapore unique. As you welcome the Year of the Tiger. Permit Trip Cabinet to be your manual to discovering the wealthy tapestry of Chinese New Year inside the charming Lion City.

#ChineseNewYear#SingaporeCelebration#YearOfTheTiger#CNYinSingapore#TraditionAndInnovation#ChinatownLights#RiverHongbao#CulturalHarmony#LunarNewYear#TripCabinetExperience#SingaporeTour

0 notes