#SAN GIROLAMO

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

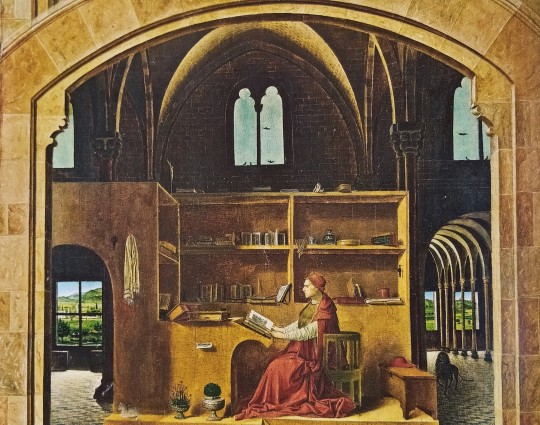

Antonello da Messina, San Girolamo nello studio, ca 1475. Olio su tavola, 45,7x36,2 cm. Londra, National Gallery.

#renaissance art#arte#art#renaissance#antonello da messina#san girolamo#scatti#photo#oil on canvas#london#national gallery#oil painting#painting#aesthetic#study space#studyblr

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leonardo da Vinci, San Girolamo1480 circa, Pinacoteca Vaticana.

“«Omai convien che tu così ti spoltre»,

disse ‘l maestro; «ché seggendo in piuma,

in fama non si vien, Nè sotto coltre;

sanza la qual chi sua vita consuma,

cotal vestigio in terra di sé lascia,

qual fummo in aere e in acqua la schiuma»”.

(Inferno, XXIV, vv. 46 - 51).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sacerdotesse cristiane e pagane

Il sacerdozio morale che le donne esercitano nell’umanità è stato sempre riconosciuto, e i popoli più antichi hanno avuto l’istinto di conferire loro il sacerdozio ufficiale, attraverso il quale le donne ottenevano un’alta missione prendendo parte attiva alle istituzioni religiose. La donna deve tutto alla religione: tra i pagani, il fatto che la donna fosse associata ai misteri religiosi era…

#Alessandro Magno#Apollo a Delfi#Arte#Artista#Atene#Cerere#Costume#cultura#Delfi#di Minerva#Diana#druidessa#Efeso#fdivinazione#l&039;Oracolo a Delfi#Linguaggio#Nerone#Pirro#sacerdotessa#San Clemente d&039;Alessandria#San Girolamo#San Giustino#Sociologia#Storia#Vesta#Vestali

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chiesa di San Girolamo dei Croati (completed 1587)

© optikestrav

(2024)

0 notes

Text

Tableaux Vivants (1969-1989) by Luigi Ontani

#Luigi Ontani#photography#performance#body art#italian photographer#Tableaux vivants#Tableaux vivant#'60s#'60s art#Dante#San Girolamo#Dante Alighieri#Frame#Golden#Art#kitsch#contemporary art#Saint Jerome#70s#'70s#Giuseppe Garibaldi

0 notes

Text

SAN GIROLAMO IN MEDITAZIONE,CANVAS

OPERE DEL FALSARIO DI CARAVAGGIO

#ARTEFALSARIO

#FALSARIODICARAVAGGIO

#COPIEDELFALSARIO

#SAINTJEROMEMEDITATION

1 note

·

View note

Text

Villa Fidelia e Casa di San Girolamo - Spello (PG)

#lovequoteruns#panorami#nature#colori#chiesa#villa fidelia#complesso di san girolamo#spello#fujifilm xt30ii#2500#2501#2502#2503#2504

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1500-1531 Girolamo Marchesi - Portrait of a man

(Museo di San Domenico)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Girolamo Santacroce, Prudenza (1525-28), particolare, Chiesa di San Pietro Martire, Napoli.

#girolamo santacroce#napoli#art history#naples#art#campania#16th century#cinquecento#renaissance#italian renaissance#sculpture#marble

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ogni volta che appare il maestro San Girolamo penso sia una beautiful butch lesbian

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's Good Friday, so let's talk about Botticelli's later works and the influence of Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola!

So, to begin, I did link Savonarola's Wikipedia article above, and if you're unfamiliar with him, I would recommend reading it, but allow me to summarize the relevant bits of information:

Savonarola was born in 1452 in Ferrara and in 1475 traveled to the Friary of San Domenico in Bologna and asked to be admitted. Even before deciding to do so, it is clear that he held the beginnings of many of the beliefs that would make him (in)famous later in his life; even at a fairly early age, he wrote about the corruption of the Catholic Church and the need for it to be scourged, and he shows an early obsession with the Apocalypse. At the friary (and as he is assigned to other locations) it seems that he frequently ran into conflict with leadership, and eventually he ends up under the protection of Lorenzo de'Medici (Lorenzo the Magnificent) in Florence.

Savonarola's preaching in Florence was quite popular; he was certainly charismatic, and he frequently lambasted the wealthy people who neglected the poor (though I should note that his sermons against the wealthy included a healthy dose of antisemitism). Additionally, I should add, the 1490s in Florence (and indeed, the Italian peninsula and...well, really, all of Europe) were somewhat...stressful. There was plenty of political upheaval (which I will circle back to), but the year 1500 was also looming on the horizon. What's important about the year 1500? Well, it was a year that was suggested as the beginning of the Apocalypse. Although, strictly speaking, believing so was a heresy (delving into medieval and early modern Millenarianism is a whole other post, but basically the Church maintains that the date of the Apocalypse will be unknowable until it actually happens and rejects any attempt to say that such and such a year will be the beginning of the end of the world).

Whether or not Savonarola was truly a Millenarian is a matter of some debate, and how convinced he was that 1500, specifically, was a relevant year to the Apocalypse varies even in his own writings and records of his sermons, however. His sermons were filled with a sense of urgency, and when King Charles VIII of France crossed the Alps with his army in 1494 (throwing much of Italy into political chaos as well as war), it seemed that the prophetic nature of his sermons had some truth to them.

Savonarola preached that a New Age was imminent, and that Florence would be a "new Jerusalem" if she could abandon her vices; he claimed that Florence would be spared being sacked by the French (and punishment for her sins) if the Florentines would build an "ark" of piety and penitence; indeed, when Savonarola treated with Charles VIII, an agreement was reached and Florence was not sacked. Piero de' Medici was exiled from the city, and a Florentine republic established, with Savonarola taking a prominent role in the leadership thereof (and in maintaining positive ties with the French).

He was not well liked outside of Florence though; in particular, he had many enemies in Milan and Rome, particularly because he accused the papacy of corruption, and he was eventually excommunicated in 1497. His popularity within Florence also eventually waned. If you have encountered Savonarola in an art historical context before, you have probably heard of his "bonfires of the vanities," where he encouraged people to burn their frivolous or impious worldly possessions; he has been accused of iconoclasm which is not strictly speaking true--he objected to secular art, and to the use of contemporary political figures as models in religious art, and famously decried that late quattrocento artists were depicting the Virgin Mary as a whore, but he was not opposed to "proper" religious art. Still, he was certainly responsible for the destruction of quite a lot of art, and the people of Florence were becoming increasingly fed up with his very strict rules on modesty, asceticism, and so on. In 1498, he (and his close confidants Fra Domenico and Fra Silvestro Maruffi) was arrested; under torture he confessed to inventing his prophecies. The three friars were executed by hanging on 23 May 1498 and their bodies burnt, their ashes scattered in the Arno.

So, Botticelli.

If you're not overly familiar with his oeuvre, you might be surprised to learn that Alessandro Filipepi, known as Sandro Botticelli, was actually quite a devoted follower of Savonarola. After all, his most famous works are certainly the Birth of Venus and Primavera, right? (In the 21st Century, yes. The history of the reception of Botticelli's works is....also a whole other post lol). Still, the works most people associate with him are very much the antithesis of the sort of work Savonarola approved of. Pagan and secular themes! Emphasis on displays of wealth! Female nudity! Using contemporary political figures (including--especially--the Medici family) as models for his religious art!

This is because the works most people associate with Botticelli are from the midpoint--and peak--of his career. However, even before Savonarola's rise to fame, he had begun to switch tacks. Vasari names his later style maniera devota, a term he used disparagingly to refer to a simpler, almost nostalgic style that is very heavy on the piety. As a quick comparison, let us look at two different Annunciation paintings, the first from 1481 and the second from 1489-90 (both currently in the Uffizi):

I will grant that's it not an entirely fair comparison, since the contexts of their production are different and the first is quite a large fresco (243 x 555 cm, or about 8 feet x 18 feet) while the second is a smaller painting (150 x 156 cm), but there is still a noteworthy shift, in my opinion. The fresco shows the Virgin in an incredibly ornate setting; it's very much a testament to Botticelli's skill as a painter, having seen it in person, that you can see so many different textures from the wood grain to the different marbles to the textiles. All of these details point to worldly material wealth. In contrast, the second painting places Mary and Gabriel in a much simpler setting. Although some difference could certainly be attributed to the size, I would point out that textiles and the floor are still rather detailed, but are ultimately humbler materials--rather than an ornate marble floor, the figures are placed on simple terracotta. I would also point out that in the later piece, Mary stands over Gabriel, who is kneeling to her, in a way that suggests her position as the Queen of Heaven--she almost seems to be reassuring him, rather than the other way around. Obviously both pieces are rich with Marian symbolism, and I could sit here all day pointing out each and every detail in them (even in his simpler works, Botticelli, and other quattrocento artists, used enough symbolism you could almost argue that each individual brushstroke was symbolic somehow lol). (Also, all of that said, I will point out that the ornate frame of the second is original).

When, exactly, Botticelli first came into contact with Savonarola's ideas is unknown. There is nothing written by Botticelli himself that is known, and Vasari, though not the first to write about him (he is the first to link him to Savonarola, however), was born in 1511 while Botticelli had died in 1510. Vasari claims in the Vite that Botticelli became a piagnone, who eschewed creating art at all after becoming a devotee of Savonarola's, but this is false; Botticelli continued creating art until his death 12 years after Savonarola's execution--it's quite possible that Vasari was unaware of his later works, though. Botticelli had faced declining popularity since the late 1480s, and was (according to Vasari) reliant on wealthy friends (notably including Lorenzo de'Medici) to live. Additionally, although circa 1500 Botticelli painted at least two very Savonarolan pieces (the Crucifixion above and the Mystic Nativity), the original context of either is unclear. It's even been speculated that one or both of them may have been created for Botticelli's own personal devotional use. Even if they had been commissioned or otherwise intended for public viewing, the intended audience would have been small--continued devotion to Savonarola's ideas was heretical, and although there was not a small number of people who remained devoted to him, they had to do so in secrecy. It's also possible that Vasari confused Sandro for his younger brother, a fellow artist who does seem to have become a piagnone and likely was a follower of Savonarola's before Sandro was, though Sandro's timeline is just....extremely murky from 1491 until his death. The only work of his that can be dated with any certainty after 1491 is the aforementioned Nativity, which includes the inscription (originally in Greek): "I, Alessandro, painted this picture at the end of the year 1500, in the troubles of Italy, in the half-time after the time, during the fulfilment of the 11th chapter of John, in the second woe of the Apocalypse, in the loosing of the devil for three and a half years. Afterward he shall be chained according to the 12th chapter and we shall see him [trodden down] as in this picture."

...So you can see from the inscription that Botticelli believed 1500 to be an apocalyptic year in the literal sense.

You might be able to guess from all of this some of the meaning of the Crucifixion at the top of the post, but allow me to elaborate some anyway. It's dated to around 1500, though, again, nothing after 1491 (except the Mystic Nativity) can be dated for sure. It's tempera and oil on canvas, possibly transferred from panel, and is fairly small, measuring 72.4 cm x 51.4 cm (28.5" x 20.25"). At some point it ended up at the Palazzo Riccardi in Florence, then ended up in Paris, then Munich; it was sold to Edward Forbes in 1924, and Forbes sold it to Harvard's Fogg Art Museum in the same year; it remains there today. The Harvard site has a pretty concise description of it, so I will copy directly from them:

In this painting, perhaps made for his own use, Botticelli incorporates themes from Savonarola’s incendiary sermons. Firebrands and weapons rain down from black storm clouds, and an angel of justice raises his sword to slay the marzocco, the small lion that is the emblem of Florence. The purified city is shown in the background, bathed in light emanating from God the Father, as white angels chase the clouds away. Mary Magdalene desperately clutches the foot of the cross, while a wolf, symbolizing clerical vice, flees from under her robe.

You see the depiction of Florence as a "new Jerusalem," as well as a purification of the Church. The choice of Mary Magdalene as a figure is relevant as well, if you recall that since the middle ages Mary Magdalene was viewed as a penitent former prostitute--her penitence and devotion to the cross here mirror the hope for the city of Florence to redeem itself from its vices and thus attain salvation (and its higher calling as the "new Jerusalem" in the world to come), as well as a hope for the Church itself to be reformed.

Botticelli's works have a reputation of ambiguity among art historians; even for his most well-known works, there's quite a bit that isn't known for certain about intended meanings or even who the figures in the pieces actually are. This Crucifixion is an exception to this, even if other elements of it (such as why it was made in the first place) remain unknown. One of the most interesting things to me about art history as a field is that even for the most well-known artists and works, there's always something that isn't known for sure. The field, and history more broadly, is full of tantalizing mysteries that likely will never be solved. Still, there's always something to be discovered, and, crucially, even in studying what we know for certain (or near enough to certain, anyway) there's immense value in gaining a deeper understanding of historical and cultural contexts. Art and the world are reflections of each other, they interact with each other, and knowledge of one will provide deeper insight into the other.

I think it is important to remember that even Renaissance artists who dealt with pagan themes were deeply Christian, creating art for deeply Christian patrons (and often directly for the Church itself; Botticelli's most known works may have been secular, but he was commissioned for many, many religious works, including working on the Sistine Chapel). It's an important context to be consciously aware of when engaging with their works, even if the specific beliefs are not as obvious as they are here. It's good to remember that artists exist within the context of the world they live(d) in and not isolated from it.

For additional reading and such I recommend:

1) Uffizi site (EN) on the Annunciation (1481)

2) Uffizi site (EN) on the Annunciation (1489-90)

3) National Gallery (London) site on the Mystic Nativity (1500)

4) Charles Burrough, "The Altar and the City: Botticelli's "Mannerism" and the Reform of Sacred Art" (1997) JSTOR

5) Charles Dempsey's biography of Botticelli for Oxford Art Online (2010)

6) Damian Dombrowski, "Savonarola und die heiligen Bilder: Ein Problem der Botticelli-Forschung" (DE) (2009) JSTOR

7) Richard Stapleford, "Vasari and Botticelli" (1995) JSTOR

8) Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Project Gutenberg version tr. 1912 by Gaston du C. de Vere; entry on Botticelli specifically begins on page 245.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bartolomeo della Porta, conocido como Fra’Bartolomeo (Florencia, 1473-1517) La visión de San Bernardo Alrededor de 1504-1507 Óleo sobre tabla Inventario 1890 n. 8455

La Virgen se aparece milagrosamente a San Bernardo arrodillado, detrás de los cuales están San Benito y San Bernabé, en una escena que cautiva por su sugestión emocional y fuerza espiritual.

Es la primera obra que el artista, seguidor del predicador dominico Girolamo Savonarola, pinta tras su ingreso en el convento. La obra fue encargada en 1504 por Bernardo del Bianco para el altar de su capilla en la iglesia florentina de Badia. La composición armoniosa y la sacralidad de las figuras inspiraron al joven Rafael, que estuvo en Florencia entre 1504 y 1508.

Información de la Gallerie degli Uffizi, fotografía de mi autoría.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tiziano Vecellio - San Girolamo penitente

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jérôme all grown up during his Italy years

Portrait of Girolamo Bonaparte, by Pietro Benvenuti

The last of Napoleon’s brothers, born in [1784], Girolamo was a carefree and frivolous young man, often lacking prudence and moderation, who led a life of entertainment. In 1807 he married Catherine, daughter of King Frederick I of Württemberg, and was made king of Westphalia by his brother. After the fall of Napoleon, he left France to reside first in Vienna then in Trieste, Rome and Porto San Giorgio in the Marche. A widower since 1835, in 1840 he secretly married an Italian noblewoman, Giustina Pecori-Suárez (1811–1903), in Florence. Returning to Paris in 1848, he was appointed governor general of the Hôtel des Invalides, then Marshal of France in 1850, president of the Senate in 1851 and was reinstated with the title and honors of Imperial Prince in 1852. He died in 1860; his tomb is located in the cathedral of Saint Louis des Invalides next to Napoleon’s large sarcophagus.

(Source)

#I’m Jerome’s biggest defender#Pietro Benvenuti#Benvenuti#Jerome Bonaparte#Jérôme Bonaparte#Napoleon’s brothers#Napoleon’s family#Girolamo Bonaparte#pandolfini#Palazzo Ramirez-Montalvo#Firenze#Florence#art#Jerome#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#french empire#painting#portrait#cravat#1800s#19th century#auction#nell’asta Dal Rinascimento al primo ‘900 del 2 febbraio 2021

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

San Girolamo scrivente -FALSARIO DI CARAVAGGIO

#ROBERTO BASERGA

#FALSARIO DI CARAVAGGIO

OPERE #FALSARIO

#SAN GIROLAMO#CARAVAGGIO#MERISI#copie#d' Arte#pittura#capolavori#Merisi#Caravaggio#Galleria Borghese#Arte#ROMA#FALSI#painting#paint#pictures#scrivente#falsario#falsario di Caravaggio#roberto baserga opere

0 notes