#Russian Revolution of 1905

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The hall of mirrors that Vladimir Putin has built around himself and within his country is so complex, and so multilayered, that on the eve of a genuine insurrection in Russia, I doubt very much if the Russian president himself believed it could be real.

Certainly the rest of us still can’t know, less than a day after this mutiny began, the true motives of the key players, and especially not of the central figure, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of the Wagner mercenary group. Prigozhin, whose fighters have taken part in brutal conflicts all over Africa and the Middle East—in Syria, Sudan, Libya, the Central African Republic—claims to command 25,000 men in Ukraine. In a statement yesterday afternoon, he accused the Russian army of killing “an enormous amount” of his mercenaries in a bombing raid on his base. Then he called for an armed rebellion, vowing to topple Russian military leaders.

Prigozhin has been lobbing insults at Russia’s military leadership for many weeks, mocking Sergei Shoigu, the Russian minister of defense, as lazy, and describing the chief of the general staff as prone to “paranoid tantrums.” Yesterday, he broke with the official narrative and directly blamed them, and their oligarch friends, for launching the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Ukraine did not provoke Russia on February 24, he said: Instead, Russian elites had been pillaging the territories of the Donbas they’ve occupied since 2014, and became greedy for more. His message was clear: The Russian military launched a pointless war, ran it incompetently, and killed tens of thousands of Russian soldiers unnecessarily.

The “evil brought by the military leadership of the country must be stopped,” Prigozhin declared. He warned the Russian generals not to resist: “Everyone who will try to resist, we will consider them a danger and destroy them immediately, including any checkpoints on our way. And any aviation we see above our heads.” The snarling theatricality of Prigozhin’s statement, the baroque language, the very notion that 25,000 mercenaries were going to remove the commanders of the Russian army during an active war—all of that immediately led many to ask: Is this for real?

Up until the moment it started, when actual Wagner vehicles were spotted on the road from Ukraine to Rostov, a Russian city a couple of miles from the border (and actual Wagner soldiers were spotted buying coffee in a Rostov fast-food restaurant formerly known as McDonald’s), it seemed impossible. But once they appeared in the city—once Prigozhin posted a video of himself in the courtyard of the Southern Military District headquarters in Rostov—and once they seemed poised to take control of Voronezh, a city between Rostov and Moscow, theories began to multiply.

Maybe Prigozhin is collaborating with the Ukrainians, and this is all an elaborate plot to end the war. Maybe the Russian army really had been trying to put an end to Prigozhin’s operations, depriving his soldiers of weapons and ammunition. Maybe this is Prigozhin’s way of fighting not just for his job but for his life. Maybe Prigozhin, a convicted thief who lives by the moral code of Russia’s professional criminal caste, just feels dissed by the Russian military leadership and wants respect. And maybe, just maybe, he has good reason to believe that some Russian soldiers are willing to join him.

Because Russia no longer has anything resembling “mainstream media”—there is only state propaganda, plus some media in exile—we have no good sources of information right now. All of us now live in a world of information chaos, but this is a more profound sort of vacuum, because so many people are pretending to say things they don’t believe. To understand what is going on (or to guess at it), you have to follow a series of unreliable Russian Telegram accounts, or else read the Western and Ukrainian open-source intelligence bloggers who are reliable but farther from the action: @wartranslated, who captions Russian and Ukrainian video in English, for example; or Aric Toler (@arictoler), of Bellingcat, and Christo Grozev (@christogrozev), formerly of Bellingcat, the investigative group that pioneered the use of open-source intelligence. Grozev has enhanced credibility because he said the Wagner group was preparing a coup many months ago. (This morning, I spoke with him and told him he was vindicated. “Yes,” he said, “I am.”)

But the Kremlin may not have very good information either. Only a month ago, Putin was praising Prigozhin and Wagner for the “liberation” of Bakhmut, in eastern Ukraine, after one of the longest, most drawn-out battles in modern military history. Today’s insurrection was, by contrast, better planned and executed: Bakhmut took nearly 11 months, but Prigozihin got to Rostov and Voronezh in less than 11 hours, helped along by commanders and soldiers who appeared to be waiting for him to arrive.

Now military vehicles are moving around Moscow, apparently putting into force “Operation Fortress,” a plan to defend the headquarters of the security services. One Russian military blogger claimed that units of the military, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the FSB security service, and others had already been put on a counterterrorism alert in Moscow very early Thursday morning, supposedly in preparation for a Ukrainian terrorist attack. Perhaps that was what the Kremlin wanted its supporters to think—though the source of the blogger’s claim is not yet clear.

But the unavoidable clashes at play—Putin’s clash with reality, as well as Putin’s clash with Prigozhin—are now coming to a head. Prigozhin has demanded that Shoigu, the defense minister, come to see him in Rostov, which the Wagner boss must know is impossible. Putin has responded by denouncing Prigozhin, though not by name: “Exorbitant ambitions and personal interests have led to treason,” Putin said in an address to the nation this morning. A Telegram channel that is believed to represent Wagner has responded: “Soon we will have a new president.” Whether or not that account is really Wagner, some Russian security leaders are acting as if it is, and are declaring their loyalty to Putin. In a slow, unfocused sort of way, Russia is sliding into what can only be described as a civil war.

If you are surprised, maybe you shouldn’t be. For months—years, really—Putin has blamed all of his country’s troubles on outsiders: America, Europe, NATO. He concealed the weaknesses of his country and its army behind a facade of bluster, arrogance, and appeals to a phony “white Christian nationalism” for foreign audiences, and appeals to imperialist patriotism for domestic consumption. Now he is facing a movement that lives according to the true values of the modern Russian military, and indeed of modern Russia.

Prigozhin is cynical, brutal, and violent. He and his men are motivated by money and self-interest. They are angry at the corruption of the top brass, the bad equipment provided to them, the incredible number of lives wasted. They aren’t Christian, and they don’t care about Peter the Great. Prigozhin is offering them a psychologically comfortable explanation for their current predicament: They failed to defeat Ukraine because they were betrayed by their leaders.

There are some precedents for this moment. In 1905, the Russian fleet’s disastrous performance in a war with Japan helped inspire a failed revolution. In 1917, angry soldiers came home from World War I and launched another, more famous revolution. Putin alluded to that moment in his brief television appearance this morning. At that moment, he said, “arguments behind the army’s back turned out to be the greatest catastrophe, [leading to] destruction of the army and the state, loss of huge territories, resulting in a tragedy and a civil war.” What he did not mention was that up until the moment he left power, Czar Nicholas II was having tea with his wife, writing banal notes in his diary, and imagining that the ordinary Russian peasants loved him and would always take his side. He was wrong.

#current events#history#politics#russian politics#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russian revolution of 1905#russian revolution#russia#yevgeny prigozhin#vladimir putin#wagner group

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

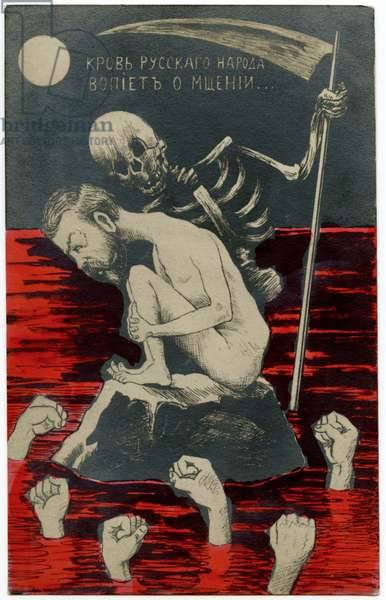

1905 Russian Postcard

The caption in Russian reads: "The Blood of the Russian People Cries Out for Revenge." This is a Russian copy of a French postcard. This dates from the period after the "Bloody Sunday" revolution of 1905, when czarist palace guards shot at protesting crowds, forever burying the Czar's reputation to his people.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Soviets

"The word “soviet” roughly translates as “council.” These workers councils were first formed during the 1905 Revolution to coordinate strikes among workers and broker deals with factory owners. They were seen as a direct embodiment of proletarian power. This association became important to legitimacy of the St. Petersburg soviet after the tsarist regime fell in 1917 and was later used by the Bolsheviks to define the Soviet Union as a workers' state."

Source: Russian History: from Lenin to Putin (Lecture). University of California, Santa Cruz.

#Soviets#Russian History#Bolsheviks#Bolshevik Party#1905 Russian Revolution#1917 Russian Revolution#The Russian Revolution#the Soviet Union

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Soviets

'The workers, naturally enough, were the first to react to Bloody Sunday. Abandoning any hope of support from church or tsar, they turned for advice and organizational support to the opposition, especially to the socialists. The Social Democrats and Socialist Revolutionaries were slow to respond: their leaders were still in emigration, cut off from their potential constituents and preoccupied by heated polemics with one another. Local activists did what they could to improvise meetings, protests, and strikes, and gradually their contact with the workers improved and assumed more organized forms. The result was a new type of workers' association, the Soviet (Council) of Workers' Deputies. First set up in the textile town of Ivanovo-Voznesensk to coordinate a general strike, the soviets were usually elected by the workers of the major enterprises in any given town, at the rate of one deputy for every 500 or so workers. They would meet in a large building, or even in the open air, where not only deputies but also their electors could attend and contribute to discussions. This was a close approach to direct democracy, since, at least in principle, any deputy could be recalled at any time if he failed to satisfy his constituents and be replaced by someone else. The members of each soviet elected an executive committee to deal with day-to-day business and to negotiate with employers, municipality, and police: often they would choose professional people, seeing them as more skillful spokesmen than they themselves could be. Through the executive committees the socialist activists gained influence over the soviets and sometimes directly organized them. The soviets were the best forum for radical intellectuals and workers to cooperate with each other at a time of political crisis. For the workers, they took a familiar form: their general meetings resembled overgrown and disorderly village assemblies, in which everyone tried to speak and mass enthusiasm welled up. On the other hand, the executive committees supplied the element of conscious policy and organization. The soviets' greatest moment came in St. Petersburg in October 1905, when they organized a general strike which disrupted normal production and communications not only in the capital city but over much of the empire. This was the decisive blow which compelled the tsar to grant the October Manifesto, promising civil liberties and an elected legislative assembly.'

Russia and the Russians, by Geoffrey Hosking

#soviets#workers soviets#workers councils#1905 revolution#russian revolution#russian socialism#october manifesto#general strike#direct action#self-organisation#class struggle

1 note

·

View note

Text

IM SO BOREEEEEDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD

#dogstar speaking#this resting shit is annoying!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#but i gotta bc i worked for 2.55 hours this morning and my brain is offline#i think im too tired to read too#since work was. all reading accounts of the 1905 russian revolution.#and next week is the 1917 russian revolution#and brain dont wanna read again!!!!! brain simply tired!!! i have a burgeoning headache!!!!!!

0 notes

Text

I think it's fair to say there is interest in an explanation of trotskyism from a marxist-leninist perspective. Information on what exactly Trotsky did and what trotskyism is nowadays is complicated to come by unless you know a trotskyist willing to be straightforward or someone involved in organizing with these types of communists. So instead of answering these asks without much prior research or preparation, I decided to wait until I was freer, without too many academic and political responsibilities. Full disclosure, the portion of this post on Trotsky himself is essentially (though not completely) a summary of Moissaye J. Olgin's Trotskysim: Counter-revolution in Disguise, which gets into the basics of trotskyism as well as Trotsky's actual position on his contemporary issues, such as the Chinese revolution, or the CPUSA which I don't get into here but I highly recommend reading. The second portion, about modern trotskyism and how it got to be present in the countries that it is, is shorter and more based on my own experiences organizing with trotskyists as well as reading what they have to say, and conversations with much more knowledgeable comrades of mine.

What is trotskyism?

Succinctly, it is the form of left opposition to marxism-leninism that has enjoyed the most spread, spearheaded by Leon Trotsky and his criticisms of the USSR.

Trotsky himself, despite what his self-aggrandizing History of the Russian Revolution leads one to believe, was never a bolshevik, much less a leninist. The second Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party¹ (RSDLP) of 1903, which sought to establish the bases of what would become the bolshevik party and the CPSU, saw the start of the menshevik-bolshevik split, on the issue of what the party should become and how it should be organized.

The bolsheviks, already lead by Lenin, defended the principles of organization that were later systematized into democratic-centralism. These principles were the freedom of discussion until the party decided by a majority vote during a Congress, Conference or other organ for discussion, a position on any issue. After this, unity of action should follow, and the comrades who held the minority opinion, even if they still disagree, should submit to the collectively agreed-upon position, and act on that line an all party matters. This is to ensure that the party of the proletariat, representing the interests of one class, is not divided, and is able to express that single will. Otherwise, its action is crippled by unending debates kept alive by a minority. Consequently, these principles also lead to the intolerance towards fractions within the party.

Trotsky, who aligned himself with the mensheviks, opposed these principles, instead advocating for a complete liberty of individual action of comrades in the party. He called Lenin "the great disorganizer of the party" over this. This is the first great pillar of trotskyism, a rejection of democratic-centralism in favor of the creation of endless cliques and fractions within the party, which he did multiple times within the CPSU until his expulsion.

The second great pillar of the trotskyist opposition that arose before the October Revolution was of defeatism regarding the peasantry. Especially after the defeat of the 1905 revolution, Trotsky was convinced that a successful revolution in a country such as the Russian Empire, where the peasantry was a majority and usually held reactionary positions due to various economic determinations², was impossible because these reactionary elements would inevitably overthrow a worker's dictatorship. While already an excessively defeatist position among other communists, and certainly not a bolshevik position, this belief did not change whether it was 1905, 1915, or 1935. Up to the end, even once the USSR had beaten the armed intervention of 14 armies and had transformed the peasantry by eliminating the class of kulaks and collectivizing agriculture, Trotsky's opposition to socialism in one country relied on the perception of an insurmountable reactionary class constantly on the edge of an overthrow. This is what the "permanent revolution", a term that when used by trotsky has nothing to do with the same term used by Marx and Engels, actually means. A defeatism so deep, that only the practically simultaneous and global victory of the proletariat is possible, all without party unity!

This also negates other leninist positions such as the weakest chain theory, crucial to understanding imperialism, or the necessity of a communist party altogether. Since socialism in one country will inevitably fail, Trotsky told workers that an armed insurrection once the conditions was right was pointless, and that they should instead work for a "worldwide revolution", something that's in practice impossible because it would necessitate a synchronization of the conditions necessary for a revolution in every single imperialist country at once. Unequal development is an unbreakable rule of the imperialist stage of capitalism, and the notion of a worldwide revolution or even a revolution among a significant portion of imperialist countries was already refuted by Lenin in 1915.

So how did Trotsky reconcile his defeatist dogmatism with a living and thriving proof against it in the form of the USSR? As the third great pillar of trotskyism, he insisted by every possible avenue that the USSR wasn't actually socialist, the reasons for which changed constantly. Some issues were already recognized by the CPSU and worked against, and Trotsky exaggerated them. He expressed concern about the Central Committee replacing the party itself, he expressed concern about bureaucratization, the NEP and its lack of collectivization, the excessive speed of collectivization in the 30s, and other criticisms which, when taken together, show only contradiction and a single consistent position: that any attack against the USSR was legitimate.

And it's not like he was being ignored in the USSR, he simply always chose the most incendiary and anti-leninist methods for criticism. In the 13th Congress of the RCP(b) of 1924, among other things, the resolution that was approved recognized many flaws in the party coming out of the NEP, but that these issues weren't actively dangerous and could be solved: bureaucratization in some areas, excessive departmentalization, some influence of bourgeois elements. This resolution was passed unanimously, which included Trotsky. Immediately after the Congress, he published a pamphlet called The New Course, in which he lambasts this Congress and the entire party as having degenerated. In this pamphlet he also places students as the "barometer of the revolution", instead of workers themselves. His only proposal to that Congress was one to allow "freedom of groupings", meaning the freedom to form fractions. Once again he pulled the same stunt in the 15th Congress of 1926; he publicly subscribed to a resolution that explicitly banned such fractions, and directly afterwards published more pamphlets that directly opposed the resolution that he subscribed to! This is not a man who levied fair criticisms and was shut down, he was someone who held minority positions, anti-leninist ones, and refused to admit it, to the point of plotting against the USSR.

But how come Trotsky, during his better known times in exile, claimed he was the true Leninist and that he opposed the Stalinist degeneration? This is the greatest example of a tactic he used constantly. To always seem like the rational critic, and to pass his opposition as one coming from another bolshevik, he always shifted the perspective of his criticisms. In the times of Lenin, Lenin was the "great disorganizer", and the "leader of the reactionary wing of the party"³. But once Lenin died, he became the most loyal foot-soldier of Leninism, crusading against the Stalinist corruption. Then it was Stalin who became Trotsky's devil, effortlessly transposing his criticisms of Lenin to Stalin, and shifting his perspective from that of a menshevik, to that of a true "bolshevik-leninist".

This tactic was used constantly. For instance. when he was still within the ranks of the party, he completely opposed the principles of democratic-centralism, but once he was in exile and had to criticize the Communist International, his issue suddenly became only that the bolshevik form of organization was being hastily applied to different contexts. Then, he really had no issue with democratic-centralism. When he talked of the possibility of a revolution in the US, then all his worries of an insurmountable reaction dissolved, instead becoming an optimist who believed that, actually, there would be no real significant class who would oppose a revolution in the US, and that therefore the USamerican workers should carry out a revolution "without compulsion". The very same person who over the course of decades insisted on the dangers of a counter-revolution apparently believed the workers of the USA had no opposition to fear. This was, rather, simply an opposition to the Communist International's analysis of imperialism, as Trotsky placed the most revolutionary potential in the countries where capitalism was most developed, the imperial core, the very same mistake Marx and Engels committed, except only 70 years prior and with no good framework with which to analyze imperialism. If Trotsky was truly a leninist, then he utterly failed at even beginning to understand anything about the theory regarding imperialism.

I think this is a good enough place to leave Trotsky be, and talk now about trotskyism beyond Trotsky.

Trotskyism, especially in its analysis of imperialism, is very attractive to the imperial core communist. It appeals to multiple sensibilities like individualism, an aversion to revolutionary discipline and work, and impatience. By putting the emphasis away from the party of our class and onto the group of individual ideologues, each with their own cliques and mini-parties, by completely disregarding the possibility of a revolution outside the top of the imperialist pyramid, and by also disregarding the possibility of a revolution until the instance of a total global victory, it is no wonder most trotskyists nowadays are found in the imperial core. This is, with the exception of a portion of Latin-American countries, which I think deserves its own explanation.

Latin America in the 20s and 30s was a continent⁴ of very differing levels of development of capitalism and the proletariat. When many European trotskyists left to Latin America for various reasons, it's no coincidence that they ended up mostly in the urban centers of the most developed countries, such as Argentina and México, where Trotsky himself ended his emigrations after exile. It was exported to places that had a significantly developed proletariat, places which up to that point lacked a culture of multiple communist parties, like Europe had, and places with a strong unionist movement. Other countries like Colombia, Ecuador or Perú, whose worker movements were more significantly indigenist and/or decolonial, along with not meeting the other conditions like Argentina and México, were less ripe for trotskyism.

The condition for a lack of a multi-party environment was important because the trotskyist opposition to the USSR collected all the "orphaned" communists who opposed the sections of the Communist International in each of their countries, especially after the Moscow trials of the late 30s which expanded the opposition to marxism-leninism internationally, as well as with other events like the Hungarian intervention after WW2. But besides this very specific phenomenon, product of a set of very specific conditions which, outside of the imperial core, were only met in these specific countries, the basis of trotskyism as an imperial core opposition to marxism-leninism remains.

So nowadays, trotskyists are mostly located in the imperial core, with those exceptions I've explained. And this leads me to the last part of this post, which is about organizing with trotskyists as a marxist-leninist. In short, it's not impossible but also not an extraordinary situation. Organizing in the imperial core varies from country to country, that much is clear, but the fragmentation into countless groups and sects, as well as the competition with social-democrats, is broadly consistent. These conditions, again generally, mean marxist-leninist parties in the imperial core have to collaborate with a myriad of communist offshoots, anarchists, and ill-defined "leftists" to achieve a broader reach. This includes trotskyists. What makes them in particular uniquely annoying to organize with is that they continue to pretend to be leninists despite all the discrepancies, so they tend to constitute competitors in agitation and rhetoric, while their internal organization usually resembles that of an anarchist group more than anything else. From this, other symptoms like a reliance on assemblyism (especially in the students' movement) and extreme levels of voluntarism naturally follow.

The IMT (International Marxist Tendency), or whichever acronym it is that they're using now, has a relevant presence in just the US and UK with a nominal one in most other imperial core countries. In all cases they're not much more than newspaper vendors who sometimes gives talks at best, and mere reading clubs or financially-extorting sects at worst. There is another international grouping of trotskyist parties that I've come across led by the PTA (Partido del Trabajo Argentino, Argentinian Labor Party), mostly linked via their news broadcast Izquierda Diario, although from what I've heard, the PTA finances their international "children" parties too. Of course, these groups all have different names in each country which in turn tend to change every few years.

Before the split of the Second International during WWI, communists called themselves social-democrats

The mode of production of the peasantry was very individualized, since each peasant or group of peasants lived partly from the fruits of their own labor, they didn't sell it in its entirety. This stands in contrast with the proletariat's completely socialized mode of production; every worker sells the entirety of their labor-power and sustains themself by purchasing commodities with their salary. The pre-existing socialization of production in capitalism was identified by Marx and Engels already in the Manifesto as one of the reasons for the proletariat being the revolutionary class by excellence. The reactionary tendencies of the peasantry wasn't wholly determined by this, it also depended on various historical and contextual reasons, but this should be better expanded on a dedicated post to social alliances.

These are all real insults thrown at Lenin by Trotsky when he disagreed about party discipline. The "true leninist", ladies and gentlemen

Using "continent" in a very loose way here. It's not like the common definitions of continent are very determined either. But you get what I mean

652 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Short, truncated, but hopefully not reductive) Russian history lesson!!!

A perspective that needed to be beat into the dirt when I first started playing Pathologic was that the Bachelor was a city dandy and dandies inherently imply conservatism, which is a British Victorian ideal that has been described like this: "the upper classes were expected to affirm their masculinity through sexual distance, abstinence and self-control," a kind of "cerebral, self-denying asceticism" (Ashish Nandy, The Intimate Enemy; btw). The image of a well-dressed, well-spoken and educated man is found in a lot of core western texts - like Pride and Prejudice, where Darcy is in an ideologically conservative space because he's a part of a protective wealthy class.

But, you know, be careful that bias doesn't drip into your interpretation of Daniil Dankovsky, because his political and social positions are wildly different. The Victorian upper and upper-middle class were historically borne from an accumulation of luxuries brought in through global dominance and colonialism, which drove that subsection of people to the far right. Also, because of this wealth and national expansion, people were moving to cities (to London) in droves. England shifted from a rural to urban-based country. "By 1851 over half the population lived in settlements of 2,500 or more, peaking at around 80 per cent by the 1890s," according to an article by R J Davenport, just to give you some numbers.

Okay, but Russia? "87 percent of the population was rural when revolution broke out in 1905, and 85 percent still rural when it erupted again in 1917" (Dorothy Atkinson, Stats on the Russian Land Commune). Of the small percentage are the intelligentsia, educated people who went to college, which was at first dominated by nobles and then by the turn of the century was overrun by "commoners" (like Dankovsky, who in a monarchical society mostly made of peasants is still beneath high, noble classes)

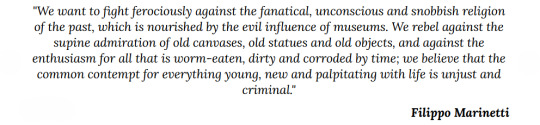

From these commoners came liberal radicals, and from some of these liberal radicals came futurists. This is what Dankovsky is (Futurism/Utopianism. You see).

(Okay, Russian futurists are different from Italian futurists and there were many different types of Russian futurism, but everything came from Marinetti)

This revolution was running parallel to other cultural revolutions inside Russia, inside cities, and parallel to the Bolsheviks. But post-revolution, Lenin condemned the intelligentsia as the chaff between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, in assistance to the bourgeoisie. So they are all summarily stomped asunder.

But this is where the Bachelor is! This is where he's coming from. And I think all modern Russian media that concerns itself with futurism or the culture surrounding 1917 is written with the inexorable knowledge that all of this Utopianism will be usurped by the USSR. Dankovsky may be doomed by the narrative but the narrative itself is doomed by history.

This is not in-depth at all, I'm sorry, but I hope it's serviceable.

#pathologic#daniil dankovsky#sorry also for the insane amount of posts ive made recently#i read the intimate enemy and my brain couldn't calm down#fingers crossed this is the last one#man-of-letters#pathologic 3

353 notes

·

View notes

Text

(limited to Europe because there are limited slots per poll)

*The Long 19th century is the period between the French Revolution and the The First World War.

The French Revolution: The original, the classic. It's got Robespierre and Marat and a Guillotine.

The Serbian Revolution: Resisting Ottoman Rule? Forming a new state? Creating a Constitution? Serbia kicked it off in the Balkans nevermind that it took three tries and three decades.

The Greek Revolution: Have you become hopelessly invested in the idea of Greece as the cradle of civilization? Do you want to die fighting for it in a way that is tragic and romantic? Then you might be Lord Byron.

The Carbonari Uprisings: Secret societies are more your speed? Here is one in Italy doing their best to try to make liberal reform happen.

The Decembrist Revolt: So, a bunch of officers came back from Napoleonic Europe wanting to see constitutional change and possibly the abolition of serfdom. Sounds reasonable, right? Right??

The July Revolution: Can you hear the people sing? You know the one, barricades and the most iconic painting in French history. Louis Philippe ends up on the throne and he is....sexy to someone.

The November Uprising: Congress Poland decides that they are sick of the tsar. Poland undertakes a tragically doomed struggle against Russia.

The Belgian Revolution: The Belgians decide to file for divorce from The United Netherlands. Leopold of Saxe-Coburg ends up on the throne and he's sexy.

The 1848 Revolutions: The Springtime of the People! Revolutions everywhere: France, Hungary, Poland, Austria, The Italian and German States.

The January Uprising: The third time is the charm on kicking out the tsar and making a Polish state, right?

The Paris Commune: Napoleon III abdicates and leaves after being thumped by the Prussians. For two months, a communist people's regime rules Paris.

The Russian Revolution of 1905: This is not the one with Lenin yet! This is the one that forces Nicky to create a Duma. Some consider it the dress rehearsal for what would come next.

#napoleonic sexyman tournament#we need a new tag for extra polls#this is why people like the 19th century by the way#look at all those revolutions

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Implicit in all the attempts to fit the gay movement into various “more revolutionary” categories is the assumption that calling it a democratic rights movement or a reform struggle is somehow a defamation, a downplaying of its importance from the viewpoint of Marxism. Nothing could be less true. No one knows what will spark the next outburst of the class struggle. The overthrow of the Haile Selassie government in Ethiopia (a movement forward, regardless of one’s assessment of the present regime) followed a traffic stoppage that occurred when a taxicab driver in Addis Ababa parked his cab in the middle of the main thoroughfare to protest high gas prices. Two days later 100,000 demonstrated and four days later the government fell. The 1905 Russian Revolution was begun in earnest when Father Gapon led a peaceful march of 200,000 workers to the Winter Palace to petition the Tsar for such demands as freedom of assembly, freedom of speech and the press, and an eight-hour working day. The portrait of the Tsar and church icons that headed the march did not prevent the Cossacks from following orders and killing a thousand workers. The turning point in the Iranian revolution was the refusal of the Shah to heed the demands of democratic rights and economic reforms by the Iranian oil workers, who also marched under portraits of the Shah until they were fired upon.

Marxists support democratic rights struggles not as a matter of sentiment, moralistic well-meaning, or even the illusion that formal gaining of democratic rights is equivalent to a corresponding change in the working class’s consciousness. After all, Holland has had no laws prohibiting homosexual behavior for more than a century. Yet the oppression of gays and consciousness of the working class in regard to the oppression is not markedly different from that in the U.S.

Support and active participation occur because democratic rights struggles have the potential for exposing the true basis of oppression - not that of laws, but that of property relations. Such struggles are not important in and of themselves, but for the potential they have in contributing to the possibility of and showing the necessity of revolutionary change.

When such struggles attain a mass character, whether on their own or because of their initiation by revolutionaries, it is not a question for revolutionary organizations to vouchsafe abstract support but to intervene in such a way that they can aid the struggle materially, learn from the self-activity of the oppressed and critique the limitations of the struggle.”

In Partial Payment: Class Struggle, Sexuality and the Gay Movement

111 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bloody Sunday in 1905: The Massacre at the Tsar's Winter Palace

Bloody Sunday on 22 January 1905 was the massacre of peaceful and unarmed protestors by soldiers outside the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia. The crowd of workers and their families were led by Father Georgy Gapon (1870-1906), who had wanted to present Tsar Nicholas II (reign 1894-1917) with a petition for reforms. Over 1,000 people were killed, and many more were wounded in the incident.

Part of the Russian Revolution of 1905, Bloody Sunday led directly to a general strike and other forms of protest against the Tsarist regime. The protests involved peasants, industrial workers, the urban middle class, and elements of the military. Ultimately, there was no regime change, and the tsar held on to power by promising reforms and a new representative parliament, the Duma. The reforms proved to be disappointing in reality, and, following Russia's disastrous performance in the First World War (1914-18), two further revolutions in 1917 finally toppled the tsar and established a Communist government.

Background: An Unpopular Tsar

Tsar Nicholas II had reigned over the Russian Empire since 1894, but his absolute rule faced a major challenge with the January revolution of 1905, when workers, peasants, and elements of the military all called for political, social, and economic changes and a more representative system of government. A working class of factory workers had sprung up since industrialisation, while many peasants had gained the right to work their own land. The student class had also grown significantly. None of these groups was directly represented in Russia's legal classification of society into four tiers: the nobility, gentry, townsmen, and peasantry. Trouble against the tsar's authoritarian rule had been simmering away for quite some time, with various public disturbances breaking out against state authority. As the historian C. Read notes, "the army dealt with 19 disturbances in 1893; 33 in 1900; 271 in 1901 and 522 in 1902" (74). Politically-motivated assassinations were not uncommon and claimed victims in the police force, local government, and at ministerial level.

The simmering discontent was raised to boiling point by several new factors from 1901 onwards. The formation of worker unions led by police officials – an idea of police socialism, which came from Sergei Zubatov, the Moscow police administrator – backfired as these associations hid radicals in plain sight. The global economic slump of 1901 to 1905, which greatly increased unemployment, and Russia's losses in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5) further dented the tsar's prestige and added to the woes of those who called for political and economic change. Actions of protest became increasingly violent. Vyacheslav Plehve, the conservative minister of the interior, was assassinated by a member of the Union of Social Revolutionaries in July 1904. Just as demonstrators planned to march on the Winter Palace, the tsar's official residence in St. Petersburg, news came of the fall of Port Arthur (in Manchuria) to the Japanese, one of Russia's key fortresses and a major naval base. The tsar was shown to be not only incompetent at running the economy but also at conducting wars.

Read More

⇒ Bloody Sunday in 1905: The Massacre at the Tsar's Winter Palace

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joachim Murats descendants in the (Great War) World war 1

1. Louis Napoléon Achille Charles Murat (1872-1943)

A vivid figure from a family known for its colorful characters, Louis Napoléon Achille Charles Murat was the great-grandson of Joachim Murat, King of Naples. He began his military career in the French Army, serving from 1891 to 1903 and rising to the rank of lieutenant in the 9th Régiment de Cuirassiers (Heavy Cavalry) stationed in Noyon.

With maternal roots in Mingrelia (present-day Georgia), Murat’s path took a dramatic turn when he joined the Russian Imperial Army during the Russo-Japanese War. Following the Russian defeat, he remained in service, riding with the Kuban Cossack Regiment from 1905 to 1909, and later serving on the staff of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich until 1911.

At the outbreak of World War I, Murat was in Argentina. Upon learning of the war’s declaration, he returned to Russia and was assigned to several general staffs. By 1917, he was fighting as a colonel in the 12th Starodubovsk Dragoons. During the Russian Revolution, he joined the White Army, continuing to fight in the Carpathians.

After the civil war, Murat returned to France in 1921, where he made a modest living as a translator. In recognition of his service, he was named a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honor in 1928. He proudly continued to claim his Russian decorations, including the Orders of Saint Vladimir and Saint George, adorned “with all possible swords and citations.”

He passed away in Nice on June 14, 1943,

2. Alexandre Murat (1889–1926)

Alexandre served as a French artillery officer and a direct descendant of the King of Naples. During World War I, he served as a battery commander and was cited for distinction in combat. His commendation praised him for “obtaining from his battery an excellent performance through the precision of fire which he always directed personally from the most exposed observation posts,” and for maintaining morale and discipline “through his calm demeanor and disregard for danger, even amid heavy losses.”

He was one of eight children of Prince Murat who served in the Great War. Among them, Louis Murat fell at the champ d’honneur (field of honor), and several others were wounded—a remarkable testament to the family’s deep involvement and sacrifice during the conflict.

3.Joachim, 6th Prince Murat (1885-1938)

Joachim began World War I as a cavalry lieutenant. He later commanded the Fort des Sartelles during the Battle of Verdun in 1916, where his exemplary conduct earned him the Croix de Guerre with three citations. Subsequently, he served as an interpreter at the General Headquarters of the Royal Flying Corps, based in Saint-Omer from August 1914 to November 1915. After the war, Murat was elected deputy for the Lot in the 1919 French legislative election and served in the Chamber of Deputies until 1929.

4.Prince Charles Murat (1892–1973):

Cavalryman in the Dardanelles Prince Charles Murat brought the legacy of the Napoleonic cavalry to the battlefields of World War I. Initially serving in the French Army, he was later assigned to the Moroccan Tirailleurs, colonial infantry units known for their fierce combat prowess.

During the Gallipoli campaign in the Dardanelles, Charles fought in brutal close-quarters combat and was wounded in the head. His courage under fire earned him one of France’s highest honors: he was named a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur for acts of bravery.

5. Prince Gérôme Murat (1898–1992)

Gérôme took part in numerous operations as a machine gunner with the Salmson, Squadron MF 1, making him an aviator of the Murat family. On February 25, 1918, after an aerial battle over the Vosges, his plane caught fire, forcing him to make an emergency landing. As a result of the incident, he had to have one of his legs amputated.

6. Prince Louis Murat (1896-1916)

A volunteer (registration number 2771/308 - Class 1916), he served as marshal of the houses with the 5th Regiment of Foot Cuirassiers. He went to the front on the night of the 17th to the 18th, in the area of the village of Lihons, on the Santerre plateau in the eastern part of the Somme department, during the Battle of the Somme. He was killed on August 21, 1916, just north of Lihons.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

saw a post like "imagine being born in 1905 and your life just doesn't stop." yeah baby i've imagined it because it happened to my beloved research subject leonia "jelonka" jablonkowna. she was born in lodz during the 1905 revolution and went to middle and high school during WWI, the russian revolution, the collapse of the russian empire, polish independence, and the polish-soviet war. she did an extra module for her matura on the hot new subject of psychoanalysis. she moved to warsaw, dropped out of college, became stefania zahorska's personal assistant, went to drama school, and graduated from drama school in september 1939. she survived WWII but her family was murdered in the lodz ghetto and she converted to catholicism in 1944. she lived through '68 and long enough to see the first solidarnosc protests. when interviewed at the end of her life she was like "i always feel like i didn't do very much" babygirl you bore witness to the whole-ass 20th century. also you were one of the most prolific polish-language theater critics of the postwar period so jot that down

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

the headcanon of hawkeye’s mother being jewish rings very true of course because of hawk’s yiddish and his everything but also considering his mother possibly would’ve been a child of the generation who left the russian empire in the wake of the 1900s wave of pogroms, many of which were instigated by groups assigning blame for the 1905 revolution. the bialystok pogrom was czarist retaliation against the jewish labor bund. imperial military violence carried out in the name of anticommunism

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was wondering if you could recommend me some books about otma? I want to learn more about their hobbies and what they liked etc, I saw some of your posts and you had lots of good information so I thought I might ask

Hello! Thank you for your question. Here are some of the best books about OTMA

Firstly, secondary sources (written in modern times by historians and/or experts)

Romanov Autumn: The Last Century of Imperial Russia by Charlotte Zeepvat is my favourite secondary source on the Romanovs. It has chapters on many different family members, so might not be ideal if you want to learn just about OTMA, but I think it's a great introduction to the topic.

Nicholas II: The Imperial Family by Olga Barkovets and Valentina Tenikhina is a coffee table book, but has lots of photographs of the Romanov's and their belongings and focusses heavily on the life of the Romanovs, rather than politics. There are a few errors in it, but nothing totally egregious. I picked up a copy from a second hand bookstore for $0.99, and it's one of my favourites.

‘After that we wrote.’: A Reconsideration of the Lives of Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanova, 1895-1918 by Althea Thompson is a dissertation/thesis so is more 'academia' focussed than the other books. It's a long read, but very interesting analysis of OTMA's daily lives and their roles.

Primary sources (documents, diaries, letters, etc, from the time)

The girls' diaries and letters have been translated by Helen Azar and various other collaborators under the following titles:

The Diary of Olga Romanov: Royal Witness to the Russian Revolution

Tatiana Romanov, Daughter of the Last Tsar: Diaries and Letters, 1913–1918

Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918

Anastasia Romanov: The Tsar's Youngest Daughter Speaks Through Her Writings

Similarly, Correspondence of the Russian Grand Duchesses: Letters of the Daughters of the Last Tsar by George Hawkins has hundreds of letters that OTMA sent and received. Letters generally show more of their personalities and interests than their diaries, which were mostly a written log of daily activities (but still very interesting and have lovely anecdotes).

Six Years at the Russian Court by Margaretta Eagar was published in 1906, after Eagar left her position as nanny. Therefore, it only has information about when the girls were children, but it is certainly a gem. Lots of information about daily routines and OTMA's personalities. Eagar also wrote several articles for magazines, which have more information and were popular, but they are difficult to track down. Some extracts have been reproduced in From Cradle to Crown: British Nannies and Governesses at the World's Royal Courts. I have two of the articles in my collection and will try and scan and share them soon.

Thirteen Years at the Russian Court: the Last Years of the Romanov Tsar and His Family by an Eyewitness by Pierre Gilliard is, in my view, a must read. Gilliard was tutor from 1905 to 1918, and accompanied the Romanovs to Ekaterinburg before being separated. Lots of information about OTMA's education, their personalities and appearances. A wonderful little book.

Margaretta Eagar and Pierre Gilliard's books were written over a century ago, meaning that they are in the public domain. Therefore, they should be very easy to find free to read online.

Personally I would avoid the two of the more famous/popular books: The Romanovs by Montefiore and Four Sisters by Rappaport. Both have glaring errors and biases. Montefiore's in particular has no references attached to the physical book, so it's difficult to verify the questionable information he shares.

You can find more information about book recommendations here, here, and here. Furthermore, anything that I tag #sources on my blog contain information about OTMA, such as diaries, letters, memoirs, or any other interesting historical info, and are usually referenced. Happy reading!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The revolution of 1905-1907

'On Sunday, 9 January 1905, the workers turned out in their Sunday best and paraded with icons and portraits of the tsar. They proceeded from the various industrial suburbs to the center of St. Petersburg, where they hoped to present their petition. There, instead of the tsar, they found nervous soldiers awaiting them. Drawn up without proper instructions, the troops panicked at the sight of such huge and determined crowds and opened fire, and in the resulting melee some 200 people were killed. It is difficult to overstate the importance of this massacre, which was soon christened "Bloody Sunday." ... Old social bonds had been disrupted; now the basis for new ones was eliminated. The result was a cataclysmic eruption of social disorder, in which all social strata, all regions, and all nationalities of the empire were involved, one way or another, an outburst of manifold grievances and conflicts, many of which had smoldered for decades, gradually accumulating the destructive power they suddenly unleashed now.'

Russia and the Russians, by Geoffrey Hosking

1 note

·

View note