#Royal University Of Law And Economics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#អូន ឌីម៉ង់#demang oun#demang#demeng#ឌីម៉ង់#អូន ឡង់ឌី#citysmile#demeng oun#citysmile.john#da vin#Royal University Of Law And Economics#សាលាភូមិន្ទនីតិសាស្រ្ត និងវិទ្យាសាស្រ្តសេដ្ឋកិច្ច#The Institute of Foreign Languages#Royal University of Phnom Penh#វិទ្យាស្ថានភាសាបរទេស#IFL#ផ្សារបែកចាន ស្រុកអង្គស្នួល ខេត្តកណ្តាល. ផ្សារបែកចាន ស្រុកអង្គស្នួល ខេត្តកណ្តាល#ខេត្តកណ្តាល#ផ្សារបែកចាន#tumblrpost#tumblr👽#tumblrposts#tumblrfeed#tamblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrs#tumblrgram#tmblr#tumblrr#shitposting

0 notes

Text

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific - Part 9

[ First | Prev | Table of Contents | Next ]

There was another factor that contributed to strengthen the religious leanings of the bourgeoisie. That was the rise of materialism in England. This new doctrine not only shocked the pious feelings of the middle-class; it announced itself as a philosophy only fit for scholars and cultivated men of the world, in contrast to religion, which was good enough for the uneducated masses, including the bourgeoisie. With Hobbes, it stepped on the stage as a defender of royal prerogative and omnipotence; it called upon absolute monarchy to keep down that puer robustus sed malitiosus ["Robust but malicious boy"] – to wit, the people. Similarly, with the successors of Hobbes, with Bolingbroke, Shaftesbury, etc., the new deistic form of materialism remained an aristocratic, esoteric doctrine, and, therefore, hateful to the middle-class both for its religious heresy and for its anti-bourgeois political connections. Accordingly, in opposition to the materialism and deism of the aristocracy, those Protestant sects which had furnished the flag and the fighting contingent against the Stuarts continued to furnish the main strength of the progressive middle-class, and form even today the backbone of "the Great Liberal Party".

In the meantime, materialism passed from England to France, where it met and coalesced with another materialistic school of philosophers, a branch of Cartesianism. In France, too, it remained at first an exclusively aristocratic doctrine. But, soon, its revolutionary character asserted itself. The French materialists did not limit their criticism to matters of religious belief; they extended it to whatever scientific tradition or political institution they met with; and to prove the claim of their doctrine to universal application, they took the shortest cut, and boldly applied it to all subjects of knowledge in the giant work after which they were named – the Encyclopaedia. Thus, in one or the other of its two forms – avowed materialism or deism – it became the creed of the whole cultures youth of France; so much so that, when the Great Revolution broke out, the doctrine hatched by English Royalists gave a theoretical flag to French Republicans and Terrorists, and furnished the text for the Declaration of the Rights of Man. The Great French Revolution was the third uprising of the bourgeoisie, but the first that had entirely cast off the religious cloak, and was fought out on undisguised political lines; it was the first, too, that was really fought out up to the destruction of one of the combatants, the aristocracy, and the complete triumph of the other, the bourgeoisie. In England, the continuity of pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary institutions, and the compromise between landlords and capitalists, found its expression in the continuity of judicial precedents and in the religious preservation of the feudal forms of the law. In France, the Revolution constituted a complete breach with the traditions of the past; it cleared out the very last vestiges of feudalism, and created in the Code Civil a masterly adaptation of the old Roman law – that almost perfect expression of the juridical relations corresponding to the economic stage called by Marx the production of commodities – to modern capitalist conditions; so masterly that this French revolutionary code still serves as a model for reforms of the law of property in all other countries, not excepting England. Let us, however, not forget that if English law continues to express the economic relations of capitalist society in that barbarous feudal language which corresponds to the thing expressed, just as English spelling corresponds to English pronunciation – vous écrivez Londres et vous prononcez Constantinople (translation: you write London and you pronounce Constantinople), said a Frenchman – that same English law is the only one which has preserved through ages, and transmitted to America and the Colonies, the best part of that old Germanic personal freedom, local self-government, and independence from all interference (but that of the law courts), which on the Continent has been lost during the period of absolute monarchy, and has nowhere been as yet fully recovered.

[ First | Prev | Table of Contents | Next ]

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

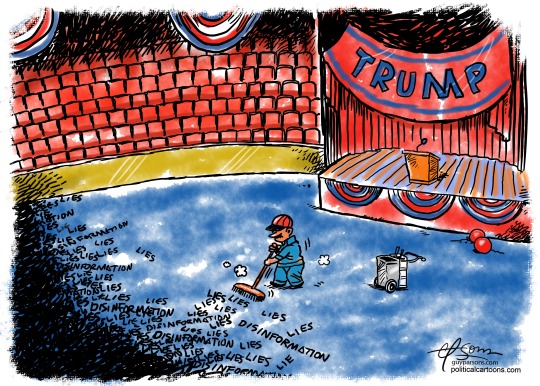

Guy Parsons

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

October 17, 2024

Heather Cox Richardson

Oct 18, 2024

In a new rule released yesterday, the Federal Trade Commission requires sellers to make it as easy to cancel a subscription to a gym or a service as it is to sign up for one. In a statement, FTC chair Lina Khan explained the reasoning behind the “click-to-cancel” rule: “Too often, businesses make people jump through endless hoops just to cancel a subscription,” she said. “Nobody should be stuck paying for a service they no longer want.” Although most of the new requirements won’t take effect for about six months, David Dayen of The American Prospect noted that the stock price of Planet Fitness fell 8% after the announcement.

When he took office in January 2021, with democracy under siege from autocratic governments abroad and an authoritarian movement at home, President Joe Biden set out to prove that democracy could deliver for the ordinary people who had lost faith in it. The click-to-cancel rule is an illustration of an obvious and long-overdue protection, but it is only one of many ways—$35 insulin, new bridges, loan forgiveness, higher wages, good jobs—in which policies designed to benefit ordinary people have demonstrated that a democratic government can improve lives.

When Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen spoke to the Council on Foreign Relations yesterday, she noted that the administration “has driven a historic economic recovery” with strong growth, very low unemployment rates, and inflation returning to normal. Now it is focused on lowering costs for families and expanding the economy while reducing inequality. That strong economy at home is helping to power the global economy, Yellen noted, and the U.S. has been working to strengthen that economy by reinforcing global policies, investments, and institutions that reinforce economic stability.

“Over the past four years, the world has been through a lot,” Yellen said, “from a once-in-a-century pandemic, to the largest land war in Europe since World War II, to increasingly frequent and severe climate disasters. This has only underlined that we are all in it together. America’s economic well-being depends on the world’s, and America’s economic leadership is key to global prosperity and security.” She warned against isolationism that would undermine such prosperity both at home and abroad.

The numbers behind the proven experience that government protection of ordinary people is good for economic growth got the blessing of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences on Monday, when it awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, both of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and to James Robinson of the University of Chicago. Their research explains why “[s]ocieties with a poor rule of law and institutions that exploit the population do not generate growth or change for the better,” while democracies do.

Although democracy has been delivering for Americans, Donald Trump and MAGAs rose to power by convincing those left behind by 40 years of supply-side economics that their problem was not the people in charge of the government, but rather the government itself.

Trump wants to get rid of the current government so that he can enrich himself, do whatever he wants to his enemies, and avoid answering to the law. The Christian nationalists who wrote Project 2025 want to destroy the federal government so they can put in place an authoritarian who will force Americans to live under religious rule. Tech elites like Elon Musk and Peter Thiel want to get rid of the federal government so they can control the future without having to worry about regulations.

In place of what they insist is a democratic system that has failed, they are offering a strongman who, they claim, will take care of people more efficiently than a democratic government can. The focus on masculinity and portrayals of Trump as a muscled hero‚ much as Russian president Vladimir Putin portrays himself, fit the mold of an authoritarian leader.

But the argument that Americans need a strongman depends on the argument that democracy does not work. In the last three-and-a-half years, Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, and the Democrats have proved that it can, so long as it operates with the best interests of ordinary people in mind. Trump and Vance’s outlandish lies about the federal response to Hurricane Helene are designed to override the reality of a competent administration addressing a crisis with all the tools it has. In its place, the lies provide a false narrative of federal officials ignoring people and trying to steal their property.

Their attack on democracy has another problem, as well. In addition to the reality that democracy has been delivering for Americans for more than three years now—and pretty dramatically—Trump is no longer a strongman. Vice President Kamala Harris is outperforming him in the theater of political dominance. And as she does so, his image is crumbling.

In an article in US News and World Report yesterday, NBC’s former chief marketer John D. Miller apologized to America for helping to “create a monster.” Miller led the team that marketed The Apprentice, the reality TV show that made Trump a household name. “To sell the show,” Miller wrote, “we created the narrative that Trump was a super-successful businessman who lived like royalty.” But the truth was that he declared bankruptcy six times, and “[t]he imposing board room where he famously fired contestants was a set, because his real boardroom was too old and shabby for TV,” Miller wrote. While Trump loved the attention the show provided, “more successful CEOs were too busy to get involved in reality TV.”

Miller says they “promoted the show relentlessly,” blanketing the country with a “highly exaggerated” image of Trump as a successful businessman “like a heavy snowstorm.” “[W]e…did irreparable harm by creating the false image of Trump as a successful leader,” Miller wrote. “I deeply regret that. And I regret that it has taken me so long to go public.”

Speaking as a “born-and-bred Republican,” Miller warned: “If you believe that Trump will be better for you or better for the country, that is an illusion, much like The Apprentice was.” He strongly urged people to vote for Kamala Harris. “The country will be better off and so will you.”

A new video shown last night on Jimmy Kimmel Live even more powerfully illustrated the collapse of Trump’s tough guy image. Written by Jesse Joyce of Comedy Central, the two-minute video featured actor and retired professional wrestler Dave Bautista dominating his sparring partner in a boxing ring and then telling those who think Trump is “some sort of tough guy” that “he’s not.”

Working out in a gym, Bautista insults Trump’s heavy makeup, out-of-shape body, draft dodging, and physical weakness, and notes that “he sells imaginary baseball cards pretending to be a cowboy fireman” when “he’s barely strong enough to hold an umbrella.” Bautista says Trump’s two-handed method of drinking water looks “like a little pink chickadee,” and goes on to make a raunchy observation about Trump’s stage dancing. “He’s moody, he pouts, he throws tantrums,” Bautista goes on. “He’s cattier on social media than a middle-school mean girl.”

Bautista ends by listing Trump’s fears of rain, dogs, windmills…and being laughed at.” “And mostly,” Bautista concludes, “he’s terrified that real, red-blooded American men will find out that he’s a weak, tubby toddler.” Calling Trump a “whiny b*tch,” Bautista walks away from the camera.

The sketch was billed as comedy, but it was deadly serious in its takedown of the key element of Trump’s political power.

And he seems vulnerable. Forbes and Newsweek have recently questioned his mental health; yesterday the Boston Globe ran an op-ed saying, “Trump’s decline is too dangerous to ignore. We can see the decline in the former president’s ability to hold a train of thought, speak coherently, or demonstrate a command of the English language, to say nothing of policy.”

Trump’s Fox News Channel town hall yesterday got 2.9 million viewers; Harris’s interview got 7.1 million. Today, Trump canceled yet another appearance, this one with the National Rifle Association in Savannah, Georgia, scheduled for October 22, where he was supposed to be the keynote speaker.

Meanwhile, Vice President Harris today held rallies in Milwaukee, Green Bay, and La Crosse, Wisconsin. In La Crosse, MAGA hecklers tried to interrupt her while she was speaking about the centrality of the three Trump-appointed Supreme Court justices to the overturning of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that recognized the constitutional right to abortion.

“Oh, you guys are at the wrong rally,” Harris called to them with a smile and a wave. As the crowd roared with approval, she added: “No, I think you meant to go to the smaller one down the street.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#political cartoons#Guy Parsons#cleanup#disinformation#jimmy kimmel live#media#the US Economy#MAGA hecklers#FOX News#Trump's decline#Dave Bautista#The Apprentice#US Council on Foreign Relations

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

any way in a modern linked universe wind is in like a remote/home school co-op because he lives on an island with canonically a total four (4) school aged kids and no physical school so he does online classes with people from different islands, which is how he originally meets like medli and makar. tetra’s boat got that satellite internet so he sits in his 9th grade english zoom call and discusses great expectations with some teacher who lives on windfall and then the second he leaves the call he and tetra have an hour to commit pirate crimes until he has to be back on for geometry.

(the pirate crimes wind and tetra commit are not the act of exploring uninhabited islands, actually - i'm imagining tetra's boat to be like a offshore ketch (since its carrying a crew most of the time and because i want the a e s t h e t i c that comes from having multiple sails, but i also want link and tetra to ditch the rest of their crew and go off on their own) so they can probably sail at 6-8 knots (7-9 mph) which makes leaving territorial waters* (12 nautical miles (~14 regular miles)) a viable day trip adventure for them. the government of hyrule defines piracy as (conveniently for me) "acts that endanger the safe navigation of ships" **(and ive decided sailing without a boating license is included in this list along with, ya know, the usual things like seizing control of a ship or plundering distressed vessels (has tetra's crew ever seized control of a ship or plundered a distressed vessel? who knows, certainly not a court of law)) gonzo has a valid boating license and tends to be at the helm since it causes the least problems if they get questioned at port. tetra, however, (as an unfortunate side effect of being born in secret to escape unspecified hyrule royal family political turmoil(context pending)) does not legally exist in the eyes of the law, and therefore has not only no boating license, but also no legal identification at all. therefore, the act of sailing on the open seas without a license counts as a "endangering the safe navigation of ships" in international waters ∴ piracy)

four is home schooled because he refuses to learn anything that he isnt intensely interested in, so grandpa smith threw in the towel years ago and just counts his 16 hour long deep dive on 18th century occult practices as a history assignment. he'd love to push for some grammar lessons today but four has already disappeared into the garage to use a disassembled microwave to do fractal wood burning*** on the handle of a bowie knife he made out of a broken crescent wrench.

*contiguous zones? economic exclusion zones? never heard of them, its my half thought out modern au, the bureaucracy only exists in ways that are convenient for me

** us law defines acts of piracy that endanger the safe navigation of ships as: seizing or exercising control of a ship by force or threat of force, performing an act of violence against a person onboard a ship, destroying a ship or its cargo, placing or causing to be placed on a ship a device that could destroy or damage the ship and its cargo, destroying or damaging maritime navigational facilities or interfering with their operation, communicating navigational information that is known to be false but likely to be believed, plundering distressed vessels, corruption of seamen, depredation at sea, privateering, injuring or killing a person while committing any of those acts listed, and attempting or conspiring to commit those acts listed. i choose to believe that tetra has committed a third or more of this list

*** there have been 34 reported deaths from fractal wood burning, do not attempt.

#legend of zelda#modern au#linked universe#linked modernverse#linked modern!verse#lu wind#lu four#wind waker link#four swords link#content warning: possibly inaccurate boat information

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

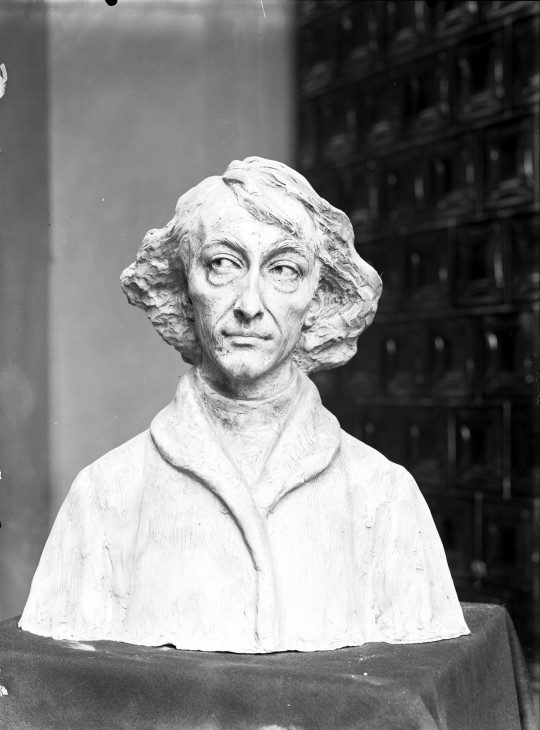

Nicolaus Copernicus (Konstanty Laszczka, Polish sculptor)

Happy birthday, Nicolaus Copernicus!

Nicolaus Copernicus (February 19, 1473 — May 24, 1543) is primarily known as an exceptional astronomer who formulated the true model of the solar system, which led to an unprecedented change in the human perception of Earth’s place in the universe. This great Pole, who is rightly included among the greatest minds of the European Renaissance, was also a clergyman, a mathematician, a physician, a lawyer and a translator. He also proved himself as an effective strategist and military commander, leading the defence of Olsztyn against the attack of the German Monastic Order of the Teutonic Knights. Later on, he exhibited great organizational skills, quickly rebuilding and relaunching the economy of the areas devastated by the invasion of the Teutonic Knights. He also served in diplomacy and participated in the works of the Polish Sejm.

Copernicus’ scientific achievements in the field of economics were equally significant, and place him among the greatest authors of the world economic thought. In 1517 Copernicus wrote a treatise on the phenomenon of bad money driving out good money. He noted that the“debasement of coin” was one of the main reasons for the collapse of states. He was therefore one of the first advocates of modern monetary policy based on the unification of the currency in circulation, constant care for its value and the prevention of inflation, which ruins the economy. In money he distinguished the ore value (valor) and the estimated value (estimatio), determined by the issuer. According to Copernicus, the ore value of a good coin should correspond to its estimated value. This was not synonymous, however, with the reduction of the coin to a piece of metal being the subject of trade in goods. The ore contained in the money was supposed to be the guarantee of its price, and the value of the legal tender was assigned to it by special symbols proving its relationship with a given country and ruler. Although such views are nothing new today, in his time they constituted a milestone in the development of economic thought.

Additionally Copernicus was not only a theorist of finance, but he was also the co-author of a successful monetary reform, later also implemented in other countries. It was Copernicus, the first of the great Polish economists, who in 1519 proposed to King Sigismund I the Old to unify the monetary system of the Polish Crown with that of its subordinate Royal Prussia. The principles described in the treatise published in 1517 were decades later repeated by the English financier Thomas Gresham and are currently most often referred to around the world as Gresham’s law. Historical truth, however, requires us to restore the authorship of this principle to its creator, for example through the popularization of knowledge about the Copernicus-Gresham Law. (© NBP - We protect the value of money).

#nicolaus copernicus#mikołaj kopernik#sculpture#poland#science#konstanty laszczka#scienceblr#scientists#science academia#astronomy#thomas gresham#science history#renaissance#16th century#polish artist#study inspiration#solar system#planets#prussia#kingdom of poland#*

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

On August 1st 1967 Queen's College in Dundee became a fully fledged university in its own right and was renamed the University of Dundee.

The history of what would become Dundee University stretches back to 1881 when University College Dundee was founded. Its creation owed much to the wealth gathered in Dundee through the jute and textile industry. The prospect of establishing a university in Dundee had been under discussion since the 1860s. It was made a reality with a donation of £120,000 from Miss Mary Ann Baxter, of the hugely wealthy and influential Baxter family. Her cousin, John Boyd Baxter, the Procurator Fiscal for Dundee District of Forfarshire, was heavily involved in the discussions and also donated monies. As the main benefactor and co-founder, Miss Baxter had definite ideas about how she would like the college to run and took an active role in ensuring her wishes were fulfilled. The deed establishing University College stated that it should promote “the education of persons of both sexes and the study of Science, Literature and the Fine Arts”. As well as promoting the education of both sexes, Miss Baxter insisted it should not teach Divinity, and was adamant that those associated with the university did not have to reveal their religious leanings. Baxter’s role in establishing University College, Dundee was noted at the time by Scotland’s most notorious poet, who has always had an association with the city, William Topaz McGonagall who wrote: Good people of Dundee, your voices raise And to Miss Baxter give great praise; Rejoice and sing and dance with glee Because she has founded a College in Bonnie Dundee University College, Dundee became part of St Andrews University in 1897, under the provisions of the Universities Scotland Act of 1889. This union served to “give expression to local feeling that there should be a vital connection between the old and the new in academic affairs.” Initially, the two worked alongside each other in relative harmony. Dundee students were able to graduate in science from St Andrews, despite never having attended any classes in the smaller town. However, over time relations became strained, particularly over the issue of the Medical School and whether chairs of anatomy and physiology should be established in Dundee, St Andrews or both, setting the stage for the tensions that would place some strain on the relationship between the two institutions in the decades ahead. By the mid-1900s separation was being proposed. A 1954 Royal Commission led to University College being given more independence, being renamed Queen’s College, and taking over the Dundee School of Economics. In 1963, the Committee on Higher Education under the chairmanship of Lord Robbins recommended in its report to Parliament that ‘at least one, and perhaps two, of its proposed new university foundations should be in Scotland’. The government approved the creation of a university in Dundee, and in 1966, the University Court and the Council of Queen’s College submitted a joint petition to the Privy Council seeking the grant of a Royal Charter to establish Dundee University. This petition was approved and, in terms of the Charter, Queen’s College became Dundee University on this day in 1967. To mark the event and the University’s independence the people of Dundee witnessed an unusual event as hundreds of students filed up the Law dressed in red academic gowns. At the top they admired the stunning views – “an arresting vision in crimson” – before heading back down to the newly designated Dundee University. Fifty years on, and Dundee and St Andrews universities enjoy a warm relationship, very much in the spirit of friendly rivalry. Both are in the world’s top 200 universities and are among the top ranked in the UK for student experience. The combined strengths of Dundee and St Andrews have been recognised as an “intellectual gold coast” on Scotland’s east side. Other highlights in Dundee University’s history include the formal merger of Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art with the university in 1994 and the Tayside College of Nursing and Fife College of Health Studies becoming part of the university from September 1, 1996.

And in December 2001 the university merged with the Dundee campus of Northern College to create the Faculty of Education and Social Work.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter II. Of Value.

3. — Application of the law of proportionality of values.

Every product is a representative of labor.

Every product, therefore, can be exchanged for some other, as universal practice proves.

But abolish labor, and you have left only articles of greater or less usefulness, which, being stamped with no economic character, no human seal, are without a common measure, — that is, are logically unexchangeable.

Gold and silver, like other articles of merchandise, are representatives of value; they have, therefore, been able to serve as common measures and mediums of exchange. But the special function which custom has allotted to the precious metals, — that of serving as a commercial agent, — is purely conventional, and any other article of merchandise, less conveniently perhaps, but just as authentically, could play this part: the economists admit it, and more than one example of it can be cited. What, then, is the reason of this preference generally accorded to the metals for the purpose of money, and how shall we explain this speciality of function, unparalleled in political economy, possessed by specie? For every unique thing incomparable in kind is necessarily very difficult of comprehension, and often even fails of it altogether. Now, is it possible to reconstruct the series from which money seems to have been detached, and, consequently, restore the latter to its true principle?

In dealing with this question the economists, following their usual course, have rushed beyond the limits of their science; they have appealed to physics, to mechanics, to history, etc.; they have talked of all things, but have given no answer. The precious metals, they have said, by their scarcity, density, and incorruptibility, are fitted to serve as money in, a degree unapproached by other kinds of merchandise. In short, the economists, instead of replying to the economic question put to them, have set themselves to the examination of a question of art. They have laid great stress on the mechanical adaptation of gold and silver for the purpose of money; but not one of them has seen or understood the economic reason which gave to the precious metals the privilege they now enjoy.

Now, the point that no one has noticed is that, of all the various articles of merchandise, gold and silver were the first whose value was determined. In the patriarchal period, gold and silver still were bought and sold in ingots, but already with a visible tendency to superiority and with a marked preference. Gradually sovereigns took possession of them and stamped them with their seal; and from this royal consecration was born money, — that is, the commodity par excellence; that which, notwithstanding all commercial shocks, maintains a determined proportional value, and is accepted in payment for all things.

That which distinguishes specie, in fact, is not the durability of the metal, which is less than that of steel, nor its utility, which is much below that of wheat, iron, coal, and numerous other substances, regarded as almost vile when compared with gold; neither is it its scarcity or density, for in both these respects it might be replaced, either by labor spent upon other materials, or, as at present, by bank notes representing vast amounts of iron or copper. The distinctive feature of gold and silver, I repeat, is the fact that, owing to their metallic properties, the difficulties of their production, and, above all, the intervention of public authority, their value as merchandise was fixed and authenticated at an early date.

I say then that the value of gold and silver, especially of the part that is made into money, although perhaps it has not yet been calculated accurately, is no longer arbitrary; I add that it is no longer susceptible of depreciation, like other values, although it may vary continually nevertheless. All the logic and erudition that has been expended to prove, by the example of gold and silver, that value is essentially indeterminable, is a mass of paralogisms, arising from a false idea of the question, ab ignorantia elenchi.

Philip I, King of France, mixed with the livre tournois of Charlemagne one-third alloy, imagining that, since he held the monopoly of the power of coining money, he could do what every merchant does who holds the monopoly of a product. What was, in fact, this adulteration of money, for which Philip and his successors are so severely blamed? A very sound argument from the standpoint of commercial routine, but wholly false in the view of economic science, — namely, that, supply and demand being the regulators of value, we may, either by causing an artificial scarcity or by monopolizing the manufacture, raise the estimation, and consequently the value, of things, and that this is as true of gold and silver as of wheat, wine, oil, tobacco. Nevertheless, Philip’s fraud was no sooner suspected than his money was reduced to its true value, and he lost himself all that he had expected to gain from his subjects. The same thing happened after all similar attempts. What was the reason of this disappointment?

Because, say the economists, the quantity of gold and silver in reality being neither diminished nor increased by the false coinage, the proportion of these metals to other merchandise was not changed, and consequently it was not in the power of the sovereign to make that which was worth but two worth four. For the same reason, if, instead of debasing the coin, it had been in the king’s power to double its mass, the exchangeable value of gold and silver would have decreased one-half immediately, always on account of this proportionality and equilibrium. The adulteration of the coin was, then, on the part of the king, a forced loan, or rather, a bankruptcy, a swindle.

Marvelous! the economists explain very clearly, when they choose, the theory of the measure of value; that they may do so, it is necessary only to start them on the subject of money. Why, then, do they not see that money is the written law of commerce, the type of exchange, the first link in that long chain of creations all of which, as merchandise, must receive the sanction of society, and become, if not in fact, at least in right, acceptable as money in settlement of all kinds of transactions?

“Money,” M. Augier very truly says, “can serve, either as a means of authenticating contracts already made, or as a good medium of exchange, only so far as its value approaches the ideal of permanence; for in all cases it exchanges or buys only the value which it possesses.” [8]

Let us turn this eminently judicious observation into a general formula.

Labor becomes a guarantee of well-being and equality only so far as the product of each individual is in proportion with the mass; for in all cases it exchanges or buys a value equal only to its own.

Is it not strange that the defence of speculative and fraudulent commerce is undertaken boldly, while at the same time the attempt of a royal counterfeiter, who, after all, did but apply to gold and silver the fundamental principle of political economy, the arbitrary instability of values, is frowned down? If the administration should presume to give twelve ounces of tobacco for a pound, [9] the economists would cry robbery; but, if the same administration, using its privilege, should increase the price a few cents a pound, they would regard it as dear, but would discover no violation of principles. What an imbroglio is political economy!

There is, then, in the monetization of gold and silver something that the economists have given no account of; namely, the consecration of the law of proportionality, the first act in the constitution of values. Humanity does all things by infinitely small degrees: after comprehending the fact that all products of labor must be submitted to a proportional measure which makes all of them equally exchangeable, it begins by giving this attribute of absolute exchangeability to a special product, which shall become the type and model of all others. In the same way, to lift its members to liberty and equality, it begins by creating kings. The people have a confused idea of this providential progress when, in their dreams of fortune and in their legends, they speak continually of gold and royalty; and the philosophers only do homage to universal reason when, in their so-called moral homilies and their socialistic utopias, they thunder with equal violence against gold and tyranny. Auri sacra fames! Cursed gold! ludicrously shouts some communist. As well say cursed wheat, cursed vines, cursed sheep; for, like gold and silver, every commercial value must reach an exact and accurate determination. The work was begun long since; today it is making visible progress.

Let us pass to other considerations.

It is an axiom generally admitted by the economists that all labor should leave an excess.

I regard this proposition as universally and absolutely true; it is a corollary of the law of proportionality, which may be regarded as an epitome of the whole science of economy. But — I beg pardon of the economists -the principle that all labor should leave an excess has no meaning in their theory, and is not susceptible of demonstration. If supply and demand alone determine value, how can we tell what is an excess and what is a sufficiency? If neither cost, nor market price, nor wages can be mathematically determined, how is it possible to conceive of a surplus, a profit? Commercial routine has given us the idea of profit as well as the word; and, since we are equal politically, we infer that every citizen has an equal right to realize profits in his personal industry. But commercial operations are essentially irregular, and it has been proved beyond question that the profits of commerce are but an arbitrary discount forced from the consumer by the producer, — in short, a displacement, to say the least. This we should soon see, if it was possible to compare the total amount of annual losses with the amount of profits. In the thought of political economy, the principle that all labor should leave an excess is simply the consecration of the constitutional right which all of us gained by the revolution, — the right of robbing one’s neighbor.

The law of proportionality of values alone can solve this problem. I will approach the question a little farther back: its gravity warrants me in treating it with the consideration that it merits.

Most philosophers, like most philologists, see in society only a creature of the mind, or rather, an abstract name serving to designate a collection of men. It is a prepossession which all of us received in our infancy with our first lessons in grammar, that collective nouns, the names of genera and species, do not designate realities. There is much to say under this head, but I confine myself to my subject. To the true economist, society is a living being, endowed with an intelligence and an activity of its own, governed by special laws discoverable by observation alone, and whose existence is manifested, not under a material aspect, but by the close concert and mutual interdependence of all its members. Therefore, when a few pages back, adopting the allegorical method, we used a fabulous god as a symbol of society, our language in reality was not in the least metaphorical: we only gave a name to the social being, an organic and synthetic unit. In the eyes of any one who has reflected upon the laws of labor and exchange (I disregard every other consideration), the reality, I had almost said the personality, of the collective man is as certain as the reality and the personality of the individual man. The only difference is that the latter appears to the senses as an organism whose parts are in a state of material coherence, which is not true of society. But intelligence, spontaneity, development, life, all that constitutes in the highest degree the reality of being, is as essential to society as to man: and hence it is that the government of societies is a science, — that is, a study of natural relations, — and not an art, — that is, good pleasure and absolutism. Hence it is, finally, that every society declines the moment it falls into the hands of the ideologists.

The principle that all labor should leave an excess, undemonstrable by political economy, — that is, by proprietary routine, — is one of those which bear strongest testimony to the reality of the collective person: for, as we shall see, this principle is true of individuals only because it emanates from society, which thus confers upon them the benefit of its own laws.

Let us turn to facts. It has been observed that railroad enterprises are a source of wealth to those who control them in a much less degree than to the State. The observation is a true one; and it might have been added that it applies, not only to railroads, but to every industry. But this phenomenon, which is essentially the result of the law of proportionality of values and of the absolute identity of production and consumption, is at variance with the ordinary notion of useful value and exchangeable value.

The average price charged for the transportation of merchandise by the old method is eighteen centimes per ton and kilometer, the merchandise taken and delivered at the warehouses. It has been calculated that, at this price, an ordinary railroad corporation would net a profit of not quite ten per cent., nearly the same as the profit made by the old method. But let us admit that the rapidity of transportation by rail is to that by wheels, all allowances made, as four to one: in society time itself being value, at the same price the railroad would have an advantage over the stage-wagon of four hundred per cent. Nevertheless, this enormous advantage, a very real one so far as society is concerned, is by no means realized in a like proportion by the carrier, who, while he adds four hundred per cent. to the social value, makes personally less than ten per cent. Suppose, in fact, to make the thing still clearer, that the railroad should raise its price to twenty-five centimes, the rate by the old method remaining at eighteen; it would lose immediately all its consignments; shippers, consignees, everybody would return to the stage-wagon, if necessary. The locomotive would be abandoned; a social advantage of four hundred per cent. would be sacrificed to a private loss of thirty-three per cent.

The reason of this is easily seen. The advantage which results from the rapidity of the railroad is wholly social, and each individual participates in it only in a very slight degree (do not forget that we are speaking now only of the transportation of merchandise); while the loss falls directly and personally on the consumer. A special profit of four hundred per cent. in a society composed of say a million of men represents four ten-thousandths for each individual; while a loss to the consumer of thirty-three per cent means a social deficit of thirty-three millions. Private interest and collective interest, seemingly so divergent at first blush, are therefore perfectly identical and equal: and this example may serve to show already how economic science reconciles all interests.

Consequently, in order that society may realize the profit above supposed, it is absolutely necessary that the railroad’s prices shall not exceed, or shall exceed but very little, those of the stage-wagon.

But, that this condition may be fulfilled, — in other words, that the railroad may be commercially possible, — the amount of matter transported must be sufficiently great to cover at least the interest on the capital invested and the running expenses of the road. Then a railroad’s first condition of existence is a large circulation, which implies a still larger production and a vast amount of exchanges.

But production, circulation, and exchange are not self-creative things; again, the various kinds of labor are not developed in isolation and independently of each other: their progress is necessarily connected, solidary, proportional. There may be antagonism among manufacturers; but, in spite of them, social action is one, convergent, harmonious, — in a word, personal. Further, there is a day appointed for the creation of great instruments of labor: it is the day when general consumption shall be able to maintain their employment, — that is, for all these propositions are interconvertible, the day when ambient labor can feed new machinery. To anticipate the hour appointed by the progress of labor would be to imitate the fool who, going from Lyons to Marseilles, chartered a steamer for himself alone.

These points cleared up, nothing is easier than to explain why labor must leave an excess for each producer.

And first, as regards society: Prometheus, emerging from the womb of Nature, awakens to life in a state of inertia which is very charming, but which would soon become misery and torture if he did not make haste to abandon it for labor. In this original idleness, the product of Prometheus being nothing, his well-being is the same as that of the brute, and may be represented by zero.

Prometheus begins to work: and from his first day’s labor, the first of the second creation, the product of Prometheus — that is, his wealth, his well-being — is equal to ten.

The second day Prometheus divides his labor, and his product increases to one hundred.

The third day, and each following day, Prometheus invents machinery, discovers new uses in things, new forces in Nature; the field of his existence extends from the domain of the senses to the sphere of morals and intelligence, and with every step that his industry takes the amount of his product increases, and assures him additional happiness. And since, finally, with him, to consume is to produce, it is clear that each day’s consumption, using up only the product of the day before, leaves a surplus product for the day after.

But notice also — and give especial heed to this all-important fact — that the well-being of man is directly proportional to the intensity of labor and the multiplicity of industries: so that the increase of wealth and the increase of labor are correlative and parallel.

To say now that every individual participates in these general conditions of collective development would be to affirm a truth which, by reason of the evidence in its support, would appear silly. Let us point out rather the two general forms of consumption in society.

Society, like the individual, has first its articles of personal consumption, articles which time gradually causes it to feel the need of, and which its mysterious instincts command it to create. Thus in the middle ages there was, with a large number of cities, a decisive moment when the building of city halls and cathedrals became a violent passion, which had to be satisfied at any price; the life of the community depended upon it. Security and strength, public order, centralization, nationality, country, independence, these are the elements which make up the life of society, the totality of its mental faculties; these are the sentiments which must find expression and representation. Such formerly was the object of the temple of Jerusalem, real palladium of the Jewish nation; such was the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus of Rome. Later, after the municipal palace and the temple, — organs, so to speak, of centralization and progress, — came the other works of public utility, — bridges, theatres, schools, hospitals, roads, etc.

The monuments of public utility being used essentially in common, and consequently gratuitously, society is rewarded for its advances by the political and moral advantages resulting from these great works, and which, furnishing security to labor and an ideal to the mind, give fresh impetus to industry and the arts.

But it is different with the articles of domestic consumption, which alone fall within the category of exchange. These can be produced only upon the conditions of mutuality which make consumption possible, — that is, immediate payment with advantage to the producers. These conditions we have developed sufficiently in the theory of proportionality of values, which we might call as well the theory of the gradual reduction of cost.

I have demonstrated theoretically and by facts the principle that all labor should leave an excess; but this principle, as certain as any proposition in arithmetic, is very far from universal realization. While, by the progress of collective industry, each individual day’s labor yields a greater and greater product, and while, by necessary consequence, the laborer, receiving the same wages, must grow ever richer, there exist in society classes which thrive and classes which perish; laborers paid twice, thrice, a hundred times over, and laborers continually out of pocket; everywhere, finally, people who enjoy and people who suffer, and, by a monstrous division of the means of industry, individuals who consume and do not produce. The distribution of well-being follows all the movements of value, and reproduces them in misery and luxury on a frightful scale and with terrible energy. But everywhere, too, the progress of wealth — that is, the proportionality of values — is the dominant law; and when the economists combat the complaints of the socialists with the progressive increase of public wealth and the alleviations of the condition of even the most unfortunate classes, they proclaim, without suspecting it, a truth which is the condemnation of their theories.

For I entreat the economists to question themselves for a moment in the silence of their hearts, far from the prejudices which disturb them, and regardless of the employments which occupy them or which they wait for, of the interests which they serve, of the votes which they covet, of the distinctions which tickle their vanity: let them tell me whether, hitherto, they have viewed the principle that all labor should leave an excess in connection with this series of premises and conclusions which we have elaborated, and whether they ever have understood these words to mean anything more than the right to speculate in values by manipulating supply and demand; whether it is not true that they affirm at once, on the one hand the progress of wealth and well-being, and consequently the measure of values, and on the other the arbitrariness of commercial transactions and the incommensurability of values, — the flattest of contradictions? Is it not because of this contradiction that we continually hear repeated in lectures, and read in the works on political economy, this absurd hypothesis: If the price of ALL things was doubled...... ? As if the price of all things was not the proportion of things, and as if we could double a proportion, a relation, a law! Finally, is it not because of the proprietary and abnormal routine upheld by political economy that every one, in commerce, industry, the arts, and the State, on the pretended ground of services rendered to society, tends continually to exaggerate his importance, and solicits rewards, subsidies, large pensions, exorbitant fees: as if the reward of every service was not determined necessarily by the sum of its expenses? Why do not the economists, if they believe, as they appear to, that the labor of each should leave an excess, use all their influence in spreading this truth, so simple and so luminous: Each man’s labor can buy only the value which it contains, and this value is proportional to the services of all other laborers?

But here a last consideration presents itself, which I will explain in a few words.

J. B. Say, who of all the economists has insisted the most strenuously upon the absolute indeterminability of value, is also the one who has taken the most pains to refute that idea. He, if I am not mistaken, is the author of the formula: Every product is worth what it costs; or, what amounts to the same thing: Products are bought with products. This aphorism, which leads straight to equality, has been controverted since by other economists; we will examine in turn the affirmative and the negative.

When I say that every product is worth the products which it has cost, I mean that every product is a collective unit which, in a new form, groups a certain number of other products consumed in various quantities. Whence it follows that the products of human industry are, in relation to each other, genera and species, and that they form a series from the simple to the composite, according to the number and proportion of the elements, all equivalent to each other, which constitute each product. It matters little, for the present, that this series, as well as the equivalence of its elements, is expressed in practice more or less exactly by the equilibrium of wages and fortunes; our first business is with the relation of things, the economic law. For here, as ever, the idea first and spontaneously generates the fact, which, recognized then by the thought which has given it birth, gradually rectifies itself and conforms to its principle. Commerce, free and competitive, is but a long operation of redressal, whose object is to define more and more clearly the proportionality of values, until the civil law shall recognize it as a guide in matters concerning the condition of persons. I say, then, that Say’s principle, Every product is worth what it costs, indicates a series in human production analogous to the animal and vegetable series, in which the elementary units (day’s works) are regarded as equal. So that political economy affirms at its birth, but by a contradiction, what neither Plato, nor Rousseau, nor any ancient or modern publicist has thought possible, -equality of conditions and fortunes.

Prometheus is by turns husbandman, wine-grower, baker, weaver. Whatever trade he works at, laboring only for himself, he buys what he consumes (his products) with one and the same money (his products), whose unit of measurement is necessarily his day’s work. It is true that labor itself is liable to vary; Prometheus is not always in the same condition, and from one moment to another his enthusiasm, his fruitfulness, rises and falls. But, like everything that is subject to variation, labor has its average, which justifies us in saying that, on the whole, day’s work pays for day’s work, neither more nor less. It is quite true that, if we compare the products of a certain period of social life with those of another, the hundred millionth day’s work of the human race will show a result incomparably superior to that of the first; but it must be remembered also that the life of the collective being can no more be divided than that of the individual; that, though the days may not resemble each other, they are indissolubly united, and that in the sum total of existence pain and pleasure are common to them. If, then, the tailor, for rendering the value of a day’s work, consumes ten times the product of the day’s work of the weaver, it is as if the weaver gave ten days of his life for one day of the tailor’s. This is exactly what happens when a peasant pays twelve francs to a lawyer for a document which it takes him an hour to prepare; and this inequality, this iniquity in exchanges, is the most potent cause of misery that the socialists have unveiled, — as the economists confess in secret while awaiting a sign from the master that shall permit them to acknowledge it openly.

Every error in commutative justice is an immolation of the laborer, a transfusion of the blood of one man into the body of another..... Let no one be frightened; I have no intention of fulminating against property an irritating philippic; especially as I think that, according to my principles, humanity is never mistaken; that, in establishing itself at first upon the right of property, it only laid down one of the principles of its future organization; and that, the pre-ponderance of property once destroyed, it remains only to reduce this famous antithesis to unity. All the objections that can be offered in favor of property I am as well acquainted with as any of my critics, whom I ask as a favor to show their hearts when logic fails them. How can wealth that is not measured by labor be valuable? And if it is labor that creates wealth and legitimates property, how explain the consumption of the idler? Where is the honesty in a system of distribution in which a product is worth, according to the person, now more, now less, than it costs.

Say’s ideas led to an agrarian law; therefore, the conservative party hastened to protest against them. “The original source of wealth,” M. Rossi had said, “is labor. In proclaiming this great principle, the industrial school has placed in evidence not only an economic principle, but that social fact which, in the hands of a skilful historian, becomes the surest guide in following the human race in its marchings and haltings upon the face of the earth.”

Why, after having uttered these profound words in his lectures, has M. Rossi thought it his duty to retract them afterwards in a review, and to compromise gratuitously his dignity as a philosopher and an economist?

“Say that wealth is the result of labor alone; affirm that labor is always the measure of value, the regulator of prices; yet, to escape one way or another the objections which these doctrines call forth on all hands, some incomplete, others absolute, you will be obliged to generalize the idea of labor, and to substitute for analysis an utterly erroneous synthesis.”

I regret that a man like M. Rossi should suggest to me so sad a thought; but, while reading the passage that I have just quoted, I could not help saying: Science and truth have lost their influence: the present object of worship is the shop, and, after the shop, the desperate constitutionalism which represents it. To whom, then, does M. Rossi address himself? Is he in favor of labor or something else; analysis or synthesis? Is he in favor of all these things at once? Let him choose, for the conclusion is inevitably against him.

If labor is the source of all wealth, if it is the surest guide in tracing the history of human institutions on the face of the earth, why should equality of distribution, equality as measured by labor, not be a law?

If, on the contrary, there is wealth which is not the product of labor, why is the possession of it a privilege? Where is the legitimacy of monopoly? Explain then, once for all, this theory of the right of unproductive consumption; this jurisprudence of caprice, this religion of idleness, the sacred prerogative of a caste of the elect.

What, now, is the significance of this appeal from analysis to the false judgments of the synthesis? These metaphysical terms are of no use, save to indoctrinate simpletons, who do not suspect that the same proposition can be construed, indifferently and at will, analytically or synthetically. Labor is the principle of value end the source of wealth: an analytic proposition such as M. Rossi likes, since it is the summary of an analysis in which it is demonstrated that the primitive notion of labor is identical with the subsequent notions of product, value, capital, wealth, etc. Nevertheless, we see that M. Rossi rejects the doctrine which results from this analysis. Labor, capital, and land are the sources of wealth: a synthetic proposition, precisely such as M. Rossi does not like. Indeed, wealth is considered here as a general notion, produced in three distinct, but not identical, ways. And yet the doctrine thus formulated is the one that M. Rossi prefers. Now, would it please M. Rossi to have us render his theory of monopoly analytically and ours of labor synthetically? I can give him the satisfaction..... But I should blush, with so earnest a man, to prolong such badinage. M. Rossi knows better than any one that analysis and synthesis of themselves prove absolutely nothing, and that the important work, as Bacon said, is to make exact comparisons and complete enumerations.

Since M. Rossi was in the humor for abstractions, why did he not say to the phalanx of economists who listen so respectfully to the least word that falls from his lips:

“Capital is the material of wealth, as gold and silver are the material of money, as wheat is the material of bread, and, tracing the series back to the end, as earth, water, fire, and air are the material of all our products. But it is labor, labor alone, which successively creates each utility given to these materials, and which consequently transforms them into capital and wealth. Capital is the result of labor, — that is, realized intelligence and life, — as animals and plants are realizations of the soul of the universe, and as the chefs d’oeuvre of Homer, Raphael, and Rossini are expressions of their ideas and sentiments. Value is the proportion in which all the realizations of the human soul must balance each other in order to produce a harmonious whole, which, being wealth, gives us well-being, or rather is the token, not the object, of our happiness.

“The proposition, there is no measure of value, is illogical and contradictory, as is shown by the very arguments which have been offered in its support.

“The proposition, labor is the principle of proportionality of values, not only is true, resulting as it does from an irrefutable analysis, but it is the object of progress, the condition and form of social well-being, the beginning and end of political economy. From this proposition and its corollaries, every product is worth what it costs, and products are bought with products, follows the dogma of equality of conditions.

“The idea of value socially constituted, or of proportionality of values, serves to explain further: (a) how a mechanical invention, notwithstanding the privilege which it temporarily creates and the disturbances which it occasions, always produces in the end a general amelioration; (b) how the value of an economical process to its discoverer can never equal the profit which it realizes for society; (c) how, by a series of oscillations between supply and demand, the value of every product constantly seeks a level with cost and with the needs of consumption, and consequently tends to establish itself in a fixed and positive manner; (d) how, collective production continually increasing the amount of consumable things, and the day’s work constantly obtaining higher and higher pay, labor must leave an excess for each producer; (e) how the amount of work to be done, instead of being diminished by industrial progress, ever increases in both quantity and quality — that is, in intensity and difficulty — in all branches of industry; (f) how social value continually eliminates fictitious values, — in other words, how industry effects the socialization of capital and property; (g) finally, how the distribution of products, growing in regularity with the strength of the mutual guarantee resulting from the constitution of value, pushes society onward to equality of conditions and fortunes.

“Finally, the theory of the successive constitution of all commercial values implying the infinite progress of labor, wealth, and well-being, the object of society, from the economic point of view, is revealed to us: To produce incessantly, with thee least possible amount of labor for each product, the greatest possible quantity and variety of values, in such a way as to realize, for each individual, the greatest amount of physical, moral, and intellectual well-being, and, for the race, the highest perfection and infinite glory.

Now that we have determined, not without difficulty, the meaning of the question asked by the Academy of Moral Sciences touching the oscillations of profit and wages, it is time to begin the essential part of our work. Wherever labor has not been socialized, — that is, wherever value is not synthetically determined, — there is irregularity and dishonesty in exchange; a war of stratagems and ambuscades; an impediment to production, circulation, and consumption; unproductive labor; insecurity; spoliation; insolidarity; want; luxury: but at the same time an effort of the genius of society to obtain justice, and a constant tendency toward association and order. Political economy is simply the history of this grand struggle. On the one hand, indeed, political economy, in so far as it sanctions and pretends to perpetuate the anomalies of value and the prerogatives of selfishness, is truly the theory of misfortune and the organization of misery; but in so far as it explains the means invented by civilization to abolish poverty, although these means always have been used exclusively in the interest of monopoly, political economy is the preamble of the organization of wealth.

It is important, then, that we should resume the study of economic facts and practices, discover their meaning, and formulate their philosophy. Until this is done, no knowledge of social progress can be acquired, no reform attempted. The error of socialism has consisted hitherto in perpetuating religious reverie by launching forward into a fantastic future instead of seizing the reality which is crushing it; as the wrong of the economists has been in regarding every accomplished fact as an injunction against any proposal of reform.

For my own part, such is not my conception of economic science, the true social science. Instead of offering a priori arguments as solutions of the formidable problems of the organization of labor and the distribution of wealth, I shall interrogate political economy as the depositary of the secret thoughts of humanity; I shall cause it to disclose the facts in the order of their occurrence, and shall relate their testimony without intermingling it with my own. It will be at once a triumphant and a lamentable history, in which the actors will be ideas, the episodes theories, and the dates formulas.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#the system of economic contradictions#the philosophy of poverty#volume i#pierre-joseph proudhon#pierre joseph proudhon

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alliance University Bangalore: A Premier Institution for Higher Learning

Alliance University, located in the vibrant city of Bangalore, is one of India's leading private universities. Established with a vision to provide world-class education and foster academic excellence, Alliance University Bangalore has quickly become a hub for students aspiring to pursue a career in various fields, including management, engineering, law, and more. The university is recognized for its commitment to high academic standards, global exposure, and a strong emphasis on research.

Why Choose Alliance University Bangalore?

1. Top-Notch Academic Programs

Alliance University offers a diverse range of undergraduate, postgraduate, and doctoral programs across its faculties of Management, Engineering, Law, and Liberal Arts. Some of the flagship courses include:

MBA at Alliance School of Business, which is among the top B-Schools in India.

B.Tech and M.Tech programs at the Alliance College of Engineering and Design.

BA LLB (Hons.) and LLM programs at Alliance School of Law, known for their strong legal curriculum.

2. Highly Qualified Faculty

One of the distinguishing factors of Alliance University Bangalore is its team of distinguished faculty members, who bring a wealth of academic and industry experience. Many of the professors are alumni of prestigious institutions such as IITs, IIMs, and top global universities, offering students the opportunity to learn from the best.

3. State-of-the-Art Campus

The campus of Alliance University in Bangalore is an architectural marvel that provides an ideal learning environment. Spanning over 55 acres, the campus is equipped with modern facilities including:

Smart classrooms with advanced learning aids.

Well-stocked libraries with vast collections of books, journals, and digital resources.

Laboratories with the latest equipment for engineering and science students.

Dedicated moot courts and simulation centers for law students.

In addition, the university has a vibrant campus life with clubs, events, and sports facilities that allow students to maintain a well-balanced lifestyle.

4. Global Collaborations

Alliance University Bangalore has established collaborations with over 45 reputed international universities across North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia. These partnerships enable students to participate in exchange programs, internships, and research projects with global exposure. Some partner institutions include:

Berlin School of Economics and Law, Germany.

Royal Roads University, Canada.

Nanjing University, China.

Through these collaborations, students can gain international exposure, preparing them to thrive in a globalized world.

5. Impressive Placement Record

Alliance University Bangalore takes pride in its excellent placement record. The Career Advancement and Networking (CAN) Cell works tirelessly to ensure students are well-prepared to enter the job market. The university has strong industry ties, attracting some of the best recruiters from India and abroad. Top companies like Amazon, Google, KPMG, Deloitte, and Infosys have recruited from Alliance University. The placement process includes:

Pre-placement talks.

Internship opportunities.

Grooming sessions to enhance soft skills.

With an average salary package on the rise and top-tier firms participating in the recruitment process, Alliance University is an attractive option for students seeking a promising career.

6. Bangalore: The Ideal Study Location

Bangalore, often referred to as the Silicon Valley of India, provides the perfect backdrop for higher education. The city's thriving economy, home to numerous startups, multinational corporations, and a vibrant tech industry, makes it a great place for internships and networking opportunities. Additionally, the pleasant climate, cosmopolitan culture, and diverse social scene make it an ideal location for students from across the globe.

Conclusion

Alliance University Bangalore is a prestigious institution that stands out for its academic excellence, global collaborations, and strong placement opportunities. Whether you're looking to pursue business, engineering, law, or liberal arts, Alliance University offers a world-class education that will equip you with the skills needed to succeed in today's competitive world.

#Alliance University Bangalore#education#higher education#news#universities#colleges#mba#students#Career Advancement and Networking (CAN)#B.Tech#Silicon Valley of India

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heather Cox Richardson 10.17.24

In a new rule released yesterday, the Federal Trade Commission requires sellers to make it as easy to cancel a subscription to a gym or a service as it is to sign up for one. In a statement, FTC chair Lina Khan explained the reasoning behind the “click-to-cancel” rule: “Too often, businesses make people jump through endless hoops just to cancel a subscription,” she said. “Nobody should be stuck paying for a service they no longer want.” Although most of the new requirements won’t take effect for about six months, David Dayen of The American Prospect noted that the stock price of Planet Fitness fell 8% after the announcement.

When he took office in January 2021, with democracy under siege from autocratic governments abroad and an authoritarian movement at home, President Joe Biden set out to prove that democracy could deliver for the ordinary people who had lost faith in it. The click-to-cancel rule is an illustration of an obvious and long-overdue protection, but it is only one of many ways—$35 insulin, new bridges, loan forgiveness, higher wages, good jobs—in which policies designed to benefit ordinary people have demonstrated that a democratic government can improve lives.

When Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen spoke to the Council on Foreign Relations yesterday, she noted that the administration “has driven a historic economic recovery” with strong growth, very low unemployment rates, and inflation returning to normal. Now it is focused on lowering costs for families and expanding the economy while reducing inequality. That strong economy at home is helping to power the global economy, Yellen noted, and the U.S. has been working to strengthen that economy by reinforcing global policies, investments, and institutions that reinforce economic stability.

“Over the past four years, the world has been through a lot,” Yellen said, “from a once-in-a-century pandemic, to the largest land war in Europe since World War II, to increasingly frequent and severe climate disasters. This has only underlined that we are all in it together. America’s economic well-being depends on the world’s, and America’s economic leadership is key to global prosperity and security.” She warned against isolationism that would undermine such prosperity both at home and abroad.

The numbers behind the proven experience that government protection of ordinary people is good for economic growth got the blessing of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences on Monday, when it awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, both of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and to James Robinson of the University of Chicago. Their research explains why “[s]ocieties with a poor rule of law and institutions that exploit the population do not generate growth or change for the better,” while democracies do.

Although democracy has been delivering for Americans, Donald Trump and MAGAs rose to power by convincing those left behind by 40 years of supply-side economics that their problem was not the people in charge of the government, but rather the government itself.

Trump wants to get rid of the current government so that he can enrich himself, do whatever he wants to his enemies, and avoid answering to the law. The Christian nationalists who wrote Project 2025 want to destroy the federal government so they can put in place an authoritarian who will force Americans to live under religious rule. Tech elites like Elon Musk and Peter Thiel want to get rid of the federal government so they can control the future without having to worry about regulations.

In place of what they insist is a democratic system that has failed, they are offering a strongman who, they claim, will take care of people more efficiently than a democratic government can. The focus on masculinity and portrayals of Trump as a muscled hero‚ much as Russian president Vladimir Putin portrays himself, fit the mold of an authoritarian leader.

(NOTE - WHAT a fucking JOKE!!)

But the argument that Americans need a strongman depends on the argument that democracy does not work. In the last three-and-a-half years, Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, and the Democrats have proved that it can, so long as it operates with the best interests of ordinary people in mind.

Trump and Vance’s outlandish lies about the federal response to Hurricane Helene are designed to override the reality of a competent administration addressing a crisis with all the tools it has. In its place, the lies provide a false narrative of federal officials ignoring people and trying to steal their property.

Their attack on democracy has another problem, as well. In addition to the reality that democracy has been delivering for Americans for more than three years now—and pretty dramatically—Trump is no longer a strongman. Vice President Kamala Harris is outperforming him in the theater of political dominance. And as she does so, his image is crumbling.

In an article in US News and World Report yesterday, NBC’s former chief marketer John D. Miller apologized to America for helping to “create a monster.” Miller led the team that marketed The Apprentice, the reality TV show that made Trump a household name. “To sell the show,” Miller wrote, “we created the narrative that Trump was a super-successful businessman who lived like royalty.” But the truth was that he declared bankruptcy six times, and “[t]he imposing board room where he famously fired contestants was a set, because his real boardroom was too old and shabby for TV,” Miller wrote. While Trump loved the attention the show provided, “more successful CEOs were too busy to get involved in reality TV.”

Miller says they “promoted the show relentlessly,” blanketing the country with a “highly exaggerated” image of Trump as a successful businessman “like a heavy snowstorm.” “[W]e…did irreparable harm by creating the false image of Trump as a successful leader,” Miller wrote. “I deeply regret that. And I regret that it has taken me so long to go public.”

Speaking as a “born-and-bred Republican,” Miller warned: “If you believe that Trump will be better for you or better for the country, that is an illusion, much like The Apprentice was.” He strongly urged people to vote for Kamala Harris. “The country will be better off and so will you.”

A new video shown last night on Jimmy Kimmel Live even more powerfully illustrated the collapse of Trump’s tough guy image. Written by Jesse Joyce of Comedy Central, the two-minute video featured actor and retired professional wrestler Dave Bautista dominating his sparring partner in a boxing ring and then telling those who think Trump is “some sort of tough guy” that “he’s not.”

Working out in a gym, Bautista insults Trump’s heavy makeup, out-of-shape body, draft dodging, and physical weakness, and notes that “he sells imaginary baseball cards pretending to be a cowboy fireman” when “he’s barely strong enough to hold an umbrella.” Bautista says Trump’s two-handed method of drinking water looks “like a little pink chickadee,” and goes on to make a raunchy observation about Trump’s stage dancing. “He’s moody, he pouts, he throws tantrums,” Bautista goes on. “He’s cattier on social media than a middle-school mean girl.”

Bautista ends by listing Trump’s fears of rain, dogs, windmills…and being laughed at.” “And mostly,” Bautista concludes, “he’s terrified that real, red-blooded American men will find out that he’s a weak, tubby toddler.” Calling Trump a “whiny b*tch,” Bautista walks away from the camera.

The sketch was billed as comedy, but it was deadly serious in its takedown of the key element of Trump’s political power.

And he seems vulnerable. Forbes and Newsweek have recently questioned his mental health; yesterday the Boston Globe ran an op-ed saying, “Trump’s decline is too dangerous to ignore. We can see the decline in the former president’s ability to hold a train of thought, speak coherently, or demonstrate a command of the English language, to say nothing of policy.”

Trump’s Fox News Channel town hall yesterday got 2.9 million viewers; Harris’s interview got 7.1 million. Today, Trump canceled yet another appearance, this one with the National Rifle Association in Savannah, Georgia, scheduled for October 22, where he was supposed to be the keynote speaker.

Meanwhile, Vice President Harris today held rallies in Milwaukee, Green Bay, and La Crosse, Wisconsin. In La Crosse, MAGA hecklers tried to interrupt her while she was speaking about the centrality of the three Trump-appointed Supreme Court justices to the overturning of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that recognized the constitutional right to abortion.

“Oh, you guys are at the wrong rally,” Harris called to them with a smile and a wave. As the crowd roared with approval, she added: “No, I think you meant to go to the smaller one down the street.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

By the standards of the hapless Greek monarchy, Constantine II, the last king of the Hellenes, who has died aged 82, led a comfortable life in exile after a brief and turbulent reign. Of the seven Greek monarchs of the 19th and 20th centuries, three were deposed, one assassinated, two abdicated and one died of septicaemia after being bitten by a barbary ape in the royal gardens.

The Glücksburg monarchy was German-Danish in origin, imposed on Greece in the 1830s. During prolonged wrangling after Constantine’s deposition, the Greek government refused to give him a passport until he acknowledged that he was Mr Glücksburg, whereas he insisted he was just plain Constantine. As the last of Greece’s deposed monarchs he escaped lightly. But decades of exile in London, as one thing the Greeks did not want back from Britain, were not how he would have chosen to spend his life.