#Romek Marber

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

La science-fiction, une littérature peu sérieuse

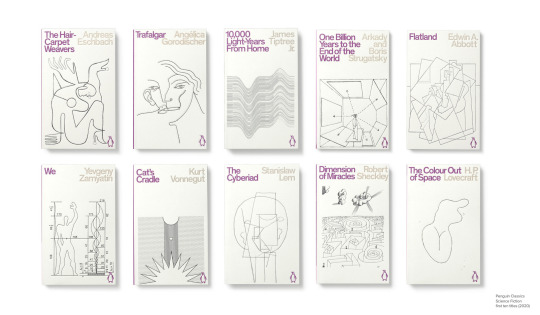

La maison Penguin Books s’inscrit dans l’histoire de l’édition britannique, une histoire incontournable pour tous les curieux du livre de poche. Cet article n’est pas le lieu où je cherche à cultiver les mots d’auteurs, déjà très nombreux. La reconnaissance suffisamment déployée de la maison d’édition londonienne est pourtant une des raisons spécifiques qui lui permet de tendre vers un design éditorial plus varié sans que cela mette en péril sa réputation. C’est bel et bien l’identité graphique forte de la maison d’édition qui permet au directeur artistique de la collection Penguin Classics Sci-Fi d’exploiter cette liberté. L’approche éditoriale de Jim Stoddart se détache de l’esthétique traditionnelle des éditions Penguin à travers vingt et un titres de Science-fiction et non sans raison ; réajuster un genre littéraire tenu par des idées préconçues, voilà le tour de main dont il fait preuve.

I. Quelle lecture faites-vous du registre iconographique sélectionné pour cette collection ? En quoi vous semble-t-il pertinent dans un tel contexte ?

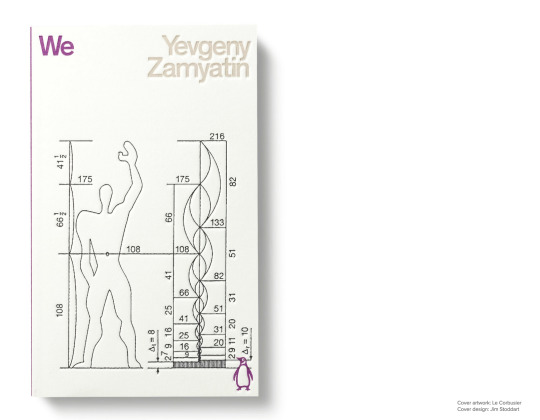

Le design de la collection Penguin Classics Sci-Fi opte pour mettre l’iconographie au premier plan. Déjà vu, me direz-vous. Il est vrai que la maison d’édition a déjà fait usage d’une intention similaire, notamment avec sa collection Penguin Great Loves. Le directeur artistique Jim Stoddart s’empare d’une stratégie éditoriale ayant déjà fait ses preuves auparavant. Pour chacun des titres, l’iconographie occupe ¾ de l’espace de la couverture, comme l’avait initié le graphiste britannique Romek Marber. Mais son intention va encore plus loin. En faisant usage du trait, il propose un répertoire d’œuvres des maîtres de l’art qui mettent à mal l’esthétique de la science-fiction traditionnelle. Ce registre iconographique est sélectionné non pas sans lien avec le contenu du livre de science-fiction, bien qu’il ne soit pas évident du premier coup d’œil. En effet, chaque œuvre d’art moderne explore des réalités fictives par leur interprétation du monde réel en lien étroit avec la littérature de science-fiction.

Quoi qu’on en dise, les couvertures de livres de science-fiction ont tendance à être associées à une esthétique bien plus exubérante et colorée. Penguin Classics Sci-Fi est bien plus sobre et mesurée. C’est d’ailleurs ce choix graphique qui permet aux ouvrages d’être individuellement associés à la même collection. En revanche, on reconnaît légèrement l’esthétique du livre de science-fiction par ce traitement du trait. Les couvertures nous évoquent des schémas qui font échos aux mathématiques et aux sciences. Puisque la représentation de l’espace-temps est indéniablement liée au genre littéraire de la science-fiction, Jim stoddart s’empare de cette mécanique. Par la sélection iconographique qu’il nous livre, il nous offre aussi un voyage entre différentes temporalités : des classiques littéraires plus récents aux œuvres de l’histoire de l’art datées. Alors ce ne sont effectivement pas des images futuristes peu digestes qui nous sont habituelles, mais ces iconographies font bien échos au livre de science-fiction.

II. Comment interprétez-vous le choix typographique opéré ici, et la façon dont le caractère est employé dans les couvertures ? Quelle tendance historique du design graphique de telles stratégies semblent-elles convoquer ?

Le choix du caractère typographique Theinhardt, dessiné par François Rappo parle d’une intention, celle de réinvestir les codes de l’école du Bauhaus et des praticiens de l’école de Zürich. Les tentatives de composition, avec une présence majeure de l’iconographie, trouvent leur origine en Suisse. À la recherche d’une neutralité pourtant utopique, Jim stoddart s’empare alors des expérimentations de ces prédécesseurs. Il opte pour un caractère typographique sans serif qu’il emploi en une seule graisse et avec le même corps de texte. Attendiez-vous à des lettres complètement fantaisistes ? Ce n’est pas le cas. Loin des caractères fantasques traditionnellement présents sur le design des couvertures de sciences-fictions, le Theinhardt ne présente pas de relation directe avec le thème de la collection.

Publié par la fonderie Optimo en 2009, le caractère combine fonctionnalité et clarté de sorte à répondre aux besoins contemporains qu’exige le design de collection. Dès le départ, l’idée est de rendre le caractère lisible et discret. L’utilisation de la couleur est un autre moyen de produire un effet d’unification de ces titres. Auparavant, Penguin Books s’est servi de cet outil pour identifier certaines collections, comme avec l’application du orange pour la collection Fiction. Cette fois-ci, le directeur artistique fait usage du violet pour les titres qui sont justifiés à gauche, le logotype ainsi que le dos de l’ouvrage. Cet élément monochrome agit comme un signe qui permet au lecteur de faire correspondre le roman à la collection Penguin Classics Sci-Fi. Les noms d’auteurs sont imprimés dans un gris chaud et justifiés à droite pour parvenir au lecteur plus tardivement. Visiblement, ces livres de poche convoquent la tendance suisse pour laquelle l’image est un matériau à privilégier et le caractère le moyen de transmettre l’information.

III. Quel semble avoir été le but poursuivi par le directeur artistique en ce qui concerne la perception traditionnelle du genre littéraire concerné par cette collection?

Bien que la maison Penguin Books soit indéniablement associée à des œuvres littéraires de grande qualité et d'une valeur culturelle certaine, la science-fiction reste un genre dévalué. Jim Stoddart cherche à célébrer les classiques de ce genre littéraire en lui attribuant une nouvelle image. En tout état de cause, la science-fiction grand public est associée à une imagerie extravagante qui la rend peu sérieuse. De ce fait, le directeur artistique a conçu la collection avec l’intention de changer la perception traditionnelle de la science-fiction comme un genre littéraire de divertissement. L’iconographie est donc le moyen de rendre la science-fiction légitime, en l’associant à l’histoire de l’art. Ces dessins au traits laissent beaucoup plus d’espace au blanc et à l’imagination de ses lecteurs. Ces livres de poche remettent en question les idées préconçues liées à la perception traditionnelle de ce genre littéraire tout en honorant les grands classiques du genre. Un tour de main réussi. Non seulement Jim Stoddart est parvenu à la conception d’une unité graphique de collection, mais aussi, il offre un regard nouveau sur ce genre littéraire en rendant justice à l’écriture de science-fiction.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Romek Marber (1965) •

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Romek Marber 1969

Follow Rhade-Zapan for more visual treats

757 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Design: Romek Marber

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Romek Marber obituary

Graphic designer who caught the mood of the 1960s with work for the Economist, Penguin and the Observer colour supplement

When the Economist magazine hired Romek Marber in 1961 to produce a series of front covers, the UK was introduced to a new design talent, one of those who would shake up the restrained visual landscape of postwar Britain. The Economist’s large circulation ensured that Marber’s designs reached a wide audience, catching the mood of the time and providing a fresh perspective on its major political and social events, not least with some classic covers on the tense relations between John F Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev during the period around the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

As an emigre designer from Poland, Marber, who has died aged 94, presented a version of European Modernism that was distinct both from the traditions of English Arts and Crafts and from the more robust approaches taken by American designers to styling consumer goods. He came into graphic design in Britain when it was a fledgling profession being carved out by a small band of pioneers, and he was one of that band’s most influential figures.

Marber’s work at the Economist brought him to the attention of Germano Facetti, the art director at Penguin books, and in 1961 he was employed by Facetti to revitalise the cover designs of the Penguin Crime series. Marber’s revamp was based around three distinct characteristics: continuity with Penguin’s visual history, an underlying grid that brought consistency and clarity, and challenging images that were mostly dark and enigmatic.

That mix of historical continuity, visual clarity and graphic mystery made Marber’s designs an immediate public success, with retailers hustling to return their old stock in exchange for the new, better selling covers. Within the design fraternity the “Marber Grid” that he showcased with Penguin came to be considered a classic of its kind: sustaining a consistent series identity, it also allowed for the use of strong graphic images on each cover.

With the acclaim that came his way, Marber received new commissions that included design work for Nicholson’s Guides, of which the London Street Finder map books were the most successful in the series. In 1964 he was also given the role of founding art director of the Observer newspaper’s colour supplement, with which he established a vibrant new format that pulsed with images of contemporary life.

Marber was born into a Jewish family in Turek in Poland, one of the three children of Moshe Marber, a manager in a textile factory, and his wife, Bronka (nee Szajniak), who worked for children’s charities. In 1939 the family tried to escape the German invasion of Poland by fleeing to Warsaw, where they were cut off by a siege of the city. Marber’s father, who was on the Gestapo wanted list, escaped with Marber’s elder brother, Kuba, believing that women and children would be safe back in Poland. Not long afterwards Romek and his twin sister, Roma, were transported, along with his mother and grandparents, to the Bochnia ghetto to the east of Krakow.

One day, when marched out on forced labour, Marber returned to discover the rest of his family had been transported to the Belzec concentration camp, where they were murdered. Now alone, he managed to acquire, in 1943, a forged identity card and an escape route into Hungary. But his guide turned out to be a Nazi collaborator, who handed him over to the Gestapo, and under SS guard he was marched through the streets of Kraków to Plaszów concentration camp, then on to Auschwitz and finally to the Flossenburg and Plattling camp, where he was liberated by US soldiers in April 1945.

After the war Marber went over the Alps into Italy with the dream of settling in Palestine. But on hearing that his father and brother were alive and in the UK, he changed his plans, arriving in London in August 1946 to be reunited with them.

In 1949 the Committee for the Education of Poles in Great Britain awarded Marber a grant to study commercial art at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London, where he enrolled in 1950 and met his future wife, Sheila Perry. He then gained a place to study graphic design at the Royal College of Art, where his external examiner, the designer Ashley Havinden, later offered him a well-paid post at the Crawford Advertising Agency, which Marber turned down.

Instead, in 1956, he took up as an assistant to the typographer Herbert Spencer and then two years later set up his own practice in Harley Street in London, which led to his work on the Economist, Penguin and the Observer.

In 1965 he also began to get work drawing up animated film titles, one of which included the design for a trailer for Peter Watkins’ 1966 docudrama about nuclear war, The War Game, which was commissioned by the BBC but banned from broadcast on any of its channels until 1985.

In 1967 Marber became consultant head of graphic design at Hornsey College of Art in north London while continuing his design studio work. The college was one of Britain’s most vibrant pipelines for creative talent, and within a year of joining he had become involved in supporting a well-publicised sit-in of students who were protesting about the way that art was being taught. He remained at Hornsey (which was incorporated into Middlesex University in 1973) until 1988, when he retired to care for his Sheila, who died the following year.

Later in retirement, Marber wrote an account of his childhood experiences during the Holocaust for the benefit of family alone. He sent a copy to his friend, the designer Richard Hollis, and Hollis immediately resolved to get the story into print for a wider audience. With Marber’s support, Hollis published the book in 2010 under the title No Return: Journeys in the Holocaust.

Marber wrote in the book that he found the thought of visiting his homeland “disturbing”, and that “however much I long to see Poland, I couldn’t go back”. Nonetheless, in 2015, when the first exhibition in Poland of Marber’s graphic designs opened at the Galicia Jewish Museum in Kraków, he found enough resolve to attend the private view in person, travelling there with his partner of many years, the designer Orna Frommer Dawson. This was the first time he had set foot in the country since 1945.

In 2017 the Jewish Museum in London included Marber as one of 18 designers in an exhibition entitled Designs on Britain, and his work is now conserved in the design archive of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

He is survived by Orna.

• Romek Marber, graphic designer, born 25 November 1925; died 30 March 2020

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dj Ki @ Diamant d’Or (LBA party, 2017) >> experimental/cinematic/IDM dj set

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Penguin Crime Series | Green Period / Cover designs by Romek Marber, 1960s >

#romek marber#penguin crime#graphic design#Raymond Chandler#georges simenon#dashiell hammett#book covers

1 note

·

View note

Photo

garadinervi: Romek Marber (1925-2020)♥(via Adrian Shaughnessy;... https://ift.tt/39uZthb Telegram Design Bot > https://t.me/gdesignbot

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

designer research

Romek Marber and Chris Ashworth

Contrast between the works of Romek Marber who followed precise, intricate grids inspired by the golden section and Chris Ashworth who takes a different approach; breaking the grid entirely.

Be

Romek Marber

Chris Ashworth

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Such a great cover on the new issue of the @penguincollsoc ‘Penguin Collector’ publication. Designed by Tom Etherington, based on designs by the great Romek Marber who passed away recently. #penginbooks #pelicanbooks #bookcollecting #penguincollectorssociety #bookcover #design #romekmarber https://www.instagram.com/p/CCot21dBueS/?igshid=1v4l1xhpnp0js

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

logo-archive: Credits and Discounts Cons. Romek Marber 1967, UK https://ift.tt/2uzHrvN

1 note

·

View note