#Richard Wollheim

Photo

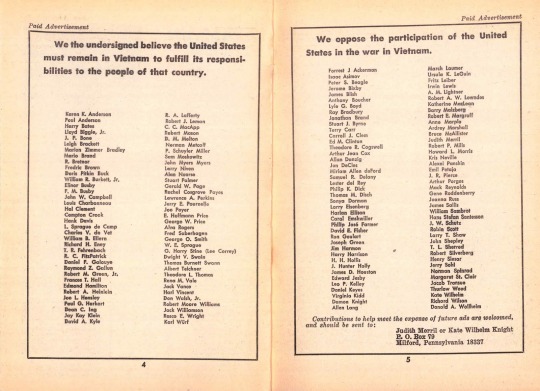

Vietnam War - Galaxy Science Fiction Magazine, June 1968

Sourced from: http://natsmusic.net/articles_galaxy_magazine_viet_nam_war.htm

Transcript Below

We the undersigned believe the United States must remain in Vietnam to fulfill its responsibilities to the people of that country.

Karen K. Anderson, Poul Anderson, Harry Bates, Lloyd Biggle Jr., J. F. Bone, Leigh Brackett, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Mario Brand, R. Bretnor, Frederic Brown, Doris Pitkin Buck, William R. Burkett Jr., Elinor Busby, F. M. Busby, John W. Campbell, Louis Charbonneau, Hal Clement, Compton Crook, Hank Davis, L. Sprague de Camp, Charles V. de Vet, William B. Ellern, Richard H. Eney, T. R. Fehrenbach, R. C. FitzPatrick, Daniel F. Galouye, Raymond Z. Gallun, Robert M. Green Jr., Frances T. Hall, Edmond Hamilton, Robert A. Heinlein, Joe L. Hensley, Paul G. Herkart, Dean C. Ing, Jay Kay Klein, David A. Kyle, R. A. Lafferty, Robert J. Leman, C. C. MacApp, Robert Mason, D. M. Melton, Norman Metcalf, P. Schuyler Miller, Sam Moskowitz, John Myers Myers, Larry Niven, Alan Nourse, Stuart Palmer, Gerald W. Page, Rachel Cosgrove Payes, Lawrence A. Perkins, Jerry E. Pournelle, Joe Poyer, E. Hoffmann Price, George W. Price, Alva Rogers, Fred Saberhagen, George O. Smith, W. E. Sprague, G. Harry Stine (Lee Correy), Dwight V. Swain, Thomas Burnett Swann, Albert Teichner, Theodore L. Thomas, Rena M. Vale, Jack Vance, Harl Vincent, Don Walsh Jr., Robert Moore Williams, Jack Williamson, Rosco E. Wright, Karl Würf.

We oppose the participation of the United States in the war in Vietnam.

Forrest J. Ackerman, Isaac Asimov, Peter S. Beagle, Jerome Bixby, James Blish, Anthony Boucher, Lyle G. Boyd, Ray Bradbury, Jonathan Brand, Stuart J. Byrne, Terry Carr, Carroll J. Clem, Ed M. Clinton, Theodore R. Cogswell, Arthur Jean Cox, Allan Danzig, Jon DeCles, Miriam Allen deFord, Samuel R. Delany, Lester del Rey, Philip K. Dick, Thomas M. Disch, Sonya Dorman, Larry Eisenberg, Harlan Ellison, Carol Emshwiller, Philip José Farmer, David E. Fisher, Ron Goulart, Joseph Green, Jim Harmon, Harry Harrison, H. H. Hollis, J. Hunter Holly, James D. Houston, Edward Jesby, Leo P. Kelley, Daniel Keyes, Virginia Kidd, Damon Knight, Allen Lang, March Laumer, Ursula K. LeGuin, Fritz Leiber, Irwin Lewis, A. M. Lightner, Robert A. W. Lowndes, Katherine MacLean, Barry Malzberg, Robert E. Margroff, Anne Marple, Ardrey Marshall, Bruce McAllister, Judith Merril, Robert P. Mills, Howard L. Morris, Kris Neville, Alexei Panshin, Emil Petaja, J. R. Pierce, Arthur Porges, Mack Reynolds, Gene Roddenberry, Joanna Russ, James Sallis, William Sambrot, Hans Stefan Santesson, J. W. Schutz, Robin Scott, Larry T. Shaw, John Shepley, T. L. Sherred, Robert Silverberg, Henry Slesar, Jerry Sohl, Norman Spinrad, Margaret St. Clair, Jacob Transue, Thurlow Weed, Kate Wilhelm, Richard Wilson, Donald A. Wollheim.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Gessner (1894-1989), Shell building under construction, 1929-30, oil on wood, 80,5 cm by 111,5 cm. Via Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin.

In 1919 Richard Gessner was a founding member of the artist circle “the Junge Rhineland”. In the ’20’s he married with the painter and art collector Lore Kegel. His works can be found in numerous museums. During his career he was a friend and colleague with Ernst Barlach, Otto Pankok, Gert Heinrich Wollheim, Marc Chagall, Franz Marc, Oskar Kokoschka, August Macke and other important artists of the 20th century who influenced his life and artistic style

0 notes

Text

Richard Corben's cover art for The 1975 Annual World's Best SF, edited by Arthur W. Saha & Donald A. Wollheim

1 note

·

View note

Text

Post 3 - Character and emotional response in the cinema

This article written by Murray Smith in 1994, explains the importance of narrative, and characters being an important aspect of films.

The approach of this article is conceptual. The article aims to address the question ‘What are the various senses of the term “identification”, and how they can be developed into a systematic explanation of emotional response to fictional characters?’

Characters are the most important part of the narrative structure.

“Our imaginative activity in the context of fiction, however, is both guided and constrained by the fiction's narration: the storytelling force that, in any given narrative film, presents causally linked events occurring in space across time.” (Smith, 1994, p. 35).

Recognition is another concept discussed in this article which is the process where the audience or spectator creates characters.

“Alignment describes the process by which spectators are placed in relation to characters in terms of access to their actions and to what they know and feel” (Smith, 1994, p. 41).

“Allegiance pertains to the moral and ideological evaluation of characters by the spectator” (Smith, 1994, p. 41). Allegiance is similar to identification, where the audience identifies with the characters based on their attributes, like their age, class and gender. Characters are judged and assessed based on the values they hold which determines the spectators allegiance with the character.

The article also discusses how our attraction, connection to characters or the dislike of characters affects our engagement with a media text.

The concept of identification is defined as how the audience relates to fictional characters.

Although this article was published in 1994, (nearly 30 years ago) the ideas are still relevant but the examples of texts are older. The article discusses The Thread of Life by Richard Wollheim, as well as Alfred Hitchcocks films.

“Hitchcock's films draw us "in" so completely that we "become" the protagonist: "the characters of Psycho are one character, and that character, thanks to the identifications the film evokes, is us," and this identification has a "therapeutic" effect.” (Smith, 1994, p. 37). Hitchcock’s films are good example of character engagement theories. Smith discusses The Man Who Knew Too Much in this article.

There is also this notion that the audience might share the same emotional states as the character and/or the protagonist an example used in this article is how in horror films we become frightened of the monster or villain like the protagonist is.

The article delved a lot into the topic of psychoanalysis which I found to be very complex.

Smith, M. (1994). Altered States: Character and Emotional Response in the Cinema. Cinema Journal, 33(4), 34–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/1225898

0 notes

Text

READINGS - Painting, Parapraxes, and Unconscious Intentions by Jeffrey L Geller.

Geller, Jeffrey L. “Painting, Parapraxes, and Unconscious Intentions.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 51, no. 3, July 1993, pp. 377–87.

“Richard Wollheim in Painting as an Art analyzes paintings as parapraxes, near-actions motivated in part by unconscious intentions. His analysis is a variant of intentionalism, whose first principle is that artworks are products of human action. For the purposes of his study, Wollheim defines intentions as “desires, thoughts, beliefs, experiences, emotions, [and] commitments, which cause the artist to paint as he does” (p.19), this opening the door for inquiries into both conscious and unconscious intentions” (Geller 377).

“In his treatment of unconsciously motivated paintings, Wollheim shows that the explanatory poles of painter and painting can be reversed. The painting reveals the painter’s intentions, his analyses show, no less than the painter’s intentions illuminate the painting” (Geller 377).

“Both argue that the painter and the painting are to be understood in tandem, that the two are inseparable from the point of view of art history” (Geller 377).

“Difficulties arise when the spectator is asked to appreciate a work that exceeds the horizon of her experience and imagination” (Geller 378).

“Painters whose works are worth viewing tap into a common ground of shared human experience that facilitates spectatorial appreciation. The common ground shared by spectators, including the painter in her spectatorial capacity, is “human nature”, the universality of which is a resource for communication and a guide to the artist as to the parameters of receptivity” (Geller 378).

“...though it is a matter of decision or convention what is the specific range of elements that the artist appropriates as his repertoire and out of which on any given occasion he makes his selection, underlying this there is a basis in nature to the communication of emotion…” (Qtd in Geller 379).

“The basis in nature is the universal element necessary for successful artistic expression. The criterion the painter used to evaluate his work in this regard is his own spectatorial response to the painting” (Geller 379).

“Instead of celebrating and “autonomous” creativity that places virtually impossible demands on spectators (since the mental states of artists who have gone out of their way to cultivate alienation are difficult to recapture), Wollheim’s theory celebrates the painter who is skilled at discerning the common ground that makes reception possible” (Geller 379).

“Painting functions on the same principles as language, according to this view, in that both derive their meaning from conventional codes and the interrelations among signifiers rather than from extra-semiotic reality” (Geller 380).

“To explain how the meaning of painting originates outside of an order of linguistic or quasi linguistic signifiers, Wollheim relies heavily on psychoanalysis” (Geller 381).

“To the extent that a painting is motivated by unconscious intentions, it is simultaneously the carrying out and the discovery of the painter’s intentions: it is the disclosure of the intentions behind the painting” (Geller 383).

“The emergence of archaic “sensations of sense” and “sensations of activity,” which in a sense “ground” human knowledge, according to Wollheim, demonstrate the expressive power of the primitive part of the human psyche” (Geller 383).

“When unconscious mental contents are expressed, it is important that they express themselves. Bearing this consideration in mind, it is clear that the painter needn’t and shouldn’t concern herself with the degree of match between her unconscious intentions and her painting. Such concern would only obstruct the expression of these very intentions” (Geller 385).

0 notes

Text

Richard Wollheim's Germs (Book acquired, 24 Dec. 2020)

Richard Wollheim’s Germs (Book acquired, 24 Dec. 2020)

Richard Wollheim’s memoir Germs is forthcoming from NYRB in February. Their blurb:

Germs is about first things, the seeds from which a life grows, as well as about the illnesses it incurs, the damage it sustains. Written at the end of the life of Richard Wollheim, a major British philosopher of the second half of the twentieth century, this memoir is not the usual story of growing up, but very…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

NYRB Fall Preview 2020: NYRB Classics (January 2021)

We wrap up our fall Classics preview with two nonfiction books out in January 2021: a strikingly sensory childhood memoir by a philosopher of the mind and a vital biography of the prophet Muhammad.

Stay tuned for more fall titles from NYRB Poets, New York Review Comics, Notting Hill Editions, and NYRB Kids.

Richard Wollheim, Germs: A Memoir of Childhood

This lyrical memoir from the major British philosopher is an surprising ode to the confusions of childhood. A lonely child, Wollheim’s early days were defined by sense and sensation, and he describes sights and scents with extraordinary power. As the Wall Street Journal put it, he’s “incapable of writing a bad sentence.” Sheila Heti, author of Motherhood and How Should a Person Be?, contributes the introduction.

Maxime Rodinson, Muhammad

First published in 1960 and called “essential” by Edward Said, this biography of Muhammad is an undisputed classic of the field. Rodinson, a Marxist historian who specialized in the Islamic world, traces the larger context of the Prophet’s life and calling—emphasizing his humanity all the while.

#maxime rodinson#muhammad#history of islam#edward said#richard wollheim#sheila heti#memoir#biography#literature#nyrb#nyrb classics#new york review books#nonfiction#fall 2020 preview

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

[British philosopher Richard Wollheim put all this another way.]

#s22e01 fish fries and feet#guy fieri#guyfieri#diners drive-ins and dives#british philosopher#richard wollheim#way

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Forwards, always forwards was the existentialist’s cry, but [Martin] Heidegger had long since pointed out that no one goes forwards forever. In ‘Being and Time’, he depicted Dasein as finding authenticity in 'Being-towards-death’, that is, in affirming mortality and limitation. He also set out to show that Being itself is not to be found on some eternal, changeless plane: it emerges through Time and through history. Thus, both on the cosmic level and in the lives of each one of us, all things are temporal and finite.

This idea of Being or human existence as

having an inbuilt expiry date never sat so well with [Jean-Paul] Sartre. He accepted it in principle, but everything in his personality revolted against being hemmed in by anything at all, least of all by death. As he wrote in 'Being and Nothingness’, death is an outrage that comes to me from outside and wipes out my projects. Death cannot be prepared for, or made my own; it’s not something to be resolute about, nor something to be incorporated and tamed. It is not one of my possibilities but 'the possibility that there are for me no longer any possibilities’. [Simone de] Beauvoir wrote a novel pointing out that immortality would be unbearable ('All Men Are Mortal’), but she too saw death as an alien intruder. In 'A Very Easy Death’, her 1964 account of her mother’s last illness, she showed how death came to her mother 'from elsewhere, strange and inhuman’. For Beauvoir, one cannot have a relationship with death, only with life.

The British philosopher Richard Wollheim put all this another way. Death, he wrote, is the great enemy not merely because it deprives us of all the future things we might do, and all the pleasures we might experience. It takes away the ability to experience anything at all, ever. It puts an end to our being a Heideggerian clearing for things to emerge into. Thus, as Wollheim says, 'It deprives us of phenomenology, and, having once tasted phenomenology, we develop a longing for it which we cannot give up.’ Having had experience of the world, having had intentionality we want to continue it forever, because that experience of the world is what we are.

Unfortunately this is the deal we get. We can taste phenomenology only because, one day, it will be taken from us. We clear our space, then the forest reclaims it again. The consolation is to have had the beauty of seeing light through the leaves at all: to have had something, rather than nothing.

Sarah Bakewell, ‘At the Existentialist Café’

#sarah bakewell#at the existentialist cafe#martin heidegger#simone de beauvoir#phenomenology#something rather than nothing#richard wollheim#death#mortality#limitation#freedom#existence#human existence

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Germs: A Memoir of Childhood by Richard Wollheim

It began when, about the age of nine or ten, I looked into a glass-fronted bookcase, and there saw, on the shelf below where my father kept his copies of the german classics, an ancient guidebook in six volumes, dating from the mid-eighteenth century, entitled The Environs of London. Bound in leather-covered board, the colour of pale creamy fudge, these volumes soon became my favourite reading of a certain sort. I say "of a certain sort" because, up till then, any book that captured my interest, such as a novel by Scott or Dickens, or by Kingsley or Harrison Ainsworth, or even by the much despised and now completely forgotten Jeffrey Farnol, whose daintiness deeply offended me, I would pick up, and starting on page 1, I would race through it as fast as my eyes could carry me, until some demand, like washing my hands, or getting ready to go out, forced me to put it down, and any other way of reading would have seemed to me to be as bad as, in fact as exactly like, driving through a town or village without catching its name, hence without being able to write it down, so that i had no way of feeling that I had actually been there. What made for a new sort of reading was to open the book at random, to read one page, and then perhaps the page before that, and then the page before that, or to leap a whole volume ahead and read a batch of pages, sometimes too fast to take any of them in. It was called, I soon learnt, "dipping into" a book, and it seemed not to matter that, when I had to put the book down, I couldn't, on coming back to it, always find where I left off, nor that I. often found myself reading the same pages more than once, and with the sense of learning something new. (pp. 80-81)

***

At the age of ten or eleven, I formulated a principle against friends. Friends, boys in the real world, with their interests in games and dirty jokes and lavatories, represented for me a dilution of the universe of the imagination, peopled by historical figures or the characters of Scott or Lamb's Tales. I said once to my mother as we drove to see a matinée of some play by Shakespeare, "I think that having friends is a weakness." She did not find this declaration worth a reply, and I sat on in silence, judging that this was not the stuff of which conversation was made. (pp. 90-91)

***

I longed to confide my doubts, but, though I formed the words, nothing came out. As always at home, I said nothing of what was on my mind, and I knew that to grow up, really to grow up, was not to do all the manly things I so much dreaded: it was to be able to break silence. (p. 96)

0 notes

Photo

‘The 1989 Annual World’s Best SF’ edited by Donald Wollheim, cover art by Richard Powers. via CoolSciFiCovers

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Acquaintance Principle:

Having the right to an aesthetic belief requires one to have experienced for oneself the object it concerns

- Richard Wollheim

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading about Richard Wollheim's definition of minimalism & it's great because it's helping me understand the mindset behind minimalist artwork / aesthetics but it's also reinforcing the fact that i genuinely really dislike minimalism & i think that it's wrong as an ideal. like i just disagree completely

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In her book October Child, Linda Boström Knausgård writes about an experience in a psych ward.

I plucked up my courage and said that, in the short term, I understood the wisdom of diverting your thoughts to get rid of the feeling of not being able to breathe, and continued by saying that the method of replacing one pain with another wasn’t going to get to the bottom of why I suddenly couldn’t breathe, and this applied to all human suffering, of course—this needing to understand the reason for the torment that makes life feels so unlivable—and why do you advocate electroconvulsive therapy when all that happens is that I forget everything that’s important to me, but then our time was up and the chief physician asked me to leave the room, as he noted in my files that I was to continue the treatment.

October Child is the latest in a series of books and articles I’ve read recently, like this piece on the philosopher Richard Wollheim’s memoir Germs or this obituary for Janet Malcolm, in which there seems to be an interest in the time when psychoanalysis, not behaviorism, was the dominant force in our frames of mental health and wellness. And a recognition of what we’ve lost now that behaviorism’s implicit assumptions—that behavior can be controlled by the adjustment of inputs and outputs (as the chief physician seeks to input various techniques to erase Boström Knausgård's sense that she simply can't go on), it can be optimized, and any behavior can be intervened in—structure so much of society, and so many of our habits of mind.

I admit I haven’t read Freud; this summary will be potted. But as I see it, in psychoanalysis, conflict can be unearthed, understood, but perhaps not solved. The resulting regard for human difficulty can be aloof and austere in its presentation. Analysts can seem like removed, somewhat cold authorities working to lead patients to something they already seem to know, whereas professionals of behaviorist schools behave in ways that seem more collegial, presenting to you the thought that causes your dysfunctional behavior and giving you the technique or action to try instead. But behaviorists seem more inclined to turn their benevolent authority into a tyranny, crossing the boundary that between analyst and analysand stays settled. If you can isolate a patient's problem as precisely as Boström Knausgård's chief physician can, at a certain point, you might think, Why work with you to fix it? Why not just reach in and fix it for you? Or change your environment such that it no longer develops. Such techniques are easy to scale and to systematize, too, where psychoanalysis remains firmly one individual in interaction with another.

And so, at its core, the analytic approach seems gentler than behaviorism, with the technocratic approach to the management of behavior it yields—and the “great story of psychiatry” it sees itself as heir to, as the blurb from the Gothenburg Post on the back of October Child puts it, “with its simple, ready-made answers” about how to fix what’s wrong with you and send you back in to the world that caused your suffering, this time as a better fit.

What's more, the aloofness and austerity I associate with psychoanalysis is more a quality of the practitioners than the patients. Here I’m thinking about Portnoy’s Complaint, which I’ve just read: its fast pace, its agility, its sheer life force, and all the joy Portnoy seems to feel in his psychological conflicts—with Jewishness, with neurosis, with his compulsive attraction to shikses and what it might say about him, with parents who frustrate and endear themselves to him by turns, with the desire to be his own person against the comforts of the solid, known identity they bequeathed him. So many of Portnoy's conflicts are inherited; none of them are resolved. There’s a manic vigor to the way Portnoy chews and chews them over as the book unfolds, an immersive and propulsive quality that takes you all the way up to its explosive punchline—when you figure out it's structured around a bit, a breathless monologue that perhaps hasn’t even been made, delivered entirely before Portnoy begins therapy at all. It's a delightful denouement to neurosis; you can only laugh.

October Child is also a terrifically written, immersive experience—but immersive in its despair rather than in its joy, and in the force of Boström Knausgård’s search for answers to her questions: Am I truly free? What can I do with the pain I feel? How can I escape what others expect of me when I can’t find the will to fulfill that? How do I live when my mind betrays me?

The fundamental question—why am I the way I am? and what can I do about it?— isn't one with a clear answer, but an eternal one, and psychoanalysis and psychodynamic therapy seems to have more space for the eternal questions than behaviorism does. And yet so much fiction that’s published now speaks to a world structured by behaviorist assumptions. Such a reductive regard for human behavior would seem to enervate the literature human minds can produce... Maybe, if more of us diverged from those assumptions—the belief that all our dysfunctions come from insufficiently managed inputs and outputs, and all our conflicts ought to be resolved—we could do something deeper than the kind of tortured ambivalence that—in, say, so much of the most popular autofiction—is the dominant mode.

Again, I enjoy autofiction. I enjoy the literary performance of anxiety and constriction, of the dead affects we assume when the pace of life and the amount of stimuli by which we're beset outstrip our capacity to deal, even as we were told the lives we're living now were the best any people had ever lived. And I enjoy the literary performance of the qualities we use to submerge or overcome anxiety: ambivalence or detachment in the Cusk mode, or verbosity and earnestness in the Lerner mode. These are valuable testaments to a particularly vicious time in our living memories and the deadening effects it's had. But at a certain point, I feel a desire for a book that’s not just descriptive but generative, a book in which I can know a self striving to be a self, in joy and in anguish; a self that's simply being, without calculating, without such self-consciousness, without anticipating how it's falling short or how you, the reader, will perceive it. Give me straightforward cries of joy, or despair. Give me feeling.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

9.10.2020

Today I had three online classes and it went pretty well but by the last one I just wanted it to end. It wasn’t boring but I already talked about the topics the teacher was talking about in three different occasions (in Roman Politics and Society, Latin Literature III and in Roman Culture), so I was pretty much distracted. But it was a good day, could’ve done more but tomorrow is saturday so I’m hoping to get a lot done.

Tomorrow I want to do some of my mandatory readings and others to help understand some parts better:

The story of David and the chapter on Judith (Bible)

The frogs by Aristophanes

A few chapters from Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Art and its Objects by Richard Wollheim

I don’t know if I’ll get to all of them but I hope to read most of it! 🤩

#studying#classics studyblr#studyspo studyblr#ovid#study#studyblr#studyspo#metamorphoses#classics#my stuff#uni#college#dark academia#24studying

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

T ed Klein’s The 13 Most Terrifying Horror Stories

1. “Casting the Runes” by M. R. James

Despite their cozy fireside atmosphere, James’s tales of poor doomed antiquarians always raise a chill. This one made a dandy film, Curse of the Demon. Other James masterpieces: “Count Magnus,” “The Ash-Tree,” and “The Treasure of Abbot Thomas.”

2. “Novel of the Black Seal” by Arthur Machen

Machen’s lyrical, visionary fiction tends to provoke wonder rather than fright, but this tale, about a surviving race of “Little People” in backwoods Wales, has moments of real terror. Also noteworthy: “The White People” and Machen’s little-known “Out of the Picture.”

3. “The Willows” by Algernon Blackwood

Otherworldly encroachments on a desolate island in the Danube. Lovecraft regarded this as the greatest horror story ever written; certainly it’s the greatest horror story about camping out.

4. “The Dunwich Horror” by H. P. Lovecraft

Quintessential HPL, mixing cosmic horror and a brooding New England locale. Another classic: “The Call of Cthulhu,” a documentary-style tale that takes the whole world as its province.

5. “Bird of Prey” by John Collier

Collier is renowned for his sophisticated wit, but in this account of a malevolent thing that hatches from an enormous egg, he’s also bloodcurdling—with the real shocker unveiled in the final line.

6. “Who Goes There?” by “Don A. Stuart” (John W. Campbell)

Antarctic horror, the genesis of The Thing. You may wonder, after reading it, if your best friend is actually a tentacled alien bent on world domination.

7. “They Bite” by Anthony Boucher

Boucher invents a totally new—and terrifyingly convincing—breed of monster, the desert-dwelling Carkers.

8. “Stay Off the Moon!” by Raymond F. Jones

Published in the December ’62 Amazing (and now thankfully out of date), the story suggests that something rather nasty lurks beneath the lunar surface. If the Apollo astronauts had read this one, they might have stayed home.

9. “Ottmar Balleau X 2” by George Bamber

First published in Rogue and then in Judith Merril’s seventh annual Year’s Best S-F (1963), the tale introduces us to a letter-writing psychopath who seems to have taken his cue from L. P. Hartley’s “W. S.”

10. “First Anniversary” by Richard Matheson

Just the thing for anyone who’s ever suspected that his wife isn’t entirely human. Domestic paranoia in full flower. Another fine example: Matheson’s “Prey,” which became a film to avoid watching alone.

11. “The Autopsy” by Michael Shea

Published in the December ’80 F&SF, this tale of alien possession in an isolated West Virginia mining community features a monster even more demonic than The Thing.

12. “The Trick” by Ramsey Campbell

Hopeless, inescapable horror from a child’s point of view, by the genre’s grimmest practitioner. Appears in Karl Wagner’s Year’s Best Horror #10. Other Campbell contenders: “Cold Print,” “The Interloper,” and “The End of a Summer’s Day.”

13. “To Build a Fire” by Jack London

Natural rather than supernatural horror: the harrowing account of a walk in the woods that becomes a race with death. Reminiscent, in its growing sense of dread, of Captain Scott’s doomed journey from the Pole.

Honorable mention to two literally monstrous tales from Donald A. Wollheim’s 1955 anthology Terror in the Modern Vein: “Fritzchen” by Charles Beaumont and “Mimic” by Wollheim himself; to Fritz Leiber’s meditation on Evil, “A Bit of the Dark World,” written to match its wonderful cover illustration in the February ’62 Fantastic; and to two short horror novels that, where so many fail, manage to sustain a sense of the uncanny—Ringstones by “Sarban” (John W. Wall) and The House on the Borderland by William Hope Hodgson.

Providence After Dark and Other Writings

8 notes

·

View notes