#Rereading gide

Text

After the wing of death has brushed you, what used to seem important is so no longer; other things are instead, things that didn't formally seem important or that you didn't even know existed. The accumulation of all acquired knowledge in our mind flakes away like a cosmetic and in places lets us see the bare flesh, the authentic being that was hidden.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Everything that needs to be said has already been said.

But since no one was listening, everything must be said again.

#rereading my copy of steal like an artist that i stole from a hotel ^^#lake ig#its an andre gide qoute fyi

0 notes

Text

i knew it. gide was daihannya all along

#rereading rewatching bsd#only to be reminded that miyano mamoru has such range#but like appearance-wise both daihannya and gide have white long hair#both tied said hair#personality-wise... well#the despair is more visible in gide than daihannya

1 note

·

View note

Note

https://www.tiktok.com/@bluemoon.mp4/video/7300937773001821442

I consider you the timeline expert so uhh thoughts on this?

tiktok video recap: OP was trying to deduce who between Dazai and Chuuya was older. OP said Atsushi was freshly turned 18 when he was kicked out of the orphanage, at the start of May, and since the are only a few weeks (only 2 though, not 4) between that and him meeting Dazai, it would mean Dazai's birthday at the end June hadn't passed yet, making it so Dazai was actually 23 now and a year older than Chuuya, whose birthday already passed in April. This is a take I've seen before.

I would say a solid attempt. I do like the idea of Atsushi being kicked out because he finally turned 18 and they finally could do it, but the truth is Japan's age of majority was 20 until 2022, not 18. It would make no sense for the orphanage to kick out a minor in normal conditions.

I'm also still saying there's a solid chance Asagiri doesn't really care about being accurate to the exact month, more just to the general year, but we have enough to take a guess and force things to work.

so.

I think there was too much emphasis put on the fact that skk are the same age for it to be true, and we don't actually have any proof Atsushi was kicked on his birthday, even if it is a legitimate guess to try and make.

(continued under the cut ↓ )

1) The light novel being titled "Dazai, Chuuya, Age Fifteen" when they are the same age for barely 2 months sounds a bit ridiculous, but also have these quotes to show in-story what they say:

2) Asagiri said he probably should have titled Storm Bringer "Dazai, Chuuya, Age Sixteen" for continuity, but didn't want to:

3) The SB -> Dragon's Head Conflict timeline I made was based on Chuuya's birthday, placing its start at around January-February, right before his 17th birthday. We know there were 2 years between the DHC and Dark Era as per Oda's words, and real life Oda Sakunosuke and André Gide died in January and February respectively, solidifying that attempted timeline. We know Dazai is 18 during Dark Era (+2 years underground to enter the ADA at 20). If Dazai was a year older than Chuuya, that timeline wouldn't be able to hold, as Dazai would actually be 19 and a half by that point. (refer to this graphic for a breakdown by month, adding a year to Dazai's count for this theory to "work": )

4) On that same note, SB takes place one year after Chuuya joined; the Flags were celebrating his one year in the mafia. Because of the July + 3 months mention, so after Dazai's birthday, we know for sure it couldn't have happened in the supposed two months they would be the same age.

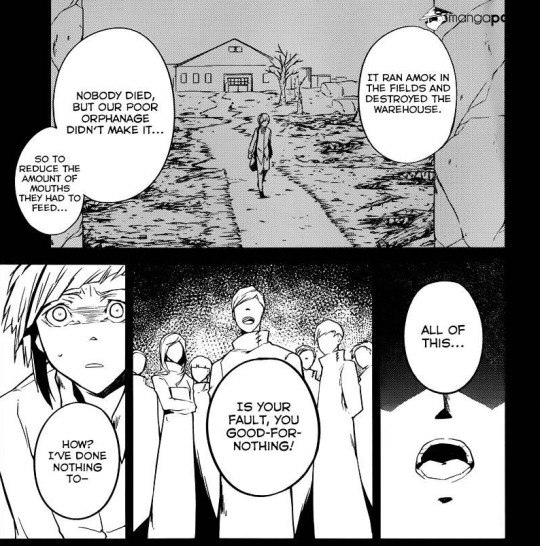

I also want to add that Atsushi never mentions being kicked out because he turned 18. The reason he gives Kunikida and Dazai is that the orphanage had to reduce the number of people in their care for monetary reasons after the Tiger attacked. Atsushi was always the scapegoat, so it wouldn't have surprised him to be the one kicked out, even if it was still frightening. Also again, an 18-year-old was a minor in Japan until very recently.

One very clear clue we have however, is 55 Minutes, which happens in the hottest part of summer. Asagiri said it happened sometime after vol10, so after the Guild arc. I would need to do a full reread to see how much time could have passed between the start of the series and the end of the Guild arc, but since all of it was happening around Atsushi and the Tiger (everyone was after the poor boy), we can probably fit it in a month or so (and make the ADA be so so tired afterwards)

As of now, I would place the start of the series more around July, after Dazai's birthday but before August so we have some leeway for 55 Minutes, but this will need a deeper dive to solidify the theory, and this post is getting too long.

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bungo stray dogs#bsd timeline#bsd analysis#bsd meta#?#skk#bsd atsushi#apparently i talk sometimes

104 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi just reread your master for the nth time and I just realized since the hunting dogs body will each and rot if they do not receive the surgery how would that work??????

hope you have a good day

Hello.

I am doing good. I also hope, that you have a nice day. 🥰

Hunting dogs are safe in this AU. They were lucky to appear at the certain point of canon.

Self-Aware! BSD. World Building. Canon chains

Warning: English is my second language. Spoilers for BSD Manga, LN and Anime.

_____

Canon chains - events and information that happened or were mentioned in canon.

Canon chains include events or information from:

Untold Origin Arc

Fifteen arc

STORMBRINGER arc

Day I Picked Up Dazai novel

Dark Era arc

Entrance Exam Arc

Gaiden (If I understand correctly, it happened somewhere here)

Port Mafia Arc

The Guild Arc

DEAD APPLE arc

Guild Aftermath Arc

Cannibalism arc

What happened or were mentioned in these arcs are, in some way, set in stone and can't be escaped.

BSD Cast understand it and don't try to change the outcome.

But, in time, Canon chains became more loose.

_______

1. From Untold Origin to Port Mafia arcs.

Chains are strong. They can't be broken. It that point, no matter, what characters do, they can't change

Example: Fifteen arc. Rimbaud's death would still happen. Even if Mori choose to lock Rimbaud up, at the moment of his death, the wound will appear on Rimbaud's body, killing him.

STORMBRINGER arc. Flags still would be dead, even if Verlaine decide to stay away from them.

Dead Era arc. Oda and Gide still would die, even if Oda will wear a full body armor during his fight with Gide or Gide will stay in the outskirts of Yokohama. Or Mori would ask someone else to investigate Ango's disappearance.

________

2. The Guild Arc, Dead Apple and The Guild Aftermath.

BSD Cast self-awareness are slowly destroying the chains of canon. The closer to The Cannibalism arc is, the more freedom in actions characters get.

Now, the outcome of events won't be the same.

Example. The Guild Arrival at Yokohama and their clash with ADA. In canon, it leads to Yosano healing other ADA members.

Now, there were no clash, and two sides just talked, sharing information. The consequences - ADA members feel sore for no reason, but, there is no need to Yosano's ability.

Another example. Akutagawa didn't fight against Mitchell and Hawthorne. Mitchell didn't get injures from Rasenmon out of nowhere, but she did feel sore for the next few days.

Another example. Q weren't captured, The Guild didn't try to use their ability to destroy Yokohama. Instead of mass destruction, there were some broken asphalt and that's all.

And, Fitzgerald and Shin Soukoku weren't fighting, they, once again, simply talked. Fitzgerald didn't lose all his money and wedding ring. Yes, he uses some sum of money and a tiny part of the ring, but, otherwise, he wasn't hurt.

_________

3. Cannibalism arc and so on.

Canon chains are barely holding. Characters almost get their freedom.

What made canon chains broke? Karma's fate.

At that point of time, almost everyone can hear your voice clearly. So, Fyodor, who became interested in you, after hearing, that you feel sorry for Karma, decide not to kill him and took Karma with him.

Starting from that point and beyond, chains are broken.

Only basic information (age, height, weight, likes, dislikes, ability) and what we learned during the new characters' first appearance are set in stone.

Their past remains mostly the same. So, Tachihara still a part of Hunting Dogs.

If, after that, something serious is added, it won't affect characters.

Example. In this AU Akutagawa isn't sick, because we learn about this after the Cannibalism arc and after Canon chains were destroyed.

From that point, all body alterations won't happen to the characters.

Example: Kunikida won't lose his arms, Tachihara won't be blinded. Both of them won't even feel an urge to itch.

As for Hunting Dogs surgeries.

From their first appearance, we learn, their names, why Hunting Dogs exit, and that they are super strong.

We didn't learn anything about mandatory surgeries and rotting bodies.

So, this information won't affect them. Hunting Dogs won't need them and could live in a real world without fearing for their lives.

102 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you ever thought of the parallels between Gide Vs Oda and Fyodor Vs Dazai? It hit me while rereading Dark Era and it’s was so devastating. I hope Dazai subverts it and doesn’t die like Oda.

I... can't say I have actually.

I can see it now. Both Gide and Fyodor take a vested interest in someone they see as similar to them - who can give them what they've been lacking. For Gide it's death, and for Fyodor it's a mental equal. Neither Oda nor Dazai seem to much care or think in any way highly of the other.

There's a supernatural quality at the center of it. Oda and Gide's abilities form a singularity. Dazai and Fyodor have some strange connection to the Book.

Oda and Gide are the only ones who can defeat the other. Dazai and Fyodor are the only ones who are an intellectual match.

The difference, op, is that Oda fought Gide while forsaking any of his bonds with others because he had given up on his own life and future. Dazai uses the strength of the bonds and trust he has in others in full, as he has not given up and is actively trying to hold on to life now.

Oda dies for many reasons, but from this perspective specifically, it's because he gave up on himself and fought alone. Dazai is clinging to his own life through the uncertainty and uses his connections instead of turning his back to them, which is why he survives his conflict with Fyodor.

Very interesting op. I will chew on this some more.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

BSD 114.5 SPOILERS

Ok so, a few things.

I was first thinking that this was a moment when the person who's body originally belonged to had a bit of control,

But at the same time it could've been fully planned by Fyodor for Sigma to find the note and do this act, but not fully dismissing the possibility of Fyodor taking advantage of what he had around to make it look that it was an act when it was actually the person who last killed him (aka, mix of both things)

Now moving to Fukuchi and Fyodor on the newest chapter

There is a chance that the character that appeared at the end of s5ep11 of the anime might be Fukuchi, since the character looks way to similar to him.

Now, why do I think this and how does it connect to the manga chapter 114.5? Easy, the tripolar singularity.

(BTW, WILL CONTAIN SPOILERS FROM THE 55MINUTES AND STORMBRINGER LIGHT NOVELS)

Throughout the BSD story, we´ve seen a few cases of singularties, when 2 abilities that are exactly the same go agaisnt one another (Sasunosuke Oda vs André Gide); an ability being used on itself (Chuuya's ability back when he was a child, before he was taken by N) and/or 2 abilities that contradict eachothers (example given by Wells to Atsushi during the Standard Island events).

In this case, Fyodor is using the Holy sword, Amenogozen and Fukuchi's ability.

--The Holy sword is seen previously be used to seal Bram and control his ability, not letting Bram use his own ability at will unless Fukuchi, who was the one who had sealed him, held the sword.

--Amenogozen allows the holder to cut through space and time.

--And lastly, Mirror Lion, Fukuchi's ability, allows him to significantly increase the power of any weapon he uses.

Seeing it this way, it's rather obvious that Fyodor wants to increase the power of Amenogozen for an specific reason.

And I cant help but connect the dots with the unknown character from the anime season finale.

It also makes a bit of sense to me, since the anime shows that character after mentioning its only been 2 hours after the supposed death of Fyodor and Fukuchi.

I think the fact that this 2 already powerfull swords combined with Mirrow Lion is the reason this tripolar singularity occurs and that the effect from that turns Fukuchi into the unknown character.

In a way it can be looked like Chuuya's and Verlaine's situation, both have singularities that make them look different from their usual self.

For Chuuya it's Corruption/Arahabaki (no, Arahabaki isn't a god using Chuuya as a vessel. Might do a post abt that in the future.) and for Verlaine it's Guivre

For Chuuya it makes him look unhinged(?) but in the Stormbringer it was also described that he would get dark wings, while Verlaine actually turned into a huge creature that could be compared to Godzilla (might not be completely acurrate, Im going through memory); so it could be completely possible for Fukuchi to get a new design through that moment which he's not in control of his body (again, just like Chuuya and Verlaine.)

---

So, Im actually feeling a bit sick as I try to finish writing this and dont have the will power to reread everything to know if I wrote everything I wanted plus checking if there's anything I wanted to write that I forgot-

Hope yall are having a good day and prob see you next month with this kind of posts ^^

(atp Im hoping for some day to be known as the dude who makes random bsd theories that sometimes go true-)

#talking hatrack#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bsd fyodor#bsd fukuchi#bsd s5 ep11#bsd 114.5#manga#anime#the hat uses it's brain for theories#<- just remembered I made that tag and I love it fr

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway since i'm talking about ango's back and forth - it's not a dark era thing only

oh, ango.

you fucking idiot

(what the fuck do you think dazai would do to you if you went through with it huh ? if he even know you /thought/ about it ?? the car would be mercy in comparison)

anyway the fun thing is. i just reread this, and it's the first time i notice how fucking hesitant he is about it. look at his face in the last panel. he looks like he's still struggling with himself to go through with what he's decided. he's taking a long time actually ! previous time i was too in his head and horrified by his conclusion to see it, but wow. dude doesn't want to do do this and i'm not sure he would be able to go through with it.

which makes sense ! that the man who went 'no i don't get along with chief takeda. he quantifies lives' and 'what is in those pages is not something you can get from 'three dead''. (which, btw, outside of ango's primary identity being 'odasaku and dazai's friend' and his loyalty ultmiately residing inside lupin, is why he told odasaku not to fight gide. because he refuses to reduce lives to number. he is - up til this moment - pretty coherent about it)

but this moment he does consider it. this moment he does go 'that is the rational number-driven thing to do. as a member of the special division, this is what i have to do', which is different from the way he has thought about it until now ! but. but. he also was. incredibly shaken by chief takeda's determination to include himself in the acceptable sacrifice. that shook him, and i think that's why, when this time, put in front of the 'yeah you need to kill this one person who doesn't deserve to die to save everything' he went against his usual conclusion. and, because it's the first time, has a fucking hard time going through with it.

(this said ango's hands aren't clean. that's something he's clear on, or at least he was clear on back during the dark era break up scene and i'm still boggling that the anime didn't include this :

"As part of an underground organization whose duties must be kept secret, as a skill user who hunts other skill users, I have been engulfed in the darkness of the government for too long. I shall never walk in the light again."

like seriously that says so fucking much about ango's self image back then, and his view of the special division, and his role in it, and his role as a spy ... seriously why did they not include it)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I did not meet anyone that day, and I was at ease. I pulled a small book of Homer out of my pocket that I had not reopened since my departure from Marseille. I reread three sentences from the Odyssey, memorized them, and found a thread in the rhythm that gave me pleasure. I closed the book and sat there, trembling, more alive than I could have believed one could be, my spirit numb with happiness.

— Andre Gide, The Immoralist

0 notes

Text

"Just believe me when I say that when I want Ortus to go, he'll be Gide-gone." This did not make much sense to you as a joke.

so I was listening to the HtN audiobook today (my first of probably many rereads) and the fact that you can only understand this stupid name pun on reread once you know about the whole Ortus = Gideon ctrl-f replace situation in Harrow's lobotomized brain is amazing.

#this is just so funny to me that this pun is hidden behind plot-important details#augustine i applaud the joke and i am saddened that harrow literally could not get it#also that jod's amazing dad joke is also plot relevant#i love these books so much#harrow the ninth#harrow the ninth spoilers#htn#tlt#the locked tomb

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey I promised this a long time ago but my depressed ass didn't let me write so

Analyzing Atsushi and Akutagawa pt.2

cw: dazai hate and beast spoilers

previous part here

first of all I want to clarify that this has been sitting in my drafts for nearly a whole year so yeah it's very likely that I might forget some important details but I'll try to get to my initial point anyways.

a few month ago when I decided to reread beast for a second time (after realising I hadn't paid much attention to it the first time) I came up with all these ideas of how and why Dazai decided to pair Akutagawa and Atsushi together.

again, this analysis is going to be a very real-life-based interpretation on the characters and the whole plot probably. so don't really pay much attention if I mix stuff from the light novels with stuff from the main plot bc the point is basically analyse why their relationship was built.

parting from the final scenes of the beast novel that end with Dazai telling Atsushi and Akutagawa that he needed to make them fight each other in order to protect the world he had created for Oda inside the book, I tried to tie a few ends that were hanging lose for a while in my head.

now, you can read this however you like (be it me being just stupid or whatever) but, ever since we got to see part of how Dazai treated Akutagawa back in the Port Mafia I kept finding myself going through the same problem over and over again to try and understand why the hell was he so fucking obsessed with making him physically stronger rather than, you know, actually focusing on training him as a whole good and worthy subordinate.

why did dazai, being as smart and manipulative as he is, made such a rudimentary mistake of only teaching akutagawa how to strengthen his ability if he knew the boy was a killing machine?

I think you can understand then why the part where Dazai makes them fight each other in beast was even MORE confusing to me...

but that's not all there is to it.

Dazai not only failed (?) to train Akutagawa but he did succeed in training Atsushi??

well, as much as we love to see a character growing and as much as you'd like to attribute it to him leaving the mafia, I don't really think that was the reason. after all, as I already said, Dazai is very smart and has always been, he probably already had it all planned back in the port mafia.

and here's where my galaxy brain starts to think.

right from the start, the whole Dazai's subordinates deal felt very strange and inconsistent to me. I never understood why would he loose so much for Akutagawa and obsess so much with pointing out the fact that Atsushi was better than him when he was no longer part of the PM therefore he supposedly shouldn't mind about wether Akutagawa was good bad or whatever.

it started getting very dense to me tbh but that's not important

enter beast, a world where Dazai can literally do almost anything he wants, and what does he do? the boy goes and straight up fucks up akutagawa and atsushi for the second time makes akutagawa and atsushi hate each other and hold the weight of the world in their hands. again.

ok this was getting VERY annoying, plus their fight was so so so painful to read that it literally made me wonder what was the point in forcing them to face their trauma in such a cruel way at a moment like that.

thankfully there was a reason... but it never clarified precisely WHY FIGHT EACH OTHER.

if Dazai never taught Akutagawa how to be a better and sharper person because he didn't really know how, that was not a problem in beast. because Oda was there to do it. Oda could have taught Akutagawa what Dazai lacked as a mentor.

then, if Dazai wanted Atsushi to protect the book, he could've literally ask him without any need to involve Akutagawa.

but then, the whole point of why Dazai took Akutagawa in the first time "in the original world" and the reason behind why he also took Atsushi would've been lost.

Dazai is, indeed, a mastermind.

he knows what's necessary to make a world where people like Oda can live and write. he knows, probably better than anyone, that god doesn't care about things like balance and harmony. that he'd have to create it himself.

after all, coherency is one of the rules of the book.

Akutagawa and Atsushi fail their mission against Fukuchi (probably at Aku's life cost) in the main plot because that happened in the same world where Oda and Gide die after fighting for the same goal. a world where only those who fight and have the talent will prevail.

Dazai knows very well that, in that world, balance and harmony will never exist.

that's why Dazai creates a new world instead, where Atsushi and Akutagawa never team up and try to kill each other instead. a world where they force each other to recognize their flaws and admit their mistakes, a world where they'll have to learn how to live on with it no matter what they want to protect the world.

protect the world by proving that both sides of the same coin can fit, that none is better than the other.

so yeah, basically, the events that take place in "the original world" are proof to Dazai that god doesn't care about good or evil, that the only ones that will prevail are those who fight for their right to live (and this also probably explains why Atsushi and Akutagawa will never win as long as they fight without acknowledging what they have in front of them).

therefore, he decides to create a world where Oda won't have to fight to live because Atsushi and Akutagawa will fight but won't have to kill each other to prove their existence. they'll simply accept that both sides of the coin can exist even if they're weak, afraid or bad and that will be enough to give birth to a new world order.

there's actually more than this. in fact, there are a lot of reasons why Akutagawa and Atsushi are important for each other despite Dazai's plans and the world's destiny. however, since it'd be too confusing to try explaining it all in the same post sooo I'll be leaving that for a 3rd part.

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bsd beast#bsd dazai#bsd atsushi#bsd akutagawa#sskk#can't believe it took me so long to write this#and I still couldn't say what I wanted bc it's too long#analysis time

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

OdaGide | 600 words

Wrote for a rarepair for my morning writing exercise: about artist!Gide and writer!Oda chilling on the couch and just creating art with each other.

Every canvas he had ever owned had been washed with black, ash and charcoal, that miraculously — and Oda meant it when he lifted his gaze from his journal, just as ink began to crawl and began to seep into his clothes — would never smear or leave the four corners of its world.

It was as self-contained as a garden plot, where the trees and bramble and the shoots and roses would only grow inward and upward, never spilling past its threshold. Because beyond the red bricks and the square they were used to, none could really exist and maybe, the air wasn’t good enough. In that there was more nitrogen or hydrogen or sodium than they were used to and that the plants would steer clear because of their particular appetite.

Or perhaps, it wasn’t hunger; but rather, fear that kept them be. Fear of being pruned had set them straight and away from the hacksaw of a pair of scissors. That would’ve trimmed every arm, every foliage from a finger, every flower coming forth on this eve of midsummer. Were this the narrative of a dystopian garden plot, maybe Oda would’ve been onto something when he clicked the ballpoint of his pen. Stepping away from the metaphor and the story he was tangled in: perhaps, it wasn’t fear that deterred every drawing from spilling beyond its borders.

But rather, it was the planning and the precision of his control whenever Gide would etch out for a shape to take hold. He would hold his piece of charcoal, his paintbrush, his pencil in such a way that it lent itself to only bleed on an empty page. And Oda could only count with a finger and a thumb, the number of times he had actually seen his boyfriend rolling-up his sleeves before he worked. And for a writer, such as himself, there was a little tinge of green that had darkened his glimpse before Oda dropped and reread most of the story he had written.

He didn’t believe that either he or him held their tools that differently whenever they marked-up a journal page, but maybe the difference could be stemmed from their approaches. Much how Oda would splatter some words so that later he could refer back to something when he didn’t know where to go while Gide knew exactly what he wished and wanted, nothing could distract him while he etched his final product.

And if Oda stole a glance to see what he had made, Gide would roll his journal away from prying eyes and would thumb with his toes that Oda could wait for a later in longer. And in response, Oda would roll his own journal back, he would clutch at its ears as if it were a clipboard while scribbling a squiggle in lieu of writing words. And Gide would mime something similar into thin air, blowing it towards his love and Oda would dodge it by not looking.

But in the end, he would look with a soft smile on his face and would poke back with his pinkie toe before resting it beside a calf. And Gide would do the same as nuzzled into the couch, occasionally glancing up to his boyfriend and ink clinging to his cuffs. Already imagining how their late-night would turn out: bent over a tub while helping Oda wring his clothes, booping bits of soap and leaving them on each other’s noses. Where a huff to no avail could shake off the bubbles, but a splash of bathwater would leave a hiss and some laughter.

#bungou stray dogs#bsd#oda sakunosuke#andré gide#andre gide#odagide#bsd ficlet#writing exercise#fanfic writing#fanfic writer

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smuggler

“Then what are you complaining about?”

“About hypocrisy. About lies. About misrepresentation. About that smuggler’s behavior to which you drive the uranist.”

—André Gide, Corydon, Fourth Dialogue

1.

I REMEMBER MY first kiss with absolute clarity. I was reading on a black chaise longue, upholstered with shiny velour, and it was right after dinner, the hour of freedom before I was obliged to begin my homework. I was sixteen.

It must have been early autumn or late spring, because I know I was in school at the time, and the sun was still out. I was shocked and thrilled by it, and reading that passage, from a novel by Hermann Hesse, made the book feel intensely real, fusing Hesse’s imaginary world with the physical object I was holding in my hands. I looked down at it, and back at the words on the page, and then around the room, which was empty, and I felt a keen and deep sense of discovery and shame. Something new had entered my life, undetected by anyone else, delivered safely and surreptitiously to me alone. To borrow an idea from André Gide, I had become a smuggler.

It wasn’t, of course, the first kiss I had encountered in a book. But this was the first kiss between two boys, characters in Beneath the Wheel, a short, sad novel about a sensitive student who gains admission to an elite school but then fails, quickly and inexorably, after he becomes entwined in friendship with a reckless, poetic classmate. I was stunned by their encounter—which most readers, and almost certainly Hesse himself, would have assigned to that liminal stage of adolescence before boys turn definitively to heterosexual interests. For me, however, it was the first evidence that I wasn’t entirely alone in my own desires. It made my loneliness seem more present to me, more intelligible and tangible, and something that could be named. Even more shocking was the innocence with which Hesse presented it:

An adult witnessing this little scene might have derived a quiet joy from it, from the tenderly inept shyness and the earnestness of these two narrow faces, both of them handsome, promising, boyish yet marked half with childish grace and half with shy yet attractive adolescent defiance.

Certainly no adult I knew would have derived anything like joy from this little scene—far from it. Where I grew up, a decaying Rust Belt city in upstate New York, there was no tradition of schoolboy romance, at least none that had made it to my public high school, where the hierarchies were rigid, the social categories inviolable, the avenues for sexual expression strictly and collectively policed by adults and youth alike. These were the early days of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, when recent gains in visibility and political legitimacy for gay rights were being vigorously countered by a newly resurgent cultural conservatism. The adults in my world, had they witnessed two lonely young boys reach out to each other in passionate friendship, would have thrashed them before committing them to the counsel of religion or psychiatry.

But the discovery of that kiss changed me. Reading, which had seemed a retreat from the world, was suddenly more vital, dangerous, and necessary. If before I had read haphazardly, bouncing from adventure to history to novels and the classics, now I read with focus and determination. For the next five years, I sought to expand and open the tiny fissure that had been created by that kiss. Suddenly, after years of feeling almost entirely disconnected from the sexual world, my reading was finally spurred both by curiosity and Eros.

From an oppressive theological academy in southern Germany, where students struggled to learn Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, to the rooftops of Paris during the final days of Adolf Hitler’s occupation, I sought in books the company of poets and scholars, hoodlums and thieves, tormented aristocrats bouncing around the spas and casinos of Europe, expat Americans slumming it in the City of Light, an introspective Roman emperor lamenting a lost boyfriend, and a middle-aged author at the height of his powers and the brink of exhaustion. These were the worlds, and the men, presented by Gide, Jean Cocteau, Oscar Wilde, Jean Genet, James Baldwin, Thomas Mann, and Robert Musil, to name only those whose writing has lingered with me. Some of these authors were linked by ties of friendship. Some of them were themselves more or less openly homosexual, others ambiguous or fluid in their desires, and others, by all evidence, bisexual or primarily heterosexual. It would be too much to say their work formed a canon of gay literature—but for those who sought such a canon, their work was about all one could find.

And yet, in retrospect, and after rereading many of those books more than thirty years later, I’m astonished by how sad, furtive, and destructive an image of sexuality they presented. Today we have an insipid idea of literature as selfdiscovery, and a reflexive conviction that young people—especially those struggling with identity or prejudice—need role models. But these books contained no role models at all, and they depicted self-discovery as a cataclysmic severance from society. The price of survival, for the self-aware homosexual, was a complete inversion of values, dislocation, wandering, and rebellion. One of the few traditions you were allowed to keep was misogyny. And most of the men represented in these books were not willing to pay the heavy price of rebellion and were, to appropriate Hesse’s phrase, ground beneath the wheel.

The value of these books wasn’t anything wholesome they contained, or any moral instruction they offered. Rather, it was the process of finding them, the thrill of reading them, the way the books themselves, like the men they depicted, detached you from the familiar moral landscape. They gave a name to the palpable, physical loneliness of sexual solitude, but they also greatly increased your intellectual and emotional solitude. Until very recently, the canon of literature for a gay kid was discovered entirely alone, by threads of connection that linked authors from intertwined demimondes. It was smuggling, but also scavenging. There was no Internet, no “customers who bought this item also bought,” no helpful librarians steeped in the discourse of tolerance and diversity, and certainly no one in the adult world who could be trusted to give advice and advance the project of limning this still mostly forbidden body of work.

The pleasure of finding new access to these worlds was almost always punctured by the bleakness of the books themselves. One of the two boys who kissed in that Hesse novel eventually came apart at the seams, lapsed into nervous exhaustion, and then one afternoon, after too much beer, he stumbled or willingly slid into a slow-moving river, where his body was found, like Ophelia’s, floating serenely and beautiful in the chilly waters. Hesse would blame poor Hans’s collapse on the severity of his education and a lamentable disconnection from nature, friendship, and congenial social structures. But surely that kiss, and that friendship with a wayward poet, had something to do with it. As Hans is broken to pieces, he remembers that kiss, a sign that at some level Hesse felt it must be punished.

Hans was relatively lucky, dispensed with chaste, poetic discretion, like the lover in a song cycle by Franz Schubert or Robert Schumann. Other boys who found themselves enmeshed in the milieu of homoerotic desire were raped, bullied, or killed, or lapsed into madness, disease, or criminality. They were disposable or interchangeable, the objects of pederastic fixation or the instrumental playthings of adult characters going through aesthetic, moral, or existential crises. Even the survivors face, at the end of these novels, the bleakest existential crises. Even the survivors face, at the end of these novels, the bleakest of futures: isolation, wandering, and a perverse form of aging in which the loss of youth is never compensated with wisdom.

One doesn’t expect novelists to give us happy endings. But looking back on many of the books I read during my age of smuggling, I’m profoundly disturbed by what I now recognize as their deeply entrenched homophobia. I wonder if it took a toll on me, if what seemed a process of self-liberation was inseparable from infection with the insecurities, evasions, and hypocrisy stamped into gay identity during the painful, formative decades of its nascence in the last century. I wonder how these books will survive, and in what form: historical documents, symptoms of an ugly era, cris de coeur of men (mostly men) who had made it only a few steps along the long road to true equality? Will we condescend to them, and treat their anguish with polite, clinical detachment? I hesitate to say that these books formed me, because that suggests too simplistic a connection between literature and character. But I can’t be the only gay man in middle age who now wonders if what seemed a gift at the time—the discovery of a literature of same-sex desire just respectable enough to circulate without suspicion—was in fact more toxic than a youth of that era could ever have anticipated.

2.

Before the mid-1990s, when the Internet began to collapse the distinction between cities, suburbs, and everywhere else, books were the most reliable access to the larger world, and the only access to books was the bookstore or the library. The physical fact of a book was both a curse and a blessing. It made reading a potentially dangerous act if you were reading the wrong things, and of course one had to physically find and possess the book. But the mere fact of being a book, the fact that someone had published the words and they were circulating in the world, gave a book the presumption of respectability, especially if it was deemed “literature.” There were, of course, bad or dangerous books in the world—and self-appointed guardians who sought to suppress and destroy them—but decent people assumed that these were safely contained within universities.

I borrowed my copy of Hesse’s Beneath the Wheel from the library, so I can’t be sure whether it contained any of the small clues that led to other like-minded books. At least one copy I have found in a used bookstore does have an invaluable signpost on the back cover: “Along with Heinrich Mann’s The Blue Angel, Emil Strauss’s Friend Death, and Robert Musil’s Young Törless, all of which came out in the same period, it belongs to the genre of school novels.” Perhaps that’s what prompted me to read Musil’s far more complicated, beautifully written, and excruciating schoolboy saga. Hans, shy, studious, and trusting, led me to Törless, a bolder, meaner, more dangerous boy.

Other threads of connection came from the introductions, afterwords, footnotes, and the solicitations to buy other books found just inside the back cover. When I first started reading independently of classroom assignments and the usual boy’s diet of Rudyard Kipling, Jonathan Swift, Alexandre Dumas, and Jules Verne—reading without guidance and with all the odd detours and byways of an autodidact—I devised a three-part test for choosing a new volume: first, a book had to have a black or orange spine, then the colors of Penguin Classics, which someone had assured me was a reliable brand; second, I had to be able to finish the book within a few days, lest I waste the opportunity of my weekly visit to the bookstore; and third, I had to be hooked by the narrative within one or two pages. That is certainly what led me, by chance, to Cocteau’s Les Enfants Terribles, a rather slight and pretentious novel of incestuous infatuation, gender slippage, homoerotic desire, and surreal distortions of time and space. I knew nothing of Cocteau but was intrigued by one of his line drawings on the cover, which showed two androgynous teenagers, and a summary which assured it was about a boy named Paul, who worshipped a fellow student.

I still have that copy of Cocteau. In the back there was yet more treasure, a whole page devoted to advertising the novels of Gide (The Immoralist is described as “the story of man’s rebellion against social and sexual conformity”) and another to Genet (The Thief’s Journal is “a voyage of discovery beyond all moral laws; the expression of a philosophy of perverted vice, the working out of an aesthetic degradation”). These little précis were themselves a guide to the coded language—“illicit, corruption, hedonism”—that often, though not infallibly, led to other enticing books. And yet one might follow these little broken twigs and crushed leaves only to end up in the frustrating world of mere decadence, Wagnerian salons, undirected voluptuousness, the enervating eccentricities of Joris-Karl Huysmans or the chaste, coy allusions to vice in Wilde.

Finally, there were a handful of narratives that had successfully transitioned into open and public respectability, even if always slightly tainted by scandal. If the local theater company still performed Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, who could fault a boy for reading The Picture of Dorian Gray?

Conveniently, a 1982 Bantam Classics edition contained both, and also the play Salomé. Wilde’s novel was a skein of brilliant banter stretched over a rather silly, Gothic tale, and the hiding-in-plain-sight of its homoeroticism was deeply unfulfilling. Even then, too scared to openly acknowledge my own feelings, I found Wilde’s obfuscations embarrassing. More powerful than anything in the highly contrived and overwrought games of Dorian was a passing moment in Salomé when the Page of Herodias obliquely confesses his love for the Young Syrian, who has committed suicide in disgust at Salomé’s licentious display. “He has killed himself,” the boy laments, “the man who was my friend! I gave him a little box of perfumes and earrings wrought in silver, and now he has killed himself.” It was these moments that slipped through, sudden intimations of honest feeling, which made plowing through Wilde’s self-indulgence worth the effort.

Then there was the most holy and terrifying of all the publicly respectable representations of homosexual desire, Mann’s Death in Venice, which might even be found in one’s parents’ library, the danger of its sexuality safely ossified inside the imposing façade of its reputation. A boy who read Death in Venice wasn’t slavering over a beautiful Polish adolescent in a sailor’s suit, he was climbing a mountain of sorts, proving his devotion to culture.

But a boy who read Death in Venicewas receiving a very strange moral and sentimental education. Great love was somehow linked to intellectual crisis, a symptom of mental exhaustion. It was entirely inward and unrequited, and it was likely triggered by some dislocation of the self from familiar surroundings, to travel, new sights and smells, and hot climates. It was unsettling and isolating, and drove one to humiliating vanities and abject voyeurism. Like so much of what one found in Wilde (perfumed and swaddled in cant), Gide (transplanted to the colonial realms of North Africa, where bourgeois morality was suspended), or Genet (floating freely in the postwar wreckage and flotsam of values, ideals, and norms), Death in Venice also required a young reader to locate himself somewhere on the inexorable axis of pederastic desire.

In retrospect I understand that this fixation on older men who suddenly have their worlds shattered by the brilliant beauty of a young man or adolescent was an intentional, even ironic repurposing of the classical approbation of Platonic pederasty. It allowed the “uranist”—to use the pejorative Victorian term for a homosexual—to broach, tentatively and under the cover of a venerable and respected literary tradition, the broader subject of same-sex desire. While for some, especially Gide, pederasty was the ideal, for others it may have been a gateway to discussing desire among men of relatively equal age and status, what we now think of as being gay. But as an eighteen-year-old reader, I had no interest in being on the receiving end of the attentions of older men; and as a middle-aged man, no interest in children.

The dynamics of the pederastic dyad—like so many narratives of colonialism —also meant that in most cases the boy was silent, seemingly without an intellectual or moral life. He was pure object, pure receptivity, unprotesting, perfect and perfectly silent in his beauty. When Benjamin Britten composed his last opera, based on Mann’s novella, the youth is portrayed by a dancer, voiceless in a world of singing, present only as an ideal body moving in space. In Gide’s Immoralist, the boys of Algeria (and Italy and France) are interchangeable, lost in the torrents of monologue from the narrator, Michel, who wants us to believe that they are mere instruments in his long, agonizing process of self-discovery and liberation. In Genet’s Funeral Rites, a frequently pornographic novel of sexual violence among the partisans and collaborators of Paris during the liberation, the narrator/author even attempts to make a virtue of the interchangeability of his young objects of desire: “The characters in my books all resemble each other,” he says. He’s right, and he amplifies their sameness by suppressing or eliding their personalities, dropping identifying names or pronouns as he shifts between their individual stories, often reducing them to anonymous body parts.

By reducing boys and young men to ciphers, the narrative space becomes open for untrammeled displays of solipsism, narcissism, self-pity, and of course self-justification. These books, written over a period of decades, by authors of vastly different temperaments and sexualities, are surprisingly alike in this claustrophobia of desire and subjugation of the other. Indeed, the psychological violence done to the male object of desire is often worse in authors who didn’t manifest any particular personal interest in same-sex desire. For example, in Musil’s Confusions of Young Törless, a gentle and slightly effeminate boy named Basini becomes a tool for the social, intellectual, and emotional advancement of three classmates who are all, presumably, destined to get married and lead entirely heterosexual lives. One student uses Basini to learn how to exercise power and manipulate people in preparation for a life of public accomplishment; another tortures him to test his confused spiritual theories, a stew of supposedly Eastern mysticism; and Törless turns to him, and turns on him, simply to feel something, to sense his presence and power in the world, to add to the stockroom of his mind and soul.

We are led to believe that this last form of manipulation is, in its effect on poor Basini, the cruelest. Later in the book, when Musil offers us the classic irony of the bildungsroman—the guarantee that everything that has happened was just a phase, a way station on the path of authorial evolution—he explains why Törless “never felt remorse” for what he did to Basini:

For the only real interest [that “aesthetically inclined intellectuals” like the older Törless] feel is concentrated on the growth of their own soul, or personality, or whatever one may call the thing within us that every now and then increases by the addition of some idea picked up between the lines of a book, or which speaks to us in the silent language of a painting[,] the thing that every now and then awakens when some solitary, wayward tune floats past us and away, away into the distance, whence with alien movements tugs at the thin scarlet thread of our blood —the thing that is never there when we are writing minutes, building machines, going to the circus, or following any of the hundreds of other similar occupations.

The conquest of beautiful boys, whether a hallowed tradition of all-male schools or the vestigial remnant of classical poetry, is simply another way to add to one’s fund of poetic and emotional knowledge, like going to the symphony. Today we might be blunter: to refine his aesthetic sensibility, Törless participated in the rape, torture, humiliation, and emotional abuse of a gay kid.

And he did it in a confined space. It is a recurring theme (and perhaps cliché) of many of these novels that homoerotic desire must be bounded within narrow spaces, dark rooms, private attics, as if the breach in conventional morality opened by same-sex desire demands careful, diligent, and architectural containment. The boys who beat and sodomize Basini do it in a secret space in the attic above their prep school. Throughout much of Cocteau’s Les Enfants Terribles, two siblings inhabit a darkly enchanted room, bickering and berating each other as they attempt to displace unrequited or forbidden desires onto acceptable alternatives. Cocteau helpfully gives us a sketch of this room—a few wispy lines that suggest something that Henri Matisse might have painted—with two beds, parallel to each other, as if in a hospital ward. Sickness, of course, is ever-present throughout almost all of these novels as well: the cholera that kills Aschenbach in Death in Venice, the tuberculosis which Michel overcomes and to which his hapless wife succumbs in The Immoralist, and the pallor, ennui, listlessness, and fevers of Cocteau. James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, a later, more deeply ambivalent contribution to this canon of illness and enclosure, takes its name from the cramped, cluttered chambre de bonne that contains this desire, with the narrator keenly aware that if what happens there—a passionate relationship between a young American man in Paris and his Italian boyfriend— escapes that space, the world of possibilities for gay men would explode. But floods of booze, perhaps alcoholism, and an almost suicidal emotional frailty haunt this space, too.

Often it is the author’s relation to these dark spaces that gives us our only reliable sense of how he envisioned the historical trajectory of being gay. In Cocteau’s novel, the room becomes a ship, or a portal, transporting the youth Cocteau’s novel, the room becomes a ship, or a portal, transporting the youth into the larger world of adult desires. The lines are fluid, but there is a possibility of connection between the perfervid world of contained sexuality and the larger universe of sanctioned desires. In Baldwin, the young Italian proposes the two men keep their room as a space apart, a refuge for secret assignations, even as his American lover prepares to reunite with his fiancée and return to a life of normative sexuality. They could continue their relationship privately, on the side, a quiet compromise between two sexual realms. But Musil’s attic, essentially a torture chamber, is a much more desperate space, a permanent ghetto for illicit desire.

Even those among these books that were self-consciously written to advance the cause of gay men, to make their anguish more comprehensible to a reflexively hostile straight audience, leave almost no room—no space—for many openly gay readers. The parallels with colonial discourse are troubling: the colonized “other,” the homosexual making his appeal to straight society, must in turn pass on the violence and colonize and suppress yet weaker or more marginal figures on the spectrum of sexuality. Thus in the last of Gide’s daring dialogues in defense of homosexuality, first published piecemeal, then together commercially as Corydon in 1924—a tedious book full of pseudoscience and speculative extensions of Darwinian theory—the narrator contemptuously dismisses the unmanly homosexual: “If you please, we’ll leave the inverts aside for now. The trouble is that ill-informed people confuse them with normal homosexuals. And you understand, I hope, what I mean by ‘inverts.’ After all, heterosexuality too includes certain degenerates, people who are sick and obsessed.”

Along with the effeminate, the old and the aging are also beneath contempt. The casual scorn in Mann’s novella for an older man whom Aschenbach encounters on his passage to Venice is almost as horrifying as the sexual abuse and mental torture of young Basini in Musil’s novel. Among gay men, Mann’s painted clown is one of the most unsettling figures in literature, a “young-old man” whom Mann calls a “repulsive sight.” He apes the manners and dress of youth but has false teeth and bad makeup, luridly colored clothing, and a rakish hat, and is desperately trying to run with a younger crowd of men: “He was an old man, beyond a doubt, with wrinkles and crow’s feet round eyes and mouth; the dull carmine of the cheeks was rouge, the brown hair a wig.” Mann’s writing rises to a suspiciously incandescent brilliance in his descriptions of this supposedly loathsome figure. For reasons entirely unnecessary to the plot or development of his central characters, Baldwin resurrects Mann’s grotesquerie, in a phantasmagorical scene that describes an encounter between his young

American protagonist and a nameless old “queen” who approaches him in a bar:

American protagonist and a nameless old “queen” who approaches him in a bar:

The face was white and thoroughly bloodless with some kind of foundation cream; it stank of powder and a gardenia-like perfume. The shirt, open coquettishly to the navel, revealed a hairless chest and a silver crucifix; the shirt was covered with paper-thin wafers, red and green and orange and yellow and blue, which stormed in the light and made one feel that the mummy might, at any moment, disappear in flame.

This is the future to which the narrator—and by extension the reader if he is a gay man—is condemned. Unless, of course, he succumbs to disease or addiction. At best there is a retreat from society, perhaps to someplace where the economic differential between the Western pederast and the colonized boy makes an endless string of anonymous liaisons economically feasible. Violent death is the worst of the escapes. Not content with merely parodying older gay men, Baldwin must also murder them. In a scene that does gratuitous violence to the basic voice and continuity of the book, the narrator imagines in intimate detail events he has not actually witnessed: the murder of a flamboyant bar owner who sexually harasses and extorts the young Giovanni (by this point betrayed, abandoned, and reduced to what is, in effect, prostitution). The murder happens behind closed doors, safely contained in a room filled with “silks, colors, perfumes.”

3.

If I remember with absolute clarity the first same-sex kiss I encountered in literature, I don’t remember very well when my interest in specifically homoerotic narrative began to wane. But again, thanks to the physicality of the book, I have an archaeology more reliable than memory. As a young reader, I was in the habit of writing the date when I finished a book on the inside front cover, and so I know that sometime shortly before I turned twenty-one, my passion for dark tales of unrequited desire, sexual manipulation, and destructive Nietzschean paroxysms of self-transcendence peaked, then flagged. That was also the same time that I came out to friends and family, which was prompted by the complete loss of hope that a long and unrequited love for a classmate might be returned. Logic suggests that these events were related, that the collapse of romantic illusions and the subsequent initiation of an actual erotic life with real, living people dulled the allure of Wilde, Gide, Mann, and the other authors who were loosely in their various orbits.

were loosely in their various orbits.

It happened this way: For several years I had been drawn to a young man who seemed to me curiously like Hans from Hesse’s novel. Physically, at least, they were alike: “Deep-set, uneasy eyes glowed dimly in his handsome and delicate face; fine wrinkles, signs of troubled thinking, twitched on his forehead, and his thin, emaciated arms and hands hung at his side with the weary gracefulness reminiscent of a figure by Botticelli.” But in every other way my beloved was an invention. I projected onto him an elaborate but entirely imaginary psychology, which I now suspect was cobbled together from bits and pieces of the books I had been reading. He was sad, silent, and doomed, like Hans, but also cold, remote, and severe, like Törless, cruelly beautiful like all the interchangeable sailors and hoodlums in Genet, but also intellectual, suffering, and mystically connected to dark truths from which I was excluded. When I recklessly confessed my love to him—how long I had nurtured it and how complex, beautiful, and poetic it was—he responded not with anger or disgust but impatience: “You can’t put all this on me.”

He was right. It took me only a few days to realize it intellectually, a few weeks to begin accepting it emotionally, and a few years not to feel fear and shame in his presence. He had recognized in an instant that what I had felt for years, rather like Swann for Odette, had nothing to do with him. It wasn’t even love, properly speaking. I can’t claim that it was all clear to me at the time, that I was conscious of any connection between what I had read and the excruciating dead end of my own fantasy life. I make these connections in retrospect. But the realization that I would never be with him because he didn’t in fact exist—not in the way I imagined him—must have soured me on the literature of longing, torment, and convoluted desire. And the challenge and excitement of negotiating a genuine erotic life rendered so much of what I had found in these books painfully dated and irrelevant.

I want to be rigorously honest about my feelings for this literature, whether it distorted my sense of self and even, perhaps, corrupted my imagination. The safe thing to say is that I can’t possibly find an answer to that, not simply because memory is unreliable, but because we never know whether books implant things in us or merely confirm what is already there. In Young Törless, Musil proposes the idea that the great literature of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and William Shakespeare is essentially a transitional crutch for young minds, a mental prosthesis or substitute identity during the formlessness of adolescence: “These associations originating outside, and these borrowed emotions, carry young people over the dangerously soft spiritual ground of the years in which they need to be of some significance to themselves and nevertheless are still too incomplete to have any real significance.”

It’s important to divorce the question of how these books may have influenced me from the malicious accusations of corruption that have dogged gay fiction from the beginning. In the course of our reading lives, we will devour dozens, perhaps hundreds, of crude, scabrous, violent books, with no discernible impact on our moral constitution. And homosexual writers certainly didn’t invent the general connection between sexuality and illness, or the thin line between passion and violence, or sadism and masochism, or the sexual exploitation of the young or defenseless. And the mere mention of same-sex desire is still seen in too many places around the world today as inherently destructive to young minds. Gide’s Corydon decried the illogic of this a century ago: “And if, in spite of advice, invitations, provocations of all kinds, he should manifest a homosexual tendency, you immediately blame his reading or some other influence (and you argue in the same way for an entire nation, an entire people); it has to be an acquired taste, you insist; he must have been taught it; you refuse to admit that he might have invented it all by himself.”

And I want to register an important caveat about the literature of same-sex desire: it is not limited to the books I read, the authors I encountered, or the tropes that now seem to me so sad and destructive. In 1928, E. M. Forster wrote a short story called “Arthur Snatchfold” that wasn’t published until 1972, two years after the author’s death. In it, an older man, Sir Richard Conway, respectable in all ways, visits the country estate of a business acquaintance, where he has a quick, early-morning sexual encounter with a young deliveryman in a field near the house. Later, as Sir Richard chats with his host at their club in London, he learns that the liaison was seen by a policeman, the young man was arrested, and the authorities sent him to prison. To his great relief, Sir Richard also learns that he himself is safe from discovery, that the “other man” was never identified, and despite great pressure on the working-class man to incriminate his upper-class partner, he refused to do so.

“He [the deliveryman] was instantly removed from the court and as he went he shouted back at us—you’ll never credit this—that if he and the old grandfather didn’t mind it why should anyone else,” says Sir Richard’s host, fatuously indignant about the whole affair. Sir Richard, ashamed and sad but trapped in the armor of his social position, does the only thing he can: “Taking a notebook from his pocket, he wrote down the name of his lover, yes, his lover who was going to prison to save him, in order that he might not forget it.” It isn’t a great story, but it is an important moment in the evolution of an idea of loyalty and honor within the emerging category of homosexual identity. I didn’t

discover it until years after it might have done me some good.

Forster’s story is exceptional because only one man is punished, and he is given a voice—and a final, clear, unequivocal protest against the injustice. The other man escapes, but into shame, guilt, and self-recrimination. And yet it is the escapee who takes up the pen and begins to write. We might say of Sir Richard what we often say of our parents as we come to peace with them: he did the best he could. And for all the internalized homophobia of the authors I began reading more than thirty years ago, I would say the same thing. They did the best they could. They certainly did far more than privately inscribe a name in a book. I can’t honestly say that I would have had even Sir Richard’s limited courage in 1928.

But Forster’s story, which he didn’t dare publish while he was alive, is the exception, not the rule. It is painful to read the bulk of this early canon, and it will only become more and more painful, as gay subcultures dissolve and the bourgeois respectability that so many of these authors abandoned yet craved becomes the norm. In Genet, marriage between two men was the ultimate profanation, one of the strongest inversions of value the author could muster to scandalize his audience and delight his rebellious readers. The image of samesex marriage was purely explosive, a strategy for blasting apart the hypocrisy and pretentions of traditional morality. Today it is becoming commonplace.

I wonder if these books will survive like the literature of abolition, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin—marginal, dated, remembered as important for its earnest, sentimental ambition but also a catalogue of stereotypes. Or if they will be mostly forgotten, like the nineteenth-century literature of aesthetic perversity and decadence that many of these authors so deeply admired. Will Gide and Genet be as obscure to readers as Huysmans and the Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore-Lucien Ducasse)?

I hope not, and not least because they mattered to me, and helped forge a common language of reference among many gay men of my generation. I hope they survive for the many poignant epitaphs they contain, grave markers for the men who were used, abused, and banished from their pages. Let me write them down in my notebook, so I don’t forget their names: Hans, who loved Hermann; Basini, who loved Törless; the Page of Herodias, who loved the Young Syrian; Giovanni, who loved David; and all the rest, unnamed, often with no voice, but not forgotten.

TIM KREIDER

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been tagged by my lovely mama bear @doctorbeam in this little game so let’s do it because I have some physical chemistry to ignore

Top 3 ships: As Annie said, it might come as a surprise or not the fact that KnotTew are STILL my number one ship. Listen, I have not watched Sotus S nor I accept it’s existence, so KnotTew. Other than this, Yu Hao/Zi Xuan from Crossing The Line and Martino/Niccolo from Skam Italia are my babies that never fail to make me soft.

Last song: Ok call me cheesy or whatever but I’ve been listening to I wanna grow old with you by Westlife on repeat.

Last movie: I've watched Tales from the Golden Age with my boyfriend last week I think and we loved it. It’s a Romanian movie.

Reading: I've been trying to reread The Counterfeiters by Andre Gide but I really need more free time and I don’t have it sadly.

Watching: Until we meet again and Why R U the series. Thinking of watching some movies too, maybe Buffalo 66.

What food are you craving right now?: Damn I really need to stop eating today bc I’ve been munching non stop the whole day. So nothing (maybe the chips next to me).

Lipstick or chapstick: Neither? I hate the feeling of chapstick on my lips I swear.

Totally Spies or the Powerpuff Girls: So hear me out, growing up I only had on TV the channel that broadcasted Powerpuff Girls, not the one that broadcasted Totally Spies. I was watching Totally Spies sporadically when I was over at my cousin’s house so Powerpuff Girls it is.

Tagging: Imma tag my babe @bl-archer along with some of my recent faves that I really need to get closer to (I’m sorry I’m like this) @audoldends, @decadentdeerpolice @somewhatavidreader and @heartsdesire456 (you don’t need to do it if you don’t wanna!!)

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

1 3 4 6 7 30 for the book ask

1. Which book would you consider the best book you’ve ever read and why?

Already answered! But if I had to give another one, it would be “Les Faux-monnayeurs” by André Gide.

I studied it in Junior year as part of my literature course, and it’s probably the best example of omniscient narrator I came across. There are a lot of characters but you get to know each and every one of them, sympathize with a few, hate some others; and not only is it well-written and interesting on a thematic level, but the plot itself is also compelling once you get into it (even better as a reread because you notice all the symbolism, foreshadowing, etc.) Gide said he didn’t want to write a slice of life but take a big fat block of life and turn it into a novel, and I’d say he succeeded.

3. Are there any genres you will not read?

Not really, I’m open to anything. But seeing as I’m super picky too, you’ll have to convince me to pick up the book in the first place. Thing is a lot of “adult” fiction bore me to death, and I’m getting too old for YA fiction where the main character(s) aren’t given a reality check by adults, or are treated as the Only Sane Person™/The Chosen One In All But Name™. Give me a mix of both: compelling plot and characters, but also a dose of experience and maturity.

4. Are you a fast or slow reader?

I’m really not sure. I devore books but I don’t know if I finish them quickly compared to other readers, or if I’m average. Probably average.

6. Are you the type of person who will read a book to the end whether you like it or not, or will you put it down straight away if you’re not feeling into it?

I put it down. Either way I’ll regret having bought it, so I might as well not torture myself if it’s really that bad. And if I’m just not feeling it because I’m not in the mood, then I’ll store it away for a better time!

7. Have you ever despised something you have read?

There are no words, no words to tell you how much I despise “13 Reas*ns Why” and the series it spawned. The story itself is good for a teen drama, it’s a page-turner and you want to know what happens next. But I hate the way it treats its subject matter. I hate even more the way the series treats its subject matter. It does so many things wrong I can’t even enjoy the story, it just makes me angry.

30. Have you ever written your own book?

I currently am! Granted it’s not finished, but this year I’ve decided to get serious with my writing as I plan to become an indie author down the road (and publish in French obviously, but also perhaps in English if I find a way).

The book I’m working is the first one of a series about superheroes (seeing as I keep reblogging DC/PMMM stuff it shouldn’t come as a big surprise), and it will be part of a bigger universe. It’s a lot of work but I like it this way; and I want to use it to talk about pretty personal stuff, like depression, the search for/loss of identity in an exploitative system, and how we choose which battles to fight. Honestly the superhero stuff is mostly used as a metaphor, but I also want to pay homage to a genre I grew up with and fell in love with all over again.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

sent to her just under a year ago

Did you have a good trip? Are your efforts to secure something stable going well? I asked really; this really did happen, and said

What have I been doing and dabbling with…really I’ve become as regular and orderly as can be: lots of writing (whoop-de-doo!) by hand, on typewriter and thought dumps into Word docs……….and courageous, brave correspondence when I can muster it. Reading, too much Twitter and some books, mostly just immersed in whatever my fancy goes to. I dunno, I have been sitting around and staying inside a lot, an intense cerebrality (I’m inventing a word) but not for much longer: I have sold my car and donated some clothes and am going to stay with a friend in New York starting weekend after next, with no plan to return. Being there should be a good kick in the pants to “figure it out”, or to keep writing clearly about how “it” cannot be “figured out” and as ever, I will see what I can do with my mind and persona/real self

“Pain or love or danger makes you real again"

— Jack Kerouac

i’m rereading her/this because it’s a museum, and (”and” taken to its maximal degree, a hot flight up and out to the sun; i keep believing in random unspooling foolishness based on wherever the heart goes—randomness and discipline; i keep singing the “siren” song on my laptop screen telling myself i’m a good boy, “girlfriend” and “boss” replaced with “I”—me became them all, swallowed the world like other dead greats who look like me, e.g.

“If one does not absorb everything, one loses oneself completely. The mind must be greater than the world and contain it…”

https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/08/04/andre-gide-originality/

sent down a flight of stares because i read something because i felt something and went searching; we’re both still here, separate and equal in the arts—her a publishing professional (an editor, star search, removing the/my impurities; ah, this romance of destruction and risk, patience and huge upside; literary success is a cock fight

“You have a curious way of arousing one's imagination, stimulating all one's nerves, and making one's pulses beat faster. You put an aureole on vice, provided only if it is honest. Your ideal is a daring courtesan of genius. Oh, you are the kind of man who will corrupt a woman to her very last fiber.”

― Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, Venus in Furs

“in memory of last year”

Zadie Smith talked onstage about how she Does It for those going through linear time with her/us ~ all of (ion) us still listening (his art is free to be typos; anarchic kingdom of automatic perfection—a place to revise the rules; this place is not gonna be the other place—this is gonna be my rule

^ there—this was about kingdoms and rulers

But you have to say, “Well, who is going to be my ruler?” — almost on a moment-by-moment basis.

https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/06/15/cheryl-strayed-longform-podcast-interview/

this is a cascade of clickability; it is a matrix in which you can dissolve ~ the pattern is everywhere, this is not about my work or me, it’s about the everythingness of everything which at first probably makes you sick like magic mushrooms

it is a very gentle act to not get sick like this

“I'm sick of everything, and of the everythingness of everything.”

― Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

if you so feel inclined to brew something (:

she puts the mouth first, before the eyes . . .

i paired “Ambrosial regression” with a picture of two flames; she asked what it meant, i probably meant your breath is mine, palpable, i don’t want to live alone, can’t be alone in this fervor exploding my gut—FEELING leads to literature, a gateway drug of false and false permanences crashing like masks piled (see? you’ve unhinged me—duologue of author and poetess enflamed, a cyst, vibration, fibrosis fiberoptic Renaissance swallowing all thesaurus rex velociraptor queen on her color

the terrible art is, to stay in integrity, i can’t bother you with having written this; it only comes to life if not-you finds it, becomes her (you) oh—alone, singing well the pain of nobody being here with anyone, everybody sovereign in their box and corner, even during touch

you’re such a cute little bumpkin, kissable

Ah, hah no. I don’t think text is a very full-proof way of communicating so maybe because it is so fallible it’s less inspiring to me and I tend to slack more in this vein

you could use my veins as a slackline and dance —

“I have stretched ropes from steeple to steeple; Garlands from window to window; Golden chains from star to star ... And I dance.”

― Arthur Rimbaud, Complete Works

“complete works” — lies, popular lies, possibly recyclable belief; temporary confidence becomes a bag to milk, slash, collect the coins; ah, belief is so liquid — the carnival-barkers must know; oh, am I showing you all I know? I could get rich off everybody being sad if I both play and coach and commentate and own the team(s) at once...man, another Man trying to be All, to swim up to the heights, the barren heights of success or cleverness, of dressing well, smirking well, another dumb blonde on his arm, the latest version

“The echo mocks her origin to prove she is the original.”

― Rabindranath Tagore, Stray Birds

since i’ve been gone i succeeded but i’ll think of you at Christmas / but i know seeing my name is too costly for you, and to your flow cylindrical (see how I’ll imagine you as anything just to keep you in circulation?

My mother once pointed out oleander and said “drought-resistant but incredibly toxic”

“There is nothing to save, now all is lost,

but a tiny core of stillness in the heart

like the eye of a violet.”

― D.H. Lawrence

if there was only one speck of purple left on the plate, would it be enough to live on? it would if we were younger and still stupid—we’d think we could do anything; we were finely matched—our attraction would break through our armored personalities constructed in sad millennial survival games...now we’re too wise, are aware of where and how we’re wanted and why; all love and want now is partial in some way; endless sad judgments always haunt the brain, the looking; pure beauty is rare, crashing my prism and telescope system scanning scenes for predators, calculating vectors, skeptical and zeroed in on others’ strategic hunger and starvation for numbers going up, boxes to check to cure some feral fear ~ I’m too smart to work traditionally; I’m an art monster self-starving down to his last breath, artificial juncture — now it’s just noise, let the grievance-tap drip, let the little chipmunk invent new sounds, improve his fathers’ design, broomstick collage homage to witches

There’s no freedom in the pandemic so I think we’re okay there for once 😷

ah—how beautiful: she thought we were OK; she wanted (oh God, her wanting is so real; to think I was the object once is enough for all skies, for rest for generations after my death...my soul shall fly on these wings

Alis volat propriis is a Latin phrase used as the motto ... "She flies with her own wings"

she never needed a man; only what he represented - a safety net in a world that can’t offer safety; no President, no Father—all titles null and void, so I babysit us in this groundlessness; I am saying poets are the new and only-ever authorities; it is an argument that must leviathan-slither up from groundlings writing like Shakespeare to the Seen scene organized by ticket price and venue, distance and clutch

...in closing, i went looking for a quote about a woman who, when she went to give herself away & make herself accessible, could not locate herself. Was it D.H. Lawrence, H.L. Mencken, Sylvia Plath? All artists of the thing(s) that can’t be located, grasping at relief of feeling too much, trying to convert enthusiasm into a means to have a pretty life: it could never be true, it would always cost everything—Shakespeare had to become the one who could write about those painful things with clarity; that took distance. Every writer a hiker away from the real thing, breaking his back to not lose access.

1 note

·

View note