#Refugee Relief Board in St. Louis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Knights of Liberty - Wikipedia

Pictured here is Moses Dickson, from the frontispiece illustration of the 1879 book A Manual of the Knights of Tabor and Daughters of the Tabernacle. In 1872, the Rev. Moses Dickson founded the International Order of Twelve of Knights and Daughters of Tabor, an African-American fraternal order focused on benevolence and financial programs. Dickson was born a free man in Cincinnati in 1824, was a Union soldier during the Civil War, and afterwards became a prominent clergyman in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Dickson showed an interest in progressive fraternal organizations early on – in 1846 Dickson, with others, founded a society known as the Knights of Liberty, whose objective was to overthrow slavery; the group did not get beyond the organizing stages. Dickson was also involved in Freemasonry – he was the second Grand Master of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Missouri.

Dickson’s International Order of Twelve of Knights and Daughters of Tabor – or Order of Twelve, as it’s more commonly know – accepted men and women on equal terms. Men and women met together in higher level groups and in the governance of the organization, although at the local level they met separately – the men in “temples” and the women in “tabernacles” (akin to “lodges” in Freemasonry). The Order of Twelve was most prominent in the South and the lower Midwest. The major benefits to members – similar to many fraternal orders of the time – was a burial policy and weekly cash payments for the sick.

What many people today remember about the Order of Twelve is an institution founded in Mound Bayou, Misssissippi in 1942 – the Taborian Hospital. Michael Premo, a Story Corps facilitator, posted his appreciation for the impact that the Taborian Hospital had on the lives of African-Americans living in the Mississippi Delta from the 1940s-1960s. The Taborian Hospital was on the Mississippi Heritage Trust’s 10 Most Endangered List of 2000, and an update to that list indicates that the hospital still stands vacant and seeks funding for renovation. Here are some photos of the Taborian Hospital today.

Want to learn more about the Order of Twelve? Here are a few primary and secondary sources that we have here in our collection (with primary sources listed first):

Dickson, Moses. A Manual of the Knights of Tabor and Daughters of the Tabernacle, including the Ceremonies of the Order, Constitutions, Installations, Dedications, and Funerals, with Forms, and the Taborian Drill and Tactics. St. Louis, Mo. : G. I. Jones [printer], 1879. Call number: RARE HS 2259 .T3 D5 1879

—-. Ritual of Taborian Knighthood, including : the Uniform Rank. St. Louis, Mo. : A. R. Fleming & Co., printers, 1889. Call number: RARE HS 2230 .T3 D5 1889

Beito, David. From Mutual Aid to the Welfare State: Fraternal Societies and Social services, 1890-1967. Chapel Hill, N.C. : University of North Carolina Press, 2000. Call number: 44 .B423 2000

Skocpol, Theda, Ariane Liazos, Marshall Ganz. What a Mighty Power We Can Be : African American Fraternal Groups and the Struggle for Racial Equality. Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2006. Call number: 90 .S616 2006 (1)

(1) From The National Heritage Museum - http://nationalheritagemuseum.typepad.com/library_and_archives/2008/05/moses-dickson-a.html

SOME ADDITIONAL INTERESTING INFORMATION ABOUT MOSES DICKSON

Moses Dickson, prior to the Civil War was a traveling barber. Later he became an AME minister and was known as Father Dickson.

He was one of the Founders of the Lincoln Institute, now Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Misouri.

In 1879 along with others such as James Milton Turner, John Wheeler and John Turner he helped create the Committee of Twenty Five, organized to set up temporary housing for the more than 10,000 travelers who passed through St. Louis each year.

He was President of the Refugee Relief Board in St. Louis which helped to shelter and feed 16,000 former slaves who relocated to Kansas.

Moses Dickson was the first Grand Lecturer of the Most Worhipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Missouri upon its foundation in 1865. He was the second Grand Master of this Grand Lodge and the Grand Secretary in 1869.

In 1876 Companion Moses dickson was elected Deputy Grand High Priest of the Grand Chapter of Holy Royal Arch Masons of Missouri and Jurisdiction.

Moses Dickson wrote the Ritual of Heroines of Jericho penning the “Master Mason’s Daughter,” the “True Kinsman,” and “Heroines of Jericho” degrees. It was sold and distributed by the Moses Dickson Regalia and Supply Co., Kansas City, Missouri and entered into the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. in the year 1895.

The Knights of Liberty was organized by 12 Black Men in secret in August, 1846 in St. Louis, Missouri. They were also known as the Knights of Tabor or the International Order of Twelve. Tabor is a Biblical mountain in Israel where the Israelites won a big victory over the Canaanites.

Moses Dickson was a leader of the Underground Railroad. He and 47,000 other Knights enlisted in the Union Army as soon as Linclon authorized Black men to sign up.

Disbanded by the Civil War many of the Knights of Liberty reformed after the War was over into a benevolent fraternal society named the International Order of the Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor. Moses Dickson authored “International Order of Twelve 333 of Knights and Daughters of Tabor,” a book outlining the Constitution, Rules and Regulations of the Temples of the Uniform Rank of Tabor and Taborian Division.

Moses Dickson died on November 28, 1901. A truly remarkable man!

Originally published at the National Heritage Museum’s blog. The National Heritage Museum is an American history museum founded and supported by 32° Scottish Rite Freemasons in the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction of the United States of America.

#Moses Dickson and The Knights of Liberty#Moses Dickson#Knights of Liberty#Black Revolutionaries#International Order of Twelve#Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor#International Order of Twelve 333#Committee of Twenty Five#St Louis#missouri#freedom#Freedmen#Refugee Relief Board in St. Louis#Ritual of Heroines of Jericho#oes

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minister Moses Dickson (April 5, 1824 - November 28, 1901) was born free in Cincinnati. Orphaned by the age of 13, he became a barber to support himself, finding work on steamboats moving through the South and Midwest.

He helped organize two secret abolitionist organizations with like-minded Black men he met while working on the rivers. The Knights of Liberty, founded in St. Louis in 1846, sought to organize enslaved people throughout the South, train them in military tactics, and by 1857, lead them in a massive uprising that never came to fruition. The Order of Twelve, another abolitionist organization, founded in Galena, Illinois, in 1848, included future politicians Alfred H. Richardson and Richard Harvey Cain.

He married Mary Elizabeth Butcher (1848-1891). He continued to work on steamships like the Oronoco and the Nominee and the couple moved from Galena to Saint Paul.

He was likely the first Black business owner in St. Paul, operating Nonpareil Restaurant and Dickson’s Eating Saloon, followed by barbershops in the Fuller House and Winslow House hotels. He was the first teacher of African American students.

He wrote a letter to the Minnesota Weekly Times condemning the SCOTUS’s 1857 Dred Scott Decision. Mary gave birth to their only child. He signed a required free negro bond with former St. Louis mayor John How acting as his guarantor.

After the Civil War, he co-founded Lincoln University with a group of USCT Veterans. He became an ordained minister in the AME Church and opened schools and churches in St. Louis.

He was a delegate at every Republican State Convention in Missouri between (1864-78) and he cofounded the Missouri Equal Rights League. He was an elector-at-large for President Ulysses S. Grant. He was named consul at the Port of Victoria in the Seychelles. He held a leadership role with the Refugee Relief Board that aided the Exodusters.

He was active with the Prince Hall Masons, helping found lodges throughout the Midwest. He married Ina, but the two divorced a few years later. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

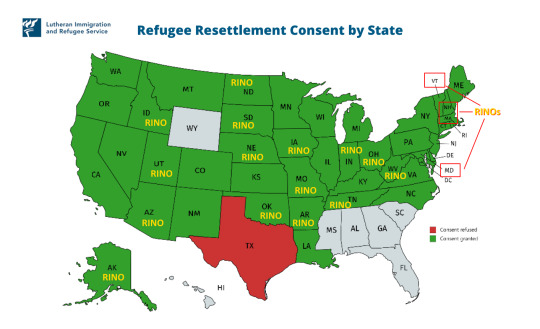

42 governors, including at least 19 Republicans, consent to resettle MORE refugees

How to turn red states blue, and first world third. Trump should have ended the fraudulent refugee resettlement program on day one in office.

youtube

Read more at Refugee Resettlement Watch via Three More Republican Governors Turn on Trump, Cave to Leftists on Refugee Program Reform

The list below is from one of the taxpayer-funded enemies within who is flooding America with refugees and flipping cowardly, weak-kneed Republicans (in name only). via Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services

Governors who have given consent

Gov. Wolf (D-PA) Public Statement and Letter of Consent

Gov. Whitmer (D-MI) Public Statement and Letter of Consent

Gov. Mike DeWine (R-OH) Public Statement via Spokesperson

Gov. Murphy (D-NJ) Public Statement and Letter of Consent

Gov. Polis (D-CO) Public Statement and Letter of Consent

Gov. Grisham (D-NM) Letter of Consent

Gov. Baker (R-MA) Public Statement and Letter of Consent

Gov. Kate Brown (D-OR) Letter of Consent and Tweet

Gov. Gary Herbert (R-UT) Letter of Consent (& Salt Lake Tribune Article)

Gov. Jay Inslee (D-WA) Letter of Consent

Gov. Burgum (R-ND) Public Statement, Consent Letter, and AP article

Gov. Northam (D-VA) Press Release and Letter of Consent

Gov. Sununu (R-NH) Letter of Consent and AP Article

Governor Steve Bullock (D-MT) Letter of Consent

Governor Laura Kelly (D-KS) Letter of Consent and Press Release

Governor Ducey (R-AZ) Letter of Consent and Article

Governor Cooper (D-NC) Letter of Consent

Governor Lamont (D-CT) Letter of Consent

Governor John Carney (D-DE) Letter of Consent

Governor Kim Reynolds (R-IA) Letter of Consent

Governor Tim Walz (D-MN) Letter of Consent and Press Release

Governor Gina Raimondo (D-RI) Letter of Consent

Governor Eric Holcomb (R-IN) Letter of Consent

Governor J.B. Pritzker (D-IL) Public Statement with Expected Consent and Letter of Consent

Governor Bill Lee (R-TN) Letter of Consent, Press Release, and Letter to the Lt. Governor & State Speaker of the House

Governor Tony Evers (D-WI) Letter of Consent

Governor Janet Mills (D-ME) Letter of Consent

Governor Kevin Stitt (R-OK) Letter of Consent

Governor Pete Ricketts (R-NE) Anticipated Consent via Spokesman

Governor Steve Sisolak (D-NV) Letter of Consent

Governor Kristi Noem (R-SD) Article on Consent

Governor Bashear (D-KY) anticipated consent

Governor Justice (R-WV) Letter of Consent & Press Release

Governor Edwards (D-LA) Letter of Consent and article

Governor Hutchinson (R-AR) Letter of Consent and article

Governor Newsom (D-CA) Letter of Consent

Governor Parson (R-MO) Letter of Consent and article

Governor Little (R-ID) Letters of Consent by county and article

Governor Larry Hogan (R-MD) Letter of Consent and article

Governor Dunleavy (R-AK) Article on Consent

Governor Cuomo (D-NY)

Governor Phil Scott (R-VT) Article on Consent

Local Authorities who have given consent*

*Non-exhaustive list

Mayor Ben Walsh – Syracuse, NY

Mayor Jacob Frey Tweet of consent– Minneapolis, MN

Mayor Andrew Ginther– Columbus, OH

Mayor Steve Schewel and Letter of Consent – Durham, NC

Mayor Jenny Durkan Letter of Consent – Seattle, WA

Mayor Nancy Vaughan Letter of Consent – Greensboro, NC

Alexandria City Council resolution, statement from Mayor Justin Wilson – Alexandria, VA

Durham County, NC Board of Commissioners – Letter of Consent

Knoxville City Council Consent – Knoxville, TN

Fort Worth Mayor Betsy Price (R) letter to Governor Abbott

Erie County, NY – Letter of Consent

Mayor Byron Brown Letter of Consent – Buffalo, NY

Mayor Patti Garrett Letter of Consent – Decatur, GA

Chatham County, GA – Letter of Consent

Polk County, IA – Letter of Consent

Warren County, KY – Letter of Consent

Daviess County, KY – Letter of Consent

Mayor Nicole LaChapelle Letter of Consent – Easthampton, MA

Mayor Alex B. Morse Letter of Consent – Holyoke, MA

Mayor David Narkewicz Letter of Consent – Northampton, MA

Mayor Kimberly Driscoll Letter of Consent – Salem, MA

Mayor John Engen Letter of Consent – Missoula, MT

Mayor David Engen Letter of Consent – Grand Forks, ND

Mayor Frank G. Jackson Letter of Consent – Cleveland, OH

Mayor Michael P. Summers Letter of Consent – Lakewood, OH

Mayor Timothy J. DeGeeter Letter of Consent – Parma, OH

Mayor Nan Whaley Letter of Consent – Dayton, OH

Erie County Pennsylvania – Letter of Consent

Mayor Jorge O. Elorza Letter of Consent – Providence, RI

Bexar County, TX – Letter of Consent

Mayor Ron Nirenberg Letter of Consent – San Antonio, TX

Mayor Levar Stoney Letter of Consent – Richmond, VA

Kalamazoo County, MI – Letter of Consent

Kandiyohi County, MN – Letter of Consent

Pima County, AZ Letter of Consent – Pima County, AZ

Mayor Kim Maggard Letter of Consent – Whitehall, OH

Mayor Betsy Price Letter of Consent – Fort Worth, TX

Mayor John Dailey Letter of Consent and Proclamation – Tallahassee, FL

Burleigh County, ND – Commission Vote

Franklin County, OH – Final Resolution / Commission and Article

Mayor of Dallas Letter of Consent – Dallas, TX

Mayor Thomas McNamara Letter of Consent – Rockford, IL

Winnebago County, IL – Letter of Consent

DuPage County, IL – Letter of Consent

Mayor Jim Bouley Letter of Consent – Concord, NH

Mayor Kate Gallego Letter of Consent – Phoenix, AZ

Mayor Jonathan Rothschild Letter of Consent – Tucson, AZ

Mayor Edward Terry Letter of Consent – Clarkston, GA

Mayor William Reichelt Letter of Consent – West Springfield, MA

City of Ypsilanti, MI – Council Resolution and Consent

Olmsted County, MN Letter of Consent

Mayor Lyda Krewson Letter of Consent – St. Louis, MO

Mayor Mary-Ann Baldwin Letter of Consent – Raleigh, NC

Cass County, ND – Letter of Consent

Mayor Alvin Brandl Letter of Consent – Madison, NE

Mayor Jim Donchess Letter of Consent – Nashua, NH

Mayor Joyce Craig Letter of Consent – Manchester, NH

Hamilton County, OH – Letter of Consent

Montgomery County, OH – Letter of Consent

Mayor Lucy Vinis Letter of Consent – Eugene, OR

Mayor Christine Lundberg Letter of Consent – Springfield, OR

Mayor Wayne Evans Letter of Consent – Scranton, PA

Mayor Andy Berke Letter of Consent – Chattanooga, TN

Cache County, UT – Letter of Consent

Salt Lake County, UT – Letter of Consent

Weber County, UT – Letter of Consent

Fairfax County, VA – Letter of Consent

Mayor Sherman Lea, Sr. Letter of Consent – Roanoke, VA

Mayor Kelli Linville Letter of Consent – Bellingham, WA

Pierce County, WA – Letter of Consent

Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway Letter of Consent – Madison, WI

Mayor Fischer Letter of Consent – Louisville, KY

Mayor Kenneth Miyagishima Letter of Consent – Las Cruces, NM

Mayor William Peduto Letter of Consent – Pittsburgh, PA

Mayor Mark Behnke Letter of Consent – Battle Creek, MI

Macomb County, MI – Letter of Consent

Washtenaw County, MI – Consent Resolution

Wayne County, MI – Letter of Consent

Oakland County, MI – Letter of Consent

Mayor David Berger Letter of Consent – Lima, OH

Mayor Martin Walsh Letter of Consent – Boston, MA

Mayor Joe Hogsett Letter of Consent – Indianapolis, IN

Dallas County, TX – Letter of Consent

Ingham County, MI – Consent Resolution

Mayor Stephen C.N. Kepley Letter of Consent – Kentwood, MI

Las Vegas, NV – Article on Consent

Henderson, NV – Article on Consent

Reno, NV – Article on Consent

Wake County NC – Letter of Consent

Buncombe County NC – Letter of Consent

Onondaga County, NY – Article on Consent

Cook County, MN – Article on Consent

Cumberland County, PA – Article on Consent

Ramsey County, MN – Article on Consent

Minnehaha County, SD – Article on Consent

Boulder County, CO – Article on Consent

Grand Traverse County, MI – Article on Consent

New Castle County, DE – Article on Consent

Utah County, UT – Article on Consent

Otter Tail County, MN – Article on Consent

Twin Falls County, ID – Article on Consent

Spokane County, WA – Article on Consent

Dane County, WI – Press Release on Consent

Boone County, MO – Article on Consent

Mecklenburg County, NC – Article on Consent

Ann Corcoran of RRW blog notes:

I continue to argue that these nine contractors are the heart of America’s Open Borders movement and thus there can never be long-lasting reform of US immigration policy when these nine un-elected phony non-profits are paid by the taxpayers to work as community organizers pushing an open borders agenda.

Church World Service (CWS)

Ethiopian Community Development Council (ECDC) (secular)

Episcopal Migration Ministries (EMM)

Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS)

International Rescue Committee (IRC) (secular)

US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI) (secular)

Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services (LIRS)

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB)

World Relief Corporation (WR)

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dads, Listen Up: Session 2: Women Community Leaders

This is a special episode based on a webinar that we first presented on September 7th on the Fathering Together Facebook Page for another conversation on the ways fathers can empower and encourage their daughters to be community leaders! We had 3 amazing panelists doing great things in their community to forge a more equitable future. Barbara Barreno-Paschall is a Commissioner with the State of Illinois Human Rights Commission following her appointment by Governor JB Pritzker in 2019. Prior to her appointment, Barbara was a Senior Staff Attorney with Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights. She also was an Associate at Sidley Austin LLP. At Sidley, Barbara twice received the firm’s Thomas H. Morsch Award for Pro Bono Achievement for her successful representation of immigrants seeking asylum. Barbara is a Board member of the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference and Harvard Alumni for Global Women’s Empowerment and is a member of the Harris Alumni Council. In 2018, Barbara was elected as a Community Representative on the Kenwood Academy High School Local School Council and is an Emerging Leader with the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. Barbara is a graduate of Harvard College, Vanderbilt Law School, and the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy. Ruth Lopez-McCarthy is a managing attorney with the Legal Protection Fund Project. Ruth holds over 17 years of experience in the immigration movement both locally and nationally. After working as an organizer in Chicago, Ruth obtained her J.D. from Chicago- Kent College of Law. Ruth served as the deputy field director with the Reform Immigration FOR America campaign, the coalition coordinator for the Northern Borders Coalition, and as the deputy legislative associate/legislative liaison for Field for the Alliance for Citizenship campaign in Washington, D.C. She joined the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights as the comprehensive immigration reform implementation director in 2013 where she built the IL is READY Campaign in preparation for administrative relief. Ruth worked as a consultant for immigration advocacy organizations coordinating immigrant focused programs across the United States and Mexico. At NIJC, Ruth leads the City of Chicago funded initiative, the Legal Protection Fund, aimed at educating community and providing immediate legal information, screenings, consultations, and representation to individuals who may be at risk for deportation or in need of trustworthy immigration representation. Ruth speaks Spanish and is licensed to practice law in Illinois. Kady McFadden is Deputy Director of the Sierra Club Illinois Chapter. In this role, Kady manages organizing and conservation staff in order to build strong advocacy campaigns for clean energy, clean water, and open space protection. Kady also runs the Sierra Club Illinois PAC to elect environmental champions to state, local and federal office. She is an alumna of Washington University in St Louis and University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.

If you've enjoyed today's episode of the Dads With Daughters podcast we invite you to check out the Fatherhood Insider. The Fatherhood Insider is the essential resource for any dad that wants to be the best dad that he can be. We know that no child comes with an instruction manual and most are figuring it out as they go along. The Fatherhood Insider is full of valuable resources and information that will up your game on fatherhood. Through our extensive course library, interactive forum, step-by-step roadmaps and more you will engage and learn with experts but more importantly with dads like you. So check it out today!

Check out this new Dads With Daughters episode!

0 notes

Text

African Americans forged free lives in Civil War refugee camps

Refugee camps for African Americans during the Civil War show how they built a future from the ashes of slavery, a historian explains.

More than 300 refugee camps sprang up during the war with more than 800,000 African Americans passing through them at some point. Most residents were slaves or ex-slaves fleeing the clutches of their enslavers and the Confederate army, estimates Abigail Cooper, an assistant professor of history at Brandeis University who has a joint appointment in African and African American Studies.

Others came to find family members who had been sold to different slave owners.

“By looking at this in-between moment when slavery’s end was possible but not assured, we can look to how African Americans made and lived out freedom on their own terms,” Cooper says.

“African Americans gathered to forge a monumental psychological transformation from knowing America as their enslaver to envisioning America as their home.”

Cooper wrote about the camps in her 2015 PhD dissertation and more recently in the Journal of African American History.

Mary Armstrong’s story

In 1863, newly freed from bondage and living in St. Louis, 17-year-old Mary Armstrong did the unthinkable—she journeyed to the slave-holding South.

Armstrong, one of more than 2,000 former slaves who told their stories to the New Deal’s Federal Writers’ Project in the late 1930s, had been separated from her parents as a child when they were sold to other owners.

Mary Armstrong in 1937. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Armstrong learned through the grapevine that her kin might be in Texas so, as she says in her interview, “away I goin’ to find my mamma.”

With the Civil War raging, she set out with two baskets full of food and clothing and a small amount of money, traveling more than 1,000 miles by boat and then stagecoach to Texas.

In Austin, she was captured and put up for bid, securing her freedom only at the last minute by showing her papers to the Texas official in charge of the auction.

Armstrong eventually found her mother in the city of Wharton, some 150 miles south of Austin, at a refugee camp for African Americans.

Armstrong described the reunion: “Lawd me, talk ’bout cryin’ and singin’ and cryin’ some more, we sure done it.”

Armstrong later went on to become a nurse in the Houston area, saving numerous lives in the yellow fever epidemic of 1875.

What were the refugee camps like?

A camp could hold anywhere from a few hundred to several thousand people, most of them living in barracks or fabric tents.

The Union set up some of the camps, the first two in 1861 along the coast in Virginia and South Carolina, followed by others in Kentucky and Tennessee and along the Mississippi River from New Orleans to St. Louis, Missouri. Officially, they were called “contraband camps,” because freed people were considered property confiscated from the South.

Another group of camps located mainly in the South behind Confederate lines was created ad hoc by blacks themselves. (Cooper has posted an interactive map of the locations of the camps).

At a camp in Hampton, Virginia called Slabtown and later the Grand Contraband Camp, African Americans built houses so sturdy the Union later appropriated them to house troops.

There were also four black schools in the camp, one of which became the future site of Hampton University, one of the premier historically black educational institutions in the country.

Life as a refugee

Conditions in many of the camps were squalid and disease was common. Black refugees lived in constant fear and terror of raids from southern whites. At one point, the Confederate army plundered and burned Slabtown to the ground.

Whites also lived in the camps, most of them seeking shelter from the war. They were treated differently from blacks. A rations list Cooper discovered for a camp in New Bern, North Carolina, shows that 1,800 whites received 76½ barrels of flour over the course of three months in 1862-63. During the same period, the 7,500 blacks there received 19 barrels.

But despite the hardships and oppression, Cooper says that the camps offered the formerly enslaved people their first opportunity to savor freedom, reunite as families and lay the groundwork for a new society and religion.

Fugitive African Americans fording the Rappahannock River in Virginia, August 1862. (Credit: Library of Congress)

Never before had so many former slaves of so many different cultures gathered in such concentrations with the possibility of freedom near. There was an exchange of ideas, traditions, and rituals that fostered literacy and education and led to religious revivals.

Camp inhabitants compared their plight to the Israelites in the desert in the book of Exodus, freed from slavery but not yet delivered to their new country.

“More than anything, we should make careful study of the remarkable amount of resourcefulness it took for refugee slaves to gather their families into Union lines, to build information networks, to pray, eat, hoe, sing, give birth, share living space, take care of each other’s children, to imagine home while in a place outside a ‘household,'” Cooper wrote in her dissertation.

Over and over again, the residents in the camps talk about the importance of shoes. On plantations, masters kept slaves’ footwear locked up at night so they couldn’t escape. A good pair of shoes was necessary to make the difficult trek, sometimes through forests and rocky terrain, to the camps. Without shoes, you could more easily be picked out in a crowd as an escaped slave, and kidnappers lurked, attempting to sell people back into slavery.

Refugees carried money and protective charms in their shoes. They also fashioned footwear from plantain leaves. Their pungent smell was useful in throwing off the scent of the hounds patrollers and former owners used to track them down.

A common song went, “I got shoes, you got shoes, All o’ God’s chillun got shoes. When I get to heav’n I’m goin’ to put on my shoes.”

Religious freedom

Cooper says folk religion informed black visions for their new society. Emancipation as a divine reckoning was the lens through which they defined liberty. Freedom meant the right to practice their religion.

It was through refugee camps, Cooper wrote in her thesis, that black refugees “sought to transform the Egypt of the Slave South into a New Canaan.”

“Their great soul-hungering desire was freedom.”

Critical to this was the ability to read the Bible for themselves for the first time in their lives. Southern slaveholders had used selected passages to justify slavery.

African Americans in the camps now formed Bible study groups and found scripture to support their liberation. The Jubilee in the Old Testament marks the day when Hebrew slaves would be freed from bondage in Egypt. African Americans created their own Emancipation Jubilee on January 1, 1863, the day the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect.

Another jubilee was celebrated in 1865 with the passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery. And a grand jubilee celebrated annually well into the 20th century as “Juneteenth” commemorated June 19th, 1865, when word of southern surrender reached black camps in Texas.

Grieving was an all too common experience in the camps, but black refugees in the camps turned mourning rituals into opportunities for empowerment. “There was all this death going on around them,” Cooper says, “but they were dying in freedom, and that meant something. Many saw going back to slavery as even worse.”

One woman who had three of her children die in a camp expressed relief because she knew where her children were buried. If they had been sold away from her, she would not know whether they lived or died or how to mourn them.

In what were called “watch meetings” or “watch-night meetings” or “setting up,” adults at all-night funerals danced, clapped, prayed, and experienced ecstatic visions.

“The slaves would sing, pray, and relate experiences all night long,” former slave Mary Gladdy says. “Their great soul-hungering desire was freedom.”

Jennie Boyd’s story

Jennie Boyd’s contractions had already started when her family realized they had to move on. She had been hiding out in Springfield, Missouri, but now her owners were close to finding her. Meanwhile, the Wilson’s Creek battle on August 10, 1861, raged nearby, making it dangerous to stay any longer.

The Boyds headed west toward Arizona accompanied at times by a retreating regiment of the Confederate army. Jennie told her 4-year-old daughter Emma to stay close and not go near anything that was smoking in case it was an explosive.

Jennie was in full labor by the time the family arrived in Bethphage, some 80 miles to the southwest. It was little more than a camping ground in the wilderness, but it was here that Jennie gave birth.

The baby was born “sick and delicate,” Emma later recalled, but she survived. Jennie honored the camp by naming her newborn after it—Priscilla Bethpage.

The Boyds continued west but soon crossed paths with a band of Union soldiers who offered to take them back to Springfield where one of Jennie’s other daughters remained enslaved. The family found refuge there in the home of a white Union sympathizer.

When the war ended in 1865, the family moved to a black settlement known as “Dink-town” in central Arkansas. Emma says freed people there “dug holes in the ground, made dug-outs, brush houses, with a piece of board here and there, whenever they could find one, until finally they had a little village.”

They were staking their claims on making homes in freedom as best they could. It was here, Emma says, that “they sang and prayed and rejoiced.”

Views of freedom

Cooper’s research points to a new way of understanding the political emancipation of African Americans. Often cast in terms of African Americans winning the right to vote or running candidates for office, Cooper believes there were other, equally fundamental ways that blacks viewed freedom.

Freedom had a spiritual dimension that fueled a radical transformation of what it meant to be a black American.

“W.E.B. DuBois says it almost a century ago: ‘To most of the four million black folk emancipated by the Civil War, God was real,'” Cooper says.

“The postwar period will present new forms of oppression and exploitation, but black Americans will still celebrate emancipation and how they made it. This will feed their ongoing freedom struggle and their resilience,” she says.

Source: Brandeis University

The post African Americans forged free lives in Civil War refugee camps appeared first on Futurity.

African Americans forged free lives in Civil War refugee camps published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes