#Raj Chetty

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Study of Elite College Admissions Data Suggests Being Very Rich Is Its Own Qualification

By Aatish Bhatia, Claire Cain Miller and Josh Katz July 24, 2023 (full text under the cut)

Elite colleges have long been filled with the children of the richest families: At Ivy League schools, one in six students has parents in the top 1 percent.

A large new study, released Monday, shows that it has not been because these children had more impressive grades on average or took harder classes. They tended to have higher SAT scores and finely honed résumés, and applied at a higher rate — but they were overrepresented even after accounting for those things. For applicants with the same SAT or ACT score, children from families in the top 1 percent were 34 percent more likely to be admitted than the average applicant, and those from the top 0.1 percent were more than twice as likely to get in.

The study — by Opportunity Insights, a group of economists based at Harvard who study inequality — quantifies for the first time the extent to which being very rich is its own qualification in selective college admissions.

The analysis is based on federal records of college attendance and parental income taxes for nearly all college students from 1999 to 2015, and standardized test scores from 2001 to 2015. It focuses on the eight Ivy League universities, as well as Stanford, Duke, M.I.T. and the University of Chicago. It adds an extraordinary new data set: the detailed, anonymized internal admissions assessments of at least three of the 12 colleges, covering half a million applicants. (The researchers did not name the colleges that shared data or specify how many did because they promised them anonymity.)

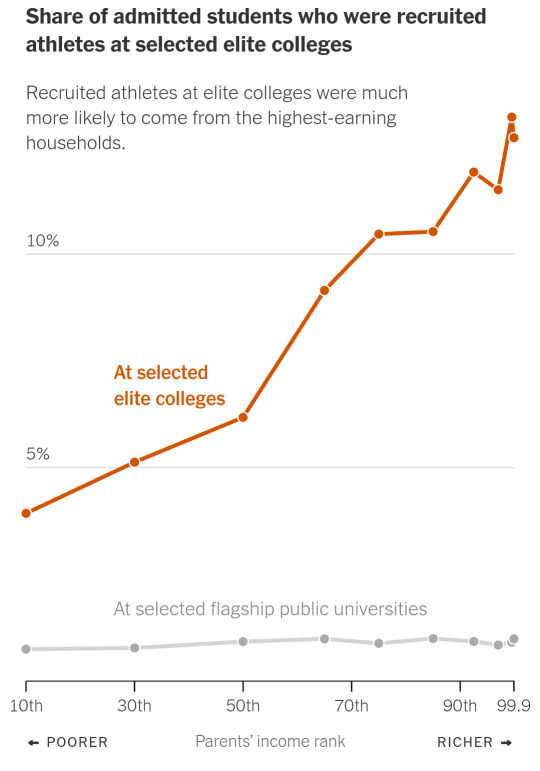

The new data shows that among students with the same test scores, the colleges gave preference to the children of alumni and to recruited athletes, and gave children from private schools higher nonacademic ratings. The result is the clearest picture yet of how America’s elite colleges perpetuate the intergenerational transfer of wealth and opportunity.

“What I conclude from this study is the Ivy League doesn’t have low-income students because it doesn’t want low-income students,” said Susan Dynarski, an economist at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, who has reviewed the data and was not involved in the study.

In effect, the study shows, these policies amounted to affirmative action for the children of the 1 percent, whose parents earn more than $611,000 a year. It comes as colleges are being forced to rethink their admissions processes after the Supreme Court ruling that race-based affirmative action is unconstitutional.

“Are these highly selective private colleges in America taking kids from very high-income, influential families and basically channeling them to remain at the top in the next generation?” said Raj Chetty, an economist at Harvard who directs Opportunity Insights, and an author of the paper with John N. Friedman of Brown and David J. Deming of Harvard. “Flipping that question on its head, could we potentially diversify who’s in a position of leadership in our society by changing who is admitted?”

Representatives from several of the colleges said that income diversity was an urgent priority, and that they had taken significant steps since 2015, when the data in the study ends, to admit lower-income and first-generation students. These include making tuition free for families earning under a certain amount; giving only grants, not loans, in financial aid; and actively recruiting students from disadvantaged high schools.

“We believe that talent exists in every sector of the American income distribution,” said Christopher L. Eisgruber, the president of Princeton. “I am proud of what we have done to increase socioeconomic diversity at Princeton, but I also believe that we need to do more — and we will do more.”

Affirmative action for the rich

In a concurring opinion in the affirmative action case, Justice Neil Gorsuch addressed the practice of favoring the children of alumni and donors, which is also the subject of a new case. “While race-neutral on their face, too, these preferences undoubtedly benefit white and wealthy applicants the most,” he wrote.

The new paper did not include admissions rates by race because previous research had done so, the researchers said. They found that racial differences were not driving the results. When looking only at applicants of one race, for example, those from the highest-income families still had an advantage. Yet the top 1 percent is overwhelmingly white. Some analysts have proposed diversifying by class as a way to achieve more racial diversity without affirmative action.

The new data showed that other selective private colleges, like Northwestern, N.Y.U. and Notre Dame, had a similarly disproportionate share of children from rich families. Public flagship universities were much more equitable. At places like the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Virginia, applicants with high-income parents were no more likely to be admitted than lower-income applicants with comparable scores.

Less than 1 percent of American college students attend the 12 elite colleges. But the group plays an outsize role in American society: 12 percent of Fortune 500 chief executives and a quarter of U.S. senators attended. So did 13 percent of the top 0.1 percent of earners. The focus on these colleges is warranted, the researchers say, because they provide paths to power and influence — and diversifying who attends has the potential to change who makes decisions in America.

The researchers did a novel analysis to measure whether attending one of these colleges causes success later in life. They compared students who were wait-listed and got in, with those who didn’t and attended another college instead. Consistent with previous research, they found that attending an Ivy instead of one of the top nine public flagships did not meaningfully increase graduates’ income, on average. However, it did increase a student’s predicted chance of earning in the top 1 percent to 19 percent, from 12 percent.

For outcomes other than earnings, the effect was even larger — it nearly doubled the estimated chance of attending a top graduate school, and tripled the estimated chance of working at firms that are considered prestigious, like national news organizations and research hospitals.

“Sure, it’s a tiny slice of schools,” said Professor Dynarski, who has studied college admissions and worked with the University of Michigan on increasing the attendance of low-income students, and has occasionally contributed to The New York Times. “But having representation is important, and this shows how much of a difference the Ivies make: The political elite, the economic elite, the intellectual elite are coming out of these schools.”

The missing middle class

The advantage to rich applicants varied by college, the study found: At Dartmouth, students from the top 0.1 percent were five times as likely to attend as the average applicant with the same test score, while at M.I.T. they were no more likely to attend. (The fact that children from higher-income families tend to have higher standardized test scores and are likelier to receive private coaching suggests that the study may actually underestimate their admissions advantage.)

An applicant with a high test score from a family earning less than $68,000 a year was also likelier than the average applicant to get in, though there were fewer applicants like this.

Children from middle- and upper-middle-class families — including those at public high schools in high-income neighborhoods — applied in large numbers. But they were, on an individual basis, less likely to be admitted than the richest or, to a lesser extent, poorest students with the same test scores. In that sense, the data confirms the feeling among many merely affluent parents that getting their children into elite colleges is increasingly difficult.

“We had these very skewed distributions of a whole lot of Pell kids and a whole lot of no-need kids, and the middle went missing,” said an Ivy League dean of admissions, who has seen the new data and spoke anonymously in order to talk openly about the process. “You’re not going to win a P.R. battle by saying you have X number of families making over $200,000 that qualify for financial aid.”

The researchers could see, for nearly all college students in the United States from 1999 to 2015, where they applied and attended, their SAT or ACT scores and whether they received a Pell grant for low-income students. They could also see their parents’ income tax records, which enabled them to analyze attendance by earnings in more detail than any previous research. They conducted the analysis using anonymized data.

For the several elite colleges that also shared internal admissions data, they could see other aspects of students’ applications between 2001 and 2015, including how admissions offices rated them. They focused their analysis on the most recent years, 2011 to 2015.

Though they had this data for a minority of the dozen top colleges, the researchers said they thought it was representative of the other colleges in the group (with the exception of M.I.T.). The other colleges admitted more students from high-income families, showed preferences for legacies and recruited athletes, and described similar admissions practices in conversations with the researchers, they said.

“Nobody has this kind of data; it’s completely unheard-of,” said Michael Bastedo, a professor at the University of Michigan’s School of Education, who has done prominent research on college admissions. “I think it’s really important to good faith efforts for reforming the system to start by being able to look honestly and candidly at the data.”

How the richest students benefit

Before this study, it was clear that colleges enrolled more rich students, but it was not known whether it was just because more applied. The new study showed that’s part of it: One-third of the difference in attendance rates was because middle-class students were somewhat less likely to apply or matriculate. But the bigger factor was that these colleges were more likely to accept the richest applicants.

Legacy admissions

The largest advantage for the 1 percent was the preference for legacies. The study showed — for the first time at this scale — that legacies were more qualified overall than the average applicant. But even when comparing applicants who were similar in every other way, legacies still had an advantage.

When high-income applicants applied to the college their parents attended, they were accepted at much higher rates than other applicants with similar qualifications — but at the other top-dozen colleges, they were no more likely to get in.

“This is not a sideshow, not just a symbolic issue,” Professor Bastedo said of the finding.

Athletes

One in eight admitted students from the top 1 percent was a recruited athlete. For the bottom 60 percent, that figure was one in 20. That’s largely because children from rich families are more likely to play sports, especially more exclusive sports played at certain colleges, like rowing and fencing. The study estimated that athletes were admitted at four times the rate of nonathletes with the same qualifications.

“There’s a common misperception that it’s about basketball and football and low-income kids making their way into selective colleges,” Professor Bastedo said. “But the enrollment leaders know athletes tend to be wealthier, so it’s a win-win.”

Nonacademic ratings

There was a third factor driving the preference for the richest applicants. The colleges in the study generally give applicants numerical scores for academic achievement and for more subjective nonacademic virtues, like extracurricular activities, volunteering and personality traits. Students from the top 1 percent with the same test scores did not have higher academic ratings. But they had significantly higher nonacademic ratings.

At one of the colleges that shared admissions data, students from the top 0.1 percent were 1.5 times as likely to have high nonacademic ratings as those from the middle class. The researchers said that, accounting for differences in the way each school assesses nonacademic credentials, they found similar patterns at the other colleges that shared data.

The biggest contributor was that admissions committees gave higher scores to students from private, nonreligious high schools. They were twice as likely to be admitted as similar students — those with the same SAT scores, race, gender and parental income — from public schools in high-income neighborhoods. A major factor was recommendations from guidance counselors and teachers at private high schools.

“Parents rattle off that a kid got in because he was first chair in the orchestra, ran track,” said John Morganelli Jr., a former director of admissions at Cornell and founder of Ivy League Admissions, where he advises high school students on applying to college. “They never say what really happens: Did the guidance counselor advocate on that kid’s behalf?”

Recommendation letters from private school counselors are notoriously flowery, he said, and the counselors call admissions officers about certain students.

“This is how the feeder schools get created,” he said. “Nobody’s calling on behalf of a middle- or lower-income student. Most of the public school counselors don’t even know these calls exist.”

The end of need-blind admissions?

Overall, the study suggests, if elite colleges had done away with the preferences for legacies, athletes and private school students, the children of the top 1 percent would have made up 10 percent of a class, down from 16 percent in the years of the study.

Legacy students, athletes and private school students do no better after college, in terms of earnings or reaching a top graduate school or firm, it found. In fact, they generally do somewhat worse.

The dean of admissions who spoke anonymously said change was easier said than done: “I would say there’s much more commitment to this than may be obvious. It’s just the solution is really complicated, and if we could have done it, we would have.”

For example, it’s not feasible to choose athletes from across the income spectrum if many college sports are played almost entirely by children from high-earning families. Legacies are perhaps the most complicated, the admissions dean said, because they tend to be highly qualified and their admission is important for maintaining strong ties with alumni.

Ending that preference, the person said, “is not an easy decision to make, given the alumni response, especially if you’re not in immediate concurrence with the rest of the Ivies.” (Though children of very large donors also get special consideration by admissions offices, they were not included in the analysis because there are relatively few of them.)

People involved in admissions say that achieving more economic diversity would be difficult without doing something else: ending need-blind admissions, the practice that prevents admissions officers from seeing families’ financial information so their ability to pay is not a factor. Some colleges are already doing what they call “need-affirmative admissions,” for the purpose of selecting more students from the low end of the income spectrum, though they often don’t publicly acknowledge it for fear of blowback.

There is a tool, Landscape from the College Board, to help determine if an applicant grew up in a neighborhood with significant privilege or adversity. But these colleges have no knowledge of parents’ income if students don’t apply for financial aid.

Ivy League colleges and their peers have recently made significant efforts to recruit more low-income students and subsidize tuition. Several now make attendance entirely free for families below a certain income — $100,000 at Stanford and Princeton, $85,000 at Harvard, and $60,000 at Brown.

At Princeton, one-fifth of students are now from low-income families, and one-fourth receive a full ride. It has recently reinstated a transfer program to recruit low-income and community college students. At Harvard, one-fourth of this fall’s freshman class is from families with incomes less than $85,000, who will pay nothing. The majority of freshmen will receive some amount of aid.

Dartmouth just raised $500 million to expand financial aid: “While we respect the work of Harvard’s Opportunity Insights, we believe our commitment to these investments and our admissions policies since 2015 tells an important story about the socioeconomic diversity among Dartmouth students,” said Jana Barnello, a spokeswoman.

Public flagships do admissions differently, in a way that ends up benefiting rich students less. The University of California schools forbid giving preference to legacies or donors, and some, like U.C.L.A., do not consider letters of recommendation. The application asks for family income, and colleges get detailed information about California high schools. Application readers are trained to consider students’ circumstances, like whether they worked to support their families in high school, as “evidence of maturity, determination and insight.”

The University of California system also partners with schools in the state, from pre-K through community college, to support students who face barriers. There’s a robust program for transfer students from California community colleges; at U.C.L.A., half are from low-income backgrounds.

M.I.T., which stands out among elite private schools as displaying almost no preference for rich students, has never given a preference to legacy applicants, said its dean of admissions, Stuart Schmill. It does recruit athletes, but they do not receive any preference or go through a separate admissions process (as much as it may frustrate coaches, he said).

“I think the most important thing here is talent is distributed equally but opportunity is not, and our admissions process is designed to account for the different opportunities students have based on their income,” he said. “It’s really incumbent upon our process to tease out the difference between talent and privilege.”

Source: Raj Chetty, David J. Deming and John N. Friedman, “Diversifying Society’s Leaders? The Determinants and Causal Effects of Admission to Highly Selective Private Colleges”

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tests are not entirely objective, of course. Well-off students can pay for test prep classes and can pay to take the tests multiple times. Yet the evidence suggests that these advantages cause a very small part of the gaps. Consider that other measures of learning — like the NAEP, a test that elementary and middle school students take nationwide — show similarly large racial and economic gaps. The federal government describes the NAEP as “the nation’s report card,” while education researchers consider it a rigorous measure of K-12 learning. And even though students do not take NAEP test prep classes, its demographic gaps look remarkably similar to those of the ACT and SAT. This similarity “is another piece of evidence that the SAT is picking up fundamentals,” said Raj Chetty, a Harvard economics professor who conducted the recent Ivy Plus study with Friedman and David Deming. “It strengthens the argument that the disparities in SAT scores are a symptom, not a cause, of inequality in the U.S.,” Chetty said. To put it another way, the existence of racial and economic gaps in SAT and ACT scores doesn’t prove that the tests are biased. After all, most measures of life in America — on income, life expectancy, homeownership and more — show gaps. No wonder: Our society suffers from huge inequities. The problem isn’t generally with the statistics, however. The relatively high Black poverty rate is not a sign that the statistic is biased. Nor would scrapping the statistic alleviate poverty.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Using data on 57 million children born between 1978 and 1992, Raj Chetty of Harvard and co-authors find that while the white-Black race gap narrowed since the 1990s, the class gap widened. The gap in average adult household income between white children growing up in low-income households and those growing up in high-income households rose from $17,720 to $20,950 between the 1978 and 1992 birth cohorts. In contrast, the income gap between Black and white children who grew up in low-income households shrank by 28%, from $20,810 to $14,910. These shifts are largely due to declining employment rates among low-income white parents compared to both low-income Black parents and high-income white parents. The strong correlation between changes in parental employment levels and children’s outcomes suggests that improving community-level conditions can quickly improve economic mobility for the next generation.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Mahzarin Banaji and Frank Dobbin

Published: Sep 17, 2023

At least 30 states are considering legislation to defund DEI initiatives in public universities and state agencies. At the same time, conservative activists, emboldened by the Supreme Court’s ruling against affirmative action in college admissions, are suing companies to stop DEI initiatives. These challenges come on the heels of the growth of corporate DEI programs after the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020.

Meanwhile, advocates for DEI—which stands for diversity, equity and inclusion—have bemoaned the fact that after decades of diversity training, many university faculties, state agencies and corporations have made little progress on diversifying the workforce.

Are the right and the left on the same page here—is diversity training a hopeless cause?

We are a psychologist and a sociologist who have been studying bias and organizational diversity programs, respectively, for decades. The research makes it clear that Americans desperately need education about bias, because even people who value fairness and equality hold biases—without being aware of it. They need to understand that bias operates systemically and must be addressed at the individual, institutional and societal levels.

Education offered on these matters is very much in the national spirit. As Alexis de Tocqueville noted in “Democracy in America” in 1835: “The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.”

What research shows

The social and behavioral sciences have developed strong evidence about conscious prejudice and implicit bias. Three lines of research, together, are pertinent. One provides good news. As our colleague Larry Bobo has documented, conscious unabashed racial prejudice has fallen consistently since the 1960s. White Americans today largely believe in racial equality.

This isn’t to say that explicit expressions of prejudice have evaporated; in fact they pop up with surprising regularity. The pandemic witnessed precipitous increases in anti-Asian hatred, and according to the Anti-Defamation League, instances of antisemitism are at a record high.

A second line of research shows that less conscious, or implicit, bias has declined more slowly. Bias against some groups has barely budged. If only explicit values and biases drove discrimination, unfair treatment of, say, Black workers would be low. But implicit bias taints employer behavior and decisions. Our colleague Mandy Palais and collaborators find, for instance, that implicit racial bias in grocery-store managers still influences worker performance.

A third line of research uses audit studies, in which matched Black and white people, for instance, apply to the same job. Who gets called in for an interview, or hired? Scores of studies show discrimination by race, ethnicity, gender and disability. These studies show, among other things, that white applicants are about 50% more likely than identical Black applicants to be called back for an interview or offered a job. Other audit studies show discrimination in real-world access to financial resources, healthcare and treatment by the law and law enforcement.

Research by Lincoln Quillian and colleagues compares the results of audit studies over time, finding that discrimination against Black job applicants is virtually unchanged from a generation ago. And the economist Raj Chetty and colleagues not only show a shocking drop in American upward mobility over time, but also show that in regions with high levels of implicit bias, Black Americans are less likely than white Americans to move up the economic ladder.

Research by Lincoln Quillian and colleagues compares the results of audit studies over time, finding that discrimination against Black job applicants is virtually unchanged from a generation ago. And the economist Raj Chetty and colleagues not only show a shocking drop in American upward mobility over time, but also show that in regions with high levels of implicit bias, Black Americans are less likely than white Americans to move up the economic ladder.

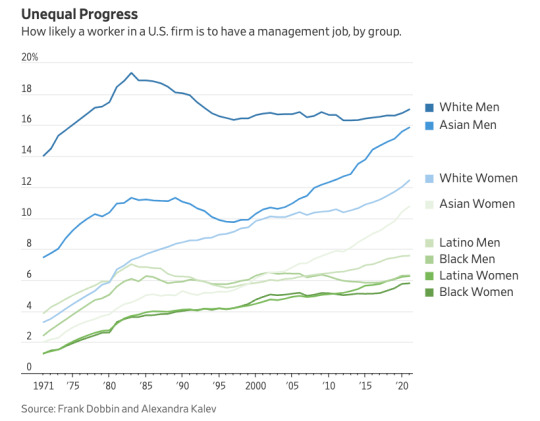

Research from one of us, Frank Dobbin (with Alexandra Kalev), meanwhile, shows how likely a worker in a U.S. firm is to have a management job, by group. Women and people of color see increases until the mid-1980s. But progress stalls for Black and Hispanic workers after that. Men from those groups make no progress between then and 2021, and women make almost no progress. We clearly have more work to do to equalize opportunity.

Falling short

It’s not hard to conclude from all these studies that we are not the land of opportunity for everyone we claim to be. An enlightened society should see that education about the prevalence of discrimination is imperative. In fact, it would be downright dumb not to educate people.

But, as Dobbin and Kalev have shown, the typical DEI training doesn’t educate people about bias and may even do harm.

Most training programs fall short on two fronts. First, they use implicit-bias education to shame trainees for holding stereotypes. Trainers play gotcha, sending trainees to take an online test co-developed by one of us, Mahzarin Banaji, for education and research. Instead of training people about research that finds that bias is pervasive, trainers use the test to prove to trainees that they are morally flawed. People leave feeling guilty for holding biases that conflict with American values.

“Gotcha” isn’t going to win people over. The approach is disrespectful, and misses the main takeaway from implicit bias research: Everyone holds biases they don’t control as a consequence of a lifetime of exposure to societal inequality, the media and the arts. Trainers should introduce these ideas with humility, for trainers themselves can’t help but hold these very biases. They could easily educate themselves about the implicit bias research with resources at outsmartingimplicitbias.org.

The second problem with most trainings is that they seek to solve the problem of bias by invoking the law to scare people about the risk of letting bias go unchecked. Trainers recount stories of big companies brought to their heels by discrimination suits. They detail rigid do’s and don’ts for hiring, disciplining and firing people. They require trainees to pass tests on what the law forbids. All of this makes it clear that the CEO approved the training solely to avoid litigation. Trainees leave scared that they will be punished for a simple mistake that may land their company in court.

Trainings with this one-two punch—you are biased and the law will get you—backfire. The research shows that this kind of training leads to reductions in women and people of color in management.

Why would diversity training actually make things worse? Making people feel ashamed can lead them to reject the message. Thus people often leave diversity training feeling angry and with greater animosity toward other groups (“There’s no way I’m biased!”). And threats of punishment, by the law in this case, typically lead to psychological “reactance” whereby people reject the desired behavior (“Nobody’s telling me what I can’t say!”). This kind of training can turn off even supporters of equal-opportunity programs.

A better way

It doesn’t have to be this way, and Dobbin and Kalev’s research on training points to a better alternative. Instead of using legal scare tactics, training programs should give managers a way to counter biases—namely, training in strategies for cultural inclusion. This kind of training teaches skills in listening, observation and intervention. It thus helps managers to hear employee concerns, notice when workers are feeling shunned or dissed, and intervene. It also offers skills for starting tough conversations about how to treat colleagues at work.

Those are skills from Management 101, but managers often don’t want to hear bad news, so they don’t ask employees about troubles, watch teams for signs of bullying, or speak up when they sense a problem. Reminding managers that they can use these tools to suss out problems and nip them in the bud helps them to feel capable of managing biases and microaggressions. When managers use these skills, they retain women and people of color for long enough to come up for promotion. That’s how good diversity training can boost diversity. Unfortunately, only about a quarter of diversity trainings emphasize cultural inclusion.

Moreover, if training succeeds in conveying the findings from bias research—that bias is unseen but pervasive—it can build support for wider systemic changes designed to tear down obstacles to equal opportunity. In that sense, training isn’t designed to blame people for their moral failings. Instead, it’s galvanizing them to support organizational change by arming them with knowledge.

In the end, DEI training can’t squelch implicit bias; nothing short of changing people’s life experiences can do that. But when done right, implicit-bias education can alert students to the fact that people committed to equality nonetheless hold biases. And that knowledge can, in turn, motivate them to reshape their workplaces to counter discrimination by democratizing key parts of the career system.

That means extending recruitment visits from Harvard to Howard; offering mentors to each and every worker; and inviting all employees to nominate themselves for skill and management training programs. It means offering work-life supports to people up and down the ladder. Each of these changes has been shown to produce significant increases in managerial diversity.

The lesson here, the one that should be at the core of DEI training, is that implicit bias resides in individuals, but it resides in organizational career systems as well. And fixing those systems is as simple as democratizing them.

Mahzarin Banaji is a professor of psychology at Harvard University and co-author of “Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People.” Frank Dobbin is a professor of sociology at Harvard University and co-author of “Getting to Diversity: What Works and What Doesn’t.” They can be reached at [email protected].

[ Via: https://archive.is/0D4kV ]

==

#diversity training#DEI training#implicit bias#implicit association#implicit bias test#implicit association test#diversity equity and inclusion#diversity#equity#inclusion

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Importantly, our findings reveal that class-based affirmative action (favoring students from more disadvantaged backgrounds) is not necessary to increase socioeconomic diversity at such colleges; simply removing the admissions advantages currently conferred to students from high-income families (or offsetting them with corresponding advantages for students from lower-income families) could increase socioeconomic diversity by an amount comparable to the impacts of race-based affirmative action on racial diversity.” -- Raj Chetty (Harvard), David J. Deming (Harvard), and John N. Friedman (Brown) of the National Bureau of Economic Research

In other words, race-based affirmative action wasn't giving non-white kids an unfair leg up, it was canceling out the unfair leg up that universities were already giving to wealthy white kids.

Honestly, the cancellation of both race-based and wealth-based affirmative action could be a huge benefit for an unexpected group. If both are ended it'll probably be a net neutral for minority students and it'll be a net negative for wealthy, white students, but it'll be a huge benefit for poor white students who will suddenly be competing on a relatively level playing field.

That's a group nobody really talks about, but generational poverty among white families, particularly in some parts of the country, is as real and grinding as among minorities. I'm certainly not going to argue that the end of affirmative action is a good thing but, if we're lucky, at least some deserving people might benefit from the end of affirmative action.

If you're interested, here is the full paper.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Detroit, the spatial mismatch of people to jobs and opportunities is stark. It gets all the more glaring when the Census Bureau (LEHD) reveals that just 30% of available jobs in Detroit are held by Detroit residents. The Opportunity Index by the Kirwan Institute showed this same mismatch nearly a decade ago and included an update for the Kresge Foundation. Opportunity had improved in greater downtown and worsened in Detroit’s neighborhoods between 2000 and 2010. The more recent Opportunity Atlas from Opportunity Insights, Harvard University, and Brown University builds off Raj Chetty’s research into “Which neighborhoods in America offer children the best chance to rise out of poverty?" Here, it's clear that healthcare, education, and government sectors anchor Detroit employment, which is why Detroit’s three main hospital zones heavily highlight jobs. This is evident in greater downtown with the Detroit Medical Center in Midtown (along with Wayne State University), in Northwest Detroit where Sinai-Grace is located, and along the Eastside border with St. John’s Hospital and a number of skilled nursing facilities.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Been thinking a lot about this economic study by Raj Chetty.

Zipcode Destiny: The Persistent Power Of Place And Education https://www.npr.org/2018/11/12/666993130/zipcode-destiny-the-persistent-power-of-place-and-education The stories we tell about ourselves — stories of success and stories of failure — often have their beginnings in the distant past. Sometimes, they start in our childhoods. Sometimes, before we were even born. This idea may sound poetic, but when it comes to economic mobility, there's evidence to back it up. Raj Chetty, an economist at Harvard, is responsible for some of the most powerful evidence, drawing on data from many millions of Americans. Raj has found that early variables in your life, from the quality of your kindergarten teacher to the neighborhood you grew up in, can have lasting effects. And those effects often result in dramatically divergent outcomes in different parts of the country.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

A modest intervention that helps low-income families beat the poverty trap

New Post has been published on https://sunalei.org/news/a-modest-intervention-that-helps-low-income-families-beat-the-poverty-trap/

A modest intervention that helps low-income families beat the poverty trap

Many low-income families might desire to move into different neighborhoods — places that are safer, quieter, or have more resources in their schools. In fact, not many do relocate. But it turns out they are far more likely to move when someone is on hand to help them do it.

That’s the outcome of a high-profile experiment by a research team including MIT economists, which shows that a modest amount of logistical assistance dramatically increases the likelihood that low-income families will move into neighborhoods providing better economic opportunity.

The randomized field experiment, set in the Seattle area, showed the number of families using vouchers for new housing jumped from 15 percent to 53 percent when they had more information, some financial support, and, most of all, a “navigator” who helped them address logistical challenges.

“The question we were after is really what drives residential segregation,” says Nathaniel Hendren, an MIT economist and co-author of the paper detailing the results. “Is it due to preferences people have, due to having family or jobs close by? Or are there constraints on the search process that make it difficult to move?” As the study clearly shows, he says, “Just pairing people with [navigators] broke down search barriers and created dramatic changes in where they chose to live. This was really just a very deep need in the search process.”

The study’s results have prompted U.S. Congress to twice allocate $25 million in funds allowing eight other U.S. cities to run their own versions of the experiment and measure the impact.

That is partly because the result “represented a bigger treatment effect than any of us had really ever seen,” says Christopher Palmer, an MIT economist and a co-author of the paper. “We spend a little bit of money to help people take down the barriers to moving to these places, and they are happy to do it.”

Having attracted attention when the top-line numbers were first aired in 2019, the study is now in its final form as a peer-reviewed paper, “Creating Moves to Opportunity: Experimental Evidence on Barriers to Neighborhood Choice,” published in this month’s issue of the American Economic Review.

The authors are Peter Bergman, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin; Raj Chetty, a professor at Harvard University; Stefanie DeLuca, a professor at Johns Hopkins University; Hendren, a professor in MIT’s Department of Economics; Lawrence F. Katz, a professor at Harvard University; and Palmer, an associate professor in the MIT Sloan School of Management.

New research renews an idea

The study follows other prominent work about the geography of economic mobility. In 2018, Chetty and Hendren released an “Opportunity Atlas” of the U.S., a comprehensive national study showing that, other things being equal, some areas provide greater long-term economic mobility for people who grow up there. The project brought renewed attention to the influence of place on economic outcomes.

The Seattle experiment also follows a 1990s federal government program called Moving to Opportunity, a test in five U.S. cities helping families seek new neighborhoods. That intervention had mixed results: Participants who moved reported better mental health, but there was no apparent change in income levels.

Still, in light of the Opportunity Atlas data, the scholars decided revisit the concept, with a program they call Creating Moves to Opportunity (CMTO). This provides housing vouchers along with a bundle of other things: Short-term financial assistance of about $1,000 on average, more information, and the assistance of a “navigator,” a caseworker who would help troubleshoot issues that families encountered.

The experiment was implemented by the Seattle and King County Housing Authorities, along with MDRC, a nonprofit policy research organization, and J-PAL North America. The latter is one of the arms of the MIT-based Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), a leading center promoting randomized, controlled trials in the social sciences.

The experiment had 712 families in it, and two phases. In the first, all participants were issued housing vouchers worth a little more than $1,500 per month on average, and divided into treatment and control groups. Families in the treatment group also received the CMTO bundle of services, including the navigator.

In this phase, lasting from 2018 to 2019, 53 percent of families in the treatment group used the housing vouchers, while only 15 percent of those in the control group used the vouchers. Families who moved dispersed to 46 different neighborhoods, defined by U.S. Census Bureau tracts, meaning they were not just shifting en masse from one location to one other.

Families who moved were very likely to want to renew their leases, and expressed satisfaction with their new neighborhoods. All told, the program cost about $2,670 per family. Additional research scholars in the group have conducted about changes in income suggest the program’s direct benefits are 2.5 times greater than its costs.

“Our sense is that’s a pretty reasonable return for the money compared to other strategies we have to combat intergenerational poverty,” Hendren says.

Logistical and emotional support

In the second phase of the experiment, lasting from 2019 to 2020, families in a treatment group received individual components of the CMTO support, while the control group again only received the housing vouchers. This way, the researchers could see which parts of the program made the biggest difference. The vast majority of the impact, it turned out, came from receiving the full set of services, especially the “customized” help of navigators.

“What came out of the phase two results was that the customized search assistance was just invaluable to people,” Palmer says. “The barriers are so heterogenous across families.” Some people might have trouble understanding lease terms; others might want guidance about schools; still others might have no experience renting a moving truck.

The research turned up a related phenomenon: In 251 follow-up interviews, families often emphasized that the navigators mattered partly because moving is so stressful.

“When we interviewed people and asked them what was so valuable about that, they said things like, ‘Emotional support,’” Palmer observes. He notes that many families participating in the program are “in distress,” facing serious problems such as the potential for homelessness.

Moving the experiment to other cities

The researchers say they welcome the opportunity to see how the Creating Moves to Opportunity program, or at least localized replications of it, might fare in other places. Congress allocated $25 million in 2019, and then again in 2022, so the program could be tried out in eight metro areas: Cleveland, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Nashville, New Orleans, New York City, Pittsburgh, and Rochester. With the Covid-19 pandemic having slowed the process, officials in those places are still examing the outcomes.

“It’s thrilling to us that Congress has appropriated money to try this program in different cities, so we can verify it wasn’t just that we had really magical and dedicated family navigators in Seattle,” Palmer says. “That would be really useful to test and know.”

Seattle might feature a few particularities that helped the program succeed. As a newer city than many metro areas, it may contain fewer social roadblocks to moving across neighborhoods, for instance.

“It’s conceivable that in Seattle, the barriers for moving to opportunity are more solvable than they might be somewhere else.” Palmer says. “That’s [one reason] to test it in other places.”

Still, the Seattle experiment might translate well even in cities considered to have entrenched neighborhood boundaries and racial divisions. Some of the project’s elements extend earlier work applied in the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program, a voucher plan run by the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership. In Seattle, though, the researchers were able to rigorously test the program as a field experiment, one reason it has seemed viable to try replicate it elsewhere.

“The generalizable lesson is there’s not a deep-seated preference for staying put that’s driving residential segregation,” Hendren says. “I think that’s important to take away from this. Is this the right policy to fight residential segregation? That’s an open question, and we’ll see if this kind of approach generalizes to other cities.”

The research was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, the Surgo Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, and Harvard University.

0 notes

Text

A modest intervention that helps low-income families beat the poverty trap

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/a-modest-intervention-that-helps-low-income-families-beat-the-poverty-trap/

A modest intervention that helps low-income families beat the poverty trap

Many low-income families might desire to move into different neighborhoods — places that are safer, quieter, or have more resources in their schools. In fact, not many do relocate. But it turns out they are far more likely to move when someone is on hand to help them do it.

That’s the outcome of a high-profile experiment by a research team including MIT economists, which shows that a modest amount of logistical assistance dramatically increases the likelihood that low-income families will move into neighborhoods providing better economic opportunity.

The randomized field experiment, set in the Seattle area, showed the number of families using vouchers for new housing jumped from 15 percent to 53 percent when they had more information, some financial support, and, most of all, a “navigator” who helped them address logistical challenges.

“The question we were after is really what drives residential segregation,” says Nathaniel Hendren, an MIT economist and co-author of the paper detailing the results. “Is it due to preferences people have, due to having family or jobs close by? Or are there constraints on the search process that make it difficult to move?” As the study clearly shows, he says, “Just pairing people with [navigators] broke down search barriers and created dramatic changes in where they chose to live. This was really just a very deep need in the search process.”

The study’s results have prompted U.S. Congress to twice allocate $25 million in funds allowing eight other U.S. cities to run their own versions of the experiment and measure the impact.

That is partly because the result “represented a bigger treatment effect than any of us had really ever seen,” says Christopher Palmer, an MIT economist and a co-author of the paper. “We spend a little bit of money to help people take down the barriers to moving to these places, and they are happy to do it.”

Having attracted attention when the top-line numbers were first aired in 2019, the study is now in its final form as a peer-reviewed paper, “Creating Moves to Opportunity: Experimental Evidence on Barriers to Neighborhood Choice,” published in this month’s issue of the American Economic Review.

The authors are Peter Bergman, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin; Raj Chetty, a professor at Harvard University; Stefanie DeLuca, a professor at Johns Hopkins University; Hendren, a professor in MIT’s Department of Economics; Lawrence F. Katz, a professor at Harvard University; and Palmer, an associate professor in the MIT Sloan School of Management.

New research renews an idea

The study follows other prominent work about the geography of economic mobility. In 2018, Chetty and Hendren released an “Opportunity Atlas” of the U.S., a comprehensive national study showing that, other things being equal, some areas provide greater long-term economic mobility for people who grow up there. The project brought renewed attention to the influence of place on economic outcomes.

The Seattle experiment also follows a 1990s federal government program called Moving to Opportunity, a test in five U.S. cities helping families seek new neighborhoods. That intervention had mixed results: Participants who moved reported better mental health, but there was no apparent change in income levels.

Still, in light of the Opportunity Atlas data, the scholars decided revisit the concept, with a program they call Creating Moves to Opportunity (CMTO). This provides housing vouchers along with a bundle of other things: Short-term financial assistance of about $1,000 on average, more information, and the assistance of a “navigator,” a caseworker who would help troubleshoot issues that families encountered.

The experiment was implemented by the Seattle and King County Housing Authorities, along with MDRC, a nonprofit policy research organization, and J-PAL North America. The latter is one of the arms of the MIT-based Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), a leading center promoting randomized, controlled trials in the social sciences.

The experiment had 712 families in it, and two phases. In the first, all participants were issued housing vouchers worth a little more than $1,500 per month on average, and divided into treatment and control groups. Families in the treatment group also received the CMTO bundle of services, including the navigator.

In this phase, lasting from 2018 to 2019, 53 percent of families in the treatment group used the housing vouchers, while only 15 percent of those in the control group used the vouchers. Families who moved dispersed to 46 different neighborhoods, defined by U.S. Census Bureau tracts, meaning they were not just shifting en masse from one location to one other.

Families who moved were very likely to want to renew their leases, and expressed satisfaction with their new neighborhoods. All told, the program cost about $2,670 per family. Additional research scholars in the group have conducted about changes in income suggest the program’s direct benefits are 2.5 times greater than its costs.

“Our sense is that’s a pretty reasonable return for the money compared to other strategies we have to combat intergenerational poverty,” Hendren says.

Logistical and emotional support

In the second phase of the experiment, lasting from 2019 to 2020, families in a treatment group received individual components of the CMTO support, while the control group again only received the housing vouchers. This way, the researchers could see which parts of the program made the biggest difference. The vast majority of the impact, it turned out, came from receiving the full set of services, especially the “customized” help of navigators.

“What came out of the phase two results was that the customized search assistance was just invaluable to people,” Palmer says. “The barriers are so heterogenous across families.” Some people might have trouble understanding lease terms; others might want guidance about schools; still others might have no experience renting a moving truck.

The research turned up a related phenomenon: In 251 follow-up interviews, families often emphasized that the navigators mattered partly because moving is so stressful.

“When we interviewed people and asked them what was so valuable about that, they said things like, ‘Emotional support,’” Palmer observes. He notes that many families participating in the program are “in distress,” facing serious problems such as the potential for homelessness.

Moving the experiment to other cities

The researchers say they welcome the opportunity to see how the Creating Moves to Opportunity program, or at least localized replications of it, might fare in other places. Congress allocated $25 million in 2019, and then again in 2022, so the program could be tried out in eight metro areas: Cleveland, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Nashville, New Orleans, New York City, Pittsburgh, and Rochester. With the Covid-19 pandemic having slowed the process, officials in those places are still examing the outcomes.

“It’s thrilling to us that Congress has appropriated money to try this program in different cities, so we can verify it wasn’t just that we had really magical and dedicated family navigators in Seattle,” Palmer says. “That would be really useful to test and know.”

Seattle might feature a few particularities that helped the program succeed. As a newer city than many metro areas, it may contain fewer social roadblocks to moving across neighborhoods, for instance.

“It’s conceivable that in Seattle, the barriers for moving to opportunity are more solvable than they might be somewhere else.” Palmer says. “That’s [one reason] to test it in other places.”

Still, the Seattle experiment might translate well even in cities considered to have entrenched neighborhood boundaries and racial divisions. Some of the project’s elements extend earlier work applied in the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program, a voucher plan run by the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership. In Seattle, though, the researchers were able to rigorously test the program as a field experiment, one reason it has seemed viable to try replicate it elsewhere.

“The generalizable lesson is there’s not a deep-seated preference for staying put that’s driving residential segregation,” Hendren says. “I think that’s important to take away from this. Is this the right policy to fight residential segregation? That’s an open question, and we’ll see if this kind of approach generalizes to other cities.”

The research was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, the Surgo Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, and Harvard University.

#000#2022#America#approach#attention#bundle#change#cities#comprehensive#covid#data#driving#economic#Economics#experimental#federal#Fight#financial#form#Foundation#Full#Geography#Government#hand#Health#housing#how#impact#Interviews#issues

0 notes

Text

Gimana Cara Naik Kelas

Langkah-Langkah Naik Kelas

Latar Belakang

Bayangkan dunia di mana setiap orang memiliki kesempatan yang sama untuk mencapai impian mereka, tanpa memandang latar belakang sosial dan ekonomi mereka. Dunia ini bukan hanya utopia, tetapi sesuatu yang dapat dicapai melalui peningkatan mobilitas sosial. Menurut Social Mobility Index dari World Economic Forum (WEF), mobilitas sosial mengacu pada kemampuan individu untuk bergerak ke atas dalam hierarki sosial-ekonomi. Negara-negara dengan tingkat mobilitas sosial yang tinggi cenderung lebih makmur dan stabil. Raj Chetty, seorang ekonom terkemuka, meneliti upward mobility dan menemukan bahwa anak-anak yang tumbuh di lingkungan yang mendukung memiliki peluang yang lebih besar untuk meraih kesuksesan di masa depan. Namun, bagaimana kita dapat memastikan bahwa semua orang memiliki kesempatan untuk naik kelas?

Seneca: Luck Is What Happens When Preparation Meets Opportunity

Menurut filsuf Romawi Seneca, "Keberuntungan adalah apa yang terjadi ketika persiapan bertemu dengan kesempatan." Untuk naik kelas, kita memerlukan kombinasi antara persiapan yang matang dan kesempatan yang tepat. Kesempatan ini bisa datang dari berbagai program yang dirancang untuk mendukung mobilitas sosial.

Mencari Kesempatan (Monopoli aja ada kartu kesempatan, masa hidup kita engga?)

Program Lembaga Internasional: Organisasi seperti Perserikatan Bangsa-Bangsa (PBB) memiliki berbagai program yang mendukung pendidikan, kesehatan, dan pembangunan ekonomi. Program seperti Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) berfokus pada mengurangi kemiskinan dan meningkatkan kualitas hidup, yang secara langsung berdampak pada mobilitas sosial.

Program Pemerintah Indonesia: Pemerintah Indonesia memiliki berbagai inisiatif untuk mendukung pendidikan dan pengembangan diri. Contoh program yang terkenal adalah Bidikmisi, yang memberikan beasiswa kepada mahasiswa berprestasi dari keluarga kurang mampu. Di tingkat daerah, terdapat beasiswa seperti Beasiswa Jawa Barat yang membantu siswa-siswa berprestasi melanjutkan pendidikan tinggi.

Program Lembaga NGO: Banyak NGO yang menawarkan program pengembangan diri, seperti kursus gratis di platform seperti Coursera. Program-program ini memungkinkan individu untuk meningkatkan keterampilan mereka tanpa harus mengeluarkan biaya yang besar.

Menyiapkan Diri: Meningkatkan Semua Segmen Diri

Seperti dalam permainan video RPG, kita perlu meningkatkan berbagai aspek diri kita untuk siap menghadapi peluang yang datang.

Strength (Kekuatan): Fokus pada empat hal ini untuk meningkatkan kekuatan fisik dan mental:

Tidur: Pastikan tidur yang cukup dan berkualitas.

Makan & Minum: Konsumsi makanan sehat dan hidrasi yang cukup.

Nafas: Latihan pernapasan untuk mengurangi stres dan meningkatkan fokus.

Olahraga: Rutin berolahraga untuk menjaga kebugaran tubuh.

Wisdom (Kebijaksanaan): Tingkatkan pengetahuan dengan membaca tiga buku ini:

Naval Book: Mengajarkan prinsip-prinsip kebijaksanaan dan kebebasan finansial.

Atomic Habits: Membantu membentuk kebiasaan baik dan menghilangkan kebiasaan buruk.

Master Your Time, Master Your Life: Manajemen waktu yang efektif untuk mencapai tujuan.

Agility (Kelincahan): Menjadi lebih lincah dan adaptif dengan menggunakan tiga platform ini:

ChatGPT/Gemini: Untuk memperoleh informasi dan pengetahuan dengan cepat.

Canva: Untuk mendesain materi visual dengan mudah.

Google Platform: Untuk berbagai alat produktivitas dan kolaborasi.

Luck (Keberuntungan): Tingkatkan keberuntungan dengan fokus pada tiga hal gratis ini:

Podcast: Dengar podcast yang menginspirasi dan edukatif.

Micro Adventure: Petualangan kecil yang memperkaya pengalaman hidup.

Kegiatan Sosial: Terlibat dalam kegiatan sosial untuk memperluas jaringan dan membuka peluang baru.

Intelligence (Kecerdasan): Tingkatkan kecerdasan dengan tiga langkah ini:

Baca Buku Harian: Konsumsi bacaan yang memperkaya pengetahuan.

Cari Cara Naik Kelas di Sekolah atau Kejar Beasiswa: Terus mencari peluang pendidikan dan beasiswa.

Belajar Stoik: Filosofi stoik untuk meningkatkan ketahanan mental dan emosi.

Dengan mengikuti langkah-langkah ini, kita tidak hanya siap untuk memanfaatkan setiap kesempatan yang datang, tetapi juga membangun fondasi yang kuat untuk mencapai kesuksesan jangka panjang. Naik kelas bukanlah hal yang mustahil; dengan persiapan yang tepat dan memanfaatkan kesempatan yang ada, kita bisa mengubah nasib kita dan membuka jalan bagi generasi berikutnya.

0 notes

Text

Gender affected by dysfunction in families

In today’s society, people have different struggles and adversities they must overcome, at times people face sets of trials and tribulations and react to things based on how they were raised. In many homes around the world, there is dysfunction, and this dysfunction can have either negative or positive effects on people depending on their gender.

Households have gender roles and gender roles have a major effect on how households are run.

Statistics from Pew Research Centre show that between 1965 to 2011 the gender roles of mothers and fathers differed vastly on how much time they spent between child care, housework, and doing paid work.

This study shows that in that period mothers have done more hours of housework, and childcare work than fathers, however, fathers have done more time on paid work than mothers. This indicates that mothers spend more time at home committing to housework and raising children than fathers do.

Further evidence from these three studies shows that a majority of women compared to their male counterparts are working less in jobs and earning less. This is a big reason why throughout time in most families it is seen that fathers and husbands take the role of financial providers. The gender pay gap is one of the reasons why there are specific gender roles, especially in heterosexual households.

Heterosexual households are influenced by tradition and by 1950 gender roles. Same-sex couple households on the other hand make decisions based on negotiations and are not easily influenced by gender expectations.

A quote from a same-sex-led household:

"Well, I think one of the main advantages of being in a lesbian relationship for me that unlike heterosexual couples there are no assumptions about how we are going to divide things up and how we’re going to cope . . . [heterosexuals are] still all the time having to work against these kind of very dominant set of assumptions about how things should be done in heterosexual households, whereas we don’t have that".

the advantages and disadvantages vary through households some may enjoy negotiating while others enjoy what is expected out of them.

Families in every household face different troubles, some more severe than others, at times some marriages in families can end, and this impacts children. Many boys become delinquents, struggle in schools, and have legal troubles, while girls perform well in schools and mature quickly.

Source: Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Frina Len, Jeremy Majerovitz, & Benjamin Scuderi , "Childhood Environment and Gender Gaps in Adulthood," NBER, Jan. 2016

The male gender from married households do far better than females in married households but a different result is shown in a single-parent household where it shows that both genders struggle however the male gender struggles equally if not more than the female gender.

Life is clearly more difficult in a single-parent household in many ways such as financially, and emotionally. A big part of the finance part could be that the father figure (as stated before, father figures are more likely to earn more than their spouses) may not be associated with the single-parent household, and vice versa the mother figure not being there, might make the children suffer emotionally.

Previously we mentioned how family dysfunction can negatively impact boys and how it can positively impact girls. The issue is girls are not fully safe from dysfunction either.

Source: American Family Survey, 2016

Growing up with major family dysfunction can cause girls to later in life have relationship issues. This study shows that women with a parent who was not married continuously, have more relationship troubles than women who had a 2-parent household and their respective male counterparts.

Source:American Family Survey, 2016

Another struggle women face from growing up in dysfunctional households is that later in life they face more economic crisis than anyone else.

Gender roles in households and the gender pay gap can be looked at through many scopes and lenses but each household will have its own struggles, and no matter what single-parent households will almost always struggle more than a 2 parent household whether it is led by heterosexual couples or same-sex couples. Dysfunction and instability in families are what impact lives across the world the most. The gender pay gap and gender roles need to be changed or adjusted so that single-parent households do not continue to suffer.

0 notes

Text

🎉 Happy 3rd Work Anniversary! 🥳

Joel Raj Bathula

Karthik Gatadi

Jaya Krishna Munnaluri

Soujanya Gavarraju

Sravya Chetty

Sravani Reddy Gogulamudi

Siva Ram Valavala

Satya Harish Peruri

Abhinay Reddy Yerragonda

Sravan Kumar Gangelly

Darshan C Baikadi

Alle Vamshi Krishna

Baji Thota

Your unwavering dedication has been instrumental in our success. Here's to many more accomplishments! 🎈👏

Big thanks to Mr. Vijay Pureti for honoring our employees' work anniversaries and presenting certificates of appreciation!

#thank you#team recognition#milestone celebration#employee work anniversaries#work anniverary celebration#nationsbenefits india

0 notes

Text

Using tax records, standardized testing data, and admissions records from 1996 to 2021, Raj Chetty and David Deming of Harvard and John Friedman of Brown find that highly selective, “Ivy-Plus” private universities admit different students than selective public flagship universities. Among students with comparable standardized test scores, Ivy-Plus universities admit a higher percentage of students from very high-income families than from others, while the difference is negligible at selective flagships. This is driven by legacy admissions, athletic recruiting, and admissions from private high schools. The authors also find that graduates of Ivy-Plus universities don’t earn more on average than comparable graduates of selective public flagships, but that they are much more likely to end up in the top 1% of wage earners, attend elite graduate schools and work for elite firms. The authors conclude that Ivy-Plus universities could become more socioeconomically diverse if they eliminated preferences for legacies, athletes, and private school students.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Transcript: Explaining America with Raj Chetty - The Washington Post Transcript: Explaining America with Raj Chetty The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/washington-post-live/2023/08/16/transcript-explaining-america-with-raj-chetty/

0 notes

Link

Alternate title: SEXIEST MAN IN ECONOMICS TELLS ALL.

32 notes

·

View notes