#Race and ethnicity in the United States Census

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Most Prevalent Race or Ethnicity Group by County in the US 🇺🇸 according to the 2020 United States census

by cactusmapping

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

If there is a depth to which U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump cannot sink when attacking his opponents, we are yet to see it. His latest salvo came at the convention of the National Association of Black Journalists in July, when he asked of Vice President Kamala Harris, “Is she Indian or is she Black?” The gasps, reportedly, were audible.

His question was meant to undermine her authenticity, of course, and it deserved the opprobrium it received. But it also proved that even with President Joe Biden out of the running, age is still an issue in the upcoming election. Trump’s politics of categorization belongs to a time that younger Americans have never known, when the demographic landscape of the United States couldn’t have been more different.

Consider that Trump was born in 1946, two decades before the nationwide lifting of anti-miscegenation laws, which prohibited interracial marriage. In his formative years, Black Americans were living under Jim Crow policies. For the first half of the 20th century, immigration from Asia had been kept to a bare minimum, first under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and then the Immigration Act of 1924, both passed with an eye to maintaining the United States’ whiteness.

Trump was the product of a time in which people really were expected to occupy fixed racial boxes, kept discrete by law, “when the walls of race were clear and straight,” as sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois put it. An American could be legally Black by virtue of a single Black great-grandparent. Never multiracial or racially ambiguous, as they might be in most other countries—only Black. So, when Trump demands of Harris that she be one or the other, Indian or Black (assuming that his question is sincere), perhaps it is beyond his imagination that anyone might be both.

Harris, on the other hand, reflects the United States as it is now: a tapestry of racial and ethnic diversity in which few can pretend that they are easily defined. She was born in 1964, a few months after the Civil Rights Act was passed. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 would enable a substantial increase in Asian immigration in that same decade.

When Harris was a teenager, those of South Asian heritage living in the United States still numbered fewer than half a million. They were practically invisible to most other Americans. There was such uncertainty about their racial identity that in one national opinion poll conducted by the National Opinion Research Center in 1978, 15 percent of respondents believed that Indians were Black, and another 11 percent saw them as white. Today, though, Indians are the second-largest immigrant group in the United States, after Mexicans and just before Chinese. They have their own demographic checkbox in the census.

Far more significantly, Americans are less likely than ever to identify with a single race or ethnicity. In 2000, in response to demands to accommodate those of mixed heritage, the U.S. Census Bureau gave people the option to tick more than one racial box for the first time. That year, almost 7 million Americans reported belonging to more than one race (interestingly, 823 of these respondents claimed six races). A decade later, that number had gone up by almost a third.

In the most recent census, conducted in 2020, partly because of improvements to how data was collected, that number went up again—this time by 276 percent. Unsurprisingly, younger Americans are the most likely to report being multiracial.

So, with his obsession over categorization, Trump couldn’t sound more out of date. He is trying to force people into the kinds of boxes that defined lives when he was a child. He is telling Americans that there is only one way to be white, or Black, or Indian, when they already know this isn’t true. It is a politics that dares to put others in their place, yes, but also fails to see them as they are.

Coincidentally, his ill-judged remarks about Harris happened to come just days before the centenary of the birth of one of the United States’ most brilliant social critics, James Baldwin, who himself gloriously embodied the contradictions of identity. In his 1949 essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel”—as fresh now as the day it was written, in sharp contrast to Trump’s desperately tired ideas about race—Baldwin cautioned against succumbing to the fallacy that it is “categorization alone which is real and which cannot be transcended.”

It is perfectly possible to live within and between cultures and maintain an authentic sense of self. it is not just Harris who proves this, but the millions of Americans who have enriched the nation by mixing, marrying, and building a more integrated society. They have changed the country for the better.

When Trump casts aspersions on Harris’s racial background, he does the same to countless others. He questions the pluralistic society that the United States has become—one in which race has already come to matter less than it used to.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reference archived on our website

Covid is an intersectional issue.

Abstract

Substantial racial/ethnic and gender disparities in COVID-19 mortality have been previously documented. However, few studies have investigated the impact of individual socioeconomic position (SEP) on these disparities.

Objectives: To determine the joint effects of SEP, race/ethnicity, and gender on the burden of COVID-19 mortality. A secondary objective was to determine whether differences in opportunities for remote work were correlated with COVID-19 death rates for sociodemographic groups.

Design: Annual mortality study which used a special government tabulation of 2020 COVID-19-related deaths stratified by decedents’ SEP (measured by educational attainment), gender, and race/ethnicity. Setting: United States in 2020. Participants: COVID-19 decedents aged 25 to 64 years old (n = 69,001). Exposures: Socioeconomic position (low, intermediate, and high), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Black, Asian, Indigenous, multiracial, and non-Hispanic white), and gender (women and men). Detailed census data on occupations held by adults in 2020 in each of the 36 sociodemographic groups studied were used to quantify the possibility of remote work for each group.

Main Outcomes and Measures: Age-adjusted COVID-19 death rates for 36 sociodemographic groups. Disparities were quantified by relative risks and 95% confidence intervals. High-SEP adults were the (low-risk) referent group for all relative risk calculations. Results: A higher proportion of Hispanics, Blacks, and Indigenous people were in a low SEP in 2020, compared with whites. COVID-19 mortality was five times higher for low vs. high-SEP adults (72.2 vs. 14.6 deaths per 100,000, RR = 4.94, 95% CI 4.82–5.05). The joint detriments of low SEP, Hispanic ethnicity, and male gender resulted in a COVID-19 death rate which was over 27 times higher (178.0 vs. 6.5 deaths/100,000, RR = 27.4, 95% CI 25.9–28.9) for low-SEP Hispanic men vs. high-SEP white women. In regression modeling, percent of the labor force in never remote jobs explained 72% of the variance in COVID-19 death rates.

Conclusions and Relevance: SARS-CoV-2 infection control efforts should prioritize low-SEP adults (i.e., the working class), particularly the majority with “never remote” jobs characterized by inflexible and unsafe working conditions (i.e., blue collar, service, and retail sales workers).

#mask up#covid#pandemic#covid 19#wear a mask#public health#coronavirus#sars cov 2#still coviding#wear a respirator#race#gender

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Invention of Hispanics: What It Says About the Politics of Race

America’s surging politics of victimhood and identitarian division did not emerge organically or inevitably, as many believe. Nor are these practices the result of irrepressible demands by minorities for recognition, or for redress of past wrongs, as we are constantly told. Those explanations are myths, spread by the activists, intellectuals, and philanthropists who set out deliberately, beginning at mid-century, to redefine our country. Their goal was mass mobilization for political ends, and one of their earliest targets was the Mexican-American community.

These activists strived purposefully to turn Americans of this community (who mostly resided in the Southwestern states) against their countrymen, teaching them first to see themselves as a racial minority and then to think of themselves as the core of a pan-ethnic victim group of “Hispanics”—a fabricated term with no basis in ethnicity, culture, or race.

This transformation took effort—because many Mexican Americans had traditionally seen themselves as white. When the 1930 Census classified “Mexican American” as a race, leaders of the community protested vehemently and had the classification changed back to white in the very next census. The most prominent Mexican-American organization at the time—the patriotic, pro-assimilationist League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC)—complained that declassifying Mexicans as white had been an attempt to “discriminate between the Mexicans themselves and other members of the white race, when in truth and fact we are not only a part and parcel but as well the sum and substance of the white race.”

Tracing their ancestry in part to the Spanish who conquered South and Central America, they regarded themselves as offshoots of white Europeans.

Such views may surprise readers today, but this was the way many Mexican Americans saw their race until mid-century. They had the law on their side: a federal district court ruled in In Re Ricardo Rodríguez (1896) that Mexican Americans were to be considered white for the purposes of citizenship concerns. And so as late as 1947, the judge in another federal case (Mendez v. Westminster) ruled that segregating Mexican-American students in remedial schools in Orange County was unconstitutional because it represented social disadvantage, not racial discrimination.

At that time Mexican Americans were as white before the law as they were in their own estimation.

The process would only work if Mexican Americans “accepted a disadvantaged minority status,” as sociologist G. Cristina Mora of U.C. Berkeley put it in her study, Making Hispanics (2014). But Mexican Americans themselves left no doubt that they did not feel like members of a collectively oppressed minority at all. As Skerry noted, “[the] race idea is somewhat at odds with the experience of Mexican Americans, over half of whom designate themselves racially as white.” Even in the early 1970s, according to Mora, many Mexican-American leaders retained the view that “persons of Latin American descent were quite diverse and would eventually assimilate and identify as white.” And yet “Spanish/Hispanic/Latino” is now a well-established ethnic category in the U.S. Census, and many who select it have been taught to see themselves as a victmized underclass. How did this happen?

In other words, a distinctive set of beliefs, customs, and habits supported the American political system. If the Cajun, the Dutch, the Spanish—and the Mexicans—were to be allowed into the councils of government, they would have to adopt these mores and abandon some of their own. It is hard to argue that this formula has failed. Writing in 2004, political scientist Samuel Huntington reminded us that

“Millions of immigrants and their children achieved wealth, power, and status in American society precisely because they assimilated themselves into the prevailing culture.”

Indeed, merely calling Mexican-Americans a ‘minority’ and implying that the population is the victim of prejudice and discrimination has caused irritation among many who prefer to believe themselves indistinguishable [from] white Americans…. [T]here are light-skinned Mexican-Americans who have never experienced the faintest…discrimination in public facilities, and many with ambiguous surnames have also escaped the experiences of the more conspicuous members of the group.”

Even worse, there was also “the inescapable fact that…even comparatively dark-skinned Mexicans…could get service even in the most discriminatory parts of Texas,” according to the report. These experiences, so different from those of Africans in the South or even parts of the North, had produced

a long and bitter controversy among middle-class Mexican Americans about defining the ethnic group as disadvantaged by any other criterion than individual failures. The recurring evidence that well-groomed and well-spoken Mexican Americans can receive normal treatment has continuously undermined either group or individual definition of the situation as one entailing discrimination.

It is incumbent on us to pause and note exactly what these UCLA researchers were bemoaning. Their own survey was revealing that Mexican-Americans’ lived experiences did not square with their being passive victims of invidious, structural discrimination, much less racial animus. They owned their own failures, which—their experience told them—were remediable through individual conduct, not mass mobilization. Their touchstones were individualism, personal responsibility, family, solidarity, and independence—all cherished by most Americans at the time, but anathema to the activists.

The study openly admitted that reclassification as a collective entity serves the “purposes of enabling one to see the group’s problems in the perspective of the problems of other groups.” The aim was to show “that Mexican Americans share with Negroes the disadvantages of poverty, economic insecurity and discrimination.” The same thing, however, could have been said in the late 1960s of the Scots-Irish in Appalachia or Italian Americans in the Bronx. But these experiences were not on the same level as the crushing and legal discrimination that African Americans had faced on a daily basis. That is why the survey respondents emphasized “the distinctiveness of Mexican Americans” from Africans and “the difference in the problems faced by the two groups.” The UCLA researchers came out pessimistic: Mexican Americans were “not yet easy to merge with the other large minorities in political coalition.”

Thereafter, militants from La Raza, MALDEF, and other organizations put pressure on the Census Bureau to create a Hispanic identity for the 1980 Census—in order, as Mora puts it, “to persuade them to classify ‘Hispanics’ as distinct from whites.”

The Hispanic category was a Frankenstein’s monster, an amalgam of disparate ethnic groups with precious little in common.

The 1970 Census had included an option to indicate that the respondent was “Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, [or] Other Spanish.” But re-categorizing Mexican Americans and lumping them in with other residents of Latin American descent under a “Hispanic American” umbrella was a necessary move, Mora writes, because “this would best convey their national minority group status.”

The law states that “a large number of Americans of Spanish origin or descent suffer from racial, social, economic, and political discrimination and are denied the basic opportunities that they deserve as American citizens.” The very thing that defined Hispanics was victimhood.

IT IS SHOWN THAT THE HUMAN CATEGORY "WHITE" WAS BUILT UPON THE IDEA OF THAT BRITISH AS WHITE, CHRISTIAN, OF THEIR ESSENCE FREE,AND DESERVING OF RIGHTS AND PRIVILEGES FROM WHICH THOSE INSUFFICIENTLY BRITISH -LIKE COULD BE DENIED. JACQUELINE BATTALORA "BIRTH OF A WHITE NATION.

#hispanics#latina#afro latina#curvy latina#latin girls#latinx#sexy latina#thick latina#latino#kemetic dreams#brownskin#brown skin#mexican#mexicana#mexico#mexique#mextagram#white#black and white#white house#census data#censura#qsmp census bureau#u.s. census bureau#tumblr censure#the invention of the Hispanic#african#afrakan#afrakans#africans

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the 2020 United States Census, the largest ethnic group were the native Chamorros, accounting for 32.8% of the population. Asians, including Filipinos, Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese, accounted for 35.5% of the population. Other ethnic groups of Micronesia, including those of Chuukese, Palauan, and Pohnpeians, accounted for 13.2%. 10% of the population were multiracial, (two or more races). European Americans made up 6.8% of the population; 1% are African Americans, and 3% are Hispanic; there are 1,740 Mexicans in Guam, and there are other Hispanic ethnicities on the island. The estimated interracial marriage rate is over 40%.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 2024 Presidential Election: The Candidates’ Policies and Their Impact on Marginalized Groups

by Sofia Bocchino

Today, Americans know Kamala Harris as the first female Vice President of the United States, but what will we know her as after November 5th? The 2024 presidential election will be historic regardless of who wins, as Kamala Harris will be the first female candidate of color to make it this far into the election, and now the second woman running against former president Donald Trump.

Sources such as The New York Times indicate that this election is going to be close, where either candidate could win by a narrow margin. When considering who to vote for on election day, it is important for voters to educate themselves on the policies each candidate holds in order to make an informed decision to determine what the future of our country will look like. This is especially impactful for voters in swing states, who have the power to sway the state towards either candidate. Swing states also serve as a “battleground” for the competing parties, and according to NPR, where 75% or more of campaign funds are spent. It is crucial that Americans understand which candidates will protect their rights and best serve the country for the next four years.

Since Joe Biden dropped out of the race, Harris has worked tirelessly to continue progressive policies and restore freedom to marginalized communities. Her policies include restoring and protecting reproductive freedom, providing affordable housing, strengthening and bringing down the cost of health care, ensuring safety against gun violence and crime, fixing the immigration system, tackling the opioid and fentanyl crisis, protecting civil rights and freedoms, and so many more liberating policies that can be found on Harris’ website. For citizens who are less privileged and experience disadvantages due to lack of resources for issues they may be affected by, Kamala Harris proves to be the better choice for rebuilding the rights that these marginalized groups have been stripped of. According to Cambridge University Press, a recent study concluded that over 40.3% of U.S. citizens are politically, socially, and economically marginalized groups.

Although the 40.3% of Americans in marginalized groups still make up a little under half the population, that will increase with racial, gender, ethnic, and religious minorities, regardless of their income and privilege. Unlike Harris, Donald Trump’s policies are more conservative and radicalized, not taking into account the large percentage of the population that could be negatively impacted by what he is calling for, essentially a new system of government. Some of Trump’s policies include carrying out “the largest deportation in American history,” protecting the right to bear arms, cutting outsourcing, strengthening the military, cutting federal funding to schools which educate students on anything related to race, sexual orientation, or politics, keepinging men out of women’s sports, and determing women’s reproductive rights by states. All of these policies can be found on Trump’s website and The Washington Post.

These policies are directly targeted towards deporting immigrants, who, according to the American Immigration Council, make up 17% of the U.S. labor workforce, denying trangender people of basic equality and rights, and radicalizing the education system, leaving students uneducated on critical socio-political issues. With these policies in mind, it is important to consider how the Democratic or Republican parties in the running could affect the future of the United States of America. Conservative policies present limitations for minorities and intersecting marginalized groups, which together make up over half the population of the U.S. according to research conducted in 2020 by Census. If you are eligible to vote this year, please take into account how both candidates’ policies will not only affect you, but your friends, family, and most importantly, the country as a whole.

Harris’ policies serve as a beacon of hope to marginalized communities, minorities, and liberal groups in preserving their rights and access to better education, healthcare, housing, jobs, safety, and civil liberties. As I mentioned in the beginning of the article, this election is predicted to be close, and it is likely either candidate will win within the margins. It is important that swing state voters, single issue voters, and those undecided vote on November 5th, as every vote counts in the race to that will either progress our government forward or radicalize it.

From my perspective, I believe Harris has the ability to make a positive change in the U.S. government, and enforce policies that will positively impact the future of the country, helping to establish a fair balance between the majority and minority. If you are not yet eligible to vote, please educate your peers on the importance of voting and the policies each candidate plans to enact if elected. The future of the country is at the hands of its people, and it is our job to ensure everyone is granted their basic freedoms and rights as a human being, so if you are 18 or older on Tuesday, November 5th, please head to the polls and exercise your civic duty as an American citizen and vote, not only for your personal benefit, but for the benefit of all individuals who deserve the same rights, freedoms, justice, and equality.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 minute read

On 1st May this year, Johanita Dogbey, a 31-year-old Ghanaian British woman, was killed in broad daylight in Brixton, London. The man accused of attacking her, Mohamed Nur, a 33-year-old Somali British man, is currently in police custody and awaiting trial. Her death adds to a long list of Black women who have been found dead due to or under the suspicion of foul play in recent years: Darrell Buchanan, Blessing Olusegun and Valerie Forde, to name a few. With growing discourse surrounding the prevalence of Black femicide in the United States, following shocking revelations like the fact that Black women are four times as likely as white or Hispanic women to die a violent death, it’s time Britain recognised its own epidemic. On the surface, the data indicate no apparent racial disparities but a deeper look into the context of how these figures are produced points to a more complex and even dangerous reality for Black women in the UK.

Understanding Black femicide

The World Health Organization (WHO) generally defines femicide as the “intentional murder of women and girls because they are women” but allows for broader definitions encompassing any killings of women and girls. The vast majority of women’s murderers are men, with ‘intimate femicide’ (i.e. intimate partner violence) being the most typical form. Worldwide, over 35% of all women’s murders are reported to have been committed by a former or current husband or boyfriend. Conversely, just 5% of male homicides are committed by a current or former intimate partner (this includes gay and bisexual men). Other common types of femicide comprise honour killings (occurring mainly in the Middle East, South Asia and their respective diasporas), dowry deaths (most prevalent in India) and non-intimate femicide — often with a sexual motivation. Accordingly, Black femicide can be understood as the intentional killing of Black women and girls on the basis of their race, gender or both; it can also include any Black female homicide victims.

Looking at the global stats, we can see that in the US, Black women’s risk of homicide rivals that of Black men, with one dying on average every six hours in 2020. In South Africa, an average of nine women are killed every day, making it one of the most dangerous places in the world to live as a woman, particularly a Black woman. Predominantly Black Caribbean countries Antigua & Barbuda and Jamaica have the second and third highest femicide rates in the world, respectively, with El Salvador topping the list.

I n the UK, we know that a woman is killed on average every three days but the frequency of said violence happening to Black women is unclear, given a dearth of intersectional reporting on the issue. For example, the 2020 Femicide Census, an archive of the “women who have been killed by men in the UK and the men who have killed them”, records the ethnicity of just 22 out of 110 victims. Of this figure, 16 were white and six were Asian. Without further context, the takeaway here would be that no Black women (or at least a much smaller proportion) were killed by men within this dataset, which could then be extrapolated to apply to Britain’s population as a whole. When speaking about this to a representative of nia, the anti-violence against women and girls (VAWG) charity that oversees The Femicide Census, they acknowledged this is a problematic conclusion: “The lack of meaningful, verified (i.e. official public record material) data on ethnicity is an ongoing problem. Data on race and ethnicity is drawn from police responses to Freedom of Information requests (FoIs). Ethnicity was provided in only one-fifth of police FoIs, and even then, the terms used are inconsistent, arbitrary, sometimes meaningless, archaic or downright offensive, for example, ‘Dark European’ or ‘Oriental’.”

‘Global majority’ is used as a collective term to describe those racialised as non-white, who make up approximately 85% of the world’s population. Anecdotal evidence and interpersonal experiences from anti-VAWG service providers and service users alike suggest femicide disproportionately impacts global majority women in the UK, including Black women, according to nia. However, without more precise figures to back up these ideas, the ability to identify culture-specific risk factors, barriers to access and best methods of providing support is limited. “Without such data, there will be no evidence base for the need for specialist by and for organisations, additional targeted resources and overhauling practice and policy which may reflect racist and sexist attitudes or institutional racism and sexism,” nia concludes.

Inter-community issues present overlooked risk factors

Like other forms of violence against socially minoritised people, the line between what is and what isn’t an act of discrimination is often ambiguous. Dogbey’s death, for instance, has been framed as a completely “random attack” by media reports. Perhaps it simply was a case of wrong place, wrong time; perhaps not. Latoya Dennis, the founder of Black Femicide UK, thinks not, believing Dogbey’s killing to have been influenced by an underground culture of online inceldom and inter-community tensions between Somali and non-Somali Black groups. “I think there’s a strong incel community and I believe that a lot of Somali men are a part of that, from what I’ve seen online. I wouldn’t be surprised if the man who killed Johanita was a part of that community,” she tells us. Nur is reported to have (non-fatally) assaulted two other women and a man on 29th April, showing a gender bias in his crimes. When asked to expand, Dennis references hostile online encounters with Somali men on her platform after profiling the story of a Somali Bolt driver allegedly attempting to abduct a young, non-Somali Black woman. “That was the most backlash I’ve received through my work. I received a lot of threats and harassment, and I was also doxxed,” she explains.

Sistah space

W hether or not this sentiment is correct, it highlights a valid sense of intra-racial rift within Black Britain that the media and institutions alike fail to interrogate in depth, leaving Black women at risk. Unbothered Editor L’Oréal Blackett speaks to an overreliance on the UK’s few Black journalists to cover Black stories as a partial factor in these gaps in mainstream coverage: “When I’ve worked at major publications, these kinds of stories are looked at as an inter-community issue. There’s a sense of ‘we can’t touch that’ within these white (and male)-dominated newsrooms.” She continues: “UK media is relying on a handful of Black journalists to cover everything that goes on in our communities.”

Sistah Space, a domestic violence charity advocating and campaigning for Black and mixed-race British women of African and Caribbean descent, also cites racial and cultural prejudices as major reasons why Black British women’s deaths don’t receive as much attention as the deaths of white British women: “The media categorically does not give Black women and domestic abuse enough attention. For example, media coverage of the Sarah Everard case was on every news source for a period of time. Can you name any Black women who have had the same amount of coverage or outcry?”

It’s not just the media at fault here. As detailed above, there is an oversight when it comes to the interrogation and provision of race and ethnicity-specific insights from the government and police that potentially reflects apathetic and even racist (and sexist) attitudes towards female global majority concerns in this country. In March 2014, Valerie Forde, 45, and her 22-month-old baby were brutally murdered by Valerie’s ex-partner after her cries for help had been either downplayed or ignored by the authorities, exemplifying such failings. Six weeks prior to her death, Forde had told police that the then 53-year-old Roland McKoy had threatened to burn down her house with her and her baby inside. Instead of Forde’s warning being recorded as a threat to life, which would have required much closer monitoring, it was deemed a threat to property — a serious but far less urgent risk. Furthermore, BBC News reports that a civilian call handler failed to fully record and communicate critical information in the 999 call from one of Forde’s daughters on the day of the crime. Were it not for the “inaction” of authorities, Forde may have been alive today.

Sistah Space believes this to be the case and is advocating for Valerie’s Law, a proposal which would implement “mandatory cultural competency training that accounts for the cultural nuances and barriers, colloquialisms, languages and customs that make up the diverse Black community”. In 2021, the organisation launched a video campaign to illustrate the unequal treatment of Black and white female domestic abuse victims by law enforcement. Research conducted by Sistah Space reveals that in the UK, 86% of women of African and/or Caribbean heritage have either been a victim of domestic abuse or know a family member who has been assaulted. Only 57% of victims, however, said they would report the abuse to the police, likely due to a historic lack of confidence in law enforcement among Black Britons. Meanwhile, March 2020 to June 2021 figures from Refuge, the country’s largest specialist domestic abuse organisation, show that Black women were 14% less likely than white survivors of domestic abuse to be referred to Refuge for support.

Implementing meaningful change

The man accused of killing Johanita Dogbey will not be standing trial until 29th April 2024, joining tens of thousands of backlogged cases in London alone that will not be fully reviewed for an average of over a year. With Dogbey’s story falling out of the mainstream news cycle just over a week after her death, it’s hard to imagine a society where Black femicide is given the consideration it deserves. As things stand, we rely on specialist media platforms like Unbothered to do the work in platforming these narratives and organisations like nia and Sistah Space to push for more comprehensive statistics and cultural awareness among governing bodies. A greater emphasis on Afrofeminist data will ultimately be the building block for more informed insights into the realities and concerns of Black women in the UK. We must continue striving to make this issue a top priority, not just for us but for everyone.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The gap in male/female literacy [in the United States] diminished in a pattern affected by region, class and race. By 1840, when common schools offered the same hours of instruction to boys and girls, almost all white women in the Northeast could read and write. This level of literacy was not attained by Southern white women until the end of the 19th century. Rural women, immigrants and African-American women were illiterate longer than native-born, white and middle-class women. But no matter what particular group of person one studies and in what particular location, the literacy gap between men and women of the same group is not closed until nearly universal literacy is reached.

A similar observation can be made by studying levels of educational achievement in various groups and classes of the population. For example, until 1837 women were unable to enroll in any college or university. By 1870, they constituted 21 percent of the total undergraduate enrollment; by 1880, women constituted 32 percent of the undergraduate student body and by 1910 almost 40 percent. While the increase in the number of college-educated women is notable, it is more significant that it was not until 1920, when women were 47 percent of the college undergraduates, that women achieved equal access to college educations with men. Yet by the end of the 1930s, while the number of female college-trained undergraduates rose slightly, the number of women trained to the professional level declined dramatically. The low point in the 20th century came in 1960, when women were 35 percent of all students with a B.A. or first professional degree, and only 10 percent of all doctorates.

It is only since the 1920s that equal educational access for women has been won on all levels up to graduate school, yet vestiges of former educational deprivation continue to show up in women's lower achievement on college-level tests and in the awarding of scholarships. More important, no matter what the variation for a particular group to be considered (ethnicity, age, region, religion), what remains unvaryingly true is that women's access to education remains below that of males of their group. The single exception to this rule is the case of African-American women, who between 1890 and 1970 exceed males of their race in educational attainment. This is due to the vagaries of race discrimination, which offered little incentive for higher education for men, since even with advanced degrees they were confined to menial jobs. On the other hand, educated black women had a chance to escape domestic and menial service. Thus families had an incentive to foster the education of their daughters rather than of their sons. In this respect African-American families form an exception to the almost universal American pattern whereby families educationally deprive daughters for the sake of sons.

Thus, although educational access was won much later for all African-Americans than it was for whites, in 1960 the census shows that black female physicians represented nearly 10 percent of all black physicians, while white female physicians were 6 percent of all white physicians. Black women lawyers were 9 percent of all black lawyers, while white women lawyers were only 3 percent of all white lawyers. Similar patterns appear in the census data for schoolteachers. Ironically, one of the few gains of the 20th century civil rights movement which has remained in place is that the educational advantage of black men over black women now follows similar sexist patterns as that of white men over white women.

The pattern of women's struggle for equality of access to education in America is the same as it was in Europe: each level of institutionalized learning had to be separately and consecutively conquered. Resistance by individual men and by male-controlled establishments was relentless and unwavering. At every level of the educational establishment women had to first fight for the right to learn, then for the right to teach and finally for the right to affect the content of learning. The last has yet to be accomplished to any significant extent.

-Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Feminist Consciousness

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The entire thing about racism is that it's an idea invented to justify malpractice, like slavery.

The entire point of racism is to compare the different "races" as superior and inferior to each other. In other words, it is meant to be hierarchal.

So if we can agree that all humans belong to a single species, come from a single point of origin, deserve equal rights, are born with equal capabilities, and can not & should not be classified into subgroups with supposedly different social behaviors and physical & intellectual capabilities, then we agree that race is an outdated way of categorizing humans that should not exist.

Race and ethnicity are different because ethnicity is generally a more reliable categorization of people who share similar heritage and characteristics.

But race isn't that. There are many different racial categories and many old and stupid 19th century philosophers who all believed different things (i.e. monogenists believed all humans had a common origin, polygenists believed different races came from different origins), but the very core of it does not really categorize people by how closely related they are. It's a lot more based on appearance.

I'm tired of people pretending that race isn't an extremely fluid concept. You will be racialized based on how you look, even if it's not technically. For example, Italians are considered white in the modern-day United States most of the time, but in the past (and in Europe), that gets a lot more dicey. If you're Jewish, you'll be assumed as white or black most of the time, depending on how light or dark your skin is. Somewhat similarly, Arabs are expected to check "white" on the US census, but any Arab who lives in the US knows they are not treated like Europeans.

And I'd like to make something clear; I am not an "I don't see color" person. I think it is so important to be aware of a person's perceived race so that we can understand the racial injustice they face and the nuances involved. If you're an anti-racist, it's your job to understand the ins and outs of racism, truly. Because you have to know your enemy. You can't fight something you don't understand.

TL;DR: Race isn't real. It was invented by someone who was probably high and needed to believe he was biologically prone to being better than everyone else. Humans aren't dog breeds. Racism is a bitch.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

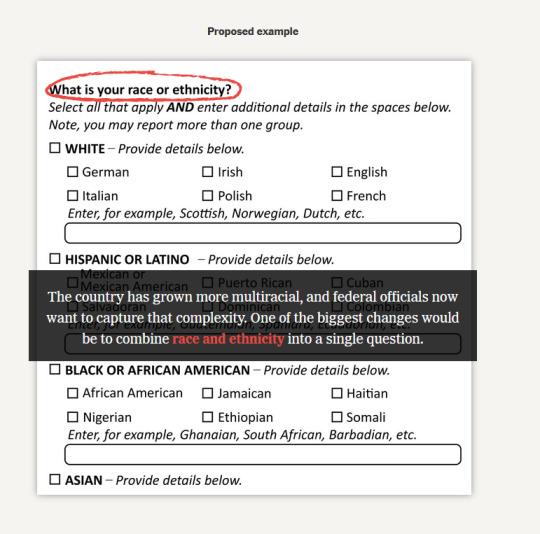

Since 1790, the decennial census has played a crucial role in creating and reshaping the ever-changing views of racial and ethnic identity in the United States.

Over the centuries, the census has evolved from one that specified broad categories — primarily “free white” people and “slaves” — to one that attempts to encapsulate the country’s increasingly complex demographics. The latest adaptation proposed by the Biden administration in January seeks to allow even more race and ethnicity options for people to describe themselves than the 2020 census did.

If approved, the proposed overhaul would most likely be adopted across all surveys in the country about health, education and the economy. Here’s what the next census could look like.

[ This article is a little interactive with floating text boxes etc, so its hard to screenshot effectively. ]

In some ways, the government is attempting to catch up with modern views of racial and ethnic identities.

There are complicated politics at work too, and the proposed changes have provoked criticism among some scholars and activists.

Many Hispanic or Latino U.S. residents mark “some other race,” typically because they don’t see themselves as “Black” or “white.” Supporters of the proposal say the changes reflect that Latinos have long been treated as a distinct racial group in the United States. But Afro-Latino scholars argue that the new method would mask important racial differences among Latinos.

Community leaders have been advocating for a “Middle Eastern or North African” category for years, pointing to the need for better data for this growing population, especially around health care, education and political representation. If the proposal is approved, this would be the first time since the 1970s that a completely new racial or ethnic category is added to the census.

A precise, universally accepted distinction between race and ethnicity does not exist. Instead, there’s a murky history of law, politics and culture around racial identity in America.

“There is no such thing as a perfect question,” said Roberto Ramirez, a population statistics expert at the U.S. Census Bureau. The bureau has conducted numerous tests in recent decades to improve the census so that people can more accurately identify themselves, he said.

If approved, the new race and ethnicity formulation will have wide-ranging impacts. Any organization receiving federal funding — down to local schools — would have to adhere to it. Race data informs how resources are distributed; whether equal employment policies and anti-discrimination laws can be enforced; and how congressional districts are drawn.

Ever since the census began measuring the U.S. population, race has been central to the counting. The census is more than a bureaucratic exercise; it embodies the country’s continued efforts to neatly categorize inherently nuanced and layered identities. Terms that are now widely viewed as outdated or even offensive had their place on the official forms for decades.

#census#data#information science#information access#civil rights#race and ethnicity#this is an interesting article if you can get access#i fucking hate paywalls but don't have the time to screenshot it all right now.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Melungeons are descendants of people of mixed ethnic ancestry who, before the end of the eighteenth century, were discovered living in limited areas of what is now the southeastern United States, notably in the Appalachian Mountains near the point where Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina converge. Earlier they may have lived near the Atlantic coast but, preferring a more secluded setting and seeking refuge from persecution, chose to move west as the coastal region became more densely populated by newcomers from Virginia and elsewhere.

The origin and early history of Melungeons remain relatively unknown. They have been identified at various times as having Portuguese, Spanish, French, Welsh, and Turkish ancestry; some theories even claim that they are descendants of members of Roanoke Island's Lost Colony of 1587. Most modern researchers have concluded that their ethnicity is triracial, with European, Native American, and African lineage. Their earliest ancestors may have been explorers, seamen, or colonists stranded along the Atlantic coast before permanent settlement had begun who later intermarried with Indians and Africans.

Melungeon skin tones varied from dark to light, reflecting their mixed heritage. In time, the U.S. Census Bureau classified them as "free persons of color." Because of their unique appearance, Melungeons faced extensive racial and social prejudice throughout much of their history. Although rarely subject to legal restrictions such as those imposed on blacks and Native Americans, they were often ostracized socially because of their nonwhite heritage. The term "Melungeon" itself was created and used as an insult by whites. Most researchers believe that it derived from the French word mélange, which means "mixture." Other possible linguistic roots include melon can, Turkish for "cursed soul"; the Italian word melongena, technically meaning "eggplant" but used in reference to someone with dark skin; and melan, the Greek word for "black." In any case, "Melungeon" came to signify a person of low social status and "impure" bloodlines, who was ignorant or possessed other negative traits.

The mystery surrounding Melungeons also led to a variety of folk beliefs, some of which portrayed them as frightening mythical creatures capable of evil deeds, including kidnapping children who misbehaved. While Melungeon ancestry is not uncommon in North Carolina Mountain counties such as Alleghany, Mitchell, and Ashe, the majority of Melungeons eventually settled in urban areas throughout the Southeast and became practically indistinguishable as a separate ethnic group. For generations, many people, seeking to avoid being stigmatized, ignored or denied their Melungeon ancestry. By the late twentieth century, however, several organizations were celebrating and seeking information about possible Melungeon family histories. In addition, researchers continue to examine Melungeon origins, at times employing such advanced technologies as DNA testing to trace previously undetectable bloodlines.

By William S. Powell, 2006

References:

Bonnie Ball, The Melungeons: Notes on the Origin of a Race (1992).

Jim Callahan, Lest We Forget: The Melungeon Colony of Newman's Ridge (2000).

Elizabeth C. Hirschman, Melungeons: The Last Lost Tribe in America (2005).

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Second Most Prevalent Race or Ethnicity Group by County in the US 🇺🇸 according to the 2020 United States census

by cactusmapping

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sources

Abuelezam, Nadia N., Awad, Germine H., Ajrouch, Kristine J., and Matthew Jaber Stiffler. 2022. “Lack of Arab or Middle Eastern and North African Health Data Undermines Assessment of Health Disparities.” American Journal of Public Health 112(2):209–12

Awad, Germine H., Hanan Hashem, and Hien Nguyen. 2021. “Identity and Ethnic/Racial Self-Labeling among Americans of Arab or Middle Eastern and North African Descent.” Identity 21(2):115–30

Arab American. “Dept. of Justice Affirms Arab Race in 1909: The Arab American Historical Foundation Home.” Arab American. Retrieved April 26, 2023 (https://www.arabamericanhistory.org/archives/dept-of-justice-affirms-arab-race-in-1909/).

Beydoun, Khaled A. 2014. “Between Muslim and White: The Legal Construction of Arab American Identity.” SSRN. Retrieved September 25, 2022 (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2529506)

The Federal Register. Federal Register :: Request Access. Retrieved April 13, 2023 (https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/01/27/2023-01635/initial-proposals-for-u pdating-ombs-race-and-ethnicity-statistical-standards).

Griffith, Bryan. 2002. “Immigrants from the Middle East.” CIS.org. Retrieved September 25, 2022 (https://cis.org/Report/Immigrants-Middle-East).

Haney-López Ian. 2006. in White by law: The Legal Construction of Race (Critical America). New York University Press.

Maghbouleh, Neda, Ariela Schachter, and René D. Flores. 2022. “Middle Eastern and North African Americans May Not Be Perceived, nor Perceive Themselves, to Be White.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119(7).

Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration,. 1997. “Recommendations From the Interagency Committee for the Review of the Racial and Ethnic Standards to the Office of Management and Budget Concerning Changes to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity.” 62 FR 36874, Retrieved September 25, 2022

Anon. n.d. “Middle East/North Africa (MENA).” United States Trade Representative. (https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/europe-middle-east/middle-east/north-africa).

Anon. n.d. “Middle Eastern and North African Americans May Not Be Perceived ... - PNAS.”

Fukuyama, Francis. 2019. Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. New York, NY: Picador.

Louise Cainkar. n.d. “MENA Americans: A Socially Disadvantaged Group.”

(https://www2.mu.edu/social-cultural-sciences/directory/documents/cainkar-mena-reports.pdf).

Mora, G. Cristina. 2014. Making Hispanics: How Activists, Bureaucrats, and Media Constructed a New American. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Aziz, Sahar F. 2020. “Legally White, Socially Brown: Racialization of Middle Eastern Americans.” SSRN Electronic Journal.

Blake, John. 2010. “Arab- and Persian-American Campaign: 'Check It Right' on Census.” CNN. Retrieved April 26, 2023 (https://www.cnn.com/2010/US/04/01/census.check.it.right.campaign/).

Krogstad, Jens Manuel. 2020. “Census Bureau Explores New Middle East/North Africa Ethnic Category.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 26, 2023 (https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2014/03/24/census-bureau-explores-new-middle-eastnorth-africa-ethnic-category/).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also! Lumping all southerners together as ‘homophobic, racist, white hicks’ is blatantly ignoring all of the POC southerners. For example, a majority of the country’s black population lives in the south.

I mean, we all know what the reason for that is, but it doesn’t change the fact that they’re here and a part of those despicable southerners yall hate so much.

And Texas in particular has a very high Hispanic population, again, obvious reasons. I went to a small high school in a rural town, very FFA and hs football focused, and the majority race/ethnicity wasn’t white, it was Hispanic.

Obviously there are so many other races/ethnicities in the south, but these two are the most prevalent (besides white, obvi) yet they’re conveniently ignored when the south is brought up.

Every time you disparage the south and write it off as ‘a lost cause’ you’re abandoning so many people you claim the southerners are oppressing. Queer and POC southerners exist, liberal/leftist/democratic southerners exist, even rational conservative/republican (og republican values, not MAGA and extreme values) southerners exist.

I’m sick and tired of saying where I’m from and being met with disgust and/or sympathy. The south is vast and diverse, maybe do a little bit of research before you decide it’s not worth helping us.

(I got the pictures from Wikipedia, but the reference is the census website with this cool interactive map if you have any interest in looking at the race/ethnicity distribution of the us)

yall have got to be more normal about Southern people and I'm not kidding. enough of the Sweet Home Alabama incest jokes, enough of the idea that all Southerners are bigots and rednecks, and enough of the idea that the South has bad food. shut up about "trailer trash" and our accents and our hobbies!

do yall know how fucking nauseating it is to hear people only bring up my state to make jokes about people in poverty and incestuous relationships? how much shame I feel that I wasn't born up north like the Good Queers and Good Leftists with all the Civilised Folk with actual houses instead of small cramped trailers that have paper thin walls that I know won't protect me in a bad enough storm?

do yall know how frustrating it is to be trans in a place that wants to kill you and whenever you bring it up to people they say "well just move out" instead of sympathizing with you or offering help?

do yall understand how alienating it is to see huge masterposts of queer and mental health resources but none of them are in your state because theyre all up north? and nobody seems to want to fix this glaring issue because "they're all hicks anyways"

Southern people deserve better. we deserve to be taken seriously and given a voice in the queer community and the mental health space and leftist talks in general.

59K notes

·

View notes

Text

Most U.S. businesses have only one owner

More than half of the businesses in the United States had a sole owner, consistently outnumbering multi-owner businesses each year from 2017 to 2021, according to an analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey, or ABS, which explores how reported business ownership varies by sex, race and ethnicity over time.

0 notes

Text

Canada needs a baby boom too!!!!!!

What is the largest demographic segment in Canada?

The baby boomer generation, comprising people aged 56 to 75, continues to be the largest in Canada, despite the fact that they are aging. The 2021 Census counted 9,212,640 baby boomers.Apr 27, 2022

https://www12.statcan.gc.ca › as-sa

A generational portrait of Canada's aging population from the 2021 ...

So Canada's second largest population is the Indigenous people. The third largest is asians.

This is the way it should've been in America. Where because the white population was the main population and then 🤔 The indigenous was the second largest population.

But what is America going to be? Going forward... In Canada there are very few Hispanics...

Just like america, the white population is very old.In comparison to other races. As you see canada, the white population average age is over forty.

What is the demographic shift in Canada?

The average age in Canada — 41.6 — dropped slightly, by a tenth of a percentage point, between July 1, 2022 and July 1, 2023. It was the first decline since 1958. Meanwhile, the number and proportion of people aged 65 years and older have continued to rise.Feb 21, 2024

https://www.ctvnews.ca › mobile

Millennials outnumber baby boomers for first time: Statistics Canada

So just like in America, it's very important to get longevity to stabilize the population... So, yes, white people I need to live longer!!!!

Canada has a better life expectancy than the united states!

How long does the average Canadian male live?

79.8 years for

Over the past century, life expectancy at birth in Canada has risen substantially to 79.8 years for males, and 83.9 years for females. These increases in the quantity of life say little about the quality of life.Apr 18, 2018

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca › article

Health-adjusted life expectancy in Canada

Canada/Life expectancy

82.60 years (2021)

United States

76.33 years (2021)

India

67.24 years (2021)

Canadians almost live five years longer, than Americans!!!!!

So the Hispanic population now makes up sixty-five million in the United States!

United States/Hispanic/Population

64.99 million (2022)

Here's the breakdown of the demographics of the Hispanic population in the United States.

The Hispanic population has grown significantly over the past decade, increasing from 50.5 million in 2010 to 63.6 million in 2022. This growth has been a major factor in the overall growth of the U.S. population.

The Hispanic population is made up of people of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race. In 2022, people of Mexican origin made up almost 60% of the Hispanic population, with 37.4 million people. Other large Hispanic groups include:

Puerto Rican: 5.6 million

Salvadoran: 2.3 million

Cuban and Dominican: Each 2.2 million

Guatemalan: 1.7 million

Colombian: 1.3 million

Honduran: 1.1 million

The states with the largest Hispanic populations are California, Texas, Florida, and New York.

U.S. Census Bureau

Hispanic Heritage Month: 2023 - U.S. Census Bureau

Aug 17, 2023 — 63.7 million The Hispanic population of the United States as of July 1, 2022, making it the nation's largest racial or ethnic minority — 19.1% of th...

As you see above between 2010 and 2022 The Hispanic population grew by 13.1 million people!

In population growth of the United States of every community that includes the white community, the Asian community, the black community, and the arab community, 71% of all growth in population in the United States is Hispanic!!!!

Census.gov

https://www.census.gov › 2024

Differences in Growth Between the Hispanic and Non- ...

Jun 27, 2024 — JUNE 27, 2024 – Between 2022 and 2023, the Hispanic population accounted for just under 71% of the overall growth of the United States ...

Now the Hispanic population is over 65 million in 2024. Since 2022 it's grown 2 million in population.

Census.gov

https://www.census.gov › newsroom

Hispanic Heritage Month: 2024

8 days ago — 65.2 million. The Hispanic population of the United States as of July 1, 2023, making it the nation's largest racial or ethnic

So over seventy one percent of the population growth in the united states related to all races is hispanic!!!!

So in 1970 The Hispanic population was 9.6 million. In 1960 It was 4 million. In 2024 it is 65.2 million!!!!!

four million

The U.S. Hispanic population has increased from four million in 1960, to 32 million in 1997, and the United States is now the fifth largest Spanish speaking country in the world after Mexico, Spain, Argentina, and Colombia (U.S. Department of Com- merce 1993).

https://www.tandfonline.com › ...

PDF

The Changing Geography of U.S. Hispanics, 1850-1990

So from 1960 Population size of Hispanics has grown by 16.3 Times in its size. It makes up currently 71 % of the population growth!!!! At that pace, they will be the majority sooner than anticipated..... The white population will soon be the minority..... But if you add the other minorities to them, the white population, we'll be even sooner, a minority..... So the government allowing sanctuary cities and allowing this continuous flow of legal and illegal immigrants into the United States, as well as allowing the growth of the l g b t q and the growth of abortion, and then allowing or promoting singlism against families, has totally shifted the demographics of America...

Latinos are more likely to get married in America, and more likely they have numerous children..... And if it doesn't change for the white race and other races, we will get primarily only Hispanic growth, making up right now 71% of all population growth in America. You don't understand how fast the demographics are shifting in America, it is unbelievably fast... And I watched the democratic party promote the l g b t q and promote abortion.... Hispanics have the highest fertility rate in America!!!!!

Not only do Latinos have children at younger ages than non-Latinos, they also marry at younger ages. Some 15% of Latinos ages 16 to 25 are married, compared with 9% of non-Latinos in that age group. The higher marriage rate for Latinos is driven primarily by immigrant youths, 22% of whom are married.Dec 11, 2009

https://www.pewresearch.org › viii...

VIII. Family, Fertility, Sexual Behaviors and Attitudes

Hispanics tend to marry and have children at younger ages than non-Latinos, but marriage rates have declined for Hispanics. However, there is a wide range of experiences within the Hispanic community, and fertility rates have declined in recent years. Here's a closer look at marriage and childbearing among Hispanics in the United States:

Marriage rates

15% of Latinos ages 16–25 are married, compared to 9% of non-Latinos in the same age group. However, Hispanic marriage rates have declined, with 26% of Hispanic adults ages 25 and older never married in 2012, compared to 16% of white adults.

Childbearing age

Latinos have children at younger ages than non-Latinos.

Family size

Hispanic families are larger than the US average, with about 3.8 people compared to the national average of 3.2. Half of Hispanic mothers have three or more children, compared to 40% of Black mothers and 33% of white mothers.

Fertility rates

Hispanic fertility rates are higher than non-Hispanic white and Black rates, even across immigrant generations. However, Hispanic fertility rates declined by 31% between 2007 and 2017.

Cohabitation

Hispanics are among the most likely low-income adults to be married or in a cohabiting relationship. 55% of low-income foreign-born Hispanic women have entered a co-residential union by age 20.

Multi-partner fertility

Multi-partner fertility is common among Hispanics, with research suggesting that almost 20% of women near the end of their childbearing years have had children by more than one partner.

The growing divergence between Hispanic and non-Hispanic fertility patterns is likely linked to the growth of the immigrant population. Latin American immigrants tend to have higher fertility rates and bear children earlier than native-born Hispanics.

Child Trends

Dramatic increase in the proportion of births outside of ...

Aug 8, 2018 — Women and men are marrying at increasingly older ages, on average (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Women's median age at marriage was 27.4 years in 2016,

America is truly going down the drain!!!!!!

The average age of the white population, as I said, is older than Canada's white population, but both are over 41. This means the white population in Canada and the United States is dying... It is dying quickly....

United States/White People/Population/Median Age

41.9 years (2022)

The average age of white people is over ten years older than the other races..... And the Hispanic population is even getting younger with daca...

94% of DACA represents his Hispanic Youth...

What percentage of DACA recipients are Hispanic?

The vast majority of DACA recipients are Latinx. In 2020, 93.5% (772,516) of the 825,998 DACA recipients hailed from Latin American countries. Mexicans constituted the largest Latinx group at 78.7% (650,353) of all DACA recipients.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov › pmc

COVID-19 and Latinx Disparities: Highlighting the Need for Medical ...

Boundless Immigration

https://www.boundless.com › chall...

Challenges and Opportunities Facing DACA Recipients

A report by Boundless looks at how DACA recipients have benefited from the 2012 program, as well as the challenges they still face in 2022.

That's why the student population in California is almost 75 %....

Nearly 40 percent of school districts have a majority Latino student population—and in half of these, 75 percent or more of students are Latino.Oct 3, 2018

https://csba.org › CSBA › Files

FactSheet October 2018 - Latino Students in California's K-12 ...

Of the six million K-12 students who attend California public schools, just over half — 3,360,562 million (54%) — are Latinos

https://www.csba.org › media

FactSheet October 2016 - Latino Students in California's K-12 ...

… school-age population in America found New Mexico (61.1%) has the highest percentage of Hispanic/Latino people ages 5 to 18, followed by California (52.2%) …Oct 11, 2022

https://www.usatoday.com › news

Latino student population in the US is booming. Are schools ...

So the demographics in America have shifted incredibly fast!!!!! 🤔 It took hundreds of years to build it, and in only 60 years it changed the demographics...

0 notes