#Przybyszewska

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A List of Relatable Things Stanisława Przybyszewska has done/written:

Studied philosophy at a university for one semester until "nervous exhaustion forced her to abandon her course"

Dated her letters by the French Revolutionary Calendar

Was known to often be humming La Marseillaise

Called Camille a twink in her play (okay, to be fair she used the word 'ephebe', but I'd argue that is as close to twink as you can get in the 1920s)

Worked at a leftist bookstore (and was subsequently arrested for it)

Took a stray cat from the street which at one point "was the only creature keeping her company"

Complained in at least two letters spanning over 3 paragraphs about a group of loud people playing football near her windows ("For the past forty-five minutes they have not been roaring, they have not been howling, they have been simply shrieking (...) like animals being slaughtered. Screams of that sort must be frightfully tiring for the vocal chords.")

When she wrote "I must write in order to be able to think. As a matter of fact, I am a remarkably unthinking person. Well, of course, that holds true too when I'm talking. But if I don't have either paper, or a human ear to listen to me, then I'm no more of a philosopher than a cat is."

1 + 8 - since I study philosophy at uni & am currently working on my thesis, these felt particularly relatable. I'm not more of a philosopher than a cat is definitely hits. Kind of want to put it in the preface.

2 + 3 are things I may have done myself before (okay, not letters but a diary, but it counts, right?)

7 - as someone who struggles with misophonia, I felt s e e n.

4- I'm sorry guys, I had to. But as someone who frequently asks herself "Are you really calling 30-somethings who have been dead for more than 200 hundred years twinks?", this felt like a vindication of sorts.

Also- I feel kind of conflicted about making this types of Tumblr posts about her since her work is really profound and serious and I have a sneaking suspicion she would have not appreciate them. At the same time, she has been living in my mind rent-free for the past week and this is a way to cope I guess?

SOURCES: 1. A LIFE OF SOLITUDE: STANISŁAWA PRZYBYSZEWSKA Author(s): JADWIGA KOSICKA and DANIEL C. GEROULD Source: The Polish Review , 1984, Vol. 29, No. 1/2 (1984), pp. 47-69 2. BBC Reith Lecture Three: Silence Grips the Town. Dame Hilary Mantel, 2017 3. Stanisława Przybyszewska: A Brilliant Playwright Preoccupied With Revolution. Alexis Angulo. Retrieved from: https://culture.pl/en/article/stanislawa-przybyszewska-a-brilliant-playwright-preoccupied-with-revolution 4. Przybyszewska, Stanisława. 1930. The Danton Case.

#french revolution#frev#frev community#stanisława przybyszewska#przybyszewska#the danton case#frev memes#history#literature#also go read the articles they are excellent#but obviously incredibly sad#camille desmoulins#20th century literature#misophonia#1700s#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#academia#it actually took effort not to put “daddy issues” on there#I guess it's now in the tags#oops#hall of fame

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

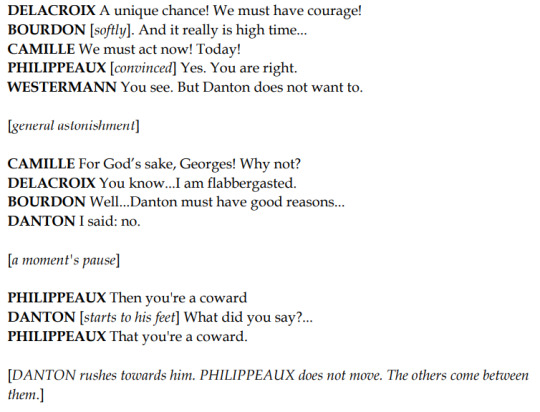

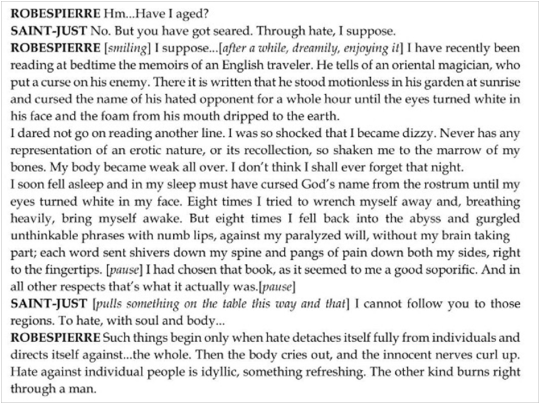

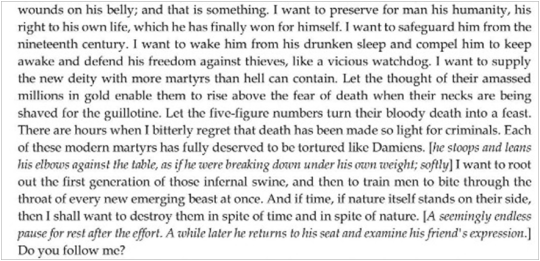

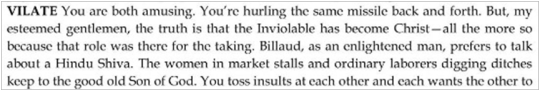

Philippeaux is the real chad here.

-from "The Danton Case" by Stanisława Przybyszewska

#the danton case#Stanisława Przybyszewska#Przybyszewska#frev#danton#philippeaux#desmoulins#l'affaire danton#french revolution

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Sir,

Mr Augustyński has kindly informed me that you have read my one-act play [93] and decided that staging it is impossible. I'd like to point out that if Mr Augustyński asked you to accept the play - as his letter seems to indicate - the idea certainly wasn't mine. I requested him to find out what had happened, not to promote the play.

I'm not at all surprised that you haven't sent back the script to me yet - I'm not surprised, but I won't tell you the thoughts I have about you as day after day I confront an empty mailbox.

Stanisława Przybyszewska, Letter to Leon Schiller, 7 Dec 1927

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you have time and haven't done so already, I highly recommend you read this summary of Przybyszewska's The Last Nights of Ventôse.

It puts it better than I ever could, plus it's written by a native Polish speaker.

I'll just quickly add that to me, there's hardly a better proof of the fact that people have always been into the same things, and quite often, the trends we think magically appeared twenty years ago have been with us for centuries.

(all I need now is for archaeologists to discover stone tablets with someone's Gilgamesh/Enkidu fanfic)

My thoughts on “The Last Nights of Ventôse”

Keep on reading for info about probably the first Saintmoulinspierre fanfic ever.

It’s windy and cold outside. No wonder, it is the last night of Ventôse after all. Tomorrow night, Germinal an CCXXIII starts and I hope it’ll bring better weather. Anyway, I’m not gonna be original - it seems like the perfect time to rant a bit about Stanisława Przybyszewska’s “The Last Nights of Ventôse”.

My edition is probably the only available in Poland, based on Przybyszewska’s manuscript, released many years after her death. Pages: 165 including the preface, chapters: IV, heartbreaks caused: countless, dammit.

There it is, the ultimate Maxime/Camille fanfic. And probably not what one would expect. It is slashier than some frev tumblr drabbles. We are not interested here in historical accuracy. Just Przybyszewska’s story. An 80-year-old fanfic. And believe me, even if something seems very OOC in Maxime’s or Camille’s behaviour, the story itself is extraordinary and can produce a friggin’ Seine of tears.

Begins with Maxime’s illness - feverish nightmares, anxiety attacks and doubts concerning the inevitabe - Camille’s arrest and execution. There’s also a short conversation between Maxime and Eleanore (Leo). She generally talks about her feelings for him and how he has changed. He, on the other hand, rejects her and regrets that he gave in and used her affection once. A short exchange that always makes me smile: “- Let us sit. - No, Leo. Or if… Then, three paces away from each other.”

Later, Maxime has even worse nightmares and premonitions, so he sends for Camille. Our dear journalist is playing cards with Danton at his own house and he is clearly not in a good mood. “- Camille, you didn’t even notice that you lost. What are you thinking about, boy?! - About you, my love!”

Camille is a little meanie; he can’t really tell why he is angry with Georges but oh he is, and he is almost furious (later it’ll become clear that it’s because of a very serious fault of Danton’s - not being Robespierre). He speaks those words with a mocking, mean tone, yet sweet at the same time, pretending a young damsel.

In this glorious piece of 80 years old fanfiction, Camille is the cutest, most adorable, sometimes really, really mean and childish trashy-tempered baby ever AND he is wonderful that way. Maxime later calls him all kinds of pet names, such as: child, Cami, little flower, boy, lovely child, genious boy, poor thing, little Camille, little one - but he is cool and composed while Camille loses his temper all the time, but I’ll get to that.

Camille doesn’t want to see Maxime but when he hears of his illness, he goes to him immediately. When he sees him… That fragment is very hard to forget and heart-wrenching. “Camille’s love bursted with thousands of flames from tips of his nerves, hissing with pain. - Desmoulins, first of all, you must forget for a while that our acquaintance is a private one. In other words, you have to look at me as if you were looking at a colleague or at a neighbor, not an object of your… Feelings, you know which. Will you manage? - No - replied the guest, his voice hoarse with excessive strictness.” *the sound of my poor shipper heart exploding into million aching pieces*

Later, there’s a very harsh dispute between them about Camille’s situation and his trust in Danton. I intend to translate the whole story in summer when I’m done with my thesis, so, in short: Maxime is cold and composed while Cami (what a cute nickname!) is in despair. Camille is furious with Maxime as he’d rather stay unaware of his very probable death drawing near, he practically panicks and yells a lot. Maxime in his thoughts admits (cruelly!):

“It is, after all, a soul fragile and frail as threads of glass; oh, I should have left him in peace, he would suffer only for three days, later, death - well, it’s too late now. Oh, Camille, Camille, poor thing - what a favor I’ve done to you!”. And later: “Their mutual feelings were stronger than frienship - it was simply love on both sides, Camille’s with a strong dose of admiration. Nevertheless, the older’s feelings were probably even stronger, though they didn’t bind his existence totally.” (then, a long description of Maxime’s feelings for Cami - very caring, almost maternal, “filled with nervous anxiety and insatiable tenderness […], hidden carefully”). “For the last six months, Camille inflicted a blow after blow, deliberately, skillfully, aiming perfectly at his weakest point. […] Love of this kind is so bereft of dignity - the more the beloved child teases, the more precious he becomes.”

Then Maxime asks about why he is so stuck on Danton and Cami answers that he is only at Georges’ side because Maxime used to be so cold and composed around him, barely noticed when Camille was not at his side, “forgot about [Camille’s] existence”. The more cold and indifferent Maxime was, the more Camille was drawn to him, but eventually he had enough. Danton was the perfect negative of Maxime and actually appreciated Camille, praised him a lot. Cami missed Maxime anyway.

Maxime asks a lot of questions about them (jealous much, M?). Then: “- Do you even know this man? Are you sure of his sincerity? […] - Well, no - except for when he is drunk. Then, it seems, he likes me with no reservations or calculations. These times, he practically cavorts over me. Draws me close, embraces, kisses, boasts… As if I were a woman. Robespierre suppressed a groan. He wriggled. - Do you like it? […] - Why do you ask? How’s this relevant? - Very relevant, but I’ve already guessed.” Fanfiction much?

Maxime talks to Camille about how Danton is using him and Camille realizes he is right. He is in such shock that he jumps to his feet. “Don’t touch me”, but Maxime does anyway, he holds him by his arms and doesn’t let him go. His touch eventually comforts Camille, but: “- What do you want from me? Let me go at last! - I won’t. Break away if you want to. […] - You are stealing away my life. […] You grasp another’s soul with your claws. How dare you? - By the right of the stonger one - whispered Robespierre”.

Fanfiction MUCH? Just wait until… Right, then Camille is lost in his thoughts for a few pages - his anger with Danton and adoration for Maxime clearly visible. Eventually he drops at Maxime’s feet, emotionally exhausted. He’s so lost in his adoration that he actually kisses Maxime’s foot (fanfiction very f*****g much? Yeah it gets slashier!).

Maxime of course wriggles out and acts coldly again (but anyway he describes Cami in his thoughts as “a handsome boy, cute, […] absolute beauty” - they should just get a bed and there is an available one, come on!).

Camille is heartbroken. Rejected again. He has to know why Maxime cannot stand his touch. He even says that had Maxime acted differently, it might’ve saved Camille, for he would abandon Danton at once and do everything possible to convince everyone that he changed sides. He would save his life if Maxime had any use for him. Well, he wouldn’t even turn to Danton in the first place, were things different. This part of their conversation is really interesting. I have no time now (unfortunately) to translate Maxime’s rant about male/male love, but I’ll try to do that tomorrow, it’s really interesting.

Camille’s reaction to it? He is wounded, a blow right in his adoration. He thought before that Maxime doesn’t understand that kind of feelings, but after hearing him out… For Cami that sounds as if Maxime knew these feelings all too well, but Camille was not the one Maxime had those feeling for. Even tough he felt a pang of hope at times listening to it all, but he was quickly disillusioned.

Maxime is almost certainly speaking about Camille (or is he? *ekhm* Antoinevisitshimlater *ekhm*). Cami is so furious, poor thing. “Why did you tell me all of this? […] Haven’t you done me enough wrong already?”.

Maxime states that as a revolutionary he cannot waste time on personal matters (“I do not have a private life”) and does not like the fact that Camille is willing to offer himself to someone to the point of sacrificing his own freedom. And Maxime is very uneasy about the physical manifestations of Camille’s feelings, they embarass him.

Camille: “I have to have the right to embrace my friend whenever I want to without feeling his muscles turn into a hostile armour under my touch. I have to have the right to kiss him, for such kiss is what makes two beings one.” Right in the feels, Cami, right in the feels. But you can do better. “All it took was giving up just for a while that what your inhuman pride requires. To bear calmly one innocent kiss, even the pope allows that. To bear the fact that for a one short while you are only a beloved human living in a human body […] I’ll remeber your pudeur virginale even in the another world, if not after falling rightously asleep in Sanson’s two baskets.” I want to hug him and I need a large box of tissues.

Camille tries to leave (not for the first time) but Maxime stops him and even embraces him as tightly as he can. Maxime scolds him for being childish and reckless. He admits he loves him and acted that way because he is ill and everything irks him. He reminds Cami how much he’s done for him even after all Camille did to harm him. He speaks of Camille’s unstability, how he’d run to Danton’s side and that even now Maxime risked so much to save his dear friend.

Sweet, rash Cami of course thinks Maxime is mocking him. “-How does it change anything, that you actually care for my life, since you won’t even let me near you?! - So you have wasted your life, your talent, and now you’re practically pushing yourself on the gallows and all this scrupulous destruction for an embrace rejected? To die of longing for a kiss, what a beautiful death!” Sorry, but were I there, I would stuff Maxime’s mouth with jam tarts so he’d just shut up. “- But there, if it’s the only cause, kiss me all you want, I won’t interrupt you. Kiss me until you get bored, that is, if you won’t get burned.” Oh and there goes all my wrath and all my shipper feels and I practically squeal because of that passage. Then I actually have this sudden urge to hit my head hard with something heavy. Maxime, you... You.

“-How… D-dare you!!! - he whispered, his voice trembling. - So no, then? You won’t take the opportunity to have something to remember in the other world? That’s a pity, I’d actually like to try, you’ve made me curious. Maybe it can actually give pleasure, and I’m curious because until now the sight of two men exchanging caresses seemed amusing to me.” Maxime, please, please take your curiosity elsewhere or stop with all this indifference; boys, cease the angst and heartbreak and make use of the bed. Please. There is one available and the room is cold. Ekhm.

Then Maxime actually scolds him again and starts to talk about politics (not exactly the right moment, huh, M?). In his opinion, Camille is selfish since he concentrates his thoughts on his personal misfortune when the future of the Republic is shaping. He is so concerned for his own unstable future that he eventually asks Camille: “- If it’s me who dies, not you, can you swear to me that you will contact Saint-Just? Camille rose. - Saint-Just… Why him? - He is the only leader except me, he is the only one that understands my thought and wants what I want; he is the only one who can succeed me. - And me… I’d be to serve him? - […] Not him, idiot, but the oppressed people!”.

Poor Cami, you sound like a jealous schoolboy. But whatever. The fragment about contacting Saint-Just is tricky because of a Polish word used here that can mean both “contact” and “reach an agreement” - it is not clear from the context. Oh, they would certainly not reach any, Maxime, come on. You know them.

Maxime again begs Camille to save his own life while he still can. Camille is desperate to do anything to make Maxime feel better since his fever is getting worse, so Camille agrees. He feels helpless and he’s so cutely concerned for his friend… In the end they simply say their goodbyes to each other because they are both gravely tired and Maxime feels worse and worse with every minute.

Maxime spends his next day waiting for any news or rumours about Camille’s decision. We all know what happened next. Camille condemning Maxime again. Maxime’s so shocked that he even contemplates suicide thinking it could save Camille’s life. Eventually he realizes that there’s nothing more that he can do and he accepts the necessity of arresting Camille.

Then voilà, Saint-Just appears at last. He visits Maxime when it’s already dark and they can’t see each other. But they hold hands. “Their hands found each other without hesitation, as if they were driven by a mutual attraction. They both fell silent in this voiceless yet ardent meeting. The hand of the guest, still cold after a long walk in this humid night, a bit larger, much stronger at the moment, clasped the hot hand of the tribune in a lenghty squeeze. This contact had a soothing effect on the other. It made him feel at peace, reborn.” Ekhm, Maxime? Ekhm? Wasn’t that you who teased Camille with cold indifference not so long ago? Ekhm? But okay, keep holding Antoine’s hand. We shippers are definitely not complaining. Just so you know, Camille reacted to YOUR touch exactly this way.

Maxime reveals to him his ultimate decision about the Dantonists and Camille. Antoine offers to deal with the matter on his own because it’s too personal for Maxime, and also he is concerned for Maxime’s health. In the end, Maxime insists that he is perfectly able of handling it by himself and decides to get up… Only to get dizzy and fall straight into Antoine’s strong arms. Yes. Right. That’s exactly what happens. Antoine even calls him “my dear” as he helps him to come around.

Then we have a very isteresting description of Saint-Just when he lights the candles and the “impenetrable darkness” is no more. How does Maxime see him? “A while of silence. All the candles were burning. Behind them, lit from underneath, a face of an archangel, his features of an inhumanly beauty, delicate as a woman’s but of the nobleness typical for men. Big violet eyes, a marble-white face framed by black hair reaching his jawline. His back straight, slender in his tighly fastened suit, Saint-Just awaited in silence.” I do not exactly imagine him that way (violet eyes? Pretty, though) but the description is interesting anyway. Maxime, are you crushing? Are you? Even despite all that happened, Maxime actually has a half-smile on his face when he looks at him. Okaaay. And Saint-Just actually calls him in his thoughts “beautiful in this deathly paleness, so gaunt, his eyes burning”.

And then: “He [Saint-Just] said even, breaking the feverish silence: - No one in France has a will like yours. No one’s thought is as vital as yours is. You are - the only One.”

After a while Maxime goddamn faints again, and guess where he ends up again? In Antoine’s arms. Yes, right. He even ends up laughing loudly and it is described as a sincere laughter but to me, it’s still hysterical. As if he tried to get rid of all his anger and gloom that way. “[…] Saint-Just turned towards him and embraced him with his other arm […] they closed each other in a tight, silent, loving embrace.” In the end, they just leave for the Committee meeting.

Yeah. Gosh. Fanfiction much.

But isn’t it entertaining? Most probably the first Saintmoulinspierre fanfiction ever. For me, that’s certainly heart-breaking. Camille is absolutely adorable in his rashness, moving the reader to tears. As for Maxime, I wanted to pinch his side while reading this very, very often, but at the same time it was impossible not to feel sorry for him and relate to each and every of his words. He’s a very mysterious figure here, I tell ya. Antoine has this dangerous yet charming vibe, come on, even Maxime fawns over him.

I have to add that while Przybyszewska in one of her letters wrote that it’s actually possible that there was something between Maxime and Camille, she does not believe that there could ever be something between Maxime and Antoine, they were more like brothers in arms or soulmates (I don’t really remember well, I need my own copy of her letters and I need it badly). That doesn’t mean she doesn’t ship them, though, as it’s pretty visible in “Last Nights” and her plays.

Przybyszewska practically admitted (probably in the same letter) that she has a certain kind of a soft spot for homosexuals. Citoyens, that’s the 1930’s term for “hello, I’m a slash/yaoi fangirl”. Oh girl, you made it visible.

I was born and grew up in a city in which she spent some longer period of time, in a place I often visited, so there’s probably a Saintmoulinspierre germ in the air there, even after all of these years. And oh did I get infected.

Thanks for reading my thoughts on a 1930s fanfic by a Polish girl who, as Mantel said, “died on Robespierre”. There are many perks of being Polish and being able to buy a copy of this and reading this is certainly one of them.

It’s almost 2 a.m. here. Ventôse is ending, Germinal soon begins but even after the cold winds cease, there’ll be other things to remind me of certain days from years long gone by. I’ll be still thinking about what that story did to me. I can’t get it out of my head since I’ve read it and finally got to share some of it. Even though it was impossible to contain in this note all that is there. Only a full translation will.

Thank you again and stay on the Saintmoulinspierre ship for it won’t ever sink. Have a good day/good night and don’t mind the cold winds.

#so worth a read#stanisława przybyszewska#przybyszewska#The Last Nights of Ventôse#frev#french revolution#camille desmoulins#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine de saint just#history#history memes#the danton case#fanfiction#literature#polish literature#frev community

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

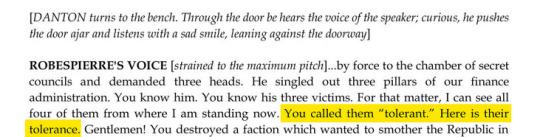

Stanisława Przybyszewska - Thermidor

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illustrating the Danton Case + Thermidor

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've suddenly remembered that i have a finished paper about Przybyszewska and how micro- and macrohistory function in her works (the paper was mainly an analysis of one of her short stories, the one about september 1792). i was wondering if anyone would be interested in me translating it to english and publishing it? it's not that long, about 10 pages. lots of Ginzburg and Foucault. ???

#stanisława przybyszewska#frev#french revolution#university#accidentally entered unstoppable academic weapon mode and i now possess an enormous amount of power so i remembered about this paper too

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

reblogging this post as well because it includes a great analysis of Louise Danton.

Sure, Louise as a literary character in Przybyszewska's play that is just based on the real woman, but I'd say it is still important, especially if so little is known about her as a historical figure.

And the character breakdown of Lucile and Éleonore is obviously worth reading as well.

It is absolutely doubtless to me that Przybyszewska had a problem or two when creating and describing/explaining her heroines, problems, which do not seem to occur when men are concerned. I do think, however, that in The Danton Case (not to mention her prose) she managed to build female characters with distinct personalities, which is more than can be said of some other classics.

Going back to the way sexuality is being portrayed in The Danton Case, I honestly think that in order to be able to discuss it with good sense one needs to understand and respect asexuality. I am being somewhat in opposition to what Monika Świerkosz proposes in her article on the subject, I do not think that Przybyszewska's women "deny themselves any pleasure" when they choose ascetisim or politics, because one cannot deny themselves anything if one doesn't believe in the existence of such "pleasures". I feel that in this very personal aspect of a human life, Przybyszewska was drawing from her own experience more than on any other occasion: the pleasures of life was, to her understanding, ascetisim/celibacy and politics, and choosing them in no way indicates negating oneself. "It would appear then Przybyszewska realises that "a full lack of the element of desire" in regards to the world is a more radical violation of the norm than homosexuality or perverse sex; it is something for which there are no words". With this though, I agree in fullness. And so, all of Przybyszewska's heroines seem to share one quality, that is – they resemble ancient virginal goddesses of some sort, not exactly because there is an aura of divinity about them, but because they do not seem to be fully, wholly human. This "virginal" quality has little to do with their sex lives, and more with the desire for autonomy on all levels of being (physical and spiritual, not to mention – mental). I reserve for myself the singular right to my life was Przybyszewska's credo and arguably the strongest, firmest phrase she has ever coined. And this is the energy she breathed into all three women in The Danton Case (excluding, I must add, the few appearing in the very first scene; but most of the time no one reads it anyway); the level of intensity and the direction of this desire varies, but it is always present. I would like to present this in three parts, each relevant to one of the characters of the play.

Eleonore is evidently Przybyszewska's favourite, if only because she's devouted to Robespierre – but I think she is also modeled a lot after Przybyszewska herself, not just in terms of this undying devotion, but hers is the type that is later reproduced in many short stories (which, unlike the plays, are filled with women of different kinds to the brim), which makes it obvious she was armed with qualities the author found appealing. That's why it's so strange that Przybyszewska has essentially created two very different Eleonores: one in the play, and one in The Last Nights of Ventose. The first one is definitely meant to be depictured as elder, she has an ironic sense of humour and is very decisive and firm, despite making allowances for Maxime and his rigid rules. The second one is definitely younger, has a hard time grasping at irony, is timid at times and yields to Maxime rather than moves not to be crushed by his wishes. For a reader – probably any reader – the first one is definitely more appealing, more fun to read – more complex even, and given a will of her own, which makes her stand out among the majority of the play's characters (for example: the other members of Comsal have less distinctive personalities than her).

There is a weakness in her, though, or at least the way I see it: she does not feel natural. I'd give anything to have a strong, believable female character in that play, but Eleonore is... not it. Her sense of humor, her quips, her behaviour when she's constantly being met with disappointement don't read real in my eyes, it reads as something "too cool to be true" – therefore, it probably isn't. She has some occasional moments ("You viper!" comes to mind) when naturality shines through her words, but it isn't 100% of the time.

How does Eleonore express her femininity, does she do it at all? Well, yes and no. She seemingly willingly puts herself in a position, which is stereotypically feminine, that is to say: but an accomplice to the man of her life, putting herself second and him first, occupying herself with stereotypically feminine tasks of housekeeping and taking care of others (it is worth noting that these are all traits that have potentially negative quality about them, they can easily be distorted into degradation). In the same time, she assumes the air of equality when talking with Robespierre, is deeply interested in politics and holds her own when Maxime tries to dismantle her attempts at reaching out to him. She is also decidedly "virginal", if we are to reach out to the terminology from before, taking a firm stand against motherhood, even expressing a certain amount of contempt for the idea; this is, however, where the virginity of hers ends, because she is otherwise a very sexual person. To be honest, the way in which she is being presented to the audience – literally sliding down Robespierre's torso and kneeling to him, gripping tightly at his knees and very visibly trying to give him a blowjob first thing she sees him well after weeks of illness – is rather disgusting, not necessarily because sex is (a disclaimer, which could probably be put at the beggining of this post, since it's a bit relevant: OP is asexual and has nothing positive to say about sex), but because this is how she imprints in the audience's minds. No feigned irony of hers, no clever remark will be taken as just that, all will be tainted with the image of this otherwise sensible woman degrading herself for a scrap of attention from someone who says bluntly that she is indifferent to him (and as I always underline, in the universum of this play, Robespierre only ever speaks the truth, at least in the spiritual/mental matters, so we know he means it).

For the reasons listed above, I see her as both womanly and manly, if we could call it that. Monika Świerkosz, a Przybyszewska scholar, said that "[...] in Przbyszewska's prose works womanhood and manhood stand in a binary oppsosition to one another, and neither is an enclave of happiness of identity." – I don't think it's strictly accurate. To my understanding, the phenomenon relies on Przybyszewska not relying on any kind of deeply rooted gender stereotypes in creating her characters. It's not like she's taking a steretypically understood masculinity and simply sprinkles it over her heroines! She is operating in the fields of transsexuality, demisexuality and nonbinarity (not exactly in the convential meanings of these words, but there is something to it). I find it hard to put in words, perhaps the thing I want to say is mostly that her characters as a whole don't fit a clearly defined niche and live their own lives at the outskirts of customarily understood gender instead of being solely mouthpieces for the author.

Going back to the concept of virginity, which is especially relevant in Eleonore's case (and especially the one from TLNoV), when it comes to the woman who is always in Robespierre's orbit, it is being contrasted with his own attitude and thoughts on the topic. She's the one begging him to reconsider his stance on the subject, she's the one trying to sneak up on him and shutter his defenses (which is, again, explored and explained in a more detailed way in the novel). It is worth mentioning, though, that while she is constructed as a somewhat sensual person, she is still babyfied about it, there are narrator's remarks about her naivete and innocence in this regard, despite some – very limited – sexual experience. For this reason I'm on the fence in deciding how exactly is this trait used in Eleonore's case. Is she meant to be seen as more mature because she's had experience, knows what she wants, and she's willing to do a lot to obtain it? Or is she meant to be seen as more silly and childlike, not understanding her own desires to the fullest? Are we to admire her or pity her?

Willingly or not, Eleonore becomes an embodiment of a very important characteristic which Przybyszewska uses extensively in her short prose works. If she, for whatever reason, cannot achieve the fullfilment of what she's striving towards, she then personifies ascetisim. And ascetisim is the clou of all of Przybyszewska's life. At the heart of matters, she doesn't care for either virginity or motherhood (in this making equal two things treated usually as polar opposites) as long as ascetisim remains in the world. It is for Przybyszewska a synonym of both "autonomy" and "agency", two ideals powering her life (though, might I add, there is a bit of falsity in this, for her own autonomy relied on being dependent on the financial help received from others and she gave up an almost full autonomy – which could be found in providing for herself – in exchange for the absolutely full autonomy in just one aspect of her life: writing).

I have mentioned before that Eleonore doesn't seem to be entirely natural in her behaviour. Przybyszewska was to a very large extent fascinated by futurism (for her the Revolution, as well as any potential revolution, was worth taking notice of because it brough in the new), and a big part of european futurism was its own fascination by machines. While I, personally, disagree with the notion that machines and robots become a synecdoche of a man, perhaps it really were so for the futurists. A machine ceased to be something completely external and foreign to the humans, it begun to be more of an external part of a perosn's body, a complement of sorts. I think this is why "female" robots, or in general any mesh-up of robots and women may seem more natural to us: they usually already have this one additional organ, and through it, they can produce more humans. And this is what ties back to the idea of Przybyszewska's female characters being sort of divinities, but in a cold, rigid (ascetic!) sense of the world.

For none of them is exactly warm. Moving from Eleonore onto Louise,we can see she's even colder, and not without a reason, there is a cause for why she is the way she is – standing as a contrast to the fleshy, "humane" Danton she couldn't be anything else. What I like particularly well about this portrayal is that it's never shown in a negative way (and not even because Danton is... I think Przybyszewska's own sad experience with sexual abuse played a part in that). For the reasons of the sexual abuse she underwent, Louise is also portrayed in a decidedly virignal light: the things that have happened to her do not define her. She is so in a very different way than Eleonore, she weaponizes this part of her life which is seen as stereotypically connected to womanhood, while being detached from sensuality: motherhood. Her pregnancy is the first respite from Danton she has and she clings onto it, not even in a desperate way, it's cold, calm and calculated. Her young age also serves the same purpose, it detaches her from the customarily understood femininity, it makes her less "womanly" and more "girlish". I don' think I speak only for myself when I say the audience would have a hard time imagining Louise actually becoming a mother; for her this is only a weapon, a means to an end and that is because she is not yet fully formed woman, in a sense.

There is a thing about her and her appearance in the novel and how it presents to us that begs a moment of distraction. In his movie, Wajda took care of presenting both Eleonore and Lucille in a visually masculine way, but he did nothing of the sort with Louise (he barely included her at all, but even so, she was over the top feminine in visual aspects). I don't think this was a good move on his part, in all honesty, it creates a division between her and the other two heroines, while there should be no such thing. I think all three serve a much more unanimous role than what he'd have us believe and this text is partially meant as an explanation why.

So Louise, for obvious reasons, is rather disgusted by all matters pertaining to sex (and that is seen not only in her interactions with Danton, but also with Legendre, that's why we can safely assume so at large). She is shown as strong, strong-willed and intelligent, which is another thing pointing us in the direction of her mentality of an "ancient virign" (I use some terms liberally, but I hope I convey the meaning behind them well enough). She was stripped of all of this in the movie, and this time it was sadly yet another rung on the ladder meant to elevate Danton. In order to powder his face to make him presentable, Wajda had to exclude Louise from the movie and make her a prop rather than a person. I dare say he, as a man, saw Louise as a "anti-woman" because of her attitude and his artistic choice was the nearest antidote; but he was wrong. Przybyszewska's heroines aren't fully human, yes, and aren't fully womanly – but they aren't "antiwomen", they are "superwomen" (in the same sense of the word as "superlunary", for example). They are beyond femininity in many aspects and the only reason why we are even discussin them in any terms pertaining to gender and womanhood is becuase a. I have no other language to do it and b. these things exist in the same reality, I need to underline the fact these heroines are "superwomen" only because they, too, have an idea of what "a woman" should be and exist as a some kind of response to it. Louise, for example, has no need for it, because the root of her problems lies in the lense of femininity through which Danton sees her and if it weren't for his demise, he would continue to threaten her in a sexually abusive way, tied closely to her "role as a woman" (one of the last things he says to her is an accusation of sexual nature regarding her).

Lucille's response seems to be a lot less firm (if not: less aggressive) because her environement didn't condition her to be so fully womanly in the first place. A sfar as husbands go, Camille was a much better one than Danton: just as childish, but treating Lucille not only as a beloved, but also as an equal. This allows her for space to grow as her own peson, and if this person includes affirming her femininity (for example through being a partner to her husband, in being a tender mother, in caring for Camille when he needed her most, in loving him to the point of madness) we can rest assured it is her own choice and part of her agenda. She is not weaker than Eleonore nor Louise, she just has more space to breathe. And like Eleonore, she is deeply interested in politics, and not only that, but has a better graps of it than Camille does, connecting the dots quicker than he would. I can't say if this is a part of characterisation of the women in the play, to show them as autonomous beings capable of political thought, or if it was simply a way of gentle reminder every now and then to the audience that politics permeated the universum of the play so thoroughly everybody in it knows their way about it (it is worth noting that Louise also understands the then political troubles, but unlike the other two, she consciously cuts ties with it, for this is yet another thing which belogns to the realm of Danton, and she doesn't want to be further tainted by him).

I like the fact that Przybyszewska included a scene between Lucille and Louise, especially because it was not strictly necessary for her to do so. It is another facet of her craftiness and intention regarding the way women are being portrayed in the play, because while it exists on the structre lied down by the political plot, the most important things that an audience can draw from the scene are: while Lucille loves Camille greatly and will do anything to save him, it is not necessary for the plots/the overall theme of the play for her to act so (as proven by the indifferent Louise, who is in no way villified in her choice) and Louise is not evil as a character, because she doesn't shrink her responsibilities as a decent human being: she doesn't want to help Danton, specifically, but she provides Lucille wih a logical and pretty good way to attempt what she wants to do. Perhaps this is too little to call it a sisterhood between them, but I find this portrayal contrasting attitudes reassuring.

#stanislawa przybyszewska#stanisława przybyszewska#eleonore duplay#lucille desmoullins#louise danton#the danton case#sprawa dantona#literary analysis#frev#french revolution#women's history#1700s#frev community#frevblr#literature#przybyszewska

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have just finished reading the Danton case. I was very moved by it. It is easy to understand why many consider it a masterpiece of frev literature. But I got the (inappropriate?) impression and sympathy that was completely contrary to the author's intentions, so I'm not even sure I should write about it here.

I must confess, I felt sympathy for Danton. As a lonely, hurt for a long time, painfully sad person, he is much more sympathetic than any of the "manly" hero of the Third Republic (or Wajda's movie). (This is one of the reasons why I like LRF more than other movies, but I'll save that for another time).

How strange that he was created by an author who loathed him.

I have a lot more to write about, but haven't decided yet if I'm going to post it or not. (It was a constantly moving read, finding similarities to historical facts that I'm not sure the author knew, and to movies that have nothing to do with either frev or her, etc.)

#and I think he certainly loved Camille although it may not have been ideal or appropriate love (and that makes me sadder)#I shouldn't complain if Przybyszewska beat me up

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guess who's just acquired the recording of a stageplay of Przybyszewska's "Thermidor" from 2015 👁👄👁

#I can only access it for a month but I'm already thinking how to download it#I had to lie a bit to get it buuuut#a friend of mine who specialises in theatre studies advised me to do so#so i guess it's pretty common to do it#i probably won't send it to anyone as long as I can't download it for good#then we'll see#frev#thermidor#stanislawa przybyszewska

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Przybyszewska was the original Robespierre fangirl, pass it on

#french revolution#frev#frev shitposting#everyone probably knows this already and I am just finding out now#but I needed to share#also I'm technically 1/8 Polish so I can claim kinship right#maximilien robespierre#Przybyszewska#history#making it my life mission to stan women writers

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

#yes the indulgents were actually to his right. but.#the danton case#stanisława przybyszewska#french revolution#op#graphic design is my passion.#clearing the drafts

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excuse me.

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was reading The Danton Case and wanna play with the steel-like (razor) shape concept a bit

end product

#The Danton Case#stanisława przybyszewska#french revolution#frev#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#art#my art

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

First of all kudos for mentioning Palestine at the end of your speech! And congratulations on the excellent analysis.

Not that my opinion is super relevant there if you're getting/approaching your PhD, but for what is worth, I've also always thought that Przybyszewska must have identified with Robespierre to an extent.

The loneliness, alienation and their overall worldview definitely tracks. I've always thought that she saw him as – in a sense – a grossly misunderstood genius, and perhaps that is partly how she related to herself as well. His obsession with what they see as their lives' mission, his neglect of their basic human needs because of it, it's all there in the text and may easily be applied to Przybyszewska herself.

(And — this may sound dumb — but it also reminded me of the recent Contrapoints video, in which she talks about how women consume media. She brings up this interesting idea that when women see male characters as an object of affection they also partially identify with that character themselves, at the same time. I know Robespierre is obviously a historical figure but I'd argue that especially with historical fiction, the lines can become blurry, so what is true for a literary character may be applied to a historical figure as well in this context.

It's been a while since I've seen the video so I'm probably not explaining her point very well but it's something I thought I saw in TDC. I'd say that Przybyszewska could be, to an extent, identifying herself with both Eléonore (as Maximilien's fervent admirer) and with Robespierre, the lonely self-sacrificing genius, himself.

The following text was presented in Polish, under the title „Mortal deities of hidden thrones. Maximilien Robespierre in Thermidor as Stanisława Przybyszewska’s alter ego” during a comparative literature conference in May his year. My idea of in what part my PhD will be about her, and what I can and cannot publish before is still taking shape, but I really wanted to put this out here.

Stanisława Przybyszewska is remembered in the collective consciousness primarily as the author of „The Danton Case”, and secondly - as a lonely, unhappy person, living in isolation and enduring miserable living conditions of her own free will (in some sense even at her own behest). Thanks to this way of looking at her, it’s easy to classify her in the studies focusing on her, in various, constantly recurring orders, and everything that is less obvious than these two facts can be omitted equally easily. Since she is known mainly as the author of „The Danton Case”, naturally her second great drama, „Thermidor”, is being pushed to the side. And it is precisely here that her biography is reflected in the character of Robespierre, her idol and deity. When I talk about being reflected, I mean, of course, the construction of Robespierre as a person in a drama is done according to the same pattern that Przybyszewska's life in Gdańsk has followed.

What pattern was it? First of all, we are talking about an existence that is not only lonely, but also aggressively hermit-like. Przybyszewska is not only stubbornly stuck in Gdańsk, with which she had nothing in common with and which she didn’t even like, but she also rejected help from her family and the few friends; loneliness of this kind naturally involves a certain attitude towards the world and a certain view of the world. Here I would like to focus on the facts extracted from her biography, and only those that can be recorded in a somewhat visual way, because only this type of simple, inalienable information is the one that could have found a place in her drama.

The most important facts from Przybyszewska’s life: - Loneliness - Hatred - Hierarchical view [of the world/reality]

The first fact is loneliness, understood both in the physical and mental sense. The second was her hatred of people, which was not (most likely) a result of a flaw of character (unless we consider her severity to be a flaw), but rather of a complete misunderstanding that she met with at every step. In her opinion, this misunderstanding had a simple cause – it was her own genius, which she sensed and which she tried to develop in her creative work. The third fact is the specificity of her view of the world, based on a hierarchical view.

Facts from Robespierre’s life: [obviously I am talking only about his literary counterpart, and only in Thermidor] - Loneliness - Hatred - Being conscious of his existence within a certain hierarchy

Przybyszewska smuggles these three undeniable and simple facts into „Thermidor” as features defining one of the characters, Maximilien Robespierre. He also exists in seclusion - although he is undeniably the most important character in the play, he is not only absent throughout Act I, but he only exists when his absence is being talked about.

„And here we can refer to the geobiography, because Przybyszewska places her hero in conditions close to her own living situation: her Robespierre lives in a «Parisian cubicle resembling a kennel» and washes himself with icy water. [...] Robespierre's cold Parisian cubicle corresponds to the short description of a room in a barrack, made by Przybyszewska between 1927 and 1928 in a letter to her cousin, Adam Barliński: «a crumbling ice house, deprived even of running water»” (Marcin Czerwiński, „Uskok”) -> LONELINESS

Using historical knowledge, Przybyszewska places Robespierre's apartment in a lonely room in the house of a friendly family - but drawing from her own life, she definitely enhances the „vibe” of his place of residence in such a way that it corresponds as closely as possible to her own living conditions. This is not supported by historical evidence, because it is known that in the Duplay family, Robespierre occupied two comfortable and normally furnished rooms, the standard of which did not differ from the standards in 18th-century Paris.

„The present study, however, argues that in fact she takes a Gnostic view of history as an eternal opposition between matter and spirit, and that this dualism saturates the utopian project she undertook both in her art and in her life.” (Kazimiera Ingdahl, „A Gnostic Tragedy”) -> ASCETISIM

However, for Przybyszewska, deprived not only of the luxuries of everyday life, but also of even a semblance of normalcy, it seemed unthinkable to grant the person she depicted in her works - in „Thermidor” more than anywhere else - the very luxuries that she herself was deprived of, and which she didn't even miss that much. Przybyszewska loved Robespierre and considered him to be the highest being, which, due to her Gnostic view of the world, was combined with her love of asceticism. Asceticism, the rejection of the material world, is one of those practices that allow us to rise higher on the mental plane, so it was, according to her (and certainly: according to her Robespierre) indispensable of.

The second point of contact between the writer and the character is hatred. The topic as such appears frequently in her prose, but in her dramas it appears only in these two lesser-known ones; as if she couldn't write about hatred in a more „domesticated” way. Przybyszewska rewrote each scene in „The Danton Case” at least 4 times, usually 10 – „Thermidor”, however, is a play written first and not even completely finished, so there are a few stylistically jarring places in it. From the point of view of this essay, the most important thing at this point seems to be the description of hatred from the mouth of Robespierre himself.

„In fact: I literally had a fever while writing. Everything is boiling inside of me. I cannot give you any idea of how much I suffer terribly with this absolutely powerless rage in the face of stupidity. When I first read this article, I regularly felt physically sick: I couldn't eat for hours. Besides, the blood rushed to my head so much that I was careless by putting it under the tap. Such bodily symptoms never reach the level of rage in me because of my own affairs.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> HATRED

This corresponds with Przybyszewska’s views; she spent her adult life without finding understanding or friendship among people (or at least friendship on her, harsh and inaccessible, terms), and so she felt hatred on a similarly physical level; even if she admitted that she didn't feel that way for personal reasons.

The same can be said about Robespierre, who hates not a single man, but what a man aspires to. There are more mentions of hatred in Przybyszewska's rich epistolography, and in the creation of Robespierre as a literary character in „Thermidor”, „The Danton Case” and „The Last Nights of Ventoese”, in fact, there are more - in this essay I only want to highlight this similarity as something more than similarity, as pouring of the writer's personal experience into the „personal experience” of the character.

„When you read and interpret [Przybyszewska's] correspondence, dramas and prose, after some time you begin to notice the constant presence of evaluations - of the world, people, their behaviors and achievements - with a dominant black, negative tone. Przybyszewska must always know and say precisely whether a person and a work are great and outstanding, or small and unsuccessful; whether she is dealing with the first or fourth „level” of creators. (Ewa Graczyk, „Ćma”) -> HIERARCHICAL VIEW

The third similarity is what Ewa Graczyk has called the „hierarchical view” and there can be no doubt that Przybyszewska - by adoring Robespierre, admiring him, idealizing him in her plays - transmits this trait of hers onto him not so much consciously, but because the hierarchical nature of her gaze is an inherent part of her as a person and she is unable to create a universum which would operate according to rules other than those she herself had adhered to. And hierarchization is closely related to hatred.

„During the winter, I suffered from a fear - as incredible as it was downright unpleasant - that I had come too far for my years. While last year with every page I wrote, bad and clumsy as they were, revealed to me the beginning of some line of development, thus marking all the directions of the path destined for me, which I immediately tried to follow - now this comfortable feeling of apprenticeship, of beginning, suddenly left me. I have not abandoned my path, the only one that suits my personality and that I have recognized from my mistakes. But the anticipated goal was achieved. Already. It terrified me. I thought I had gone all the way around in one year. There was nothing left for me to do but die.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”)

Robespierre, placed in a situation undoubtedly much easier to bear than Przybyszewska was, does not share with her similar dilemmas. Why? Because Przybyszewska all her life was afraid that she was not good enough - or maybe she was not so much „afraid” as she was convinced that she had not yet reached the peak of her abilities. Robespierre, on the other hand, although from time to time he may experience dilemmas related to not knowing whether he sees and assesses the situation correctly, knows for sure that although he may not be the greatest, at the same time, there is no one greater than him. Therefore, Przybyszewska's fear and uncertainty are not foreign to him; altough the same cannot be said about her irritation and anger, and not her appraising, mathematical view of other people.

It is clear that Przybyszewska poured her life experience into Robespierre; she probably did not have many other opportunities to narrate any literary work - in all her works not only the same themes or types of people are repeated, but also the same solutions and considerations. This results from her own character, but also from one more thing, closely related to the hierarchical view: her isolation took place at the ground level. This is both in its metaphorical and literal meaning: Przybyszewska lived in her barrack, rented to her out of pity, separated from others only by too thin walls, and nothing else. What is missing in her life is the introduction of some distance that would allow her to consider her situation as something other than - depending on her mood - a deep misfortune or a forced, but at least temporary, stop on the way to somewhere greater. It is a position on the same level as everyone else, or even worse than that: it is a position among people whom she considered lower than herself, but for which she had no evidence.

„During the winter, I suffered from a fear - as incredible as it was downright unpleasant - that I had come too far for my years. While last year with every page I wrote, bad and clumsy as they were, revealed to me the beginning of some line of development, thus marking all the directions of the path destined for me, which I immediately tried to follow - now this comfortable feeling of apprenticeship, of beginning, suddenly left me. I have not abandoned my path, the only one that suits my personality and that I have recognized from my mistakes. But the anticipated goal was achieved. Already. It terrified me. I thought I had gone all the way around in one year. There was nothing left for me to do but die.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> GEOMETRY OF EXISTENCE

At this point, it is worth returning to this fragment and taking a closer look at the underlined fragments. Przybyszewska thinks about her life using vocabulary related to geometry (she briefly tried to study mathematics in her youth). However, this geometry is flat, located on one plane - a line, a circle, a designated direction. She has no space to breathe. And this is not only due to the forced pause in creative work, but also – more of an everyday problem - because of her room:

„My current apartment measures 2.25 x 4.60 metres. Measure it and you will see what it means. On top of that, there's a window – half a size of a normal one.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> GEOMETRY OF EXISTECE

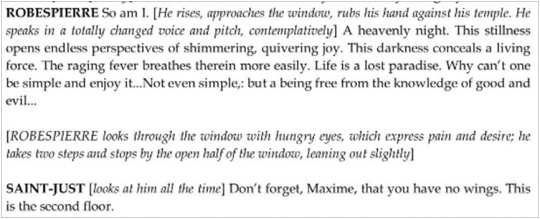

There is little space, then, in any sense of the word, and she can only spread her wings through Robespierre, whom she admires but whom she secretly would also like to be: his room, at least, is upstairs. I say this sentence a bit ironically (although it is true), just to emphasize that he actually had more space. And when he left, after he disappeared from the political scene for some time (as it is the situation at the beginning of „Thermidor”), he moved away from people in more than one dimension.

And this simultaneous elevation to heights, even if only heights of a second floor, and remoteness from people in every other possible respect, is what pushes Robespierre's opponents to understand him in terms of divinity. There is not much in it of praise, more of a statement of fact that must be accepted before it can be refuted. So what is Robespierre's divinity in Thermidor?

First of all, it is his inherent feature, the lens through which others must look at him. It's not just those who know him personally and work with him - it's about France in general. But the point is not to list all the moments in which one of the characters recognizes Robespierre as a god - let's consider it as a fact, just as they recognize it, and let's get over it to ask ourselves: what does this mean?

The main meaning is panic. Przybyszewska, through Robespierre, at least partially fulfills the dream of achieving success and the associated with it strong reactions of the world to the presence of such a successful person. Fear in this case is the highest form of flattery, except perhaps sincere (really sincere) devotion. This fear is both an expression of hateful admiration and a driving force behind the characters' actions. It results from a reluctant but unwavering faith in the divinity of their opponent and it is transformed into taking action, into an attempt (as history shows and as Przybyszewska would have shown in the play if she had completed it: a successful attempt) to overthrow the one who is a god, but not a guardian. Whoever keeps his divinity locked inside himself cannot get rid of it, but he does not make it a gift to others, but rather a curse to himself.

-> MORTALITY OF A DEITY

Because Robespierre is a mortal god. Przybyszewska created thorugh him something like a parody of Christ: a man-god in whom each nature is equally weak and each loses. Since each of them loses, then, unlike Christ, each of them dies. He actually „is burning in the blast furnance of his spirit” - because he makes decisions that bring about his own destruction. This is similar to the situation of Przybyszewska, who – so it would seem - did everything in her power to alienate the people on whose financial support she depended; who stubbornly stayed in Gdańsk instead of moving to one of the cities where she could receive more help from her family; who refused to undergo addiction treatment even under the threat of losing her government stipend. Her own non-humanity is inscribed in her through pride, to which she openly admitted and called „satanic” – she is linked with mortality in the same way.

In Robespierre, humanity and divinity combine in an unusual way: he worships himself, he’s convinced of his extraordinary power, and every matter he undertakes confirms this belief. But what is a monstrance if not a kind of visible concealment? What is the meaning of his long, six-week stay outside the French political scene at a time when he is needed there the most?

In her book „FORMS: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy and Network”, Caroline Levine proposes the introduction of the term „affordance”. An affordance is an action that is hidden in a given object or concept; an action forced, as it were, by a form that is itself a kind of oppression. In „Thermidor”, the form that has the greatest importance for the plot is an enclosed space. On the one hand, we are talking about the meeting room of the Committee of Public Safety (Przybyszewska preserved the unity of the place in the drama), and on the other - about Robespierre's apartment, which is only briefly mentioned.

-> AFFORDANCE OF HIDING

His withdrawal and his absence create anxiety among his opponents. The fear mentioned earlier is related to how the other revolutionaries feel about Robespierre as a person - but there is more to it than that. His absence, which does not prevent him from having a perfect understanding of the political situation at that time, has something uncanny about it. He himself puts it best: “There is something uncanny about this business. It is as if one discovered venomous teeth in a paper snake, or a hangman's rope in a young girl's sewing case [...]”. There is a reason why these comparisons make us feel uncomfortable: they violate the natural affordances of the cases mentioned, since paper should not be venomous and a sewing case should not contain a hangman’s rope. A room in a family home should not in any way resemble a place where a dangerous animal lurks [in the Polish version Robespierre is being likened to a spider] - and yet Robespierre evokes this type of association in others, probably without being fully aware of it himself.

„I remember that I saw her several times in the morning hours, walking from her apartment (in the barracks) through the courtyard of the Gimnazjum Polskie, sideways and stealthily, so much so that it was difficult to see her face.” (Ewa Graczyk, „Ćma”) -> COMING DOWN TO EARTH

His throne – his altar – is hidden, therefore it’s deprived of contact with the earth and its inhabitants. When, after a few weeks of absence, he decides to come down, he causes not only panic, but also simple surprise. This is not far from the personal experience of Przybyszewska, who at some point began to avoid going outside, and when circumstances forced her to do so, her appearance caused quite a surprise among onlookers - and (just like Robespierre) she was at odds with people both on „the sidewalk plane”, and on the mental plane.

-> FALLING DOWN ONTO EARTH

However, the mere physical descent to earth does not mean that Robespierre has left the spiritual and mental heights on which he dwells as a deity. Saint-Just's warning is not just mere words, but an expression of concern about the entire situation that Robespierre has just unfolded before his eyes - a situation that is almost impossible to solve and poses a real threat to the „paradise on earth” for Robespierre is the Republic. Falling from a height is also a threat to the spirit and a reference to the fall of Satan.

-> A LITERAL FALL

It is also simply a signal of the beginning of defeat. The affordance of the closed room was violated, so by getting rid of his loneliness and separation, Robespierre also deprived himself of their positive aspects. The mortal god descended to earth, thereby shedding the protective layer provided by the distance between himself and others, between his plan and the reality in which he lived - and his opponents, whether in human form or in the form of a natural course things, they immediately took advantage of the situation. And here we can find a reference to the situation of Przybyszewska, who at some point started to avoid seeing her friends from Gdańsk – a married couple Stefania and Jan Augustyńscy - because Stefania was, in Przybyszewska's opinion, too perceptive and did not fall for the artificial distance put between them through the words of „Everything is fine”. Thus, the writer trapped herself in the form and allowed it to turn into a prison. This kind of action somehow justified her and took away the responsibility for improving her life.

(Caroline Levin,e „FORMS: Whole,Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network) -> AFFORDANCE OF ISOLATION

Any form is a type of oppression. By imposing its order, it also forces the way of seeing and thinking. Robespierre's paranoia did not appear out of nowhere - it is the result of isolation (the only person who acts as a link and a buffer between the closed form of Robespierre’s private room and the closed form of the meeting room is Saint-Just - and Saint-Just has been struggling with the war on the Northern front for several weeks). It is no different with Przybyszewska herself, whose attitude towards the world was largely dependent on her financial conditions, which she did not try to improve: "Since [Staśka] is not crushed by the grey of everyday and by the struggle for a piece of bread, the general hatred towards people and constant fear of them ceased” wrote her husband in a letter to Helena Barlińska.

-> THE DUAL NATURE OF AFFORDANCE

When it comes to affordance, there is one more detail we need to pay attention to. The physical form - in this case, a room - influences the spiritual form, but it also works the other way around. Robespierre's paranoia is therefore a factor whose affordances (e.g. haste, keeping a secret, high treason) have a real, negative impact on the Republic in general and his life in particular. Acting under the influence of the conditions he himself has created, he finds himself on the road to making more and more mistakes, making the situation worse, and driving himself into a dead end. The fact that he does not seem to take this possibility into account points once again to his divinity and the pride that comes with it.

-> THE AFFORDANCE OF ROBESPIERRE

From the depths - and heights - of his tabernacle, Robespierre commands the situation. He exerts an absolute influence, which at the same time is based on nothing more than his person. Therefore, it is his personal affordance, the effect not of a specific action, but rather the result of his presence in the world, the resultant of all his features. This is where he differs from Przybyszewska, who dreamed of having such an influence on the masses, or at least on a group of people. Thus, this confirms the thesis about constructing Robespierre in „Thermidor” as her alter ego - similar enough to be confused with her, but better and more powerful.

I would like to end here and take advantage of the opportunity to mention that after 216 days of genocide in Gaza, as of the day I have delivered this essay, there is no university left there. We have the right and opportunity to promote science, and therefore we also have an ethical obligation to stand on the side of the victims of genocide, who were deprived of this right and opportunity. I hope that in our lifetime we will see a free, independent Palestine.

#great analysis#stanisława przybyszewska#Przybyszewska#the danton case#thermidor#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#frev#french revolution#literature#analysis#frev resources#good luck with your PhD!#frevblr#history#eleonore duplay

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making Przybyszewska's plays look like illustrated kid novels

70 notes

·

View notes