#stanislawa przybyszewska

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The following text was presented in Polish, under the title „Mortal deities of hidden thrones. Maximilien Robespierre in Thermidor as Stanisława Przybyszewska’s alter ego” during a comparative literature conference in May his year. My idea of in what part my PhD will be about her, and what I can and cannot publish before is still taking shape, but I really wanted to put this out here.

Stanisława Przybyszewska is remembered in the collective consciousness primarily as the author of „The Danton Case”, and secondly - as a lonely, unhappy person, living in isolation and enduring miserable living conditions of her own free will (in some sense even at her own behest). Thanks to this way of looking at her, it’s easy to classify her in the studies focusing on her, in various, constantly recurring orders, and everything that is less obvious than these two facts can be omitted equally easily. Since she is known mainly as the author of „The Danton Case”, naturally her second great drama, „Thermidor”, is being pushed to the side. And it is precisely here that her biography is reflected in the character of Robespierre, her idol and deity. When I talk about being reflected, I mean, of course, the construction of Robespierre as a person in a drama is done according to the same pattern that Przybyszewska's life in Gdańsk has followed.

What pattern was it? First of all, we are talking about an existence that is not only lonely, but also aggressively hermit-like. Przybyszewska is not only stubbornly stuck in Gdańsk, with which she had nothing in common with and which she didn’t even like, but she also rejected help from her family and the few friends; loneliness of this kind naturally involves a certain attitude towards the world and a certain view of the world. Here I would like to focus on the facts extracted from her biography, and only those that can be recorded in a somewhat visual way, because only this type of simple, inalienable information is the one that could have found a place in her drama.

The most important facts from Przybyszewska’s life: - Loneliness - Hatred - Hierarchical view [of the world/reality]

The first fact is loneliness, understood both in the physical and mental sense. The second was her hatred of people, which was not (most likely) a result of a flaw of character (unless we consider her severity to be a flaw), but rather of a complete misunderstanding that she met with at every step. In her opinion, this misunderstanding had a simple cause – it was her own genius, which she sensed and which she tried to develop in her creative work. The third fact is the specificity of her view of the world, based on a hierarchical view.

Facts from Robespierre’s life: [obviously I am talking only about his literary counterpart, and only in Thermidor] - Loneliness - Hatred - Being conscious of his existence within a certain hierarchy

Przybyszewska smuggles these three undeniable and simple facts into „Thermidor” as features defining one of the characters, Maximilien Robespierre. He also exists in seclusion - although he is undeniably the most important character in the play, he is not only absent throughout Act I, but he only exists when his absence is being talked about.

„And here we can refer to the geobiography, because Przybyszewska places her hero in conditions close to her own living situation: her Robespierre lives in a «Parisian cubicle resembling a kennel» and washes himself with icy water. [...] Robespierre's cold Parisian cubicle corresponds to the short description of a room in a barrack, made by Przybyszewska between 1927 and 1928 in a letter to her cousin, Adam Barliński: «a crumbling ice house, deprived even of running water»” (Marcin Czerwiński, „Uskok”) -> LONELINESS

Using historical knowledge, Przybyszewska places Robespierre's apartment in a lonely room in the house of a friendly family - but drawing from her own life, she definitely enhances the „vibe” of his place of residence in such a way that it corresponds as closely as possible to her own living conditions. This is not supported by historical evidence, because it is known that in the Duplay family, Robespierre occupied two comfortable and normally furnished rooms, the standard of which did not differ from the standards in 18th-century Paris.

„The present study, however, argues that in fact she takes a Gnostic view of history as an eternal opposition between matter and spirit, and that this dualism saturates the utopian project she undertook both in her art and in her life.” (Kazimiera Ingdahl, „A Gnostic Tragedy”) -> ASCETISIM

However, for Przybyszewska, deprived not only of the luxuries of everyday life, but also of even a semblance of normalcy, it seemed unthinkable to grant the person she depicted in her works - in „Thermidor” more than anywhere else - the very luxuries that she herself was deprived of, and which she didn't even miss that much. Przybyszewska loved Robespierre and considered him to be the highest being, which, due to her Gnostic view of the world, was combined with her love of asceticism. Asceticism, the rejection of the material world, is one of those practices that allow us to rise higher on the mental plane, so it was, according to her (and certainly: according to her Robespierre) indispensable of.

The second point of contact between the writer and the character is hatred. The topic as such appears frequently in her prose, but in her dramas it appears only in these two lesser-known ones; as if she couldn't write about hatred in a more „domesticated” way. Przybyszewska rewrote each scene in „The Danton Case” at least 4 times, usually 10 – „Thermidor”, however, is a play written first and not even completely finished, so there are a few stylistically jarring places in it. From the point of view of this essay, the most important thing at this point seems to be the description of hatred from the mouth of Robespierre himself.

„In fact: I literally had a fever while writing. Everything is boiling inside of me. I cannot give you any idea of how much I suffer terribly with this absolutely powerless rage in the face of stupidity. When I first read this article, I regularly felt physically sick: I couldn't eat for hours. Besides, the blood rushed to my head so much that I was careless by putting it under the tap. Such bodily symptoms never reach the level of rage in me because of my own affairs.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> HATRED

This corresponds with Przybyszewska’s views; she spent her adult life without finding understanding or friendship among people (or at least friendship on her, harsh and inaccessible, terms), and so she felt hatred on a similarly physical level; even if she admitted that she didn't feel that way for personal reasons.

The same can be said about Robespierre, who hates not a single man, but what a man aspires to. There are more mentions of hatred in Przybyszewska's rich epistolography, and in the creation of Robespierre as a literary character in „Thermidor”, „The Danton Case” and „The Last Nights of Ventoese”, in fact, there are more - in this essay I only want to highlight this similarity as something more than similarity, as pouring of the writer's personal experience into the „personal experience” of the character.

„When you read and interpret [Przybyszewska's] correspondence, dramas and prose, after some time you begin to notice the constant presence of evaluations - of the world, people, their behaviors and achievements - with a dominant black, negative tone. Przybyszewska must always know and say precisely whether a person and a work are great and outstanding, or small and unsuccessful; whether she is dealing with the first or fourth „level” of creators. (Ewa Graczyk, „Ćma”) -> HIERARCHICAL VIEW

The third similarity is what Ewa Graczyk has called the „hierarchical view” and there can be no doubt that Przybyszewska - by adoring Robespierre, admiring him, idealizing him in her plays - transmits this trait of hers onto him not so much consciously, but because the hierarchical nature of her gaze is an inherent part of her as a person and she is unable to create a universum which would operate according to rules other than those she herself had adhered to. And hierarchization is closely related to hatred.

„During the winter, I suffered from a fear - as incredible as it was downright unpleasant - that I had come too far for my years. While last year with every page I wrote, bad and clumsy as they were, revealed to me the beginning of some line of development, thus marking all the directions of the path destined for me, which I immediately tried to follow - now this comfortable feeling of apprenticeship, of beginning, suddenly left me. I have not abandoned my path, the only one that suits my personality and that I have recognized from my mistakes. But the anticipated goal was achieved. Already. It terrified me. I thought I had gone all the way around in one year. There was nothing left for me to do but die.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”)

Robespierre, placed in a situation undoubtedly much easier to bear than Przybyszewska was, does not share with her similar dilemmas. Why? Because Przybyszewska all her life was afraid that she was not good enough - or maybe she was not so much „afraid” as she was convinced that she had not yet reached the peak of her abilities. Robespierre, on the other hand, although from time to time he may experience dilemmas related to not knowing whether he sees and assesses the situation correctly, knows for sure that although he may not be the greatest, at the same time, there is no one greater than him. Therefore, Przybyszewska's fear and uncertainty are not foreign to him; altough the same cannot be said about her irritation and anger, and not her appraising, mathematical view of other people.

It is clear that Przybyszewska poured her life experience into Robespierre; she probably did not have many other opportunities to narrate any literary work - in all her works not only the same themes or types of people are repeated, but also the same solutions and considerations. This results from her own character, but also from one more thing, closely related to the hierarchical view: her isolation took place at the ground level. This is both in its metaphorical and literal meaning: Przybyszewska lived in her barrack, rented to her out of pity, separated from others only by too thin walls, and nothing else. What is missing in her life is the introduction of some distance that would allow her to consider her situation as something other than - depending on her mood - a deep misfortune or a forced, but at least temporary, stop on the way to somewhere greater. It is a position on the same level as everyone else, or even worse than that: it is a position among people whom she considered lower than herself, but for which she had no evidence.

„During the winter, I suffered from a fear - as incredible as it was downright unpleasant - that I had come too far for my years. While last year with every page I wrote, bad and clumsy as they were, revealed to me the beginning of some line of development, thus marking all the directions of the path destined for me, which I immediately tried to follow - now this comfortable feeling of apprenticeship, of beginning, suddenly left me. I have not abandoned my path, the only one that suits my personality and that I have recognized from my mistakes. But the anticipated goal was achieved. Already. It terrified me. I thought I had gone all the way around in one year. There was nothing left for me to do but die.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> GEOMETRY OF EXISTENCE

At this point, it is worth returning to this fragment and taking a closer look at the underlined fragments. Przybyszewska thinks about her life using vocabulary related to geometry (she briefly tried to study mathematics in her youth). However, this geometry is flat, located on one plane - a line, a circle, a designated direction. She has no space to breathe. And this is not only due to the forced pause in creative work, but also – more of an everyday problem - because of her room:

„My current apartment measures 2.25 x 4.60 metres. Measure it and you will see what it means. On top of that, there's a window – half a size of a normal one.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> GEOMETRY OF EXISTECE

There is little space, then, in any sense of the word, and she can only spread her wings through Robespierre, whom she admires but whom she secretly would also like to be: his room, at least, is upstairs. I say this sentence a bit ironically (although it is true), just to emphasize that he actually had more space. And when he left, after he disappeared from the political scene for some time (as it is the situation at the beginning of „Thermidor”), he moved away from people in more than one dimension.

And this simultaneous elevation to heights, even if only heights of a second floor, and remoteness from people in every other possible respect, is what pushes Robespierre's opponents to understand him in terms of divinity. There is not much in it of praise, more of a statement of fact that must be accepted before it can be refuted. So what is Robespierre's divinity in Thermidor?

First of all, it is his inherent feature, the lens through which others must look at him. It's not just those who know him personally and work with him - it's about France in general. But the point is not to list all the moments in which one of the characters recognizes Robespierre as a god - let's consider it as a fact, just as they recognize it, and let's get over it to ask ourselves: what does this mean?

The main meaning is panic. Przybyszewska, through Robespierre, at least partially fulfills the dream of achieving success and the associated with it strong reactions of the world to the presence of such a successful person. Fear in this case is the highest form of flattery, except perhaps sincere (really sincere) devotion. This fear is both an expression of hateful admiration and a driving force behind the characters' actions. It results from a reluctant but unwavering faith in the divinity of their opponent and it is transformed into taking action, into an attempt (as history shows and as Przybyszewska would have shown in the play if she had completed it: a successful attempt) to overthrow the one who is a god, but not a guardian. Whoever keeps his divinity locked inside himself cannot get rid of it, but he does not make it a gift to others, but rather a curse to himself.

-> MORTALITY OF A DEITY

Because Robespierre is a mortal god. Przybyszewska created thorugh him something like a parody of Christ: a man-god in whom each nature is equally weak and each loses. Since each of them loses, then, unlike Christ, each of them dies. He actually „is burning in the blast furnance of his spirit” - because he makes decisions that bring about his own destruction. This is similar to the situation of Przybyszewska, who – so it would seem - did everything in her power to alienate the people on whose financial support she depended; who stubbornly stayed in Gdańsk instead of moving to one of the cities where she could receive more help from her family; who refused to undergo addiction treatment even under the threat of losing her government stipend. Her own non-humanity is inscribed in her through pride, to which she openly admitted and called „satanic” – she is linked with mortality in the same way.

In Robespierre, humanity and divinity combine in an unusual way: he worships himself, he’s convinced of his extraordinary power, and every matter he undertakes confirms this belief. But what is a monstrance if not a kind of visible concealment? What is the meaning of his long, six-week stay outside the French political scene at a time when he is needed there the most?

In her book „FORMS: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy and Network”, Caroline Levine proposes the introduction of the term „affordance”. An affordance is an action that is hidden in a given object or concept; an action forced, as it were, by a form that is itself a kind of oppression. In „Thermidor”, the form that has the greatest importance for the plot is an enclosed space. On the one hand, we are talking about the meeting room of the Committee of Public Safety (Przybyszewska preserved the unity of the place in the drama), and on the other - about Robespierre's apartment, which is only briefly mentioned.

-> AFFORDANCE OF HIDING

His withdrawal and his absence create anxiety among his opponents. The fear mentioned earlier is related to how the other revolutionaries feel about Robespierre as a person - but there is more to it than that. His absence, which does not prevent him from having a perfect understanding of the political situation at that time, has something uncanny about it. He himself puts it best: “There is something uncanny about this business. It is as if one discovered venomous teeth in a paper snake, or a hangman's rope in a young girl's sewing case [...]”. There is a reason why these comparisons make us feel uncomfortable: they violate the natural affordances of the cases mentioned, since paper should not be venomous and a sewing case should not contain a hangman’s rope. A room in a family home should not in any way resemble a place where a dangerous animal lurks [in the Polish version Robespierre is being likened to a spider] - and yet Robespierre evokes this type of association in others, probably without being fully aware of it himself.

„I remember that I saw her several times in the morning hours, walking from her apartment (in the barracks) through the courtyard of the Gimnazjum Polskie, sideways and stealthily, so much so that it was difficult to see her face.” (Ewa Graczyk, „Ćma”) -> COMING DOWN TO EARTH

His throne – his altar – is hidden, therefore it’s deprived of contact with the earth and its inhabitants. When, after a few weeks of absence, he decides to come down, he causes not only panic, but also simple surprise. This is not far from the personal experience of Przybyszewska, who at some point began to avoid going outside, and when circumstances forced her to do so, her appearance caused quite a surprise among onlookers - and (just like Robespierre) she was at odds with people both on „the sidewalk plane”, and on the mental plane.

-> FALLING DOWN ONTO EARTH

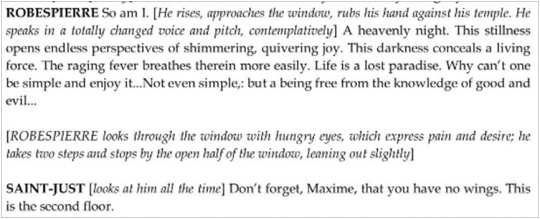

However, the mere physical descent to earth does not mean that Robespierre has left the spiritual and mental heights on which he dwells as a deity. Saint-Just's warning is not just mere words, but an expression of concern about the entire situation that Robespierre has just unfolded before his eyes - a situation that is almost impossible to solve and poses a real threat to the „paradise on earth” for Robespierre is the Republic. Falling from a height is also a threat to the spirit and a reference to the fall of Satan.

-> A LITERAL FALL

It is also simply a signal of the beginning of defeat. The affordance of the closed room was violated, so by getting rid of his loneliness and separation, Robespierre also deprived himself of their positive aspects. The mortal god descended to earth, thereby shedding the protective layer provided by the distance between himself and others, between his plan and the reality in which he lived - and his opponents, whether in human form or in the form of a natural course things, they immediately took advantage of the situation. And here we can find a reference to the situation of Przybyszewska, who at some point started to avoid seeing her friends from Gdańsk – a married couple Stefania and Jan Augustyńscy - because Stefania was, in Przybyszewska's opinion, too perceptive and did not fall for the artificial distance put between them through the words of „Everything is fine”. Thus, the writer trapped herself in the form and allowed it to turn into a prison. This kind of action somehow justified her and took away the responsibility for improving her life.

(Caroline Levin,e „FORMS: Whole,Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network) -> AFFORDANCE OF ISOLATION

Any form is a type of oppression. By imposing its order, it also forces the way of seeing and thinking. Robespierre's paranoia did not appear out of nowhere - it is the result of isolation (the only person who acts as a link and a buffer between the closed form of Robespierre’s private room and the closed form of the meeting room is Saint-Just - and Saint-Just has been struggling with the war on the Northern front for several weeks). It is no different with Przybyszewska herself, whose attitude towards the world was largely dependent on her financial conditions, which she did not try to improve: "Since [Staśka] is not crushed by the grey of everyday and by the struggle for a piece of bread, the general hatred towards people and constant fear of them ceased” wrote her husband in a letter to Helena Barlińska.

-> THE DUAL NATURE OF AFFORDANCE

When it comes to affordance, there is one more detail we need to pay attention to. The physical form - in this case, a room - influences the spiritual form, but it also works the other way around. Robespierre's paranoia is therefore a factor whose affordances (e.g. haste, keeping a secret, high treason) have a real, negative impact on the Republic in general and his life in particular. Acting under the influence of the conditions he himself has created, he finds himself on the road to making more and more mistakes, making the situation worse, and driving himself into a dead end. The fact that he does not seem to take this possibility into account points once again to his divinity and the pride that comes with it.

-> THE AFFORDANCE OF ROBESPIERRE

From the depths - and heights - of his tabernacle, Robespierre commands the situation. He exerts an absolute influence, which at the same time is based on nothing more than his person. Therefore, it is his personal affordance, the effect not of a specific action, but rather the result of his presence in the world, the resultant of all his features. This is where he differs from Przybyszewska, who dreamed of having such an influence on the masses, or at least on a group of people. Thus, this confirms the thesis about constructing Robespierre in „Thermidor” as her alter ego - similar enough to be confused with her, but better and more powerful.

I would like to end here and take advantage of the opportunity to mention that after 216 days of genocide in Gaza, as of the day I have delivered this essay, there is no university left there. We have the right and opportunity to promote science, and therefore we also have an ethical obligation to stand on the side of the victims of genocide, who were deprived of this right and opportunity. I hope that in our lifetime we will see a free, independent Palestine.

#I WHOLEHEARTEDLY ENCOURAGE YOU ALL TO ALWAYS MENTION PALESTINE WHEN YOU'RE GIVING A SPEECH#IT IS WORTH IT AND WE ARE MORALLY OBLIGATED TO DO IT#stanisława przbyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#thermidor#maximilien robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#robespierre#affordance#ewa graczyk#marcin czerwiński#caroline levine#kazimiera ingdahl#literary analysis#comparative literature

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guess who's just acquired the recording of a stageplay of Przybyszewska's "Thermidor" from 2015 👁👄👁

#I can only access it for a month but I'm already thinking how to download it#I had to lie a bit to get it buuuut#a friend of mine who specialises in theatre studies advised me to do so#so i guess it's pretty common to do it#i probably won't send it to anyone as long as I can't download it for good#then we'll see#frev#thermidor#stanislawa przybyszewska

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I thought Hilary mantel was crazy for the psychosexual depravities she conjured in her French Revolution rpf but stanislawa przybyszewska was out here in 1929 just writing yaoi

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

love huet in this

Adapted from a play by Stanislawa Przybyszewska, The Danton Case, the film capitalizes on the familiar and contrasting figures of Danton and Robespierre. In contrast to Danton's exuberant, larger-than-life physique (Danton is played by a robust Depardieu), Robespierre (brilliantly played by Wojciech Pszoniak) is true to his legend...

......yeah, depardieu.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does anyone know where can I find Stanislawa przybyszewska letters in Pdf or ePub? I Just foud all her plays in polish on sale in ePub in a polish webpage.

I need them 😭😭

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wow, it's in the English translation too? I just thought it's in the Czech one because it was translated before the Velvet revolution. Now I'm starting to think it had to have been used in the Polish original as well.

The Czech translation has both "soudruzi" (comrades) in some places as well as "občane*občanko" (citizen, m/f) in others

Dramatic stage direction/scene descriptions, and, read out of context, Danton and Saint-Just acting like petty children with a crush on the same boy.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

…at least I was quite aware that my soul had strayed into dirty back alleys, but that was precisely the whole priceless, demonic charm of it. That’s what it meant to be a twentieth century adolescent.

-- Stanislawa Przybyszewska

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stasia was truly a genius. Not only are her Robespierre and Saint-Just adorable, but she includes a long rant about the evils of capitalism!

#i wish she finished her thermidor play :(((#i wonder if working on it made her sad?#robespierre#saint-just#stanislawa przybyszewska

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, so I've found yet another version of the "Danton's Case" play

Because I have a habit of searching random Przybyszewska related stuff on the Internet in the middle of a night. And oh boi.

Look, here's for example Danton fucking lifting a tiny Robespierre into the air + other moments of their confrontation

Dantom and Camille being super dramatic + Danton getting protective of him

A passed out Philipeaux

Louise and Lucile just being amazing and beautiful

+BONUS

Camille had to be literally carried out during the trial

#ok LISTEN THIS WAS SUCH A WILDE RIDE#even wilder aomethimes than the box version I must admit#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#camille desmoulis#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton's case#sprawa dantona#frev#french revolution

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

reblogging this post as well because it includes a great analysis of Louise Danton.

Sure, Louise as a literary character in Przybyszewska's play that is just based on the real woman, but I'd say it is still important, especially if so little is known about her as a historical figure.

And the character breakdown of Lucile and Éleonore is obviously worth reading as well.

It is absolutely doubtless to me that Przybyszewska had a problem or two when creating and describing/explaining her heroines, problems, which do not seem to occur when men are concerned. I do think, however, that in The Danton Case (not to mention her prose) she managed to build female characters with distinct personalities, which is more than can be said of some other classics.

Going back to the way sexuality is being portrayed in The Danton Case, I honestly think that in order to be able to discuss it with good sense one needs to understand and respect asexuality. I am being somewhat in opposition to what Monika Świerkosz proposes in her article on the subject, I do not think that Przybyszewska's women "deny themselves any pleasure" when they choose ascetisim or politics, because one cannot deny themselves anything if one doesn't believe in the existence of such "pleasures". I feel that in this very personal aspect of a human life, Przybyszewska was drawing from her own experience more than on any other occasion: the pleasures of life was, to her understanding, ascetisim/celibacy and politics, and choosing them in no way indicates negating oneself. "It would appear then Przybyszewska realises that "a full lack of the element of desire" in regards to the world is a more radical violation of the norm than homosexuality or perverse sex; it is something for which there are no words". With this though, I agree in fullness. And so, all of Przybyszewska's heroines seem to share one quality, that is – they resemble ancient virginal goddesses of some sort, not exactly because there is an aura of divinity about them, but because they do not seem to be fully, wholly human. This "virginal" quality has little to do with their sex lives, and more with the desire for autonomy on all levels of being (physical and spiritual, not to mention – mental). I reserve for myself the singular right to my life was Przybyszewska's credo and arguably the strongest, firmest phrase she has ever coined. And this is the energy she breathed into all three women in The Danton Case (excluding, I must add, the few appearing in the very first scene; but most of the time no one reads it anyway); the level of intensity and the direction of this desire varies, but it is always present. I would like to present this in three parts, each relevant to one of the characters of the play.

Eleonore is evidently Przybyszewska's favourite, if only because she's devouted to Robespierre – but I think she is also modeled a lot after Przybyszewska herself, not just in terms of this undying devotion, but hers is the type that is later reproduced in many short stories (which, unlike the plays, are filled with women of different kinds to the brim), which makes it obvious she was armed with qualities the author found appealing. That's why it's so strange that Przybyszewska has essentially created two very different Eleonores: one in the play, and one in The Last Nights of Ventose. The first one is definitely meant to be depictured as elder, she has an ironic sense of humour and is very decisive and firm, despite making allowances for Maxime and his rigid rules. The second one is definitely younger, has a hard time grasping at irony, is timid at times and yields to Maxime rather than moves not to be crushed by his wishes. For a reader – probably any reader – the first one is definitely more appealing, more fun to read – more complex even, and given a will of her own, which makes her stand out among the majority of the play's characters (for example: the other members of Comsal have less distinctive personalities than her).

There is a weakness in her, though, or at least the way I see it: she does not feel natural. I'd give anything to have a strong, believable female character in that play, but Eleonore is... not it. Her sense of humor, her quips, her behaviour when she's constantly being met with disappointement don't read real in my eyes, it reads as something "too cool to be true" – therefore, it probably isn't. She has some occasional moments ("You viper!" comes to mind) when naturality shines through her words, but it isn't 100% of the time.

How does Eleonore express her femininity, does she do it at all? Well, yes and no. She seemingly willingly puts herself in a position, which is stereotypically feminine, that is to say: but an accomplice to the man of her life, putting herself second and him first, occupying herself with stereotypically feminine tasks of housekeeping and taking care of others (it is worth noting that these are all traits that have potentially negative quality about them, they can easily be distorted into degradation). In the same time, she assumes the air of equality when talking with Robespierre, is deeply interested in politics and holds her own when Maxime tries to dismantle her attempts at reaching out to him. She is also decidedly "virginal", if we are to reach out to the terminology from before, taking a firm stand against motherhood, even expressing a certain amount of contempt for the idea; this is, however, where the virginity of hers ends, because she is otherwise a very sexual person. To be honest, the way in which she is being presented to the audience – literally sliding down Robespierre's torso and kneeling to him, gripping tightly at his knees and very visibly trying to give him a blowjob first thing she sees him well after weeks of illness – is rather disgusting, not necessarily because sex is (a disclaimer, which could probably be put at the beggining of this post, since it's a bit relevant: OP is asexual and has nothing positive to say about sex), but because this is how she imprints in the audience's minds. No feigned irony of hers, no clever remark will be taken as just that, all will be tainted with the image of this otherwise sensible woman degrading herself for a scrap of attention from someone who says bluntly that she is indifferent to him (and as I always underline, in the universum of this play, Robespierre only ever speaks the truth, at least in the spiritual/mental matters, so we know he means it).

For the reasons listed above, I see her as both womanly and manly, if we could call it that. Monika Świerkosz, a Przybyszewska scholar, said that "[...] in Przbyszewska's prose works womanhood and manhood stand in a binary oppsosition to one another, and neither is an enclave of happiness of identity." – I don't think it's strictly accurate. To my understanding, the phenomenon relies on Przybyszewska not relying on any kind of deeply rooted gender stereotypes in creating her characters. It's not like she's taking a steretypically understood masculinity and simply sprinkles it over her heroines! She is operating in the fields of transsexuality, demisexuality and nonbinarity (not exactly in the convential meanings of these words, but there is something to it). I find it hard to put in words, perhaps the thing I want to say is mostly that her characters as a whole don't fit a clearly defined niche and live their own lives at the outskirts of customarily understood gender instead of being solely mouthpieces for the author.

Going back to the concept of virginity, which is especially relevant in Eleonore's case (and especially the one from TLNoV), when it comes to the woman who is always in Robespierre's orbit, it is being contrasted with his own attitude and thoughts on the topic. She's the one begging him to reconsider his stance on the subject, she's the one trying to sneak up on him and shutter his defenses (which is, again, explored and explained in a more detailed way in the novel). It is worth mentioning, though, that while she is constructed as a somewhat sensual person, she is still babyfied about it, there are narrator's remarks about her naivete and innocence in this regard, despite some – very limited – sexual experience. For this reason I'm on the fence in deciding how exactly is this trait used in Eleonore's case. Is she meant to be seen as more mature because she's had experience, knows what she wants, and she's willing to do a lot to obtain it? Or is she meant to be seen as more silly and childlike, not understanding her own desires to the fullest? Are we to admire her or pity her?

Willingly or not, Eleonore becomes an embodiment of a very important characteristic which Przybyszewska uses extensively in her short prose works. If she, for whatever reason, cannot achieve the fullfilment of what she's striving towards, she then personifies ascetisim. And ascetisim is the clou of all of Przybyszewska's life. At the heart of matters, she doesn't care for either virginity or motherhood (in this making equal two things treated usually as polar opposites) as long as ascetisim remains in the world. It is for Przybyszewska a synonym of both "autonomy" and "agency", two ideals powering her life (though, might I add, there is a bit of falsity in this, for her own autonomy relied on being dependent on the financial help received from others and she gave up an almost full autonomy – which could be found in providing for herself – in exchange for the absolutely full autonomy in just one aspect of her life: writing).

I have mentioned before that Eleonore doesn't seem to be entirely natural in her behaviour. Przybyszewska was to a very large extent fascinated by futurism (for her the Revolution, as well as any potential revolution, was worth taking notice of because it brough in the new), and a big part of european futurism was its own fascination by machines. While I, personally, disagree with the notion that machines and robots become a synecdoche of a man, perhaps it really were so for the futurists. A machine ceased to be something completely external and foreign to the humans, it begun to be more of an external part of a perosn's body, a complement of sorts. I think this is why "female" robots, or in general any mesh-up of robots and women may seem more natural to us: they usually already have this one additional organ, and through it, they can produce more humans. And this is what ties back to the idea of Przybyszewska's female characters being sort of divinities, but in a cold, rigid (ascetic!) sense of the world.

For none of them is exactly warm. Moving from Eleonore onto Louise,we can see she's even colder, and not without a reason, there is a cause for why she is the way she is – standing as a contrast to the fleshy, "humane" Danton she couldn't be anything else. What I like particularly well about this portrayal is that it's never shown in a negative way (and not even because Danton is... I think Przybyszewska's own sad experience with sexual abuse played a part in that). For the reasons of the sexual abuse she underwent, Louise is also portrayed in a decidedly virignal light: the things that have happened to her do not define her. She is so in a very different way than Eleonore, she weaponizes this part of her life which is seen as stereotypically connected to womanhood, while being detached from sensuality: motherhood. Her pregnancy is the first respite from Danton she has and she clings onto it, not even in a desperate way, it's cold, calm and calculated. Her young age also serves the same purpose, it detaches her from the customarily understood femininity, it makes her less "womanly" and more "girlish". I don' think I speak only for myself when I say the audience would have a hard time imagining Louise actually becoming a mother; for her this is only a weapon, a means to an end and that is because she is not yet fully formed woman, in a sense.

There is a thing about her and her appearance in the novel and how it presents to us that begs a moment of distraction. In his movie, Wajda took care of presenting both Eleonore and Lucille in a visually masculine way, but he did nothing of the sort with Louise (he barely included her at all, but even so, she was over the top feminine in visual aspects). I don't think this was a good move on his part, in all honesty, it creates a division between her and the other two heroines, while there should be no such thing. I think all three serve a much more unanimous role than what he'd have us believe and this text is partially meant as an explanation why.

So Louise, for obvious reasons, is rather disgusted by all matters pertaining to sex (and that is seen not only in her interactions with Danton, but also with Legendre, that's why we can safely assume so at large). She is shown as strong, strong-willed and intelligent, which is another thing pointing us in the direction of her mentality of an "ancient virign" (I use some terms liberally, but I hope I convey the meaning behind them well enough). She was stripped of all of this in the movie, and this time it was sadly yet another rung on the ladder meant to elevate Danton. In order to powder his face to make him presentable, Wajda had to exclude Louise from the movie and make her a prop rather than a person. I dare say he, as a man, saw Louise as a "anti-woman" because of her attitude and his artistic choice was the nearest antidote; but he was wrong. Przybyszewska's heroines aren't fully human, yes, and aren't fully womanly – but they aren't "antiwomen", they are "superwomen" (in the same sense of the word as "superlunary", for example). They are beyond femininity in many aspects and the only reason why we are even discussin them in any terms pertaining to gender and womanhood is becuase a. I have no other language to do it and b. these things exist in the same reality, I need to underline the fact these heroines are "superwomen" only because they, too, have an idea of what "a woman" should be and exist as a some kind of response to it. Louise, for example, has no need for it, because the root of her problems lies in the lense of femininity through which Danton sees her and if it weren't for his demise, he would continue to threaten her in a sexually abusive way, tied closely to her "role as a woman" (one of the last things he says to her is an accusation of sexual nature regarding her).

Lucille's response seems to be a lot less firm (if not: less aggressive) because her environement didn't condition her to be so fully womanly in the first place. A sfar as husbands go, Camille was a much better one than Danton: just as childish, but treating Lucille not only as a beloved, but also as an equal. This allows her for space to grow as her own peson, and if this person includes affirming her femininity (for example through being a partner to her husband, in being a tender mother, in caring for Camille when he needed her most, in loving him to the point of madness) we can rest assured it is her own choice and part of her agenda. She is not weaker than Eleonore nor Louise, she just has more space to breathe. And like Eleonore, she is deeply interested in politics, and not only that, but has a better graps of it than Camille does, connecting the dots quicker than he would. I can't say if this is a part of characterisation of the women in the play, to show them as autonomous beings capable of political thought, or if it was simply a way of gentle reminder every now and then to the audience that politics permeated the universum of the play so thoroughly everybody in it knows their way about it (it is worth noting that Louise also understands the then political troubles, but unlike the other two, she consciously cuts ties with it, for this is yet another thing which belogns to the realm of Danton, and she doesn't want to be further tainted by him).

I like the fact that Przybyszewska included a scene between Lucille and Louise, especially because it was not strictly necessary for her to do so. It is another facet of her craftiness and intention regarding the way women are being portrayed in the play, because while it exists on the structre lied down by the political plot, the most important things that an audience can draw from the scene are: while Lucille loves Camille greatly and will do anything to save him, it is not necessary for the plots/the overall theme of the play for her to act so (as proven by the indifferent Louise, who is in no way villified in her choice) and Louise is not evil as a character, because she doesn't shrink her responsibilities as a decent human being: she doesn't want to help Danton, specifically, but she provides Lucille wih a logical and pretty good way to attempt what she wants to do. Perhaps this is too little to call it a sisterhood between them, but I find this portrayal contrasting attitudes reassuring.

#stanislawa przybyszewska#stanisława przybyszewska#eleonore duplay#lucille desmoullins#louise danton#the danton case#sprawa dantona#literary analysis#frev#french revolution#women's history#1700s#frev community#frevblr#literature#przybyszewska

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The way stanislawa przybyszewska ukefied camille…….. ahead of her time

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My copy of the English translations of Przybyszewska's plays finally came in and the intro alone is a rollercoaster

Transsexual???

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transnationalism

One thing which I haven't seen being brought up before, is the issue of transnationalism in Przybyszewska's work. At first - while I usually try to have a less biography-oriented approach - I have to say this cannpot be discussed without knowing Przybyszewska's very peculiar personal standing in regards to belonging to a nation and a state (but I will try to keep it to a minimum).

She was born as an out-of-wedlock child in times when it was not regarded lightly. Though both her parents were artists, and her father extremely extravagant and with a reputation of a Don Juan (bad reputation, and entirely deserved) at that, it didn’t change much. Her mother, no matter how artsy and talented she was, was herself a protegee of an influential family, not to mention - a youg woman. Which means her pregnancy was not taken lightly, her protectors were disappointed in her, she had to move to Paris not only because it was one of very few places were women could potentially make it big as professional painters, but because she would not be received in her usual society at home. All of this jumpstarts Przybyszewska's life as a person uprooted and banished from her home - but it's not all, nor is the fact that despite knowing who her father was, she was not officially recognized as his daughter until her teen years.

When she was born, Poland was still partitioned, which made Przybyszewska a stateless person, a subject to Austria, but of course not regarded as a fully fledged citizen (and that's without even taking into account the first 12 years of her life, when she lived as an expat, mostly in France, with her mother). In fact, she lived in these conditions for the first 17 years of her life, which makes it exactly a half of it (she died at 34). And if this was not enough, when she lived in Poland, she spent the majority of her time in Gdańsk, which was a Free City, with two nationalities - Polish and German - flowing more or less freely (Polish on evidently becoming subdued as the war approached). Seeing as Przybyszewska wrote a good prtion of her works in German, and thought of it as a language far superior to Polish, and knowing her personal opinions on the state of Polish cultural life versus the cultural life in Europe, I'd wager to say she was never, ever someone who felt somewhere "at home".

Nationalities aside, she was also decidedly a gender non conforming person, which is its own issue (I attach a photo of her, and it should speak for itself). I'm not making any claim about her, it's just that everything in her life points to a. uprootedness, and thus b. being a foreigner in her own country/language/life/skin. (I think a bit more could also be said about Robespierre’s sexual orientation in the plays, and how it’s adding another layer of alienation, but I think I prefer to store it away for a post focused only on the love story. The most important part here is that he doesn;t even need this, something which may well have alientaed him in the real life, to be portrayed as a foreigner in his own country.)

This is interesting to me not only because it weaves itself seamlessly into what I was talking about previously, the multirealities. I think looking at her through lenses coloured with understanding just how much of a stranger she was everywhere and with everyone, we may begin to understand the way she portrayed Robespierre, most importantly in Thermidor.

Maxime is presented as someone who does not have much in common with his fellow people, and despite working, ultimately, to preserve/save the Republic, his methods seem so unorthodox he is more than once suspected of a treason, most notably in Thermidor as a whole, but also in The Danton Case, when he vehemently disagrees with arresting Danton. This last scene is important on more than one level, actually, because the suspiscion spreads to more than just having potentially erronous opinions, he is also alluded to be gay, which is a small thing (in the universum of these plays this is like the smallest thing of all one could be "charged" with), but still, it is something which deviates from the norm, putting Maxime - and anybody who follow him by proxy - outside the circle of what is considered normal and approvable.

And in Thermidor we see it on two different fronts, which are both very unlike each other, but they tend to the same goal. On the mental level, Maxime is a foreigner, because he is not even human (he's a "sterile god", as Billaud puts it), which I discussed more broadly HERE; and he was on few ocasions compared to plants, animals and objects, making him less humane as a result. He is also very far removed from his usual social circle, both in terms of mentality - his vision spans such a distance no one else can comprehend him - and physical space - he doesn't leave his rooms, when Barere relays the news, the whole Comsal is surprised to hear he has gone out to the streets. Everybody seems to perceive him as a stranger, a foreigner, an extraterrestrial being, an unwanted element not simply because his opinions are faulty (Billaud has similar ones, yes, but what is more important - Saint-Just has the very same ones, and yet the Comsal did not want to destroy him, they only wanted to destroy his friendship with Robespierre; this is very interesting to me and I will focus on this more next time). On the much more factual, physical level, though, Robespierre is a foreign element in his own Republic, because what he has undertaken is, in fact, treason:

Showing through Robespierre that the only way to move out of a stalemate is through cheating his compatriots, and without any remorse about doing so, Przybyszewska dots the is in regards to how she saw the world. Robespierre is such a singular being, that what is a treason objectively - in him is only a hidden mean to a good end. She (probably consciously; she was well aware of the grey zone she lived in and did not mind it all that much) put him outside of any ircle he might belong to, therefore all his choices are in the same time foreign and not maliscious. It's reassuring she at least showcased what happens whena being who is not foreign (Saint-Just) tries as he might to break the fence and either let the alien element in, or join it on a higher level of understanding. Of course, by showcasing it, she only underlined the point I made. This is expecially not-cliche, in my opinion, in plays focused on one of the greatest spurts of patriotism she could think of. Admiring revolutions on one hand, and admitting in the same breath they cannot be saved from within, only from without, only through means that are doubtful at best, is an interesting choice of action, not expected from someone who made it her whole life to proclaim revolution to others.

Making Robespierre become a traitor in the last, decisive stage of his life isn’t, in my opinion, an autobiographical commentary by Przybyszewska, I think it’s much more of a blind spot for her – I don’t think she thought what he has done was traitorous at all, just seen as such due to legal technicalities. It is also a bit like a disease, in that he literally contaminates Saint-Just with his thought:

Not all of them follow Maxime so easily, though, do they? (Also, a side note: in the original, Saint-Just does not speak „matter-of-factly”, he speaks „nearly with admiration”. It changes a lot, if not everything, in what he has just said.) Not all of them are as easily picked up by the wind of new ideas, because they are all too firmly rooten in th ground; Saint-Just I find to be someone on the edge between the two states, he’s way more grounded and at home in the world than Maxime, but not nearly as much as, say, Barere. Ha later admits to following Maxime „mostly” (so not in fullness), he also insists: „you are already burning in the blast furnace of your spirit. You alone.” (so he’s not sold on the idea completely, it’s more that he loves Robespierre and is ready to accept almost everything of his’ at face value). Besides – while I don’t necessarily think it should have been understood literally – there is this one small scene, laden with symbolism:

It is, of course, about death. It is also, equally, about pulling Maxime back to Earth by someone whose head is lost in the clouds a bit less often. Death fits the story all too well, because in this instant Robespierre is tempted to die, because what he has undertaken is too much, yes, but also because he miscalculated, his ideas were too lofty and otherworldy to become applicable (and! don’t even get me started! how his plan was not destroyed by someone hostile to him, but by Saint-Just, whose only crime is being too practical).

Przybyszewska’s writings are full of such creaturs, great minds who cannot 100% find their place in this world, and, more often than not, the end they meet is death. Her other French Revolution heroine, Maud de la Meuge, is the one who scarcely avoids it, by means of a concoluted (and, frankly, a little banal) plot, but the words from this play fit here very well:

Of course, no one would dare to talk to Robespierre down so, but the thought remains. And if Przybyszewska were ever able to finish Thermidor, he would have died, too, not because his story follows the original as closely as could be done in the circumstances, but because he’s doomed from the beggining by his overgrown genius.

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#Maximilien Robespierre#robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#literary analysis#frev#French Revolution#the danton case#sprawa dantona#thermidor#saint-just#antoine saint-just#ninety-three#dziewięćdziesiąty trzeci#rewolucja francuska#pollit

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

My interest in Robespierre was born while watching the film Danton. I think I discovered Stanislawa Przybyszewska in Wajda's film, although Wojciech Pszoniak's superb performance had a lot to do with it.

Finally answering this:

Thank you, @saintjustitude for asking me to rant—I adore doing just that :]

(First of all, thank you to everyone for waiting. I know I took a lot of time to write this, but I had only around an hour free every day, and I usually spent it searching for sources. My knowledge is limited; the play isn't available. I rely on memoirs, interviews, and reviews.

My inbox is always open, and if anyone has any Wojtek questions, I'd be absolutely delighted to answer them. And I mean it. It can be anything.

Every quote was translated by me. All my sources are listed.

Unfortunately a part of it wasn't saved, and I don't have access to some info anymore but this post will probably serve as the beginning of a longer thread.)

And now: “Sprawa Dantona” (1975).

1. How did it all come to be? Why was ‘The Danton Case’ and not any other play?

When I say ‘Danton’ directed by Wajda, most probably think of the 1983 version, a political metaphor: Comsal representing the Polish government, Dantonist representing Solidarity. Was it like that originally? Was Wajda just calling for a fight with the government, transforming Przybyszewska's work to fit his own narrative?

In short: No! (At least if we're referring to the 1975 version, the film is completely another story; I'll gladly make another post about it.).

Zygmunt Hübner (I have mentioned him already in this post) chose Wajda to direct the play even though the latter was a relatively young director; something was telling Hübner that giving the play to him would be absolutely necessary. Pszoniak later referred to that event as Wajda being cast in it as much as he himself was.

The play was simply a way to introduce the artistic team Hübner created. There was none of some “noble patriotism’ or 'anti communism'. (None of what Wajda described as the purpose of the later film.)

Why was that play in particular chosen? That is unknown.

“The idea [of exhibiting that play] came from the fact that Hübner was looking for a play (…) that would present his artistic team as a whole, which he assembled with great imagination and intuition.”

At first, Pszoniak laughed into Hübner's face when offered the role. He thought it fine, intruiging, but the character of Robespierre was so foreign to him that he couldn't give anything from his own person or his own experiences to his Maximilien.

He asked for the role of Danton; that role seemed to fit him way better with "his [Danton's] sensuality, his dynamic physiognomy, and his balls."

Wajda and Hübner were quite insistent and more or less forced Pszoniak into the role.

“Hübner and Wajda were so stubborn that they did not take my objection into account. Nothing there [in the role] suited me; there was no starting point for the role. I had no right to play it. But they convinced me for so long that the whole situation with ‘The Danton Case’ became a dead end.”

The transformation from simply a good play to something entirely political in Wajda's eyes was very slow but steady. On that a little later.

2. Pszoniak wasn't ready to play Robespierre? How did he prepare for the role then?

It's very important to note that it was not bad will that made Pszoniak initially refuse the role, but the theater typecast he was put into and which he almost got used to. All of his power and stage presence were connected to his own physicality, to this sort of mobility and expression that he had to (presumably at Wajda's request) abandon while playing Robespierre.

Wojtekspierre getting his hair cut from a man with surprisingly modern glasses

Whether he was in a tragedy or comedy, it was the unique liveliness that made him so different. Suddenly he was offered the role of Robespierre, a man he only knew from unfavorable history books, portrayed a certain way by Przybyszewska, and he's made to stand before the expanse of that character's personality in a try to make him someone physical.

While it might seem quite shocking, when preparing for the role, Pszoniak didn't even read any Robespierre biography. Why? According to him:

“I didn’t think at all about a historical figure, and besides, you can’t play any historical figure. I put aside the books on the French Revolution. I read them much later, when, years later, in Paris. (…) I didn't want to portray a historical figure, so I didn't judge or evaluate him. I simply tried to get closer to him, to understand him as a person. Przybyszewska herself made it easier for me. The text of the play clearly indicated that she was fascinated by him. (...) Przybyszewska constructed this character in an unusual, enigmatic way. I clung to this fascination, it was a reason for treating Robespierre with empathy. This is a necessary condition for creating a character, without empathy you will never be able to get closer to the man you are to become on stage. Wandering through the labyrinth of his emotions, motives for action, opinions he expresses, I became so strongly attached to him, he took over me so much, that as a result I became Robespierre-Pszoniak.”

Pszoniak admitted he didn't want to play a politician [but, of course, as we all know, he was later forced to in ‘Danton’ (1983)].

The preparations took time and patience (especially from his wife - Barbara). Pszoniak tends to describe it as a painful process. Robespierre's physical expression was compared to being bound tightly by his own flesh, almost imprisoned by it, but freed by his mind. Pszoniak realized that all of the power in portraying Robespierre could only be gained from a deeper reflection. How to show a mind on stage?

That Pszoniak didn't know, and so he made the decision to show Robespierre's determination and faith instead of simply a calculated brain. To show a path, an objective. That's why the last scene was so hard to play (conversation between Robespierre and Saint-Just after Danton's death); he even asked Wajda for a white cloth as a makeshift shroud. To Pszoniak, that scene meant the symbolic death of his character. Robespierre (described by Pszoniak as a “very intelligent man") feels that inevitable peril awaits in the near future. The actor often described a feeling of mourning something or someone after the performance.

The challenge of creating the role, in the words of Wojciech Pszoniak:

“I started to control all my reflexes morning till night; from waking up to falling asleep, I was destroying myself. In everyday life, even the smallest activity, I slowed down; I was reducing and cleaning up [every one of] my habits. Torment, the absolute torment of controlling yourself, of managing yourself. Zero spontaneity, the phone rings, my first reaction—run to answer it—I stop myself calmly, in control of every slowed-down gesture. I imitated Zygmunt Hübner's focused gait; I noticed how he placed his feet. And I started walking like that myself. That's how I set a different, more controlled way of moving. After that, I turned to gestures, head movements, the way of getting up, and gesticulation. I felt that I was different. Acquaintances and friends both asked where this change came from. I suppressed the dynamic, extraverted myself.”

And

“I was pushing the boundaries of supervision [over myself], checking how I would behave after drinking a larger amount of vodka. One day I went out with Basia [wife] and friends (...) After a few bottles, at four in the morning, they were amused, cheered up, asking if I was sick because I was behaving like a machine. After three weeks of suffering, I reached ground zero. This happened during the rehearsals. A conversation about Robespierre and Danton. I joined the discussion, exclaiming, 'I disagree!’ - and suddenly I saw that my hand was no longer my hand, that it was not the hand of that Pszoniak that I am, but that it was already a hand—the beginning of someone else.”

3. What of Danton?

Here the problem with the play began. The man cast as Danton, Bronisław Pawlik, was just... terrible.

He was a good actor in general, definitely, but in short (explanation for the anglophones), it was like casting Danny DeVito as Danton.

He was short of stature, weak of voice, much older than Pszoniak, and simply unfit for the role.

He didn't have a stage presence; his voice was silenced by the other people on stage, and Pszoniak kept acting as if there was some great, dangerous opponent when there wasn't—the audience seemed to notice it.

It all added to a kind of feeling of resentment after preparing so long for the role of Robespierre.

Danton (Bronisław Pawlik), Camille (Olgierd Łukaszewicz) and Westermann (Franciszek Pieczka) celebrating

Pawlik was more concerned with the position of the props or the costume instead of conversing and shaping their roles. To Pszoniak it was the role of a lifetime, to Pawlik it wasn't.

“The audience was sitting on the stage because the entire theater had been transformed into the Revolutionary Tribunal. Here, a powerful voice and a [kind of] broad gesture were needed... Pawlik's charm disappeared in the feverish crowd. What consequences did this have for the play? Enormous, Danton was deprived of the strength [for both the audience and actors] to believe that he posed a deadly serious threat to the revolution. And this lack bothered me terribly...”

4. How did it become political then?

As I have previously mentioned, it was a slow, steady process. Even Wajda himself didn't think much of the play; it was the audience that began the change.

As the first example, Pszoniak recalls a scene when Eleonore comes in with tea but not sugar—in the audience at first only a few laughing, but gradually along with the many performances it turned into the whole audience cackling. The play was exhibited just when a time of increasing problems with sugar supplies began in Poland (food stamps for sugar were introduced).

Pszoniak admitted that the cast would often laugh along with the audience. It seemed almost absurd—a tragic play blending with the real world.

When it comes to Pszoniak himself in that time, the more he played the role, the more it felt like “punching the air.” Instead of having a genuine conflict, he had no support, no reference point in Pawlik as Danton or the audience. For the role to have meaning, to be something, it all had to be a matter of life and death. His co-actor was slipping into comedic grotesque while playing the second main role.

"The success of the play was huge, but the audience was eager to read the play [only] in the context of political allusions. (…) The audience felt that something was happening [on and off stage], (…) the tension grew."

The audience's reaction seemed to be a direct answer to the Danton shown on stage. Instead of a political opponent, there stood a sad, tired victim of the committee who seems completely and utterly innocent, all his words said with a kind of saddened charm (doesn't that remind you of a certain film Wajda made later?).

5. What of the other actors?

Here is where I have the least information. If anyone has any more sources of information, actor memoirs, etc., feel free to reblog this post with additional info or simply contact me about it so I could make Part 2. :]

The cast.

I have to tell you something shocking... Wajda is capable of giving actual, normal characterization to secondary characters (gasp, thunderstrike, wolf howling).

Or perhaps that was just the actor/Zygmunt Hübner (I guess we'll never know).

The most information I could gather was about Saint-Just (played by the excellent Władysław Kowalski).

Based off the limited amount of reviews I could gather, he was a positive character in general. Described as “a man gifted with exceptional warmth and [someone] unconditionally devoted to his cause” or “full of raw passion."

AND HE GIVES MAXIME FLOWERS IN THIS VERSION AS WELL, EXCEPT IN THIS ONE ROBESPIERRE (KIND OF) SMILES!

I couldn't find much on Eleonore, Louise, or Lucille, though I've searched and searched for a few days. All I could find is that the actresses were excellent—that is, unfortunately, no source of any relevant information. Frankly speaking, since Wajda, in kind words, doesn't excel at writing women, I don't have much faith in their characterization on the director's part.

Camille played Łukaszewicz is usually called a “complicated youth"—that is, of course, an opinion—or “spontaneous in reflexes"—that's a bit better of a description. As you can see, I am limited by the fact the play isn't available, and I must depend on biased or subjective sources.

Worried Camille Desmoulins (Olgierd Łukaszewicz) - I do think this Camille looks quite nice.

6. And did the critics like it? Was it well directed?

In short, it was a very, very liked play by both the critics and the audience. It ran for 5 years; it ended around 1980, when many of the actors simply left Poland.

About critics and reviews written by them: What surprised me immensely is the fact that most available reviews (written before the release of the film ‘Danton’) of the play weren't anti-Robespierre. The play is often described as something of a moral discussion, something for the viewer to assess, a work that doesn't suggest one solution to understand the conflict, or revolution (in other words, a great play).

A thing I've noticed is that along with time, the descriptions of the main characters seem to change. Danton—in earliest reviews described as “absolutely repulsive," then later as a tragic man, someone who adores life. Robespierre—in earliest reviews described as an absolute “marble statue," an idealist, someone pure, then in later reviews as just a fanatic.

7. What about Wajda? Did he change the text much? What about the scenography?

I was surprised to learn that Wajda absolutely could make a good, Przybyszewska-accurate play.

From all I could find, there is not much I can accuse Wajda of when it comes to ‘The Danton Case’ stage adaptations. It was made very well. What most likely contributed to the later change in people's mentality when met with the play is the fact that the audience was sort of a part of the performance. How? Like this:

“It [the play] takes place on a stage placed in front of the audience; on the actual stage and in the rest of the audience sit in rows of chairs rising upwards. Everything encompassed by the scenography is one theater. This played out brilliantly in the second parts, in the beautifully composed group scenes, where the audience not only looks at the stage but is drawn into it as an extra audience at the hearings of the revolutionary tribunal.”

And

“Wajda made "The Danton Case" as if against himself—against his previous self: he gave up on visual effects, music, and symbolism. He built a spectacle—a spectacle indeed!—raw and beautiful. (…) During the (…) presentation of "The Danton Case," seats for viewers were also installed on the stage, which was fortunately spacious, the audience surrounds the actors, the actors are among the audience, on the balcony, in the passages.”

If Danton or Robespierre were so close to the audience, I think it really did influence the people's opinion of it later on. Pawlik was terrified, jumping like a fish out of water from one audience member to the other, and there was Pszoniak, white and still under his shroud just a few meters away. That did certainly change the performance's reception.

8. Where can I watch this?!

As I have mentioned here: the play isn't available online, but most certainly is somewhere in the archives (confirmed by Pszoniak), when it was supposed to have a TV debut the martial law was introduced, and a few years later everyone seemed to have forgotten about it.

So, erm… Who's raiding the archives with me? (By the way, fragments of the play exist online, but only 10-20 minute excerpts, so if I find the time, I'll try to track them down.).

Sources:

Books:

Aktor. Wojciech Pszoniak w rozmowie z Michałem Komarem, Wydawnictwo Literackie 2009;

Maciej Karpiński, Pszoniak, Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe Warszawa 1976;

Małgorzata Terlecka-Reksnis, Pszoniak. Fragmenty, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie 2024

Photos used and play reviews (pardon the rhyme):

http://encyklopediateatru.pl

65 notes

·

View notes