#kazimiera ingdahl

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The following text was presented in Polish, under the title „Mortal deities of hidden thrones. Maximilien Robespierre in Thermidor as Stanisława Przybyszewska’s alter ego” during a comparative literature conference in May his year. My idea of in what part my PhD will be about her, and what I can and cannot publish before is still taking shape, but I really wanted to put this out here.

Stanisława Przybyszewska is remembered in the collective consciousness primarily as the author of „The Danton Case”, and secondly - as a lonely, unhappy person, living in isolation and enduring miserable living conditions of her own free will (in some sense even at her own behest). Thanks to this way of looking at her, it’s easy to classify her in the studies focusing on her, in various, constantly recurring orders, and everything that is less obvious than these two facts can be omitted equally easily. Since she is known mainly as the author of „The Danton Case”, naturally her second great drama, „Thermidor”, is being pushed to the side. And it is precisely here that her biography is reflected in the character of Robespierre, her idol and deity. When I talk about being reflected, I mean, of course, the construction of Robespierre as a person in a drama is done according to the same pattern that Przybyszewska's life in Gdańsk has followed.

What pattern was it? First of all, we are talking about an existence that is not only lonely, but also aggressively hermit-like. Przybyszewska is not only stubbornly stuck in Gdańsk, with which she had nothing in common with and which she didn’t even like, but she also rejected help from her family and the few friends; loneliness of this kind naturally involves a certain attitude towards the world and a certain view of the world. Here I would like to focus on the facts extracted from her biography, and only those that can be recorded in a somewhat visual way, because only this type of simple, inalienable information is the one that could have found a place in her drama.

The most important facts from Przybyszewska’s life: - Loneliness - Hatred - Hierarchical view [of the world/reality]

The first fact is loneliness, understood both in the physical and mental sense. The second was her hatred of people, which was not (most likely) a result of a flaw of character (unless we consider her severity to be a flaw), but rather of a complete misunderstanding that she met with at every step. In her opinion, this misunderstanding had a simple cause – it was her own genius, which she sensed and which she tried to develop in her creative work. The third fact is the specificity of her view of the world, based on a hierarchical view.

Facts from Robespierre’s life: [obviously I am talking only about his literary counterpart, and only in Thermidor] - Loneliness - Hatred - Being conscious of his existence within a certain hierarchy

Przybyszewska smuggles these three undeniable and simple facts into „Thermidor” as features defining one of the characters, Maximilien Robespierre. He also exists in seclusion - although he is undeniably the most important character in the play, he is not only absent throughout Act I, but he only exists when his absence is being talked about.

„And here we can refer to the geobiography, because Przybyszewska places her hero in conditions close to her own living situation: her Robespierre lives in a «Parisian cubicle resembling a kennel» and washes himself with icy water. [...] Robespierre's cold Parisian cubicle corresponds to the short description of a room in a barrack, made by Przybyszewska between 1927 and 1928 in a letter to her cousin, Adam Barliński: «a crumbling ice house, deprived even of running water»” (Marcin Czerwiński, „Uskok”) -> LONELINESS

Using historical knowledge, Przybyszewska places Robespierre's apartment in a lonely room in the house of a friendly family - but drawing from her own life, she definitely enhances the „vibe” of his place of residence in such a way that it corresponds as closely as possible to her own living conditions. This is not supported by historical evidence, because it is known that in the Duplay family, Robespierre occupied two comfortable and normally furnished rooms, the standard of which did not differ from the standards in 18th-century Paris.

„The present study, however, argues that in fact she takes a Gnostic view of history as an eternal opposition between matter and spirit, and that this dualism saturates the utopian project she undertook both in her art and in her life.” (Kazimiera Ingdahl, „A Gnostic Tragedy”) -> ASCETISIM

However, for Przybyszewska, deprived not only of the luxuries of everyday life, but also of even a semblance of normalcy, it seemed unthinkable to grant the person she depicted in her works - in „Thermidor” more than anywhere else - the very luxuries that she herself was deprived of, and which she didn't even miss that much. Przybyszewska loved Robespierre and considered him to be the highest being, which, due to her Gnostic view of the world, was combined with her love of asceticism. Asceticism, the rejection of the material world, is one of those practices that allow us to rise higher on the mental plane, so it was, according to her (and certainly: according to her Robespierre) indispensable of.

The second point of contact between the writer and the character is hatred. The topic as such appears frequently in her prose, but in her dramas it appears only in these two lesser-known ones; as if she couldn't write about hatred in a more „domesticated” way. Przybyszewska rewrote each scene in „The Danton Case” at least 4 times, usually 10 – „Thermidor”, however, is a play written first and not even completely finished, so there are a few stylistically jarring places in it. From the point of view of this essay, the most important thing at this point seems to be the description of hatred from the mouth of Robespierre himself.

„In fact: I literally had a fever while writing. Everything is boiling inside of me. I cannot give you any idea of how much I suffer terribly with this absolutely powerless rage in the face of stupidity. When I first read this article, I regularly felt physically sick: I couldn't eat for hours. Besides, the blood rushed to my head so much that I was careless by putting it under the tap. Such bodily symptoms never reach the level of rage in me because of my own affairs.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> HATRED

This corresponds with Przybyszewska’s views; she spent her adult life without finding understanding or friendship among people (or at least friendship on her, harsh and inaccessible, terms), and so she felt hatred on a similarly physical level; even if she admitted that she didn't feel that way for personal reasons.

The same can be said about Robespierre, who hates not a single man, but what a man aspires to. There are more mentions of hatred in Przybyszewska's rich epistolography, and in the creation of Robespierre as a literary character in „Thermidor”, „The Danton Case” and „The Last Nights of Ventoese”, in fact, there are more - in this essay I only want to highlight this similarity as something more than similarity, as pouring of the writer's personal experience into the „personal experience” of the character.

„When you read and interpret [Przybyszewska's] correspondence, dramas and prose, after some time you begin to notice the constant presence of evaluations - of the world, people, their behaviors and achievements - with a dominant black, negative tone. Przybyszewska must always know and say precisely whether a person and a work are great and outstanding, or small and unsuccessful; whether she is dealing with the first or fourth „level” of creators. (Ewa Graczyk, „Ćma”) -> HIERARCHICAL VIEW

The third similarity is what Ewa Graczyk has called the „hierarchical view” and there can be no doubt that Przybyszewska - by adoring Robespierre, admiring him, idealizing him in her plays - transmits this trait of hers onto him not so much consciously, but because the hierarchical nature of her gaze is an inherent part of her as a person and she is unable to create a universum which would operate according to rules other than those she herself had adhered to. And hierarchization is closely related to hatred.

„During the winter, I suffered from a fear - as incredible as it was downright unpleasant - that I had come too far for my years. While last year with every page I wrote, bad and clumsy as they were, revealed to me the beginning of some line of development, thus marking all the directions of the path destined for me, which I immediately tried to follow - now this comfortable feeling of apprenticeship, of beginning, suddenly left me. I have not abandoned my path, the only one that suits my personality and that I have recognized from my mistakes. But the anticipated goal was achieved. Already. It terrified me. I thought I had gone all the way around in one year. There was nothing left for me to do but die.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”)

Robespierre, placed in a situation undoubtedly much easier to bear than Przybyszewska was, does not share with her similar dilemmas. Why? Because Przybyszewska all her life was afraid that she was not good enough - or maybe she was not so much „afraid” as she was convinced that she had not yet reached the peak of her abilities. Robespierre, on the other hand, although from time to time he may experience dilemmas related to not knowing whether he sees and assesses the situation correctly, knows for sure that although he may not be the greatest, at the same time, there is no one greater than him. Therefore, Przybyszewska's fear and uncertainty are not foreign to him; altough the same cannot be said about her irritation and anger, and not her appraising, mathematical view of other people.

It is clear that Przybyszewska poured her life experience into Robespierre; she probably did not have many other opportunities to narrate any literary work - in all her works not only the same themes or types of people are repeated, but also the same solutions and considerations. This results from her own character, but also from one more thing, closely related to the hierarchical view: her isolation took place at the ground level. This is both in its metaphorical and literal meaning: Przybyszewska lived in her barrack, rented to her out of pity, separated from others only by too thin walls, and nothing else. What is missing in her life is the introduction of some distance that would allow her to consider her situation as something other than - depending on her mood - a deep misfortune or a forced, but at least temporary, stop on the way to somewhere greater. It is a position on the same level as everyone else, or even worse than that: it is a position among people whom she considered lower than herself, but for which she had no evidence.

„During the winter, I suffered from a fear - as incredible as it was downright unpleasant - that I had come too far for my years. While last year with every page I wrote, bad and clumsy as they were, revealed to me the beginning of some line of development, thus marking all the directions of the path destined for me, which I immediately tried to follow - now this comfortable feeling of apprenticeship, of beginning, suddenly left me. I have not abandoned my path, the only one that suits my personality and that I have recognized from my mistakes. But the anticipated goal was achieved. Already. It terrified me. I thought I had gone all the way around in one year. There was nothing left for me to do but die.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> GEOMETRY OF EXISTENCE

At this point, it is worth returning to this fragment and taking a closer look at the underlined fragments. Przybyszewska thinks about her life using vocabulary related to geometry (she briefly tried to study mathematics in her youth). However, this geometry is flat, located on one plane - a line, a circle, a designated direction. She has no space to breathe. And this is not only due to the forced pause in creative work, but also – more of an everyday problem - because of her room:

„My current apartment measures 2.25 x 4.60 metres. Measure it and you will see what it means. On top of that, there's a window – half a size of a normal one.” (Stanisława Przybyszewska, „Letters”) -> GEOMETRY OF EXISTECE

There is little space, then, in any sense of the word, and she can only spread her wings through Robespierre, whom she admires but whom she secretly would also like to be: his room, at least, is upstairs. I say this sentence a bit ironically (although it is true), just to emphasize that he actually had more space. And when he left, after he disappeared from the political scene for some time (as it is the situation at the beginning of „Thermidor”), he moved away from people in more than one dimension.

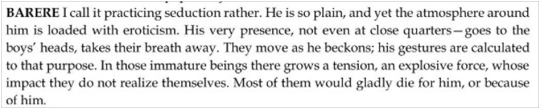

And this simultaneous elevation to heights, even if only heights of a second floor, and remoteness from people in every other possible respect, is what pushes Robespierre's opponents to understand him in terms of divinity. There is not much in it of praise, more of a statement of fact that must be accepted before it can be refuted. So what is Robespierre's divinity in Thermidor?

First of all, it is his inherent feature, the lens through which others must look at him. It's not just those who know him personally and work with him - it's about France in general. But the point is not to list all the moments in which one of the characters recognizes Robespierre as a god - let's consider it as a fact, just as they recognize it, and let's get over it to ask ourselves: what does this mean?

The main meaning is panic. Przybyszewska, through Robespierre, at least partially fulfills the dream of achieving success and the associated with it strong reactions of the world to the presence of such a successful person. Fear in this case is the highest form of flattery, except perhaps sincere (really sincere) devotion. This fear is both an expression of hateful admiration and a driving force behind the characters' actions. It results from a reluctant but unwavering faith in the divinity of their opponent and it is transformed into taking action, into an attempt (as history shows and as Przybyszewska would have shown in the play if she had completed it: a successful attempt) to overthrow the one who is a god, but not a guardian. Whoever keeps his divinity locked inside himself cannot get rid of it, but he does not make it a gift to others, but rather a curse to himself.

-> MORTALITY OF A DEITY

Because Robespierre is a mortal god. Przybyszewska created thorugh him something like a parody of Christ: a man-god in whom each nature is equally weak and each loses. Since each of them loses, then, unlike Christ, each of them dies. He actually „is burning in the blast furnance of his spirit” - because he makes decisions that bring about his own destruction. This is similar to the situation of Przybyszewska, who – so it would seem - did everything in her power to alienate the people on whose financial support she depended; who stubbornly stayed in Gdańsk instead of moving to one of the cities where she could receive more help from her family; who refused to undergo addiction treatment even under the threat of losing her government stipend. Her own non-humanity is inscribed in her through pride, to which she openly admitted and called „satanic” – she is linked with mortality in the same way.

In Robespierre, humanity and divinity combine in an unusual way: he worships himself, he’s convinced of his extraordinary power, and every matter he undertakes confirms this belief. But what is a monstrance if not a kind of visible concealment? What is the meaning of his long, six-week stay outside the French political scene at a time when he is needed there the most?

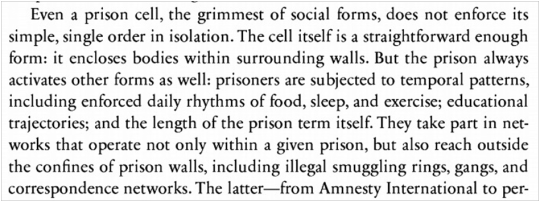

In her book „FORMS: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy and Network”, Caroline Levine proposes the introduction of the term „affordance”. An affordance is an action that is hidden in a given object or concept; an action forced, as it were, by a form that is itself a kind of oppression. In „Thermidor”, the form that has the greatest importance for the plot is an enclosed space. On the one hand, we are talking about the meeting room of the Committee of Public Safety (Przybyszewska preserved the unity of the place in the drama), and on the other - about Robespierre's apartment, which is only briefly mentioned.

-> AFFORDANCE OF HIDING

His withdrawal and his absence create anxiety among his opponents. The fear mentioned earlier is related to how the other revolutionaries feel about Robespierre as a person - but there is more to it than that. His absence, which does not prevent him from having a perfect understanding of the political situation at that time, has something uncanny about it. He himself puts it best: “There is something uncanny about this business. It is as if one discovered venomous teeth in a paper snake, or a hangman's rope in a young girl's sewing case [...]”. There is a reason why these comparisons make us feel uncomfortable: they violate the natural affordances of the cases mentioned, since paper should not be venomous and a sewing case should not contain a hangman’s rope. A room in a family home should not in any way resemble a place where a dangerous animal lurks [in the Polish version Robespierre is being likened to a spider] - and yet Robespierre evokes this type of association in others, probably without being fully aware of it himself.

„I remember that I saw her several times in the morning hours, walking from her apartment (in the barracks) through the courtyard of the Gimnazjum Polskie, sideways and stealthily, so much so that it was difficult to see her face.” (Ewa Graczyk, „Ćma”) -> COMING DOWN TO EARTH

His throne – his altar – is hidden, therefore it’s deprived of contact with the earth and its inhabitants. When, after a few weeks of absence, he decides to come down, he causes not only panic, but also simple surprise. This is not far from the personal experience of Przybyszewska, who at some point began to avoid going outside, and when circumstances forced her to do so, her appearance caused quite a surprise among onlookers - and (just like Robespierre) she was at odds with people both on „the sidewalk plane”, and on the mental plane.

-> FALLING DOWN ONTO EARTH

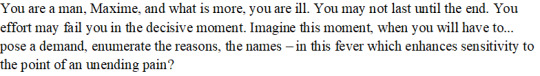

However, the mere physical descent to earth does not mean that Robespierre has left the spiritual and mental heights on which he dwells as a deity. Saint-Just's warning is not just mere words, but an expression of concern about the entire situation that Robespierre has just unfolded before his eyes - a situation that is almost impossible to solve and poses a real threat to the „paradise on earth” for Robespierre is the Republic. Falling from a height is also a threat to the spirit and a reference to the fall of Satan.

-> A LITERAL FALL

It is also simply a signal of the beginning of defeat. The affordance of the closed room was violated, so by getting rid of his loneliness and separation, Robespierre also deprived himself of their positive aspects. The mortal god descended to earth, thereby shedding the protective layer provided by the distance between himself and others, between his plan and the reality in which he lived - and his opponents, whether in human form or in the form of a natural course things, they immediately took advantage of the situation. And here we can find a reference to the situation of Przybyszewska, who at some point started to avoid seeing her friends from Gdańsk – a married couple Stefania and Jan Augustyńscy - because Stefania was, in Przybyszewska's opinion, too perceptive and did not fall for the artificial distance put between them through the words of „Everything is fine”. Thus, the writer trapped herself in the form and allowed it to turn into a prison. This kind of action somehow justified her and took away the responsibility for improving her life.

(Caroline Levin,e „FORMS: Whole,Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network) -> AFFORDANCE OF ISOLATION

Any form is a type of oppression. By imposing its order, it also forces the way of seeing and thinking. Robespierre's paranoia did not appear out of nowhere - it is the result of isolation (the only person who acts as a link and a buffer between the closed form of Robespierre’s private room and the closed form of the meeting room is Saint-Just - and Saint-Just has been struggling with the war on the Northern front for several weeks). It is no different with Przybyszewska herself, whose attitude towards the world was largely dependent on her financial conditions, which she did not try to improve: "Since [Staśka] is not crushed by the grey of everyday and by the struggle for a piece of bread, the general hatred towards people and constant fear of them ceased” wrote her husband in a letter to Helena Barlińska.

-> THE DUAL NATURE OF AFFORDANCE

When it comes to affordance, there is one more detail we need to pay attention to. The physical form - in this case, a room - influences the spiritual form, but it also works the other way around. Robespierre's paranoia is therefore a factor whose affordances (e.g. haste, keeping a secret, high treason) have a real, negative impact on the Republic in general and his life in particular. Acting under the influence of the conditions he himself has created, he finds himself on the road to making more and more mistakes, making the situation worse, and driving himself into a dead end. The fact that he does not seem to take this possibility into account points once again to his divinity and the pride that comes with it.

-> THE AFFORDANCE OF ROBESPIERRE

From the depths - and heights - of his tabernacle, Robespierre commands the situation. He exerts an absolute influence, which at the same time is based on nothing more than his person. Therefore, it is his personal affordance, the effect not of a specific action, but rather the result of his presence in the world, the resultant of all his features. This is where he differs from Przybyszewska, who dreamed of having such an influence on the masses, or at least on a group of people. Thus, this confirms the thesis about constructing Robespierre in „Thermidor” as her alter ego - similar enough to be confused with her, but better and more powerful.

I would like to end here and take advantage of the opportunity to mention that after 216 days of genocide in Gaza, as of the day I have delivered this essay, there is no university left there. We have the right and opportunity to promote science, and therefore we also have an ethical obligation to stand on the side of the victims of genocide, who were deprived of this right and opportunity. I hope that in our lifetime we will see a free, independent Palestine.

#I WHOLEHEARTEDLY ENCOURAGE YOU ALL TO ALWAYS MENTION PALESTINE WHEN YOU'RE GIVING A SPEECH#IT IS WORTH IT AND WE ARE MORALLY OBLIGATED TO DO IT#stanisława przbyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#thermidor#maximilien robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#robespierre#affordance#ewa graczyk#marcin czerwiński#caroline levine#kazimiera ingdahl#literary analysis#comparative literature

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

@sprawa-przybyszewskiej

Here--I guess--is a partial “review”/critique of Ingdahl’s book about Przybyszewska. It’s long (I tried to make it like the rough draft of an actual essay), but I hope it makes sense. :’)

In Kazimiera Ingdahl's invaluable and thorough study of Przybyszewska's work, Ingdahl at one point (lmao, I can't find the exact quote atm, but I don't think I'm making it up) draws attention to the tension between Przybyszewska's idealized Robespierre and what she [Ingdahl] calls the "truth" of history. However, Ingdahl's understanding of the historical "truth" of the revolution is very biased and Dantonist.

1.

After dismissing the evidence of Danton's corruption, she provides for the reader "a brief account of the political situation in France during this period." According to her, Danton's program was "soberly realistic and pragmatic" in comparison to Robespierre's "spartan egalitarianism." She emphasizes that Danton wanted to rebuild commerce and industry by ending government restrictions and regulations of the economy, provide individual freedom, and end both the Terror and the war. She mentions Vieux Cordelier as the outlet for Dantonist politics, and of course explains that in his newspaper, Desmoulins denounced the policies of the Terror and advocated for clemency. "The Dantonists," she writes, "favored a pragmatic stabilization of France and had little patience with Robespierre's utopian notion of an 'Ideal Republic' based on the 'rules of political morality.'" In short, she makes Danton the consummate freedom loving, market loving bourgeois.

This is an extremely simplistic narrative. I won't go into each point, so I will just focus on the most prominent myth: that Danton was a down-to-earth peacemaker compared to the frigid, virtue obsessed puritan Robespierre. Regarding Danton as down-to-earth peacemaker, major historians of the Revolution would take issue with the assessment of Danton's program as "realistic and pragmatic." The staunchly Robespierrist Mathiez, who Przybyszewska respected most among the scholars of the revolution that she read, writes that if the Dantonists had been successful "before Toulon was taken back from the English, before Hoche chased the Austrians out of Alsace, even before the revolutionary government was fully organized, before the Maximum was assured in its application, the Dantonists would have shattered the revolutionary endeavour . . .” And here, he was just noting his agreement with the older historian Jaurès. Mathiez goes on: “He [Jaurès] has also noted that their policy of hazardous and outrageous moderation led to an inevitable alliance with the monarchists . . ." And he then lists evidence of corruption and treason that he discovered in his own research, making the case against Danton more compelling (if not quite conclusive) since Jaurès’ time.

The more cautious and circumspect Lefebvre is less blunt in his assessments, but he too notes the disadvantaged position from which Danton was attempting war-time negotiations, as well as the opportunism, corruption, and scandals that tainted the endeavor. These are both "pro-Robespierre" Marxist scholars, but Lefebvre can hardly said to be in the "hagiographic" tradition that Ingdahl is aware of and cites as Przybyszewska's bias.

Ingdahl also doesn't mention Robespierre's own attempts to moderate the terror nor show a deep understanding of the balance of political forces during 1793, which provides the context for his "utopian" (democratic) ideals as expressed in his speeches about "virtue and terror." In a word, she simply accepts the myths and caricatures about both Danton and Robespierre.

2.

I suspect this bias on Ingdahl's part causes her to misread some of The Danton Case and Thermidor. Because she either doesn't know or doesn't accept scholarship against Danton and explaining Robespierre's decisions, she overlooks one of the (very valid) points Przybyszewska was trying to make about the actual historiography of the Revolution. In one of her letters, Przybyszewska writes:

I have the desire to beat into the mushy interior of the public brain a new image of the Revolution, an image which would not do a terrible wrong to a number of its heroes … but I know only too well that I won’t attain this goal. For one hundred and thirty-five years they have had an image of the Revolution that is incomparably simpler and much more comfortable, from both an intellectual and moral point of view. That’s something that won’t be given up so readily.

Unfortunately, Ingdahl was also unable to give up one hundred and thirty-five years of Thermidorian propaganda when writing about Przybyszewska. However, Przybyszewska herself saw the smearing of Robespierre's name as a historical injustice that she wanted to fight. She alludes explicitly to this injustice within The Danton Case when Danton, climbing the scaffold, unleashes a curse: "A few years from now my name will shine in luminous letters in the Pantheon of history, while yours--you villain Robespierre--will be imprinted forever in its indestructible black book!"

3.

The meta-commentary on the historiography of the Revolution may connect with the theme of lies and truth, which are also connected to the gnostic metaphysics, in The Danton Case (and to a lesser extent in Thermidor). For Przybyszewska, lies are central in how a revolution breaks down and regresses:

Robespierre: Until man outgrows this beast in himself, he will time after time rebel and bleed--in vain. Revolution will not survive to achieve its aim this time, or the second time, or the fifth time. Danton's corruption, Danton's lie will after a while outweigh the upward momentum...

Lies go hand in hand with the realm of "matter" and "nature," which to Przybyszewska is a basically satanic evil that veils the higher truths of "spirit," which generate the possibility of human freedom. Przybyszewska elaborates on lies in Thermidor, when Robespierre explains the nature of propaganda: a concept detached from the concrete, runs amuck in the abstract, generating fantasies such as nationalistic fervor.

Robespierre: . . . Within the country the same destructive process is taking place. The citizen finds the war atmosphere to his taste and revels in it; he is even more disgusting than the mercenary soldier, since his pleasure is derived from pure imagination, it goes round and round in a vacuum. His emotions, removed from reality, feed on empty dreams and breed nightmarish visions. And here breaks the umbilical cord that binds man to earth. Phantoms appear in the place of concrete objects. Class feeling is replaced by an abstraction: nationality. The natural hatred of the exploited for his exploiter makes room for the pointless elemental hatred of a Frenchman for an Englishman. Communal feeling takes the form of a perverse idolatry of the French army. Truly, what a splendid organization! A war waged for profit isolates people from each other, and from earth, makes them prey to empty prejudices and groundless animoisities. In a vacant trance, deprived of spirit, these unhappy lonely people are enveloped by the thick fog of lies, breathe them in the place of air, drink them like posion . . .

It is interesting that she, who emphasized the vertiginous heights of reason against the evil of earthly matter, here posits the loss of connection with earth and the “concrete” as the work of unchecked “nature” expressed in nationalistic militarism. She may have been influenced by Freud, who described regression on an individual level as an inward retreat to a realm of fantasy. To me, it looks like Przybyszewska saw the tragedy of the revolution as one of regression on a historical level, the consequences of which continued to reverberate through history in the form of "lies" that sprout in the fields of capitalism and imperialism.

This is important because it brings attention to, not just tragedy caused by the chaos and upheaval of revolution, but the tragedy of what happens when revolutions fail. This changes things. It is no longer a story about how Robespierre has unbearably high standards that he inflicts on others and without him everyone would be able to enjoy frivolous pursuits, the 18th century equivalent of Marvel movie fandom or whatever instead of Robespierre making everyone read Rousseau everyday... because he's such an intolerant snob... and of course he guillotines anyone who doesn’t enjoy it (the propaganda image of Robespierre really is literally like this). Because Ingadahl misses this point and sees only a Thermidorian propaganda Robespierre, not what he is reacting against, she says that Robespierre’s republic “threatens the survival of humanity. This becomes even more obvious in his view that total destruction is a source of rebirth, and he actively tries to put it into practice.” She is refering to his plan in Thermidor to interfere with the armies and cause a foreign invasion, changing the aggressive offensive war into a defensive one. Ingdahl sees his actions as simply him being insane, and she sees his rant against Capital as evidence of it. But I think Przybyszewska’s intention, through the rant about Capital, nationalism, and wars was to have him prophecize the disasters of the 20th century and be driven to desperate extremes to try and prevent it. In other words, Robespierre has an actual altruistic reason for pursuing the hell of revolution: because otherwise there would still be hell, just of a different and even more hopeless sort. This, I think, is an even more bleak outlook than Ingdahl’s reading of Robespierre, so it seems in line with Przybyszewska's "pessimism." It makes it so that the triumph of "lies" has real consequences that Przybyszewska herself was witnessing in her own time, in the aftermath of World War I and rising fascism.

4.

To Ingdahl, however, the binary between truth and lies is extremely ambiguous. She sees Przybyszewska's Robespierre as an anti-Christ and Satanic figure. She is aware that Przybyszewska intended for her Robespierre to be wholly good and heroic, but she also identifies what she considers unintended subtext as expression of a fundamental ambivalence (and maybe a deeper “truth” of history). Indeed, Przybyszewska was ambivalent about revolution in many ways. She emphasizes her pessimism and yet was unable to definitively reject revolution and its quest for the realization of human freedom on Earth as a hopeless endeavor (as conservatives writers like Dostoesvsky and Bernanos did). However, I don't think Przybyszewska's ambivalence expresses itself in her Robespierre as much as Ingdahl thinks it does.

Ingdahl describes Robespierre's tragedy as "ironic" based on a line by Fabre in The Danton Case. Fabre says:

"That's right, careful with the truth, friends. Do you know how one must think in our situation? That the sacrifice offered to an allusion, a useless sacrifice, is the most beautiful. That it is a good thing to wear a jewel, or to give it to a public charity, but that it is beautiful to throw it into the sea. Any truth can be tolerated in a tragic guise; and tragedy is not hard to come by."

Ingdahl explains: "He is referring to Danton's defeat, but the content of the aphoristic monologue summarizes above all Robespierre's predicament." But Przybyszewska would disagree that Fabre's line applies to Robespierre. One of her letters containts echos of the ideas expressed by Fabre:

It would seem that once we do away with sentimental illusions and see human nature dans toute son affreuse misère, and recognize the ugly underpinning of the most spectacular events -- we would then have to do away with the sense of tragedy since it vanishes into the muddy water along with the remants of all those dead concepts which are the cheapest of pleasurable narcotics. But that is not the case. Only two-thirds of what is commonly understood to be included within the word Tragic must be thrown out; there is still left one-third totally invisible to enthusiastic youth. This remaining one-third is intensely real; it is an attribute of heroism, which also exists (but not where school textbooks tell us it is).

To Przybyszewska, Robespierre--but not Danton or his followers--was in that “one-third” of truly tragic heroes on the side of a higher "truth." As Ingdahl obviously understands, the existence of this "truth" that transcends the “affreuse misère” of human nature was important to her, and by extension important to her Robespierre. To them its existence is simply "logical" and necessary (not just pragmatically but metaphysically) as a counter to the nihilism of Danton. In a key moment in The Danton Case, Robespierre echoes Fabre's comments about tragedy.

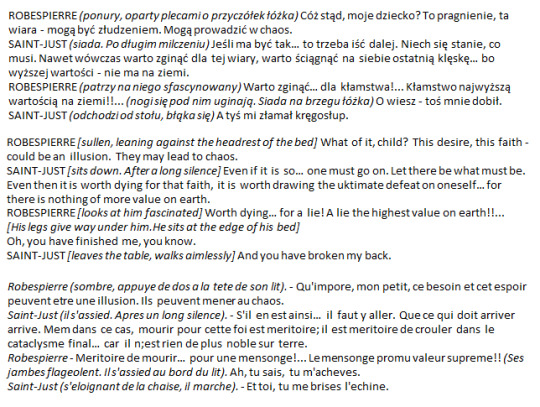

Saint-Just: . . . It was the desire for that freedom and the faith in it which roused the people after ten centuries of pasitivity! The same desire and the same faith have kept it for over four years in a superhuman strain of heroism! Robespierre: [sullen, leaning against the headrest of the bed]. What of it, child? This desire, this faith--could be an illusion. They may lead to chaos. Saint-Just: [sits down. After a long silence]. Even if it is so... one must go on. Let there be what must be. Even then it is worth dying for that faith, it is worth drawing the ultimate defeat on oneself... for there is nothing of more value on earth. Robespierre: [looks at him fascinated]. Worth dying... for a lie! A lie the highest value on earth!!... [His legs give way under him. He sits at the edge of his bed] Oh, you have finished me, you know.

Saint-Just is proposing the Nietzschean solution to nihilism: the necessity of lies, the need to create new values in the face of a world inherently devoid of meaning. Robespierre rejects this philosophy as conceding too much ground to nihilism. Unfortunately, the nature of faith is that it has no real answer to doubt. Robespierre cannot prove his "truth," so once doubt has been unleashed and allowed to infect the masses (through the betrayal of a leader), it is already too late. Ingadahl does a good job analyzing the theme of doubt and connecting it to Przybyszewska's favorite book, Sous le Soleil de Satan. But I think Ingdahl misses how that faith distinguishes the Robespierre dictatorship (as portrayed in Przybyszewska's plays since historically Robespierre was never a dictator!) from the nihilistic, regressive Danton or Bonapartist dictatorship. Ingdahl tends to reduce them to two sides of the same coin and attribute them to Przybyszewska's "ambivalence."

5.

Ingdahl writes:

There is a destructive core in Robespierre's 'divine' pretentions, and on the subtextual level his transformation into dictator is at the same time a transformation into the Antichrist. Now he will follow in the footsteps of [Dostoevsky's] the Grand Inquisitor and create a dictatorship that fulfulls humanity's three basic needs: to have an idol to worship, to be liberated from conscience, and to join together in an anthill. When after his meeting with Danton Robespierre brands him a traitor whose ideas are from Satan he is in fact describing the essence of his own future strategy.

Ingdahl says again, elsewhere:

. . . This revolutionary spirit is ambivalent: it is evil disguised as good, and its perfect incarnation is the Antichrist. It is this duality in both Robespierre's and Danton's portraits that accounts for diametrically opposed interpretations of Przybyszewska's play as both pro- and counterrevolutionary.

However to Przybyszewska, the difference between Robespierre and Danton is that Robespierre's dictatorship is born from necessity in service to a higher (noble) ideal whereas Danton's ambitions and Bonapartism is dictatorship in service of nothing beyond individual glory--selfishness sanctified by the dynamics of imperialist war and capitalism.

Przybyszewska, as quoted by Ingdahl, explains her ideas of dictatorship:

The genius takes absolute and permanent possession of the idea as an active medium for its realization. It is only in his brain that it finds a formulation . . . The idea born of the masses as an impression of absence then returns via the genius and teacher to the masses as consciousness of the goal.

Since Przybyszewska believes in “the idea,” she cannot see the two types of dictatorship (the one in necessary service of the idea the other in service of “Nature”) as being fundamentally equivalent. However, if one does not believe in that idea, then “dictatorship is dictatorship,” which is the reading that Ingdahl offers in order to trouble Przybyszewska’s attempt at portraying a heroic dictator. In doing so, Ingdahl makes a good case for the influence of some of Dostoevsky's writings, specifically characters such as Ivan Karamazov and Shigalev, who both start with premises of freedom and end in conclusions of slavery and dictatorship. However, I don't think Przybyszewska had the same angst about dictatorship in and of itself as Dostoevsky did.

In a letter, Przybyszewska elaborates her ideas about revolution and dictatorship:

. . . The basic evil in the mechanics of the revolution: the unavoidable necessity of centralizing the whole undertaking around individual leaders. Even worse: around a single leader -- for as long as there are many leaders they will have to fight one another. The thought, the will, the energy of a single human breain has to penetrate the entire society and decide its every movement. Robespierre’s dictatorship was a necessity for revolutionary France in the Year II; unfortunately the Brutuses of the Comité de Salut grew frightened at the sound of that word. -- I don’t know who said that democracy is the purest form of aristocratic government -- congratulating himself on inventing an extremely bold paradox. it’s not a paradox, but a sad and self-evident truth. Perhaps today the masses, having achieved consciousness, will no longer be shapeless and powerless raw material in the hands of the leader; nowadays a dictator will be subjected to tight control; mutual dependence between a dictator and the masses will be established, as Marat had insisted that it should be.

What Przybyszewska seems more troubled by is the alienation of the people from their leaders, due to lack of “consciousness,” which causes a breakdown in the revolutionary mechanism, and starts the feedback loop of greater and greater repressions--thus creating a true despotism and what I'll call "revolutionary regression."

6.

In conclusion, I cannot prove it, but I suspect--and it is only a suspicion--that Ingdahl’s biased understanding of history influenced her reading of Przybyszewska’s plays. I also think she may have misidentified the source of the plays’ “ambivalence.” Actually, I don’t think she is wrong about there being contradictions and ambivalences, but I think they are not quite what she thinks they are. In fact, it would be interesting to elaborate on them more from a perspective of German Idealism, Hegelianism, and Marxism (traces of all of which seem to have been absorbed and remixed in Przybyszewska’s idiosyncratic theories).

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello! In lieu of this blog becoming a bit more academic from now on, I feel the need to organize my posts in some way, so from this point onward please refer to this list, sepearting my posts thematically. I hope it will help you find what you need with greater ease.

Scene breakdowns:

Robespierre’s hypothetical suicide

Robespiere&Camille versus Robespierre&Antoine

“Camille, don’t be a bore”

Antoine has always loved Robespierre: evidence

Danton versus Robespierre

Fabre’s phrase about a jewel

“Everything allright?”

“I would like to dance”

Themes and motifs:

Creating characters on an axis:Antoine Saint-Just as a potential anti-hero of The Danton Case?

Ekphrasis

Gnostic inspirations

Przybyszewska and women

Religious references

Costumes in Thermidor tell a story of illness

Who is the main character od The Danton Case?

Multirealities in Stanisława Przybyszewska’s plays

Transnationalism

Theory of literature and critique:

Stanisława Przybyszewska literature masterpost (periodically updated)

A review of Kazimiera Ingdahl’s book

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#literary analysis#analiza literacka#academia#sprawa dantona#the danton case#thermidor#termidor

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antoine Saint-Just as a potential anti-hero of The Danton Case?

I would like to present (extremely briefly; it's more of an invitation to their thoughts rather than anything else) two approaches that touch on a creative technique used by Przybyszewska, which has been spotted by some of her scholars, albeit each in its own way. Ewa Graczyk maintains that Przybyszewska did not write a historical drama in any way, but rather described a completely different reality, an universum in which the same events happen, but which doesn't take place on Earth, with us in it. She describes, then, something which I call The French Revolution', taking after mathematics' nomenclature. Kazimiera Ingdahl, on the other hand, spots traces of gnostic and manichean ideologies in Przybyszewska's writing, which, as we all know, are based solidly on the contrast between Heaven and Hell, knowledge and numbness, soul and mind. I mention them here solely to point out there is a dualism in her works, it is important and easily recognizable.

I have nowhere near the amount of erudition these scholars do, so I will constrict myself to some more visible matters. In my previous post about Antoine, I've made a remark that stuck with me for far longer than I had expected, and so I decided to elaborate on it.

The passage I'm talking about is this: because it could potentially reveal Saint-Just as another Danton-like minded individual, looking for power for himself through sacrifices of others. I want to explore whether Przybyszewska really did construct both of them alike?

To me it appears very probable, as crazy as it sounds. First of all, ALL of the personages are created in some reference to Robespierre. He is the only singular, original mind amongst them all, not to mentoin an axis around which other revolve, and so all of them, whether we like it or not, are somewhat similar to each other. Second of all, she clearly went in the direction of mirroring certain scenes, ideas, expressions (which I personally love to track down and compare them later), and it's exactly the same when talking about certain individuals. The two pairs (Robespierre – Saint-Just and Danton – Desmoulins) come to mind right away. They are constructed as parallels at least in some aspects and at least to some extent.

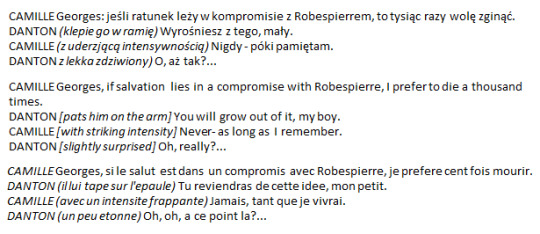

Wouldn't that, however, put Saint-Just and Desmoulins on the same/similar level, aren't they the ones who creat a parallel pair? Well, yes and no. I think they are a unit when it comes to personal matters, for rather obvious reasons. But I also think they are both put in similar situations, and yet their thinking is polar opposite of each other. They are both allowed to Robespierre's most personal sphere, and yet their reactions are completely different, which is one among the reasons as to why one of them meets a sad end by all accounts, and the other can die somewhat happy (as I will always mantain: if Przybyszewska managed to finish Thermidor, I am one hundred percent sure she would depict Antoine as one dying boldly and proudly, if only beause he died for a great cause and alongside Robespierre). On the other hand, spiritually and mentally, Camille resembles Maxime way, way more than Danton. They are both... maybe not exactly soft, but emotional. The main difference between them is Maxime is able to rein his feelings in when necessary (again, not always, not completely; vide his late night visit at Desmoulins', vide his attempt and saving him from the Luxembourg Palace), but as far as differences go, this one is actually minor. They are put in different positions, but their reactions are similar.

I would also wager to say Saint-Just and Robespierre don't have that much in common with each other in the plays, leaving out their political stances and their relationship. They are very different in terms of character traits: Maxime is more forgiving, calmer, quieter in all aspects. Antoine is more of a quicksilver, and also is regarded more as a tool in Maxime's hands, which I mean in the best way possible. While he has his own opinions, sometimes quite different to that of Robespierre's, he only entertains them in Maxime's presence, so that no one can put a splinter between them and turn them against each other. When they are turned against each other (during their quarrels, yes, but also during Thermidor, which is a beautiful study of such a case), he defers to Maximilien humbly and holds no grudges against him. This is pretty much the only soft side he ever presents to the audience, for when facing any other characters, he is sarcastic if not downright hostile, the only exception I can think of being Eleonore. He's not gentle, not even with Robespierre whom he respects so much. (I cannot get over how badly Wajda interpreted this in his movie, where in his very first scene Antoine brings Maxime an apple-tree branch in full blossom; while a sweet gesture, it made little sense, for the director not only didn't establish their special bond in any way, cutting their very important scene in Act II and a lot of their exchange of words in Act V out, but completely ignored the fact that in the play they did talk about trees blossming, but it was Maxime who pointed this out to Antoine. Honestly, it would make much more sense if in the movie he was the one giving Antoine flowers; altough I don't trust it would be executed well, so perhaps the best scenario would be to drop it altogether.)

This leaves Antoine and Danton as the unlikely pair. Here I wouldn't necessarily say they are put in different positions (following my train of comparison), because – depending on if you believe the confrontation between Danton and Robespierre to be honest or not – there is enough evidence in the play to mantain both of them want to establish power over nation through Robespierre. Danton is the villain of the play, but he isn't blind, he too wants to use Maximilien as a face of the dictature, as a tool to obtain more "normal" power for himself (normal power here would equal to money, respect, high office; the "abnormal" power is what Robespierre sort-of-dreams-of, an influence over people to direct them into doing what is necessary for the good of the whole of the nation, or better yet, the world). And Antoine wants more or less the same thing, the exception being he doesn't care at all for personal gains. He doesn't necessarily believe in Robespierre's visions of the future, one could even argue he doesn't understand them (this is clearly shown in Thermidor, where he reacts with a headache once Robespierre unfolds his plan in front of him: Stop it, Maxime. I can't keep up with you anymore.); he does, however, see the neccesity of establishing the dictature or some other extraordinary mean to obtain the total power over the state. Both he and Danton are blessed with a far-fetching political vision, the only thing differentiating them from Robespierre is that he's a much more brilliant chess player than any of them, when they can see few moves forward, he's already seen all the possible outcomes of the match. And all of these outcomes are bad, for Maxime is characterised as a pessimist, while Antoine and Danton are, generally speaking, optimistically inclined. Youthful foolishness indeed, except Antoine is not foolish! He's just optimistic. In Danton, the optimism takes a form of boldness and bravado, in Saint-Just it manifests as an unwavering faith in the one he considers to be so much more superior to himself, and also a certain amount of contempt for the ones he considers to be inferior. This is another trait he shares with Danton, and we have to admit, Przybyszewska did a really good job at presenting the same trait in them both in such different ways, that we like one, hate the other.

There is also the matter of how they treat Camille and what they think of him. Here, both are jealous, I think. Jealous of the special place Camille has in Robespierre's heart, scornful of his abilities as a politician and a journalist, disinclined to him as a person. Danton cares for him as far as his utility in being a leverage on Robespierre goes, but I don't think he hoards any warm feelings for him personally, and I don't say it only because he was willing to sacrifice Camille purely out of spite. A much better example to show what I mean is that Danton seems to have a much better functioning, more honest and professional relationship with Delacroix than with Camille, whom he keeps in the dark about absolutely everything from start to finish. I don't know if it was meant to be a symbol or not, but in their very last scene in the jail cell, Camille has to beg Danton not to snuff out the candle, which Danton does, albeit very reluctantly. In turn, Saint-Just talks about Camille in language dripping with contempt and jealousy of purely personal kind, offending him left and right, right to Robespierre's face – not to hurt Maxime, but to "open his eyes", so to speak. In one particularly harsh sentence he compares Camille to a dog, a child and a prostitue all in one breath. He not only doesn't regard him as an opponent, but barely recognizes him as a human being worth respect, in which he is sadly very similar to Danton.

Weirdly enough, they both regard Maximilien as human, which I think is interesting to notice. It would be really easy to write them in such a style that leaves way for them to see Robespierre as something more, something almost extraterrestrial, somebody who posseses abilites greater than normal humans do. And yet:

The first image is from The Last Nights of Ventose, my own translation, and it's directly from Antoine's compassionate speech. I didn't include Robespierre's response, because he just deflected, but deflection does mean he doesn't fully agree, so it's yet another similarity.

One more thing that comes to mind in a comparison like this is that Danton threatens Robespierre with the ultimate power. He doesn't think that Maxime will be able to live with it, with himself, if he ever decides to go this one step futher and become a dictator. Is this is because he wouldn't be able to live with himself, or does he truly underestimate Maxime, or he simply wants to make sure Maxime would not go in this direction precisley because he knows he would then be ustoppable? How very telling then, that in Antoine's mouth the very same thing is not a threat, but a promise! This ultimate power is born out of necessity, and it's a grace for the whole nation, because no other person could bear the weight of this "crown", but Maxime.

The main difference between Saint-Just and Danton, I think, is something which we have to believe, it's not written clearly anywhere, and this is also the thing I briefly touched uppon in the aforementioned post: we have to believe that Antoine has pure intentions, because we sure know Danton does not. These were the embers fueling the suspiscion in Maxime when he couldn't understand why Antoine would possibly push for the dictature so much – is his heart pure? This sounds overly dramatic, perhaps, but I think this dramaticism aligns perfectly with Maxime's overall characterisation. I think all readers believe in his good intentions, and the parallels constructing the characters help immensely in this judgement, for if Danton is rotten to the core, Antoine is as steady and pure as a marble column. Robespierre even calls one a pig, while the other deserves to be named an Apostle of liberty.

There is, however, another similarity between them, too. Both Antoine and Danton are willing to be dishonest in order to achieve their goals. This is this one thing that's hard for Robespierre to swallow, for he – like Camille – values honesty really highly and if he could, he'd always act honestly. Saint-Just, not to mention Danton, has no such scrupules. He sees the greater necessity as something erasing all other circumstances, and for this greater picture he is willing to sacrifice some of his integrity as a human being. With Danton, the situation is even less complex, for I don't believe he would be sacrificing his integrity in any way – this dishonesty lays at his very core and comes natural to him.

The arguments Saint-Just presents, and which differs from Robespierre's point of view, are also different from that of Danton's. Danton's vision of the present is filled with contempt for the people, for the masses who are less brilliant than him and few others are. It is worth noting that Przybyszewska really did think like this, this is something she believed in and while reading Danton's speeches in Act II Scene 3, what we actually hear is her own train of thoughts. The only difference is that she didn't disdain the people they way he did. She thought that being a mass, an unnamed pulp of flesh is not a bad thing (it was perhaps unfortunate, and I am sure thinking she was a genius like Robespierre helped her in maintainign this view). Base material is a nourishment for those who will lead these masses. We – the lesser people – are absolutely necessary for them – the greater ones – so that they can lead us out of the night and into the new epoch of enlightement, and there is nothing humiliating in being this nourishment/tool/base. Danton understood it only partially, for he wasn't ready for the greatest sacrifice of all: to be a genius, one has to get rid of everything personal, all needs and desires must be kept aside, and never again spoken of. Robespierre understood it, and I think Antoine did too. I think the best evidence for it is that he said, that he doesn't consider himself to be Robespierre's equal. Recently I hoped to prove it was a silent declaration of love; now I want to point out it is one because it showed Robespierre that Antoine understood this great sacrifice one has to make in order to be a leader, and in his own way, he has already done this. He has brushed aside personal vain and glory, his amour-propre, he degraded himself in order to magnify Maxime's importance. Danton may say: It's you whom I adore, but it is Antoine who shows it through his actions as well as his words.

#do you think they are constructed as parallels or am i delirious?#sprawa dantona#the danton case#L'Affaire Danton#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#Maximilien Robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#antoine saint just#Antoni saint just#georges danton#jerzy danton#frev#french revolution#literary analysis

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I cannot claim to know about this play more than some others (Ewa Graczyk, Jagoda Hernik-Spalińska, Kazimiera Ingdahl and Maria Janion, in alphabetical order, are the official Horsewomen of the Apocalypse in this topic), with a lot to bring to the table, and so I will sometimes discuss parts of it which are - at the very least at the first glance - absolutely and doubtlessly simple; but by discussing them I hope to be able to bring into the discussion some new material, new evidence, perhaps - for the contrary of the popular belief.

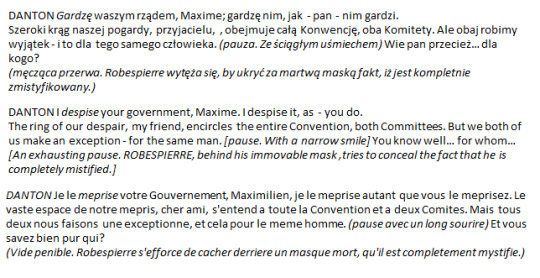

I remember when I first read the scene between Danton and Robespierre, I was completely mystified, just as Maxime. To somebody who at that point knew nothing about the historical events, the exchange between them was very logical (and everyone knows how hard it is to obtain, especially in a piece of media where the author blatantly favours one of the characters over another). I am very glad then, to be able to say that while Przybyszewska did everything she could to humiliate and belittle Danton in the more visual aspects of the scene - his gestures, movements, actions, mimicry, even the sound of his voice etc. - she didn't bother making him out to be a complete clown. His arguments are populistic, but that's not necessarily a bad thing when you're n politician aspiring to be even more than that. Perhaps she thought that painting him out to be a weakling would somehow diminish Robespierre's awesomeness, which is a valid concern. For Robepsierre has little left to do in this scene - it is made out to ba a confrontation between them, of sorts, but is it one, really? I don't think so, not for the large part of it. Robespierre comes in, dishes out few sarcastic lines, looks at Danton with disgust and contempt and then crushes him in a yet another sarcastic line and then leaves. There isn't that much he can do not only to participate in the exchange, but to be visually and audially appealing to the audience as a character in a play. And even though we all know staging The Danton Case is a secondary affair, the main thing you can do with it is to read it and ponder over it, when you do stage it, a lot of responsibility rests on the actors recreating the part. Which is why choosing a good actor can, potentially, make all the difference, sometimes going as far as completely changing the way you view the very same scene you read earlier.

I have always assumed by "the same man" they meant Robespierre. It makes some sense in the light of the conversation, altough I have to admit it makes little sense in the light of Robespierre's reaction. The question thus presented to us is: do we go by what is written, do we percieve a play as a piece of fiction in a real world, OR do we immerse ourselves in the fictional world, suspend our disbelief and for a moment treat it as an alternate reality of sorts?

Polish director Jan Klata has managed to put on stage a compelling retelling of The Danton Case and I would like to present to you a scene from his version, which we're lucky enough to have on YT, with translation courtesy of @that-one-revolutionary. I've seen the play in its entirety: some metaphors were heavy-handed to say the least, some aspects I wish he'd done differently, but all in all, when choosing the main protagonist, the director casted in the role a truly splendid actor (please note that Marcin Czarnik was young. Young! It made all of the difference and it's worth watching if only for that), who brought home some of the points of character of Robespierre's which could have easily been brushed aside in order to highlight some other aspects of the conversation (the most famous example of this would be the very same scene from Wajda's movie, where the appealing and in all aspects imposing Gerard Depardieu dominantes the scene, thus presentign it in a very different ligt). While it can be read as a political statement, or a match of two great personalities, or a display of cunning on either part, Klata (or Czarnik; it's hard for me to say what the director tried to do with it, a lot of Robespierre's quirks, mimicry, gestures etc. seemed to come directly from the actor, which I can only say because I've seen him in other things and that's sort of his style of acting; all in all, I'll try to treat this not as a discussion over this particular staging, because for that I lack needed data, but it's unavoidable in the long run at least at some points, so please bear that in mind) treats the conversation itself as a minor thing in comparision to what is going on in Maxime's mind at the moment. Just look at this: there is no significance brought into their meeting, no change of the scenery, nothing indicates this meeting is special in any way. The logical conclusion is, then: it's not special. Both Danton and Robespierre seem to treat this as a step which cannot be avoided, but which bears no great weight either. The only reason they agreed to make this step altogether is - for "the same man". For Camille.

I do think Przybyszewska's intention was actually to disguise Maxime under this vague title. If this is a play about love - as I will always state it is - she wanted to underline the fact some people will be hatefully loved by those who are beneath them, who have nothing whatsoever in common with the object of their affection simply because the loved one is so great, so genius, so shining and bright it is impossible not to love them. I think this is the relationship between Danton and Robespierre (that is, on Danton's part) up until this point in the play. Danton idolizes Robespierre against his will (against both of their wills, really), because Robespierre is truly made out to be a demi-god at the very least. If you could team up with a hero like this, you should. So Danton goes through a humiliating process of trying to reconcile with Maxime, because humiliation, if everything paid off in the end, would be worth it. That Robespierre doesn't reciprocate the affection is simply a further proof that he is above Danton in every way.

Klata-Czarnik duo seems to have gone into another, subtler direction though. The man that both politicians make an exception for seems to be Camille, moreso because Robespierre loves him than because Danton has any special feelings for him. What is his relationship with Camille, anyway? They are cordial enough, but always a bit on the edge, and we know that Danton doesn't know everything that Camille thinks and feels in regards to Robespierre, mostly because he doesn't care that much, but also because he is characterised as a brute, and this simply goes above his head, it's too subtle, too delicate of a feeling for him to know it. It is also clear he knows Camille pretty well, but he doesn't know his soul, so to say. Therefore, he cannot actually love him, not to the point to make him the one and only excpetion from his otherwise coldly and precisley calculated plans.

Is there, however, a scenario in which Camille could be Danton's exception? Yes, when it becomes more about Robepierre than about Camille. When Camille is sort of offered as a mean to lure Robepierre in. Danton could make this exception only if it meant getting what he wanted (which is later mirrored by his blatant admission that the only reason he lets Camille take the fall with him is to deny Robespierre any joy in life after this point).

Robespierre, however, doesn't see it this way. He actually makes the exception for Camille and I think Danton's words – whatever he means by them, whichever interpretation we think is correct – put him on alert, for the fear of having his secret discovered. In the video linked above it is even more than that – once Robespierre hears Danton indirectly name "the same man", he gets aggressively defensive. For him to have someone like Danton talk almost openly about what he treats as his personal secret (a secret that Danton, being in great familiarity with Camille, could potentially know for certain) is equal with defiling it. I have violated your secret. Do you know what he says in the original? I have raped your secret. It really brings into the focus how much “the secret” needs to be protected, and how much it will hurt Maxime once it’s uncovered and destroyed.This is what he fears pretty much for the entirety of the conversation, his suspiscion somewhat confirmed when Danton says: No catchphrases, Robespierre. I know you.

As I mentioned earlier, the shift in my reading of the scene was prompted by the video. It is worth observing what exactly does Robespierre do when mentioing Camille by surname – he gets visibly more upset, he ponders for a split second for the best way to talk about him. His choice of words is interesting as well:

Both translations here are poor and I quite like what that-one-revolutionary did with it. "Katarynka" is a music-box, so "an instrument" fits much better (not to mention the obvious English connection to the phrase "play like a fiddle", which is adequate here). A parrots is after all a living being, something with a will of its own, if steered by more powerful handlers. But admitting that Camille, from his own free will decided to go against Maxime and everything that Maxime believes in is much harder for Robespierre than calling him an inanimate object, which can be unwittingly used by people with their own agenda. That leaves Camille almost blameless, perhaps careless and foolish, but not responsible fo anything that has transpired.Calling him names serves another purpose as well, which is to steer away the suspiscion that Robespierre protects Camille becuase he cares about him in a special way. He knows there are Danton's accomplices turning ears by the door, so he doesn't want to give himself away with his care and concern.

Ultimately, what do you believe, whom do you think they were referring to I think says a lot about what you think about Maxime's state of mind at the time. Danton's too, though, it can be used as a litmus test whater or not you believe he was honest in idolising Robespierre and offering him his adoration and obedience. In some stagings it will be presented as true, in some as a lie, and that's the beauty of adapting a piece of literature, there are so many options, all blooming from the same roots.

#sprawa dantona#the danton case#L'Affaire Danton#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#maximilien robespierre#maksymilian robespierre#kamil desmoulins#camille desmoulins#georges danton#jerzy danton

14 notes

·

View notes