#Probably the closest interpretation to Acd

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Watson Looking at Holmes like he is the whole world tm moodboard

Images: Watson looking at Holmes smoking, from afar

Watson looking at Holmes smoking, from up close

Watson watching Holmes think

(A three pipe problem)

Watson tending to Holmes' minor head injuries

Text: say that again? I'm sorry. I got distracted by your little manerisms, how you pronounce certain words, and the way your eyes light up when you talk about something you're passionate about, and started my day dreaming about spending my life making you laugh, and feel loved and cherished

They are beautiful, and gay, and I will hear nothing against on it

#gay#acd johnlock#johnlock#granada holmes#granada sherlock#sherlock holmes characters#Sherlock holmes#david burke#victorian husbands#jeremy brett#I love edward hardwicke too but he isn't in this#Though I think he's got those dewey 'i love holmes' eyes DOWN too#Sherlock is gay#And possibly asexual#And john watson is clearly bi#acd holmes#Probably the closest interpretation to Acd#I mean the outfits are pulled straight from Paget

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiiii Tiger can I ask for you to tell me more about your ideas and thoughts surrounding Kitty? I love how you write Kitty and she's so important to me. I'd love to know. Victorian or modernized interpretation or both?? (Also you're one of my favorite writers so hii) -B

Hi! You can!

I love Kitty so much and I think she needs to be used far more often in things.

For the Victorian character at least there's usually this tendency to assume Kitty is this 'fallen woman' who was basically a 'respectable' kind of woman until Gruner seduced and discarded her which is not how I tend to see her. I think in any universe Kitty is probably going to be a sex worker of some kind anyway, I mean before Gruner turns up in her life (in the modern day that's probably going to be more in the videos and online stuff line of sex work though not so much face to face physical stuff). I think also, she's not ashamed of that. And she likes sex and she likes dominating people sexually too so it would seem to her that if she can make money (and quite a lot of money probably) out of these things that she does enjoy then she'd be a fool not to do that.

I think she is young but has kind of had to grow up very quickly, so she's been very mature for her age for a long time, maybe because her family was very poor, maybe because they disowned her, and she is very self-confident, very outspoken, very tough, but she's still kind and caring; however hard her life has been that kindness and compassion has not been burnt out of her.

I think an element of Kitty's characterisation in the Granada episode where it was revealed that Gruner had injured and disfigured her has some merit - it may not be exactly like for like, what she does to him, but I think he probably did do something to her first that left her physically scarred, I really don't think Gruner is just this upper class guy who likes 'ruining pure women' by seducing them, I think he is basically the closest thing in the canon (when ACD couldn't actually be too explicit about it) to a serial killer (and I do believe completely ACD did base him on a real multiple murderer and possible serial killer), and that she disfigures him rather than trying to outright kill him does suggest that he disfigured her in some way first.

I do always love that Kitty helps bring Gruner down and helps stop him from harming another young woman even though that woman is very unpleasant, but she also has her own revenge on him with the acid. For her to commit an act like that which is so horrendous, I think he's done far more to her than just seduce her, it was something much worse than that. But she is a survivor not just his victim.

Kitty does get the most interaction with Moran in my stories and I think they are very good friends and practically consider each other family. Their relationship has been a sexual one sometimes but I think they're not romantically compatible - I think Kitty is aromantic and she doesn't want a committed partner, I think she doesn't even like sleeping with someone else, she likes sex a lot but after that she wants her own space and to not end up being tied to someone in a way that would feel stifling to her. (I also love the idea that she's one of those aromantics who gives great advice about dating and romantic relationships.)

I like the idea too that even though she's younger than he is, she acts almost like Moran's older sister sometimes and in some ways is a lot more 'street smart' than Moran is, because Moran has come from a background that was all private school, university, army, all these institutions where he was quite sheltered from 'ordinary' life, even though he has been through immense hardship himself and has rebelled against all of that a lot, he does have a sort of naïve quality to him and probably in the modern day even more than the Victorian era I think he does struggle with fitting in ordinary life. But Kitty didn't have that same privileged background and she knows a lot more about ordinary life and how to survive it and I do see her as finding Moran by accident and being the only person who takes any notice of him and realising how much distress he's in (in my story he's literally having a panic attack when she first sees him) and she helps him and looks after him and he adores her from that moment on really and they become very protective of each other.

I don't want her to be just like a 'tart with a heart' character where her decency is there to be kind of ironic because she's an """immoral""" woman. It's clear from the canon though, Kitty is not someone who is considered a 'respectable lady', but even there she is treated with respect by the major characters including Holmes. And also she has been through a lot but her vindictiveness towards Gruner is very much justified (even Watson, who seems especially horrified by what she does to Gruner, seems to think she was justified in doing it) and she is still a decent person in spite of whatever Gruner did to her, her actions aren't really portrayed as just malicious, it is definitely implied that he did something terrible to push her that far.

I do like that in the canon Holmes interacts with her and seems to like her and support her even after she throws the acid on Gruner. I always love the idea of her interacting with Moriarty too though and him being very impressed by her and liking her when Moriarty is not really a man who is easy to impress and he doesn't like many people. In my story too she's definitely suspicious of Moriarty's motives and concerned about whether Moran is safe with him and I do see her wanting to check Moriarty out herself. I do think Kitty to some degree has to do the kind of thing that Holmes does, that Moriarty too does - she has to be able to read people and read the subtle signs and clues about them, because as a young woman and as a sex worker she can be very vulnerable at times and there may be moments when her safety could depend on her reading the most subtle of signs about someone. So with Moriarty, she probably does see through him faster than even Moran does, she sees that he's not just a maths professor he is something else, something realistically much worse, but I don't think she's actually ever afraid of him (Gruner I think would frighten her, though somehow or other she does end up too heavily involved with him later and of course comes to regret that).

Also I was joking before about giving Moran a Chihuahua but I have given Kitty a Chihuahua in my story, I think she is the type to have a small feisty dog like that (but that is well trained and well behaved).

(Thank you)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studying “A Study in Emerald”: Third Post

Part 4: The Performance

We begin Part 4 with some more general canon references—the detective being a master of disguise, for one, and doing investigations undercover without his companion, who watches as various characters process through their sitting room. The narrator worries about the detective’s health, just as Watson does on many occasions.

And then they go to the theater, and everything (for us) changes.

I remember, when I read “A Study in Emerald” for the first time, being struck by the use of the word “languid” to describe the leading man in the theater company. “Languid” is used to describe Sherlock Holmes in multiple canon stories, including “A Scandal in Bohemia,” “The Red-Headed League,” “The Adventure of the Norwood Builder,” and “The Problem of Thor Bridge,” among others. It’s a word, not an object, but I associate it with Holmes just as much as the Persian slipper or the knife in the mantelpiece. So seeing this word attached to some random new character, who is described as both languid and tall, immediately brought to mind canon Holmes’s appearance and gave me pause—although I can’t say everything became clear to me in that moment. It would seem that everyone is still in their same bodies as in canon and retains their physical characteristics, despite the world they live in being a warped version of the original.

The final play in the show tells us a bit more about the backstory for this world, while also solidifying that uneasy feeling for the reader that started to percolate in the previous chapter. It’s one thing for monstrous creatures to exist in a story, posing a threat that our protagonist recognizes, as was the case when our narrator described the horrors of Afghanistan way back at the beginning of the story. But here, with the entire audience cheering for beings who have names like “the Czar Unanswerable” and regarding a blood-red moon as “comforting,” it’s as if the populace has been brainwashed. The order of things in this world is disturbingly off-kilter.

Now that we’re fully on edge, Gaiman tips his hand as the detective and the narrator go backstage and meet Sherry Vernet. A responsible Sherlock Holmes reader will recognize Vernet as the name of the famous artist whose sister was Holmes’s grandmother. It is therefore a perfect alias for Holmes—probably anyone writing a Holmes adaptation/pastiche would be likely to use the name if Holmes had need of an alias—and it should set off the loudest alarm bells yet for the reader. (I myself was saying “Wait a minute!” at this point.) A few paragraphs down, the detective gives the narrator the alias of “Mister Sebastian”—the first name, of course, of Colonel Moran, Professor Moriarty’s closest associate.

For the more astute of us, the game might be up at this point and the true identities of our protagonists clear. At the very least, however, readers know that everything is not as straightforward as it originally seemed. With these game-changing details now in play, the story has a moment that I think of as resetting all of the pieces. It does this by returning to the Study in Scarlet scene that “Emerald” began with, the meeting of prospective roommates. In the canon story, Holmes mentions his smoking habits to check if Watson would be amenable:

“You don’t mind the smell of strong tobacco, I hope?”

“I always smoke ‘ship’s’ myself,” I answered.

In “Emerald,” the wording is different, but the exchange is similar enough to echo the original:

“I smoke a strong black shag,” said the actor, “but if you have no objection—”

“None!” said my friend, heartily. “Why, I smoke a strong shag myself...”

Holmes’s words, for a brief moment, transfer to their proper speaker—the real Holmes. We were lulled into assuming we knew who the protagonists of this story were in the laboratory scene and it is this same scene that we hearken back to now as the true identities come into focus.

Incidentally, this exchange also doubles as a reference to another story in the canon—the detective gets a suspect to share their tobacco as part of a stratagem to reveal their guilt in “The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez.”

When Holmes appears, Watson should not be far behind, so we get the “Emerald” detective’s identification of “The Limping Doctor” as the second man responsible for the death of the prince. The identity indications in this story are getting more and more blatant—Watson is the only one in Holmes canon that fits the bill for this particular description, with his leg wound established in The Sign of the Four.

Regarding the Limping Doctor, the “Emerald” detective remarks:

“I hate to say this, but it is my experience that when a Doctor goes to the bad, he is a fouler and darker creature than the worst cut-throat.”

This is a reference to an original line of Holmes’s, found in “The Adventure of the Speckled Band”: “When a doctor does go wrong he is the first of criminals.” That particular story is one of my favorites due to the way ACD slowly builds up the dread as Holmes and Watson get closer to solving the case. The doctor/villain in “The Speckled Band” is one of the more contemptible in the canon, right up there with Charles Augustus Milverton and those men from “The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter,” so it’s ironic to see Holmes’s assessment of the man now applied to our dear Dr. Watson.

On rereading the ending of Part 4 for this analysis, it struck me that this last scene is a very subtle homage to “A Scandal in Bohemia.” If you’ll permit a bit of a tangent as I explain: in the story, Holmes and Watson have just come back from Holmes’s successful stratagem to get Irene Adler to reveal where her secret photograph is hidden. Holmes plans to retrieve said photograph in the morning and believes everything is well in hand.

We had reached Baker-street, and had stopped at the door. He was searching his pockets for the key, when someone passing said:--

“Good-night, Mister Sherlock Holmes.”

There were several people on the pavement at the time, but the greeting appeared to come from a slim youth in an ulster who had hurried by.

“I’ve heard that voice before,” said Holmes, staring down the dimly lit street. “Now, I wonder who the deuce that could have been.”

The next day, of course, Holmes discovers that Adler was onto him and has escaped with the photograph, and that she had followed him home and was the one who wished him good night the evening before.

At the end of Part 4 of “Emerald,” the same beats are there. The detective and his narrator friend are in the midst of unlocking the door to their Baker Street rooms, there’s something just a bit odd (the cabbie not picking up a waiting passenger), and the detective is mildly puzzled but not overly concerned. It’s not an overt reference, but the circumstances are just similar enough for the connection to be made.

Those of us who know how “A Scandal in Bohemia” turns out will understand that in having a nod to this particular scene, Gaiman is indicating that the tables are about to be turned on the detective, and the case will not be quite as successful as he thinks.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

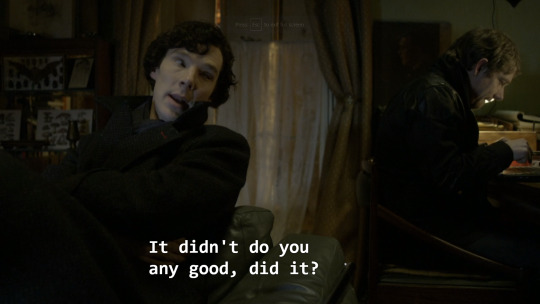

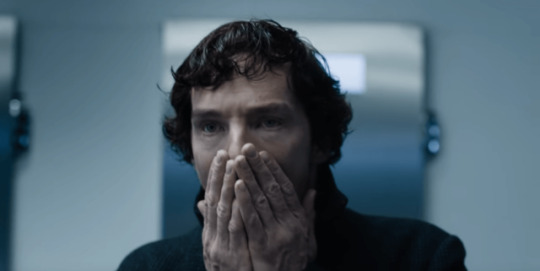

The Great Game + Five-Act Structure

me and @messedupsockindex did a TGG rewatch (i think we’re gonna do the whole show hell yeah hell yeah) and I did some liveblogging that turned into several metas on things i think are important in this episode, with the five-act structure being a Theme (though i went off on a real tangent RE: solar systems/framing and metaphors too). Read on if you dare.

First of all I learned that this was the first episode of the show that was filmed? I find that very interesting, I don’t know much about how to shoot a tv series, BUT if this was the first one that was ready to shoot, i wonder if that means it was the first one finished, and if it was the first one finished, is it because it’s The One that lays out the five-act structure of the whole show?

link to @fellshish ‘s most brilliant meta here

another small spot of evidence for this “TGG is the layout for the whole show” theory is that lots of little shots in this episode are also in the title sequence (could be a coincidence if they did indeed film this episode first, but also maybe not)

Throughout this episode, we are shown an ongoing conversation between Sherlock and John concerning Sherlock’s lack of basic knowledge about our solar system. It effectively frames the episode - one of the opening scenes being their “domestic” (fight), and the penultimate scene (before the pool scene) being the infamous “I won’t be in for tea” / “I’ll get milk and beans” tragedy. I want to liken this episode-long conversation to a technique I saw in a different show.

In this show (Masters of Sex starring the brilliant Michael Sheen and the formidable Lizzy Caplan), a man and a woman are having an affair with each other, but justifying it by saying they are simply “working” and that they’re not emotionally attached to each other (they’re sex researchers, so they “collect data” whenever they meet...it’s dumb.) Anyway, there’s a beautiful episode entitled “Fight” during which they are watching a boxing match in their hotel room while engaging in elaborate sexual roleplay with each other. While the boxing match plays in the background, they riff on what their lives would be like together if they really were the husband and wife duo that they pretend to be for the hotel staff. It’s intricate, and loaded, because you never know when they are acting within the roleplay, or talking honestly to each other about their feelings and pasts. They metaphorically duck and weave like boxers around their feelings and around each other. Their conversation often talks literally about boxing, too - The Fight is a tool through which the writers explore the characters’ bond for the viewer.

I see Moftiss using this same technique when I hear Sherlock and John going back and forth THROUGHOUT THE EPISODE about knowledge of the solar system. The first time they discuss it, you can feel John trying to understand why Sherlock comprehends things the way he does - why can something as basic as the solar system (or attraction) be allowed to slip through the cracks of his otherwise daunting intellect? And you can also feel Sherlock’s frustration with the way John perceives him - why should it MATTER if he doesn’t know the exact details of how the solar system (attraction) works - shouldn’t the fact that he knows it exists be enough, and if or when when he needs to, he can figure it out from there? They continue to explore the concept with each other as the episode goes on.

Here, John has accepted that Sherlock doesn’t (or thinks he doesn’t) care about the mechanics of something as basic as the solar system (attraction). So he asks, why comment on it? Sherlock says even if he doesn’t understand it, he still appreciates it. Telling.

In the final instance of this conversation, the penultimate scene of the episode, John tells Sherlock that maybe a little knowledge of the solar system might have come in handy after all. But Sherlock also has a point:

John’s knowledge of something so basic as attraction has been useless to him thus far.

If we’re gonna accept food = sex, I found it funny that John was “starving” and he found a head in the fridge. John, there’s head for dinner, if you want it! Even funnier that Sherlock’s response to “I’m starving” was that he was researching saliva. (I don’t love the food=sex thing, I just don’t think it’s intentional, but I do feel like it’s a valid interpretation here that Sherlock is subtextually begging John to let him suck it)

I’m too tired to figure out what Mycroft’s dental appointment could possibly mean but both of us were like??? My half-baked theory right now (borrowing from M theory) is that the “dental appointment” was actually Mycroft getting the shit kicked out of him by Moriarty/Mary/whoever the mastermind is, so that Mycroft would plant the missile plan crime for Sherlock?

okay so I never really realized this but Sherlock knows Jim is gay bc he uses hair product and then season 4 John has hella hair product....huh

Sherlock’s security outfit is queer coded but suddenly I can’t find any evidence of this I just...have it somewhere in my psyche that a police/security costume outfit like that was claimed by queer people and I can’t remember why?

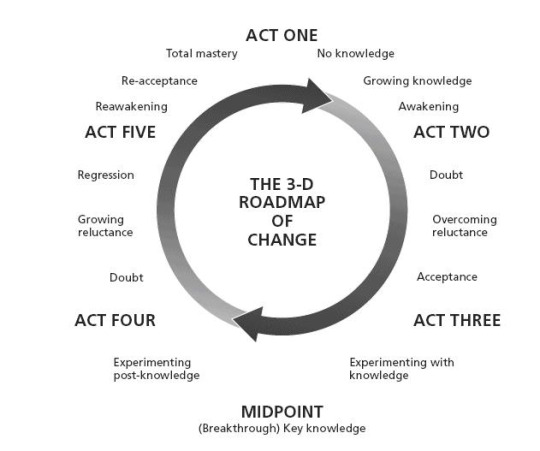

For hostage number 3, the old woman, Moriarty (or whoever is on the other end of the computer) calls her “a funny one.” @messedupsockindex told me while we were watching about the midpoint of the five-act structure being the breakthrough, the point of no return, the point at which key knowledge is gained (from John Yorke’s Into The Woods, also brilliantly discussed here). I can’t help but think of this seemingly offhand line as a tiny clue to the importance of series 3 of BBC Sherlock. (In case you didn’t know, the midpoint of the whole show, if there are indeed going to be fifteen episodes, is...you guessed it...the best man speech).

The last Greenwich pip case that is solved, a case in which we have a hostage on the other end of a phone, is the fake painting. The solution to this case is “the Van Buren supernova” aka part of outer space, seen from our solar system. As I’ve argued above, the solar system is a metaphor/framing device used in this episode to subtextually discuss the engine of this entire show - Sherlock and John’s relationship. How very telling that Sherlock, even Sherlock, very nearly doesn’t get to this solution. But, when he does...

(me reading about the five act structure and realizing series four is fake)

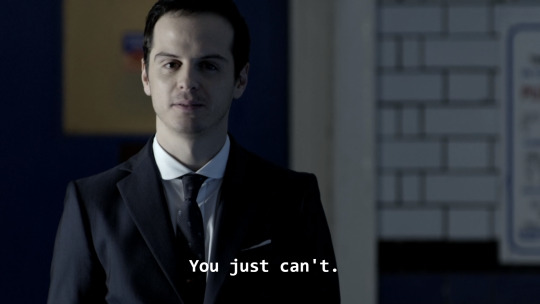

Moriarty’s last few lines - I find this whole scene to be absolutely vital to understanding the point of the whole show, but especially the last bit.

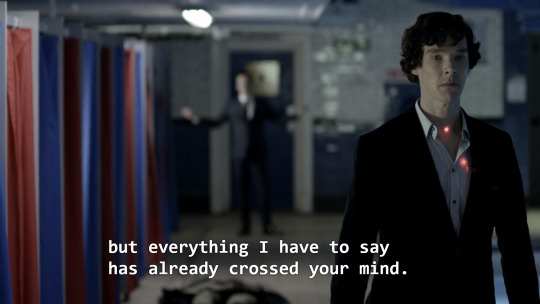

There is probably already someone who has explained/noticed this but...the exchange that Moriarty is responding to, that happened before he re-entered the room, was Sherlock and John getting the closest they ever get in the WHOLE show to discussing the sexual tension/attraction between them (I think I’m again standing on the shoulders of the legendary M theory here). John has taken a huge leap in choosing to bring up what “people” might think about Sherlock ripping his clothes off in a darkened swimming pool. Sherlock responds jokingly but not dismissively, and the logical next step would be to discuss what they themselves think about it...until of course they are interrupted by this, by literally being held at gunpoint.

Moriarty’s lines here are apparently some pretty famous lines in ACD canon. I didn’t know the canon context, so it’s a little easier to just parse the lines in context of this scene. Moriarty wants to stop this discussion that Sherlock and John are about to have, and more broadly, whatever that conversation might lead to. He would try to convince them that they can’t be allowed to continue, but everything he has to say, all the convincing he could possibly do, has already crossed Sherlock’s mind (or both of their minds - it’s actually not specified who he’s talking to here). This is true because Sherlock and/or John are afraid to “continue” - discuss their feelings for each other - because of trauma and internalized homophobia. All the reasons that they shouldn’t “continue,” reasons that Moriarty could cite out loud, have already crossed their minds, probably more than once. I think this unspoken meaning makes so much more sense than taking Moriarty’s “you can’t be allowed to continue” to mean “you can’t be allowed to continue to solve crimes,” which is what it meant in ACD canon. And it’s a fantastic rework of an ACD canon line.

So... the end, I guess. I probably should have split this up into different posts...

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Advent of Johnlock

So, I saw someone refer to Jefferson Hope and Faith Smith in the same post and some ideas kinda clicked into place for me, about why it was always going to be the fifth series in which we get canon Johnlock. This is my first meta, I’m not sure on structuring it, but I think this is the most logical way. So here we go!

Content warning: I’m going to analyse religious metaphor in this meta. If you’re very strongly Christian, some of the things I say you may find offensive. I mean no offence to anyone’s religion and respect all views - I am merely describing metaphor as I see it.

As someone brought up in Church of England, for me every Christmas came with the anticipation built by the four week long season of Advent. Advent is a time of preparation for the day of celebration, to think back on out past selves and improve, to prepare our hearts for Jesus.

Now bear with me, because this going to seem a little crazy until I unpack it. But my point here is that the first 4 series’ of Sherlock are the 4 weeks of Advent. Series 5 will be Christmas.

“Advent is a season of expectation and preparation, as the Church prepares to celebrate the coming (adventus) of Christ in his incarnation”

https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-and-worship/worship-texts-and-resources/common-worship/churchs-year/times-and-seasons/advent

We already see religious metaphor in Sherlock - “Lazarus is go” is an example that springs to mind, and there’s the whole rising from the death situation. I could write loads about candles and light/dark symbolism too, but that’s a little much for now… We’re going to focus on the traditions of the Advent Wreath and the Four Last Things as our points of reference here. I’ve used a couple of sources, but there is a lot of different interpretations of the meanings of the 4 weeks of Advent and I’m basing this meta on the ones I grew up with, which doesn’t ally with all sources.

Just in case people aren’t familiar: an Advent Wreath is a set of 5 candles, one lit in each week of advent and the last on Christmas day, each symbolising a Christian value. As I mentioned before the order changes across the religion, but in the Church of England I grew up with Hope (Christ’s coming predicted by the prophets, our ancestors), Peace (the angels), Joy (the shepherds), Faith (the wise men), and Love (Jesus). The Four Last Things are themes for meditation during the season: Death, Judgement, Heaven and Hell.

Series 1, the first week of Advent: Hope, the Prophets, and the theme of death.

Immediately, Jeff Hope. Obvious!

But also, the themes of the series; John is hopeless, thinking about death. Sherlock gives him hope.

Of course, death is a constant theme through the show, but in particular this series, where they choose to die together with a glance.

And haven’t people seen Johnlock in ACD canon for decades? Centuries? Our forefathers of fandom saw this coming, and had hope for canon Johnlock. The first Sherlockians are our prophets and ancestors.

Series 2, the second week of Advent: Peace, the angels, and the theme of judgement.

Here, judgement is the obvious one. The Reichenbach fall is full of not only a literal trial where Moriarty is judged, but focusses on the media and public opinion’s judgement of Sherlock and John as people. Is Sherlock a good person? We as an audience are instructed to question him, by Moriarty, who sits in a throne of judgement. Literally.

Peace is more tricky. At a surface glance of the show, where does peace come into it? But when we look at inner peace maybe; this series is in some ways the most domestic between John and Sherlock - they fight, yes, but look at the small scraps they have compared to the wars they fight in series 4. They find peace in eachother’s company.

Peace is also what the struggle is all for; look at Sherlock, sacrificing himself, his life, his work, for his friends. But the failure to grasp that peace is an unreachable concept - heavenly, impossible on earth - is no doubt his downfall… literally. His sacrificing himself does not give his friends the peace he desires for them. The only peace found in the series is during their domestic moments in Baker Street, AKA when they actually communicate.

Angels of course link to Sherlock’s death, he may be on the side of them but he’s not one of them. He’s mortal. He must be, to die and rise again. And again and again, in different interpretations of ACD canon. Sherlock is mortal but can’t stay dead. He has unfinished business in his stories. The end isn’t right yet. And cupid, the eros statue at the start of ASIP, shows us right from the start what the angels mean - Sherlock’s unfinished business is announcing his feelings for John.

There’s another thing and it’s probably a bit of a stretch. I’ve always wondered why the scene in THOB where Sherlock apologises to John takes place in a graveyard, distinctly an English country church graveyard. Weird choice, right? Maybe we’re going for religious metaphor? And then we get John as a conductor of light. Now, Sherlock is Jesus, he rises from the dead, and believes in a higher power - himself. John is an angel then, who magnifies the Lord? John is the disciples, who follow Jesus with steadfast faith and trust, wonderment and awe, who follow his commands without question… usually. John is the name of one of the disciples, one of the fishermen who became a ‘fisher of men’, someone who recruited more followers of Jesus. What did John’s blog do if it didn’t recruit believers in Sherlock, especially after he fell, with the Empty Hearse society and people such as that? Maybe that is reading too much into it, but enjoy how smug Sherlock would be at being compared to literally God.

Series 3, the third week of Advent: Joy, the shepherds, heaven.

Weird to associate joy with this series of pain from the perspective of Johnlockers, who have suffered so much at the hands of this series, but hear me out!

Sherlock comes back from the dead and is no longer aiming for peace for his friends. He is much more focussed now, and, in fact, realistic, although still off the mark somewhat. He is determined to give John a life of joy, with the woman he chose to marry. He creates all kinds of chaos (shooting Magnussen a notable example) to secure John’s happiness.

Shepherds guide and protect sheep, an animal with inferior intellect but that they care for nonetheless - you see where I’m going with this. Sherlock tries to shepherd John’s life into order, but then, as in the Christmas story, angels - Sherlock’s call to tell John how he feels, or face endless death and resurrection - in the form of his exile go to take him away. Up to the sky in a plane - heaven - oops, not quite. Back to Earth again. Sherlock can’t get into heaven until he does what he was brought back to life in this reincarnation/adaption to do: confess to John.

The Bible tells us that a wedding banquet is a foretaste of heaven, and here at John’s wedding banquet he gets an admission of fondness, and almost confession of love, the closest Sherlock has yet got - “a foretaste of the heavenly banquet".

No Sherlock, you definitely haven’t finished yet.

We get told as Sherlock’s plane comes in to land that “there’s an East Wind coming” - SherlockJesus is coming to pluck the unworthy from the Earth. We get that you like Sherlock, Mofftiss, but did you have to make him so transparently GOD??

Series 4, the fourth week of Advent: Faith, the wise men, and hell.

I make no secret of the fact that I’m less familiar with the fourth series, so if anyone would like to add any points here (or anywhere else to be honest) I’d love to hear more analysis.

Faith, again, a transparent one, Faith Smith.

The wise men are famously from the east - the east wind has arrived, with gifts fit for a king: an elaborate game for Sherlock to solve. But also causing accidental death - the wise men told Herod about Jesus, causing him to slay all the male babies in the kingdom, and Mary’s death happened because Sherlock returned, and why did he return? Eurus/Moriarty’s plans, the east wind, the wise men.

There are traditionally three wise men - three parts to the east wind. Eurus, Moriarty, and… Mary? That’s speculation. This needs more thinking about.

Of course, hell - we’ve all been in Johnlock hell for years now, but that’s not really relevant to this series. What IS relevant is that SHERLOCK is now in Johnlock hell - he’s putting himself through it, perhaps, but watch as he is punished for not confessing to John and John is hurt by Sherlock’s actions because of his aborted attempts to confess.

TFP shows Eurus’ games, which put Sherlock through the nightmares of those he loves being hurt. A private hell, built just for him. Or perhaps a purgatory, which after he suffers through it brings him close to heaven/Johnlock.

And Series 5, Christmas Day: Love, and Jesus.

Here we will have Christmas, with a present for everyone that we’ve longed for for generations: Johnlock becomes canon! The theme of love, of course, will be heavily present, and Jesus/Sherlock will at last be free of his earthly purpose - to come down, free us from the binds of Johnlock hell and ascend to a peaceful resting place, where his disciples/John will join him in the wedding banquet of heaven.

Well that’s that, my first attempt at meta! Once I wrote it out it got longer than I was really expecting, but I hope you all got something from it, and let me know if you also see an religious/advent metaphor in the show :)

#meta#johnlock meta#sherlock meta#sherlock#johnlock#tjlc#my metas suck#asip#tbb#tgg#asib#thob#trf#teh#tsot#hlv#tld#tfp#some thoughts and stuff#what else can I tag this as#john watson#Sherlock Holmes

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EMP, and the focus of each episode

One of the weirdest things about series 4 was that it seemed to be missing a lot of the Sherlock/John dynamic (platonic or otherwise) that has always been at the center of each episode. And it’s not just that Mary and Rosie are present – we hardly see Rosie distract John from crime-solving at all, and Mary was already a major figure in series 3. I wouldn’t attribute it to Mary’s death, either; this weird shift in focus happened during TST, before anything traumatic happened to cause a rift between Sherlock and John. It felt like John was barely in TST at all, especially after he was such a constant presence in TAB.

So, let’s take the events in order:

TAB was definitely still about our two main leads. It started with a return to their first meeting, showed John neglecting Mary in favor of spending time with Sherlock, and featured such lines as “There’s always two of us” and “Why don’t you two just elope, for God’s sake?” It also painted John in a rather heroic light, even if he was kind of a dick to Mary:

Aside from the obvious ACD reference, the Victorian setting of this dream has been generally attributed to Sherlock’s suppressed feelings for John. He imagines them back in a time when homosexuality was illegal, so that the lack of a real-life, possible relationship doesn’t sting as much. This can also reflect how he sees John’s psyche: John is quite repressed, and doesn’t like talking about his feelings; this interpretation of John is actually quite comfortable in a Victorian setting.

But then we get to TST. I actually wrote something yesterday explaining why I think that TST is part of EMP, and at the same dream-level as TAB; what’s weird about this is the sudden shift of focus between the two episodes. Sherlock had his big “there’s always two of us” moment, dove off the waterfall, and told Mycroft that he didn’t need drugs anymore… and then suddenly Sherlock is ignoring both Mary and John while waiting for Moriarty to return, but the whole episode gets thrown into Mary backstory and ends up turning into a sort of spy movie. Mary is the star of the episode; John hardly speaks, and when he does, it’s to supplement her narrative.

I keep saying “spy movie” because that’s really what it is: we have assassins, double-crossing, an entire montage of traveling across the globe while adopting new disguises, even a physics-defying leap in front of a bullet. If you want a good example of a Sherlock-style take on a mysterious woman’s past life in international crime coming back to haunt her and ultimately resulting in her death, just watch TBB. This is tonally different.

One of the big things that threw me off about TST was the Samarra story; we’ve never heard Sherlock do voice-over narration that wasn’t directly related to a case or the best man speech. The closest thing I can think of is John’s narration in TAB, which just reinforces the idea that this episode is likewise in Sherlock’s head. The obvious metaphors of sharks and water, and the big heavy theme of predetermined fate, all make this a very interesting contemplation on the Mary situation. If this is a peek into Sherlock’s mind, well then the subject matter makes sense: he’s just been shot by Mary, and is trying to figure out what sort of other dangers she might pose. TAB was just to sort out Sherlock’s relationship with John, and it came to a neat conclusion (“there’s always two of us;” John won’t leave Sherlock when he needs him most), so TST is his way of figuring out what to do about Mary.

It doesn’t end well.

Unfortunately, Sherlock is probably on a lot of drugs at this point (either in the hospital or on the airplane, depending on what you think Reality is), and it starts to really show. While cocaine came up in TAB, and Sherlock started off TST with a “natural high,” TLD tackles intense drug use and dissociation from reality head-on.

There are a number of things going on here, which I think can be attributed to real-life drugs influencing Sherlock’s thought process. We have John’s issues with hallucinations, shown through Mary (who is still very threatening, if you ask me); Culverton Smith’s memory drug, which could possibly be invented by Sherlock’s brain to explain why he feels like he’s forgetting something important; Eurus’s disguises, and Sherlock/John’s inability to recognize her as a threat; and the crazy drug sequence which just emphasizes how much Sherlock is losing it.

We also see techniques such as slow motion or ambiguous cutting (like in the scene with the scalpel, or the flashes of TV clips), which add to the surreal feeling of the episode as a whole. The fact that things that shouldn’t be there are clearly shown, like Mary’s “ghost,” is also very unnerving. The “case” (if you can really call it one) isn’t very important, in the long run; instead, Sherlock’s deteriorating mental state is given full focus.

In short, TLD is all about Sherlock losing his grasp on reality.

Then we get to TFP, which I would argue is probably another dream-level down, if we haven’t already descended a few. This is because John gets shot at the end of TLD, and so the entirety of TFP might just take place inside John’s head, within Sherlock’s. (Like a dream-within-a-dream, but all imagined by Sherlock.)

Now, at first I was a little bit unsure of exactly what the focus of this episode is: is it Eurus? (Does Eurus even exist? I don’t think so.) It doesn’t seem to be John, nor Sherlock, really, not in the way that TLD focused on him.

Could it possibly be… Mycroft?

Now, of course, I’m not saying that the whole point of TFP is to provide some sort of deep character exploration of Mycroft Holmes, but he certainly gets more screentime than usual. He showed up as a source of advice for Sherlock in TAB and TST, but now is given the chance to do some real leg work. He is also responsible for the Holmes family dynamic, since he has been managing Eurus and Sherlock from childhood, while probably also doing damage control with the parents.

There are plenty of Mycroft moments in this episode: we open with him watching an old movie, then there’s the umbrella-sword-gun, him as the client, the flashback to his childhood with Eurus, the whole Lady Bracknell thing, the patience grenade, breaking into Sherrinford in disguise, and the “brother mine” moment where he offers to die. Personally, I enjoyed him more than any other character in the episode, just because the rest of them felt a little flat. Mycroft, on the other hand, seemed to be softened slightly, and so that at least was interesting to watch.

So, basically, I would explain EMP like this:

TAB – Sherlock examines his relationship with John

TST – Sherlock considers the potential dangers that Mary poses

TLD – *interlude as Sherlock starts really feeling the drugs/dying faster*

TFP – crazy nightmare with some family themes, through Sherlock’s relationship with Mycroft (Eurus kind of came out of nowhere so I don’t think she counts as a deep familial bond)

This is why it doesn’t feel like the Sherlock-and-John show anymore. If we want to see that dynamic return, we’ve got to get back to reality first.

@sherlockians-get-bored @sarahthecoat @doveandfrog @221bloodnun

150 notes

·

View notes