#Piotr Michałowski

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Piotr Michałowski, Oddział Krakusów (Contingent "Krakusi" / Contingent from Kraków)

b. 1855, oil on canvas

#poland#polish art#polish culture#polish paintings#polish painters#european art#european paintings#polska#piotr michałowski#michalowski

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

round 2.7 poll 3

tap to view full images

Kucie kos (Scythe forging) from the series "Polonia" by Artur Grottger, 1863:

about the artist: grottger was a poor little meow meow who really wanted to participate in the uprising in 1863. he even came to lwów to join. but all his friends were like ARTUR BABY NO!!!!! YOU ARE A SICKLY CHILD (he was like 25 or something) so he stayed at home and while the uprising was happening he made the Polonia series depicting scenes from insurgents' lives. his brother was an insurgent and got exiled to siberia for it btw. and grottger also made a Lithuania series bc he was all about that Commonwealth restitution cause. and he continued to be obsessed with the uprising but who can blame him. i mean he also painted other things both historical and portraits of his contemporaries but this is what he is famous for i think

Szarża w wąwozie Somosierra (Charge at Somosierra) by Piotr Michałowski, c.1837:

propaganda: can't make a tournament without at least one somosierra painting. napoleonic era enjoyers lets gooo

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Piotr Michałowski, Grey ox and a peasant from Bolestraszyce

0 notes

Text

Political Jokes: A Polish Post-Communist Perspective

Impressed with the magic of DeepL translation, and being reckless enough to use it in a language I don’t know especially when the topic is at least partially for laughs (better than crying anyways) I have made Polish-English and Polish-Chinese 波兰政治笑话文章:波兰语-英语和波兰语-汉语的机器翻译] (think of it as comic relief for the Chinese comrades) machine translations two articles on political humor in Poland under…

View On WordPress

#China#Chinese#Communist Party#苏联#humor#humour#joke#Piotr Michałowski#Poland#political joke#politics#PRC#Russia#Soviet Union#USSR#共产党#政治笑话#中国

0 notes

Photo

A piece by the Polish painter Piotr Michałowski (1800–1855) who was well known for his depictions of horses .

Piotr Michałowski

169 notes

·

View notes

Note

how did you find your artstyle???

I have absolutely no idea how to answer that other than observing my fav artists and friends! The styles of many people I know and used to know really shaped the way I draw now, so did the art schools I went to and the museums I visited. It's been a really long journey to be honest, I struggled with my style for years and I started genuinely liking it very recently tbh! Considering what I like the most about my fav artists and trying to take inspiration from that (while doing it my way) is how I'd generally sum it up. If you are interested in these, my biggest influences right now would be

Iben Krutt

James Fenner

Seyorrol

Stanisław Wyspiański Jan Stanisławski Jacek Malczewski Józef Mehoffer Józef Chełmoński Piotr Michałowski

But there's like so, soooo many more I owe this to! And hopefully they know that for I am very thankful to them. 💛

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle of Somosierra (between circa 1840 and circa 1844)

Piotr Michałowski (Polish, 1800-1855)

#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#napoleon#military art#history#soldier#military#poland#polish history#1800s#france#uniform#war art

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Battle of Somosierra” by Piotr Michałowski, 1837 and also “Battle of Somosierra” by January Suchodolski, 1860

#history#art#poland#napoleon#spain#somosierra#polish art#polishart#history of art#historyofart#romanticism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bay Horse's Head by Piotr Michałowski (1800–1855). Oil on canvas.

Michałowski was a Polish painter of the Romantic period who was best known for his works depicting horses.

(Picture source for Bay Horse's Head)

#art#art history#piotr Michałowski#horses#horse#horse art#1800's art#19th century art#polish artist#polish art

182 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Selection of paintings by Polish artist Piotr Michałowski (1800-1855).

Source: Pinakoteka.

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Napoleon on a Grey Horse by Piotr Michałowski, 1835-1837, photo: National Museum in Warsaw

Seen on pinterest

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Piotr Michałowski,

Somosierra / Szarża w wąwozie Somosierra (Battle of Somosierra)

ca.1837, oil on canvas

#poland#polish art#polish culture#polish paintings#european art#european paintings#polish painters#polska#piotr michałowski#michalowski

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

round 1.7 poll 6

Hej! Kto Polak na bagnety!! (Hey, Poles, take up your bayonets) by Kamil Mackiewicz, 1920:

propaganda: i meannn this is already a propaganda piece xd its so iconic tho. also i think in english the title should be a very tumblry slogan of "POLES GRAB YOUR BAYONETS!!111!!111"

Szarża w wąwozie Somosierra (Charge at Somosierra) by Piotr Michałowski, c.1837:

propaganda: can't make a tournament without at least one somosierra painting. napoleonic era enjoyers lets gooo

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Piotr Michałowski, Polish Painters XIX/XX Century Series , Poland, 2012, 20 Złotych, Silver .925 (pad printing) , 28,28 g, Rectangular (40 × 28 mm) #poland #złoty #silver #monety #moneta #numizmatyka #numizmatyk #kolekcja #numismatist #coincollection #coinscollection #coincollector #coins #coin #coincollectors #painter #coinphotography #currency #worldcoins #rarecoin #coinhunting #phtooftheday #numismatic #numismatics #numismatica #numismatik #coincollecting #photo #numismatique #hobby (w: Poland) https://www.instagram.com/p/CUXon3VK1OS/?utm_medium=tumblr

#poland#złoty#silver#monety#moneta#numizmatyka#numizmatyk#kolekcja#numismatist#coincollection#coinscollection#coincollector#coins#coin#coincollectors#painter#coinphotography#currency#worldcoins#rarecoin#coinhunting#phtooftheday#numismatic#numismatics#numismatica#numismatik#coincollecting#photo#numismatique#hobby

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Piotr Michałowski - Stajenny trzymający siwego konia za uzdę (olej), 1842-1845, Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie.

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

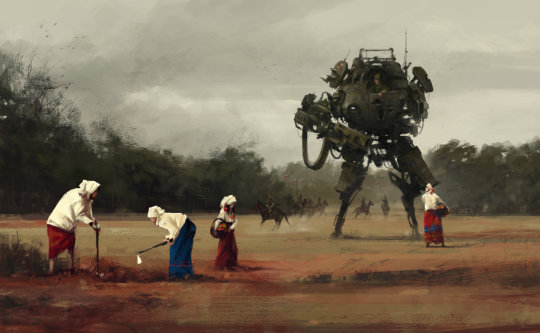

Mechanised Dreams and Peasant Imaginaries

As I have been teaching undergraduates on an Illustration degree, I have been paying even more attention to concept art and sci-fi/fantasy illustration than I usually do. In the past this attention has generally been unfocused and un-theorised, my enjoyment of these images being that of purely visual entertainment. However, a series of images by the Polish artist Jakub Rozalski recently grabbed my attention more than usual and prompted me to think a bit more about a couple of entwined topics: The role of the image of the peasant in the formation of national identity, and the fabrication of history. I have a particular interest in this, from an anarchist position, considering the rural poor’s involvement both in pre-modern revolt and in non-authoritarian leftist revolution. The narratives of “history” tend however to write the peasant in the role of defender of the nation and promoter of conservative values.

Rozalski’s series 1920+ consists of a number of diesel-punk digital paintings focussing on an alternate history of the brief Polish-Soviet War of that year. In these paintings the war is imagined as a science fiction conflict between giant war-mecha similar to that found in the Warhammer 40K universe. The imagery takes on the dark and oppressive feeling and the combination of high-tech war machines and primitive civilian subsistence of 40K, but instead of focussing on battle, the images rather present the pauses, or pre-battle manoeuvres of the machines in the countryside. Bringing to mind the Martian war machines striding across the English pastoral of The War of the Worlds – or the description of a jet engine loaded onto a horse and cart to be taken from the factory to the train depot in John Timberlake's Landscape and the Science Fiction Imaginary (2018 p.75). In Rozalski’s paintings it is true that “the future is already here, it is just unevenly distributed” (Gibson, 2018).

What makes these paintings interesting for me is that alongside these fantasy stylings they present a depiction of rural peasant life in pre-industrial Poland. A world where sheep are herded, and crops are scythed by hand by figures in traditional Polish dress – the world of 19th century Romantic and Realist nationalist painting. This is heightened by the similarity between Rozalski’s loose mark-making and that of the Polish Romantic Piotr Michałowski. This connection to the painting of the late 1800s is not coincidental; this was the period when the ideas of realism were put into the service of various nationalist projects. Cultural forms were deployed to bolster the credentials of both large states, but also subaltern and colonised populations; like the Poles. This search for a national identity through reference to the peasantry is traced by Margaret Carroll back to the northern Renaissance and the work of artists like Sebald Beham and Pieter Bruegel:

The growing assertiveness over native rights in the political sphere in the 1550s and 1560s was matched by ethnic self-consciousness in the cultural sphere […] the defense of native culture and customs promoted a benign attitude towards and even a sense of identification with the country's rural inhabitants. (1987 p.296)

The re-emergence of this identification with the peasant class in the 19th century is linked by T.J. Clark to the desire by the industrial bourgeoisie to reconnect with their recent rural past (1973 p.124). These viewers wanted to see the countryside, that they only now saw from trains, or on daytrips, and that their parents or maybe even themselves, had so recently escaped from, not as a place of poverty, ignorance, and grinding subsistence in the face of ever present famine, but rather one of plenty, relaxation, and harmony with the seasons and the earth. As Clark points out the initial realism of Gustave Courbet was met with anger from the Paris Salon because it refused to take part in this fiction; presenting the rural inhabitants of Ornans as individuals rather than as idealisations of a type (ibid. p.85). Later Realists did not have these scruples and were happy to idealise the rural poor, as can be seen in the work of Jean-François Millet and Jules Bastien-Lepage. A similar exercise was undertaken with regards to national identity with the Slavic Realists; Russian artists such as Ilya Repin used paintings such as Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed IV (1891) to foster a sense of Russian-ness or, in a Polish context, Jan Matejko’s history paintings and Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz’s depictions of national dress. These works drew attention to Poland’s past glories and current cultural distinctiveness as part of the push for an independent Polish state. This subversion of Realism and of history is a product of an understanding of the fictional nature of history post-Hegel where “writing history and writing stories come under the same regime of truth” (Rancière, 2004 p.38).

The idea that peasant dress is an unadulterated expression of identity is by and large a 19th century fabrication – most famously expressed through the invention of the kilt as Scottish national dress (Green, 2017). Griselda Pollock and Fred Orton examination of this in relation to the depictions of Breton peasant women by Parisian artists pointing out that these “traditional” forms were the result of the increased prosperity of (some) peasants during the previous century – “costume came to signify region, locality, class, wealth and marital status within a nouveau-riche peasantry” (1980 p.327). Ulinka Rublack argues that the assumption that peasant costume was “virtually immobile for centuries” (2010 p.262) is inaccurate – it is rather a product of this desire to see the peasant as an unchanging model for the national spirit. This links together:

A certain idea of history as common destiny, with an idea of those who ‘make history’, and that this interpenetration of the logic of facts and the logic of stories is specific to an age when anyone and everyone is considered to be participating in the task of ‘making’ history. (Rancière, 2004 p.39)

This can obviously serve to give the peasants a sense of their own agency as a political and cultural force, but that requires the peasant to identify with the image of themselves with which they are presented. If the identification only happens amongst the urban petit-bourgeoise who are looking for a hook to hang their nationhood on, then that can lead to a sense of “false” history of the type we are currently witnessing in right-wing populist discourse.

Taken in this sense one cannot help but see Rozalski’s paintings as a reactionary expression of nationalism – of the sort that is becoming grimly familiar across Europe, as borders are closed, and minorities hounded. The depictions of military hardware and agricultural labour could certainly be seen as part the blood and soil traditions of mid-20th century fascism, but is this necessarily the case? In his description of Kosciuszko Squadron on his website he refers to the 1920 war as being fought to preserve “Polish independence” which suggests, at least, an anti-communist position. However, looking at Rozalski’s other paintings outside this series there is no indication of any particular attachment to the contemporary Polish national project, and the celebrations of pagan traditions certainly demonstrate no love of Catholicism. Though this could be argued to be an alignment with fascist neo-folk paganism of the type discussed by Anton Shekhovtsov (2009). While Rozalski’s more traditional fantasy works do not escape from the characterisation of all fantasy as essentially backward looking and reactionary (see Michael Moorcock's 1978 essay; Epic Pooh), they do have a healthy anti-authoritarianism that it is difficult to square with any sense of national superiority or ethnic supremacy.

The 1920+ images themselves are relatively neutral, the Soviet and Polish forces are not depicted in moral terms, and the peasants are largely indifferent spectators to the conflict – an exception being The Youngest Sister, though the implication here is that it is the familial relationship that causes the connection between soldier and peasant. This brings to mind John Berger's quotation of a Russian peasant proverb: “Don't run away from anything, but don't do anything” (1978 p.346). It is this peasant tradition that I want to turn to now. Rozalski might be accused of valorising his peasantry, at a point when post-communist Polish society is undergoing a second “modernisation” (Tymiński and Koryś, 2015), but these peasant values can point towards a site of resistance of the mechanisms of both the state and capital.

It could be that Rozalski's peasants are indifferent because they know that it does not matter if either the nationalists or the communists win – because neither side truly cares about the peasants, the only people the peasants can trust is each other. “Unlike any other working and exploited class the peasantry has always supported itself and this has made it to some degree a class apart.” (Berger, 1978 p.346). The fact that the peasants have always been conscious of themselves as both producers and consumers of their own labour whose primary enemies have not just been the current ruling class (be that the bourgeoise or the industrial proletariat) who will extract their “surplus” before it is a surplus, but also both natural disaster but also the vagaries of war (ibid. p.347). It is this situation that in the ideological conflicts of the mid-20th century led the revolutionary elements of the European peasantry to cast their lot in with the Anarchist cause, rather than the Marxist communists. It was not until the emergence of Mao Tse-Tung that Marxism found a leader who could convince the peasantry of the value of communism. He did this by “embracing and enhancing, local tradition permitting rooted people to turn to the distant national leader into that saviour their legends, emotions and situations had long demanded.” (Friedman, 1976 p.120). Similarly, in Vietnam in the 1930s “the [Communist] party adopted the program of the peasantry not the other way around” – indicating that the peasantry could become a revolutionary political force, if convinced that the revolution would serve their interests (Scott, 1976 p.148). The supposed inward- and backward-looking peasant conservatism is not therefore to be confused with the conservatism of national chauvinism – though it is often exploited by it.

Peasant conservatism, within the context of peasant experience, has nothing in common with the conservatism of a privileged ruling class or the conservatism of a sycophantic petty-bourgeoisie. The first is an attempt, however vain, to make their privilege absolute; the second is a way of siding with the powerful in exchange for a little delegated power over the working classes. Peasant conservatism scarcely defends any privilege. Which is why, much to the surprise of urban political and social theorists, small peasants have so often rallied to the defence of richer peasants. It is the conservatism not of power but of meaning. It represents a depository (a granary) of meaning preserved from lives and generations threatened by continual and inexorable change. (Berger, 1978, pp.355-6)

This conservatism and indifference to the concerns that exist outside of those of communal survival is a vital mechanism for both the peasant’s security and their independence, the two being linking in the peasant’s mind. It tends to manifest as an accumulated knowledge – mētis – that is opaque to the external viewer and is therefore dismissed as reactionary or unscientific by progressive political theorists whose worldview is grounded in the (post)industrialised proletariat (Scott 1998 pp.324-5).

With Rozalski’s paintings we are therefore presented with a number of interlocking and potentially contradictory themes. Regardless of intention – there is unarguably a possibility that these paintings can be used to bolster nationalist rhetoric. Their science-fiction-ness is of a type that plays with dark authoritarian themes, and the peasants can be taken as unreconstructed symbols of nationhood. But I have argued that this straightforward reading is not necessarily the only one available and that the shepherds and reapers with their, by and large, indifference to the war can be viewed in the tradition of the peasant as distrustful of external forces and their disagreements. This argument fits in with a historical libertarian communist position that has been dismissed by orthodox Marxism – a dismissal that damages universalist pretentions of Marxism and makes the rural proletariat susceptible to conservative rhetoric.

***

Images:

ROZALSKI J., 1920 - The Youngest Sister. [viewed 8 April 2020]. Available from: https://jrozalski.com/projects/gJ39yQ

ROZALSKI J., 1920 - Kosciuszko Squadron. [viewed 8 April 2020]. Available from: https://jrozalski.com/projects/aYq8J

ROZALSKI J., 1920 - Harvest. [viewed 8 April 2020]. Available from: https://jrozalski.com/projects/lV92e

Bibliography:

BERGER J., 1978. Towards Understanding Peasant Experience. Race and Class, 19(4), 345-359

CARROLL M.D., 1987. Peasant Festivity and Political Identity in the Sixteen Century. Art History, 10(3), 289-302

CLARK T.J., 1973. Image of the People; Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution. London: Thames and Hudson

FRIEDMAN E., 1976. ‘The Peasant War in Germany’ by Friedrich Engels – 125 Years After. In: J. Bak. The German Peasant War of 1525, London: Frank Cass, pp. 89-135

GIBSON W., 2018. The Science in Science Fiction [viewed 4 April 2020]. Available from: https://www.npr.org/2018/10/22/1067220/the-science-in-science-fiction?t=1586007308697

GREEN C., 2017. How Highlanders Came to Wear Kilts. In: Jstor Daily. 25 December 2017 [viewed 4 April 2020]. Available from: https://daily.jstor.org/how-scottish-highlanders-came-to-wear-kilts/

MOORCOCK M., 1978. Epic Pooh [viewed 4 April 2020]. Available from https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/en361fantastika/bibliography/2.7moorcock_m.1978epic_pooh.pdf

ORTON F. and G. POLLOCK, 1980. Les Donneés Bretonnantes: La Prairie De Répresentation. Art History, 3(3), 314-346

RANCIÈRE J., 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics. London: Continuum

ROZALSKI J., Jakub Rozalski; howling at the moon. [viewed 8 April 2020] Available from https://jrozalski.com

RUBLACK U., 2010. Dressing Up; Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press

SCOTT J.C., 1976. The Moral Economy of the Peasant, New Haven: Yale University Press

SCOTT J.C., 1998. Seeing Like a State, New Haven: Yale University Press

SHEKHOVTSOV A., 2009. Apoliteic music: Neo-Folk, Martial Industrial and “metapolitical fascism”. Patterns of Prejudice, 43(5), 431-457

TIMBERLAKE J., 2018. Landscape and the Science Fiction Imaginary. Bristol: Intellect

TYMIŃSKI M. and P. KORYŚ, 2015. An Escape from Backwardness? The Polish Transformation as a Modernization Project. The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, volume 75

5 notes

·

View notes