#Pioneer Plaza

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Den 2. Tag in texas fuhren wir nach Dallas. Am Abend hatten wir in Fort Worth einen sehr schönen Abend in der Bar "The Wine Thief"

#Dallas#Dealany Plaza#Fairfield Inn#Fort Worth#Glory Window#J.F. Kennedy#John F. Kennedy#Kevin Costner#Lee Harvey Oswald#Philip Johnson#Pioneer Plaza#Six Floor Museum#Texas#Thanks-Giving Square#The Eye#The Trail#The Wine Thief#Travel#Trinity Railway Express#USA#Water Gardens

0 notes

Text

Tourist Office, Pioneer Place, Portland, 2015.

#urban landscape#plaza#tourist office#department store#pioneer place#portland#multnomah county#oregon#2015#photographers on tumblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

fremont street - las vegas (1991)

#fremont#el portal#union plaza#golden nugget#pioneer club#sassy sallys#fremont street#las vegas#downtown las vegas#nevada#1991#90s#vintage architecture#neon

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Public Art, Vancouver (No. 4)

Digital Orca is a 2009 sculpture of a killer whale by Douglas Coupland, installed next to the Vancouver Convention Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. The powder coated aluminium sculpture on a stainless steel frame is owned by Pavco, a crown corporation of British Columbia which operates BC Place Stadium and the Vancouver Convention Centre.

The sculpture was installed in 2009 and commissioned by the city of Vancouver.

In 2022, a group protesting the logging of old-growth forests in British Columbia spray painted landmarks around Vancouver, including Digital Orca.

The sculpture is located at Jack Poole Plaza in Vancouver, Canada. The sculpture depicts a killer whale created by black and white cubes, creating a visual effect as if it were a pixellated digital image. The sculpture has a steel armature and aluminum cladding.

It was described as "both beautiful and bizarre" in Architectural Design. John Ortved in Vogue said the statue "grapples with modernization and the digital age" by making the killer whale less scary.

Source: Wikipedia

#Fountain of the Pioneers#downtown#Vancouver#BC#British Columbia#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#architecture#cityscape#sculpture#public art#Canada#summer 2023#Jack Poole Plaza#Digital Orca by Douglas Coupland#Burrard Inlet#Pacific Ocean#Four Boats Stranded by Ken Lum#217.5 Arc x 13 by Bernar Venet#False Creek#Vancouver Art Gallery

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Olmec are considered one of the first great civilizations of Mesoamerica and developed mainly in what is today southeast Mexico, in the states of Veracruz and Tabasco. Its peak is between approximately 1200 BC and 400 BC. Some notable features of the Olmec civilization include:

1. **Art and Architecture**: They are famous for their colossal stone heads, some of which measure up to three meters tall and weigh several tons. These sculptures, along with other works of art, showcase a high level of skill and sophistication.

2. **Ceremonial Centers**: The Olmecs built large ceremonial centers, the most well-known are San Lorenzo, La Venta and Tres Zapotes. These sites included plazas, platforms and ceremonial mounds.

3. **Religion and Myths**: The Olmec religion was complex and centered around several deities, many of which were associated with nature, such as the jaguar, which was an important symbol. The Olmecs also developed rituals and practices that influenced later Mesoamerican cultures.

4. **Writing System and Calendar**: They are attributed to one of the earliest writing systems in Mesoamerica, although it has not been fully deciphered. They also developed a calendar, which was the basis for calendars of later civilizations such as the Mayans.

5. **Cultural Influence**: The Olmec civilization is considered a “mother culture” of Mesoamerica due to its influence on other pre-Columbian cultures, including the Mayans and Zapotecs. Their advances in agriculture, architecture and art laid the foundation for the development of these later civilizations.

In short, the Olmecs were a pioneering civilization in Mesoamerica, known for their monumental art, religion and mythology, and their lasting impact on the cultures that followed them.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Timeline of Fremont Street Experience

Construction of Fremont Street Experience, c. November 1994. Photo by Pam G.

Facing a stagnant economy and fearing that mega-resort projects on the Strip would further drain visitors to downtown casinos, Las Vegas City Council and downtown casino execs collaborated to create an attraction downtown which would become Fremont Street Experience (FSE).

'91: Feb., Mirage Resorts chairman Steve Wynn suggests Venice-style canal attraction for Fremont St. Jul., City council forms committee to study downtown revitalization.

'92: Jan., Downtown Progress Association hears redevelopment proposals from three firms, rejects all. Apr., City begins purchasing property for future development use. Jun., Architect Jon Jerde presents plan for Fremont Street Experience.

'93: May, LVCVA approves $8M funding for FSE. Aug., City Council approves tax increase for financing the construction. Nov., City begins procedures to condemn property of owners who refuse to vacate on 400 block of Fremont St.

'94: Mar./Apr., Demolition of south 400 block Fremont St (Block 35, Clark Townsite) for the FSE Parking Garage, the end of a protracted battle which included the City of Las Vegas filing eminent domain actions against property owners.

'94: Sep. 7, Fremont St closed to traffic, and construction begins.

'95: Jul., Construction completed. Inaugurated Dec. 14.

'95: Nov., FSE Parking Garage opens.

2004: The canopy's 2 million incandescent bulbs replaced with 12.5 million LED lamps. The new light show dubbed Viva Vision debuts Jun. 14.

2010: Oct., Temporary zip-line from 4th St to Casino Center begins operating, continues through 2013

2013: Mar., Construction of the 120-foot Slotzilla platform begins; conceived and designed by Contour Entertainment.

2014: Apr. 17, Slotzilla lower zip-line opened. Upper zip-line opens Aug. 31.

2019: The Viva Vision display is rebuilt with 49 million LED lamps, competed Dec. 31. The new canopy can operate in daylight hours.

2020: Mar., Opening of the "Historic sign" on the west side of FSE facing Main St and Plaza Hotel.

As of 2025, Fremont Street Experience makes money from Slotzilla zip line tickets, leasing to kiosks, Walgreens, and iHeart Media, and the parking garage at 4th & Carson.

Demolition of Fremont & 4th (block 35), 1994. City of Las Vegas acquired the businesses on this block, partly through eminent domain, and demolished everything to make way for the Fremont Street Experience parking garage. Last building standing is Cornet 5-10-15 (401 Fremont). Photo taken from the garage of Fitzgerald’s Hotel & Casino by Roadsidepictures.

Section of scale model of Fremont Street Experience. Photographed Dec. 15, 1994, by Greg Cava. A 22-foot long scale model of Fremont Street Experience was built at the office of Atlandia Design, which supervised the creation of the attraction. Greg Cava Photograph Collection (PH-00399). UNLV Special Collections and Archives.

The “Vegas Vic” sign re-installed at Pioneer Club, December 23, 1994 - Photo by Las Vegas News Bureau. The sign was removed days earlier while the platform was extended from the building and the character’s hat was shortened, to accommodate the construction of the Fremont Street Experience canopy. The “Vegas Vickie” sign at Glitter Gulch casino was also lowered to fit under the canopy. Before the work was done on the two signs, a marriage ceremony was held on Fremont St for Vic and Vickie. Vic’s best man was Vaughn Cannon of YESCO. Guest of honor was Edna Sherrill who had played a “Vegas Vickie” character as a hostess at Pioneer Club in the 60s.

Sources include: Creative thinking needed downtown. Review-Journal, 2/25/91; H. Stutz. Wynn proposes Venice-style downtown project. Review Journal, 5/21/91; J. Gallant. Council, casinos plan revamp panel. Review-Journal, 7/18/91; C. Scarbrough. City, casino execs discuss three themes. Review-Journal, 1/30/92; C. Scarbrough. Megaresort projects threat to downtown. Review-Journal, 1/31/92; C. Scott. “Tourists to pick up most of project tab.” Las Vegas Sun, 4/17/94. S. McKinnon. “Downtown celebrates neon nuptial.” Review Journal, 12/17/94. Chris Jones. A vision of things to come. Review-Journal, 6/9/04; Richard Velotta. Fremont Street Experience adds zip line attraction. Las Vegas Sun, 10/14/2010; Buck Wargo. Planned zipline unmistakably Las Vegas. Review-Journal, 11/28/2012; F. Andrew Taylor. Tourists take flight. Review-Journal, 4/29/2014; Oliver Lovat. How Downtown Las Vegas Came Together in Crisis and Created Transformative Legacies. Pub. on LinkedIn, 2/24/2025.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

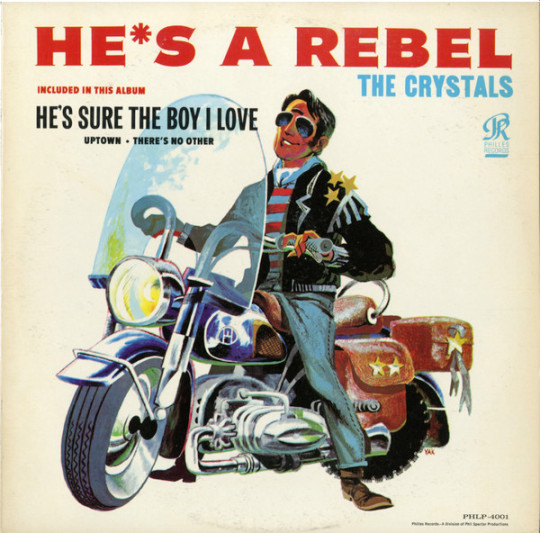

The Album That Inspired Little Shop of Horrors

Written by Calliope Avery

In June, while out of town to see my third production of Little Shop of Horrors, I found a sealed copy of an album I've had my eye on for awhile. It's notable to me not just because it's a great album, but because it holds the foundations for most of the music written for the musical Little Shop of Horrors. This album is none other than...

He's a Rebel by The Crystals!

Released in 1963, with songs recorded between 1961 and 1963, this album was both a smash hit and very influential to music going forward, much like how many other girlgroups were! But even more importantly, this was the album that Alan Menken and Howard Ashman used as the basis for the musical identity of Little Shop of Horrors as we know it!

Well, that fact is all but confirmed. I do have extremely strong evidence to support this claim, so let's go through everything together!

According to "Attack of the Monster Musical: A Cultural History of Little Shop of Horrors" by Adam Abraham, Ashman was greatly inspired by the gritty sounds and detached vocals of music produced by Phil Spector in the early 60's. Here's a direct quote from the book:

Indeed, Ashman grew up listening to the girl groups of the period: the Crystals, the Ronettes, the Chiffons, the Shangri-Las. For research, he began to revisit records by Phil Spector, the Bronx-born music producer who was, according to Tom Wolfe, “The First Tycoon of Teen." Spector pioneered the "wall of sound": a dense musical tapestry that doubled, tripled, and quadrupled the guitars and rhythm and included backing vocals, handclaps, brass, and strings. In the recording studio, Spector would demand take after take from his musicians. Rather than use the first take or two, when the musicians were still fresh, he wanted the twentieth, the thirtieth. After hours in the studio, their playing lost much of its personality; the musicians merged into a single unit, machine-like.

-Adam Abraham, Attack of the Monster Musical: A Cultural History of Little Shop of Horrors

The book also includes a direct quite from Howard Ashman:

I heard something I hear to this day-something very dark and horrifying and scary as hell in the Phil Spector sound. There's a BUNK-BUNK- BUNK-TSCH, BUNK-BUNK-BUNK-TSCH. There are chains and whips in the background. There's real dark, nasty stuff going on under some of these very innocent lyrics. And if that doesn't sound like a horror movie, I don't know what does.

-Howard Ashman

This Phil Spector sound influences both the lyrics of the songs in Little Shop of Horrors, but also the way the music itself sounds and how it's written. The entire soundtrack is deeply rooted in these 60's grilgroup pop ideas, which has rooted itself in many aspects of music today. This adds a timeless quality to LSoH's soundtrack, but by leaning even further into the unsettling aspects of Spector sound, it elevates this musical's specific type of horror. It's brilliant and very effective!

There's one more quote I'd like to share with you, one that clues us into which album specifically had the most impact on their vision and songwriting:

Ashman brought a record by the Crystals to Menken's place, in Manhattan Plaza, where they usually worked by the piano. Ashman announced that this would be the sound of their show; he called it “the dark side of Grease." "We started over again," Menken conceded.

-Adam Abraham, Attack of the Monster Musical: A Cultural History of Little Shop of Horrors

An album by The Crystals, you say? Hmm, I wonder which one it could be. Surely it couldn't be the one with a song that sounds nearly identical to "Skid Row (Downtown)" from LSoH's soundtrack...

The second number in the show, "Skid Row (Downtown)," is "a direct inversion of the Crystals' 'Uptown,"

-Adam Abraham, Attack of the Monster Musical: A Cultural History of Little Shop of Horrors

This was my first clue into "He's a Rebel" being the album in question. The aforementioned song, "Uptown", seems to be where Menken and Ashman took heavy inspiration from (if not outright stolen it) in both melody and lyrics. Take a listen for yourself!

youtube

Another notable song that they definitely pulled from has the same name as the album- "He's a Rebel." You might recognize this lyric, "He's a dentist, and he'll never ever be any good", from the song "Dentist!", but that lyric is directly pulled from the former song! It's the exact same line, they just replaced "rebel" with "dentist."

youtube

(Skip to 41 seconds in if you wanna hear the line!)

There's also a smaller reference that I discovered on one of my many relistens to the album. During the song "He's Sure the Boy I Love", our singer remarks that her boyfriend "doesn't drive a Cadillac car." In LSoH however, Audrey II tries to bribe Seymour into murder by offering to get him a Cadillac. So we can even see smaller references to the album within the musical, reinforcing just how influential it was!

It's also outright confirmed that the cut LSoH song, "The Worse He Treats Me", was directly inspired by the tone and subject matter of another song on this album. "He Hit Me (It Felt Like a Kiss)" is... an uncomfortable song, but you can definitely hear the lyrical inspiration. "The Worse He Treats Me" seems to be a satirical response to this song, playing up the objective absurdity of excusing physical abuse in the way it does.

Ashman and Menken wrote a song that focuses on Audrey's relationship with her abusive boyfriend, and the wellspring was yet another track by the Crystals, "He Hit Me (And It Felt Like a Kiss)," from 1962.

-Adam Abraham, Attack of the Monster Musical: A Cultural History of Little Shop of Horrors

Musically, the song takes plagiarism-level inspiration from a completely different song sung by a different girlgroup- "Leader of the Pack" by the Shangri-Las. The main melody of the song is taken directly from the guitar riff that carries the verses. Funnily enough, the music that serves as Orin's introduction theme in the stage show is the exact same riff, making it both a reference to "Leader of the Pack" and the cut song all about his horrible abuse. Pretty thematically relevant, I'd say.

There's actually a lot in LSoH that's inspired by the Shangri-Las! Their song "Leader of the Pack" proved rich in ideas to pull from and reference. Some of it ended up cut out, as described in this upcoming quote, but a good amount was kept in!

Besides the pop nightmares of Phil Spector, another influence was the New York-based girl group the Shangri-Las. "I already knew the Shangri-Las were funny in 1964," Ashman boasted. On the very first page of the first draft of Little Shop of Horrors, there is a stage direction that reads, “Shouted, a la the Shangri-La's." The line that follows, in the show's opening number, is drawn from one of the girl group's signature hits, "Leader of the Pack." Audrey, terrified by something, cries, "Lookout, lookout, lookout, lookout!" (This remained in the show, although in subsequent drafts it is assigned to someone else.) Other sly references follow. Later in the first draft, Audrey defends her dentist boyfriend: "Folks are always putting him down"; the other women on stage echo, à la the Shangri-Las, "Down, down, down." These latter two lines from "Leader of the Pack" were eventually dropped. However, when audiences finally meet Orin Scrivello, DDS, he is introduced thus: "Here he is, girls, the Leader of The Plaque." So Little Shop of Horrors recreates the popular music of the late 1950s and early 1960s and sees the world through the prism of doo-wop records and girl-group patter.

-Adam Abraham, Attack of the Monster Musical: A Cultural History of Little Shop of Horrors

Have you noticed that Orin keeps getting brought up? Ignoring how much it drives me insane that he manages to worm his way into everything I've ever done, there seems to be a reason for this. In the transition between Roger Corman's 1960 movie and Menken & Ashman's 1982 stage musical, the dentist character got the most substantial makeover. Orin Scrivello is almost unrecognizable from his roots as Dr. Phoebus Farb; more specifically, he seemed to have gotten a brand new coat of early 60's rebel paint. Let's take another look at the cover of the album we've been discussing.

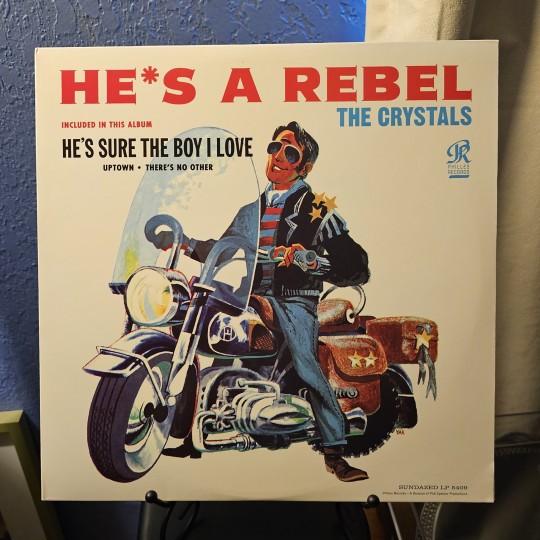

For variety, here's a picture of my own personal LP!

Now, what do you notice about this cover? Does the man pictured look familiar at all? Does he remind you of anything perhaps? Like, oh, I don't know... a certain dentist?

So I have absolutely no way to prove this, and I don't believe that this was the only inspiration taken for Orin's reimagining, but I do firmly believe that the cover of this album played a large part in the aesthetic that Orin would adopt. I mean, look at it. And with the added context of this album having so many influential songs, it wouldn't surprise me if seeing that album cover for extended periods of time would've made some creative gears turn.

I would argue further that this album's non-music related influence even extends to LSoH's themes and ideas. While not the entire focus of the album, reoccurring themes of class and wealth can be heard in songs like "Uptown" and "He's Sure The Boy I Love." Mentions of abuse and a difficult life are found in "He Hit Me" and "No One Ever Tells You." These themes, while prevalent, take on more positive and optimistic perspectives within these songs. Little Shop of Horrors takes these themes and responds with a much more pessimistic outlook. The exception to this are the album's themes of finding love regardless of what society might expect or want for you. I'd say it's the most prevalent theme found in the album; songs such as "He's a Rebel", "He's Sure the Boy I Love", "Another Country-Anothor World", and "Uptown" all demonstrate this idea. And LSoH seems to respect this one while even elaborating further with Seymour and Audrey's relationship.

My personal favorite is only found in one song: "On Broadway." The song sings idealistically about Broadway, and the singer states that she will someday make her way out of her small town to go have a life there. Both ideas, dreaming about a idealistic place and wanting to escape your current living situation, have been split between two songs in LSoH's soundtrack: "Somewhere That's Green" and "Skid Row: Downtown" respectively. LSoH's twist is that Audrey doesn't dream of a glamorous life on Broadway, she dreams of a cozy and domestic suburban life.

To keep myself from talking for the rest of time, I will cut myself off here. I hope you found this interesting, and I highly reccomend giving the album "He's a Rebel" a listen for yourself! It's definitely become one of my top favorite albums. In the future I would also like to do research and make a post about the impact that The Ronnettes and The Shangri-Las had on LSoH, but work has me pretty busy lately, so I'm not sure when I can get that out.

Anyway, thank you for reading all of this I very much appreciate it! :]

#lsoh#little shop of horrors#the crystals#hes a rebel#orin lsoh#<- tagging him cuz he kept getting brought up. ugh whatever#also this has been in my drafts since JUNE. jesus christ

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Observations on stone astrolabes

I briefly mentioned in my ramblings about the two moons of the Lands Between that the stone astrolabes—the half-bowl dials where we typically collect starlight shards—tend to point subtly toward or away from narratively relevant characters, items, or locations. I figured I would check as many as I could, whether these syzygies were deliberate or not.

In Elden Ring's cosmology, astrology is a school of learning that is regarded as archaic and as anathema to the Golden Order. Pioneered by ancient inhabitants of the northern mountains, the Astrologers divined fate from the stars, until its fettering by Radagon upon his marriage to Rennala, Queen of Caria.

Even so, the stone astrolabes dotting the landscape may be thought of as relics of the long lost Astrologers. Realistically, an astrolabe would be used to map the celestial bodies, but in Elden Ring, they appear to relate to the map itself (usually).

I've started to log said alignments (deliberate or not) by physically heading over to each astrolabe, facing either toward or away from them, then placing a beacon on any points along my path that seem connected by the narrative. In many cases, the beacons as they appear on the compass at the top of the screen will merge into one, indicating that they fall on a straight path. (This can be tricky to do as there's no way to reliably trace a line on the map using a controller, so sometimes my beacons may be off by a slight margin.)

Examples of alignments found thus far

Greyoll's Dragonbarrow – Outside Bestial Sanctum. Points toward Maliketh, the Black Blade. Points away from Summonwater Village (where a Deathroot is collected by defeating a Tibia Mariner).

Mount Gelmir – Near the Full-Grown Fallingstar Beast. Points to Black Knife Catacombs; Ranni's discarded flesh atop Divine Tower of Liurnia.

Moonlight Altar – Cathedral of Manus Celes north transept. Points toward Rennala (or perhaps the Dark Moon Ring?); Royal Moongazing Grounds; the north moon. Points away from Ranni's Two Fingers.

Liurnia of the Lakes – Cliffs east of Gate Town Bridge. Points toward Lakeside Crystal Cave (which leads to Latenna). Points away from Ordina, Liturgical Town.

Flame Peak – Northern cliffs. Points toward First Church of Marika. Points away from Stormveil Castle's throne room. (This one requires a bit of explanation: First Church of Marika is where Melina shares Marika's spoken echoes in which she commands Godfrey to brandish the Elden Ring and put the giants to the sword. Stormveil Castle is of course Godfrey's former base, inherited by his lineage.)

Redmane Castle – Beyond Redmane Castle Plaza. Points toward a shipwreck off the coast of Wailing Dunes. Points away from Morne Tunnel (where the Rusted Anchor is found.) I just find this one funny.

Greyoll's Dragonbarrow – Near Church of Plague. Points away from Valkyrie's Prosthesis.

My reaction to this information

Perhaps I'm just reading into this too deeply and seeing what I want to see, but something tells me the developers were exceedingly keen to the consistency of worldbuilding and how the player may interact with it.

However... these aren't the only types of map alignments. Some are even more subtle, but I don't think I ever would have noticed them hadn't I picked up on why the astrolabes were placed in such peculiar locations. But I'll get to those later.

Feel free to hit me up with any other astrolabe alignments you might find! At some point, I'd like to compile them into a map, if I can.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Summer in a Pioneer's Neckerchief/Лето в пионерском галстуке - Chapter Eleven

Master post here

Chapter Eleven - This Place Will Resound with Music

After wiping away the remaining shards of glass from the windowsill with the uniform, Yurka climbed out of the counsellor’s dorm. Leaving the dandelion field behind without regret – it had taken on a very pitiful look – he left for where the sports area used to be. In his youth it had appeared vast to him, but now it was just a sad little overgrown patch of land.

Everything seems bigger and more important when you’re young, he thought as he encircled the courts. He sighed and shook his head – thoughts about the inevitable passage of time and how merciless it was to everything kept obstinately creeping in. Like a plague, it killed everything it touched.

Afraid of tripping over the chunks of asphalt lying in the damp grass, Yurka looked beneath his feet, at the jagged orange lattice of metal that lay as though growing out of the ground. At some point this lattice had demarcated the court; at some point, Volodya, had, so unexpectedly, held onto it as he apologised about the magazines and talked to him about MGIMO.

I wonder whether he graduated?

His gaze was caught by a dark clump sticking out of a bush growing by the canteen wall. Yura got closer to it. Narrow rectangles were strewn among bits of broken bricks and fallen leaves: the black ones were smaller, the white ones were larger. Piano keys. And the instrument itself was there: broken, with the panels falling off and the lid smashed. On a piece of wood that had once been the front panel, the golden inscription of its name, Elegia, was preserved, and the hammers were also strewn around, while from the inside of the piano, the remains of the strings stuck out.

It almost caused Yurka physical pain to see an instrument from his childhood destroyed thus: How did it get here? The theatre isn’t close by… It was probably the villagers from Goretovka. Back when Goretovka was still here. And they had the sense to pull it out and roll it down to the plaza. But once they’d gotten it out, why smash it? People didn’t leave any stone unturned in the whole village, and this is a piano we’re talking about…

Elegia… He remembered that model of piano – in the USSR it was one of the most popular. Nurseries, schools and other institutions tended to buy those ones more often than any other. The pioneer camp Lastochka was no exception. One just like it, brown, could be found in the theatre and was used at all the rehearsals. Masha had played it, and–

Yurka reached out and touched the scattered keys. He remembered them not as they were, but as being spotless and sparkling. If they had a memory of their own, then they would not have recognised his hand, either. His hands were different back then – youthful. Yura looked at the sad picture of his aged hands on the old keys, entranced. How similar they were.

Old pictures from his memory burst into life before his inner eye, indistinct, flat. But it was as thought time suddenly whirred backwards and the keys turned white before his eyes, and the fingers on them, young and inexperienced.

The picture came to life and acquired lifelike definition and detail, full of sounds and smells – the theatre, evening, the summer of 1986, and him, young, in the theatre, in summer. He was there as an adult there too, with all his thoughts.

***

“Yur, get up! Come on, Konev, get up already! If even one person is late for morning exercise, we won’t get the best title.”

Morning exercise. Breakfast. Lineup. Communal work. Theatre. Volodya would be everywhere. There was nowhere to hide from him. Yurka had told him everything, Volodya now knew all the places where he might have hidden himself. Volodya would find him and ask, “Why did you do that?”

He could not get up, not that day of all days.

“Yur! Come one, Yur, wake up and let’s go,” whined Mikha as he tore his blanket from him. “Hey, why are you dressed?” He was taken aback, but Yurka said nothing in response.

That Volodya would not just stand in one spot and would instead immediately go looking for him no matter where he hid himself, Yurka had already guessed the day before. That was why he ran straight there, where the counsellor would only think to look for him as a very last resort – his own troop dorm. Without undressing, he had dived under his blanket. Volodya appeared while everyone was sleeping and did not dare to wake anyone up.

Yurka could not remember whether he had slept or not. Generally speaking, he did not know what he had been doing that night. He had closed his eyes, but had he slept?

He rose from the bed, shook the apple leaves off from his bedsheet – he had brought them along with him from the disco – changed his clothes in silence and plodded off towards exercise.

It turned out that it was very comforting to walk in rank and file: there was no need at all to lift his gaze from the ground. You drag yourself along, looking at the feet of the person walking in front, in absolute calm – the column would bring you somewhere. And so it did. To the sports area, where the whole camp was gathered for exercise. And Volodya as well. What he would have given to get out of there!

How comforting it turned out to be to watch the shadow of the person standing in front and repeat his movements. Yurka physically could not lift his head; even though he was being shouted out that he needed to lift his chin and stand up straight, he could not. Volodya was everywhere. They would necessarily, inexorably, inevitably meet, their gazes would cross each other. Of course, Yurka was not going to faint, but he could not simply stand. His feet were nailed to the ground, while his body was paralysed, but all the same, Yurka had to do whatever he was asked without fail. He would take out all his anger and hatred out on himself – for example, he would bite his tongue if all else went numb. But his tongue was not his enemy. That for which Yurka hated himself was not something he said, rather, something he did. Why had he done it?!

The lineup. The first troop traditionally stood opposite the fifth. He and Volodya were the tallest amongst those present, and like everyone else, they had to look straight ahead. But Yurka did not follow the rules, as he felt Volodya’s gaze. That gaze did not freeze him and neither did it burn him; it strangled him, to the extent that his face went a little grey.

The anthem. The flag. He needed to raise his hand in salute. He was allowed to look upwards, and that was good, comfortable, because it was not straight ahead.

The orders rang out, and Yurka was sent to be on duty in the canteen. On the way, he noticed that the avenue of hero-pioneers had outstanding asphalt. It was grey and smooth, patterned with shadows cast by the birches growing along the side, made motley by the specks of sunlight that penetrated through the leaves. What was strange was that these little bits of light would focus into little blobs and then disperse like drops of pigment in water. Or was everything normal with the asphalt, and the problem was with Yurka’s eyes? The problem was naturally with Yurka. Why had he done it?

As he arranged the tables in the canteen, he tried to make peace with the thought that he had no future. That after his actions the previous day, all that remained to Yurka was the past – their brief friendship had left for ‘yesterday’, everything positive had gone away: Yurka’s leniency towards himself, his self-respect, his self-esteem. All the while, his misunderstood feeling for Volodya stayed exactly where it was.

While he laid the tablecloth, Yurka decided that this feeling – whatever it was called – needed to be forgotten, and quickly, since no matter what he did, at any reminder of Volodya, he was without fail disgraced by the memory of his shameful deed. Then he would remember his answer as well: You stop that! No, this feeling would not allow Yurka to live in peace. And he wanted to live!

But Yurka knew that somewhere out there, beyond the fence of the camp, without shame or the risk of meeting each other, he would definitely have a life. Somewhere far away spread far and wide an inviting terra incognita where freedom was certainly waiting for Yurka. But freedom was out there and not where he was, not in the camp, not nearby. If only he could run far away from there, off towards the horizon. No, not ‘if only’, rather, ‘he needed’. He had to get out of there!

Yurka drew his spoon around his bowl. He ate slowly, but obediently; he just did not know what it was exactly that he was eating – he was not paying attention. In his bowl, a very large piece of meat floated around, a yellow stain in something tasteless and whitish. In his left hand, some bread was crumbling, next to him stood a glass, but what was in it, tea or cocoa, Yurka could not have said either. Someone sitting opposite him took a drink – Yurka drank as well; he ate – Yurka ate as well, not because he wanted to, but because someone said he ‘needed’ to.

He stood up from his spot, right at the very moment that the whole fifth troop with both its counsellors left the canteen. Whilst the others on duty were cleaning the tables, Yurka lugged trays of dirty tableware around and thought about what he would do next.

Exercise, lineup, work – he would survive all of that, he would survive that day somehow. But the theatre? His role was so small, anybody could manage it, Yurka was not really needed there, much less when he was in a spat with Volodya. Maybe Volodya would take pity on him and exclude him from the troupe? That would be good. Then there would be less encounters, less words, and less regret. Maybe Yurka would even learn to live in such a way that he would not catch his eye at all? Maybe he would get used to him not being around? Volodya would not be around in any case. Not the Volodya that he had been with Yurka before the previous evening – kind, interesting, airy, like a brother. But sooner or later, Yurka would have had to endure this separation anyway. Sooner or later, he would have had to fall out of love with him.

So that the girls could clean the floor, Yurka was charged with putting the chairs on the tables. As he dutifully carried out his task, he was from time to time surprised by how heavy the chairs were since they had nothing heavy in them – just a seat, thin as plywood, and aluminium legs. He grew tired quickly, but stubbornly continued to pick up one after another – during such tedious work, his thoughts could not wander somewhere too bad.

What would he do when they inevitably met, and Volodya asked, “Why did you do that?” Since naturally he would ask, this was Volodya after all.

Yurka pleaded to who-knows-what, I hope he never speaks to me again! Don’t even let him come close, let him pretend I don’t exist, don’t let him even look in my direction, so long as he doesn’t ask about anything! Yes, it would be terrifying. Yes, it would be a lot of trouble, but Yurka was strong; he would withstand both the disdain and the hatred. Concerning disdain and hatred for Yurka, he and Volodya were allies. Let at least that remain as their last thing in common.

Yurka would let anything and everything happen, just as long as he did not ask him. But he would ask him! It was Volodya! And what would he say in response to the fully reasonable question ‘Why?’ Why had he done it?

Yurka went to the centre of the hall, meaning to sort out all the chairs there – the floor was already cleaned. He reached out his hands and flinched – from behind his back came a quiet, painfully familiar voice:

“Yura?”

He’s come! Yurka stared straight ahead of himself, his heart in his throat.

The spacious canteen, with its glazed tile flooring and simple, white, weightless furniture, bright and clean as an operating room transformed in a flash into a dark crypt. The black walls, covered with cracks, were settling and crumbling slowly around his shoulders.

“Yura, what’s going on with you?”

Yurka, repressed and bereft of the gift of speech, could manage neither to squeak, nor to breathe, nor to budge.

“Let’s go outside, we need to talk.”

He laid a hand on Yurka’s shoulder and very lightly gave it a shake, but Yurka merely shrunk his head into his shoulders in silence. However, the PUK girls, also on duty in the canteen that day, accosted them. Volodya, without ever letting go of Yurka’s shoulder, spoke with them and might even have smiled, but Yurka could feel the hand on his shoulder trembling from irritation.

Having at long last disentangled himself from the girls, Volodya hissed through his teeth in Yurka’s ear and the chill in his voice seemed to make the floor quake.

“Yura, I said let’s go!”

Without even waiting for any kind of answer, he squeezed Yurka’s hand and dragged him out of the canteen.

Yurka did not take notice of how he got outside. A white vestibule, a creaky door and a grey staircase, it all flew past rapid-fire before Yurka’s eyes, just like his whole life in general. The humid morning air touched his cheeks; Yurka had appeared out on the porch – Volodya sat him down, while he himself cast a huge, dark shadow over him.

“Explain to me, what happened last night? What did all that mean?”

I kissed you. Obviously because I’ve fallen in love with you, Yurka attempted to answer, turning it over in his mind, as though trying out ‘fallen in love’ for taste. He did not like the taste – it was insipid and false, but it was just that no other explanation came to him. The Yurka tried to respond with ‘I like you’, but the words caught in his throat, and he could only choke out:

“I don’t know.”

“How can you not know? What was it, some kind of joke?”

Yurka flinched involuntarily. He could not look up at Volodya. What a strange look – his head felt so heavy that he could not understand how his neck did not break. Yurka diligently tried to pick out some words. he searched with all his strength for an answer anywhere, scanned through all the grey asphalt – if he could not find an answer within himself, then perhaps he would find one there?

Volodya, pacing back and forth as he waited, dragged his toes across the asphalt in impatience and breathed loudly. Waiting did not come easily to him. But what to say in response to him, Yurka still did not yet know, and while his eyes wandered from his hands to his feet and back again, he made a barely audible sniff. The silence, it seemed, had begun to drive Volodya crazy; he was dragging his feet louder, exhaling more angrily, on top of which he also began to crack his knuckles. Then he abruptly dropped to his haunches in front of Yurka, looked him in the eye and struggling to maintain a gentle tone of voice, began:

“Please, explain to me what’s going on with you? At the very least, for as long as we’re friends, I’ll hear you out, I promise. Say that you were joking, or it was to make fun of me, or even that it was revenge, and I’ll get you, say that it was an accident, or you didn’t really want to, and I’ll believe you.”

Yurka grinned mockingly – Volodya was giving their friendship a chance, making a naïve attempt to preserve something at least. Yurka understood that, but instead of playing along with the lie, he spat on everything, gathered his strength and breathed the truth out:

“I wanted to.”

“What?” Volodya fell apart. “You ‘wanted to’? How could you want to?”

Yes, he had given him a chance, but Yurka did not for a second doubt that there was no point to it. The past would not come back. That bright and pure something that had warmed up between them would be no more. All that remained to them was restraint, insincerity and discomfort. And it was him, Yurka, who was to blame for all of it.

“But Yura, you can’t!” Volodya was of the same mind as him. “This kind of joking around is very dangerous! Forget you ever even thought about that!”

Volodya sprung up and, after turning away, froze. He stood like that without moving, and then began to pace back and forth again. Yurka watched his shadow flit from side to side and felt with his whole heart like the world was crashing down around him.

The collapse had begun the day before, when, by his foolish act, he had unleashed a wild catastrophe. It inexorably approached him and finally caught up to him no more than a half hour before, in the canteen, when it shook the floor and knocked the walls down. At that very moment, Yurka was in the epicentre.

He gathered the last crumbs of his self-control and in a lifeless voice, deep to the point of hoarseness, he muttered, not hoping for anything in particular:

“But you said that you’d get it, that we’re still friends.”

“What kind of friends can we be after this?”

Everything came to a standstill, both inwardly and outwardly. The wind died down, the sounds quietened, but suddenly, from somewhere far off, almost another universe, came a child’s scream. Not a scream of joy, like usual, but of fright.

Volodya froze on the spot and ordered:

“Wait for me here.”

But he had only taken a couple of steps before Yurka jumped up and broke off to the side. In a flash, Volodya caught him by the wrist and forced him to sit in his spot. He did not let his hand go.

“I’m not done yet.”

“So, we’re not friends anymore. That’s the lot of it!”

“No, that’s not all. I’ve told you a hundred times, you’re playing stupid and dangerous games. But this!” his voice broke off. Volodya just barely restrained himself from shouting, instead starting whisper forcedly, “Never say a word of what happened to anybody, not one little hint; really, you’d do well to forget all this, like a bad dream. And don’t you dare let yourself even think about anything similar in the future!”

He was squeezing his wrist tightly to the point of pain; Yurka, flinching, did not let a single sound escape. “Volodya!” rang out a squealing, female scream. Yurka did not recognise the voice; at that moment he was not in the state of mind to recognise anyone or anything. “Let’s go, quickly!”

For the first time in Yurka’s memory, Volodya failed in his duty and, instead of rushing without hesitation to where he was being called for, he did not move from his spot and shouted:

“Can’t you see that I’m busy?!”

“Sorry, but there’s… Volodya, it’s Pcholkin again. Sasha’s fallen!”

“Just a minute!” Volodya roared at her, then bowed to Yurka and spoke clearly:

“Wait for me here. And not one step in any direction!”

“Volodya!” the girl burst out sobbing. Yurka only then recognised the voice – it was Alyona from the fifth troop, she was playing Galya Portnovna in the play. “Volo-o-odya! Pcholkin blown the carousel u-u-up! Sanya’s nose is broken, there’s blood all over the playground!”

Volodya went pale and, finally disentangling himself from Yurka’s arm, lightly pushed him aside. He hissed through his teeth, “What a bitch!” and ran off to where Alyona was pointing. Yurka remained alone.

How shameful. He had ruined everything, just got in the way and trashed it. He wanted to fall through the earth, to disappear, to vanish, so that Volodya would never see him again. To be wiped from his memory, so that he could not even think about him.

They were not friends anymore. Volodya would sit Yurka down in front of him for a talking-to in just the same way another time, maybe even another couple of times. Without meaning to, he would torture him, make him repent, though it already would not serve any further purpose. But then would he satisfy his own curiosity, extracting from Yurka, already so downtrodden, all the grisly details? And then what? Would he begin to bully him? Oh no, Volodya would not! He would be even worse – he would present him with the same contempt that Yurka had been ready to stoop to an hour ago. But that was before Volodya had said ‘What kind of friends can we be after this?’, before Yurka understood that he had, in fact, destroyed their friendship. Truly, they were nobody to each other now. That is, Yurka was nobody to Volodya, but he himself had forgotten nothing yet.

And how was he to live another whole week near to Volodya, trying not to look at him, nor to show his face in front of him, so as not to remind him about that degrading kiss. Should he hold himself back while looking at him? Should he speak to him only at rehearsals and only about them, without the slightest hope of hearing even one kind word about himself? This had all become vitally important to Yurka; what he needed now was understanding and gentleness, if not reciprocation. But receiving it was a different thing entirely. Coldness from that person who, over the course of a couple of weeks had become closer to him than anyone else, from whom he had seen and felt caring, even tenderness. Yurka was inevitably going to lose his mind. No, he had already lost it!

What was the point of that camp without Volodya? Why should he torture himself by living there, near to him, but without him? Just to suffer from stabs of remorse, to burn up inside from the shame? Yurka had not liked this place from the very first day of the season, after all.

The intrusive thought that had been whirling round his head all morning bubbled up to the surface once more and twist round and nag at him: I’ve got to get out of here!

He stood up, tore off his armband that showed that he was on duty, threw it down at his feet and took off from that damned porch. He ran along the path towards the avenue, out of his mind. He was kept moving by one goal alone, he understood one thing along: he needed to beat it from that camp – and all the better if he never came back!

He paused only when he suddenly found himself before the bust of Marat Kazej.[1] He shivered as he looked on the face of the hero-pioneer – even he, made of gypsum, was looking at him judgingly. This is some paranoia, huh, thought Yurka and turned to the left – the avenue led to the very centre of the camp, to the plaza. No, there was nothing for Yurka to do there. He looked straight ahead – the path to the construction site, where the empty hiding place with his tobacco was; he looked to the right – that way was the gate, the exit from the camp, that way was freedom! To the point, there were neither any pioneers on duty, nor watchmen. They’ve probably all run off to the commotion that Pcholkin’s caused. Let that hang on their heads! thought Yurka as he rushed towards the exit.

The heavy gate screeched as it opened onto the road and the thick forest, no match for the bright camp. It even smelt differently there – cleaner, and easier to breathe. That is how freedom is – at first, it’s just smelt and makes your head spin, and you only sense it with your mind afterwards. Yurka ‘sensed’ it with the thought There’s no Volodya here; we absolutely won’t run into each other out here!

He dove into a thicket. He set off through the forest on purpose – he was afraid that the guards had not gone far and that they might notice his departure. Hiding behind the trees, he stomped along the camp’s dead-end route to the main road, where the cars and buses drove by and formulated his plan of escape. The way ahead was long, he had plenty of time.

The first question: when should he make his escape? Not right then, he had neither clothes, nor money, nor the key to his home with him. It would be better to try at night, while everyone was asleep. No, morning was better. He would have to hide somewhere not far from the camp and wait for the first bus to come along. Where to wait in the meantime, he did not know, for Volodya already knew all his spots; he would need to find a new one. In the forest, perhaps? The walk would be the same as it was then, along the forest path, since Yurka would be easily noticed on the road. It would be a good idea to bring water and even just a little food of any kind with him. That day, Yurka planned to do the following: reach the bus stop, memorise the route to it and take a look at the timetable. Did a lot of them come by there? Well, at the very least, one of them would definitely have to go to the city bus station. Thence homeward.

He suddenly remembered the smell of his home. In the kitchen: slightly stuffy and sweet. In the lounge: dusty, the smell of paper from the large, open-shelfed bookcase that ran along the walls. Then the smell of his room intruded upon the memory – the aroma of wood and lacquer from his piano. How quiet and peaceful it was there, and to think, Yurka used to find it boring.

The next thought was an anxious one – Yurka was not expected there, he was going to appear suddenly. He would say it straight – I escaped from camp, please take me in. His mum would scream, and maybe even cry, while his dad would begin to manipulate his conscience – he give his son a look full of disappointment and be silent. And the silence would last a long time, perhaps even until autumn. It would be better if he applied his soldier’s belt ‘down there’, but no, he would do and say nothing. He would start haranguing his son, torturing him with long, sorrowful gazes that cried ‘I’m disappointed in you’. That gaze was worse than anything.

Yurka reflected for a moment; maybe he would not run home, but to his grandmother on his father’s side instead? She loved him dearly, she would say no word against him; on the contrary, she would secretly be glad and would not give him up to anybody. The idea was very tempting, but Yurka reined himself in: Hiding behind my grandma’s back? Chickening out? As if! As though I don’t already have enough to be ashamed of. My parents would go crazy when they’re told that their only child, dearly beloved, has gone missing for real. What would happen to my mother? Ach, but father! He’d stay mute for the rest of his life!

Yurka traipsed slowly. A kilometre away from the camp, the forest started to grow wild; in places, he had to climb through bushes and fallen trees. The path turned out to be difficult. Once, Yurka’s foot even sank into the soft, wet mud and he got stuck, as though the camp did not want to let him go and was trying to make him turn back. Yurka himself wanted something else – to cry. Pitifully so, like a child, since, no matter how he distracted himself with the planning of his escape, however he suppressed the painful thoughts, laden with melancholy and hurt, about Volodya, they bubbled up to the surface all the same. The tone of voice he had spoken in, the way he had looked at him when he squatted down, it was just like his father – with disappointment and sorrow. No, he must not think about that. Better to think about the escape instead. Better to think about crime and punishment.

What would Yurka’s parents do to him for this? Well, what could they do – ground him? Hardly, he was too old for such punishments. Not give him pocket money? That would be a shame, but not the end of the world – Yurka rarely had twenty kopeks to rub together in his pocket, he was used to it. Maybe they would send him out of the city to his grandmother in the orchard? They might as well, this option was the most appealing for them: it was not for nothing after all that his mother threatened while angrily wiping her hands on her apron that, if Yurka fought with someone at camp again, then they would send him to do time in the orchard. Yurka had frowned then, and made it look plausibly like the threat had worked, he even choked on his soup, but in reality, he was not scared at all – he had friends in the garden, Fedka Kochkin and Kolka Celluloid. They would, like in the year before, go roaming round the orchard at night on guard duty, catching hooligans and hedgehogs. There was not just Fedka and Kolka to make the orchard good, there was also their cousin Vova. If the first two were a bit younger, then Vova was older than even Yurka. Yes, definitely older, he had already finished school, he was, more than anything, of an age with Volodya and was just as sensible and a little boring. They even had the same name – Vladimir.

No, what a cruel and terrible world it was! There were reminders of Volodya everywhere, there were Volodyas everywhere. Was it really surprising, however, that, given that the leader of the world proletariat was none other than a Vladimir, half the country bore the same name? The name, by the by, really was very handsome – Vla-di-mir. It was music, plain and simple.

As he chanted the name in his head, Yurka caught a snag and almost fell flat on his face. And yet he would miss him terribly. He would regret ruining everything. He would never see him again. Ever. At all. After all, Yurka did not even have a photo to remember him by – they were printed at the end of the season.

The road reappeared through a gap in the trees, and about two hundred metres down it was the bus stop. Grey like concrete, blocky, monolithic as though hewn from rock, it was very pretty – the light blue canopy stuck out like the outstretched wings of a plan or a swallow. Just below the canopy, in broad, iron letters, rusted in places, was written ‘Pioneer Camp’.

The way there had not taken much effort, and neither did memorising the timetable. All of one single bus route passed by that way, the 410. Yurka was surprised: he had never once in his life seen a three-digit bus number. The bus began its journey at a little past six in the morning and would reach this stop at ten past seven. Yurka nodded and committed it to memory. He took another quick look over it as he left. The timetable was old – there was a wide crack where the route number was written, so perhaps it was not number four hundred and ten, but that was not important – the main thing was that it terminated in the city, at the bus station, where Yurka would certainly see a lot of three-digit numbers.

Having gathered the information for his escape plan, he took a look around and felt unexpectedly calm – a peaceful atmosphere reigned there. The idyll of the deserted road, of the rustling forest all around, of the coolness beneath the roof of the old bus stop was completed by the pure blue sky, in which dozens of light parachutes drifted weightlessly down to the ground like white umbrellas. Yurka smiled: how good it was here, far away from his troubles! He sat on the bench in the shade and for the last time, ran through what he had decided upon. The plan was as follows: in the evening he would break the fence at the new-build site and make a hole like he had the year before. He would gather his things, then in the morning, while everyone was asleep, make his escape. He would get to the bus stop, sit and wait. Then onwards to home. He would face the music from his mum first and wait for divine punishment from his father. And pine. He would pine for Volodya so badly that he would wail, that he would blubber into his pillow, that he would roll around on the ceiling, not even just the floor. Why had he done it?!

Yurka buried his face in his palms. Well, why? How would he get on now, completely alone with this unknown, bittersweet feeling? Guilty, lonely, gnawed at half to death by his conscience?

Once the thirst that had been afflicted him for the past hour became unbearable, Yurka stood up from his spot, spat out some thick saliva, and turned back, towards the camp. He plodded along back the exact same way through the forest, consumed by new doubts. Was he really ready for this – to not see him? To burn all bridges, to not leave even the barest chance of making up, without saying goodbye, without saying sorry?

How have I reached the point of coming up with this? How will I have enough courage? How will I look him in the eyes? How can I forgive him for pushing me away? Dozens of these ‘hows’ swarmed around his head: How I humiliated him by doing this! But how nice it was to kiss him!

Yurka plodded ever on and on; it felt like there was no end to the path. The way back usually flew by more quickly, but Yurka was not like everybody else; for him even a hundred metres turned into several kilometres.

Having heard the burbling of a spring, Yurka ventured deeper into the forest. He found it without difficulty and drank. His thirst was slaked, but now he began to get sleepy out of exhaustion.

The memory came unbidden of Volodya’s reaction there, in the lilacs behind the control box, and one phrase rang around in his head – ‘pushed away’, one action played itself out, repeating over and over again – pushing away. On one hand, it was right to push him away, but on the other, it had felt so hurtful that he wanted to blame Volodya for all his troubles. Yurka did not understand at all what was happening with him, he felt lost and all over the place. He did not know what to do until the next day, where to go in the camp, where to hide. However much he wanted to remain in the forest, all the same, the time came to return.

The July sun fell on his skin as it penetrated through the thick canopy of the wild forest trees, scorching and burning disagreeably. Inside too, Yurka was all burning up, aching and itching. He felt like a discarded, dusty old piano which had not been played in a long, long time, used only as a mantlepiece for whatever junk. The strings inside had all gone slack, water had gotten on some of them, and they were going rusty, the pedal which was supposed to draw the notes out longer was broken and fallen down… Now opening the lid – which would only yield with great effort, and creak the whole time – touching the keys, yellowed with age… except, instead of notes that stirred the soul, it would make a terrible cacophony; it had been out of tune for a long time, the hammers were bent out of shape. You would press B and what would come out would be a mix with the flat, the C of the next octave would be totally silent, and if you tried to play across a whole octave at once, a series of screeching and sinking notes would come out.

Music was an undercurrent that ran through his whole friendship with Volodya. It could be heard everywhere: when he saw Volodya on the plaza for the first time, there was the pioneer’s anthem; at their first meeting in the theatre, Pachelbel’s Canon was coming from the radio; at rehearsals, when Masha was playing the piano; during their evening get-togethers at the carousel, it came wafting from the dance floor, and then it was playing from the radio speakers under the willow tree. His feelings for Volodya were constantly in dialogue with music: wherever Volodya was, so too was music, always.

As the heavy gates screeched, Yurka ignored the questions from those on duty, about where he had come from and where he was going, and trudged off in the direction the eyes were looking, Children were running all around. Not a trace of concern about the events with Pcholkin remained on their faces. Just like how not a trace remained of his friendship with Volodya.

It had come to a close the night before, but the season was in full swing. So, might there be a chance of at least making up amicably? Perhaps he did not have to go running headlong to extremes and escape from Volodya? They would never see each other again, after all.

So, there was a plan of escape, but besides his plan, confusion, exhaustion and hunger had appeared. Yurka had been traipsing through the forest for half the day. There was still a long time to wait until dinner, and there was no point going to the canteen – there, he would not even get given a chunk of bread, which was unsurprising; when Zinaida Vasilyevna was on shift, nothing ever trickled its way down to him. Perhaps he could go to the courts, but he did not have the strength to play, nor the desire to watch other play. He could go to some study circle, but he had nothing to do at one. He could go to the river – and bump into Volodya there. No, seeing him then would be the absolute worst thing he could imagine.

But Yurka wanted so badly to see him at exactly that moment.

I don’t understand anything! he whispered to himself, while his feet carried him to the theatre.

In the playground, the girls were launching rubber bands, while the boys were pilfering laundry pegs from somewhere and making them into crossbows. Immersed in himself, Yurka plodded on without noticing anyone around, he just placed a hand behind his back instinctively whenever someone small and nimble ran past too close and too fast. Yurka thought about the theatre. For certain, nobody would be there either, and the piano was there, and Yurka suddenly began to want terribly to sit behind it, open the lid, place his hands on the keys and, holding his breath, at least run his fingers weightlessly over them, to feel them. And perhaps, to play something? What? What would he want to hear right now? Swallowed up thinking about music, Yurka understood that only through his favourite instrument, only like that and no way else could he sort himself out. That nothing else besides music was able to calm him down. That only it could pass through everything, settle his soul, put it in order and coax out from its very depths an understanding of what was happening to him. Only music was capable of calming his soul, making peace with himself, bringing his feelings to reason and explaining everything to him.

In order to make himself touch the piano, Yurka would need to overcome his seemingly undefeatable fear. But what was that sparse, prickling fear compared to this blunt, aching one thar Yurka had been experiencing for the whole previous night and the whole day so far? Whether the fear was strong was unimportant; what was important was that Yurka had been afraid for too long. Like how, with the passage of time, skin becomes coarser and loses its sensation, Yurka’s heart had grown coarse; he almost did not care, something inside him was dulling his emotions. What if he finally managed it?

In the theatre, it was cool and dark. The whole of the premises was illuminated only by the rare sunrays that pierced through the heavy fabric of the blue curtains that had been drawn to. The hall might have been asleep in its peace and quiet, but it was not empty. On the stage, with his nose stuck in a heap of paper and quietly whispering something, Olezhka was stepping from corner to corner.

“You’re not at the river?” asked Yurka, surprisingly and sufficiently loudly.

Olezhka startled and stopped.

“Oh, Yuwa! None of us awe, they’ve come back alweady.”

“Clearly. And where’s… Volodya?” Yurka became anxious – what if he were somewhere nearby?

“He’s busy. Pcholkin’th been mucking about. He made a bomb out of cawbide, he wanted to thend Thanka to the moon. Thanka doeth alwayth go on about how he dweamth of wowking at Baikonuw.[2] But he didn’t get to go, the flight appawatuth blew up.”

“Cawbide?” repeated Yurka, as though winding him up, but Olezhka was not in the slightest offended.

“Well, yeah, cawbide.”

“Oh, carbide!” Yurka guessed his favourite chemical from childhood with difficulty, and thought aloud, “Yeah, that’s right, carbide. That’s what Pcholkin was looking for at the building site! That’s what he was digging around the stones for. And the girls’ hairspray didn’t just go missing! ‘There was still some in the bottom’. And so there was, right in the very bottom, that’s why the bomb went off early. You need an empty can to make one.”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah. It made thuch a loud booom! The girlth flew into the busheth, the boyth flew into the busheth, Thanka bwoke hith nothe, blood wath gushing evewywhewe, the whole playgwound wath flooded. Lena scweamed. Oh, it wath tho thcawy! Volodya took him to the diwector. He’th been thtuck there evew thinthe. But why didn’t you come to the wivew?”

“No reason, I just had some stuff to do.”

“Will you come tomowwow?” asked Olezhka with hope. “But why did you come hewe? Altho thtuff to do?”

“I… I want to play a little piano. Don’t say anything to anyone, alright? I’m not very good, I’m embarrassed. So, I decided to come while no-one was here.”

“Tho that’th it! Well then, you play, I’ll go. I altho have, uh… thtuff to do,” smiled Olezhka as he hopped, skipped and jumped away so quickly that Yurka did not manage to shout a single word after him.

There he was, alone. There it was – the piano. The same one stood in Yurka’s bedroom, with one difference – his piano was covered in dust and whatever else collected on top of it: clothes, toys, books, all the way up to the top so that the lid was not visible, while this one was clean, sparkling, beautiful.

In two steps, Yurka appeared next to the instrument. He turned on the desk lamp that stood on the lid and no sooner laid eyes on the keys, illuminated in that dark yellow light, than he was once again gripped by panic.

This fear is nothing compared to the terror I suffered last night. And this feeling of my own insignificance is nothing compared to the humiliation when Volodya pushed me away, he encouraged himself in a strange, but seemingly successful way. He took another step towards the instrument.

He sat, raised his hands and carefully laid them on the keys. The anticipation of a deep, bassy C ran through his fingers to his chest like an electrical discharge. It might seem such a trifling thing, to play one single sound, but he still had to overcome himself. His heart trembled with joy – he could do it. The C burst forth and reverberated around the hall.

Beside himself with joy and pleasure, Yurka, with his fingers stiff from lack of practice, did not press but rather piled into the keys, sending out different notes, trying to remember and play something simple.

“How did it go?” he reflected. “F-sharp, A-sharp. F or A? Not A, F. F, F-sharp. Or was it G? Argh, how did it go?”

He was trying to recall a melody that he had composed himself. Back then, it had been so simple to him that he could play it with his eyes closed, making his parents and especially his grandma on his mum’s side proud, who dreamed that her grandson would become a pianist. Over the course of a year without music, Yurka had forgotten the melody so completely that now it only came back to him with great difficulty. And another problem – his fingers would not bend.

Yurka began to give them a stretch and tried to remember the melody visually.

“F-sharp, A-sharp of the second octave, F, F-sharp of the third octave. F-flat third, A second, F second, A second. Yes! That’s it! I remember!”

Suddenly all his woes disappeared into the background, all his problems felt irrelevant – Yurka was remembering, Yurka was playing! He was finally playing, he was bending the keys to his will, eliciting wonderful sounds, he felt like he could do anything! He knew that there were no peaks that he could not conquer! His enrapturement took him from this world to another, one cozy, warm, and filled with sound. It was as though Yurka had fired up into space and was floating there, enchanted by the white and yellow flares of the stars. Only, in his cosmos, the stars were sounds.

The door to the theatre hall squeaked quietly, but Yurka did not turn around.

“F-sharp, A-sharp, F, F-sharp. F-flat, A, F, A…” he whispered as he played the same thing over and over, running his hand back and forth between the second and third octaves, refreshing his memory of the motions that he had forgotten.

The sound of furious stomping suddenly began to ring out.

An adult, supposed Yurka, the footsteps are heavy – but he then promptly forgot about it. Wholly absorbed in the music, he no longer got distracted; he did not look around, nor listen to anything besides the music.

The footsteps abruptly stopped, then one-by-one, drowned out by the notes, they began to quietly get closer to him. The unexpected guest’s sneakers barely squeaked at all on the lacquered parquet flooring, their hands were wiping a pair of glasses with a handkerchief, the handkerchief was rustling, but none of that made any difference to Yurka.

F-sharp, A-sharp of the second octave, F, F-sharp of the third octave, F-flat of the third, A of the second, F of the second, A of the second…

“Never do that again,” requested Volodya, his voice trembling.

Yurka froze – had he imagined it? No. It turned out that the stomping had been him. Yurka turned around. Volodya stood in a circle of light by the stage, breathing heavily. Looking at the floor, he sighed, slowly and deeply, and no sooner had he put on his glasses than he became, as though by magic, completely calm.

Here he is, he’s come, pronounced Yurka’s inner voice. He’s come himself. To me, he’s come. Again. And what for?

“What is it, exactly, that I shouldn’t do?” mumbled Yurka quietly.

“Disappearing. You were gone for five hours!”

“Aright,” Yurka could only mumble as he observed Volodya cautiously taking a seat next to him on the wide stool.

“I thought I would kill you when I found you,” he frowned sadly. “I was searching for you, you know. By myself at first, and then I put out some spies to find out for me where you were. If it weren’t for Olezhka, I wouldn’t have known ‘til evening where you were and what was going on with you. I don’t know what I would have done then.”

“It’s good,” Yurka piped up, “that you’re trying to act like nothing’s happened. I want to do the same, but I haven’t managed to.”

His hands trembled, another commotion of thoughts and emotions burst into his head. Yurka placed his fingers back on the keyboard and tried to remember the second part of the melody. It was the only way he could maintain his composure.

F, F-flat. Damn, no, that’s not it. F, F-sharp. Or was it flat? Damn it!

Volodya ignored his jibe and continued:

“I’m not trying to put on an act. On the contrary… That’s really what I came here about. Of course, besides making sure that you’re alive and well…” he cleared his throat, abashed. “I’ve had a lot of time to think about what happened. I was trying to decide the whole night what to do and how to do it. The whole night, and it was all for nothing, I had it all wrong! It didn’t ever cross my mind that it might have been serious. That is, no, of course, it did cross my mind, but I drove the thought off, it was too fantastical. But it turns out that everything’s the other way around. And I panicked. I said totally the wrong thing, not what was needed at all. And not what I really wanted to say. But while I was looking for you,” he emphasised the following, “for five hours, I thought over everything again from the top. Properly, this time. And, well, I came here to tell you what I’ve decided.”

F, F-sharp… Stop.

“What difference does it make? We’re not friends anymore.”

“Of course not. How can we be ‘friends’ after this?”

Yep, we’re not friends. After this, of course, we’re not friends anymore, Yurka had understood this for the whole day so far, but he needed to hear it from Volodya in order to finally lose all hope.

They were silent. Volodya sat with his hands laid on his knees and watched Yurka’s reflection in the lacquered front panel. Yurka himself watched him out of the corner of his eye. He did not want to watch him, but he did so. He did not want to sit next to him – it was too cramped when he was so near – but he did so.

F-sharp, A-sharp, F, F-sharp on the higher octave, F-flat, lower A, F… it sounded uncertain, faltering.

“Yura, are you really not afraid at all?”

“What do I have to be afraid of?”

“Of what we did!”

Of course he was afraid. And yet – though it was incomprehensible and painful, it was somehow more scary and painful to know that by his act he had lost Volodya. Just like that, he had taken it and ruined everything.

“What a child you still are,” sighed Volodya before Yurka could answer. “But really, I envy you.”

Yurka was silent.

“Your recklessness really is something to be envied. You break the rules so easily, you spit on everything and never think about the consequences… I wish I could be like that. To even just once… even just once behave, not how I ‘must’, but how I want to. If only you knew how tiresome it is to constantly be thinking about the properness of your actions! Sometimes I get so fixated on self-control, on what I’m doing, what I’m saying, how I’m behaving myself… that at times it gets to the point of paranoia and panic attacks. In moments like that, I physically cannot judge what’s happening objectively, you understand? And what you did really did seem like a catastrophe to me. But… perhaps it’s not all so bad? Maybe I’m exaggerating?”

Yurka did not understand what Volodya was trying to get at. He was afraid to interrupt this monologue, since at that moment, he was capable only of spilling out all of his emotions and saying whatever was on his mind without thinking it over. He was afraid to embarrass both Volodya and himself again, and to finally destroy what he had already broken. And he did not find anything better than to continue to be silent. All the more so, since he had had a tight lump in his throat for a long time, which precluded him not only from speaking, but from even breathing.

Meanwhile, Volodya was staring with expectation at his reflection in the lacquered panel. His distraught gaze wandered all over Yurka’s face and got caught on his eyes, as though searching for an answer in them. But, not finding it, he cleared his throat again, confused:

“Here’s what I’ve been thinking about, Yur, and I want to know your opinion. There do exist very close friends, who… well, very close, special. For instance, at school and college, I saw guys going round hand in hand, or sitting together in embrace.”

“So what?” Yurka finally swallowed the lump stuck in his throat and began to speak. “Let them go about together like that. They’re close friends, so they can. Not like us.”

“Do you think they kiss?”

“Are you having a laugh? How would I know? I’ve never had any kind of ‘specials’ friends!”

“What about me?” he heard, and it sounded somewhat sorrowful.

“You can go to Masha. I imagine she’s getting sick of waiting.”

“Yur, pack it in. Masha is just someone staying here on holiday, just like everyone else.”

“Just like everyone else…” mimicked Yurka.

At the mention of her name, he began to thrash upon the keyboard to make it louder, to drown out his inner voice, his inner monologue, his reawakening jealousy.

Yurka did not realise that he was playing more and more confidently: F-sharp, A-sharp lower, F, F-sharp higher, F-flat, A, F lower and A. That he was already playing by memory, without looking F, F-sharp, F-flat, A-sharp below and F-sharp once again, A, F and F-sharp above.

He could not tear his gaze away from Volodya’s reflection. He was sitting there, pale, taking shy glances at Yurka, and chewing his lips:

“I don’t want to think of what happened badly. But however I try, I think. Maybe I’m having another fit of panic and paranoia and making mountains out of molehills again, but I’m really scared. Yura, tell me, what do you think about all this?”

About what in particular?”

Volodya shifted even closer, Yurka played even louder.

“You did it because–” Volodya faltered, wiping the sweat from his brow with his palm. “You– you will? That is, you want to be, not just normal, but… special… friends with me?”

Yurka hammered as hard as he could:

F-sharp, A-sharp, F, F-sharp above, F-flat, A from the second, F and A below. F F-sharp higher, F-flat, A-sharp below, F-sharp and A, F and F-sharp above!

“That’s enough! I can’t shout about stuff like this!”

F, F, F, F. Yurka’s whole insides began to tremble.

Volodya grabbed his arm and pulled it away from the keys. Everything froze: the music, his breath, his heart. Yurka turned. Volodya’s face was an inch away from his; once again, he felt his breath on his cheeks. Volodya’s closeness made even his thoughts come to a standstill; goosebumps were flaring up all over his body. His cold fingers trembled as they gripped Yurka’s hands, and behind the lenses of his glasses, his eyes shone feverishly.

Volodya struggled through a gulp and whispered:

“Maybe there’s not actually anything wrong with kissing a… special friend?”

And then it struck Yurka, what Volodya had been trying to say for the past ten minutes. It did not just reach him, it caused a landslide. His heart took the blow, not his head, and Yurka reeled from it.

“Volodya… What are you on about?” he asked the stupidest question in the world, just to convince himself that he had not misheard. “What are you saying, who are you trying to fool – me or yourself?”

“Nobody.”

“Then… you’re sure it’s not some kind of self-deception?”

Volodya shook his head and licked his dry lips.

“No. What about you?”

Barely breathing, Yurka blinked, his eyes bulging with trepidation and rubbed his fingers. His heart thumping in his throat, Yurka squeaked out:

“Yes.” He did not understand the essence of the question, he just wanted to say ‘yes’.

Yurka could not believe what was happening. Volodya himself came closer to him and inclined his head slightly. His pupils dilated, he looked at him excitedly, he held Yurka’s hand. He held his hand! Not like usual, but tenderly and tremulously. He traced his fingers around his hand. His lips were dry, and they smelt nice. Could all this really be possible?

But what was he, Yurka, meant to do – pucker up his lips? By the junction box he had not thought about this. But that was the day before – a long, long time, and not with him. Right then, the main thing for Yurka was to not sigh from delight, nor to be deafened by his heartbeat. He shut his eyes and leant forward. He no longer felt breath on his cheek, but lower down.

But, right then, the porch door of the theatre screeched.

“Blood-red stars are burning on the tracks, the tram ran over a troop of Octoberists….” chanted Sashka from outside.

Yurka sharply turned away, knocking the side of Volodya’s glasses with his brow in his clumsiness, jumped up to his feet and stood back. Volodya’s hands were shaking; they convulsed up and crashed down on the keys. A cacophonous bryammm rang out around the whole hall.

“Ugh, what a thtupid thtowy!” Olezhka replied to Sashka.

The door opened, and over the threshold came stomping all the young kids from the troupe; the older ones were not there yet. Yurka breathed heavily, as though he had just been running, while Volodya sat behind the piano and, batting his eyes around, looked back and forth in confusion between the keyboard and the people coming in.

“You’re all so early today… communal work time isn’t over yet…” he mumbled, his voice gone flat.It’s a good thing that the steps squeak! Yurka laughed hysterically in his head, but decided not to say anything aloud.