#Persenbeug

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Lock on the Danube at the Ybbs-Persenbeug power plant, Austria, 1964. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persenbeug Castle, Austria - colored etching. — Luigi Kasimir (Austrian/Hungarian, 1881-1962)

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danube/Strudengau

I only remembered now that I made a design for the personified Danube/Strudengau a few years ago!

I suppose most of you know the danube, that one big river that runs through Austria.

But let me drop this little information about the Strudengau which "covers" a certain part of the danube in Austria:

Strudengau Valley is a narrow meandering valley of the River Danube. The Strudengau valley used to be one of the most dangerous sections of the Danube for navigation, and it was only the construction of the reservoir of the Ybbs-Persenbeug power station (1957) that solved the problem.

So basically, especially this part of the danube has obviously lots of folklore stories as well, if you look at the folktales from towns of this area. (Idk if my memories are right a large amount of stories are about dr0wning or almost dr0wning.) Also around this area exists the eldest residental castle of Austria. So yeah, I think little Roderich lived there pretty early on at some point while also being f*cking terrified of the water.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

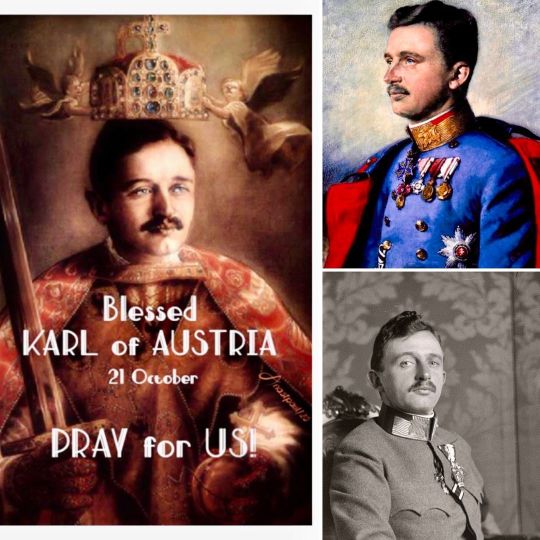

Sel. Karl I.

gefeiert am 21. Oktober

Sel. Karl I. Kaiser von Österreich, König von Ungarn * 17. August 1887 in Persenbeug in Österreich † 1. April 1922 in Quinta do Monte bei Funchal auf Madeira in Portugal

Karl aus dem Hause Österreich wurde am 17. August 1887 auf Schloss Persenbeug in Niederösterreich geboren. Seine Eltern waren Erzherzog Otto und Prinzessin Maria Josepha von Sachsen, Tochter des letzten Königs von Sachsen. Kaiser Franz Joseph I. war Karls Großonkel. Karl wurde bewusst katholisch erzogen und von Kindheit an durch eine Gruppe von Menschen im Gebet begleitet, da eine stigmatisierte Klosterfrau große Leiden und Angriffe gegen ihn prophezeit hatte. Daraus entstand nach dem Tod Karls die Kaiser-Karl-Gebetsliga für den Frieden der Völker - seit 1963 als Gebets-Gemeinschaft kirchlich anerkannt. Schon früh wuchs in Karl eine große Liebe zur heiligsten Eucharistie und zum Herzen Jesu. Alle wichtigen Entscheidungen suchte er im Gebet.

Am 21. Oktober 1911 heiratete er Prinzessin Zita von Bourbon‑Parma. In den gut zehn Jahren ihrer glücklichen und vorbildhaften Ehe wurden dem Paar acht Kinder geschenkt. Noch auf seinem Sterbebett sagte Karl zu Zita: »Ich liebe Dich unendlich!« Am 28. Juni 1914 wurde Karl infolge der Ermordung des Erzherzog Thronfolgers Franz Ferdinand durch einen Attentäter zum Thronfolger Österreich‑Ungarns. Mitten im Ersten Weltkrieg machte der Tod Kaiser Franz Josephs Karl am 21. November 1916 zum Kaiser von Österreich. Am 30. Dezember 1916 wurde er zum Apostolischen König von Ungarn gekrönt. Auch diese Aufgabe sah Karl als Weg der Nachfolge Christi: In der Liebe zu seinen Völkern, in der Sorge um sie und in der Hingabe des Lebens für sie. Die heiligste Pflicht eines Königs - für den Frieden zu sorgen - stellte Karl in den Mittelpunkt seiner Bemühungen während des furchtbaren Krieges. Als einziger aller Verantwortlichen unterstützte er die Friedensbemühungen Papst Benedikts XV. Im Inneren bot er in schwierigster Zeit die Hand zu einer umfangreichen und beispielgebenden Sozialgesetzgebung im Sinne der christlichen Soziallehre. Seine Haltung ermöglichte einen Übergang in die Nachkriegsordnung ohne Bürgerkrieg. Dennoch wurde er aus seiner Heimat verbannt. Auf Wunsch des Papstes, der eine kommunistische Herrschaft in Mitteleuropa befürchtete, versuchte Karl, seine Regierungsverantwortung in Ungarn wieder herzustellen. Zwei Versuche scheiterten, da er unbedingt einen Bürgerkrieg vermeiden wollte.

Karl wurde nach Madeira ins Exil geschickt. Da er seine Aufgabe als einen Auftrag Gottes sah, konnte er sein Amt nicht zurücklegen. Er lebte mit seiner Familie verarmt in einem feuchten Haus. Dort zog sich Karl eine tödliche Erkrankung zu, die er als Opfer für Frieden und Einheit seiner Völker annahm. Karl ertrug sein Leid ohne Klagen, verzieh allen, die an ihm schuldig geworden waren, und starb am 1. April 1922 mit dem Blick auf das Allerheiligste. Motto seines Lebens war, wie er noch am Sterbebett sagte: »Mein ganzes Bestreben ist immer, in allen Dingen den Willen Gottes möglichst klar zu erkennen und zu befolgen, und zwar auf das Vollkommenste«.

#seliger karl der 1#karl der 1#letzter kaiser österreichs#kaiser österreichs#österreich#selig#saint#saints#saint of the day#religion#glaube#römisch katholische kirche#gott#christus#christ#jesus#betrachtung#christianity#gebet#catholicism#theology#christentum

0 notes

Text

Ardagger - Frühstücksnews - Mittwoch, 24.8.2022

Ardagger – Frühstücksnews – Mittwoch, 24.8.2022

Kleiner Tipp heute früh: Wieder einmal eine Wanderung durch die Stillensteinklamm in Richtung Aumühle machen! Sehr geehrte Gemeindebürgerin! Sehr geehrter Gemeindebürger! Seit gestern bereits war die Sperre der B119 aufrecht. Leider haben sich viele nicht an die SPERREN und beschilderten Umleitungen gehalten. Die Autos sind dann durch die Siedlungen BACH und PFAFFENBERG unterwegs gewesen und…

View On WordPress

#Anlagen#China Stromnot#Corona#Energieverbrauch Gemeinde#Erneuerung Turbinen#Impfangebot#Impfrechner#Impfung#Kinderferienspiel#Kraftwerk#KW Ybbs-Persenbeug#Leistungsverbesserung#Meran#Nicht durch Siedlungen#Niedrigwasser#Regen#Südtirol#Schwarzes Meer#Senioren#Sperre B119#Stromverbrauch Gemeinde#Totimpfstoff#Umleitung#Umleitungsstrecken nutzen#VALNEVA#Verbundkraftwerk#Wo brauchen wir den meisten Strom?

0 notes

Photo

Persenbeug.

Luigi Kasimir, (Austro-Hungarian-born, etcher, painter, printmaker and landscape artist 1881 - 1960 born in the now Slovenian town of Pettau)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

October 21 is the feast day of Blessed Charles IV. of Hungary, king

Source of picture: David Kaehling on Pinterest

Life of Blessed Charles IV. of Hungary

He was born on 17 August 1887 in the Castle of Persenbeug, Austria. His deeply religious mother played the most decisive role in his education.

On 21 October 1911 he contracted sacramental marriage, out of love, with the Servant of God, Zita of Bourbon-Parma. They had eight children. Their family life was unique and exemplary in their social circles. Charles and his wife were against the war right from its beginning, however, he strove to fulfil his military service in a Christian way.

Without wishing for it, on 21 November 1916 Charles became king and emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy following the death of four heirs to the throne, as he was preceded by four relatives in the line of succession. This was a truly providential succession. He inherited the burden of a hopeless war, an obsolete political system and constantly worsening internal and exterior problems. The new king had a virtuous and rich personality completed with the enthusiasm of the youth. King Charles was the only supporter of Pope Benedict XV's efforts to bring about peace, thus he made every effort to finish the war.

On 11 November 1918, after World War I, he relinquished every participation in the administration of the Austrian State and on 13 November 1918 he did the same regarding the Hungarian State. However, he was not willing to abdicate; having received his responsibility as king from God, he could not imagine such an action.

After much tribulation, Charles was exiled first to Switzerland, on 24 March 1919, then to the island of Madeira, after his return attempt of 1 November 1921. He never lost his living faith, piety and love for his family, and he offered his sufferings for his peoples. He passed away on 1 April 1922 due to a sudden illness. His tomb in Madeira has become a destination of pilgrims, who remember him as a holy hermit, father of a family and an expiating king.

Source: https://www.mindszentyalapitvany.hu/

Quotes from Blessed Charles IV. of Hungary

Jacek Malczewski: Reconciliation

“I strive always, in all things, to understand, as clearly as possible and follow, the will of God and this, in the most perfect way.”

“Now, we must help each other to get to Heaven.”

#quotes#saints#Blessed Charles IV. of Hungary#king#I strive always in all things to understand#Now we must help each other#Heaven#God#Jesus#Christ#Jesus Christ#Father#Son#Holy Spirit#Holy Trinity#christian religion#faith#hope#love#stress reliever

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The short and very miserable life of Napoleon II, aka the Eaglet, aka Franz, Duke of Reichstadt: PART THREE

So there’s a lot of controversy over the exact nature of Franz and Sophie’s friendship. At the time, it was was rumored they became lovers. Satirical prints of the two were even published. But I’ve browsed a few recent-ish books about the Habsburgs, and they don’t seem to think the idea of a Franz/Sophie affair holds a lot of water. However, Aubry thinks it’s possible— even probable.

He took refuge in his tenderness for his young aunt, Sophie. She was still the woman whom he preferred. Perhaps she was his only love, the one to whom he owed his first embrace and the one who best satisfied him. She had been at first nothing but an elder sister. In his empty boyhood she had given him the only warmth of friendship he had known. Become a man he had asked for more, and Sophie consented, it is said.

They saw each other everyday at the Hofburg, in the little salon belonging to the Archduchess. It was always towards evening when he was tired from his work or his horseback rides and she relaxed from duties of the court. Oftentimes they would be alone, and they would take their tea by lamplight, reading aloud or talking over the happenings of the day. Reichstadt gave Sophie his full confidence. She knew his anxieties and his bitternesses and she gave him back his courage. She would place her fingers on his forehead, and stoke his hair, which shone like silk in the dim light. He would look back at her with quiet happiness, and she would smile back at him as she sat there in a low-cut gown, the coils of her hair caught up in a veil of white lace, and around her throat a ribbon of black velvet with a pendant, which was a miniature of her father, King Maximilian of Bavaria. [Aubry pg 215]

Aubry paints a compelling picture of Sophie’s restless, clear-eyed youth, intelligence, strong will, and free, simple, natural ways, which stood out like a star against the stultifying pomposity of the Habsburg court. Not surprisingly, she hated her husband, a coarse blockhead mainly obsessed with hunting. She spent every hour she could with Franz, driving in the Prater, breakfasting together, or walking in the garden, often accompanied by Sophie’s son Franz Joseph (Sissi’s future husband). Like his father, Franz loved children and was great with them. Add his intelligence, passion, and incredible good looks, I would not blame Sophie one bit if she’d had an affair with Franz.

Aubry also points out that at Schoenbrunn, Franz’s quarters were directly above Sophie’s, and connected through “a little staircase unknown to any chamberlain.” They also spent many afternoons completely alone.

They would venture through the Tyrolian garden to the limits of the vast wooded park and on out into that smiling countryside where vineclad hills gently rise above meadows, patches of woods and cultivated fields. There they spent the most beautiful hours in their lives, talking less of the future and of glory, we may be sure, than of the present and of love. No definite information as to these meetings have survived. All that is known from authentic documents is that they were frequent in the summer of 1831. Nor is there any trace, either, in spite of careful searches, of a correspondence between Reichstadt and Sophie. The Archduchess died at an advanced age, after a checkered career. She must have taken care to leave nothing behind her. The archives of the Hofburg show only the mother, and the princess interested in questions of State. [Aubry pg 217]

Aubry then considers the contention that Sophie’s son Maximilian was actually fathered by Franz. Aubry thinks it’s at least possible, but I don’t think it is. Just look at pictures of the guy— he’s 100% Habsburg. He looks exactly like Franz Karl. The Bonaparte seed is strong; if Napoleon was Maximilian’s grandfather, you’d be able to see it somewhere. But you can’t.

Anyway, after the golden summer of 1831— probably the second happiest period of Franz’s life, after his childhood—it was all downhill from there. Very, very downhill.

Franz’s lung issues came back with a vengeance. It didn’t help his main doctor at this point was a foppish Italian obsessed with liver ailments— he thought all of Franz’s problems stemmed from— what else?— the liver. That winter Franz became major of an infantry regiment stationed in Vienna, and distinguished himself drilling his men to perfection. Which is kind of sad, really; but that’s all he was allowed to do, be a parade-ground soldier who never got his uniform dirty. He ate little, and slept less, so eager to show that he could be a real soldier, like his father. His health plummeted, and he contracted a catarrhal fever. The Imperial family gathered around Franz— except for Marie Louise, who was too busy back with her little court at Parma, “nibbling bonbons at the Opera.” Of course she protested her “cruel anxiety” about Franz’s welfare, but she wasn’t about to go anywhere. After all, she couldn’t think of endangering her own “precious health” journeying to Vienna.

Reichstadt must have felt the desertion keenly, but he voiced no bitterness. He had grown accustomed to suffering in silence, and those who forgot him, he tried to forget. [Aubry pg. 224.]

So, once again, Marie Louise disappointed her son. But Franz had Sophie; and he also had Prokesch back, who had happily returned after Metternich forced him to go to Bologna (Metternich didn’t trust Prokesch, and did his best to keep the two friends apart). The two men now knew the full stranglehold that Metternich had on the monarchy. Franz would not even be able to take a single trip away, not even for his health. It was do or die.

The two concocted a plan, and it was a decent one. Once he’d recovered, at winter in Vienna, he would be able to slip away from the secret police, as he had when romancing Naudine Karolyi. “He and Prokesch would reach Styria or the Tyrol in disguise and from there, taking advantage of connections which the major would try to establish in a preliminary reconnoissance, they would reach the Papal States where the Duke would ask asylum of the Pope.” Letizia Bonaparte and Lucien, who lived there comfortably, the Pope deferring to them, had money and connections. “Sheltered by the head of the Church and his grandmother, on a soil not only neutral but sacred, he would be free to complete his novitiate for the throne. Prokesch foresaw that it would be not a very long one. He predicted the fall of Louis-Phillippe in two or three years at most, and after a period of anarchy, the return of Napoleon II by agreement between France and the Powers.” [Aubry pg 232]

Alas! Metternich caught wind of the scheme, and banished Prokesch to Rome in January of 1832. What a blow this was! But the major agreed he could use the circumstances to do the agreed reconnoissance and meet in secret with Madame Mère. The two men parted with great emotion.

But this is the last time they would ever see each other. By the next summer, Franz would be dead.

* * *

After the departure of one of his only friends in the world, depression overwhelmed Franz again. It didn’t help when he received a letter from Napoleon’s last valet, Marchand, who had been trying for years to contact Franz about a few items of “sentimental value” that Napoleon had left for his son. But there was a note from Metternich on the letter, that briskly said “no attention could be paid to Marchand’s request.”

And that was it. Franz knew had no recourse. He wouldn’t even be able to get his father’s coffee service. How petty, how disgusting, how mean Metternich was! Napoleon had been dead for over a decade; why couldn’t he have one single sentimental item left to him in his will? Was it that important? That much of a matter of importance to the State, to the bloody Holy Alliance, that he couldn’t hold the same coffee cup that his father held?

And bitterness ate away at him. He was only 21, but he felt so old. He hated humanity. He hated himself. He wondered why he was still alive. Perhaps he would have been better off if he had died as a child. He had expected so much of the future— but there was nothing but the coldness and emptiness of an eternal prison.

Despair ate at him like a worm. And he grew sick. And sicker. He coughed and sweated and grew weaker by the day. His doctor’s liver medicines did nothing, and then bleeding did less, and Metternich kept refusing to see Franz moved to a warmer climate.

The Chancellor was pleased by the turn of events, of course. “He sent world to all the embassies, and Marshal Maison was asked to inform his government, that ‘the condition of the Duke of Reichstadt was so serious that his mother has been informed.’” [Aubry pg 244]

A pregnant Sophie, at last returned from her tour of Hungary, did her best to nurse him. “She sat down at his bedside and hushed him whenever he tried to speak. She would read aloud to him and it was she thereafter who gave him his medicines and guarded his door from any importunate intrusion.” [Aubry pg 245]

Franz still worsened. The Emperor was not present; he was detained in Trieste, and when he returned to Austria, he avoided Vienna, staying at the summer castle of Persenbeug, along with the “ninny” Ferdinand and the blockhead Franz Karl, while Francis’s wife claimed that seeing his dying grandson would have a deleterious effect on his health. Count Dietrichstein also decided to leave, on the excuse of his daughter’s confinement. Aubry says:

He must have known that Reichstadt was lost. Could he just have been an indifferent soul underneath his courtesy and his outward expressions of affectionate anxiety? He may have been. Count Maurice Dietrichstein was born a sensitive man and an artist, but life at Court had dried him up, undoubtedly leaving him in the end with the heart of a chamberlain. He forgot his former pupil at his daughter’s bedside and allowed him to die without a word of friendship. [Aubry pg 250]

For Franz, it was a slow, agonizing death march, punctuated by an an abcess in his lungs rupturing— and a final communion taken with Sophie at his side, in what Aubry compares to a “mystic marriage.” Louise arrived at last, after dithering over her departure, claiming “slight indispositions” as a reason for not leaving sooner, and then coming to Vienna via “easy stages” over the course of a fortnight. Of course, when she saw how badly off her son was, emaciated and hacking up blood, she began to cry.

There with that spectre of the hollow eyes before her she may perhaps have understood at last the true identity of that youth whom she had neglected for two years, and how guilty she had been all along toward him. She alone could have protected her child against Metternich’s policy and against himself. She could have saved him from those years of moral anguish and that tragic solitude which had ruined his health sooner and even more than any disease. That in her weakness she had lost him a throne might be excused, but however cowardly as an Empress, she might have shown herself a good mother. Vienna was her true place but she had preferred Parma with its ease, deserting the son of the greatest man in her age to sate her voluptuousness in the arms of her lover, nibble bonbons and preside over well-served dinners. [Aubry pgs 252-252]

Of course, Metternich made sure to look in on Franz while he was dying.

Through a half-open door however the Chancellor was allowed to see the patient in his bed. He gazed for a moment, then turned and walked away without a tremor, without a word of sympathy for the mother and doubtless without any remorse. [Aubry pg 255]

Franz knew he would die. “Must I end so young,” he said, “A life that is useless and without a name? Ma naissance et ma mort, voilà toute mon histoire. Entre mon berceau et ma tombe, il y a un grand zéro.” He did not quite say that on his deathbed, but it was close. Very, very close.

It took monumental efforts to keep Franz alive at this point. He was a barely breathing corpse. He could not swallow food; his throat had swollen up; his coughing seem to tear his body apart; and he could barely sup barley-water and milk. He had even been given mother’s milk at one point. His legs were swollen, and he was cold as ice. Deprived of his dearest friend Prokesch, who was meeting with Letizia and Lucien in Rome, his fellow captains in his regiment stood by his bedside.

The end came on the morning of July 21st— a thunderstorm brewed in the air, the air damp and thick and charged. He cried out— “death! I want nothing but death!” — and then— “Harness the horses! I must go to meet my father! I must embrace him once more!”

Then he whispered: “How I am suffering! When will this sad existence end?” [Aubry pg 260]

At last, he called, gasping, sweating, for his mother. (Sophie, still recovering from childbirth, was left to sleep, something which she never forgot.) Louise was brought in at the last minute, and managed to faint dead away in the middle of the room, completely prostrate on the floor. I’m imagining the priest having to step over her for his last rites, but apparently she managed to get to her knees by the bed just in time for Franz to look at her. That, one instant, and then he stopped breathing altogether.

Franz’s grandfather, back in Persenbeug, away from any inconveniently dead grandsons, called Franz’s death a possible blessing for Europe.

As for Sophie, once the news was broken “delicately” to her…

…she lost consciousness for several hours and the attack was followed by a high fever. Her milk dried up. For several days her life was despaired of. She gradually recovered. Those who knew her thereafter no longer found the gay and simple Archduchess. All the gentleness seemed to have left her. There was a sting in everything she said. The truth was that her youth had died with Reichstadt. She was to have intrigues, love affairs, ambitions, cares of State. But she had changed in spirit, or rather she had attained in a few days the mood of her maturity, with, in her heart’s depth, a regret and a bitterness which would endure until her death, five years after the disaster of her son Maximilian. [Aubry pg 265]

* * *

And so ends my recap of Aubry’s King of Rome. Ugh, this could have been more depressing!? Anyway, I’ll write an epilogue soon explaining what happened to everyone after Franz’s death.

Part One

Part Two

#napoleon II#sophie of bavaria#marie louise#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#l'aiglon#eaglet#duke of reichstadt#octave aubry#francis II#habsburgs#count dietrichstein#archduchess sophie#prokesch#metternich#depressing stuff

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Parish Church “Maria Königin aller Heiligen” (1985) in Persenbeug, Austria, by Josef Patzelt

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

01-05 AUSTRIA - CIRCA 1911: Persenbeug Palace. Lower Austria. Hand-colored lantern slide. 1911. (Photo by Oesterreichsches Volkshochschularchiv/Imagno/Getty Images) #persenbeug http://dlvr.it/Q8y30V

0 notes

Video

Cessna CE 208 Amphibian „Caravan“ von Max Kroner Über Flickr: ©Air-Sea-Spotter.eu - Alle Rechte vorbehalten

#Cessna CE 208 Amphibian Caravan#Cessna#CE#Amphibian#Wasserflugzeug#Fahrzeug#Flughafen#Flugzeug#Aircraft#Red Bull#Flying Bulls#Turboprop#Outdoor#Wasser#Donau#Persenbeug#Ybbs an der Donau

0 notes

Photo

A day late posting. Charles of Austria was born August 17, 1887, in the Castle of Persenbeug in the region of Lower Austria. His parents were the Archduke Otto and Princess Maria Josephine of Saxony, daughter of the last King of Saxony. Emperor Francis Joseph I was Charles' Great Uncle. CHARLES OF AUSTRIA (1887-1922) Charles of Austria was born August 17, 1887, in the Castle of Persenbeug in the region of Lower Austria. His parents were the Archduke Otto and Princess Maria Josephine of Saxony, daughter of the last King of Saxony. Emperor Francis Joseph I was Charles' Great Uncle. Charles was given an expressly Catholic education and the prayers of a group of persons accompanied him from childhood, since a stigmatic nun prophesied that he would undergo great suffering and attacks would be made against him. That is how the “League of prayer of the Emperor Charles for the peace of the peoples” originated after his death. In 1963 it became a prayer community ecclesiastically recognized. A deep devotion to the Holy Eucharist and to the Sacred Heart of Jesus began to grow in Charles. He turned to prayer before making any important decisions. On the 21st of October, 1911, he married Princess Zita of Bourbon and Parma. The couple was blessed with eight children during the ten years of their happy and exemplary married life. Charles still declared to Zita on his deathbed: “I'll love you forever.” Charles became heir to the throne of the Austro‑Hungarian Empire on June 28, 1914, following the assassination of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand. World War I was underway and with the death of the Emperor Francis Joseph, on November 21, 1916 Charles became Emperor of Austria. On December 30th he was crowned apostolic King of Hungary. Charles envisaged this office also as a way to follow Christ: in the love and care of the peoples entrusted to him, and in dedicating his life to them. He placed the most sacred duty of a king - a commitment to peace - at the center of his preoccupations during the course of the terrible war. He was the only one among political leaders to support Benedict XV's peace efforts. https://www.instagram.com/p/CkA3bf6O4Dz/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Wir sind heute frühmorgens bereits Richtung Krems los gestartet und haben bei Ybbs die Donau gequert. Entlang des Radweges gibt es hier einige schöne Raststätten, Cafes und Bistro. Die meisten waren uns davon aufgrund der Urlaubssaison zu überfüllt. So sind wir weiter nach Ybbs - Persenbeug gefahren und im Barbaras Lindencafe am Ortsplatz im Garten gelandet. Das Beste, was uns passieren konnte! Ein klassisches, gutes Frühstück, schön angerichtet mit weichem Ei, Cafe Latte & 1/4 🍊Saft um 10,90€ Fazit: es gibt sie noch, die Adressen, wo man zu vernünftigen Preisen einkehren kann. #privatetasteontour #privatetaste #privatetastebyanita #privatetastebyanitamoser #frühstücken #brunch #öisst (hier: PrivateTaste) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgEXoT1jtdV/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#privatetasteontour#privatetaste#privatetastebyanita#privatetastebyanitamoser#frühstücken#brunch#öisst

0 notes

Link

Music by indie rock artist, Karl Bierbaumer on the Music Discovery XO Auditions, Persenbeug-Gottsdorf, Austria. Listen free, watch videos, share & VOT

0 notes

Text

Saint of the Day ~ October 21

Saint of the Day ~ October 21

BLESSED CHARLES of AUSTRIA (1887-1922), holy man Today, the Church honors Blessed Charles of Austria, who, as the country’s emperor and apostolic king of Hungary, lived his faith as leader of his people, always drawn to a strong sense of Christian social justice. Charles was born of royal parents on August 17, 1887, in the Castle of Persenbeug in the region of Lower Austria. He was given an…

View On WordPress

0 notes