#Particle Accelerators

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

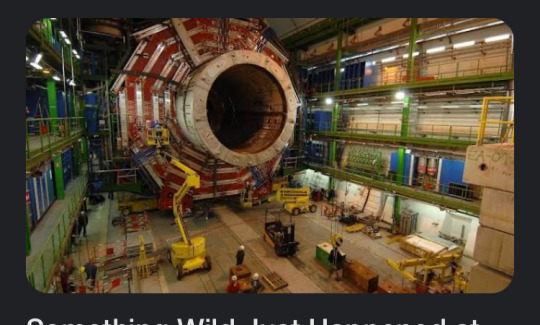

Physicists Found the Ghost Haunting the World’s Most Famous Particle Accelerator

An invisible force has long eluded detection within CERN’s halls—until now.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reminds me that I drove over SLAC — the Stanford Linear Accelerator — last weekend. It’s a narrow but two-mile long building in the hills of Palo Alto, and highway 280 passes over & across it.

I’ve always thought it wonderful that something so exotic as a miles-long tube of vacuum ringed by magnets through which beams of subatomic particles fly at close to lightspeed rests in a bucolic setting near fields of cows. And that streams of cars traveling at only 70 miles per hour almost intersect those beams.

My latest cartoon for New Scientist

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Conceptual Design for a Neutrino Power Transmission System

Overview

Neutrinos could potentially be used to send electricity over long distances without the need for high-voltage direct current (HVDC) lines. Neutrinos have the unique property of being able to pass through matter without interacting with it, which makes them ideal for transmitting energy over long distances without significant energy loss. This property allows neutrinos to be used as a medium for energy transmission, potentially replacing HVDC lines in certain applications.

So the goal is to create a neutrino-based power transmission system capable of sending and receiving a beam of neutrinos that carry a few MW of power across a short distance. This setup will include a neutrino beam generator (transmitter), a travel medium, and a neutrino detector (receiver) that can convert the neutrinos' kinetic energy into electrical power.

1. Neutrino Beam Generator (Transmitter)

Particle Accelerator: At the heart of the neutrino beam generator will be a particle accelerator. This accelerator will increase the energy of protons before colliding them with a target to produce pions and kaons, which then decay into neutrinos. A compact linear accelerator or a small synchrotron could be used for this purpose.

Target Material: The protons accelerated by the particle accelerator will strike a dense material target (like tungsten or graphite) to create a shower of pions and kaons.

Decay Tunnel: After production, these particles will travel through a decay tunnel where they decay into neutrinos. This tunnel needs to be under vacuum or filled with inert gas to minimize interactions before decay.

Focusing Horns: Magnetic horns will be used to focus the charged pions and kaons before they decay, enhancing the neutrino beam's intensity and directionality.

Energy and Beam Intensity: To achieve a few MW of power, the system will need to operate at several gigaelectronvolts (GeV) with a proton beam current of a few tens of milliamperes.

2. Travel Medium

Direct Line of Sight: Neutrinos can travel through the Earth with negligible absorption or scattering, but for initial tests, a direct line of sight through air or vacuum could be used to simplify detection.

Distance: The initial setup could span a distance from a few hundred meters to a few kilometers, allowing for measurable neutrino interactions without requiring excessively large infrastructure.

3. Neutrino Detector (Receiver)

Detector Medium: A large volume of water or liquid scintillator will be used as the detecting medium. Neutrinos interacting with the medium produce a charged particle that can then be detected via Cherenkov radiation or scintillation light.

Photodetectors: Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) or Silicon Photomultipliers (SiPMs) will be arranged around the detector medium to capture the light signals generated by neutrino interactions.

Energy Conversion: The kinetic energy of particles produced in neutrino interactions will be converted into heat. This heat can then be used in a traditional heat-to-electricity conversion system (like a steam turbine or thermoelectric generators).

Shielding and Background Reduction: To improve the signal-to-noise ratio, the detector will be shielded with lead or water to reduce background radiation. A veto system may also be employed to distinguish neutrino events from other particle interactions.

4. Control and Data Acquisition

Synchronization: Precise timing and synchronization between the accelerator and the detector will be crucial to identify and correlate neutrino events.

Data Acquisition System: A high-speed data acquisition system will collect data from the photodetectors, processing and recording the timing and energy of detected events.

Hypothetical Power Calculation

To estimate the power that could be transmitted:

Neutrino Flux: Let the number of neutrinos per second be ( N_\nu ), and each neutrino carries an average energy ( E_\nu ).

Neutrino Interaction Rate: Only a tiny fraction (( \sigma )) of neutrinos will interact with the detector material. For a detector with ( N_d ) target nuclei, the interaction rate ( R ) is ( R = N_\nu \sigma N_d ).

Power Conversion: If each interaction deposits energy ( E_d ) into the detector, the power ( P ) is ( P = R \times E_d ).

For a beam of ( 10^{15} ) neutrinos per second (a feasible rate for a small accelerator) each with ( E_\nu = 1 ) GeV, and assuming an interaction cross-section ( \sigma \approx 10^{-38} ) cm(^2), a detector with ( N_d = 10^{30} ) (corresponding to about 10 kilotons of water), and ( E_d = E_\nu ) (for simplicity in this hypothetical scenario), the power is:

[ P = 10

^{15} \times 10^{-38} \times 10^{30} \times 1 \text{ GeV} ]

[ P = 10^{7} \times 1 \text{ GeV} ]

Converting GeV to joules (1 GeV ≈ (1.6 \times 10^{-10}) J):

[ P = 10^{7} \times 1.6 \times 10^{-10} \text{ J/s} ]

[ P = 1.6 \text{ MW} ]

Thus, under these very optimistic and idealized conditions, the setup could theoretically transmit about 1.6 MW of power. However, this is an idealized maximum, and actual performance would likely be significantly lower due to various inefficiencies and losses.

Detailed Steps to Implement the Conceptual Design

Step 1: Building the Neutrino Beam Generator

Accelerator Design:

Choose a compact linear accelerator or a small synchrotron capable of accelerating protons to the required energy (several GeV).

Design the beamline with the necessary magnetic optics to focus and direct the proton beam.

Target Station:

Construct a target station with a high-density tungsten or graphite target to maximize pion and kaon production.

Implement a cooling system to manage the heat generated by the high-intensity proton beam.

Decay Tunnel:

Design and construct a decay tunnel, optimizing its length to maximize the decay of pions and kaons into neutrinos.

Include magnetic focusing horns to shape and direct the emerging neutrino beam.

Safety and Controls:

Develop a control system to synchronize the operation of the accelerator and monitor the beam's properties.

Implement safety systems to manage radiation and operational risks.

Step 2: Setting Up the Neutrino Detector

Detector Medium:

Select a large volume of water or liquid scintillator. For a few MW of transmitted power, consider a detector size of around 10 kilotons, similar to large neutrino detectors in current experiments.

Place the detector underground or in a well-shielded facility to reduce cosmic ray backgrounds.

Photodetectors:

Install thousands of photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) or Silicon Photomultipliers (SiPMs) around the detector to capture light from neutrino interactions.

Optimize the arrangement of these sensors to maximize coverage and detection efficiency.

Energy Conversion System:

Design a system to convert the kinetic energy from particle reactions into heat.

Couple this heat to a heat exchanger and use it to drive a turbine or other electricity-generating device.

Data Acquisition and Processing:

Implement a high-speed data acquisition system to record signals from the photodetectors.

Develop software to analyze the timing and energy of events, distinguishing neutrino interactions from background noise.

Step 3: Integration and Testing

Integration:

Carefully align the neutrino beam generator with the detector over the chosen distance.

Test the proton beam operation, target interaction, and neutrino production phases individually before full operation.

Calibration:

Use calibration sources and possibly a low-intensity neutrino source to calibrate the detector.

Adjust the photodetector and data acquisition settings to optimize signal detection and reduce noise.

Full System Test:

Begin with low-intensity beams to ensure the system's stability and operational safety.

Gradually increase the beam intensity, monitoring the detector's response and the power output.

Operational Refinement:

Refine the beam focusing and detector sensitivity based on initial tests.

Implement iterative improvements to increase the system's efficiency and power output.

Challenges and Feasibility

While the theoretical framework suggests that a few MW of power could be transmitted via neutrinos, several significant challenges would need to be addressed to make such a system feasible:

Interaction Rates: The extremely low interaction rate of neutrinos means that even with a high-intensity beam and a large detector, only a tiny fraction of the neutrinos will be detected and contribute to power generation.

Technological Limits: The current state of particle accelerator and neutrino detection technology would make it difficult to achieve the necessary beam intensity and detection efficiency required for MW-level power transmission.

Cost and Infrastructure: The cost of building and operating such a system would be enormous, likely many orders of magnitude greater than existing power transmission systems.

Efficiency: Converting the kinetic energy of particles produced in neutrino interactions to electrical energy with high efficiency is a significant technical challenge.

Scalability: Scaling this setup to practical applications would require even more significant advancements in technology and reductions

in cost.

Detailed Analysis of Efficiency and Cost

Even in an ideal scenario where technological barriers are overcome, the efficiency of converting neutrino interactions into usable power is a critical factor. Here’s a deeper look into the efficiency and cost aspects:

Efficiency Analysis

Neutrino Detection Efficiency: Current neutrino detectors have very low efficiency due to the small cross-section of neutrino interactions. To improve this, advanced materials or innovative detection techniques would be required. For instance, using superfluid helium or advanced photodetectors could potentially increase interaction rates and energy conversion efficiency.

Energy Conversion Efficiency: The process of converting the kinetic energy from particle reactions into usable electrical energy currently has many stages of loss. Thermal systems, like steam turbines, typically have efficiencies of 30-40%. To enhance this, direct energy conversion methods, such as thermoelectric generators or direct kinetic-to-electric conversion, need development but are still far from achieving high efficiency at the scale required.

Overall System Efficiency: Combining the neutrino interaction efficiency and the energy conversion efficiency, the overall system efficiency could be extremely low. For neutrino power transmission to be comparable to current technologies, these efficiencies need to be boosted by several orders of magnitude.

Cost Considerations

Capital Costs: The initial costs include building the particle accelerator, target station, decay tunnel, focusing system, and the neutrino detector. Each of these components is expensive, with costs potentially running into billions of dollars for a setup that could aim to transmit a few MW of power.

Operational Costs: The operational costs include the energy to run the accelerator and the maintenance of the entire system. Given the high-energy particles involved and the precision technology required, these costs would be significantly higher than those for traditional power transmission methods.

Cost-Effectiveness: To determine the cost-effectiveness, compare the total cost per unit of power transmitted with that of HVDC systems. Currently, HVDC transmission costs are about $1-2 million per mile for the infrastructure, plus additional costs for power losses over distance. In contrast, a neutrino-based system would have negligible losses over distance, but the infrastructure costs would dwarf any current system.

Potential Improvements and Research Directions

To move from a theoretical concept to a more practical proposition, several areas of research and development could be pursued:

Advanced Materials: Research into new materials with higher sensitivity to neutrino interactions could improve detection rates. Nanomaterials or quantum dots might offer new pathways to detect and harness the energy from neutrino interactions more efficiently.

Accelerator Technology: Developing more compact and efficient accelerators would reduce the initial and operational costs of generating high-intensity neutrino beams. Using new acceleration techniques, such as plasma wakefield acceleration, could significantly decrease the size and cost of accelerators.

Detector Technology: Improvements in photodetector efficiency and the development of new scintillating materials could enhance the signal-to-noise ratio in neutrino detectors. High-temperature superconductors could also be used to improve the efficiency of magnetic horns and focusing devices.

Energy Conversion Methods: Exploring direct conversion methods, where the kinetic energy of particles from neutrino interactions is directly converted into electricity, could bypass the inefficiencies of thermal conversion systems. Research into piezoelectric materials or other direct conversion technologies could be key.

Conceptual Experiment to Demonstrate Viability

To demonstrate the viability of neutrino power transmission, even at a very small scale, a conceptual experiment could be set up as follows:

Experimental Setup

Small-Scale Accelerator: Use a small-scale proton accelerator to generate a neutrino beam. For experimental purposes, this could be a linear accelerator used in many research labs, capable of accelerating protons to a few hundred MeV.

Miniature Target and Decay Tunnel: Design a compact target and a short decay tunnel to produce and focus neutrinos. This setup will test the beam production and initial focusing systems.

Small Detector: Construct a small-scale neutrino detector, possibly using a few tons of liquid scintillator or water, equipped with sensitive photodetectors. This detector will test the feasibility of detecting focused neutrino beams at short distances.

Measurement and Analysis: Measure the rate of neutrino interactions and the energy deposited in the detector. Compare this to the expected values based on the beam properties and detector design.

Steps to Conduct the Experiment

Calibrate the Accelerator and Beamline: Ensure the proton beam is correctly tuned and the target is accurately positioned to maximize pion and kaon production.

Operate the Decay Tunnel and Focusing System: Run tests to optimize the magnetic focusing horns and maximize the neutrino beam coherence.

Run the Detector: Collect data from the neutrino interactions, focusing on capturing the rare events and distinguishing them from background noise.

Data Analysis: Analyze the collected data to determine the neutrino flux and interaction rate, and compare these to

theoretical predictions to validate the setup.

Optimization: Based on initial results, adjust the beam energy, focusing systems, and detector configurations to improve interaction rates and signal clarity.

Example Calculation for a Proof-of-Concept Experiment

To put the above experimental setup into a more quantitative framework, here's a simplified example calculation:

Assumptions and Parameters

Proton Beam Energy: 500 MeV (which is within the capability of many smaller particle accelerators).

Number of Protons per Second ((N_p)): (1 \times 10^{13}) protons/second (a relatively low intensity to ensure safe operations for a proof-of-concept).

Target Efficiency: Assume 20% of the protons produce pions or kaons that decay into neutrinos.

Neutrino Energy ((E_\nu)): Approximately 30% of the pion or kaon energy, so around 150 MeV per neutrino.

Distance to Detector ((D)): 100 meters (to stay within a compact experimental facility).

Detector Mass: 10 tons of water (equivalent to (10^4) kg, or about (6 \times 10^{31}) protons assuming 2 protons per water molecule).

Neutrino Interaction Cross-Section ((\sigma)): Approximately (10^{-38} , \text{m}^2) (typical for neutrinos at this energy).

Neutrino Detection Efficiency: Assume 50% due to detector design and quantum efficiency of photodetectors.

Neutrino Production

Pions/Kaons Produced: [ N_{\text{pions/kaons}} = N_p \times 0.2 = 2 \times 10^{12} \text{ per second} ]

Neutrinos Produced: [ N_\nu = N_{\text{pions/kaons}} = 2 \times 10^{12} \text{ neutrinos per second} ]

Neutrino Flux at the Detector

Given the neutrinos spread out over a sphere: [ \text{Flux} = \frac{N_\nu}{4 \pi D^2} = \frac{2 \times 10^{12}}{4 \pi (100)^2} , \text{neutrinos/m}^2/\text{s} ] [ \text{Flux} \approx 1.6 \times 10^7 , \text{neutrinos/m}^2/\text{s} ]

Expected Interaction Rate in the Detector

Number of Target Nuclei ((N_t)) in the detector: [ N_t = 6 \times 10^{31} ]

Interactions per Second: [ R = \text{Flux} \times N_t \times \sigma \times \text{Efficiency} ] [ R = 1.6 \times 10^7 \times 6 \times 10^{31} \times 10^{-38} \times 0.5 ] [ R \approx 48 , \text{interactions/second} ]

Energy Deposited

Energy per Interaction: Assuming each neutrino interaction deposits roughly its full energy (150 MeV, or (150 \times 1.6 \times 10^{-13}) J): [ E_d = 150 \times 1.6 \times 10^{-13} , \text{J} = 2.4 \times 10^{-11} , \text{J} ]

Total Power: [ P = R \times E_d ] [ P = 48 \times 2.4 \times 10^{-11} , \text{J/s} ] [ P \approx 1.15 \times 10^{-9} , \text{W} ]

So, the power deposited in the detector from neutrino interactions would be about (1.15 \times 10^{-9}) watts.

Challenges and Improvements for Scaling Up

While the proof-of-concept might demonstrate the fundamental principles, scaling this up to transmit even a single watt of power, let alone megawatts, highlights the significant challenges:

Increased Beam Intensity: To increase the power output, the intensity of the proton beam and the efficiency of pion/kaon production must be dramatically increased. For high power levels, this would require a much higher energy and intensity accelerator, larger and more efficient targets, and more sophisticated focusing systems.

Larger Detector: The detector would need to be massively scaled

up in size. To detect enough neutrinos to convert to a practical amount of power, we're talking about scaling from a 10-ton detector to potentially tens of thousands of tons or more, similar to the scale of detectors used in major neutrino experiments like Super-Kamiokande in Japan.

Improved Detection and Conversion Efficiency: To realistically convert the interactions into usable power, the efficiency of both the detection and the subsequent energy conversion process needs to be near-perfect, which is far beyond current capabilities.

Steps to Scale Up the Experiment

To transition from the initial proof-of-concept to a more substantial demonstration and eventually to a practical application, several steps and advancements are necessary:

Enhanced Accelerator Performance:

Upgrade to Higher Energies: Move from a 500 MeV system to several GeV or even higher, as higher energy neutrinos can penetrate further and have a higher probability of interaction.

Increase Beam Current: Amplify the proton beam current to increase the number of neutrinos generated, aiming for a beam power in the range of hundreds of megawatts to gigawatts.

Optimized Target and Decay Tunnel:

Target Material and Design: Use advanced materials that can withstand the intense bombardment of protons and optimize the geometry for maximum pion and kaon production.

Magnetic Focusing: Refine the magnetic horns and other focusing devices to maximize the collimation and directionality of the produced neutrinos, minimizing spread and loss.

Massive Scale Detector:

Detector Volume: Scale the detector up to the kiloton or even megaton range, using water, liquid scintillator, or other materials that provide a large number of target nuclei.

Advanced Photodetectors: Deploy tens of thousands of high-efficiency photodetectors to capture as much of the light from interactions as possible.

High-Efficiency Energy Conversion:

Direct Conversion Technologies: Research and develop technologies that can convert the kinetic energy from particle reactions directly into electrical energy with minimal loss.

Thermodynamic Cycles: If using heat conversion, optimize the thermodynamic cycle (such as using supercritical CO2 turbines) to maximize the efficiency of converting heat into electricity.

Integration and Synchronization:

Data Acquisition and Processing: Handle the vast amounts of data from the detector with real-time processing to identify and quantify neutrino events.

Synchronization: Ensure precise timing between the neutrino production at the accelerator and the detection events to accurately attribute interactions to the beam.

Realistic Projections and Innovations Required

Considering the stark difference between the power levels in the initial experiment and the target power levels, let's outline the innovations and breakthroughs needed:

Neutrino Production and Beam Focus: To transmit appreciable power via neutrinos, the beam must be incredibly intense and well-focused. Innovations might include using plasma wakefield acceleration for more compact accelerators or novel superconducting materials for more efficient and powerful magnetic focusing.

Cross-Section Enhancement: While we can't change the fundamental cross-section of neutrino interactions, we can increase the effective cross-section by using quantum resonance effects or other advanced physics concepts currently in theoretical stages.

Breakthrough in Detection: Moving beyond conventional photodetection, using quantum coherent technologies or metamaterials could enhance the interaction rate detectable by the system.

Scalable and Safe Operation: As the system scales, ensuring safety and managing the high-energy particles and radiation produced will require advanced shielding and remote handling technologies.

Example of a Scaled Concept

To visualize what a scaled-up neutrino power transmission system might look like, consider the following:

Accelerator: A 10 GeV proton accelerator, with a beam power of 1 GW, producing a focused neutrino beam through a 1 km decay tunnel.

Neutrino Beam: A beam with a diameter of around 10 meters at production, focused down to a few meters at the detector site several kilometers away.

Detector: A 100 kiloton water Cherenkov or liquid scintillator detector, buried deep underground to minimize cosmic ray backgrounds, equipped with around 100,000 high-efficiency photodetectors.

Power Output: Assuming we could improve the overall system efficiency to even 0.1% (a huge leap from current capabilities), the output power could be: [ P_{\text{output}} = 1\text{ GW} \times 0.001 = 1\text{ MW} ]

This setup, while still futuristic, illustrates the scale and type of development needed to make neutrino power transmission a feasible alternative to current technologies.

Conclusion

While the concept of using neutrinos to transmit power is fascinating and could overcome many limitations of current power transmission infrastructure, the path from theory to practical application is long and filled with significant hurdels.

#Neutrino Energy Transmission#Particle Physics#Neutrino Beam#Neutrino Detector#High-Energy Physics#Particle Accelerators#Neutrino Interaction#Energy Conversion#Direct Energy Conversion#High-Voltage Direct Current (HVDC)#Experimental Physics#Quantum Materials#Nanotechnology#Photodetectors#Thermoelectric Generators#Superfluid Helium#Quantum Dots#Plasma Wakefield Acceleration#Magnetic Focusing Horns#Cherenkov Radiation#Scintillation Light#Silicon Photomultipliers (SiPMs)#Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs)#Particle Beam Technology#Advanced Material Science#Cost-Effectiveness in Energy Transmission#Environmental Impact of Energy Transmission#Scalability of Energy Systems#Neutrino Physics#Super-Kamiokande

0 notes

Text

Particle Accelerator Magnets

Particle Accelerator Magnets Magnets are ubiquitous in modern life, used in motors, generators, wind turbines, steel foundries, toys, and all sorts of technological equipment. They are also essential for several distinct classes of device, including particle accelerators. Beams from particle accelerators are used to treat cancer patients and to create radioactive isotopes for medical diagnostics,…

View On WordPress

#Alnico#Alnico alloy magnets#AlNiCo magnet#Alnico Magnets#circular accelerators#large magnet#linear accelerators#magnet plating#Magnet Price#magnet strength#magnetic field#magnetic force#magnetic material#magnetic separation#Particle Accelerator Magnets#Particle accelerators#strongest magnets

0 notes

Text

Hey look, the particles are waving!

1 note

·

View note

Text

actually i think "actual genius scientist with an incredibly high IQ that turns into the dumbest whore for some dick" is an untapped resource. we should look into that

#ftm nsft#ftm breeding#ftm cnc#ftm switch#conceptionacception#just nutted in his hole now hes back tinkering with his particle accelerator#i saw some nice nsft art of a scientist chara i really like in basically this scenario and it opened up something in me

984 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 25: Introduction to Particle Physics

25.1 Introduction Particle physics is the study of the fundamental particles and forces that make up the universe. It seeks to understand the building blocks of matter, their interactions, and the laws governing these interactions. This chapter provides an overview of the key concepts and principles in particle physics, laying the groundwork for the more detailed discussion of the Standard Model…

View On WordPress

#Bosons#Electromagnetic Force#Fermions#Particle Accelerators#Particle Physics#Strong Nuclear Force#Weak Nuclear Force

0 notes

Text

playing laser with tweek

#NASCAAAARRRR#tweek ends up going so fast it creates so particle accelerator effect#south park#craig tucker#tweek tweak#sp creek

922 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi guys it's Beef again (plus bonus doodle I made of him in class)

#potp#phantom of the paradise#beef potp#art#drawing#sketch#beef particle accelerator#in my mind#i'm rotating him aroud in there at all times of day

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

the elements at the end of the periodic table barely feel like real elements to me. idk, if you can't hold a lump of it in your hand without it exploding due to radioactivity--man, radioactivity is barely the right word, it's a loose mass of neutrons and protons that only just holds together for a few microseconds--you can't do chemistry with it. it's not a chemical element, in the sense it is not found as part of any compounds on Earth or in space, because it does not exist long enough to form chemical bonds. i get that you wanna finish out the last period, make the bottom right corner nice and square. but you're not doing chemistry. you're doing Stupid Particle Accelerator Tricks.

#and maybe there's no hard cutoff between 'radioactive element'#and 'fun thing to do with a particle accelerator that looks sorta like an element if you squint'#but maybe the ones where the most stable isotopes have half-lives measured in microseconds need like idk an asterisk next to them#or something

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wake up, Babe!

New Burrow's End theory just dropped!

#just watch#Last Bast is particle accelerator access building#Lila's gonna be the one to figure out how to turn it on again :)#instagram's algorithm has your number Aabria#dimension 20#burrow's end

518 notes

·

View notes

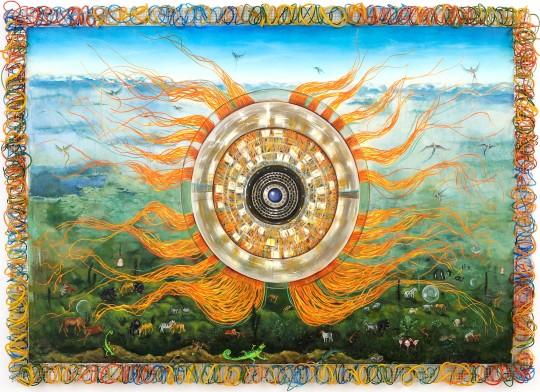

Photo

Julia Curyło — LHC, Genesis (oil on canvas & aluminium and plastic frame, 2011)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

YES i DID also redesign them

im trying to decide............

#skibidi tag#skibidi fanart#skibidi toilet#art#titan tvman#titan speakerman#titan cameraman#ttvm is easy but i wonder how distinct each species is!!#i need yall to not @ me abou tthe cores. i stopped half way thru to compile images of what i want the cores to look like inside and out#hhgrrhg maybe ill share it but rn its kinda nothing LSKLGFJL#camera core: lenses/a focused laser; speaker: (whispers) its a big speaker; tv: particle accelerator!!!!!!#i actctually want either camera or speakers to have centrifugal force... maybe cameras bc of my fic.... but hwat to do w speakers....#ttvm is a liiiiiittle embarrassed by his spots.... no one else has them (maybe).......

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Power of Attraction: Magnets in Particle Accelerators

The Power of Attraction: Magnets in Particle Accelerators In 1820, Hans Christian Oersted gave a demonstration on electricity to a class of advanced students at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. Using an early battery prototype, he looked to see what effect an electric current would have on a compass, and since he hadn’t had time to test his experiment beforehand, the outcome was just as…

View On WordPress

#Alnico#Alnico alloy magnets#AlNiCo magnet#Alnico Magnets#circular accelerators#large magnet#linear accelerators#magnet plating#Magnet Price#magnet strength#magnetic field#magnetic force#magnetic material#magnetic separation#Particle Accelerator Magnets#Particle accelerators#strongest magnets

1 note

·

View note

Note

can i give the saint 6 cans of monster energy?

day 334

#rain world#rainworld#rain world art#rain world downpour#rain world fanart#rainworld art#rainworld fanart#saint rain world#saint rainworld#saint rain world fanart#THEYRE TURNING INTO A PARTICLE ACCELERATOR!!!!!#i cant believe youve done this#/ref

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

didnt this shit kill baymax

66 notes

·

View notes