#Outlining

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

*In writing terms, an architect is someone who plots out, plans, and outlines things before drafting. A gardener is someone who takes an initial idea and then just writes, seeing how the idea grows without specific plans.

Some people use the terms “plotter” and “pantser” (as in, going by the seat of their pants) for these writing styles, but I prefer architect and gardener.

#writers of tumblr#writers on tumblr#writing polls#poll blog#pollblr#writer polls#writers#writing queue#tumblr polls#writing community#writing styles#outlining#drafting#creative writing#creative writers#architect#architect writer#gardener#gardener writer#plotter#pantser#go with the flow writing#pre-planned writing#writer community

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you hate writing outlines it's because of how they're taught in school. Toss out indentation and Roman numerals and map out your writing how you want to. Outlines are your FRIEND, dammit. This goes for everything, from political essays to fanfiction. If it's written you need an outline because the outline is for you. It can be general, vague, or a mixture of both! Be as informal as you want, who cares. They're to keep you on track and keep your writing flowing, so don't disregard them even if you dreaded making them in grade school. My outlines by chapter tend to look like this: 1. Character "P" goes to the diner to meet character "Q."

2. "P" tells "Q" about how the confrontation went. (dialogue I thought up on a bus ride) That's when shit goes DOWN. They're yelling, they're drawing attention to themselves, but before they can take it outside, "P" says (dialogue I thought up in the shower).

3. THEN "Q" SAYS THAT ONE LINE THAT "R" SAYS TO HIM IN CHAPTER FIVE BECAUSE THAT'S CALLED COHESION WOOOOO

4. idk they both leave??? you'll figure it out later

5. Self-reflection for "P." Keep your main point on how his moral compass goes to extremes and hurts others. He finally is realizing that HE is the PROBLEM

6. "P" drives to "Q's" house to apologize but GUESS WHO ANSWERS THE DOOR it's "R" and then just end the chapter there This is coming from someone who didn't write with outlines for years. Now I don't write anything longer than 400 words without one! Make them your own, make them so that they're useful to you. That's their purpose, so accept the help!

#writers on tumblr#writing tumblr#writing help#writing advice#writing tips#writing blog#writer tips#writing motivation#outlining#book writing#novel writing#writeblr#writer#writing tip

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

You don’t have to pay for that fancy worldbuilding program

As mentioned in this post about writing with executive dysfunction, if one of your reasons to keep procrastinating on starting your book is not being able to afford something like World Anvil or Campfire, I’m here to tell you those programs are a luxury, not a necessity: Enter Google Suite (not sponsored but gosh I wish).

MS Office offers more processing power and more fine-tuning, but Office is expensive and only autosaves to OneDrive, and I have a perfectly healthy grudge against OneDrive for failing to sync and losing 19k words of a WIP that I never got back.

Google’s sync has never failed me, and the Google apps (at least for iPhone) aren’t nearly as buggy and clunky as Microsoft’s. So today I’m outlining the system I used for my upcoming fantasy novel with all the helpful pictures and diagrams. Maybe this won’t work for you, maybe you have something else, and that’s okay! I refuse to pay for what I can get legally for free and sometimes Google’s simplicity is to its benefit.

The biggest downside is that you have to manually input and update your data, but as someone who loves organizing and made all these willingly and for fun, I don’t mind.

So. Let’s start with Google Sheets.

The Character Cheat Sheet:

I organized it this way for several reasons:

I can easily see which characters belong to which factions and how many I have named and have to keep up with for each faction

All names are in alphabetical order so when I have to come up with a new name, I can look at my list and pick a letter or a string of sounds I haven’t used as often (and then ignore it and start 8 names with A).

The strikethrough feature lets me keep track of which characters I kill off (yes, I changed it, so this remains spoiler-free)

It’s an easy place to go instead of scrolling up and down an entire manuscript for names I’ve forgotten, with every named character, however minor their role, all in one spot

Also on this page are spare names I’ll see randomly in other media (commercials, movie end credits, etc) and can add easily from my phone before I forget

Also on this page are my summary, my elevator pitch, and important character beats I could otherwise easily mess up, it helps stay consistent

*I also have on here not pictured an age timeline for all my vampires so I keep track of who’s older than who and how well I’ve staggered their ages relative to important events, but it’s made in Photoshop and too much of a pain to censor and add here

On other tabs, I keep track of location names, deities, made-up vocabulary and definitions, and my chapter word count.

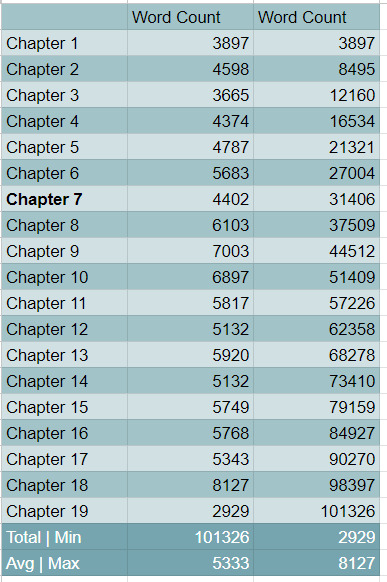

The Word Count Guide:

*3/30 Edit to update this chart to its full glory. Column 3 is a cumulative count. Most of what I write breaks 100k and it's fun watching the word count rise until it boils over.

This is the most frustrating to update manually, especially if you don’t have separate docs for each chapter, but it really helps me stay consistent with chapter lengths and the formula for calculating the average and rising totals is super basic.

Not that all your chapters have to be uniform, but if you care about that, this little chart is a fantastic visualizer.

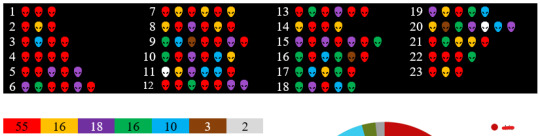

If you have multiple narrators, and this book does, you can also keep track of how many POVs each narrator has, and how spread out they are. I didn’t do that for this book since it’s not an ensemble team and matters less, but I did for my sci-fi WIP, pictured below.

As I was writing that one, I had “scripted” the chapters before going back and writing out all the glorious narrative, and updated the symbols from “scripted” to “finished” accordingly.

I also have a pie chart that I had to make manually on a convoluted iPhone app to color coordinate specifically the way I wanted to easily tell who narrates the most out of the cast, and who needs more representation.

—

Google Docs

Can’t show you much here unfortunately but I’d like to take an aside to talk about my “scene bits” docs.

It’s what it says on the tin, an entire doc all labeled with different heading styles with blurbs for each scene I want to include at some point in the book so I can hop around easily. Whether they make it into the manuscript or not, all practice is good practice and I like to keep old ideas because they might be useful in unsuspecting ways later.

Separate from that, I keep most of my deleted scenes and scene chunks for, again, possible use later in a “deleted scenes” doc, all labeled accordingly.

When I designed my alien language for the sci-fi series, I created a Word doc dictionary and my own "translation" matrix, for easy look-up or word generation whenever I needed it (do y'all want a breakdown for creating foreign languages? It's so fun).

Normally, as with my sci-fi series, I have an entire doc filled with character sheets and important details, I just… didn’t do that for this book. But the point is—you can still make those for free on any word processing software, you don’t need fancy gadgets.

—

I hope this helps anyone struggling! It doesn’t have to be fancy. It doesn’t have to be expensive. Everything I made here, minus the aforementioned timeline and pie chart, was done with basic excel skills and the paint bucket tool. I imagine this can be applicable to games, comics, what have you, it knows no bounds!

Now you have one less excuse to sit down and start writing.

#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writing a book#writing#writeblr#organizing your book#outlining#shut up and write the book#google sheets#google docs

982 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random Plot Points

A little about me as a writer, I love daydreaming about adventure stories. I usually know the general set up and larger plot points but oftentimes struggle with the how, how do characters get from point A to point B.

So, I made a list of random challenges for my characters that I look at when I'm stuck.

Sharing in case helpful to others! (intended for adventure, sci-fi, fantasy stories)

characters are delayed/blocked/experience a natural disaster (storm, fire, flood, avalanche, earthquake, epidemic, etc) (BONUS and forced to take a detour from the original path)

character(s) is trapped (quick sand, fall through ice, in room filling with poison, on sinking ship, in a trash compactor on the Death Star, etc) (BONUS- fall into hidden room and discover something)

characters go to a festival/ball/party/political summit (where inevitably it all goes wrong)

character(s) overhears a secret (at bar, at party, from a whispered conversation below them in a stairway, etc)

characters are attacked by an animal or mysterious force

characters(s) caught in a mob/riot

character wins/loses something in a bet

character is brainwashed or possessed

character is stranded/lost

character is poisoned

character succumbs to injury or illness

characters are chased/ attacked by antagonists

character is captured or arrested (and needs to be rescued)

character is kidnapped and kidnappers make a demand for their release (financial ransom, exchange of information, prisoner exchange, etc)

character(s) go undercover to retrieve information

characters decide to steal something they need for their quest (weapon, magical object, money, information, etc). (BONUS- time for a well-planned heist!)

characters need to protect/ retrieve/ destroy something

characters uncover a network of spies (up to you if they're unexpected allies or antagonists)

characters discover hidden passageway, room, ruins etc that leads to an important clue

characters forced to hide from someone/something

characters need to escape

characters lured into trap set by villain (BONUS if the villain doesn't even care who wins but only goaded them to learn how a magical object works, the extent of heroes powers, emergency response system of a government, etc)

characters set trap for villain (BONUS- use someone or something important as bait) (if in Act 2, they fail)

characters reveal critical information to villain in disguise

a character is mistaken for someone else (and then is wrongfully arrested, receives information not intended for them, etc)

characters receive help (hitch a ride, get help hiding from captors, get help escaping somewhere, etc) from an unlikely new ally

characters forced to team up with an unlikely ally/ morally grey character, etc

characters learn something from simple library research (an oldie but a goodie)

characters just literally just stumble upon or witness something important (secret weapon, secret society etc)

characters uncover a secret map/ coded message on the back of an old unassuming document (time for a classic treasure hunt!)

someone escapes from prison (an old villain or an old ally) that changes the quest

someone is being blackmailed (or otherwise forced to act against the protagonists)

someone is discredited (rumor, disinformation campaign etc)

something stolen from your characters

something (document, magical object, money) turns out to be fake

OR, something unassuming turns out to have special powers or meaning

something is hacked (defense system, infrastructure, bank, private records, etc)

something critical is attacked (important bridge, port, bank/ financial system, safehouse, capitol building, character's familial home, etc.)

a computer virus is unleashed

a biological weapon is unleashed

a piece of information the characters believed was true, is false

an ancient myth turns out to be true

a secret is made public

A law is changed or a vote on a critical piece of legislation loses/wins

a political opponent wins an election/ a political ally loses an election

character(s) help a passerby (from raiders, local tyrant, beast, mystical force, etc)

characters "follow the money" and realize someone who was thought to be their ally is actually working for... (crime syndicate, villain, local tyrant etc)

#writeblr#writing tips#outlining#writing resources#writing prompts#writing#prompt list#fantasy writing#my stuff

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, well, well if it isn't that placeholder plot point I put in the outline while I was sleep deprived. I knew we'd meet again one day

#writeblr#writblr#writing#writer problems#writer community#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#writerscommunity#creative writing#writing humor#writing memes#writing problems#writing process#writer#writers community#writing community#writing advice#outlines#outlining#screenplay#script#screenwriting#scriptwriting

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

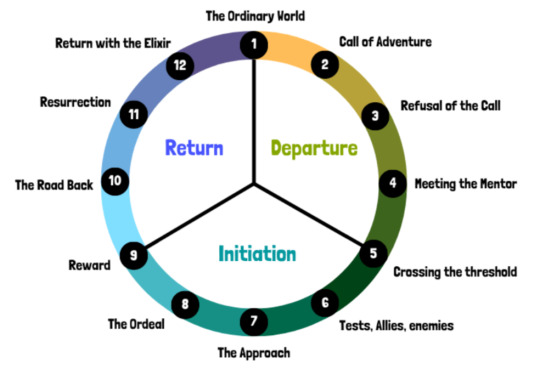

Let's talk about story structure.

Fabricating the narrative structure of your story can be difficult, and it can be helpful to use already known and well-established story structures as a sort of blueprint to guide you along the way. Before we delve into a few of the more popular ones, however, what exactly does this term entail?

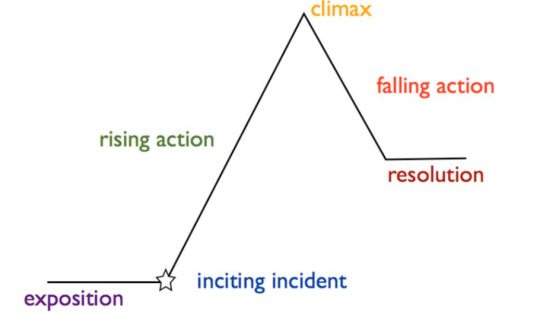

Story structure refers to the framework or organization of a narrative. It is typically divided into key elements such as exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, and serves as the skeleton upon which the plot, characters, and themes are built. It provides a roadmap of sorts for the progression of events and emotional arcs within a story.

Freytag's Pyramid:

Also known as a five-act structure, this is pretty much your standard story structure that you likely learned in English class at some point. It looks something like this:

Exposition: Introduces the characters, setting, and basic situation of the story.

Inciting incident: The event that sets the main conflict of the story in motion, often disrupting the status quo for the protagonist.

Rising action: Series of events that build tension and escalate the conflict, leading toward the story's climax.

Climax: The highest point of tension or the turning point in the story, where the conflict reaches its peak and the outcome is decided.

Falling action: Events that occur as a result of the climax, leading towards the resolution and tying up loose ends.

Resolution (or denouement): The final outcome of the story, where the conflict is resolved, and any remaining questions or conflicts are addressed, providing closure for the audience.

Though the overuse of this story structure may be seen as a downside, it's used so much for a reason. Its intuitive structure provides a reliable framework for writers to build upon, ensuring clear progression and emotional resonance in their stories and drawing everything to a resolution that is satisfactory for the readers.

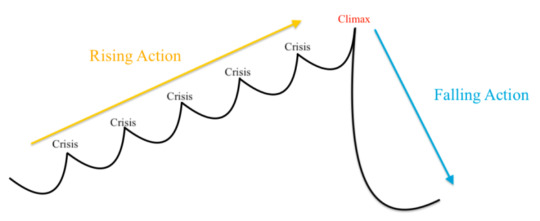

The Fichtean Curve:

The Fichtean Curve is characterised by a gradual rise in tension and conflict, leading to a climactic peak, followed by a swift resolution. It emphasises the building of suspense and intensity throughout the narrative, following a pattern of escalating crises leading to a climax representing the peak of the protagonist's struggle, then a swift resolution.

Initial crisis: The story begins with a significant event or problem that immediately grabs the audience's attention, setting the plot in motion.

Escalating crises: Additional challenges or complications arise, intensifying the protagonist's struggles and increasing the stakes.

Climax: The tension reaches its peak as the protagonist confronts the central obstacle or makes a crucial decision.

Falling action: Following the climax, conflicts are rapidly resolved, often with a sudden shift or revelation, bringing closure to the narrative. Note that all loose ends may not be tied by the end, and that's completely fine as long as it works in your story—leaving some room for speculation or suspense can be intriguing.

The Hero’s Journey:

The Hero's Journey follows a protagonist through a transformative adventure. It outlines their journey from ordinary life into the unknown, encountering challenges, allies, and adversaries along the way, ultimately leading to personal growth and a return to the familiar world with newfound wisdom or treasures.

Call of adventure: The hero receives a summons or challenge that disrupts their ordinary life.

Refusal of the call: Initially, the hero may resist or hesitate in accepting the adventure.

Meeting the mentor: The hero encounters a wise mentor who provides guidance and assistance.

Crossing the threshold: The hero leaves their familiar world and enters the unknown, facing the challenges of the journey.

Tests, allies, enemies: Along the journey, the hero faces various obstacles and adversaries that test their skills and resolve.

The approach: The hero approaches the central conflict or their deepest fears.

The ordeal: The hero faces their greatest challenge, often confronting the main antagonist or undergoing a significant transformation.

Reward: After overcoming the ordeal, the hero receives a reward, such as treasure, knowledge, or inner growth.

The road back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, encountering final obstacles or confrontations.

Resurrection: The hero faces one final test or ordeal that solidifies their transformation.

Return with the elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world, bringing back the lessons learned or treasures gained to benefit themselves or others.

Exploring these different story structures reveals the intricate paths characters traverse in their journeys. Each framework provides a blueprint for crafting engaging narratives that captivate audiences. Understanding these underlying structures can help gain an array of tools to create unforgettable tales that resonate with audiences of all kind.

Happy writing! Hope this was helpful ❤

Previous | Next

#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#story writing#storytelling#story structure#plot development#outlining#plot structure

396 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stripping away Supports

In classic outlining structure, the midpoint is where your MC loses all the advantages they’d relied on up until that point—allies, resources, powers, etc. In fact, this structure is used in so many films that the ‘characters fight at the midpoint’ is an easily found cliché throughout media.

However, there are other ways of stripping away your MC’s supports to achieve the same effect.

They fight

Okay I know I just implied we might want to avoid this, but why fix what’s not broke? The important part about following the ‘characters fight at the midpoint’ trope is to ensure the fight doesn’t start at the midpoint, but rather starts from the very moment the characters are seen with each other/meet. The fight should be about something that’s been brewing underneath all of their interactions from the beginning—the one thing they should’ve talked about but didn’t. The ‘elephant in the room’.

This fight is less of a fight but an unearthing of feelings, thoughts, and problems that have always been there, but have been ignored or avoided up until then. What’s the event that unearths these truths? Typically, something threatening or scary causes people to speak ‘out of turn’…

2. The protagonist chooses to go on alone

Something big happened, something so dangerous and scary that the protagonist intentionally pushes away their allies in order to protect them… Of course, later they might realize that they are stronger together anyway. This is also a bit of a cliché, but done thoughtfully can be very impactful.

3. The allies are in over their head

The reversal of the last trope, instead of the protagonist pushing their allies away, the allies decide this quest is far too dangerous and risky for them… The protagonist is abandoned by their allies. Later, these supports may return, their love for the protagonist stronger than their fear of the situation, but whatever happened must have spooked them bad enough to lead them to betrayal.

4. An integral piece they’ve been relying on has been destroyed

The hideout was found and torched, the old man’s journal was tossed into the sea, the leader/mentor/keeper of information has been kidnapped or killed. Maybe the allies and the protagonist are still together, but one important thing that’s been keeping them together or leading them has been lost, now they have to adapt and improvise on the fly if they wish to continue their quest.

5. An integral piece they’ve been relying on turned out to not be true or important

Similar to the last but with a bit of a twist. They’ve been following the wrong lead all along—where to go next now that the very foundation of their quest is crumbling beneath them?

What are some other ways of fulfilling the midpoint reversal?

#writing#writers#writing tips#writing advice#writing inspiration#creative writing#writing community#books#film#filmmaking#screenwriting#novel writing#fanfiction#writeblr#midpoint#midpoint reversal#stripping away supports#outlining#planning

593 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snowflake method of writing? Hehe nah I do the whole “outline this as far as Brain go then fly by the seat of my pants and blaze through the second act slump until I reach the end” method of writing.

#writers on tumblr#write wrong#writeblr#writer problems#writer stuff#writing process#fiction writing#writing community#writing blog#writing a book#writing adventures#on writing#creative writing#writeblogging#writer life#queer writers#queer writer#lgbtq writers#trans writers#bisexual#gender queer#demisexual#ao3 writer#this book is my love letter to fanfic and fandom#outlining#outline#writing plans

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

I swear there is no better high than writing; even just frantically outlining a novel concept that I feel really excited about has left me with a lasting like "omg I am a genius I am such a good writer the best to ever do it" even though I know full well that once this honeymoon period wears off I'm obviously going to have frustrations/writer's block like we all do, but like for now AHAHAHA I AM GOD

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trying to learn balance but exhaustion is slowly creeping in….

ft. the only pens I’ll use

#law school#law student#law studyblr#university#college#collegeblr#college blogging#study blog#studyblr#study break#study#books#library#reading#book#outline#outlining#lawyer#university studyspo#uniblr#uni blogging#study desk#study community#study core#school#notes#study notes

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

on plotting: the rule of three

what is it?

about the rule

other people might call it something different, but for me, the rule of three in fiction writing is a foreshadowing tool. to persuade your audience of something and make a twist or story element feel earned, you hint at it at least three times.

things are appealing in sets of three. if something happens once, it’s random, twice is coincidence, and three times is a pattern.

a brief guide

on using the rule

use showing over telling. the whole point of this rule is to convince your reader of something, and unfortunately you can’t “trust me bro” your way into establishing key information.

look into types of foreshadowing. you can call attention to these scenes using strategies like symbolism or irregular description, in which you call unusual attention to a seemingly insignificant detail.

let’s say you want to convey that a specific character is untrustworthy. let’s break this down into three scenes.

first, let’s say we catch this character sneaking out after they said they were going to bed. this raises questions of why they lied and what they’re actually doing. using a direct scene like this first will alert the reader and make them more likely to notice less obvious information later on.

second, we maybe include a scene where they directly contradict something they said earlier. it helps if it’s a minor detail that wouldn’t make much sense to lie about, such as their birthday.

the third scene is the one that should cement this item in your readers’ minds. maybe this scene is a step above the others; maybe this time, the character tries to pit everyone else against each other. maybe they steal or participate in a much bigger lie.

if you’re building up to a betrayal, this can either be the betrayal itself or the scene directly before.

use this rule in moderation. if you bring up something too many times without solidifying it, the story risks becoming repetitive.

brainstorm, create brief outlines of the scenes you want to include, and then decide where in the story these scenes should go.

when i’m using the rule of three to revise, i create a list of all the scenes and chapters i currently have and tack the new scenes on as sticky notes where i see fit.

this may be a bit excessive.

instead, you might consider creating a rough outline of the plot or plots you want to write and jotting down a list of scenes according to where in each arc they should fall, or simply having a document or notepad where you write down ideas.

in action

media examples

the hunger games. the poisonous plant nightlock is specifically mentioned three times, once in the capitol and twice during the games, before it is used for a major plot point.

the karate kid. the crane kick technique is introduced early on, and there are scenes where the main character specifically practices his crane kick before it wins him the match at the end of the film.

---------------------------

thanks for reading! hope this was helpful :)

tip jar | so what even is radio apocalypse?

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

My gods this is overdue. So the first one some Plot Structures that Aren't The Heroes Journey, we're starting with:

7 Point Plot Structure

This one's created by Dan Wells, an American Horror writer that gives us a fairly streamlined structure that's focused on every beat flowing from the previous and into the next. This can lend itself very well to novellas, shorter narratives, and can easily be bulked out for a fuller story with sub-plots. If you're interested here's a link to his lecture on this particular bit of structure that I found pretty interesting.

The Seven Point Plot Structure breaks a story into three familiar acts, separated further by Seven Plot Points or beats. These are the major turning points of the story, the moments that change the direction the narrative is going in.

One of the things I like about this structure is that it has the flexibility to work for planners and pansters and those in-between. It can be as sparse or as detailed as you like, the Seven Points themselves serving as narrative landmarks to help keep your writing oriented.

I'd suggest pairing this with solid character arcs to help better inform some of these points.

So lets break it down, and I'll be using Captain America: The First Avenger to give examples of the Plot Points in action.

Act One:

Plot Point 1

Hook: Status Quo

Introduces the story, establishing the world, characters, any themes and ideas at play, and most importantly, the Status Quo, the normal world that gets left behind. Here we meet the protagonist and see how they fit in and engage with the world around them.

Example: During WW2, Steve Rogers is a sickly, small man that wants to be a solder, and he attempts to enlist for military service repeatedly and is pushed back due to his health conditions. His best friend Bucky is a soldier and going to war and is there on his last night in New York. Here their friendship is established as is key elements of both characters, Steve's stubborn determination, his belief that he has no right to do less than others, his keen dislike for bullies and his friendship with Bucky.

Plot Point 2

Plot Turn 1: Inciting Incident

The inciting incident changes the ordinary world and breaks Status Quo, throwing the protagonist into the world of adventure and conflict. Usually via an outside force forcing them to react. Usually, the protagonist is somewhat on the back foot at this stage, acting reactively.

Example: Steve's latest attempt to enlist is successful, as a Dr Erskine (a German scientist) having overheard Steve's arguments for signing up is impressed by his character. He probes Steve's further and decides to offer him a chance at an experimental program.

Act Two: The pinch signals the end of act one and the start of act two.

Plot Point 3

Pinch 1: Situation escalates

The pinch point signals an escalation of the conflict, and a raising of stakes. Villains and antagonistic forces make an appearance, placing obstacles in the protagonist's path. Establish challenges and dangers for our characters and reveal some of their nature in turn. They are still reactive,

Example: Steve successfully passes Erskine's tests, proves himself further as a brave, smart, and tenacious man, and is chosen for Project Rebirth. He undergoes transformation from little guy to Big Buff Hero. The Pinch occurs when a HYDRA assassin shoots Dr Erskine and steals a vial of the Super Soldier Serum. Steve with his newly enhanced body chases him down, showing off feats of athleticism and strength beyond the ordinary man. Alas the assassin kills himself and Steve is rejected from military service by Colonel Phillips.

Plot Point 4

Midpoint: Protagonist shifts from reactive to proactive

The midpoint, the centre of your story should be where your protagonist shifts from reactive to proactive, from responding to events to driving them with their choices. They take charge, make moves, all informed by a revelation of some kind, either new information or understanding that changes things for them.

Example: Italy, Steve, having been acting as a propaganda mascot to sell war bonds, learns that Bucky's division and hundreds of others has been captured. Despite orders, Steve, with the help of Peggy Carter and Howard Stark, parachutes behind enemy lines and successfully rescues the captive soldiers and Bucky. During this he comes face to face with the Antagonist, Johann Schmidt, the head of HYDRA, aka, the Red Skull. Upon return, Steve is given command and successfully leads his commando unit into battle against HYDRA.

Plot Point 5

Pinch 2: Major setback

Usually in response to the protagonist's proactive actions, things go from bad to worse. There's a second brush with the antagonist in a way that hurts and sets them back. Usually a defeat at great cost, heartbreak or some kind of devastating loss. A death, team splitting up, villain obtaining the Mcguffin. If there's success it comes at great cost and might not be worth it.

Example: After a successful series of events, The Howling Commandos board a moving train to capture a HYDRA scientist. Tragically, they are prepared, and Bucky, Steve's best friend and second in command, falls to his death. Steve mourns alone.

Act 3: The pinch signals the end of act two and the start of act three.

Plot Point 6

Plot Turn 2: Key to Victory is discovered

By whatever means, the pyrrhic victory of the last plot point, a new discovery, a turn coat, a lesson learned, the key to victory is found and decided upon. Whatever the character needs, they now have, and it just might be enough to win. Could be a magical item, the magic within, a driving need for vengeance, the decision to sacrifice, or simply a desperate gamble.

Example: After Zola's interrogation and learning about the Schmidt's plan to take over the world through conquest and highly advanced weaponry, Steve, driven by loss and a need to protect, makes the choice for a full frontal attack at the heart of HYDRA itself.

Plot Point 7

Resolution: Conflict resolved

Through sacrifice, trial, blood, sweat and tears, the protagonist achieves victory whether complete, partial, pyrrhic or otherwise, and the immediate conflict is resolved. Evil is defeated, if that's your ending of choice. The lessons have been learned and the now changed protagonist can return to the new Status Quo in a changed world.

Example: Schmidt is defeated, and Steve valiantly sacrifices his life to destroy the HYDRA Valkyrie craft and it's weapons. The war is over and those that knew him mourn. The down turn is uplifted by an epilogue showing Steve alive and well in the 21st century.

If you were to visualise this plot you could imagine it as a horizontal zigzagging line, rising and falling with victory and loss, or rising and falling action, whatever works best for you.

For me I like to view things vertically like bullet points on a list, and once you have those main 7 Plot Points in place, you can fill out the events of the story with events either leading to or coming from these Plot Points.

Variations

Such a sparse structure has plenty of room for additional points like prologues and epilogues.

For example:

The Ice Monster Prologue, named for GRR Martin's A Game of Thrones prologue, where a member of the Night's Watch witnesses icy undead and a White Walker killing off his compatriots and driving him to abandon his post.

We have such a prologue with our film example:

After a scene showing modern military men entering the frozen plan and finding Captain America's shield, we go back in time to a Norwegian Church. Here we see Schmidt stealing the Tessaract, "Odin's treasure". He kills off it's keeper and sends his men to destroy the town of innocents. This establishes a Mcguffin (the Tesseract) and the Antagonist, his intelligence, drive and ruthlessness.

Another variation is the Try-Fail Cycle.

Here the plot revolves around attempting to overcome obstacles and setbacks before making progress towards the resolution. I think a good example of this would be the first Despicable Me where Gru faces a considerable number of failures and setbacks in his attempts to get what he needs to steal the moon.

Structurally, a lot of these occur after the First Pinch, which feeds into the big shift at the Midpoint.

This structure can serve for Romance as well.

Hook: Status quo

Plot Turn 1: Lover interests meet or their current relationship status changes

Pinch 1: Love interests enter a conflict that stands in the way of romance

Midpoint: One or both of the Love interests decide to resolve the conflict and pursue the romance

Pinch 2: Something goes wrong, and all seems hopeless

Plot Turn 2: One of the love interests discovers the key to winning the other's heart

Resolution: Conflict is resolved, love interests live happily ever after

How to use the 7 Point Plot Structure

With any outline or plan, it's important to have a few Good Ideas about the direction and nature of your story before you begin, one of the most important being the Resolution. How do you want things to end? What changes occur and how do they reshape the world? Then figure out where you start, what the status quo is, what your character is like before they go through everything. What are their flaws and fears? What do they want and need?

I have my own method, Road-mapping, which I'm still figuring out.

But, knowing where you start, knowing where you'd like to end can help you pint down these points and then all you have to do is fill in the blanks.

Good Writing.

P.s. Hey if you want more stuff like this, consider supporting me at my Patreon

#writeblr#writers on tumblr#writing advice#writing#creative writing#story structure#plotting#outlining#pantsing

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

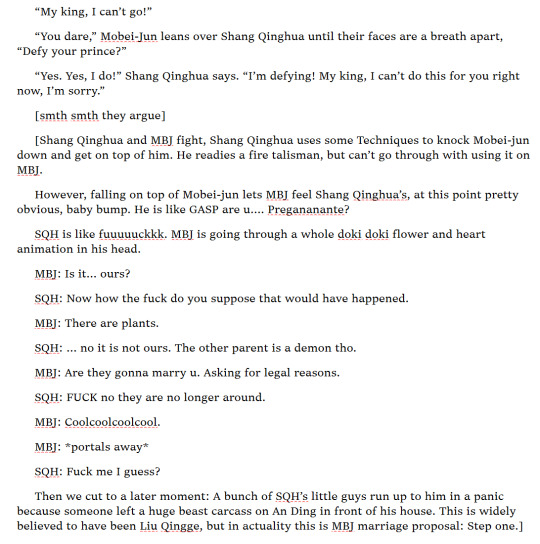

found the original outline i wrote for this scene of WINRN and i cant stop laughing at it

#this was old old its not actually from the chap outline#'asking for legal reasons' keeps running through my head now#WINRN#my fics#burytalks.mp3#burywrites.pdf#mbj#sqh#moshang#mobei-jun#shang qinghua#svsss#scum villain#scum villain's self saving system#svsss fic#scum villain fanfic#my writing#outlining

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

“How do I know if my story needs work or if I’m just being hard on myself?”

As I sit here accepting the fact that at 70k words into Eternal Night’s sequel while waiting for my editor for Eternal Night itself, that I have made an error in my plot.

Disclaimer: This is not universal and the writing experience is incredibly diverse. Figuring this out also takes some time and building up your self-confidence as an author so you can learn to separate “this is awful (when it’s not)” and “this is ok (but it can be better)” and “this isn’t working (but it is salvageable).”

—

When I wrote my first novel (unpublished, sadly), years ago, I would receive feedback all over the chapters and physically have to open other windows to block off parts of the screen on my laptop to slow-drip the feedback because I couldn’t handle constructive criticism all at once. I had my betas color-code their commentary so I could see before I read any of it that it wasn’t all negative. It took me thrice as long as it does today to get through a beta’s feedback because I got so nervous and anxious about what they would say.

The main thing I learned was this: They’re usually right, when it’s not just being mean (and even then, it’s rarely flat out mean), and that whatever criticisms they have of my characters and plot choices is not criticism of myself.

It did take time.

But now I can get feedback from betas and even when I hear “I’d DNF this shit right now unless you delete this,” I take a step back, examine if this one little detail is really that important, and fix it. No emotional turmoil and panic attack needed. I can also hear “I didn’t like it” without heartbreak. Can’t please everyone.

The only time I freak out is when I'm told "this won't need massive edits" followed up by, in the manuscript, "I'd DNF this shit right now". Which happened. And did not, in fact, require a massive rewrite to fix.

So.

What might be some issues with your story and why it “isn’t working”.

1. Your protagonist is not active enough in the story

You’ve picked your protagonist, but it’s every other character that has more to do, more to say, more choices to make, and they’re just along for the ride, yet you are now anchored to this character’s story because they’re the protagonist. You can either swap focus characters, or rework your story to give them more agency. Figure out why this character, above any other, is your hero.

2. Your pacing is too slow

Even if you have a “lazy river” style story where the vibes and marinating in the world is more important than a breakneck plot, slow pacing isn’t just “how fast the story moves” it’s “how clearly is the story told,” meaning if you divert the story to a side quest, or spend too long on something that sure is fluffy or romantic or funny, but it adds nothing to the characters because it’s redundant, doesn’t advance the plot, doesn’t give us more about the world that actually matters to the themes, then you may have lost focus of the story and should consider deleting it, or editing important elements into the scenes so they can pull double-duty and serve a more active purpose.

3. You’ve lost the main argument of your narrative

Sometimes even the best of outlines and the clearest plans derail. Characters don’t cooperate and while we see where it goes, we end up getting hung up on how this one really cool scene or argument or one-liner just has to be in the story, without realizing that doing so sacrifices what you set out to accomplish. Personally I think sticking to your outline with biblical determination doesn’t allow for new ideas during the writing process, but if you find yourself down the line of “how did we get here, this isn’t what I wanted” you can always save the scenes in another document to reuse later, in this WIP or another in the future.

4. You’re spending too long on one element

Even if the thing started out really cool, whether it’s a rich fantasy pit stop for your characters or a conversation two characters must have, sometimes scenes and ideas extend long past their prime. You might have characters stuck in one location for 2 or 3 chapters longer than necessary trying to make it perfect or stuff in all these details or make it overcomplicated, when the rest of the story sits impatiently on the sidelines for them to move on. Figure out the most important reasons for this element to exist, take a step back, and whittle away until the fat is cut.

5. You’ve given a side character too much screentime

New characters are fun and exciting! But they can take over the story when they’re not meant to, robbing agency from your core characters to leave them sitting with nothing to do while the new guy handles everything. You might end up having to drag your core characters along behind them, tossing them lines of dialogue and side tasks to do because you ran out of plot to delegate with one character hogging it all (which is the issue I ran into with the above mentioned WIP). Not talking about a new villain or a new love interest, I mean a supporting character who is supposed to support the main characters.

—

As for figuring out the difference between “this is awful and I’m a bad writer” and “this element isn’t working” try pretending the book was written by somebody else and you’re giving them constructive criticism.

If you can come up with a reason for why it’s not working that doesn’t insult the writer, it’s probably the latter. As in, “This element isn’t working… because it’s gone on too long and the conversation has become cyclical and tiring.” Not “this element isn’t working because it’s bad.”

Why is it bad?

“This conversation is awkward because…. There’s not enough movement between characters and the dialogue is really stiff.”

“This fight scene is bad because….I don’t have enough dynamic action, enough juicy verbs, or full use of the stage I’ve set.”

“This romantic scene is bad because…. It’s taking place at the wrong time in the story. I want to keep it, but this character isn’t ready for it yet, and the vibe is all wrong now because they’re out-of-character.”

“This argument is bad because…. It didn’t have proper build-up and the sudden shouting match is not reflective of their characters. They’re too angry, and it got out of hand quickly. Or I’m not conveying the root of their aggression.”

—

There aren’t very many bad ideas, just bad execution. “Only rational people can think they’re crazy. Crazy people think they’re sane,” applies to writing, too.

I just read a fanfic recently where, for every fight scene, I could tell action was not the writer’s strong suit. They leaned really heavily on a crutch of specific injuries for their characters, the same unusual spot getting hit over and over again, and fights that dragged on for too long being unintentionally stagnant. The rest of the fic was great, though, and while the fights weren’t the best, I understood that the author was trying, and I kept reading for the good stuff. One day they will be better.

In my experience beta reading, it’s the cocky authors who send me an unedited manuscript and tell me to be kind (because they can’t take criticism), that they know it’s perfect they just want an outside opinion (they don’t want the truth, they want what will make them feel good), that they know it’s going to make them a lot of money and everyone will love it (they haven’t dedicated proper time and effort into researching marketing, target audiences, or current trends)—these are the truly bad authors. Not just bad at writing, but bad at taking feedback, are bullies when you point out flaws in their story, and cheap, too.

The best story I have received to date was where the author didn’t preempt with a self-deprecating deluge of “it’s probably terrible you know but here it is anyway” or “this is perfect and I’m super confident you’re going to love it”.

It was something like, “This is my first book and I know it has flaws and I’m nervous but I had a lot of fun doing it”.

And yeah, it needed work, but the bones of something great were there. So give yourself some credit, yeah?

#writing#writing advice#writing a book#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#writeblr#outlining#story structure#editing

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's torture being a writer that can only survive off an outline. I want to write a silly short whump AU of my OCs but my brain requires a 50-page detailed outline.

#whump#writing prompt#writing process#my writing#writing stuff#creative writing#writers block#writers#write#writer#writing#writers on tumblr#writeblr#writerscommunity#writer's problems#writers meme#writer problems#writer stuff#ao3 writer#writers problems#outlining

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fascinating trend I've noticed in developing ideas into outlines/plots: The more I love an idea, the more innovative and meaningful it feels, the harder it is to get it over the first hurdle of becoming a coherent plot

The ideas that feel mid take off like a rocket, then only get better with development. The beloved ideas kind of languish

I suspect I'm being too precious with them and it's making me a coward about it. And all I have to do is commit to writing a bad draft. And yet . . . cowardice has an appeal

#writeblr#writblr#writing#writer problems#writer community#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#writerscommunity#creative writing#writing problems#writing process#writer#writers community#writing community#outline#outlining#plotting#sceenwriting#scriptwriting#scripts

20 notes

·

View notes