i like to suffer creatively✢ ✢ ✢irregular updatesask box open! dm for beta reading/proofreading ❤main @canticome

Last active 2 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

Hi! I was wondering about what the different parts of a book are, and what separates them; like what defines a chapter, scenes, arcs, and 'story beats' . And if there were other ways that stories are sectioned off? I love your blog, keep up the great work :D

Hi, thanks for asking and so sorry for the late response! Let's look into the anatomy of a story and the purpose, length, and some defining features of each part, and hopefully you'll still find this useful ❤

Chapters

Chapters are the largest, most obvious divisions in a story, usually marked by chapter titles or numbers. They create natural pauses for the reader throughout the narrative.

Purpose

Chapters can set the stage for a segment of the story, shift focus to a new event, or provide a clean stopping point. They often frame a moment or sequence by beginning with acquainting the reader with who's here, where we are, and what's happening, and then end with some sort of resolution, revelation, or suspense.

They are also useful to manage focus by shifting from one plotline or emotional register to another, or for POV shifts between characters that don't feel too abrupt or confusing.

Length

Flexible! Can be anywhere from a few hundred to several thousand words depending on your narrative, flow, and pacing. A good tip to keep in mind is to make each chapter feel like a unit of the story: long enough to accomplish its purpose and short enough to keep readers engaged.

---

Scenes

Within a chapter, you have scenes. These are smaller, more focused moments that push the story forward, where characters are in a place, doing, wanting, or reacting to something.

Purpose

Each scene will typically have a specific goal, whether that be to reveal information, escalate tension, develop character relationships, or move the plot forward.

Length

It can range from a paragraph to several pages, depending on what's happening.

A scene takes place in a continuous time and place with the same group of characters. Once any of these change (location, time, or focus), you've likely started a new scene.

---

Arcs

Arcs are what give stories meaning and keep them from feeling static. Rather than making events just feel like things that happen, arcs mean these events add up to change, whether that be a shift in the world, in relationships, or internal.

Character arcs

This is the internal journey a character takes throughout your story (ex: coward to hero, sceptic to believer, ruler corrupted by power, etc.). These arcs don't unfold in one scene, but span the story as your characters grow, learn, develop, and make choices.

Plot arcs

These are specific external threads of events with their own beginning, middle, and end, and often overlap with multiple character arcs (ex: a war campaign, murder investigation, forbidden romance, etc.).

Thematic arcs

Sometimes the story itself has a sort of philosophical journey through its theme and deeper meaning or message. For example, a book may start by asking 'is mercy weakness?' and, by the end, have shown the answer to be 'no, it takes strength to show mercy.' In other words, a thematic arc is a larger idea that your characters and plot work together to convey.

---

Story beats

A "beat" is a single unit of action or emotion, something like the shift from tension to relief, the decision to lie instead of telling the truth, or the tipping point of something a character says before an argument explodes. These keep the scene alive, dynamic, and generally interesting by changing the energy of the scene in some way.

Beats can look like:

Physical action (ex: character slamming a door, fidgeting with a glass, taking a step back)

Dialogue shift (ex: asking a dangerous question, falling silent, lying)

Emotional reaction (ex: laugh, sigh, surge of anger)

Tension pivot (ex: momentary relief that turns into dread, calm suddenly interrupted by conflict)

Think about it like an input and output: a character asks something, another answers, or a character points to something that the narrator then describes. Or sometimes there is no output, like when a character says something that the other cannot answer to, or when the narrator is scene-setting or shifting the camera to a new scene.

The bottom line is, a beat is very flexible, and can be as small as a gesture in a single sentence to a whole confession within lines of dialogue. It's like a pivot, where the energy of the scene shifts somehow.

---

Hope this helped!

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writing community#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers of tumblr#writer help#story writing#writblr#on writing#how to write#deception-united

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you have characters share their age without making it feel forced for the readers? I want to state the ages, but I want it to feel natural.

Thanks for asking! Here are some tips.

1. Let the context convey it.

In some cases, you don't need to say the age of each character outright; rather, it can be implied by their behaviour, setting, or circumstances.

For example, showing your character in high school, taking a driving test, applying to colleges, and similar cues will give the reader a clear enough idea as to their age.

2. Dialogue that feels authentic

If you do want to state the age clearly and outright, a good way to do this is in a line that would realistically come up in conversation. People do mention their age in real life, just not constantly or without reason.

Ex: "Can you believe I'm turning seventeen in a week and still can't cook without burning something?" or "I didn't think I'd be job-hunting at twenty-four but here we are."

A line like "Hi, I'm Adam and I'm twenty" can come off as lazy writing or unnatural dialogue unless your character is literally introducing themselves in a setting where that would be normal (ex: support group, class, camp orientation, etc.).

3. Anchor it to a milestone.

Think about instances in life when your character is hitting a big moment, like a graduation, birthday, legal age threshold, or anniversary. Ages often come up in these situations naturally, and it would make sense for the character, or someone else, to bring it up when talking about it.

Tying the age to an emotional or social moment like this will make it feel more like storytelling than exposition or info-dumping.

4. Have another character say it.

It can be more natural for someone else to bring up the age rather than the character themselves:

Ex: "You're twelve, you don't get to talk like that" or "You were, what, nineteen when you moved here?"

You can also take this as an opportunity to show relationships and dynamics (ex: parent/child, teacher/student, older sibling/younger sibling) without needing to directly state them, either!

5. In narration

Especially in close third or omniscient third person, you can just state the age without making it feel forced by integrating it into the narrative smoothly.

Ex: "At seventeen, James was already more responsible than most adults he knew."

---

If knowing the exact age of the character(s) is crucial for the reader, these are some good ways to do it. However, keep in mind that the readers often don't need to know the precise number as long as you give them a clear enough idea to frame the character's experiences through voice and context.

Hope this was helpful! ❤

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writerblr#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers#writblr#writing community#on writing#plot development#how to write#writers of tumblr#deception-united

125 notes

·

View notes

Note

Any advice on how to kill off multiple characters at the same time?

Killing Many Characters at Once

When writing the simultaneous deaths of multiple characters, it's important to plan carefully to ensure the scene is clear and emotionally effective without losing the reader. Let's look at some key considerations, like narrative purpose, emotional pacing, and the impact on remaining characters and plot development.

1. Mass deaths must matter

I've talked about this previous in my post about killing characters and what to consider before you do, but whatever the motivation may be, don't kill them all just to shock your audience or create angst. Every death should either:

Serve the emotional arc of the survivors

Push the plot forward drastically

Reveal something crucial (about the world or villain, for example)

2. Individual impact

Even if they're all dying at the same time, make the readers feel them one by one. This doesn't mean long monologues for each character—rather, make the reader notice each person's presence, their last action, and their emotions (ties into goals/motivations: fear, courage, love, etc.) before they're gone.

If the situation which has led to this is something along the lines of a war or battle where many hundreds or thousands of people are dying, however, it's better to focus the POV on select characters (likely your main ones) or those who will end up surviving so you can carry it into the aftermath.

3. Staggered deaths in one scene

Although this may have to be the case in certain situations (like an explosion), rather than having them all die in the exact same second, consider structuring it so that it's very close together. This might look like one going down trying to save another, someone else holding off the danger, and so on to keep the pace tight while increasing the impact of the death of each individual character involved by giving them each their moments before death.

4. Pace the aftermath carefully

The true impact of a mass death like this is in the silence after, once it's all over and done and the reality has settled in for those remaining. It's important not to move on too quickly—you just shook the earth, let the reader and characters feel the aftershocks.

5. Survivors carry the weight

The emotional impact of multiple character deaths shouldn't end with the scene where they occur, but rather given continuing significance through the responses of the characters who survive and remain living. This is one of the best parts of character death: the state of grief, guilt, anger, or numbness it leaves in the ones who are left behind. The suffering is over for those who were killed, but for those who weren't, it's just gotten worse.

Survivors may change their goals, behaviour, or relationships as a result of what happened (ex: some might become withdrawn while others distract themselves by a desire for revenge, justice, or redemption). These reactions can make for great character growth and further their arcs.

6. Practical effects of the loss

Consider: how does the absence of these characters affect the group dynamic, leadership structures, or ability to complete a mission, for example?

In the aftermath of an event like this, addressing both emotional and function consequences (concerning the narrative) allows the story to move forward without minimising the impact of the tragedy or making the deaths feel gratuitous or inconsequential to the rest of the plot.

Happy writing! ❤

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writerblr#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers#writblr#writing community#on writing#plot development#how to write#writers of tumblr#deception-united

151 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there! Do you think it's possible to write a character who, despite coming from a very loving family, has major self-esteem and self-confidence issues?

My protagonist comes from a loving and wealthy household but, due to her family's reputation amongst the public (her father and paternal uncles aren't well-liked because of her paternal grandfather and her mother and maternal aunt are the daughters of a prostitute), she ends up having very low self-esteem due to bullying.

Her self-esteem gets worse after her family gets killed and despite wanting revenge on their killer, she feels like she's doing the "wrong" thing (believing that the killer might have loved ones, her family wronged him in some way, etc.)

Hi, thanks for asking! This is definitely very possible and a great setup for internal conflict. Let's look a bit deeper into your protagonist's situation:

Loving family ≠ self-love

As you mentioned, loving families do not automatically create or ensure emotionally healthy children. A supportive home is definitely a strong foundation, but no matter how loving or sheltering it may be, it's not always a shield from external judgement, bullying, or trauma, as in the case of your character. In fact, sometimes having a loving family can actually deepen the guilt or shame a character feels for struggling, since they might feel like they're failing their family by not being strong, grateful, or happy enough.

So it's completely believable for your character to be struggling internally with the bullying she receives. Especially at a younger age, people absorb both what their family tells them and what others are saying, and often the judgement of people closer to their own age can have a bigger effect and have more weight. When they ridicule her, spread rumours, or exclude her, these micro-rejections compound and can absolutely hurt her self-image and -worth.

The effect of grief & tragedy

It's equally believable for the grief of her entire family being taken from her to make everything worse and more complicated, especially for someone already struggling with worth and confidence and whose family already had problems amongst themselves. It makes complete sense for her to want revenge for someone who has killed her loved ones, but the doubts she has despite this can be both a strength and weakness of her character: strength, because this shows that she's deeply empathetic, but weakness in lack of force of will, which is likely influenced by her lack of self-esteem.

---

Tips

Use contradiction in her internal thoughts to show both the conflict she's feeling and the results of her low self-esteem.

Show how she hides her pain (ex: smiling too quickly, shrugging off compliments, dismissing her own successes, etc.)

Let her question herself constantly—not in a way that makes her seem too indecisive, but someone who's self-worth has been slowly destroyed over time will likely be unsure or have difficulty trusting herself, especially in more important decisions (like seeking/enacting revenge).

Introduce characters who challenge her perspective. Having a character who complements and challenges her can push her towards growth and add to the narrative, whether that be by seeing her anger as righteous, encouraging her, or forcing her to stop running from her pain and sit with it.

Hope this was helpful! ❤

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writerblr#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers#writblr#writing community#on writing#plot development#how to write#writers of tumblr#deception-united

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I stumbled across your blog while searching for writing tips and I'm very impressed by how good your advice is and I'd like to ask you for advice, if you don't mind.

I have an assassin character (partially inspired by the huntsman from Snow White) who is tasked with killing an innocent teenaged orphan girl by a jealous noblewoman who was envious of the girl's beauty and because she believes her husband is enamored with her.

But after seeing the girl crying while begging for her life and realizing she's innocent, the assassin couldn't bring herself to kill her and lets her go. Not wanting her employer to find out that she failed her mission, she cuts herself and spins a tale about how the girl had injured her with a hidden dagger (which she asked the girl to hold in order to solidify her lie) during a struggle. After the noblewoman learns that the girl is still alive and well, the assassin is beaten and thrown into a cursed river (that transforms her into a demon) as punishment.

How do I show that —while the assassin did try to kill an innocent person— she was never malicious or evil and had a noble soul in the end?

Hi, thanks for asking! I love the tropes you have here—here are some tips you might find helpful ❤

1. Separate her actions from her intentions.

It's important to show this from the very beginning. Yes, she accepts the mission to kill a young girl, but show why she does this (ex: survival, fear, obligation, bound by debt/oath/blackmail, 'obedience is a virtue,' etc.).

You don't necessarily have to delve too deep right from the start to achieve this as long as the readers can see her discomfort before the moment comes where she shows the girl mercy. Something like a grimace when she hears the girl's age or situation or asking one too many questions about it before heading out can suffice to get the message across!

Depending on how you plan to go about the narrative regarding POVs, right before the assassination, you could also add a moment where she's watching the girl from afar and experiences doubt or hesitation before the main turning point.

2. The mercy must be a choice (that costs her).

Show the character consciously choosing the harder path and paying for it. This is where inner monologue, actions, and emotion are very important in order to make the reader feel and empathise rather than just telling us she spares the girl. You've already mentioned the cut she inflicts upon herself and the punishment she suffers due to her sacrifice, and depicting this through showing the turmoil she's going through is what will make it even more impactful.

3. Tragedy vs. justice

Bringing in the cursed river that transforms her into a demon makes it feel like a moral paradox. Being punished for mercy is tragic; punishment for evil is just. Your character was thrown in not because she was evil but because she defied evil. Playing into this theme can add a lot of depth to your narrative!

Keep in mind that the goal is to make her understandable—she accepted the task of killing a child, which is awful, but she still has a moral compass, however twisted it may be. Make sure you're depicting her rough edges and regrets just as much as that part of her that believed in goodness enough to show mercy and pay the price for it.

Happy writing, hope this helped!

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writerblr#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers#writblr#writers of tumblr#on writing#deception-united

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

How are you, my good fellow?

My two main characters are a divorced couple who were once married because 1) her father was suffering from financial issues and 2) the crappy elders of his family were looking for a new, suitable bride for him after his first wife passed away. Even after the divorce, they are still shown to love and trust each other. The woman still wears the earrings he gifted her and visits him and their adopted kids once a month. On the other hand, the man still keeps her art in a separate section of his home (and strictly forbids anyone—excluding their children from entering) and misses and tries (and fails) to replicate her cooking.

Do you know how I can portray their love and trust for each other despite the awkwardness?

Thanks for asking and so many apologies for the late response ❤ Here are some tips and things to include!

1. Physical rituals that linger

You've already mentioned a couple of these, which is great! Even if they don't speak much, tiny, unconscious rituals can convey the message. Here are some examples:

When she visits, he always leaves the gate unlocked for her, no one else

She instinctively checks his pantry and stocks up his favourite item without a word

They still say things like "drive safe" or "eat something"

It's important to show the effort that they still put in and how they choose to still honour these even when it feels difficult or life is getting in the way. Loyalty is most visible when it would be easier to let go.

2. Ghosts of old habits

Even after their relationship has changed, they might still have lingering, unconscious behaviours that they continue to do, whether it be out of love, memory, or muscle memory. Examples:

He still subconsciously reaches for her hand sometimes

She folds his sweaters the "right" way whenever she visits

He feels compelled to text her when something funny happens

They still argue like spouses over dumb things (like what goes in the fridge and what doesn't)

3. Protective loyalty

This is when your characters still feel the need to defend, respect, and stand up for one another. Even with the awkwardness, there might still be moments where no one else is allowed to criticise the other—like him snapping sharply if someone insults her in any way, or her glaring down someone who disrespects him as a father.

4. Private symbols

You already have a few of these, too (the earrings she still wears, the art gallery he won't let anyone enter). Including private symbols like this (objects, places, routines, habits, etc.) that carry meaning between them is another great way to portray the feelings they still have for each other, even if they're not publicly acknowledged or spoken of.

5. Awkward attempts at change

This awkwardness comes from the fact that they know they aren't together anymore, but can't stop subconsciously behaving otherwise. These are moments where your characters try to reclaim their independence, update their old routines, build new lives without each other, or prove to themselves and others that they've moved on.

Adding in scenes and elements like this humanise your characters and can add more depth and emotion to your narrative.

---

Overall, have their interactions show (reluctant) restraint, deep familiarity, and bittersweetness. Hope this helped!

#ask#writeblr#writerblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writing tropes#writers on tumblr#writers of tumblr#writerscommunity#on writing#deception-united

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello everyone! hope all of you are safe and overall doing well ❤

i know i haven't been the best with getting to asks in the past couple months, which i'm so sorry about—i got overwhelmed with a few things that came up and had some drafts get deleted repeatedly, which was a bit of a setback. i'll do my best to get to everything in the next couple weeks, hopefully not too late for your stories.

ask box is open and DMs welcome as always!

#text post#writeblr#writing#writerblr#creative writing#writing tips#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#deception-united

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

just came across this when looking back at some old posts. DID NOT KNOW THIS thank you so much (very belatedly) for sharing

Let's talk about story structure.

Fabricating the narrative structure of your story can be difficult, and it can be helpful to use already known and well-established story structures as a sort of blueprint to guide you along the way. Before we delve into a few of the more popular ones, however, what exactly does this term entail?

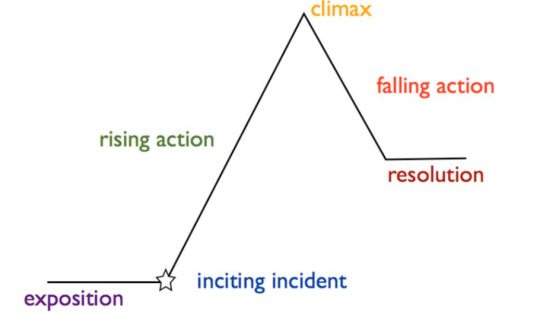

Story structure refers to the framework or organization of a narrative. It is typically divided into key elements such as exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, and serves as the skeleton upon which the plot, characters, and themes are built. It provides a roadmap of sorts for the progression of events and emotional arcs within a story.

Freytag's Pyramid:

Also known as a five-act structure, this is pretty much your standard story structure that you likely learned in English class at some point. It looks something like this:

Exposition: Introduces the characters, setting, and basic situation of the story.

Inciting Incident: The event that sets the main conflict of the story in motion, often disrupting the status quo for the protagonist.

Rising Action: Series of events that build tension and escalate the conflict, leading toward the story's climax.

Climax: The highest point of tension or the turning point in the story, where the conflict reaches its peak and the outcome is decided.

Falling Action: Events that occur as a result of the climax, leading towards the resolution and tying up loose ends.

Resolution (or Denouement): The final outcome of the story, where the conflict is resolved, and any remaining questions or conflicts are addressed, providing closure for the audience.

Though the overuse of this story structure may be seen as a downside, it's used so much for a reason. Its intuitive structure provides a reliable framework for writers to build upon, ensuring clear progression and emotional resonance in their stories and drawing everything to a resolution that is satisfactory for the readers.

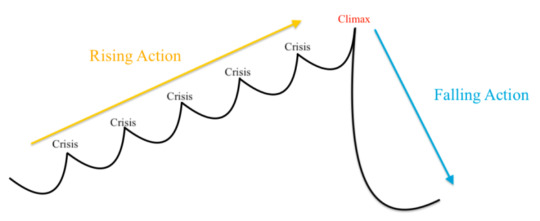

The Fichtean Curve:

The Fichtean Curve is characterised by a gradual rise in tension and conflict, leading to a climactic peak, followed by a swift resolution. It emphasises the building of suspense and intensity throughout the narrative, following a pattern of escalating crises leading to a climax representing the peak of the protagonist's struggle, then a swift resolution.

Initial Crisis: The story begins with a significant event or problem that immediately grabs the audience's attention, setting the plot in motion.

Escalating Crises: Additional challenges or complications arise, intensifying the protagonist's struggles and increasing the stakes.

Climax: The tension reaches its peak as the protagonist confronts the central obstacle or makes a crucial decision.

Swift Resolution: Following the climax, conflicts are rapidly resolved, often with a sudden shift or revelation, bringing closure to the narrative. Note that all loose ends may not be tied by the end, and that's completely fine as long as it works in your story—leaving some room for speculation or suspense can be intriguing.

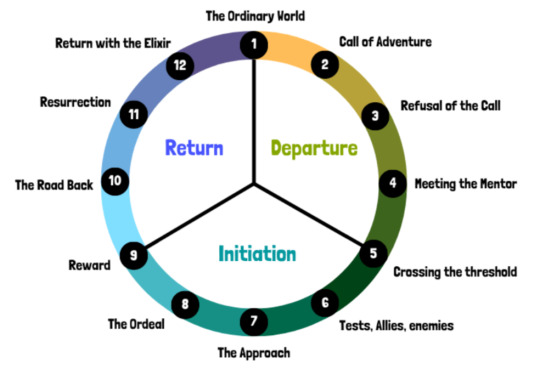

The Hero’s Journey:

The Hero's Journey follows a protagonist through a transformative adventure. It outlines their journey from ordinary life into the unknown, encountering challenges, allies, and adversaries along the way, ultimately leading to personal growth and a return to the familiar world with newfound wisdom or treasures.

Call to Adventure: The hero receives a summons or challenge that disrupts their ordinary life.

Refusal of the Call: Initially, the hero may resist or hesitate in accepting the adventure.

Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a wise mentor who provides guidance and assistance.

Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their familiar world and enters the unknown, facing the challenges of the journey.

Trials and Tests: Along the journey, the hero faces various obstacles and adversaries that test their skills and resolve.

Approach to the Inmost Cave: The hero approaches the central conflict or their deepest fears.

The Ordeal: The hero faces their greatest challenge, often confronting the main antagonist or undergoing a significant transformation.

Reward: After overcoming the ordeal, the hero receives a reward, such as treasure, knowledge, or inner growth.

The Road Back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, encountering final obstacles or confrontations.

Resurrection: The hero faces one final test or ordeal that solidifies their transformation.

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world, bringing back the lessons learned or treasures gained to benefit themselves or others.

Exploring these different story structures reveals the intricate paths characters traverse in their journeys. Each framework provides a blueprint for crafting engaging narratives that captivate audiences. Understanding these underlying structures can help gain an array of tools to create unforgettable tales that resonate with audiences of all kind.

Happy writing! Hope this was helpful ❤

#veeeery long post but worth reading#reblog#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#story structure#on writing#writers on tumblr#writers of tumblr#writerscommunity#writing community#add tags

550 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I'm currently writing two first-person books, and I need help as one of them for almost the entirety of the first chapter it's only the MC so I'm stuck writing a lot of 《 I 》 and I'm trying to avoid it... But it's hard when it's all first-person POV. Could I get any help with this? I'm asking for advice if that helps clarify anything.

I'm sorry if this goes against anything, and if it sounds offensive, I'm very sorry...😔

Hi, thanks for asking! Here are some tips that might help out a little.

1. Make the world do the work.

Instead of leading every sentence with "I," try leading with the environment. You'll still be experiencing the world through the character's senses, but the focus shifts so that the reader feels more immersed rather than just watching the character observe it, as well as reducing the use of "I" in your writing.

Instead of: 'I walked through the forest. I could hear birds singing. I felt the damp earth beneath my boots.' Try: 'Branches swayed overhead, birds sang somewhere beyond the moss-covered path, and wet earth clung to my boots.'

2. Thoughts without labels

One of the best parts of writing in first-person is the ability to show internal monologue without constantly saying 'I thought' or 'I wondered' or tags of that element—you can just state the thoughts as part of the narrative rather than announcing that your narrator is thinking. If it’s first-person and we’re in their head, the reader will know.

3. Sentence structure variety

If you feel like you're using "I" too much, the problem may lie in stacking sentences in the same structure rather than overuse of the word. Adding in variation will help keep the flow more dynamic and make it seem less repetitive or robotic.

Instead of: 'I took a deep breath. I couldn't believe it. I was shocked.' Try: 'I drew in a sharp breath, disbelief flickering through me as I stood, frozen in shock.'

4. Body language

You can use body language, sensory reactions, and behavior to replace direct declarations of emotion, and let your readers feel it rather than being told straight out. Consequently, this will also make your writing more descriptive and immersive.

Instead of:' I was nervous.' Try: 'My hands wouldn’t stop twitching. The room suddenly felt two sizes too small.'

5. Zoom out sometimes

Your narrator doesn't have to be narrating every second of their life—rather, they can remember, summarise, or observe in a more omniscient way. By zooming out like this, you're describing the space, mood, and moment and showing your character's feelings through the environment instead of stating them directly.

Instead of:' I sat on the edge of my bed. I tried to breathe, but it felt too hard.' Try: 'The room hadn’t changed, but everything in it felt wrong. The walls leaned too close, the air suffocatingly thick with unsaid thoughts.'

-

The bottom line is, writing in first-person isn't about reporting events, but about letting your reader experience them, filtered through your character's personality, humour, wounds, and overall worldview. And keep in mind that you're not doing anything wrong by having a lot of "I" in your writing—writing in first-person entails it. Rather than aiming to banish it or reduce your usage of it, try to find more ways to add variation in your writing and sentence structure to keep it fresh and immersive for your readers.

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writers on tumblr#writers#on writing#writing community#writerscommunity#deception-united

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, my story's protagonist has an older sister who is a very untrustworthy and unreliable narrator who twists the truth to fit her reality or lies a lot. One of these lies is about their parents. The sister claims that their parents always fought and that their father was abusive towards their mother.

In reality, while their parents did argue, they never got into any divorce-level fights or disagreements. Even if her father does raise his voice, he immediately regrets his actions and apologizes.

How do I show that the sister is not being truthful?

Thanks for asking! Here are some tips.

1. Memory inconsistencies

One way to convey this is to make her story change in small ways every time she tells it. Memory is fluid, but liars often can't keep track of their own fabrications. One time she might say "Dad broke a plate in rage," another time she says he punched a hole in the wall. These inconsistencies may be unnoticeable at first, but when they line up they can create a growing sense of suspicion.

Have her describe the parents' fights in wildly exaggerated terms, like "they used to scream at each other every night," but when the protagonist (or even side characters) remember these moments, they might be much quieter, more normal arguments. Or you could show flashbacks to make the point, like of a scene the parents are arguing about something like finances, raising their voices for a second, but then calming down.

Keep in mind that memory can be hazy and emotional, so even flashbacks can be a little fuzzy—but the overall emotional tone should feel healthier than the sister paints.

2. Use other characters' reactions

Sometimes the best proof that something’s off is how other people react—maybe another sibling frowns when she speaks or an old neighbour fondly remembers the parents being affectionate. Quiet, understated counterpoints like this might not be obvious upon first glance, but the reader will likely be able to put it all together as the story goes on by comparing narrations.

3. Build the lie into her character

Think about why she lies about this. Is it protection? Resentment? Manipulation? Trauma? Showing that she needs to warp reality, whether to feel better, to play victim, or hide her own guilt, makes her lies character-driven, not just plot devices or confusing contradictions. Readers don’t need to like her lies, but this will give a reason to understand that they are a survival mechanism rather than being random.

4. Body language

This might not be visible when the narrative is from the sister's POV, but consider her body language when she talks about it. You can hint that she's trying to believe it herself or that she needs this lie to pass through making it intense, like she's too eager to convince others.

Ex: wringing hands, fake tears that come a little too fast, getting mad if someone questions her version, etc.

She may also overact when she recounts these fights, like dodging eye contact, fidgeting, grinning too widely, or acting too confident as if to compensate or make her words more believable.

5. Catching her lying about other things

Though the reasons for her lie may differ, a person who lies perpetually about one thing is also likely to twist other small things here and there as well. If readers already notice her doing things like claiming someone said something they didn't or playing the victim when it's not justified, they'll naturally question her bigger claims without you needing to say it or make it explicit.

6. Overcomplication

Something to keep in mind is that sometimes when liars are pressed, they may overcomplicate their stories to sound more convincing. If you want, you could have the sister’s stories get more and more dramatic the more she’s doubted, like she’s trying to "prove" it instead of just telling the truth.

7. Contrast her stories with specific, concrete memories

This point depends on how obvious you want to make her lies—but one way you could go about it is not to immediately contradict her when she makes claims about them having fought all the time, but to let the protagonist or other characters naturally recall memories that suggest otherwise. Providing memory as proof rather than direct denial will get readers to catch on.

8. Trust your reader

You don't have to explain the lie too early or correct her in a big dramatic reveal—let it be a sort of creeping realisation. Remember, your readers absolutely have the ability to catch on and connect the dots themselves.

-

Hope this helped!

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writers on tumblr#writers of tumblr#writerscommunity#deception-united

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do I write about a character that does gymnastics? I don't know a single thing about practices, how things are scored, and overall how to describe it.

Hi, thanks for asking! I don't know much about gymnastics myself, unfortunately, but here's some information I gathered (feel free to correct me or add on).

1. You don't need to explain the whole sport.

Your readers aren’t expecting a technical manual—they’re looking for the feeling. When you write about your character, you’re not writing about scoring rubrics or competition regulations (unless your plot absolutely demands it); rather, focus on what it feels like rather than what it officially is.

Ex: Her body arcing through the air, the rush of the landing, the tiny breath she holds before a back handspring, etc.

Instead of complicated terms and things some of your readers won't fully understand or connect to, make it more centred around the motion and emotion.

2. Practices (repetition & drills)

Gymnastics practices can be long and grueling. Athletes drill basic moves over and over to perfection (like handstands, cartwheels, backbends). They'll work on strength (pull-ups, pushups, core workouts), flexibility (splits, bridges), and techniques (like perfecting the way they stick a landing).

A practice could involve:

Warming up (light jogging, stretching)

Conditioning (core, arms, legs)

Drilling basic skills

Working on routines (choreographed sequences for competition)

3. Competitions

Gymnasts usually compete in four events if they’re doing artistic gymnastics (the most common form):

Vault (run, jump, flip off a vaulting table)

Bars (swinging between two uneven bars)

Beam (a 4-inch-wide balance beam)

Floor (a tumbling and dance routine on a large mat)

They're judged on:

Difficulty (how hard the routine is)

Execution (how well they perform it—points are taken off for wobbles, falls, or bad form)

But again, keep in mind that you usually won't need a real judge’s scorecard for your narrative. The point isn't to have a full manual on gymnastics for your reader, but the character, inner conflict, motivations, goals, and plot. For example, a fall usually costs a lot of points, but the focus of your story might be to show your character recovering after a mistake like this rather than earning a perfect score.

4. Describing movement

Gymnastics is full of sharpness, grace, power, and control. When you describe a move, don't get bogged down in trying to name every twist. Instead, use verbs that sound dynamic (vaulted, twisted, snapped, launched, spun, lunged, landed, crashed).

Ex: 'She hurled herself into the air, twisting once, twice, before her feet slammed into the mat with a jolt that echoed through her bones.'

Even without fancy jargon the reader will have to look up or ignore, using familiar language anyone can understand can help them feel it, even if they can't personally relate.

5. Emotional stakes

Any story needs internal conflict and a emotion. Consider what your main character is going through—is she chasing approval? Fighting fear? Battling her own body? Gymnastics as a sport demands a lot, like bravery, pain tolerance, and perfectionism. Use this to fuel your character arc. Maybe missing a trick feels like failing her whole family, for example.

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character development#gymnastics#writers on tumblr#writer help#writerscommunity#deception-united

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I saw the post of how to write a father daughter crumbling relationship, and I wanted to ask how you write a father daughter relationship that’s already broken? the way i’m going with my story is she ran away at one point and he’s evil. She ends up seeing him again years later, has to go against him, and even fight him at some point to take him down. They’ll probably never fix the relationship ever, but I still want to have little pieces where there’s that ping of like “that’s my father”yk? I might also add a plot that he now has another daughter too, I hope this is not confusing, but do you think you could help with some tips? :)

Hi, thanks for asking! Here are some tips and ideas.

1. Start with echoes instead of flashbacks.

You don't need to info-dump their entire backstory right at the start. Try using emotional echoes instead—like small memories, half-formed thoughts, or sensory triggers. A particular smell or sight could remind her of her father, especially if it's from what she remembers he was like before their relationship broke or how she wishes it could be. This creates emotional disruption and can help the reader feel the dissonance between who he was and who he became without having to include pages of detailed reminiscing.

2. Focus on what's missing.

Because the relationship is already shattered, a lot of the emotional weight will come from absence. She's not necessarily mourning what happened, but what never did, like a birthday he didn't show up for, the safety she should've felt, things she wishes she had but was never given.

3. Resenting the pieces that still care

Rather than complete hatred, have your protagonist hate that she still feels something. Add in the odd confusing flicker of warmth, nostalgia, or longing that'll make her seem more real instead of just hardened or revenge-focused.

Ex: Noticing a trait she shares with him, flinching at the way he says her name, etc.

4. Mirrored behaviour

You can have her catch herself doing something he does, no matter how subtle (tilting her head the same way when thinking, using a fighting tactic he always did), and it sickens her. This can add inner conflict, especially when she starts questioning 'what else did I inherit?'—maybe she'll think that no matter how much she ran, some part of him is in her.

5. Make the father human.

Villainous as he is, he still is human; he should be terrifying because he's believable. He might believe what he did was necessary, show that he cares in twisted ways, or mourn losing her while refusing to admit that he was wrong. This contradiction can add depth—and as twisted and cruel as he may be, remembering the tiny things like a lullaby or a joke he used to say may haunt her. Though they don't nearly redeem him, they can be the reasons it hurts to fight him.

6. 2nd daughter

I love that you added a second daughter—it can give rise to more emotions and further development. Your protagonist might feel jealous, protective, disgusted. Maybe the new daughter thinks he's a great father (if he learnt from his mistakes?); or maybe he's worse than ever.

This new dynamic can go to show who he is now and force your protagonist to question things. She might be a mirror or a threat: if he's softer with her, maybe your protagonist is furious but also jealous, then ashamed of that jealousy; but if he's using her, too, she might want to save this sister—not necessarily out of love, but out of revenge ('I won't let him ruin her like he did me').

7. Confrontation

When she finally faces him, make it more than just a boss fight. There are going to be emotional grenades from their broken bond, even as they fight (a flicker of hesitation, a glance, a choice not to kill when they could have).

8. Ending

You don't need to end with reconciliation—just recognition. Not all wounds heal, and that's okay. Let the narrative acknowledge the connection without having to fully repair it. Sometimes redemption arcs aren't necessary for the story to have a good ending.

Hope this helped!

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character development#writer help#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#deception-united

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey everyone! i've been locked out of my account since around the start of april. so sorry to all asks who've gone unanswered—i'll be getting to those as soon as i can. ask box is open and DMs welcome as always ❤

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

yes

How do you write a character who is mature for their age?

My characters are all between 18-14 and act a lot more mature than their age due to how they grew up? There are about 10+ of them, and how do I make them act grown up but still be kids at the same time, while still holding leadership positions.

Hi, thanks for asking! I love this question—you'll find this in a lot of narratives, and if your characters have grown up in harsh or demanding environments, it makes sense that they’d be more responsible, insightful, or emotionally resilient than their peers; but it's important for the readers to still feel that they're young. Here are some tips.

Writing Mature Young Characters

1. Maturity through experience, not just speech

Your characters might sound older because of what they've been through, not just because they use fancy vocabulary or speak in deep philosophical metaphors. This maturity could come from:

The way they handle stress and responsibility

Their ability to assess situations logically rather than emotionally (though they’ll still have emotional moments)

The way they interact with adults (sometimes as equals, sometimes with hidden insecurity)

For example, a teenager leading a resistance group might have a sharp strategic mind, but that doesn’t mean they don’t feel the pressure of failure or secretly wish someone else could handle it. Let that complexity show.

2. Give them moments of being kids.

No matter how much responsibility they carry, they’ll still have cracks in their armour that shows their youth. Examples:

Stupid little habits (chews on their sleeves, obsessed with collecting something odd, still secretly sleeps with a stuffed animal, etc.)

Impulsive moments where emotions override logic (storming off, making reckless decisions, blurting out feelings they later regret)

A desire for normalcy—maybe they joke about things they missed out on or envy people their age who don’t have the same burdens

Even the most hardened of warriors is still a kid (in the context of this ask) and might make inside jokes, argue over dumb things, or mess around when the stakes aren’t high. Or they might make tactical decisions with the confidence of an adult, but forget to eat, sleep, or take care of themselves like a kid.

3. Leadership that feels earned, not forced

If your teens are in positions of power, show why they’re there. Are they the only ones willing to take charge? Are adults absent, dead, or untrustworthy? Did they prove themselves through skill or sheer survival? For example, you can make it feel:

Respected, not convenient—others follow them because they believe in them, not just because the story needs them in charge.

Hard-earned—maybe they had to fight for authority, prove themselves, or take on responsibilities that no one else wanted.

Lonely—leadership is isolating, especially for teens who are aware they’ve lost the freedom of childhood.

At the same time, they might struggle with things like imposter syndrome or self-doubt.

4. Age-appropriate emotional reactions

Even if they talk or act like adults, their emotional responses should remind readers that they aren't. They might:

Feel things too intensely (like anger, grief, and joy to the point of being consuming or reckless), like snapping in frustration when they’re stressed instead of handling things with full adult restraint

Have a skewed sense of consequences (thinking they’re invincible, or believing failure means everything is doomed)

Struggle with emotional control, like bottling everything up until they explode or lashing out because they don’t have healthy coping mechanisms

Maybe they can negotiate peace between feuding clans but are completely helpless when dealing with personal rejection; or they can keep calm under fire but cry when no one is watching. Things like this not only add depth to your characters, but remind readers that they're still babies.

5. Mature, but not omniscient

For instance, a fifteen-year-old might be commanding an army in battle but have no idea how to comfort a crying friend. Examples:

A teenager who had to raise their siblings will have strong leadership and nurturing skills, but might not know how to handle romance or peer friendships well

Still longing for normalcy in ways they don’t admit

Thinking they know everything, but getting blindsided by something outside their experience

6. Let them have growth arcs.

One of the best ways to balance maturity and youth is to show them learning. Maybe they act like they know everything, only to be humbled by a mistake; or assume they have to be strong all the time, but later realise they need help too and it's alright to ask for it. This'll remind the audience that while they may be wise beyond their years, they are still growing.

7. Inexperience

As many skills and responsibilities they may have, a teenager will likely still be inexperienced. For example:

They need to make difficult decisions since they're in leadership positions, but still struggle with the weight of it

Don’t yet have the emotional distance to detach from losses

Competent in battle but still hesitate before killing

8. Speech, humour, & interests

A mature teen might be more articulate and well-spoken, but they won’t sound like a university professor. They might still joke, use slang, or get snarky when comfortable.

It's also important not to forget about personal hobbies and random little things they get excited about. They may be world-weary, but they can still be dorky about their interests.

9. They might not have all the power.

Even if they hold leadership positions, adults might still underestimate them or try to manipulate them; they might be technically in charge but constantly fighting to be taken seriously, or believe they have control over their own lives only to realise they’re still at the mercy of the systems around them.

---

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous

209 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you write a character who is mature for their age?

My characters are all between 18-14 and act a lot more mature than their age due to how they grew up? There are about 10+ of them, and how do I make them act grown up but still be kids at the same time, while still holding leadership positions.

Hi, thanks for asking! I love this question—you'll find this in a lot of narratives, and if your characters have grown up in harsh or demanding environments, it makes sense that they’d be more responsible, insightful, or emotionally resilient than their peers; but it's important for the readers to still feel that they're young. Here are some tips.

Writing Mature Young Characters

1. Maturity through experience, not just speech

Your characters might sound older because of what they've been through, not just because they use fancy vocabulary or speak in deep philosophical metaphors. This maturity could come from:

The way they handle stress and responsibility

Their ability to assess situations logically rather than emotionally (though they’ll still have emotional moments)

The way they interact with adults (sometimes as equals, sometimes with hidden insecurity)

For example, a teenager leading a resistance group might have a sharp strategic mind, but that doesn’t mean they don’t feel the pressure of failure or secretly wish someone else could handle it. Let that complexity show.

2. Give them moments of being kids.

No matter how much responsibility they carry, they’ll still have cracks in their armour that shows their youth. Examples:

Stupid little habits (chews on their sleeves, obsessed with collecting something odd, still secretly sleeps with a stuffed animal, etc.)

Impulsive moments where emotions override logic (storming off, making reckless decisions, blurting out feelings they later regret)

A desire for normalcy—maybe they joke about things they missed out on or envy people their age who don’t have the same burdens

Even the most hardened of warriors is still a kid (in the context of this ask) and might make inside jokes, argue over dumb things, or mess around when the stakes aren’t high. Or they might make tactical decisions with the confidence of an adult, but forget to eat, sleep, or take care of themselves like a kid.

3. Leadership that feels earned, not forced

If your teens are in positions of power, show why they’re there. Are they the only ones willing to take charge? Are adults absent, dead, or untrustworthy? Did they prove themselves through skill or sheer survival? For example, you can make it feel:

Respected, not convenient—others follow them because they believe in them, not just because the story needs them in charge.

Hard-earned—maybe they had to fight for authority, prove themselves, or take on responsibilities that no one else wanted.

Lonely—leadership is isolating, especially for teens who are aware they’ve lost the freedom of childhood.

At the same time, they might struggle with things like imposter syndrome or self-doubt.

4. Age-appropriate emotional reactions

Even if they talk or act like adults, their emotional responses should remind readers that they aren't. They might:

Feel things too intensely (like anger, grief, and joy to the point of being consuming or reckless), like snapping in frustration when they’re stressed instead of handling things with full adult restraint

Have a skewed sense of consequences (thinking they’re invincible, or believing failure means everything is doomed)

Struggle with emotional control, like bottling everything up until they explode or lashing out because they don’t have healthy coping mechanisms

Maybe they can negotiate peace between feuding clans but are completely helpless when dealing with personal rejection; or they can keep calm under fire but cry when no one is watching. Things like this not only add depth to your characters, but remind readers that they're still babies.

5. Mature, but not omniscient

For instance, a fifteen-year-old might be commanding an army in battle but have no idea how to comfort a crying friend. Examples:

A teenager who had to raise their siblings will have strong leadership and nurturing skills, but might not know how to handle romance or peer friendships well

Still longing for normalcy in ways they don’t admit

Thinking they know everything, but getting blindsided by something outside their experience

6. Let them have growth arcs.

One of the best ways to balance maturity and youth is to show them learning. Maybe they act like they know everything, only to be humbled by a mistake; or assume they have to be strong all the time, but later realise they need help too and it's alright to ask for it. This'll remind the audience that while they may be wise beyond their years, they are still growing.

7. Inexperience

As many skills and responsibilities they may have, a teenager will likely still be inexperienced. For example:

They need to make difficult decisions since they're in leadership positions, but still struggle with the weight of it

Don’t yet have the emotional distance to detach from losses

Competent in battle but still hesitate before killing

8. Speech, humour, & interests

A mature teen might be more articulate and well-spoken, but they won’t sound like a university professor. They might still joke, use slang, or get snarky when comfortable.

It's also important not to forget about personal hobbies and random little things they get excited about. They may be world-weary, but they can still be dorky about their interests.

9. They might not have all the power.

Even if they hold leadership positions, adults might still underestimate them or try to manipulate them; they might be technically in charge but constantly fighting to be taken seriously, or believe they have control over their own lives only to realise they’re still at the mercy of the systems around them.

---

Hope this helped! Happy writing ❤

Previous | Next

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writers on tumblr#writer help#character development#writerscommunity#writing community#story writing#on writing#deception-united

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's talk about writing dual POVs.

Writing a novel with a dual point of view where two different characters share the role of narrator can add depth, tension, and complexity to your story, but it also comes with its own set of problems and challenges. Like, how do you ensure clarity between perspectives? How do you keep both characters engaging? And most importantly, how do you make both narratives feel like parts of the same novel instead of two separate stories? Here are some tips and strategies to consider, before and when writing.

1. Ensure both POVs are necessary.

A dual POV should serve the story, not exist just because it seems interesting. Before committing to this structure, ask yourself:

Could the same story be told just as, or more, effectively from just one perspective?

Do both characters bring viewpoints that are unique and essential to the plot? What does this character’s POV add that we wouldn’t get otherwise?

Does each POV contribute to the novel’s themes, conflicts, or emotional depth?

Does it move the plot forward, or is it just there because I like this character?

If the answer isn’t an easy 'yes,' reconsider whether both POVs are truly needed. For example, in a romance novel, it might be better to only include one POV, since knowing there are feelings from both sides can take away tension and make it boring for the reader.

2. Choose a primary protagonist.

Even though you're going to be featuring two points of view, it’s essential to have one central character who anchors the story. This character serves as the thematic and emotional core of your book. Consider:

Which character’s perspective starts the story?

Which character’s perspective ends it?

Who undergoes the most significant transformation?

While both POVs should be compelling, having one clear primary character ensures your narrative remains cohesive.

3. Make each POV distinct.

Readers should be able to identify whose perspective they’re in without needing a chapter heading to tell them (although this is helpful and I do recommend including an indicator like this). You can differentiate this through:

Voice & tone: Their word choices, speech patterns, and internal thoughts should reflect their unique personalities. (See my post on character voices for more tips on this!)

Observations & focus: What each character notices and how they perceive the world will differ based on their backgrounds and biases. What details do they focus on? How do they process emotions? For example, a noble-born strategist will notice different things than a street thief. Sentence structure & style: Ties back to voice & tone—a poetic, introspective character might have longer, flowing sentences, while a blunt, action-driven character may have short, clipped phrasing.

**If you can open to a random page and easily recognise the character’s voice, you’ve done it right.

4. Interweave the two arcs effectively.

Both characters should have distinct yet interconnected arcs—even if they don't meet or interact until later on, or at all, their stories should be able complement or contrast each other in a way meaningful and comprehensible for the reader. Examples:

Parallel arcs: The characters face similar struggles but react differently (shows contrasts).

Intertwining arcs: Their paths cross at key moments & affect each other’s journeys.

Foil dynamics: One character’s success may mean the other’s failure—builds tension and stakes.

5. Smooth transitions

Switching between perspectives should feel natural, not jarring. Consider:

Consistent switching: Like alternating every chapter or at key turning points, or making one character dominant (the main focus) and the other occasional (slipping into it when necessary).

Strategic cliffhangers: Ending one POV on a suspenseful moment can keep readers engaged through the shift (though be careful not to make it so that the reader is skimming through one POV just to get to another).

Mirrored/contrasting scenes: A reveal in one POV can recontextualise a previous scene from the other.

6. Avoid head-hopping.

This is when you suddenly switch between characters’ thoughts in the same scene without a clear break. This can be jarring and pull readers out of the story.

Bad example: Lena glared at him. She was furious. Why didn’t he understand? Jonah sighed. He wished she would just listen.

You can't tell whose head we're in, and even if it was indicated at the start of the chapter, it makes it confusing and frustrating.

7. Build suspense

A well-timed POV switch can escalate tension rather than just pass the baton. Examples:

Character A is walking into a trap; meanwhile, Character B is on the other side of the city, knowing but unable to warn them (creates dread).

One character’s assumptions might contradict reality. (For example, a spy might believe their cover is intact, but another POV reveals they’ve been exposed.)

Character A misinterprets Character B’s actions as betrayal. Switching to B’s POV clarifies their true, but hidden, motives (creates emotional whiplash).

8. Deeper character exploration

Dual POVs can let readers experience both sides of a relationship, rivalry, or power struggle in ways a single POV can't. Examples:

Character A sees themselves as a hero, but Character B’s POV reveals their arrogance (unreliable narration).

Different emotional reactions—the same event might be tragic for one but a relief for another.

Common Pitfalls

Dual POVs might not always be appropriate for your specific narrative, and could:

1. Remove tension.

I briefly mentioned this, but one risk of dual POVs is reducing suspense, especially in genres like romance or mystery. If readers see both sides of a conflict, they might lose the uncertainty that drives engagement. However, you could try:

Using unreliable narrators

Keeping certain information hidden from one POV

Ensuring there’s still conflict and misunderstanding between the characters

Switching between past and present

Keeping one POV until the climax or for a specific plot twist, which can be revealed through a different POV

2. Break story flow.

If one character’s arc lags behind the other’s, readers may get frustrated when switching perspectives. Ensure each POV maintains momentum and contributes to the overarching plot.

3. Make readers favor one character.

If readers strongly prefer one POV, they may skim or disengage during the other. To avoid this, make sure both are equally compelling, both characters have stakes that feel urgent and meaningful, and each has their own distinct emotional arc that readers will be equally invested in.

4. Make it redundant.

If both characters are just retelling the same events with minor differences, the second POV becomes unnecessary. To avoid this, use POV shifts to enhance the story, not just repeat it. You can use the second POV to:

Show what’s happening when the other character isn’t present

Reveal secrets, misunderstandings, or unreliable narration

Build dramatic irony (let the reader know something one character doesn’t)

Happy writing!

Previous | Next

#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writing techniques#character development#writing community#on writing#writers#writers of tumblr#writerscommunity#dual pov#deception-united

212 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! weird question, but how do i write my make character receiving… ahem… oral?

i need something that sounds better than the typical “it felt good, he moaned”

sorry if this was weird!!!!!!!!!!

hi, thanks for asking! writing intimate scenes like this can be hard, and it’s easy to fall into clichés or make it sound mechanical. here are some quick tips.

focus on sensation. describe how it feels rather than flat-out stating how it's making him feel, if that makes sense

breath hitching, heat coiling low in his stomach, white-hot pleasure, etc.

body language > direct statements. instead of saying things like "he moaned," show his reaction.

does he tense up? does his grip tighten on the sheets or their hair? does his breath stutter?

bottom line is, focus on physical reactions to convey what you want.

i do have a previous post with more in-depth tips that you might find helpful, so feel free to take a look at that as well! here:

❤

#ask#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing resources#creative writing#writing smut#deception-united

80 notes

·

View notes