#Osanyin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My Ancestry Discovery

I recently received my results for my ancestry DNA test. One of the main reasons is because I wanted to be able have a tie to ancestrial work. My family on my mother's side was told we are indigenous, but that isn't enough information to go on. Even if I knew what tribe exactly etc, it is still closed practice and I have no one to teach me.

The information I received shows my ancient ancestors were mainly in Nigeria and Camaroon which means they most likely practiced Yoruba or Vudoun. In order to practice and work with the Orisha (the Yoruba "deities"), I would have to be initiated, which I cannot be. I have instead chosen to devote a part of my life to recognizing them (though they may not recognize and work with me in return due to me not being initiated).

The Orisha I found that stood out to me are Orunmila, Osanyin, Yemoja, and Oya.

Orunmila is the Orisha of knowledge, wisdom, divination and prophecy.

Osanyin is the Orisha of herbs, healing, magic and protection.

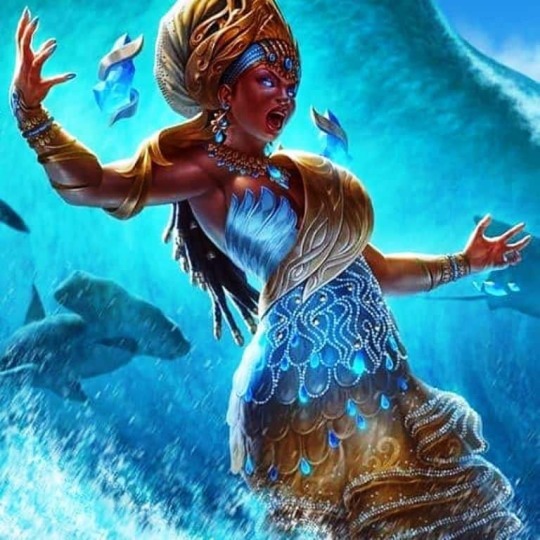

Yemoja is the Orisha of motherhood, water, moon and creation.

Oya is the Orisha of winds, change, revolution, and death/rebirth.

These are areas of my current practice that I feel drawn to. Does this mean I practice the Yoruba religion? No, I can't perform the rites or rituals of Yoruba religions, but I can incorporate those attributes of the Orisha into my life as a connection to my ancestors who did practice.

The first thing I did was to learn about the practices in the Yoruba religion online and in books (waiting for the books I requested to reach my library). I is great to read how connected to the energy of the earth and universe this practice is. That is how I found the Orisha that I gravitated toward.

Now I understand that all of this is more than likely on the surface. Like how a person might gravitate towards a celebrity, but that celebrity doesn't even know they exist. The person buys merchandise with the celebrity's face on it and quotes things they say, but ultimately it's for them as a person because there really is no connection to the ACTUAL celebrity. -- I get that --

When I get excited about things, I like to create. So after researching, I created divination cards with the Orisha I liked. These are for me. Unless I am ever initiated, I would not sell them for others to use without the understanding that I am not a practicing Yoruba initiate. The cards, though they have representations of the Orisha, really channel my own energy and connection with the elements/lunar energy.

I will not write about them on my @stardustnsorcery blog since this is personal subject and that blog is a business blog.

I will write more about the deck soon, but for now I am happy to have found something in my ancestry that connects me to more that just living in America over the last 300 or so years.

#ancestry#ancestors#dna#dna test#lineage#yoruba#voodoo#vodou#vodoun#orishas#yemoja#orunmila#oya#Osanyin#yemaya#divination#nigeria#camaroon#witchblr#witch#witchcraft#tarot#tarot cards

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#akoko #egbe #osanyin #iyaami #ifa https://www.instagram.com/p/CnUCY3Iu1lr/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

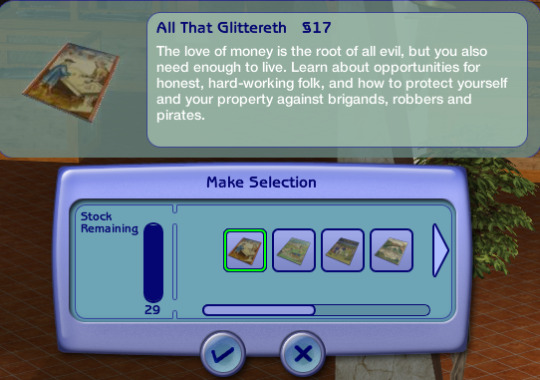

Followers gift part 2: Medieval magazines!

So, magazines didn't really exist until the 18th century. But before that, there were cheap, widely available publications - broadsides, chapbooks, pamphlets - that covered a wide range of subjects like news, true crime, political commentary, entertainment (some ballads were literally just existing poems set to music) and news-of-the-weird subjects like witchcraft and prophecies and that woman in England who claimed she kept giving birth to rabbits, and so on. A lot of the same subjects covered by Sims 2 magazines, in other words. They weren't done in periodical form, but neither are Sims 2 magazines, which are the same week after week.

So that was my initial model. I started out with monochrome woodcut prints from 15th- and 16th-century books and broadsheets, but my early attempt at defaulting the magazines made me think that color might be advisable to make the images easier to recognize at tiny sizes. That led me down a rabbit hole of medieval manuscript art, with the end result that some of the magazines are using art that is far, far too lavish for a mass publication. But it's aesthetically pleasing!

All the magazines have unique interiors, unlike the originals. Most of the text is just Lorem Ipsum (I did include a bit of Chicken Little/Henny Penny in the children's magazine, because one of the illustrations cried out for it) so you're not missing anything by not being able to read it. I used Simlish TrueBadoor for all the text, titles and articles alike.

Man, that floor is pixelated. Hestia and Osanyin need to remodel their foyer. Above you see the entertainment/fashion/sports magazine, with a focus on music. That cover, like many of the others, dates to just a bit before 1500; that was my target zone, though I wasn't super-strict about it. I may well do another default later, with earlier artwork - the Codex Manesse has a lot of good candidates - but I'm a little burnt out right now, which is why I haven't followed through with the hobby magazines.

I replaced the catalog descriptions and titles in the UI, too. Mostly not very period-accurate, except for the judgmental tone towards frivolity and avarice, though I did sometimes use period titles complete with the spelling of the time.

You can see one cover for "All That Glittereth" up above, but it will display a different one when you bring the magazine home; this is normal, if annoying. Maxis for some reason included two money-themed publications and then mixed them up. The UI in use shows a sim buying the magazine in an OFB owned business, but it should look a lot the same in an unowned, NPC-run lot.

And as you can see from the image at the top of the post, I also did a recolor - two recolors, in fact - of this default replacement magazine rack by Motherof70, with my magazine covers. The rack has nine magazines on display and there are only six interest magazines, so I included the alternate cover for Rat Race and two of the hobby magazine covers (or at least early versions of them. I change my mind a lot.)

All the textures are 512 x 512, except for the magazine rack itself, which is 1024 x 1024.

Acknowledgements: These were all built on the template of Lolabythebay's 1920s magazine defaults, and some parts - the page edges and spines - are used barely altered. I adjusted the colors on the spines but kept recycling the underlying graphic. I would never have made sense of the Maxis mapping, let alone been able to increase the resolution of the texture file, without her hard work.

If not for Xia's hobby magazine defaults, I'd have had no idea where to start on looking for the catalog descriptions to replace them.

And I probably wouldn't have thought of doing the magazines at all if not for the default rack.

As for art credit: I've been painstakingly bookmarking all the images used and would be delighted to do a link post, but I don't know how many people would be interested, and this is already getting long.

Magazine replacements: SFS or Box.

Magazine rack recolors: SFS or Box.

Everything is compressorized and seems to work fine for me. Let me know if there are any problems!

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

always found it kind of odd how empty spaces types like using zoroastrian terms so much for their lame erotica, like that's a real ethnoreligious group they're very much still around, imagine a bunch of white people all suddenly developing fetishes for orishas and naming themselves obatala and osanyin and etc

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

50+ African gods names and meanings - Tuko.co.ke

African communities have so many gods and goddesses, and each one has its own role to play in life. Some gods and goddesses are for wealth, war, health, healing, protection, death, evil, creation, and so on. Africans who believe in these gods consider it essential to worship and adore these gods and goddesses to have a good and smooth life.

Even though the larger religions such as Christianity and Islam have made big inroads in the African continent, the African gods and goddesses are still worshipped today. Here are the names of African gods:

African god of war

Ogun - Ogun is a god of war who defends the Yoruba tribe and is depicted wearing armor and red eyes.

Kibuka - Kibuka is the Buganda god of war who secures victory in war by taking the form of a cloud, which hovered above his enemies and rained spears and arrows.

Age-Fon - During the days of wars and battles, Agé was called upon to protect and give strength to the warriors, leading them on which paths to take.

Menhit - The war goddess was believed to advance ahead of the Egyptian armies and cut down their enemies with fiery arrows.

Tano - He is the goddess of war and strife for the Ashanti people.

Apedemak - The Nubian lion-headed warrior god.

Takhar - He is the god of justice or vengeance. He is a demi-god in Senegal's Serer religion and is worshipped to protect believers against injury, bad omens, and abuse.

Maher- Ethiopian god of war

Shango - Shango is the Yoruba god of war and thunder. Oral tradition describes him as powerful, with a voice like thunder and a mouth that spewed fire when he spoke.

Oya - She is the wife of Shango. Oya is a ferocious and protective deity worshipped by the Yoruba. She is the goddess of wind, thunderbolt, and fire.

African god of wealth

Mukasa - He is the brother of Kibuka, the god of war. His main oracular sanctuary was found on an island in Lake Victoria. This god provides rain, food, and cattle.

Oko - Oko is the god of agriculture and fertility. He came to Earth and lived on a small farm, growing some of the most beautiful and delicious fruits and vegetables.

Olokun - Olokun is believed to be the parent of Aje, the orisha of great wealth. He gives great wealth, health, and prosperity to his followers.

Aje - Aje is a traditional goddess of abundance and wealth, often associated with the business of the marketplace in the Yoruba religion.

Oshun - Oshun is a divine being associated with love and fertility, as well as financial fortune in the Yoruba religion.

Ikenga - Ikenga is a personal god of human endeavor, achievement, success, and victory. He is grounded in the belief that a man's power to accomplish things is in his right hand.

Anyanwu - This is the goddess of the sun. She is revered as the goddess that promotes productivity, hard work, and overall positive well-being.

Njoku Ji - This is the guardian deity of yam in Igboland. She is prayed to for productivity during the farming season.

Mami Wata - Mami Wata is famous as the African god of money. The goddess has the power to bestow good fortune and status through monetary wealth.

Wamala - He is the god of wealth and prosperity.

Anayaroli - He is the god of wealth.

Ashiakle - She is a famous goddess of wealth and prosperity in West Africa.

Abena - She is known as the river goddess. Her name is associated with gold, brass, as well as with other wealth symbols.

African god of healing

Agwu - Nsi - This is the god of health and divination. This god is one of the basic theological concepts used to explain good and bad, health and sickness, poverty, and wealth in Igboland.

Osanyin - He is the Yoruba Orisha of herbalism, and he possesses the powers to cure all diseases.

Xu - He is the sky god of the Bushmen in South Africa. Xu is usually invoked during an illness.

Aja - Aja is a powerful healer in Yoruba legend. It is said that she is the spirit who taught all other healers their craft.

Babalu Aye - Babalu Aye is an Orisha often associated with plague and pestilence in the Yoruba belief system. Just as he is connected with disease and illness, he is also tied to its cures.

African evil gods

Amadioha - This is the most popular god in Igboland. He is the god of thunder & lightening. Amadioha is considered a gentleman among the deities and the cruelest when annoyed.

Adroa - Adroa is the god of death with two characters: good and evil. His body is split into two. One half is short and black, which represents evil, while the other half is tall and white and depicts goodness.

Gaunab - He is the Xhosa and Khoikhoi evil god. He is responsible for all misfortune, disease, and death.

Modimo - He represents all the good things. Yet, in the same breath, he had the power to destroy things and bring about natural disasters and devastation.

Ogo - He is the chaos god among the Dogon. Ogo is a horrifically awful trickster god, the embodiment of chaos, and a rebel of horribleness.

African god of death

Anubis - Anubis, the guardian of the dead, is one of the most well-known Egyptian gods. He's mainly depicted as a dog-like figure and leads the dead to Ma'at, where their hearts are weighed.

Ogbunabali - Literally meaning "the one that kills at night." He is known as the death deity. Ogbunabali is known to kill violently.

Gamab - Gamab lives in the sky and directs the fate of mankind. When it's time for someone to die, Gamab gets out his bow and shoots them down with an arrow.

Oya - She is also a goddess of death. Oya is the guardian of the gates of death, as she helps the dead in their transition from life.

African god of creation

Mbombo - Mbombo is the creator god in the mythology of the Kuba people. It is believed that Mbombo was alone, darkness and primordial water covered all the earth. He felt an intense pain in his stomach and then vomited the sun, the moon, and stars.

Olorun - He is the ruler of the sky and the creator of the sun.

Obatala - He is the creator of humans, mountains, valleys, forests, and fields.

Unkulunkulu - He grew from reeds and brought with him people and cattle. Upon his own creation, he created the earth and all of its creatures.

Ra - The sun god arose from Nun, a chaotic body of water that was the only thing in existence. He independently gave birth to Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, the water goddess. They then produced Geb and Nut, the god of the earth and the goddess of the sky, respectively. The first humans to exist were from Ra's tears.

Kaang - He is the creator god of the universe, according to the San people.

Nana - Buluku - Nana Buluku is the mother of Mawu-Lisa and the goddess of creation. She is associated with the sun and moon.

Odomankoma - This is the name Akan-language speakers use to describe the eternal entity who deserves the credit for the work of creation, including creating the concept of trinity.

Modjaji - She is a South African goddess of rain whose spirits live in a young woman's body. The goddess is considered a key figure as she can start and stop the rain.

African god of fertility

Ala - She is the most respected god in Igboland. The goddess represents the earth, fertility, creativity, and morality.

Oshun - She is one of the most powerful of all orishas in the Yoruba religion. She is associated with water, purity, fertility, love, and sensuality.

Asase Ya - Asase Ya is the Earth goddess of fertility of the Ashanti people of Ghana. She is the wife of Nyame, the Sky deity, who created the universe.

Mbaba Mwana Waresa - She is the Zulu goddess of fertility.

Denka - He is the Dinka god of fertility.

Yemaya - She is the childbirth goddess in the Yoruba religion. She is considered the mother of all since she is the goddess of the living ocean.

Who is the most powerful African god?

Oshún is a Yoruba orisha, daughter of Yemoja, a Nigerian river goddess. She is the protector of the family and pregnant women. Oshun is typically associated with water, purity, fertility, love, and sensuality. She is considered one of the most powerful of all orishas in the Yoruba religion. She possesses human attributes such as vanity, jealousy, and spite.

There you have it. A comprehensive list of African gods' names and meanings. With the introduction of larger religions such as Islam and Christianity, the concept of African deity is slowly losing its meaning. However, some ethnic communities still believe in and worship these gods and goddesses even today.

Tuko.co.ke published an article about the list of major religions in Africa. Before the white man came to Africa, the African people had a doctrine. Little is known about the ancient African religions. However, it is a fact that all doctrines have common features such as belief in a supernatural power, the belief of life after death and the beliefs surrounding burial.

Research shows that the majority of citizens in Nigeria and Africa as a whole are devoted Christians. The African continent has a variety of religions practised across all regions. In Africa, religiosity has a big influence on arts, culture, lifestyle and traditions of its people.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

HYPOTHESIS: Assonquer shares an origin with Ossangne (Osany)

Assonquer is a spirit who is found in the historical record of New Orleans Voodoo.

The first mention of him appears in a work of fiction, where Assonquer is described as “the imp of good fortune” .

SOURCE: Cable, George W. The Grandissimes: A Story of Creole Life . United States, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1887. p.94 https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Grandissimes_A_Story_of_Creole_Life/xuYhgJXZIkUC?hl=en&gbpv=0

The other “imps” described in the The Grandissimes are “Papa Lébat”, “Monsieur Danny”, “Miché Agoussou”, and “Monsieur D'Embarras”. All of these appear to have counterparts in the Rada Rite (Rite Arada) , as described by Milo Marcelin.

The description of Assonquer as “imp of good fortune” is vague, but suggests that he has a positive connotation.

Pictured: Ossangne, by Andre Pierre

Previously, I hypothesized that Assonquer was related to Azaka (Médé); however, Jeffrey E. Anderson argues much more persuasively that 'Assonquer' is derived from the lwa Ossangne (Osany), who is part of the Nago Rite*. According to Anderson, he is derived from the orisa Osanyin.

Milo Marcelin lists Ossangne under "AUTRES OGOU", as he is related to the Ogou famille. Ossangne is described as a healer (loa-guérisseur), where a song sung for him describes the healing power of his asson and bagui.

Ossange-ô! laissé couler Mait' Ossange.

O laissé couler!

Yo prend asson Ossange sèvi guérison

O laissé couler!

Yo prend bagui Ossange sèvi guérison

O laissé couler Mait' Ossange!

Ossange-ô! laissé couler Mait' Ossange!

Ossange oh!, laisse faire, Maitre Ossange — O laisse faire! — On se sert de l’asson (hochet cérémoniel) de Ossange pour guérir — O laisse faire! — On se sert du bagui (de l’autel) de Ossange pour guérir — O laisse faire, Maitre Ossange — Ossange oh!, laisse faire, Maitre Ossange!

SOURCE: Marcelin, Milo. Mythologie vodou: rite arada, vol. II . Haiti, Éditions Canapé-Vert, 1950, p. 75-77.

Derivatives of Assonquer such as “On Sa Tier” and “Onzoncaire” appear later in the historical record, being recorded in the 20th century. “On Sa Tier” is mentioned in one of the Federal Writer’s Project interviews, while “Onzoncaire” is identified with Depression-era Voodoo priestess Laura “Lala” Hopkins.

SOURCE: Anderson, Jeffrey E.. Voodoo: An African American Religion. United States, LSU Press, 2024. pp. 69-72

Rather than being derivatives of “Azaka”, “On Sa Tier”, “Onzoncaire”, and "Assonquer" might all be corrupted pronunciations of "Ossangne".

Just a theory.

*SEE: Rigaud, Milo. La tradition voudoo et le voudoo haïtien: son temple, ses mystères, sa magie . FeniXX, 1953. https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/AA00002240/00001

AND: Beauvoir, Max. Lapriyè Ginen. Haiti, Edisyon Près Nasyonal d'Ayiti, 2008.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, my younger cat had to go to the vet today to have a bunch of teeth out. Comes through like a champ, and the vet calls me to come get him.

Vet: He’ll be a little disoriented, so just make him a quiet place he can rest without having to go up and down stairs or anything…

Osanyin: [staggers around the house in the most stoned low-speed zoomies ever] [does figure eights around my legs] [does laps around the living room] [jumps up to power walk back and forth across my lap and back down]

Vet: His jaw will be sore, so just give him wet food…

Osanyin: [shoves his whole head into the dry food bowl, ignoring the half a dish of wet food right beside it]

Vet: It might be a day before he wants to do anything…

Osanyin: [shoves through the cat door to go hang his head over the edge of the porch and window-hunt birds and small dogs]

In other words, we’re two for two here on cats who seem to approve greatly of having fewer teeth.

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

HAAA! AWON ALFA TI GBE OSANYIN KA POTABLE MO ILE O.. AWON ALFA TUN TI BĘ...

0 notes

Photo

Igba Osanyin For inquires, please send an email to [email protected] #igba #osayin #osanyin #osain #ozain #orisa #orisha #oricha #lukumi #lucumi #santeria #yoruba #diaspora #orisacouture https://www.instagram.com/p/CifLkIdA2qR/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#igba#osayin#osanyin#osain#ozain#orisa#orisha#oricha#lukumi#lucumi#santeria#yoruba#diaspora#orisacouture

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Morning 💜

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancestor's Message

I decided to go outside and just be outside. I got my pillow and sat...

Eventually, I picked a card for the day from my 4 Orisha Deck and Osanyin told me to look inside myself... Glad I picked a card, cuz I love positive reinforcement ✨✨✨

--------

✨🔥✨🔥

#witchblr#paganism#pagan#witchcraft#witch#paganblr#tarot#tarot cards#orishas#hoodoo#witch community#eclectic witch

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Confrontation

November Volita piece!! Which is... not as late as it could be :' ) Set in Ether, this is their first meeting several years after Vo'jin disappears, and Amita wanders into the wilderness to find and tame an Arakanok... no easy feat.

#Air's art#Vol'jin#Amita Dakini#Osanyin#Champions#WoW#World of Warcraft#Vol'jin's name in this AU is actually Hades BUT WE'LL NOT GO INTO THAT RN

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The second Ardeat household, Osanyin and Hestia, is next up, and not just because I did the magazine previews there. Also because Hestia is really itching to get some extramarital woohoo. And because Hestia is the only sim in the household who doesn't flood the bathroom when she showers, I want to give her nice things, like Toutatis.

I'd been thinking that the family's servant, Toutatis, was a romance sim too, but he's actually pleasure, which means he wants dates more than he wants woohoo - and dates are risky because Osanyin is working is Oceanography and comes home from work at 2 pm.

So Toutatis tried dating somebody else.

Berengaria is the neighborhood's delivery lady, and she and Toutatis really hit it off. So much so that he rolled an engagement want. So he's buying his freedom (I'm deducting 10k from their starter-house funds) and moving out to marry her.

Crispinus, Osanyin's son with Demeter, ages up to teen. I think he ended up fortune? Maybe popularity? He also managed to reconnect with Demeter during the party, so that was nice. He's into girls and there are very few girls in his cohort for him to be into, so no developments on that front yet.

Hestia and Olokun turned out to be a bit of a challenge - Hestia seemed to consider Olokun, her sister-in-law, to be family, but Olokun didn't - but two horny romance sims will find a way.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tray (Opon Ifa) (circa 1930s) by Areogun of Osi-Ilorin (Yoruba, 1880-1954)

Used by a male or female diviner, this tray features the image of Eshu, the Yoruba divine mediator between the spirit and human realms. His face is framed by mothers kneeling to make offerings in bowls. A priest holding a staff below one of them refers to Osanyin, the Yoruba god of herbal medicine. The carved band of cowrie shells recalls the real shells that are cast onto the tray during a divination session.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Osanyin, Orisha of the Forest

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

ADDENDUM^3

Recently, I started reading Jeffery Anderson’s Voodoo: An African American Religion. Published in 2024, this probably contains the most accurate information about the historical, New Orleans Voudou pantheon (as in, pre-revitalization)

Really interesting book! It might take me a while to finish it…

Some things of note:

Anderson proposes several different origins for the deity Assonquer, arguing that the most likely origin is the orisha Osanyin. One of the alternative theories suggests he is derived from Ossange, described as a lwa with healing powers of the Ogou family.

No mention of Maitre Carrefour. He was either worshiped in secret, or the refraction Fon Legba into the lwa Papa Legba and Kalfou (Maitre Carrefour) was never transmitted to New Orleans. Notably, Anderson describes how the historical, American Papa Legba (“Papa La Bas”) was demonized, where an interview from 1940 equates him with the “devil”. In fact, this seems to be why his name is recorded as “Papa La Bas”; “La Bas” meaning “Down There”, as in “The Devil”.

Previously, I named the Damballah-inspired character “Sir Duke” / “Grand Serpent”. This needs to be changed to “Grandfather Serpent”, or “Grandfather Python”. Damballah is probably associated with Grandfather Rattlesnake, not Grand Zombi. I’m probably going to rename him “Grandfather Python”, to emphasize that he is not a venomous snake. (I gave him fangs for the sake of anime battles and making him look cool, but there is no venom in his fangs… they are just very sharp…) Actually, I’m going with “Grandfather Serpent”, since he’s not specifically a python. Just a giant, magical, non venomous snake!

One of the most important Haitian lwa is Ogou Feray. He appears in the historical record of the American South under the name “Joe Feraille”. He must have come from Haiti through the port of New Orleans, but it is unknown if he was worshiped in New Orleans specifically.

Rather than the Ezilis, there is some evidence that Lasirèn or Mami Wata was worshiped.

With regards to the second note, here is the full quote from Anderson:

“According to FWP information [sic], Alexander Augustin, celebrants would make circles in the water near Spanish Fort and throw food into the lake. The purpose, as he understood it, was to thank Papa Le Bas [sic], whose name Augustin or the FWP worker translated to mean “the Father below” and whom the informant interpreted as Satan.”

Source: Anderson, Jeffrey E. Voodoo: An African American Religion. LSU Press, 2024, p.

The interview he is referring to is found in the Federal Writers Project: Alexander Augustin, “Marie Laveau,” interview by Henriette Michinard, 15 August 1940, transcript, Northwestern State University of Louisiana, Watson Memorial Library, Cammie G. Henry Research Center, Federal Writers’ Project, folder 25.

I think I found the quote from the interview Anderson described:

Alexander Augustin remembered some of the tales of old people which dated to the era of the Widow Paris.

“They would thank St. John for not meddlin’ wit’ the powers the devil gave ‘em,” he said. “They had one funny way of doin’ this when they all stood up to their knees in the water and threw food in the middle of ‘em. You see, they always stood in a big circle. Then they would hold hands and sing. The food was for Papa La Bas, who was the devil. Oldtime Voodoos always talked about Papa La Bas. I heard lots about the Maison Blanche. It was painted white and was built right near the water wit’ bushes all around it so nobody couldn’t see it from the road. It was a kind of hoodoo headquarters.”

Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983. pp. 65-66

I should note, Robert Tallant himself is infamous for his inaccurate, racist descriptions of New Orleans Voodoo.

If you were unaware, the phrase “La Bas” (Là-Bas) used to mean “Down There”, and was historically associated with the Devil. Hence, the title of French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans’ novel Là-Bas (1891), which deals with the subject of Satanism. Over time, the meaning of “La Bas” (Creole: “la ba”) shifted to simply mean “Over There”.

There are two other noteworthy interviews in Tallant’s Voodoo in New Orleans.

The first is the 75-year old “Mary Ellis”, born in 1863 (Alexander Augustin’s age is not specified). Papa Legba is associated with St. Peter. However, his name is recorded as “Laba”, the same pronunciation as “La Bas” (“Down There”, as in “Devil”):

Mary said that most of the things she knew about Marte Laveau had been told her by an aunt who had been a Voodoo.

“My aunt told me one time she had trouble wit’ her landlord. He told her to git out of her house or he’d have her put in jail,” Mary said. “He even sent a policeman after her. The next day she went to Marie Laveau and she told my aunt to burn twelve blue candles in a barrel half full of sand. She done that and my aunt never did have to move and she never went to jail in her whole life. Marie Laveau used to tell people not to burn candles in church ’cause that gived their luck to somebody else, so they burned ’em in her house instead. She’d tell my aunt, ‘If you gonna fool ’em, fool ’em good, Alice.’ She was real good to my aunt. She even taught her a Voodoo song. It went like this:

St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door,

I’m callin’ you, come to me!

St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door …

“That’s all I can remember. Marie Laveau used to call St. Peter somethin’ like ‘Laba.’ She called St. Michael ‘Daniel Blanc,’ and St. Anthony ‘Yon Sue.’ There was another one she called ‘On Za Tier’; I think that was St. Paul. I never did know where them names come from. They sounded Chinee to me. You know the Chinee emperor sent her a shawl? She wore it all the time, my aunt told me.”

Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983. P. 103

This “Mary Ellis” is Mary Washington, and this interview can be found in the aforementioned folder 25 of the Federal Writers Project.

The second is the 87-year old “Josephine Green”, born in 1853. Here, Papa Legba (called “Papa Limba”) is again erroneously identified with “the devil”.

Josephine Green, an octogenarian, recalled her mother’s stories about Marie Laveau.

“My ma seen her,” Josephine boasted. “It was back before the war what they had here wit’ the Northerners. My ma heard a noise on Frenchman Street where she lived at and she start to go outside. Her pa say, ‘Where you goin’? Stay in the house!’ She say, ‘Marie Laveau is comin’ and I gotta see her.’ She went outside and here come Marie Laveau wit’ a big crowd of people followin’ her. My ma say that woman used to strut like she owned the city, and she was tall and good-lookin’ and wore her hair hangin’ down her back. She looked just like a Indian or one of them gypsy ladies. She wore big full skirts and lots of jewelry hangin’ all over her. All the people wit’ her was hollerin’ and screamin’, ‘We is goin’ to see Papa Limba! We is goin’ to see Papa Limba!’ My grandpa go runnin’ after my ma then, yellin’ at her, ‘You come on in here, Eunice! Don’t you know Papa Limba is the devil?’ But after that my ma find out Papa Limba meant St. Peter, and her pa was jest foolin’ her.”

Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. 1946. Reprint, Gretna, La.: United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983. Pp. 57-58

This “Josephine Green” is Josephine McDuffy, and this interview can be found in the same folder 25 of the Federal Writers Project.

This is another reason I think Papa Legba probably is “The Devil at the Crossroads”, especially because of the association with music and dogs. Another strong candidate is the Yoruba deity Eshu. If Papa Legba was merged with Eshu, this would explain the “old, limping Black man” who appears in folklore of the African American South.

Sadly, Eshu and the family of related deities (including Legba) were demonized all over the world…

RE: Was Baron Samedi worshiped in New Orleans prior to the late 20th century?

This one is also about the actual lwa.

Baron Samedi can aptly be described as not just the most iconic lwa, but one of the most iconic things from New Orleans Voodoo. Ironically, I have only found inconclusive evidence that he was worshiped in New Orleans during the 19th or early 20th centuries.

In American popular media, Baron Samedi is frequently conflated with other Haitian deities, called the Gede. The real-life Baron Samedi has his origins in Haitian Vodou, as does Maman Brigitte (Gran Brijit). The Haitian lwa are derived from African deities, among the most important being the Dahomean trickster god Legba (himself, derived from the Yoruba deity Eshu). Over the course of Haitian history, Dahomean Legba was refracted into Papa Legba, Met Kalfou, and the Gede - by extension, the Bawons, including Baron Samedi. This explains why the Gede are trickster deities of sexuality and liminality, who embrace all that is taboo - just like Dahomean Legba!

19th Century New Orleans Voodoo was greatly influenced by Haitian Vodou, due to the massive influx of Haitian refugees that arrived in the Crescent City after the Haitian Revolution. Following the post-Revolution migration wave, several Haitian lwa became features of New Orleans Voodoo, including:

Papa Legba → “Papa Limba” or “La Bas”, syncretized with St. Peter

Damballah → “Daniel Blanc”, syncretized with St. Michael

Agassu → “Yon Sue”, syncretized with St. Anthony

Ogou Feray could have also been worshiped as “Joe Ferrai” (“Joe Feray”), and Ayizan Velekete as “Vériquité”. While the Erzulies were not directly worshiped per se, veneration of Mother Mary was a key feature of 19th century New Orleans Voodoo. (The Erzulies are syncretized with Mother Mary.)

(I should also note that, in New Orleans, the lwa were called “spirits”, while Bon Dieu/Bondye was simply called “God”)

During the 19th century, the two most important lwa were probably Papa Legba - the Doorkeeper - and Damballah - the most ancient of the lwa. This would explain why their names appear most frequently in 19th- and 20th-century sources, especially in large scale rituals. Damballah might have been refracted into multiple deities, including “Daniel Blanc” and “Zombi the Snake God” – a deity famously associated with Marie Laveau. Others argue that “Grand Zombi” is actually derived from the Kongo supreme deity Nzambi Mpungu, or an invention fabricated by journalists.

A third key deity – “Onzancaire” / “Monsieur Assonquer” – might have been associated with Ogou Feray – one of the most important Haitian lwa. However, the origins of “Onzancaire” are elusive. Because so many different theories have been proposed, I do not know where his true origins lie.

Other deities of non-Haitian origin were also features of New Orleans Voodoo. St. Marron (Jean St. Malo) was the New Orleanian folk saint of runaway slaves. Mother Leafy Anderson – founder of the Spiritual Church Movement in New Orleans – introduced worship of the Native American Saint Black Hawk (see: Kodi A. Roberts (2015) Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans, 1881–1940). My understanding is that “Dr. John” (Jean Montaigne) was also deified, in a similar manner to St. Black Hawk. Orisha, such as Shango and Oya, may too have been worshiped. Other deities are listed here and here.

Baron Samedi is conspicuously absent. I think this has to do with the history of Haitian Vodou. Prior to the Haitian Revolution, Haitian Vodou was less of an organized religion, described as a "widely-scattered series of local cults" (see: The Social History of Haitian Vodou, p. 134). It was between the years 1804 and 1860 that Haitian Vodou began to stabilize into a clear predecessor of its present form. (see: The Social History of Haitian Vodou, p. 139) This period of stabilization took place after the migration wave of the early 19th century, which could explain why key features of Haitian Vodou are missing from 19th century New Orleans. For example, I have yet to find evidence that division of the Petwo and Rada lwa made it over to American soil. The refraction of Dahomean Legba might have never been transmitted by Haitian refugees, which would explain the absence of Met Kalfou and the Gede/Bawons from worship.

This too explains why the Papa Legba of American history was both Doorkeeper AND Guardian of the Crossroads. It has been theorized that the legendary “Devil at the Crossroads” was actually Met Kalfou. However, this “Devil” does not match the appearance of Kalfou, described as "no ancient, feeble man...huge and straight and vigorous, a man in the prime of his life." Instead, the one at “the Crossroads” appears as a limping old man who loves music and dogs (“Hellhound on my Trail”). It’s Papa Legba!

Rather than Kalfou, I think American Papa Legba actually inherits his more menacing attributes from Eshu. This would explain why he walks with a limp (like Eshu), is notoriously vengeful (like Eshu), and is sometimes described as androgynous (like Eshu!).

In any case, the Papa Legba of American history can be clearly traced back to Haiti. His appearance as a limping old man is inherited from Haitian Papa Legba; his love of dogs and music from Dahomean Legba. 19th century sources clearly identify him with Saint Peter (“St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door;”) The same cannot be said for Baron Samedi. He was probably not syncretized with St. Expedite, because St. Expedite “did not achieve popularity until the late 1800s or early 1900s in New Orleans” – long after the Haitian migration wave.

I have found one compelling source that places worship of Baron Samedi in 19th century New Orleans. Creole author Denise Alvarado is something of an expert on this topic, her being born and raised in New Orleans. In Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans (2022), Denise Alvarado identifies a “Spirit of Death” with Baron Samedi / Papa Gede. The most convincing piece of evidence comes from the second interview, in which the interviewee describes a ceremony where attendees donned purple robes. The color purple has been historically associated with Papa Gede (by extension, Baron Samedi).

That being said, I do think the evidence Alvarado provides is tenuous. Without additional context, it’s difficult to say whether the purple robes are truly linked to the Haitian lwa. The other newspaper article sounds rather sensationalized. The 19th century saw horrendous news coverage of New Orleans Voodoo, where reporters would exaggerate or straight-up fabricate details to demonize Vodouisants. The reporter’s description of the spirits of death does not align with the Haitian Gede or Bawons. It is important to remember that New Orleans Voodoo is not entirely Haitian in origin. Several other traditional African spiritualities are woven into New Orleans Voodoo. Prior to the Haitian migration wave of the early 19th century, one of the main influences was Kongo spirituality, in which ancestor veneration is central. Additionally, the newspaper cited is from the year 1890 – years after Marie Laveau’s death. The reliability of this article is therefore questionable. I think this could be a Damballah / “Grand Zombi” situation, where this “Spirit of Death” bears superficial resemblance to the lwa but isn’t actually him. It is also possible that he is simply a fabrication by journalists.

The defamation of Vodou continued into the early 20th century, as Haiti was occupied by the U.S. between the years 1915 and 1934. I don’t see how worship of the Gede/Bawons could have been transmitted to New Orleans between the end of the Haitian migration wave and year 1934. There’s a good chance that Baron Samedi / Papa Gede only properly became features of New Orleans Vodou during the revitalization movement of the late 20th century.

As such, I propose two hypotheses:

Baron Samedi was not properly worshiped in New Orleans until the late 20th century. He quickly rose in popularity, as he was easily grafted onto the pre-existing worship of the spirits of the dead (ancestors).

Alvarado has correctly identified Baron Samedi / Papa Gede with the “Spirit of Death”; however, this “Spirit of Death” was a radical departure from his Haitian predecessor, taking on a markedly different form from the lwa.

But that’s all just a Theory… A GAME THEORY!!!

…Anyways, annotated bib:

Marshall, Emily Zobel. American Trickster: Trauma, Tradition and Brer Rabbit. Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

Chapter 1 ("African Trickster in the Americas") describes Dahomean Legba’s origins in the Yoruba deity Eshu.

Cosentino, Donald. "Who is that fellow in the many-colored cap? Transformations of Eshu in old and new world mythologies." Journal of American Folklore (1987): 261-275. https://www.jstor.org/stable/540323.

From the abstract: “Myths of Eshu Elegba, the trickster deity of the Yoruba of Nigeria, have been borrowed by the Fon of Dahomey and later transported to Haiti, where they were personified by the Vodoun in the loa Papa Legba. In turn, this loa was refracted into the corollary figures of Carrefour and Ghede.” Accessed here: https://www.centroafrobogota.com/attachments/article/24/17106647-Ellegua-Eshu-New-World-Old-World.pdf

Haitian immigration : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. The African American Migration Experience. https://www.inmotionaame.org/print.cfm@migration=5.htm

Describes post-Haitian Revolution migration wave like so: “the number of immigrants [from Haiti to New Orleans] skyrocketed between May 1809 and June 1810… The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free persons of African descent, and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its population.”

Fandrich, Ina J. “Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 37, no. 5, 2007, pp. 775–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034365. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Mentions worship of Ogou Feray as “Joe Ferrai”.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 247: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT247#v=onepage&q&f=false

Mentions worship of Ayizan Velekete as (the male) “Vériquité”.

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Hoodoo, voodoo, and conjure: A handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2008, p. 15: https://books.google.com/books?id=TH7DEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: "Blanc Dani, Papa Lébat, and Assonquer make the most frequent appearances in both nineteenth- and twentieth-century sources. The first two, in particular, figure prominently in large-scale rituals."

Humpálová, Denisa. "Voodoo in Louisiana." (2012). https://dspace5.zcu.cz/bitstream/11025/5338/1/BP%20Denisa%20Humpalova%202012.pdf

One of several sources that identifies “Grand Zombi” with Nzambi Mpungu.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 247: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT247#v=onepage&q&f=false

Posits that “Grand Zombi” could be derived from Nzambi Mpungu, or "may be the invention of journalists inspired by "zombie tales" of Haiti's infamous living dead, combined with Moreau de Saint-Méry’s endlessly repeated description of a snake-worshiping ceremony in colonial Saint Domingue."

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Voodoo: An African American Religion. LSU Press, 2024, p. 46: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Voodoo/O-v3EAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22assonquer%22+%22azewe%22+vodou&pg=PA46&printsec=frontcover

Describes several possible origins for the elusive “Onzancaire”, including a theory that he was a deity related to Ogou Feray.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 236: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT236#v=onepage&q&f=false

One of several sources to describe St. Marron (Jean St. Malo).

Roberts, Kodi A. Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans, 1881-1940. LSU Press, 2015, p. 82: https://books.google.com/books?id=EWOkCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT82&lpg=PT82

Describes how Mother Leafy Anderson (founder of the Spiritual Church Movement) “found” St. Black Hawk, introducing him to New Orleans Voodoo.

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, p. 39: https://books.google.com/books?id=ktlWEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39#v=onepage&q&f=false

Posits that high priestess Betsy Toledano worshiped the Orisha Shango and Oya during the 19th century.

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Hoodoo, voodoo, and conjure: A handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2008, p. 15: https://books.google.com/books?id=TH7DEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15#v=onepage&q&f=false

List of deities worshiped in 19th century New Orleans Voodoo.

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, p. 126: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Witch_Queens_Voodoo_Spirits_and_Hoodoo_S/ktlWEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA126

Another list of deities worshiped in 19th century New Orleans Voodoo.

Mintz, Sidney & Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (1995) “The social history of Haitian Vodou” in Cosentino, Donald J., ed., Sacred Arts of Vodou, Chapter 4. LA: UCLA Fowler Museum, 123-47. P. 134: https://ghettobiennale.org/files/Trouillot_Mintz_LOW.pdf

Describes Haitian Vodou as a "widely-scattered series of local cults" prior to the Haitian Revolution.

Mintz, Sidney & Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (1995) “The social history of Haitian Vodou” in Cosentino, Donald J., ed., Sacred Arts of Vodou, Chapter 4. LA: UCLA Fowler Museum, 123-47. P. 139: https://ghettobiennale.org/files/Trouillot_Mintz_LOW.pdf

Describes the stabilization of Haitian Vodou into a predecessor of its current form. This occurred between the years following the Haitian Revolution and year 1860.

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen : The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 1983 (originally published in 1953), p. 101: https://archive.org/details/divinehorsemenli00dere/page/100/mode/2up

Description of Kalfou (Carrefour) as "no ancient, feeble man...huge and straight and vigorous, a man in the prime of his life."

Marvin, Thomas F. “Children of Legba: Musicians at the Crossroads in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.” American Literature, vol. 68, no. 3, 1996, pp. 587–608. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2928245. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Description of “The Devil at the Crossroads” as a musical genius and “limping old black man”: “Most versions of this story instruct the aspiring musician to bring his instrument to a lonely crossroads at midnight and await the arrival of a limping old black man who will tune the instrument, play it briefly, and then return it endowed with supernatural power."

Robert Johnson’s song “Hellhound on My Trail” identifies “The Devil at the Crossroads” with Papa Legba, who is associated with dogs.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 244: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT244&lpg=PT244#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: "Mary Washington, born in 1863, said she was trained in the arts of Voudou by Marie Laveau. She remembered a song that was sung at the weekly ceremonies: "St. Peter, St. Peter open the door; I am callin' you, come to me; St. Peter, St. Peter open the door." Mrs. Washington explained that "St. Peter was called La Bas, St. Michael was Daniel Blanc, and Yon Sue was St. Anthony." She also mentioned a spirit called Onzancaire."

Alvarado, Denise. The Magic of Marie Laveau: Embracing the Spiritual Legacy of the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2020, p. 57: https://books.google.com/books?id=SZOMDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA57&lpg=PA57#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: “Baron Samedi remains a popular and powerful force in New Orleans Voudou today, along with his wife Manman Brigit. He is syncretized with St. Expedite, among the most popular of saints in New Orleans. We do not hear of St. Expedite in association with Marie Laveau, however, because he did not achieve popularity until the late 1800s or early 1900s in New Orleans (Alvarado 2014).”

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, pp. 127-128: https://books.google.com/books?id=GsofEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA127&lpg=PA127#v=onepage&q&f=false

This is the strongest evidence I could find that Baron Samedi / Papa Gede was worshiped in 19th - early 20th Century New Orleans.

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen : The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 1983 (originally published in 1953), p. 107: https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.505921/page/107/mode/2up?q=purple

Historical evidence that, since at least the 1930s, Papa Gede’s colors are “black or purple”. To this day, purple is associated with Baron Samedi and the Gede as a whole.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 250: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT250&lpg=PT250

Relevant quote: “The religion that evolved in nineteenth-century New Orleans and was embraced by Marie Laveau and her Voudou society combined traditions introduced by the first Senegambian, Fon, Yoruba, and Kongo slaves with Haitian Vodou, European magic, and folk Catholicism. It also absorbed the beliefs of blacks imported from Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas during the slave trade of the 1830s–1850s. These “American Negroes” were English-speaking, at least nominally Protestant, and practiced a heavily Kongo-influenced kind of hoodoo, conjure, or rootwork. New Orleans Voudou is therefore not identical to Haitian Vodou, but represents a unique North American blend of African and European religious and magical Traditions.”

Fandrich, Ina J. “Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 37, no. 5, 2007, pp. 775–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034365. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Describes major Senegambian and Kongo influences on New Orleans Voodoo, prior to the Haitian Revolution. Relevant quote: “New Orleans's African population was Kongo dominated with a strong affinity with the spirits of the dead…Dahomeyan influence occurred only indirectly through the Haitian refugees who "flooded" the city after 1808. In 1809 alone, more than 10,000 Haitians arrived, and doubled the city's population. They brought their Vodou religion with them, which ultimately merged with the already existing New Orleans or Louisiana Voodoo traditions. During the French colonial regime, 80% of the enslaved Africans came from one single ethnic group: the Bamana (also called Bambara) people from the Senegal River basin (today's Senegal, Gambia, and Mali), most of them stemming from one single ethnic group, the Bambara people. The majority of the remaining 20% were Kongolese and some Dahomeyans (Hall, 1992). Despite their rather different geographical origins, these two cultures blend easily into one another. Eighteenth-century Louisiana Voodoo maintained a marked Senegambian flavor, with some Kongolese elements blended in, until the end of the 18th century.”

Dubois, Laurent. “Vodou and History.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 43, no. 1, 2001, pp. 92–100. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2696623. Accessed 23 June 2024.

An overview of the history of Haitian Vodou, as it pertains to U.S. history. Demonization of Vodou continued past the U.S. occupation of Haiti, until the late 20th century.

#commentary#anderson found no evidence of worship of baron samedi or papa gede#however i think it possible baron samedi made it to America and that he is the identity of the “devil” in the high silk hat...#i could be wrong...

12 notes

·

View notes