#Oregon Cascade range

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Hidden Ocean Beneath Oregon’s Cascades? Scientists Uncover a Massive Underground Aquifer

Deep beneath the rugged peaks of Oregon’s Cascade Range, scientists have discovered what could be one of the largest underground aquifers in the world—a vast, hidden reservoir of water spanning many miles. Over 81 cubic kilometers of fresh water is the current estimate. This subterranean ocean, tucked within the region’s porous volcanic rock, could hold billions of gallons, reshaping our…

0 notes

Text

Snowshoeing through the Cascade Range.

Oregon

1970

#vintage camping#campfire light#oregon#three sisters#cascade range#hiking#snowshoeing#history#outdoors#1970s

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

West Diamond Lake Highway, OR (No. 2)

Mount Bailey is a relatively young tephra cone and shield volcano in the Cascade Range, located on the opposite side of Diamond Lake from Mount Thielsen in southern Oregon, United States. Bailey consists of a 2,000-foot (610 m)-high main cone on top of an old basaltic andesite shield volcano. With a volume of 8 to 9 km3 (1.9 to 2.2 cu mi), Mount Bailey is slightly smaller than neighboring Diamond Peak. Mount Bailey is a popular destination for recreational activities. Well known in the Pacific Northwest region as a haven for skiing in the winter months, the mountain's transportation, instead of a conventional chairlift, is provided by snowcats—treaded, tractor-like vehicles that can ascend Bailey's steep, snow-covered slopes and carry skiers to the higher reaches of the mountain. In the summer months, a 5-mile (8 km) hiking trail gives foot access to Bailey's summit. Mount Bailey is one of Oregon's Matterhorns.

Native Americans are credited with the first ascents of Bailey. Spiritual leaders held feasts and prayer vigils on the summit.

Source: Wikipedia

#Boundary Springs Trailhead#West Diamond Lake Highway#Mount Thielsen#High Cascades#Mount Bailey#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#countryside#USA#California#summer 2023#flora#nature#forest#woods#tree#view#Westcoast#Cascade Range#Oregon#Pacific Northwest

23 notes

·

View notes

Video

Tumalo Falls by James Marvin Phelps Via Flickr: Tumalo Falls Deschutes National Forest Bend, Oregon July 2023

#oregon#bend oregon#waterfall#tumalo falls#deschutes national forest#creek#river#canyon#landscape#cascade range#tumalo creek#forest#trees#flow#cascade#james marvin phelps photography#flickr

16 notes

·

View notes

Video

Mountains in Southern Oregon on a Flight out of Medford by Mark Stevens Via Flickr: An airplane window view looking to the north while on out of Medford, Oregon. What I wanted to capture with this image was the view of mountains that I had been amongst for the past few days. This just happen to be in Oregon, but I had experienced quite a few wonderful views in California earlier in the week. I initially let the camera set a focus for this setting, but I then made manual adjustments with the lens ring in order to bring more of a focus that I’ve found is sometimes required for a view looking through an airplane window.

#Airplane Window View#Azimuth 348#Blue Skies#Blue Skies with Clouds#California and Oregon Road Trip#Cascade Range#Crater Lake Area#Day 10#DxO PhotoLab 5 Edited#Flight MFR to PHX#Flying over Oregon#Jet Airplane#Long Mountain#Looking North#Looking Outside Plane Window#Looking out Airplane Window#Looking out the Airplane Window#Miscellaneous#Mountain Peak#Mountain Peaks#Mountains#Mountains in Distance#Mountains off in Distance#Mountainside#Nikon D850#Oregon Cascades#Pacific Ranges#Partly Cloudy#Plane Window#Project365

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lower Twin Lake, Mt. Hood National Forest

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#cascade range#cascade volcanic arc#flower bloom#flowers#spring flowers#spring#mount hood#oregon#wildflowers#wyeast

0 notes

Text

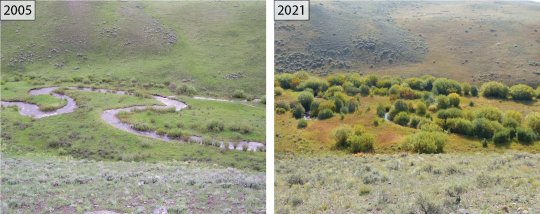

"A new study reveals the profound ecological effects of wolves and other large carnivores in Yellowstone National Park, showcasing the cascading effects predators can have on ecosystems. In Yellowstone, this involves wolves and other large carnivores, elk, and willows.

The research, which utilized previously published data from 25 riparian (streamside) sites and collected over a 20 year period, from 2001 to 2020, revealed a remarkable 1,500% increase in willow crown volume along riparian zones [note: riparian means in/around rivers] in northern Yellowstone National Park, driven by the effects on elk due to a restored large carnivore guild following the reintroduction of wolves in 1995–96, and other factors...

Pictured: Upstream view of Blacktail Deer Creek in 2005 and 2021, northern range of Yellowstone National Park.

Trophic cascades, the effects of predators on herbivores and plants, have long been a topic of ecological interest. The study quantifies the strength of this phenomenon for the first time using willow crown volume as a proxy for aboveground biomass, demonstrating a significant three-dimensional recovery of riparian vegetation represented by the growth in both crown area and height of established willows.

The strength of the Yellowstone trophic cascade observed in this study surpasses 82% of strengths presented in a synthesis of global trophic cascade studies, underscoring the strength of Yellowstone's willow recovery process. The authors note that there is considerable variability in the degree of recovery and not all sites are recovering.

Even though riparian areas in the western United States comprise a small portion of the landscape, the study has particular relevance since these areas provide important food resources and habitat for more wildlife species than any other habitat type. These areas also connect upland and aquatic ecosystems and are widely known for their high diversity in species composition, structure, and productivity.

"Our findings emphasize the power of predators as ecosystem architects," said William Ripple. "The restoration of wolves and other large predators has transformed parts of Yellowstone, benefiting not only willows but other woody species such as aspen, alder, and berry-producing shrubs. It's a compelling reminder of how predators, prey, and plants are interconnected in nature."

Pictured: An across channel view in 2005 and 2021 of a downstream reach on Blacktail Deer Creek, northern range of Yellowstone National Park.

Wolves were eradicated and cougars driven to low numbers from Yellowstone National Park by the 1920s. Browsing by elk soon increased, severely damaging the park's woody vegetation, especially in riparian areas. Similar effects were seen in places like Olympic National Park in Washington, and Banff and Jasper National Parks in Canada after wolves were lost.

While it's well understood that removing predators can harm ecosystems, less is known about how strongly woody plants and ecosystems recover when predators are restored. Yellowstone offers a rare opportunity to study this effect since few studies worldwide have quantified how much plant life rebounds after large carnivores are restored.

"Our analysis of a long-term data set simply confirmed that ecosystem recovery takes time. In the early years of this trophic cascade, plants were only beginning to grow taller after decades of suppression by elk. But the strength of this recovery, as shown by the dramatic increases in willow crown volume, became increasingly apparent in subsequent years," said Dr. Robert Beschta, an emeritus professor at Oregon State University.

"These improving conditions have created vital habitats for birds and other species, while also enhancing other stream-side conditions."

The research points to the utility of using crown volume of stream-side shrubs as a key metric for evaluating trophic cascade strength, potentially advancing methods for riparian studies in other locations. It also contextualizes the value of predator restoration in fostering biodiversity and ecosystem resilience."

-via Phys.org, February 6, 2025

#wolves#willow tree#trees#yellowstone#yellowstone national park#united states#north america#ecosystem#ecology#ecosystem restoration#wildlife#rivers#riparian#good news#hope

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the 1990s had a cascading effect that benefited the entire ecosystem, a new study finds. The finding shows how the return or loss of apex predators can affect every part of the food web. By the 1920s, gray wolves (Canis lupus) were no longer present in Yellowstone National Park and cougar (Puma concolor) populations were very low, as a result of government initiatives to control large predator populations. Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus canadensis) thrived without these predators, which in turn decimated some plant populations. The loss of some trees and shrubs then threatened beaver populations. This sequence of events is known as a trophic cascade — when the actions of top predators indirectly affect other species further down the food web, ultimately affecting the entire ecosystem.

[...]

The new study, published Jan. 14 in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation, used 20 years' worth of data, collected from 2001 to 2020, regarding willow shrubs (Salix) along streams in Yellowstone. The researchers looked at willow crown volume — the total space occupied by a shrubs' branches, stems and leaves. Measuring crown volume enabled the researchers to calculate the shrubs' overall biomass: the amount of organic material available at the plant level of the food web, and the energy that will be passed on through the food web when animals eat these plants. "Yellowstone's northern range is the perfect natural laboratory for studying these changes. It is one of the few places in the world where we can observe what happens when an apex predator guild, including wolves and cougars, is restored after a long absence," study first author William Ripple, an ecologist at Oregon State University, told Live Science in an email. "The lessons we learn here can apply to other ecosystems globally." The analysis found a 1,500% increase in willow crown volume along streams over the study period, demonstrating a major recovery of these shrubs. The study links this significant willow shrub recovery to a reduction in elk browsing, probably influenced by the return of predators to the region, which enabled willows to grow back in some areas. "One of the most striking results was just how strong the trophic cascade has been," Ripple said. "A 1,500% increase in willow crown volume is a big number. It is one of the strongest trophic cascade effects reported in the scientific literature."

25 February 2025

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

This ties into one of the big conundrums of restoration ecology. When trying to decide what plants to add to a restoration site, should we add those that are there now, even if some of those species are increasingly stressed by the effects of climate change? Or do we start importing native species in adjacent ecoregions that are more tolerant of heat?

Animals can migrate relatively quickly, but plants take longer to expand their range, and the animals that they have mutual relationships with may be moving to cooler areas faster than the plants can follow. Whether the animals will be able to survive in their new range without their plant partners is another question, and that is an argument in favor of trying to help the plants keep up with them. We're not just having to think about what effects climate change will have next summer, but also predict what it's going to look like here in fifty years, a hundred, or beyond. It's an especially important question in regards to slow-growing trees which may not reproduce until they are several years old, and which can take decades to really be a significant support of their local ecosystem.

For example, here in the Pacific Northwest west of the Cascades, western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is experiencing increased die-off due to longer, hotter summer droughts. Do we continue to plant western red cedar, in the hopes that some of them may display greater tolerance to drought and heat? Or do we instead plant Port Orford cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana), which is found in red cedar's southern range, and which may be more drought-tolerant, even though it's not found this far north yet?

Planting something from an adjacent ecoregion isn't the same as grabbing a plant from halfway around the world and establishing it as an invasive species. But there is the question as to whether the established native would have been able to survive if we hadn't introduced a competing "neighbor" species. Would the Port Orford cedars and western red cedars be able to coexist as they do in northern California and southern Oregon, or would the introduced Port Orfords be enough to push the already stressed red cedars over the edge to extirpation?

There's no simple answer. But I am glad to see the government at least allowing some leeway for those ecologists who are desperately trying any tactic they can to save rare species from extinction.

#restoration ecology#ecology#habitat restoration#climate change#global warming#anthropogenic climate change#nature#wildlife#plants#botany#trees#endangered species#extinction#environment#conservation#environmentalism#science#scicomm#science communication

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Western Spotted Skunks

Marie Tosa, a postdoctoral researcher at Oregon State University, led a 2½-year study in Oregon's Cascade Range, revealing new insights into the Western Spotted Skunk—a small, elusive species about which little is known. These skunks prefer remote, undisturbed mountainous habitats and are rarely seen, despite their range spanning from New Mexico to British Columbia. Threatened by human-induced land use changes, Tosa’s findings offer valuable data to guide future monitoring and conservation efforts, helping protect the species as environmental pressures intensify.

via: Oregon State University

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Coyote Tales of the Shasta Nation

The Coyote tales come from the Shasta people who originally inhabited the regions of modern-day northern California and southern Oregon. Coyote is a popular trickster figure among many Native peoples of North America, including the Shasta, and their Coyote tales are among the most popular. Two of the best-known are Why Mount Shasta Erupted and Land of the Ghost Dance.

Coyote in the Snow, Yosemite, California, USA

Yathin S. Krishnappa (CC BY-SA)

The Shasta came into contact with Euro-Americans in 1826, and soon after, their traditional lifestyle and culture suffered enormously. Scholar Adele Nozedar comments on their ancestral lands and culture and the challenges they faced after 1826:

Originally, the Shasta lived in California, and are remembered in the names of the Shasta River and Mount Shasta. The tribe lived in permanent villages rather than being nomadic or semi-nomadic, living in plank houses, using dugout canoes, and having acorns as a staple food. The Shasta divided up their territory into areas in which certain families had the right to hunt, a privilege that was handed down the father's line…A peaceful people, the Shasta suffered when the California Gold Rush started in the 1820's, some of them poisoned, for no reason, by settlers…, in common with others, in an attempt to reclaim a sense of identity, the Shasta embraced the Ghost Dance Movement.

(433)

Like the Pawnee, the rituals of the Ghost Dance (which naturally included songs, chants, and prayers in one's native language) helped the Shasta preserve their culture, their language, and the stories handed down through oral transmission for centuries; the Coyote tales among them. In June 2024, Governor Gavin Newsom of California gave back 2,800 acres of ancestral homeland to the Shasta in an initiative to right past injustices. Today, the Shasta continue to rebuild their language and culture and a significant aspect of that effort is their stories.

Coyote Tales of the Shasta

The Coyote tales, like the Iktomi tales of the Lakota Sioux or the Wihio tales of the Cheyenne, feature a central trickster character – who may appear in many different forms and roles but always teaches a lesson and is involved in some sort of transformative event – and, in this case, that main character is Coyote. Scholar Bobby Lake-Thom comments:

Coyote is one of the most ancient mythic symbols for most Native tribes. He is often portrayed as either the creator or the trickster. He is full of magic, special powers, and teachings. We learn from the lessons that Coyote gives us about the mistakes and/or accomplishments he has made in life.

(84)

As with other tricksters, the Coyote of the Shasta people may appear as a hero, a villain, a fool, a wise man, a Creator God, or a con artist depending on the tale. In Why Mount Shasta Erupted and Land of the Ghost Dance, he plays the role of the novice who fails to grasp a given situation; not necessarily a fool, but one lacking in experience and so prone to mistakes. In this role, Coyote is made accessible to an audience who may identify, and sympathize, with his errors and are given the opportunity to learn from them.

Why Mount Shasta Erupted is an origin tale explaining why Mount Shasta of the Cascade Range of modern-day Siskiyou County, California, looks the way it does. The story may also reference the historical event of the volcanic eruption of Mount Shasta c. 1250 and provide an explanation for that. The Shasta – along with other nations including the Klamath and Modoc – inhabited the region around Mount Shasta for approximately 14,000 years before the arrival of Euro-Americans, and the Shasta tale of the c. 1250 eruption could well date to shortly after that event. As the tale was passed down through oral transmission, however, its date of composition is unknown.

Mount Shasta in the Siskiyou Mountains, California

Greg Schechter (CC BY)

Land of the Ghost Dance shares similarities with death-origin myths of other Native American nations, including How Death Came into the World (Modoc legend) and the Kiowa death-origin myth: two versions - How Death Came into the World and Why the Ant is Almost Cut in Two. In the Shasta story, Coyote decrees death as a necessity but regrets this when his son dies. Land of the Ghost Dance references the vision of the Ghost Dance Movement of 1889 – that the souls of the dead lived on in another, better realm – but stands as a cautionary tale on the dangers of refusing to accept loss and clinging to the past. This theme is common to ghost stories of many different nations, notably The Ghost Wife of the Pawnee.

Continue reading...

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

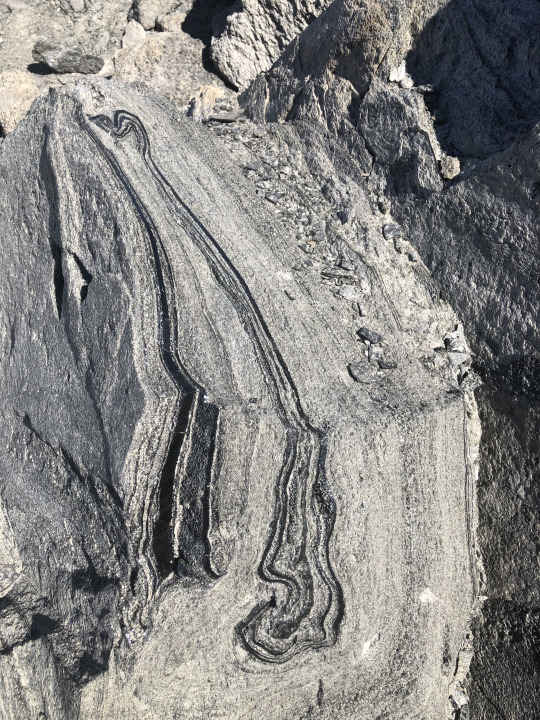

The Big Obsidian Flow is the youngest lava flow in Oregon, at the juvenescent age of ~1,300 years before present. It's a product of the most recent eruption of Newberry Volcano, the largest in the Cascade Range north of the California border (Medicine Lake Volcano is the largest overall). Newberry is a bit enigmatic - it's a huge volcano with a high rate of large eruptions but is not on the main Cascade volcanic arc. There's a number of converging fault zones in this area, which probably create significant crustal weakness allowing magma to percolate through the crust quickly.

Obsidian is common in lava flows of the rhyolitic composition, which is the most evolved kind of magma. Rhyolite magma spends lots of time spent in the crust for crustal rocks to contaminate the magma body and for heavier iron/magnesium-rich minerals to settle out, leaving behind a melt with over 68% silica (quartz). Silica is the same stuff regular glass is made of, so the higher your silica content then the glassier your lava flow is likely to be on the surface. The bands present in big chunks of obsidian are the result of shearing, differential cooling/composition, and flowing during the lava flow. This is very thick, sticky, viscous lava that doesn't like to flow. As it cools, it breaks rather than bends and turns the lava flow into a moonscape of glass shards and boulders.

The large amount of obsidian at this and other flows around Newberry Volcano is interesting because the volcano is mostly made of basalt - a lava with a near-opposite composition from rhyolite. Akin to Mauna Loa or Iceland, most of Newberry's lava flows form a broad shield more than 60 miles N-S and 30 miles E-W (roughly 100x50 km). The central part of the Volcano is about ten miles (16 km) across and contains a caldera formed when the central summit collapsed ~75,000 years ago. The caldera has been filled by subsequent eruptions and by two lakes separated by a big pumice cone. This means that the volcano produces - simultaneously - a wide range of magma compositions, indicating a complicated and long-lived magmatic system. Hazards from Newberry (to the 200,000 people living on its slopes) are not limited to fluid basalt eruptions that slowly blanket the landscape but also major explosive eruptions. The Big Obsidian Flow is a representative of the latter. Ash and debris from that eruption is found as far away as Idaho, and is many meters deep near the eruption's vent.

#oregon geology#geology#lava#magma#obsidian#volcano#volcanology#newberry volcano#central oregon#bendoregon#Cascade Volcanoes#PNW Volcano#rocks#oregon

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

West Diamond Lake Highway, OR (No. 4)

The Cascade Range or Cascades is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as many of those in the North Cascades, and the notable volcanoes known as the High Cascades. The small part of the range in British Columbia is referred to as the Canadian Cascades or, locally, as the Cascade Mountains. The highest peak in the range is Mount Rainier in Washington at 14,411 feet (4,392 m).

The Cascades are part of the Pacific Ocean's Ring of Fire, the ring of volcanoes and associated mountains around the Pacific Ocean. All of the eruptions in the contiguous United States over the last 200 years have been from Cascade volcanoes. The two most recent were Lassen Peak from 1914 to 1921 and a major eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980. Minor eruptions of Mount St. Helens have also occurred since, most recently from 2004 to 2008.The Cascade Range is a part of the American Cordillera, a nearly continuous chain of mountain ranges (cordillera) that form the western "backbone" of North, Central, and South America.

Source: Wikipedia

#Diamond Peak Lookout Point#Odell Lake#Diamond Peak#Boundary Springs Trailhead#West Diamond Lake Highway#Mount Thielsen#High Cascades#Mount Bailey#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#countryside#USA#California#summer 2023#flora#nature#forest#woods#tree#view#Westcoast#Cascade Range#Oregon#Pacific Northwest

17 notes

·

View notes

Video

Tumalo Falls II by James Marvin Phelps Via Flickr: Tumalo Falls II Deschutes National Forest Bend, Oregon July 2023

#oregon#bend oregon#waterfall#tumalo falls#deschutes national forest#creek#river#canyon#landscape#cascade range#tumalo creek#forest#trees#flow#cascade#james marvin phelps photography#flickr

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

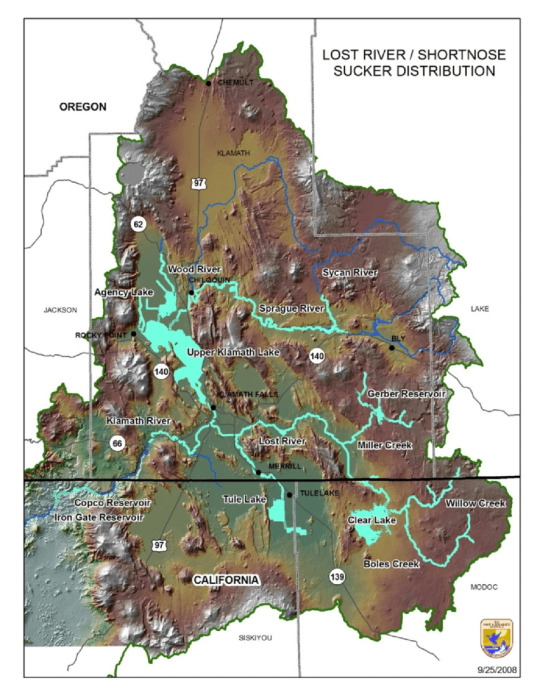

Fish of the Day

The shortnose sucker, Chasmistes brevirostris, is a rare and endangered species in Oregon. Living in the East Cascades in Southern Oregon and Northern California, it can be found primarily in the tributaries of the Upper Klamath Lake, the Lost River, Clear Lake, the Klamath River, and Gerber Reservoir. These are the only remaining areas where these fish can be found, a small area of their original historic range. This historic range also contained Tule Lake, Lower Klamath Lake, Sheepy Lake, and surrounding rivers and streams that branch from these. Their diet consists of small benthic (bottom dwelling) invertebrates and zooplankton in their environment. This allows them to get to sizes of 50cm (20 inches).

These fish favorable conditions are an area with well oxygenated waters (4-10mg/L), shallow lakes, cool temperatures, and plentiful aquatic vegetation. Although they can live in conditions with as low as 1mg/L oxygenated water, this severely impacts the fish as it gives them high stress levels and mortality rates, and can cause spawning issues. This dramatic reaction is being caused by multiple sources: reduction of spawning habitat, dams, insufficient fish ladders, land alteration around waterways. However the largest factor in their decrease has been periodic cyanobacteria blooms, which produce cyanotoxins, and reduce dissolved oxygen in water. These create huge problems for the few populations of shortnose suckers remaining, and it is thought that were it not for conservation efforts, they may already be gone.

Around the age of 6 or 7 shortnose suckers will reach sexual maturity. From February to early May these fish migrate further upstreams to where the water is clear and a gravel bottom can support eggs. During each breeding season females can lay tens of thousands of eggs, around 40,000 They can also spawn and hatch at lakesides, but it has been a rare sight and the conditions that allow for this are currently unknown. The eggs will incubate for 2-3 weeks, and then larvae will flow downstream, usually in vegetation cover or at night time, where they will live out most time along lake edges, where the oxygen is the highest. The first 5 years of their life is when growth is the most rapid, but after reaching sexual maturity they will no longer grow. Their lifespan goes as long as 33 years, longer than most others in these environments.

Have a good day, everyone!

#fish#fish of the day#fishblr#fishposting#aquatic biology#marine biology#freshwater#freshwater fish#animal facts#animal#animals#fishes#informative#education#aquatic#aquatic life#nature#river#ocean

58 notes

·

View notes