#Onmyōji Abe no Seimei

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yandere!Yokai Harem Character Guide

Introducing some of the characters Reader will encounter throughout the story. Get to know your monsters in this handy reference booklet!

Fun fact: The names of the characters are quite literally chapters from ‘The Tale of Genji’, one of the earliest existing novels written in the Heian period by noblewoman Murasaki Shibiku. Kiritsubo and Murasaki are your closest companions and bear the names of the main female characters of the story. (They’re men. A little irony.)

The list will be updated as more characters are revealed:

Abe no Nakamaro 阿倍 仲麻呂

Descendant of famous onmyōji Abe no Seimei, Nakamaro rapidly built his own reputation using the powers of yokai he'd captured across the country. His binding powers have yet to be deciphered. It is believed only his own blood can break the contract forged with the legendary beasts.

Known for his ruthlessness, Nakamaro was feared by humans and demons alike. His commissioned portraits often depict him surrounded by dark clouds - a signature detail - emphasizing his evil nature.

As you progress through your journey, you will be plagued by many flashbacks of his cruel deeds. It's almost as if your own hands are tainted by the blood of the yokai standing before you. You vow to free the beasts and prove you are nothing like the vile creature dwelling within your soul.

Kiritsubo 桐壺

The first yokai you encounter. Despite his intimidating appearance, he is the kindest of the group. He is tall and very muscular, with short, straight horns, long silver hair and glowing amber eyes. When he smiles you can spot his sharp, prominent fangs. He has multiple scars on his back, reminiscent of old punishments.

He is a dragon spirit, although his true powers remain unknown. Nakamaro always kept him close and was particularly strict with him, hoping to unlock his dormant potential, to no avail. He begins to show improvement once he embarks on his journey with you. It seems that his desire to protect his new owner was the secret all along.

Kiritsubo is extremely clingy once he gets to know you better. You're kind and patient and nothing like the famous onmyōji before you. He almost can't believe you're part of his reincarnation. He will follow you around everywhere, like a loyal dog, and might be overly touchy sometimes. He can't help it.

Murasaki 紫

Murasaki is the second yokai you meet. He is tall and slender, with long black hair and imposing horns. His deep crimson eyes hold a lot of resentment towards you, or rather whoever lies within you. Despite this, he always holds a disciplined posture and acts very well-mannered.

He used to be Nakamaro's right hand. He is considered to be the most skilled among the legendary yokai. A master of the sword and possessing unmatched intelligence, he served both as an advisor and bodyguard. Always cold and calculated, he rarely shows any hint of emotion. He seems to be quite sarcastic and arrogant.

He doesn't interact much with you in the beginning. In fact, he's most annoyed by the idea of partnering up with a weak human like you. He offers to train you with the sword and teaches you spells and prayers. Despite his complaints, he always protects you from any danger. As you spend more time together, he slowly opens up and might even show signs of attachment.

Suma 須磨

Suma is the biggest of the legendary yokai, towering over everyone with his gargantuan frame. He has bright red hair and large bull horns, with robust features and fierce eyes. He has many tattoos covering his body, going all the way up to his chin.

Suma is a worshipped guardian of war. He lives for battle and is said to reward bravery and courage. Despite this, he has a very approachable personality. He is loud and easygoing, rarely showing signs of distress. He uses a spear when fighting, although he prefers his bare hands. Brute strength is his specialty.

He finds it hilarious that the feared Abe no Nakamaro has been reincarnated into a small girl. He will often joke around with you and challenge you to playfights. When borrowing his powers, you are able to display impressive feats of physical strength. He likes watching you fight and encourages you to train.

Yuugiri 夕霧

Yuugiri is a mysterious yokai. He is pale with rather feminine features, appearing androgynous. He is very elegant and well spoken, although both Kiritsubo and Murasaki have warned you to be wary of him.

He is a serpent spirit, sly and manipulative. He is known for tricking humans and devouring their souls, yet very few can tell his true nature. He is incredibly charismatic and many people fall in love with him, meeting their early demise.

You cannot read him and therefore keep your distance. His twisted smile never leaves his face. He is very interested in you and while his reasoning might be superficial in the beginning, he does become rather attached and tries to prove his honest feelings to you.

Warning: Spoilers ahead!

Sekiya 関屋

One of the yokai that has remained by Abe no Nakamaro's side, in his resting tomb. He is the one that kept his presence concealed, casting a barrier around the temple for the entirety of his master's slumber.

His main power is casting barriers. Sekiya is the one that guards the entrance and guides you towards the onmyōji for your battle. Once you defeat Nakamaro, he joins your group.

He is very reserved, shy and insecure. He cannot fight properly and often bemoans his lack of purpose. Like Kiritsubo, he falls in love with your kind nature and clings to you, hoping to be of use.

Sakaki 榊

The other yokai to guard Nakamaro's tomb, Sakaki has been tasked to keep his master alive.

He has the ability to heal and even revive under certain circumstances. After your fight against Abe no Nakamaro, he offers to heal your fatal wounds and joins your group.

Sakaki is rather gloomy and depressed by nature. He has an unhealthy obsession with death and often makes grim or unusual remarks. He considers you his muse and will sometimes write unsettling poetry dedicated to you.

#female reader#yandere yokai#yokai x reader#yandere oc#yokai harem#yandere harem#yandere original character#original work#yandere x reader#yandere monster#yandere monster x reader#monster x reader

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

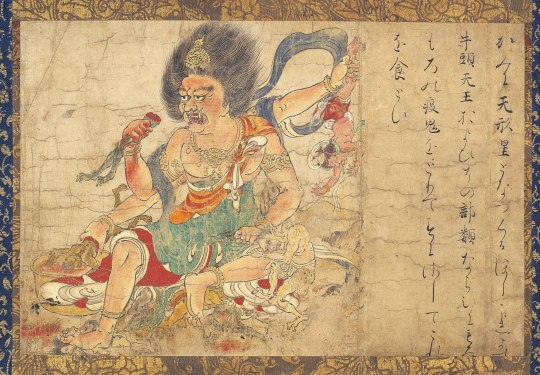

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

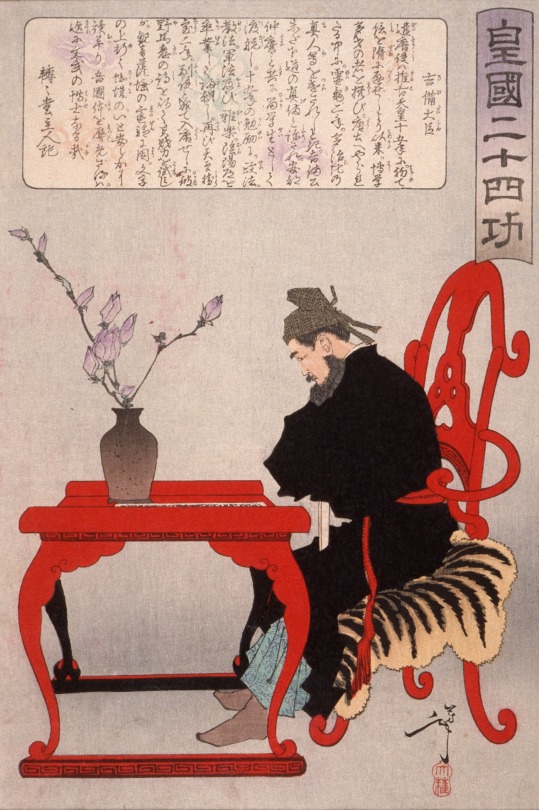

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), “bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances. Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽���). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them. The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

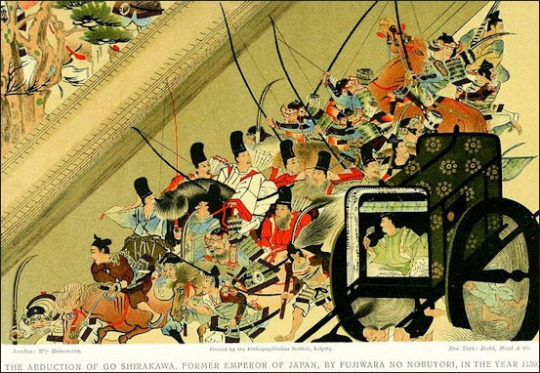

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though. Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender. As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

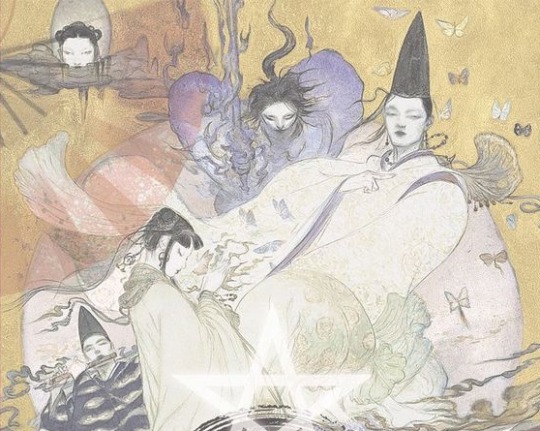

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

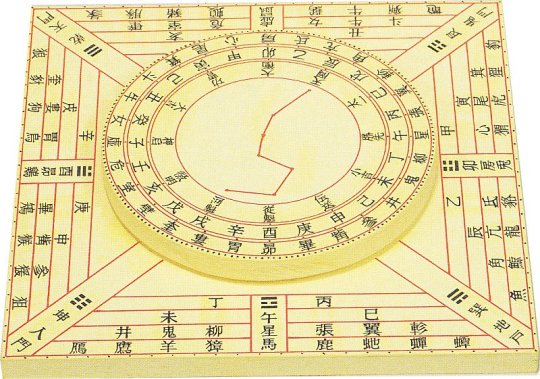

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications. It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (氣). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Akimitsu) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings. A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (続古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

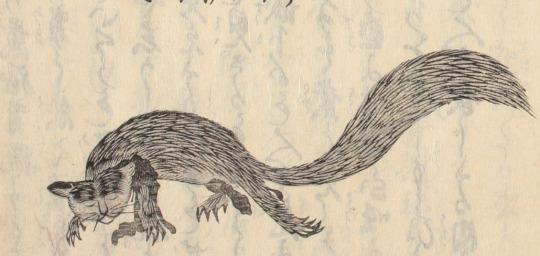

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho. Post scriptum The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive. The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

169 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello who is ashiya douman and who is abe no seimei i’m interested

The TLDR is that abe no seimei is a famous japanese onmyōji (sick ass wizards) from the heian period who has a ton of stories about him and ashiya douman is his evil rival

of course most people know them (specifically douman) from popular mobile game fate/grand order where we believe there was a heian sorcerer who looked like this just walking around

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cursed Ashiya Sword / 妖刀アシュラ

The Cursed Ashiya Sword is a powerful blade with a high Critical stat at the cost of draining the wielder's hit points. The name Ashiya is likely derived from Ashiya Dōman (JP: 蘆屋道満), a practitioner of Onmyōdō (JP: 陰陽道)—a form of divination based around astronomy, calendars and directions with roots in Chinese philosophy and spirituality. Onmyōdō also was regularly interpreted as a form of sorcery called jujutsu (JP: 呪術), and was extended in various stories as allowing the transmutation of objects and animals. During the Heian period (roughly the tenth century), Dōman was the rival to the most famous onmyōji, Abe no Seimei, who served the emperors of the time. Dōman regularly attempted to thwart the younger Seimei to make him less appealing and claim his titles. This dynamic between the two brought upon them the nicknames 悪の道満 (rōmaji: aku no dōman) "Evil Dōman" and 正義の晴明 (rōmaji: seigi no seimei) "Righteous Seimei." Eventually, Dōman lost in a magician's duel against Seimei, and he was banished to Harima Province.

In Japanese, the Cursed Ashiya Sword is called 妖刀アシュラ (rōmaji: yōtō ashura) typically translated as "Bewitching Sword Ashura". The word 妖刀, while literally meaning "a sword with mysterious charm" refers to the common trope of a cursed magical sword that exudes an odd aura. This originates from the legends surrounding swords forged by the famous Muramasa school of swordsmiths. Their swords were known for bein exceptionally crafted and incredibly sharp; such quality attracted the interest of Mikawa Province and Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. However, a series of misfortune soured the Muramasa name across Japan. Across the span of one hundred years, multiple members of the Tokugawa family were harmed or killed by crafts bearing the Muramasa name. Because of this, it was said that Tokugawa Ieyasu banned the use of Muramasa blades. Though this prohibition is most certainly tall-tale, it did not stop the sullying of the Muramasa school with stories of their weapons being cursed. These went so far as to claim Muramasa blades were bloodthirsty monstrosities, created by an insane swordsmith, that could not be sheathed unless it has spilled blood. Some even said the swords would drive men to murder or taking their own lives. These legends are reflected in the Cursed Ashiya Sword's stats and self-damaging properties.

As for the actual name in the sword, the Japanese アシュラ ashura is typically used to refer to the asura, a type of demigod that originates in Hindu folklore that was adopted into Buddhism. Though the asura were not considered purely evil entities, the name often connotates unpleasant characteristics. In Buddhism, they reside in the Kāmadhātu, the "desire realm", chase vices and addictions far easier, are easily corrupted, and have frequently been referred as "demons." In Hinduism, many gods, including Indra and Agni, have been called asura; however, it is suggested that during the war between Indra and Vritra, the asura that sided with good were elevated to the status of Deva, while the rest that joined evil would keep the asura name. It is likely for this demonic association the asura carry that gave their name to the sword-equivalent of a Devil Axe.

This was a segment from a larger document reviewing the name of most every weapon and item in Three Houses and Three Hopes. Click Here to read it in full.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! I remember in one of your previous analyses that you'd love an opportunity to talk about shikigami (I think). As someone who is also quite curious about it, would you mind divulging on the subject?

Oh of course, thanks for reminding me!

Shikigami: From History to Len'en

Shikigami, like barriers (which I also did a Len'en-focused analysis on), is one of those things I feel like many who are into Japanese media, especially traditional fantasies, have a general idea about, yet don't really have a grasp on their real-life conception and history.

So, just like in the barriers post, let's take a look at what shikigami are all about, in real-life history and in the Len'en series!

Origins of Onmyōdō

To understand the origins of shikigami, we first have to have a cursory understanding of the complex art of Onmyōdō (陰陽道 lit. "the way of Yin and Yang").

Roots in Chinese Philosophy

Onmyōdō, as we understand it, has its roots in the Chinese philosophical Theory of Yin-Yang and the Five Phases (陰陽五行思想).

Yin and Yang (陰陽) can be described as the fundamentally opposite but interconnected forces that constitute as well as cause change in everything in the universe.

The Five Phases (五行) is a conceptual framework which is used to classify and explain a wide array of phenomena, including the movement of celestial bodies, the interaction between internal organs to, the rise and fall of political regimes and the properties of medicine, amongst other things. The five phases are, in order, fire, water, wood, metal, earth.

The Theory of Yin-Yang and the Five Phases then combines the two, and was associated with and used for a variety of (what were at the time considered) natural sciences, such as astronomy, calendar making, time keeping and divination.

Development in Japan

When transmitted to Japan alongside Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism, it was accepted by the Japanese people as having actual power, and its associated practices like divination and manipulating fortune were accepted as well.

As these beliefs and practices fused with the native Japanese beliefs (what one may classify as Shinto) and Japanese Buddhism (remember that Buddhism also had its own major developments in Japan), a system of beliefs and practices that were uniquely Japanese was born.

This was Onmyōdō, and it was a state-controlled craft. Onmyōji (陰陽師 lit. "master of yin and yang") were the practitioners of this craft who belonged to the Bureau of Onmyō (陰陽寮), and they offered their services to the royal family and the noble elites.

The Historical Shikigami

Examining the Word "Shikigami"

Now that we can finally take a look at the historical shikigami. They are known by a number of names: shikigami/shikijin (式神・識神), shiki-no-kami (式の神・識の神), shi-ki (式鬼) or shiki-kishin (式鬼神).

No matter the rendering, there is a common element throughout most of them: 式 read shiki or just as shi. It means "to make use of", and refers to the onmyōji's control over these beings.

The specific beings that these names list are kami (神 gods/spirits), oni (鬼) and kishin (鬼神). The last term refers to a myriad of concepts, from wild and rampaging kami to divine spirits to any supernatural thing that causes mysterious phenomena.

Below: Famous onmyōji Abe no Seimei (in black) accompanied by two of his shikigami (below Seimei).

So, from the name, we can tell that shikigami refers to the gods, spirits, supernatural beings and even just supernatural forces under the onmyōji's control. Additionally, it is said that the process through which an onmyōji summons these spirits is also called shikigami..

Types of Shikigami

Shikigami are in fact invisible to everyone except their master, but can take on forms that are visible to the average person. In general, shikigami can be classified in to two ways:

One is according to the form they appear in, such as human-shaped (人型), bird/beast-shaped (鳥獣型), youkai-shaped (妖怪型), etc.

More interesting, perhaps, is classifying them based on how they were created:

First are "mental-action shikigami", (思業式神 shigou-shikigami) they are manifested through the onmyōji's thought, and are said to directly reflect their master's ability.

Next are "personified shikigami" (擬人式神 gijin-shikigami), they are produced by imbuing a doll, often made of paper, straw or plants, with spiritual power. Those which obtain a will of their own are considered higher-rank, while those that do not are considered lower-ranked.

Below: A straw doll used to summon a shikigami into.

Final final type are called, literally, "gods of evil deeds and revealed retribution" (悪行罰示神 akubyoubasshi-kami). It's rather unwieldy and not exactly clear what it means.

So instead, I'll call these "shikigami through karmic retribution". They are typically beings who committed evil deeds in the past who are defeated and subjugated by onmyōji, becoming their shikigami.

The final type, perhaps obviously, are considered particularly dangerous, as an unskilled master can be overpowered by the shikigami, allowing it to cause harm to its master and others.

Functions of a Shikigami

Basically, there's nothing a shikigami cannot do, as they are (provided that the onmyōji is powerful enough) completely bound to the will of their master.

Here I'll just briefly list a few of what shikigami were said to be used for throughout history and myths:

Defeating harmful and devil spirits

Possessing someone to cause them harm

Placed at key locations as protector deities

Pass on messages and deliver objects

Reconnaissance

Housework, house-watching and personal care

Yeah, basically anything you can think of.

Onmyōdō in the Present Day

Persistance and Development

Onmyōdō and onmyōji, along with the Bureau of Onmyō, persisted throughout Japanese history, slowly gaining popularity amongst the general populace as well. It has its ups and down, even losing its official status once, but it never faded away.

One particularly famous Onmyōji that should not go unmentioned is Abe no Seimei (安倍晴明), said to be a genius in the art. Many of his exploits are left behind as legends, and he himself is a popular topic of many modern fiction stories.

Below: Mitori's Pentagram "Bellflower Seal Crush", based on a seal of the same name invented by Seimei to ward off demons.

Fall and Modern Status

It was not until the after Meiji Revolution, in 1870, that the new government passed a bill to ban Onmyōdō as a superstition, under the support of pure Shintoists and the exclusionists, who rejected Onmyōdō based on its Chinese roots.

After this, the Onmyōdō of old basically disappeared from Japanese society. Later, when the ban was lifted, Onmyōdō was already reduced to a point where it would never return to the level of prestige and power it once held during the Heian period.

Nowadays, there are two schools of Onmyōdō left, the "Tensha Tsuchimikado Shinto" (天社土御門神道) and the Izanagi School (いざなぎ流).

Tensha Tsuchimikado Shinto

This school was established by a family that traces it lineage back to Abe no Seimei, the Tsuchimikado Family.

Thanks to its fusion of Onmyōdō and Shinto, it was able to survive the ban on Onmyōdō by leaning on its Shinto side. Though it would lose official support regardless and turn to private practice.

The Izanagi School

A unique folk religion developed independently in the archaic Tosa Province (modern day Kōchi Prefecture). It has elements of Onmyōdō belief and practice, but aren't recognised by Tensha Tsuchimikado Shinto.

Popular Culture

The colourful stories of onmyōji from various legends, especially of them binding youkai to their control and excercising other mystical powers, captured the popular imagination and lead to a myriad of fictional depictions of them.

It is here that the most common depiction of shikigami emerges, as youaki bound by onmyōji, or spirits summoned into paper dolls by them. And it is here that we loop back to Len'en.

Shikigami of Len'en

The most info on shikigami in the Len'en series can be found in Garaiya Ogata's BPoHC profile:

A shikigami receives spiritual power from its master, and can act using the accumulated spiritual power from them. How much spiritual power they can save up and what they can do with said accumulated power varies from shikigami to shikigami. [...] However, the master's spiritual power is naturally limited. [...] However, since a slight amount of their master's power is constantly consumed to keep their shiki up and running. Multiplying too much will overburden their master, ultimately deactivating the shiki.

It would seem that shikigami run on a fairly unique set of rules in Len'en, that of an exchange and balance of spiritual power between master and subject.

The master needs to use their power to somehow activate and maintain a shiki contract with the subject, which creates a link between the two and allows the subject to draw on their masters power. In the case that the master runs out of power, the contract immediately deactivates.

The amount of spiritual power a shikigami stores seems to be somewhat proportional to how powerful they are, as seen in Kuriju Kesa being technically weaker than Kaisen Azuma, but still seen as more useful thanks to the former being better at storing spiritual power from Garaiya.

We don't really know much else about shikigami in the series, though there are a few things that we can speculate upon.

Bound Evildoer Shikigami

First we can examine the most prominent master-shikigami pairs, that between Garaiya and Kaisen & Garaiya and Kurjiu.

Below: Garaiya with Kaisen and Kujiru in animal form.

It's possible that these two are what I called "shikigami through karmic retribution", as they were apparently "pretty mischievous" in the past, prior to meeting Garaiya.

This is particularly likely with Kaisen, as one of their inspirations, the Chinese mythological creature known as Jinchan (金蟾 Lit. "gold/golden toad"), actually has pretty much this play out, just framed under Daoism instead of Onmyōdō.

In the folktale Liu Hai Tricks Jinchan (劉海戲金蟾), it is said Liu tamed a malevolent and greedy three-legged toad after fishing it out of the east sea. It became Jinchan and was henceforth the immortal's companion, following Liu wherever he went.

So yeah, basically "evil youkai does bad deeds" → "good person comes around and tames it" → "evil creature now serves the good person somehow".

With Kujiru, it's not as direct, since their basis, Kesa-gozen (袈裟御前), was the victim in her story, rather than the villain or a villain redeemed. Still, if JynX wanted to somehow collapse both the villain and the victim into one, they certainly can, so I can't really say that this disproves Kujiru as a "shikigami through karmic retribution".

Bonus Note: Jinbei

There's really not enough information on Jinbei to say much about them as a shikigami, but it's interesting to note that they don't (or at least don't only) draw power from their master.

Rather, they draw power from and supply power to the Mugenri Barrier, the current Senri priests (Yabusame and Tsubakura) as well as a yet undisclosed source.

On a personal note, Jinbei gives me the vibe of a spirit that was summoned into an object. Similar to the personified shikigami, though not summoned into a doll, but into the very jinbei that they're always wearing.

Conclusion

There's still much that we don't know about shikigami in Len'en, so other possibilities still exist with both Kaisen, Kujiru and Jinbei.

For example, Kaisen and Kujiru can also be spirits summoned into the youkai, akin to how the Touhou series conceptualises its shikigami. Or Jinbei could be a youkai who's subjugation contract is renewed with every new Senri priest.

Basically what I'm saying is that canonically all we have is the Garaiya profile and the two related 2021 interview answers that I've linked.

In any case though, I hope you at least got something out of the first part about the historical shikigami, and how they are classified and used even to this very day.

As usual, I hope you enjoyed~! :)

#len'en#len'en project#len'en lore#garaiya ogata#kujiru kesa#kaisen azuma#jinbei#jinbei len'en#shikigami#I tried to find english translations for these terms#but like I said#well known in popular culture but not in its historical understanding#so it was difficult to find much about this in english#I'm leaving the “jinbei” tag there#maybe this'll be interesting for the traditional Japanese fashion crowd#who knows?

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

waiting with bated breath for your sasuboru art to come back! hope your graduation film does amazing!

Thank you!!!!! I miss these days so much too Q_Q btw I have already finished my film, here it is https://youtu.be/e2DmnPq-J38 subtitles included This is a pilot episode about a sorcerer who can communicate with spirits. The story is inspired by the Japanese onmyōji Abe no Seimei

youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

latest obsession: demon-hunting "best buddies" from tenth century Japanese aristocracy

(poster from the Chinese audiodrama)

I'm talking about the Onmyōji stories by Baku Yumemakura, which is about on Abe no Seimei, a famous master of onmyōdō who lived during the Heian era in Japan. In Baku Yumemakura's short stories, he is a handsome but eccentric young man who solves mysteries involving ghosts, demons, and other evil occultists. Accompanying him is his friend Minamoto no Hiromasa, a nobleman and musician. The series started in 1988 and has spun manga, movie, and video game adaptations.

As with most of my entertainment, I discovered this franchise because earlier this year a Chinese audiodrama based the series was released. The main voice actors, 袁铭喆/Yuan Mingzhe (Seimei) and 赵成晨/Zhao Chengchen (Hiromasa), are familiar names for the danmei AD crowd, but the story is technically not romantic and not BL, so the play count is rather low despite raving reviews for the production and performance.

(Posters from the audiodrama)

Although there is no explicit romance in the original stories or the adaptations, Baku Yumemakura apparently confirmed that Seimei and Hiromasa love each other but do not know it. In the AD, they really nailed that sense of adoration hovering between the boundaries of friendship and something more.

There are also two live-action Japanese films, Onmyōji released in 2001 and Onmyōji 2 in 2003, which have attracted some English-speaking fans to the franchise. Since I never read the original novels, I only know the characters' personalities from the adaptions, which already vary between versions. Hiromasa has very intense himbo vibes from the movies, while Seimei feels a more overpowered and other-worldly in the AD.

I have been happily indulging in the fanfics while I take a break from reading original novels. I'm super happy and grateful that a seemingly small fandom has such so many prolific writers!

#danmei faves#well not exactly danmei#not done reading yet#other media appreciation#audiodrama recommendation

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Baku Yumemakura's Onmyōji Anime (Coming 2023)

The stories take place in a fictional version of Japan's Heian period, and center on the real-life onmyōji Abe no Seimei, a legendary figure in Japanese folklore known to be a leading specialist in astrology, science, divination and magic. He’s like a Japanese Merlin who serves the Emperor.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shinoda no Mori Kuzunoha Inari Shrine

I went to get my friend one of their paper maché fox sculptures, as well as an Ofuda and Omamori. This shrine enshrines quite a few Kami, but the one I thought was the most interesting was 若宮葛ノ葉姫 Wakamiya Kuzunoha Hime, the mother of Abe no Seimei a famous court Onmyōji. It was found out she was a kitsune, and she left her son behind. A very sad story, but an example of a kitsune story where the kitsune was benevolent.

Inari Shrines often have Buddhist elements, and this shrine was no exception, I found some Kannon statues and a statue of a Buddhist monk on the grounds.

And finally the shrine items and Goshuin

0 notes

Text

I suddenly recalled an interesting dream I had a few years ago.

In the dream, I was the sole owner of a tavern in one of those JRPG worlds. It was in a small, presumably significant rural town, so it wasn't that big and I could see all of the main room from behind the bar. I had a backroom where the kitchen was, and there was an upstairs where there were a few rooms for rent along with my own living quarters.

Business was sparse, with only a few passing adventurers staying for a drink before moving on. Sometimes, a critically injured person at a party needs a place to stay a night or two. There was a world-threatening war or event or whatever going on in the setting that I'd hear a bit about from guests, but it wasn't my problem. I was just a tavern owner. I enjoyed my quiet time and helping the few who needed me.

Anyways, one day, this guy I've never seen before enters and comes up to the bar. I don't remember what he looked like other than that he had a pretty face and a funny hat, but he identified himself as Abe no Seimei. He told me that my tavern was (in)conveniently located at a key point of some leyline or whatever and asked if he could do something in the main room. I don't really know what exactly he was talking about, but whatever he said told me he was going to disrupt my business, so I told him no. He tried to tell me that whatever he wanted to do was important to his quest, so I asked him how long he would need the room. He tells me he wants to install some kind of permanent fixture, which I decree as unacceptable because I have carefully designed this room to be nice and cozy! I do not need your magical mumbo jumbo ruining my vibes! I tell him to figure something different out and go away. He then leaves politely.

The next day, some different guy comes in. I don't remember a single thing about his appearance other than he looks younger than 18 years old, but he claims to be a disciple of Seimei. This kid demands that I give the tavern over to him. Naturally, I tell him no and kick him out.

The kid comes back later, same demands, but, this time, he brought some weird paper talismans. He says he will curse me if I don't give him the tavern. This time, I dump a bucket of water over him and throw him out again before he finishes his incantation.

Some more time passes, and some adventurers come in. They tell me that they saw some little onmyōji has been wandering outside my tavern saying that my tavern is cursed and they shouldn't talk to me. Since these are adventurers, they just had to come in and talk to me. I tell them that there is no curse and they become disappointed, but now I am concerned if this kid is going to be targeting my customers, so I ask the adventurers to fetch me some books about onmyōdō and I'll give them money and drinks (wow! a quest!). Don't let the little boy out there know. The adventurers complete the quest, and I do some studying.

After understanding the gist of certain things, I set up a defensive barrier around my tavern. Conveniently, there's a lot of mana to sustain it because, that's right, my tavern is on a leyline junction. A few days after I do this, the boy comes back into my tavern, and he's very surprised that I've figured out how to set up a sustained territory despite supposedly being just a rural tavern owner. Fool! This is my dream avatar! I was, at the time of this dream, a college student with a high GPA! This is essentially an isekai scenario! I am much smarter than I let on! But he doesn't need to know this, so I tell him to shut up, leave me and my business alone, and to get out before I kick his ass. The boy is fuming but he leaves. I wonder where the hell his parents are, but, hey, this is an RPG setting. Lone teenagers are everywhere.

A few days later, Seimei comes back in. I tell him to get out because I'm still not interested. He comments on the magic barrier, similarly impressed by the quality despite my lack of background. Hey, I only figured this out and put it up because his disciple has kept bothering me. Seimei becomes confused and says he doesn't have any disciples. What. Then who was that kid? Could be a fan or stalker, he has a lot of those. Dang, the heck? Seimei apologizes for the freak, and buys a drink. He can still be a normal customer, right? Well... I guess.

Seimei proceeds to sit down at a table and orders drinks and snacks. Mostly drinks. At first, I'm not bothered, but, after several hours, I realize that he's just going to keep buying drinks and snacks just so he can stay, and, in the meantime, he's working on some kind of magic artifact. Suspicious, I ask him what he's working on, and he says it's something to tap into the leyline to summon... something. He talks unclearly. He then diverts the conversation by asking if I'm interested in learning more magic arts. He thinks I have some talent in it and maybe I could be his disciple hahaha. Uh, no. He then asks if I would rather prefer to be his wife. Uh. No. This man is just trying to look for ways to stay, huh? After he finishes his drink, I kick him out.

Next day, Seimei comes back, dragging along the kid by the collar of his shirt and forces him to apologize to me. The kid does just seem to be someone who greatly admires Seimei and wants to help him... but he also calls me mean because I always kick him. Hey, maybe if you weren't always trying to curse me!! Seimei shakes the kid down and gets him to hand over all the cursing talismans he had and gives them to me. I could stick these on unruly patrons or something, or make a cursed drink to serve to said bad patrons. He proceeds to ask me for a kiss as a reward. When I tell him no, he asks for a hug. I tell him no again. Headpat? Sir, aren't you too tall and old for a headpat? ...I end up giving him a headpat, and I force the two to leave.

(I end up sticking all the talismans on a bottle of wine before locking it away in a safe. That thing becomes chock full of curses, and I do think I end up serving it to someone later, but I don't remember who.)

After this, Seimei became a "regular" to my tavern, always sitting at the same table and order drinks in large quantities. Somehow, he never gets drunk. Sometimes, the kid also comes, but, instead of demanding I give my tavern over, he now demands I marry Seimei. He thinks that Seimei is interested in me because I secretly also have some kind of talent or blood or whatever, and the whole leyline-location business was a ruse. The man himself doesn't seem to mind this shift in goals, but I certainly do. They keep disrupting my business!! You'd think a famous person like him would do something about the world-ending thing over there, but he's just here. What the hell. They do both eventually give up and leave ?permanently?, but it still was annoying at the time.

Anyways, this dream is the reason why any Abe no Seimeis I encounter in the media are hit with an opinion nerf: because the one in this dream was annoying, all the other Seimeis are more bothersome by association.

#Miscellaneous#i thought to post this in my other blog#but you know what its sort of related to my recent poll

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello.

Do you think I can request headcanons for Nakamaro ?

Like in an alternate route, reader and him (he's in his twenties because... magic ?) are married and reader is pregnant.

But the funny thing is, Nakamaro can't bully the yokais because reader will exorcise him each time he tries.

Aaaaah I finished writing and only afterwards it occurred to me you might've wanted a modern day reader for this. 😭 I imagined the events in his own timeline. Oh well. I think it can work both ways. Just replace the ancient pouch with, I don't know, a visa card that he throws at your parents for wife payment.

Yandere! Onmyōji x Reader

Yokai Harem AU as the wife of Abe no Nakamaro, a legendary sorcerer and collector of yokai. Although you're not quite as powerless as to not keep his cruelty under control.

Content: female reader, arranged marriage, mentions of pregnancy

[Main Story] [Character Guide]

Your family had vehemently opposed the marriage. To think their one and only daughter would fall into the hands of such a cruel man. The famous Abe no Nakamaro, descendant of Abe no Seimei himself, has quite a contradicting reputation. He has saved many lives, cured countless illnesses, protected villages from monsters and brought peace to the land. Yet many have also witnessed his ruthless nature: the arrogance he has towards humans, the disdain and utter disgust he harbors towards demons. He is quick to punish, rarely forgives, and never forgets. The yokai he’s captured under a binding contract are kept on a leash, like cattle before slaughter.

It is this man who approached your parents one day, when you were still young, demanding your hand. He claimed you had special powers and a lot of potential under the right guidance. Such spiritual prowess would waste away in a family of plebeians. You don’t remember much of the discussion, only the expressions: the man’s mocking grin as he threw a pouch fattened with coins, the frown of your parents who wanted to refuse, the uneasy, grim eyes of the horned demons brought to intimidate. It was clear they were there against their will. One will find just how difficult it is to go against the wishes of the onmyōji, and you happened to be his most ardent desire. Thus, with a heavy heart, you’d been sent away with the stranger who promised you were to live a life of luxury. One your parents could never afford.

True to his word, you have not struggled since. In Akutagawa’s short masterpiece, Hell Screen, artist Yoshihide is wicked and vicious towards everything and everyone except his beloved daughter. Similarly, the sorcerer seems to have a soft spot for you in particular. He often praises your talent, and patiently caters to your whims without complaint. You once inquired about it yourself, as the idea weighed heavily on your mind: why is it that he does not show the same hostility towards you? He stared at you as if you just grew two more heads. "You're my wife. What else is there to question?"

This favoritism, however, is to the benefit of everyone. Especially to the yokai under his command. You've grown rather fond of the demons in your years spent alongside them, and they've quickly learned that your presence means safety from any punishment. Some need reassurance more than others. To these you've even begun to feel like a motherly figure, shielding them from the wrath of an unforgiving master. At last, an authority even Abe no Nakamaro himself can't disobey: the word of his wife.

And soon enough, as if your marriage wasn't already the ultimate argument, you welcome the return of your husband with the news he's always longed for: you are the soon-to-be mother of his child. His name has just been guaranteed to continue its course through time. To say he is elated is an understatement. You've only seen him smile so genuinely once before in your life, on your wedding day.

"Can you imagine the powers this child will command?" He muses, referring most likely to the fact you've both been blessed with an innate, unmatched talent in onmyōdō. You finish rolling the parchment paper and gently tap his head with the scroll in a scolding manner. "You better not burden the kid with your bizarre expectations!" The same man feared throughout the country is chuckling apologetically at your gesture. "As the Mother says."

#yandere#yandere yokai harem#yokai harem#yandere onmyoji#yandere x reader#yandere x darling#yandere x you#yandere male#yandere headcanons#yandere imagines#yandere scenarios#yandere oc x reader#yandere oc#female reader

683 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know why Abe-no-Seimei became so popular compared to any other onmyoji in folklore and literature? Is it because of who wrote his stories or something else?

There is no single clear answer. It seems safe to say there are multiple interconnected factors at play.

Seimei’s real career was genuinely extraordinary in some regards. To begin with, it was unusually long. He was around 85 years old when he passed away, and historical sources would indicate that he was still fairly active in old age (in fact, most references to him which are fully verifiable come from the second half of his life). Shin’ichi Shigeta actually argues here that Seimei's longevity in no small part contributed to cementing his legend.

However, it’s hard to argue that the times when Seimei lived were not a factor in its own right too. Institutional backing was no longer the sole reason behind the relevance of individual onmyōji. As I discussed in my recent article, by the middle of the tenth century their clientele expanded. And to find new clients, personal charisma was necessary. The shift started slightly earlier already but it doesn’t seem like the likes of Shigeoka no Kawahito or Kamo no Tadayuki left quite as much of an impression as Seimei and his contemporary Kamo no Yasunori in the long run. Legends do deal with earlier onmyōji at times, or rather reinvent earlier figures, especially Kibi no Makibi, as onmyōji, but this is often merely a way to make Seimei’s or Yasunori’s deeds appear even more amazing by making them a part of centuries old legacies (granted, standalone tales of Makibi appear for example in Konjaku Monogatari already).

Seimei’s personal influence is evident in the fact that he seemingly was responsible for popularizing formerly obscure Taizan Fukun no sai as one of the main onmyōdō rituals (check Shigeta’s article above for more specific evidence). Note that this was a performance so popular the early medieval reinterpretation of Amaterasu was in no small part driven by efforts to make her fit into rituals similar to it and Enmaten-ku. There’s also evidence that Seimei had an impact on the popularity of tsuina, a ceremony originally held only in the court but later also in private houses of nobles which served as a forerunner of modern setsubun.

The Abe clan remained influential in official onmyōdō circles long after Seimei’s death, and his heirs obviously invoked his fame to validate their own influence. There are texts only compiled after the Heian period which were attributed to him, such as Hoki Naiden. This obviously further contributed to the spread of his legend, making him relevant even as onmyōdō changed.

I don’t think it matters who wrote down the legends though, at least not before the Edo period. However, there are at least some individual elements which absolutely became such a mainstay of modern portrayals of Seimei because of the fame of specific authors who introduced and/or popularized them. A good example would be the Kuzunoha story, which was only invented in the 1600s and attained popularity because of Ryōi Asai’s Abe no Seimei Monogatari (I am not aware of any older legend claiming Seimei was not fully human, unless you want to count the Shuten Dōji variants presenting him as a manifestation of Kannon or Nagarjuna). Another thing which comes to mind as an example of influence of specific works of fiction is portraying Dōman as older than Seimei, which is a convention started by Edo period theatrical performances as far as I know. Dōman's historical counterpart was pretty obviously younger (granted, there's also no evidence he interacts with Seimei). He was still active three years after Seimei’s death, and there’s no indication he was somehow 90+ years old.

Bit of a digression but it’s worth noting Dōman isn’t Seimei’s only rival in the early stories, in Konjaku Monogatari he also faces a certain “fearsome fellow” named Chitoku who does seem to be older than him. He is an unlicensed onmyōji and comes from Harima, so it's easy to draw parallels with Dōman. However, they aren’t really similar characters; while Dōman is pretty firmly portrayed as a shady figure - a curse specialist first and foremost - Chitoku actually seems to utilize his skills to deal with pirates troubling his area. He just learns he’s a big fish in a small pond after unsuccessfully challenging Seimei. Still, I wonder if the two may have merged at some point in popular imagination.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kuon researching part 2

Synopsis

Setting

Kuon takes place in and around Fujiwara Manor, an estate in Kyoto, Japan during the Heian period. Central to the plot are two magical Mulberry trees planted near the present Fujiwara Manor by the Hata clan. The trees birth silkworms which weave cocoons around the dead and resurrect them. The resurrection can only be sustained by merging with other living beings, including humans, and absorbing their "grudge". The ultimate goal of the Mulberries is to perform the merging nine times, completing the Kuon Ritual and birthing a being which will become a new Mulberry.

Heian period

The Heian period (平安時代, Heian jidai) is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kammu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto). Heian (平安) means "peace" in Japanese. It is a period in Japanese history when the Chinese influences were in decline and the national culture matured. The Heian period is also considered the peak of the Japanese imperial court, noted for its art, especially poetry and literature. Two types of Japanese script emerged, including katakana, a phonetic script which was abbreviated into hiragana, both unique syllabaries distinctive to Japan.

Character

Many of the characters are either qualified or trainee onmyōji—referred to in the English version as exorcists—practitioners of mystical onmyōdō powers. A key character and antagonist is Ashiya Doman, an ambitious onmyōji who becomes fascinated by the Mulberry tree and the Kuon Ritual. The playable characters are Utsuki, Doman's daughter who lives near one of the Mulberry trees with her sister Kureha; Sakuya, an onmyōji-in-training and one of Doman's apprentices; and Abe no Seimei, a master onmyōji and Doman's rival.

Plot

The narrative is split into three parts; the "Yin" phase following Utsuki, the "Yang" phase following Sakuya, and the unlockable "Kuon" phase following Abe no Seimei. Utsuki and Kureha arrive at Fujiwara Manor from their home in search of Doman. Utsuki is soon separated from Kureha, and must defend herself from the many monsters roaming the grounds.

Sakuya arrives with three of Doman's disciples, including her brother, to investigate the recent rumors of terrible incidents. As they investigate, Sakuya fights off the monsters, and two of the disciples are killed and corrupted by the monsters.