#Nicola Benois

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Il costume teatrale tra realismo e finzione

I costumi storici del Teatro alla Scala dagli anni '30 agli annni '60

a cura di Francesca Colombo e Christian Silva

Teatro alla Scala, Milano 2003, 181 pagine , 28,5x28,5cm, english text inside

euro 40,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

25/10/24

#costume teatrale#Teatro alla Scala#dagli anni '30 agli anni '60#theatrical costumes#Nicola Benois#Attilio Colonnello#Mario Bellani Marchi#Caramba#Salvatore Fiume#Piero Zuffi#Alessandro Benois#Nicola benois#fashionbooks#fashionbooksmilano

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Signorelli, una vita tra le marionette

Una delle artiste più note del teatro del Novecento italiano… Maria Signorelli nacque a Roma il 17 novembre 1908 e fin dall’infanzia assorbì le suggestioni che arrivavano dall’ambiente familiare e dal salotto che suo padre, Angelo, e la madre, Giga Resnevic, appassionata di teatro e biografa della Duse, tennero per anni nella loro casa. Dopo il liceo Maria si iscrisse all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Roma al corso di scenografia del Teatro Reale, diretto da Nicola Benois. A vent’anni la Signorelli creò i primi fantocci, che erano sculture morbide, nate da molteplici suggestioni, che andavano dal Manifesto tecnico della scultura futurista di Boccioni al Manifesto del tattilismo di Marinetti, ma anche dai manichini metafisici di De Chirico, dalle marionette di Depero, Klee o Alexandra Exter, e vennero esposti per la prima volta nel 1929 alla Casa d’Arte Bragaglia. Ad una successiva mostra alla Galleria Zak di Parigi, presentata da De Chirico, seguì un lungo soggiorno di Maria a Berlino con una nuova mostra alla Galleria Gurlitt. Tornata in Italia, la ragazza iniziò a collaborare come scenografa con Anton Giulio Bragaglia al Teatro degli Indipendenti e poi al Teatro delle Arti di Roma. Nel 1934 ideò con Carle Rende il Pluriscenio M, un teatro dove l’azione poteva svolgersi in contemporanea su sette palcoscenici, che fu molto apprezzato da Bragaglia e lodato da Marinetti e nel 1937, per La boîte à joujoux su richiesta della cantante Maria Amstad, creò, per la prima volta, delle marionette che agirono sul palcoscenico. Maria nel 1939 sposò il pedagogista Luigi Volpicelli e, pur continuando l’attività di scenografa, nel 1947 fondò la compagnia L’Opera dei Burattini, dove collaborarono attori, pittori, scenografi, compositori, registi, da Lina Job Wertmuller, Gabriele Ferzetti ad Enrico Prampolini, Ruggero Savinio e Toti Scialoja ad Ennio Porrino e Roman Vlad a Margherita Wallmann e Giuseppe De Martino. Nel suo repertorio ci furono opera come Re cervo (Gozzi). La favola del pesciolino d’oro (Puskin) L’Usignolo e la rosa (Wilde), La tempesta (Shakespeare), Faust (Bonneschk), l’Inferno di Dante, La Rivoluzione Francese (Ceronetti), Antigone (Brecht) il suo particolare virtuosismo nel concepire burattini-ballerini rese celebri lavori come Cenerentola (Prokof’ev), El Retablo de Maese Pedro (De Falla) e La boîte à joujoux (Debussy). All’intensa produzione, alle centinaia di burattini creati con soluzioni geniali e nel contempo semplici e raffinate, Maria affiancò un notevole impegno didattico, insegnando dal 1972 nel corso di teatro di animazione appositamente istituito per lei al Dama di Bologna, creando trasmissioni radiofoniche e televisive, come Serata di gala, Piccolo mondo magico, Pomeriggio all’Opera, lavorò a conferenze e articoli su periodici e riviste, oltre a scrivere libri, tra tutti Il gioco del burattinaio. Con la sua importante collezione, ricca di migliaia di pezzi dal Settecento al Novecento, curò l’allestimento di un gran numero di mostre in Italia ed all’estero sul Teatro di Figura. Membro del Consiglio Mondiale dell’Unima, la Signorelli fondò l’Unima Italia nel 1980, di cui fu Presidentessa onoraria fino alla sua scomparsa, avvenuta a Roma il 9 luglio 1992. Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

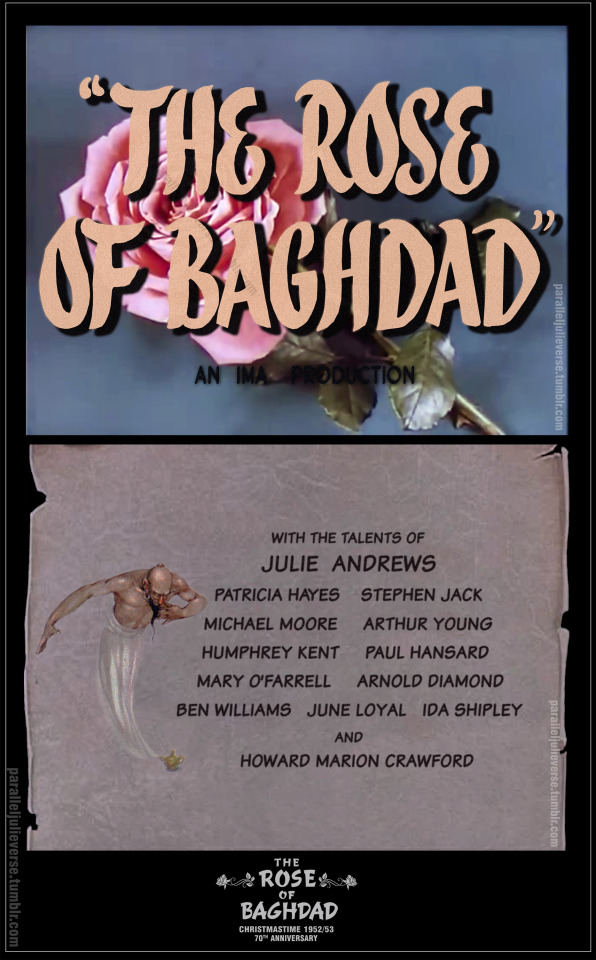

‘Who is queen of all the garden?’: 70th anniversary of The Rose of Baghdad (UK version) Christmastime 1952/53

Ask almost anyone the name of Julie Andrews’ first film and the automatic response will be: “why, Mary Poppins...of course!” It’s part of Hollywood folklore that, having been passed over by Jack Warner for the film adaptation of My Fair Lady because she wasn’t a ‘proven movie star’, Andrews was offered the title role of the magical nanny in Walt Disney’s classic 1964 screen musical. It earned Andrews a Best Actress Oscar straight off the bat and catapulted her to international stardom as Hollywood’s musical sweetheart. Her film debut in Mary Poppins has even been a question in the ’easy’ category on Jeopardy! (Answered correctly, natch, for $100 by Steven Meyer, an attorney from Middletown, Connecticut).

But, with all due respect to Alex Trebek and general knowledge mavens everywhere, Julie's very first film actually came out more than a decade before Mary Poppins. In 1952, when the young star was just 16 going on 17, she was cast to voice the lead character of Princess Zeila in the UK version of the Italian animated film, The Rose of Baghdad.

It’s an easily overlooked part of Andrews’ oeuvre, figured, if at all, as a minor footnote to her later Broadway and Hollywood career. But The Rose of Baghdad was a not insignificant stepping stone in Andrews’ rise to stardom and one, moreover, that prefigures important aspects of her later screen image. So, on the 70th anniversary of the film’s British release, it is timely to look back briefly at The Rose of Baghdad.

La rosa italiana

Produced and directed by Anton Gino Domeneghini, The Rose of Bagdad -- or, in its original title, La rosa di Bagdad -- was the first feature-length animation ever made in Italy and also the country’s first Technicolor production. As such, it commands a prominent position in Italian film history (Bellano 2016; Bendazzi 2020).

La rosa di Bagdad was a real passion project for Domeneghini, a commercial artist and businessman with a successful advertising company, IMA, headquartered in Milan. During the 30s, Domeneghini’s firm handled the Italian marketing for many major international clients including Coca-Cola, Coty, and Gillette (Bendazzi: 23). With the outbreak of WW2, the advertising industry in Italy was effectively shut down. In an effort to keep his company afloat, Domeneghini rebranded as a film production company, IMA Films.

Inspired by the success of animated features from the US such as Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937) and the Fleischer Brothers’ Gullivers Travels (1939), Domeneghini decided to produce an Italian animated film that could emulate the crowd-pleasing dimensions of American imports but with a distinct Italian sensibility (Fiecconi: 13-14). He threw himself heart and soul into the endeavour.

Based on an original idea developed from various stories Domeneghini had enjoyed as a boy, La rosa di Bagdad was conceived as an orientalist fairytale pastiche. The plot was patterned loosely after the Arabian Nights, complete with an Aladdin-style boy minstrel, a mystical genie, tyrannical sorcerer, and a golden-voiced princess. But it was embroidered with a host of other elements from assorted folktales and pop cultural texts.

To oversee the production, Domeneghini handpicked a core creative team including a pair of stage designers from La Scala, Nicola Benois and Mario Zampini, and a trio of head artists: animator Gustavo Petronio, caricaturist Angelo Bioletto, and illustrator Libico Maraja (Bendazzi: 23). They helped craft the film’s distinctive aesthetic with its striking blend of comic character-based animation and figurative exoticism of the Italian Orientalist School of painters such as Mariani, Simonetti, and Rosati (Fiecconi: 17).

Music was crucial to Domeneghini’s vision for the film. Fiecconi (2018) asserts that “the original creative part of the movie lies in the musical moments where the film seemed to celebrate the Italian opera” (17). Domeneghini commissioned the celebrated Milanese composer, Riccardo Pick-Mangiagalli, to write the film’s musical score. It would be the composer’s last complete work before his untimely death at age 66 in early-1949 and it has been described as something of “a summa of Pick-Mangiagalli’s art” (Bellano: 34). Combining Hollywood-style romantic underscoring with Italian and Viennese classicism, Pick-Mangiagalli composed a broadly operatic score replete with arias, waltzes, and orientalist nocturnes.

Given the difficulties of wartime, the production process for La rosa was long and arduous and the film took over seven years to complete. At various stages, more than a hundred production staff worked on the film, including forty-seven animators, twenty-five ‘in-betweeners’, forty-four inkers and painters, five background artists, and an assortment of technicians and administrative assistants (Bendazzi: 25). Colour processing was initially done using the German Agfacolor system but it produced a greenish tint that was not to Domeneghini’s liking. So after the war, he took the film to the UK where it was reshot in Technicolor at Anson Dyer’s Stratford Abbey Studios in Stroud (Bendazzi: 24).

La Rosa di Bagdad finally premiered in 1949 at the Venice Film Festival where it won the Grand Prix in the Films for Youth category. The following year, the film was given a general public release in Italy. Leveraging his professional training as an ad man, Domeneghini crafted an extensive marketing and merchandising campaign for the film that was unprecedented at the time (Bendazzi: 30). It helped secure decent, if not spectacular, commercial returns for the film in Italy and encouraged Domengheni to shop his film abroad to other markets in Europe (Ugolotti: 8).

The English Rose

It was in this context that a distribution deal was brokered in early-1951 with Grand National Pictures in the UK to release La Rosa di Bagdad to the British market (’Many countries’: 20). Not to be confused with the short-lived US Poverty Row studio whose name -- and, even more confoundingly, logo -- it adopted, Grand Pictures was an independent British production-distribution company established in 1938 by producer Maurice J. Wilson. While it produced a few titles of its own, Grand National was predominantly geared to film distribution with an accent on imported product from the Continent and Commonwealth countries (McFarlane & Slide: 301).

Retitled The Rose of Baghdad, the film was part of an ambitious suite of twenty-six films slated for distribution by Grand National to British theatres in 1952, the company’s “biggest ever release programme” (’Grand National’: 16). The screenplay and musical lyrics were translated into English by Nina and Tony Maguire, and a completely new soundtrack was recorded at the celebrated De Lane Lea Processes studio in London (Massey 2015).

To do the voicework for the English-language version, Grand National assembled a roster of diverse British talent from across the fields of theatre, radio and film. The distinguished BBC actor Howard Marion-Crawford lent his sonorous baritone to the role of the narrator. RADA graduate and popular radio comedienne, Patricia Hayes voiced Amin, the teenage minstrel. Celebrated stage and film star, Arthur Young voiced the kindly Caliph, while rising TV actor Stephen Jack provided a suitably menacing Sheikh Jafar.

The biggest and most publicised name in the line-up, however, was Julie Andrews 'enacting’ the role of Princess Zeila. Much was made of Julie’s casting, and she was the only member of the British cast to be given named billing on the film’s poster and associated marketing materials. Scene-for-scene, her role wasn’t necessarily the biggest. Other characters have more lines and more action. But, as the symbolic “rose” of the film’s title and the focus of narrative attention, Julie as Princess Zeila had to carry much of the film's emotional weight.

And, musically, Princess Zeila certainly dominates proceedings. Her character is meant to posses a golden voice of rare enchantment and the film showcases her virtuosic singing in several key scenes. As mentioned earlier, composer Riccardo Pick-Mangiagalli imbued the score with a strong operatic flavour and this is nowhere more apparent than in the three coloratura arias that he penned for Zeila: “Song of the Bee”, “Sunset Prayer” and the “Flower Song”. In the original Italian release, the part of Zeila was sung by Beatrice Preziosa, an opera soprano of some note who performed widely in the era with the RAI and had even sung opposite Gigli (Bellano: 35).

In her 2008 memoirs, Julie recalls the challenge of recording the Pick-Mangiagalli score:

“I had a coloratura voice, but these songs were so freakishly high that, though I managed them, there were some words that I struggled with in the upper register. I wasn’t terribly satisfied with the result. I didn’t think I had sung my best. But I remember seeing the film and thinking that the animation was beautiful. I’m pleased now that I did the work, for since then I don’t recall ever tackling such high technical material” (Andrews: 143-44).

The Rose opens

The British version of The Rose of Baghdad had its first public screenings in September of 1952 at a series of trade events organised by Grand National to market the picture to prospective exhibitors. The first such screening was on 16 September at Studio One in Oxford Street, London, followed by: 17 September at the Olympia in Cardiff; 19 September at the Scala in Birmingham; 22 September at the Cinema House in Sheffield; 23 September at the Tower in Leeds; 25 September at the Theatre Royal in Manchester; and 26 September at the Scala in Liverpool (’London and provincial’: 32; ’Trade show’: 14).

In promoting the film, Grand National pitched The Rose of Baghdad as wholesome family fare perfect for children’s matinees and double features. “A fascinating cartoon to enchant audiences of all ages” was the campaign catchline. They especially plugged the film’s potential as a seasonal attraction with full-page adverts in trade publications that billed it as the “showman’s picture for Christmastide”.

One of the film’s first UK reviews came out of these early trade screenings with Peter Davalle of the Welsh-based Western Mail newspaper filing a fulsome report:

“Ambitious in scale as anything that Disney has conceived...it has very right to demand the same intensity of judgement conferred on the Hollywood product. I have little but praise for it and I hope my enthusiasm will infect one of the country’s cinema circuit chiefs to the extent of giving it the showing it deserves” (Davalle: 4).

Ultimately, the film was unable to secure an exhibition deal with a major cinema chain. Instead, it was given a patchwork release at various independent and/or unaffiliated theatres across the country.

The Tatler theatre in Birmingham proudly billed its 14 December opening of The Rose of Baghdad as the film’s “first showing in England”. Archive research, however, evidences that it opened the same day at several other provincial theatres such as the Classic in Walsall (’Next week’: 10). Other notable early openings included the Alexandra Theatre in Coventry on 22 December -- the day before Julie premiered in the Christmas panto, Jack and the Beanstalk at the Coventry Hippodrome -- and the News Theatre in Liverpool and the Castle in Swansea on 29 December.

The film’s initial London release was at the Tatler in Charing Cross Road where it had a charity matinee premiere on 28 December sponsored by the West End Central Police with 470 children in the audience from the Police Orphanage (’Pre-release’: 119). The film then continued a chequerboard rollout across the UK throughout early-1953 with concentrated bursts around school holiday periods.

Because of the fitful nature of the film’s release pattern, The Rose of Baghdad didn’t attract sustained critical attention, though there were short reviews in various newspapers and publications. The critical response was lukewarm with reviewers finding the film pleasant, if lacking in technical polish. Most praised the English soundtrack with generally kind words for Julie:

The Times: “This Italian cartoon, ‘dubbed’ into English, proves once again how much more happy and at home the medium is with animals than with human beings. Mr. Walt Disney never did anything better than Bambi, which was given entirely over to the beasts and birds of the forest, and the Princess Zeila, the rose of Baghdad, proves just as unsatisfactory a figure as Snow White and Cinderella. The fault is that not of Miss Julie Andrews, who speaks and sings the part; it seems inherent in the medium itself...The Rose of Baghdad is not, however, without some delightful incidentals (’Entertainments’: 9).

The Observer: “Intelligently dubbed English version of full-length Italian cartoon...Nice use of crowds and minarets; one or two brilliant shots...; variably jerky animation; trite comedy; chocolate box princess...Not at all bad, a little too foreign to be cosy” (Lejeune: 6).

Picturegoer: “Charm stamps this full-length Italian cartoon, dubbed in English. Technically, it hardly bears comparison with the best of Disney. But it has genuine freshness and some appealing character studies...There is a delicate, very un-jivey musical score, and Julie Andrews sings attractively for the princess” (Collier: 17).

Photoplay: “The under 20′s and the over 50′s will love this one...Young B.B.C. star Julie Andrews ‘enacts’ the role of the Princess and sings three of the film’s seven tuneful songs....Yes, you’ll love this -- make it a must” (Allsop: 43).

Kinematograph Weekly: “Refreshing, disarmingly ingenuous Technicolor Arabian Nights-type fantasy, expressed in cartoon form. Made in Italy and expertly dubbed here...It hasn’t the fluid continuity nor flawless detail of Walt Disney’s masterpieces, but even so its many charming and novel characters come to life and atmosphere heightened by tuneful songs, is enchanting” (’Late review’: 7).

Picture Show & Film Pictorial: “Such a charming mixture of heroics, villainy and romance should not be missed, and although the animation is not as good as first-class American cartoons, the colour and the songs are delightful” (’New Release’: 10).

The Birmingham Post: “[A]n Italian cartoon in colour which equals Disney in artistic invention though not in smooth animation...Fancy flies high but always it takes us with it. Much of the colour work is beautiful...The characters remain always between the covers of the story book, but within their limited living rom they are a gay and enterprising company” (T.C.K.: 4).

Coventry Evening Telegraph: “It would be difficult to find a more delightful fantasy for Christmas entertainment than “The Rose of Baghdad” (Alexandra) -- the new Italian full-length cartoon. Until recently, Hollywood held an unbreakable monopoly in this field of coloured picture making. Now we have the opportunity to see a new and refreshing approach to the subject...All dialogue has been English-dubbed and appropriately enough Julie Andrews, who opens in Coventry pantomime tonight, sings and speaks the part of the little princess Zeila” (Our Film Critic: 4).

Faded Rose

The Rose of Baghdad continued to pop up at various British theatres across 1953 and was even screening as a second feature at children’s matinees into 1954 and 55. In 1958, the film had a special Christmas TV broadcast in Australia where much was made of the fact that it featured Julie Andrews who was riding high at the time on the success of My Fair Lady (’Voice’: 15).

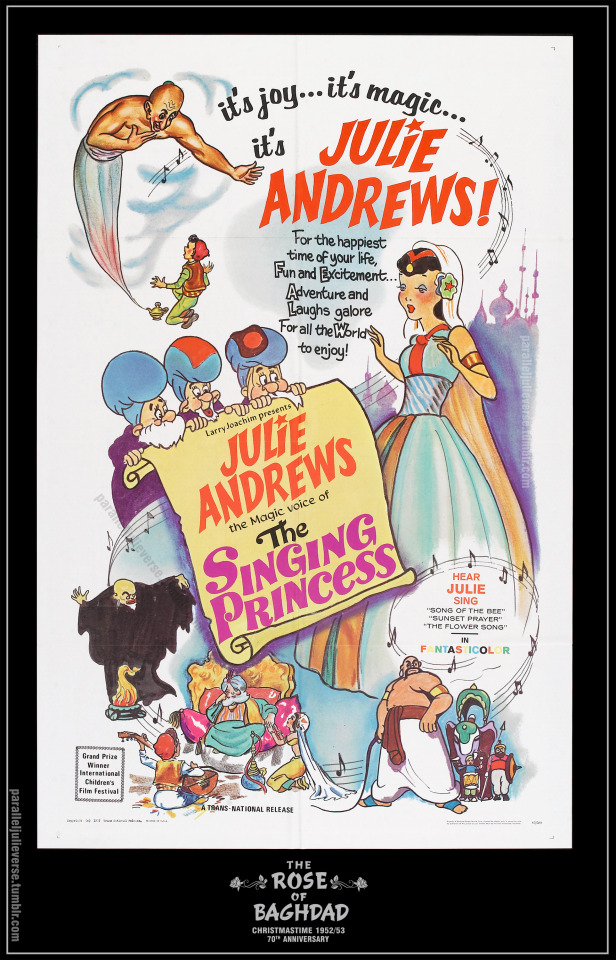

Ironically, the film would receive its most high profile release many years later in 1967 when a minor US film distributor, Trans-National Film Corp, secured North American exhibition rights for the property. Trans-National was one of a series of companies set up by Laurence “Larry” Joachim who would find modest success in later years as a distributor of martial arts films. With a background in TV gameshows, Joachim was known for his aggressive marketing strategies and he was very “hands on for the theatrical campaigns and art work for all the movies with which he was involved” (’Larry Joachim’ 2014).

In an effort to capitalise on Julie’s sudden film superstardom in the mid-60s, Joachim tried to sell The Rose of Baghdad as a ‘new’ Julie Andrews musical. He gave it a new title as The Singing Princess and marketed it with the dubious tagline: “It’s joy, it’s magic, it’s Julie Andrews”. He even billed the film as made in ‘Fantasticolor’, an entirely fictitious process.

Registered with the Library of Congress in April 1967, The Singing Princess wasn’t released to the public till November of that year, likely to coincide with the holidays (Library of Congress: 121). It opened with a series of ‘children’s matinees’ at over 60 venues in New York before rolling out to other theatres across the US (’Children’s show’: 105).

It’s not clear if Joachim had access to the original UK source elements or if he just used a standard release print, but release copies of The Singing Princess were decidedly sub-par. They were marred by artefacts, colours were muddied and the soundtrack was prone to distortion. Moreover, by 1967, the film was hugely dated with old-fashioned production values and glaringly anachronistic elements. Joachim even had to edit a few sensitive scenes which were either too graphic or impolitic for the times.

The Singing Princess was not well received. Indicative of the dim response is this New York Times review summarily titled, ‘Feeble Princess’:

“The Singing Princess has joined the parade of foreign-made movies that turn up on weekend movies, most of them only fair and some of them incredibly awful...Parents would do well to read the smaller print in the ads...for the picture stars ‘the magic voice of Julie Andrews’ and emphatically not the lady’s magical presence....As an hour-length, fairy-tale cartoon of Old Baghdad the film is feeble entertainment compared with the technical wizardry and dazzling palettes of Walt Disney and others. It is possibly best suited for very small toddlers who may never have watched a cartoon on a theater-size screen. The distributor said that the film was made years ago in Italy and later dubbed into English in London, where apparently a very youthful Miss Andrews was recruited to sing three very so-so tunes. Those pristine, silvery tones certainly sounded like her on Saturday, but in the diction department she could have learned a thing or two from the Andrews Sisters. As a matter of fact, while London was revamping Old Baghdad, Italian-style, it might have been a good idea to set it swinging” (Thompson: 63).

The hatchet-job US release of The Singing Princess is the English-language version that has largely circulated since. In the intervening years, it has been given several TV, video and DVD releases of varying degrees of technical quality. None of which have helped the film’s reputation.

Not surprisingly, the film has enjoyed rather more favourable treatment in Italy. To mark the 60th anniversary of the original Italian release in 2009, La rosa di Bagdad was carefully restored and reissued on Blu-Ray. There have been some recent attempts to couple these restored visuals with the existing Singing Princess soundtrack, but it would be nice to see a properly remastered English-language version, ideally from the original audio elements if they still exist.

Heirloom Rose

Although it was never a major entry in the Julie Andrews canon, The Rose of Baghdad is not without critical significance. Not only was it Julie’s first foray into film-making, but it was also an early instance of the animation voice-work that would become a major part of her latter day professional output with recent efforts such as the Shrek and Despicable Me series.

In addition, Princess Zeila signals an early entry in the long line of royal characters that would come to inform the evolving Julie Andrews star image. By 1952, Julie was already a dab hand at playing princesses, having donned crowns several times both on stage and in song. She would proceed to ever more celebrated royal character parts from Cinderella and Guinevere in Camelot to Queen Clarisse in The Princess Dairies and Queen Lillian in the aforementioned Shrek films.

Ultimately, though, the principal historical significance of The Rose of Baghdad lies in its status as one of the few recorded examples we have from Julie’s early juvenile career in Britain. She worked assiduously in these early years, giving hundreds, if not thousands, of performances on stage, radio, and television. Sadly, other than a few 78 recordings and the odd surviving radio programme, very little of that early work remains. One lives in hope that more material may surface in coming years. In the meantime, The Rose of Baghdad offers a tantalising glimpse back into this fascinating early period when Julie was ‘Britain’s youngest singing star’.

References:

Allsop, Kathleen (1953). ‘Photoplay’s guide to the films: Rose of Baghdad.’ Photoplay. 4(1) January: p. 43.

Andrews, Julie (2008). Home: A memoir of my early years. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Bellano, Marco (2016). ‘“I fratelli Dinamite” e “La rosa di Bagdad”, l'Italia e la musica’. In: Scrittore, R. (Ed.). Passioni animate. Quaderno di studi sul cinema d'animazione italiano, Milan : 19-52.

Bendazzi, Giannalberto (2020). A moving subject. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

‘Children’s show’ (1967). Daily News. 8 November: p. 105.

Collier, Lionel. (1953). ‘Talking of films: “The Rose of Baghdad”.’ Picturegoer. 25(929): pp. 17-18.

Davalle, Peter C. (1952). ‘Film notes: Italy treads Disney trail.’ Western Mail and South Wales News. 20 September: p. 4.

‘Entertainment: Film Of Botany Bay. (1952). The Times, 29 December p. 9.

Fiecconi, Federico (2018). ‘L’arte preziosa della Rosa / The Precious art of the Rose’. In Gradelle, D. (Ed.). La rosa di Bagdad: Un tesoro ritrovato. Parma: Urania Casa d’Aste: pp. 6-11.

‘Grand National offers ten British.’ (1952). Kinematograph Weekly. 1 May: p. 16.

‘Larry Joachim, distributor of kung du films, dies at 88.’ (2014). Variety. 2 January.

‘Late review: The Rose of Baghdad.’ (1952). Kinematograph Weekly. 18 December: p. 7.

Lejeune, C.A. (1952). ‘At the films: Dan’s Anderson.’ The Observer. 21 December: p. 6.

Library of Congress (1967). Catalog of copyright entries: Works of art. 21(7-11A), January-June.

‘London and provincial trade screenings.’ Kinematograph Weekly. 11 September: p. 32-34.

‘Many countries covered in big Grand National List’ (1951). Kinematograph Weekly. 1 February: p. 20.

Massey, Howard (2015). The great British recording studios. London: Hal Leonard Publishing.

McFarlane, Brian, & Slide, Anthony. (2013). The encyclopedia of British film. 4th Edn. Manchester University Press.

‘Next week’s cinema shows.’ (1952). The Walsall Observer. 12 December: p. 10.

‘New Releases: Rose of Baghdad’ (1952). Picture Show and Film Pictorial. 59(1361). 20 December: p.10.

Our Film Critic (1952). ‘Seasonable fantasy.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph. 23 December, p. 4.

‘Pre-releases and release dates.’ (1952). Kinematograph Weekly. 18 December: p. 119.

‘Rose of Baghdad.’ (1952).

T.C.K. (1952). ‘Cinema shows in Birmingham: Italian cartoon.’ The Birmingham Post. 17 December: p. 4.

Thompson, Howard (1967). ‘Screen: Feeble princess.’ The New York Times. 13 November: p. 63.

‘Trade show news: colour cartoon feature.’ (1952). Kinematograph Weekly. 11 September: p. 14.

Ugolotti, Carlo (2018). ‘La rosa di Bagdad: il folle sogno di Anton Gino Domeneghini / The Rose of Bagdad: the mad dream of Anton Gino Domeneghini.’ In Gradelle, D. (Ed.). La rosa di Bagdad: Un tesoro ritrovato. Parma: Urania Casa d’Aste: pp. 12-21.

‘Voice of Julie Andrews.’ (1958). The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 December: p. 15.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2023

#julie andrews#the rose of baghdad#la rosa di bagdad#anton gino domeneghini#the singing princess#princess zeila#italian cinema#british film#1952#film history#classic film

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alexandre Benois (1870 - 1960) Sergei Ernst and Nicolas Benois, Zinkino, 1917 (28 x 44.5 cm)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stage costumes by Nicola Benois for Maria Callas

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giselle with Svetlana Zakharova e David Hallberg @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Giselle is one of La Scala Ballet’s international calling cards. Together with Nureyev’s Don Quixote, this production has been seen all over the world, and rightly so. The company dances it beautifully, and its staging by Yvette Chauviré (based, of course, on the Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot choreography) would be difficult to better. It is clearly told, the story points being so carefully prepared that focus is always on the right spot at the right time.

The sets and costumes are traditional – using Aleksander Benois’s designs created for the Paris Opera Ballet, with Olga Spessivtseva as Giselle, in 1924 – and tone perfect, with a rich palette of harvest time hues at the opening, and the darkest, most threatening of forests in the second act. His old-fashioned gauzes and painted backcloths work their magic and produce a gasp from the audience on every opening of the curtain. The laying out of the set is superlative with a hidden ramp for the court, including Albrecht, to descend from its lofty castle to join the villagers; the entrance to the cottage that Albrect uses to hide his cloak and sword to ‘disguise’ himself as a peasant is towards the centre of the stage so the entire audience can see the essential moments of concealing and discovering his princely regalia; and a distant church is seen during the second act which is illuminated by the warm light of dawn as its bells chime 4 o’clock.

The costumes are sumptuous, so the villagers’ past harvests were clearly astonishingly abundant. Giselle’s first act costume has a generous, plump skirt, as is seen in Benois’s designs. Bathilde, though, is something of a confusion as her costume is so heavy and ornate that she appears to be the Duke’s wife, therefore Albrecht’s mother, not his betrothed. In addition, having her and the Duke entering hand in hand adds to this feeling whereas I remember, in earlier editions, that the Duke entered first and then presented Bathilde as she came on separately, which makes far more sense.

Giselle with Svetlana Zakharova e David Hallberg @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

The opening cast saw Svetlana Zakharova and David Hallberg in the main roles, bringing them back together after five years. They danced Swan Lake at La Scala in 2014, shortly before Hallberg suffered his devastating injuring (forcing him to cancel his performances at the theatre in Alexei Ratmansky’s The Sleeping Beauty with Zakharova, the following year). How wonderful to report that Hallberg is back in sublime form. He is innately elegant, and his lines are drawn to fit perfectly with those of Zakharova. Though always clear in his mime, he is a subtle actor, and the gentleness as he touches Giselle’s arms from behind as he joins her for their second act pas de deux is typical of his care to give each gesture a meaning. His plié is deep and soft, and the use of his legs and feet are the utmost in expressivity. Zakharova danced beautifully, as the Milanese audience has come to expect, and even though this isn’t her ideal role, she gave a pleasing performance. Her outstanding finesse is in every movement, though she will insist on taking her leg up unnecessarily high on occasions causing her tutu to start slipping down her leg – not a good look. She overdid her makeup a little (though at the back of the house this probably wasn’t seen) which gave her expression a harder edge than is ideal for the young peasant girl.

Giselle with Martina Arduino and Nicola del Freo @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

The peasant pas de deux with Martina Arduino and Nicola Del Freo was magnificent. Arduino would be better suited to playing Giselle or Myrtha, though she danced the steps ably even if she isn’t a natural for the role. Del Freo, however, was thrillingly perfect. His leg and footwork was extraordinary with steely precision and virile cockiness in each step. Maria Celeste Losa played Myrtha at almost every performance. Whether this is because no one else in the company can approach her level is doubtful, but she excelled in the jumps, gave humanity to her austerity, and her pas de bourrée crisscrossing of the stage was mesmerising. Her two main Wilis were Alessandra Vassallo and Emanuela Montanari, two of the company’s most personable dancers yet they gave suitably glacial interpretations with technically assured solos.

Mick Zeni was Hilarion, exuding suspicion, jealousy and finally hatred, and was pitiful in the second act. Equally suited to the role was Marco Agostino who also possesses some fine acting talent as well as great aplomb in his dancing. Christian Fagetti too never fails to deliver, and La Scala now boasts an impressive roster of male talent, which wasn’t so evident a decade or so ago.

Giselle with David Hallberg Mick Zeni @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Giselle with Maria Celeste Losa @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Giselle’s mother was played by Beatrice Carbone who is just a couple of years older than Zakharova, but she convincingly inhabited the part from the inside instead of wearing it like a costume. In an alternative cast, however, Daniela Siegrist looked more like a Julie Walters’ character as she bustled about, wringing her hands. Judging these parts can be trickier than tackling the main roles.

Federico Fresi and Antonella Albano were also splendid in the peasants’ pas de deux. Fresi comes with built-in springs in his legs, but it’s a pity that his perpetually anxious look makes him look as though he’s going into battle.

The other Giselle and Albrecht couples during the run were Nicoletta Manni and Timofej Andrijashenko, and Vittoria Valerio and Claudio Coviello. All four gave satisfying readings. The fact that Valerio dances the role well is a given, and La Scala has entrusted it to her many times even though she’s still a soloist with the company. She was paired with Coviello who performed, quite thrillingly, 34 entrechats six in front of Myrtha, and although he was beaten by Andrijashenko on number (36, as Roberto Bolle used to do), they were beautifully executed and on the spot. Hallberg opted for the diagonal series of brises.

Andrijashenko is an extremely good Albrecht and is very much of the upper classes – taking off his cloak and sword probably only fools Giselle. He was sunny and cunning in the first act, though facially he became somewhat invisible in the second act. His Giselle was Manni who was pitch-perfect from the moment she left the cottage – wide-eyed innocence never becoming cutesy, and she made each step appear simple and natural. As a Wili, she was cool but feeling, imploring with her eyes, and loving with the tilt of her head.

It was evident why this ballet remains the pièce de résistance of La Scala’s repertoire.

Giselle with Svetlana Zakharova @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Giselle with David Hallberg @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Review: Giselle at La Scala with Zakharova/Hallberg, Manni/Andrijashenko, Valerio/Coviello Giselle is one of La Scala Ballet’s international calling cards. Together with Nureyev’s Don Quixote, this production has been seen all over the world, and rightly so.

#Alessandra Vassallo#Alexei Ratmansky#Antonella Albano#Christian Fagetti#Claudio Coviello#David Hallberg#Giselle#La Scala#Marco Agostino#Maria Celeste Losa#Martina Arduino#Mick Zeni#Nicola Del Freo#Nicoletta Manni#Roberto Bolle#Svetlana Zakharova#Timofej Andrijashenko#Vittoria Valerio#Yvette Chauviré

1 note

·

View note

Note

Are there any modern and/or contemporary artists that you like? :)

Modern (too vast to be fair, yet the Symbolists and Expressionists will always hold a special place): Mikhail Nesterov, Franz Stuck, Zinaida Serebriakova, Stanislav Zhukovsky, Egon Schiele, Yoshijiro Urushibara, Edgar Degas, Alfred Roller, Natalia Goncharova, Gustav Klimt, Käthe Kollwitz, Alexandre Benois, Emil Nolde, Henri Le Sidaner, Vincent van Gogh, Romaine Brooks, Chiura Obata, Nicholas Roerich, Xavier Mellery, Edvard Munch, Koloman Moser, Marie Laurencin, Tsuguharo Foujita, Mikhail Vrubel, Leonor Fini, Meredith Frampton, Henri Matisse, Joan Miró, Gabriele Münter, Alexei Savrasov, Konstantin Korovin, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Félix Vallotton, František Kupka, Vilhelm Hammershøi, Marianne von Werefkin, Maximilien Luce, Henri Rousseau, Leonora Carrington, Horace Pippin, Wassily Kandinsky, Léon Spilliaert, Maurice Denis, Odilon Redon, James Ensor, Viktor Vasnetsov, Jan Toorop, Paul Signac, Arnold Böcklin, Kazimir Malevich, Remedios Varo, Leo Piron, Magnus Enckell…Contemporary: Manuel Cargaleiro, Eva Hesse, Andrew Wyeth, Oswaldo Guayasamin, Helena Almeida, Luís Noronha da Costa, Kaoru Mansour, Ikko Fukuyama, Mario Segundo Pérez, Yu-ichi Inoue, Diego Evangelista, Noureddine Daifallah, Chen Yifei, Alexander Calder, Pan Yun, Tilsa Tsuchiya, Samiro Yunoki, Andrei Mylnikov, Tomikichiro Tokuriki, Golnaz Fathi, Xie Jinglan, Farideh Lashai, Mark Rothko, Qin Feng, Agnes Martin, Wolf Kahn, Jesper Christiansen, Zahoor ul Akhlaq, Francis Bacon, Nicola Nemec, Kyosuke Tchinai, Nabil Anani, Tomás Sánchez, David Hockney, Kara Walker, Daniel Senise, Chiu Ya-tsai, Michael Kenna, Gennady Spirin, Chaouki Chamoun, Wilfredo Lam, Crystal Liu, Ricardo Angélico, Tayseer Barakat…

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 21

On May 21, 1944, Marianna Kalogeropoulou (age 20) sang “Casta Diva” in public for the first time, at a benefit concert at the Olympia Theatre in Athens.

On May 21, 1956, Callas sang the first of six performances of Giordano’s “Fedora” at La Scala. Originally scheduled for this period was “Parsifal” under Erich Kleiber, with Callas as Kundry (singing in German?) Kleiber died in January so La Scala made this substitution “as odd a change in repertory as any opera house has devised” remarked Walter Legge. These were her only performances of this opera and no recording exists.

Claudio Sartori in Opera Magazine: “settings [are] by Benois in which he seems to amuse himself in the bad taste of the period. Maria Meneghini Callas and Franco Corelli lead the cast, singing and acting with dramatic power, perhaps overstepping the limits of good style – if indeed good style be desirable in this melodramatic piece.”

On May 21, 1959, Callas sang her concert of arias at the Kongress-Saal in Munich, Nicola Rescigno conducting the orchestra of the Bavarian State Opera.

0 notes

Photo

The Marseilles Family

Source: https://web.archive.org/web/20050204132146/http://tarothermit.com/marseilles.htm

The Marseilles family of tarot designs is certainly both the most enduring and most influential of all the tarot variants. These are the cards that came to the attention of the French occultists and launched the widespread use of tarot cards for divination and other esoteric purposes.

These designs carry the name of Marseilles because that city was a principal card manufacturing center in the 17th and 18th centuries. The actual place of origin of the designs is unknown. When France conquered Milan in 1499, French and Swiss soldiers probably encountered Milanese tarot cards similar to those seen on the fragmentary sheet housed in the Cary collection of playing cards. This is probably how the game of tarot, and with it the Milanese card designs, spread to Switzerland and eastern France. At some point in the 16th century, the set of designs known as the Tarot de Marseille became the standard pattern for players in these French-speaking regions.

Learn more and view a comparative chart of styles: Cary sheet (uncut sheet fragment, Milan c.1500), Tarot de Marseille (Nicolas Conver, 1760, Marseilles), Lombardy Tarot (Giacomo Zoni, 1780, Bologna), Tarot de Besançon (J. B. Benois, 1818, Strasbourg)

See: https://web.archive.org/web/20050204132146/http://tarothermit.com/marseilles.htm

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TEATRO ALLA SCALA 7/12/2021: MACBETH (NETREBKO-SALSI-MELI-ABDRAZAKOV;LIVERMORE-CHAILLY)

Luca Salsi I Anna Netrebko, Macberth i Lady Macbeth al Teatro alla Scala, producció de Davide Livermore. Fotografia de Marco Brescia & Rudy Amisano, gentilesa del Teatro alla Scala El 7 de desembre de 1952 el Teatro alla Scala de Milà inaugurava la temporada amb el Macbeth de Verdi dirigit per Victor de Sabata i Nicola Benois, el veterà Enzio Mascherini va ser el protagonista i la Lady va anar a…

View On WordPress

#Andrea Pellegrini#Anna Netrebko#Bianca Casertano#Chiara Isotton#Constantino Finucci#Coro ed orchestra del Teatro alla Scala di Milano#Davide Livermore#Francesco Meli#Giuseppe Verdi#Guillermo Bussolini#Ildar Abdrazakov#Leonardo Galeazzi#Luca Salsi#Macbeth#Rebecca Luoni#Riccardo Chailly

0 notes

Photo

Lo spazio, il luogo, l’ambito

Scenografie del Teatro alla Scala 1947-1983

Sull’opera lirica di Federico Fellini, Saggi di Evelina Schatz, Giampiero Tintori, Giorgio Cristini, Giorgio Vitali, Giorgio Siribaldi Luso, Gillo Dorfles. Pensieri di scenografia a cura di Evelina Schatz, Gaetano Negri, Pompeo Cambiasi, Aleksandr Benois, Nicola Benois, Födor Saljapin, Beni Montresor, David Borovskij, Margarita Wallmann, Jurij Ljubimov, Carlamaria Casanova, Renata Tebaldi. Fotografie di Lelli & Masotti e Raimondo Santucci.

Silvana Editoriale per Banco Lariano, Milano 1983, 159 pagine, Ril. tela ed. con sovracc., 30,5 x 25 cm,

euro 25,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Il libro espone i mezzi e i modi del lavoro nei laboratori di scenografia e sul palcoscenico della Scala, permettendo al lettore di conoscere dove e come il messaggio creativo contenuto nel bozzetto si fa cosa scenica per vivere nell'azione teatrale.

20/12/21

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter: @fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano tumblr: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano

#Teatro alla Scala#scenografie#spazio luogo ambito#Federico Fellini#Gillo Dorfles#Evelina Schatz#Lelli & Masotti#1947/1983#fashionbooksmilano

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

(4/8) Dialogue de la Duchesse de Bourgogne

Artist’s Name: Nicolas Finet

Date: 1468

Current Location: The British Library

Physical Description: The single illustration in Dialogue de la Duchesse de Bourgogne depicts Margaret of Burgundy on her knees before Christ in her bedroom. It is worth noting that this bedroom is the same bedroom as the one depicted in this book’s pair, Benois seront les Miséricordieux. The boarder is decorated with colorful foliage and depictions of birds. Other imagery specific to Margaret is also included, with the initials ‘C’ and ‘M’ representing Margaret and her husband Charles on the pot in the lower boarder along with her personal devise, “may good come of it” on the rim of the pot. Additionally, there is an angel holding Margaret’s coat of arms as Duchess of Burgundy in the side margin.

General Analysis: As personal as the image is, the book itself is more so. As a companion novel to Benois seront les Miséricordieux, Dialogue addresses the intimate interaction between Christ and his disciple, in this case Margaret of Burgundy. It is formatted in a dialogue between the two, with Margaret asking Christ questions and receiving direction to live as other holy women have. A year before her death, Margaret dedicated Dialogue to Jeanne de Hallewin, Lady of Wassenaer, her lady-in-waiting and friend as is recorded in the back of the book.

Of the eight books she commissioned in her lifetime, Dialogue is the only one that was an entirely new work. It demonstrates Margaret’s personal devotion to Catholicism, as much of her personal library did, albeit not in such an intimate way. As such, this work is important in understanding Margaret’s aspirations and values, as it was commissioned as Margaret’s personal book of Hours.

Sources: image and information (British Library), information used in analysis (University of Surrey, Women’s Literary Culture and the Medieval Canon: The Duchess’s Dialogue: Writing and Reading Margaret of York’s Le Dyalogue de la Duchesse)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Inspiration - Ideas & Trends For Free Consulation : [email protected] +966548005766 True to his neo-gothic style with a delicate iron spiral staircase, the russian architect Nicholas Benois designed the Imperial Stables in Peterhof, Russia for Emperor Nicolas I. ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ 📸 @onlyninnadin ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ #spiral #spiralstaircase #stairs #stairwaytoheaven #stairdesign #neogothic #gothicstyle #robinseggblue #peterhof #imperial #interiorarchitecture #interiorart #interiorarchitects #interioraddict #elegantstyle #interiorphotography #vogueliving #archdaily #architecturedesign #designinspiration #luxuryworld #designlove #bespokefurniture #creativedesign #decorlovers #homedesign #interiorstyling #interiorlovers #interiorstyle #bykoket — view on Instagram https://ift.tt/2ZOdRPJ

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Part 2. Rossini's Semiramide (1823), based on Voltaire's tragedy Sémiramis (1746), it was the last opera molded on baroque tradition. The drama takes place in Babylon, Joan portrays the Queen of Babylon, who murders the king poisoned - Ninos. She refused to marry Assur, Prince of Syria, for being in love by the young Arsace, that in the fact is her son - presumed dead - with Ninos. Assur makes vows to kill his rival, Arsace. In the last scene, Semiramide is mortally wounded trying to stop the fight between Assur and her son. Arsace is acclaimed the new king. · *Scenography and costumes designed by the stage designer Nicola Benois. **Source: teatroallascala.org · #Stage #Scenography #SetDesign #Design #Costume #LaScala #Milan #ClassicalMusic #Music #Opera #Baroque #BelCanto #Composer #GioacchinoRossini #Rossini #Semiramide #Semiramis #Dramatic #Coloratura #Soprano #Dame #JoanSutherland #LaStupenda #Diva #PrimaDonna #Assoluta #Legend #1960s https://www.instagram.com/p/B0gHSbthySF/?igshid=vm51eytfc9pb

#stage#scenography#setdesign#design#costume#lascala#milan#classicalmusic#music#opera#baroque#belcanto#composer#gioacchinorossini#rossini#semiramide#semiramis#dramatic#coloratura#soprano#dame#joansutherland#lastupenda#diva#primadonna#assoluta#legend#1960s

0 notes

Photo

Alexandre Nikolayevich Benois (May 3, 1870 – Feb 9, 1960), was an influential artist, art critic, historian, preservationist, and founding member of Mir iskusstva, an art movement and magazine. As a designer for the Ballets Russes under Sergei Diaghilev, Benois exerted what is considered a seminal influence on the modern ballet and stage design.

var quads_screen_width = document.body.clientWidth; if ( quads_screen_width >= 1140 ) { /* desktop monitors */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width >= 1024 && quads_screen_width < 1140 ) { /* tablet landscape */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width >= 768 && quads_screen_width < 1024 ) { /* tablet portrait */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width < 768 ) { /* phone */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }

Alexandre was born into the artistic and intellectual Benois family, prominent members of the 19th- and early 20th-century Russian intelligentsia. His mother Camilla (ru: Камилла Альбертовна Кавос, and then Бенуа) was the granddaughter of Catterino Cavos. His father was Nicholas Benois, a noted Russian architect. His brothers included Albert, a painter, and Leon, also a notable architect. His sister, Maria, married the composer and conductor Nikolai Tcherepnin (with whom Alexandre would work). Not planning a career in the arts, Alexandre graduated from the Faculty of Law, Saint Petersburg Imperial University, in 1894.

Three years later while in Versailles, Benois painted a series of watercolors depicting Last Promenades of Louis XIV. When exhibited by Pavel Tretyakov in 1897, they brought him to attention of Sergei Diaghilev and the artist Léon Bakst. Together the three men founded the art magazine and movement Mir iskusstva (World of Art), which promoted the Aesthetic Movement and Art Nouveau in Russia.

During the first decade of the new century, Benois continued to edit Mir iskusstva, but also pursued his scholarly and artistic interests. He wrote and published several monographs on 19th-century Russian art and Tsarskoye Selo. In 1903, Benois printed his illustrations to Pushkin’s poem The Bronze Horseman, a work since recognized as one of the landmarks in the genre. In 1904, he published his “Alphabet in Pictures,” at once a children’s primer an elaborate art book, copies of which fetch as much as $10,000US at auction.[4] Illustrations from this volume were featured at a video presentation during the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics in Sochi in 2014.

In 1901, Benois was appointed scenic director of the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, the performance space for the Imperial Russian Ballet. He moved to Paris in 1905 and thereafter devoted most of his time to stage design and decor.

During these years, his work with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes was groundbreaking. His sets and costumes for the productions of Les Sylphides (1909), Giselle (1910), and Petrushka (1911), are counted among his greatest triumphs. Although Benois worked primarily with the Ballets Russes, he also collaborated with the Moscow Art Theatre and other notable theatres of Europe.

Surviving the upheaval of the Russian Revolution of 1917, Benois achieved recognition for his scholarship; he was selected as curator of the gallery of Old Masters in the Hermitage Museum at Leningrad, where he served from 1918 to 1926. During this time he secured his brother’s heirloom Leonardo da Vinci painting of the Madonna for the museum. It became known as the Madonna Benois. Benois published his Memoirs in two volumes in 1955. In 1927 he left Russia and settled in Paris. He worked primarily as a set designer after settling in France.

Benois’s son, Nicola Alexandrovich Benois (also known as Nikolai Benois), was born in 1901, and went on to become a celebrated opera designer, creating costumes and sets for opera companies all over the world. Benois’s nephew, Nikolai Albertovich Benois, married the opera singer Maria Nikolaevna Kuznetsova.

Benois was also the uncle of Eugene Lanceray and Zinaida Serebriakova, who became recognized Russian artists, and one of the great-uncles of the British actor Sir Peter Ustinov.

Alexandre Benois was originally published on HiSoUR Art Collection

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

HERMITAGE. ARTE, HISTORIA Y ARQUITECTURA

Texto: Oliver Web · Fotos: The State Hermitage Museum St. Petersburg.

A orillas del río Neva se encuentra este espectacular edificio que alberga la mayor colección de arte de Rusia. Durante años, los antiguos zares fueron recopilando los trabajos de artistas hasta que en 1917 se declaró el enclave como museo estatal, abierto por y para el pueblo. La historia del museo es tan convulsa como la de la propia Rusia. Cuando Catalina La Grande llega al poder tras un golpe de Estado en 1762, decidió establecer su residencia oficial en el Palacio de Invierno de la ciudad de San Petersburgo. Sería en 1764 cuando compraría el primer lote de pinturas que decorarían su palacio, una serie de óleos flamencos y holandeses que adquirió en Berlín. Nada menos que 225.

El museo ha crecido y se ha expandido por el mundo. El complejo Guggenheim Hermitage de Las Vegas, el edificio de Ámsterdam, las salas del Hermitage en Sommerset House, en Londres, o una posible ampliación en la ciudad de Barcelona, en donde muchos turistas rusos han asentado sus casas de veraneo, son algunos ejemplos. En 2014 está prevista la apertura de la ampliación que albergará colecciones de arte moderno y contemporáneo. Una excelente manera de festejar los 250 años de historia del complejo.

Entre los museos de bellas artes hay pocos cuyas colecciones puedan competir en valor, riqueza y diversidad con las del Hermitage. Es uno de los museos más famosos del mundo, que contiene unos tres millones de obras del arte, entre las cuales hay cuadros, esculturas, dibujos, grabados, monedas y medallas y muchas obras del arte aplicado. El Hermitage es un conjunto museístico que ocupa cuatro enormes palacios, acaba de recibir a su disposición el quinto edificio majestuoso, la que fue sede del Ministerio militar de los zares, el edificio del Estado Mayor, y sin embargo sólo 25% de sus colecciones han encontrado espacio para estar expuestos al público, guardando los demás 75% en sus fondos y consignas especiales.

Se dice que si una persona dedicara sólo un minuto a contemplar cada pieza expuesta del museo y pasara en el Hermitage, siguiendo el horario del museo, siete horas diarias seis días a la semana sin ninguna parada ni para comer, necesitaría más de cinco años para verlas todas.

El Hermitage es un museo único porque, además de las colecciones del arte expuestas en las salas de tres palacios que ocupa la pinacoteca como tal (el Hermitage Pequeño, el Hermitage Viejo y el Nuevo Hermitage), los visitantes gozan de magníficos interiores palaciegos, entre los cuales destacan las salas de gala del Palacio de Invierno, la residencia principal de los emperadores rusos en los años 1762-1917.

El Palacio de Invierno es una obra maestra del estilo barroco, creada por el arquitecto italiano Francisco Bartolomé Rastreli. En la decoración de las fachadas e interiores Rastreli dio rienda suelta a su fantasía. Él mismo dijo de su creación que el Palacio de Invierno fue construido “... para la gloria de Rusia sólo” y se hizo el símbolo del poder y importancia de Rusia que se transformó en uno de los países más significados del mundo en el siglo XVIII.

El Palacio que pasó a formar parte del museo en el año 1922, fue durante dos siglos la residencia principal de los zares. Había sido construido para la emperatriz Isabel, hija de Pedro el Grande. A pesar de convertirse en las salas de exposiciones, estas no han perdido nada de su esplendor. Una de las más bellas es la sala de Malaquita; sus columnas, pilastras, chimeneas, lámparas de pie y mesitas están decoradas con malaquita de los montes Urales. El verde vivo de la malaquita, combinado con el brillo del dorado y el mobiliario tapizado con seda de color frambuesa, determinan la impresión fantástica de esta sala.

El palacio llamado el Hermitage Viejo fue construido junto al Pequeño en la década de 1770 para instalar la creciente colección artística de Catalina II y sus interiores no los desmerecen en nada a los de otros palacios. Ahora en este palacio se encuentran obras de los maestros de renacimiento italiano: Giorgione, Simone Martín, obras de Fra Angélico y Boticelli... Pero las cimas de la colección italiana son dos cuadros de Leonardo da Vinci: la Madona Benois correspondiente a su periodo creativo temprano y la obra del museo número uno, y la Madona Litta, que es por el contrario un trabajo de madurez, representando en la imagen de la Virgen, el ideal de la belleza física y espiritual. Entre las obras de la célebre colección de Tiziano destaca San Sebastián.

El Hermitage Pequeño fue construido para la vida privada de Catalina II. La emperatriz quería descansar de la vida oficial en un lugar aislado, acogedor y lleno de obras artísticas. Por ese motivo el palacio fue denominado “Hermitage”, palabra francesa que significa “ermita”, llenado de las colecciones de pintura y escultura, donde la “ermitaña” soberana solía pasar sus horas de ocio, admitidos solamente los amigos más íntimos a hacerle compañía.

En cuanto a los interiores del Hermitage Pequeño vale la pena mencionar la Sala de Pabellones. Es un maravilloso salón adornado con galerías, rejas doradas, mosaicos esmaltados, tal llamadas “fuentes de las lágrimas”, centelleantes lámparas de araña de cristal de roca. En la sala se expone también el Reloj Pavo Real, una de las perlas de la colección del museo, obra inglesa del siglo XVIII. Cuando el reloj da las horas, el pavo real instalado en un roble, abre su opulenta cola y da la vuelta mostrándola. Las ventanas de esta sala miran al jardín colgante, ubicado sobre las bóvedas de la planta baja.

El edificio del Hermitage Nuevo es el único palacio del conjunto que no fue construido con Catalina II en el trono, sino con su nieto, Nicolas I, y resultó ser el primer museo que, aunque fuera con muchas limitaciones, abrió sus puertas al público, hace 150 años. Aquí están expuestas las obras de Rafael Santi - el orgullo de todo el museo, y se guarda allí “la Biblia de Rafael” –así fue nombrada la copia de la galería del palacio papal en el Vaticano, construida por el arquitecto Bramante y pintada por Rafael y sus discípulos. Aquí mismo se puede ver la única obra de Miguel Ángel, El niño en Cuclillas, que estaba destinada al panteón de los Medici.

En las salas solemnes y majestuosas, decoradas con vasos, mesas y lámparas decorativas de malaquita, ágata y lapislázuli, se hallan las exposiciones de pintura italiana y toda la colección de pintura española, considerada como una de las mejores fuera de las fronteras de España y adquirida por los zares rusos en Francia (colección de Jose na, esposa de Napoleón) y España (colección de Manuel Godoy) después de las guerras napoleónicas. En ella se puede ver obras de El Greco, Velázquez, Ribera, Zurbarán, Murillo y Goya.

Además de las pinturas españolas, los visitantes verán cuadros de maestros de los Países Bajos, donde se destaca una colección riquísima de Rembrandt. Los lienzos de Rembrandt ocupan una gran sala y dan una clara idea de toda su obra creativa: el retrato juvenil de su esposa Saskia, representada como la diosa Flora, el trágico Descendimiento de la cruz, el penetrante retrato del Anciano en rojo... y al final la joya de la colección, el Regreso del hijo pródigo, escena evangélica en que el maestro pudo expresar su fe en el bien y en el amor humano.

Cinco salas del Hermitage Nuevo atesoran obras de Rubens, desde las más tempranas hasta las últimas, célebres retratos de Van Dyck, escenas de caza de Paul de Vos y abundantes naturalezas muertas de Frans Snyders.

#Hermitage#Arte#Historia#arquitectura#Rusia#amantemagazine#amantelifestyle#amante#fineliving#culturecorner#cultura#culture corner

0 notes