#National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

October 11, 2023.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beau-Ty. Marcus Brutus. American. 2022.

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

#marcus brutus#National Museum of African American History and Culture#the Smithsonian#african american history#American history#american art#America#black history#painting#art#culture#history#modern history#contemporary art#contemporary history

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johans Valters (Latvian 1869–1932), Zemnieku meitene (Peasant Girl), 1904. Oil on canvas. (Source: Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga.)

#art#artwork#Latvian art#Latvian artwork#symbolism#modern art#contemporary art#20th century modern art#20th century contemporary art#early 20th century art#modern Latvian art#contemporary Latvian art#Johans Valters#Zemnieku meitene#peasant girl#Latvian National Museum of Art

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

Youre so vain! I bet you think this reflection is about you, Don't you? da Kirstie Shanley Tramite Flickr: **All photos are copyrighted**

#National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art#Rome#Roma#Italia#Italy#art#modern art#sculpture#Contemporary art#museum#gallery#art gallery#Art museum#reflection#blue#space#interior#architecture#mood#Europe#travel#people#People Experiencing Art#flickr

0 notes

Text

Home Within Home, installation by Korean artist Do Ho Suh, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, Korea, 2013–2014.

#art#photography#contemporary art#sculptures#painting#curators#south korea#art installation#interiors#seoul#curators on tumblr

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

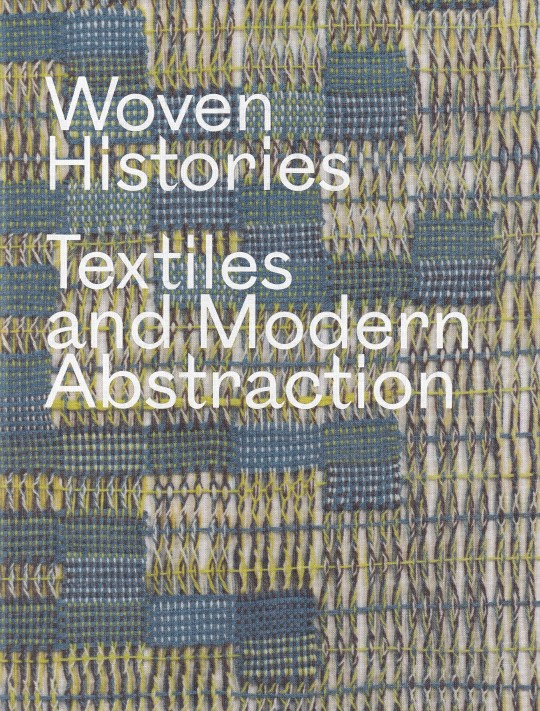

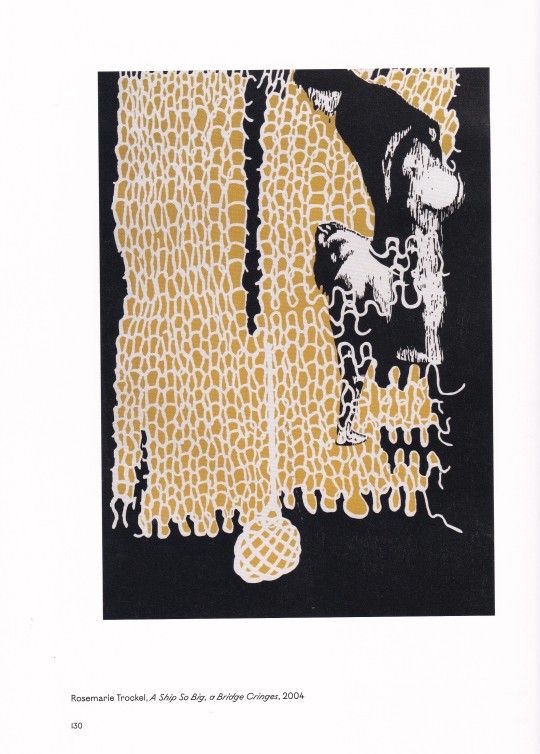

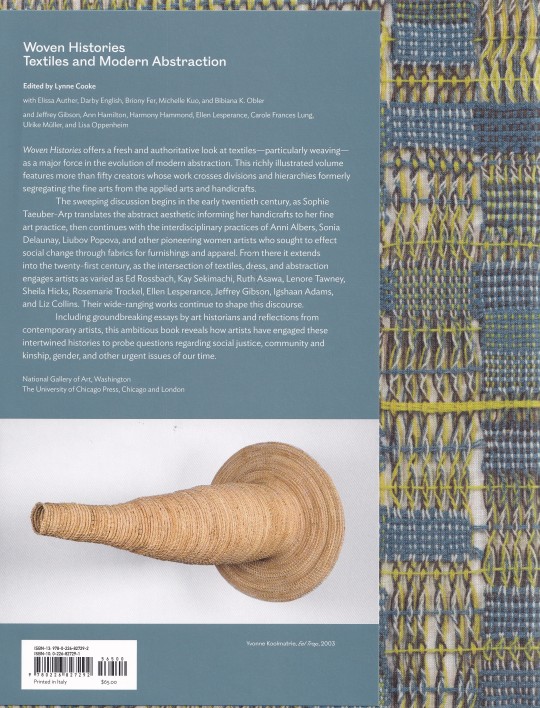

Woven Histories

Textiles and Modern Abstraction

Production by Brad Ireland and Christina Wiginton, Editing by Magda Nakassis,

National Gallery of Art, Washington copublished by The University of Chicago Press, 2023, 284 pages, ISBN 978-0-226-82729-2

euro 65,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Exhibition dates : Los Angeles County Museum Art 2023, Washington Nat.Gall.Art 2024, Ottawa Nat.Gall.Canada 2024,New York MoMA 2025

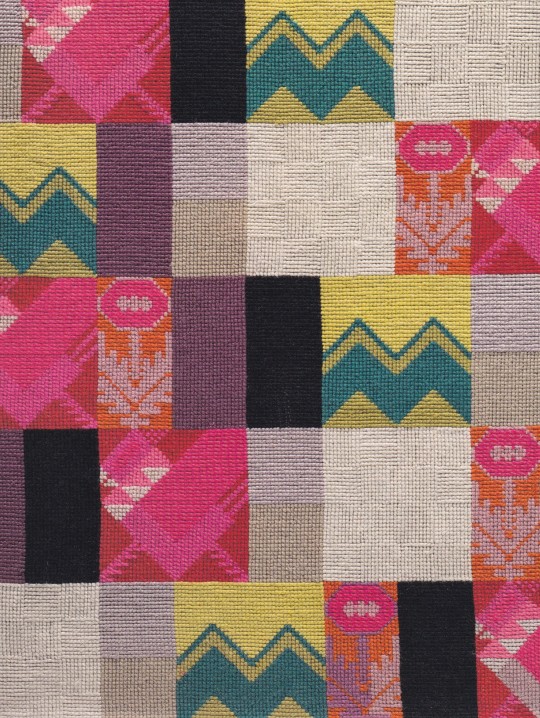

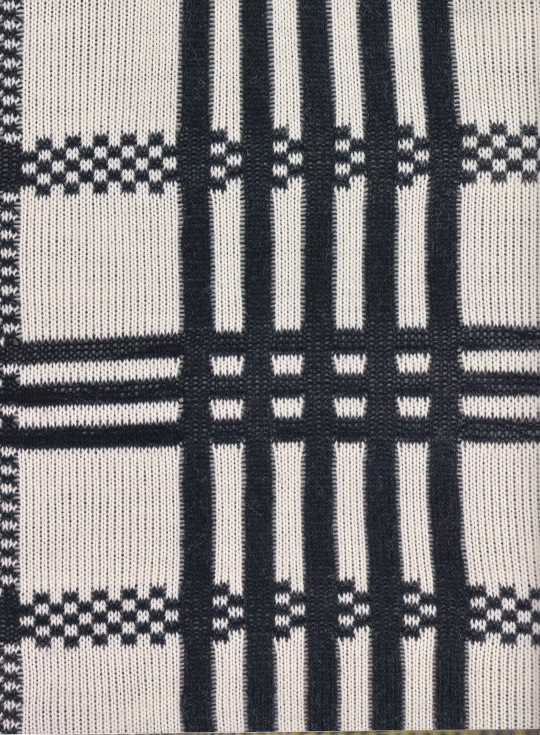

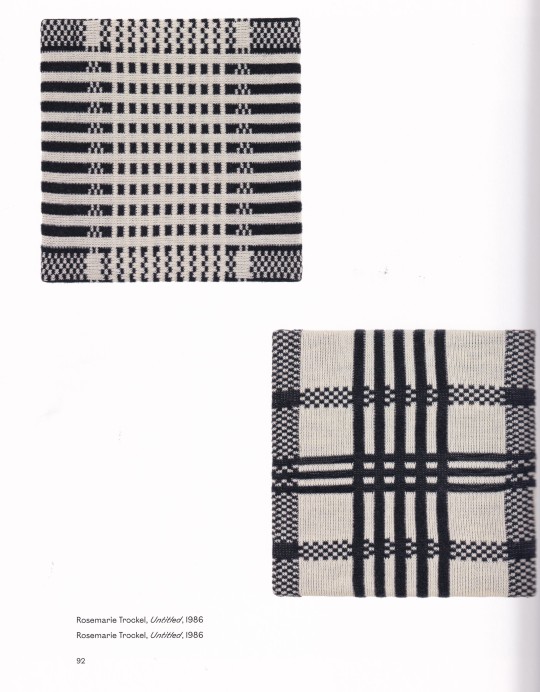

Richly illustrated volume exploring the inseparable histories of modernist abstraction and twentieth-century textiles. Published on the occasion of an exhibition curated by Lynne Cooke, Woven Histories offers a fresh and authoritative look at textiles—particularly weaving—as a major force in the evolution of abstraction. This richly illustrated volume features more than fifty creators whose work crosses divisions and hierarchies formerly segregating the fine arts from the applied arts and handicrafts. Woven Histories begins in the early twentieth century, rooting the abstract art of Sophie Taeuber-Arp in the applied arts and handicrafts, then features the interdisciplinary practices of Anni Albers, Sonia Delaunay, Liubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova, and others who sought to effect social change through fabrics for furnishings and apparel. Over the century, the intersection of textiles and abstraction engaged artists from Ed Rossbach, Kay Sekimachi, Ruth Asawa, Lenore Tawney, and Sheila Hicks to Rosemarie Trockel, Ellen Lesperance, Jeffrey Gibson, Igshaan Adams, and Liz Collins, whose textile-based works continue to shape this discourse. Including essays by distinguished art historians as well as reflections from contemporary artists, this ambitious project traces the intertwined histories of textiles and abstraction as vehicles through which artists probe urgent issues of our time.

24/12/23

#Woven Histories#textiles#modern abstraction#Anni Albers#Sonia Delaunay#Popova#Stepanova#Lenore Tawney#Sheila Hicks#textiles books#fashion books#fashionbooksmilano

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish dress history sources online:

A list of sources for Irish dress history research that free to access on the internet:

Primary and period sources:

Text Sources:

Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT): a database of historical texts from or about Ireland. Most have both their original text and, where applicable, an English translation. Authors include: Francisco de Cuellar, Luke Gernon, John Dymmok, Thomas Gainsford, Fynes Moryson, Edmund Spenser, Laurent Vital, Tadhg Dall Ó hUiginn

Images:

The Edwin Rae Collection: A collection of photographs of Irish carvings dating 1300-1600 taken by art historian Edwin Rae in the mid-20th c. Includes tomb effigies and other figural art.

National Library of Ireland: Has a nice collection of 18th-20th c. Irish art and photographs. Search their catalog or browse their flickr.

Irish Script on Screen: A collection of scans of medieval Irish manuscripts, including The Book of Ballymote.

The Book of Kells: Scans of the whole thing.

The Image of Irelande, with a Discoverie of Woodkarne by John Derricke published 1581. A piece of anti-Irish propaganda that should be used with caution. Illustrations. Complete text.

Secondary sources:

Irish History from Contemporary Sources (1509-1610) by Constantia Maxwell published 1923. Contains a nice collection of primary source quotes, but it sometimes modernizes the 16th c. English in ways that are detrimental to the accuracy, like changing 'cote' to 'coat'. The original text for many of them can be found on CELT, archive.org, or google books.

An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish By Joseph Cooper Walker published 1788. Makes admirable use of primary sources, but because of Walker's assumption that Irish dress didn't change for the entirety of the Middle Ages, it is significantly flawed in a lot of its conclusions. Mostly only useful now for historiography. I discussed the images in this book here.

Chapter 18: Dress and Personal Adornment from A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland by P. W. Joyce published 1906. Suffers from similar problems to An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish.

Consumption and Material Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland Susan Flavin's 2011 doctoral thesis. A valuable source on the kinds of materials that were available in 16th c Ireland.

A Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy Volumes 1 and 2 by William Wilde, published 1863. Obviously outdated, and some of Wilde's conclusions are wrong, because archaeologists didn't know how to date things in the 19th century, but his descriptions of the individual artifacts are worthwhile. Frustratingly, this is still the best catalog available to the public for the National Museum of Ireland Archaeology. Idk why the NMI doesn't have an online catalog, a lot museums do nowadays.

Volume I: Articles of stone, earthen, vegetable and animal materials; and of copper and bronze

Volume 2: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities of Gold in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy

A Horsehair Woven Band from County Antrim, Ireland: Clues to the Past from a Later Bronze Age Masterwork by Elizabeth Wincott Heckett 1998

Jewellery, art and symbolism in Medieval Irish society by Mary Deevy in Art and Symbolism in Medieval Europe- Papers of the 'Medieval Europe Brugge 1997' Conference (page 77 of PDF)

Looking the part: dress and civic status and ethnicity in early-modern Ireland by Brid McGrath 2018

Irish Mantles, English Nationalism: Apparel and National Identity in Early Modern English and Irish Texts by John R Ziegler 2013

Dress and ornament in early medieval Ireland - exploring the evidence by Maureen Doyle 2014

Dress and accessories in the early Irish tale, ‘The Wooing of Becfhola’ by Niamh Whitfield 2006

A tenth century cloth from Bogstown Co. Meath by Elizabeth Wincott Heckett 2004

Tertiary Sources:

Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia edited by Sean Duffy published 2005

Re-Examining the Evidence: A Study of Medieval Irish Women's Dress from 750 to 900 CE by Alexandra McConnell

#resources#dress history#irish dress#irish history#early medieval#bronze age#textile history#late medieval#16th century#historical dress

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below are 10 articles from Wikipedia's featured articles list. Links and descriptions are below the cut.

On Saturday, May 1, 1920, the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Boston Braves played to a 1–1 tie in 26 innings, the most innings ever played in a single game in the history of Major League Baseball. Both Leon Cadore of Brooklyn and Joe Oeschger of Boston pitched complete games, and with 26 innings pitched, jointly hold the record for the longest pitching appearance in MLB history.

Clarence 13X, also known as Allah the Father (born Clarence Edward Smith) (February 22, 1928 – June 13, 1969), was an American religious leader and the founder of the Five-Percent Nation, sometimes referred to as the Nation of Gods and Earths.

Henry Edwards (27 August 1827 – 9 June 1891) was an English stage actor, writer and entomologist who gained fame in Australia, San Francisco and New York City for his theatre work.

The law school of Berytus (also known as the law school of Beirut) was a center for the study of Roman law in classical antiquity located in Berytus (modern-day Beirut, Lebanon). It flourished under the patronage of the Roman emperors and functioned as the Roman Empire's preeminent center of jurisprudence until its destruction in AD 551.

Minnie Pwerle (also Minnie Purla or Minnie Motorcar Apwerl; born between 1910 and 1922 – 18 March 2006) was an Australian Aboriginal artist. Minnie began painting in 2000 at about the age of 80, and her pictures soon became popular and sought-after works of contemporary Indigenous Australian art.

Ove Jørgensen (Danish pronunciation: [ˈoːvə ˈjœˀnsən]; 5 September 1877 – 31 October 1950) was a Danish scholar of classics, literature and ballet. He formulated Jørgensen's law, which describes the narrative conventions used in Homeric poetry when relating the actions of the gods.

Legends featuring pig-faced women originated roughly simultaneously in The Netherlands, England and France in the late 1630s. The stories tell of a wealthy woman whose body is of normal human appearance, but whose face is that of a pig.

The Private Case is a collection of erotica and pornography held initially by the British Museum and then, from 1973, by the British Library. The collection began between 1836 and 1870 and grew from the receipt of books from legal deposit, from the acquisition of bequests and, in some cases, from requests made to the police following their seizures of obscene material.

Qalaherriaq (Inuktun pronunciation: [qalahəχːiɑq], c. 1834 – June 14, 1856), baptized as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua, was an Inughuit hunter from Cape York, Greenland. He was recruited in 1850 as an interpreter by the crew of the British survey barque HMS Assistance during the search for John Franklin's lost Arctic expedition.

Sophie Blanchard (French pronunciation: [sɔfi blɑ̃ʃaʁ]; 25 March 1778 – 6 July 1819), commonly referred to as Madame Blanchard, was a French aeronaut and the wife of ballooning pioneer Jean-Pierre Blanchard. Blanchard was the first woman to work as a professional balloonist, and after her husband's death she continued ballooning, making more than 60 ascents.

#Wikipedia polls#people said they liked the summaries-first format but it got fewer votes in total so i think I'll stick with summaries-after-the-cut#i would recommend checking out the readmore before you vote though. or don't I'm not your boss

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

As modern science and better archeology methods reexamine historical sites more of women’s history will emerge

by Sarah Durn September 27, 2021

The National Museum of Stockholm's Ride of the Valkyries was painted during the Victorian period, which saw renewed interest in Vikings. Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

In 1871 on the sleepy island of Birka, Sweden, Hjalmar Stolpe, a Swedish entomologist turned archaeologist, discovered the lavish grave of a Viking warrior. Around the seated body were the remains of two sacrificed horses, as well as a double-edged sword, a scramasax (a long, thin knife), a bow, a shield, and a spear—every weapon known to the Viking world. It was an astonishing find, especially since Viking warrior graves rarely contain more than three weapons. There was also a full set of hnefatafl, the board game often known as Viking chess, which indicates the strategic thinking and authority of a war leader. A thousand years ago, the site would’ve abutted the Warrior’s Hall, where a garrison lived to protect the bustling Viking town of Birka. The weapons, game pieces, location: Everything told scholars that the man buried in what is known as grave Bj 581 was a prominent, well-respected Viking warrior. No one was really prepared when DNA tests were conducted in 2017 and a new story began to emerge. This was a prominent warrior, all right, but the occupant of Bj 581 wasn’t a man. She was a woman.

Viking historian Nancy Marie Brown’s new book, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women, explores what life might have been like for the warrior woman of Bj 581.

Using more evidence from the recent tests conducted on the remains, Brown traces her journey from Norway to the British Isles to Kiev then, finally, to Birka. Brown imagines the unnamed warrior meeting other prominent Viking women, such as Gunnhild, Mother of Kings, or Queen Olga, ruler of the Rus Vikings in Kiev. She also explores the Viking sagas and contemporary sources with a new lens.

How did you initially get interested in Vikings—and female Vikings in particular?

When I went to college, I actually wanted to study fantasy writing and, you know, learn to write like Tolkien. I learned very quickly that that was not appropriate for an English major in the 1970s, so I decided to study what Tolkien studied, and he was a professor at Oxford University, teaching Old English and Old Norse. So I started reading all of the Icelandic sagas that I could find in translation. And when I ran out of the English versions, I learned Old Norse so that I could read the rest of them.

One of the things I liked about [the sagas] the most was that they had really interesting women characters. There’s a queen in Norway who appears in about 11 sagas, Queen Gunnhild, Mother of Kings. She led armies. She devised war strategy. And then I was looking at the valkyries and the shieldmaids and thinking, you know, these are really interesting people that have always been considered to be mythological.

So when I learned in 2017 that one of the most famous Viking warrior burials turned out to be the burial of a woman, that just absolutely dazzled my imagination.

Is this the first confirmed grave of a female warrior that we have?

This is the one that has the best proof. There are one or two others that have since been DNA tested and proven to be female. But in each of these cases, it’s hard to say if the person in the grave, whether male or female, actually was a warrior, or if the object that we are interpreting as a weapon was used for hunting or for some other purpose.

In this case, it’s every Viking weapon known to history. So it’s such a clear result. And the DNA was so completely female.

When Stolpe discovered the Viking gravesite Bj 581 in 1887, he assumed the remains were of a man. That assumption was shown to be wrong 140 years later. Rapp Halour / Alamy Stock Photo

What do we know about the life of the Viking warrior woman in Bj 581?

In 2017, by testing her bones and her teeth, [scholars] could say she was between 30 and 40 years old when she died. They could also tell that she ate well all of her life. So she came from a rich family or maybe even a royal one. She was also quite tall, about 5’7”. By the minerals in her inner teeth, [scholars can determine] she may have come from southern Sweden or Norway, and also that she went west maybe as far as the British Isles before her molars finished forming. She didn’t arrive in Birka until she was 16.

We also have her weapons and a little bit of clothing that were found in the grave. And these link her to what is known as the Vikings’ East Way, which was the trade route from Sweden to the Silk Road.

We can link, through the artifacts and through the bones, that she could have traveled from as far west as Dublin to as far east as at least Kiev in the 30 to 40 years of her life.

How do we know that there were Viking warrior women?

They are mentioned many, many, many times in the literature. In most cases, they have been dismissed as mythological because, of course, we know warriors were men. But we don’t know that. That is an assumption that is based on traditional Victorian ideas that because women are mothers, they’re nurturing, they’re peacemakers, and they don’t fight.

That’s not historically true. Women have always fought. And they appear in most cultures until the 1800s, when Viking studies and archaeology pretty much started. So we sort of have this problem of bias in our earliest textbooks.

But now we have actual scientific proof of one warrior woman in the Viking Age. And as the scientists who did the study say they would be very surprised if she was the only one.

This small female Viking warrior figurine discovered in Harby, Denmark, has been interpreted as a mythological valkyrie. John Lee / National Museum of Denmark

There’s this assumption that the warrior men of myth must have been based on real people, but it’s not the same for the mythical warrior women. Why is that?

It’s just an assumption based on what people think women are like. Most of the material we have from the Middle Ages was written by men, and most of the material we have until the 1950s was written by men, and women are slowly making their way into the field of Viking scholarship. But many of them are still working under the assumptions that they were taught.

I noticed when I went back and reread some of the sagas in Icelandic that there wasn’t this clear distinction between the warrior women being mythological and the warrior men being human. When you actually look at the old Norse text, there’s a lot of words that have been translated as “men” that actually mean “people,” but it’s always been translated as “men” because it’s a warrior situation.

If you’re translating, you have to make decisions and sometimes your decisions have repercussions that you don’t expect, like writing women out of the history.

By the time Hjalmar Stolpe excavated Bj 581, he had become adept at recognizing where graves could be found in the hummocky Birka landscape. WS Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Is it possible for historians to remove all of those biases?

No, I don’t think it is. I think we all are looking through our own lenses. But we have to revisit those sources every generation to see past biases. So when you have layer after layer after layer of removing biases, you may get closer to the truth.

What most surprised you in the course of researching your book?

One of the controversies right now in Viking studies is should we really be talking about men and women at all? Maybe there were all kinds of different genders. We don’t know if there were more than two genders in the Viking age. Maybe it was a spectrum.

If you look at this one group of sagas called the Sagas of Ancient Times that are often overlooked because they have all these fabulous creatures in them, like dragons and warrior women. It’s really interesting [because] these girls grow up wanting to be warriors. They’re constantly disobeying and trying to run off and join Viking bands. But when they do run off and join the Viking band, or, in another case, become the king of a town, they insist on being called by a male name and use male pronouns.

So it was very shocking to me to go back and read it in the original and say, “Wow, all this richness was lost in the translation.”

#Nancy Marie Brown#The Real Valkyrie#Books by women#Books about women#Atlas Obscura#She Was There#Sweden#Birka#grave Bj 581#Warrior women#Vikings’ East Way

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jan Nelson, Walking in tall grass, Shelby 2, 2011, oil on linen, 79 h cm, 56 w cm, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, warwick and Jane Flecknoe Bequest Fund 2015 © Jan Nelson/Copyright Agency

Jan Nelson (born 1955) is an Australian artist who works in sculpture, photography and painting. She is best known for her hyper real images of adolescents. She has exhibited widely in Australia as well as Paris and Brazil. Her works are in the collections of Australian galleries, including the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney and the Gallery of Modern Art Brisbane, as well as major regional galleries. She represented Australia in the XXV biennale in São Paulo, Brazil.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you make a post about the evolution of Greek art from the ancient times until now in modern age?

Because we often talk about the evolution of art but unfortunately we don't appreciate after ancient times the other art movements Greece went through the centuries.

That’s true! I am sorry for taking ages to answer this but I don't know how it could take me less anyway hahaha I made this post with summaries about all artistic eras in Greek history. I have most of it under a cut because with the addition of pictures it got super long, but if you are interested in the history of art I recommend giving it a try! I took advantage of all 30 pictures that can be possibly attached in a tumblr post and I tried to cover as many eras and art styles as possible, nearly dying in the process ngl XD I dedicated a few more pictures in modern art, a) because that was the ask and b) because there is more diversity in the styles that are used and the works that are available to us in great condition in modern times.

History of Greek Art

Greek Neolithic Art (c. 7000 - 3200 BC)

Obviously, with this term we don’t mean there were people identifying as Greeks in Neolithic times, but it defines the Neolithic art corresponding to the Greek territory. Art in this era is mostly functional, there are progressively more and more defined designs on clay pots, tools and other utility items. Clay and obsidian are the most used materials.

Clay vase with polychrome decoration, Dimini, Magnesia, Late or Final Neolithic (5300-3300 BC).

Cycladic Art (3300 - 1100 BC)

The art of the Cycladic civilisation of the Aegean Islands is characterized by the use of local marble for the creation of sculptures, idols and figurines which were often associated to womanhood and female deities. Cycladic art has a unique way of incidentally feeling very relevant, as it resembles modern minimalism.

Early Cycladic II (Keros-Syros culture, 2800–2300 BC)

Minoan Art (3000-1100 BC)

The advanced Minoan civilisation of Crete island was projecting its confidence and its vibrancy through its various arts. Minoan art was influenced by the earlier Egyptian and Near East cultures nearby and at its peak it overshadowed the rest of the contemporary cultures and their artistic movements in Greece. Colourful, with numerous scenes of everyday life and island life next to the sea, it was telling of the society’s prosperity.

The Bull-leaping fresco from Knossos, 1450 BC.

Mycenaean Art (c. 1750 - 1050 BC)

Mycenaean Art was very influenced by Minoan Art. Mycenaean art diverged and distinguished itself more in warcraft, metalwork, pottery and the use of gold. Even when similar, you can tell them apart from their themes, as Mycenaean art was significantly more war-centric.

The Mask of Agamemnon in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. The mask likely was crafted around 1550 BC so it predates the time Agamemnon perhaps lived.

Geometric Art (1100 - 700 BC)

Corresponding to a period we have comparatively too little data about, the Geometric Period or the Homeric Age or the Greek Dark Ages, geometric art was characterized by the extensive use of geometric motifs in ceramics and vessels. During the late period, the art becomes narrative and starts featuring humans, animals and scenes meant to be interpreted by the viewer.

Detail from Geometric Krater from Dipylon Cemetery, Athens c. 750 BC Height 4 feet (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

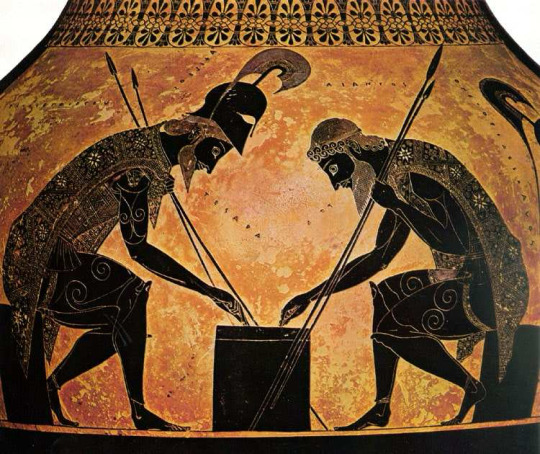

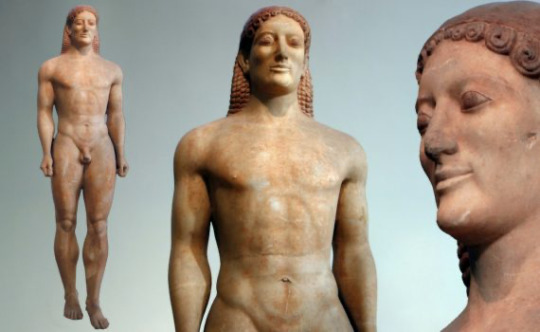

Archaic Art (c. 800 - 480 BC)

The art of the archaic period became more naturalistic and representational. With eastern influences, it diverged from the geometric patterns and started developing more the black-figure technique and later the red-figure technique. This is also the earliest era of monumental sculpture.

Achilles and Ajax Playing a Board Game by Exekias, black-figure, ca. 540 B.C.

Kroisos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.

Classical Art (c. 480 - 323 BC)

Art in this era obtained a vitality and a sense of harmony. There is tremendous progress in portraying the human body. Red-figure technique definitively overshadows the use of the black-figure technique. Sculptures are notable for their naturalistic design and their grandeur.

The Diskobolos or Discus Thrower, Roman copy of a 450-440 BCE Greek bronze by Myron recovered from Emperor Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, Italy. (British Museum, London). Photo by Mary Harrsch.

Terracotta bell-krater, Orpheus among the Thracians, ca. 440 BCE, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hellenistic Art (323 - 30 BCE)

Hellenistic art perfects classical art and adds more diversity and nuance to it, something that can be explained by the rapid geographical expansion of Greek influence through Alexander’s conquests. Sculpture, painting and architecture thrived whereas there is a decrease in vase painting. The Corinthian style starts getting popular. Sculpture becomes even more naturalistic and expresses emotion, suffering, old age and various other states of the human condition. Statues become more complex and extravagant. Everyday people start getting portrayed in art and sculpture without extreme beauty standards imposed. We know there was a huge rise in wall painting, landscape art, panel painting and mosaics.

Mosaic from Thmuis, Egypt, created by the Ancient Greek artist Sophilos (signature) in about 200 BC, now in the Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria, Egypt. The woman depicted in the mosaic is the Ptolemaic Queen Berenike II (who ruled jointly with her husband Ptolemy III) as the personification of Alexandria.

Agesander, Athenodore and Polydore: Laocoön and His Sons, 1st century BC

Greco-Roman Art (30 BC - 330 AD)

This period is characterized by the almost entire and mutually influential merging of Greek and Roman artistic expression, in light of the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world. For this era, it is hard to find sources exclusively for Greek art, as often even art crafted by Greeks of the Roman Empire is described as Roman. In general, Greco-Roman art reinforces the new elements of Hellenistic art, however towards the end of the era, with the rise of early Christianity in the Eastern aka the Greek-influenced part of the empire, there are some gradual shifts in the art style towards modesty and spirituality that will in time lead to the Byzantine art. During this era mosaics become more loved than ever.

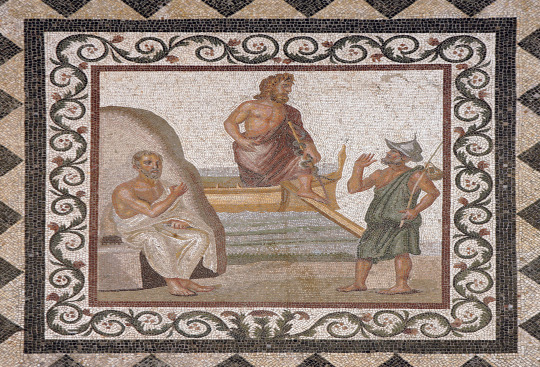

A mosaic from the island of Kos (the birthplace of Hippocrates) depicting Hippocrates (seated) and a fisherman greeting the god Asklepios (center) as he either arrives or disembarks from the island. Second or third century CE.

Introduction to Byzantine Art

Byzantine art originated and evolved from the now Christian Greek culture of the Eastern Roman Empire. Although the art produced in the Byzantine Empire was marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, it was above all marked by the development of a new aesthetic defined by its salient "abstract", or anti-naturalistic character. If classical art was marked by the attempt to create representations that mimicked reality as closely as possible, Byzantine art seems to have abandoned this attempt in favor of a more symbolic approach. The subject matter of monumental Byzantine art was primarily religious and imperial: the two themes are often combined.

Early Byzantine Art (330 - 842 AD)

The establishment of the Christian religion results in a new artistic movement, centered around the faith. However, ancient statuary remains appreciated. Most fundamental changes happen in monumental architecture, the illustration of manuscripts, ivory carving and silverwork. Exceptional mosaics become integral in artistic expression. The last 100 years of this period are defined by the Iconoclasm, which temporarily restricts entirely the previously thriving figural religious art.

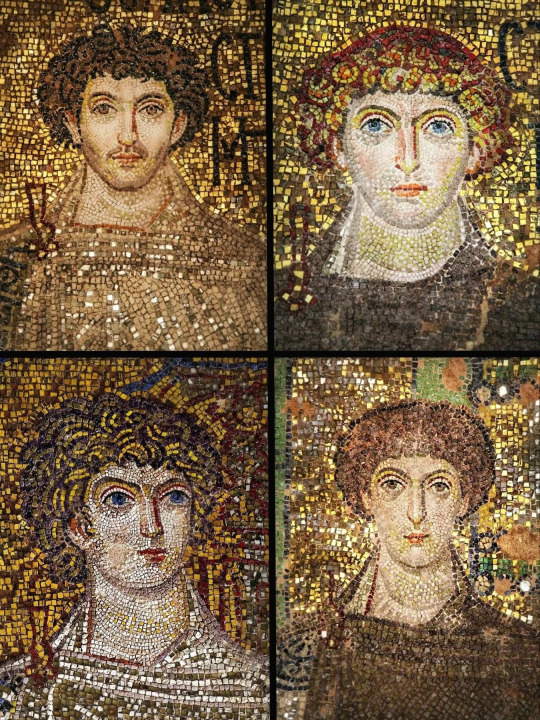

Mosaics in the Rotunda of Thessaloniki, 4th - 6th century AD.

Macedonian Art & Komnenian Age (843 - 1204 AD)

These artistic periods correspond to the middle Byzantine period. After the end of the Iconoclasm, there is a revival in the arts. The art of this period is frequently called Macedonian art, because it occurred during the Macedonian imperial dynasty which generally brought a lot of prosperity in the empire. There was a revival of interest in the depiction of subjects from classical Greek mythology and in the use of Hellenistic styles to depict religious subjects. The Macedonian period also saw a revival of the late antique technique of ivory carving. The following Komnenian dynasty were great patrons of the arts, and with their support Byzantine artists continued to move in the direction of greater humanism and emotion. Ivory sculpture and other expensive mediums of art gradually gave way to frescoes and icons, which for the first time gained widespread popularity across the Empire. Apart from painted icons, there were other varieties - notably the mosaic and ceramic ones.

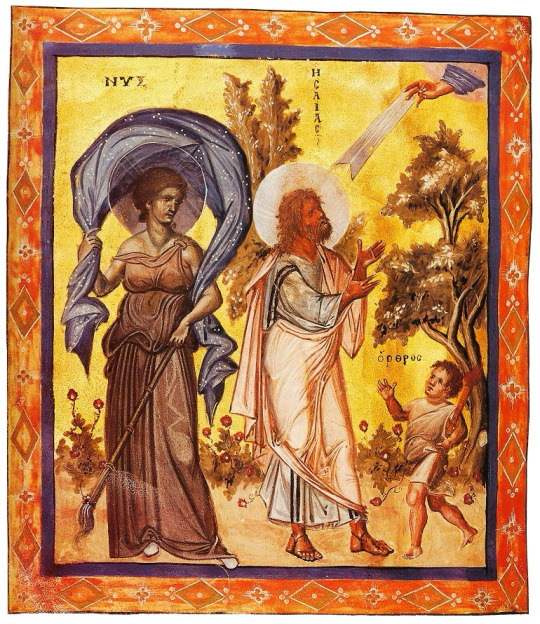

Paris Psalter, 10th century AD. Prophet Isaiah from the Old Testament in the company of the symbolisms for night (clear inspiration drawn from the ancient deity Nyx) and morning (Orthros, not to be confused with the mythological creature).

Palaeologan Renaissance (1261 - 1453)

The Palaeologan Renaissance is the final period in the development of Byzantine art. Coinciding with the reign of the Palaeologi, the last dynasty to rule the Byzantine Empire (1261–1453), it was an attempt to restore Byzantine self-confidence and cultural prestige after the empire had endured a long period of foreign occupation. The legacy of this era is observable both in Greek culture after the empire's fall and in the Italian Renaissance. Contemporary trends in church painting favored intricate narrative cycles, both in fresco and in sequences of icons. The word "icon" became increasingly associated with wooden panel painting, which became more frequent and diverse than fresco and mosaics. Small icons were also made in quantity, most often as private devotional objects.

Detail of Anástasis (Resurrection) fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist).

Cretan School (15th - 17th century)

Cretan School describes an important school of icon painting, under the umbrella of post-Byzantine art, which flourished while Crete was under Venetian rule during the Late Middle Ages, reaching its climax after the Fall of Constantinople, becoming the central force in Greek painting during the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. By the late 15th century, Cretan artists had established a distinct icon-painting style, distinguished by "the precise outlines, the modelling of the flesh with dark brown underpaint, the bright colours in the garments, the geometrical treatment of the drapery and, finally, the balanced articulation of the composition". Contemporary documents refer to two styles in painting: the maniera greca (in line with the Byzantine idiom) and the maniera latina (in accordance with Western techniques), which artists knew and utilized according to the circumstances. Sometimes both styles could be found in the same icon. The most famous product of the school was the painter Domenikos Theotokopoulos, internationally known as El Greco, whose art evolved and diverged significantly in his later years when he moved in Spain and was involved in the Spanish Renaissance, and though it often alienated his western contemporary artists, nowadays it is viewed as an incidental early birth of Impressionism in the mid of the Renaissance’s peak.

Icon by Andreas Pavias (1440-1510), Cretan School, from Candia (Venetian Kingdom of Crete). The Latin inscription suggests the icon was meant for commercial purposes in Western Europe. National Museum, Athens. (Source: https://russianicons.wordpress.com/tag/cretan-school/)

Crucifixion (detail), El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos), ca. 1604 - 1614.

Heptanesian School (17th - 19th century)

The Heptanesian school succeeded the Cretan School as the leading school of Greek post-Byzantine painting after Crete fell to the Ottomans in 1669. Like the Cretan school, it combined Byzantine traditions with an increasing Western European artistic influence and also saw the first significant depiction of secular subjects. The center of Greek art migrated urgently to the Heptanese (Ionian) islands but countless Greek artists were influenced by the school including the ones living throughout the Greek communities in the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere in the world. Greek art was no longer limited to the traditional maniera greca dominant in the Cretan School. Furthermore, the Heptanesian school was the basis for the emergence of new artistic movements such as the Greek Rocco and Greek Neoclassicism. The movement featured a mixture of brilliant artists.

Archangel Michael, Panagiotis Doxaras, 18th century.

Greek Romanticism (19th century)

Modern Greek art, after the establishment of the Greek Kingdom, began to be developed around the time of Romanticism. Greek artists absorbed many elements from their European colleagues, resulting in the culmination of the distinctive style of Greek Romantic art, inspired by revolutionary ideals as well as the country's geography and history.

Vryzakis Theodoros, The Exodus from Missolonghi, 1853. National Gallery, Athens.

The Munich School (19th century Academic Realism)

After centuries of Ottoman rule, few opportunities for an education in the arts existed in the newly independent Greece, so studying abroad was imperative for artists. The most important artistic movement of Greek art in the 19th century was academic realism, often called in Greece "the Munich School" because of the strong influence from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Munich where many Greek artists trained. In academic realism the imperative is the ethography, the representation of urban and/or rural life with a special attention in the depiction of architectural elements, the traditional cloth and the various objects. Munich School painters were specialized on portraiture, landscape painting and still life. The Munich school is characterized by a naturalistic style and dark chiaroscuro. Meanwhile, at the time we observe the emergence of Greek neoclassicism and naturalism in sculpture.

Nikolaos Gyzis, Learning by heart, 1883.

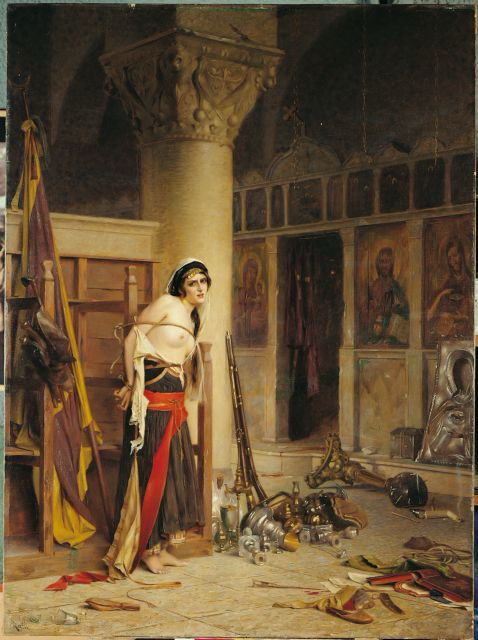

Rallis Theodoros, The Booty, before 1906.

20th Century Modern & Contemporary Greek Art

At the beginning of the 20th century the interest of painters turned toward the study of light and color. Gradually the impressionists and other modern schools increased their influence. The interest of Greek painters, artists changes from historical representations to Greek landscapes with an emphasis on light and colours so abundant in Greece. Representatives of this artistic change introduce historical, religious and mythological elements that allow the classification of Greek painting into modern art. The era of the 1930s was a landmark for the Greek painters. The second half of the 20th century has seen a range of acclaimed Greek artists too serving the movements of surrealism, metaphysical art, kinetic art, Arte Povera, abstract excessionism and kinetic sculpture.

Yiannis Moralis, Two friends, 1946.

Art by Giannis Gaitis (1923-1984), famous for his uniformed little men.

By Yorghos Stathopoulos (1944 - )

Art (detail) by Nikos Engonopoulos (1907 - 1985)

Folk, Modern Ecclesiastical and Secular Post-Byzantine Art

Ecclesiastical art, church architecture, holy painting and hymnology follow the order of Greek Byzantine tradition intact. Byzantine influence also remained pivotal in folk and secular art and it currently seems to enjoy a rise in national and international interest about it.

A modern depiction of the legendary hero Digenes Akritas depicted in the style of a Byzantine icon by Greek artist Dimitrios Skourtelis. Credit: Dimitrios Skourtelis / Reddit

Erotokritos and Aretousa by folk artist Theophilos (1870-1934)

Example of Modern Greek Orthodox murals, Church of St. Nicholas.

Ancient Greek philosophers depicted in iconographic fashion in one of Meteora’s monasteries. Each is holding a quote from his work that seems to foreshadow Christ. Shown from left to right are: Homer, Thucydides, Aristotle, Plato and Plutarch. This is not as weird as it may initially seem: it was a recurrent belief throughout the history of Christian Greek Orthodoxy that the great philosophers of the world heralded Jesus' birth in their writings - it was part of the eras of biggest reconciliation between Greek Byzantinism and Classicism.

Prophet Elijah icon with Chariot of Fire, Handmade Greek Orthodox icon, unknown iconographer. Source

If you see this, thanks very much for reading this post. Hope you enjoyed!

#greece#art#europe#history#culture#greek art#artists#greek culture#history of art#classical art#ancient greek art#byzantine greek art#christian art#orthodox art#modern art#modern greek art#anon#ask

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untitled. By Gaylord Oscar Herron. Tulsa, Oklahoma. 1973.

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

#Gaylord Oscar Herron#history#culture#art#modern history#american art#national museum of african american history and culture#American history#oklahoma#Oklahoman history#contemporary history#Tulsa#the smithsonian#photography

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ģederts Eliass (Latvian, 1887-1975, lived and worked in Riga, Latvia), Pie spoguļa (By the Mirror), 1918. (Source: Latvian National Museum of Art, Rīga, Latvija)

#art#artwork#modern art#contemporary art#modern artwork#contemporary artwork#20th century modern art#20th century contemporary art#Latvian art#Latvian artwork#modern Latvian art#contemporary latvian art#modernist Latvia#Latvian artist#Latvian painter#Ģederts Eliass#Latvian National Museum of Art#Latvian modernism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Theft

Five things you probably didn’t know about the biggest art heist in history

Most art galleries and museums are famous for the art they contain. London’s National Gallery has Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers”; “The Starry Night” meanwhile, is held at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, in good company alongside Salvador Dalì’s melting clocks, Andy Warhol’s soup cans and Frida Kahlo’s self-portrait.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, however, is now more famous for the artwork that is not there, or at least, that is no longer there.

On March 18 1990 the museum fell prey to history’s biggest art heist. Thirteen works of art estimated to be worth over half a billion dollars — including three Rembrandts and a Vermeer — were stolen in the middle of the night, while the two security guards sat in the basement bound in duct tape.

The robbery is a treasure trove of surprising facts and unexpected plot twists. Here are five things that make the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and its famous theft, so interesting.

The woman behind the building:

Isabella Stewart Gardner, the museum’s founder and namesake, is a fascinating character. The daughter and eventual widow of two successful businessmen, Gardner was a philanthropist and art collector who built the museum to house her stash.

“When she opened the museum in 1903 she mandated that it be free of charge, to gain the appreciation and the attendance of all of Boston,” Stephan Kurkjian, author of “Master Thieves: The Boston Gangsters Who Pulled Off the World’s Greatest Art Heist”, said in the programme. “Her museum, at that point in time, was the largest collection of art by a private individual in America.”

Gardner also had links to the fledgling campaign for women’s political rights. The museum displays the photographs and letters of her friend Julia Ward Howe, an organizer of two US suffrage societies, and a print of Ethel Smyth, a composer and close friend of the English Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst.

Gardner met Smyth through their mutual friend, the painter John Singer Sargent, whose portrait of Gardener raised eyebrows for the low-cut neckline he gave her.

Gardner seemed to enjoy flirting with scandal and gossip: she once arrived at a Boston Symphony Orchestra performance in a hat band emblazoned with the name of her favorite baseball team, Red Sox, and an illustration in a January 1897 edition of the Boston Globe showed her apparently taking one of Boston Zoo’s lions for a walk.

Somewhat ironically, when the Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911, Gardner told her museum guards that, if they saw anyone trying to rob them, they should shoot to kill.

The art not taken:

The thieves’ loot is estimated to be worth over half a billion dollars. However, they left the building’s most expensive artifact: “The Rape of Europa” by Titian, which Gardner bought from a London art gallery in 1896, then a record price for an old master painting.

Why commit history’s greatest art heist and leave without the priciest piece in the museum? Well, size may have played a role. The largest artwork taken was Rembrandt’s “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee,” famous for being Rembrandt’s only seascape and measures roughly 5x4 feet. “The Rape of Europa,” meanwhile, is larger, at nearly 6x7 feet.

The Napoleon factor:

Around 2005, the investigation into the stolen artworks took a detour to the French island of Corsica in the Meditteranean Sea. Two Frenchmen with alleged ties to the Corsican mob were trying to sell two paintings: a Rembrandt and a Vermeer. Former FBI Special Agent Bob Wittman was involved in a sting to try and buy them — but the operation eventually fell apart when the men were arrested for selling art taken from the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nice instead.

Why would “Corsican mobsters,” as correspondent Randi Kaye described them in the programme, be interested in robbing a Boston art museum? The answer could lie in the Bronze Eagle Finial, the 10-inch ornament stolen from the top of a Napoleonic flag during the heist.

“It was sort of an odd choice for the thieves to take (the Finial),” Kaye said, “but it turns out that Corsica is essentially the homeland of Napoleon.” The French emperor was born on the island in 1769, and a national museum is now housed in his former family home.

“It is a very compelling notion,” Kelly Horan, Deputy Editor of the Boston Globe, said in the programme, “that a Corsican band of gangsters might have tried to steal back their flag and pull off the entire rest of the heist in the process.”

A rock’n’roll suspect:

March 18 1990 was not the first time a Rembrandt had been stolen from a Boston museum. In 1975, career criminal and art thief Myles Connor walked into Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and walked out with a Rembrandt tucked into his oversized coat pocket. He was the FBI’s first suspect in the Gardner case, however the walls of federal prison — where he was incarcerated on drugs charges — gave him a pretty solid alibi.

When he wasn’t lifting famous artworks from their displays, Connor was a musician. It was through gigging that he met Al Dotoli, who worked with stars including Frank Sinatra and Liza Minelli.

In 1976 Connor was jailed for a separate art theft committed in Maine. Hoping to use his stolen Rembrandt to leverage a lesser sentence, he needed Dotoli — who was on tour with Dionne Warwick — to turn the painting in to the authorities on his behalf.

An invisible thief?

One of the stolen artworks, Édouard Manet’s “Chez Tortoni,” was taken from the museum’s Blue Room on the first floor. The painting stands out for two reasons, the first being its frame. The thieves left almost all of the frames behind, cutting some out of the front.

“To even leave remnants of the painting(s) behind was savage,” Horan said. “In my mind, it’s sort of like slashing someone’s throat.”

The “Chez Tortoni” frame was unusual for where it was left, though: not in the room it was stolen from, but in the chair of the security office downstairs. Even more remarkable, not a single motion detector was set off in the Blue Room. Bar investigating the possibility of ghost robbers, investigators wondered if this pointed to the plot being an inside job.

“At the FBI we found that about 89% of museum institutional heists are inside jobs,” Wittman said. “That’s how these things get stolen.”

By Caitlin Chatterton.

#The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Theft#The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston#Rembrandt#Govert Flinck#Édouard Manet#Johannes Vermeer#Edgar Degas#stolen art#looted art#painter#painting#art#artist#art work#art world#art news#long post#long reads

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

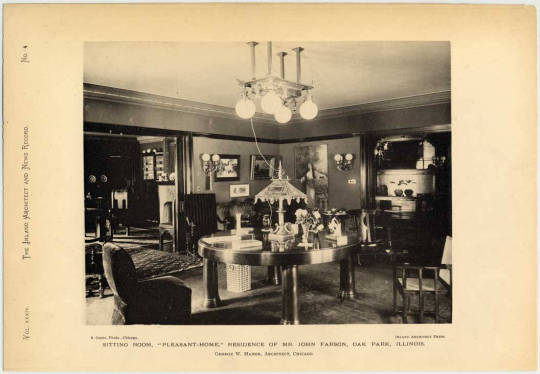

Pleasant Home, Oak Park IL

Pleasant Home (Farson-Mills House), 1897, 217 Home Avenue, Oak Park, IL 60302

Pleasant Home

George W. Maher designed this 30-room mansion for millionaire banker John W. Farson of Oak Park. Farson purchased the lot at the corner of Pleasant St. and Home Ave. in 1892 for $20,000, the largest price ever paid for a residential lot in Oak Park. Over the following years he acquired land to the south and west for a large garden.

Herbert S. Mills, the second owner of Pleasant Home, made his fortune in the amusement business. The Mills family sold the house in 1939 to the Park District of Oak Park, the grounds being designated as Mills Park in their honor.

The home today is operated as a historic house museum, an events venue, and serves as the headquarters for The Pleasant Home Foundation.

The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Illustration of Pleasant Home from The Inland Architect and News Record

Considered one of the earliest examples of prairie school architecture, Pleasant Home is often viewed as the finest surviving example of Maher's residential work. The house was completed three years after Frank Lloyd Wright's Winslow House in River Forest, an early expression of Wright's emerging design principles, later to be known as the prairie style.

The Prairie School developed in sympathy with the ideals and design aesthetics of the Arts and Crafts movement of 19th century England by John Ruskin, William Morris, and others. It is also seen as a successor to the Chicago School of architecture associated with architects William Le Baron Jenney, H.H. Richardson, Daniel H. Burnham, John Wellborn Root, Dankmar Adler, and Louis Sullivan.

The Prairie School attempted to develop an indigenous North American style of architecture, without the design elements and aesthetic vocabulary of earlier styles of European-influenced architecture such as the Queen Anne and Gothic Revival styles.

The smooth surfaces of Roman brick, the low-pitched, hipped roof and the broad entrance porch of the Parson House are characteristic features of Maher's work that link him to the early modern designs of his Prairie School contemporaries. In the Parson House Maher also introduced his personal design philosophy, which he called motif rhythm theory, to unify the decorative details of the house and its furnishings. The house retains its historic integrity in terms of materials, design and setting. Virtually all of the original decoration specified by George Maher is preserved and the lavish decorative treatment is everywhere apparent on the interior.

Kathleen Cummings, National Historic Landmark Nomination, 1996

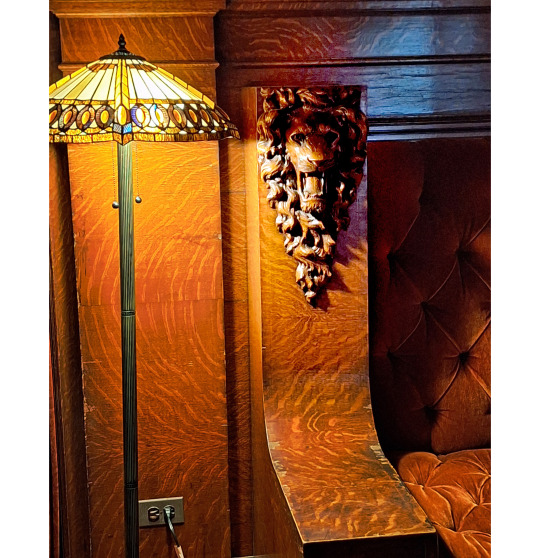

Detail of front porch support column

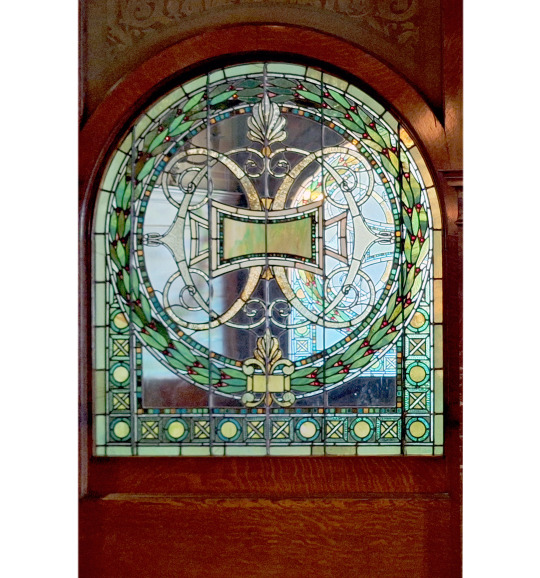

Stained glass entrance and flanking windows

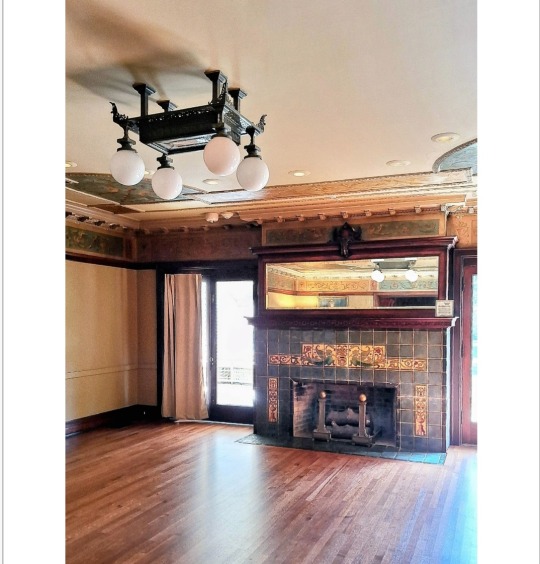

Entrance hall fireplace beneath Pleasant Home panel

Detail of lion head carving, repeated throughout the house, on entrance hall built-in bench

Carved screen in entry hall in front of the music room on the mezzanine

Stained glass entrance window

Reception room

Living room or sitting room

Dining room ceiling fixture

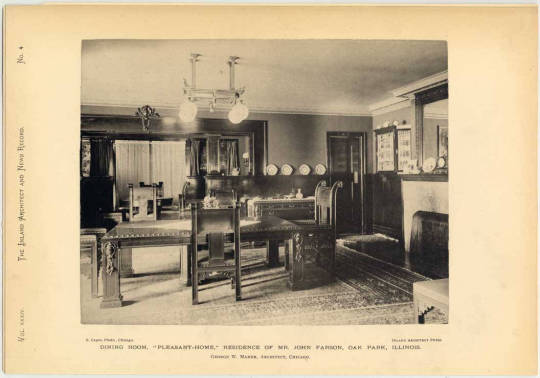

Dining room

Dining room corner, leading to summer dining room

Domed light fixture in the library

Library

Original Maher-designed dining table and chairs, now displayed on the second floor

The stunning original wall colors are seen in the above two photos of second-floor bedrooms

Vintage views of Pleasant Home, from the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago:

Left: George W. Maher and John W. Farson in the garden of Pleasant Home

Right: Entrance hall

Left: dining room Right: sitting room

The Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago, house a copy of the 1902 publication "Farson, John, Residence; Farson-Mills Pleasant Home." The publication contains many views of the house, exterior and interior.

Collection Call Number FF Special NA7239.M34 A65 1902.

Access the digitized copy at this link:

#Farson#house#Oak Park#Illinois#Pleasant Home#George W. Maher#Maher#architecture#chicago#photography#Prairie Style#residential

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 notes

·

View notes