#Nâzım Hikmet opere

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ti amo: l'amore universale e viscerale di Nâzım Hikmet. Recensione di Alessandria today

Un inno alla vita e ai sentimenti più autentici

Un inno alla vita e ai sentimenti più autentici La poesia “Ti amo” di Nâzım Hikmet è un capolavoro di lirismo e intensità emotiva, un viaggio nei meandri dell’amore vissuto come necessità e vitalità. Attraverso immagini semplici e potenti, il poeta turco riesce a trasformare l’esperienza intima dell’amore in un canto universale, capace di coinvolgere il lettore in ogni verso. Hikmet celebra…

#Alessandria today#amore e gratitudine#amore e necessità#amore e spiritualità#amore e vita#amore universale#amore viscerale#arte e poesia#celebrazione dell’amore#connessione globale#connessione umana#Crepuscolo#Emozioni#Emozioni profonde#Emozioni universali#Google News#gratitudine#gratitudine per la vita#Immagini Quotidiane#introspezione#Istanbul#italianewsmedia.com#letteratura turca#Lirismo#metafore quotidiane#Nâzım Hikmet#Nâzım Hikmet amore#Nâzım Hikmet biografia#Nâzım Hikmet opere#Pier Carlo Lava

0 notes

Photo

Posted @withregram • @la_setta_dei_poeti_estinti L’ULTIMA POESIA DI NÂZIM HIKMET. 📌02.02.2020, #Roma > Associazione @boncompagni22, ore 19 📍 Una serata all’insegna della poesia e delle opere di Nâzım Hikmet, poeta turco che ha lasciato al Novecento alcune tra le più intense liriche d’amore che siano mai state scritte. Dalle poesie più note come "il più bello dei mari", fino ai componimenti dedicati alla lontananza e all'esperienza del carcere, ripercorreremo insieme la vita e gli amori di una delle voci più significative del nostro tempo. Letture: Mara Sabia (attrice e docente) Emilio Fabio Torsello (giornalista e fondatore del circolo letterario "La Setta dei Poeti estinti") • • MODALITA' DI PARTECIPAZIONE: Serata a posti limitati, ingresso su prenotazione fino a esaurimento posti. Ingresso 10 euro + diritti di prevendita (1.50 euro). Biglietti solo online al link: https://bit.ly/36j4w2T (link nelle stories) Inizio letture: ore 19. L'ingresso è consentito dalle ore 18:30. Si raccomanda puntualità. La serata è organizzata dall'associazione culturale Boncompoagni 22, in collaborazione con il circolo letterario de La Setta dei Poeti estinti. Indirizzo: via Boncompagni 22, Roma #lasettadeipoetiestinti #boncompagni22 #hikmet #nazimhikmet #poesia #poesie #reading #lettura #libro #libri https://www.instagram.com/p/B75ol1LiXY9/?igshid=7sfqv6zgenb6

#roma#lasettadeipoetiestinti#boncompagni22#hikmet#nazimhikmet#poesia#poesie#reading#lettura#libro#libri

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Literature can save a life. Just one life at a time."

Teju Cole on carrying and being carried. Translation, refugees, new words.

New York Books, July 5, 2019

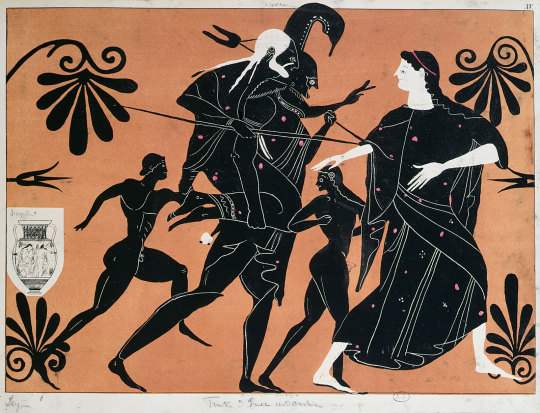

A reproduction of a scene from an ancient Greek vase depicting the flight from Troy, with Aeneas carrying his father Anchises on his back, nineteenth century

The English word translation comes from the Middle English, which originates from the Anglo-French translater. That in turn descends from the Latin translatus: trans, across or over, and latus, which is the past participle of ferre, to carry, related to the English word “ferry.” The translator, then, is the ferry operator, carrying meaning from words on that shore to words on this shore.

Every work of translation carries a text into the literature of another language. Fortunate to have had my work translated into many languages, I am now present as an author in the literature of each of those languages. Dany Laferrière, in his 2008 novel I Am a Japanese Writer, expresses this slightly strange notion more beautifully than I can:

When, years later I myself became a writer and was asked, “Are you a Haitian writer, a Caribbean writer or a Francophone writer?” I would always answer that I took the nationality of my reader, which means that when a Japanese reader reads my books, I immediately became a Japanese writer.

Much is found in translation. There’s the extraordinary pleasure of having readers in languages I don’t know. But there’s also the way translation makes visible some new aspect of the original text, some influence I didn’t realize it had absorbed. When I think about the Italian translation of my work, I can feel the presence of Italo Calvino and Primo Levi, unnerved and delighted that I mysteriously now share their readership. When I’m translated into Turkish, it is Nâzım Hikmet’s political melancholy I think of. Maybe those who like his work will, reading me in Turkish, find something to like in mine as well? In German, perhaps even more than English, I sense the hovering presences of writers who shaped my sensibility—writers like Walter Benjamin, Thomas Mann, Hermann Broch, and W.G. Sebald, among many others. Thanks to translation, I become a German writer.

I trust my translators utterly. Their task is to take my work to a new cohort of my true readers, the same way translation makes me a true reader of Wisława Szymborska, even though I know no Polish, and of Svetlana Alexievich, even though I know no Russian.

Gioia Guerzoni, who has translated four of my books into Italian so far, has worked hard to bring my prose into a polished but idiomatic Italian. Recently, she was translating an essay of mine, “On the Blackness of the Panther,” which ranged on various matters, from race, the color black, and colonialism, to panthers, the history of zoos, and Rainer Maria Rilke. It wasn’t an easy text to translate. In particular, the word “blackness” in my title was a challenge. To translate that word, Gioia considered nerezza or negritudine, both of which suggest “negritude.” But neither quite evoked the layered effect that “blackness” had in my original title. She needed a word that was about race but also about the color black. The word she was looking for couldn’t be oscurità (“darkness”), which went too far in the optical direction, omitting racial connotations. So she invented a word: nerità. Thus, the title became: “La nerità della pantera.” It worked. The word was taken up in reviews, and even adopted by a dictionary. It was a word Italian needed, and it was a word the Italian language—the Italian of Dante and Morante and Ferrante—received through my translator.

Translation, after all, is literary analysis mixed with sympathy, a matter for the brain as well as the heart. My German translator, Christine Richter-Nilsson, and I discussed the epigraph to my novel Open City, the very first line in the book. It reads, in English, “Death is a perfection of the eye.” The literal translation, the one Google Translate might serve up, would be something like “Tod ist eine Perfektion des Auges.” But Christine sensed that this rendering would equate “death” with “perfection of the eye,” rather than understanding that death was being proposed as the route to a kind of visionary fullness. So she first thought of “Vollendung,” which describes a finished state of fullness; then she thought further, and landed on “Vervollkommnung.” Vervollkommnung is a noun that embeds the verb “kommen,” and with that verb, the idea that something is changing and coming into a state of perfection. That was the word she needed.

Christine also knew that what I was calling the eye in my epigraph was not a physical organ (“das Auge”), it was the faculty of vision itself. But I didn’t write “seeing,” so “des Sehens” would not quite have worked. In conversation with my German editor, she decided on something that evoked both the organ and its ability: der Blick. So, after careful consideration, her translation of “Death is a perfection of the eye” was “Der Tod ist eine Vervollkommnung des Blickes.” And that was just the first sentence.

A young woman from Bonn named Pia Klemp is currently facing a long-drawn-out legal battle in Italy. Klemp, a former marine biologist, is accused of rescuing people in the Mediterranean in 2017. If the case comes to trial, as seems likely, she and nine others in the humanitarian group she works with face enormous fines or even up to twenty years in prison for aiding illegal immigration. (Klemp’s plight is strikingly similar to that of another young German woman, Carola Rackete, who was arrested in Italy this week for captaining another rescue boat.) Klemp is unrepentant. She knows that the law is not the highest calling. As captain of a converted fishing boat named Iuventa, she had rescued endangered vessels carrying migrants that had been launched from Libya. The precious human lives were ferried over to the Italian island of Lampedusa. The question Klemp and her colleagues pose is this: Do we believe that the people on those endangered boats on the Mediterranean are human in precisely the same way we are human?

When I visited Sicily a couple of years ago and watched a boat of rescued people with bewildered faces come to shore, there was only one possible answer to that question. And yet we are surrounded by commentary that tempts us to answer it wrongly, or that makes us think our comfort and convenience are more important than human life.

Because Pia Klemp’s holy labor takes place on water, it reminds me of an earlier struggle. In 1943, the Danes received word that the Nazis planned to deport Danish Jews. And so, surreptitiously, at great personal risk, the fishermen of north Zealand began to ferry small groups of Danish Jews across to neutral Sweden. This went on, every day, for three weeks, until more than 7,000 people, the majority of Denmark’s Jewish population, had been taken to safety.

Currently in my own country, hundreds of people die on the border in the name of national security. Children are separated from their parents and thrown in cages. A few years ago, I visited No Más Muertes (No More Deaths), a humanitarian organization in Arizona that provides aid to travelers by leaving water, blankets, and canned food at strategic points in the Sonoran Desert. These are activities that the US government has declared illegal. The organization also conducts searches for missing migrants, and often locates the bodies of those who have died of hunger or thirst in the desert.

A young geographer named Scott Warren, working with No Más Muertes and other groups, has sought to help travelers cross safely. He provides water and, when possible, shelter. For this holy labor, Warren was arrested and charged last year with harboring migrants. Although the case against him recently ended in a mistrial, the US Attorney’s Office in Arizona is seeking a retrial. Warren is far from the only No Más Muertes volunteer to have been arrested as part of the government’s war on those who offer life-saving help to our fellow citizens.

Can we draw a link between the intricate and often modest work of writers and translators, and the bold and costly actions of people like Pia Klemp and Scott Warren? Is the work of literature connected to the risks some people undertake to save others? I believe so—because acts of language can themselves be acts of courage, just as both literature and activism alert us to the arbitrary and essentially conventional nature of borders. I think of Edwidge Danticat’s words in her book Create Dangerously:

Somewhere, if not now, then maybe years in the future, a future that we may have yet to dream of, someone may risk his or her life to read us. Somewhere, if not now, then maybe years in the future, we may also save someone’s life.

And I think of a friend of mine, a filmmaker and professor from Turkey who signed a letter in 2016 condemning the slaughter of Kurds by the Turkish state and calling for a cessation of violence. She was one of more than 1,100 signatories from universities and colleges in Turkey. In response, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government initiated investigations of every Turkish signatory, accusing them all of terrorism. Most, my friend included, now face long trials and prison sentences. Many have been fired from their jobs or hounded by pro-government students. Some have already been jailed.

My friend and the other academics were carrying their fellow citizens. With the stroke of a pen, they attempted to carry them across the desert of indifference, over the waters of persecution. For this, they face consequences similar to those faced by Pia Klemp and Scott Warren: public disrepute, impoverishment, prison time. My friend finds herself in great danger for her stand, and so now it is her turn to be ferried to greater safety, because she did the right thing, and we must, too.

1 note

·

View note