#Mingus Big Band

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Chris Potter: A Modern Jazz Virtuoso Redefining the Saxophone

Introduction: In the world of jazz, there are those who follow tradition and those who push its boundaries to new heights. Chris Potter, an extraordinary saxophonist, composer, and bandleader, falls into the latter category. With his technical brilliance, harmonic sophistication, and an unrelenting quest for innovation, Potter has earned a reputation as one of the most influential voices in…

#Adam Rogers#Antonio Sánchez#Ben Williams#Chris Potter#Chris Potter Underground Orchestra#Craig Taborn#Dave Holland#Dave Holland Quintet#Follow the Red Line: Live at the Village Vanguard#Gratitude#Imaginary Cities#Jazz History#Jazz Saxophonists#Joanne Brackeen#John Coltrane#Johnny Helms#Mingus Big Band#Nate Smith#Not for Nothin&039;#Pat Metheny#Paul Desmond#Paul Motian#Pink Elephant Magic#Presenting Chris Potter#Prime Directive#Red Rodney#Sonny Rollins#Terry Rosen#The Dreamer Is the Dream#Underground

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

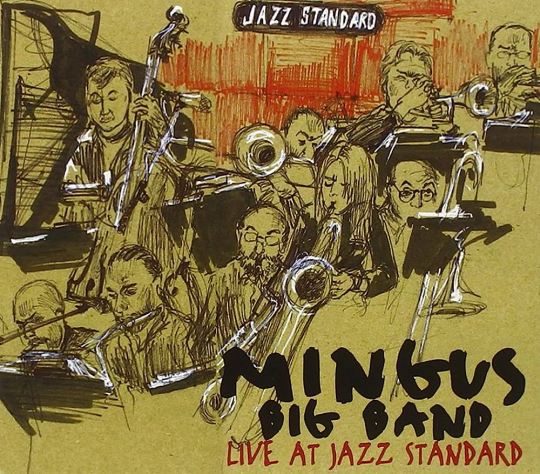

Storia Di Musica #281 - Mingus Big Band, Live At Jazz Standard, 2010

Chi e cosa è stato Charles Mingus? Le domande non sono così tautologiche come possono apparire. Nella storia dei grandi del jazz, porta agli estremi la ribellione culturale, l’esigenza di una riabilitazione personale, i problemi psichiatrici, una vitalità che molto spesso superava ogni eccesso nel cibo, nel sesso, nell’esternazione delle emozioni. Ma sopra ogni cosa Mingus è stato un genio creativo con pochi pari. Il burbero, scontroso, violento passa in secondo piano rispetto al musicista. È quello che successe poco dopo la morte, avvenuta nel gennaio del 1979: molti dei musicisti che avevano collaborato con lui, si strinsero intorno alla figura di Sue Mingus, la sua quarta moglie, e iniziarono a pensare a come omaggiare la sua musica. Tra l’altro, nonostante la debilitante malattia che lo stava progressivamente fermando, Mingus continuò a comporre e dettare musica, tanto che alla sua morte lasciò in eredità almeno 200 idee musicali tra spartiti, linee melodiche, idee sparse qua e là. Nello stesso anno della morte, si forma il primo nucleo di questo percorso di ricordo con la Mingus Dynasty, formata dai sessionisti che collaborarono con lui nell’ultimo periodo. Iniziarono a suonare concerti in giro per gli Stati Uniti prima, e nel mondo poi, garantendo a Mingus una nuova fioritura di notorietà, persino più sincera e ragionata rispetto a quella legata al suo strabordante personaggio. Sue costituirà una Fondazione, che oltre a celebrare la musica di Mingus, diventerà attiva nella formazione musicale e culturale, garantendo borse di studio ai ragazzi emarginati, legando il tutto ad uno dei punti centrali della parabola artistica di Mingus: il rispetto interrazziale e l’importanza della conoscenza per le minoranze etniche. Mingus Dynasty prende il nome dal titolo di un album del 1959, Mingus Dynasty, che contiene due classici mingusiani, Song With Orange ma soprattutto Gunslinging Bird, che stavolta fu davvero dedicata al grande Parker, e come titolo provvisorio aveva If Charlie Parker Were a Gunslinger, There'd Be a Whole Lot of Dead Copycats. Nell’album del 1959 al trombone c’era Jimmy Knepper, all’epoca fido collaboratore di Mingus, che nonostante i due denti rotti che gli fece il Maestro e il conseguente processo, rimase sempre un suo grande amico. E Knepper fu il band leader di uno dei grandi live che la Dynasty ebbe presso il Teatro Boulogne-Billancourt di Parigi, l’8 Giugno 1988, racchiusi in due emozionanti cd (titolo Live at the Theatre Boulogne-Billancourt/Paris, Vol. 1 e 2). Ma personalmente credo che il ricordo più vero e sentito è stato quello che ha portato avanti l’evoluzione della Dynasty, la Mingus Big Band. Uno dei sogni di Mingus era di creare una Big Band sulla falsariga di quelle del suo mito Duke Ellington, e un po’ come successe allo stesso Ellington, a Glenn Miller o ai fratelli Tommy e Jimmy Dorsey, le cui musiche sono sopravvissute al loro creatori anche grazie alla continuazione delle big band, così è capitato pure indirettamente per Mingus. La Mingus Big band nasce nel 1991, formata da 14 elementi: il repertorio mingusiano viene riarrangiato, anche seguendo delle idee di Charles, in stile Big Band, che rimase il grande sogno inespresso in vita del grande contrabbassista. Il successo delle prime esibizioni è esaltante, e in pochi anni la Mingus Big band suona in tutti gli Stati Uniti d’America, e inizia anche acclamatissimi concerti in Europa, in Giappone, in Oceania. Nel 1997, viene ingaggiata per l’apertura di un nuovo locale, il Jazz Standard, situato nel quartiere Rose Hill di Manhattan, New York City. La band viene ingaggiata per due lunedì di seguito, ma il successo dei Mingus Mondays diviene così eccezionale che in pratica la band suona, quando non è in tour, tutti i lunedi fino a quando, causa Covid, il locale non chiude nel 2020. Ma la sera del 31 dicembre 2009, casualmente non un lunedì ma un giovedì, Sue Mingus decide di registrare l’esibizione della Big Band, e pochi mesi più tardi esce Live At Jazz Standard, nell’aprile del 2010. Quella sera fa parte della Big Band anche Randy Brecker alla tromba, che agli inizi degli anni ‘70 fu sessionista prediletto di Mingus. In scaletta, il meglio della produzione: Self-Portrait in Three Colors, Bird Calls, Open Letter To Duke, Cryin' Blues, la leggendaria Goodbye Porky Pie Hat, ma anche scelte minori come E's Flat Ah's Flat Too (aka "Hora Decubitus"), da Blues & Roots del 1959, New Now Know How e una finale Song With Orange da antologia. Band, pubblico, atmosfera sono così perfetti che il disco vince un Grammy Award come Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album nel 2011, e i Mingus Mondays sono ormai uno dei 5 eventi jazz migliori di tutta New York per i primi due decenni degli anni duemila. La Big Band continua a suonare in tutto il mondo, anche in Italia dove ha un folto seguito di appassionati, e quest’anno i Mingus Mondays sono tornati presso il Drom, un altro locale di New York, nell’East Village. Per celebrare il centenario della nascita di questo genio, pazzo e scalmanato, e davvero unico. Persino nella storia del jazz.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mingus Big Band

@ Yoshi's, SF

went up with some band people, don't remember a ton but it would have been a good performance

added 9/26/2023

1 note

·

View note

Text

they will open the file for my dissertation only to find an mp4 for The Maid We Messed by Matt Elliott (and it's unskippable)

#the theme song fr#also gleis by flako and moanin' by mingus big band . mirror by grace ives . wreaths rakes by stolen jars somehow? navy light labyrinth ear#a tune for us DjRU + many more . but the maid we messed truly captures the vibe

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

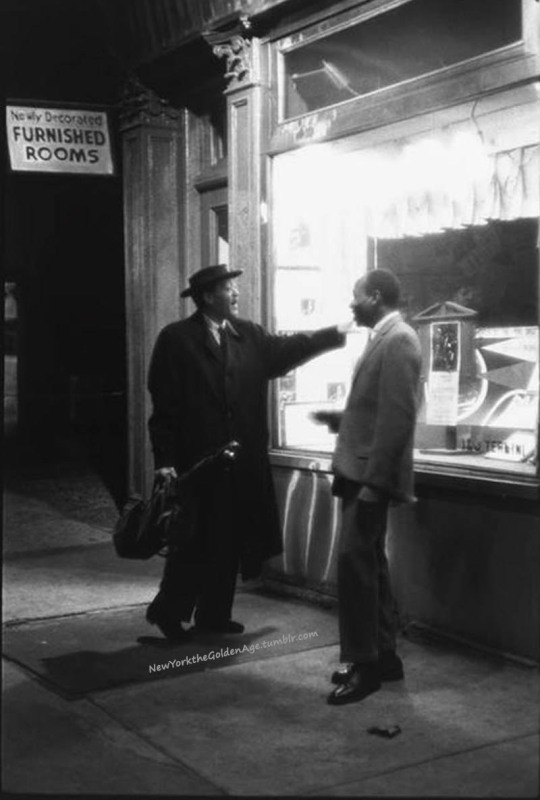

"Goodbye, Pork Pie Hat."

youtube

Lester Young outside the Five Spot Jazz Club, the Bowery, 1958.

The first jazz musician I ever photographed, Lester Young performing at The Five Spot Café, on the Bowery, 1958. Now here was a quiet soul, someone who let his music speak for him. I took this shot outside before the show, Lester being greeted by an unknown admirer or so I believe. I've never been able to identify this person. The famous pork pie hat at a slight—and cool—angle.

—Herb Snitzer

Photo: Herb Snitzer

#youtube#jazz#jazz music#music#prez#lester young#charles mingus#jazz big band#big band#goodbye pork pie hat

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA TO EVERYONE

this is my official request that you all listen to Don’t Let It Happen Here by Charles Mingus

0 notes

Text

An extremely dumb guid to “Which famous 60’s/70's Jazz man is that?”

1, Is it Piano lead or Brass lead? If piano go to question two. If brass question three.

2, Does the Pianist sound like he’s taken all the acid, or is there a guy making love to a clarinet?

Oh yeah: he’s taken all the acid alight. Is… is he okay? Thelonious Monk.

Oh yeah, some guy is going ham on a clarinet. Dave Burkbeck Quartet.

Neither of the above: Duke Ellington.

3, If brass lead: is it Louis Armstrong? If Yes, it’s Louis Armstrong. If no, question four.

4, Does the Trumpet player make you feel sad? Even, dare I say, Blue?

Almost? Chet Barker

Kind of? Miles Davies.

If no, question five.

5, Is the trumpet player trying to blow your face clean off? Like, actively trying to kill the first row of the audience? Dizzy Gillespie.

It’s brass led, but Sax not Trumpet.

Okay, technically thats a woodwind but moving on, question 6, isolate the stings: is Charles Mingus doing what he’s actually paid to do in the back of the ensemble, or is he dicking around and seeing how far a man can take a double bass before his band-mates kill him?

Seems to be playing normally: Charlie Parker

He’s fucking around in F minor, and also that Bari sax is filthy! The Mingus Big band, with Ronnie Cuber on the Sax.

#Jazz#Big bang#blues#thelonious monk#dave brubeck#duke ellington#louis armstrong#chet baker#miles davis#dizzy gillespie#charlie parker#charles mingus#Ronnie Cuber#Tell me who i missed and how wrong i am in the comments#God i love Jazz

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry for the spam likes today. Favorite jazz album?? I saw a post on your blog that mentioned Mingus ah um. That’s either my fave or Birth of Cool (Miles Davis does do my favorite version of On Green Dolphin Street). Though both are kinda basic choices I want to expand my listening.

so i'm gonna give you a few albums (and album-adjacent things) with the caveat that i haven't heard most of what's out there ^_^ i'm just a casual fan

ornette coleman - the shape of jazz to come

this album is on another level. the multiple layers of brass crisscross each other, playing dissonant chaos, then they rip into solos that could melt charlie parker's fingers. the bass shreds and stumbles up and down some wild assortment of scales. the drums patter out a frantic rhythm that somehow ties everything together.

it shouldn't make sense, but it feels so alive. you'll catch quotes from flight of the bumblebee over rainy oceans of rhythm. herds of wild animals shuffle back and forth in a forest painted by jackson pollock. and then whoever's not soloing yells "woo! alright!"

it's not even my favorite ornette coleman recording. that honor goes to this youtube upload of a live show in germany, 1978. the bass intro, instantly picked up by the drummer, is so electric. the haunting melodies, borrowed from the rite of spring, are traded from sax to guitar. the whole band feels like they're operating on instinct. this is what a basquiat painting SOUNDS like. like a genius artist drawing with their non-dominant hand. LITERALLY coleman plays a violin left-handed at one point. it's incredible.

john coltrane - my favorite things

trane puts so much panache into this simple little pop song. the opening chords are heavy with drama. the groove is insanely tight. every time he plays the melody, it's got a new rhythm, to the point where he seems to be playing a game with the listener. "how many ways can i get you to feel this groove?" the song is melted, bent, and stretched like molten glass, in a 13 minute display of total virtuosity

and that's just track 1!!!! this album is timeless. every second is as fresh and vibrant as it was in 1961

herbie hancock - headhunters

herbie has always been at the cutting edge of jazz fusion. this is his definitive statement on funk

this album is intensely rhythmic, laying out catchy melodies over funk foundations. the whole band seems to just be having a blast. the grooves are often busy and hypermelodic, with no room to breathe as everyone jams at once. it's like an all-night house party in a bouncy castle full of confetti

if you're a fan of japanese jazz like caseopia, or jazz-influenced video game music, this album will feel shockingly familiar to you. its wildly creative synth work, uplifting and colorful chords, and eclectic sound palette are all DECADES ahead of their time.

where would we be without herbie? i'd wager the entire global music landscape would be different. from hip hop to big beat to drum n bass, we all stand on the shoulders of giants. hancock is a titan. the giants that raise us up are standing on his shoulders

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

VHS'S Back, Baby!

Pardon my bad animating 😭 (song: Moanin' by Mingus Big Band)

Finally, after A MONTH of figuring out some stuff, I think it’s safe to say that I am officially back!

Still struggling with personal things, but yeah, I’ll still be here, not often cause I got school and I don’t wanna be chronically online 😭

But hey, your ol’ VHS is back again, and they’re (I’m) coming back with new art, reblogs...YOU NAME IT!

But then again, I’ll try my best not to go on Tumblr for a long time, I gotta keep myself in check. So the amount of posts I’ll make will be shorter than usual, but otherwise, it’ll depend.

Anyways, I hope you’re glad to have me back! <3

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

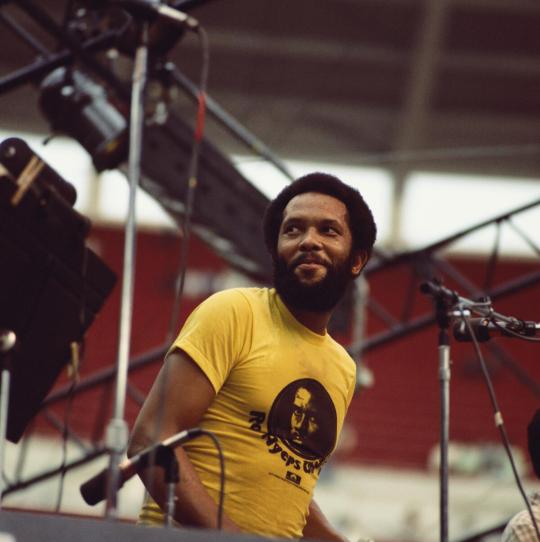

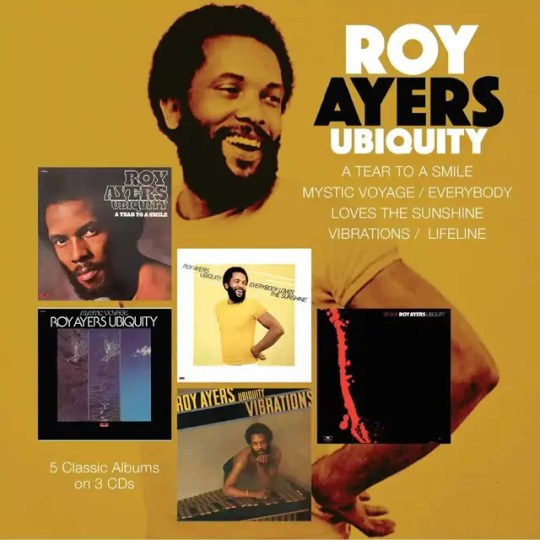

Roy Ayers

Jazz-soul vibraphonist and band leader best known for his laid-back summer track Everybody Loves the Sunshine

When Ruby Ayers, a piano teacher, took her five-year-old son Roy to a concert by the Lionel Hampton Big Band in California in 1945, the boy showed so much enthusiasm for the performance that Hampton presented him with his pair of vibe mallets. Roy Ayers, who has died aged 84, would go on to blaze a trail as a vibraphonist, composer, singer and producer.

A genre-bending pioneer of hard bop, funk, neo-soul and acid jazz, Ayers was most famous for his feel-good track Everybody Loves the Sunshine, from the 1976 album of the same name.

He said that the song was recorded at Electric Lady Studios in New York on, naturally, a warm summer’s day. Among those who feature are Debbie Darby (credited as “Chicas”) on vocals and Philip Woo on piano, electric piano and synthesizer. Woo explained that Ayers did not like to work from charts or scores, with the song based around a single chord that the band in the studio then developed.

While it was never released as a single, Everybody Loves the Sunshine’s warm, jazz-soul sound has won it numerous admirers over the past 50 years. As well as being sampled hundreds of times, by artists including Dr Dre and Mary J Blige, the track has also been covered by musicians ranging from D’Angelo to Jamie Cullen.

Perhaps the sheer simplicity of the song’s structure explains its appeal to such a variety of musicians. The hazy chords set up a steady state condition that allows the performer room for manoeuvre. D’Angelo covered the song in sweaty desire; Cullen’s Live in Ibiza version is as light and moreish as your favourite ice-cream; the Robert Glasper Experiment cover is edgy, an exercise in deconstruction. Other notable versions include the electronica-infused track from the DJ Cam Quartet and the modern jazz take of trumpeter Takuya Kuroda.

Ayers was born in the South Park (later South Central) district of Los Angeles, and grew up on Vermont Avenue amid the widely admired Central Avenue jazz scene during the 1940s and 50s, which attracted luminaries such as Eric Dolphy and Charles Mingus. His father, Roy Ayers Sr, worked as a parking attendant and played the trombone. His mother, Ruby, was a piano player and teacher.

He attended Thomas Jefferson high school, sang in the church choir, and played steel guitar and piano in a local band called the Latin Lyrics. He studied music theory at Los Angeles City College, but left before completing his studies to tour as a vibraphone – or vibes – sideman.

His first album, West Coast Vibes (1963), was produced by the British jazz musician and journalist Leonard Feather. He then teamed up with the flautist Herbie Mann, who produced the “groove” based sound of Virgo Vibes (1967) and Stoned Soul Picnic (1968).

Relocating to New York at the start of the 1970s, Ayers formed the jazz-funk ensemble Roy Ayers Ubiquity, recruiting a roster of around 14 musicians. At this time he composed and performed the soundtrack for the blaxploitation film Coffy (1973), starring Pam Grier as a vigilante nurse. The Everybody Loves the Sunshine album was released under the Ubiquity rubric, reaching No 51 on the US Billboard charts, but making no impact on the UK charts.

His 1978 single Get On Up, Get On Down, however, reached No 41 in the UK. He also scored chart success with Don’t Stop the Feeling (1979), which got to No 32 on the US RnB chart and 56 in the UK. The track was featured on the album No Stranger to Love, whose title track was sampled separately by MF Doom and Jill Scott.

Ayers was a regular performer at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in London during the 80s and his shows there were captured on live albums. Other live recordings include Live at the Montreux Jazz Festival (1972) and Live from West Port Jazz Festival Hamburg (1999). Ayers played at the Glastonbury festival five times, with his last appearance there in 2019.

A tour of Nigeria with Fela Kuti in 1979, and a resulting album, Music of Many Colours (1980), was just one of many fruitful collaborations. Ayers also performed on Whitney Houston’s Love Will Save the Day (1988); with Rick James on Double Trouble (1992); and with Tyler, the Creator on Cherry Bomb (2015).

A soul-funk album, Roy Ayers JID002 (2020), was the brainchild of the producers Adrian Younge and Ali Shaheed Muhammad. The latter was a member of the hip-hop group A Tribe Called Quest, who had sampled Ayers’ Running Away on their track Descriptions of a Fool (1989), and Roy Ayers Ubiquity’s 1974 song Feel Like Makin’ Love on Keep It Rollin’, from their 1993 Midnight Marauders album.

Ayers also collaborated with Erykah Badu on the singer’s second album, Mama’s Gun (2000). The pair recorded a new version of Everybody Loves the Sunshine for what would be Ayers’ final studio album, Mahogany Vibe (2004).

“If I didn’t have music I wouldn’t even want to be here,” Ayers told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s like an escape when there is no escape.”

Ayers married Argerie in 1973. She survives him, as do their children, Mtume and Ayana, a son, Nabil, from a relationship with Louise Braufman, and a granddaughter.

🔔 Roy Edward Ayers Jr, musician and band leader, born 10 September 1940; died 4 March 2025

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

you know that fic my friend wrote based off a Oswald is a Arkham doctor and Edward the patient au?

I’m trying to list every inspiration even if we only saw these works in essays or not fully and.

this is genuine neurosis THERES 30 WORKS AND WE GO FROM MOANIN BY MINGUS BIG BAND TO BLAIRE WHITE AND JK ROWLING BECOMING THE FASCIST?

bro.

yes two Alfred Hitchcock movies are here too SHUT UP

#Rambles#Gotham#nygmobblepot#Gotham au#adotn#WERE ACTUALLY GETTING CLOSER TO PUTTING SOME CHAPTERS OUT SINCE WE ARE LESS INSECURE ABOUT OUR WORK SO#YAYYYYYY#writings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

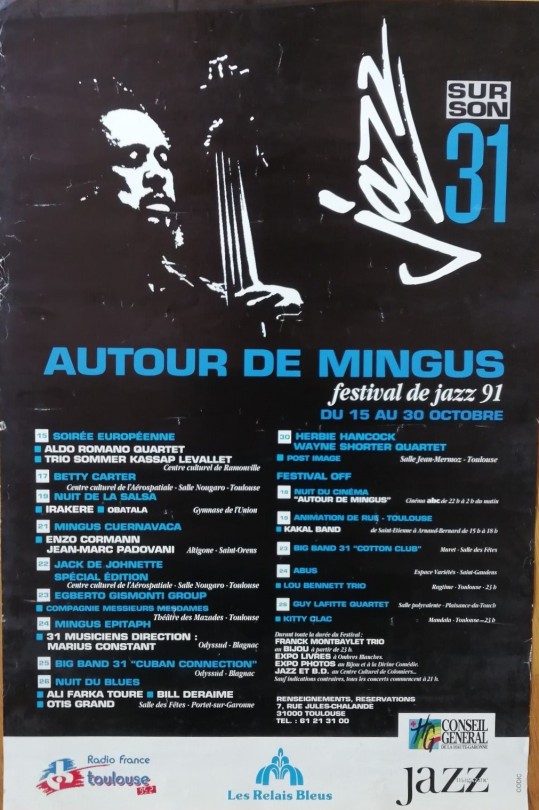

1991 - Jazz sur son 31 - Autour de Mingus - Toulouse (and surrounding towns)

Aldo Romano, Betty Carter, Irakere, Jack DeJohnette Special Edition, Mingus Epitaph, Big Band 31, Herbie Hancock & Wayne Shorter Quartet, Lou Bennett trio, Guy Lafitte Quartet, ...

#jazz#poster flyer#1991#betty carter#irakere#jack dejohnette#herbie hancock#wayne shorter#lou bennett#guy lafitte

12 notes

·

View notes