#Maximum Horsepower

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Here's a little something eclectic: some obscure and less popular Disney characters. How many can you recognize?

Horace Horsecollar, specifically his incarnation from the never-made TV series Maximum Horsepower. This series was proposed in the 90s for the Disney Afternoon, but was never greenlit. It's too bad; I think it would have been a really fun series. Here's the original pitch reel by Tad Stones (creator of Darkwing Duck).

Gopher, from Winnie the Pooh. Prior to his cameo in 2023's Once Upon a Studio, Gopher's last animated appearance was in 2005 in Pooh's Heffalump Halloween Movie (and even then, it was only archive footage from 1996's Boo to You Too!). Gopher's only other appearances were in the Kingdom Hearts games. I'm not sure why Disney used him less and less, but it's nice to see he wasn't entirely forgotten.

Stinky Pete (The Prospector) from Toy Story 2. Pete was never exactly my favorite character as a kid, but some time ago I heard that there was an old character interview where Pete claims that he's happy with his new owner Amy, and really enjoys her decorating his face. I think it's the most adorable thing ever and I'm glad I finally got around to drawing it. (I've tried to find this interview, and I could have sworn I saw it years and years ago, but the only one I can find is this one where he's his child-hating self from the movie.)

Gurgi, from The Black Cauldron. I loved him as a kid, and that feeling never went away as I grew up. He is a brave and loyal friend and deserves all the munchies and crunchies in the world.

Buzzy, from the former EPCOT attraction Cranium Command. I unfortunately never got to experience this attraction (or even EPCOT in its prime). The attraction closed in 2007, and sat abandoned for years. The animatronic of Buzzy was reported missing in 2018, with little explanation of what happened to him. Here's a couple of fun videos on the subject. #JusticeForBuzzy

Terry and Keiko (the video chat friends) from the 1994 Jeremy Irons iteration of Spaceship Earth in EPCOT. I don't expect many people to recognize these characters, as they were removed in 2007. They weren't even moving animatronics, just still figures. But I think their friendship is super adorable, and it's neat to imagine technology that can instantly and accurately translate your dialogue into a foreign language. You can see Terry and Keiko here (at 12:23).

#horace horsecollar#maximum horsepower#gopher#stinky pete#gurgi#epcot#cranium command#spaceship earth#disney parks#disney100

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you all remember this post I made about there being a tv show for Mickey, I was planning on adding characters to fill out the supporting cast.

I do have OCs planned out once I figure out a name and how to draw them, but I'm also going to borrow some characters, mainly those who appeared once or just appear in the comics.

Stacey

Attends Mouseton School of Business (same college Zan Owlson went to)

Helps out at Felicity's food truck business.

I really want Jane (the waitress at Funso's Fun Zone) to be her roommate. I mean she did say she wanted to go college and to get out of Duckburg (someone please consider drawing this!)

Chief O'Hara

Private Investigators often work with the police, so I imagine he and Mickey would have an amicable relationship where O'Hara would go to Mickey sometimes for help on a difficult case.

Gloomy the Mechanic

I have this OC that is a mongoose and Mickey's reluctant pilot, but I couldn't decide if I wanted him to also be the main mechanic to fix up the plane so that's where Gloomy comes in.

Took up the position as mechanic after Mickey and my OC swiped and later kept this plane they came across while working for a client.

Gideon

I'm choosing the first option I had for him.

Since he's not really supposed to Gideon McDuck here, I guess I can't use the name County Conscience for the name of his newspaper.

I mentioned that Minnie was a freelance journalist so she would write a couple of pieces for their newspaper.

Okay so the characters I have listed here are more like minor or background characters:

Crash Happies

The Crash Happies would be an indie band that actually exists.

Horace Horsecollar & Clarabelle Cow

Horace and Clarabelle are part of the cast too, but they only appear as TV characters for the in-universe sci-fi adventure series Maximum Horsepower (based off of the unproduced Disney series by Tad Stones).

For the show, I always thought of it as a combination of Buzz Lightyear of Star Command and Guardians of the Galaxy.

They do not know who Mickey is.

#mickey and friends#a goofy movie#stacey#a goofy movie stacey#chief o'hara#gloomy the mechanic#duckverse#gideon mcduck (sort of)#ducktales#ducktales 2017#the crash happies#horace horsecollar#clarabelle cow#maximum horsepower#disney

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Funny story about this WIP, I was already asleep for about an hour. Out of nowhere I woke up wide eyed and grabbed my iPad to sketch this. Only to knock out right after like nothing happened. Anyways a new Maximum Horsepower WIP. :3

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horace Horsecollar in the unproduced Disney Afternoon series, Maximum Horsepower.

These shots are from a pitch reel video made by Darkwing Duck creator Tad Stones.

Huge apologies for the poor quality and super tiny screenshots, that's just how the video is. The video was uploaded on Tad Stones' Twitter and Facebook accounts in 2017.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bicycles kick a lot of ass these days. When I was a kid, a bicycle would only go as fast as you could pedal. Maybe, if you were really a huge asshole, you could take the bus to the big city and buy one of those mini-moped kits from a motorcycle shop. Then you could break playground-zone speed limits with enough two-stroke burble and pop to arouse every police officer within thirty miles.

Nowadays, you can slap some Chinese-made wonder magic on your Norco and do three or four horsepower without even knowing how to solder. In fact, it's much better if you don't know anything about electronics, because that level of knowledge will prevent you from extracting the maximum value out of your investment of "some vape batteries" and "a motor I found on Amazon whose name YouTube can't consistently pronounce." Electrical engineers are just too damn afraid of fire to go really fast.

Sure, you have to show fealty to the all-knowing microcontroller inside the magic motor box. Pinky-swear to it that you live in the hypothetical lawless wonderland that would allow you to have this much wheel-bending, mind-melting torque on a public pedestrian pathway. Honestly, it's its own fault if it believes a shifty character such as yourself. Not that the local cops are going to pull over Bob Tongsheng on his way to deposit your money in his bank, either. It's this kind of primitive hot-rodding that once made this country great: neglecting the existence or worth of anyone and everything outside of your vehicle in lieu of Go Fast.

Sure, this sort of thing will only last for awhile. Pathways are already filling up with lots of zingy e-mopeds and e-deathscoots, ridden by perfectly normal people. Your 1500-watt stealth bomber build is going to get pulled on by a pensioner within a year or two, as the market begins to demand enough cargo room (and rollover protection!) to do a once-a-month Costco run with the entire fam in tow. Inevitably, the cops are going to have to crack down on the whole deal, too.

For a glorious, shining moment, you too can dig a rusty mountain bike out of a creek and have it doing 50 miles an hour by watching a YouTube video. That's something previous generations simply could not have imagined. Which is their loss, really. If they had gotten off their asses earlier and figured out the lithium-ion battery, we could all be driving $100 50-horsepower ebikes right now instead of having to pay Big Battery for the "latest and greatest" in burning your garage down.

247 notes

·

View notes

Note

bucket of facts here. This is one of my favorite f1 things ever, apologies for how long it ended up being:

In the 1980’s, formula one teams, notably BMW, added toluene to their fuel mixtures. If that word sounds like it’s probably dangerous, that’s because it is — most people know it as rocket fuel. It’s extremely poisonous and carcinogenic, but did have some upsides! For one, it was less volatile [citation needed] than what they had been using, making is slightly less dangerous in the event of a crash (by 1970’s-80’s F1 standards that just means in only turned into a small bomb most of the time). It was also denser and burned faster, so the same amount of toluene could give much more power than the standard F1 fuel.

While the new fuel did allow them to run higher turbo pressures, it did it have a tendency to increase turbo pressure as it was run during the race, and everyone ran turbos at this time. They had to dial back the turbo pressure from what it’s max could’ve been, just to compensate for the power of the fuel — this mitigated the admittedly high likelihood that the engine decided to submit its two weeks notice on two seconds of warning (read: it caught on fire and sometimes kinda maybe sorta just exploded).

Modern f1 fuel has an RON octane rating of 95-102. The toluene aided fuel had an RON octane rating of 120+. For context, your car probably runs on about 87 RON. For those unfamiliar, RON octane ratings measure how much compression fuel can be put under before it sparks, which is how engines work: compress fuel, spark, make power (I can explain that better if you want but short version is that). This incredibly high octane level allowed the engines of the time to be run at a much higher compression, which had a myriad of bonuses to the cars.

Current F1 regulations are 1.6 litre V6 engines that rev to 15,000 RPMs (max allowed) and produce a max of 850 BHP (horsepower) when they’re pushing the edge of their abilities without aid of electric components like H/KERS, which is used to boost the cars to around 1,000 BHP.

Brabham-BMW’s 1983 engine took Nelson Pique to his WDC that year. It was a 1.5 litre inline 4 (so smaller than current) and produced 12,000 RPMs, as the restrictions were a bit tighter there back then. Without electronic aid like today and a smaller engine than your standard Toyota Camry, it easily produced 850 BHP at race trim, the version built to last a whole race. When in qualifying trim, with everything tuned to maximum to get the most out of the car without it blowing up, it ran at 1,250 BHP. Original testing put it at producing over 1,400 BHP, but BMWs testing facilities couldn’t measure past that — the car put out more power than they could even register.

The teams also had a sneaky loophole: the amount of fuel allowed to be held at once in the car (refueling was banned at this time) was effectively limited to how large the gas tank could be. The teams realized that they could literally freeze the fuel and store it at cold temperatures. This compacted the fuel, allowing them to put more fuel into the gas tank — more fuel per fuel, really. This allowed drivers to be more aggressive and push harder more often, not having to worry about running out of fuel.

In case this whole toluene thing seems bad, don’t worry! It’s only used in nail polish, rubber, adhesives, and paints :3

hit me up for more facts if you want

oh my

anon bestie i might in fact be in love with you

#u definitely delivered with your fact this is so fucking silly#f1: exploiting loophole since the beginning of time#not a tag#from saph#f1#pls send facts whenever u please this is wonderful

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

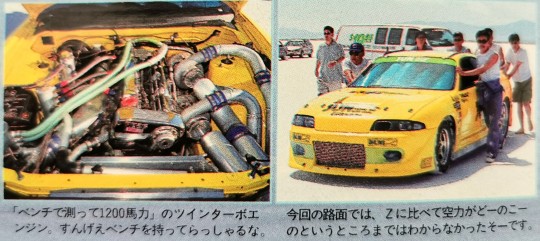

JUN R33 Skyline GTR at Bonneville.

JUN Suka did it 375km/h!

49th Bonneville Speed Week

Enjoying the pleasure on the salt was Susumu Koyama, managing director and driver of JUN Auto Mechanics. A new record was a given, and with the goal of beating the 260 miles set six years ago with a 300ZX, he brought his 1,200 horsepower R33 Skyline GT-R, which he started building in May. The fastest challenge on Lake Bonneville, Utah, USA will be held for one week starting August 16th. As expected, the GT-R broke the class record with an average speed of 233.217 miles per hour. Photos&Report/Shogo NAKAO ●Interview cooperation/Travel Alice 06-341-1201

JUN is Bonneville's home run king.

When he first came here in 1990, he failed with a 300ZX, but the following year he used the same machine to hit a bullet liner of 260.809 mph and 419 km/h. In 1993, I brought an R32GT-R, but it rained.

The tournament was canceled due to standing water. Moving to Dry Lake in El Mirage, California, he set a class record of 194.961 mph and 313 km/h on a 2 km straight short course.

The aim this time is F/BGCC class. In the blown gas competition coupe, supercharged gasoline engine category below 3L, the previous record of 219.107mp/h was set by Thunderbird last year. First of all, Managing Director Koyama. The road surface was extremely rough due to the previous week's thunderstorm.

Even though I said, "I won't run straight," I ran 221 miles. Qualify now.

Normally, after this, I would run the 7-mile course in reverse and record the average value of the two runs, but on the evening of August 17th, when I qualified, it rained heavily and the course was closed until the afternoon of the 19th.

The rainwater did not dry up after the 3rd mile mark, making it an unusual record run in the same direction for 223 miles. At this point, I have achieved a class record. ``When I was a sophomore, there wasn't a big bench.

It was estimated that it had 1000 horsepower. This time, we have 1,200 horsepower, so according to calculations we should be able to cover over 260 miles,'' said Mr. Yoshida, the JUN public relations officer, with a red-hot face.

``The car was bouncing around so much,'' he says, so he loaded eight 18-kilogram salt bags into the trunk, for a total of 144 kg, aiming for even more speed.

However, the rain on the 17th did not dry up quickly and there were sloppy and slippery conditions.

Daijiro Inada, who is well-known for OPT magazine, rides the boat and pulls it an average of 233 miles.

On the second and final day, Managing Director Koyama aimed for a homer with the bases loaded by removing the salt bags and using thicker tires and maximum boost pressure, but he could not beat Daijiro.

I ended up spinning around in circles.

The members of JUN looked a little disappointed.

PIC CAPTIONS

The weight of the vehicle is 1500kg. It had been converted from a 4WD to a 2WD, but apparently ``a 4WD would have been better on this road surface.''

Traction was improved by placing 144 kg of salt bags next to the gas tank in the trunk.

A twin-turbo engine with 1200 horsepower measured on the bench. Great, you have a bench.

On the road this time, he was not able to tell how the aerodynamics were compared to the Z.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeep Wrangler Magneto 3.0 Concept, 2023. An update of previous Magneto concepts, this one offers three driver selectable functions that capitalise on the benefits of a fully electric powertrain in off-road situations:

Output select allows the driver to choose between two power settings (standard: 285 horsepower/273 lb.-ft. of torque; maximum: 650 horsepower/900 lb.-ft. of torque)

Two-stage power regeneration mode allows normal driving while off, or enhanced brake regeneration using the electric motor when engaged

Aggressive hill descent mode can be selected in low range to offer true ‘one pedal’ off-road driving in serious rock-crawling situations

#Jeep#Jeep Wrangler Magneto 3.0 Concept#concept#EV#electric off roader#prototype#design study#2023#Jeep Easter Safari#Easter Jeep Safari#Jeep Wrangler

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

The A-12 Engines

The J58 turbojet engines that would enable the A-12 to fly so high and fast were the most persistent problem. Designed in 1956 for a Navy aviation project that was canceled, the engines had to undergo major modifications to turn them into the most powerful air- breathing propulsion devices ever made. Just one J58 had to produce as much power as all four of the Queen Mary’s huge turbines—160,000 horsepower or over 32,000 pounds of thrust. To crank it up, two Buick (later, Chevrolet) racecar engines on a special cart were used. The unmuffled, big block engines put out over 600 horsepower and made a deafening roar. The J58s themselves put out an almost incredible din. Recalling his visit to the test site to watch a midnight takeoff, DCI Richard Helms wrote that “[t]he blast of flame that sent the black, insect- shaped projectile hurtling across the tarmac made me duck instinctively. It was if the Devil himself were blasting his way straight from Hell.”5

As with so much else on the A-12, getting the engines to work at design specifications posed never-before-encountered troubles with fabrication, materials technology, and testing. Not the least of them was the superhot conditions. Maximum fuel temperatures reached 700 degrees F.; engine inlet temperatures climbed to over 800; lubricants ranged from 700 to 1,000; and turbine inlets reach 2,000 degrees F. and above. A Pratt & Whitney engineer later wrote that “I do not know of a single part, down to the last cotter key, that could be made from the same materials as used on previous engines.”6

Pratt & Whitney’s continuing difficulties with the weight, performance, and delivery of the J58 forced delays in the completion of the first A-12. After meeting with the manufacturer in early January 1962, Johnson noted in his log that

[t]heir troubles are desperate. It is almost unbelievable that they could have gotten this far with the engine without uncovering basic problems which have been normal in every jet engine I have ever worked with... Prospect of an early flight engine is dismal, and I feel our program is greatly jeopardized.7

To prevent further scheduling setbacks, Johnson and CIA officials already had decided to use the less powerful J75 in early flights. The airframe had to be slightly altered to accommodate the substitute engine, which could power the craft only up to Mach 1.6 and 50,000 feet. Despite enormous development costs of the J58, the engines were not ready until January 1963, and the A-12 did not reach Mach 3 speed until the following July��more than a year after the first test flight.

My source ARCHANGEL:

CIA’s SUPERSONIC A-12 RECONNAISSANCE AIRCRAFT

DAVID ROBARGE CIA CHIEF HISTORIAN

CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY WASHINGTON, D.C. Second Edition 2012

Linda Sheffield Miller

@Habubrats71 via X

#sr71#sr 71#sr 71 blackbird#blackbird#aircraft#usaf#lockheed aviation#mach3+#habu#aviation#reconnaissance#cold war aircraft#aviation military#aviation military pics#military aircraft#military aviation

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

MATTAWA, LA CAVE DEVELOPMENT, OTTAWA RIVER 1953, 5 MILES NORTH OF MATTAWA ABOUT 65 MILES UPSTREAM FROM THE DES JOACHIMS DEVELOPMENT CAPACITY- 144,000 KILOWATTS (192,000 HORSEPOWER) IN SIX UNITS, WITH PROVISIONS FOR 2 ADDITIONAL UNITS. OPERATION HEAD -77 FEET. CONSTRUCTION FORCE- 1500 EMPLOYEES. LENGHT OF STRUCTURES: DAM AND HEADWORKS -- 2,500 FEET WITH MAXIMUM HEIGHT OF 130 FEET ABOVE SOLID ROCK, 12,000 ACRES, FORMING A LAKE ABOUT 30 MILES LONG AND 1 HALF MILE WIDE EXTENDING UPSTREAM TO TEMISCAMING. SIX 40 FEET WIDE SLUICEWAYS AND FORTY- TWO 16 FOOT WIDE STOP- LOG SLUICES WITH A MAXIMUM DISCHARGE CAPACITY OF 140,000 CUBIC FEET ( 875,000 Gallons) Per Second. STEEL FOR ENTIRE PROJECT: 25,000 TONS ( 625 Carloads) LUMBER OF ENTIRE PROJECT: 10,000,000 BOARD FEET ( 393 CARLOADS - EQUIVALENT TO A TRAIN 3 AND A HALF MILES LONG) AND 740,00 TONS OF CONCRETE.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

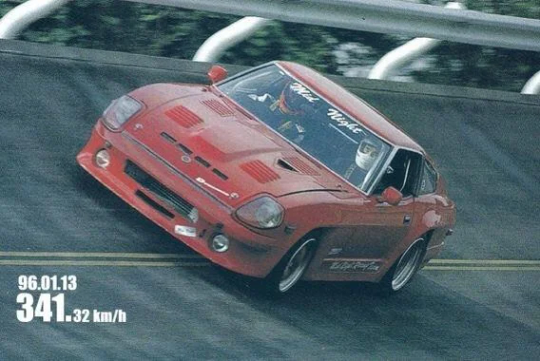

The Mid Night Club

The Mid Night Club, also known as ミッド ナイト クラブ (Middo Naito Kurabu), was formed in April 1982, despite many sources mistakenly claiming its founding year as 1987. The club is best known for its high-speed races on Tokyo's Shuto Expressway at night. Membership was highly coveted, as it signified elite status within the street racing community due to the stringent entry requirements and the extraordinary skill and discipline of its members. The club became notorious for its adherence to safety and speed, with members driving highly modified cars capable of sustaining extreme speeds over long distances.

The Mid Night Club didn't focus on acceleration or cornering ability; their sole objective was top speed. To gain entry into this exclusive group, prospective members had to demonstrate their ability to maintain a speed of at least 260 km/h (160 mph) for prolonged periods and do so safely. Despite the apparent paradox, the club's gentlemen's code required members to avoid endangering others, and any reckless behavior would result in immediate expulsion.

Newcomers who met these criteria became apprentice members, needing to attend every meeting for a year before becoming full members. Throughout its existence, the club had about 30 members on average, peaking at 75. Most members could sustain speeds of 305 km/h (190 mph), while top racers could exceed 322 km/h (200 mph). Races typically began from speeds of 100-120 km/h (60-75 mph), with the third car in the pack signaling the start by honking.

Yoshida Special's 930, often referred to as the "Blackbird," is the most iconic car from the Mid Night Club, and for good reason. This extensively modified Porsche 911 Turbo (930) boasts a 3.6-liter turbocharged flat-six engine that delivers 700 bhp. It is rumored that the owner invested around $2 million in modifications. This substantial investment was necessary to create a machine capable of consistently maintaining speeds of 350 km/h (217 mph) for over 15 minutes—a feat that was challenging and costly in the mid-1990s and remains so today. Remarkably, the Blackbird is still operational.

The ABR-Hosoki Fairlady Z S130, another renowned car of a Mid Night Club member, was a significant rival to the Blackbird. Originally a 1978 Nissan 280ZX, it underwent extensive modifications to become a formidable show car and eventually made its way to the Wangan. This vehicle boasts 680 horsepower and is tuned to race at speeds of 330 km/h (205 mph), with a maximum capability of reaching 348 km/h (216 mph). There is a rumor that it once outpaced the Blackbird on the Wangan, but this remains unverified.

The Mid Night Club remains a legendary chapter in the annals of street racing history. From the iconic Blackbird Porsche 930 to the formidable ABR-Hosoki Fairlady Z S130, these cars and their drivers pushed the boundaries of speed and engineering. With a strict code of conduct prioritizing safety and skill, the club's elite members and their high-performance machines continue to inspire awe and fascination among car enthusiasts and the broader public alike.

The Mid Night Club, disbanded in 1999 following a tragic incident. During a high-speed encounter with a local Bōsōzoku biker gang, a collision occurred, resulting in the hospitalization of six innocent civilians and the deaths of two bikers. This incident violated the club's strict code against endangering other drivers, prompting its immediate dissolution.

#JDM#EUDM#Street Racing#Wangan Midnight#Wangan#Car Club#The Mid Night Club#The Mid Night Racing#Japanese Cars#Blackbird#Devil Z#Car Culture#日本のストリートレーシング#ミッドナイトクラブ#ミッドナイトレーシングチーム#湾岸ミッドナイト#首都高バトル#非合法ストリートレーシング

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Goodyear Inflatoplane was an inflatable experimental aircraft made by the Goodyear Aircraft Company, a subsidiary of Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, well known for the Goodyear blimp. Although it seemed an improbable project, the finished aircraft proved to be capable of meeting its design objectives, although orders were never forthcoming from the military. A total of 12 prototypes were built between 1956 and 1959, and testing continued until 1972, when the project was finally cancelled.

The original concept of an all-fabric inflatable aircraft was based on Taylor McDaniel's inflatable rubber glider experiments in 1931. Designed and built in only 12 weeks, the Goodyear Inflatoplane was built in 1956, with the idea that it could be used by the military as a rescue plane to be dropped in a hardened container behind enemy lines. The 44 cubic ft (1.25 cubic meter) container could also be transported by truck, jeep trailer or aircraft.[1] The inflatable surface of this aircraft was actually a sandwich of two rubber-type materials connected by a mesh of nylon threads, forming an I-beam. When the nylon was exposed to air, it absorbed and repelled water as it stiffened,[clarification needed] giving the aircraft its shape and rigidity. Structural integrity was retained in flight with forced air being continually circulated by the aircraft's motor. This continuous pressure supply enabled the aircraft to have a degree of puncture resilience, the testing of airmat showing that it could be punctured by up to six .30 calibre bullets and retain pressure.[2][3] Goodyear inflatoplane on display at the Smithsonian Institution

There were at least two versions: The GA-468 was a single-seater. It took about five minutes to inflate to about 25 psi (170 kPa); at full size, it was 19 ft 7 in (5.97 m) long, with a 22 ft (6.7 m) wingspan. A pilot would then hand-start the two-stroke cycle,[1] 40 horsepower (30 kW) Nelson engine, and takeoff with a maximum load of 240 pounds (110 kg). On 20 US gallons (76 L) of fuel, the aircraft could fly 390 miles (630 km), with an endurance of 6.5 hours. Maximum speed was 72 miles per hour (116 km/h), with a cruise speed of 60 mph. Later, a 42 horsepower (31 kW) engine was used in the aircraft.

Takeoff from turf was in 250 feet with 575 feet needed to clear a 50-foot obstacle. It landed in 350 feet. Rate of climb was 550 feet per minute. Its service ceiling was estimated at 10,000 ft.

The test program at Goodyear's facilities near Wingfoot Lake, Akron, Ohio showed that the inflation could be accomplished with as little as 8 psi (544 mbar), less than a car tire.[1] The flight test program had a fatal crash when Army aviator Lt. "Pug" Wallace was killed. The aircraft was in a descending turn when one of the control cables under the wing came off the pulley and was wedged in the pulley bracket, locking the stick. The turn tightened until one of the wings folded up over the propeller and was chopped up. With the wings flapping because of loss of air, one of the aluminum wing tip skids hit the pilot in the head, as was clear from marks on his helmet. Wallace was pitched out, over the nose of the aircraft and fell into the shallow lake. His parachute never opened.[4]

To Die For the InflatoPlane

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

In two separate timelines, Horace Horsecollar was abducted by aliens to become the hero the galaxy needed. One wants to go home, the other wants to make sure there is a home to go back to. 🐎🪐⭐

#disney#horace horsecollar#interstellar detectives#maximum horsepower#digital art#drawing#Mouseverse

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

In working on Maximum Horsepower related art, I came to a sudden conclusion about an inconsistency that isn’t one to begin with and that the series was somehow is loosely inspired on the Paul is Dead urban legend

Now Maximum Horsepower was supposed to take place in 1939 during the production of Fantasia. The plot is about Horace being tired of playing bit roles and often being relegated to the background. One day he hears about Mickey getting a starring role in Fantasia and decides he wants in on having a starring role. However on his way he’s abducted by aliens and taken to the other side of the galaxy, since they’re in desperate need of a hero. The rest of the series would have focused on Horace getting into all kinds of life threatening situations, all while trying get back to Earth.

Quite a few people have pointed out that this wouldn’t make sense since Horace’s last appearance in the classic theatrical shorts was in the 1942 short Symphony Hour. I too believed this at one point until I realized there’s a gap in Horace’s filmography, one that makes sense. You see Horace’s last appearance in his classic design was in the 1938 Donald and Goofy short The Fox Hunt. He didn’t get redesigned until the 1941 remake of Orphan’s Benefit.

In the pitch trailer for Maximum Horsepower, his design is literally his classic design but now he’s buff (like Launchpad buff!).

Now to explain how the Paul is Dead urban legend plays to the Maximum Horsepower lore. Very quick summary of the urban legend itself: In 1969 Paul McCartney died in a car crash, but to spare any grief he was replaced by a look-alike. In the Maximum Horsepower pitch trailer the narration at the beginning mentions something similar. The lore claims that Horace did resurface after being gone for a while, though some (in my headcanon it’s Clarabelle) believe that the Disney studios quietly replaced Horace with a look-alike so not cause any problems with the copyrights or stir up any drama. Thusly making the connection and an obvious inside joke.

(Yes they are literally running with this! They literally made Horace the Paul in their group!)

The idea that covering up Horace’s disappearance with a “redesigned” Horace makes so much sense. Not to mention Horace’s modern design isn’t consistent. But this is mainly due to different artists (including myself).

So in conclusion it makes sense that Maximum Horsepower starts in 1939 seeing that 1938 was the last appearance of Horace’s classic design thus the notion of his redesign being the perfect cover up for his disappearance. Which I just realized could have happened to Clarabelle too since her classic design stopped appearing in the classic shorts after 1941. The Epic Mickey screenshot is to confirm Clarabelle didn’t get a redesign till late 1941/ early 1942.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

since we're officially 1 race into the championship, i thought i'd put together some assorted wwcr thoughts.

the bike

the Yamaha YZF-R7s provided to each team are, to my knowledge, all standardized. the bike is a 689cc inline twin that despite its larger displacement hits about the same top speeds as a Moto3 bike, but weighs twice as much. the most interesting aspect of the machine is its use of a crossplane crankshaft, where the crank throws are angled at 90 degrees from each other instead of 180 degrees. wikipedia offers this visualization to explain the tech:

if we were to condense this down from three dimensions to two, then it could be explained like this: there's one crankshaft angled at twelve o'clock, one at three o'clock, one at nine o'clock and one at six o'clock. however, since the bike is a V2, we can ignore those last two throws, since they don't exist in this engine.

this design is based off of the current Yamaha build in MotoGP, and is meant to improve torque at higher RPMs. its horsepower peaks at 72.4 hp around 9,000 RPM, but the maximum torque outputs at 6,500 RPM. that means it accelerates quickest in the middle(ish) area of its RPM range. this means it can run out of a turn pretty well under the right rider.

look, it's no secret that the bikes are slow. i'm not going to argue against that. this is a $9,000 motorcycle for a series with a $25,000 entry fee, while Moto3 boasts a fee more than twice that. it's a cheap series, but it's getting off the ground -- which brings us to our second point of focus:

the teams

i was impressed to see the diversity in teams and sponsors. some riders, like Tayla Relph, are essentially financing their ride entirely on their own. her team, TAYCO Motorsports, is named after her own social media and brand strategy company. her day job funds her racing career. other riders, like Mia Rusthen, are self-funded without being bolstered by a secondary income.

on the other end of the spectrum, Pata Prometeon Yamaha is running a WWCR team much like it runs its WSBK team. though they don't have their own custom livery to show off their fancy sponsors (unlike close competitors Forward Racing), they can obviously afford to invest in top talent. their star Beatriz Neila is coming directly from the Copa R7, a Spanish racing series also limited to the Yamaha model. she might be the most experienced with the machine out of anyone on the grid.

there are plenty of teams that are firmly in the middle, budget-wise. Sekhmet Racing team is owned/operated by Maddi Patterson -- yeah, Simon Patterson's wife -- and boasts a wide range of midlevel sponsors and partners, even if they also lack a custom livery to advertise them. Sekhmet for sure has the best social media management and brand strategy of any team, with its own website with articles, rider bios, and a mailing list. they are pursuing legitimacy in every way, and it's obvious by how they present themselves that they do not want to be a small-time team in a small-time series.

the riders

we're one race in and i've already started to find my favorites. there were riders i was aware of before WWCR; i think any dedicated racing fan could at least name Maria Herrera and Ana Carrasco, but i'd heard of Beatriz Neila and Sara Sanchez as well. in the run-up to the season's start, i've read lots of interviews with various competitors on Paddock Sorority, a site dedicated to covering women in racing.

off the bat i really like Luna Hirano, both for her extensive endurance career and her fantastic quotes:

her love of video games is relatable, but i'm more interested in her mention of an injury impeding her ability to train. this seems fairly common among competitors, with British rider Lissy Whitmore relaying the exact same thing.

i understand that it's completely normalized for riders to participate while injured or recovering. but so many of this women are entering this class -- a potential career high -- with their performance already permanently hampered by injury. it speaks to, for one, just how much work these women have to do to be recognized, and how little of it pays off. to be nearly incapable of running after an injury and continue racing anyway is nothing short of Herculean to me. not to mention Ana's remarkable recovery from her catastrophic back injury a few years ago. and contrast this with other supposedly "entry-level" series. how many Moto3 riders are coming in already debilitated? it doesn't feel fair.

i've been making these comparisons to Moto3 due largely to the similarity in speed. but i also would prefer WWCR to be considered a feeder series on par with Moto3, instead of what it has already been pigeonholed to be: a place where women can be cloistered off, riding inferior machinery with their supposedly inferior skills. the fact of the matter is that so many of these women came up riding at the exact same tracks as current MotoGP stars, but were never offered the same opportunities, and thus never developed at the same caliber. Maria Herrera, one of the top contenders for the championship, came in second in the 2014 CEV Moto3 season, behind Fabio Quartararo. she describes the shift in her career:

all of this is to say: WWCR's existence is not a victory against sexism. still, i celebrate it for platforming female racers. in a fair world, Moto3 and Moto2 teams would be looking at the current WWCR roster for future talent; but we do not live in a fair world. nevertheless i hold out hope that this series casts ripples throughout international classes, and maybe in ten or twenty or fifty years, female riders will be competing against men all the way to the top.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traintober day 25

Hey guys,

I know I said I wasn't going to really participate in this year's traintober, but I ended up writing something over the last few weeks and figured I'd post it here. I'm a freelance contributor to Trains.com, the web arm of Trains Magazine, (you can read my IRL work here) and I wrote this for that. However, they have a maximum of about 4,000 words for print and 600-1,000 words for web, and this is past 7,000. So even if it makes it into print, it's not going to in its original form. So I'm giving it to you guys. Everything you're about to read is real. There's even an NTSB report on it.

Negligence and Gravity: The Story of a Train Wreck

Prologue

November 17, 1980

Cima, California - a barely inhabited place on a barely used road. A one horse town where the horse had run off. It sits at the intersection of two empty roads, with nothing to show for it but a general store-slash-post office. A true speck on the map, it likely would have been abandoned long ago had it not been for the presence of the Union Pacific Railroad, which sent dozens of trains each day past the ramshackle post office. Many trains rolled right on by, but more and more stopped, checking their brakes, cooling their wheels, or manually setting air brake retainers on each car of their trains.

They did so with good reason; stretching out beyond the post office towards the west, and paralleling the only main road, was a railroad line some twenty miles long. Part of the UP California subdivision that stretches from Las Vegas to Yermo, and then on to Los Angeles, it descends two thousand and six feet between Cima and Kelso, another barely-there town in the California desert. It was and still is one of the steepest portions of the Union Pacific system - accounting for curves and uneven geography, the UP considered the line to be a sustained 2.20% gradient. Any train that exceeded certain weight, braking force, or locomotive limitations was required to stop at Cima, and manually set brake retainers, before continuing down the hill.

As the clock ticked towards 1:50 in the afternoon, three trains entered this tale much like characters in a Shakespearean tragedy.

On the southern passing track is a long grain train, Extra 3135 West. 73 hoppers trail behind a lashup of SD40s, with dash-2 model 3135 on point. The air above the locomotives shimmers and ripples as heat from the motors, exhaust vents, and dynamic brake blisters radiates off into the mild November air.

In the center, a van train rolls past. The train, officially known as both 2-VAN-16 and Extra 8044 West, slows but doesn’t stop as it reaches the summit. Union Pacific has deemed this train capable of descending the grade with no extra precaution, and with good reason. Five locomotives are leashed to the front of this 49 car merchandise train, four SD40-2s trailing behind UP 6946 - the youngest member of the road’s 47-strong class of beastly 6,600 horsepower DDA40Xs. It’s an 8-axle titan in its last months of regular operation, with almost two million miles under its belt. The hot air from Extra 3135 mixes and whirls with the exhaust from the van train as it rolls by, the slab sides of the hoppers amplifying the bangs and squeals from 49 autoracks and piggyback flats. The noise increases as the train nears the end of the yard, the dynamic brakes already coming online as the train crests the summit. The engineer gives a blast from the horn as he passes the head end of the stopped trains, and then the van train is on its way down the hill. The caboose clears the track circuit at the far end of the passing sidings, and recedes into the distance. Within a few minutes the train is a distant shimmer as it snakes its way down the hill, an 8 million dollar steel serpent, bound for the hustle and bustle of Los Angeles.

Finally, there is the train on the northern passing siding. Extra 3119 West is not like the other two - there aren’t four or five locomotives hitched to a gargantuan train, one that stretches into the distance for a thousand feet or more. Instead, there’s a short consist of twenty cars, sandwiched between a single locomotive and a caboose. The cars are piled high with crossties, almost 11,000 of them, urgently needed by a tie gang at Yermo. So urgently, in fact, that if it hadn’t needed to stop and pin down its brakes, this lowly work train would’ve been rolling down the hill ahead of the high-priority van train.

Extra 3119 West, headed by the SD40 of the same number, has been in Cima for just under half an hour. In that time the crew had applied all the brake retainers, checked for defects, and otherwise readied their train for the descent into Kelso. Stopping meant that they’d be following the van train the whole way down, and so once the van train had gotten sufficiently small in the distance, the radio crackles. It’s dispatch, asking quite insistently if they were ready to go. They were, the engineer replies, and without any more to-do, the switch clunks into place, and the signal goes green. A double blast on the horn heralds the train’s departure, followed by the quiet squeal of brake shoes on steel wheels. There is no increased engine noise from the dynamic brakes. The train slips onto the main line, speed increasing slowly. By the time the caboose enters the main line, things are already going disastrously wrong.

Shortly thereafter, Extra 3135 powers up its train and descends the hill in a much more controlled fashion. Silence falls over Cima.

-

Negligence

November 13, 1980

The tale of negligence started three days earlier, at the Union Pacific tie plant in The Dalles, Oregon. Nestled in the valley of the Columbia River, The Dalles is nowadays best known for being the site of the worst bioterrorism attack in the United States, when members of the Rajneeshee religious organization poisoned several local restaurants with Salmonella in an attempt to influence local election turnout. However, that event is still four years into the future at this point, and the big news items in town are the May renumbering of Interstate 80N to I-84, and the March eruption of Mount St. Helens, some 65 miles away.

The Union Pacific tie plant, located between the west side of town and the newly-renumbered I-84, received an urgent order: 20 cars of 9-foot ties, urgently needed in Yermo, California. A mechanized tie gang working in the high desert is running low. Any delay will mean millions of dollars in wasted man-hours. The ties, estimated to number between 10 and 11 thousand, were hurriedly loaded into a series of F-70-1 bulkhead flatcars, modified for crosstie carriage with the addition of steel stakes down each side to prevent shifting. In addition to the 20 cars for Yermo, another group of 5 F-70-1s were being loaded with lighter 8-foot yard ties for renewal elsewhere on the California Subdivision. Inside the plant office, waybills for the 25 cars are being filled out, by hand. One of the most routine and mundane portions of loading railcars, the staff at the tie plant had made strides to simplify their workload; each waybill had been pre-filled with a seemingly appropriate weight figure: “about 60,000 pounds,” done in neat typewritten letters. This saved time, as it meant that tie cars didn’t have to be weighed, and exact quantities of loaded ties did not have to be known. Simple addition of this number to the known light weight of an F-70-1 flatcar (80,000 pounds), gave an estimated weight of 140,000 pounds per car. To the staff of the tie plant, complacent and ignorant, this seemed reasonable. They couldn’t know, because they didn’t want to, that the average per car weight of the 20 cars for Yermo was over 200,000 pounds.

-

November 17, 1980

“Urgent” might have been an understatement, when describing the journey these cars took. It took three days for the 25 flatbeds and their thousands of crossties to travel 1,260 miles across the Union Pacific system. They rolled into Las Vegas just before 1 AM on a manifest train; somehow, despite leaving The Dalles as a single block, a car containing beer had been inserted into the middle, with fifteen cars on one side and ten on the other. The how and why did not matter to the Las Vegas yard crews, who had been informed of the expedited nature of this train. Within minutes, the 26 cars had been taken off the manifest and were being shoved against a caboose that was already waiting. A third shift yard crew made quick work of the beer car and the five cars containing yard ties, but “disaster” struck when it was discovered that the caboose’s electrical system was non-functional. Somehow, despite having a major rail yard at their disposal, no other caboose could be found, and the issue could not be remedied. UP regulations forbade trains from running without rear lights between sundown and sun-up, so the highly expedited train was suddenly forced to cool its heels in the yard until lighting conditions improved.

With the delay, the new crew was scheduled to go on-duty at 8:05 AM, but just twenty minutes before, at 7:45, the Terminal Superintendent was informed that actually, the third shift crew had accidentally cut out the wrong cars - five cars of the 9-foot ties, not the five cars of 8-foot ties - and Extra 3119 West was about to set off with the wrong load. He responded with the unbelievable phrase of “Ties are ties”, and refused to have the incorrect cars set out, before reversing his decision some minutes later. While no other quotes are attributed to him in the subsequent NTSB report, his insistence on having the nearest yard crew drop what they were doing and fix the issue while he personally inspected the re-switching of the train speaks volumes on his mood at the time.

Not that he was of any help. During this frenzied switching, one car of 8-foot ties remained in the train. Its number - UP 913035 - was confused with another flatcar in the train - UP 913015. While minor in the overall sense, this slip-up shows exactly how quickly Las Vegas yard was working to get Extra 3119 West to its destination. When the train was finally ready, there were 19 cars of 9-foot ties behind locomotive 3119, and one car of 8-foot ties. As a car inspector was found, the final lading documents and waybills were presented to the engineer and conductor. Based on the flawed math of the tie plant, the train should have weighed 1,421.25 tons, however the final waybill read 1,495 tons exactly. Aside from being incorrect even against the tie plant’s figures, this weight was exactly five tons less than an internal UP tonnage/horsepower ratio that would determine whether or not the train would have to stop at Cima to apply brake retainers - with a 3,000 HP SD40, the train could not exceed 1,500 tons without incurring serious delays.

Based on the actual weight of a standard crosstie, and estimating how many were on the train, it’s likely that the train exceeded 2,000 tons.

It was customary for two car inspectors to check each departing train for defects and perform a brake test, however on the morning of the 17th, only one was available. Allegedly, he did his job and applied all due diligence, however it must be noted that no one who saw him conduct the test or the inspection lived to tell about it. Considering the haste in which the train was switched, the almost 8 hour delay due to the electrical problems in the caboose, and the close attention from the Las Vegas terminal superintendent, it’s possible that he rushed the job.

Actually, it’s certain that he rushed the job. Investigation of the wreckage would show that over half of the F-70-1 flatcars on Extra 3119 West had brakes that either only partially functioned, or did not function at all. At least three had their brakes cut out altogether. A proper inspection would have revealed that these cars were in a deplorable state of repair, with braking systems that could only be relied on for moral support, and in some cases not even that. But that would have taken time, time that the Union Pacific did not have, or rather, time that the UP did not want to spend.

Since 1979, the railroad had been pushing yards to decrease dwell times on through trains - Las Vegas yard had been given explicit instructions in writing that many high priority trains were to be given a minimal inspection, and were to be on their way again in 15 minutes. Later in the day when 2-VAN-16 arrived in Las Vegas, the head end crew noted that the train had been subject to an abbreviated inspection and air test, essentially rubber-stamping their train, and every other train that came through the yard.

So the inspector cleared Extra 3119 West, because he did know - he knew how much work would need to be done, how long it would take, how long it was supposed to take, and how much trouble he’d likely be in if he brought up the train’s condition.

-

Finally, at 10:00 AM, over 8 hours since it was supposed to depart, Extra 3119 left Las Vegas. Being technically a maintenance of way train, its crew was pulled from the extra board. While these men weren’t inept, one would be hard-pressed to find a less experienced crew on any road train that day:

David Totten, the engineer, had been with the railroad since 1974, but he had only been qualified as an engineer since January of 1979. Noted as a stickler for rules, and a capable railroader, he completed the relevant tests with a 96% score. However his road experience was limited - he’d only descended the grade from Cima 27 times in the last four and a half months.

Alan Branson, the conductor, had been with the company since 1973, but as a switchman in Los Angeles. He’d only been at his current position since April, at which time he was transferred to the Las Vegas extra board.

Cecil Faucett, the rear brakeman, had been with Union Pacific since June of 1978. He’d spent most of his time as a switchman in Los Angeles, and had only transferred to Las Vegas road service in February.

Wallace Dastrup, the head brakeman, had been with Union Pacific since May of 1979. After being briefly furloughed and transferred to Los Angeles, he was sent back to Las Vegas in late October of that year.

The oldest man on this crew was Engineer Totten, who was 31. Head brakeman Dastrup was the youngest, at just 22 years old.

-

Leaving Las Vegas, the trip proceeded normally, with the 3119 providing enough power to bring the train up the 1.00% grade that led from Las Vegas to Erie, Nevada at a steady 20-25 miles per hour. Behind them, separated by time and distance, were Extras 3135 and 8044 West. 3135, with a top speed of 50, left at 10:20, while 8044 (2-VAN-16), left at 12:05. It had a top speed of 70, and would easily catch up to the slower grain train at Cima. If Extra 3119 West had been any other train, it would likely have been profiled to wait in Cima as well, but on this day, the Van train would be following Alan Branson’s caboose all the way to Yermo.

Meanwhile, onboard the 3119, engineer Totten was discovering that his day was not going to go as planned. As the train descended the 1.00% grade outside of Erie, he discovered that the locomotive’s dynamic brakes were not functioning. This meant that the train would have to rely solely on its air brakes for the entire journey to Yermo - a daunting task considering the grade at Cima.

Union Pacific regulations explicitly ordered trains without dynamic brakes to stop at Cima and apply retainers, to maintain a speed of no more than 15 miles per hour, and to stop at the passing siding at Dawes - another speck on the map halfway down the hill - to cool not just the brakes, but the train wheels themselves.

Totten was known to be a stickler for the rules, and so he informed dispatch as he descended the grade out of Erie. Without comment, the Salt Lake City based dispatcher encoded the traffic control computer to put Extra 3119 West into the siding at Cima. At no point was there any mention of finding another engine for the train, or any other means of fixing the situation en-route.

The dispatcher, who wanted to know as little as possible, didn’t care.

-

The train rattled into Cima at 1:29, and Totten balanced it atop the summit, a location about 1,100 feet from the end of the siding. Boots were on the ground as soon as the train stopped moving, with Faucett and Branson moving up the train from the caboose, manually setting the brake retainers on the F-70-1 flatbeds to the high pressure position one at a time. The air was cool, only 62 degrees, and it was slightly overcast - a far cry from the soaring summertime temperatures this part of the state could reach.

As they worked, Extra 3135 arrived. It didn’t rattle so much as it rumbled - 75 loaded grain hoppers slightly shaking the earth as the two men worked. They probably didn’t envy the crew on that train; setting 75 retainer valves, and the long walk from each end of the train to reach them, was a daunting task.

It didn’t take long to set the retainers - at the halfway point of the train, they met head end brakeman Dastrup, who had been working his way down the train as they worked up it. He reported no defects on the head end of the train, and neither did the rear crew. They didn’t know - couldn’t have known - about the abysmal state of the flatcars; they were looking for dragging objects and hissing air leaks, and found none. Their portion of the job done, Faucett and Branson moved back down the train, leaving Dastrup to work his way back to the locomotive. It would be the last time that he was ever seen alive.

Shortly thereafter, the train began to move, engineer Totten moving the train onto the downgrade at the end of the siding to wait for the clear signal. At this point, they were waiting on the Van train coming up behind them, and then they’d be home free. In the caboose, Faucett glanced at the brake line pressures and observed nothing unusual. In the cab of the 3119, Totten was likely readying himself for the downgrade. Without dynamics, it would be a challenging descent, but the air brakes should be able to hold the train without much difficulty.

He had no idea that half his cars had non-functional brakes.

He had no idea that the train was overloaded.

He had no idea what was about to happen to him.

-

Inside the cab of Extra 3135 West, the engineer watched as 2-VAN-16 slipped by with muted alacrity. Across the main line from him, the short work train got ready to depart as soon as the switch aligned. He’d be next, and he readied himself as the other train rolled onto the main line. It built speed quickly, and soon entered the main as his watch clicked over to 1:59 PM. A few minutes later, his turn came, and the signal flashed to green. He powered up his lashup of SD40s, and the train slowly began to descend the grade in full dynamic.

-

“I keep setting air and it won’t slow down!”

-

Inside 2-VAN-16, the engineer began paying less and less attention to the tracks in front of him, and more attention to the radio beside him. 3119 West was having some difficulties with its braking - already a concern for any railroader, but considering that this was the train directly behind him, an elevated level of concern was prudent.

-

In the caboose of Extra 3119 West, the brakes applied as the train rolled past 17 MPH, and were not released again.

-

2.9 miles behind Extra 3119 West, in the cab of UP 3135, the engineer of the grain train could see both trains ahead of him: the distant speck of 2-VAN-16, some 7 miles away, and the work train in front of him. “That looks like it’s smoking,” he remarked to his brakeman. The two men looked into the distance; as the work train passed Chase, another former town on the UP line, it appeared to be smoking heavily - far too heavily for the short distance from the summit it had traveled.

-

On the few F-70-1 flatbeds that possessed functioning brakes, the wheelsets began to heat up dramatically. The brake shoes began to abrade from 2,000 tons of train pushing against them.

-

The Van train had cleared the passing track at Dawes, and was about 5 miles ahead of Extra 3119.

-

Inside the caboose of Extra 3119, the speedometer needle swung past 19 MPH. It was rising at a rate of 1.6 MPH every minute.

-

Things began to happen very quickly. The time was 2:14 PM

-

Following behind the smoking train, the head end crew of Extra 3135 West watched as the signal light at the east end of Chase went red-yellow-green like a slot machine. The only way for that to happen was for a train to pass through both the western home signal, and the western intermediate signal, at a rapid clip.

-

“I have 30 pounds of engine brakes!”

-

Inside the caboose, Faucett and Branson looked at the radio in horror as the speed continued to increase. They’d driven faster than this on their way into work, but now 20 MPH felt terrifying. As they flew through Chase, Branson remembered his training, still fresh in his mind, grabbed hold of the caboose air valve, and put the train into emergency. He heard the brakes come on under his feet and assumed, naively, that they’d just applied throughout the entire train. He had no idea that the brakes would only apply across the entire train if Engineer Totten had the train in emergency as well. He had no idea that by putting the train into emergency while a substantial service brake application was being made, he was causing a pressure relief valve inside the 3119 to continuously open, to try and restore pressure in the train. He had no idea that Union Pacific, in a cost-saving measure, had elected not to equip its SD40s with a brake pressure warning light that could have alerted Totten to what had just happened. He had no idea that UP’s driver training called for engineers to continue to make service brake applications in the event of a loss of braking, instead of immediately putting the train into emergency from the locomotive. He had no idea that putting the locomotive into emergency was the only way to override the pressure relief system.

He had no idea that by trying to save the train, he’d sealed its fate.

Union Pacific rules required the conductor to put the train into emergency if a situation like this occurred. They did not require the conductor to call the head end and inform the engineer. In his panic, and going off of instinct, Alan Branson frantically ran to the front of the caboose to try and uncouple it. He would not make a radio call for the rest of the trip down the mountain.

-

With half the train in emergency, and the relief valve drawing air away from the few brakes that worked, Extra 3119 West began falling down the mountain.

-

Gravity

The story of gravity begins in the cab of the van train, still some five miles ahead. As the engineer kept his attention on keeping his train in line, the radio issued forth the latest news on the disaster unfolding behind them. “I’ve made a full service application, and it’s not slowing down. We’re going about 25 and still speeding up!”

In the cab of an eastbound train, waiting for its chance to climb the grade out of Kelso, the dispatcher’s lackadaisical response could be heard easily. “So you’re not going to be able to stop at Dawes?”

“No. I don’t think we can stop at all.”

The dispatcher said nothing in response.

In the cab of the Van train, the engineer realized exactly what was going to happen. He began notching back the train brakes, and slowly throttling down the dynamics to idle. With one hand on the radio and one on the throttle, he slowly began advancing the throttle even as he called for permission to exceed his 25 MPH speed limit.

The permission he was given would be the last time that the dispatcher offered any meaningful help during the runaway. There was no talk of programming the switches at Dawes to allow the Van train shelter, to offer the four men aboard their one chance at safety. Instead, the dispatcher, hundreds of miles away in Salt Lake City, sat back to watch the chaos unfold, seemingly believing there was nothing he could do to help.

-

Two minutes later, at 2:17 PM, the two trains were still separated by five miles. 2-VAN-16 was just clearing the west end of the passing track at Dawes.

Four minutes later, and Extra 3119 was screaming through Dawes at 62.5 MPH.

5 miles ahead, 2-VAN-16 was running for its life, all five locomotives running flat out in full throttle. For now they had the edge, but they were trying to outrun gravity. All they could hope for was that the rolling resistance of the runaway would eventually cause it to stop accelerating.

-

Three minutes later, and false hope reared its ugly head. Accelerating at a “phenomenal” rate, the speedometer inside the 3119 reached 80 miles an hour and pegged itself there. David Totten, who had been broadcasting his train’s terrifying plunge down the hill over the open radio channel, had no idea that the needle was incapable of indicating a number higher than that.

As his train raced towards destiny, Engineer Totten kept relaying the same false information: “80! We’re doing 80!”

Inside the cab of the 6946, this incorrect information alleviated some worry - if 3119 was topping out at 80, it was possible to use the Van train’s nearly 19,000 horsepower to simply outrun the runaway - once they got past Kelso, at this point a short distance away, the grade lessened to 1%, and the force of gravity decreased.

Then there was an alarm blaring in the cab, and the train began to slow down as they roared into Kelso, the engine RPMs dropping suddenly, horrifyingly. They’d tripped the DDA40X’s overspeed sensor as they passed 75 MPH, and the entire train began to shut down on them. Chaos reigned in the cab for a minute, as the engineer frantically canceled the alert, managed to avoid the penalty brake application, and brought the train back up to full power. Their speed dipped all the way down to 68 before they began accelerating again.

It’s not known what was going on inside the caboose of the Van train, but the 3119, smoke and sparks flying from its wheels, must have been visible behind them.

--

Kelso

The station at Kelso was a tired, yet gorgeous, Spanish Colonial Revival structure located on the north side of the tracks. For a generation it had been a bustling hive of UP crews; a locomotive watering hole and a depot for eastbound helpers. The advent of diesel locomotives, and the elimination of manned helpers on Cima hill had resulted in the station becoming a shell of its former self. The only ties to its former past was the lunch counter, which still served hot meals and cool drinks to the town’s few dozen residents, and the skeleton UP crews stationed at this depot, so far into the desert that not even TV signals could reach it.

On the lunch counter, a cup of coffee cooled, its drinker nowhere in sight. Anyone and everyone who had been in the station were now outside, standing under the trees that lined the old platform, obscuring the station from sight. A few more were on the other side, standing near the MoW sidings on the south side. Further west, beyond the Kelbaker road level crossing, the crew of an eastbound freight waited in “the hole”, their eyes transfixed on the spot in the middle distance where the rails gently curved into view from behind the trees.

The radio continued to issue David Totten’s cool, calm, and collected reports of 80 MPH. With the train out of sight, it sounded like things may end with everyone walking away, but those listening closely heard his reports of an ever-shrinking distance between his locomotive and the caboose of the Van train and shivered.

The blare of a horn sounded, echoing across the desert. A second horn, almost as loud as the first, soon followed, a long continuous noise that would continue for some time, like the seventh trumpet of the apocalypse.

The broad nose of the DDA40X came first, the Van train rocking and rolling behind it as it charged forward. All five locomotives were in notch 8, the sextet of EMD 645 prime movers throwing up huge clouds of exhaust as they ran for everything they were worth. The horn sounded for the crossing, and then the train was past them, 49 high sided autoracks and TOFC cars whipping past with an almighty roar that was over almost as soon as it began.

The caboose zipped past the eastbound in a flash of Armor Yellow, and was gone into the distance. The blaring horn kept sounding, and heads that had turned to follow the Van train turned back to face the east.

They waited ten seconds. Twenty. Thirty. Forty. Fifty.

It’s entirely possible that nobody in the crowd had ever seen a train move as fast as Extra 3119 West.

It’s entirely possible that Extra 3119 West was at that moment the fastest train in North America.

With a thunderous roar not unlike a building collapse, the train streaked through the station, horn blaring continuously. It trailed a cloud of dust in its wake like a comet; the wind its passage created roared through the lineside trees, sending dead branches and leaves flying.

In the cab of the eastbound, the head end crew became the last people to see David Totten alive. He was sitting upright in his seat, calm and collected as though he wasn’t moments away from death, his radio handset in front of his face. He disappeared from sight almost as soon as he’d appeared, and the rest of the train followed. The F-70-1 flatbeds came and went in a flash, and the caboose followed, a barely visible blur of yellow and red.

Heads turned so quickly that they strained necks. The horn echoed off the station building and the waiting eastbound, a receding roar as the train very rapidly got smaller and smaller in the distance. Within moments the only trace of the runaway train was David Totten’s voice, issuing from the radio his final reports. He became a ghost who hasn’t realized that he’s dead.

-

Less than one minute later, the train screamed past the hotbox detector at milepost 233.9, less than two miles distant. It isn’t known whether or not the detector actually found a defect with the train. It could have passed by so quickly that a proper reading couldn’t be taken, it could have still been calling out the speed and condition of the fleeing van train, or possibly it couldn’t handle a number that high; when the train eventually came to a stop, investigators found that the wheels on the flatcars with functioning brakes had reached anywhere from 400 to 800 degrees fahrenheit. The wheels on the locomotive had reached almost one thousand.

What was detected though, was the train’s speed. As the caboose ripped past the steel box mounted on the lineside, the warbling call of the detector - voiced by Majel Barrett-Roddenberry of Star Trek fame - gave a chilling indication of just how wrong David Totten was.

“… TRAIN SPEED: ONE ONE TWO …”

-

Inside the cab of engine 6946, madness was in full swing. A terrible cacophony of noises filled the cabin: All five locomotives were in notch 8, the wind whistled into the cab from worn seals, and the 50 cars behind them banged and rocked as they exceeded their designed top speeds. They were approaching 75 again as they leaned into the curve just outside of Kelso. The big Centennial didn’t like that - its huge, single cast 4-axle trucks groaned and popped in horrifying fashion as it screeched through the curve, wheels just fractions of an inch from leaping over the top of the rail. The rigid wheelsets clung to the tracks by just a hair - ironically, if the overspeed warning hadn’t tripped when it did, the 6946 would’ve likely leapt from the rails here, going into the hole at 80 plus, killing everyone in the locomotive, while leaving the rear-end crew exposed to the runaway, traveling at well over 110 into a stationary target.

On the topic of the overspeed alarm, it was being dealt with - the head end brakeman was waging war against the locomotive’s internals, prying open the cabinet holding the speed recorder, before physically interrupting the travel of the needle, breaking the instrument in the process.

Desperate times call for desperate measures, and there was not a more desperate time than this; as the train rounded the curve, the Extra 3119 West could be seen clearly, moving faster than should have been possible. Their only hope for survival would be if they derailed on the curve that almost took out the Centennial, but it was not to be; the train screamed round the corner with less than thirty seconds of time separating the pilot of the engine from the back porch of the caboose.

-

Inside the caboose of 2-VAN-16, the rear end crew frantically tore cushions off of seats and wrapped them around themselves, as if that might hold off a rampaging locomotive. Hopefully they had time to make their peace with God.

-

The van train kept going. If the overspeed alarm hadn’t cut off the power when it did, and if they then didn’t derail on the curve west of Kelso, it’s possible that they could have outrun it. Extra 3119 West could have derailed, slowed, or perhaps just melted its wheels off, bringing the chase to an end.

But the overspeed alarm had cut in, and so the meeting of the two trains was made destiny by the forces of gravity, and the laws of physics. It was inevitable.

-

At 2:29 PM, 30 minutes and 23.2 miles since they set off from Cima, and 14 minutes and 18.5 miles since Conductor Branson had put the train into emergency, Extra 3119 West collided with 2-VAN-16. The runaway was traveling at approximately 118 miles per hour, while the van train was doing 80 to 85.

This 38 mph closing speed was disastrous to those in the caboose of the Van train. Both porches were crushed in immediately, and the 3119 shoved the rear bulkhead in significantly. The impact then threw the caboose from the track, separating it from its trucks and sending it tumbling down the embankment. It eventually landed on its left side and slid to a stop in the shadow of the disaster. Inside, it was carnage - both men had been thrown about the car before landing on the floor. The rear brakeman would survive with what were assuredly life-altering injuries to his face and back, but the conductor was not as fortunate, suffering mortal wounds to most of his body as he was tossed about the cabin. He would die inside the caboose within minutes.

On the train, the first collision was probably weathered by the 3119. The next three, less so. The rear three freight cars on 2-VAN-16 were triple level autoracks, each fully loaded with 15 or more automobiles. After impacting the caboose and throwing it from the rails, the locomotive continued forward, colliding again with the van train, and throwing the first autorack off the rails. After that, the process repeated for the second one, sending it flying down the embankment.

It was the third autorack that struck home. With the closing speed lowering with each successive crash, and without an anti-climber on the 3119, the autorack rode over the frame of the SD40, stripping the carbody from the frame like a filet knife.

David Totten and Wallace Dastrup were thrown from the cab as their locomotive ceased to exist around them. They landed on the desert floor, already dead from massive internal injuries. The 3119 would remain upright, and eventually came to a stop the quarters of a mile down the track, with everything missing above the frame except the prime mover and alternator.

The F-70-1s were thrown around like toys, flying off the tracks like they’d been cast aside by an angry god. Their wheel assemblies were disassembled into their component parts by the force of the derailment, followed by the cars themselves. The ties were next, flying through the air like javelins, before landing on the ground in clouds of dust, dirt, and splinters.

Finally, the caboose came to a stop. It and the last three cars remained upright, albeit derailed. Inside, Alan Branson and Cecil Faucett patted themselves down, unbelieving that they’d lived through the day.

-

The incredible speeds the runaway reached, and the tragic deaths of three men, triggered a full NTSB investigation. Swarming over the wreckage like flies on a corpse, they recovered a trove of evidence - the locomotive, its brakes abraded and wheels metallurgically altered after reaching almost a thousand degrees. On the ground they found throttle levers, brake controls, the locomotive data recorder, and the air brake valve, all normal in function. The destruction among the flat cars was so total that only 32 of 160 brake shoes, and 78 wheels were recovered. Of both of these, well over half showed no signs of overheating or abrasion, as if they’d never been applied. The rest showed evidence of extreme over-use, as they tried and failed to hold back the train.

The evidence thus far was concerning, to say the least. A train with no dynamics should have been able to make it down the hill… if it had working brakes. If it truly weighed what the waybill said it did.

The NTSB organized a test train shortly thereafter. They salvaged portions of the ill-fated train, including the last three flatbeds and 9,695 of the ties that had been scattered along the lineside. They gathered 17 more F-70-1 flatbeds - between this test train and the wreck, most of the railroad’s 55-strong fleet was involved in the investigation - and loaded them up, before hauling the train back up the long hill to Las Vegas. There, Union Pacific did everything they didn’t do for Extra 3119 West:

They weighed the train on the yard’s scale, and found that even with 1,000 fewer ties, the train still clocked in at a gargantuan 1,948.25 tons.

They inspected the train, and found that of the 20 cars, 16 of them had some kind of brake malfunction. Ten had partial brake function, while six had none at all. The three cars salvaged from the wreck train were included in the former group.

For two whole days, with NTSB investigators watching on, crews from the Las Vegas car department labored frantically in the winter sun to remedy the train's numerous faults. Remember that the single inspector on November 17th had been given scarcely 15 minutes.

When the test train was finally made operable, Union Pacific sent it down the mountain using only the train’s air brakes. They probably thought quite highly of themselves when the train reached Kelso safely, however the specifics of that test were dramatically different than the events of the 17th. To start, the 20 F-70-1s were probably in the best mechanical condition they’d been in for years, thanks to the train being properly inspected. This meant that when the test train descended the hill, it did so with all 160 brake shoes pressing against the wheels.

Furthering the point, the brake shoes were aided by a skilled hand at the controls - Union Pacific, so eager to prove that a train could make it to the bottom of the Cima grade entirely under air brakes, had pulled a highly experienced road supervisor out of retirement to run the test train. Again, remember that David Totten had been an engineer for just shy of two years.

As the investigation dragged on, further evidence came to light: UP’s training for engineers prioritized the use of dynamic brakes, and paid comparatively little attention to running a train with only air brakes down a grade. In fact, the railroad paid so little attention to air brakes that it was found that the UP’s rules regarding steep grades such as the one in Cima were laxer than any other railroad in the country, and were so lax that they fell afoul of the FRA’s minimum requirements for air brake regulations.

With this in mind, the fact that the railroad’s own rules had created a series of unsafe situations for crews seems totally unsurprising: applying the emergency brake from the caboose, not informing the head end if the emergency brakes are applied, and having engineers keep making service brake applications instead of applying emergency braking, were all the wrong moves to make in a situation like the one that happened to Extra 3119 West. A new crew like David Totten, Alan Branson, Wallace Dastrup, and Cecil Faucett, all fairly fresh from their training and relatively inexperienced, followed that training all the way to the end, because they thought it would save them.

-

In the end, the NTSB found that the accident was caused by a variety of factors: UP’s poor maintenance and inspection practices, inadequate training of train crews for hill duties, the underestimation of loads at The Dalles tie plant, and the improper actions of the dispatcher on that day.

Poor maintenance, bad management, a nonexistent culture of safety, and lax training. These are all things that have plagued the railroad industry from day one. The NTSB can only recommend changes, not enforce them; they must rely on the railroads to make the fixes. Change training practices, create better rules, enforce higher maintenance standards - all basic tenets of safe railroading, yet still sorely needed.

So, has Union Pacific made those changes? Has this happened again?

In a very real sense, the answers can be yes, and no, spending on your outlook:

Since 1980 there have been two more runaways on the Cima grade, the most recent one in 2023, and the other in 1997. The circumstances of the two runaways differ - and in the case of the 2023 crash, haven’t yet been fully investigated - but the fact remains that Union Pacific once again allowed a 100+ MPH runaway down the hill not once, but twice. Furthermore, severe under-estimation of railcar loads has caused several other fatal accidents just within the LA Basin, most notably the 1989 Duffy Street wreck, when inaccurate knowledge of the weight of bulk trona and failing dynamic brakes sent a Southern Pacific freight train hurtling down Cajon Pass, and into a residential neighborhood.

However, on the Union Pacific at least, a greater respect for life and safety has been given in the years and decades since the accident. Neither inadequate dynamic brakes, nor improperly maintained brakes, have sent a train flying off the rails on the Cima Grade. The two subsequent accidents, while catastrophic, occurred without loss of life, making the 1980 runaway the last fatal crash on the hill.

Did David Totten, Wallace Dastrup, and the unidentified brakeman of 2-VAN-16 die in vain? Will their story be forgotten to the annals of railroading? Only time will tell.

33 notes

·

View notes